Regardless of the property type, and whether working with a private owner or public agency, there are no two documents more important than the management agreement and the management plan. Together, these two documents help establish a strong foundation for the investment relationship and help protect the real estate manager by outlining the owner’s goals and overall strategy. Essentially, the property owner’s goals become the same goals for the real estate manager. These goals, which must be shared and be achievable, are the basis of the management agreement and the management plan.

In most cases, owners hire real estate managers because they need professionals who possess the knowledge, skills, and patience to do the job. Oftentimes, tenants do not know who owns the property and sometimes confuse the real estate manager for the owner. This is a common conclusion—from the legal aspect, real estate managers establish the leases, set rents, and safeguard the property. While operating the property on the owner’s behalf, the real estate manager is representing not only the owner to residents and others who have business with the property, but also the real estate management company associated with the property. When representing a company, there are expectations that should be consistent with the company’s brand identity. To respect and formalize the relationship between the owner and real estate manager, there must be a variety of agreed-upon terms and responsibilities.

A management agreement is a formal and binding document that establishes the real estate manager’s legal authority over the operation of the property. The real estate manager is technically an agent of the owner and serves as the owner’s fiduciary or trustee of the funds and assets associated with the property.1

The management agreement is a legal contract that should be prepared in consultation with a lawyer. The agreement establishes the relationship between the real estate manager and property owner for a fixed period, along with addressing the financial obligations of the owner. It also defines the real estate manager’s authority and compensation for services provided by specifying what those limits are. The following lists the specific contents of a management agreement:

A solid management agreement also includes provisions for termination of the arrangement under specific conditions, as well as numerous clauses related to general legalities.

Two major real estate management documents are prepared before a property is managed:

Fundamental to every contract are (1) the names of those entering into it, (2) the purpose of the agreement, and (3) the duration of the agreement. In a management agreement, these elements are (1) the parties, (2) management of the property, and (3) the term (or duration). The parties to a management agreement—the property owner and the management company or an independent real estate manager—must establish their authority to negotiate and sign this agreement. In particular, individuals who represent a partnership or a corporation must have specific authorization to sign contracts. Although the street address may uniquely identify the property, including the legal description of the property according to its title documentation may be appropriate. If the property has a special name, the agreement usually lists that name as well. The term of the agreement refers to the duration—usually stated as a specific number of years that include the beginning and ending dates. Provisions for automatic renewal on an annual basis when the initial term expires are also included—provided it is not otherwise officially terminated. The duration of the agreement and its renewability are negotiable, as are all of the other terms and conditions.

As a real estate manager (agent) acting on behalf of the owner (principal), the words and actions are binding on the owner. In the role of agent, a standard of care must be exercised in managing money and the property for the owner (fiduciary capacity). Being a fiduciary creates certain legal obligations, such as being loyal to the interests of the client by not engaging in activities contrary to that loyalty. This means paying scrupulous attention to handling the owner’s funds and not accepting any fee, commission, discount, gift, or other benefit that has not been disclosed to and approved by the owner-client.

When achieving the CERTIFIED PROPERTY MANAGER® (CPM®) designation, the real estate manager is subscribing to a specific code of ethics. In addition to the fiduciary obligation noted here, the IREM Code of Professional Ethics requires real estate managers to hold proprietary information in confidence, to maintain accurate financial and business records for the managed property, and to protect the owner’s funds. This code of ethics also outlines the duties to the manager’s employer, to former clients and employers, and to tenants and others. It sets forth requirements for contracting management and managing the client’s property and addresses relationships with other members of the profession and compliance with laws and regulations. Ethical practices are an important part of professionalism in real estate management and are usually a licensing requirement in most states.

Financial management, reporting, and general property management activities are among the normal duties of a typical real estate manager. Much of this work is interrelated-reporting and record keeping are natural functions of both financial management and general property management. The management agreement formalizes the job, often providing specific software requirements, procedures to follow, and sometimes stating intervals of time (daily, monthly, or annually) for the performance of various duties.

Financial Management. Within the management agreement are specific details regarding the financial arrangements between the property owner and real estate manager. The following lists the details of these financial agreements and the components managed by the real estate manager:

Establishment of Bank Accounts. The establishment of an operating account is an important provision of the management agreement.2 The management company usually chooses the financial institution and establishes the account—although the owner may participate in the decision. Receipts and expenditures flow through the client’s operating account. It’s important to remember that the management agreement should require a minimum balance to remain in the operating account at all times. Apart from the necessity of having adequate funds to pay the operating expenses of the property, the bank or the management agreement may require a minimum balance that remains in the account at the end of every month or accounting period.

The agreement to maintain more than one bank account is also discussed when creating the management agreement. Security deposits and reserve funds are often separate from operating funds for residential properties, but not normally for commercial properties. In fact, security deposits for commercial properties are recorded on the tenant’s ledger, but they are disbursed to the client as owner proceeds upon receipt. The security deposits are represented on the books as a liability and the management reports state that “any security deposits received within the month are included in the owner proceeds distribution.” State requirements for the handling of resident security deposits vary widely, from the requirement to pay interest on said funds to the handling of the deposit once received by the manager. It’s important to consult with the state’s real estate department or bureau in order to avoid running afoul of any licensing laws. However, most state laws require that security deposit funds be held in a separate account.

Regardless of the number of accounts necessary to maintain the property’s funds, the management agreement usually mandates that deposits be in federally insured accounts. Real estate managers are obligated to inform the owner if the balance in any account for the property exceeds the federally insured amount.

Separation of Funds. The management agreement should clearly state that the owner’s and real estate manager’s funds should not be mixed or commingled—this is not just a legal requirement, it’s actually a matter of professional ethics, good business practice, and a requirement in the IREM Code of Professional Ethics. All funds earned by the property—directly or indirectly—belong to the owner. Real estate managers are entitled to compensation from the property’s income and have the authority to pay themselves, but must fully disclose all financial transactions to the property owner(s).

Collection of Income. The management agreement authorizes the real estate manager to collect rent and any other income for the property—along with late fees and fees for bounced checks, credit checks, document preparation, and other administrative work. Some real estate managers retain fees collected from residents for these services as compensation for these exceptions to regular practices. Others receive separate management compensation on the fees collected, while some may not benefit at all. Unless state law prohibits it, the management agreement should specifically state the compensation for such collections and the arrangement—which is negotiated between the manager and the owner.

Payment of Expenses. Payment of expenses is another portion of the real estate manager’s duties. Expenses include debt service in addition to normal operating expenses. The remainder after all income has been collected and expenses have been paid—i.e., cash flow—is sent to the owner on a schedule established in the management agreement. If the property has more than one owner, the management agreement should state the proportionate distribution of the funds.

Provision for Audits. The owner usually has the right to audit the accounts of the property at any time—although a routine schedule is agreed upon for this procedure and clearly stated in the contract. Audits are also at the owner’s expense unless discrepancies in excess of a predetermined percentage are found. The real estate manager might be financially responsible for the audit if a discrepancy greater than the limit has resulted. The management agreement should state that all ledgers, receipts, and other records pertaining to the property belong to the owner even though they are usually in the possession of the manager.3 When the agreement ends, the real estate manager must send the records to the owner, while maintaining copies (or the originals) as required by state law.

Reports to the Owner. Real estate managers send the owner(s) a monthly management report that often consists of the following parts:

The narrative of operations, which reveals budget variances and their causes is one of the best ways to effectively communicate with the owner. The real estate manager typically prepares the annual budget for operating the property—the agreement usually states how and when that is to be done.

The number of written reports and their formats are definitely negotiable items. Institutional owners usually require the reports to conform to the institution’s forms, or they may require the use of specific software, which can involve additional time and expense. Since this can sometimes become an issue, the management fee and requirements for preparing the reports should be discussed and negotiated in the agreement.

General Property Management. Real estate managers provide a service and are either (1) self-employed or (2) an employee of a management company. That means they are not an employee of the owner—the management agreement should clearly state this fact. The following lists the general activities that should be described in the management agreement that details the manager’s authority in managing the property:

Advertising the Property. Since all advertising is at the owner’s expense, these objectives should be established and stated in the management agreement. Although advertising available space for lease in a small office building, strip shopping center, and residential property are all very similar, advertising is more prominent when dealing with commercial tenants because it’s an integral part of the leasing activity.

Executing Leases. Regardless of a particular leasing role, it’s important to understand the particulars of each lease because the real estate manager will ultimately administer its terms, collect the rents, and provide services to the resident or the commercial tenant. Because of their depth of experience, most real estate managers usually advise the property owners if certain lease clauses work to their disadvantage; they can offer suggestions regarding the language or clauses to protect the owners’ interest and property. (More information about leases can be found in Chapter 9.)

For residential properties, executing leases usually includes authorization to select residents, set rents, and enforce lease terms—in which case the owner and real estate manager should agree in advance on the lease form. In addition, state law may require the real estate broker, or principal broker, to sign or review rental agreements within a short time after execution. Multi-family leases have nearly all provisions in common. While they will specify the unit address, amount of rent, names of occupants, term, and whether pets are agreed upon, nearly all other provisions are the same.

Commercial leases, on the other hand, can vary widely within a single building. When dealing with commercial properties, lease renewals or new leases are normally negotiated, but the real estate manager will not typically execute them. For larger commercial properties, the manager might serve as the leasing agent and receive compensation for the leasing specified in the management agreement. However, a separate leasing agent may also be hired through a listing agreement to handle most of the leasing.

Keep in mind that the complexity of the leases, rents for commercial space, and number of vacancies or renewals may dictate the manager’s role. Leasing agents may be employees of a property, but because of their specialized role, they often have separate contracts and receive commissions based on the value of the negotiated leases. For a new property, the real estate manager may supervise the initial lease-up and then be directly responsible for renewing leases as they expire.

Hiring Staff and Administering Payroll. Although the owner is the employer of the property’s staff, it’s the responsibility of the real estate manager to hire and supervise them, along with administering payroll. However, multiple properties are managed for separate owners, the staff would be employees of the management company. Since many owners cannot afford to pay benefits (and depending on the management agreement), the management company sometimes pays benefits, charges them to the owner through a pro-ration or cost per person, or charges an additional management fee to cover the cost of benefits. The property staff usually includes maintenance personnel, site managers, and anyone else who works full- or part-time on the property. If the owner pays the expenses of employment, including salaries, benefits, employment taxes (Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment), and workers’ compensation insurance premiums, these expenses are paid out of the property’s operating funds.

Managing Maintenance. The real estate manager has the authority to perform all necessary and ordinary repairs and replacements to preserve the property by making alterations required to comply with lease agreements, governmental regulations, and insurance requirements. Apart from specific budgeted expenditures, the management agreement usually states a maximum dollar amount that can be spent on individual items of maintenance without obtaining prior approval from the owner, except in the event of an emergency. The management agreement may include a provision that requires the real estate manager be bonded or especially insured, which usually states the amount of liability involved.

Essentially, the owner is usually responsible for insuring the property, and the agreement should require that the real estate manager is identified on all policies as an additional named insured party. If the owner is the employer of record, the manager’s name or the management company should be listed as an alternate employer on the owner’s workers’ compensation insurance policy. Premiums and deductibles are the owner’s expenses, even though these might be paid out of the operating funds. The types of insurance required depends on the specific property, local practice, or state law. Consult with insurance agents to determine the best coverage for the property.

An important issue to negotiate for the management agreement is whether to establish and maintain a reserve fund. For residential properties, the reserve fund is usually a percentage of the property’s gross receipts or net operating income (NOI) to be set aside on a regular basis. For commercial properties, a specific amount per square foot of building area is sometimes set aside.

The agreement should state the owner’s responsibility for the property’s compliance with applicable governmental regulations, such as environmental laws and building codes, or any associated insurance requirements. It should also indemnify the agent, or real estate manager, against liability for noncompliance. If the owner does not cure any discovered noncompliance, the manager could become liable since he or she is working as the owner’s agent. However, the agreement should require the manager to advise the owner of any known noncompliance, the owner must then decide to implement changes or corrections and authorize the manager to do so.

Typically, the usual compensation, or management fee, for real estate management services can be a fixed fee, but it is usually the greater of a minimum fixed fee or a percentage of the gross receipts (effective gross income) of the managed property. The specific percentage is always negotiated or could be a minimum monthly fee. This should be finalized and stated in the agreement to ensure the manager of compensation in case of a shortfall in collections. In setting a fee, the real estate manager should be certain of adequate compensation for the full range of services provided. Negotiating separate fees or commissions may be appropriate for services not generally part of the regular management duties, such as executing commercial or residential lease renewals, and overseeing construction, rehabilitation, or remodeling. With commercial properties, the gross receipts should be clarified in advance since they provide the total cash income from all sources.

After finalizing the management agreement with the owner, the next step is to outline all of the details and include them in the management plan. The management plan should include an analysis of the current physical, fiscal, competitive, and operational conditions of the property in relation to the owner’s goals. If the conditions are not suitable for attaining the owner’s goals, the management plan should be used to recommend and support physical, financial, or operational changes. The management plan also evaluates the feasibility or practicality of plans the owner has for the property. Completing a management plan is an essential start to any new management account since it strengthens the knowledge base of the property being managed.

There is no definitive or standard structure for the management plan because every property is unique in its own way. For some properties, an operating budget and a list of the real estate manager’s observations might suffice. For others, a full and detailed document (that can be hundreds of pages) might be necessary to give a complete perspective on the current condition of the property and the programs required to make its operation effective—or to justify a loan from a financial institution to support the necessary work. Regardless of the size of the plan, the appearance and presentation is always important. Logical assertions and conclusions and clear statements of the facts exemplify the real estate manager’s skills and ability to communicate effectively.

The usual starting point for a management plan is a definition of the owner’s goals for investment in the property. (See Chapter 4 for more details.) The owner’s goals help narrow the scope of the research and recommendations in the management plan. If the owner expects rapid capital appreciation from a property, the management plan may center on improvements that offer a short period for return. Ways to increase NOI are another important inclusion because a higher return from a property increases its value. For owners who want a consistent return from their investment, a schedule should be created that outlines gradual improvements and/or cost saving measures that will ensure a high occupancy rate and create the potential for steadily increasing cash flow. (NOI and cash flow are described in detail in Chapter 6.)

The goal, as exhibited throughout the management plan and the actual management of the property, should agree with and complement the owner’s goal. That goal is usually for the property to reach its highest potential in its current use, meaning that it generates the highest NOI possible and attains the best possible use based on its location, size, and design. When developing a specific management plan, the following evaluations are usually performed:

Location, location, location—it’s the most important aspect of a property’s value. To gain a clear understanding of the effects that supply, demand, and location have on a property, its surroundings must be defined and thoroughly described. Two identical buildings, one located on Wall Street in Manhattan and the other in a small rural town, obviously will have different dollar values even though their designs and structures might be the same. A building’s physical attributes and location are obviously not easy to change. The demand for space in any income-producing property impacts its value as well. The amount of income it can produce depends on the number and quality of the rental spaces of that type, availability of those same rental spaces locally, and proximity to the subject property.

Since value is mostly dependent on location, it’s important to understand the economic, legal, demographic, environmental, and physical conditions that affect a property. After logically outlining the major national concerns, the next phase of the evaluation is with the region.

The regional analysis outlines the general geographic area in which changes in the economic and demographic conditions, as well as geographic features of the area surrounding the property, will impact a piece of real estate. The geographic features relate to environmental situations such as soil contamination and airports or highway access that affects noise issues in specific areas. Those conditions affect occupancy and the demand for space in a particular property. However, when there is an over-supply of any product or service, success is achieved through adapting the product or service to meet existing needs in other ways. Therefore, the recognition and adaptation of poorly utilized real estate is an invaluable skill to possess.

Demand ultimately gives value to real estate. Since people and their economic means create the general demand, investigating this demand will provide pertinent information about the region, especially through collection of historical data and growth projections. The collected data includes the following general demographic profile:

When evaluating these data, seek trends that signal: (1) future growth and opportunity, (2) little or no change from the current conditions, or (3) eventual decline. The government and social climate of a region also greatly affect the value of its real estate, so carefully investigate and analyze these regional components as well.

The Federal Government. The following lists the primary resources from the federal government that provide data for a regional analysis that are helpful when formulating statistical compilations:

The U.S. Department of Commerce and the U.S. Census Bureau produce many statistical profiles in conjunction with federal departments and agencies. The Census Catalog and Guide lists the reports available and their publication dates. A few publications that are especially valuable are the American Housing Survey, conducted every other year in odd-numbered years, and the Economic Census, conducted at five-year intervals in years ending in two and seven. The annual Statistical Abstract of the United States is a compilation of more recent information added to the census data. A fair amount of local data can be found through regional planning authorities.

Commercial Real Estate Brokerage Firms. Numerous real estate brokerage firms compile and publish demographic data in both print and electronic formats. Many of these firms are subsidiaries of companies, such as insurance companies and savings associations that already maintain vast databases. They sometimes combine their data with census results or compare their results with correlative census figures to verify accuracy. The following lists a few major real estate brokerage firms:

Most brokerage firms sort data on the basis of census tracts, city blocks, zip codes, area codes, phone prefixes, or any other specific boundaries identified. Such reports are economical in consideration of the time necessary for compilation—some firms promise delivery of the reports within a few days.

Professional Associations. Professional associations publish property-specific reports for regional, national, and market comparisons. However, the most valuable information within the region itself is available through state and local governmental agencies, utilities, local industries, financial institutions, chambers of commerce, and local economic development agencies. The following lists major professional associations and the specific types of publications they publish:

The next area of research for the management plan is an in-depth study of the immediate neighborhood, or localized area, in which properties compete for prospects. Similar to the regional study in content but more narrowly focused, the neighborhood analysis is an evaluation of data related to nearby sites and the competition—centering on the immediate surroundings of the subject property. Without a thorough national and regional analysis, however, the neighborhood analysis can either be too optimistic or too pessimistic. Just as changes in the neighborhood affect a property, changes in the nation and region affect the neighborhood as well.

Many factors contribute to prospects choosing a specific neighborhood. For instance, mapping sites like Google Maps (maps.google.com) provides basic information about a neighborhood in terms of its geographic and physical features (bridges, walkways, bike paths, traffic information, and any areas with open land) and allow capabilities to virtually walk a neighborhood. Review and recommend websites like Yelp (yelp.com) contain feedback written by consumers about neighborhood businesses; such sites are another possible sources of information about competitive properties or about the specific property being managed.

The following lists other online resources that might provide more general demographic information:

Boundary Definition. Analyzing a neighborhood first requires a definition of boundaries. The neighborhood of a particular property may consist of a few adjacent buildings or it may comprise an area of many square blocks. Neighborhood boundaries are often natural or constructed barriers—such as rivers, lakes, ravines, railroad tracks, parks, and streets—that separate discrete areas that have common characteristics in population or land use. Sometimes neighborhood boundaries are not visually discernible; information can be complied from sources such as the U.S. Census Bureau, municipal and county governments, local government offices, local utility companies, newspaper reports, the local library, the school board, and social agencies to map a neighborhood precisely. Post office as zip codes help define the boundaries as well.

The objective of analyzing the neighborhood is to characterize the population, economic elements, and property types that are dominant. Considerations such as age, education, ethnic groups, income levels, and institutions (colleges, hospitals, etc.) are part of the characterization of a residential neighborhood. The types of businesses (complementary and competitive) and their clientele and employees differentiate the neighborhood of a commercial property; however, many newer, urban developments such as mixed-use properties are built to sustain both housing and commercial business elements.

Physical Inspection. A physical inspection of the neighborhood is also essential. The general curb appeal and overall cleanliness of the area should be inspected to determine whether or not the neighborhood is well maintained. In reporting the analysis, particular features in the neighborhood might be singled out that favor the subject property. In the neighborhood analysis for an apartment building, the location and quality of schools, accessibility to stores, and the level of public transportation service are good items to mention. Important components of the neighborhood analysis for an office building would be transportation, restaurants, and types of business services.

An overall physical inspection should identify comparable properties to study trends in their surrounding area. For office buildings, the micro-market (neighborhood) may encompass just a few blocks or a few buildings. Merchandise categories and price lines of retail operations and the numbers of similar businesses—or their absence—along with a demographic profile of shoppers define the trade area (neighborhood) of a shopping center.

The analytical methods used for the regional and neighborhood analysis are also applied to the property analysis, which includes a careful inspection of the building and a description of its rental space and common areas. Other factors related to analyzing the property are the basic architectural design and the overall physical condition. The following are some of the questions to answer when conducting a property analysis:

One of the most important aspects of the property analysis concerns tenant leases. It’s important to review the status and language of existing leases, which are the basis of the property’s revenue stream. For commercial properties, lease negotiations in progress may be a consideration. Additionally, if leases are not properly abstracted, money can remain uncollected. Abstracting is the process of extracting and condensing the most important terms and financial clauses of the lease into a form that is more easily accessible and understandable. As the leases and their abstracts are reviewed, the lease language might allow for certain common costs to be passed through to the tenant. If those costs have not been passed through, the property’s revenue will be increased by collecting those costs.

In the examination of the property and analysis of the information obtained, keep in mind that the owner’s ultimate goal is usually to achieve the greatest return on his or her investment by putting the property to its highest and best use. At this point, the information gathered in the regional, neighborhood, and property analyses have been described, but the next and most essential component of the management plan is the market analysis.

The term real estate market has different meanings in such diverse aspects of real estate as mortgage interest rates, development, property cost, property value, rental rates, and even property amenities. All of these, except mortgage interest rates, relate in some way to the level of competition and the demand for rental space in a particular property. A market analysis evaluates the supply and demand conditions for rental space in a specific building in comparison to the demand for space in other competitive buildings—along with details like rental and vacancy rates. The market analysis gathers information about specific comparable properties and compares their features to the subject property.

Once the features are described, the advantages and disadvantages can be evaluated accordingly. The market analysis should only focus on competing buildings within the neighborhood and the region based on the information derived from the regional, neighborhood, and property analyses. After comparing the property to its competitors and analyzing the region and neighborhood, conclusions can be made to identify factors that affect, or could affect, the performance of the subject property. This study is conducted based on the current condition of the property.

The four principles of conducting the market analysis are essentially the same for all types of property: (1) find which properties are competitors, (2) complete a comparison grid analysis to compare the subject property to the competition, (3) set the correct rental rates based on the comparison, and (4) write a narrative report.

Define the Competition. Buildings in direct competition with the subject property obviously define the competition. To find which buildings are legitimate competitors, examine the subject property at the submarket level, which is a segment of the overall geographical area limited by a particular market factor—office, retail, industrial, apartment, or single-family home markets. This property categorization reduces the focus and number of potential residents and, thus, potential competitors. In some cases, ask prospects which other buildings they are considering. If a prospect is lost to a competitor, figure out why.

Other factors narrow the field even further. Prospective residents usually locate in one portion of the region by limiting their search to the part of town they prefer. They also commonly search for a particular type of rental space—households of three or more are obviously not interested in studio apartments, convenience store owners do not seek supermarket-sized spaces, and couples often make decisions based on a shorter commute if a suitable accommodation cannot be found at a midpoint.

Because prospects narrow their focus, narrow the focus of the market analysis to determine the true competition. The subject property is compared to similar properties in the neighborhood or general vicinity—not compared to property across town or in another region. However, even if a property across town is not in direct competition with the subject property, its standing in the market will have an influence because it is a part of the market as a whole—the narrative description of the market accounts for this influence.

Since the facts learned in the regional and neighborhood analyses basically indicate which buildings are in direct competition with the subject property, compare their features and amenities and rate them appropriately. The same concept applies to the property type—different information is needed for residential properties compared to commercial properties. The sections below describe the specific information that should be gathered for each type.

Residential Markets. Prospective residents are looking for the perfect new home and their expectation is that it will contain one or more specific qualities or characteristics. Each of these elements can be allocated to a dollar value. The prospect will pay a certain amount to have a feature a competitor does not, or the prospect will do without it if the price is appropriately adjusted. For this reason, when comparing the subject property to the competition, list those influential features and amenities that might persuade a prospective resident to sign a lease. The following considerations pertain to most residential markets:

Commercial Markets. The following lists the types of property characteristics to compile for commercial spaces when learning about the market:

When conducting the market analysis, many questions should be asked. How do the rent and occupancy trends compare with real estate market trends in general? How do vacant apartments or commercial spaces in the area compare to those in the subject property with regard to size, age, condition, amenities, and rents? Based on the results of the neighborhood analysis, is the number of prospective tenants for the subject property increasing or decreasing? Is the absorption rate—the amount of space leased compared to the amount of space available—positive or negative?

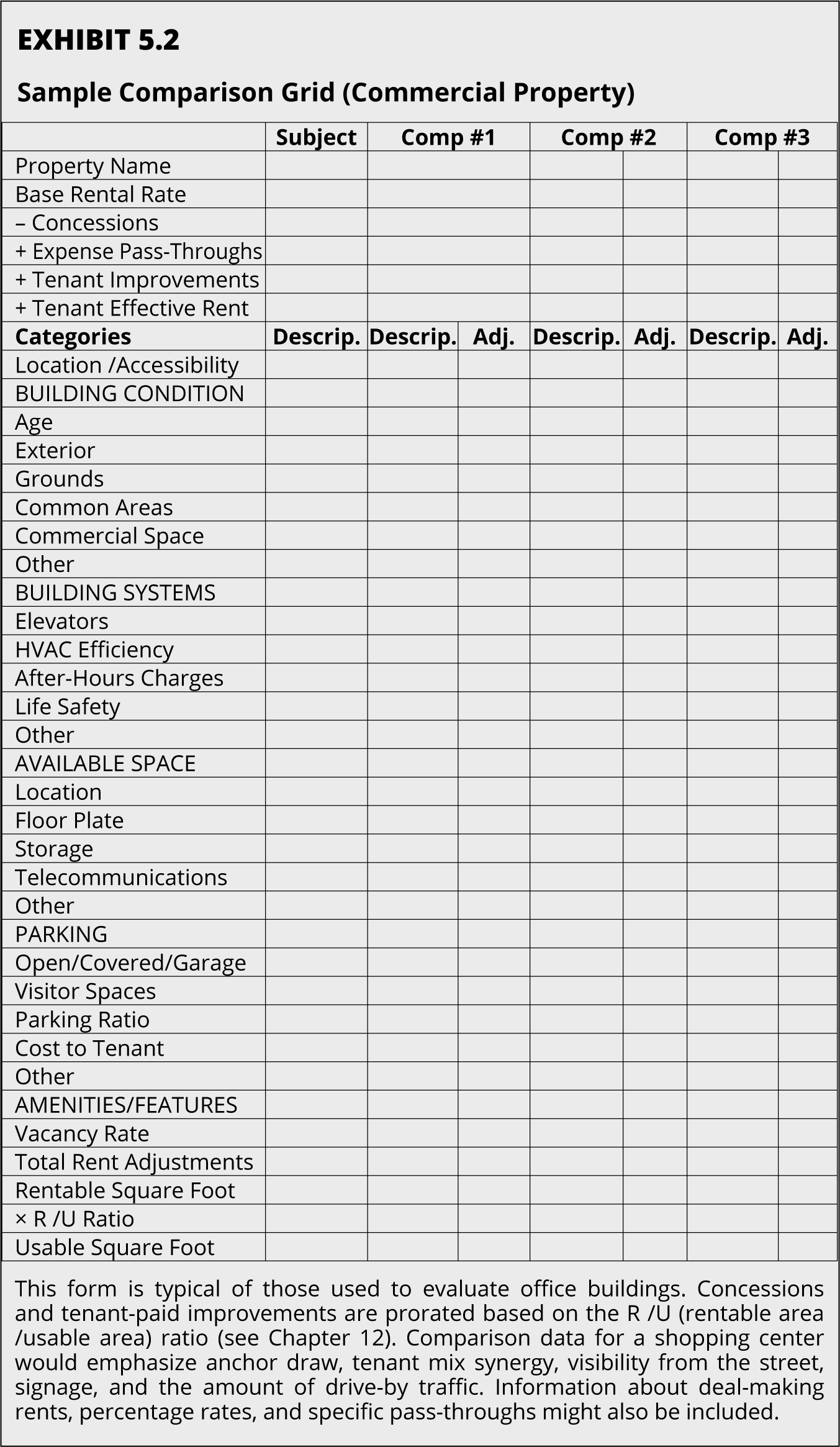

Complete a Comparison Grid. To make an effective comparison, categorize the features of the competitive properties with respect to the subject property using a comparison grid (Exhibits 5.1 and 5.2). Specific features are listed at the left, and the comparable properties are indicated as column headings. Most of the categories are straightforward, but some might require additional explanation. A “pets allowed” category may be listed as a straight “yes or no” for most residential properties, but some apartments may have very specific provisions—separate pet agreement, additional rent, or fees. For commercial properties, rental rates account for additions to base rent—operating expenses and percentage rent—and a comparison of major and minor space users should also be included.

When completing the comparison grid, consistency in rating or ranking is most important. In preparation of the comparison grid, use the same rules of assessment for each category of analysis for all properties. Describing and rating “location” on the comparison grid can be difficult, yet the location of a property within the neighborhood is its prime marketable feature. Keep in mind there is no standard for a good location. For instance, being a block from a supermarket or a mass transit stop would ordinarily be a promotable feature for a residential property, but being next door to the bus depot or to the parking lot of the supermarket would not. On the other hand, being next door may be more attractive than being three miles away from those amenities. Location next door to a hospital is a selling point for offices designed for physicians and allied health professionals, but it is a detriment for industrial space with heavy incoming and outgoing truck traffic. Being near a courthouse is a desirable feature for space usable as law offices, but that location is not a selling point for stores seeking high-end retail tenants.

Because most factors involving location are relative and complex, a separate location analysis can help evaluate how the property’s location affects demand—Exhibit 5.3 lists some of the factors that influence prospective tenants’ perceptions of location quality.

Comparison grid analysis determines how the rental space in the subject property compares to similar space in the market on a feature-by-feature basis. The purpose is to show whether a particular feature at a comparable property is better than or not as good as the same feature in the subject property and how the total of these features affects quoted rents. By attributing a dollar value to each feature, a market-level rent can be determined for the subject property based on the comparison. If the feature in the subject property is better than in a comparable property, the rent for the comparable is adjusted upward. If the feature in the subject property is not as good, the rent for the comparable is adjusted downward. The adjustment amount, whether it’s negative or positive, is based on what a resident would pay for the feature or would not pay because of its absence. For each property, the adjustments and changes to the rental rate are totaled to reflect the net adjustments. Finally, the rents for the comparable properties are analyzed to determine a market rent on a per-unit or a per-square-foot basis. Typically, a comparison grid analysis is completed for each type of apartment unit in a residential property.

Set Rents. Evaluating the quoted rents and occupancy levels of the competing rental apartments or commercial spaces helps to determine the rent that the owner should charge for the subject property—based on quality, services, amenities, and other attractions. The comparison grid also indicates whether the rent for the type of space in the subject property is below, at, or above market rates. Based on this information, the current rental schedule of the subject property can be evaluated and compared it to the rental schedules of other properties on the comparison grid.

To determine whether to adjust the current rental schedule of the subject property, there must be a search for an optimum balance between vacancy and maximum income. While the ideal is maximum rent and maximum occupancy, reality dictates that vacancies will be present. In fact, an increase in rent may initially increase vacancies. With this in mind, a realistic maximum rent should be chosen that will minimize the impact on the occupancy rate. Rents and vacancies are important considerations in estimating changes in gross receipts and NOI that will result from an increase in rents. The prices are then applied to each unit or space according to its location, view, and amenities.

Write a Narrative Report. The market analysis generally includes a narrative overview of market trends and observations, such as the evaluation of the absorption rate and regional and neighborhood trends, including population changes.

Absorption Rate. The absorption rate in the neighborhood or region usually warrants discussion. The absorption rate of a property type is the amount of space leased compared to the amount of space available for lease over a given period—usually a year. The rate relates to both construction of new space and demolition or removal from the market of old space. Different property types within the same region have different absorption rates.

If demand exceeds supply, the absorption rate is favorable because overall vacancy decreases. If supply exceeds demand, the absorption rate is unfavorable, and lenders tend to curtail their financing of the development of similar properties, which eventually causes a slowdown of growth. A negative absorption rate can also result from other changes in a market. If a major industry closes and not enough jobs are available, people will move away from the area, and the lack of jobs will discourage others from moving in. The amount of residential space available for lease will quickly exceed demand—irrespective of any new construction. The commercial sector may also slow down based on this major change. However, the effect of reduced demand is not always immediately apparent. Construction might continue because the financing is in place. If the developer obtained financing when the level of demand was high, market trends may be unfavorable when construction starts, and stopping construction may cost more than completing the project. As the new space fills over time, demand will again exceed supply and the absorption rate will again be favorable—encouraging new construction and causing the cycle to repeat.

Trends. The narrative portion of the market analysis includes trends observed in the regional and neighborhood analyses that can affect the subject property. For a residential property, a shift in the demographic profile of the neighborhood (for example, from families to empty nesters) would be noted here—along with conclusions regarding the favorable or unfavorable effects that shift may have on the demand for rental apartments. If the regional analysis showed that a nearby company, such as Boeing or Microsoft, would be expanding its operations and hiring more people, it could be presumed that demand for rental space will increase. And with further reasoning—based on the comparison grid—the competing buildings in the neighborhood are better suited to profit from the anticipated population growth.

Population changes also affect the leasing of commercial space. Education levels and technical skills determine the caliber of potential office workers. Household income levels indicate the price levels of merchandise that will sell in a particular area—Bloomingdale’s and Nordstrom obviously offer different price lines than do Target and Walmart. These considerations should guide the development of a marketing program for the property that will capitalize on any positive trends and insulate the property from the impact of negative trends. (Chapter 8 provides more information on marketing.)

Many management plans conclude with the market analysis. The research to this point can substantiate a need for a new rental schedule and indicate the increase that the property can attain without compromising its competitive strength. In other words, if implementation of a new rental schedule alone will place the property in a condition of highest and best use—enough said. However, many properties, particularly commercial properties, demand a more comprehensive examination of their future prospects.

Data evaluation essentially determines three major factors about the property: (1) what management direction to take, (2) what conclusions are justified, and (3) what recommendations will ultimately be made to the owner. A neighborhood is not a static environment—it changes continually and its changes can affect the property in numerous ways. Always examine the changing neighborhood conditions, include definitions of those trends in the neighborhood analysis, and explain why they are occurring. The changing numbers of individuals in different age and income groups and changes in household sizes indicate population shifts. Fluctuating real estate sales prices and rental rates, along with the amount of vacant space, which are readily ascertained in a physical inspection, reflect economic shifts. Differences in types of property development (new vs. renovated), changes in land value and use, rental rates, and vacancy rates are other indicators of specific trends.

If results of the neighborhood analysis seem incomplete or uncertain, always investigate further. A complete and fair perspective is essential to an accurate market analysis. Population growth often indicates prosperity for a neighborhood such as leading to higher occupancy, but it can also signal the reverse. For example, an excess of vacant commercial space may be the result of new development in response to increased demand or a sign of challenging economic times. In established properties, vacancies can signal an inability to support retail and other businesses—leading to even more vacancy. With the numerous sources available for data, it would be unwise to predict a change in land value from a single statistic. Evaluation of its cause in the context of other specific statistics is essential to understanding a particular trend and its impact on value or even use.

It’s important to continually monitor current trends to know whether conditions are improving, staying the same, or declining. These trends can signal the need to modify the way the property is managed, while continuing to meet the specific goals and needs of the owner—improving conditions may lead to increased market rents. Staying the same—perhaps adding new amenities for tenants—might help retain or improve occupancy. If conditions are declining, perhaps improvements to the physical aspects of the building may lead to other property owners in the area improving their buildings—thereby reversing that trend. Further, current trends may signal the need to project future trends, which lead to a variety of new conclusions and recommendations that can prepare the property owner for the coming changes.

Some properties require changes in operations or some form of physical change to justify a rent increase. Examples are elevating the occupancy level, controlling expenses, and subsequently bringing such properties to their highest and best use. In the effort to improve the performance of a property, investigate the range of possible changes and evaluate their anticipated effects—in other words, conduct an analysis of alternatives. The intent of the changes proposed in this section of a management plan is to increase NOI, which is the tangible and measurable benefit of the investment in the property, and thereby to increase the property’s value. Each proposed change carries with it a cost, so the analysis will compare the costs and the benefits of each proposal or combination of proposals made in the analysis of alternatives.

In some instances, improvements to real property may preserve value rather than increase income—upgrading an HVAC system and replacing a roof are examples. Ignoring the needed improvement could result in decreased rents, lower occupancy, increased operating expenses, and a lower property value. Preserving value and the capital invested in the real estate are important to every investor. Such investments in capital improvements also warrant a cost-benefit analysis because their costs may be factored into the residents’ rents or result in reductions of operating expense increases—and the owners will need to know how long the payback period will be until they recoup their investment. Some capital improvement projects are the financial responsibility of the owner, while others can be passed through to the tenants—raising operational expenses that the tenants pay.

In analyzing alternatives, consider potential operational and physical changes. Operational changes are procedural, whereas physical changes can range from rehabilitation or modernization of the current building to outright change in the use of the building or the site.

Operational Changes. These changes affect procedural methods or efficiency but not the physical makeup of the property. The net effect is to increase income or reduce operating expenses and thereby increase NOI. Operational changes range from adopting a new rental schedule based on the market analysis to using low-wattage bulbs in common-area lighting. Strategies to reduce outside service expenses include renegotiating contract terms with certain service providers, such as elevator maintenance, or calling for bids on recurring services that are not under contract—landscaping or parking lot sweeping. Along with reducing expenses, it’s important to keep in mind the numerous enhancements and improvements of operations as well. Many residents and tenants actually place a value on the efforts made to sustainable changes to the property. It attracts attention and has the potential to gain more residents. It’s important to keep in mind that investors will want to see a return for the risk they take in greening their assets, for improving sustainability, and in achieving particular levels of accreditation on the environmental performance of their buildings. Although the intent of operational changes is to reduce operating expenses, the property’s quality is what always needs to be maintained. After completing the market analysis, it’s important to be acutely aware of the services provided at competing properties. Any recommendation that sacrifices any similar services may be more costly than the savings achieved. However, examination of the competition may lead to the discovery of new methods that will reduce operating costs yet preserve or enhance service standards.

Structural Changes. Rehabilitation and modernization can lengthen the economic life of a property. Rehabilitation is the process of renewing the equipment and materials in the building—it entails correcting deferred maintenance. Modernization, the correction of functional obsolescence, is inherent in the rehabilitation process. To make the property competitive, similar equipment of more modern design will replace the original equipment. New carpeting, wood floors, upgraded electrical service, Wi-Fi, equipment that is more energy efficient, or any other physical improvement that does not affect the use of the property can be rehabilitative. The list of possibilities in this arena is virtually endless. When physical changes are proposed, the management plan must include an expense budget and/or a capital budget showing the allocation of funds for the changes and the anticipated return on investment, impact on NOI, cash flow, and property value. The owner may also require an analysis of debt service—if the funds are borrowed—and cash flow.

Changes in Use. A recommendation to change the use of a property must be well founded since changing the property is complex, expensive, and therefore, not typical. However, the rewards of a successful change in use are often substantial. Once a change of use is implemented, reverting to the original condition is clearly difficult. The property owner should carefully weigh the anticipated improvement in performance expected from a change in use against the risks of that change. The most common changes include adaptive use, condominium conversion, and demolition for new development.

Adaptive Use. Adaptive use (or recycling) of existing structures is usually more economical than building new structures. Capitalizing on an existing shell and foundation eliminates the cost of demolition and part of the cost of new materials. Old factories, warehouses, train stations, and post offices have gained new life as offices, shopping centers, apartments, and entertainment complexes—some office buildings have become hotels and condominiums.

Adaptive use is a way to reduce development costs to meet new market demands, preserve historical architecture, or revive a location that is not achieving its highest and best use. A recycled building may not achieve the same rent per square foot as a new one, but the initial costs are lower and the debt service requirements are usually less. Adaptive use projects make sense when cash flow per square foot will be greater than the cash flow from the original use. Old buildings, whole city blocks, and even sections of towns have been preserved and made profitable through adaptive use.

Condominium Conversion. The primary advantage of condominium conversion is the potential to achieve a high profit in a short time. The appeal is even greater when cyclical changes or market conditions cause increases in financing costs, which always reduces cash flow. Converting a rental property to condominium ownership allows the original owner to recapture their investment, pay off the mortgage, and keep any excess funds as profit. If rent control restricts a property owner’s ability to increase rents to market levels, condominium conversion may circumvent the potential loss of income, although current renters may have the right to remain despite the conversion. Review of state and local laws regarding condominium formation and conversion is essential to determine the feasibility of a particular conversion.

Although condominium conversion was once limited to apartment buildings, the concept has extended to other property types—even parking lots in congested metropolitan areas are sold by the parking space. The success of a condominium conversion depends on the adaptability of the building to the form of ownership. In most cases, the building and all of its components must be in the best possible condition for the property owner who is doing the conversion to achieve the greatest possible return on their investment. The property owners must also consider the fact that a condominium is a long-term financial commitment for the buyer—a prospective owner is usually more selective than a prospective renter. It’s important to understand that investors think about selling their assets even at the time they are buying them—they need to perform due diligence, which ensures that the offering statement does not misstate or omit pertinent information during the examination of a property. Owners understand the properties they’re investing in and the investment classes they intend them to be. In fact, owners should set goals for the property as soon as possible. They determine the projected sales price they might obtain from another investor or converter and whether doing the conversion themselves would be most profitable or even possible, considering their skill sets. Market conditions may require the reverse as well.

Demolition for New Development. Demolition may seem to be an easy alternative, but it can be very expensive. The cost of demolishing a building along with the cost of building a new one increases the necessity for the new structure to generate a high level of income. In some cases, a proposal to demolish a building—even if it is in serious disrepair—can lead to a public outcry and tarnish the image of the new structure. For instance, if a site is listed in the National Register of Historic Places, demolition of the building is prohibited. The decision to demolish an old building and replace it with something new requires thorough review of more than the financial aspects. The impact on the neighborhood and the possible loss of goodwill are also important considerations. In addition, the new building would need to conform to today’s building codes and standards; that is not always required with minor remodeling of existing buildings.

Since changing a property always involves costs, the amount and extent of the costs depend on the scope of the changes. Establishing a new accounting procedure, or other operational change, might only require training of staff and replacement of certain software—regardless, these have measurable costs. Rehabilitation and other structural changes are costly and can cause interruption of part or all of the rental income while the work is done. Even a recommendation to maintain the status quo has to be justified financially.

In order to determine whether a specific recommendation will improve the property’s income, a cost-benefit analysis will need to be conducted, which involves the evaluation of each alternative to ascertain which would yield higher levels of NOI and cash flow than the property would yield if left unchanged. Recovering the costs of making the change, plus any financing, is also an issue. Clearly, the benefit of increased NOI and property value must outweigh the cost if a recommendation is feasible. To determine this, the payback period will need to be evaluated—the amount of time for the change to pay for itself. The cost-benefit analysis should also show the potential increase in property value from the improvement. (Exhibit 5.4 shows an example of a cost-benefit analysis.)

Finally, while the conclusion and recommendations may be sound and easily undertaken, property owners will ultimately make the final decision based on their personal financial goals, desired holding period, or other factors. Determination of the highest and best use, however, is a necessary exercise that, while perhaps not immediately implemented, will make small changes or improvements that may help guide future decisions.

Management plans can be long and complex, so there are certain ways to make the document easier to follow. For instance, recapping the major conditions that affect the property and including a summary of the primary recommendations are helpful ways to make the document clear and concise. Essentially, the management plan should include the rationale for specific changes and the expected results, along with a clear statement of the anticipated long-term financial performance—the effect on the bottom line. The main objective is to be sure the owner understands the reasoning behind the management plan. Highlighting this information in an executive summary at the beginning of the document (instead of placing the summary at the end of the report) will help guide the owner through the document. Recommendations that relate to only one area of the property’s operation may not require a complex management plan. A market analysis may suffice to assess the condition of a property and recommend maintaining status quo. However, any proposed change, including a change in rental rates, requires a cost-benefit analysis.

The management objectives of each owner for each asset will always be unique, but a well-written management agreement and management plan will spell them out. Both documents are integral to defining how the property should be managed and the responsibilities for both the real estate manager and the property owner; they should be considered carefully and in great detail to ensure the future success of the business relationship. Since the management agreement is a formal contract, it should clearly outline the real estate manager’s responsibilities and the owner’s obligations, while authorizing the manager to operate the property on the owner’s behalf.

It’s important to remember that the owner is ultimately responsible for the property. The real estate manager must know how to assess a property’s potential and how to explain that assessment through a management plan. Evaluation of the data on the region, the neighborhood, and the property itself forms the basis for an analysis of the property’s current market position. Assessment of the property’s structural integrity, operating history, rent levels, and other factors indicate whether change is necessary to bring the property in line with market demand. Every change proposed to improve profitability involves a cost, which must be evaluated. Altogether, preparing clean, well-organized documents is essential for maintaining a strong sense of professionalism and establishing the foundation for a professional career in real estate management.

1. Agency relationships and independent contractor are not mutually exclusive. Most companies are independent contractors and legal agents for the property owner.

2. Operating accounts are accounts from which property invoices and deposit rents are paid. These can be trust accounts or a regular account over which the real estate manager has signature authority.

3. This is an evolving issue with the predominance of property management software, which allows the owner to have access to all records at any time. The real estate manager should include in the agreement that, if the owner pulls information from the property records during any accounting period, the owner understands that he or she is viewing unadjusted records that may need to be changed prior to the issuing of financials.