8.

IMMORTAL EGGS

And so we come—almost!—to the end. Eggs existed before you and me, and eggs will outlive us all. This thought is either comforting or terrifying, depending on the sort of day you’re having—and how acute your sense of mortality. In so many cultures, eggs were the very first things to exist. Ancient Greek Orphic tradition describes a cosmic egg that hatched the first hermaphroditic deity, from which all other gods came. In Egyptian mythology, the god Ra was hatched from an egg laid by a celestial bird. The universe began as an egg in the Chinese myth of Pangu, a god who was born from an egg in which he developed and slept for 18,000 years; when it split, the egg created the universe. The lighter elements drifted up to make the sky, and heavier, less pure elements settled to create the earth. A Finnish story has it that a yolk from an egg laid by a duck made the sun, and the white made the moon. And as eggs were at the beginning, eggs will be at the exciting end. After we’re all gone from this planet—that is, if we haven’t destroyed it completely—eggs will outlast and outlive us all.

A fresh egg is a very good thing (this page), because eggs begin to break down as soon as the egg leaves the hen: The last one in is a rotten egg, as we all know. (Eggs come to such smelly ends because hydrogen sulfide and other gases are produced by the bacterial breakdown of egg proteins.) But it turns out that fresher isn’t always better, and there is something very wonderful about old eggs, too, when properly preserved—pickled, fermented, alkaline-cured, dried, crystallized. They’re food for the apocalypse—nearly immortal—ready for travel to the ends of the earth, and beyond.

RIP us. Long live the egg!

The Century Egg

Tienlon Ho

There was a time when making pi dan was a specialty, as much as hand-pulling noodles, hammering into shape a well-balanced wok, or fermenting rich soy sauce. When my dad was a kid in southern China, there was a guy in the village whose trade was making pi dan and caring for the ducks that laid the eggs to make them. And, of course, he had learned how to do these things from his father before him.

Pi dan means roughly “leather-skinned egg” in Chinese, a name that describes how they were once most commonly made: Clay was applied to the shell of raw eggs (usually duck), which dried into a leathery coating. After a month or so, it transformed their insides into a gel of dark amber surrounding a creamy yolk of many shades of green.

In the West, pi dan are commonly known as thousand-year eggs, millennium eggs, or century eggs, which are all misnomers. Transformed, pi dan can last a few months without refrigeration—though, like most everything in the world, they do eventually shrivel up into smelly, brown goop.

The magic ingredient for making pi dan is not the clay but rice husks, or more precisely, rice husks burned into ash. Blended with water, they become a strongly alkaline concoction known as lime. Humans have found all sorts of ways to use alkalis in cooking—from the nixtamalization of corn into digestible masa to creating the golden crust on pretzels, curing olives, and giving ramen that pleasant bite. With enough time and enough concentration, alkalis also cure eggs.

The alkali was for millennia a product of the seasonal cycle of rice farming and the ducks that waddled around freely, tilling and weeding the rice paddies. Everything was in synchronicity. The first rice crop went in the ground just after the Chinese New Year and was harvested in early summer, just when the ducks were at their egg-laying peak. The piles of coarse rice husks and plant stalks left over from the harvest were burned into the ash that would be used to turn all those eggs into something pungent, delicious, and readily saved. In other parts of Asia where rice was not as abundant, alkaline substitutes like the yellow clay churned up by the rivers, termite mounds, and the dust spit out by volcanoes were used to make pi dan instead.

Each pi dan maker would mix his own proprietary blend of salt, tea, and ash (rice husks and pine, for instance) into the clay, then cover the duck eggs with it. The coating would slow evaporation through the porous shell while the alkalis and trace elements penetrated it, making the egg inhospitable to bacteria while breaking down proteins into smaller, tastier compounds, such as the glutamates responsible for imparting a meaty, umami flavor. The eggs would go into an earthenware vessel, or simply a dry hole in the ground, for around forty days in the summer, or fifty days in the winter (depending on the local climate), to undergo metamorphosis.

This technique resulted in a lot of flops. Sometimes the eggs would ripen only partly, while others would decompose. The mark of a quality pi dan is the appearance of song hua, frosty pine branch shapes on their glassy, amber surface, but these only form if proteins have denatured sufficiently and at just the right rate.

In Taiwan, chemists in the 1950s perfected a mass production method using a liquid brine, immersing the eggs in a solution of salt, lye, and lime for a couple weeks, followed by a few weeks of dry-aging in wax or plastic. Village pi dan makers were soon replaced by factories. In the beginning, some added lead oxide to the mix to keep the texture soft while ensuring song hua, but eventually they learned less worrisome zinc or magnesium salts did the trick. While pi dan makers have always tested for doneness by tapping each egg, feeling for just the right rebound and jiggle, a Taiwan university recently unveiled technology that tests eggs ten times faster in an acoustic chamber. There are always new ways to improve the process, it seems.

*

In Hong Kong, the narrow street of Wing Wo in the neighborhood of Sheung Wan is packed with herbalists, but even a couple years ago it was still known to locals as Pidan Street, where vendors sold their eggs stacked high on carts. In recent years, they were encouraged to pack up and move to a concrete wholesale market by the wharf, out of sight.

One of the last of the egg vendors still on the street is Shun Xing Xing, which serves customers promptly from 10:30 to 3:30 Monday through Saturday through a small window cut out of a corrugated steel door. Shun Xing Xing is rumored to supply some of the best restaurants with its pi dan, and when I arrived, a spry, elderly man was already loading up a handcart with cartons to deliver to various groceries and restaurants unnamed.

The woman at the window was Mrs. Kwok, whose father had opened the shop selling all kinds of eggs—pi dan, salted eggs, salted yolks, and more—sixty years before. Growing up in the business, she told me, she had watched her father’s pi dan specialist make the eggs by burning rice husks and fragrant branches. He was a Chinese man from the mainland whom her father had hired just to make them, she said.

But now, she admitted, she did not make the pi dan at her shop anymore. She bought them all from the mainland. Despite what everyone says, she said, everyone imports their eggs. It is too time intensive, too unpredictable a process to run a business on, she said. In fact, she was closing up shop permanently, as soon as possible. “I’m ready to cook dinner for my two sons every night and relax,” she said.

Later, I went to see the wholesale market to find where all the other egg sellers had gone. It was a huge industrial concrete warehouse of stalls set up like storefronts and living rooms. In the egg section, there were thousands of boxes of small quail to large goose eggs, stamped for export to everywhere in the world. Little kids watched TV next to their parents as they sifted through all their cracked eggs.

On the top floor, I met a woman who explained that all the best pi dan in Hong Kong—in Asia really—were coming from central China and Taiwan. But she could not, or would not, say definitively how they were made. She pulled out samples from producers who still used rice husks and clay, but she thought some might have been brined first and then aged in the coating for appearance’s sake. When I wanted to buy some, she took one out of my hand and wouldn’t give it back. It was no good, apparently, but she wouldn’t explain why.

*

In Hong Kong, pi dan have long been a staple even though the process by which they are made remains mysterious. They are served at breakfast and yum cha with congee (rice porridge), and late at night in noodle shops as an appetizer with a side of pickles or simply soy sauce and ginger. At Yung Kee, a Michelin-starred restaurant that began as a dai pai dong, a cart serving roast goose by the pier, the pi dan with their tang xin, a yolk more molten than creamy, are one of the main draws.

They serve their eggs quartered and accompanied by a mound of thinly sliced pickled ginger. Sometimes diners add a glass of Bordeaux. Others request sugar for dipping.

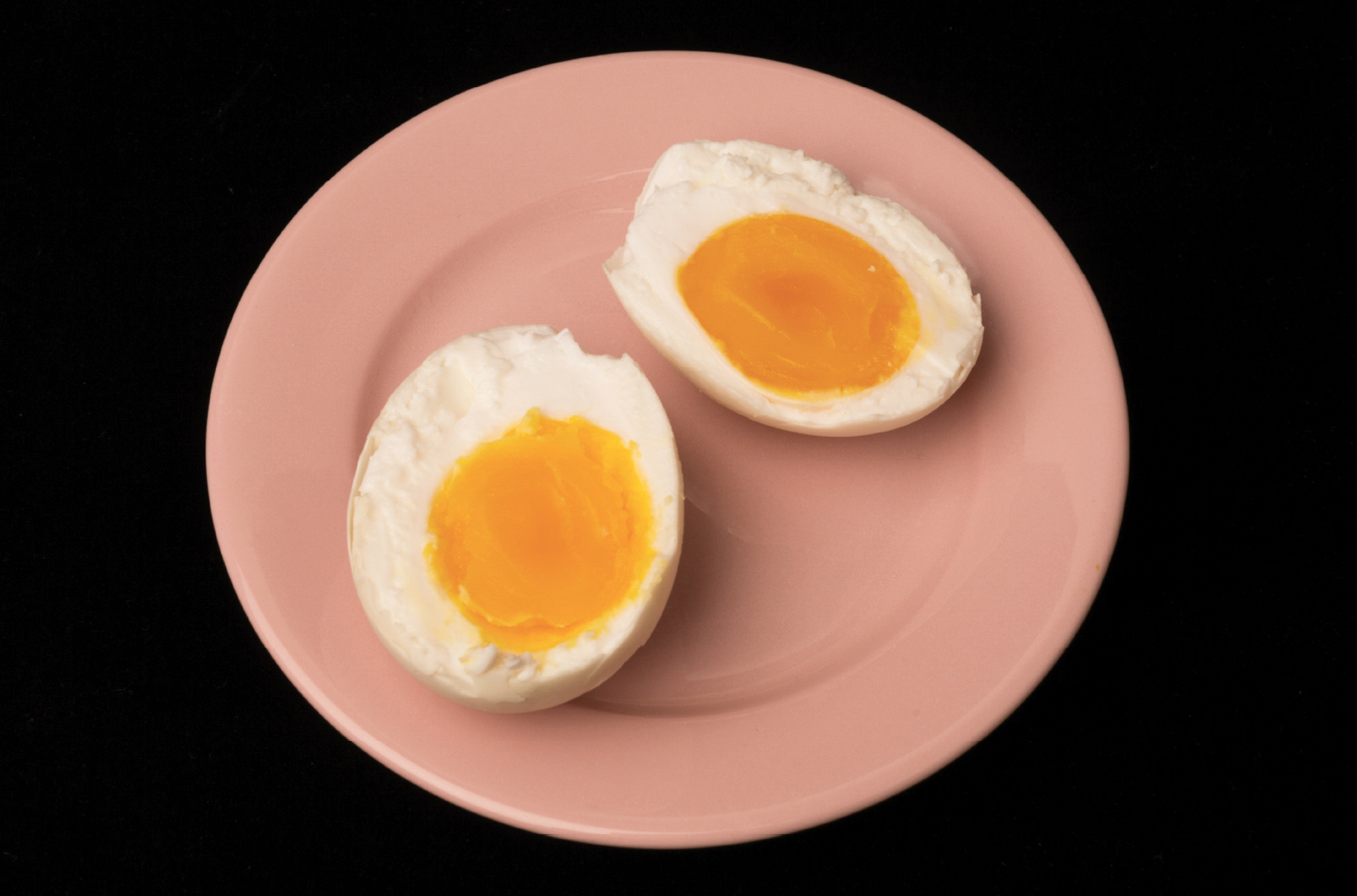

Carrel Kam, the grandson of Yung Kee’s founder, said they still made their eggs by the barrel at their own factory using a liquid brining method. They had been using largely the same technique since the 1970s, trying to perfect the ratios, temperature, and time that would yield the most eggs with soft jelly whites, a creamy yolk, and no trace of a “horse urine smell.” When an egg goes too far, it’s the worst, he said. “You can really feel it in the throat.”

Yung Kee had set up a climate-controlled room held at a steady 80 percent humidity, and found the right ratios for adjusting the salt, lye, or lime, depending on the weather report. They had figured out that they generally got the best results somewhere between forty and fifty days of brining time. But even with all that in place, the experts at the factory, the precision measurements, and the climate control, they still ended up with plenty of bad eggs.

Another hitch was the eggs themselves, which came from Hubei, a lake province in central China. Every year in the late spring, the ducks gorged on little river shrimp and fish, and their egg yolks turned bright red and oily. Even that changed the chemistry.

“That’s just the way it goes with weather and nature and handmade things,” Kam said. “Everyone is still trying to find the best way.”

Iceland Does It, Too!

In northeast Iceland around Lake M´yvatn, duck eggs are stored in boxes of dry ash, which both desiccates and preserves them; they are then boiled before eating. The alkaline ash is collected from the smokehouses (which use sheep dung as fuel) but the tradition may have sprung from finding ways to use the alkaline ash periodically tossed out by the still active nearby volcano.

Congee with Century Eggs

Congee (jook) topped with quartered century eggs is the kind of thing I want when I’m sick—it makes me miss my mom’s cooking. I emailed her for congee guidance. She likes to soak her rice overnight with salt and oil because “some people think that the jook will be smoother and easier to boil the next day,” she emailed. I call for dried scallops here, but dried oysters are a good swap-in, too. The point is a gingery, peppery congee that’s a backdrop to those funky, savory eggs.

Makes 6 servings

1 cup jasmine rice

8 cups water

+ salt

½ tsp vegetable oil

1 piece (1½ inches) fresh ginger, peeled and smashed

4 dried scallops

½ lb ground pork

1 tsp sesame oil, plus more for serving

2 tsp soy sauce, plus more for serving

½ tsp white pepper, plus more for serving

1 tsp Shaoxing wine

½ tsp oyster sauce

2 century eggs, quartered

+ thinly sliced scallions

+ roughly chopped cilantro

+ Fried Shallots, store-bought or homemade (this page)

1. In a pot, soak the rice for 4 hours or overnight in the water with a generous pinch of salt and the vegetable oil.

2. The next day, add the ginger and scallops and bring the pot to a boil. Reduce to a simmer and cook until the rice grains have broken down and the porridge has thickened, about 30 minutes. Stir periodically to keep it from sticking to the bottom.

3. Meanwhile, mix the pork with the sesame oil, soy sauce, white pepper, Shaoxing wine, and oyster sauce and let it marinate while the porridge cooks.

4. When the porridge has thickened, add a splash of water to the pork mass and break it up with your fingers. Add the marinated meat to the pot, and cook for another 10 minutes, until the pork bits are cooked through.

5. Taste and adjust the seasoning. If you like your porridge thinner, add more water.

6. To serve, ladle portions into bowls. Drizzle extra soy sauce and sesame oil over the top, and more white pepper if you like it peppery (I do). Finish with the century egg pieces, scallions, cilantro, and fried shallots.

Spicy Basil and Century Egg Stir-Fry

In Thailand, century eggs, affectionately called khai yiao ma (literally “horse piss egg”), were once a staple at Teochew-style rice porridge shops and would be served as one of the many accompaniments to rice as well as quite on their own—just peeled, halved or quartered, and plated. But over the decades, century eggs have made their way into several traditional Thai dishes, creating either entirely new dishes or new spins on old classics. This dish, khai yiao ma phat ka-phrao, a newish favorite of many Bangkokians, falls into the latter category.

—Leela Punyaratabandhu

Makes 3 to 4 servings

6 garlic cloves

3 to 4 Thai bird’s eye chilies or 2 serrano chilies (or to taste)

1 tbsp fish sauce

1 tbsp oyster sauce

1 tbsp dark soy sauce

1½ tbsp grated palm sugar or 1 tbsp packed light brown sugar

+ vegetable oil, for frying

3 cups tightly packed holy basil leaves

6 century eggs, peeled and quartered lengthwise

½ lb ground pork

1 serrano or jalapeño chili, cut into slivers

+ jasmine rice, for serving

1. Grind the garlic and bird’s eye chilies in a mortar or mini food processor until you get a coarse paste with each bit being the size of a match head. Set aside.

2. Combine the fish sauce, oyster sauce, dark soy sauce, and sugar in a small bowl. Set aside.

3. Line a baking sheet with two layers of paper towel and place it near the stove.

4. Pour enough vegetable oil into a wok to form a ¾-inch-deep pool. Heat the oil over medium-high heat.

5. When the oil is hot, throw 2 cups of the holy basil leaves into it and quickly step back, because it will splatter. In just a few seconds, the splattering will subside. Approach the wok and stir the basil around with a fine-mesh skimmer. When the leaves become crisp and translucent, in less than a minute, scoop them out onto one side of the prepared baking sheet. Don’t turn off the stove just yet. While the oil is still hot, add the egg quarters and deep-fry, stirring gently but constantly, until they’re golden brown, about a minute. Transfer them to the vacant side of the prepared baking sheet.

6. Pour the oil out of the wok, leaving only 2 tablespoons, and put the wok back on the stove. Immediately add the garlic-chili paste and stir-fry quickly until fragrant, about a minute (do not brown the garlic). Add the pork and stir-fry until no longer pink, separating it into tiny chunks as you go. Add the prepared seasoning sauce, scraping every bit out of the bowl. Continue to stir-fry until everything is well mixed. Add the remaining 1 cup basil leaves and the slivered chili to the wok and stir-fry until they wilt a little. Add the deep-fried eggs and stir just until heated through.

7. Plate the stir-fry and top it with the crispy basil leaves. Serve immediately with warm jasmine rice.

African Golden Oriole

Salted Duck Eggs

The Essential Techniques for the Peasantry, written for the Chinese home cook 1,500 years ago, includes this instruction for preparing salted eggs: “Soak a duck egg in brine for one month.” Today, xian dan on Asian grocery store shelves are still made this way in a brine of typically one part salt to four parts water.

Another way of making salted eggs in the shell is encasing it in a paste of salt and clay, which hardens, creating a skin that protects like plastic but breathes like skin. Treated this way, eggs last unrefrigerated for many months. Wet or dry, the salt slows bacterial growth and draws out moisture through the shell. The salt molecules disrupt the bonds in the proteins of the egg yolk and with time separate them from the fats, eventually turning the yolks richly oily and dense, and thickening the egg whites.

This recipe is not traditional but gets the eggs where we want them: It’s a piece of cake except for the four-week wait.

—Tienlon Ho

Makes 1 dozen salted eggs

¾ cup Shaoxing wine

¾ cup fine sea salt

12 duck eggs

1. Pour the Shaoxing wine into a small bowl and pour the salt into another. Roll the eggs, one by one, into the wine and then into the salt, so a layer of salt coats the egg.

2. Put the salt-covered eggs into a zip-top freezer bag. Press out the air and place the eggs in a plastic container, and cover. Date your eggs and let sit in a cool, dark place for 4 weeks.

3. Rinse the eggs and either use or store them. You can hard-boil the eggs to eat with congee or use in Bibingka (opposite), or use fresh in Steamed Salted Egg with Pork (this page). Refrigerated, they will keep for a month.

Bibingka

Bibingka—it’s dope: It’s a Filipino street dessert and it’s usually rice flour, mad egg, and butter wrapped in a banana leaf (sometimes with cheese, like white cheese or sharp cheddar). And there’s salted duck egg in it, too—pieces of duck egg on top or inside, so you get bites of the salty duck egg to cut through all the richness, and counterbalance the sweetness of the butter. It’s really good.

In the Philippines, in the provinces, there are small little neighborhoods, barrios. By six a.m. you’re hearing roosters and people whistling and yelling. Hawking already starts by six thirty, and you wake up to that. Outside, people are running or walking, going to their next thing—they’re in jerseys and sandals because it’s a little poorer in the provinces. It’s a little microeconomy where they’re taking care of one another. We were driving in our car one day, and my mom was like, “Oh, you know who makes the best bibingka? My so-and-so, she makes it best…” And she rolled down the window and she said, “Oh, that’s her! Maria, come over here!” We were driving all slow in traffic and Maria walked up to us and she just slanted it toward us—boom!—and we ate it hot. It was wrapped up in a banana leaf—buttery and hot as hell.

Growing up, we tasted a lot of different takes on bibingka: Some were breadier, some were more airy. Some families use Bisquick pancake mix—probably an American influence. We settled on this recipe, which is in between.

—Chase and Chad Valencia

Makes 8 servings

1 cup rice flour

2½ tsp baking powder

⅛ tsp salt

3 tbsp butter, at room temperature

1 cup sugar

3 eggs, beaten

1¼ cups coconut milk

1 piece banana leaf

1 Salted Duck Egg, hard-boiled, peeled, and sliced

½ cup grated coconut

1. Heat the oven to 375°F.

2. Combine the rice flour, baking powder, and salt in a bowl. Set aside.

3. Cream the butter in a large bowl, and gradually add the sugar while whisking. Add the beaten eggs, incorporating them into the butter-and-sugar mixture well. Gradually add the flour mixture and then add the coconut milk.

4. Line a pie plate or cake pan with the banana leaf. Pour the well-mixed batter into the lined pan. Bake for 15 minutes. Remove and add the sliced salted duck egg on top and continue to bake until a toothpick comes out clean, 15 to 20 minutes.

5. Garnish with the grated coconut and serve warm.

Picklopolis Pickled Duck Eggs

I’ve always loved duck eggs for their density. The yolks are extremely heavy and dark—perfect for baking, and especially for making pasta. I started using them a lot when one of our fellow vendors at Portland Farmers’ Market had a surplus and asked me if I could do anything amazing with them. I had always made pickled eggs and thought duck eggs would be perfect for pickling. I like to undercook them so that the yolks are still runny. At the market, we sell them on sticks. They are wonderful on their own—the first bite is hot and salty, and the yolk is custardy and mild—but even better on a salad niçoise or lightly decorated and served like a deviled egg. I also do a green jalapeño one, but the red is the best.

—David Barber

Makes 6 pickled eggs

½ lb red cherry peppers or red Fresno chilies

6 garlic cloves

1 tsp salt

1 cup distilled white vinegar

6 duck eggs

1. Wash and stem the peppers. Combine them in a blender or food processor with the garlic and salt and process until finely chopped. Add the vinegar and continue processing until smooth.

2. Place the duck eggs in a large saucepan and cover with cool water. Set over medium-high heat and bring to a boil. Cover, remove from the heat, and let stand for 8 minutes, until soft-boiled. Drain and shock the eggs in cold water. Peel the eggs.

3. Arrange the eggs in a 2-quart jar and add the pepper purée. Seal, gently turn upside down a couple of times to distribute everything, and refrigerate for 1 week. The eggs are ready when the yolk becomes firm and pliable and the egg tastes seasoned throughout.

Pennsylvania Dutch Pickled Beet Eggs

While there are a great many foodstuffs from Pennsylvania’s breadbasket that could undoubtedly endure the apocalypse, the question really is: Which of them will sate the hunger of the discerning survivor? My bet is on pickled beet eggs. They are pickled, of course, and ubiquitous. Menacingly rosy jars of them haunt the back bars or counters next to the cash register of many of the greater Lancaster area’s finer and not-so-fine establishments. Most are graced by a gray halo of dust that says, “I’ve been here since the seventies, and I’ll be here after you’re gone.” No doubt that’s the attitude you’ll want to take into the looming zombie/robot/alien wars, and with their mix of fortifying protein and piquant beetiness, these eggs will help keep your fighting spirits high!

—Mark Ibold

Makes 12 pickled eggs

12 Hard-Boiled Eggs, peeled

+ tarragon (optional)

1 garlic clove (optional)

1 jar (12 oz) pickled red beets (in their liquid)

1 cup apple cider vinegar

1 cup water

3 tbsp sugar

1 tbsp salt

1. Put the hard-boiled eggs into a 2-quart glass jar. If you want the End Times to be fancy, you could tuck some tarragon and a clove of garlic in there, too.

2. Heat the beets and the liquid from the jar, vinegar, water, sugar, and salt in a saucepan until just boiling. Dump over the eggs. Put into the fridge (or the coldest area of the cave you are hiding out in) for a few days and they should be ready to eat. The longer the eggs stay in the liquid, the more colorful they will be when cut in half.

Eggs at the END of the World

Kate Greene

Here’s a twist on an old hypothetical. Imagine, instead of a deserted island, you’re on Mars. You can cook and bake, so long as all the ingredients are shelf stable. Given these constraints, what’s your comfort food?

I thought mine might be peanut butter on toast. Or chocolate milk. Something I was used to eating or drinking back home. I did not expect my comfort food to be a Julia Child–style French omelet with parsley and cheese. But French omelet it was, thanks to one of the most delicious inventions of the twenty-first century: egg crystals.

Okay, I wasn’t technically on Mars. But in 2013 I was a participant in a four-month isolation mission sponsored by NASA. Along with five others, I lived in a dome halfway up the Hawaiian volcano of Mauna Loa as though we were astronauts on Mars. This meant eating only shelf-stable foods, wearing spacesuits whenever we went outside, and communicating with everyone back on Earth via delayed email servers. (It will take as long as twenty-four minutes to send information between Earth and Mars, depending on orbital positions.)

On Mauna Loa Mars, I was grateful for simple pleasures: a spacesuited walk on an overcast day (the suits tended to get stuffy when it was too sunny out), a breakthrough in my sleep experiment, and a good omelet on a quiet Sunday morning.

We are living in the golden era of powdered eggs. Powdered eggs, until now, have been the stuff of campers’ nightmares—with their off-tasting additives and lack of resemblance to actual eggs. But the egg crystals we ate during the mission reconstituted perfectly, and cooked into scrambles and omelets that were indistinguishable from the ones I would make with fresh eggs back home in California.

How did our Martian outpost come to be stocked with such delicious shelf-stable eggs? I asked Dr. Jean Hunter, associate professor of biological and environmental engineering at Cornell, and the principal investigator of our NASA study. She told me that in 2007, while choosing the food for a food study in a different simulated Mars mission just outside of Hanksville, Utah, she taste-tested traditional egg powders side by side with egg crystals. The egg crystals, a brand called OvaEasy, won her over. Hunter decided our four months of food rations would also include a generous supply of these eggs.

OvaEasy is the product of a company called Nutriom, a family-run business based in Lacey, Washington. Nutriom got its start in cheese—concentrating whey—in the 1980s and ’90s. In 1995, a business opportunity prompted the company to develop a “fully functional egg powder,” Leo Etcheto, son of the founder and the head of operations, tells me.

“We spent five years,” he explains, “jet-pulse drying, microwave drying…all kinds of stuff.” Finally, Nutriom discovered a company in Tacoma, Washington, that made vegetable belt dryers—basically conveyer belts that ferry vegetables into a kind of elongated pizza oven where they’re dried. It turned out to be great for dehydrating eggs. They bought one and modified it, Etcheto says. By 2000, Nutriom was using a full, industrial-size dryer and running its own custom-made egg-drying processes to create what the company now calls “egg crystals.”

OvaEasy Egg Crystals

*

Nutriom did not invent dehydrated eggs, of course. By 1865, Charles La Mont received a US patent for “Improvement in Preserving Eggs” by using warm air to desiccate a thin layer of egg batter on metal plates. In 1880, preserved eggs became a hot topic in the New York Times after a fresh egg shortage struck the region. In 1881, preserved eggs traveled to the Arctic on Adolphus Greely’s North Pole expedition, and in the late 1890s, they were critical to prospectors in the Klondike Gold Rush. By the turn of the century, preserving eggs by drying was something anyone with access to Mrs. Rorer’s New Cook Book, A Manual of Housekeeping (1902) could feel emboldened to do.

“Separate the whites and the yolks, spread a few at a time on a clean stoneware or china platter and slowly evaporate or dry in a very cool oven. This powder…may then be used the same as fresh eggs,” Mrs. Rorer wrote.

Today, thanks to a prominent online community of doomsday preppers, there is no shortage of YouTube videos that demonstrate the making of powdered whole eggs at home. You’ll need: eggs, a dehydrator with multiple trays, a knife to scrape the resultant egg chips off the trays, and a blender or food processor to mill the egg chips. You can dehydrate the powder again for good measure. Store in jars. When all hell breaks loose and grocery stores and chickens are hard to come by, you’ll still be able to make your family a frittata.

It’s not as easy, however, to find videos of powdered egg reconstitution or videos of the joyful cooking and eating of them.

*

Today’s powdered eggs are largely not homemade. The majority of powdered eggs come from large-scale industrial processes, which usually start with an egg-breaking machine, a stainless steel contraption into which eggs are conveyed. The liquid then gets pasteurized—tricky business because you have to heat the egg enough to kill bacteria, but not enough “to make an omelet in the system,” says François Quenard, the director of egg processing at Actini. Actini is a French thermal technology company that makes pasteurizing and egg-drying equipment. Their equipment pasteurizes liquid egg as it flows through a tube at temperatures a little higher than 140°F.

Some of this liquid egg is then shipped to restaurants or other food-service facilities; the rest stays around for drying inside a spray-dryer, the most common way eggs become powder.

In spray-drying, liquid egg is pumped at high pressure through a nozzle that jets nebulized egg into an enormous, room-size chamber. At the same time hot air, nearly 400°F, blasts in. The hot air evaporates water from the egg, and solid particles rain down for collection. Then the powder goes through the dryer again, which makes finer particles so the egg dissolves more easily in water when it is reconstituted—“like Nescafé,” Quenard says.

Why doesn’t the hot air in a spray-dryer cook the egg? While it’s true that egg proteins change shape when heated and when agitated (which is what allows them to become solid when fried or whipped into a meringue), the heating inside the spray-dryer is such a quick blast that it doesn’t warp the egg proteins as cooking at such a high temperature normally would.

Freeze-drying is the method preferred by the military for feeding soldiers in combat, and by NASA. Eggs are prepared normally—a batch of scrambled with scallions and cheese, say—but then frozen in a chamber at very low pressure. The freezing turns the water within the cooked egg to ice, and the low pressure sublimates the ice into a gas, leaving preserved chunks of dry egg. Just add hot water, drain, and they’re (almost) back to their original state.

*

Nutriom’s process of making egg crystals, in contrast, sounds as artisanal as an industrialized egg process can be. First, it’s slow. “We process in one week what a modern spray-dryer does in ten hours,” Leo Etcheto says. Second, the drying is done at low heat, never reaching above 110°F.

The egg liquid is spread in an extremely thin layer on a drying belt. Hot water below evaporates the liquid while warm air on top absorbs the water, Etcheto explains. What comes off the belt are egg “crystals”: They go directly into the package you buy, he says. There are no additives.

“Because of the low temperatures and because we never freeze the egg, you don’t have any of those issues [that other preserved eggs have], and then we don’t change the color,” Etcheto says. “It binds. It’s fluffy.”

*

Nutriom’s belt-dried egg crystals were good enough for my crew on Mars. And maybe, eventually, they’ll make their way to real Mars, too—though probably not for a while. Vickie Kloeris, the manager of the International Space Station’s food system, says that eggs in space are all freeze-dried—dating back at least to the Apollo program.

Astronauts add hot water to pouches that contain eggs (scrambled eggs with cheese, or quiche are two current options), heat in the galley oven if necessary, and then eat. Of course there’s no real cooking in space. Even salting your food is different—a squirt of saline solution as opposed to a messy saltshaker. And though the eggs can be a little “crumbly,” and astronauts have to be careful when they eat them because crumbs can clog filters on the space station, Kloeris confirms that eggs have always been popular in space.

My beloved powdered eggs don’t make much sense in space right now: in a zero-g environment, you can’t cook or bake. But Mars has some gravity, about a third of Earth’s. In a 2014 experiment led by a group of Cornell and Makel Engineering researchers, Drs. Apollo Arquiza, Bryan Caldwell, Susana Carranza, and Jean Hunter tried to find out just what it would be like to cook with Mars gravity. To do so, the team took a ride on NASA’s airplane, nicknamed the Vomit Comet, which simulates a range of low gravity scenarios by looping along a parabolic path. The researchers brought with them a frying pan and some canola oil (dyed red to see where it splattered), tofu, and hash browns. They discovered that cooking foods on Mars in an open pan would likely be a messy business with oil flying farther than on Earth and settling down in slow motion.

For this and other reasons, it’s unlikely anyone will scramble an egg or fold an omelet on Mars anytime soon. The first NASA astronauts to the Red Planet, estimated to arrive in the 2030s, will be expedition crews that will eat meals similar to those on the space station, says Dr. Grace Douglas, food scientist at NASA. “The idea initially would be to use the prepackaged foods,” she says. Although, she adds, colonization of Mars might allow for some cooking, but if it ever happens it could be many years away.

Still, for me, Mars will always mean omelets. During our four-month mission, we ate almost all meals together. This meant cooking and cleaning for six, on a rotating basis. We were also very busy, hewing to a fairly demanding work schedule. But on Sunday mornings we could eat what we wanted, alone or with others. I remember well sitting down to my French omelet, Finn Crisp crackers with jam, and tea—Earl Grey (hot), relishing the opportunity for quiet and calm. Behind me, just beyond our habitat’s walls, miles upon miles of red rock extended, uninterrupted.

Ostrich