Chapter Four Design and Reflexivity in Data Collection

Chapter Overview and Goals

The focus of this chapter and the next is on the considerations, processes, and techniques of qualitative data collection. We approach data collection from an ecological and holistic perspective that seeks rigor, validity, and criticality. Research participants are and should be seen as “experts of their own experiences” with much to teach us about their lives and experiences, and it is essential that you view their stories as contextualized and embedded in larger phenomena, experiences, and realities (Jacoby & Gonzales, 1991; van Manen, 1990). A primary goal of this chapter is to help you understand that your study will be driven by your research questions, goals, and participants in unique and customized ways that may need to be adjusted over time in light of fieldwork constraints and possibilities as well as emergent learnings from the data and entire research process. It can be daunting for a novice researcher to think about departing from a set research design, and that is why we stress the crucial roles of dialogic engagement and structured reflexivity throughout this book. In addition to describing qualitative data collection, this chapter provides concrete explanations and specific strategies to help systematize reflection and dialogue into what could otherwise be a daunting process. In the chapter that follows, we detail qualitative data collection methods and techniques.

This chapter begins by defining qualitative data collection as a series of connected processes and highlights the integral role that research design plays in these processes. We then discuss the role of reflexivity in data collection and describe how these reflexive processes also function as data; we term these data researcher-generated data. We close by discussing the design-related aspects of qualitative sampling approaches, including considerations for selecting research sites and participants.

By the end of this chapter you will better understand

- How data collection is an iterative and recursive process

- The relationship between data collection and the other processes of qualitative research

- What it means that data are co-constructed rather than just collected

- The role of reflexivity in data collection

- The roles, processes, and steps for collecting researcher-generated data, including memos, research journals, research logs, contact summary forms, and researcher interviews

- Qualitative sampling procedures, including selecting the site and participant group for your study

Defining Qualitative Data Collection as Iterative

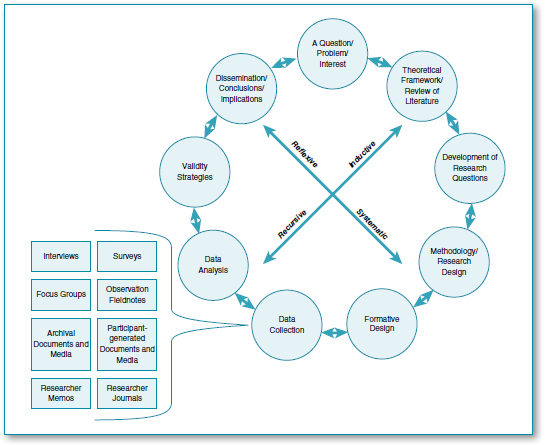

Qualitative researchers should take an iterative (rather than chronological or linear) approach to data collection. This means that data collection is cyclical, emergent, and recursive—methods build upon, and are situated in relation to, each other in terms of sequencing, the nature of the data sought, and the ways that the methods will potentially support the development of each other and the data set as a whole. Figure 4.1 builds on Figure 1.1 and depicts how data collection methods are connected to all of the dynamic aspects of qualitative research.

The multidirectional arrows signify that qualitative data collection is not a linear process, but rather, it is a recursive and iterative one that is inductive—with processes that build upon and influence each other in real time as research unfolds both theoretically and empirically—and therefore that the research is emergent in response to the learning that happens throughout the research process and especially during data collection (sometimes referred to as fieldwork, which is defined in Chapter Three). Viewing and approaching data collection in this more dynamic way helps you to seek complexity through intentional and strategic data collection. In this chapter and the next, we discuss data collection in a way that reflects this intentional and recursive approach.

In addition to defining data collection as a series of related, iterative processes, we want to underscore that the idea of data collection is slightly misleading. In a qualitative study, you are not merely “collecting” data. You are interacting with other individuals, and you, as the researcher and primary instrument of the study, directly impact and affect the data you “collect” (Lofland, Snow, Anderson, & Lofland, 2006; Porter, 2010). In this regard, data are generated and co-constructed rather than simply collected (Roulston, 2014). For the sake of clarity and given the terminology used widely in the field, we refer to these processes as data collection. However, recognizing that you are not simply collecting data in a unilateral way is important to conducting ethical and complex qualitative research as well as an important part of more critically approaching qualitative research.

Terms and Concepts Often Used in Qualitative Research

Data set: A data set refers to the data that have been compiled and organized to answer your research questions. This may include, for example, data from interviews, archival documents, and/or focus groups. The data in a data set have been organized and pulled from your entire corpus of data, which can include all of your data sources such as archival data/documents and artifacts; interview data; focus group data; observation and fieldnote data; survey and questionnaire data; emails and other online data; participant-generated data such as journals, reflective writing, professional documents, photos, videos, and other digital media; and any other forms of existing data.

Terms and Concepts Often Used in Qualitative Research

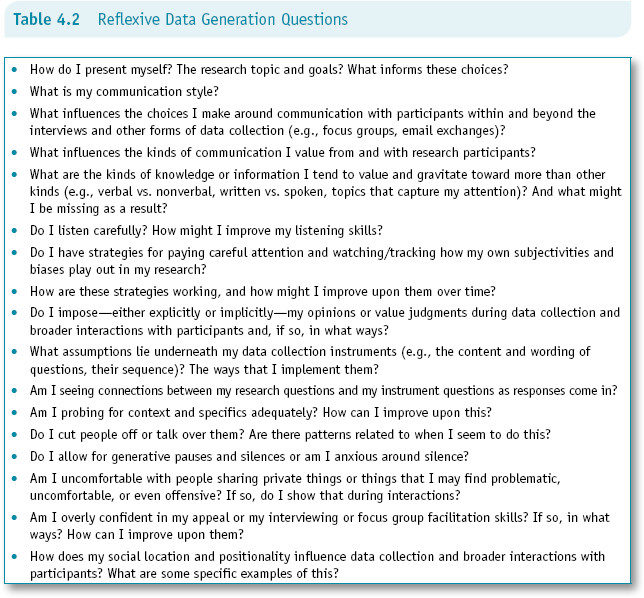

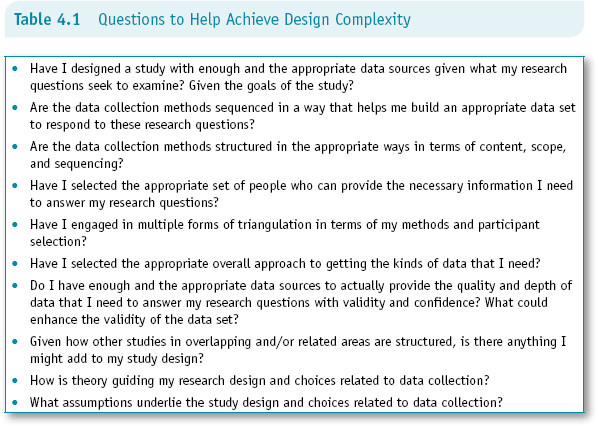

Design complexity: Design complexity refers to the ways that you strategically plan, design, and structure your research processes so that you can answer your research question(s) in the most complex, rigorous, and nuanced ways possible. Design complexity necessitates data triangulation and the strategic sequencing of methods as well as adopting a reflexive approach to design and data collection, which we describe throughout the book and especially in this chapter. To think about achieving design complexity, see the questions described in Table 4.1 and the questions in Table 4.2, which help you to think about reflexivity in data collection.

Data Collection and Research Design

As described in Chapters One and Three, when we think about engaging criticality in qualitative research by seeking complexity as a form of validity and accounting for micro and macro concerns about equity and representation, we think immediately of what we call design complexity. In this chapter and the next, we focus on the aspects of research design specific to the data collection process of a study or what we refer to as the data collection plan. This is the plan for the actual methods of data collection that will be employed in a study and their scope, timing, and sequencing. To achieve design complexity, you should consider a number of probing questions about data collection, which are described in Table 4.1.

Design complexity guides the overall data collection process and sets up the data collection methods to be as useful, appropriate to the study, and generative as possible. Revisiting the questions in Table 4.1 as you develop your data collection plan as well as begin collecting data will help you to think about issues related to collecting complex and rich data. In the next section, we discuss specific ways that qualitative researchers can strive for complexity through reflexivity and researcher-generated data sources.

Reflexivity and Researcher-Generated Data Sources

The research design does not matter unless you, as the researcher, approach the data collection process with the understanding that people are experts of their own experiences. The most well-planned and elegant research design will not be able to capture the complexity needed for qualitative research to be valid, ethical, and rigorous unless you accept the responsibility of the power you have as the researcher and mitigate that by cultivating and working from an inquiry stance that helps you to remain as authentic as possible to participants’ experiences. Ensuring that the study methods are carried out in ways that support valid and generative data collection is in large part about your consciousness and approach as a researcher, your skills as a researcher in terms of how you engage with people, and honing those skills through a systematic process of examining yourself as the primary instrument of your research. The reflexive data generation process includes asking a series of questions, which we call reflexive data generation questions and detail in Table 4.2, about yourself as a researcher and your impact on the data and study overall. These are the kinds of questions that every researcher needs to ask throughout each stage of the research process. These questions are about you, the researcher as instrument, and paying close and systematic attention to them is important to maintaining fidelity to exploring and trying to understand the complexity of people’s experiences.

In addition to these questions, a data collection plan that builds on thoughtful reflexivity and seeks design complexity is also supported by a number of the researcher-generated data collection methods that we describe. Reflexivity must be more robust and rigorous than occasional self-reflection; it can also be tracked and examined as a form of data in its own right. We refer to these kinds of reflexivity exercises as researcher-generated data, which are data that the researcher generates as part of the reflective process of engaging in fieldwork. In the subsequent sections, we detail data that are generated by the researcher, including memos, research journals, research logs, contact summary forms, and researcher interviews.

Fieldwork and Data Collection Memos

Memos may include, among other things, your observations and reflections about various aspects of your study, including interactions with participants, data collection instruments, your skills as a researcher, and ways that you think you are influencing the data. Fieldwork and data collection memos have a variety of purposes, including making note of and considering important occurrences and key events (sometimes called critical incident memos—see Appendix G for an example of a critical incident memo), discussing decisions you need to make, and/or documenting how your research is shifting, changing, and developing over time. Memos composed throughout the study can also be used as data. In addition to serving as data points, data collection memos serve as connective tissue for data collection and analysis processes as well as between researchers’ fieldwork reflections, ongoing data interpretations, and emergent analyses that inform future fieldwork (Nakkula & Ravitch, 1998; Ravitch & Riggan, 2012).

Fieldwork and data collection memos should be a regular and systematic aspect of the research process. A researcher or research team should engage in memo writing throughout any given study to chronicle fieldwork and data collection issues as well as to focus on emerging themes in the data. Data collection memos can be used to refine methods and to capture meaning making in process as researchers make sense of fieldwork and all incoming data (Emerson, Fretz, & Shaw, 2011; Maxwell, 2013). These memos should also include careful documentation of the following:

- Broad fieldwork and specific data collection reflections

- Researchers’ experiences and interpretations as systematic “check-ins” about where each and all researchers stand in relation to the data and process

- General impressions about the space, environment, and the participants (looking across fieldnotes, contact summary forms, and/or notes on instruments)

- Researcher reflections on researcher social location and positionality and their impact on data collection

Since we view memos as a vital source of reflexivity and discovery, discussion of them is found in almost every chapter of this book. We describe two specific data collection memos in this chapter and redirect your attention to the memos described in Chapters Two and Three. We specifically recommend revisiting the Researcher Identity/Positionality Memo (Recommended Practice 3.1). This memo can be revisited and rewritten many times throughout any given research project and can be shared with critical friends and/or research teams as a way to push for critical dialogue around identity and positionality. Recommended Practice 4.1 is a fieldwork and data collection memo, and Example 4.1 is an example of a fieldwork and data collection memo written by Susan Feibelman during her dissertation process. In addition, see Appendixes G and H for additional memos that demonstrate the different structures researcher-generated data collection memos can take as well as the different roles they can serve. Just as a reminder, while memos are used for researcher sense-making, they can be shared with advisers and thought partners and can be excerpted in final reports.

In the above memo, you can see that Susan is making sense of her fieldwork and the data collection process itself in ways that are both reflective and formative to her study. This process of reflecting on the data collection process and the early data itself enhanced her thinking about the research and emerging data. It was also used to engage with her dissertation chair in discussing preliminary adjustments to the data collection plan. Engaging in the memos we recommend, or others like them, helps our students (and us) to chart our emerging understandings of the issues and realities at play in our fieldwork, our processes of data collection, and the role and processes of observation and fieldnotes for each new study and even new phases of existing studies.

Recommended Practice 4.1: Fieldwork and Data Collection Memos

The intention of fieldwork and data collection memos is for you to reflect, at various stages throughout your research, on your research project and the process of fieldwork broadly and data collection specifically over time. You might, for example, use a fieldwork memo as a place to record, reflect upon, and work through questions you have about your research process and/or changes you have had to make in your research design as a result of contextual realities or resource constraints. You might use data collection memos to note specific questions, concerns, and learnings about the data collection methods and the emerging data in real time to examine the relationship between the methods and the data, consider methods changes, and examine incoming data in ways that can guide formative changes in the data collection methods.

Consider writing these memos not only as a way to commit to reflection through writing for yourself but also as a way to engage with others who can read the memos, ask questions, and share concerns and advice. Students working on research reports, master’s theses, or dissertations also use these as a way to ask their advisers to help them think through and strategize emergent issues during fieldwork.

Potential considerations, topics, and questions:

- General or specific reflections about fieldwork experiences, including interactions with participants, observations about the site and participants, the ways that expectations are set and maintained or revised, and so on.

- General or specific reflections and thoughts about data collection methods and processes.

- How/if the data being generated answer the guiding research questions. Include excerpts of data and discuss these.

- How do your data collection methods and processes support design complexity?

- What changes may need to be made to data collection instruments, methods, and/or techniques to better answer the guiding research questions. Justify any changes with evidence from the data.

- Exploring and reflecting upon the data collection process. How, if at all, does your timeline need to be adjusted? How, if at all, has your research design changed?

- Your impressions about the space, environment, and/or the participants. How have these impressions changed over time? Pull in excerpts of data from across your fieldnotes, contact summary forms, and/or notes on protocols to help explore and explain your impressions.

- Describe your identity and/or positionality, its impact on the data, and how this may have changed over time.

Example 4.1: Fieldwork/Data Collection Memo

Susan Feibelman

April 13, 2011

Research Questions

- How are women mentored to take up leadership roles in independent schools?

- What networks of support exist to advance the development of women who are interested in pursuing leadership roles in independent schools?

- Do female educators who are interested in taking up leadership roles in independent schools seek out mentoring relationships and/or networks of support?

- How do the social identifiers of race and age inform the mentoring experience of aspiring women leaders in independent schools?

Vignette

Over a four-and-a-half week period in the spring of 2011 for my pilot study that is examining the ways in which women are encouraged to take on leadership roles in independent school settings, I completed structured interviews with seven women who are senior-level administrators in schools affiliated with the New York State Association of Independent Schools. Four of the study’s participants are women of color, and three are White women. Each of the women has been a teacher and school leader in one or more independent schools prior to stepping into her current position. One woman is an assistant head of school and one is an assistant head of school and upper school head, three women are upper school division heads, one is a middle school division head, and one is a lower school division head. For three of the participants, this is their first year in their current position, while the others have been in their present role for 3 or more years.

Prior to beginning these interviews, I attended the National Association of Independent School’s annual conference in Washington, D.C., where I participated in two conference sessions that addressed the role of women leaders in independent schools—“Women in Leadership: Risks and Rewards” and “Women Leading in the 21st Century.” Both sessions attracted a nearly women-only audience, although the conference itself appeared to have at least an equal number of men and women participants. While neither session offered more than a superficial examination of the gendered nature of independent school leadership, as I turned around and watched women from the audience ask questions or make comments, I was struck by the emotions that swept across their faces. This was an exceptionally stunning observation. One, because I often have the sense that if I start to tell my own leadership stories, my face will reveal feelings of vulnerability that I work doggedly to hide. So I will stop myself from talking openly about my experiences, through an internal dialogue that says, “Oh no! Don’t go there, you can’t be that person in this conversation.” Yet it was this same vulnerable affect that would appear again and again in my interview with accomplished school leaders. In the midst of a one-on-one conversation, almost from out of nowhere, an emotional vulnerability would wash across the speaker’s face as she told a particular story. It was with this awareness I approached my interview with Ginger Truslow.

Ginger, a White woman in her early 40s, is the assistant head of school/upper school division head of a kindergarten through Grade 12 independent girls school of approximately 500 students on the Upper Eastside. Before stepping into the school’s foyer, I crossed the street, walking past an art museum and into a tony neighborhood “specialty foods” store to buy a cup of coffee. This side trip offered me a chance to orient to the surroundings of this affluent New York City enclave before stepping into the school.

Upon entering the school’s formal lobby, I signed in with the “hall master” who was seated behind a desk and dressed in a coat and tie. He promptly phoned Ginger to inform her of my arrival. The foyer was filled with younger girls who had finished their school day and were preparing to leave. A handful of stylishly dressed women waited in the lobby for a child and I took a seat across from the head of school’s office and waited for several minutes before Ginger arrived, a bit breathless from a meeting, and, as we ascended a monumental staircase, apologized that we had to take several flights of stairs to her office.

Ginger’s office is tucked away on the third floor, is small and cozy, with two comfortable chairs and sparse decorations beyond a collection of books on shelf above her desk. Over the next 50 minutes, we would fill the space with a lively dialogue about the ways in which women who are interested in pursuing leadership roles in independent school settings seek out mentors and forge networks of support.

I think that to me, the question is how and where we continue to create sort of these, if you will, sort of support groups or mentor groups for each other, where we can really trust and rely, we’re all in competition with each other on some levels, I mean the schools not us personally, but also where can we find within each other mentors, because most of the mentors I have talked about are people who I’ve worked with, and I think that has been tremendous. I think what’s also really informed my sense of leadership and mentorship is having moved through several different schools. I mean I’m not really interested in doing that anymore, but how we continue to find our own voice in our own schools, that perhaps is informed by our colleagues and our friends in other schools.

Where can we do that on a sort of fairly regular basis and where will that, where can we find an effective means and also an effective group with which to do that, where we can suspend judgment and sort of develop that level of trust? You knew I went out to dinner with, oh my god Jen from Calhoun, and her names gone right out of my head . . . from Berkeley Carol . . .

Interviewer: Suzanne.

Respondent: Suzanne, I’m so sorry, and Gail Allen . . . who, Gail and I, our paths have crossed in very odd ways over the years and it was just so nice to sit down together and talk about what was happening at school and to see where we sort of had some of the same challenges, but we have to move beyond that oh . . . you know the upper school faculty are like this or this is like this and this is like this, and like bring a problem to the table and challenge each other, or maybe get to the point where you talk about something where we feel like we failed miserably or we’re not being successful in communicating something.

I think that kind of collegiality is something that we as women in independent schools really have to nurture amongst ourselves.

I went to . . . NCGS has a joint program with Simmons College every other year, about leadership, and leadership in education and in some ways that was like that. You know you had to have all these surveys filled out from people you work with and then you’d get sort of all the answers and you’d look at them and you’d think wow I’m really lousy at this or I’m really good at this.

You know when you had to be with a partner you had never met before and talk about your results and I thought but there was something about it that was so easy. I think in some ways because we were so foreign to each other, the women I was partnered with were from Canada, I thought this is as safe as safe can be. You know but then we just developed this kinship . . . it’s about developing a kinship with one another, and I think in some ways that’s sort of what mentoring is.

Maybe that’s the combination of mentoring and friendship, is the idea of kinship. Through that whole process we really had to sit with each other and ask questions and challenge each other and open up to each other and it didn’t feel super touchy feely in a way that was kind of a turnoff but it felt very authentic in other ways but then that group was suspended I mean right, we finished our program and we all went away and we don’t talk to each other anymore. So where can we sort of create that network I think is one of the questions for me within the city, because I think that for all of us it would be tremendously helpful.

Interviewer: I agree.

Respondent: So I don’t know, I’ve done a lot of blabbing but. . . .

Interviewer: No it’s good, what’s really hard I realize in trying to learn how to do this work, of asking the question and then gathering thoughts from so many different people is . . . I hear patterns right, and I want to say yes other folk are saying that they get a lot out of peer mentoring and so how does one sustain that. If there, and I believe there is a gendered quality to leadership, men are much better at creating networks of support than women are according to the literature. Men are good at asking for what they need, and women are less agile, and that there is . . . I think there’s an emotional piece to it.

At NAIS this past February, there were two different sessions on women in leadership which were very different than what I have seen at NAIS before; there have been sessions about teaching girls, mentoring girls into leadership roles, but this was the first really looking at so how do you and I learn to be leaders, how do we learn to be better leaders.

So the audience was 99% female, so my take-away is it is a question that holds a meeting for women and not for men, so that’s interesting, right? If you really want to think about what is supporting diversity in independent schools involve, because it does involve gender as much as it involves race and ethnicity and culture and sexual orientation and I could keep going.

What really struck me is as I turned around and watched women who I knew and didn’t know, ask questions or make comments, there was an emotionality on faces that for me was stunning. One because I always like if I start talking about my own story, I feel vulnerable, that there’s a look I can feel happening on face that is like oh no don’t go there, let’s like . . . can’t be that person in this conversation.

So I really appreciate what you said about the rawness in the room that morning and to just tell you that.

Respondent: Absolutely, and I think how we make it okay for that, because I actually, you know I think that there is definitely a place at school and there should be place at our leadership table for emotion, and I think that includes allowing people to feel elated, defeated, angry, tearful, exacerbated . . . whatever, but that’s not how you conduct yourself professionally right, and I guess my question would be . . . why not? Like isn’t that part of being human? So what part of our humanity are we expected to check at the door, you know we always ask that question about kids who come to our schools, say particularly a child of color who comes from a poor household, and you always ask the question what in the world does that kid check at the door when she walks through this door . . . you know.

So you live in Brownsville and you come to 75th between Park and Madison every day, like are you kidding me. You know and what part of herself does she leave behind, but I think we should actually ask that question about everybody, and I do think there needs to be boundaries between your personal life . . . like I don’t want to hear about everyone’s personal problems and I don’t feel like work is a place to work out my personal issues . . . whatever they may be in the moment, but I do feel like you can’t so cleanly separate those two.

Who you are as a person . . . and I think this is something that I am keenly aware of and the need to work on, because I think that it’s something that I am often very good at hiding to great detriment to myself and those I work with, is who I am as a school person and who I am as a person, and I think you . . . I don’t know why, I haven’t come up with an answer but I’ve been asking this question now for years, and I don’t have an answer without a question, but I know that I have that tendency, and I actually don’t think that’s good, because you don’t . . . I’m not actually my best self when I’m that way. I’m not actually showing people what I intend to show them or who I intend to be, but why do we get stuck at that place?

Fieldwork Research Journal

It is a common practice for qualitative researchers to keep a research journal throughout the life span of a study. The research journal is a place to record your thoughts, questions, struggles, ideas, excitements, and experiences with the process of learning about and engaging in various aspects of research. The main purposes of the journal are to (a) help you develop good research habits related to actively engaging in researcher reflexivity; (b) provide a structured opportunity to develop and reflect on your questions and ideas about your research; (c) keep and reflect on valuable references and concepts, which you can incorporate into the research study (and future research); (d) reflect on your own thoughts and practices throughout different points in the research process; (e) formulate ideas for action or changes to your research approach; and (f) develop meaningful questions for discussions with peers, research team members, and advisers.

Journal entries are intended to provide you with an opportunity to engage in focused thinking about your perspective on concepts and experiences related to your research. Over time, these entries allow you to make deeper connections between current and past readings, ongoing self-reflection, your process of becoming a researcher, your evolving frameworks for thinking about issues (including major turning points in your own thinking), and your perspective on discussions with thought partners. The format for research journals tends to be informal; the goal is the quality of reflection. Length of entries can vary significantly. The research journal is an important data source in qualitative research and is a place, like memos, that can be messy and used for real-time sense-making. Different than memos, the journal is ongoing and flowing, and it can be viewed as a kind of phenomenological exploration into the research process itself (Nakkula & Ravitch, 1998). Of course, data entries can be shared with thought partners and advisers at any time, and this can be quite generative. They can also be excerpted, like memos, in final reports.

Research Log

In addition to a fieldwork research journal, we recommend that researchers keep track of any and all changes, additions, or modifications to the data collection plan and the overall research design, including data collection and analysis methods and processes in a research log. This includes changes to data collection instruments and the development of your analytical approach and methods. A research log is a way to chronicle and keep track of changes and revisions to your research methods and processes in one central location. The format of the research log can vary, and we suggest that it be kept as simple and straightforward as possible. For example, changes, revisions, and/or additions could be noted in a simple list with bullet points; dates should be included for each entry. The goal of the log is to have a central place where you keep track of research choices and processes to account for them and their impact on the research. This is important because of the connection between methods and findings (Emerson et al., 2011) and the way that the quality of the data collected also affects analysis and findings.

Contact Summary Forms

Contact summary forms can be a vital and synthesizing part of the data collection process. Contact summary forms are used to cull and synthesize data, including participants’ verbatim statements from interviews and focus groups (Miles, Huberman, & Saldana, 2014). These forms are designed to provide an efficient way to distill key aspects of your data and to manage data without losing key information. These documents can also provide opportunities for a researcher to chronicle reflections and insights that emerge during and just after each interview and focus group to make them available for further analysis for each individual researcher as well as a research team as a collective (Miles et al., 2014). Interviewers may wish to complete a contact summary form after conducting each interview and focus group or after a set of them is conducted (e.g., with a large number of interviews, you could choose to do them after every five interviews). These summarizing forms allow a researcher (or a research team) to note patterns, preliminary codes, potential issues, and so on within and across participants. They also provide researchers with field-based analysis as the data are collected, allowing a researcher or research team to more quickly get a sense of what is happening throughout the research process since these are shared and discussed over time. Miles et al. (2014) have excellent examples of contact summary forms, and we have included two of their templates in Appendixes I and J.

Researcher Interviews

At times it can be useful for you, as the researcher, to be interviewed at one or more stages of the research process. This can be a generative approach to the research process as it can elicit a meta-analysis that might otherwise be lost. There are no specific guidelines for this as these interviews can be process and/or topic specific, and they can be open-ended or semi-structured. The goal is to generate insight and reflection on the study topic and processes as well as to experience being interviewed, either using a protocol that resembles or is totally different from the ones used with your research participants. Our students often tell us that just the process of being interviewed itself is a helpful reminder of how important careful attention to the interview process is and how vulnerable you can feel while being interviewed. We recommend that these interviews are always audio-recorded and sometimes that they are transcribed for careful analysis. If these interviews are not transcribed, the recordings should be listened to so that mid-course adjustments to fieldwork strategies and methods can be cultivated. Researcher interviews can also be process oriented rather than topic specific, meaning that you could choose to be interviewed on how some aspect of the research process is going as it unfolds (or retrospectively at the end).

Sampling: Site and Participant Selection

Sampling refers to the decisions you make in relation to from where and from whom you will gather the data you need to answer your research questions (Maxwell, 2013). Sampling decisions tend to be related to the individuals you will include in your study, but you may also make sampling decisions related to “groups, events, places, and points in or periods of time” (Guest, Namey, & Mitchell, 2013, p. 41). To achieve an intentional, well-reasoned sampling strategy, you will need to carefully consider your research questions and whose points of view are needed to be able to gather the data necessary to respond to your research questions with integrity and the appropriate range of relevant perspectives. These considerations lead you to make choices about site (setting) and participant selection and become the basis of your sampling strategy.

In qualitative research, these decisions are sometimes referred to as sampling but often referred to as site and participant selection since they include the selection of both setting and participants. Because you cannot study everything, you need to clearly define and establish criteria for the choices you will make related to the site and participant selection. In the following sections, we provide issues for you to consider as you develop your approach to both site selection and then the selection of participants within the site(s) you choose.

Site Selection

There are many considerations in the process of selecting your research setting or what some refer to as the “fieldwork site.” To put it simply, research must happen somewhere, and that somewhere is important to consider directly in relation to the goals of your study and the research questions that guide it. This means that, as a researcher, you need to think carefully about why you are choosing or would choose a specific site or set of sites for your study’s topic and goals. Some aspects of this selection may be scholarly in nature (e.g., wanting to engage with specific scholarly communities or theorists), and some are pragmatic (e.g., access, relationships with insiders who can provide approval). Flick (2007, p. 31) states that your site selection and sampling process consists of several steps:

- Selecting a site (or type of site) that matches your research goals

- Identifying situations in this site that are relevant for your issue/topic

- Selecting concrete situations in which your issues can become visible

- Identifying other types of situations by which your issues/topics are influenced

Considering these issues of location as you conceive your overall research design can be an important stage of study development. We find, both in our own research and in the research of our colleagues and students, that site selection can be a focal aspect of refining your overall research design in the sense that as you are working to develop and refine your research questions, considering the location can help focus the inquiry since it brings to life how the goals of the study meet the place and people in which you envision carrying out the study. Likewise, the site selection is informed by the study goals. We recommend that decisions related to site selection be an active part of dialogic engagement exercises that help you refine your topic, goals, and ultimately your research questions and study design.

To explore if your study has multiple sites or a single site, as well as some of the criteria of site selection for a given study, you must consider asking a number of site selection questions:

- Is there one specific or necessary location for your study and why?

- Do you want or need to look across multiple sites to explore a phenomenon, experience, or set of perspectives? What is the argument for this given your study focus and goals?

- What are the benefits or challenges of particular settings?

- Has the location been overly studied? (Angrosino, 2007)

- Will your presence burden the local population? (Angrosino, 2007)

- Are there ways in which studying the same research questions in different contexts would help meet the research goals?

- Are there settings within the setting, and what do those look like? How can you approach this in terms of sampling?

These are only a sample of questions that you should ask as you decide on the site(s) of your study. In general, you need to include individuals or groups (and possibly subgroups) who can provide the specific information that your research questions seek to answer. Sometimes, these individuals or groups are site specific such as at a specific organization, institution, or community. Some studies involve multiple sites, and others are not bound to a particular site or research setting (e.g., interviewing self-employed design architects across urban regions). For some, the selection of site is predetermined as when a practitioner engages in research in her own setting or a community decides to engage in participatory research within its own boundaries or when you wish to do an ethnographic study in a specific setting (see Hammersley & Atkinson [2007] for more about selecting a research setting for ethnographic research and the many considerations that go along with this). For others, the site is selected to explore specific phenomena, and therefore there might be a range of settings that could meet the needs of the study. This in and of itself requires thought and conversation. As you develop your goals for a qualitative research study, site selection often happens in tandem with research question development and refinement.

Terms and Concepts Often Used in Qualitative Research

Purposeful sampling: Purposeful sampling, which is sometimes referred to as purposive sampling, is the primary sampling method employed in qualitative research. It entails that individuals are purposefully chosen to participate in a research study for specific reasons that stem from the core constructs and contexts of the research questions. These reasons can include that individuals may have had a certain experience, have knowledge about a phenomenon, live or work in a particular place, or some other specified reason related to your research questions.

Participant Selection

Before selecting the specific data collection methods for a study, you need to consider the people who should be included in the study’s participant group (note that we do not use the term subjects as we find this a quite problematic term given its meaning and the layers of power that the term reinscribes). The selection of the participant group requires a clear understanding of the goals of the research question(s) in relation to the context and populations at the center of the inquiry. In terms of the selection of participants, the primary questions to consider are the following:

- Whom do you need to include, and for what reasons and purposes do you include them, given the goals of the study, the specific research questions, and contexts that guide the study?

- Which individuals, types of individuals, and groups are particularly knowledgeable about that which I seek to learn in this study?

- Are there specific experiences, roles, perspectives, occupations, and/or sets of relationships that I seek to explore, and who can help me to explore those?

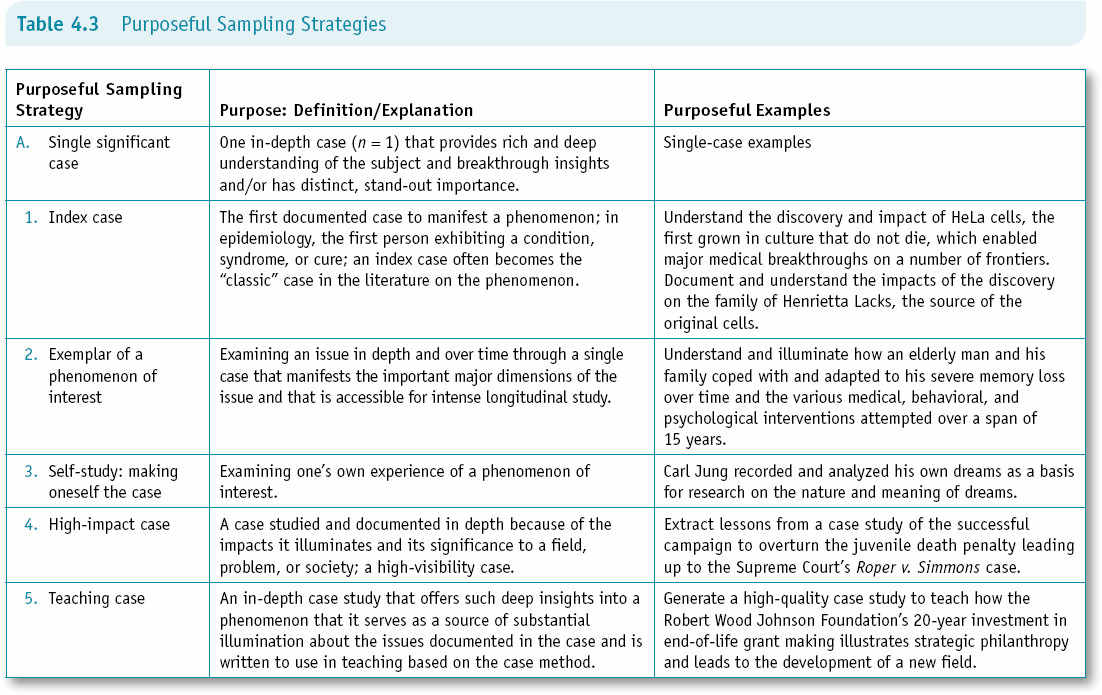

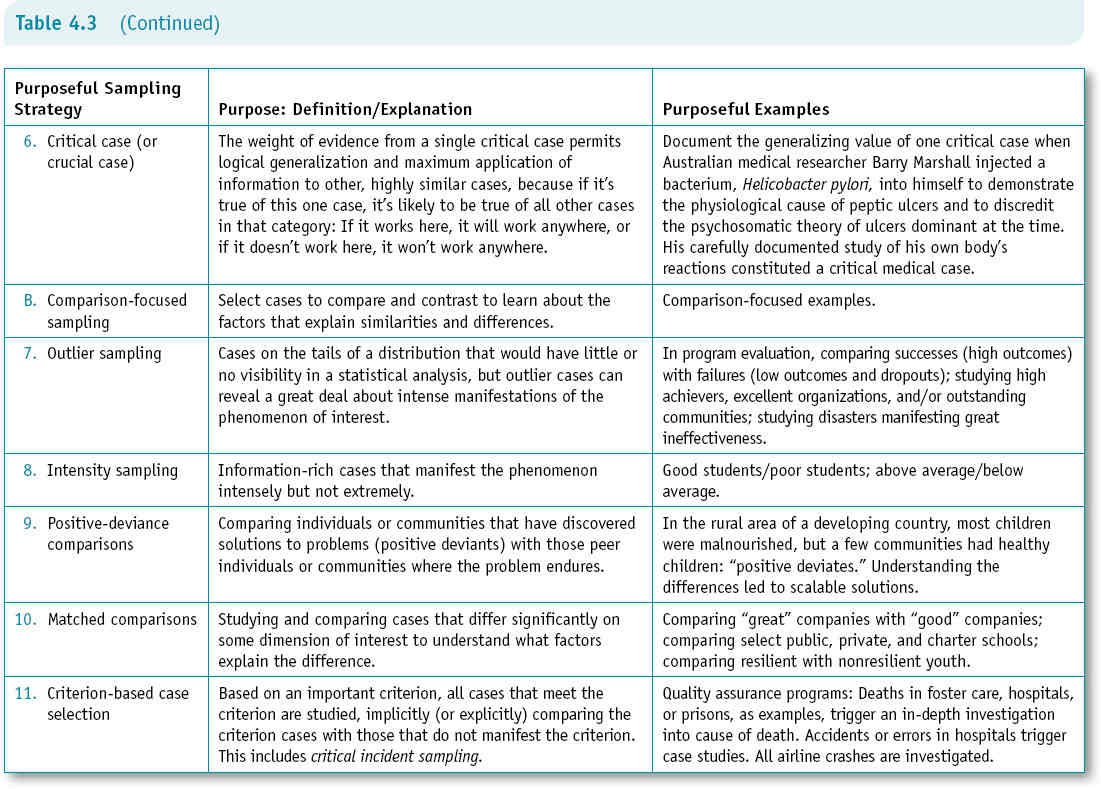

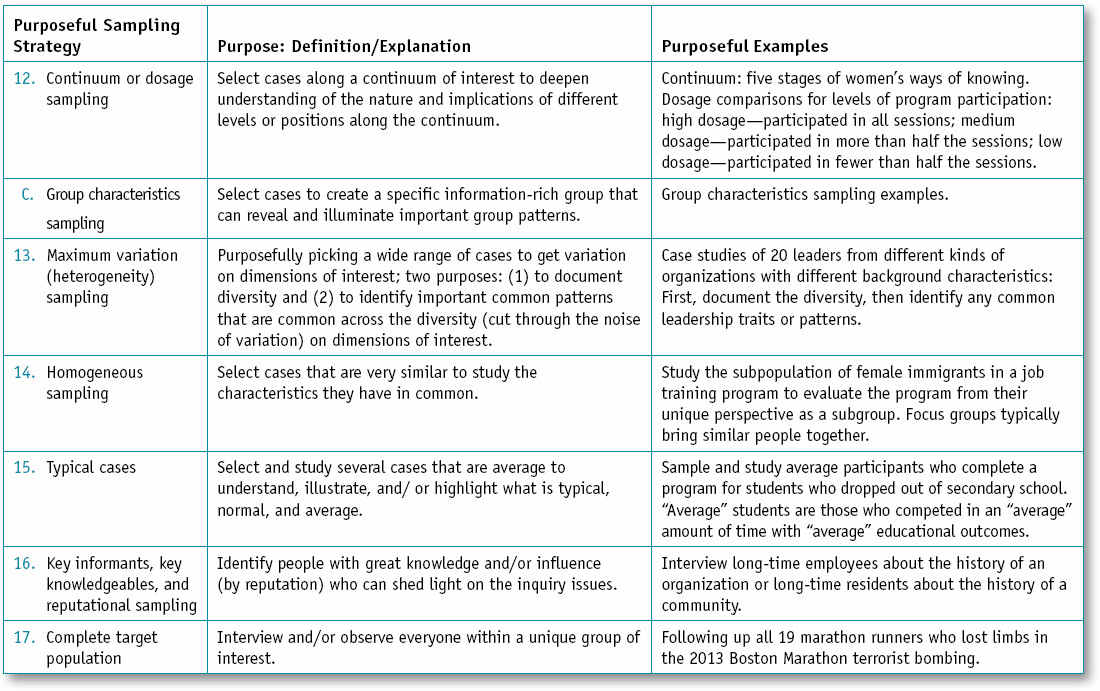

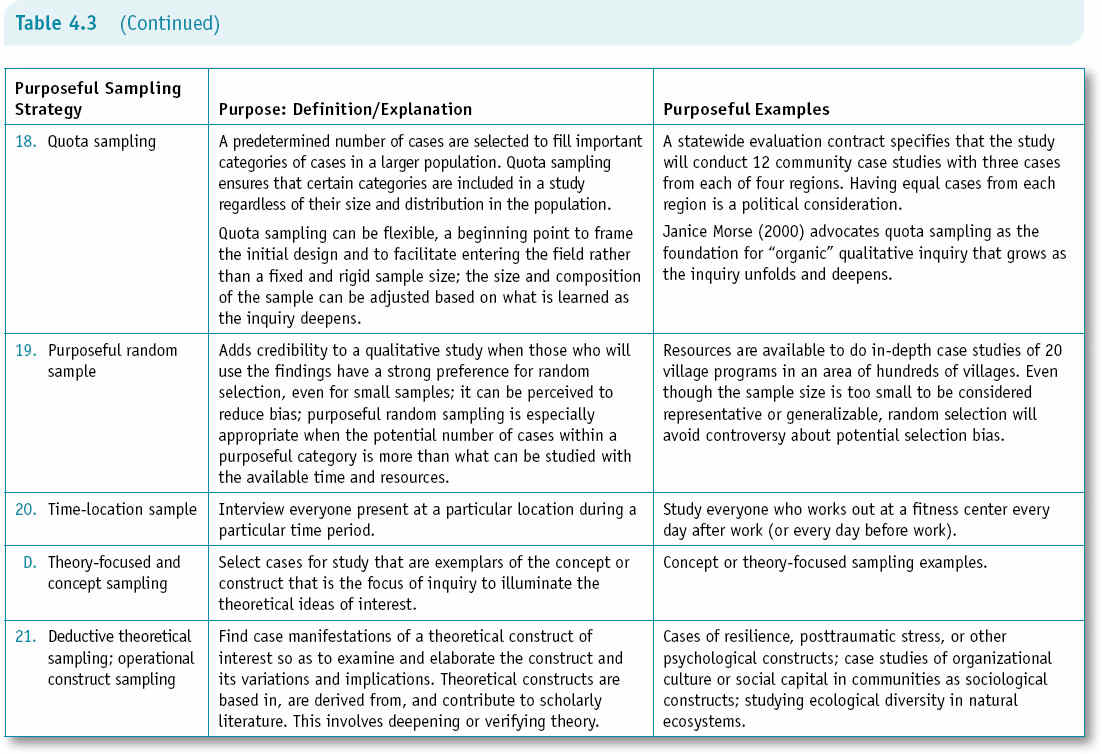

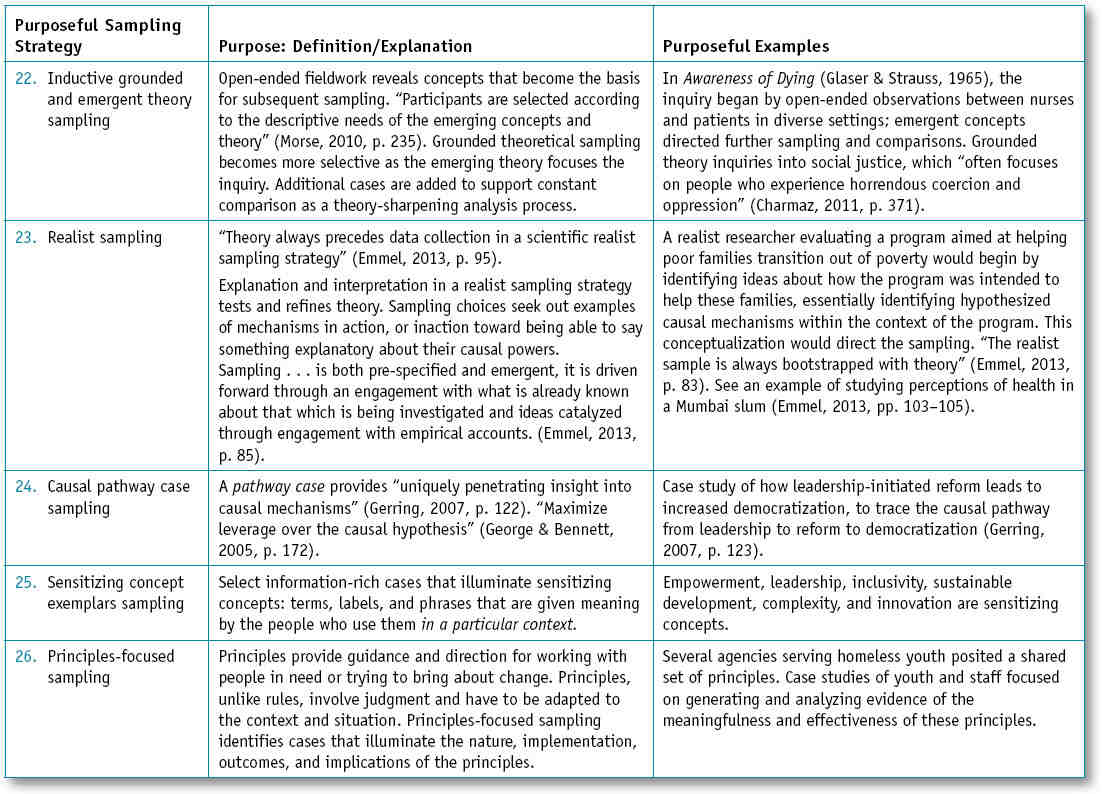

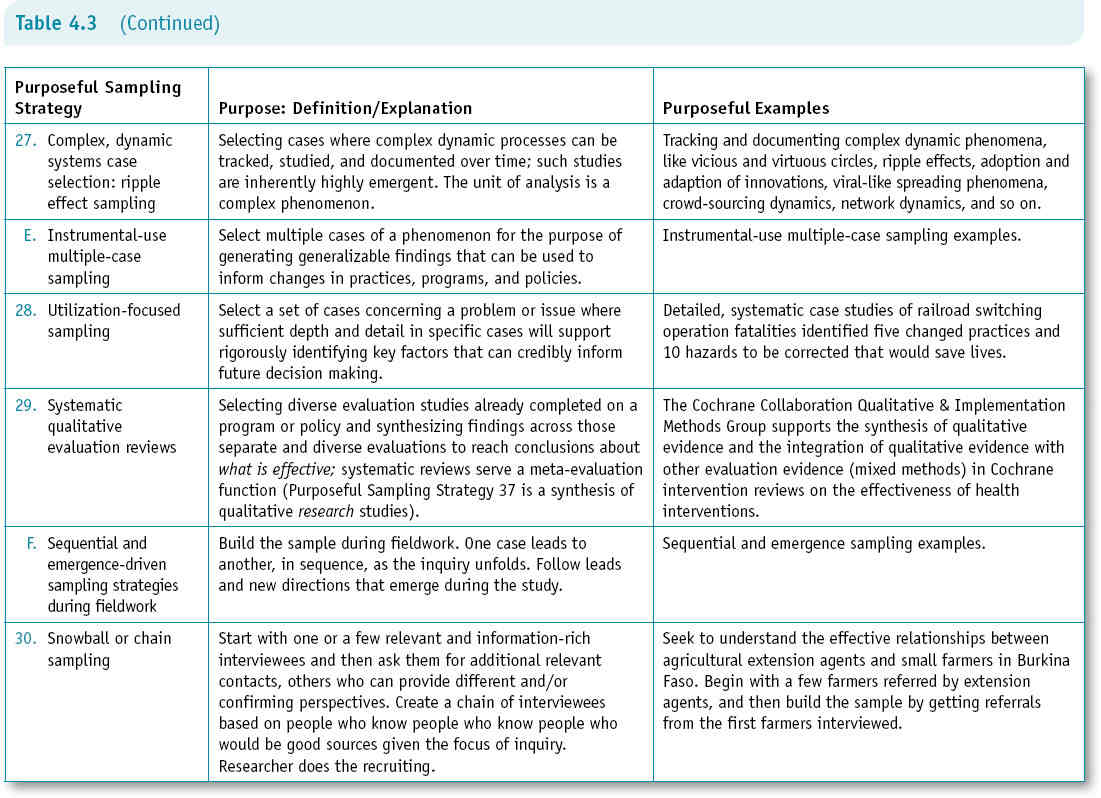

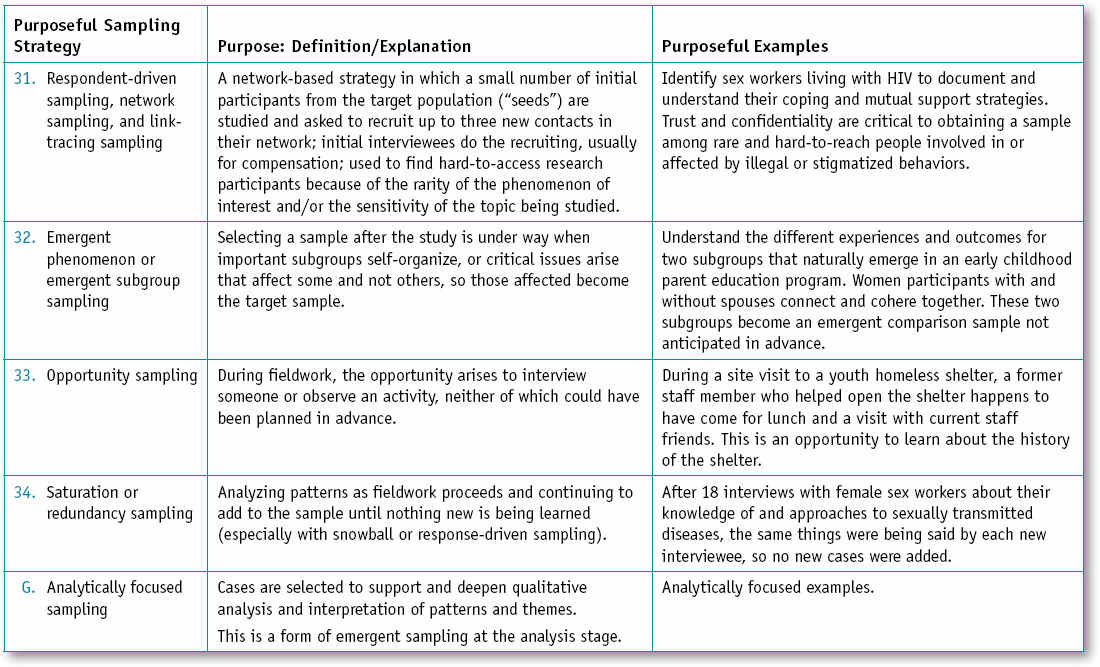

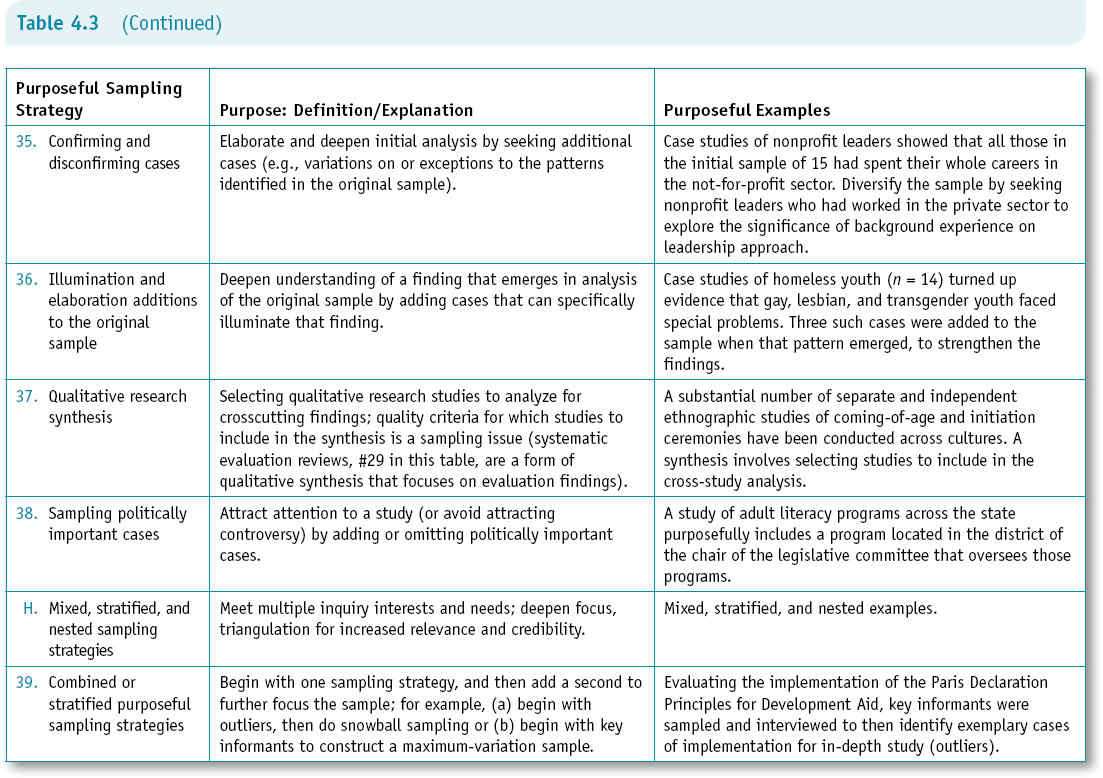

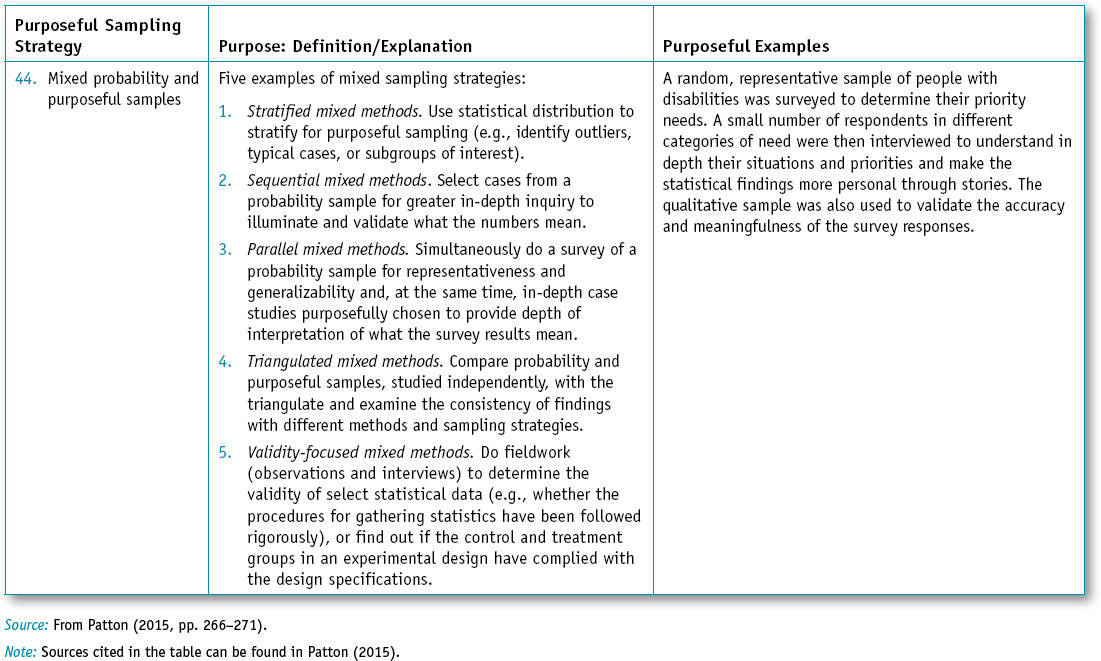

Some qualitative researchers critique using the term sampling in qualitative research as it stems from the goal of having a representative sample in quantitative research (Maxwell, 2013). Quantitative studies strive to employ what is called random probability sampling so that they can generalize their findings, which is not a goal of qualitative research. Instead, qualitative research, through purposeful sampling, provides context-rich and detailed accounts of specific populations and locations. Thus, random probability sampling is not frequently used. Rather, qualitative researchers tend to deliberately select individuals because of their unique ability to answer the study’s research questions. This is often called strategic, purposive, or purposeful sampling. Purposeful sampling means that individuals are purposefully chosen to participate in the research for specifics reasons, including that they have had a certain experience, have knowledge of a specific phenomenon, reside in a specific location, or some other reason. Purposeful sampling allows you to deliberately select individuals and/or research settings that will help you to get the information needed to answer your research questions. This is the primary sampling approach used in qualitative research (Coyne, 1997; Patton, 2015). Multiple strategies can be used to achieve purposeful sampling, as detailed by Patton (2015) in Table 4.3. In addition, see Patton (2015) and Miles et al. (2014) for further discussion of the different sampling techniques used in qualitative research.

Source: From Patton (2015, pp. 266–271).

Note: Sources cited in the table can be found in Patton (2015).

Inherent in decisions about site and participant selection is a discussion of your unit of analysis. Units of analysis can be focused on people, structure (e.g., projects, programs), perspectives (e.g., individuals who share a common experience), geography (e.g., cities, neighborhoods), activity, and/or time (Patton, 2015). Determining your unit of analysis is an important part of how you will select your participants (or sample). Another consideration related to participant selection is sample size. There are no set rules in qualitative research when it comes to having a certain number of participants: “Sample size depends on what you want to know, the purpose of the inquiry, what’s at stake, what will be useful, what will have credibility, and what can be done with available time and resources” (Patton, 2002, p. 244). It is not the goal of purposeful sampling and qualitative research to generalize; thus, the sample size becomes less important than in quantitative research. The goal is to rigorously, ethically, and thoroughly answer your research questions to achieve a complex and multiperspectival understanding. Despite not generalizing to the entire population, research from qualitative studies can help to make important decisions and suggest applications to a broader population. However, qualitative findings must be considered contextually. As with all design decisions, it is the role of the researcher to acknowledge limitations and potential weaknesses of the study, including sampling decisions such as size and strategies.

Regardless of the sampling strategies you employ, it is essential to have a clear, reasoned, and explicated rationale for why you selected individuals or groups to be a part of your study. The important thing to note is that these decisions require considerable thought, exploration, and planning in order to pursue sampling with intention and to achieve validity with regard to representation. Given the notion of “the inseparability of methods and findings” (Emerson et al., 1995), the choice of the participants is clearly a central aspect of how and what you can and will learn in your research. As discussed in Chapter Three, you need to consider local, contextual, and macro-sociopolitical factors in these selections with an attention to power and politics in both the specific environment and the broader society that shapes it.

Given the vital importance of your participant pool, it is essential that as a researcher, you spend considerable time exploring and discussing with others the various benefits and challenges in choosing the participants for your study. In addition to your own exploration and engagement in dialogue about these issues, you must make your decisions transparent so that readers of your work have enough information and context to determine if your decisions make sense and how they shape your analysis and findings.

We suggest that, among other strategies, you engage in multiple conversations with peers and mentors to get a critical perspective on issues of inclusion and representation in your participant group. We also suggest careful self-reflection on how you are viewing the possibilities of participants to push into your assumptions, biases, and blind spots. Among other approaches, writing a Site and Participant Selection Memo, as described in Recommended Practice 4.2, helps many researchers gain clarity on these choices and what influences them. Sharing such a memo with critical friends and advisers is often a vital step in this learning process since it invites critique and discussion about these issues of representation that are at the heart of qualitative research. Example 4.2 is a memo about site and participant selection written early on by one of our former students, Mustafa Abdul-Jabbar, during his dissertation process. See Appendix K for an additional example of a site and participant selection memo.

What Mustafa’s memo makes clear is that these choices—of site and participant selection—are ones that must be carefully considered and that require thought, reflection, and dialogue. Memos such as this one help you note and then consider issues at the heart of these choices. In addition, they create the basis for constructive conversations with peers and advisers about how to make these design choices. Finally, these memos help you to remember the choices you made throughout the research process since these often get forgotten over time. Researcher-generated data, such as memos, are an important way to record and preserve an understanding of the reasons for these structural aspects of your study.

Terms and Concepts Often Used in Qualitative Research

Unit of analysis: In qualitative research, your unit of analysis refers to the primary focus of your research study and is most often reflected in the core constructs in your research questions. The unit of analysis is the major entity that you are analyzing in your study. It is the “who” and/or the “what” at the center of your study. Units of analysis can be focused on people (e.g., individuals, groups), perspectives (e.g., individuals who share a common experience), structure (e.g., projects, programs), geographical units (e.g., city, neighborhood, state), artifacts (e.g., books, films, photos, newspapers), and/or social interactions (e.g., marriages, births) (Patton, 2015).

Recommended Practice 4.2: Site and Participant Selection Memo

The goal of this memo is to clearly define the criteria by which you will use (or used) to determine a specific setting and select the participants for a study. Also, in this memo, you should explain how the methods chosen in these realms align with the research questions and goals of the study.

Potential topics to discuss include the following:

- How the proposed methods map onto your research questions

- Site selection criteria (identify and challenge them, present a rationale for each criterion)

- Participant selection criteria (identify and challenge them, present a rationale for each criterion)

- Identification, justification, and limitations of/for all methodological choices

- Issues of/concerns about representation for site, participants, and researcher(s) in relation to the study topic, goals, and setting

- Your positionality/social location and its role in informing biases and assumptions for all or some of the above choices

Example 4.2: Site and Participant Selection Memo

Mustafa Abdul-Jabbar

December 23, 2012

Research Questions

- How do leadership practices of a distributed leadership (DL) team affect relational trust between members of that team?

- How is relational trust related to leadership team members’ perception of self-efficacy?

Archdiocese of Philadelphia

My current progress toward my dissertation proposal includes recent site and participation selection for research. I will begin this reflective memo in discussion around participant selection and then move on to discuss specific site selection(s). There have been two program implementations of distributed leadership and professional development training and support run by the Penn Center for Educational Leadership (PCEL). In the past year and a half that I have been volunteering at the Penn Center for Educational Leadership, I have spent that time vacillating between studying the older implementation of DL (i.e., Annenberg DL program with the Philadelphia school district) or the more current program implementation (i.e., Archdiocese of Philadelphia DL program). I have recently decided to conduct my research study within the context of the Archdiocesan implementation of DL.

Conception of the Distributed Leadership Program

As I stated in an earlier memo, the DL program was initially conceived to enhance effects of school leadership on student learning, through engaging classroom teachers to aid in instructional leadership processes, ensuring a wider distribution of leadership influence throughout a school (DeFlaminis, 2011, p. 1). The program intent was to carefully select (recruitment) teams of administrators and teacher-leaders, to develop their individual capacities for leadership (professional development), simultaneous with the design of action plans they collaboratively implement in their schools that was supported by ongoing mentorship (coaching), in order to improve institutional capacity and enhance student learning and achievement (CPRE, 2010, p. 4).

Unit of Analysis/Participant Selection

Based on the program structure articulated above, my unit of analysis will necessarily involve either the DL teams themselves (in their entirety) or select members of the DL teams. With 19 participating Archdiocese schools, each with four to eight members per team, I retain a swath of participant options. In further explication, after informal interview with John DeFlaminis— developer of the program structure and logic model—I observed that the program logic relies on utilizing teams within schools as vehicles for distributing leadership. Thus, I feel it is important to begin with the team itself as the unit of analysis because it is the program’s unit of implementation. To the extent the program is effective, it should be evident in the activity and interactivity of the team. At this juncture, the remaining challenge is to narrow my choices to specific team sites.

Program Evaluation

I am currently engaged in a program evaluation of the DL implementation with the Consortium for Policy Research in Education (CPRE). This involvement grew out of an independent study held with Professor Jon Supovitz during the fall 2012 semester and has continued through the spring 2013 semester. This project will go into the summer as well. My involvement with the evaluation has been beneficial because it provides a unique balcony view (Heifetz & Linksy, 2002) of the DL implementation assisting in meta-analysis and observation of the program itself and my role in the program. The evaluation work also allows me ready access to quantitative data (i.e., via surveys and program statistics) that I otherwise would not have had. It is within the context of the program evaluation that I have decided on the means for selecting specific research sites.

Site Selection

During the course of the CPRE program evaluation, part of the quantitative data analysis involved the creation of Likert-type scales for measuring such variables as relational trust, efficacy, perception of school issues, and so on. One of the variables measured by CPRE entailed the degree to which team members felt they had greater or lesser influence across a variety of dimensions of school leadership activity and practice. Because this particular measure was complementary to the DL framework as conceptualized by Spillane (2006, 2009; see also Spillane, Halverson, & Diamond, 2004) and further corroborated through informal interview with the program developer and director of its implementation, John DeFlaminis, I decided to obtain the list of sites that scored highest on the “Influence” scale.

On a scale of zero to four, only six school sites scored 3.5 or higher. Of the six schools, only one of the schools was a school that was affected by mergings/closings and thus will be left out of the research study because it is being reconstituted/closed by the Archdiocese. Fortunately, of the remaining five schools, I have already piloted one conference research project with one of the schools and am currently piloting another study this semester with a second school within the group of five.

Next Steps

I still need to decide if two school sites/teams are sufficient or perhaps three or even all five. Depending on my methodological choices for framing this research, I may indeed choose all five teams or participants across the five teams. For example, I am currently weighing the pros and cons of either a case study framework for conducting my research or a practitioner inquiry framework. Under a case study framework, I would have to work with fewer sites but would be able to capture more of an entire team’s activity and interaction. However, with a practitioner inquiry methodology, I could work with all five school sites (or at least four) and could conduct focus groups and other cross-site activities that could yield a very different research product. I confess that I’m still waiting until the end of this class, until we cover more on the benefits/challenges of case study methodology, before I make my decision. ☺

Questions for reflection

- How are data collection processes iterative and recursive?

- How is data collection related to the other processes of qualitative research?

- What does it mean that data are co-constructed rather than just collected?

- How is the researcher integral to data collection processes?

- What does reflexivity look like during data collection processes?

- What are the roles, processes, and steps for collecting researcher-generated data, including memos, research journals, research logs, contact summary forms, and researcher interviews?

- What key aspects should you consider when selecting the site and participant group for your study?

Resources for further reading

Sampling, Site, and Participant Selection

Angrosino, M. (2007). Doing ethnographic and observational research: The SAGE Qualitative Research Kit. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Flick, U. (2007). Designing qualitative research: The SAGE Qualitative Research Kit. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Guest, G., Namey, E. E., & Mitchell, M. L. (2013). Collecting qualitative data: A field manual for applied research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Memos and Research Journals

Emerson, R. M., Fretz, R. I., & Shaw, L. L. (2011). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Nakkula, M. J., & Ravitch, S. M. (1998). Matters of interpretation: Reciprocal transformation in therapeutic and developmental relationships with youth. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Online Resources

Sharpen your skills with SAGE edge

Visit edge.sagepub.com/ravitchandcarl for mobile-friendly chapter quizzes, eFlashcards, multimedia resources, SAGE journal articles, and more.