1 Far-Right Revisionism and the End of History

Louie Dean Valencia-García

In 2013, members of the French ethno-nationalist youth group ‘Génération Identitaire’ (Generation Identity) posted a video to the digital video platform YouTube in an attempt to propagate a fear of immigrants whilst simultaneously claiming they had ‘discovered’ their history—as though it were something lost, hidden.1 They asserted in their declaration, ‘We’ve rejected your history books to re-gather our memories’. The black and white video featured young, white men and women close-up, completing each other’s sentences:

We’ve stopped believing in a ‘global village’ and the ‘family of man’. We discovered we have roots, ancestry, and therefore a future. Our heritage is our land, our blood, our identity. We are the heirs to our own future… The lambda emblem, painted on our proud Spartan shields, is our symbol.2

The members of Génération Identitaire rejected the globalised world in which they grew up and took a stylised version of the Spartan’s ancient symbol (Λ) as their own, declaring war on the world they saw as a product of the cultural revolution of the 1960s—which was a culminating moment for anti-colonial struggles and for the civil rights for people of colour, women and queer people in Europe, the United States and in former colonies. Of course, these so-called ‘identitarians’ seemed to ignore the fact that ancient Sparta was never a unifying pro-Hellenic force; moreover, it had its own very queer history that certainly would have clashed with how the group imagined that ancient past.3

History, popularly, is a thing which is stretched, invented and made of stubborn clichés that refuse to give way:

History repeats itself.

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

Winners write the history.

History is made of fragments. Sometimes these pieces are things jotted down in a journal or a scrap of paper. History is created out of newspapers, cave paintings, buildings, art, word-of-mouth, ruins, geological or scientific investigations, statues, fables, excavations and television shows. History is saved in museums, libraries, government and organisational archives, graves, shipwrecks, pyramids, attics and Twitter. Historians sift through these ephemera in their attempt to reconstruct and understand the past. When digging through this material, historians quickly realise the truth of the matter is that nothing repeats exactly the same—although there certainly are patterns to be investigated. Culture is not static and sometimes the ‘losers’ also write history—seen in the US context where numerous American military bases have been named after Confederate ‘heroes’.4

If visualised, some might think of history as a Picasso painting, distorted, broken in fragments, but screaming with meaning. Others might see it as Michelangelo’s David, a form that looks perfect from one angle, but in reality, it is distorted to privilege a singular perspective. Yet still, someone might see history as something like a Georgia O’Keefe painting, natural but heavily coded. Perhaps it is like the photography of Jeff Chien-Hsing Liao, whose infinitely detailed photos are comprised of layer after layer of stitched together images of the same place at different times, conveying some sort of greater truth in the final product. Yet still, others think of history like the Artemision Bronze—masculine, powerful and enduring. As traditionalists, many members of the Identitarian movement would most likely identify with this latter understanding of history.

Traditionalism, as the Italian esoteric fascist philosopher Julius Evola (1898–1974) understood it, is a sort of idealised, static idea of the past that is deeply rooted in custom and a nation’s spirit, as well as blood. The traditionalist world is one that is the ‘antithesis’ of the modern world. For Evola, and those Identitarians who have adopted his philosophy, traditionalists are those elite who stand in the ruins of modernity, who rise above depravity and degeneration, who both harden themselves against change but also have found traditionalist values that they see as now hidden from most men. To understand how the far right comprehends history one must understand that for their ideologues our contemporary age is one of decline and degeneracy. For them, an idealised, imagined past must be restored.

History has long been thought of a cyclical—at least since Polybius proposed his cycles of political evolution.5 Traditionalists, like Evola, conceive of history as a sort of politics of inevitability—that we rotate between a golden age, silver age, bronze age and dark (or iron) age.6 This type of teleology is prominent amongst many older traditions globally. In Nordic pagan tradition, a golden age (gullaldr) comes after Ragnarök, the end of our current epoch. In Christianity, humans began in paradise, suffered a fall, found redemption, but still face a coming apocalypse—followed by an eventual return to paradise for the select few. In Hinduism, there, too, are cycles. Even Francesco Petrarca (1304–1374), much accredited for the explosion of humanistic thought and inquiry in the ‘Renaissance’, believed himself to be living in a ‘dark age’—much to the chagrin of medievalists.7 From this perspective, traditionalists see the world we live in as part of a cyclical narrative that always needs redemption. Evola writes, ‘When a cycle of civilization is reaching its end, it is difficult to achieve anything by resisting it and by directly opposing the forces in motion. The current is too strong; one would be overwhelmed’. Like Evola, many in the far right today see themselves as ‘riding the tiger’, being of an elite who is able to withstand and master the wild animal of modernity—to surf above the turbulent waters below them.8 For them, history has entered its low point and thus must be restarted—some believe in a theory of ‘accelerationism’—an attempt by white nationalists to hasten what they see as an inevitable race war—which has led to violent attacks in Christchurch, New Zealand and El Paso, Texas.9

Figure 1.2 United States President Donald Trump wearing a ‘Make America Great Again’ hat. The phrase recalls an unspecified idealised past—a fascistic palingenetic tendency. Windover Way Photography/Shutterstock.com.

Most recently, the belief in history as cyclical found its way into United States President Donald Trump’s campaign rhetoric—calling to ‘Make America Great Again’. Of course, when exactly this great past was is never specified—but one surmises it is before queer people could marry, or even before there were protections for people with disabilities, or maybe before women had their right to abortion recognised by the US Supreme Court. Worse, maybe this supposed era of greatness was during Jim Crow, or before the American Civil War. Mussolini wanted to bring back the greatness of the Roman Empire. Hitler looked to the pre-Weimar years. Francisco Franco recalled the Spanish Empire and the so-called the ‘Reconquest’, which persecuted and exiled Muslims and Jews. By seeing time as cyclical, something that can be ‘brought back’, the far right celebrates an idealised past where the white man was master of his home and the colonised world. This cyclical thinking is what allows for what historian Timothy Snyder calls ‘a politics of inevitability’.10

Indeed, the traditionalist understanding of history as cyclical is inherently challenged by progressive understandings of history. In progressive narratives there is not a desire to return to the past—the past is past, but informs our present. Rather than focusing on what was, there instead is a desire to move towards a future. This type of history, too, can have its own teleology if there is an assumed end point that must be reached. Somewhat optimistically, in The End of History and the Last Man Francis Fukuyama argued,

As mankind approaches the end of the millennium, the twin crises of authoritarianism and socialist central planning have left only one competitor standing in the ring as an ideology of potentially universal validity: liberal democracy, the doctrine of individual freedom and popular sovereignty.11

However, even Fukuyama wondered if the ‘present trend toward democracy’ was in fact a ‘cyclical phenomenon’.12 Speculating about the role of economic crises in the rise of illiberal ideologies he wrote, ‘What reason, then do we have to expect that the situation of the 1970s will not recur, or worse yet, that the 1930s, with its clash of virulent anti-democratic ideologies, can not return?’13 Indeed, as Fukuyama later points out, both trends are possible, there are ‘cycles in the worldwide fortunes of democracy’ and there is a ‘pronounced secular trend in the democratic direction’.14 Most resoundingly, Fukuyama worried that the arrival of an ‘end of history’, a supposed triumphant win of liberal democracy, could end with a ‘last man’ who is both ‘self-absorbed’ and ‘devoid of thymotic striving for higher goals in pursuit of…private comforts’. These last men would, he feared, become ‘engaged in bloody and pointless prestige battles, only this time with modern weapons’. Moreover, these last men would not have ‘constructive outlets for [their] megalothymia’ which could lead to a ‘resurgence in an extreme and pathological form’ of being. Almost prophetically, writing decades before Donald Trump assumed the presidency of the United States of America, Fukuyama worried that for all the recognition Trump (and individuals like him) received, they were ‘not the most serious or the most just’. For Fukuyama, despite being in a utopic society, where the world was just and prosperous, there would always be those, like Trump, who could not satisfy their own ‘thymotic’ natures—that is to say their desire for recognition, or supremacy. Indeed, as we have already seen in the Trump presidency, bloody and pointless prestige battles are occurring. In the second decade of the twenty-first century, pathological megalothymia and a desire for supremacy have arisen—both in the forms of white supremacist ideology and American nationalist exceptionalism.

Alt-Histories

Historians Stanley Payne, Roger Griffin, Denis Mack Smith and Robert Paxton have described the fascist palingenetic tendency to recast or idealise an imagined past. In Spain, after the loss of its colonies in 1898, the fascist Falange party pushed a mythical vision of ‘Hispanidad’, a type of Spanish-Nationalism that attempted to recast the Spanish colonial period as benign. In the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust, Nazi sympathisers already were proposing a denial of history and inserting factually untrue conspiracy theories. Through the creation of alternate histories and facts, the far right’s impulse has long been to undermine liberalism (and the Enlightenment project altogether) to re-write and alter history so that to legitimate essentialist, racist, sexist, ethnocentric, nationalist and heteronormative beliefs—what they call ‘traditional’ beliefs, despite knowing those traditionalist beliefs have more to do with nineteenth and twentieth understandings of class, race, nation, gender and sexuality than some ancient past. These beliefs, indeed, lie at the core of what we now recognise as fascism.

The term ‘alt-history’ refers to both white nationalist Richard Spencer’s ‘alt-right’ movement—which readily misconstrues the past and then refers to their own alt-history as authority—, and the rhetoric used by Trump’s counsellor, Kellyanne Conway, who infamously coined the phrase ‘alternative facts’ to describe her (ab)use and skewed interpretations of fact when giving an interview on the American political show Meet the Press in 2017. Conway’s use of the phrase indicated a selection of ‘facts’ (which for her did not have to be true) to construct a politically useful narrative—one that is just parallel enough to truth that one must learn to identify the departures from truth to see where the weaving of the narrative becomes undone.

In 2016, American Identitarian and founder of the ‘Alt-Right’ movement Richard Spencer began advocating for a post-American world where a ‘white ethno-state’—‘a homeland for all Europeans from around the world’—would replace the United States as we know it. For Spencer, this would happen through a process of a supposed ‘peaceful ethnic cleansing’ or ‘peaceful ethnic redistribution’.15,16 This radical idea for a white ethno-state through ‘cleansing’ or ‘redistribution’ became a regular talking point in Spencer’s interviews and rallies. To legitimate his idea, Spencer often cited the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 as a successful example of ‘peaceful ethnic cleansing’. While indeed, there was an attempt to match national and ethnic identities within the borders of some new nation-states during this era—this process was largely a failure given the complex and overlapping nature of identity. Moreover, as historian Mark Mazower points out in his discussion of aftermath of the Great War,

Exterminating minorities—as the Turks tried with the Armenians—was not generally acceptable to international opinion…The victor powers at Versailles tried a different approach—keeping minorities where they were, and giving them protection in international law to make sure they were properly treated so that in time they would acquire a sense of national belonging.17

Displacing populations was never a goal of the Paris Peace Conference. In effect, Spencer used a decontextualised historical occurrence to legitimate a potential future—creating a distorted, alternative version of history that attempted to legitimate a violent process hidden behind a peace conference. For Spencer, like many conservatives, what they call history acts to give authority, and is not as a thing to be considered critically. And, in fact, it can be entirely invented as long as it legitimates their ideologies. A more public version of an attempt to alter history, preventing critique of the US president Donald Trump, was recently seen in a United States National Archives exhibit celebrating the centennial of women’s suffrage which blurred the words of signs in photographs critical of the president; signs referencing women’s anatomy were also blurred. Archives spokeswoman Miriam Kleiman claimed the blurring was not an attempt to ‘to engage in current political controversy’ and ‘keep the focus on the records’. The Archive’s blurred photos were an attempt to erase the history of the 2017 Women’s March.18

In the ancient Greek, ‘ἱστορία’, or history, was thought of as a type of inquiry based on knowledge of the past. History was not simply things of the past, or fragments, or mythology, but the process of asking questions about those pieces and describing cause and effect through narrative—to learn something. History requires the practitioner of that inquiry, the historian, to look at the fragments and ask questions of them— taking none of it for granted—and looking for a multitude of perspectives and interpretations. At the professional level, the study of history, like all academic scholarship, requires a certain amount of discernment. We write history to understand where we were, but at the same time, we run the risk of transposing the present on the past—one of the greatest sins the historian can commit, even though our questions are inherently and inevitably formed by our present. This paradox is unavoidable, but to avoid faulty logic the historian must acknowledge this simple fact and work through it to avoid paralysis.

History is altered through historical revisionism, or the modification or rejection of historic arguments (often based on the interpretation, selection or availability of archives) and the recovery of new historical information. Alt-histories are created by: (1) historical denial, which can include abject rejection of archives and historical evidence; (2) belief in cyclical, or teleological, history which assumes where we are going or where we have been; (3) declination narratives which assume a theory of degeneracy in place of understanding of change; (4) mythologisation that is created when facts are replaced with chimeras; (5) nostalgia for an imagined past that often supposes both a declination and attempts to selectively exclude or underline historical facts and narratives; (6) ahistoricism based purely on untruth; and (7) through often fragmented and biased ways history is remembered and portrayed in popular public memory (films, textbooks, television shows, etc.).

When we impose our present on the past to justify an understanding about the present, we risk creating an alternate timeline. These alternate timelines, when abused and given legs, create what we might call alternative histories—or alt-histories. Through this abuse of history, we see an attempt to uncritically reject both historical consensus and understanding of the past—which presents a very real risk to the study and utility of history itself. Alt-histories are not simply a difference in interpretation of fact but rather are made by intentional distortion. Historians always disagree, but on some level, they still engage with those with whom they disagree as long as those disagreements are made in good faith—this is why historians study historiography, or the history of history. Alt-histories, unlike history itself, reject fact and a genuine interest in knowledge or historical inquiry. Alt-histories use decontextualised historical fragments to legitimate ideology or belief first and foremost, and not to understand how things came to be. Alt-histories are an attempt to change political and historical narratives as part of what many Identitarians call a ‘meta-political’ strategy to legitimate their beliefs.19

In the postwar era, as society began to break away from the binaries of cyclical and progressive views of history, and as access to more information than ever before became prevalent, we were left with infinite histories and interpretations. To add to the fragility of history, postmodern thought and false equivalency gave away to a ‘crisis of infinite histories’—where uncritical thinking left some people distrusting of scholarly sources and scientific fact through a sort of teleological loop that justifies ideological prejudices. This postmodern condition that left students and writers of history with an infinitude of interpretations and facts is not inherently a bad thing when considered critically. However, today, many have come to distrust scholarly evidence, which ultimately threatens what we mean by ‘fact’. The alt-histories derived from this distrust depends on invented conspiracies that let the ideologue reconcile illogical or simply untrue conclusions—drawing crooked lines between unrelated nodes. This distrust of academic research has particularly affected the ways some elements of the public accept scholarship across disciplines—from climate change to vaccine sceptics. People fear everything is subjective—that facts are moulded to benefit bottom lines and political expediency—which is not untrue. This does leave the common person asking if everyone has an interpretation and whether all interpretations are equal. The expert thus loses credibility—replaced with internet conspiracy theories.

Figure 1.3 Supporters of the far-right Golden Dawn party celebrate after the early election results at their offices in Thessaloniki, Greece on 17 June 2012. The group uses a ‘meander’ design to recall ancient Greece, which is also reminiscent of the swastika, another appropriated meander design. Alexandros Michailidis/Shutterstock.com.

To make sense of infinite interpretations, people often fall prey to false equivalencies and binary thinking—to hear both sides of the story as though there are only two perspectives. Some might even turn against the postmodern world, as though it were an ideology and not merely a description of ways in which people negotiate their lives in the late capitalist, postcolonial era. This desire to reject the complexity of postmodernity—for an imagined simpler world of the past—has turned some to the likes of right-wing traditionalist Jordan Peterson. Postmodernity left us with a construction of time that is neither cyclical nor progressive, but still has elements of both, shattered into alternate and competing timelines. The shattering of the illusion cyclical and progressive history left us trying to figure out ways to usefully study history given the infinite possibilities. This fractured history has also left pressure points that were particularly vulnerable for malintent and that could be leveraged by conspiratorial-minded right-wing ideologues. This book attempts to locate some of those weaknesses.

Postmodern histories, which are part and parcel of late capitalism, are indeed subjects for historical debate, and we should be clear about the dangers embedded in them. However, when mobilised by the radical right to promote and legitimise nationalistic, racist, sexist, queerphobic, xenophobic, classist and ableist ideologies, we end up with ‘alt-histories’. This is also what turns postmodern histories toxic.

Understanding the Tensions and Constructing Alt/Histories

In the public sphere, charges of ‘revisionism’ are often thrown around when history becomes contentious. Revisionism is not inherently a bad thing. Professional historians know that the process of revising history—looking at new evidence and considering new arguments—is necessary to the study of history. In fact, historiography depends on revisions and arguments. However, despite the rigorous scholarship of historians, there always exists the risk that disproven or outdated constructions of history can survive, deform and become fodder for ideological purposes. Often, these distortions are discovered in public memory, or the ways the general public remembers things of the past—existing not only in history books but also in television, movies, museums, podcasts, oral tradition or underbelly message board sites of the internet like 4chan. Thus, alt-histories exist not only in the minds of ideologues, but are constantly attempting to struggle to colonise and replace history itself in the public sphere.

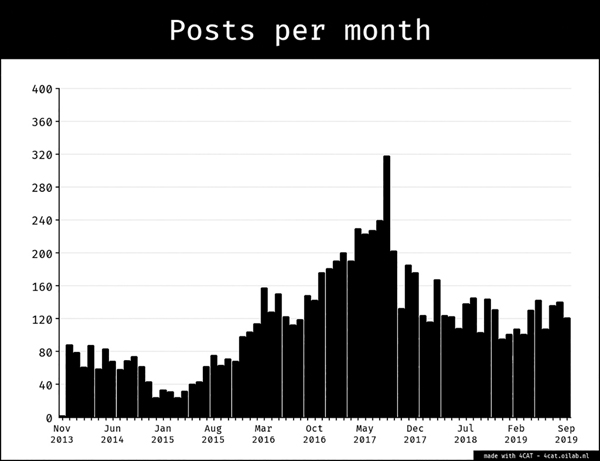

This has recently been seen in the ways that the far right has tried to replace historical facts surrounding Nazism, and more specifically Hitler’s politics, with historical fiction—even seeping its way into the works of otherwise reliable historians. One of the most popular alt-histories contended by the far right, and spurious right-wing propagandists like Dinesh D’Souza,20 is that ‘Hitler was a socialist’. D’Souza published a book in July 2017 titled The Big Lie: Exposing the Nazi Roots of the American Left. That book, a prototype alt-history, included conspiratorial untruths that were also reiterated in D’Souza’s 2018 film Death of a Nation. In fact, on the far-right platform 4chan message board, ‘/pol’, the phrase ‘Hitler was a socialist’ found its peak in the months surrounding D’Souza’s 2017 book—and still continues to be extolled regularly.

Such alt-histories can even find their way into the books written by prominent scholars such as Brendan Simms—currently a professor in the history of international relations at Cambridge University. This was demonstrated in an eviscerating review in The Guardian by the eminent Second World War historian Richard Evans—an emeritus regius professor of history at Cambridge and later president of the Wolfson College at Cambridge. Evans argues Simms’s biography on Hitler essentially conflates socialism and Nazism. Evans argues this is seen when Simms claims, ‘Hitler wanted to establish what he considered racial unity in Germany by overcoming the capitalist order and working for the construction of a new classless society’.21 Turning Hitler into a socialist would result in the ability to vilify socialism, folding Nazism and socialism into one and the same. In his review, Evans rightly points out, ‘[O]verwhelming consensus of historical scholarship has rejected any idea that Hitler was a socialist’.22

While historians constantly have historiographical arguments about interpretations of history, Simms’s argument is based upon misrepresentation of the past—pitting history against an alt-history of dubious origin. Disentangling Simms’s alt-history, Evans forcefully argues Simms attempts to reduce ‘virtually all the major events in the history of the Third Reich to a product of anti-Americanism’—that is to say anti-capitalism—even Kristallnacht, the November 1938 pogrom which sent 30,000 Jews to concentration camps. By using anti-Americanism as a rationale for Hitler’s actions, Simms attempts to cast Hitler as a zealot anti-capitalist. The stretching and distortions of history do more than bend truth. Evans continues,

In the end, Simms hasn’t written a biography in any meaningful sense of the word, he’s written a tract that instrumentalises the past for present-day political purposes. As such, his book can be safely ignored by serious students of the Nazi era.23

Anecdotally, belief that ‘Hitler was a socialist’ has become so prevalent that even in my survey courses of European history I have even had students attempt to make this same argument in class. Those students often point to Hitler’s own use of ‘National Socialism’ to describe his ideologies. Simply put, Hitler, like Mussolini and Franco, sent leftists, socialists and communists to prisons and concentration camps and frequently appropriated rhetoric from leftists for political purposes. Fascists were, in fact, against socialism because of its focus on class issues over those of the nation. Simms, in promoting this conflation, opens the door for history to be replaced—altered.

As this case demonstrates, there are serious tensions between history and alt-history playing out both in the public sphere and amongst scholars. This volume uses the term ‘alt/histories’ to illustrate those tensions. Moreover, it attempts to understand how alt-histories are created by the far right—analysing how they move radical ideologies into the public sphere by using mutated version of facts and history to legitimate such beliefs. The authors propose methodology and practice on how to deconstruct and combat fascistic projects. Importantly, this book, a work of historiography imaginatively conceived to spill outside of the discipline of history, acknowledges that scholars of all disciplines and non-scholars alike all have a stake in history. To this end, historians, sociologists, anthropologists, political scientists, cultural theorists, literary scholars, neurologists, lawyers, classicists and activists have all contributed to this book. By bringing such a wide variety of experts together we can learn ways in which history, law and scientific knowledge have been weaponised by the far right more broadly.

Necessarily, because of the fragmentary, layered and constructed nature of all archives (public and private), the field of history can quite literally include anything. However, age does not make those fragments into history—only rigorous analysis does that. Alt-histories are constructed for ideological purposes through the denial of history, the overemphasis of certain historical facts or an incomplete understanding of historical context. Sometimes they appear as conspiracy theories attempting to explain something unknown or not understood. As weapons, alt-histories are used to exculpate the guilty, casting blame on a marginalised group. Conspiracy theories and the denial of history are often prominent amongst the far right, especially well-known is the case of Holocaust deniers, who reject historical fact outright.24 This rejection of historical fact, uncritically, creates an archive of knowledge that skews perception of an historical event. Of course, this is not limited to the far right, but is particularly prevalent amongst their ideologues.

In his essay ‘Archive Fever’ Jacques Derrida famously described how what is saved in an archive reflects the biases of the collectors.25 When historians do use archives, they must question the evidence collected. A state archive, when not interrogated, can just as easily create an alt-history. History is not ‘written by the victors’—but alt-histories certainly can be. This is because most alt-histories are created because of a lack of critical inquiry into the past. Academic historians are scholars trained to collect evidence, reference secondary sources and are expected to constantly revise history, adding new nuance and details. Historians must also look beyond the archive to understand historical moments or actors—often, this is where historiography becomes most helpful. They must ask what have other scholars written, what have they debated, what sources have they consulted and what is left to be found and considered. Alt-histories fundamentally are like alternate timelines that are reliant upon unprovable, imagined or impossible pasts. Alt-histories are meant to be biased and avoid the process of historical inquiry.

While it might seem obvious, generally, progressives see history as unfinished—there is always work left pending to bring forth progress. Sometimes this is thought of as a fight for equality, sometimes the advent of a new technology. History is propelled not by the simple passage of time, but instead by the decisions people make in order to make history—their agency. Even Karl Marx expected a moment in which after the proletariat had won the battle against capitalism, there would be a utopia waiting at the end—the proletariat would become historical actors, take ownership of their labour and build utopia. Marx was less clear on how we would arrive to this utopia—a still hotly contested question. Communists of the Stalin variety saw a need to impose their vision of the future through a strong centralised state. Anarchists, on the other hand, asked for change to come through coalition and consensus building, along with the radical decentralisation of power structures. Democratic Socialists wanted to install socialism, maintain a strong state, but were determined that socialism would eventually win the day in parliamentary votes. Fascists looked to an imagined past for inspiration for their future.

Sometimes, history is created by chance. Someone throws a net into a running river, and that net catches some sort of artefact that gives us new insight into our past. The historian’s job is to scrutinise each artefact and attempt to find a narrative that explains some aspect of the past or present. However, this is not how all people see history. For many, one discovers history by using a sort of harpoon that shoots through the past and cuts through to a predetermined target. This is what historians call teleology.

The inclination to see history as cyclical is nothing new. We see it in the repetition of minutes, hours, months, years—all dependent upon the simple rotation around the sun. So-called ‘ages’—bracketed-off periods such as the so-called ‘dark age’ (or what is often referred to as the ‘Kali Yuga’ in so-called ‘traditionalist’ thought), ‘golden age’ and ‘iron age’—, necessitate a declination narrative and mythic heroes to somehow turn the wheel of time. We see this particularly in the construction of the European Renaissance (or Rebirth). According to G.W. Trompf:

Conceived in its simplest form, the idea of renaissance entails a belief that a given set of (approved) general conditions constitutes the revival of a former set which had in the interim been considered defunct or dying. Although enriched by cyclical lines of thought (by the idea of successive civilizations, decomposition followed by rebirth, the Golden Age returned, etc.), it falls into a separate category, and its history reflects a complex interlacing of classical and Christian threads.26

As any historian of the medieval period will argue, the terms ‘Renaissance’ and even ‘Enlightenment’ impose a bias onto the past—portraying the time before the Renaissance as ‘dark’ or in decay. Indeed, cyclical interpretations of history have grave repercussions for the ways the general public understands the past, and potentially can affect the future. In this way, the past cannot be left in the past—trapping us with no escape into the future.

Refreshing and Reloading the Reconquest: An Alt-History

In the wake of the mass murder by a white nationalist terrorist targeting Latinos in El Paso, Texas in the summer of 2019, which resulted in 22 deaths and 24 injuries, Todd Starnes, the host of Fox Nation, argued, ‘I do believe that we have been invaded by a horde. A rampaging horde of illegal aliens. This has been a slow-moving invasion’. He continues to dehumanise refugees by calling them ‘violent criminals’—effectively depicting them as ‘Other’. In choppy sentence fragments Starnes argues:

When you go back in time and when you look at what an invasion is—whether it is the Nazis invading France and western Europe. I mean, whether the Muslims were invading a country back in the early years. It was an invasion.

In this example, Starnes decontextualises history and strings it together into fragments so that to leverage it as a weapon. His reference to ‘hordes’ recalls medieval fears of a Mongol invasion. He then pivots to compare invaders to the Nazis, who were proponents of ethnic cleansing and genocide. He then references Muslim invaders and thus the crusades or ‘reconquest’ of Spain. Effectively, his argument is that refugees and migrants are attempting to invade the West and will eventually ethnically cleanse the West—what far-right conspiracy theorists call ‘white genocide’. For Starnes, history is a weapon to be wielded to legitimate his far-right ideology, and worse, the acts taken by the El Paso shooter.27

To better understand how history is appropriated, revised and repurposed for nationalist purposes we can look at the long history of the Christian ‘Reconquista’ of the Iberian Peninsula. The Reconquista, or reconquest, recounts a myth that after 700 years of occupation, beginning in 711, ‘invading’ Muslims were expelled in 1492 by Isabel of Castilla and Fernando of Aragón, ‘the Catholic Kings’, after the fall of the Tarifa of Granada. While yes, Fernando and Isabel’s troops did indeed conquer Granada, the myth of the reconquest imposes an historical fiction onto Spain. Prior to 711, Iberia was a religiously diverse territory—even its Christian population was not monolithic. A ‘reconquest’ of Spain imposes a narrative that a Kingdom of Spain had once been a fact prior to the arrival of Muslims. In reality, Spain as a nation-state is a modern and contested construction. Integral to the creation of this history is the expulsion of Jewish people in Iberia—the Sephardi—whom had been in the peninsula since the beginning of the common era until their expulsion. In addition to expanding their conquest of the peninsula the Catholic Kings also demonstrated their religious extremism in the Americas, attempting to first enslave and then convert natives across the Atlantic to Catholicism. Obsessed with ‘limpieza de sangre’ [cleanliness of blood], a form of ethnic cleansing, the newly founded Kingdom of Spain became a model for colonisation and racialised and religious persecution.

This history of Reconquest, ‘taking back’ Muslim Spain is the foundational myth of the Spanish nation. At the centre of this Reconquest myth is Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar (c. 1043–1099), a mercenary and warrior nicknamed ‘El Cid’—a word derived from the Arabic ‘sayyid’, or ‘lord’ or ‘master’.28 El Cid was born to lower nobility, and centuries later became a symbol of Spanishness. However, as Richard Fletcher describes:

Figure 1.5 Statue of El Cid in Burgos, Spain. Botond Horvath/Shutterstock.com.

There is a disjunction… between eleventh-century reality and later mythology. In Rodrigo’s day there was little if any sense of nationhood, crusade or reconquest in the Christian kingdoms of Spain. Rodrigo himself… was as ready to fight alongside Muslims against Christians as vice versa. He was his own man and fought for his own profit.29

The reality of Rodrigo’s life and motivations, in fact, was quite different than the myths, histories and legends that followed his life. He was a mercenary for hire, as were many warriors of the period, with an Arabic derived nickname. El Cid fought battles with and against Muslims; however, popularly, El Cid’s image became a bellicose one associated with fighting against Muslim ‘invaders’.

Under the fascist dictatorship of Francisco Franco, images of Spanish greatness often referenced images of the ‘Reconquista’ and the ‘Conquest’ of the Americas.30 Of course, any scholarly understanding of those moments requires a reckoning with the deaths of millions and the expulsions of large parts of the Iberian population. The image of both the Christian Reconquest and the Conquest of the Americas was dependent upon an imagining of the past that simply never was but became accepted as truth by most Spaniards. The alt-history effectively replaced history itself—and still holds a strong grip on the country’s popular imagination.

In 1955, with the support of Franco, a statue by the artist Juan Cristóbal was erected to commemorate El Cid in Burgos, the largest town near where the warrior was born. Curiously, one article in A.B.C., the Falangist mouthpiece and Spanish newspaper of record, even hinted at one way in which the image of El Cid was invented, claiming: ‘The iconography of El Cid is completely imagined’—with the detail of El Cid’s beard coming only in the epic poem written about him, after the fact.31 Another contemporary article referenced the statue by Cristóbal as the ‘essence and spiritual example of Castilian lands’ and a ‘grand figure of the History of Spain’.32

Those invested in a narrative of a unified Spain, from the Catholic Kings to Francisco Franco, anchored their vision of the country to El Cid—a figure of the distant past who was decontextualised, appropriated and imbued with nationalist historical significance and meaning. Strictly speaking, to call El Cid a Spanish national hero demonstrates a clear example of an alt-history. There was no Spain in El Cid’s time. In the 1950s, the director of the Spanish Royal Academy, Ramón Menéndez Pidal, attempted to rescue El Cid’s narrative as one that was not specifically nationalist, but somehow rooted in a sort of nobility and patriotism. The hagiographic historian twists El Cid’s story yet again and calls it ‘democratic’ because it showed how lower ranking nobility could become legendary, he argues:

[E]l poema del Cid is not national because of the patriotism that it manifests, but better to say it is a sketch of the people where it was written. The most noble qualities of the people who made him their hero are reflected: love of family…; unbreakable fidelity; magnanimous generosity and haughtiness toward the King; the intensity of sentiment and the loyal sobriety of expression. The deeply national democratic spirit is incarnate in that ‘good servant who doesn’t have a good lord’, in that simple hidalgo [low-ranking aristocracy], who, unappreciated by high nobility and abandoned by his King, completes great deeds, and takes on all the power of Morocco and sees his daughters become queens… This genre of nationalism, less energetic, but more ample than the militaristic patriotism of Roland, can be felt more generally and permanently…33

Writing under Franco’s dictatorship, Menéndez Pidal simultaneously redefined ‘patriotism’ and ‘democracy’ so that to allow for Franco’s vision of Spain to survive in the post-Hitler era. In this way a nationalist war hero could be reimagined as a patriotic, democratic hero—an argument that could legitimate Franco to democratic Europe. El Cid, essentially, became a military leader, like Franco, who rose to power amongst an elite—thus somehow making him, and Franco, both patriotic and democratic—not a nationalistic leader who overthrew democracy and was responsible for hundreds of thousands of deaths. In 1961, Hollywood, too, fell for El Cid—with a blockbuster film by the same name starring Charlton Heston and financially supported by the Franco régime. El Cid’s narrative not only came to represent Spain internally, but became an international symbol of Spanishness.

The placement of Juan Cristóbal’s statue in Burgos was no coincidence, as the city was a stronghold for the Falange and Franco’s army during the Spanish Civil War and the Francoist period. In the Francoist narrative, Spain’s Civil War, the so called ‘War of Liberation’, was framed as a sort of ‘Reconquest’. Franco’s ‘War of Liberation’ did not expel Muslims and Jews, but was one that expelled, ostracised, imprisoned, murdered and exiled those from the political left, queer people and others who had taken Spain away from God and country. Despite the end of Franco’s regime and the establishment of the current democracy, by the early 2000s, the image of El Cid, and Burgos itself, had become a place where far-right skinhead ideology festered. One group in particular, Skinheads Burgos, even held a yearly ceremony at the statue of El Cid to celebrate the expulsion of Muslims and Jews from Spain—and recorded songs dedicated to El Cid. In fact, popularly, many, if not most, Spaniards believe this myth.

Today, thousands of tourists visit a weeklong festival dedicated to El Cid in Burgos. In this case, the alt-history created out of the fragments of El Cid’s life is celebrated both popularly and by the radical right. With this simple example, we see just how a historical person has become twisted into something clearly unrecognisable to history. Such is the fate of other such figures, like Joan of Arc, King Arthur, Richard the Lionheart, Roland and William Wallace. Even Abraham Lincoln, who waged a civil war to emancipate enslaved black Americans, has become a shield for a party that bears his standard only to deflect criticism of clearly racist ideologies. Lincoln once served as plausible deniability for a racist party; now, the dissonance is raw and out in the open.

Fighting Zombie Fascism: Queering and Decolonising the West34

Historians, activists and scholars of all disciplines must find new ways to turn these alt-histories, these distorted narratives, in on themselves. To make history less Eurocentric and heteronormative it is not only necessary to present a more accurate version of history but also necessary to prevent the far right from using it as a recruitment tool. Historians have talked about decolonising and queering national histories for decades now—especially those of former colonies. It is time to decolonise and queer European and American history and scholarship more broadly. We have to present pluralist histories of nations and peoples—stories forgotten or never highlighted—that clearly contradict far-right narratives. European history has always been pluralistic. By more fully demonstrating pluralism already present in the history of Europe, based on historical fact and analysis, we can show that the alt-histories the far right utilise to legitimate their own power are fictions—whether a belief in a homogenous European past or an attempt to make America Great Again.

Recently, Javier Ortega Smith, the leader of the Spanish far-right party, Vox, came under scrutiny for language that Spanish Attorney General Luis Navajas called ‘abominable’ and ‘repulsive’ although not a hate crime.35 Ortega Smith claimed:

Our common enemy, the enemy of Europe, the enemy of liberty, the enemy of progress, the enemy of democracy, the enemy of family, the enemy of life, the enemy of the future is an invasion, an Islamic invasion… What we know and understand as civilization is at risk.

Ortega Smith called upon old concepts of ‘western civilisation’ and the so-called Spanish Reconquest that have long been used to mask hate and excuse violence.

Historically, being ‘western’ or ‘civilised’ was a powerful weapon used to legitimate the domination of others who were not of the elite or were outside Europe. Despite the fact that the first recorded civilisations or settled groups of people began in ancient Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq, the promise of ‘civilisation’ somehow became the provenance of Europe alone. The promise of ‘Western civilisation’ became an excuse to dominate—to ‘civilise’ others. In the Spanish case, this was readily made apparent in the encomienda system that systematically enslaved native populations in the Americas. Other European colonial powers adopted similar rationales for their empires; it became ‘the white man’s burden’ to spread Western civilisation. Of course, native populations in the Americas and elsewhere already had civilisations long before Europeans arrived, and were rarely admitted as part of the Western club.

In the aftermath of the First World War, the German academic Oswald Spengler wrote The Decline of the West, a work that demonstrated racist and proto-fascist tropes as it decried the fall of Western civilisation and underlined the importance of strengthening blood ties in order to save the West. This fear of the fall of the West later popped up again during the Cold War and even in the aftermath of the 2001 attacks in the United States.36 Powerful countries seem to need to summon up a millenarianism, sounding the death of the West in moments of anxiety about the loss of power, while also using a desire to renew the nation to legitimate their power—reifying their position in the world.

Figure 1.6 The secretary general of the Vox extreme right party, Javier Ortega Smith, in Pamplona, Spain places a Spanish flag on the lectern in November 2018. MiguelOses/Shutterstock.com.

More recently, in 2016, Gavin McInnes, a co-founder of VICE Media, began a men’s exclusive group called the Proud Boys.37 On the Proud Boys’ website, they declare that they accept people of ‘all races’, ‘all religions’, ‘gay or straight’. However, to join the Proud Boys one must ‘be a man’ and ‘must love the West’. One video featured on their website claims that all the Proud Boys care about is that one believes ‘the West is the best’.38 The group is composed of self-proclaimed ‘Western chauvinists who refuse to apologize for creating the modern world’. McInnes has described a chauvinist as simply being ‘a nationalist, a patriot’. McInnes conflates nationalism and patriotism—pride in one’s country as opposed to the belief in the superiority of that nation in a way not dissimilar to Ramón Menéndez Pidal’s usage 70 years earlier to legitimate Franco’s dictatorship. McInnes’s broad category of ‘western chauvinism’ translates to a type of Western nationalism akin to ‘European nationalism’—a concept that might read as ‘white nationalism’—without being entirely obvious. Indeed, these chauvinistic ideals are a direct product of Western ideologies. They represent the West’s most horrendous legacies: fascism, patriarchy and colonialism.

The Proud Boys’ website also claims the group confuses ‘the media because the group is anti-SJW without being alt-right’. This claim to be ‘anti-Social Justice Warrior’ is curious, as it most often refers to those who are interested in promoting civil rights and pointing out injustices, regardless of one’s race, gender, class, nationality or embodiment. When the so-called social justice warriors (SJWs) point to social inequality because of discrimination, it is an attempt to have human rights recognised—an ideal embedded in Enlightenment thought. Even the Proud Boys’ desire to dubiously claim to not discriminate because of race, sexuality or religion is a product of the Enlightenment. Of course, for the group, there seems to be a complete lack of understanding about what the Enlightenment was, including the importance of seeking redress for injustice from a democratic government, as well as a complete lack of interest in what equality means today. The so-called SJWs, in reality, represent what might be the most important ideals of Western thought that stretch from Rousseau to Angela Davis.

Meanwhile, the ‘men-only’ exclusivity of the Proud Boys is a clear demonstration of chauvinism against women. The Proud Boys’ reactionary website is against women and denies the existence of transgender people, stating: ‘Our group is and will always be MEN ONLY (born with a penis if that wasn’t clear enough for you leftists)!’ Women can, however, join the group as ‘Proud Boys’ Girls’. But even in the women’s group name they are subordinate, belonging not to their own group, but to the boys themselves.

Both Ortega Smith and the Proud Boys’ versions of Western civilisation reject the Western ideals that are worth defending—a belief in equality, the value of individual and the responsibility of the government to its people. Their visions of the West simply cannot co-exist along with the best hopes for the Enlightenment project. Of course, the best parts of Enlightenment ideals have rarely been a reality, but they are still admirable goals for which to strive. In fact, what we see with both examples is an alt-history of the history of Europe, which has long been competing against the more critical analysis of what the West means. This alt-history has been attempting to replace the actual history of the Europe—replacing history with an alt-history which would legitimate the atrocities committed in the name of Western civilisation.

For decades, historians have argued fascism was a thing relegated to the dustbin of history. With threats from far-right parties such as Golden Dawn, Alternative für Deutschland, Sweden Democrats, Vox, Lega Nord, Casa Pound and far-right leaders such as Donald Trump, Jair Bolsonaro, Vladimir Putin, Viktor Orbán, Marine Le Pen, Matteo Salvini and Boris Johnson, it is clear that far-right fascistic parties and ideologies have returned to the mainstream. With mass shootings perpetrated by the likes of Anders Behring Breivik, Dylann Roof, Brenton Tarrant and Patrick Crusius—the list goes on and on—, we are witnessing what can be described as an attack on the pluralistic, democratic public sphere.39 On the internet, one need not go further than 4chan, YouTube and comment sections of major newspapers to find malicious attacks against women, immigrants, refugees and queer people—even plotting their murder. As this book will show, far-right ideologies and actions are fundamentally legitimated by their misinterpretations of historical facts and those deformations into alt-history—a bait-and-switch claiming to be legitimate history.

Today, refugees—many children—are living in cages in the United States in ‘detainment’ centres. Based on a belief that cleansing the United States of immigrants will somehow ‘Make America Great Again’, immigrants are being demonised as criminals and rounded up and sent to these camps before deportation. A form of fascism has clawed its way back to the mainstream. This zombie fascism is one that we are hesitant to recognise as fascism; in some ways it is more gnarly and in others it is more aesthetic—covering something ugly with flashy branding. Fascism was supposed to be dead—with the exception of some fringe elements. It was never dead but was undead. It just crawled underground and waited. To admit that fascism has indeed taken hold of democratic governments and democratically minded people is to acknowledge that the West has failed at stopping fascism—despite those democracies’ promise to ‘never forget’. Only once we accept that this has happened, once we confront our histories, can we be in a better place to better uproot fascism entirely by depriving it of the alt-histories and nostalgia for a past that never was that give it oxygen.

Notes

1 According to José Pedro Zúquete,

The Identitarian indictment is a dark account of contemporary European life. Europe has been torn apart by the Western model of civilization that it helped to create, which today is synonymous with Americanization, and this dominant ideology—which in this new century bears the name globalism—has diluted its distinctive character. Its communities, peoples, and cultures have suffered the onslaught of an abstract model that homogenizes all differences, and combats all natural attachments (to nations, regions, cultures, ethnicities), in an attempt to destroy all barriers to the free flow of markets, reducing human beings to a sorrowful condition in which the only identity that is allowed, and celebrated, is that of individual materialism and consumerism.

He continues,

[S]o goes the Identitarian accusation, European elites allowed the “opening of the gates,” the decades-long policies of mass immigration, which softened and corrupted the relatively coherent and homogenous collective identity of European peoples, constituting a major dimension of the self-immolation of the continent’. The more recent surge of immigration or invasion—whose participants the official of thinking and its zealots labelled ‘migrants’—added fuel to this on-going ‘Great Replacement’ of peoples in European lands. Amid the degradation of its identity, the abjuration of its ancient Indo-European and Hellenic roots, feeling guilty about its own history, and awash in relativism, self-doubt, and self-loathing, Europe is on the verge of being conquered by Islam, a young, rooted, and spiritually strong civilization that is superior to an aging and frail Europe whose treacherous elites are behaving in a manner that is the greatest expression of a civilization in free fall.

See: José Pedro Zúquete, The Identitarians: The Movement against Globalism and Islam in Europe (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2018), 2.

2 blocidentitaire, ‘Génération Identitaire—clip de lancement sous-titré en anglais’ YouTube, accessed 5 January 2019, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B4e7n7g1xAM.

3 John Boswell, Same-Sex Unions in Premodern Europe (New York: Vintage Books, 1995), 88.

4 Just a few examples include: Camp Beauregard, Fort Benning, Fort Bragg and Fort Lee.

5 G.W. Trompf, The Idea of Historical Recurrence in Western Thought: From Antiquity to the Reformation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979), 4–59.

6 In his writings, Evola often appropriates and uses terms from Hindi due to a belief that Eastern cultures have somehow maintained their traditionalism better than the West—using terms such as: satya yuga, treta yuga, dwapara yuga and kali yuga. That said, far-right thinkers readily appropriate ‘traditionalist’ ideas from non-European countries as long as they reinforce oppressive and hierarchical power structures. Indeed, appropriation from Eastern cultures was present in Nazi occult ideology, including the use of the swastika.

7 Theodore E. Mommsen, ‘Petrarch’s Conception of the ‘Dark Ages,’” Speculum 17, no. 2 (April 1942): 226–42.

8 Julius Evola, Ride the Tiger: A Survival Manual for the Aristocrats of the Soul, trans. Joscelyn Godwin and Constance Fontana (Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 2003), 2–13.

9 Melissa Rossi, “Terror Attacks like El Paso Aim to Topple the Government, Experts Say,” Yahoo News, 6 August 2019. Archived 6 August 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20190806150148/https://news.yahoo.com/terror-attacks-like-el-paso-aim-to-topple-the-government-experts-say-145010800.html.

10 Timothy Snyder, The Road to Unfreedom (New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2018), 8.

11 Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (New York: Free Press, 1992), 42.

12 Ibid., 47.

13 Ibid., 48.

14 Ibid.

15 The Dave Pakman Show, ‘White Nationalist Alt-Right Richard Spencer Sucker Punched, Won’t Denounce Hitler, Talks Jews’, YouTube, accessed 6 September 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=0cKNhjQHWFo.

16 Oliver Willis, ‘White Nationalist Group Headed By “Peaceful Ethnic Cleansing” Leader Holding Pro-Trump Conference in D.C.’, Media Matters (blog), 3 March 2016. Archived 29 April 2017. http://web.archive.org/web/20170429012612/https://mediamatters.org/blog/2016/03/03/white-nationalist-group-headed-by-peaceful-ethn/208996.

17 Mark Mazower, Dark Continent: Europe’s Twentieth Century (New York: Knopf, 1999), 42.

18 Joe Heim, “National Archives exhibit blurs images critical of President Trump,” The Washington Post, 17 January 2020, www.washingtonpost.com/local/national-archives-exhibit-blurs-images-critical-of-president-trump /2020/01/17/71d8e80c-37e3-11ea-9541-9107303481a4_story.html.

19 See Chapter 16 of this volume, ‘The Rise and Fall of the Far Right in the Digital Age’.

20 Dinesh D’Souza, a former Reagan advisor, has also has made claims such as ‘the American slave was treated like property, which is to say, pretty well’, see Dinesh D’Souza, The End of Racism: Principles for a Multiracial Society (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995), 91.

21 Quoted in Dinesh D’Souza, The End of Racism, 3. pr, 91. Simms’s book was published as Hitler: A Global Biography (Basic Books, 2019) in the United States and Hitler: Only the World Was Enough (Allen Lane, 2019) in the United Kingdom.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24 See Deborah E. Lipstadt, Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory (New York: Free Press, 1993).

25 Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, Religion and Postmodernism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996).

26 Trompf, The Idea of Historical Recurrence in Western Thought, 248.

27 Edward Helmore, “Fox News Host Compares Migrants Entering US to Nazis,” The Guardian, 15 August 2019, https://web.archive.org/web/20190815142233/https://www.theguardian.com/media/2019/aug/15/fox-news-nation-todd-starnes-migrants-nazis-invasion.

28 Richard Fletcher, The Quest for El Cid (New York: Knopf, 1990), 3.

29 Ibid., 4.

30 I have previously argued Franco’s dictatorship was fascist, see Louie Dean Valencia-García, Antiauthoritarian Youth Culture in Francoist Spain: Clashing with Fascism (Bloomsbury Academic, 2018).

31 ‘La estatura del Cid,’ ABC (Sevilla), 10 May 1955, 11.

32 ‘El monumento para perpetuar la reivindicación española de Gibraltar tendrá cinco metros de altura,’ ABC (Madrid), 8 May 1955, 13.

33 See Ramón Menéndez Pidal’s Introduction in (ed.), Poema de mio Cid (Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1958), 95–7. ‘[E]l poema del Cid no es nacional por el patriotismo que en él se manifieste, sino más bien como retrato del pueblo donde se escribió. En el Cid se reflejan las más nobles cualidades del pueblo que le hizo su héroe: el amor a la familia…; la fidelidad inquebrantable; la generosidad magnánima y altanera aun para con el Rey; la intensidad del sentimiento y la leal sobriedad de la expresión. Es hondamente nacional el espíritu democrático encarnado en ese ‘buen vasallo que no tiene buen señor’, en ese simple hidalgo, que, despreciado por la alta nobleza y abandonado de su Rey, lleva a cabo los más grandes hechos, somete todo el poder de Marruecos y ve a sus hijas llegar a ser reinas…. Este género de nacionalismo, menos enérgico, pero más amplio que el patriotismo militar del Roland, puede ser sentido más general y permanentemente y podrán repetirse siempre las palabras de Federico Schlegel: ‘España, con el histórico poema de su Cid, tiene una ventaja peculiar sobre otras muchas naciones; es éste el género de poesía que influye más inmediata y eficazmente en el sentimiento nacional y en el carácter de un pueblo. Uno solo recuerdo cómo el del Cid es de más valor para una nación que toda una biblioteca llena de obras literarias hijas únicamente del ingenio y sin un contenido nacional’.

34 Parts of this section were adapted from a more pedagogically focused article published in openDemocracy, see Louie Dean Valencia-García, ‘The Ups and Downs and Clashes of Western Civilization’, 23 July 2019, https://web.archive.org/web/20190906170927/https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/countering-radical-right/ups-and-downs-and-clashes-western-civilization/.

35 Manuel Marraco, “La Fiscalía No ve Delito de Odio En Las ‘Abominables’ Palabras de Javier Ortega Smith Sobre El Islamismo,” El País, 3 July 2019, https://web.archive.org/web/20190906210513/https://www.elmundo.es/espana/2019/07/03/5d1c7f80fdddffec758b45e7.html.

36 Edward Said, “A Window on the World,” The Guardian, 1 August 2003, https://web.archive.org/web/20130827055201/https://www.theguardian.com/books/2003/aug/02/alqaida.highereducation.

37 For more on the Proud Boys, see Alexandra Stern, Proud Boys and the White Ethnostate: How the Alt-Right Is Warping the American Imagination (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2019).

38 Ozia Media, ‘Who Are the Proud Boy in 60 Seconds’ YouTube, accessed 5 February 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=k6wJa7FltyQ.

39 For a breakdown of a far-right terrorist incident and the ways Islamophobia functioned to motivate that attack see Sindre Bangstad, Anders Breivik and the Rise of Islamophobia (London: Zed Books, 2014).