Financial management goes beyond simple recording and reporting. It includes well-informed income and expense projections in the form of operating budgets and analyses of any variances. These reports serve as a basis for analyzing the efficiency of property operations and help to drive profitability. In a world of fiscal transparency standards and competing institutional asset investors, real estate managers are being asked to adopt business practices from the financial services industry. Though it may sound challenging, operators are assisted by technology to streamline decision making and operations, enhance performance, and optimize investor returns. With the quickly growing popularity of revenue management models, even more data points are available for analysis beyond the traditional operating reports.

Income and expenses must be promptly and accurately recorded in order to relay the financial status of the property to the owner. For most rental properties, cash receipts and expenditures relate to one of three categories: (1) normal day-to-day operations (recorded in the income statement); (2) reserves (that may include capital improvement costs); or (3) security deposits (recorded in the balance sheet).

Funds received and disbursed should be recorded in a property management software solution—a business intelligence system that integrates property tasks, compiles property data to analyze asset performance, and produces reports to be shared with the property owner(s). Upon review of receipts and disbursements, there may be operational items that need to be changed or improved—these actions will help increase the net operating income (NOI).

For any income-producing investment, the measure of its success is the amount of return to the investor. For rental real estate, the most important measures are NOI and the cash flow that results from efficient operations. NOI and cash flow are derived from many contributing factors and events.

There are specific terms used by the real estate management industry to identify the various types of income and expense relative to cash flow. The following chart shows the relationship between income and expenses:

The owner’s assessment of the property’s investment return is usually based on before-tax or after-tax cash flow. The following sections define the components of cash flow.

The maximum income, regardless of occupancy, the property can earn from rent is its gross potential rental income—not to be confused with gross potential income (GPI) which is the absolute sum based on 100 percent occupancy. It is a statement (or financial inventory) of the amount of income the owner would receive if the building were fully leased at their current rental rates and all tenants paid rent in full, on time, and without offset. It does not indicate income actually received. Once established, this figure remains fairly constant from month to month. The only factors that affect gross potential rental income are changes in rental rates or in the space available for rent.

Changes in rental rates occur most commonly when leases are renewed or when new residents or commercial tenants move in. Changes in the leasable space are more complex. Older buildings may have storage and other areas that are unleasable. Yet, if those areas can be made leasable, the income they generate may be listed as additional rental income and contribute to the GPI at that time. For example, in an older office building, the maintenance department may currently store supplies and equipment in space in the basement that originally contained offices. While the space may no longer be usable for offices, it may be leasable to current tenants as space for storage of their supplies and records. If the space is converted to leasesable space, any scheduled rental income from the space should be itemized as additional rental income or included in miscellaneous income. Alternatively, the conversion of a basement apartment into a laundry room reduced the building’s leasable footprint; however, a common area, unleasable for occupancy was formed. Any revenue from card- or coin-operated washers and dryers would be reported as ancillary income.

New developments often have a model unit, which is classified as unleasable during this time. Although models are usually in move-in condition, they are considered unleasable since they are not generating revenue and are not readily available for move-in. Model units are not typically in place when demand outpaces supply.

Gain/Loss to Lease. The amount of income gained or lost due to rental rates being higher or lower than the maximum market rents (or GPI) is loss to lease. This measurement is important when evaluating a property in a rising market to project future rent increases. For example, consider an apartment building that has 10 leases. In 2007, they all rented at $750. At the start of the 2008, the market rent (GPI) rose to $1,000. However, only six of the leases were up for renewal at the start of 2008. Those six rented for $1,000. The other four under the old lease continued to rent at $750. As a result, the loss to lease comes out to $250 per month for each of the four leases. The opposite can happen with gain to lease—if the existing rents are greater than market rents.

Vacancy, Concessions, and Collection Loss. The actual rent received is rarely equal to the gross potential rental income. Vacant space produces no income, and rents not collected represent lost or delayed income—both reduce the rent collected. In the cash flow chart, vacancy and collection loss is subtracted from gross potential rental income to indicate the actual amount of rental income for a given reporting period—usually a month. Most real estate managers list vacancy losses and delinquent rents separately. When finally paid, delinquent rent is added to the income category and not considered a true loss of income, whereas nonpayment of rent is a true loss of income. Although vacancies represent a loss of income for the period of time they remain vacant, they optimistically do not represent a total loss. Instead, vacancies simply reduce gross potential rental income until they become occupied.

Effective Gross Income. Subtracting the vacancy, concessions, and collection loss amount from the gross potential rental income yields the effective gross income of the property.

• Space that is leased but does not yet produce income. A resident may rent an apartment in August, but the rent payments may not begin until October. Commercial space is often leased in an unfinished condition (tenant improvements must be completed in order to occupy the space); rent payment (which may include reimbursement of tenant improvement costs) usually begins after construction is complete and the tenant moves in.

• Delinquencies. If a resident or commercial tenant is behind in rent payments, the unit or space is classified as occupied, but it is not producing income.

• Leasable space that is used for other purposes or is otherwise unleasable. Spaces used as models for leasing purposes, manager offices, or storage space; apartments provided as compensation to staff members who live onsite; and apartments or commercial spaces that are not in fit condition to be leased or occupied.

Miscellaneous Income. Although the cost of rent provides the vast majority of income, most income-producing properties receive some additional or ancillary income. Income derived from sources other than scheduled rent, e.g., coin-operated laundry equipment, vending machines, late fees, is categorized as miscellaneous income (or unscheduled income). Other related sources of income include installations (e.g., air rights, interior building wiring), leased storage space, storage lockers, parking or garage rental, and express shipment drop boxes. Unscheduled income may also include previously unpaid rent that is recovered after a tenant no longer occupies the rental space, usually after the matter has been turned over to a collection agency or an attorney. In addition to these unscheduled payments, pass-through operating expenses—common area maintenance (CAM) and taxes that the owner charges to the tenants—are taken into account as miscellaneous income.

For commercial properties, any miscellaneous items are classified as scheduled income in a separate line item since these expenses are estimated in the budget and are paid by tenants as “additional rent.” Delinquent operating expense reimbursements are treated the same as “base rent” in most commercial leases; therefore, a commercial real estate manager can take action in the same manner as they would for base rent delinquencies. Altogether, miscellaneous income may be generated for the property, but on the whole, it is a very small amount in comparison to the income derived from the rental of tenant and resident space.

Total Income. Adding miscellaneous income to effective gross income generates the total income of the asset. This figure should match the total amount collected (gross receipts) during the reporting period. In this respect, the effective gross income total can help verify the accounting for the rent and other receipts from miscellaneous income during the accounting period. Effective gross income—which can vary substantially from the gross potential rental income for the property—is the amount that is available to pay building expenses, annual debt service, and a return on the owner’s investment.

Any expense associated with products or services required in the operation of the building are the property’s responsibility to pay. Everything related to maintaining the condition of the property and providing services to its occupants (with the exception of debt service) fits into the category of operating expenses. Such items include payroll, office supplies, maintenance, repairs, groundskeeping, utilities, decorating, and security. Owner expenses such as insurance, real estate taxes, and fees for legal and accounting services are also considered operating expenses, and they are passed through to the tenants. (The section on accounting discusses categories of expenses in more detail.)

One objective of tracking operating expenses is to calculate how much of the effective gross income remains after payment of the bills; keeping this figure at a consistently high level is important. Real estate managers and owners compare operating expenses as a percentage of effective gross income to industry statistics—a measure of the effectiveness of the financial management of the property.1

Net Operating Income (NOI). The remainder, after deducting Operating Expenses from Effective Gross Income, is the NOI—an objective measure of the financial performance of the asset. Overall property value is a ratio of NOI and capitalization rate; therefore, higher NOI produces greater property value. Maximum NOI is achieved through optimization of income while controlling expenses. Any variance in effective gross income, operating expenses, or both will cause NOI to vary. As part of management services, operating expenses are paid from NOI.

Annual Debt Service (ADS). An owner’s performance evaluation of a property does not end with NOI. The annual debt service (ADS) obligation of a property—the amount required to repay the mortgage—is deducted from NOI. Although this amount is a recurring expense, it is not an operating expense. An owner will want to know if a property will generate enough cash to service the debt and provide a satisfactory return on their investment. In some instances, real estate managers handle the payment of debt service for the owner—other owners prefer to make those payments themselves. Determining who makes the debt service payments is a point subject to negotiation in developing the management agreement. (More information on the management agreement is explained in Chapter 5.)

Cash Flow. The amount remaining after subtracting debt service and capital expenditures, leasing fees (for commercial properties), etc., from NOI is the cash flow (Exhibits 6.1 and 6.2). When the required debt service payment exceeds the amount of NOI, the cash flow is negative. Cash flow is the owner’s before-tax income and one measure of return on investment (ROI).

Two important payments are made from the cash flow of the property. These are contributions to the (1) reserve fund and (2) personal income taxes. Reserve funds are monies set aside to accumulate for future use; capital expenses that are passed through to tenants are included in operating expenses and reduce NOI. However, capital expenditures for improving vacant space for occupancy would be below NOI and only affect cash flow. The owner’s requirements and the property’s tax situation determine these items. For example, homeowners’ associations (e.g., in condominiums) are required by law to maintain replacement reserves—institutional owners typically do not accumulate reserves.

A property owner generally calculates and pays its income tax. Depending on the management agreement, the after-tax cash flow received by the owner may be the same as cash flow. In fact, if the owner has no debt on the property, or if the annual debt service (ADS) is paid directly by the owner and a reserve fund is not maintained, cash flow is the equivalent to NOI.

Investment return may be expressed in dollars (cash flow) or as a percentage. The percentage rate is often referred to as return on investment (ROI) or cash-on-cash return. The percentage of ROI is calculated by relating the annual NOI from the property to the dollar amount of the owner’s initial cash investment. The formula follows: NOI ÷ initial cash investment = percent return.

If an investor purchases a property with $100,000 down and the property produces an annual NOI of $10,000, the result is a 10 percent return.

The same formula can be used to calculate ROI based on pretax or after-tax cash flow. This is a very basic description of the calculation of ROI. For many real estate owners, the calculation is more complicated; such calculations are studied extensively in the IREM courses on Investment Real Estate Financing and Valuation.

The amount of the annual debt service depends on how much cash the owner used to purchase the property and the terms of the mortgage loan. The property owner may ask for an evaluation of the loan terms—based on current rates in the market—to consider whether the owner or the property could benefit from refinancing the debt. Fiduciary responsibilities to the owner include evaluating alternatives and making recommendations to increase an owner’s return.

Depending on the current market, an owner may be able to refinance an existing loan at a lower interest rate, for a longer term, or for a larger or smaller principal amount. Sometimes refinancing will lower the amount of periodic debt service payments, thereby increasing the before-tax cash flow and producing a higher return on the owner’s investment. Taking equity out of one property allows the investor to diversify holdings and perhaps purchase a an additional property for the management portfolio. Conversely, some investors prefer to be more conservative and keep the equity in their property as high as possible. Therefore, it is extremely important to know the owner’s investment style.

Regardless of the property’s price and whether the owner purchased the property with cash or borrowed funds, the property’s NOI will be the same. The constancy of the NOI of an income-producing property, therefore, makes that sum a definitive measure of the property’s market value. Because of that constancy, the value is easily measured against that of the property’s competition as well.

Property Valuation. Maximization of NOI, regular repayment of debt service, and satisfactory return on the investment while maintaining or improving the physical property will increase the likelihood of a management agreement renewal. The level of NOI represents more than the owner’s return on investment—it directly affects the value of the property. It’s important to have a continued focus on the greater success of the properties. Do not ignore required maintenance or raise the rent strictly in pursuit of increasing NOI in order to acquire a management agreement renewal.

One method of calculating the estimated market value of income-producing real estate is the income capitalization approach. It is important to note that cap rates can be acquired, which can be obtained by talking to various brokers—in that case, they can be subjective and generalized. Actual cap rates can be based on the NOI and sales price of a recent sale, among other methods.

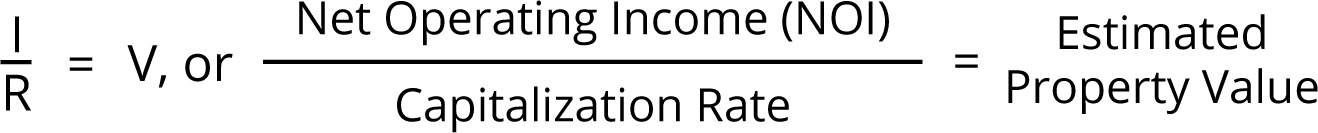

Using the income capitalization approach, estimated market value (V) is calculated by dividing the annual net operating income (I) by a capitalization rate (R) as indicated in the equation that follows. The capitalization rate or cap rate is a decimal constant.

As an example, if the cap rate is 10 percent and the annual NOI of a property is $100,000, the property’s estimated market value is $1 million ($100,000 ÷ .10 = $1,000,000). The same property valued with an 8.5 percent cap rate ($100,000 ÷ .085) has an estimated value of $1,176,471. The lower the cap rate, the higher the value. The higher the cap rate, the lower the value.

Conversely, if a neighboring property sells for $2.4 million and has an NOI of $200,000, the cap rate can be determined ($200,000 + $2,400,000 = 8.33 cap rate). Using the IRV formula, if two of the three numbers are available, the third number can be determined. If a property is similar in type, size, amenities, etc., using 8.33 as a cap rate to value, the similar property would be a fair estimation of its value.

Investors and brokers use cap rates to determine the potential return that a property will produce. An owner whose goal is to preserve value has a much different (usually lower) expectation of a return on investment than one whose goal is capital appreciation.

The cap rate for a specific property depends on the property type, recent sales of comparable properties in the area, and market conditions, including interest rates. Variations in the cap rate have major effects on value—which declines as the cap rate rises.2 Cap rates are determined by the market, not the investor. Therefore a real estate manager can influence value only by improving a stabilized NOI, not by adjusting the cap rate.

When the same cap rate is used in a comparison of similar properties in a market area, the property with the highest annual NOI will have the highest estimated market/property value. If the NOI of a property decreases and the cap rate does not change, the property value will decrease—this is in addition to the reduction in periodic income resulting from the lower NOI. On the other hand, any factor that helps to increase NOI also increases property value. For example, a rent increase of $100 per month on one leased space equates to an additional $1,200 annually to NOI. Market and/or property value is calculated based upon 12 months of revenue. At a 10 percent cap rate, that increase in rent improved the property’s estimated market value as follows:

The following demonstrates a dramatically positive financial impact that the real estate manager wields in impacting the value of a property:

For example, a 200-unit apartment building with an NOI of $500,000 and a capitalization rate of 8% yields a value of $6,250,000. A rent increase of $10 per month each month from each resident will boost the value of the property 4.8% ($230,000/$6,250,000) to $6,555,000.

Income Tax. Real estate managers may have no involvement whatsoever in the tax paid on the income generated by a managed asset. However, due to the growing complexity of income taxation and its effect on real estate ownership, a basic understanding of taxes is needed. Income taxes on profits from real property ownership usually are levied against the individual investor’s personal income. Stated very simply, if an owner’s taxable income from a property is $10,000 and that amount is subject to tax at a 28 percent rate, the amount of tax owed is $2,800 ($10,000 × .28). Assuming a before-tax cash flow of $15,000, the after-tax cash flow would be $12,200 ($15,000 – $2,800). Because each individual’s tax obligations are different, only an estimate of before tax cash flow (BTCF) can be calculated. Professional tax accountants and attorneys can best advise an owner regarding the taxes on investment income and the resulting after-tax cash flow.

Reserve and Security Deposit Funds. The operating funds of a property that determine NOI are usually the most extensive and require the most attention, but reserves and security deposits also need continual monitoring. While operating funds may not always be in an interest-bearing account, reserve funds sometimes depend on regular earnings for part of their value. Depending on various state and real estate licensing laws, security deposits must be maintained and accounted for separately. In Oregon, for example, security deposits must be recorded, but they can be sent to the owner as a return on their investment. In that case, the security deposits are listed as a liability on the balance sheet. It is critical to know the different federal, state, and local licensing and accounting laws.

Reserve Fund. A reserve fund is money regularly set aside to pay future expenses. If this money comes from the income of the property, it is deducted from NOI. A reserve fund is commonly used to pay for major capital expenditures (e.g., boiler or roof replacement). Regular operating expenses are generally paid from monthly receipts.

The reserve fund can be kept in an interest-bearing checking or money market account. If the reserve fund earns interest, some real estate managers use that interest to accumulate funds for operating expenses that are not paid monthly. Real estate taxes and insurance premiums are often due only once or twice a year. Prorating the amounts and accumulating funds on a monthly basis means the money will be available when the payments are due, and cash flow will remain fairly constant from month to month. Any payments for operating expenses made from the reserve fund should be recorded as such.

Specific amounts deposited into the reserve fund for capital improvements can be a set percentage of effective gross income or NOI. Because deposits to the reserve account are usually for a predetermined purpose—such as replacing major equipment in five years or remodeling apartments according to an established schedule—the periodic payments into this account can be budgeted as a set amount. With commercial properties, reserves are sometimes paid by the tenants through their operating expense reimbursements and are to be used for major capital expenditures. There is an obligation to account for those funds to the tenants who may have contributed. For example, if the funds are not spent (or not entirely spent) in a predetermined period, the owner may need to return those unused funds to the tenants, depending upon the specific lease language.

Developing a reserve for capital expenditures usually requires accounting for the funds on a capital expenditure report and a ledger. The expenditure is paid as a check drawn on the reserve account. It is important to note that the accumulation of reserve funds reduces the amount of cash available to the owner from the income of the property. Because of this, an owner may be reluctant to allow the accumulation of such funds.3 There also may be different perspectives on the adequacy of reserve funds and their disposition. The availability of reserve funds is extremely important and subject to negotiation in establishing the management agreement, or as a requirement in tenant leases.

Security Deposits. Residents and commercial tenants usually pay a security deposit as a guarantee of their performance of the terms of the lease (payment of rent, preservation of the property, etc.). Many states regulate the maintenance of security deposits. Some require property owners to hold the deposits in trust or in a separate bank account that is established and maintained exclusively for security deposits. Many states and municipalities require property owners to pay interest on the amount held and may require that security deposit funds be held in an interest-bearing account. Such laws also commonly stipulate the rate of interest to be paid. The interest rate is typically low enough that earnings on the security deposit account exceed what the owner owes to the resident or commercial tenant, with a small amount of additional income provided.

In some states, residential properties incur rigid penalties when these requirements are not scrupulously observed. In other states, legislatures are slow to act and landlords have frequently been required to pay slightly higher interest to tenants. If the state does not require the segregation of these funds, landlords may use them as operating capital, and that is often ample compensation for the difference; however, commingling of security deposits with operating funds is not recommended.

For tax purposes, the interest the account earns is reported as income to the owner if it is not distributed to the tenants. To reduce (or eliminate) the owner’s tax obligation on the interest, checks to residents or commercial tenants might need to be issued annually with the tax distribution reported to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and to the tenants.

Knowledge of current tax laws, application to such funds, and implication to an owner is a fiduciary responsibility of real estate management. Even if the amount of interest owed is relatively small, the cumulative amount owed to all tenants could require the owner to pay much higher income taxes if the account is not properly maintained.

One of the main responsibilities in real estate management is collection and deposit of rents and other regular property income into a checking account maintained exclusively for the payment of property operating expenses. Any monies intended for security deposits or property replacement reserves are deposited into a separate account that is not used for operating expenses. This basic fiduciary responsibility is routine but very important because misappropriation or errors can have drastic and long-lasting effects. It is important to understand how to properly account for income and expenses for licensing, tax, and lease requirements, while staying in line with the owner’s preferences. Records of income and expenses must be accurate because these records are the basis for disbursing funds to the owner and filing income taxes. For obvious reasons, these records must also be consistent to avoid duplications and omissions, verify budget projections, and explain variances.

Based on the management agreement, a specific chart of accounts and other documents to record receipts and disbursements using the basic accounting systems and designated method of accounting for the property can be created.

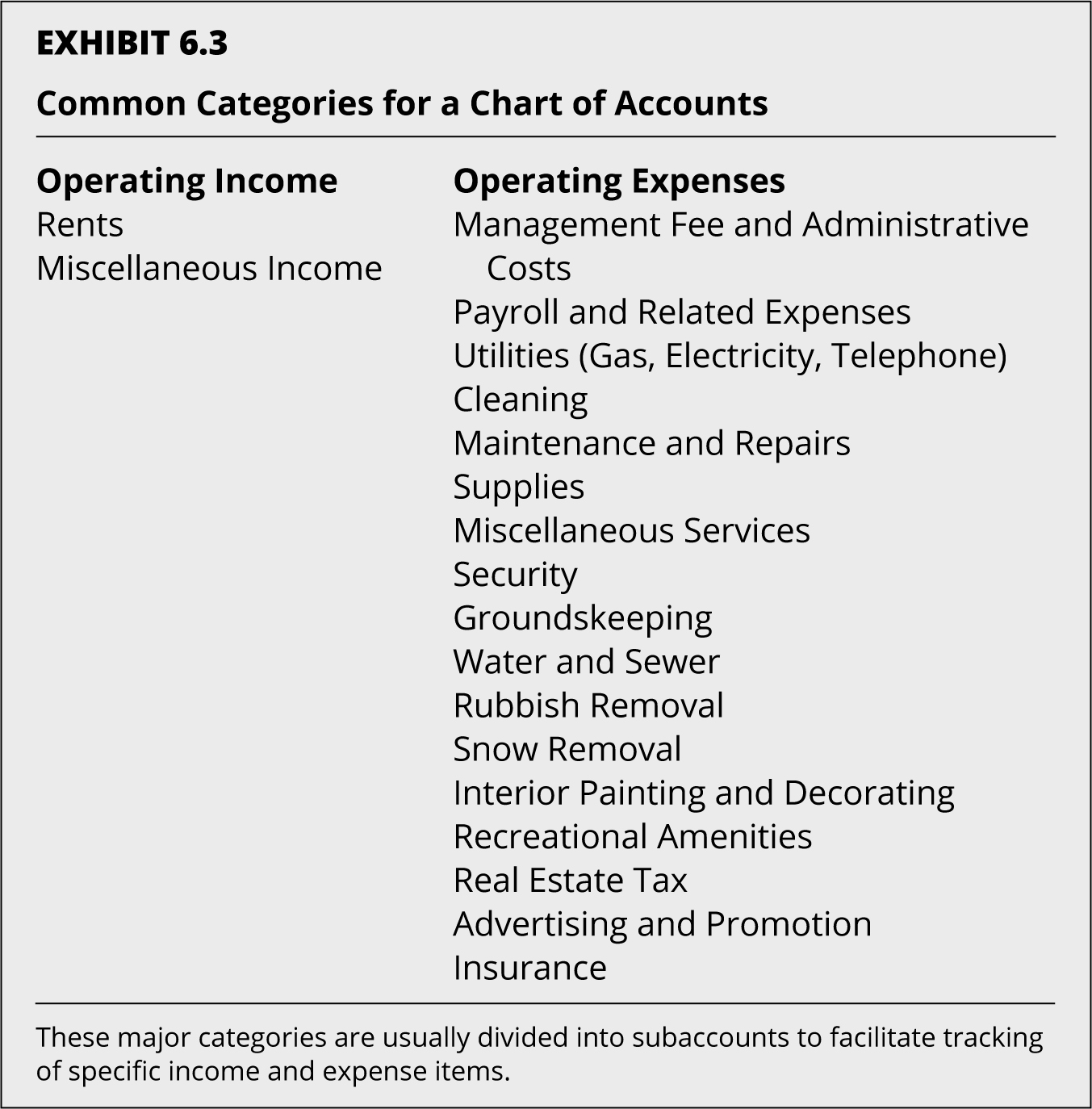

Chart of Accounts. The best way to ensure accuracy and consistency in accounting is to establish a chart of accounts (Exhibit 6.3), which usually has account numbers or codes for specific categories of income and expense. No chart of accounts is definitive—most buildings have unique features that require separate categories, entries, or subentries. Generally, the type of property and its size affect the scope of a chart of accounts.

Depending on the level of detail desired, income and expense categories can be grouped under general headings or subdivided further. A detailed chart of accounts usually provides account codes for security deposits, reserve funds, and debt service payments. The chart can identify all income and expense items for a property since specific capital expenditures may also have separate account codes. Real estate managers use this information not only for purposes of accounting, but also for reporting to the owner and others as well as for preparing accurate budgets. In fact, some real estate managers who are developing a chart of accounts for a new property seek advice from professional accountants who help ensure they identify all of the separate accounts that a specific property needs.

Accounting Methods. Regardless of the type of accounting system used, one method of accounting must be agreed upon to ensure consistent, accurate, and easily understood financial records and reports. The entire accounting and reporting system usually conforms to one of the following two methods: (1) cash-basis accounting, which records income when it is received and payments as they are made, and (2) accrual-basis accounting, which records income when it is due and expenses when they are incurred, but the records may not reflect actual receipts and disbursements. Some real estate managers use a modified cash system in which expenses that are not due monthly (insurance, taxes) are accounted on an accrual basis. When using such a mixed system, the records of NOI should be adjusted to reflect the partial accruals.

For residential properties, the only distinction between income sources may be rents, utilities (billed to residents), and miscellaneous income. For commercial properties, tenants often pay one or more amounts in addition to base rent each month. Certain charges may be categorized as additional rent if the owner passes all (or part) of the real estate taxes, property insurance, and common area maintenance (CAM) or operating expense costs to the tenants. Tenant improvements (TIs) are charged back to the tenant (sometimes with interest) may also be categorized as additional rent.

Where leases for retail space require payment of percentage rent, such income would be accounted separately from the base rent. If tenants are charged for parking, a separate income category would be warranted; this is especially true if parking space is leased to non-occupants of the building. Some items discussed earlier as sources of miscellaneous income (e.g., rents or fees from telecommunications installations or storage spaces) may be itemized separately, especially when the amounts are substantial.

Revenue

Expenses

Other Cash Transactions

Although amounts and types of expenses vary by property, the real estate management professional recognizes some common expense categories. Every real estate management company defines expenses in its own way or by the owner’s request. Some major categories might have to be subdivided to adequately account for the operating expenses of a specific property. In addition, property owners sometimes request unique expense categorizations. It’s important to understand and consistently apply the management firm’s standard categorization of expenses and then adjust them as needed to accommodate the owner’s needs and wishes.

The compensation paid to the managing agent may be a percentage of the effective gross income of the property, a flat fee, or a combination of the two. When a combination fee is used, the flat fee is usually a stated minimum, and the actual fee paid is the greater of the two amounts. The minimum fee assures compensation for management if the effective gross income is below expectations. Administrative costs cover supplies, postage, and other common expenses associated with operating an on-site office. At times, the management company may also charge some of these office expenses—if they can be segregated by property—to the owner for reimbursement. Nonstandard charges such as fees for tax preparation are usually listed as administrative costs.

Payroll and benefits may be listed as a single item, but the various deductions and distributions usually require separate accounting for wages or salaries, withholding taxes, benefits, and the various employer contributions required by state and federal governments for Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment taxes. Because of the complex accounting, it may be easier to list each of these items as a subaccount under payroll. As an alternative, payroll may be established as a subaccount in the appropriate operating expense category on the basis of the employees’ duties (e.g., administration, maintenance, and groundskeeping). In such cases, subentries would be made for salaries, benefits, and taxes. Ultimately, the specific listing for payroll (and any chart of accounts category) should be determined by the management company’s and owner’s preferences. For instance, some owners may prefer the payroll category to be separately recorded as subcategories of administrative, marketing, maintenance, or management. The most important point is to be consistent.

The payroll schedule can skew monthly reports and the monthly flow of cash through the accounts of the property. Management firms generally receive rental income 12 times a year, on the first of every month, but they rarely use a monthly payroll, and a weekly payroll is often impractical. Paying employees biweekly (26 times a year) yields 10 months with two pay periods and two with three pay periods. To avoid such variations, most real estate managers commonly use a semi-monthly payroll system or they budget actual pay periods per month.

A semi-monthly payroll system pays employees twice a month—usually on the 15th and the last day of the month. That system balances payroll distribution against rental income. Because rent is commonly collected on the first of the month, activities during the first week of the month usually center on processing incoming checks and issuing late notices for unpaid rents. The middle of the month is usually less active from an accounting standpoint, so a semi-monthly payroll system can help to ensure steady bank balances, a monthly payment to the owner that is fairly constant, and a manageable schedule of activities in the accounting department. A semi-monthly payroll may require additional computations for employees paid by the hour because the number of workdays per pay period varies, but the savings that result from preparing payroll only 24 times a year instead of 26 may offset the additional work. Some commercial properties hire outside vendors for all property services and, therefore, have no payroll expenses at all. The cost of property management services is borne by the property management firm itself.

Insurance premiums come due on varying schedules, although semi-annual and annual payments are most common. This category is usually limited to insurance relating to the property. Employee medical coverage, workers’ compensation, and employment insurance taxes (Social Security, Medicare, unemployment) are accounted as payroll expenses. The types of insurance usually included in this category follow:

Some properties may need additional insurance coverage because of special conditions; more favorable premiums may be obtained by insuring several properties under one blanket policy. The best practice is to consult with an insurance agent who specializes in the type of property in question.

While the organization of accounting departments and their extensions into the field may vary by company and property type, the accounting software will be the main source for generating both financial (external) and managerial (internal) reports. Contemporary property management software has produced a change in expectations because the software makes possible the generation of real-time reports from multiple locations. It is now assumed that new data will be input immediately, and accuracy is expected on an up-to-the-minute basis. The features of such software make it possible for real estate managers, site managers, and company executives to have instant access to all permitted information.

In the past, when administrative staff controlled the flow of data, they also controlled the generation of reports. If data entry staff fell behind in entering payments, for example, they would just delay generating a delinquency report until everything was caught up and the deposits were in the bank. Such delays are no longer considered acceptable; those who can access information, even from thousands of miles away, expect all data to be collected and entered as it is received.

An even more recent trend has property owners accessing real-time data about their properties. Web-based access to property information can be granted as needed and desired to owners, their asset managers, and virtually any stakeholder in the investment. Some real estate management firms actually use this as a differentiating factor in promoting their business. A property owner’s choice of a real estate management company may be influenced by the ability to generate instant reports or by having 24/7 access to data online.

Property owners have varying needs for financial reporting, and real estate managers must be flexible in generating financial statements to meet those needs. In daily practice, real estate managers are exposed to financial reports from four general sources:

Typically, real estate managers collect property-operating data in great detail. It is organized and categorized, and then reports are provided at the level of detail needed by the particular user. Whether historical data is intended for external financial reports or for internal managerial reporting, the collected data is the same—it is just organized differently based on the type of report being generated.

The accounting department in most real estate management firms is charged with preparing financial reports for the property owner—usually monthly or as agreed to between the owner and manager—to meet contractual requirements. The type of statements, methodology, and frequency are determined by the owner, along with whether reports are delivered directly to the owner or to the asset manager responsible for the account.

A real estate manager must be able to understand the differences in financial reporting from various sources and to modify the statements into a format that allows for analysis of the property. In general, the real estate manager plays two roles in financial reporting. He or she may:

Reports for external parties tend to give an overall financial picture, focusing on the figures themselves. They provide a historical representation of the performance of a business, describing how a property has performed in the past. Preparing financial reports for external use is part of financial accounting. Financial accounting is a system of classifying financial transactions that documents a company’s financial position in the form of a balance sheet and an income statement (external reports). These condensed external reports are sent to the various stakeholders in the property, including lending institutions, the IRS for tax purposes, and stockholders and other types of owners. They often include a narrative portion with a summary that describes how the owner’s goals and objectives for the period have been achieved. The narrative report should be supported by the following:

The most fundamental financial statements shared with external stakeholders are the balance sheet and the income statement. The periodic management report also is often accompanied by a rent roll that provides details of lease arrangements with all tenants to date as well as vacancies. However, the content of these reports should always be tailored to satisfy the owner’s requirements.

In general, reports for internal use include more detail about specific financial transactions and the manager’s assumptions about a property. Internal reports use accounting data in a format that allows the user to arrange the data for specific analyses and to forecast performance. They are based on historical or forecasted information and address past performance, current data, or future expectations. The real estate manager uses this information from the past, evaluates it in terms of current market conditions, and projects future performance.

While the information in internal reports should be complete, they do not always have to follow a strict format. Some of the reports provided to external stakeholders are also commonly used internally as part of managerial accounting. Some common reports used internally are listed below and are sorted by property type:

Rent Roll. While the rent roll is perhaps one of the most popular reports for real estate owners and managers alike, there is little agreement on exactly what it should contain. Most property management software programs have at least one rent roll report that discloses information to varying degrees. In some cases it is a report on unit occupancy; in others it schedules out accounts receivables. The rent roll almost always lists data relevant to the specific resident/tenant or unit/suite when vacant (rent, size, lease commencement and expiration, date vacated, etc.).

Vacancy Report. A vacancy report lists and describes the property’s unoccupied space, whether in square feet for commercial space or by unit in the case of multifamily or condominium units. In many cases, it will calculate the accrued loss of rent due to vacancy (economic vacancy) and the number of square feet or units vacant (physical vacancy). Vacancy reports may also include such information as the number of days a particular space has remained vacant or when the apartment will be market ready and re-leased.

Delinquency Report. While a rent roll may display balances due, it does not necessarily show the period for which rent has been unpaid. A delinquency report displays the amount due, the detail of what is unpaid, and the number of accounting periods for which a balance has remained unpaid.

Accounts Payable. Unpaid invoices are a liability of the property owner, and the amount of money owed to vendors must be properly disclosed in financial statements. The accounts payable aging statement may summarize all unpaid invoices; or it may be a detailed schedule of each invoice not paid, the period that it is past due, and why it was not paid on time. Significant delinquencies in accounts payable should be pointed out to an owner in the cover letter to the financial statements. In addition to these financial statements, the accounting department usually includes a copy of all relevant reconciled bank statements.

Accounts Receivable. The statement may be very detailed, as in the delinquency report, or it may just summarize balances due and the period over which they have remained unpaid. A real estate manager must be alert to informing the accounting department or designated individual to write off rents that are unpaid for an extended period. Some companies establish a policy that any account unpaid over a specified period—perhaps 90 days—is considered a bad debt and deducted from accrued rent revenue. In most real estate management circumstances, especially multi-family properties, eviction proceedings will be well underway for residents or tenants that have reached that level of delinquency.

Budgeting is not an exact science. The actual income and expenses of a property rarely (if ever) conform precisely to budget projections. A budget is a tool; it is the working guide throughout the budget year. Real estate managers use it to establish the priority of spending (based on the income the property produces and the expenses incurred) and to estimate cash flow. The budget helps minimize the variance of the property’s NOI and assess the property’s cash position at a given time. When an unexpected expense creates a cash shortage, the budget can guide the evaluation of alternatives for meeting the expense. Several types of budgets exist. Real estate management commonly uses three: (1) operating budgets, (2) capital budgets, and (3) long-range budgets.

The most commonly used budget is an operating budget that lists the principal (or regular) sources of income and expenses for the property, usually on a monthly basis. The gross potential rental income listed in the income and expense reports for the property should be fairly constant from month to month. Every other item of income or expense for the property is added to or subtracted from the gross potential rental income to calculate NOI. The NOI reflects any variance in individual entries. Therefore, even though gross potential rental income may be a fixed amount, the NOI and cash flow can vary substantially. A budget permits better projection and monitoring of income and expenses.

Aside from showing the sources of income and expenses for a property, a budget indicates when the transactions are expected to occur. Differing monthly amounts allocated for heat and air conditioning throughout the year reflect seasonal variations in energy consumption. Advertising expenditures for an established apartment building may be minimal for most months, so the greatest part of funds allocated for this expense are divided among the months of highest expected leasing activity. On the other hand, a new development or a property that is undergoing extensive rehabilitation may require a large advertising budget divided equally throughout the year to reflect the intensity of the leasing activity.

A separate marketing budget is usually prepared each year (an extension of the annual operating budget) as well as during lease-up of a new property or following rehabilitation of an old property.

The budget is the starting point for considering alternatives for paying unanticipated expenses. If winter weather is exceptionally cold and snowy, higher fuel consumption generally increases the fuel expense for the property. Greater demand for fuel usually leads to price increases, and that, coupled with increased consumption, can devastate a fuel budget. Energy providers may also provide alternatives. A budget plan at a fixed rate may be offered. However, at the end of the billing cycle, any overages may be billed and the budget must account for that.4

Other increases in season-related expenses, such as snow removal, can have a significant effect on cash flow.5 Snow removal companies typically offer two choices: (1) paying per occurrence or (2) contracting a monthly set rate throughout the season. However, there is a risk on the part of each party to the contract. If the contract for is set for a monthly rate and it is a dry year, the cost will be more than if a per-occurrence plan was chosen.

When such extra expenses conflict with projections made in the budget, review other projected expenses to see if another budgeted expense can be postponed temporarily—or omitted altogether for the year. Those changes will offer a way to offset part or all of the extra weather-related expenses. In accordance with the terms outlined in the management agreement, notify the owner of any action proposed or taken.

Annual Budget. The annual budget is the most common form of operating budget. There are two kinds of annual budgets: (1) historical and (2) zero-based. To prepare a historical budget, review income and expenses from previous years. A zero-based budget consists solely of projections—it ignores past operating expenses. The annual budget projects the whole year’s income and expenses for each account. If any departures from normal operations for the upcoming year are anticipated, e.g., temporarily high vacancies because of remodeling, the budget should account for them as well.

Possibly one of the most valuable aspects of this annual exercise is the presentation of the proposed new budget to the owner. It offers a natural opportunity for the owner to discuss the past performance of the property and adjust individual budget items as he or she previews the coming year. By reviewing each item in the budget, explain how anticipated income and expenses may affect the property’s performance. Gross potential rental income, vacancy and collection loss, and effective gross income categories will reflect planned increases in rents. An increase in staff size or wage adjustments will affect payroll expenses. Before the budget is implemented, the real estate manager and property owner must agree on and review each line item in detail.6

Monthly Financial Statement. The budget is often developed in greater detail by allocating an amount for each line item on a month-by-month basis, as shown in the monthly financial statement. Some items divide easily into 12 equal parts because they do not change from one month to another, while others vary substantially from month to month based on seasonal and other factors. Projecting the income when it is expected to be received and expenses when they are expected to be paid is important. If a property normally incurs an expense in March and pays it in May, budgeting for that expense in March will result in variances for both months, and the variances will require explanation. In addition, these variances cause the cash flow to change significantly.

Quarterly Budget Updates. Essentially, the annual budget serves as a point of reference. However, actual income and expenses can differ significantly from such a budget as the year progresses. To compensate for such differences, quarterly budget updates might be prepared, which reflect adjustments to the original projections made in the annual budget. These modified budgets can be more accurate than the annual budget because the projections are not so far into the future. In addition, such quarterly budgets cover the approximate time of one season, so their projections of seasonally affected income and expenses can be more accurate.

In some cases, owners of commercial properties might ask for additional forecasts for five or even 10 years in addition to the required annual budget. However, many owners do require a periodic monthly reforecasting. In general, budgets are intended to be the real estate manager’s best forecast of revenue and expense. They are not a wish list of items that the real estate manager would like to see happen. Those “what-if” scenarios are appropriate for internal analysis for strategic planning, but they are not budgets that should reflect the manager’s forecasting techniques.

Because one purpose of a reserve fund is to accumulate capital for improvements, a capital budget is prepared to show how much to set aside in the reserve fund on a regular basis. In principle, this simply requires calculating the cost of the improvement and dividing the total by the number of months before the improvement is to be implemented, then factoring in interest income that the account will earn.

However, if funds are accumulated over a period of years, consider inflation. If the interest earned on the accumulating reserve is not substantially higher than the rate of inflation, the anticipated total accumulation will not meet the actual cost of the improvement. Furthermore, the cost of materials may rise faster than the inflation rate, so a larger monthly allocation will be necessary to assure a reasonable match between the amount of reserve funds and their anticipated use. Capital budgets include leasing commissions, tenant improvements (TIs), major maintenance, and improvements or additions to the property.

Real estate managers who work for institutional owners approach a capital budget differently. These owners rarely accumulate reserve funds. Rather, their capital budgets reflect anticipated expenditures for specific capital improvement projects, TIs, and leasing commissions. Some owners may have required reserves for these that are paid monthly to the lender. The budget would then account for the expense to be paid when incurred, and reflect the reimbursement from the reserve account at some future point. Properties with heavy leasing and TIs may require an accounting of reserve account balances on a monthly basis and in the operating budget as well.

Planning for the replacement of major items should be an exercise performed as part of the budget process, regardless of whether the owner sets aside funds for that purpose. All items, from pumps and motors to roofs, have typical lifespans. Skilled engineers, maintenance technicians, and vendors can provide this information and the current costs of replacement or major repairs. Ownership and management should have a conversation early in the relationship to discuss how capital improvements and TIs will be handled. For example, the following two questions must be answered:

If needs are to be ignored or delayed, the consequences of deferred maintenance should also be a part of this discussion. It is extremely important to understand the owner’s goals and objectives. Asking the previous questions is an excellent way to discover how ownership intends management to perform in the long term.

Use of a capital budget often leads to the development of a long-range budget that illustrates the relationship between operating income and expenses over five or more years in the life of a property. The level of detail and precision is less in this type of budget than in an annual budget because projections cannot be as accurate for the longer time involved.

A long-range budget can show the owner what to expect over the time the investment will be held. It can illustrate the anticipated financial gain from a rehabilitation program, a new marketing campaign, or a change in market conditions. Long-range budgets illustrate expected income, expenses, and sources of funding. Long major projects may require the owner to make extraordinary cash contributions or financing arrangements in the early years of the holding period. Ideally, the owner will recover these extra contributions in the later years of the holding period, after the income from the property stabilizes at an amount greater than it was when the property was purchased—or when the changes were implemented.

The success of an income-producing property is measured by the amount of money it generates and the return to its investors. A property’s performance is accounted through detailed financial reports and accounting statements. This complete and multifaceted aspect of management involves establishing and maintaining thorough and accurate financial records for the property and for individual units, residents, or commercial tenants. Every dollar of income and expense must be accounted and categorized based on its source or destination as identified in a chart of accounts. The accounting records are the basis of the financial reports provided to the owner each month. Additionally, those records will help in developing budgets to predict future income and expenses. The main objectives are to maximize NOI and minimize variances between actual and budgeted income and expenses. Altogether, the various budgets are among the most useful documents developed for clients or the owners.

A budget is a living, breathing document that should be adjusted accordingly to ensure a property’s success. Like with any roadmap, there are obstacles that will be encountered. Remember to communicate effectively and communicate often. This way, even if the property is not positioned for success at year end, all parties will understand why and be in a position to better plan for success in the forthcoming year.

1. The IREM annual Income and Expense Reports are good resources for comparing expenses to other properties.

2. The cap rate is also considered an indication of the risk involved in an investment. The higher the cap rate, the riskier the investment.

3. It should be noted that money put away for reserves still represents profit and is taxable to the investor.

4. Energy companies will make allowances for agreements that are to their advantage. For example, they may offer a lower rate to buildings that are willing to switch from gas to oil reserve tanks if demand is too high, or in hotter climates with air-conditioned buildings, they might consider charging lower rates if residents or tenants are willing to endure short “shut-offs” during peak usage.

5. For example, online statistics are provided by regional meteorologists that state the average number of snowfalls with accumulations of two inches or more that will require plowing, but the forecast for the upcoming season is for unusually heavy snow.

6. The annual budget preparation is also the perfect time to discuss major renovation projects or needed repairs with the property owner(s) because these items affect the overall cash flow.