Chapter Two Using Conceptual Frameworks in Research

Chapter Overview and Goals

In this chapter, we emphasize the importance of conceptual frameworks in research and discuss the important role they play in all aspects and phases of qualitative research. This chapter begins with a discussion of what constitutes a conceptual framework. After establishing a working sense of what a conceptual framework is and a beginning roadmap of its uses, we focus on what it does—or, more precisely, what you do with it. Following this, we discuss how to construct a conceptual framework and provide recommended practices and examples of how researchers describe their own conceptual frameworks.

By the end of this chapter you will better understand

- What a conceptual framework is

- The roles and uses of a conceptual framework

- How a conceptual framework guides and grounds empirical research

- How you, as a researcher, can use a conceptual framework to build and refine your study

- How to construct your own conceptual framework

- The relationship between a conceptual and theoretical framework

- The difference between a literature review and a theoretical framework

- Each of the component parts of a conceptual framework and how they fit together

- The dynamic nature of conceptual frameworks

- The multiple possibilities for developing and representing conceptual frameworks in narrative and graphical form

Defining and Understanding Conceptual Frameworks and Their Role in Research

It is vital to understand what a conceptual framework is, what its components are and how they interact, and how it is used to guide and nourish sound qualitative research.

What Is a Conceptual Framework?

Conceptual frameworks have historically been a somewhat confusing aspect of qualitative research design because there is relatively little written on them, and various terms, including conceptual framework, theoretical framework, theory, idea context, logic model, and concept maps, are used somewhat interchangeably and often in unclear ways in the methods literature. Reason and Rigor by Ravitch and Riggan (2012) emerged as a response to this conceptual and definitional murkiness; it focuses on articulating what comprises a conceptual framework and how conceptual frameworks guide research from its inception to its completion. Because that book goes into great detail about how a conceptual framework is used in actual studies (with multiple empirical studies used to exemplify its role at various stages of the research process), it is the best current source for seeing how the conceptual framework guides every facet of research. In this chapter, we build on that text and the work it builds on (discussed below) and seek to conceptualize the term and highlight the roles and uses of the conceptual framework, as well as the process of developing one, since we believe a conceptual framework is a generative source of thinking, planning, conscious action, and reflection throughout the research process.

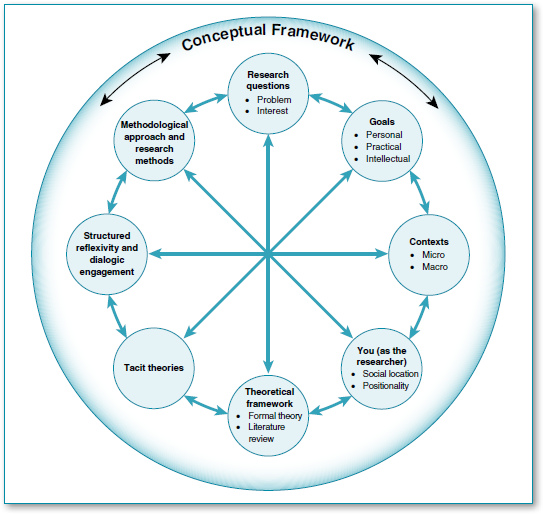

A conceptual framework makes the case for why a study is significant and relevant and for how the study design (including data collection and analysis methods) appropriately and rigorously answers the research questions. In addition, a conceptual framework situates a study within multiple contexts, including how you, as the researcher, are located in relationship to the research (Ravitch & Riggan, 2012). The conceptual framework consists of multiple parts and serves a variety of intersecting, ongoing, and iterative functions for researchers embarking on and engaging in research and the scholarship it produces. As Figure 2.1 illustrates, a conceptual framework includes multiple components that intersect, inform, and influence each other. For example, the methods that you use to answer your research questions are informed by (in conscious and unconscious ways) by your tacit theories, theoretical framework, the personal and professional goals of your study, ways that you systematically reflect on multiple aspects of your research (structured reflexivity), the intentional interactions you have with others (dialogic engagement),1 the macro and micro contexts of your research setting, and you (as the researcher), including your social location and positionality (which reflects the macro contexts of the research as well). We describe these components and how they come together throughout this chapter and overview them here to help you begin to visualize and understand what comprises a conceptual framework.

Terms and Concepts Often Used in Qualitative Research

Tacit theories: Tacit theories refer to the informal and even unconscious ways that you understand or make sense of the world that are not explicit, spoken, or possibly even known to you without intentional reflection. These might include working hypotheses, assumptions, or conceptualizations you have about why things occur and how they operate. Unlike formal theories, tacit theories are not directly situated in academic literatures. Rather, they are an outgrowth of the attitudes, perspectives, ideologies, and values into which you have been socialized, often without knowing it. Everyone operates from tacit theories about people and the world, and without attention and reflection, they can constrain your research in a variety of ways. One example of this could be if you have a tacit theory that respecting authority is always good and therefore that all challenges to authority reflect badly on people. This theory might lead you to deem anyone who confronts authority as problematic versus seeing that context mediates whether an authority figure should be respected and what that means and looks like. We discuss how tacit theories relate to your conceptual framework throughout this chapter.

The Components of a Conceptual Framework2

As noted above, the roles of a conceptual framework include arguing for the significance of a topic, grounding the topic in its multiple contexts (theoretical and actual), guiding the development and iteration of research questions, the selection of theories and methods within a methodological framework that makes sense for the topic and allows for rigor, and providing you, as the researcher, with a framework and set of contexts in which you can examine your social location/identity and positionality as it relates to and shapes methodology overall and methods choices specifically. The conceptual framework creates a bridge between the context, theory, both formal and tacit, and the way that the study is structured and conducted in relation to all of these contextualizing and mediating influences. When conceptualized holistically, a conceptual framework serves as the “connective tissue” of a research study in that it helps you to integrate and mobilize your understanding of the various influences on and aspects of a specific research study in ways that create a more intentional and systematic process of explicitly connecting the various parts of the study. It is important to point out that the conceptual framework should be defined not just by its constituent parts, or even by its collective, but by what it does, that is, how these parts, or processes, are intentionally placed in relationship to each other by the researcher and work together in an integrated way to guide research.

What Does a Conceptual Framework Help You Do?

A conceptual framework can serve as a means of explaining why your topic is important practically and theoretically as well as detailing how your methods will answer your research questions. It serves as a thought integration mechanism for learning from existing expertise as you cultivate (and ultimately generate) knowledge within and possibly across thought communities already in motion (Ravitch & Riggan, 2012). In addition, Ravitch and Riggan (2012) highlight the ways that a conceptual framework supports how you locate (and perhaps argue for) your research in terms of its newness and contribution to a field or set of fields of inquiry—perhaps new contexts, questions, frames (some or all of these)—which create new terrain for you to traverse. If we stay with this metaphor, the conceptual framework is the compass, the landmarks, the navigation system, and the zoom function of your vision apparatus. You are the one to decide how these realities and tools come together in the expedition into a new topic, setting, set of theories, and so on.

The conceptual framework helps you cultivate research questions and then match the methodological aspects of the study with these questions. In this sense, the conceptual framework helps align the analytic tools and methods of a study with the focal topics and core constructs as they are embedded within the research questions. This alignment of methods and analytical tools helps to increase a study’s rigor and validity (Ravitch & Riggan, 2012). The conceptual framework helps you situate the study in its theoretical, conceptual, and practical contexts; includes implications related to the study’s setting and participants; situates your researcher social location/identity and positionality; and articulates how all of these aspects are related to methodological frames and processes.

A conceptual framework is the focal framework for, and process of, designing and engaging in research (Ravitch & Riggan, 2012). It details the primary or core constructs of a study and the relationships between them (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2014). In addition, conceptual frameworks evolve and change as your understandings change: “Conceptual frameworks are simply the current version of the researcher’s map of the territory being investigated. As the explorer’s knowledge of the terrain improves, the map becomes correspondingly more differentiated and integrated” (Miles et al., 2014, p. 20). A conceptual framework becomes increasingly sophisticated as you become more deeply involved and your understanding of these constituent parts and the whole come together and build on and into each other. Ideally, a conceptual framework helps you to become more discerning and selective in terms of methods, grounding theories, and approaches to your research (Miles et al., 2014).

Collaboration is a key horizontal in qualitative research, and we strongly critique the enduring academic notion of the lone researcher. One issue we have with this notion of the lone researcher is that we believe that research is ideally not a solitary endeavor since genuine research reflexivity warrants multiple levels of research collaboration and engagement (L. Anderson, 2008; Denzin, 1994; Guba & Lincoln, 2005; Steedman, 1991). We believe this to be true for individual research projects as well as research team-based projects. For an individual, collaboration is vital to create the conditions necessary to challenge your assumptions and blindspots and integrate a range of perspectives into all facets of your research, and the conceptual framework is a way to seek out a range of feedback and perspectives. When working on a research team, you need ways to engender group dialogue and exchange to examine diverse perspectives. Thus, the conceptual framework can become a mechanism/strategy for aligning researchers’ goals, expectations, values, and ideas about research at its outset and throughout the process (Miles et al., 2014). We have used collaborative conceptual framework development—through collective mapping and articulation processes that are grounded in the sharing of each research team member’s construction of a conceptual framework memo (see Recommended Practice 2.1)—in our own research teams in ways that have contributed significantly to the design and implementation of our research. In this sense, the use of conceptual frameworks to guide a team of researchers into critical conversations about perspectives on each aspect of research design and development becomes an important consideration.

A conceptual framework can function as “a tentative theory” of what you are studying (Maxwell, 2013, p. 39). It is a system—defined as a functionally integrated set of elements—in the sense that it serves as an integrating mechanism that works within and across the “concepts, assumptions, expectations, beliefs and theories” that guide research (Maxwell, 2013, p. 39).

It is important to view the conceptual framework as a process rather than a product; that is, the building of your conceptual framework is a dynamic, sense-making process that happens in nonlinear stages and that takes multiple forms. The conceptual framework generates the focus of the research as it is informed and shaped by it (Ravitch & Riggan, 2012).

Multiple, intersecting components of a conceptual framework help a researcher/research team to conceptualize and articulate specific constructs and aspects central to a study as well as to examine their intersections and overlaps within the multiple contexts that shape the research. A conceptual framework includes the guiding theories or assumptions of the researcher(s), the goals and expectations of a study, and the formal and informal theories that contribute to understanding and contextualizing the focal topics of a study; furthermore, the conceptual framework allows the researcher(s) to make meaning and use of the overlaps and disjunctures within and between core constructs of your study in ways that produce deeper, more integrative understanding of the topic and contexts central to the study. A conceptual framework enables you to make an argument for the value and significance of your research in ways that reflect the intentionality of the process of uncovering the ways in which studies emerge from and contribute to the corpus of research in your substantive area (Maxwell, 2013; Miles et al., 2014; Ravitch & Riggan, 2012). In addition, a conceptual framework helps you to locate yourself in the research process, as well as to attend to various epistemological and ontological considerations and beliefs and how these shape us as researchers and therefore shape our methodological choices. Finally, a conceptual framework is constructed and continually iterates throughout your research, and it helps to refine the research simultaneously. This notion of active building and refining is central to understanding that a conceptual framework is both guiding to a study and also derived from a study.

Terms and Concepts Often Used in Qualitative Research

Thought communities: Thought communities refer to the different realms or “communities” to which your research may speak or relate. These may be actual communities in a social geography sense of the term (i.e., a school community, a geographically based community), and/or they may be groups of people such as affinity groups or cultural communities. For example, if you are studying a particular aspect of teacher education, different thought communities your research may speak to or influence could include scholars of teacher education, teacher educators, and/or teachers and other educational practitioners.

Core constructs: Core constructs (sometimes called core analytic constructs) refer to the central aspects—concepts, phenomena, and topics—that guide and are at the center of a research study. These are typically articulated in your research questions; they are the key concepts, phenomena, and topic areas you seek to study and understand more fully through the research. These need to be carefully considered at the outset of and throughout research question development and research design processes since they generate the areas of theory and conceptualization that drive your research study.

The Roles and Uses of a Conceptual Framework

There are myriad, intersecting roles and uses of a conceptual framework, which include the following:

- Providing the overall structure in which you can articulate and examine the goals of your study and its intended audiences

- Serving as a compass for identifying the relevance and selection of, and then engaging with and integrating across, existing research literatures and theories

- Providing the idea context for you to argue for the rationale and significance of your study for/to its intended areas, fields, and/or disciplines

- Helping you to thoughtfully develop, refine, and delimit your research questions

- Providing a dynamic system for identifying and refining your understanding of your researcher positionality and engaging in a reflexive approach to your study

- Providing a methodological ecosystem for developing and continuously refining the study’s methodology and research design

- Helping you to develop an appropriate framework for the collection of data and the development of instruments

- Serving as a guide and frame for the selection of data analysis frameworks and processes

- Acting as a foundation for writing and critically scrutinizing your analysis and study findings

- Helping you to see how formal theory (your theoretical framework) intersects with various aspects of your study, including research questions, methods, and goals, as well as the informal theories and working assumptions you may have about the topic

- Serving as a mechanism to consider and reflect on the significance and value of your research once it is completed, as well as to consider the next questions to be asked in the field(s) that the study speaks back into

Rather than view these aspects of the research process as linear or discrete, a conceptual framework helps the researcher recognize and assert how the aspects of research content and process influence, as they are influenced by, the guiding conceptual linkages in a given study. One way to think across these various roles and functions of a conceptual framework is to consider the notion of situating a study in its multiple, intersecting, ever-iterating contexts and concepts. This is what we mean by a methodological ecosystem, described further in the following section.

Constructing and Developing a Conceptual Framework

After gaining a better understanding of the value, roles, and uses of a conceptual framework, it is important to consider how to construct and continuously develop one for/in your research. There are many ways that researchers embark on the early development of research topics, goals, and questions. The conceptual framework is a way of approaching research design/construction that focuses on what we think of as the ecology or ecosystem of a topic and the fields from which and to which they build. By ecosystem, we refer to the notion that a research study is a complex system with multiple parts that are both separate from each other and connected by and within a larger system; each tree and rock is related to each insect and blade of grass in ways that are both clear and also in need of ongoing conceptualization and explication. The concept of an ecosystem helps to reveal the interconnectedness and even interdependence of the various component parts of research studies. The conceptual framework provides the sense of interconnection and interdependence among parts of a research project. The conceptual framework is central to the construction and implementation of research. A conceptual framework embodies methodological criticality because it requires a systematic intentionality around examining and accounting for the connections between theory and research and how these are generated within and across stages of empirical work in relation to you and your goals, assumptions, social location/identity, and positionality.

The guiding sources for constructing a conceptual framework include (a) the researcher, (b) tacit theory or working conceptualizations, (c) the goals of a study, (d) study setting and context, (e) broader macro-sociopolitical contexts, and (f) formal or established theory. In the sections that follow, we discuss each of these guiding sources. These sources are not listed in priority order and are not linear. We emphasize this caveat because complexity can sometimes be reduced when complex concepts are broken into parts. We do not want to be misinterpreted as oversimplifying something as iterative, recursive, and altogether messy (in the creative albeit sometimes stressful for new researchers sense of that term) as a conceptual framework.

The Role of the Researcher in Conceptual Frameworks

The major source for constructing a conceptual framework is you, the researcher. As stated in Chapter One, you are the primary source of both constructing and understanding the goals and meaning of your research project. This includes your positionality, social location/identity, experiences, beliefs, prior knowledge, assumptions, ideologies, working epistemologies, biases, and your overall perspective on the world. A complex combination of all of these aspects about you as the researcher, including your identity and beliefs, shapes the goals of your study in terms of how you think about your research at the conceptual and methodological levels. Relating to the notion of the researcher as instrument (Lofland, Snow, Anderson, & Lofland, 2006; Porter, 2010), the conceptual framework helps you conceptualize, identify, engage with, and critically examine the layers of your beliefs, biases, and assumptions. Engaging in a process of identifying and reckoning with these aspects of your thoughts and feelings as a researcher, with a focus on your social identity and positionality and how these influence your belief systems, ideologies, hopes, goals, and interests, helps you to more fully and critically understand how these aspects of who you are shape what you choose to study and how you visualize, consider, and plan to study it (Alvesson & Sköldberg, 2009; Henslin, 2013; Neyrey, 1991; Tetreault, 2012; Tisdell, 2008).

Conceptualizing the researcher as a primary instrument of the research has significant implications throughout every stage of the research process in that the subjectivity, social location/identity, positionality, and meaning making of the researcher profoundly shape research processes and methods and therefore data and findings (Lofland et al., 2006; Porter, 2010). Because of the prominence of the researcher in the conceptualization, design, and conduct of qualitative research, the positionality of the researcher is viewed as a central and vital part of the inquiry itself. Therefore, as the researcher, you must engage in a reflexive process that helps to uncover the layers of influence on your thinking and how this shapes your study from what you choose to focus on, how you frame it theoretically, how you collect data and approach/engage with participants, and then how you interpret and analyze the data of your study and write about the findings.

Given the primary role of the researcher, you must commit to a critically reflexive process that helps you to examine the influences on your thinking about the world, the specific context(s) of your research, and what is possible in your research. This entails a commitment to identifying and engaging with each of these aspects of the research and your roles in the research (Alvesson & Sköldberg, 2009; Henslin, 2013; Neyrey, 1991; Tetreault, 2012; Tisdell, 2008). We argue that a conceptual framework provides a structure for inquiring into yourself as a major shaper of and ongoing influence on the research in all of its stages and facets. Furthermore, the conceptual framework is the engine that drives your understanding of the ways that these aspects of self and research come together to form and continuously shape research studies.

A conceptual framework helps to first identify and then clarify what you know, care about, and value as central aspects of a study and then to connect these with the various other aspects of and influences on your research (Ravitch & Riggan, 2012). Situating yourself as a researcher entails considering how your study is situated (and how and why you situate it as you do) within fields/disciplines and within your thinking of what these fields might need in terms of what many think of as “the next set of questions to be asked.” By next set of questions, we mean how what is already known and written about in a field maps onto your desire to study a new dimension or aspect of that research in similar or new contexts to advance the discourse in that field. Furthermore, situating yourself and your research involves understanding how your ideologies, positionalities, and sets of relationships in the world influence your thinking broadly and specifically (Ravitch & Riggan, 2012). In terms of your working theories, it is useful to make a distinction between the formal theory aspects of your working theories and conceptualizations and those that are more organic to your thinking. These tacit theories, which are also called implicit theories, guiding assumptions, working conceptualizations, or “theories in use” (Argyris & Schön, 1978), inform the formal theories that researchers invoke and use.

The Role of Tacit Theories in a Conceptual Framework

The role of the researcher influences all aspects of a study, and another important consideration includes the ways that researchers view and make sense of the world, or what we refer to as the researcher’s tacit theories or working conceptualizations. While we will discuss what we refer to as formal theory later in this chapter, and while your working theories and conceptualizations are certainly a part of your overall identity and social location, we want to focus on the realm of tacit theory as a way to delve into this aspect of how you, as a researcher, enter your research with your own theories of how things work. Your guiding or informal theories are important to consider before, during, and after you design and engage in your research because they form your thoughts about the research at all levels and within all approaches in both direct and indirect as well as conscious and unconscious ways that must be explicated and reckoned with—first for yourself and then for your audiences. Some of this is within the personal realm—what you believe, how it relates to your socialization into certain biases and assumptions, what perspectives you hold dear as a person, practitioner, scholar, and so on. Some of it is professional, as in the “wisdom of practice” (Shulman, 1987a, 1987b, 2004) that you have cultivated over time and that guides professional choices, decisions, and concerns. Often, these tacit theories are at the crossroads of the personal and professional aspects of who you are and what you do every day because these aspects of positionality intersect.

By tacit theories, we mean informal and even unconscious ways that we all think about, make sense of, and explain the world and the various contexts and people within it. These are the often unspoken aspects of how we view the world that can be thought of as part of our guiding epistemological and ontological beliefs. Argyris and Schön (1978) discuss the related concepts of “espoused theory” and “theory in use” to describe the difference between theories that are espoused, or consciously claimed and articulated, and the theories that are actually used and worked from within organizations, which are often implicit. We think this is a useful framework for individuals as well in the sense that each of us is guided by our beliefs and assumptions about the world, and we pull on/act from these in the decisions and actions of our everyday lives in ways that may run counter to what we purport and espouse to be our belief systems. In a process that allows us to consider the possible chasms and even collisions between the espoused and the actual theories we hold, what we at first glance and without deep reflection might say are our theories and beliefs, upon reflection, often get challenged and reshaped or developed based on a more careful and systematic charting and consideration of these views.

Based on this concept—that reflection engenders changes in your thoughts brought about by increased awareness—we think that you as a researcher should spend considerable time asking sets of questions about what tacit or implicit theories guide your interest in the topic, frame how you are thinking about the topic in a specific setting or context, and what formal theories you are drawn to and that you draw upon to help you make sense of what you are thinking and considering. Attending to these issues early on and ongoingly is enormously important to the integrity and validity of your research.

How Study Goals Influence and Inform a Conceptual Framework

In addition to making your tacit and working understandings more explicit, discerning how you think about the goals of a study is an important aspect of qualitative research. Most studies begin broadly with an interest or a concern of a researcher or group of researchers. What becomes important, once you decide to turn an interest or concern into an actual research study, is to map out and theoretically frame the key goals of the study.

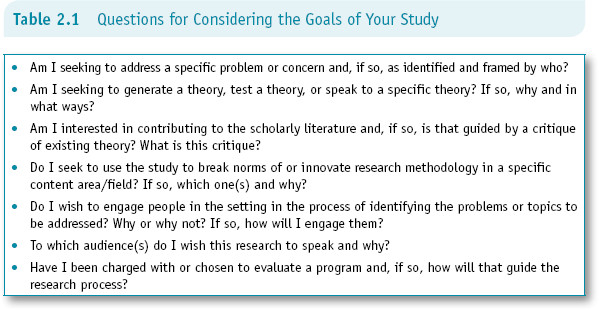

To engage in an intentional and systematic process of developing a solid understanding of the goals and rationales for your study, we suggest a reflective inquiry process in which you ask increasingly sophisticated questions that relate directly to the goals of the research overall and at each stage of the research process. The goals of a study can stem from personal and/or professional goals, prior research, existing theory, or some combination of these influences on a researcher’s thoughts, values, and interests. We recommend to our students that they think about goals in both broad and specific ways. Broadly, our students find it useful to conceptualize this in terms of their personal, practical, and intellectual goals (Maxwell, 2013). What your goals are for a study can depend on how you are coming to the research. For example, are your research questions coming out of previous research that you have conducted and want to build on? Are they emerging from questions or problems of practice that you wish to investigate to improve upon your and/or others’ practice? Are they coming out of deep engagement with formal theory that you wish to engage with or push into using empirical data? The goals of your research come from multiple influences, prior and current. And so, the conceptual framework can be a mechanism for a specific process of conceptualizing and then organizing your thinking around the set of goals you have for the study and for your line of inquiry more broadly.

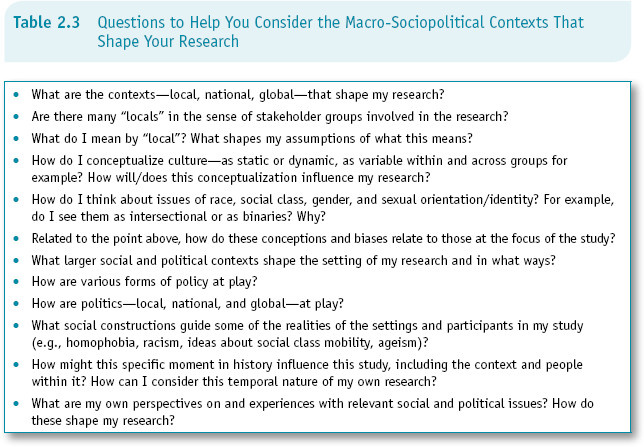

There are many ways to consider research goals. We suggest having a set of conversations with peer researchers and research advisers in addition to reflexive writing exercises. Specific questions to examine in writing and in conversation with “critical friends” are described in Table 2.1.

These questions may seem simple, but understanding the broad and specific goals of a study is often tricky and confusing. Even with the challenges of unearthing and engaging with these goals as you come to understand them early on and over time, it is very important to clarify and examine them carefully at the outset of a research project and continuously throughout the process.

Conceptual Frameworks and the Role of Setting and Context

Another major piece of a conceptual framework includes the study setting and context, which means the actual research setting (i.e., a specific place, organization, group, community, or communities) and what we think of as the context within the setting, which means who and what aspects of that setting are central to your research. For example, while your research may be situated in the School District of Philadelphia, for example, if you are studying how students learn reading in first grade, you are going to look at a different set of core constructs and approach them using different data sources than if you are looking at issues of communication and equity between administrators and teachers.

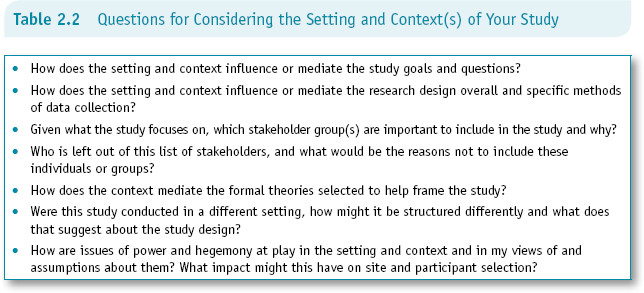

The consideration of the overall context, combined with what we think of as the context within the context, is important because it speaks to the fact that the domain of inquiry as well as the set of stakeholders within the setting comprise an important set of factors that influence what you study and how you frame the study. Spending time considering this in some depth will help you to determine which theories and concepts you will need to consider and assemble to investigate the phenomena and stakeholders in focus in ways that help you understand the relevance of the site and setting to the overall topic, goals, and research design. The setting of a study has much to do with key concepts and constructs you will use formal theory to examine, and the conceptual framework can help you to examine these in ways that generate connections between theory building and conceptual contextualization. In Table 2.2, we suggest questions that might help you to consider these aspects and their impact on your research.

Questions like these can help you to examine the decisions you make in choosing the study setting and the participants within that setting as well as to consider the goals of the study and how these match (or do not match) the setting. Thinking about this early on can help to clarify the rationale of the study as well as help to direct the overall design and approach to specific data collection methods.

Broader Macro-Sociopolitical Contexts and Conceptual Frameworks

In addition to the specific setting and contexts that shape your study, examining the broader macro-sociopolitical contexts that influence your research is of vital importance. Understanding the research setting and context and how they relate to the focus or domain of your inquiry and how the setting and focus are shaped by macro-sociopolitics is a significant aspect of engaging in critical and intentional research. What we mean by macro-sociopolitics is a combination of the broad contexts—social, historical, national, international, and global—that create the conditions that shape society and social interactions, influence the research topic, and affect the structure and conditions of the settings and the lives of the people at the center of your research (including you). Engaging in an active consideration of these forces—and the issues of equity and hegemony that they reflect—is at the core of taking an approach to research that embraces criticality since the role of broad social forces is considered central to critical research. We further discuss this in Chapter Three (and beyond).

The need to consider and include macro-sociopolitics as an aspect of your conceptual framework is important to stress, and we believe that it has (at least) two main implications. The first is the importance of examining and critically understanding the sociopolitical nature of the topic and setting of the study in ways that reflect the social, political, and structural conditions of the context of the study, which can be variably experienced by stakeholders depending on such things as role, level, and title within communities and organizations and how these relate to hierarchy. The second is that you should consider the historical moment in which your research belongs and examine how it shapes the context and setting as well as your view of and approach to the inquiry. As a researcher, you should understand the temporality that exists in a set of macro concerns and contexts that shape and mediate the setting and the research of a group or population in that setting. This is contextual as well as temporal in the sense that while there are some constants (e.g., structural oppression, hegemony), these are also shaped by the current milieu of governance, policy, economics, and guiding social constructions in society at particular moments in time (meaning that things shift over time and take on new and different meanings—race would be one good example of a concept that has changed meaning over time).3

The process of continued contextualization comprises what we think of as a process of “rugged contextualization,” which refers to the rigorous pursuit of understanding context at these various levels as well as systematically appreciating how they inform and influence each other. A solid conceptual framework helps you to articulate and examine specific phenomena and their contexts critically and to explore and refine your sense of context at multiple levels. This means, in part, that you must learn how to complicate the concept of context even as you seek to make it explicit and understandable to those who read and engage with your work.

A major role of a conceptual framework is to contextualize research as a site of generative meaning making around the role of context, critically and intersectionally, which includes helping the researcher to examine and understand (a) the social, cultural, political, economic, and ideological milieu of the research; (b) macro-sociopolitics and their manifestation in your specific research setting, including in interactions with participants; (c) your social location/identity and positionality and its impact on design, fieldwork, and analysis; and (d) the influences of sociocultural/historical contexts of the individual(s), community, group, and/or organization in focus on the research process/product. The ability to critically consider these aspects of the research requires a commitment to intentionally identifying and then carefully examining the multiple spheres of influence on your research setting and context as well as how these affect all facets of the research. Table 2.3 details some questions to help you identify and explore these issues. We recommend addressing and considering these issues by individually reflecting and using dialogic engagement strategies.

These are but a sampling of the questions you should ask to critically conceptualize the macro influences on the setting, context, participants, yourself, and the study. This layer of context examination is absolutely vital to designing, conducting, and achieving criticality in research.

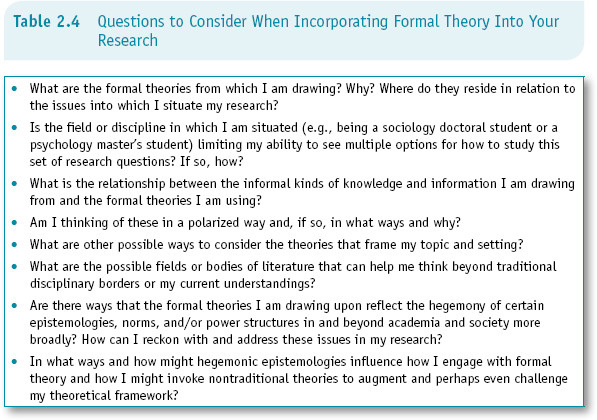

The Role of Formal Theory in Conceptual Frameworks

An additional component of a conceptual framework includes formal or established theory, which we refer to as the theoretical framework. The conceptual framework is a “dynamic meeting place of theory and method” (Ravitch & Riggan, 2012, p. 141), and you must consider the roles that existing, or formal, theory play in the development of your research questions and the goals of your studies as well as throughout the entire process of designing and engaging in your research (Ravitch & Riggan, 2012). Formal theory—the set of established theories that are combined in relation to your ways of framing the core constructs embodied in your research questions—constitutes the theoretical framework of your study. The process we describe connotes that there must be a critical integration of theories that together construct a framework for theorizing the study. The theory integration process is guided by the ways that you, as the researcher, engage with and use specific theories and models to consider the setting, events, contexts, and phenomena you are seeing and exploring. In other words, the theoretical framework is the set of formal theories that you seek out and bring together to frame and contextualize the domain or focus of inquiry and the setting and context that shape its exploration. Formal means that these are codified through publication of a variety of sorts; it also means that such theories are recognized as accepted by (even if critiqued within) the field as a whole. An important caveat to this is that hegemony mediates, in important and often invisible or insidious ways, what formal theory gets codified and how. Hence, a critical eye toward what Sharon refers to as “epistemological domination” is vital to research that does justice to the people and contexts that are at its heart.

The theoretical framework is how you weave together or integrate existing bodies of literature—for example, adult learning theory or racial identity development models—to frame the topic, goals, design, and findings of your specific study. We distinguish a theoretical framework as different from and more focused than a literature review, which is often thought of and described as a product when it is more accurately conceptualized as the artifact of an active meaning-making and integration process. The literature review is the broader process by which you construct a specific theoretical framework, and this process is not a single moment that produces an artifact, but rather, the review of literature happens throughout the process of conducting research; it is both a guide and a by-product of research. The process of creating a theoretical framework requires that you engage at a meta-analytic level in deciding which of the theories and bodies of literature that you have reviewed are vital to the theoretical framing of your study (this often requires consultation with peers and advisers). The theoretical framework can be thought of as the way that you work out the theoretical constructions and concepts that are central to your understanding of the focal topic, the core constructs of your study, and the thought communities that are engaged in your areas of inquiry.

The theoretical framework, as we discuss in greater depth as a part of critical research design in Chapter Three, is a primary piece of the conceptual framework, and as such, it intersects with the other aspects of research development and design in ways that should be generative and active throughout the research process. Conceptual frameworks are developed and not found “ready-made” (Maxwell, 2013, p. 41). Part of this involves not considering theory immutable; it should be viewed as a point of context and reference to be engaged with (Maxwell, 2013; Ravitch & Riggan, 2012). You seek out formal theories to help understand what you are studying and why you are studying it. Furthermore, throughout the research process, you cultivate a working expertise that leads you, ideally, to speak back to theory and into theoretical debates, even challenging existing theory by exploring it within your research context. This is a very important point to consider because it sets up any research project not just as derived from or informed by formal theory but potentially as a way to explore, refine, or even refute existing theory. As well, it highlights the dynamic and fluid nature of this framework-building process. It also speaks to the importance of the researcher not assuming formal theory to be an immutable “Truth” but rather to be something that is critically considered and engaged with in ways that help frame your understandings and then to which you might speak back to with your own research findings in a variety of ways.

Researchers should ask a set of questions to understand the informal or tacit theories that we enter into our research with and their relationship with the formal theories we choose as a part of our theoretical frameworks. Table 2.4 includes some of these questions.

The conceptual framework, which includes your theoretical framework, is the place where you can (and we argue should) explore these kinds of questions as they shape and relate to your research. It is valuable and important to think of the intersections of informal and formal theories in ways that bring both into focus and help you understand how one leads you to the other and back again. In Chapter Three, we focus on the development of your theoretical framework as a foundational stage of research question development and the research design process.

Building Your Own Conceptual Framework

Ravitch and Riggan (2012) discuss multiple strategies and practices for constructing and developing conceptual frameworks. We similarly argue that sets of reflective writings that ask a series of questions about your research are central to a conceptual framework’s critical iteration. We specifically call these structured reflexivity and dialogic engagement practices. These practices, which include reflective writings and structured conversations with individuals and strategically selected groups, create opportunities for you to develop and engage with all aspects of a research process, including how you theoretically understand a topic, the methods you use, the ways you analyze data, and the variety of additional issues and concerns that help you to engage with and continually refine a conceptual framework.

Reflective practices are the key to ongoing conceptual engagement and accountability to yourself and the research. Because developing a conceptual framework is an evolving and iterative process, you should engage in these reflective practices throughout the duration of a study. The recommended practices and examples we provide are just a few ways for you to reflexively engage with your research. We present numerous additional practices and examples throughout the book to help facilitate these processes. In this chapter, we focus on the Conceptual Framework Memo (Recommended Practice 2.1) and Concept Map (Recommended Practice 2.2) as specific early practices for developing your conceptual framework. After specifically describing the practices, we include an annotated conceptual framework memo (Example 2.1) and two additional conceptual framework memos (Appendixes A and B). It is our goal that these examples help you as you construct your conceptual framework and that they do not limit or constrain the myriad possibilities for ways that you can develop, represent, and describe a conceptual framework. It is also worth reemphasizing that conceptual frameworks evolve. The examples of conceptual framework memos we present represent a snapshot of each author’s thinking and processes, as conceptual frameworks are intended to iterate over time. Finally, we include an example of a conceptual framework excerpted from a dissertation (Appendix C) to help you to see the different iterations and forms a conceptual framework can take.

In Example 2.1, Jaime Nolan does a particularly powerful job of locating herself in terms of her social location/identity and positionality in relation to the research site and participants, thoughtfully explicating the historical and current contexts at play in her research, and showing the intersection between the ideologies and theories at the heart of her study and the study methodology. She also includes a narrative about her research questions in a way that invites the reader to understand her sense-making process and discusses how the research questions are still emerging in an iterative fashion as she reads more and further develops the study focus and methodology. We also appreciate the richness of her narrative and its relationship to her graphic. Jaime has created a process-oriented memo that documents her emerging conceptual framework and locates herself and the students in context. Furthermore, she problematizes the research and the inequities it seeks to explore and work against, and she looks at the formal theory and its relationship to her own wisdom of practice and emerging conceptualizations of the research. In addition, Jaime lays out her methodological approach and begins to drill down to her research design. She does this taking a holistic, ecological approach that honors the meaning-making processes at the heart of her research.

Across this example conceptual framework memo and the examples in the appendix (Appendixes A, B, and C), we see how different researchers structure, develop, and iterate their conceptual frameworks. While the topics are different, one thing that becomes evident as we look across these narratives and illustrations of a conceptual framework is the ways in which the parts and whole of a study fit together, that is, the methodological ecosystem of a specific study. The conceptualization and construction of a conceptual framework is a valuable and generative part of the research process because it helps to bring all of the various study contexts and frames together in explicit and transparent ways that help tease out the interactions, tensions, and synergistic qualities of the parts and the whole. We believe that this process should be active, recursive, creative, and reflexive. In the next chapter, we build on the foundations offered in Chapters One and Two, as well as describe the role and process of qualitative research design and expand on our conceptualization of what criticality in qualitative research looks like.

Recommended Practice 2.1: Conceptual Framework Memo

In our teaching of students and advising of master’s theses and doctoral dissertations, we have found that memos, because they are largely seen as internal sense-making documents, allow for a kind of written engagement that frees students from the constraints of formal genres of writing. Memos can be informal or formal and can be intended solely for personal use or can serve other roles (e.g., used as communication among research team members or with various thought partners and advisers). As such, the author can truly explore ideas rather than put forth a sculpted and refined document. We therefore ask our students, in addition to writing an identity/positionality memo (see Chapter Three), to write an exploratory conceptual framework memo early in the development of their research studies. This assignment creates a structured opportunity to develop a narrative (that may include a corresponding graphical representation) of your emerging conceptual framework, receive feedback, and use it to engage with others early and continuously to develop and refine the research. A conceptual framework memo can include the following focal sections (but we argue that these can be constructed in many different ways as per your preferences in terms of how you process information):

Topics to include/consider in this memo:

- Research topic, including context, setting, population in focus, and broad contextual framing

- Research questions and study goals

- Role of the following to your potential research:

- Self (e.g., social location/identity and positionality)

- Context(s) (e.g., institution/community, state, country, historical moment)

- Goals (e.g., personal, practical, and intellectual—see Maxwell [2013] for a discussion of these goals)

- Description of the relationship between your research question(s), conceptual framework, and research design choices (may also include bullet points of research design)

- Overall methodological approach and potential research methods

- The tacit theories that have informed your research question(s) and/or topic

- The formal theories that guide and inform your study (theoretical framework)

- Ways that you plan to implement structured reflexivity (individual reflection and dialogic engagement) throughout your study

Recommended Practice 2.2: Concept Map of Conceptual Framework

In this exercise, you visually map, in graphic form, the ways that your theoretical framework, research questions, researcher identity, informal theories, and so on relate and map onto each other and the methods you choose. This can be a productive activity, especially for visual learners. You then narrate this graphical representation of your work. This narrative is similar to the conceptual framework memo exercise described above but focuses on the explication of your graphic. For some researchers, the task of visually mapping their conceptual framework can seem quite daunting (we include ourselves in this category). Thus, it can make this process more productive to also verbally narrate your conceptual framework and how your theoretical framework, research questions, researcher identity, informal theories, and so on relate with and map onto each other and the chosen methods. This narrative may take the form of a short paragraph or may be longer and more closely resemble the conceptual framework memo.

Example 2.1: Conceptual Framework Memo and Accompanying Concept Map

An Autoethnography of Resilience:

Understanding Native Student Persistence at a Predominantly White College4

Jaime Nolan

October 2014

In 1774 representatives from Maryland and Virginia, as part of a treaty process, invited young men from the Six Nations to attend the college of William and Mary—founded in 1663. The tribal elders declined the offer with these words:

We know that you highly esteem the kind of learning taught in those Colleges, and that the Maintenance of our young Men, while with you, would be very expensive to you. We are convinced that you mean to do us Good by your proposal; and we thank you heartily. But you, who are wise must know that different Nations have different Conceptions of things and you will therefore not take amiss, if our ideas of this kind of Education happen not to be the same as yours. We have had some Experience of it. Several of our young People were formerly brought up at the Colleges of the Northern Provinces: they were instructed in all of your Sciences; but when they came back to us, they were bad Runners, ignorant of every means of living in the woods . . . neither fit for Hunters, Warriors, nor Counsellors, they were totally good for nothing. We are, however, not the less oblig’d by your kind offer, tho’ we decline accepting it; and, to show our grateful Sense of it, if the Gentlemen of Virginia will send us a Dozen of their sons, we will take Care of their Education, instruct them in all we know, and make Men of them.

(Palmer, Zajonc, & Scribner, 2010, p. 19)

When I arrived at South Dakota State University (SDSU) in 2011 as the university’s first full-time chief diversity officer, one of the primary constituencies with whom I began working were Native students, faculty, staff, and communities. Reflecting on my experience thus far, the above quote is significant to me because the 1774 dialogue is in many ways still occurring in education institutions and in wider social discourses. Palmer’s reflection on the response of the elders embodies my core operating principles as an administrator, educator, advocate, and developing researcher: Every student should have access to

an education that embraces every dimension of what it means to be human, that honors the varieties of human experience, looks at us and our world through a variety of cultural lenses, and educates our young people in ways that enable them to face the challenges of our time. (Palmer et al., 2010, p. 19)

The significance of my work lies in the disparity in educational access, opportunity, and equity available to Native communities in South Dakota, where Native Americans comprise 8.9% of the population, but only 1.4% of the students at SDSU (SDSU, 2013; U.S. Census Bureau, 2013). According to the National Indian Education Study (NIES, 2011), Native students experience culturally unresponsive and devaluing PK–12 learning environments, which reflect a history of institutionalized poverty and racism (U.S. Department of Education [DOE], 2012). The lack of Native student persistence at SDSU has continued to be a troubling issue, with the number of Native students at the university falling over the past 3 years (Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System). Yet, Native students do persist and graduate from SDSU, which indicates that resilience might underlie Native student persistence. I wish to collaboratively negotiate an understanding of the experience of Native students who persist and succeed at SDSU. The primary research question guiding my work is: How do Native students at South Dakota State University make meaning of their educational experiences?

Viewing the PK–12 and higher education systems as fundamentally integral to each other, I seek to understand Native students’ experiences and understanding of education, community, and culture, to support our Native students through fostering their own sense of empowerment. This work will also make visible to higher education institutions the steps needed to prepare for Native students as well as students from all underrepresented communities. Subsequent questions that may guide my work include, but are not limited to:

- How do Native students understand the roles of culture and community, and how do they negotiate cultural borderlands that impact their educational experiences?

- How can our university foster a sense of empowerment through building sustainable university-community partnerships and instituting social justice–oriented initiatives in outreach, community building, teaching, and curriculum?

Resilience and Persistence: An Emerging Conceptual Framework

Problematized in U.S. DOE (2012) and SDSU (2013) institutional data, I will inquire into Native students’ PK–16 educational experiences contextualized in the cultural borderlands they continuously negotiate. Spring (2009) characterizes the history of the education of Native peoples as de-culturalization in which the dominant culture has used education as one mechanism to destroy Native culture and assimilate indigenous peoples. Others, notably Watkins (2001) have noted similar processes specific to the education of African Americans. U.S. DOE (2012) data suggest that Native students’ education continues to perpetuate de-culturalization through what Freire (1970/2000) characterized as an oppressive banking system of education, which disempowers and oppresses Native students and communities.

Theoretical Context

Theoretically, I situate my work in the literature on resilience (Hauser & Allen, 2007; Masten, 2001; Masten, Herbers, Cutuli, & Lafavor, 2008). Masten (2001) offers a counternarrative to conventional understandings of human resilience, usually portrayed as remarkable and extraordinary. Rather, resilience results “in most cases from the operation of basic human adaptational systems”: “If those systems are protected and in good working order, development is robust even in the face of severe adversity; if these major systems are impaired, antecedent or consequent to adversity, then the risk for developmental problems is much greater, particularly if the environmental hazards are prolonged” (Masten, 2001, p. 227).

In all social contexts, including educational institutions, primary factors associated with resilience include (Hauser & Allen, 2007; Masten, 2001; Masten et al., 2008):

- Connections to competent and caring adults in the family and community

- Cognitive and self-regulation skills, self-reflection, self-complexity, and agency

- Positive views of self

- Motivation and ambition to be effective in the environment

The above factors comprise “coherent narratives” of long-term accounts of negotiating disappointments and successes filled with themes of change and connection to the past (Hauser & Allen, 2007). Theoretical contextualization of Native student academic persistence as a process of resilience is consistent with the positive deviance (PD) research framework (Pascale, Sternin, & Sternin, 2010) discussed in methods below.

An Emerging Conceptual Framework

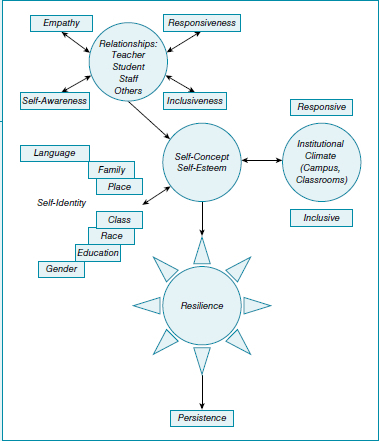

The conceptual framework for my work is emerging from a preliminary collaborative research project on which I serve as principal investigator at SDSU as well as preliminary data from a university climate survey for which I am co-principal investigator. My co-researchers include Native students, who have persisted and thrived in an environment often overtly hostile to them, as well as faculty and staff from the American Indian Education and Cultural Center (AIECC). Based on my current work, as well as preliminary investigation of the literature on resilience, I have developed the preliminary conceptual framework shown in Figure 1.

Major concepts represented in Figure 1 include:

- Persistence: the ability to enter the university and persist through graduation

- Resilience: the process of negotiating adversity and thriving in an education setting

- Self-concept/esteem: the view of oneself along personal and academic domains

- Relationships: healthy, caring, and supportive connections

- Self-identity: the complex understanding of self

- Institutional climate: the living, learning, and work environment

Relationships. Native students have articulated that relationships with teachers, students, staff, and other members of the community are crucial to their persistence and success. The importance of relationships emerges for Native students from the central role of familial and community ties in their lives. Many of the most important relationships of which our students have spoken have been of deep educational value involving family and community members. Productive relationships are filled with empathy, awareness of self (assumptions, biases, prejudices, etc.), responsiveness (Castagno & Brayboy, 2008), and inclusiveness. According to our students, and confirmed by scholars such as Spring (2009), an impediment to developing such deep pedagogical relationships is a lack of understanding of the centrality of connection in education institutions. The arrows connecting the characteristics of relationship with the central node in the concept map are bidirectional, indicating that understanding in relationship is mutually supporting and evolving. The line connecting the relationship node to the self-concept/self-esteem node is unidirectional to illustrate the importance and impact of connection to self-concept and self-esteem.

Self-identity. Identity is complex, and in my emerging framework, foundational aspects of identity salient to this work include, but are not limited to, language, family, place, culture, class, race, educational experience, and gender. I denote self-identity and its salient factors in Figure 1 with broken lines to indicate the intersectionality and complexity of identity. Importantly, the line connecting self-identity to self-concept and self-esteem is bidirectional, which indicates the recursive and evolving nature of the relationship between self-identity and self-concept and self-esteem.

Institutional climate. Rankin and Reason (2008) conceptualize campus climate as complex social systems defined by relationships between faculty, staff, students, bureaucratic procedures, institutional missions, visions, and values, history and tradition, and larger social contexts. An institutional climate in which students thrive rather than merely survive (Rankin & Reason, 2008) is characterized by valuing difference, inclusiveness, and responsiveness. Native students have expressed a preference for institutional spaces in which they have felt an investment in their presence and success. The arrow connecting institutional climate with self-concept and self-esteem is bidirectional, which indicates a synergy between the success of Native students and their value to educational institutions.

Figure 1 Conceptual Framework Denoting the Process of Academic Persistence of Native Students.

Self-concept and self-esteem. A Native student’s self-concept and self-esteem is significantly impacted by her or his identity development, the institutional value placed on her or his presence, and the relationships she or he is able to create and maintain. The connecting arrows between all of these elements are bidirectional, which indicates that students and the institution can thrive and are integral to each other. A healthy self-concept and self-esteem promoted and valued by the institution can benefit the institution, foster Native students’ sense of resilience, and contribute to their persistence in higher education.

The Role of Self and Context

October 2011: Butterfly Knowing and Learning to See in the Dark

It’s fall in South Dakota. The day is azure blue and ochre and my breath catches as I breathe in the cool morning air and walk to the university car that will take me to the other side of South Dakota. I am in my first four months at SDSU and have been asked to accompany a journalism class to the Rosebud and Pine Ridge Indian reservations. This is my first trip across the state, which is much larger than I had imagined it to be. The entire state population is approximately 735,000 and has an area of more than 77,000 square miles. There is something about the vastness of this state and it being very sparsely populated that impacts my sense of place. I feel very small driving across the seemingly endless prairie and as I look up at the huge sky I feel as though my face is pressed against glass. I pause and as I look into the clouds I know that I am an outsider looking in. As we move through rolling hills and oceans of prairie grass I sense the deep and tragic beauty of a brutal history and feel a sadness deeper than any sea I know.

Delores, the professor teaching this course and leading the group, is Lakota and grew up in Pine Ridge. She has assigned her students to write stories about young people on the reservation and in each story they will write, she requires them to find the positive. She will not allow them to focus on clichéd tragedy. In spaces that seem dark and hopeless, they instead must find beauty and possibility. The students initially are righteously indignant and express frustration because they believe the truth lies in alcoholism, suicide, and abuse—in their uninterrogated white privilege. And even in the spaces where these things are part of the truth, the students do not see the transgenerational trauma and the role that deep poverty plays in all that is here. And, as members of the dominant culture, they certainly do not see their role in all of this. I then sense something familiar to me. In this moment, there is the presence of mestizaje, mestiza consciousness, where paradox can be held. Where there is light in the darkness.

As our time there comes to an end, I notice a quiet change beginning to take place in our students. This change, although powerful, is like a chrysalis, gossamer and fragile. Their words are not as judgmental, and they take delight in all that they have learned; what they have learned from people they had believed had nothing to offer them. There is the beginning of humility where there was arrogance. Instead of patronizing tones, there is the whisper of appreciation and respect.

The night before we are to leave, I am invited to attend a sweat with Dolores. The night is cold and clear and the sky is bright with stars. There are four others besides us who are attending the sweat. The sweat begins with a prayer from the man who is guiding the ritual. He prays to Tunkashila, which in Lakota means grandfather and/or Great Spirit. He asks that Tunkashila watch over Delores and me as we work with their young people and asks Tunkashila to guide us in our work so that the young people who come to SDSU can learn and bring their learning back to the people. Then each of us participating in the sweat is asked to offer a prayer. When it is my turn, I express my gratitude in being invited to be there and also express my thanks and acknowledge that it is an honor to be given the opportunity to work with their young people. I promise that I will do all that I can to see that their children are valued, nourished, and supported in who they are. This is something I do not take lightly. I feel the weight of it, though it is not heavy. It lives in the space between beats of my heart and whispers the truth to my bones in the quiet of every dawn.

My self. In many ways, I represent the oppressor and the oppressed, which has been a borderland (Anzaldúa, 1987) in which I have struggled throughout my life. Being a mixed-race person—Latina and White—I have experienced racial and class marginalization in the context of my own family, the product of an undesirable marriage where working class and brown skin were disdained. At many points in my life, I have struggled with the assumptions that others have placed on me. I am well educated but have experienced being unemployed and struggled against the possibility of living in poverty. As a single mother, I have had to fight against the assumptions foisted on me and my sons about what constitutes an “intact” and “normal” family. Yet I have paradoxically moved through the world with a sense of privilege as well. I have learned that living this paradox has provided me with a lens through which I am able locate myself as a mestiza and position who I am in the variety of contexts in which I find myself. I have been, as Galeano (1989) writes, chopped into pieces and forced to interrogate my privilege and my assumptions in order to reassemble myself in a continuous, contextual, relational process of understanding my self, my life, the academy, and my role in it.

The context. My work with Native communities bears special meaning in a state where nearly 10% of the population is Native, where the land on which our university is built was paid for with the blood of Native peoples, where Native communities comprise the two poorest counties in the United States, where discrimination is institutionalized and taken for granted, including on the campus where I work. The narrative of this land is a narrative of tragedy, yet it is a narrative that has been silenced as an institutionalized narrative of progress—Manifest Destiny. At this historical moment, indigenous peoples throughout the world are engaged in an attempt to indigenize the academy, to reinsert silenced narratives into what the historian Ronald Takaki called the Master Narrative of American History. American history, my personal history, our individual histories, contain narratives of tragedy with which we have never fully embraced. This is my entry point, my connection, to this work, to negotiate the tragedy of oppression for both the oppressed and the oppressor.

Synthesis

My overarching research question investigates the meaning of lived experience for a group of students whose lived experience has been marginalized and deprecated for generations. These students’ lived experience is unique because it occurs in the context of permeable cultural borderlands through which these students live and move. They live their histories both in the center and in the peripheries of multiple cultures. Understanding their experience as a process of resilience is consistent with a framework inclusive of concepts of self, relationships, and the institutional climate.

Research Design

While I will use quantitative data to initially frame and problematize the issue of the persistence of Native students in higher education, specifically at SDSU, my work will reflect a human science research design (van Manen, 1990). Epistemologically, I situate my work in the hermeneutic tradition (Gadamer, 1975; Ricoeur, 1980; van Manen, 1990) because I seek to investigate the meaning and understanding of lived experience. I also proceed from an advocacy-participatory paradigm in that my work will propose an agenda for reform with the goal of changing the lives of all participants: students, the institutions and communities in which they live, and my life as researcher (Creswell, 2007). The advocacy-participatory paradigm finds further expression in the positive deviance model based on the following premises (Pascale et al., 2010, p. 4):

- Solutions to seemingly intractable problems already exist.

- They have been discovered by members of the community itself.

- These innovators (individual positive deviants) have succeeded even though they share the same constraints and barriers as others.

Positive deviance recognizes “the community’s latent potential to self-organize, tap its own wisdom, and address problems long regarded with fatalistic acceptance” (Pascale et al., 2010, p. 7). The model acknowledges that once communities discover and leverage existing solutions by drawing on their own resources, “adaptive capacity extends beyond addressing the initial problem at hand” and enables “those involved to take control of their destiny and address future challenges.” Positive deviance allows us to move away from and deconstruct what has been a normalizing, deficit lens through which researchers often view communities and conduct studies (Delpit, 2012; Pascale et al., 2010).

Data collection methods will include a series of phenomenological conversations (Seidman, 2006) and the collection of visual data through auto-photography (Blackbeard & Lindegger, 2007; Noland, 2006; Croghan, Griffin, Hunter, & Phoenix, 2008) and through various autoethnographic narratives. Secondary quantitative data from the U.S. DOE (2012) and institutional data from South Dakota State University (2013) specifically related to our Native students will be used to contextualize the study. I will analyze the data inductively to generate themes (Smith, Flowers, & Larkin, 2009), and I will represent my analysis as collaborative autoethnography through vignettes and visual data.

Conclusions

Considering long historical narratives of poverty, racism, and sociocultural oppression inherent in the experiences of Native students, these cultural/educational dynamics have significant implications for the holistic well-being of our Native students at all levels of education. If universities desire to build inclusive communities, they must understand and value the experiences of students and faculty from historically marginalized and traumatized populations. The long-term value of this research lies in outreach, building the capacity for inclusive communities, and realizing social justice, which represents the larger value upon which the purpose of education rests (Carnevale & Strohl, 2013; Delpit, 2012; Nieto, 2010).

Questions for reflection

- What is a conceptual framework?

- What are the roles and uses of a conceptual framework?

- How does a conceptual framework guide and ground empirical research?

- How can you use a conceptual framework to build and refine your research questions and study as a whole?

- How do you construct a conceptual framework?

- What is the relationship between a conceptual and theoretical framework?

- What are the component parts of a conceptual framework, and how do they fit together?

- How do conceptual frameworks evolve?

- What are the multiple possibilities for developing and representing conceptual frameworks in narrative and graphic form?

Resources for further reading

Conceptual Frameworks

Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2016). Designing qualitative research (6th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ravitch, S. M., & Riggan, M. (2012). Reason & rigor: How conceptual frameworks guide research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Theoretical Frameworks

Anfara, V. A., & Mertz, N. T. (2015). Theoretical frameworks in qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Anfara, V. A. (2008). Theoretical frameworks. In L. Given (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative methods (pp. 869–873). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Argyris, C., & Schön, D. A. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Maxwell, J. A., & Mittapalli, K. (2008). Theory. In L. Given (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative methods (pp. 876–880). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Tavallaei, M., & Abu Talib, M. (2010). A general perspective on role of theory in qualitative research. The Journal of International Social Research, 3, 570–577.

Online Resources

Sharpen your skills with SAGE edge

Visit edge.sagepub.com/ravitchandcarl for mobile-friendly chapter quizzes, eFlashcards, multimedia resources, SAGE journal articles, and more.

Endnotes

1. While discussed briefly in this chapter, we extensively describe the processes of dialogic engagement and structured reflexivity in Chapter Three.

2. See Maxwell (2013) for a detailed discussion of personal, practical, and intellectual goals, especially the five kinds of intellectual goals he describes.

3. For a useful discussion on race as a social construction with changing meanings over time, see Omi and Winant (1994).

4. The references in the student work throughout the book have not been included due to constraints on space.