![33. Confederate cotton bond prices. (DATA FROM MARC D. WEIDENMIER, “THE MARKET FOR CONFEDERATE COTTON BONDS,” EXPLORATIONS IN ECONOMIC HISTORY 37 [JANUARY 2000])](images/f0259-01.jpg)

If slaves will make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong. . . . Better by far to yield to the demands of England and France and abolish slavery, and thereby purchase their aid, than to resort to this policy, which leads as certainly to ruin and subjugation as it is adopted.

—HOWELL COBB, CONFEDERATE GENERAL, JANUARY 8, 1865

THE POPULAR APPEAL OF THE UNION’S EMANCIPATION POLICY had become undeniable to all but the most obstinate Confederate sympathizers abroad by the summer of 1863. It would not be until the eleventh hour, more than two years after Lincoln’s initial emancipation decree, that Confederate leaders considered answering with their own promise of emancipation. The main obstacle to their diplomatic success, Confederates grudgingly admitted, was the stubborn prejudice abroad that human slavery was morally reprehensible and their own admission that slavery lay at the very cornerstone of the national edifice they were trying to build. In the second half of 1863, Confederate leaders conceded defeat in Britain and found growing opposition in France. They turned to Rome to enlist Pope Pius IX and his Catholic flock in the cause of peace and Southern independence, only to encounter the same reservations about slavery. Emancipation, the Confederacy’s last desperate card, was played in large part behind closed doors in Richmond, Paris, and London beginning in late 1864 and with utmost secrecy. It was the unspeakable dilemma: in order to win independence, they would have to renounce the main reason they had sought independence in the first place.

In July 1863 news from Gettysburg and Vicksburg dealt powerful blows to an abiding confidence, both in the South and abroad, that if the Confederacy could not win on the battlefield, it could at least outlast the North. These crushing defeats were “so unexpected,” Henry Hotze wrote from London, that a “general dismay” quickly spread across Britain not only among active sympathizers “but even among those who take merely a selfish interest in the great struggle.”

The prices of Confederate bonds, which had been brought to market in March 1863 to finance the Erlanger loan, provide a telling barometer of confidence in Confederate fortunes. Though public sentiment seemed to be turning in favor of the Union and Liberty, hard-nosed investors in Europe were betting heavily on the success of the Confederacy. The Confederate bond sales were oversubscribed within days of their initial offering and continued into July selling near their opening price at about 90 percent of face value. News of Vicksburg and Gettysburg sent prices plummeting to 60 percent by mid-September and, after a brief recovery, down to 38 percent of face value by the end of 1863.1

That September the frustrated Confederate commissioner in London, James Mason, having finally received his instructions from Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin, informed Earl Russell that he was withdrawing his mission from London. Henry Hotze carried on alone in London, publishing his Index and casting the most favorable light possible on the news from America. After Edwin De Leon, the self-styled ambassador to public opinion on the Continent, was sacked at the end of 1863, Benjamin instructed Hotze to expand operations to France, Italy, and Germany. Hotze accepted his new duties with his irrepressible confidence. Let “our armies and our currency hold out a little while longer,” he wrote to Benjamin at the end of 1863, “and we shall enter the assemblage of nations without being asked to wash the robe of our nationality ‘of a foul stain.’”2

The Confederacy’s envoy to France, John Slidell, remained comfortably ensconced in the beau monde of Parisian society, and was, to all appearances, unperturbed by signs of the crumbling fortunes of the South in Europe. He gloated over the loan financed by his future son-in-law, Baron Frédéric Emile d’Erlanger, and pronounced the early success of the cotton bonds on European markets as tantamount to “financial recognition of our independence.” Slidell allowed himself to be deluded that in the course of time, the North would eventually exhaust itself and the South would win its independence whatever sacrifice it endured in the meantime. When the French press began to shift its tone in favor of the Union, he convinced himself it was due to nothing more than bribes from Union agents.3

![33. Confederate cotton bond prices. (DATA FROM MARC D. WEIDENMIER, “THE MARKET FOR CONFEDERATE COTTON BONDS,” EXPLORATIONS IN ECONOMIC HISTORY 37 [JANUARY 2000])](images/f0259-01.jpg)

33. Confederate cotton bond prices. (DATA FROM MARC D. WEIDENMIER, “THE MARKET FOR CONFEDERATE COTTON BONDS,” EXPLORATIONS IN ECONOMIC HISTORY 37 [JANUARY 2000])

The change in the French mood was real, however. In the parliamentary elections of June 1863, the liberal opposition won stunning victories against the imperial party, and the embattled opposition known as Les Cinq (the Five) was now enlarged to eighty-four seats in the Corps législatif, all more or less opposed to Napoleon III’s policies on Mexico, Rome, and perhaps America. The emperor had taken measured steps toward liberalization since 1860, but it seemed to arouse only bolder opposition. France, with its muzzled press and legislature, Malakoff told New York Times readers, is “ashamed to see all the nations around her enjoying more liberty than she does.”4

Slidell seemed strangely unmindful of the tide of public sentiment and liberal political opposition setting against the South. On New Year’s Day 1864 he and his wife, Mathilde, were out strolling near the Champs-Élysées when a group of brash schoolboys, several of them Americans, fell in behind them, waving small Union flags, catcalling, and singing “Hang Jeff Davis to a sour apple tree.” It had obviously been planned in advance, for they held up a crude sign: “Down with Slidell, the Slave-driver.” Some of the boys brandished peashooters and blasted him with spit wads. Slidell wheeled around and grabbed one of them by the coat and “soundly cuffed him.” The boy nimbly wriggled out of his coat and left Slidell holding it, cursing the boys as they ran off. The man once serenaded at the train station and toasted by Parisian society stood surrounded by a jeering crowd of onlookers.5

EVEN AS THE UNION’S EMANCIPATION POLICY GAINED FAVOR IN THE European imagination, the Confederacy did not seriously consider moderating its message or outflanking the enemy with its own promise of gradual emancipation, as James Spence and other foreign sympathizers were suggesting. Instead, Confederate foreign policy gravitated in the opposite direction, seeking to align the South with the conservative opposition to abolitionism, radical egalitarianism, and revolutionary republicanism. In 1863 Confederate diplomats began their shift to the right by going to the epicenter of reaction in Europe: the Vatican.

Pope Pius IX, or Pio Nono, as he was known to Italians, was monarch of the Papal States surrounding Rome and shepherd to millions of Catholic faithful in Europe, Latin America, and North America. Rome and the Papal States, however, stood besieged by the Italian Risorgimento against which Napoleon III’s garrisoned French troops defended the pontiff’s realm. Italians nationalists, not least Garibaldi and his followers, wanted nothing more than to drive out the French and make Rome the capital of a fully united Italy. Only the uncertain support of Napoleon III, bolstered by his devout wife, Eugénie, kept Garibaldi and Italy at bay. While the Union was courting Garibaldi and his Red Shirt republicans, the Confederacy sought to align its cause with their nemesis, Pio Nono, and his vast Catholic flock.

The pope had been duly alarmed by the enormous popular enthusiasm aroused by Garibaldi for his fateful march on Rome in 1862 and by the subsequent displays of adoration for the wounded hero. Catholic leaders in Europe and America had involved the church in the American conflict, whether they intended to or not. Following Archbishop John Hughes’s tour of Europe in 1861–1862, Patrick Lynch, the Irish-born Catholic bishop of Charleston, South Carolina, and an ardent defender of the Confederacy and slavery, publicly berated Hughes for arousing support of the Union cause instead of counseling peace. In July 1862 Lynch made public a lengthy report he had sent to the pope detailing the many sufferings in his diocese due to the war. He successfully beseeched Pio Nono to call for peace in America.6

It was not uncommon for a pope or other religious leaders to appeal for peace among nations at war, but Pope Pius IX chose to counsel peace at a time when peace meant victory for secession. Moreover, the pope’s call for peace conveniently coincided with the British and French plot to intervene in the autumn of 1862.7

In October 1862 Pio Nono began issuing public letters to Catholic leaders in America, calling for an end to the “destructive civil war.” He sent letters to Archbishop John Hughes in New York and Archbishop John Mary Odin in New Orleans, deploring “the slaughter, ruin, destruction, devastation, and the other innumerable and ever-to-be deplored calamities” by which the “Christian people of the United States of America” are suffering by their “destructive civil war.” The pope urged the archbishops to “apply all your study and exertion” with people and their rulers “to conciliate the minds of the combatants.” He sent similar letters to Catholic bishops in Cincinnati and Chicago, and in these he alluded to alleged Union atrocities against Catholics and deprecated “the heavy afflictions brought upon us by the wicked designs and machinations of those men who wage an unholy war against the Catholic Church.” In late November 1862, as British and French plans for intervention were faltering, the pope met with Richard Blatchford, the new US minister to Rome, and offered the Vatican’s good offices for mediation.8

Slidell recognized a promising new opportunity. Early in 1863 he wrote to Benjamin to propose augmenting the South’s Latin strategy, which aimed at building an alliance with France, by sending a mission to the Vatican. Slidell was intrigued by the report of his friend Charles S. Morehead, former governor of Kentucky, who was visiting American friends in Rome when he met with Cardinal Antonelli, the pope’s shrewd consigliere on international affairs. Morehead came away with a strong impression that Antonelli favored the South and might be willing to bring the influence of the Catholic Church to bear on the peace movement in America.9

Benjamin found all of this to be “very interesting,” and he wrote back to Slidell, instructing him to make the most of recent reports of sacrilegious acts by Union soldiers plundering and defiling Catholic churches in Louisiana. This is due, he suggested, to “the detestable Puritan spirit which . . . originated this savage war,” an intolerance that is “just as hostile to the Catholic religion as the ultra abolitionists are to slaveholders.” Benjamin saw a promising new vein of propaganda that could be effectively retailed to Catholics at the docks of Ireland and the recruiting stations and battlefields of America. But it would have more impact if the pope would lend his voice to the cause.10

In August 1863, with news of Union triumphs at Gettysburg and Vicksburg at hand, Pope Pius IX renewed his plea for peace. It came to light that Archbishop Hughes had done nothing to publicize the pope’s October 1862 letter, and the Vatican decided this time it would go directly to the Catholic press by asking the Tablet, a newspaper sponsored by the Brooklyn diocese, to belatedly publish the pope’s “lost” plea for peace. The pontiff’s call for an end to America’s war appeared in newspapers across the United States in August 1863.11

In Richmond Benjamin finally recognized in the pope’s epistle for peace a timely pretext for the opening of relations with Rome. In September 1863 he instructed Ambrose Dudley Mann, the Confederate envoy stationed in Brussels, to go in person to Rome and deliver a letter from President Jefferson Davis, thanking the pope for his kind efforts in support of peace. Mann was eager and ready for this mission to Rome. For more than a year he had been pestering Benjamin to send him to Italy, where his son and personal secretary, W. Grayson Mann, had been sounding out what he felt certain were promising new diplomatic channels.12

Pius IX’s reign would be remembered as a rebellion against everything modern. He was elected in 1846, ironically by liberal-minded cardinals who hoped he might help the church adapt to the new democratic spirit of the age. Those hopes were dashed after Mazzini’s revolutionaries captured Rome, declared it a republic, and drove the pontiff into exile. That was when Louis-Napoleon sent French troops to Rome to restore the pope to his Vatican throne.

34. Pope Pius IX, with his court (Cardinal Antonelli, third from right). (COURTESY MARCO PIZZO, MUSEO CENTRALE DEL RISORGIMENTO, ROME)

From that point forward, Pio Nono became the archenemy of the Italian liberal state and everything to do with “the Revolution.” His most shocking assault on liberal secular beliefs was the “Syllabus of Errors” of 1864, which listed no fewer than eighty heresies of the modern world that all Catholics must renounce, among them freedom of speech, press, and religion; separation of church and state; and the very idea that “the Roman Pontiff should reconcile himself to progress, liberalism, and modern civilization.” Later, Pius IX’s First Vatican Council would declare the pope to be infallible. Besieged by Garibaldi and the Risorgimento, protected only by Napoleon III’s French forces, the pontiff of Rome summoned the faithful to repudiate the modern world.13

Mann and his son arrived at the Vatican in early November 1863, carrying with them the sealed letter of thanks from President Davis. Mann’s intricately detailed report to Benjamin revealed an unctuous gratitude for even the smallest gesture of respect. Accustomed to meeting secretly in private homes as though he were an unwelcome supplicant, Mann was impressed by the diplomatic courtesy that Cardinal Antonelli and the pontiff accorded him. He drew Benjamin’s attention to the “strikingly majestic” conduct of the Papal States “in its bearing toward me when contrasted with the sneaking subterfuges . . . of the governments of western Europe.” Mann was pleased to report how he and his son, Grayson, who acted as translator, were admitted to the pope’s audience “ten minutes prior to the appointed time,” invited to “stand near to his side,” and treated to an audience of “forty minutes duration, an unusually long one.” The whole interview was marked by such consideration as “might be envied by the envoy of the oldest member of the family of nations.”14

Grayson Mann read Davis’s letter aloud to the pope, translating it into Italian and giving every sentence “a slow, solemn, and emphatic pronunciation,” while his proud father monitored the pope’s every change of expression and gesticulation. Davis’s letter to the pope lamented the suffering of the South and, implicitly, asked His Holiness for help. “Every sentence of the letter appeared to sensibly affect him,” Mann solemnly assured Benjamin. The pope’s “deep sunken orbs, visibly moistened, were upturned toward that throne upon which ever sits the Prince of Peace,” a sign to Mann that the Holy Father was “pleading for our deliverance from that causeless and merciless war which is prosecuted against us.”

Once Grayson Mann finished reading the letter, the pope asked his father pointedly if “President Davis” was Catholic. “No,” Mann had to sheepishly confess. Nor was he, the pope also gently forced him to admit. The pope moved on to a far more awkward matter by alluding to the North’s proclamation of emancipation and suggesting that “it might perhaps be judicious in us to consent to gradual emancipation.” Mann gave no comfort to His Holiness on this matter either and instead defended the South’s right to slavery and lambasted “Lincoln and Company” for their heinous plan “to convert the well-cared-for civilized negro into a semibarbarian.” Mann went on to extol the loyalty of “our slaves,” who wanted nothing more than “to return to their old homes, the love of which was the strongest of their affections.” The Confederate emissary saw nothing but “approving expression” and “evident satisfaction” in the pope’s reaction.

Pivoting to the subject of the pope’s suffering flock in Ireland and Germany who were being recruited into the Union army, Mann lamented that “these poor unfortunates” were being tempted by bounty money to enlist against the South. Were it not for these foreign recruits, the North would have failed long ago. “His Holiness,” Mann reported, “expressed his utter astonishment, repeatedly throwing up his hands.” The pontiff promised that he would write a letter that Mann’s government would be welcome to publish. He then held up his hand “as a signal for the end of the audience.” “Thus terminated one among the most remarkable conferences that ever a foreign representative had with a potentate of the earth,” Mann breathlessly reported to Benjamin. “And such a potentate! A potentate who wields the consciences of 175,000,000 of the civilized race, and who is adored by that immense number as the vice regent of Almighty God in this sublunary sphere.”15

Pio Nono kept Mann waiting in Rome for the next month before delivering a brief letter, in Latin, deploring the fatale civile bellum (fatal civil war) and the cruel intestinum bellum (internal war) and hoping that God would “pour out the spirit of Christian love and peace upon all the people of America.” What thrilled Mann, however, was that on the outside of the envelope, the pope had addressed the letter to Illustri et Honorabili Viro, Jefferson Davis, Praesidi foederatarum Americae regionum. Mann took some liberties in translating this as “Illustrious and Honorable, Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America.” He eagerly informed Benjamin that in the pope’s few precious words, he had attained exactly what the Confederacy had been awaiting for two and a half years. “Thus we are acknowledged, by as high an authority as this world contains, to be an independent power of the earth.”

Mann was absolutely ecstatic. “I congratulate you,” he told Benjamin. “I congratulate the President, I congratulate his Cabinet; in short, I congratulate all my true-hearted countrymen and countrywomen, upon this benign event. The hand of the Lord has been in it, and eternal glory and praise be to His holy and righteous name.” This was the turning point, Mann felt certain. “The example of the sovereign pontiff, if I am not much mistaken, will exercise a salutary influence upon both the Catholic and Protestant governments of western Europe. Humanity will be aroused everywhere to the importance of its early emulation.”16

One can almost hear Benjamin groaning in his February 1864 reply to Mann. The pope’s address to “President Davis,” he explained, was nothing more than “a formula of politeness to his correspondent, not a political recognition of a fact.” He also had to point out that, far from being a sign of recognition of Southern sovereignty, by referring to the conflict as an “intestine or civil war,” the pope was implying quite the opposite. Though he was not Catholic in faith, Jefferson Davis had been educated at a Catholic school, and he knew enough Latin to see that Mann had misconstrued the translation as well as the intent of the pope’s entitlement of “President Davis” and the nation he purported to lead.17

Mann was probably incensed by Benjamin’s interpretation, but he remained utterly convinced of his triumph at the Vatican. Writing to Davis, his old friend, in February 1864, he confided that the “pope is well pleased with that which he has done in emphatically recognizing you as the Executive of a nation. The good old man is willing to do more, and is disregardful of consequences.” Garibaldi, he assured Davis, is “no longer in favor, except with the vulgar,” while “Pio Nono, himself, really has no enemies anywhere.”18

After months of holding onto the original Latin letter, Mann sent it by a trusted special courier to Jefferson Davis in May 1864. “This letter will grace the archives of the Executive Office in all coming time,” his cover letter informed the president. “It will live forever in story as the production of the first potentate who formally recognized your official position and accorded to one of the diplomatic representatives of the Confederate States an audience in an established court palace, like that of St. James or the Tuileries.”19

Ambrose Dudley Mann may have been deluded as to the pope’s intentions, but he recognized in the letter a gold mine for Confederate public diplomacy. Early publication of the letter in Europe, he told Benjamin, was of “paramount importance to the influencing of valuable public opinion, in both hemispheres, in our favor.” Mann had a point; used appropriately, the pope’s letter could leave a plausible impression that he supported the Confederacy in its “holy war” against the “infidel Puritans” and the revolutionary republicans of the North. It would also help highlight the anti-Catholic bigotry that infused both of those enemies of the South.20

The pope’s letter was soon featured in the Confederate campaign against Union enlistments in Ireland and northern Europe. Edwin De Leon, whose wife was Irish, had alerted the Confederate government to the Irish problem as early as July 1862 when Archbishop Hughes was touring Europe. In Dublin “Bishop Hughes is busily beating up recruits in Ireland and haranguing for the North.” “He boasts he can bring 20,000 men to the rescue of the North.”

Thanks to Seward’s Circular 19 publicizing the Homestead Act, a brisk traffic in recruits had picked up in late 1862, especially from Ireland and the German states. The Confederates were slow to respond to Seward’s recruitment initiative, due in part to what Benjamin referred to as the “imperfect communication” between Richmond and agents abroad. It was not until July 1863, nearly a year after Circular 19, that Benjamin sent J. L. Capston, an Irish-born Confederate, to Dublin with instructions to use “every means you can devise” to persuade the Irish against enlisting. Thereafter, the Irish recruitment problem was a major focus of Confederates abroad. Mason and Hotze came over from London and De Leon from Paris to help expose the Union’s “deception” of the Irish.21

In September 1863 Benjamin stepped up efforts in Ireland by sending over Father John B. Bannon, a Catholic chaplain in the Confederate army who was legendary for his oratorical prowess. Bannon carried instructions to use “all legitimate means to enlighten the population as to the true nature and character of the contest now waged on this continent.” “Explain to them,” Benjamin told Bannon, “that they will be called on to meet Irishmen in battle, and thus to embue their hands in the blood of their own friends and perhaps kinsmen in a quarrel which does not concern them.” Tell them of “the hatred of the New England Puritans” for Irishmen and Catholics and the shameful burning and desecration of Catholic churches by New England soldiers.22

Father Bannon arrived in Dublin in late October 1863 and immediately put in place a Confederate counteroffensive to Circular 19. He enlisted Catholic priests in country churches to speak out against the Union recruitment effort from their pulpits. And he hired Irish agents to hover about the docks, visit port-side taverns, call on boardinghouses, distribute thousands of handbills, and put up posters warning immigrants against the Union recruiters.23

“Caution to Emigrants, Persecution of Catholics in America,” one broadside warned, citing atrocities by Massachusetts troops against a Catholic church in Louisiana. “The Priest imprisoned, and afterwards exposed on an Island to Aligators and Snakes! His house robbed of everything!” Others proclaimed the South as the friends of the Irish. “The Southern people are, by race, religion and principles, the natural ally of the foreigner and Catholic,” one flyer in Dublin exclaimed. “They sprang from Spanish, French and Irish ancestors.”24

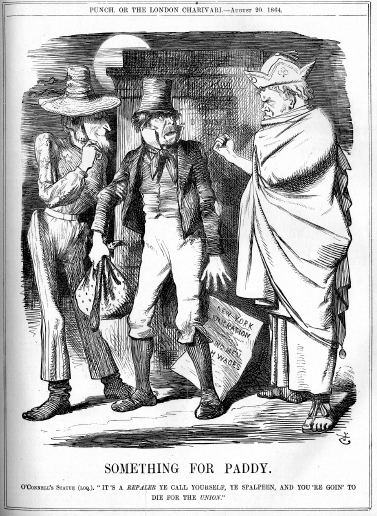

35. Something for Paddy. John Tenniel’s cartoon for London’s Punch, August 20, 1864, depicted an Irish immigrant being recruited by a Union agent resembling Lincoln, while Pope Pius IX glowers at both of them. (COURTESY ALLAN T. KOHL, MINNEAPOLIS COLLEGE OF ART AND DESIGN)

Copies of the pope’s letter to Archbishop Hughes and his epistle to “President” Jefferson Davis were posted as though they were papal bans against enlisting in the Union army. Ambrose Dudley Mann happily credited the papal letters with igniting “formidable demonstrations” in Ireland. He promised his once-skeptical secretary of state that it “will accomplish little less than marvels” by depriving the North of Irish cannon fodder. “To the immortal honor of the Catholic Church, it is now earnestly engaged in throwing every obstacle that it can justly create in the way of the prosecution of the war by the Yankee guerrillas.”25

Benjamin had to concede the effectiveness of the pope’s apparent support, and he soon determined to redouble the effort to win more formal recognition from the Vatican. In March 1864 Benjamin appointed Patrick Lynch, the outspoken Catholic bishop of Charleston, South Carolina, as special envoy to the Papal States. Father Bannon, his mission in Ireland completed, came to Rome to aid Lynch, whose mission was to pursue recognition from Rome and European governments generally and to spread “enlightening opinions and molding impressions” among the public. Lynch was encouraged when the pope granted a private audience to him in July 1864. “It is clear that you are two nations,” the pope assured Lynch. “But still,” he gently advised the Confederacy for the second time, “something might be done looking to an improvement in position or state [of the slaves], and to a gradual preparation for their freedom at a future opportune time.”26

Like Mann, Bishop Lynch saw the pope’s advice on emancipation as a sign that he did not fully understand the Christian character of the South’s peculiar institution. He immediately set his mind to working up a lengthy essay depicting “the actual condition and treatment of slaves at the South.” Lynch’s “A Few Words on Domestic Slavery” grew into an eighty-three-page booklet that advanced a proslavery argument tailored to his European Catholic audience. Sidestepping several of the church’s admonitions condemning slavery, Lynch offered a sunny picture of a “patriarchal” domestic institution that, in practice at least, was in full harmony with the Catholic mission to rescue Africans from their violent heathen origins.

Lynch’s pamphlet first appeared in Italian in late 1864, published anonymously as Lettera di un missionario sulla schiavitù domestica degli Stati Confederati di America (Letter of a missionary on the domestic slavery of the Confederate States of America). Lynch made contact with the deposed but still active Edwin De Leon, who volunteered to translate it into French. De Leon urged Lynch to put his illustrious name to the publication, but the author demurred. Through an acquaintance at the Vatican, Lynch also arranged for a German translation, which was published in early 1865. Though Lynch had copy prepared for an English edition, as the war ended it remained unpublished, but Henry Hotze filled the void by summarizing Lynch’s main points for English-speaking readers of the Index.27

The owner of nearly one hundred slaves, most of them bequeathed to the diocese by deceased parishioners, Bishop Lynch noted that many of the leading Catholic clergy and laymen in the South were fellow slave owners. The slave South, by Bishop Lynch’s account, served as a bulwark against the bigotry and fanaticism of the abolitionists, whom he was quick to identify as rabid anti-Catholic Know-Nothings. Turning to the familiar arsenal of American proslavery arguments, Lynch charged that these abolitionist hypocrites cared nothing for the genuine welfare of the Negro and were trying to use them to ignite a Haitian-style revolution across the South. Appendixes to all editions of his pamphlet included reports on horrible treatment of blacks by the Union army.28

Bishop Lynch’s reply to the pope’s concerns about slavery was revealing of the fixed mind of the Confederate South. For Lynch and the entire Confederate leadership, slavery was beyond debate. It was the cornerstone of the Southern nation, the foundation of King Cotton’s prosperous realm, and the guarantor of white racial supremacy. Lynch’s tract was the last gasp of the South’s effort to repudiate liberal principles of human equality and align itself with the Latin Catholic regimes of the Old and New Worlds against what Pio Nono called “the Revolution.”29

THE CORNERSTONE OF SLAVERY NOW HUNG LIKE A MILLSTONE around the neck of the Confederacy. Those who tried to challenge the dogma of slavery from within the Confederacy were quickly silenced, as Confederate general Patrick Cleburne learned in a cold tent in Georgia in January 1864. Cleburne was born in County Cork, Ireland, to a Protestant family, migrated to the United States in 1849, and settled in Helena, Arkansas. He brought military experience from service in the British army, and when the war came he rose quickly through the ranks to major general. In the winter of 1863–1864, with Sherman’s invading army pressing Confederates into retreat in northern Georgia, Cleburne became convinced that Southerners now faced a cruel choice between arming their slaves or becoming enslaved to the North. It was telling that, once again, it took a foreigner to voice what the Confederate leadership dared not speak out loud.30

Cleburne’s passionate plea, dated January 2, 1864, and cosigned by several other officers, addressed two key problems facing the Confederacy: the perilous shortage of fighting men and the failure to win support abroad. Southerners, his memorandum began, “have spilled much of our best blood,” while the enemy draws on a vast supply of “his own motley population,” “our slaves,” and “Europeans whose hearts are fired into a crusade against us by fictitious pictures of the atrocities of slavery.”

Their friends in England and France had strong incentives to “recognize and assist us, but they cannot assist us without helping slavery,” Cleburne’s memorandum continued. Slavery must be sacrificed for independence, he insisted; the Southerner must decide to “give up the negro slave rather than be a slave himself.” Cleburne called for the outright abolition of slavery followed by the recruitment of blacks willing to fight for Confederate independence. “One thing is certain,” he argued, “as soon as the great sacrifice to independence is made and known in foreign countries,” there would be a complete change “in our favor of the sympathies of the world.”31

The “Cleburne Memorial” was kept secret for a month before his commanding officer forwarded a copy to Richmond. The cover letter denounced the “incendiary document,” and Jefferson Davis promptly ordered his secretary of war to suppress any further discussion of the matter. Cleburne would die at the Battle of Franklin in late November 1864, precisely as the unthinkable notion of freeing and arming slaves came to life again—this time at the center of power in Richmond.32

ON NOVEMBER 8, 1864, ABRAHAM LINCOLN WON A STUNNING reelection victory over George McClellan, his former general whose party called for the restoration of the “Union as it was.” Confederates had pinned most of their hopes on the Northern peace movement. So had European investors: prices for Confederate bonds more than doubled from a low of 38 percent of face value at the end of 1863 to nearly 85 percent in the autumn of 1864. (See cotton bond chart, page 259.) Democrats had appealed to white racial fears and to resentment against the emancipation of blacks who, they predicted, would come North to compete for jobs and drive down wages. But Lincoln and the Republicans had prevailed in the election, and this finally forced the high command in Richmond to consider the very alternatives Cleburne had proposed.

By November 1864 Jefferson Davis and Judah P. Benjamin decided to cut the Gordian knot. They secretly agreed that the only way out was to force the South to sacrifice slavery for independence. Soon after Lincoln’s reelection, Davis dared to broach the subject of arming and freeing slaves in his message to the Confederate Congress. He framed it as a solution to the need for manpower in the army and left the irritating diplomatic problem aside. Richmond newspapers friendly to the government helped prepare the public mind by defending the idea. Benjamin was more interested in winning international recognition, but he quietly enlisted support for the idea of arming and freeing black soldiers. “Public opinion is fast ripening on the subject,” he wrote to one supporter, and the government would soon be able to inaugurate the new policy.33

In London Henry Hotze still found the whole subject of Confederate emancipation distasteful, but he dutifully published stories on the emancipation debate in the Index. Mason, who had returned from Paris to London, reported in December that the Southern Independence Association at Manchester “fully approves the proposed plan of arming the slaves.” In January 1865 he assured the home office that supporters in England agreed that “our people would have no fear of bringing our slaves into the field to fight an enemy common alike to them and to their masters” and had no doubt that “our slaves would make better soldiers in our ranks than in those of the North.” But there were, he cautioned Benjamin, grave reservations in Europe that promising freedom to enslaved soldiers would be “the first step toward emancipation” of all slaves, not least because it would cause “great mischief and inconvenience” to have so many “free blacks amongst us.”34

By early 1865 rumors of Confederate emancipation plans were coursing through Europe. Under pressure from Benjamin, Robert E. Lee endorsed the idea of emancipating those slaves willing to serve, but only, he advised, “with the consent of their owners.”35

For many Confederates, freeing slaves proved less contentious than proposals to arm them. The very idea of putting slaves on an “equal footing” with white soldiers fighting for their country was appalling to them, but the notion of giving slaves or free blacks guns was positively terrifying. Georgia’s Howell Cobb, serving as a major general, put the matter succinctly in his letter to the Confederate secretary of war: “You cannot make soldiers of slaves, nor slaves of soldiers.” “The day you make soldiers of them is the beginning of the end of the revolution. If slaves will make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong.”36

Robert M. T. Hunter, the former secretary of state, sneered at the idea of succumbing to what he viewed as the false philanthropic zeal for abolition abroad. Before a large, boisterous meeting in Richmond, he admitted that “the world, if not in arms against us, is against us in sympathy.” He summoned the white South to vindicate itself by winning victory before the “frowning face of all Europe.” “What did we go to war for, if not to protect our property?” he asked poignantly. “The shades of our departed heroes hover over us and beckon us on. . . . [T]he enemy is far spent. . . . Let us stand firm” and not “commit suicide.”37

“If the Confederacy falls,” Jefferson Davis told one stubborn senator who was certain slaves would not fight, “there should be written on its tombstone, ‘Died of a theory.’” Davis was desperate to save the South, but he was also facing a virtual mutiny against emancipation on any basis in the Confederate Congress. “If this Government is to destroy slavery,” Henry S. Foote, a Tennessee congressman, asked, “why fight for it?” “Gloom and despondency rule the hour,” Howell Cobb wrote in January 1865, “and bitter opposition to the Administration, mingled with disaffection and disloyalty, is manifesting itself.” It would be far better, he argued, “to yield to the demands of England and France and abolish slavery, and thereby purchase their aid,” than to resort to arming blacks.38

Benjamin, meanwhile, persuaded Davis that the most urgent problem they faced was not manpower but their desperate need for international support. If they conquered the diplomatic problem, he reasoned, the manpower problem would become less imperative. What Benjamin proposed was a secret diplomatic experiment in which emancipation would be promised to Britain and France in exchange for recognition. If that worked, Benjamin argued, Davis could then issue a presidential emancipation edict, justifying it as a “military necessity” dictated by national self-preservation. It had a familiar ring to it, and, indeed, Benjamin was borrowing a page from Lincoln’s book. But he took it even further by making a dubious legal argument: the very de facto status of the Confederate nation, Benjamin reasoned, permitted the president to act outside of the constitution.

Davis was worried not only about violating the cornerstone of the Confederate Constitution, but also about the political risk of flouting the will of the elected Congress. The Richmond Sentinel, widely acknowledged to be Davis’s unofficial mouthpiece, tested the waters by calling for bold action “over and above the constitution.” Remarkably, it even went so far as to recommend subordination of the South to European governments under some form of protectorate, if it came to that. “Our people would infinitely prefer an alliance with the European nations . . . to the dominion of the Yankees.” “Any terms with any other, would be preferable to subjugation to them.” As the Confederacy entered 1865 it was about to play its last card to win independence at any cost.39

OUT IN LOUISIANA, SENSING THE DESPERATE SITUATION OF THE Confederacy at the end of 1864, Confederate leaders seemed prepared to pursue a separate peace and, some later charged, to invite French recolonization. General Camille de Polignac, a French prince from a renowned noble family, had come over to serve in the Confederate army and soon rose to the rank of major general and was hailed as the “Lafayette of the South.” During that dark winter of 1864–1865, he was in Shreveport, Louisiana, and growing despondent over the South’s declining fortunes and the steady stream of deserters taking French leave of the army. The South’s last hope lay in his homeland, he told his commanding officer, General Kirby Smith, and he asked for personal leave of six months to return to France and rally support there. Smith conferred with Louisiana governor Henry W. Allen, who immediately decided to transform Polignac’s leave into an officially sanctioned diplomatic mission to save Louisiana, if not the Confederacy.40

Governor Allen and the generals decided that time and faltering lines of communication did not permit consultation with Richmond. Allen, acting on his own questionable authority, appointed his aide-de-camp, Colonel Ernest Miltenberger, as Louisiana’s envoy to France. He was instructed to accompany Polignac, whose close friendship with the Duc de Morny would allow him to serve as liaison. Allen gave Miltenberger a sealed letter to present to Napoleon III. The letter obliquely reminded the French of “the strong and sacred ties that bound France and Louisiana” and noted also “the imminent danger” a Union victory would pose to the French in Mexico. Before departing, Allen took Polignac aside and gave him instructions he dared not commit to writing. The enemy was fielding an army of “foreign mercenaries” and “kidnapped” blacks, Allen instructed Polignac to communicate, and as governor he planned to “arm the negroes” of Louisiana. “Of course,” he added almost as an afterthought, “we must give them their freedom.” Polignac and his troupe of ersatz diplomats left for Europe in early January and made their way circuitously to Matamoros, Havana, Cadiz, Madrid, and finally Paris in late March, just as the final curtain was about to close on the Confederacy.41

Unknown to Governor Allen and Prince Polignac, Benjamin and Davis in Richmond were at the same time, December 1864, secretly enlisting another Louisianan, Duncan F. Kenner, to carry out a secret mission to Europe where he would offer the promise of emancipation in exchange for recognition. Ever since Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was enacted, Kenner had tried to persuade Confederate leaders to consider a plan to arm and emancipate the slaves to save the South. Davis and Benjamin had quashed Kenner’s proposal and refused to discuss it publicly, but it now seemed to them that Kenner, one of the largest slaveholders in the South, was the perfect messenger for this desperate diplomatic mission.

Benjamin also astutely realized that Slidell and Mason would be neither willing nor credible couriers of an emancipation proposal, which would require them to repudiate everything they had been defending for the past three years. With all the intercepted correspondence between Richmond and Europe, it would prove embarrassing beyond measure and politically dangerous at home for an emancipation proposal to fall into enemy hands. It was imperative that Kenner go to Europe and that his mission should remain secret—not only from Europeans and Northerners, but also from the Confederate Congress and the people of the South.42

Benjamin sent instructions to Mason and Slidell, referring obliquely to Kenner’s mission, details of which were to be explicitly spelled out to Slidell and Mason in the encrypted instructions Kenner carried with him. The message to Slidell and Mason conveyed a strong current of resentment toward Europe, which he apparently wanted them to make known to the governments of France and Britain. “No people have ever poured out their blood more freely in defense of their liberties and independence nor have endured sacrifices with greater cheerfulness than have the men and women of these Confederate States,” Benjamin asserted. The South might have won had it only been up against the United States, he hypothesized, but Europe’s western powers have been lavishing “aid, comfort, and assistance” upon their enemy. The South had been “fighting the battle of France and England” against an aggressive enemy that now prepared to attack the French in Mexico and the British in Canada. The ulterior purpose of Lincoln’s cry, “one war at a time,” would now reveal itself in aggression against its neighbors as soon as the United States was “disengaged from the struggle with us.”

Alluding to Sherman’s March through Georgia, Benjamin complained of the barbaric assaults being carried out by “armies of mercenaries” that were now resorting to “the starvation and extermination of our women and children” and the wanton destruction of farms and cities. Slidell and Mason were instructed to ask, did the Great Powers propose never to recognize the Confederacy under any circumstances? If so, the South deserved to know. “If on the other hand,” Benjamin finally circled back to the main point of the Kenner mission, “there be objections not made known to us, which have for four years prevented the recognition of our independence . . . , justice equally demands that an opportunity be afforded us for meeting and overcoming those objections, if in our power to do so.” This was as close as Benjamin dared bring himself to spelling out the unspeakable proposition that Kenner was to explain to Slidell and Mason.43

As the Confederacy entered its eleventh hour, everything seemed to conspire to prevent the encrypted message that Kenner carried with him from ever reaching its intended audience. It was more than two full months since he left Richmond before Kenner finally crossed the Atlantic, and his troubled journey was symptomatic of the failing fortunes of the Confederate nation. Fort Fisher, which protected Wilmington, North Carolina, the last Atlantic port open to the Confederacy, fell to Union forces on January 15, 1865. Rather than run the blockade and go by way of the Caribbean, Kenner decided to embark from New York. It was highly risky. He was well known and easily recognized, not least by his very prominent bald head. He traveled incognito under an assumed name and wearing an absurd-looking brown wig. He hid out in the Metropolitan Hotel in New York, waiting to hear the results of an ill-fated peace conference that took place between Union and Confederate officials at Hampton Roads, Virginia, on February 3. One week later he boarded a ship for England. During the voyage he dodged federal officials on board by pretending to be a Frenchman. He arrived at Southampton on February 21 and hurried to London, expecting to find Mason, only to discover he was in Paris with Slidell. Kenner sent a telegram to Slidell, asking that Slidell, Mason, and Mann meet with him in Paris.44

By the time Kenner arrived in Paris on February 24, rumors of some major Confederate diplomatic move had surfaced in the European press. They may have been deliberately planted. Hotze had already run a story in the Index, anticipating “quite a turn to affairs in America” as a result of secret negotiations. In Paris Union envoy John Bigelow was hearing rumors in late January that England and France would “unite in recognizing the Southern Confederacy on condition that they will emancipate and arm their slaves.” “I mention this rumor,” he wrote to Seward, “not out of any respect for it, but to show . . . of what contortions the wounded carcass of secession is capable in its expiring agonies.”45

Kenner met Mason and Slidell at the latter’s office, a room in the sumptuous Le Grand Hotel, a palatial facility built as part of Baron Haussmann’s redesign of Paris. Kenner explained to Slidell and Mason the purpose of his mission, which left both men stunned. Sensing their opposition, Kenner asked Slidell’s secretary to decode the encrypted instructions signed by President Davis. Letter by letter, sentence by sentence, the instructions were slowly deciphered until Slidell and Mason were forced to confront the unpleasant reality that their government was about to sacrifice the very reason for its being.

The distraught diplomats were irritated by the messenger as much as by the message. True to character, Slidell demanded to know why Davis would send over Kenner when the South had seasoned diplomats in place. The answer to that became obvious when Mason refused outright to execute the plan. Kenner was prepared for that possibility. On Benjamin’s advice he had been given power to dismiss any diplomat who refused to cooperate, and he let Mason know that. Mann, arriving late, quickly read the mood and fell in line with Kenner and the home office.46

Slidell and Mason, however, were not about to allow themselves to be treated as lackeys by the likes of Kenner, whatever powers the president had vested in him. They had long since made up their minds that any offer of emancipation would be fruitless. What ensued over the next few days amounted to Mason and Slidell effectively sabotaging the Kenner mission. Kenner deserved some of the blame, for he inexplicably deferred to the two veteran diplomats and did not take part in negotiations in Paris or London.

Kenner, Slidell, Mason, and Mann huddled in Paris for nearly a week before deciding to approach Britain first. No soon had Kenner and Mason arrived in London on March 3 than Mason began second-guessing the plan and managed to persuade Kenner to reverse course and have Slidell, who remained in Paris, go first. On March 4 Slidell met briefly with Napoleon III, who, almost routinely by now, declared that he would not act without England’s cooperation. Slidell took the opportunity to tell him frankly the terms of Kenner’s proposal, and he asked directly whether an offer of emancipation would make any difference to France. According to Slidell’s account, which conveniently sustained his own argument against emancipation, Napoleon III told him the slavery question had never entered into France’s policy on the American question. Maybe it would make a difference to the British, the emperor casually added.47

Inexplicably, Slidell delayed two days before reporting to Kenner and Mason, who waited anxiously in London. More than a week passed before Mason set up an unofficial interview with Palmerston. More than two and a half months had passed since Benjamin and Davis had authorized the Kenner mission. Here was the Confederacy’s last chance for recognition among the powers of the earth.

Yet Mason seemed in no great hurry and admitted to waiting “a few days” before arranging a private interview with Lord Palmerston. Late in the morning on March 14, Mason went alone without Kenner to meet with Palmerston at his private residence, Cambridge House, at 94 Picadilly. There in Palmerston’s home, Mason, with full authorization to spell out an exchange of emancipation for recognition, managed to turn what should have been a plea for British aid into a threat of war. In fairness, he was following Benjamin’s instructions to warn Britain and France of Northern aggression once the South was conquered. But in Mason’s hands, it sounded like a Southern threat. If forced to choose between the “continued desolation of our country, or a return to peace through an alliance committing us to the foreign wars of the North,” he warned the prime minister, the South might choose to side with the North against Europe.

Turning at last to the urgent matter at hand, the emancipation proposal, Mason turned strangely reticent. He could do no more than repeat, more than once, the opaque language of Benjamin’s written instructions: if there might be “some latent, undisclosed obstacle on the part of Great Britain to recognition, it should be frankly stated and we might, if in our power to do so, consent to remove it.” Mason simply could not bring himself to speak the actual words—slavery, emancipation, recognition— that would have made the Confederate proposal clear, even as he pressed Palmerston to speak frankly.

As Mason later painfully admitted to Benjamin, he had not “unfolded fully” the exact terms of the proposal: “I made no distinct proposal,” he admitted in his encrypted dispatch to Benjamin. Indeed, it was as though he refused to decode the desperate plea for help Kenner had been sent to Europe to deliver. Mason later explained candidly that he was simply dumbstruck by “extreme apprehension” that word of this conversation might reach the ears of their enemies and that “the mischief resulting would be incalculable.” He was tongue-tied by fear of humiliation and dishonor—of the South and of himself—once it became known that the Confederacy was repudiating the cornerstone on which it had proclaimed itself a nation.48

Mason dallied in London another two weeks, wracked with self-doubt that he had squandered his chance with Palmerston by not being forthright. He sought counsel with the Earl of Donoughmore, “a fast and consistent friend to our cause,” to ask whether a more forthright offer of emancipation might make a difference. Donoughmore replied that perhaps earlier, in the late summer of 1862 when Lee’s “army was at the very gates of Washington,” it might have made a decisive difference; “but for slavery,” the South “should then have been acknowledged.”

“But for slavery” the South might not have tried to secede or plunged into the chasm of civil war so willingly. Mason sighed, replying with a Latin proverb: Sic transit Gloria Mundi (Thus passes the glory of the world). Thus also passed the Confederacy’s bid for independence. Mason’s March 31 explanation of his meetings in London arrived in Richmond well after Benjamin and Davis had abandoned the capital as it went up in flames.49

Meanwhile, Prince Camille de Polignac, the noble emissary from Governor Allen in Louisiana, finally arrived in Paris sometime around March 22. He was counting on his friendship with the Duc de Morny, Napoleon III’s half brother, but he had died earlier that month. Polignac arranged an interview with the emperor, who received him cordially, at least until the conversation turned to official matters.

Polignac waxed eloquent about the Southern people’s determination to fight on and told the emperor that their “ties of blood had ever since kept alive a natural sympathy with France among the descendants of the first settlers.” Napoleon sat in studied silence. Polignac then told him that he came with an emissary bearing a letter from the governor of Louisiana. “What does he tell me in that letter?” the emperor asked. Polignac asked to return the next day with Colonel Miltenberger, who handed the sealed envelope to Napoleon. The emperor coolly laid it on the table unopened and, without even inviting the Louisiana envoys to sit down, told them that, although he had wanted to intervene on behalf of the South, Britain’s reluctance prevented him from doing so. Now it was too late.50

Years later, Robert Toombs lamented that the South had not promised an end to slavery earlier in the war, for both France and Britain would have rushed to its support. John Bigelow was not about to let that rest. If the South had been willing to end slavery, he replied to Toombs in a popular magazine, “there would have been no war, and the Confederate maggot would never have been hatched.”51