15 Esoteric Fascism Online

Marc Tuters and the Open Intelligence Lab

Since the early 2010s, fringe web culture has brought a number of peculiar far-right intellectual traditions into the ‘mainstream’ web. Whilst Jordan Peterson and other ‘modern philosophers’ of internet culture are considered gateways into the so-called ‘alt-right’ style that has taken over a number of social media platforms, some of the trending ideas in these discussions may be understood as having a more subcultural derivation which, upon closer inspection, also appear to draw on Western esotericism and other obscure traditions in the history of political thought. Having come to international attention during the period of the 2016 United States presidential election, as a movement, the alt-right have been said to draw their creative energies from underground ‘meme culture’, in which expressions of political belief are veiled in layers of irony and transgression.1 As our previous research has demonstrated, during this period of time there appeared to be a relationship of influence moving from the ‘fringe’ to the ‘mainstream’—whereby far-right imagery that had originated in political discussion forums on websites like 4chan would regularly show up in people’s social media feeds.2

In relation to the allegation that ‘the real creative energy behind the new right-wing sensibility online today springs from anonymous chan culture’, there have been countless journalist exposés and academic studies on apparent mainstreaming of far-right style.3 In dialogue with this literature, this chapter takes a somewhat different approach, in that it proposes to reconsider how it is that ‘anonymous chan culture’ engages in alternative readings of the historical past, or what the introduction of this volume describes as ‘alt-history’.4 The argument here is that anonymous chan culture can be understood as giving a contemporary ‘vernacular’ form to a long tradition of post-war far-right political thought. As elaborated upon by a number of historians of the far-right as well as of esotericism,5 this tradition involves a combination of anti-modernism, aristocratic elitism and Aryan esotericism with a peculiar cocktail of what historian Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke refers to as ‘esoteric fascism’. There is nothing especially new about this phenomenon. As Goodrick-Clarke notes in his study of the neo-Nazi new religious movements that emerged in the United States and Europe in the aftermath of the sixties counterculture, a preoccupation with occult symbology and apocalypticism as well as anti-Semitic demonology and hatred of the ‘dark races’ are all symptomatic of a far-right underground aesthetic that has been thriving in underground print zine culture for decades. What has changed is the medium for the circulation of these ideas. Whilst in the past the reach of these subcultures was relatively limited, through the medium of internet memes these ideas potentially acquire a much broader reach.6

On the ‘politically incorrect’ online discussion boards of 4chan and the now defunct 8chan (both of which have been associated with acts of extreme violence in recent years), one regularly encounters political discussions that are framed in terms of dark imaginings of the past. In keeping with the often conspiratorial nature of discussion on these sites, these histories tend to be distinctly esoteric, both in the general sense that they offer to reveal ‘secret’ or stigmatised knowledge to initiates and more specifically in terms of the concepts and aesthetics with which they are framed.7 On these chan boards, as well as on other social media platforms, occult symbols such as the Black Sun, which had been in use amongst Aryan and Satanist subcultures for decades, are combined with contemporary subcultural web aesthetics of ‘vaporwave’ images (nostalgic for an imagined cyberpunk past future), in order to create a new genre of so-called ‘fashwave’ memes (see Figure 15.1). As the outward manifestations of a renaissance of esoteric fascism online, ‘fashwave’ may arguably be understood as a successful instance of far-right ‘metapolitics’ (a Gramscianism strategy which has been much discussed over the course of many decades by intellectuals associated with the European New Right that proposes a strategy of not only being political, or affected by politics, but steering political language to reflect a particular ideology). The vernacular shorthand for having subscribed to this far-right project of metapolitics is called ‘taking the red pill’, a term popularised within the alt-right which refers an esoteric experience of awakening from the induced somnambulism of liberal mainstream society—a conspiratorial notion of awakening is also distinctly liminal feature of the late countercultural spiritual underground that one scholar of this milieu has referred to as ‘high weirdness’.8

A well-known pop-cultural reference to the film The Matrix (1999) in many parts of the web, taking the red pill has become contemporary shorthand for a kind of right-wing ideological critique (Lovink and Tuters 2018). If left-wing ideology critique offers its subject ‘to face with sober senses, his real conditions of life’ (Marx and Engels 1848), then the red pill similarly presents its subject with unpleasant truths which those sleepwalking through disregard. It follows that being confronted by this shockingly brutal alternative reality implies locating oneself in a different historical timeline and alt-history. As this chapter will explore, through the eyes of much of radical right political culture on 8- and 4chan/pol/, this involves the esoteric rediscovery of the supremacy of European culture (which often equates with ‘white’ culture) that has been usurped by a cabal of enemies working in consort to bring about its demise. In what follows we observe how the anonymous denizens of these niche web fora (so-called ‘anons’) interpret this awakening as a radical call to arms. It is here, in anons’ engagement with the ideas of esoteric fascism, that we also find a degree of continuity between anonymous chan culture and those neo-Nazi new religious movements that preceded them. The objective of this chapter is thus to scrutinise how it is that anonymous chan culture engage with the alt-histories of esoteric fascism. To this end, the chapter begins with a brief description of the ideas of the mid-century Italian esotericist ‘Baron’ Julius Evola (arguably the single most significant intellectual influence on esoteric fascism), before moving on to discuss anon’s vernacular interpretation of these ideas. In order to assess the ‘real world’ danger posed by these alt-histories, the chapter concludes with a brief analysis of the particularly disturbing case of the Christchurch mass shooter whose manifesto was replete with references to anonymous chan culture and whom appears to have imagined himself as a holy warrior engaged fighting against ‘the great replacement’ of Western culture by alien outsiders—a notion which connects extreme-right terrorists with the discourse of new-right populist politicians and intellectuals.9

Evola and Esoteric Fascism

In the current right-wing populist political climate, we can find expressions of the alt-histories of esoteric fascism resonating between the margins and the mainstream, as prominently seen in references to Evola by former White House Chief Strategist Steve Bannon.10 An arguable case in point involves the leader of the Forum voor Democratie party, Thierry Baudet, who delivered a controversial speech, whereupon he described Dutch citizens as standing ‘amid the debris of what was once the most beautiful, the greatest civilization the world has ever known’11 and one that ‘just like those other countries of [the] boreal world, […] are being destroyed by the people who should protect us’.12 Baudet was questioned by Dutch television host Robert Jensen for using the term ‘boreal’ and responded by claiming that he was being ‘poetic’.13 If we take Baudet at his word, how are we to interpret his poetry? The most charitable interpretation would be that Baudet used this term to frame a clash of civilisations narrative in poetic terms. In this charitable interpretation, ‘boreal’ is a code-word, or dog-whistle, for ‘northern-European’, or simply Aryan. Consistent with this interpretation, it has been argued that Baudet was in fact flirting with the alt-right narrative of ‘white genocide’ or ‘replacement’, which finds liberal multiculturalism guilty of destroying the patrimony European heritage.14 In fact, boreal is actually a term from forestry with no prior history of use in political communications—apart from having once been used once by Marine Le Pen to speak of his desire for a ‘white world’.15

An etymologically similar term which refers to Northern European countries as the birthplace of the Aryan race, hyperborean, can however be found in esoteric fascist literature.16 An apt term for what Baudet’s use of the term boreal might be twilight language, a Sanskrit concept for a style of esoteric communication incomprehensible to outsiders, which is intended to ensure that the uninitiated do not easily gain access to secret knowledge. Whatever his intent, Baudet, who holds a PhD in law, and has a track record of exchanging ideas with far-right thinkers, intended to express the desire to evoke a sense of apocalyptic foreboding whilst calling for the renewal of the social bonds of an organic community in which everyone has their correct place in the broader scheme of things. In this regard, Baudet’s message of apocalyptic foreboding and renewal may be seen as in line with the so-called metapoliticisation of fascist discourse, which has taken place in the post-war period, largely through its reformulation via intellectuals of the European New Right.17 Seemingly in line with this neo-reactionary discourse, Baudet himself once allegedly admitted that conservatism—the school of thought he chose to associate his party to—was the tradition of the ‘losers of history’ (Kleinpaste 2019). Venerating the likes of Julius Evola, Friedrich Nietzsche, Carl Schmitt, Oswald Spengler and Martin Heidegger, amongst others, intellectuals of the European New Right have come to reformulate the Manichaean enemy of fascist ideology in terms of a genocidal ‘mondialisme’ set to destroy the indigenous character of European culture through the tool of mass migration. As Roger Griffin notes, many on the European New Right have drawn a theory of history from Julius Evola choosing to view themselves as dwelling in the apocalyptic Kali Yuga on the threshold of a new golden age of history. As Nicholas Goodrick-Clark notes, in the post-war period, Evola’s ideas became a sophisticated alternative to crude Anglo-American neo-Nazism in which Nazi creed became reformulated as white supremacist ideology.

Evola’s theory of history worked well for this purpose, as it required elite males to channel the masses towards the creative destruction of the dominant decadent political system of liberalism. For Evola, those in the know had to cultivate themselves to ‘promote the aims of race’ so long as it were undertaken ‘in the presupposition of a right spiritual attitude’ meaning that it brings about ‘racial values in the consciousness of a people’.18 Evola’s idea was that of the ‘kshatriya’ described by Krishna in the Hindu Bhagavad Gita: a kind of righteous religious warrior with an aristocratic attitude who fights to defend the higher principles of his community and his existence (his dharma). Whilst he felt that few genuine kshatriya were to be found in the kali, he valorised ‘the “ordeal by fire” of the primordial forces of race heroic experience, above all other experience… [as] a means to an essentially spiritual and interior end’.19 He thus considered the ‘awakening through heroic experience’ as a path to enlightenment: ‘this mostly naturalistic experience is purified, dignified, becomes luminous, until it reaches its highest form, which corresponds to the Aryan conception of war as “holy war”’.20

Beginning his career as an aristocratic avant-gardist affiliated with the Italian Futurist movement, Evola soon turned his attention towards philosophy and occultism, producing a body of work that sought to embrace traditionalism and thereby reject modernity, egalitarianism, democracy and liberalism. Evola’s esoteric theory of ‘racial values’ came to influence Mussolini’s regime, with which he was briefly affiliated. As Goodrick-Clark notes, Evola’s aura as fascist sage was however untainted by Mussolini’s fall, and indeed he went on to have a prominent influence on the far-right in post-war Italy as an ‘oracle of violence and revolution’,21 being charged with plotting to re-establish fascism in the early 1950s and eventually came to be considered as the far-right’s answer to a Herbert Marcuse-like figure for his influence on right-wing terrorism in the late 1970s, including the notorious 1980 Bologna railway station bombing.22 In spite of his influence, in his later years Evola in fact turned away from political activism arguing that an apolitical stance, what he called ‘apoliteia’, was the only appropriate attitude for the traditionalist in the Kali Yuga. In Evola’s estimation, Mussolini and Hitler had failed because they had been too nationalistic and ultimately too modern. Already before the war, Evola rejected Christianity as proper basis for fascism in favour of paganism, cultivating his idealised past in the pre-Christian Roman Ghibelline culture. Whilst paganistic and anti-Christian themes had had a certain influence on mid-century fascism (notably in the Thule society which partly fed into the Nazi movement as well as to a certain extent on members of the Schutzstaffel, or SS) neither Mussolini nor Hitler had much real sympathy for esotericism. Rather, as Goodrick-Clark notes, this whole narrative of esoteric fascism was a distinctly post-war creation pieced together in part out of Evola’s ideas, which proposes an alternate to mid-century fascism, which contemporary far-right actors have used to infuse a once moribund ideology with an aura of seemingly deep spiritual significance.

Evola drew his theory of history from Hindu cycle of the ages in which the Kali Yuga represents the fourth dark age of decline. One of the reasons that he turned towards Hinduism was for what he considered to be its strict hierarchical idealism which he saw as fundamentally opposed to the materialism of the modern West. To this end Evola placed great import in the traditional Hindu caste system as the basis of his race theory, which he tried to distinguish from the modern ‘biological conception of race’—the latter which he identified with the Nazis. Rather, Evola was in favour of what he called an esoteric ‘racism of the second and of the third degree’ in which race exists

not only in the body, but also in the soul and in the spirit as a deep, meta-biological force which conditions both the physical and the psychical structures in the organic totality of the human entity – it is only if this eminently traditional point of view is assumed – that the mystery of the decline of races can be fathomed in all its aspects.

Evola’s overarching reactionary theory of history sought to restore the primal truth and order at the cores of what he saw as traditional Western civilisation, the loss of which constituted a crisis for the West. Variations on Evola’s notion of a race as spiritual-biological community have come to play a significant role amongst certain variants of neo-Nazi ideology, notably in writings of Francis Parker Yockey as well as in the Aryan and Satanist movements in the United States in 1970s. In particular, the Aryan movement sought to project this religious Manichaeism onto what was seen as biological difference, thereby interpreting human groups as ‘absolute categories of good and evil, light and darkness’, constructing for themselves what Goodrick-Clark memorably refers to as a ‘spiritual basement of a primitive dualism, where pseudo-salvation depends on the elimination of the Other’.23

Evola developed an extremely arcane view of Western history as one long narrative of decline. In order to develop the idea of an Aryan Absolute Individual,24 his traditionalist declension narrative required an Eden from which to fall, which he referred to as Hyperborea. In this regard Evola’s ideas resonated with the notion of an ancient Aryans polar homeland—an esoteric idea that had been popular within the pre-Nazi völkisch—in particular amongst members of the Thule society, whose membership list including prominent future Nazis such as Rudolf Hess and Alfred Rosenberg.25 In order then to restore the Aryan Absolute Individual required an undoing of the processes of devolution of the Ur-species, the latter which Evola imagined in gendered terms as a process of effeminisation. Repackaged in a new cultic guise that borrowed heavily from Evola, what emerged in the post-war era was the concept of the Nazi occult which included neo-Gnostic orientalism, secret Tibetan doctrine and other demonic inspiration. This new ‘neo-Nazi’ movement viewed Hitler as a kind of Gnostic avatar in their struggle against the forces that also bedevilled Evola (modernity, liberalism and above all ‘the Jew’). Following Evola’s preoccupation with Hinduism, Miguel Serrano’s rather arcane concept of ‘Esoteric Hitlerism’ for instance blends Gnostic-Manichaeanism with kundalini yoga, a kind of contemporary variant on the fourth-century cult of tantra which sought to cultivate magical powers in its adepts through a variety of spiritually dangerous practices intended to raise ones consciousness to supreme levels of unity.26

The anti-modern ‘völkisch’ defence of German identity against the forces of liberalism is generally seen as a precursor to Nazism. To this end, Goodrick-Clark sees certain parallels between the anxiety that gripped parts of Germanic Europe at the turn of the last century, which fed into the growth of the first wave of Aryanian occult philosophy, and the contemporary period. Furthermore, he points out that today’s white-pride movements should be understood as the ‘only most radical response’ to globalisation in which ‘white’ European races population have declined by 20% in the past century. As Evola is experiencing yet another renaissance, his contemporary readers in the alt-right see his ideas as offering ‘an alternative to the seemingly unstoppable, global speech of democratic capitalism’.27

Holy White War

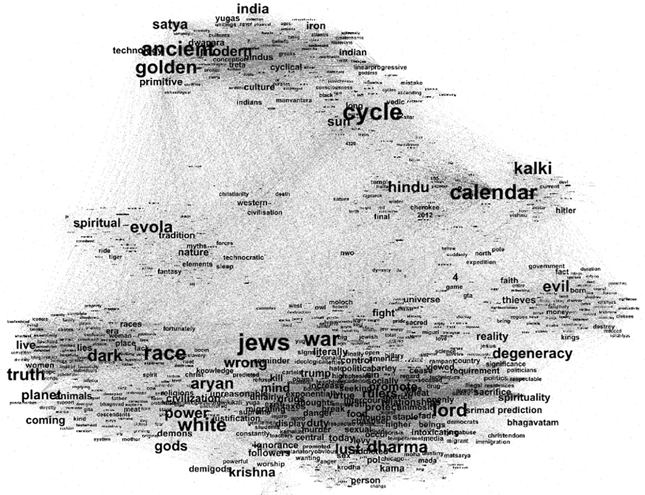

On 4chan/pol/ esoteric ‘Evolite’ uses of concepts such as ‘Hyperborean’ and ‘Kali Yuga’ have become deeply entwined in the broader apocalyptic discussions concerning the crisis of the Borean ‘white world’, as evoked by right-wing populist. The outcome of a collective research project conducted over the course of two weeks in the summer of 2019, Figure 15.2 below, represents words and concepts that frequently occur alongside Kali Yuga from a database of over 7,000 posts on 4chan/pol/ dating from 2013 to 2019. In this graph the word ‘evola’ appears to form the core of a noteworthy cluster of terms alongside words such as ‘jews’, ‘whites’, ‘race’ and so on. Upon closer inspection one notices a larger cluster in the bottom of the graph which signifies a group of words (activities) associated with the degeneracy that occurs during the Kali Yuga. Adjacent, on the left, is a cluster of ethno-nationalist associations. This cluster of words can be understood to represent the idea that, for the anonymous Evolites in discussion on /pol/, the Kali Yuga does not signify a decline for all humanity, but rather a failure of ‘The West’ to preserve its own roots and identitarian history.28 Through this interpretation, which appears generally consistent with Evola’s political theories as discussed earlier, discussion of the Kali Yuga is also a call to arms. A final relevant cluster is that of the ‘Kalki’ (right-centre), another Hindu term which refers to the avatar of the holy war at the end of the current cycle of history, who brings the Kali Yuga to a close thereby ushering in the new era of historical renewal. From the perspective of Evolite esoteric fascism, this would represent the return of the white world to its former status of hegemonic supremacy.

Figure 15.2 Word collocations with the term ‘Kali Yuga’ in all the comments mentioning ‘Kali Yuga’ on 4chan /pol/ from 2013 to 2019. The image was produced by Ivan Kisjes, using research by Daniel Jurg, Jack Wilson, Emillie de Keulenaar, Giulia Giorgi, Marc Tuters, Ivan Kisjes and Louie Dean Valencia-García; the size is based on frequency as visualised within Gephi, developed by Bastian et al. (2009).

Extracting all images in the comments mentioning the term ‘Kali Yuga’, as seen in Figure 15.3 below, offers some insight into anonymous chan culture’s vernacular interpretation of this arcane tradition of alt-historiography. In addition to Hindu imagery one finds a cartoon image of an orientalised Adolf Hitler. In reading the posts associated with these images one finds both Hitler and the US President Donald Trump frequently mentioned as ‘the Kalki’, with the period of the Third Reich often times discussed as an intentional attempt to ‘end’ the Kali Yuga and re-establish the ethnostate.29 The association with the Third Reich is furthermore entrenched with the use of the ‘Black Sun’ symbol, an iconographic image of a wheel with 12 zigzag spokes.30 Finally, one of the more frequent images is a vernacular interpretation of a traditional Hindu depiction of Kalki with the head of Pepe the Frog meme, the latter which has come to be seen as the avatar of anonymous chan culture widely considered to be an ‘ironic’ symbol of alt-right white supremacy.31 This image of Kalki Pepe encapsulates the relatively unique ‘ironical’ tone through which anonymous chan culture launders esoteric fascism for a new audience.

The Christchurch Killer and Alt-History

In recent years, then, the anonymous chan boards have become bastions of a newly ironic form of white supremacist ideology—though it should be noted that they have not always been this way.32 Recent research has, for example, documented the prevalence of explicit neo-Nazi propaganda on 4chan/pol/.33 Whilst the political discussion of anonymous chan culture can also be understood in relation to a subcultural history of trolling whose aim is to upset and offend those who make the cardinal error or taking themselves too seriously,34 in the years since the rise of the alt-right, this culture has been increasingly associated with mass shootings in which perpetrators post their ‘manifestos’ to these boards. Whilst ‘de-platforming’ appears to be a solution—indeed 8chan’s web hosting was for example terminated in the aftermath of a mass shooter having posted his manifesto to the site35—the question of how to assess the threat posed by these sites looms large. For those concerned with countering the urgent problem of far-right violence then the essential problem is in determining the transition from being an online troll into becoming a ‘real-world’ extremist. In closing we thus turn to the case of the Christchurch, New Zealand shooter, whose actions appear (at least upon first glance) to act out the ‘chan’ fantasy world of esoteric fascism, with the most tragic of consequences. In doing so, we may thus inquire into whether (and to what extent) the Christchurch shooter’s actions can be understood as a reflection of the esoteric fascist preoccupations of 4chan’s ‘keyboard warriors’.

Before murdering 50 congregants in two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand in March 2019, the shooter posted a manifesto to 8chan/pol/. The title for the manifesto, The Great Replacement: Towards a New Society, echoes themes in mainstream right-wing populist politicians as well as thinkers on the European New Right which argues for the defence of a supposedly autochthonous European culture from hostile incursion by alien forces working in cahoots with liberal elites. Consistent with how the shooter sought to frame his own actions in the manifesto, he has largely been treated as an avatar of chan culture. Indeed, his manifesto was replete with sly references to chan culture from slang expressions — such, for example, as his repeated use of the ‘kebab’ as slur against Muslims — to his seemingly baffling claim that he was red-pilled by YouTube conservative pundit Candace Owens. As researchers more literate in chan culture have noticed, the manifesto may also be read as an instance of what is colloquially known in chan culture as ‘shitposting’ — referring to an exercise in media manipulation, which in this case was calculated to instil the idea that the shooter’s actions were symptomatic of alt-right anonymous chan culture in general.36 Some media coverage of the event simply ignored the killer’s framing of his actions, following the lead of the members of the New Zealand government, who refused even to mention his name—an approach referred to as ‘strategic silencing’.37 In spite of this strategy, the killer’s actions have very much become part of the mythos of anonymous chan culture where his name and likeness have become literally canonised, providing inspiration for others—indeed the subsequent El Paso mass shooter said as much in his own manifesto, a four-page document also posted to 8chan.

In the aftermath of the 2019 killings tied to 8chan, these killers appear to many as an embodiment of the toxic subculture of contemporary anonymous chan boards. Whilst the Christchurch shooter did aim to create the impression of himself as an avatar of a deeper reservoir of hatred bubbling up from the chan board, it would in fact be inaccurate to ascribe them too much agency. Although the Christchurch shooter’s actions clearly energised discussion on these boards (correlating to a large though brief uptick in the relative frequency of anti-Muslim slurs), his particular form of hatred differed somewhat from the norm. While the Christchurch shooter was, like many anons, preoccupied with alt-history, it appears that he had developed a somewhat idiosyncratic extremist perspective of his own, which emphasizes his own agency in his violent actions. We can get an empirical sense of this by looking at another of his ‘texts’, besides the manifesto, that being the actual weapons that he used in the killings, on which he had inscribed assorted arcane names, dates and historical events. In aggregate, the inscriptions on the Christchurh shooter’s weapons can be read as recounting a Manichaean narrative of an embattled ‘white world’—a theme on 4chan as well as amongst right-wing populist politicians. An overwhelming number of terms present on the Christchurch shooter’s weapons were dates of battles in European history. Judged by his gun as text, Christchurch shooter had developed an elaborate theory of the key points in Western military history focused primarily on the period of ‘Reconquista’ in Spain, the Crusades and assorted wars against the Ottoman Empire.38 When querying these terms in archives of the /pol/ boards, what we find is that most of these terms were in fact relatively rarely used in either 4chan or 8chan. While this does not necessarily diminish the severity of the potential threat as posed by these far-right discussion boards, it does complicate the theory that the shooter was merely an avatar of alt-right chan culture.39

Conclusion

To conclude, our research departed from the hypothesis that 4Chan /pol/ is giving a vernacular format to a long tradition of post-war far-right political thought. Departing from the historical account of post-war esoteric fascism as set out by Nicholas Goodrick-Clark, our research sought to introduce the reader to the ongoing significance of Julius Evola’s ideas concerning the idea of white supremacist Holy War, and to identify instance of how this framework is engaged with in discussions about anonymous chan culture. As seen in their preoccupation with Evola’s concept of Kali Yuga, across 4chan’s alt-histories there is a sense of eternal return, as the wheel of time moves between the ages, and an apocalyptic preoccupation with death of the West at the hands of a Manichaean enemy. But while this new culture of hate appears similar in many ways to the one discussed by scholars of post-war fascism, in its vernacular forms it potentially poses a different kind of problem. Returning, by way of conclusion, to the opening image of a ‘fashwave’ meme, the point of researching these marginal discussions is that 4chan has long been acknowledged as the home of memes. In spite of its toxicity, this anonymous subculture has been remarkably productive of vernacular innovation. One explanation for this is that the high volume of posts to 4chan functions as a ‘powerful selection machine’ for the production of attention-grabbing memes.40 While this explanation is consistent with the original concept of a meme as a ‘unit of cultural transmission’ subject to the competitive mechanisms of evolutionary biology, it does not sit particularly comfortably with the media studies literature on vernacular creativity and memes, the latter which emphasises the role of human agency.41 Besides media studies, many disciplines within the humanities have convincingly critiqued Richard Dawkins’ reduction of cultural transmission to epidemiology. While evolutionary biology may be unsuitable for discussing the development of complex ideas such as religion (the latter a favourite target of Dawkins), perhaps it may still offer insights into the dissemination of extremely simplistic and dangerous world-views couched in the pseudo-profound jargon of esoteric fascism. In the case on 4chan’s Politically Incorrect board (/pol/), we see an example of the dynamics of this extreme form of memetic antagonism pushed to their furthest extreme. Whilst the peculiar and disturbing preoccupation with apocalypticism, Manichaean demonology and occult symbology described in this chapter has been studied by historians of the extreme-right, what is new is how this historical imaginary is being hybridised with memes and the subculture of the ‘deep vernacular web’.

Acknowledgements

Inspired by and produced in consultation with the historian Louie Dean Valencia-García, this text draws on empirical research conducted at the 2019 Digital Methods Summer School in Amsterdam by Daniel Jurg, Jack Wilson, Emillie de Keulenaar, Giulia Giorgi, Marc Tuters and Ivan Kisjes.

Notes

1 While small in number, the alt-right managed to capture media attention precisely through their use and appreciation of existing web subculture in order to promote a highly reactionary, and often explicitly fascistic, political message. As the alt-right skilfully manipulated journalists into amplifying their message, scholarly exposés should be careful not to exoticise this phenomenon.

2 Tuters, ‘LARPing and Liberal Tears: Irony, Belief and Idiocy in the Deep Vernacular Web’.

3 Nagle, ‘Paleocons for Porn’; Miller-Idriss, The Extreme Gone Mainstream: Commercialization and Far Right Youth Culture in Germany.

4 Currently represented in the public mind by the 4chan board, chan boards are distinguished from other contemporary social media by their anonymity and ephemerality, technical affordances that encourage the use of memes as a means by which users of 4chan demonstrate their in-group status.

5 Griffin, ‘Interregnum or Endgame? the Radical Right in the “Post-Fascist” Era’; Goodrick-Clarke, Black Sun: Aryan Cults, Esoteric Nazism, and the Politics of Identity; Sedgewick, Against the Modern World: Traditionalism and the Secret Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century; Ross, Against the Fascist Creep.

6 A note on this matter before proceeding, in researching the alt-right there is the concern that one’s work might help legitimise an otherwise marginal phenomenon (see Phillips 2018). The criticism here is that some exposés on anonymous chan culture have bestowed them with ‘a kind of atemporal, almost godlike power’ (Phillips et al. 2017), in the process feeding into the fantasy of their outsized dark influence. Keeping this valid criticism in mind it is nevertheless important to consider the possibility of how anonymous chan culture may innovate new ways for the dissemination of old and potentially dangerous ideas.

7 Tuters et al., ‘Post-Truth Protest: How 4chan Cooked Up the Pizzagate Bullshit’.

8 David, High Weirdness: Drugs, Esoterica, and Visionary Experience in the Seventies. Other variations of these so-called pills include ‘black pills’, which indicate a sort of hopelessness and push believers into desperation. ‘Glorious pills’ provide inspiration to continue the fight against liberal and all that is ‘inglorious’.

9 This aspect of the article is indebted to Jack Wilson’s insights and analysis.

10 Valencia-García, ‘The Rise and Fall of the Far-Right in the Internet Age’.

11 This use of ‘debris’ by Baudet also echoes a prominent idea that Evola writes about in his books Men among the Ruins: Post-War Reflections of a Radical Traditionalist (1953) and Ride the Tiger: A Survival Manual for the Aristocrats of the Soul (1961). In both works Evola describes an elite group of traditionalist men who recognise the wrongs of the current era, describing them in the former as being ‘among the ruins’ of Western civilisation and in the latter as an elite ‘who are, so to speak, still on their feet among the ruins and dissolution, and who belong, more or less consciously, to that other [traditionalist] world’ (Ride the Tiger, 3).

12 Mersbergen, ‘Oikofobie? Boreaal? Immanent? Oftewel: wat zij Baudet?’. Credit goes to Daniel Jurg for having researched this aspect of the article.

13 CommonSenseTV, ‘Thierry Baudet (FvD) over het woord Boreaal’.

14 Valk and Floor, ‘“Verboden” ideeën trekken hem aan’.

15 Le Pen, ‘We Must Save Boreal Europe and the White World’.

16 Evola, Revolt against the Modern World: Politics, Religion, and Social Order in the Kali Yuga.

17 Griffin, ‘Interregnum or Endgame? the Radical Right in the “Post-Fascist” Era’.

18 Evola, The Metaphysics of War, 64.

19 Ibid., 65.

20 Ibid. While Evola has long been a favourite of the extreme-right in Italy, until recently he was known primarily amongst esotericists and Anglo-academia. The recent translation of his political theory by the far-right publisher Arktos Media, profiled elsewhere in this volume, has made for intriguing discussions of Evola’s work between esotericists and ideologists of the far-right (see comment section in Hanegraaf 2017). In some ways, Evola’s brand of esoteric fascism produced an alternative variety of fascism, one that reached both into the past, but that held itself as distinct from Hitlerism. Because of this differentiation, Arktos has been able to repackage Evola’s ideologies into short pamphlet-length volumes with aesthetically attractive minimalist covers, taking advantage of Evola’s coded language. Editor’s Note: See chapter 16.

21 Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas, 53.

22 Griffin, ‘Revolts Against the Modern World’.

23 Goodrick-Clarke, 6.

24 Somewhat akin to Nietzsche’s notion of the übermensch, under the influence of Max Stirner, Evola called for self-realisation of the fallen man of liberal democratic mass culture into the state of what he referred to as the Absolute Individual (see Sedgwick 2004, 99 and Ross 2017, 77).

25 Kershaw, Hitler, 1889–1936: Hubris, 138. Whilst such universal myths of cyclical theories appear mind-bogglingly archaic, as the founding figure of modern comparative religious studies Mircea Eliade noted, they provide their believers with a means for renewal against foreigners (see Sedgewick 109–17).

26 In seeking to break taboos whilst at the same time denying themselves the ultimate pleasure of sexual release as a means to cultivate awareness (vidya) as well as magical power (siddhis), there are undeniable parallels here with contemporary chan subcultural notions of ‘no-fap’, ‘red-pill’ and ‘meme magic’.

27 From John Morgan’s introduction to The Metaphysics of War (Evola 2011, 14). Notably, in the post-68 period the European New Right developed its own anti-modern, anti-globalisation critique advocating for a pan-European ‘rooted’ tradition as a bulwark against the hegemony of US imperialism. In the eyes of some critics the European New Right has simply rebranded a moribund fascist ideology that had become off-limits in the post-war years (Griffin 2000). Others suggest that contemporary scientific findings concerning heredity as well as tribal psychology are odds with egalitarian ideology which renders the new cultural or ‘differential’ form of racism impregnable to those strategies developed by anti-racists in relation to the biological racism as for example espoused by Nazis.

28 Identitarianism is more fully explained in the introduction of this volume. See also José Pedro Zúquete, The Identitarians: The Movement against Globalism and Islam in Europe (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2018).

29 Whilst interpretation of the Third Reich was further developed by Miguel Serrano, the high priestess of Esoteric Hitlerism and the Aryan myth more generally was Savitri Devi. Born Maximiani Portas in 1905, Devi was a French woman of Greek origins who studied in esoteric Hindu doctrine in India in the inter-war years coming to espouse the esoteric fascist belief that the renewal of Aryan society required the creation of a ‘new man’ unafraid to engage in spiritual violence, for whom Hitler was the archetype (see Goodrick-Clarke 2004: 88–106; Ross 2017: 133).

30 The seemingly single most popular icon in fashwave memes, the origin of the Black Sun image is credited to the former SS member Wilhelm Landig, whom also popularised the theories of Atlantis as well as the Hyperborean origins of the Aryan race (Goodrick-Clarke 2004: 3). Heinrich Himmler used it in the design of an occult chamber in Wewelsburg castle, the latter which was intended to have been the future SS headquarters for the Third Reich.

31 Hine et al., ‘A Longitudinal Measurement Study of 4chan’s Politically Incorrect Forum and Its Effect on the Web’; Lobinger et al., ‘The Pepe Dilemma: a Visual Meme Caught Between Humor, Hate Speech, Far-Right Ideology and Fandom’; Beran, ‘4chan: the Skeleton Key to the Rise of Trump’.

32 See Coleman, Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: the Many Faces of Anonymous; Phillips, This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things: Mapping the Relationship Between Online Trolling and Mainstream Culture.

33 OIlab, ‘4chan’s YouTube: A Fringe Perspective on YouTube’s Great Purge of 2019’.

34 See de Zeeuw and Tuters, ‘Teh Internet Is Serious Business: On the Deep Vernacular Web and Its Discontents’.

35 Hagen et al., ‘Infinity’s Abyss: An Overview of 8chan’.

36 Evans, ‘Shitposting, Inspirational Terrorism, and the Christchurch Mosque Massacre’.

37 Donovan and Boyd, ‘The Case for Quarantining Extremist Ideas’.

38 As S.J. Pearce notes in Chapter 2 of this volume, as well as Louie Dean Valencia-García notes in Chapter 16, the history of Al-Andalus and the rhetoric of the Reconquista are sites in which the far-right have attempted to re-write history so that to erase the diverse religions and cultures that existed in the Iberian Peninsula prior to the arrival of Islam in 711 in order to invent an alt-history in which there was only a homogenous, traditionalist Christian culture.

39 Amongst other factors the Christchurch shooter should also be understood in light of the rise of violent Australian nativism, the so-called ‘New Integrationalism’ ideology which seeks to exclude Muslim migrants (Poynting and Mason 2007).

40 Bernstein et al., 56.

41 Dawkins, The Selfish Gene, 189–200; Burgess, Vernacular Creativity and New Media; Shifman, Memes in Digital Culture.

References

Bastian, M., Heymann, S., Jacomy, M. 2009. ‘Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks’. International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media.

Beran, Dale. 2017. ‘4chan: the Skeleton Key to the Rise of Trump – Dale Beran – Medium’. Medium.com. 12 February 2017. Archived 16 August 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20190816185427/https://medium.com/@DaleBeran/4chan-the-skeleton-key-to-the-rise-of-trump-624e7cb798cb.

Bernstein, Michael S, Andres Monroy-Hernandez, Drew Harry, Paul Andre, Katrina Panovich, and Greg Vargas. 2011. ‘4chan and /B/: An Analysis of Anonymity and Ephemerality in a Large Online Community’. Proceedings of the Fifth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media. www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/ICWSM/ICWSM11/paper/viewFile/2873/4398.

Burgess, Jean. 2007. ‘Vernacular Creativity and New Media’. Queensland University of Technology. Archived 2 March 2017. https://web.archive.org/web/20170302060104/http://eprints.qut.edu.au/16378/1/Jean_Burgess_Thesis.pdf.

Coleman, Gabriella. 2014. Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: The Many Faces of Anonymous. New York: Verso.

CommonSenseTV. Thierry Baudet (FvD) over het woord Boreaal. 23 April 2019. Archived 26 July 2019. www.youtube.com/watch?v=kRuTS20COaA.

David, Erik. 2019. High Weirdness: Drugs, Esoterica, and Visionary Experience in the Seventies. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Dawkins, Richard. 1976. The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

de Zeeuw, Daniël and Marc Tuters. forthcoming. ‘Teh Internet is Serious Business: On the Deep Vernacular Web and its Discontents’. in Cultural Politics.

Donovan, Joan and Danah Boyd. 2018. ‘The Case for Quarantining Extremist Ideas’. The Guardian. 1 June 2018. Archived 15 August 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20190815030013/https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/jun/01/extremist-ideas-media-coverage-kkk.

Evans, Robert. 2019. ‘Shitposting, Inspirational Terrorism, and the Christchurch Mosque Massacre’. www.bellingcat.com/news/rest-of-world/2019/03/15/shitposting-inspirational-terrorism-and-the-christchurch-mosque-massacre/.

Evola, Julius. 1995 (1934). Revolt against the Modern World: Politics, Religion, and Social Order in the Kali Yuga. Rochester: Inner Traditions.

Evola, Julius. 2011. The Metaphysics of War. Budapest: Arktos.

Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas. 2001. Black Sun: Aryan Cults, Esoteric Nazism, and the Politics of Identity. NYU Press.

Griffin, Roger. 1985. ‘Revolts against the Modern World’, Literature and History 11 (1), 101–24.

Griffin, Roger. 2000. ‘Interregnum or Endgame? the Radical Right in the ‘Post-Fascist’ Era’. Journal of Political Ideologies 5 (2), 163–178.

Hagen, Sal, Anthony Burton, Jack Wilson and Marc Tuters. 2019. ‘Infinity’s Abyss: An Overview of 8chan’. 9 August 2019. Archived 19 August 2019. http://web.archive.org/save/https://oilab.eu/infinitys-abyss-an-overview-of-8chan/.

Hanegraaff, Wouter. 2017. ‘Evola in Middle Earth’. 4 August 2017. Archived 3 June 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20190603135158/http://wouterjhanegraaff.blogspot.com/2017/08/evola-in-middle-earth.html.

Hine, Gabriel Emile, Jeremiah Onaolapo, Emiliano De Cristofaro, Nicolas Kourtellis, Ilias Leontiadis, Riginos Samaras, Gianluca Stringhini, and Jeremy Blackburn. 2016. ‘A Longitudinal Measurement Study of 4chan’s Politically Incorrect Forum and Its Effect on the Web’, November, 1–14. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1610.03452v3.pdf

Kershaw, Ian. 2000. Hitler, 1889–1936: Hubris, New York: W. W. Norton and Company.

Kleinpastie, Thijs. 2019. ‘The New Face of the Dutch Far-Right’. Foreign Policy. 28 March 2019. Archived 27 July 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20190709105722/https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/03/28/the-new-face-of-the-dutch-far-right-fvd-thierry-baudet-netherlands-pvv-geert-wilders/.

Le Pen, Jean Marie. 2015. ‘“We Must Save Boreal Europe and the White World”: Jean-Marie Le Pen’s Rivarol Interview’, Counter-Currents. Archived 17 August 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20190329150139/https://www.counter-currents.com/2015/04/jean-marie-le-pens-rivarol-interview/.

Lobinger, Katharina, Benjamin Kramer, Eleonora Benecchi, and Rebecca Venema. 2018. ‘Pepe the Frog – lustiges Internet-Meme, Nazi-Symbol und Herausforderung für die Visuelle Kommunikationsforschun’. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331873206_Pepe_the_Frog_-_lustiges_Internet-Meme_Nazi-Symbol_und_Herausforderung_fur_die_Visuelle_Kommunikationsforschung.

Lovink, Geert and Marc Tuters. 2018. ‘Rude Awakening: Memes as Dialectical Images’. 3 April 2018. Archived 12 February 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20190212204531/http://networkcultures.org/geert/2018/04/03/rude-awakening-memes-as-dialectical-images-by-geert-lovink-marc-tuters/.

Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. 1948. The Manifesto of the Communist Party. New York: International Publishers.

Mersbergen, Sander van. ‘Oikofobie? Boreaal? Immanent? Oftewel: wat zij Baudet?’ Algemeen Dagblad. 21 Maart 2019. 6 August 2019. Archived 13 June 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20190613164357/https://www.ad.nl/politiek/oikofobie-boreaal-immanent-oftewel-wat-zei-baudet~a6827f80/.

Miller-Idriss, Cynthia. 2017. The Extreme Gone Mainstream: Commercialization and Far Right Youth Culture in Germany. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Nagle, A., 2017. ‘Paleocons for Porn’. Jacobin Magazine. www.jacobinmag.com/2017/02/paleocons-for-porn/https://www.jacobinmag.com/2017/02/paleocons-for-porn/.

OIlab. 2019. ‘4chan’s YouTube: A Fringe Perspective on YouTube’s Great Purge of 2019’. 16 July 2019. Archived 19 August 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20190819153100/https://oilab.eu/4chans-youtube-a-fringe-perspective-on-youtubes-great-purge-of-2019/.

Peeters, Stijn and Sal Hagen. 2018. ‘4CAT: Capture and Analysis Toolkit’ Computer software. Vers. 0.5.

Phillips, Whitney. 2015. This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things: Mapping the Relationship Between Online Trolling and Mainstream Culture. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Phillips, Whitney. 2018. The Oxygen of Amplification: Better Practices for Reporting on Extremists, Antagonists, and Manipulators Online. New York: Data and Society Research Institute.

Phillips, Whitney, Jessica Beyer, and Gabriella Coleman. 2017. ‘Trolling Scholars Debunk the Idea That the Alt-Right’s Shitposters Have Magic Powers’. Vice. 22 March 2017. Archived 1 August 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20190801005129/https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/z4k549/trolling-scholars-debunk-the-idea-that-the-alt-rights-trolls-have-magic-powers.

Poynting, S., and Mason, V. 2007. The resistible rise of Islamophobia: Anti-Muslim racism in the UK and Australia before 11 September 2001. Journal of Sociology 43 (1), 61–86.

Ross, Alexander Reid. 2017. Against the Fascist Creep. New York: AK Press.

Sedgewick, Mark. 2004. Against the Modern World: Traditionalism and the Secret Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shifman, Limor. 2014. Memes in Digital Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Tuters, Marc. 2018. ‘LARPing and Liberal Tears: Irony, Belief and Idiocy in the Deep Vernacular Web’. In Post-Digital Cultures of the Far Right Online Actions and Offline Consequences, edited by Maik Fielitz and Nick Thurston, Berlin: Transcript Verlag, 37–48.

Tuters, Marc, Emilija Jokubauskaite, and Daniel Bach. 2018. ‘Post-Truth Protest: How 4chan Cooked Up the Pizzagate Bullshit’. MC Journal 21 (3). Archived 6 March 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20190306151854/http://journal.media-culture.org.au/index.php/mcjournal/article/view/1422.

Valencia-García, Louie Dean. 2017. ‘The Rise of the European Far-Right in the Internet Age’. EuropeNow (Council for European Studies at Columbia University). February 2018. Archived 8 August 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20190808202437/https://www.europenowjournal.org/2018/01/31/the-rise-of-the-european-far-right-in-the-internet-age/.

Valk, Guus and Rusman, Floor. ‘‘Verboden’ ideeën trekken hem aan’. NRC. 22 March 2019. Archived 28 March 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20190328155516/https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2019/03/22/verboden-ideeen-trekken- hem-aan-a3954314.