Chapter Three Critical Qualitative Research Design

Chapter Overview and Goals

This chapter offers what we think of as a holistic and integrative approach to qualitative research design that supports criticality in qualitative research. Our primary goal in this chapter is to conceptualize qualitative research design directly in relation to the overarching and foundational goals and values of qualitative inquiry, with a particular focus on engaging the complexity of, and spheres of influence on, people’s lives and experiences. Research design choices should be made with the guiding goal of seeking criticality and complexity through thorough contextualization. We describe qualitative research design as a dynamic, systematic, and engaged process of planning for depth, rigor, and the contextualization of data. It entails understanding and planning for the relationship of having a solid, detailed, intentional research design that still remains open to the kind of inductive and emergent methods required for research to be responsive and reflective of lived complexity.

We begin this chapter by defining qualitative research design. Then we detail the broad design processes, which include (a) developing study goals and rationale; (b) formulating guiding research questions; (c) developing the study’s conceptual framework and linking it to research design; (d) developing a theoretical framework; (e) exploring the relationship between research design, methods choices, and writing; and (f) planning for validity and trustworthiness in/through research design. Throughout these sections, we offer suggestions and examples of activities to help guide novice and veteran researchers through the various design stages while still highlighting the recursive and iterative nature of qualitative research. This chapter culminates with a discussion of critical qualitative research design in which we specifically discuss our approach to qualitative research design.

By the end of this chapter, you will better understand

- What qualitative research design means and entails

- The role of research questions in guiding qualitative research design

- How to develop study goals and a study rationale as part of a systematic design process

- What it means to formulate (and iterate) the guiding research questions of your study

- How to link your conceptual framework to your research design

- How to develop your theoretical framework and think about its value for your research design

- The differences between a literature review and a theoretical framework

- The role of pilot studies in qualitative research and the implications for your study design

- The value of vetting, rehearsing, and piloting data collection instruments

- The role of writing in relationship to research design and methods choices

- How structured reflexivity practices, including memos and dialogic engagement practices, can inform, guide, and complexify your research design

- How to plan for validity and trustworthiness in/through your research design

- How to critically approach research design

Research Design in Qualitative Research

Qualitative research design is, most basically, the way that you, as a researcher, articulate, plan for, and set up the doing of your study. Research design is the overall approach to how a researcher (or research team) bridges theory and concepts with the development of research questions and the design of data collection methods and analysis for a specific study. This research design plan is based on an integration of the theories, concepts, goals, contexts, beliefs, and sets of relationships that shape a specific topic. In addition, it is grounded in and shaped by a response to the participants and contexts in which the study is carried out.

In a solid research design, theory and key guiding constructs are clear, and methods are built out of theory in ways that reflect prior learning within and across relevant fields; this theoretical examination of core concepts in the study sets the stage for a rigorous, systematic process of gathering and analyzing data.1 Our perspective on qualitative research design is that every aspect of a study, from the early development of its guiding research questions to the selection of setting and participants, to the ways that we seek to understand the micro and macro contexts that shape all of this, is in a constant state of complex intersectionality2 and dynamic movement.

The qualitative research design process begins at the point of interest in a topic and/or setting. From there, you engage in a process of active exploration into fields, concepts, contexts, and theories that help you to understand what you seek to know and how you seek to know it. The guiding research questions, which are cultivated through structured processes of learning, reflecting, and engaging in dialogue, are the glue between every aspect of research design. The centrality of research questions to the research is why it is vitally important to understand the core constructs of your research questions. Furthermore, the ways in which researchers need to be responsive to the phenomena and contexts of study settings means that research questions may evolve over time. This requires a mind-set that allows you to not only work hard to refine a set of research questions and a matching research design but also adopt an approach to the research that is flexible and responsive to the realities on the ground once the study begins.

As with research questions, the overall research design process is also inductive and emergent so that data collection and analysis processes can be responsive to real-time learning. This can include making changes, modifications, and/or additions to data collection methods. It can also mean that data analysis is ideally not only summative, or at the end of data collection (as is commonly the case), but is employed as a generative design tool that begins with formative analysis early on that can shape subsequent data collection and then that analysis is engaged in throughout every phase of a study. As data are collected and analyzed, aspects of the research design may change to respond to emerging learnings and contextual realities that require engaging deeply with the data as they are collected.

Data collection and analysis should not be seen as two separate phases in the research process; they are iterative and integral to all aspects of qualitative research design. The notion of the “inseparability of methods and findings” (Emerson, Fretz, & Shaw, 1995)3—meaning that how a study is structured and how data are collected has everything to do with the nature and quality of the data and therefore the analyses and findings that emerge from the research—underscores how integral and connected all aspects of the research process are. This connected aspect of the qualitative research process highlights the need for flexible research design. Qualitative research design often involves simultaneous processes of “collecting and analyzing data, developing and modifying theory, elaborating or refocusing the research questions, and identifying and addressing validity threats” (Maxwell, 2013, p. 2). Qualitative research design is fluid, flexible, interactive, and reflexive (Hammersley & Atkinson, 2007; Maxwell, 2013; C. Robson, 2011). Your role, as a researcher, is to connect (and reconnect) the dots between all of these intersecting parts.

Overview of the Qualitative Research Design Process

In the sections that follow, we describe the processes central to qualitative research design. Qualitative data collection is iterative and often inductive, so it is important that there is a structured design approach that can help the study to achieve rigor and validity. It is the interplay between structure and flexibility that helps those who engage in qualitative research achieve validity through the collection and analysis of a quality data set that truly matches the goals, contexts, and realities that shape any given research project. A key aspect of this flexible approach to research design is understanding the range and variation of methods choices—and how they can be used creatively and responsively—so that they are employed in ways that help achieve (and even clarify) the goals of a specific study. What follows is a description of the key aspects of qualitative research design:

- Developing study goals and rationale

- Formulating (and iterating) research questions

- Developing conceptual frameworks in research design

- The focused development of a theoretical framework

- Exploring the relationship between research design, methods choices, and writing

- Planning for validity and trustworthiness in/through research design

Understanding each of these aspects of qualitative research design will be helpful to your study planning and writing processes. It is important to note that while we are laying the design process out in what may read like phases, qualitative research design, at its core, is not a linear process. We try to highlight the ways that research design evolves and changes through the recommended practices and examples in the chapter and the appendix.

Developing Study Goals and Rationale

Most studies begin broadly with an interest or a concern of a researcher or group of researchers. What becomes important, as a research study begins, is to explore and frame out the key goals of the study. As mentioned briefly in Chapter Two, Maxwell (2013) discusses the personal, practical, and intellectual goals of qualitative studies and suggests that you examine your understandings of study goals through these three broad conceptual categories. There are multiple goals for empirical studies, including exploratory goals (seeking to understand something about which little is known in an exploratory rather than conclusive way), descriptive goals (seeking to describe a phenomenon or experience), relational goals (trying to see connections between multiple variables and sets of ideas), and causal or explanatory goals (trying to explain causal processes within various phenomena) (Hart, 2001). It is vital for researchers to begin by critically considering the goals and motivations inspiring your research. Doing so requires, among other things, paying focused attention to the values and assumptions underlying the goals for your research and the beliefs that guide your study.

To engage in an intentional and systematic process of developing a solid understanding of the goals of your research study, we suggest a reflective inquiry process that has built into it a structured dialogic engagement around an exploration of the goals and what we think of as “the goals behind the goals,” or the next layer of what is motivating your research study. By next layer, we mean that after the main goals of a study, there are usually other, less obvious, goals that need to be explored so that they become transparent and useful to thinking about how they shape your study. We have found that asking yourself (and being asked by others) a set of strategic questions can guide an exploration of the goals of a developing study. Examples of these strategic questions are detailed in Table 3.1.

These kinds of reflexive questions help you to refine your sense of the purposes of your study, which in turn helps you to conceptualize the parameters and content relevant to the study and begin to consider its possible uses, audiences, rationale, and significance.

Related to understanding your goals as a researcher is the development of the rationale of the study. A rationale is the reason or argument for why a study matters and why the approach is appropriate to the study. Rationales can range from improving your practice and the practice of colleagues (as in practitioner research), contributing to formal theory (e.g., where there may be a gap in or lack of research in an area), understanding existing research in a new context or with a new population, and/or contributing to the methodological literature and approach to an existing corpus of research in a specific area or field. Thinking about and answering the questions in Table 3.1 can aid in this process. Considering these kinds of questions is central to developing empirical studies, and it is important to understand that these rationales and goals will also lead you to conduct different types of research, guiding your many choices—from the theories used to frame the study to the selection of various methods to the actual research questions as well as designs chosen and implemented.

There are many strategies for engaging in a structured inquiry process and through it an exploration of research goals and the overall rationale of a study. These strategies can include the writing of various kinds of memos, structured dialogic engagement processes, and reflective journaling. Across these strategies, creating the conditions and structures for regular dialogic engagement with a range of interlocutors is an absolutely vital and necessary part of refining your understanding of the goals and rationales for the research. We describe each of these strategies in the subsequent sections.

Memos on Study Goals and Rationale

Memos are important tools in qualitative research and tend to be written about a variety of different topics throughout the phases of a qualitative study. Memos are a way to capture and process, over time, your ongoing ideas and discoveries, challenges associated with fieldwork and design, and analytic sense-making. Depending on your research questions, memos can also become data sources for a study. There is no “wrong” way of writing memos, as their goal is to foster meaning making and serve as a chronicle of emerging learning and thinking. Memos tend to be informal and can be written in a variety of styles, including prose, bullet points, and/or outline form; they can include poetry, drawings, or other supporting imagery. The goals of memos are to help generate and clarify your thinking as well as to capture the development of your thinking, as a kind of phenomenological note taking that captures the meaning making of the researcher in real time and then provides data to refer back and consider the refinement of your thinking over time (Maxwell, 2013; Nakkula & Ravitch, 1998). While we find writing memos to be a useful and generative exercise, both when we write and share them in our independent research and when we share them within our research teams, they may not serve the same role or fulfill the same purposes for every researcher. We suggest other activities and a variety of memo topics throughout the chapter (and the book) to encourage and foster engagement through writing or what we term structured reflexivity.

We hope that Examples 3.1 and 3.2 (as well as the two excellent examples included in the appendix that we urge you to read) help you to see and appreciate the incredible range and variation of approaches to and foci within these kinds of memos as well as the multiple writing styles used by the authors. We want to also remind you, after reading these, that while they are personal sense-making documents, engaging in discussion of them with colleagues and advisers is an important part of making sense of and thinking through these various influences on your thinking and being as researchers. These dialogic processes are described in the next section.

Terms and Concepts Often Used in Qualitative Research

Fieldwork: In qualitative research, fieldwork entails the process of collecting data in a natural setting. This means in a setting in which the phenomenon would naturally occur (e.g., a neighborhood, organization, institution, or workplace). The term fieldwork, which comes from the ethnographic tradition of participant observation, is often used in qualitative research to refer to the located process of data collection.

Recommended Practice 3.1: Researcher Identity/Positionality Memo

The purpose of a researcher identity/positionality memo (Maxwell, 2013)4 is to provide a structure, at an early stage in the research development process, to facilitate a focused written reflection on your researcher identity, including social location, positionality, and how external and internal aspects of your experiences and identity affect and shape your meaning-making processes and influence your research.

We recommend that researchers with all levels of experience write this kind of memo and that you engage with this memo and add to or revise it over the course of a given study. In addition, we encourage researchers to write a new memo with each new research project since one goal of the memo is to connect aspects of your identity to the research topic and phases of the research process itself. For example, this memo is a required assignment in the doctoral-level methods courses we teach, and it is assigned before the students walk too far down the path of their independent research so that there is opportunity to challenge foundational assumptions and the relationship of who they are to the proposed study. Then the students are asked to reflect back on that memo once engaging in fieldwork so that they can further reflect on the influence of their positionality in the context of their interactions with study participants. We also recommend this memo to high school students with whom we conduct youth participatory action research (YPAR) as a way to help them understand the nonneutrality of research and to locate themselves within their justice-oriented research projects. Students of all ages and levels of research acumen find the memo to be both valuable and generative (and routinely describe the process of writing it as “more challenging” than expected).

Our students and colleagues share that they find writing this memo not only vital to their own critical understandings of themselves and their identities but also invaluable to clarifying their understandings of the topic and design process. Students also report that they revisit this memo throughout the research process to help illuminate their thinking and monitor any biases they described in the memo. Some choose to write subsequent identity memos as aspects of their identities emerge as relevant to their inquiries. (Example 3.1 is a second researcher identity/positionality memo.) We encourage our students (and you) to share these memos with a range of thought partners in ways that help you to hear constructively critical feedback on your biases as they relate to your positionality and research.

Topics to consider exploring in a researcher identity/positionality memo include the following:

- Positionality (relationship of self and roles to study topic, setting, and/or goals)

- Social identity/location (e.g., social class, race, culture, ethnicity, sexual orientation/identity, and other aspects of your external or internal identity)

- Interest in the research topic and setting

- Reasons and goals motivating the research

- Assumptions that shape the research topic and research questions

- Assumptions about the setting and participants and what shapes these

- Biases and implicit theories and the potential implications/influences of these for your research

- Guiding ideologies, beliefs, and political commitments that shape your research

- Intended audiences and reasons for wanting to address/engage them

- Other aspects of your identity and/or positionality in relationship to the research

- If engaging in team research, looking at the demographics and other features of the team in relation to your own identity and the research topic, context, and process

The above list is primarily meant to generate ideas. We are hesitant to include a list at all because we do not want to limit the possibilities; however, we provide one to help guide possible directions for this process. Still, we want to underscore that there is no wrong way of composing this memo, and, furthermore, that you can write and share multiple memos throughout the research process that relate to these topics since this kind of reflexive writing is not meant to only happen at the outset of your research.

We suggest that you consider sharing these memos with trusted colleagues and friends who can help you consider these issues productively through engaging in focused dialogue about the connections between self and the research at hand. We have also found that the sharing of these memos on research teams can be a vital source of thoughtful sharing that can generate powerful learning and exchange and help to situate the research team as a community of practice or inquiry group.5

In Examples 3.1 and 3.2, we include two different examples of researcher identity/positionality memos from past and present doctoral students at different stages in the research process. In Appendixes D and E, we provide two additional examples so that you see the range of ways that students approach these memos.

Example 3.1: Researcher Identity/Positionality Memo

Susan Feibelman

Researcher Identity Memo 2

October 14, 2012

Why am I interested in the gendered nature of school leadership?

TAKE ONE (excerpted from my dissertation proposal): My interest in this topic is rooted in my personal experience as a school leader. Grounded in my first-hand experience with mentor-protégé relationships in both public and independent school settings, as well as the beneficial peer-to-peer mentoring relationships I have with other women leaders. In recent years, these conversations have acquired a frankness that reveals a growing impatience with the androcentric nature of independent school leadership and the fomenting of a “new boys club” that ensures the patriarchy’s longevity (Baumgartner & Schneider, 2010). Repeatedly women’s (White and of color) personal narratives describe the systematic regularity with which they are passed over for influential leadership roles. Our mutual interrogation of the context in which this practice unfolds has spawned a “mental itch” (Booth, Colomb, & Williams, 2003, p. 40) that is reinforced by a compelling body of research, which describes a similar trajectory for women leaders in public school. Fletcher (1999) refers to this phenomenon as “the story behind the story.”

All research—the particular question it finds important to ask, the point of view from which the question is posed, the source of the data used to find answers, and, of course, the interpretation and conclusions drawn from the analysis—are surely, albeit invisibly, influenced by the standpoint of the researcher. (Fletcher, 1999, p. 7)

Fletcher’s use of relational theory to frame her own thinking about leadership development in corporate settings has immediate application to various forms of leadership within a school community. The principle of relational theory argues,

growth and development require a context of connections . . . interactions are characterized by mutual empathy and mutual empowerment where both parties recognize vulnerability as part of the human condition, approach the interaction expecting to grow from it and feel a responsibility to contribute to the growth of the other. (Fletcher, 1999, p. 31)

Relational theory could as easily be applied to discussions about the practice of teacher inquiry and its self-reflective, mutually engaging, and action-oriented ethos.

TAKE TWO: My interest in this topic began with a question I started to raise with fellow teachers and school leaders following a student council election. Once again a female student running for the position of president had delivered a thoughtful, well-developed speech only to lose the election to a male classmate, whose speech was loosely organized and disarmingly comedic. The student voters responded to the candidate’s irreverent charm by electing him president. While names and faces would change, this gendered dynamic would be played out election, after election.

Knowing the students and their track records for working on behalf of the student body, I began to question what role gender played in the election results. I also started to look more carefully at the ways in which adults in the school community modeled gender preferences through their unspoken support of certain leadership styles over others. What then was the relationship between our students’ choices and the way we as their teachers might be prone to associate leadership with certain gender traits? Is this a topic for teacher inquiry?

Example 3.2: Researcher Identity/Positionality Memo

Personal and Professional Goals for Dissertation Study

Mustafa Abdul-Jabbar

December 12, 2012

I see my confidence growing . . . I still think it has a way to go, but I see my confidence building . . . and I feel like I have more tools at my disposal, whether it’s research or people, to be able to connect with if I’m not sure. Whereas before distributed leadership, I felt limited in that.

—Rosalie (personal interview, July 27, 2011) [school principal]

As an educational leadership doctoral student at the University of Pennsylvania, one of the chief-most issues I have sought to understand has been how school leaders cultivate trust within the educational organization. As a practitioner and school administrator in southeast Texas, an issue of practice that arose for me in my work was how to operate effectively in school organizations with low levels of trust, including how to systematically develop greater trust rapport and subsequent organizational capacity amongst instructional staff in low-level trust organizations. In pursuing research that addresses this problem of practice, I have sought to better understand how individuals within the school organization learn to trust one another and how they come to understand one another as trustworthy.

I have chosen to study relational trust within the context of the Penn Center for Educational Leadership’s distributed leadership professional development program because the leadership paradigm inherent in the program is one that moves away from a focus on school principals, as the sole drivers of teaching and learning, toward a distributed perspective as a framework for understanding leadership. Thus, acknowledging that “school leadership has a greater influence on schools and students when it is widely distributed . . . (i.e., school teams, parents, and students)” (DeFlaminis, 2011, p. 1). I feel that this leadership paradigm is more attuned to the socioemotional and social-psychological elements that are conceptual staples in research and literature on trust, more recent literature on successful leadership (see Yukl, 2009), and more consonant with my professional experience.

Distributed leadership, in that it identifies leadership as not predicated on rank/position, at least at the conceptual level, equalizes persons in the organization. For example, a teacher may be foregrounded during a particular activity while a principal is backgrounded, if the teacher’s activity is more closely aligned with the core work of the organization. Results from the 2011 pilot study into how leadership team members were conceptualizing leadership found that Archdiocese team members at the piloted school site successfully internalized this idea—that the phenomenon of leadership entails more than mere formal position or hierarchy but rather leadership practice is mutually constituted by the interaction of organizational members across various situations. It was also found that team members at the pilot school site were typically unacquainted with this definition of distributed leadership practice before their professional development sessions; thus, what they recognized as leadership practice was often broadened through their participation in the distributed leadership (DL) program.

I have chosen this program context for study because I am most interested in how teachers and administrators, operating vis-à-vis one another on more equal terms, learn to trust one another. I believe that insight into this research arena will contribute to educational leadership scholarship and, through honing my understanding of the interplay between leadership and trust in schools, help me to improve my own professional practice as a school leader.

Dialogic Engagement Practices

We refer to the idea of dialogic engagement as systematic processes for engaging in generative dialogue with intentionally selected interlocutors about (and throughout) the research process. Dialogic engagement is an incredibly important aspect of the research process (Bakhtin, 1981; 1984; Chilisa, 2012; Freire 1970/2000; Lillis, 2003; Rule, 2011; Tanggaard, 2009). While you may constantly interact with others about your research in unstructured ways, we recommend that dialogic engagement practices be intentionally structured into the design process (and the formal research design) at different stages. For example, after conducting a few early interviews, you may meet with a partner, adviser, and/or a group of peers to think through the interview instrument, share excerpts of the data to determine if the instrument is helping to answer the research questions, think about how you are responding to participants, consider how your potential biases may (or may not) be reflected in the ways you ask questions of participants, and discuss how you respond to interviewees (Tanggaard, 2009). The important point here is to build these processes into the stages of design to create accountability to multiple interpretations and to the ongoing, rigorous challenging of your biases and assumptions. While these discussions should occur ongoingly, it is important to have structured processes that highlight the iterative and recursive nature of research built into the design. Recommended Practices 3.2 and 3.3 offer suggestions for structuring such engagement. We suggest that you decide if these sessions will be recorded and/or notes will be taken by you and/or others engaged with you. The systematic recording of these conversations has proven an important aspect (for our students and in our own work) of ongoing reflection that becomes a part of the research design and process.

Recommended Practice 3.2: Structured Sets of Conversations

These conversations are intended to facilitate deliberate and structured engagement with colleagues and peers around specific aspects of the research process. This works best if a group meets regularly and is familiar with the research topics and specific research questions of all members.

Process: Each researcher creates three to four key points or questions to discuss with at least two peers. The group divides the time they have to meet equally between all group members (it is essential to assign a time keeper if multiple researchers share at a given meeting). Each researcher can structure her time based on what she hopes to get out of the conversation and articulates her hopes and goals for the session to her peers prior to or during the session. While the conversation may evolve in unintended directions, it is important to prepare for the meeting so as to focus the conversation in ways that will most benefit the researchers.

Possible questions to consider at an initial meeting:

- What are the reasons for interest in this study?

- What are the reasons for interest in this context?

- What are the various goals for this study in terms of learning and professional engagement?

- What are some motivations for wanting to do this study?

- To what audiences am I gearing the study and why?

- How does all of this potentially shape the study?

- How can I think critically about my blind spots and assumptions and how they may influence/shape the research?

- What theories might help me begin to delve deeper into this topic and why?

Possible questions to consider in ongoing meetings:

- What is shaping the study conceptually and theoretically and why?

- What assumptions continue to shape the research?

- How does the research design reflect these assumptions?

- Do I have the research design plan I need to achieve validity? In what ways might I improve on the rigor of the study?

- Have the study goals shifted or changed over time, and if so, why and how?

- What am I learning through vetting, rehearsing, and piloting my instruments?

- What do the early data suggest? For design refinements/changes? For the use of theory? For my working conceptualizations?

- How might others interpret these data and why?

The group should determine the topic or focus of subsequent meetings in advance, and members should prepare for these meetings, sharing documents such as memos, and data excerpts, archival documents for peer review and discussion. For example, the group might decide to discuss researcher bias at a meeting, and members would come prepared to discuss this topic with all or parts of their memos or research journal entries that engage this topic.

In our own research group experiences, these groups can provide access to substantive data analysis thought partners since by the time of analysis, all members will be intimate with each study’s research process and goals. So later in the life of the projects, we strongly urge a focus on data analysis, including the sharing and vetting of coding categories and analytic themes as is useful at various stages. The goal of these sessions is to talk through issues and questions in real time throughout the research cycle and to structure multiple subjectivities into the research process.

Recommended Practice 3.3: Paired Question and Reflection Exercise

This is a process, engaged in with a partner, to generate focused researcher reflection around key areas of importance in the study. These areas could be related to a variety of topics and conducted at different points in the research process. Examples of areas to consider include formative data analysis, instrument refinement, how the research questions are (or are not) being answered, participant representation, and researcher bias.

- Process: In this paired exercise, each researcher should develop two to three key questions about her research. The partner will ask the researcher these questions and take notes about how the researcher answers the questions (while also noting her own questions that arise as she listens). The partner will then share her notes with the researcher, and the pair will discuss what stood out about the answers to the questions. With the partner (and afterward individually), the researcher will reflect on her answers to the questions and consider how they align with how she believed she would answer these questions, what underlying assumptions arose during the answers, how she portrayed participants, the overall goals of the study, and so on.

We recommend that researchers write a brief memo after this process to reflect on and document the learning and any unanswered questions. These memos could be shared with the partner one more time for additional thoughts. Furthermore, it is beneficial if the pair works together over the course of the project and engages in this process at multiple points in the research process. Our students share that they find this useful throughout the process and specifically during summative data analysis.

Reflective Journaling

It is a common (and suggested) practice for qualitative researchers to keep a research journal, and we believe that this provides an ongoing, structured opportunity for you to develop a research habit that can serve to deepen your thinking about the research process by creating more regularity and intentionality around the process of reflection. Unlike memos, which are written at selected moments throughout the research process and focus on specific topic areas, the research journal is an ongoing, real-time chronicling of your reflections, questions, and ideas over time. Research journals are useful both for in-the-moment reflection and meaning making and for charting ideas, thoughts, emotions,6 and concerns over time. Recommended Practice 3.4 provides some guidance about keeping a research journal.

Recommended Practice 3.4: Research Journal

We recommend keeping a research journal that records (at least weekly) your thoughts, questions, struggles, ideas, and experiences with the processes of learning about and engaging in various aspects of research—from design through writing up the report. The main purposes of the research journal include that writing over time allows for the

- support and fostering of ongoing self-reflection;

- development and reinforcement of intentionality in research and good research habits;

- structured opportunity to develop and reflect on questions and ideas about research;

- researcher to keep valuable references that can be incorporated in future research;

- researcher to reflect on your thoughts, feelings, and practices in real time;

- formulation of ideas for action or changes in practice;

- documentation of your evolving frameworks for thinking about issues (including major turning points in your thinking); and

- development of meaningful questions for dialogic engagement activities.

Research journals can take a variety of forms and tend to be relatively informal. We recommend adopting any style or format that works for you; this means that entry length and structure will vary depending on the happenings of any given day or week. The research journal can also be an important source of data in qualitative research, depending on its relevance to the topic and research questions. A research journal can be kept on your computer, in a notebook, on a smartphone, in a Prezi, or other visual format. Make sure to keep any electronic files password protected and to securely store notebooks to protect participants’ confidentiality (some of our students use pseudonyms in their journals and memos). The goal of the journal is to find a format that allows for ongoing reflective writing throughout the process.

We argue that the research journal is vital throughout the research process, and it is important to begin the research process using this forum to document emerging thoughts that will shape the goals and rationale of your study and help you to build an argument for its significance.

Formulating (and Iterating) Research Questions

In the section above, we describe the process of moving from an interest or concern that you have been thinking about to the development of a focal research topic that is grounded in a solid rationale and a developing sense of the import of a study. Within this process of discovery comes the development and then refinement of your guiding research questions. Well-chosen research questions are vital to a research study and, in fact, are the center of research design. To collect the kinds of data you need to answer your research questions, you must intentionally map your research methods onto your research questions.

The development of cogent and researchable questions happens in many ways; central among them are engagement with existing theory and empirical studies in the fields related to your study and dialogic engagement with experts and peers who can help you think in focused ways about the goals and assumptions that frame and underlie your questions and study. Part of our argument for dialogic engagement in the process of question development is that the ways that you formulate research questions depend, to a significant degree, on how you conceptualize a topic or problem. This, as we discuss in Chapter Two, is informed in significant ways by the development of your conceptual framework. Since lived experience is complex and multifaceted, the research questions must be broken down into specific core constructs to be studied. We make a strong argument that you must carefully define each core construct because they are the building blocks not only of your research questions but also of the study itself. A conceptual framework helps the researcher to develop a cogent rationale for how you conceptualize the problem; identify the key influences, contexts, and factors; define these core constructs; and develop your working theories for what you think may be happening (Ravitch & Riggan, 2012).

For many researchers, especially those who do not have prior familiarity with a qualitative paradigm, this notion that research questions can be modified or changed, even once data collection has begun, is surprising and even, for some, causes concern about the rigor of qualitative research. It is the fact that research questions can be refined as we learn more about complex phenomenon and the theories that seek to explain them that helps a research study achieve rigor in a qualitative paradigm (Golafshani, 2003; Maxwell, 2013; Ravitch & Riggan, 2012; C. Robson, 2011). But, there must be certain conditions that allow this to be the case, which include (1) an intentionality in the process of developing and refining research questions, (2) a chronicling of the reasons for and influences on the key aspects of and refinements to research questions, (3) a vetting of suggested changes from multiple perspectives, and (4) early and ongoing data and theory analysis that informs changes to research questions.

There are multiple forms of research mapping—charting central goals, ideas, concepts, and processes in graphic form in a way that helps you to see core constructs and relationships between them—that can help you to make connections between central concepts, theories, and contextual aspects of the research. Recommended Practices 3.5 through 3.7 propose multiple kinds of research mapping exercises and share examples to suggest how they help to facilitate the research question development and iteration process.

Memos and Dialogic Engagement Practices to Support Research Question Development and Refinement

As described above, memos are useful tools for engaging in and even facilitating key aspects of the research process. In the development and refinement of research questions, we suggest that you write memos to consider what understandings and information you are seeking to gain and how these relate to each of your research questions. In Recommended Practices 3.8 and 3.9, we offer topics and prompts for memos that can assist in the development and refinement of research questions.

To refine and develop research questions, memos that address all of the topics described in the Recommended Practices 3.8 and 3.9 (core constructs, goals, and the knowledge/information sought by specific research questions) will help you to develop, scrutinize, and revise your research questions. (See Appendix F for an example of a memo about refining the research questions.) Research question development is an important process, since, as we have noted earlier, the research questions are central to the entire research process. In Recommended Practice 3.10, we outline additional ways to build on these more individualized approaches through engaging with others in dialogue about your topic and questions.

Recommended Practice 3.5: Mapping of Goals, Topic, and Research Questions

Goal mapping: At the outset of a research study, map out the goals of your study visually (and in narrative form) as a way to explore each goal and chart their connections (and possibly see disjunctures) with the developing research questions. Then prioritize and cluster these goals in ways that allow you to see connections between them and that help lead toward the transition from research goals to research questions.

- Topic and research question mapping: Mapping your research topic and questions is a very important stage in the development of your study. Begin by articulating the broad topic you are interested in for the study and then distill that into one to two more specific topics. Then, take these key concepts and transform them into early draft research questions that focus on the major constructs or concepts at the heart of the specified topic. This requires a careful attention to each word within the proposed topic and research questions as well as the implied or imagined relationships between them. We often ask students to prepare these individually and then have them vet them with a small group of peers who can ask them questions as they articulate the research questions, thereby helping them to get feedback on the meanings contained within each word of the questions. In our courses, we often workshop this in a fishbowl format so that students can watch each other engage in this process and then benefit from understanding the workings of the process as well as idea and process sharing for their research specifically.

Recommended Practice 3.6: Connecting Research Questions With Methods

In this approach to aligning your research methods onto your research questions, which is a crucial step in all qualitative research, you take each research question (and subquestion) and map your research methods onto it in two ways:

- The first way is to map the specific data collection methods that you will use to attain the information required to answer the research questions. For example, if you wish to understand how doctors implement a procedure based on what they learned in a professional development experience, you would not only want to interview them, but you would need to observe them in their daily work settings to triangulate the data. You may also choose to interview their colleagues and/or patients to see what they note about how the physicians implement their learning. You might also consider putting together focus groups to initiate “groupthink” and would certainly want to see artifacts of the professional development initiative as well as of the organization and even the individual for context.

- The second way is to map specific instrument questions onto each research question so that you are sure that your data collection instruments will in fact garner the data you will need to respond to your research questions.

See Table 5.7, Figure 5.1, and Table 10.3 for templates that you might use for this exercise. We have our students fill these out prior to class and bring them in for discussion in pairs.

Recommended Practice 3.7: Theoretical Framework Charting

To chart/map your theoretical framework, you turn to the formal theories that guide your research and represent them thematically in relation to your research questions in ways that help you to see how you are using theory to frame the research questions and perhaps the context and setting that surround them. We view this as theoretical framework building and argue that seeing the bodies of literature and guiding theories that frame the study, laid out visually, can help students to see connections and overlaps as well as tensions and disjunctures. Increasingly, our students use computer programs such as Prezi and MindMapper to engage this process.

Recommended Practice 3.8: Memo on Core Constructs in Research Questions

This memo includes defining each of the core constructs in your research questions. For example, if you are studying professors’ perceptions about the effectiveness of a civic engagement curriculum for engendering a social justice orientation in college students, you should clearly articulate what each of these constructs—that is, perceptions, criteria for judging effectiveness, civic engagement, social justice orientation—means and how you are defining them so that you will be able to understand how to approach them analytically and in terms of the research design and specific data collection methods that you would employ. In addition, you would want to consider which teachers (e.g., is it a specific group of college students using the curriculum? Are you interested in engaging with specific groups or subgroups of college students and why?). This process is intended to help you scrutinize each component part of your research questions and requires you to be precise and clear in the wording and phrasing of the questions since the entire research design will be built onto these core constructs.

Recommended Practice 3.9: Memo on Goals of Each Research Question

This memo clearly describes the goals of each of the research questions. Being clear on the goals of the research questions will help you to ensure that you are collecting the data necessary to answer them. We recommend charting out each research question and mapping goals underneath that question using bullet points to try to consider a range and perhaps even a typology of goals. This can help you to articulate each of the study goals as they relate directly to each aspect of all of the research questions.

Recommended Practice 3.10: Dialogic Engagement Practices for Research Questions

Dialogic engagement exercises are a way to engage in vital conversations about your topic and questions with people who can help to challenge and support your thinking throughout the research process. We encourage you to participate in structured sets of conversations and the paired question and reflection exercise (defined in Recommended Practice 3.2 and Recommended Practice 3.3) with peers and advisers who can help you to critically explore and challenge yourself around the following topics:

Core constructs in research questions

- What are the core constructs of your study?

- How are you conceptualizing and defining each one?

- How do others define these?

- What are other possible ways of viewing and approaching the definitions of these concepts?

- What theories help to elucidate these constructs and why?

- What constructs might be missing?

Assumptions underlying research questions

- What assumptions are embedded in your research questions?

- What is shaping these assumptions?

- What might help to challenge these assumptions?

- Do others share these assumptions? Why or why not?

- What are other circulating assumptions in the research in this area?

- What data would you need to answer your research questions?

- Are there causal relationships implied in the research questions, and what implications might this have for the research design?

- What additional information do you need to answer or conceptualize your research questions?

Conceptual Framework in Research Design

While we discussed the integrative and critical role of a conceptual framework as well as described how to develop one at length in Chapter Two, we include a brief statement about it here as well since it is such an integral and vital aspect of research design that we do not want it to be forgotten in this chapter. A conceptual framework provides a specific rationale for who and what will be focal to a study; informs your choice of an overall design approach, including site and participant selection and the entire design of a study, the designation of units of analysis in the study, and the definition of the core constructs and theoretical concepts; and places you within the research in terms of your social location/identity and positionality and its relationship to the study goals and setting. It assists you in considering design integration in terms of how the research questions and design are informed by and defined in terms of the conceptual framework. Here, we focus on one key component of research design and of the conceptual framework itself—the theoretical framework—and discuss the relationship of the process of engaging in a generative review of literature to the development of your theoretical framework and the study more broadly and its design specifically.

The Development of a Theoretical Framework

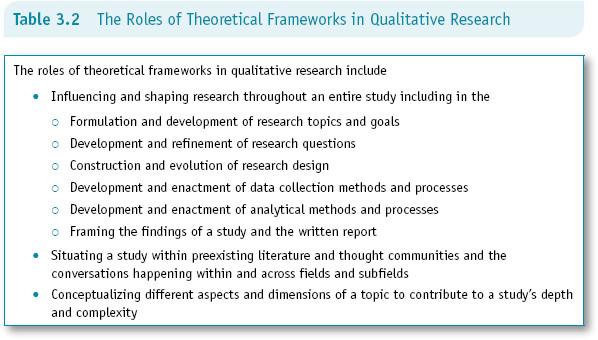

There are three key aspects that scholars of qualitative research emphasize about the use of formal theory in research design. First, the role of theory is central to developing and iterating qualitative studies in formative, ongoing, and summative ways. This occurs formatively as you develop and refine aspects of your research, ongoingly as you implement your design, and ultimately when you analyze your data in relationship to existing theory. Second, theory helps to situate a study within ongoing conversations and existing theories and findings in relevant fields. Third, theory helps to add dimension and layers of understanding about a given phenomenon and the context in which it resides because it helps to deepen and extend our understandings of these concepts by conceptualizing their construction and meaning. The roles of the theoretical framework—in focusing a study, exploring and explicating relevant meanings and ideas, situating a study in its related fields (and situating those fields in relation to each other around a specific topic or issue), and helping to reveal the strengths and challenges of a study—help us to understand that theory plays not just a theoretical or conceptual role but also a methodological one. As Table 3.2 highlights, theory guides all aspects of a research study.

We define a theoretical framework as the ways that a researcher integrates and situates the formal theories that contextualize and guide a study.7 The theoretical framework of a study is developed through a multiphased process. This process often begins with a literature search, in which you seek out and map the key bodies of literature that frame a study. The next step is engaging in a formal literature review, which entails critically integrating8 literature through writing. The term literature review implies that it is a discrete process. As described in Chapter Two, a review and integration of literature occurs throughout the entire research process.

Writing a literature review is a vital part of the process of your sense-making since it requires that you analyze and synthesize concepts from the literature (Hart, 2001). The process of engaging in this critical review of literature in the fields that contextualize your study has several interrelated processes and goals, including (a) tracing the etiology or history of the specific fields and topics related to the focal topics of your study; (b) cultivating expertise in ongoing and recent knowledge in these fields; (c) identifying the key theories, factors, and influences on the phenomenon and contexts to be studied; (d) gaining new and possibly innovative perspectives on how to conceptualize your research topic and guiding research questions; (e) learning the specific vocabulary and concepts in the fields that frame your study; and (f) identifying the range of methodologies employed to study related and even overlapping topics (Hart, 2001).

Early on and ongoingly, this process of engaging in the review of literature helps you to develop your argument for the goals, rationale, and significance of the study. This process is vital to understanding how to map the field and specific subject areas in terms of the questions and problems that have been addressed (or not), the key theories, concepts, and ideas. It is also crucial to conceptualizing and explaining the topic, as well as the major issues and debates in the field(s) since it is important to understand how various disciplines/fields frame the problem (Hart, 2001). We include specific questions that can help guide this discovery process in Table 3.3.

In order for a literature review to support your research, you should examine and articulate the aspects of the literature in an integrative and critical way, make central connections, and ask the kinds of questions described in Table 3.3. The synthesis, integration, and methodological understanding of various literatures come together to create the theoretical framework of the study. An important part of a theoretical framework often involves making an argument. You are the one who makes decisions about how to situate various literatures in relation to each other, and this is a part of how you make an argument in a theoretical framework. Your argument may also include how you frame the existing literature about a topic in relation to how it will be framed in your study. Furthermore, your argument may involve making a case (or justification) for your study.

It is important to note that the terms theoretical framework and literature review are not synonymous, although they are overlapping. A literature review is a process that helps you cultivate the theoretical framework for your study but is broader in scope than the theoretical framework since it includes all of the goals listed above and contextualizes the setting and context of the research as well as the topic and research questions. To transition from a broad literature review to a specific theoretical framework requires a careful, intentional, winnowing process in which you focus on that which is central to your study. This requires a meta-analytic and dialogic process in which you focus on the essential aspects of the formal theories that frame your core constructs in context. A useful analogy that Sharon shares in class is that Michelangelo was noted as saying that the extra marble left over from his famous statue of Moses was “that which is not Moses.” This means that he carved away that which was not a part of his vision and understanding of the core of Moses as he wished to represent him. We think of the extra marble as “that which is not your theoretical framework.” We encourage you to seek counsel as you do this, since it requires a kind of theoretical sophistication that can be daunting to a novice researcher.9

Writing memos as you develop your theoretical framework can be quite useful. We suggest that you address the memo topics described in Recommended Practices 3.11 and 3.12 as you work to develop your theoretical framework. We encourage researchers to share the theoretical framework and implicit theory memos with other individuals to receive structured feedback. In addition to composing memos, we recommended engaging in many of the specific dialogic engagement activities detailed earlier in this chapter, including Recommended Practices 3.2 and 3.3. We also suggest that you frequently discuss your burgeoning (and developed) theoretical framework with peers, colleagues, mentors, and friends. The process of developing a theoretical framework, like a conceptual framework, is iterative, and engaging in discussion, debate, reflection, and analysis with others and through writing is an important and generative part of the process.

Recommended Practice 3.11: Theoretical Framework Memo

This memo is intended to help you to develop your theoretical framework at an early stage and ongoingly at multiple points in your study. A theoretical framework memo might use some or all of the following questions as guides:

- Which theories am I using to frame the study topic and context?

- From which fields/disciplines do they hail? What bodies of research do they belong to?

- Why these fields and disciplines or bodies of literature? Why not others?

- How do these various framings intersect or relate to each other and to the research questions and setting?

- How am I using/engaging with these theories specifically and why?

- What are the benefits of these theories?

- What are the challenges of these theories?

- What assumptions underlie these theories and my choice to use them in my research?

- How do they cohere as a framework for my study? Why or why not? What can this tell me about my topic and setting?

- What argument am I making as I situate these theories?

Recommended Practice 3.12: Implicit Theory Memo

In this memo, you will consider the informal or working theories and beliefs that you bring to the research as a way to consider these influences on your research broadly and on your choice of formal theories specifically. Some of these may stem from earlier research and/or your professional practice; others may pertain more to your implicit or working conceptualizations as described in Chapter Two. To engage in a process of reflection on these ideas and explore how they shape and guide the ways that you choose to engage with theory and in the broader conceptual framework, you might address/describe the following:

- What informal theories influence my choice of specific theories? My overall conceptual framework? Why? In what ways?

- Do these informal theories come from my practice? My study of various topics? Where else?

- How do they relate to my choice of theories?

- How am I using/engaging with these theories?

- What are the benefits of these theories?

- What, if any, are the challenges of these theories?

- Describe the relationship between the “formal” and “informal” theories in the study. How do these relate?

- What do I need to understand in relation to my working propositions and theories?

- What relationship(s) do I see between my theoretical framework and my larger conceptual framework? What does this help me understand about the various aspects of my study?

Research Design, Methods Choices, and Writing

Once you have established the main goals of a study, refined the guiding research questions, framed the key theories and methods used to study the topic, and made an argument for the rationale and significance of the study to the related fields, it is time to design the study methodology by mapping your data collection and analysis methods onto your research questions directly. There are many strategies for engaging in this process, including concept mapping and the charting of how each method maps onto each research question (see Recommended Practice 3.6) since your research questions are at the heart of your research design, both conceptually and pragmatically (Maxwell, 2013). In this section, we specifically discuss site and participant selection, the iterative and recursive nature of qualitative research design, pilot studies, and forms of vetting and piloting data collection instruments that can help you to determine appropriate and generative design choices.

Site and Participant Selection

Before you consider, or as you consider, the data collection methods for a given study, you determine the study site(s) and participants; this process is referred to as site and participant selection and includes the articulation of specific selection criteria for the site and the participants within that site. Selection criteria—the criteria you use to select a setting and participants—must be clearly defined. This includes the identification and clearly articulated rationale for and justification of all choices for the site(s) you choose and whom you include or exclude in the study design. Along with this comes a discussion of any challenges and limitations that go with these choices. These issues should be articulated with transparency and a clear sense of the possible limitations of these choices as well as their benefits. In addition, in the selection of participants, the researcher must pay careful attention to issues of representation in multiple senses of that term (Mantzoukas, 2004). Representation has to do with many aspects of participants’ social identities, experiences, realities, and roles as they relate to the study context and study topic. For example, it may be role, experience, or positionality and/or social identities that shape what representation and sampling (another term for participant selection) look like for different studies. This will depend on the nature of the context and the research questions and is related to the process of mapping methods onto questions. We discuss participant and site selection as well specific sampling methods and their rationales in depth in Chapter Four.

Piloting

Piloting is a central aspect of designing and refining research studies and instruments. Piloting can take a variety of forms, including testing instruments, examining and noting bias, refining research questions, generating contextual information, and assessing research approaches and methods (Sampson, 2004). Piloting is commonly associated with the testing of data collection instruments in order to develop and refine them, which we discuss below. The term piloting is also used in reference to conducting a small-scale version of a study as a strategic prelude to conducting the larger study (Polit, Beck, & Hungler, 2001). This can mean structuring and conducting an exploratory pilot study that generates a next set of questions for a fuller study. It can also mean conducting a small-scale version of a study that will employ the same questions but with a refined research design that is rescoped based on data from the pilot study.

Piloting is a powerful tool for data-based design improvements. These improvements can include “develop[ing] an understanding of the concepts and theories held by the people you are studying—a potential source of theory” (Maxwell, 2013, p. 67). This development of theory through piloting is valuable since the data that emerge from pilot studies are based in participants’ language and meaning making and therefore provide a valuable source of understanding about the meanings and perspectives of those who are a part of your research (Maxwell, 2013).

Piloting can also serve to help us understand ourselves as researchers and our research techniques by helping us hone interview skills and work on modes of interpersonal engagement, including how we frame and approach our studies with participants (Marshall & Rossman, 2016). It is important to keep in mind that in qualitative research, the purpose of piloting is to refine the research design and methods, which includes instruments as well as research questions (Creswell, 2013; Morse, Barrett, Mayan, Olson, & Spiers, 2002). After conducting a pilot study and/or piloting instruments, certain aspects of the research design may change slightly or significantly. There are times when piloting results in a researcher or research team shifting away from a particular kind of study or topic altogether. This is an important strength of piloting that can ultimately save time and energy. The many important reasons for and values of conducting pilot studies are presented in Table 3.4.

Source: Adapted from van Teijlingen and Hundley (2001, p. 2). Retrieved from http://sru.soc.surrey.ac.uk/SRU35.pdf

We have seen the incredible benefits of piloting firsthand in our own research and that of our colleagues and students. Piloting cannot ensure the success of a qualitative study, but it surely contributes to its rigor and the quality of data, among other benefits. It is important to note, though, that piloting must be conducted thoughtfully and with attention to the rigor of the piloting process itself. Piloting should be conducted in thoughtful, intentional, and careful ways to make it reliable and useful (Sampson, 2004; Kim, 2011; van Teijlingen, 2002; van Teijlingen & Hundley, 2001). Furthermore, it must be documented with great care and detail in order to be useful as you move forward in your research. As you conduct the full study, you will include information about how you structured your piloting processes as a way to discuss the study design and validity.

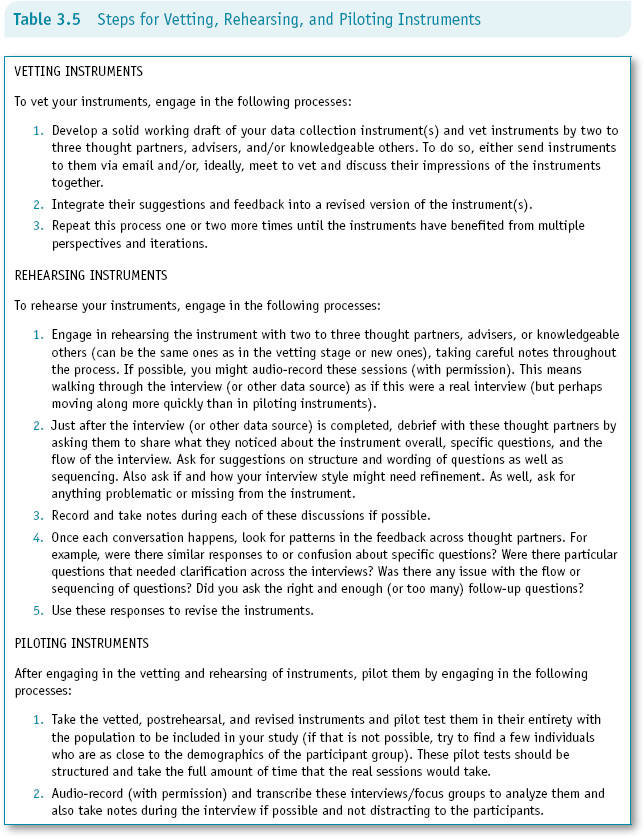

In terms of the use of piloting as it refers to data collection instruments, we want to note that we differentiate between piloting instruments, vetting instruments, and rehearsing instruments, although these are related processes that build on each other. In the next subsections, we discuss vetting, rehearsing, and piloting instruments so that you can appreciate the differences, uses, connections, and values of each process. Ideally, you will engage in all three aspects of developing and refining your instruments since together they promote the rigor and validity of your study.

Vetting Instruments

Vetting instruments entails sharing multiple drafts of your data collection instruments with knowledgeable others who can give you critical feedback. These knowledgeable others can include classmates, peers, mentors, colleagues, experts in the field, scholars, community members, potential participants, and so on. This as an iterative process wherein a first draft would be shared with multiple readers (approximately two to three) and revised based on the careful integration of feedback, and then a second (and perhaps even third) draft is shared with these thought partners again until the instruments have been fully challenged, discussed, and improved upon based directly on this focused feedback. We do this ourselves, and we require this of our students because having your instruments vetted and discussed in relation to the goals of your study and fit with your research questions, as well as having them challenged and revised systematically, is incredibly valuable to you as a researcher. It can help uncover that which is missing or problematic, underlying assumptions and biases, issues with clarity, wording, flow, scope, and so on. Harkening back to Emerson et al.’s (1995) notion of the “inseparably of methods and findings,” the quality of your data collection instruments has everything to do with the validity of your study and the quality of your data and therefore directly shapes what you are able to do with your data in your analysis and writing.

Rehearsing Instruments

Rehearsing instruments, which we view as quite valuable, is a different process from piloting instruments in at least two major ways. First, rehearsing your instrument(s) involves rehearsing (practicing and testing out) an instrument with a friend or colleague—rather than the target population—to check for flow and clarity of wording, sequencing and content of questions, and relationship of the number of questions to your ability to include follow-up questions and probes for individual meaning and terminology. Rehearsing instruments means that you engage in a mock interview so that you can rehearse the instrument and practice your interviewing style as it relates to the specific study and set of questions; it helps you to become more comfortable with the interview questions and process in a way that cannot happen until you try out the instrument in real time with real people who can react, question, and give feedback during and after the rehearsal. The fact that the person you are rehearsing the instruments(s) with is not analogous to the population of your study is a major difference in the process and has implications for the degree to which you will adjust your instrument(s) since you must remain aware that this population is different than the real intended participants. The second major difference between rehearsing and piloting instruments is that rehearsing an instrument means practicing your instrument (i.e., conducting a mock interview) but does not include collecting and analyzing data from that process. What we advise our students to do is to take notes, have the people you are interviewing take brief notes if possible, and then discuss the interview instrument and process once the rehearsal is over (you can also audio-record these to listen to later, but you need not transcribe them). When you do this in multiple rounds with different people, you are able to begin to see patterns in the interview experience and interviewees’ feedback. Rehearsing instruments multiple times also means that you become increasingly comfortable with the instrument itself as well as with the opening remarks in which you discuss, with participants, the informed consent process, the structure and timing of the interviews, confidentiality, and the voluntary nature of the interview.

Piloting Instruments

When you formally engage in piloting instruments, you use your instruments with individuals who meet the sampling criteria for your study and collect and then analyze the piloted data. For example, when piloting an interview, the goal is to refine your instrument. Thus, you need to audio-record (with permission) and transcribe that interview and analyze the data in order to refine your instrument. To be clear, piloting instruments creates data that are used to drive data-based changes to your study. These data may or may not be used as a part of the formal data set depending on how significantly you change or revise the instruments as a result of piloting them.

When piloting interviews, for example, you engage in full-length interviews and approach all aspects of the interview as you would in a postpilot interview. As you collect and analyze the data from these interviews, the goal is to examine the data in relation to your research questions to see if you are getting the kinds of data you need to be able to answer your research questions. This may require, if possible, multiple pilot interviews to have as much data as possible. As you analyze the pilot interview data, the goal is to look for patterns in the responses. For example, you might ask the following:

- Were there similar responses to or confusion about specific questions?

- Were there particular questions that needed clarification across the pilot interviews?

- Was there any issue with the flow or sequencing of questions?

- Did you ask the right and enough (or too many) follow-up questions?

- What else emerges as you look across participant responses?

These analyses, as well as the content analyses of the responses themselves, will suggest any additional changes, revisions, additions, or deletions of interview questions you may need to make.

One important note across these three methods of instrument development and refinement is that you should carefully document how you structured and approached these processes. You should include in-depth descriptions of the specific techniques you used in your research design section that include enough detail on the actual processes as well as a focused discussion of how they influenced specific changes and revisions to your instruments and possibly other aspects of your research design. In Table 3.5, we provide a broad overview of the instrument development process, including vetting, rehearsing, and piloting processes.

The instrument piloting process, which includes vetting and rehearsing your instruments, is vital for achieving rigor and for the validity of your study. Again, we encourage our students to be sure to document (in memos and/or a research journal) the various kinds of piloting they engage in and how, specifically, it shaped or changed their instruments and broader research design.

Writing

Writing is an integral part of the research design process. Writing highlights and helps you to make sense of the iterative and recursive nature of qualitative research. We strongly believe that various forms of research writing—including memo writing, drafts of research questions and overview designs, research journal entries, fieldnotes, informed consent forms—throughout the research design and overall research process are generative and vital to reflexive research. We specifically discuss the role and structure of formal writing in qualitative research, including the final research report, in Chapter Nine, and we discuss the writing practices and approaches involved in writing a research proposal in Chapter Ten.

Note: We focused on interviews here, but this can apply to focus group instruments as well. While observation instruments may not be rehearsed, they can be vetted as well as used in pilot studies. Pilot testing questionnaires requires that you have people fill out the questionnaires either on paper or online as they would in the real context and with the same directions as the actual questionnaire. You then examine responses and ask respondents for feedback on structure, flow, content, directions, and so on.

Recommended Practices 3.13 and 3.14 are additional ways for you to engage in research design through structured writing activities in the form of memos to help you refine, develop, and justify your emerging research designs. Example 3.3 is one example of how the research design memos described in Recommended Practice 3.13 can be structured. In addition to the dialogic engagement activities described above such as structured sets of conversations (Recommended Practice 3.2) and paired question and reflection exercise (Recommended Practice 3.3), we describe a group inquiry process in Recommended Practice 3.15 that can be generative to the writing process. Sharing your writing with peers and colleagues in both formal and informal ways is important to the overall research design process as well as to the specific written products themselves.

Recommended Practice 3.13: Critical Research Design Memo

The goal of this memo is to systematically reflect on your emerging research topic and research questions (and the goals and concepts that shape them) and relate these to the plan for your data collection methods and processes. An important aspect of this memo is to pay attention to the ways that your research engages criticality in its approach to understanding context, including the impact of macro-sociopolitics on the setting and participants, as well as to setting up a research design that seeks this and other kinds of complexity and contextualization through a rigorous process of reflexive engagement and methods consideration. (Example 3.3 demonstrates how a critical research design memo could be structured.)

Topics to consider exploring in a critical research design memo include the following:

- Iterated research questions

- How/if the questions have changed and why

- Describe the goals of refined research questions and how they differ from the earlier questions

- Site selection criteria and rationale questions/concerns/ideas

- Participant selection criteria and rationale questions/concerns/ideas

- Synopsis of intended methods

- How/if these have changed and why

- Goals of each method and rationale for each method

Recommended Practice 3.14: The “Two-Pager” Research Design Memo