Figure 14.1 The spectrum of legal forms: Share of different legal forms of social enterprises across nine countries (N = 1,045)

SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP

Research as Disciplined Exploration

Johanna Mair*

SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP—THE PRACTICE of addressing social problems by means of markets—has become an increasingly prominent approach to engaging in private action for public purpose. In this chapter, I will refer to a social enterprise as an organization that practices social entrepreneurship. Social enterprises—broadly understood as organizing tools to address a wide range of social problems (including homelessness, integration of refugees, elderly care, cyberbullying, and mental health) by relying on market-based activities—have become a recognized community of organizations across geographies. Over the last decade, social enterprises have attracted new forms of capital in the form of impact investment or venture philanthropy (Letts, Ryan, and Grossman 1997; Hehenberger, Mair, and Seganti 2018; Brest, Chapter 16, “The Outcomes Movement in Philanthropy and the Nonprofit Sector”); they have become partners or competitors of businesses in creating and addressing new markets (Seelos and Mair 2007); and they have been courted by policy makers as cost-effective providers of social services (Teasdale 2012; Grohs, Schneiders, and Heinze 2017).

To understand the global enthusiasm for social enterprises, it is helpful to revisit how social entrepreneurship as a field of practice has evolved over the last two decades. First, although hardly anyone has argued that social enterprises constitute a new phenomenon, early writings portrayed them as blurring the boundaries between the public, private, and social sectors and as being more effective than existing approaches within each of those sectors (Dees 1994, 1998). Second, associating social enterprises with innovation (Dees and Anderson 2006) and with the ability to address newly emergent or stubbornly persisting social problems in novel or unconventional ways (Seelos and Mair 2005) fueled hopes and sparked interest among stakeholders who previously focused on charity or corporate social responsibility (CSR) as the private form of tackling social problems and on welfare as the public form of tackling such problems. And third, the systematic scouting and celebrating of social enterprises by intermediary organizations such as Ashoka and Echoing Green, along with the addition of courses on social entrepreneurship in business schools and schools of public policy, shaped a distinct professional identity and a set of career paths for social entrepreneurs.

The trajectory of social entrepreneurship as a field of practice has been marked by debates over the meaning of social entrepreneurship—debates that often take the form of open contestation and ideological conflict. These debates have resulted in a tacit agreement to use the label in ways that leave room for ambiguity (Chliova, Mair, and Vernis forthcoming). For some observers, social enterprises heroically step in where governments and markets have failed to address social problems. These observers regard social entrepreneurs as change makers equipped with a unique ethical fiber (Drayton 2006) or as leaders who courageously alter an “unpleasant equilibrium” in society (Martin and Osberg 2007:33). Others interpret the rise of social enterprises as the triumph of a strain of neoliberal thought that idealizes markets and business as drivers of social change (Dey and Steyaert 2010). These observers believe that social enterprises not only threaten the legitimacy of government and organized civil society as the most effective providers of social services but also pose a threat to democratic principles (Ganz, Kay and Spicer 2018).

Research on social enterprises has not been shielded from these debates. Early research efforts have devoted ample ink and substantial effort to clarifying definitions (Zahra et al. 2009; Light 2008; Austin, Stevenson, and Wei-Skillern 2006; Mair, Robinson, and Hockerts 2006) and to arguing for or against a unifying theory of the social enterprise (Santos 2012; Dacin, Dacin, and Tracey 2011). An unintended consequence of these efforts is that scholars have lost sight of the need to situate social enterprises and the problems they address in space, time, and institutional context. My colleagues and I joined this conversation by proposing a pathway for research that explicitly builds on the embeddedness of social enterprises in societal and institutional realities as “a source of explanation, prediction and delight” (Mair and Martí 2006:36) and advocates for a deeply contextualized study of those enterprises (Seelos et al. 2011). We portrayed social enterprises as organized efforts to address social problems by combining and recombining various institutional and organizational features in novel and unconventional ways (Mair and Martí 2009). The theoretical potential inherent in the study of social enterprises, we argued, lies in examining the process by which they address social problems in context and not devoid of context (Mair 2010; Mair and Rathert forthcoming). Scholars, we further argued, can harness this potential most productively not by developing a grand theory of social entrepreneurship but rather by developing midrange theories that refine, adapt, and recast existing theories.

Over the last decade, research on social enterprises has attracted interest from scholars across multiple disciplines, including law (Brakman Reiser 2013), history (Hall 2013), sociology (Vasi 2009; Galaskiewicz and Barringer 2012), and economics (Besley and Ghatak 2017). Management journals in particular have become a popular outlet for studies of social enterprises. In-depth case studies have helped unpack the unconventional ways in which social enterprises create impact with respect to a broad range of social problems (Seelos and Mair 2017), including poverty (Mair, Martí, and Ventresca 2012), inequality (Mair, Wolf, and Seelos 2016), and drug addiction (Lawrence and Dover 2015). Studies focusing on specific problem domains such as work integration (Pache and Santos 2013; Crucke and Knockaert 2016) and microfinance (Battilana and Dorado 2010; Zhao and Wry 2016) have helped clarify realities in those domains. Most work in this field, however, has focused less on the challenges or problems that social enterprises address than on how social enterprises are organized (Battilana and Lee 2014; Ebrahim, Battilana, and Mair 2014). Case studies on individual enterprises, for example, have exposed organizational challenges, struggles, and failures (Smith and Besharov 2019; Tracey and Jarvis 2006). This productive stream of work has predominantly deployed perspectives and concepts related to different institutional logics, and it has portrayed social enterprises as organizations that combine a welfare logic and a commercial logic while pursuing both social and commercial goals (Battilana et al. 2015; Pache and Santos 2013; Besharov and Smith 2014; Wry and York 2017). This emphasis has forcefully directed attention to conflicts arising from a duality in logics and has foregrounded the need to achieve balance in the pursuit of social and business goals. For example, in a thoughtful case study on Digital Divide Data, a digital outsourcing company that offers training and employment to disadvantaged youth in developing countries, Wendy K. Smith and Marya L. Besharov (2019) portray social and business goals as guardrails for social enterprises. These guardrails demarcate a confined space for maneuvering that is filled with paradox and tension—a space where social enterprises experiment with practices, shape and reshape their identity, and confront demands from external stakeholders. Work of this kind has helped bring the study of social enterprises into the academic mainstream and position it as a legitimate topic for management research. However, this trend has limited organizational scholars’ interest in this field to a narrow set of theoretical questions about how social enterprises cope with dual logics.

In seminal studies on organizations (Blau and Scott 1962), the pursuit of multiple and potentially conflicting goals has been identified as a defining characteristic of organizations in general. Seeing social enterprises merely as sites where dual goals are at play may therefore prevent us from clarifying whether and how they are distinct from other organizational forms. The duality of social and commercial goals, moreover, is not unique to social enterprises but is intrinsic to organizing in almost all institutional domains that entail a public purpose, such as health, education, and the arts. Finally, limiting the scope of social enterprises to the pursuit of commercial and unspecified social goals may prevent the development of a more comprehensive understanding of the role that social enterprises play in society and the economy—a role that can vary in time and space. Relying on common or widely accepted perspectives can limit theorizing as disciplined imagination (Weick 1989) because it constrains the approach that scholars take to seeing and potentially limits the creativity that they bring to looking—to their choice of methods to use in the search for explanation and truth (Abbott 2004; Schneiberg and Clemens 2006).

The objective of this chapter is to inspire theorizing by revealing the organizational realities of social enterprises across different geographies, given that the meaning of public purpose varies across problem domains and local context. Until recently, systematic and comparative analysis of how institutional context affects and is affected by social enterprises has been stalled by a dearth of available data. Existing comparative studies are often based on datasets collected for different purposes, as in the case of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) database (Stephan, Uhlaner and Stride 2015; Kibler et al. 2018), or are designed to fit well-rehearsed theories that originated in political science or the study of civil society organizations. Janelle A. Kerlin (2010, 2013), for example, studies the emergence and prevalence of social enterprises as a by-product of the specific welfare regime (Esping-Andersen 1990) or the social origin (Salamon and Anheier 1998) of the country in which they operate. Although both of those approaches have helped advance a comparative research agenda, they can be limiting. The former approach limits the range of questions that scholars can meaningfully and validly address and prevents scholars from accurately capturing the organizational realities of social enterprises; the latter approach prevents them from detecting meaningful differences among social enterprises within the same country context.1

In this chapter, I report on insights and patterns emerging from data collected in a large-scale study of more than one thousand social enterprises in nine countries. (Joining me in carrying out this study was a group of scholars that included Marieke Huysentruyt, Ute Stephan, Tomislav Rimac, and others. See the following text for more information on this study.) Inspired by Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland’s exploration of the geography of plants, in this chapter I seek to uncover features that social enterprises have in common and to understand how they vary when they “grow in a different habitat” (Humboldt and Bonpland 1807). My argument is that embracing rather than taming the diversity among social enterprises facilitates future theorizing. A disciplined approach to exploring whether and how social enterprises vary across context helps identify features of a social enterprise archetype and to inspire the search for real-types that complement ideal-type schemes to categorize social enterprises. This approach also helps clarify the role that social enterprises play in the economy and society and how this role differs across contexts. Finally, disciplined exploration generates empirical evidence that can inform and refine ideological debates on social enterprises as well as popular images of those organizations.

The Scope of Exploration

From April 2015 to December 2015, I was part of a consortium of scholars that undertook a journey to explore the variety of social enterprises across different geographical and institutional contexts. The objective of our study on Social Entrepreneurship as a Force for More Inclusive and Innovative Societies (SEFORÏS) was to advance research and to inform policy by developing comparative knowledge on social enterprises. In total, we surveyed directors or managing directors from 1,045 social enterprises in China, Germany, Hungary, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. In addition, we collected qualitative data and conducted a comparative case study project that covered three social enterprises in each country. (See http://www.seforis.eu for detailed reports on all nine countries.)

The choice of sampling method was critical to our study. Because official and comparable registrars for social enterprises or tax codes in and across countries are largely missing, we opted to employ respondent-driven sampling (RDS), an approach used in public health and sociology (Heckathorn 1997) to identify social enterprises and to obtain a representative sample of them in each country. We kept the selection criteria for the sample to a minimum, thereby ensuring comparability across context without compromising our ability to explore heterogeneity. To qualify for the study, an organization had to (1) have a social mission crosschecked in multiple ways by our trained interviewers; (2) engage in revenue-generating activity involving the sale of products or services, with the proceeds of that activity accounting for at least 5 percent of total revenue; and (3) employ at least one full-time-equivalent (FTE) employee. We used validated scales as well as tailored and open-ended questions in the interview and survey instruments we built. Interviews with the director of each social enterprise lasted an average of ninety minutes and were complemented by a thirty-minute online survey. We trained and coached about thirty interviewers, who conducted interviews in a local language and followed strict rules of back-translation.2 More than 30 percent of the interviews were cross-checked and independently coded by a second rater. To triangulate interview data, we also collected data on matters such as mission, employment, and finances. For a more extensive discussion of our methods and how we applied RDS, see Marieke Huystentruyt and colleagues (2017).

In hindsight, many of the choices we made in studying the organizational and local realities of social enterprises resemble the approach that Humboldt and Bonpland followed in their landmark study of the geography of plants. In particular, our approach was informed but not constrained by existing categorization schemes for institutional context and organizational form. By starting from, but not limiting ourselves to, a set of three characteristics that defined qualifying social enterprises, we enhanced our ability to uncover emerging features, forms, and patterns. Through this way of looking, we tried to mitigate (even if we could not completely avoid) biases that could stem from the theories that scholars typically use (Schneiberg and Clemens 2006), and we opened up an opportunity to see differently—and to see different things.

The Landscape of Social Enterprises—Emerging Patterns

Evidence from our study helps to reveal the economic and societal role of social enterprises. In 2014, the social enterprises that we surveyed jointly served more than eight hundred million beneficiaries, generated more than €6 billion in revenue, earned nearly €70 million in surplus/profits, and employed slightly more than half a million people. (See Huysentruyt, Mair, and Stephan 2016 for a more detailed summary of our high-level findings.)

One size does not fit all for the social enterprises in our sample. Social enterprises across but also within countries differed considerably in terms of revenues and numbers of employees. Although in Germany, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom more than 40 percent of all social enterprises had revenues of more than €1 million, in China and Russia more than half of all social enterprises had revenues of less than €80,000.3 The median count for FTE employees ranged from 7 in Sweden to 24 in the United Kingdom. The median count for volunteers varied substantially across countries as well, ranging from 3 to 3.5 in Russia and Sweden to 15 in China and Romania. One third of social enterprises in the survey did not involve volunteers in their work.4

Similarly, one form does not fit all for the social enterprises we surveyed. We found that social enterprises use a variety of legal forms and are not bound by the legal form that they adopt. The roles that they play in the economy or society are equally diverse. They are active participants in the market for public purpose, but how they engage in this market varies considerably across problem domain and country context. They are inherently social with regard to what they do and how they operate. This social footprint in turn reflects a local imprint; it is shaped by social, economic, and political realities and by historical institutional legacies. Social enterprises also take an active role in shaping their institutional environment in ways that go beyond the delivery of goods and services. Finally, their decision to pursue a social mission by commercial means does not turn them into battlefields of competing logics or sites of unresolvable paradox. However, our research on social enterprise does show that multiple mandates can create conflict.

In the following sections, I further unpack these findings. In doing so, I refer to existing research on nonprofit organizations in an effort to inform and inspire future theorizing.

Legal Form as Choice

For researchers on nonprofit organizations, legal form is the defining feature of the organizations they study. Yet legal form is neither a uniform nor a defining characteristic of social enterprises, and the choice of form depends on a number of factors, including both institutional aspects (such as the repertoire of available forms and the legitimacy associated with those forms) and pragmatic aspects (such as beneficiaries’ ability to pay for services and the ability of an organization to access funds that may be legally restricted to a specific form).

Our project allowed us to systematically investigate patterns in the legal forms that social enterprises chose across nine countries and to explore the factors that determined such choices. From our case studies, we learned that legal form strongly influences the nature of these organizations. Apart from questions of personal liability, risk, and taxation, the legal form of a social enterprise affects how outside parties perceive the organization, the funding sources it can tap, and the stakeholder groups with which it can and must engage (Mair, Wolf, and Ioan 2020; Wolf and Mair 2019). As Figure 14.1 shows, the social enterprises in our sample adopted legal forms associated with different tax regimes. Nonprofit forms (50.14 percent)5 and for-profit forms (26.70 percent)6 accounted for most of the organizations in the sample. In addition, 5 percent of social enterprises adopted forms associated with cooperatives, and a smaller share of them adopted hybrid forms such as the community interest company (CIC), a legal form introduced in the United Kingdom in 2005 that requires reinvestment of profits for the public good. However, 13 percent of organizations in the sample did not rely on a single legal form but instead chose a dual arrangement that allowed them to combine legal forms within and across nonprofit and for-profit legal statuses.

The dominance of nonprofit legal forms in our sample masks important differences across countries. Figure 14.2, which shows the distribution of legal forms within and across countries, reveals patterns that call for a detailed inquiry into the role that institutional context and historical legacies play in the choice of legal form among social enterprises. In China and Russia, the majority of organizations adopted a for-profit legal form, whereas in Germany, Hungary, Portugal, Romania, Spain, and Sweden, nonprofit legal forms predominated. In Portugal and Spain, a comparatively higher percentage of social enterprises opted for historically available forms, such as cooperatives. The United Kingdom stands apart from other countries because the majority of social enterprises there combined different legal forms.

Figure 14.1 The spectrum of legal forms: Share of different legal forms of social enterprises across nine countries (N = 1,045)

Figure 14.2 Patterns of legal forms: Share of different legal forms of social enterprise by country (N = 1,045; empty categories not shown)

In countries other than the United Kingdom, a relatively small share of social enterprises combined legal forms. In China (17.6 percent), Germany (12 percent), Portugal (14.2 percent), Spain (11.2 percent), and Sweden (24.3 percent), a modest portion of social enterprises adopted a second legal form. Qualitative insights from our case studies suggest that social enterprises take this step in order to harness the legal opportunities and advantages associated with different legal forms. Combining legal forms allows social enterprises to increase access to resources and to align internal operations with outside expectations. For example, although a for-profit legal form may allow an organization to successfully operate in a market environment and to increase and diversify its revenues, a nonprofit legal form signals its commitment to a social mission. As a founder of a social enterprise in Germany explained:

We did this [combining legal forms] so that people take us seriously. We do not really need this legal form for our work. But people think only a nonprofit is appropriate for this. If we say we are a for-profit, they think we want to make money out of it.

Auticon, a social enterprise in Germany offering IT service delivered by people with autism, operates as a business (GmbH) but set up a nonprofit sister organization (gGmbH) to offer training services for people on the broader autism spectrum. Auticon uses the for-profit form to signal competitiveness in its service delivery, and it uses the nonprofit form in order to remain a respected player among organizations that serve people with autism.

Social enterprises seem to make do with the legal forms available in their country and to adopt formal arrangements that are suitable to the pursuit their goals. When asked about priorities for legal change in their country, only 11 percent of survey respondents cited the creation of a specific legal status for social enterprises as a priority. In countries like the United Kingdom, where special legal forms are readily available, social enterprises seem to prefer combining widely recognized forms that are already in common use. One potential explanation for this preference is that combining traditional legal forms gives social enterprises more flexibility to add activities that either rely on donations or have the potential to generate revenues.7

We also detected a correlation between the age of a social enterprise and its choice of legal form. Younger organizations seem to be more likely to adopt a for-profit legal form. In our sample, nonprofit organizations were on average twenty-one years old, and for-profit organizations were on average fifteen years old.

Participating in the Market for Public Purpose

Our project allowed us to uncover patterns in how social enterprises participate in the market for public purpose and how they define their role in that space. (I define “market for public purpose” as a social space and area of exchange that encompasses both private and public efforts to address social problems of public interest.) Next I will use data on sources of finance, interaction with governments, and competitive dynamics to describe these patterns.

Financing Social Enterprises

Seventy percent of the social enterprises in our sample relied on selling products or services as their primary mode of financing operations. In all nine countries, that activity was the most important mode of financing operations and the most important source of liquidity for social enterprises. On average, social enterprises financed 57 percent of their activities this way—a level far above our selection cutoff point of 5 percent. Of all countries in our study, Spain was the one in which social enterprises were most reliant on this form of financing; that source accounted for almost 70 percent of total financing in that country. Grants, meanwhile, represented the second most important source of financing (26 percent of total financing, on average) for social enterprises in our sample. In Romania, financing through grants was nearly as important as sales. Financing through equity investments played only a minor role in all countries: the cross-country average for that source was less than 4 percent of total financing. Only in China did investments in the form of equity from a founder make up a considerable portion (17 percent) of financing for social enterprises. Donations constituted a notable source of financing (between 10 percent and 11 percent) in three countries: Germany, Romania, and Russia. Loans and membership fees played a negligible role in social enterprise financing, except in Sweden, where 4 percent of social enterprises deployed loans, and in Hungary, where 3 percent of social enterprises relied on membership fees. Figure 14.3 provides a comparison of financing sources across countries.

Interacting with the Public and Private Sectors

The research on nonprofit organizations documented in the first and second editions of this handbook focused on understanding what distinguishes nonprofit organizations from other forms of organized action for the public good—particularly forms that exist in the business and government sectors. Implicit in these research efforts was the assumption that nonprofit organizations constitute a “third” or “social,” sector. Social enterprises have been portrayed as entities that blur the boundaries between the three sectors (Dees and Anderson 2002). More recently, commentators have made the case that social enterprises form, and should be seen as, a fourth sector (Sabeti 2011). Our project offers empirical insights that suggest an alternative or complementary perspective. In this perspective, social enterprises constitute a community of organizations that pragmatically navigate markets for public purpose in ways that reflect the context in which they address social problems.

Figure 14.4 shows patterns of sales by and grants to social enterprises across countries. An analysis of these two dominant forms of social enterprise financing illuminates how social enterprises interact and transact with the public and private sectors.

In China, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Spain, and the United Kingdom, social enterprises mainly sell to private organizations or individuals. Sweden is the only country where the government is the dominant buyer of products and services offered by social enterprises. An analysis of grants received by social enterprises complements the analysis of sales and helps clarify the realities of the markets for public purpose in which social enterprises operate. Figure 14.4 shows how patterns of grantmaking to social enterprises vary considerably across countries. In Hungary, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, grants from government sources accounted for 15 percent to 32 percent of financing and outweighed grants from the private sector. Such favorable grant schemes appeared to be absent in China, Germany, Hungary, and Romania, where grants from private sources outweighed grants from public sources.

Analyzing patterns of sales to and grants from private and public sources may help explain how social enterprises navigate the space between the public and private sectors and how this relationship changes over time.

An examination of how social enterprises interact and transact with government is especially revealing. See Figure 14.5 for an analysis of sales to and grants from governments across countries.

We found striking cross-country differences in the role that government plays in the life of social enterprises. In Hungary and Sweden, the government played a dominant role both as a buyer of social goods and services and as a provider of grants. In China and Russia, governments played a considerably reduced role. But we also found notable differences between those two countries. In China, selling to the government was more prevalent than receiving grants, whereas in Russia, the opposite pattern was evident.

Such patterns reflect not only the context in which social enterprises operate but also the priorities of governments and the range of private organizations that pursue public and social purposes. Exploring these patterns systematically and over time will help clarify the extent to which governments “use” social enterprises to outsource their obligation to address social problems. Further exploration of this kind will also help clarify the effect of austerity programs and financial crises on how social enterprises interact with governments.

Finally, these patterns need to be viewed not in isolation but in the context of how other public or private organizations address the same social problem or operate in the same problem domain.

Competing on Public Purpose

In all countries covered by our study, a variety of private and public organizations are active in social problem domains. To probe for patterns of competition among those organizations, we asked social enterprises to specify entities that provide products or services that are similar to their offering. In China, Russia, and the United Kingdom, social enterprises identified businesses as the most dominant type of competitor; in Germany, Hungary, Portugal, Romania, and Sweden, they identified nonprofit organizations; and in Spain, they identified other social enterprises. A large majority of social enterprises across all countries indicated that they did not regard government or public sector service providers as a competitor. On average, 20 percent of surveyed social enterprises reported that they did not face competition at all. This finding corroborates the view that social entrepreneurship can be understood as an activity that addresses newly arising or stubbornly persistent social problems in novel ways and by relying on unconventional business or organizing models (Seelos and Mair 2007; Mair, Battilana, and Cardenas 2012). Overall, these findings suggest the need for a more systematic assessment of the relationship between context, problem domain, and the extent of novelty or unconventionality in social enterprises (Mair, Rathert, and Huysentruyt 2018).

Seminal work by Max Weber ([1922] 1978) and Paul J. DiMaggio and Walter W. Powell (1983) identified competition as a force that fosters homogeneity among organizations that share the same purpose or operate in the same field. How do patterns of competition affect the likelihood that social enterprises will adopt the same legal form? In our sample, we detected a clear difference between social enterprises that face competition from nonprofits and those that do not. When social enterprises operate in a competitive context dominated by nonprofits, they tend to be very homogenous in their choice of legal form. That context, in short, seems to create a strong bias for the adoption of a nonprofit form. Contexts marked by a high degree of competition from government are also associated with more homogeneity in the choice of legal form. When social enterprises perceive no direct competition, or when their competitive landscape is populated by organizations with a dual legal form, by for-profit entities, or by other social enterprises, the likelihood that two social enterprises will have the same legal form is much lower than it is when they operate in a nonprofit-dominated context.

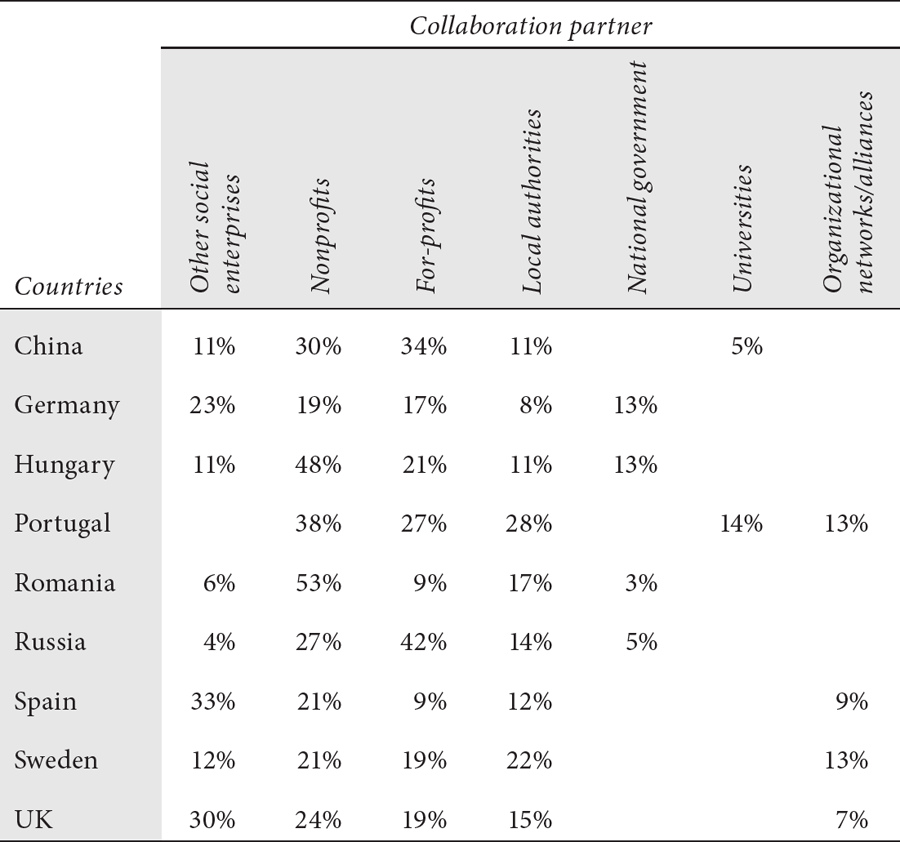

Collaborating for Public Purpose

Social enterprises not only compete but also collaborate as they tackle social problems. Data from our survey reveals that collaboration with other entities is a widely shared feature of social enterprises across countries. Only 1.1 percent of social enterprises in our sample (11 out of 1,045) reported that they did not collaborate with another organization in the last twelve months. Social enterprises in Hungary and Russia reported the highest rates of collaboration. Table 14.1 shows the entities with which social enterprises collaborated in each country in our survey and indicates patterns of collaboration with the five most frequently cited partners. These patterns vary considerably across countries. In China and Russia, partnering with for-profit organizations is the preferred mode of collaborations. In Spain and the United Kingdom, social enterprises collaborate most extensively with other social enterprises. In Portugal and Sweden, partnering with local authorities is widespread.

The Social Footprint of Social Enterprises

Social enterprises are inherently social in how they work; they collaborate with other entities. Their social nature, however, is typically associated with how much impact they create—how much progress they make in addressing a specific social problem. Not surprisingly, therefore, a shared characteristic of social enterprises is that they systematically measure and report on their social performance. About 65 percent of the social enterprises in our survey track social performance, with country-level scores on this characteristic ranging from a high of 97 percent in Portugal to a low of 48 percent in Spain. The most widely used indicator to assess social performance was number of beneficiaries or clients served, with the exception of Sweden, where measuring satisfaction of beneficiaries or clients was the most prevalent indicator. The use of specific indicators also varied across countries; in China, for example, number of volunteers was a popular indicator, while in Portugal number of people empowered was used extensively. In other countries, such as Germany, most social enterprises seemed to have settled using on a repertoire of indicators that has become standard within their country.

Although recent scholarship has started to investigate social performance in different countries, including Japan and the United Kingdom (Liu, Eng, and Takeda 2015) and France (Battilana et al. 2015), we still lack a systematic account of the range of social problems that social enterprises address as a community of organizations and how the problem domains they inhabit vary across geographies. We also have no systematic account or mapping of people and communities that benefit from social entrepreneurship. An analysis of the problem domains in which social enterprises are active and of the beneficiary patterns in different countries, therefore, can provide empirical insights that will advance our theorizing on the relationship between social enterprises and the market of public purpose.

Table 14.1 Patterns of collaboration by social enterprises across countries

Sample sizes: China: N = 102, Germany: N = 107, Hungary: N = 122, Portugal: N = 111, Romania: N = 109, Russia: N = 104, Spain: N = 125, Sweden: N = 106, United Kingdom: N = 135

Mapping Social Problem Domains

I concur with Howard S. Becker that it may be impossible to define what a social problem is (Becker 1966). Scholars, however, have succeeded in bringing some clarity to this question. Social problems involve harmful conditions and the people exposed to these conditions (Loseke 2003). They “have to be seen in an historical context and in a structural dimension interacting with cultural interpretations of experience” (Gusfield 1989:431). Social problems are defined collectively (Blumer 1971). The work of defining social problems occurs in public arenas “where social problems are discussed, selected, defined, framed, dramatized, packaged and presented” (Hilgartner and Bosk 1988:59). Participants in those arenas and the patterns that characterize their participation vary across cultural contexts and can include public agencies, media, courts, civil society, social movements, and religious institutions. By taking an active part in these arenas, social enterprises identify and specify social problems (Mair, Battilana, and Cardenas, 2012). Through this process, they attach meaning to social problems, make social problems salient, and amplify or diminish the halo around social problems (Mair and Rathert forthcoming).

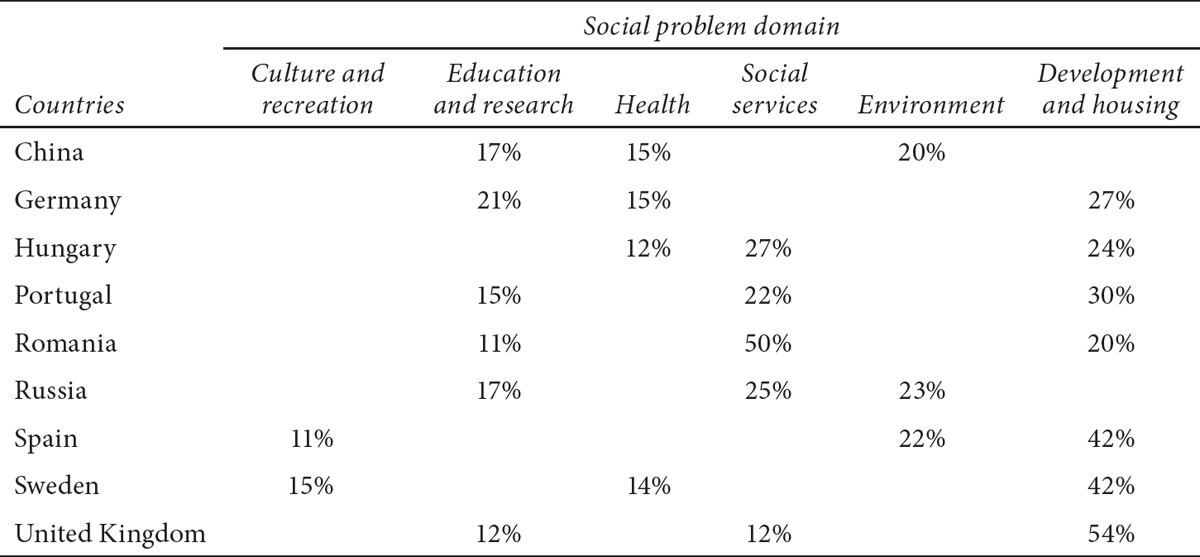

We found that social enterprises are active in a diverse array of problem domains and that these domains vary across countries. Applying the categorization scheme of problem domains widely used by scholars to compare nonprofit organizations across countries—the International Classification of Nonprofit Organizations (ICNPO) (Salamon and Anheier 1997; see also Anheier, Lang, and Toepler, Chapter 30, “Comparative Nonprofit Sector Research,” for a review and critique)—we observed certain domains that social enterprises inhabit in almost all countries and other domains that constituted a natural habitat for social enterprises in specific countries. Table 14.2 shows the distribution of the three most cited problem domains in each country.

Table 14.2 Distribution of problem domains for social enterprises across countries

Sample sizes: China: N = 102, Germany: N = 107, Hungary: N = 122, Portugal: N = 111, Romania: N = 109, Russia: N = 104, Spain: N = 125, Sweden: N = 106, United Kingdom: N = 135

Development and housing represented a prominent domain in all countries except China and Russia. Among social enterprises in Germany, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, it constituted the most cited category. Education and research and social services were also widely cited domains in several countries. A focus on education was most pronounced in Germany, and a focus on social services was most pronounced in Romania. A focus on social services was much less pronounced in Germany, where the provision of social services is largely in the hands of six publicly funded social welfare organizations (Wohlfahrtsverbände) (Anheier and Salamon 2006). We found that environment constituted an important problem domain for social enterprises in China, Russia, and Spain but not in other countries. In all countries we studied, health constituted a popular domain. However, only in China, Germany, Hungary, and Sweden did health appear as one of the three most cited domains for social entrepreneurship. Culture and recreation constituted a salient domain for social enterprises only in Spain and Sweden.

Slightly more than 5 percent of the social enterprises in our sample operated in more than one of the domains identified by ICNPO. Within a given domain, however, social enterprises typically engaged in multiple activities, which in turn often involved different beneficiary groups. On average, social enterprises in our sample engaged in three to four activities. Thus, although social enterprises may not be diversified at the domain level, they are diversified in how they operate within a domain. Simply relying on domains to categorize social enterprises may mask important nuances in what they do—in particular, how they address a social problem and for whom they create impact—and thus prevent scholars from seeing how novel or unconventional they are. Relying solely on existing and well-vetted classification schemes such as ICNPO may also prevent scholars from advancing their knowledge base regarding the variety of private action for public purpose. In Chapter 30, “Comparative Nonprofit Sector Research,” Helmut K. Anheier, Markus Lang, and Stefan Toepler make a similar point and argue for taking other perspectives on categorization—such as those promoted by schools of comparative capitalism (Hall and Soskice 2001)—more seriously. This point is important because social enterprises do not operate in a social, economic, or political vacuum. Another way to enhance comparative understanding of social enterprises is to incorporate beneficiaries into this analysis.

Identifying Beneficiaries

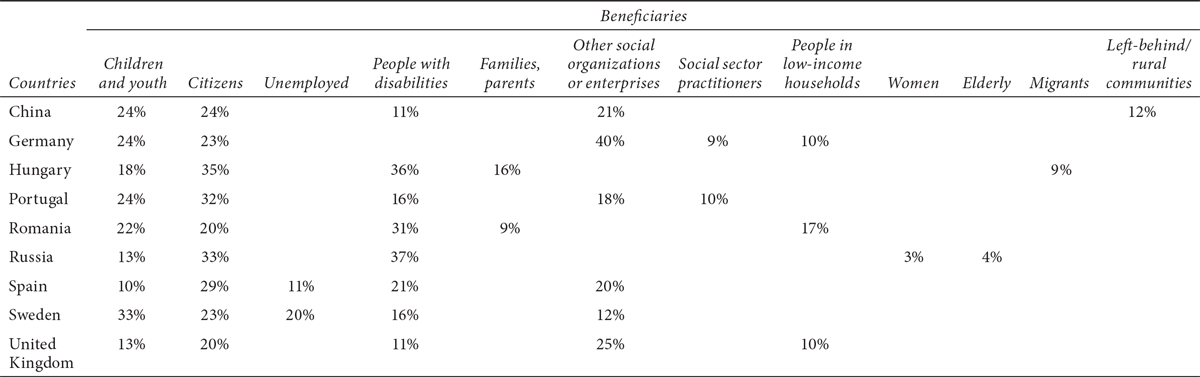

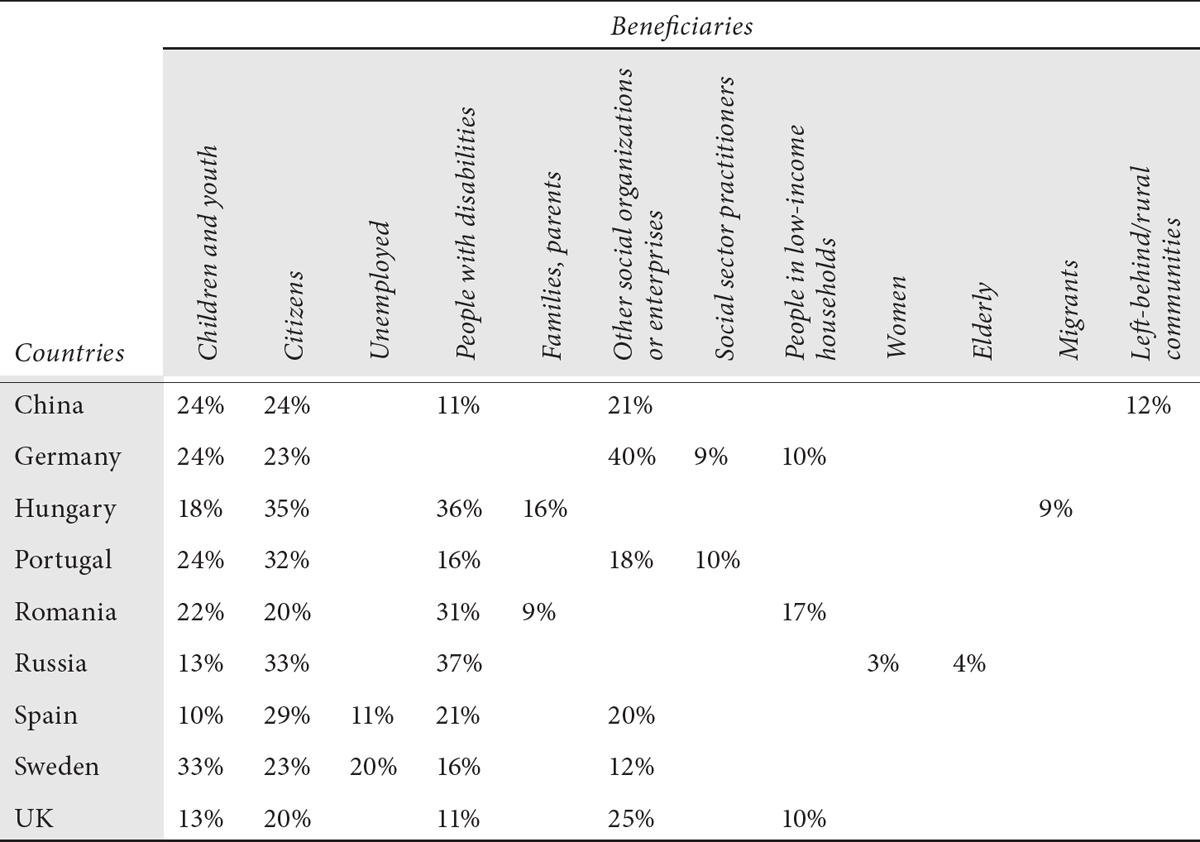

Research on social entrepreneurship has dedicated surprisingly little attention to the people affected by social problems. We asked social enterprises about the beneficiary groups that they target with their activities. The results show that they rarely focus on a single beneficiary group. On average, the social enterprises in our sample targeted approximately three beneficiary groups at the same time. Table 14.3 shows the distribution of the five most salient beneficiary groups in each country.

We uncovered similarities as well as important differences with respect to targeted beneficiaries across countries. Children and youth and citizens were among the top five beneficiary groups in all countries. The popularity of citizens as a target group suggests that social enterprises should be viewed as part of the “troubled persons” professions—occupations that help shape “the process by which publics experience social problems, interpret and imbue them with meaning, and create and administer public policies” (Gusfield 1989:432). This finding also suggests the need to undertake a more dedicated exploration of how social enterprises address social problems in new ways or how they identify new problems to address—in other words, how their activities are novel or unconventional.

People with disabilities constituted the most salient beneficiary group in Hungary, Romania, and Russia and were ranked as important in all countries with the exception of Germany. In Germany, almost half of all social enterprises identified either other social organizations or enterprises (40 percent) or social sector practitioners (9 percent) as an important beneficiary group. These findings highlight the importance of taking into account the historical legacy of how the provision of public goods and social welfare is organized. In Germany, social welfare provision is highly institutionalized; it is organized around six social welfare agencies that are associated with specific political and religious constituencies and are financed primarily through public funding, and these agencies are widely seen as the main or sole legitimate providers of social goods and services (see Grohs et al. 2017 for a more extensive discussion). Social enterprises in Germany therefore often become evangelists for an alternative approach to addressing social problems, and—as our findings show—they act as intermediaries (in the form of incubators for social ventures, for example) that deliberately position themselves as field builders.

Our analysis reveals several context-specific patterns that highlight the importance of situating social entrepreneurship in time and space. In China, for example, 12 percent of social enterprises targeted left-behind/rural communities; Russia, meanwhile, was the only country where women and elderly constituted salient target groups. In 2015, the year that we conducted our survey and the year that the refugee crisis in Europe started to unfold, 9 percent of social enterprises in Hungary (an entry point to Europe for refugees who took the so-called Balkan route in 2014) cited migrants as an important beneficiary group. In Germany (the preferred destiny of many refugees), 6.5 percent of social enterprises cited asylum seekers as an important beneficiary group. Asylum seekers are not listed in Table 14.3 as they are not among the five most salient groups in Germany.

Table 14.3 Distribution of primary beneficiaries of social enterprises across countries

Sample sizes: China: N = 102, Germany: N = 107, Hungary: N = 122, Portugal: N = 111, Romania: N = 109, Russia: N = 104, Spain: N = 125, Sweden: N = 106, United Kingdom: N = 135

Paying close attention to beneficiaries can also help scholars analyze the impact of social enterprises as a community of organizations. In many cases, we found that beneficiaries are integrated into the service delivery of a social enterprise. As noted previously, Auticon in Germany offers IT specialist services provided by people with autism. That organization and many others in our sample create direct value for a group of disadvantaged people, but their work also has systemic implications. Around one quarter of the social enterprises in the sample train and/or employ disadvantaged or marginalized individuals and/or help them find new employment opportunities. Social enterprises that engaged in activities related to employment and training (14 percent of the total) served 5.66 million beneficiaries (Huysentruyt and Stephan 2017). Our data thus corroborates anecdotal evidence that suggests that social entrepreneurship can be a tool to make labor markets more inclusive (Mair 2018).

Aligning Mission and Mandate

A social mission and the pursuit of social goals are defining characteristics of organized private action for public purposes. An important discussion in the nonprofit literature focuses on when and under which conditions a social mission is compromised to a degree that results in mission drift, mission creep, or mission displacement (Weisbrod 1998). The general assumption has been that when nonprofit organizations engage in commercial activity, the likelihood that they will drift from their social mission increases (Skloot 1987; Weisbrod 2004). More recent research on social enterprises has adopted this theme and has emphasized the difficulty of pursuing social and commercial goals in parallel. The gist of this argument is that mission drift is likely to occur when a social enterprise seeks to pursue goals associated with incompatible institutional logics—a welfare logic and a business logic, for example (Besharov and Smith 2014; Pache and Santos 2013; Mair, Mayer, and Lutz 2015). Studies have shown that this tension is present in microfinance and potentially leads social enterprises in that field to drift from their social mission (Battilana and Dorado 2010).

Although current research on social enterprises identifies the duality of social and commercial goals as a source of conflict, our data suggests that social goals are not fatally compromised by commercial activity. We used three markers to assess the relationship between commercial activity and social goals. First, scores related to the pursuit of economic and social goals—which we based on interview data and on secondary reports by our research analysts—revealed that in all countries social goals were prioritized over economic goals.8 Second, responses to one question in our survey—“If you only run your revenue generating activity, to what extent would you also generate social impact?”—yielded scores that show a strong alignment between commercial and social activities across all countries, albeit with slightly lower average scores in Hungary and Romania. And third, the fee-for-service model, which represents an integrated approach to pursuing a social goal while engaging in commercial activity, was the dominant model in almost every country in our survey. Only in Sweden was the service-subsidizing model (in which commercial activities are differentiated from social activities and used to finance the pursuit of social goals) slightly more prevalent than the fee-for-service model.

Figure 14.6 Locating sources of conflict: Accountability and reporting among social enterprises (N = 1,030; missing data)

Although we did not discover patterns of mission drift of the kind often cited in the current literature on social enterprises, we did find that social enterprises hardly operate in a conflict-free zone. Instead of a battle between institutional logics, we detected an incongruence between mission and mandate. While the mission of a social enterprise centers on pursuing social goals and achieving impact for a specific target group, a mandate is “imposed by external bodies, be they funders, governments, or standard-setting or accreditation agencies. Such organizations frequently dictate the ‘musts’ a nonprofit is required to observe or practice in order to receive funding, approval, or certification” (Minkoff and Powell 2006:593). Analyzing the entities to which social enterprises must report and to which they feel accountable (Ebrahim et al. 2014) can enable scholars to capture internal and external pressures more accurately and to detect sources of misalignment between mission and mandate. Figure 14.6 illustrates this pattern of misalignment with respect to accountability and reporting relationships.

We asked social enterprises to specify the entities to which they feel accountable and the entities to which they report. Forty-two percent of the social enterprises in our sample indicated that they feel accountable to beneficiaries, and beneficiaries was by far the most frequently stated accountability group. Yet only 11 percent of social enterprises indicated that they report their activities to beneficiaries. The opposite pattern holds for capital providers; only 18 percent of social enterprises feel accountable to this group, yet 26 percent of them indicated that they report to capital providers.

External pressures from powerful resource providers seem to prevail over internal desires and shared understandings of the parties that social enterprises exist to serve. This insight holds particular interest in the context of another finding from our research; when asked which stakeholder groups were most supportive of them, social enterprises across all countries ranked investors as the lowest group (while ranking community as the highest group, followed by media and authorities). A theoretical and empirical focus on mandates may help to interrogate the role of capital provider and to bring renewed attention to power as a crucial factor in theorizing about social enterprises.

Social Enterprises as Institutional Change Agents

As I have demonstrated, our data supports the pervasive image of social enterprises as providers of goods and services to address a social problem. However, our data also sheds light on the role that social enterprises play in institutional change. Although previous qualitative work has shown how social enterprises alter formal and institutional arrangements locally (Lawrence, Hardy and Philipps 2002; Mair, Martí, and Ventresca, 2012; Lawrence and Dover 2015; Mair et al. 2016), the role of social enterprises in affecting the institutional context in which they (and the problems they tackle) are embedded has received limited systematic attention.

We asked the social enterprises in our sample about their involvement in changing legislation or influencing policy making. More specifically, we asked (1) whether their organization has changed or helped to change legislation over the past year, and (2) whether their organization has influenced or helped influence policy making over the past year. Figure 14.7 shows the result of this inquiry.

Overall, 33 percent of social enterprises claimed to have changed or helped to change legislation over the past year. (Of that group, 56 percent targeted national legislation, 21 percent targeted regional legislation, and 16 percent targeted local legislation.) In addition, 47 percent of social enterprises reported that they had influenced or helped influence policy making over the past year. (Of that group, 55 percent influenced national policy making, 24 percent influenced regional policy making, and 15 percent influenced local policy making.)

Figure 14.7 Institutional change: Social enterprises’ involvement in changing legislation and influencing policy making

Our analysis revealed important differences across countries in whether and how social enterprises pursue institutional change efforts. We detected very high levels of policy-making influence in Germany and the United Kingdom but no influence at all in China. However, China, along with Hungary and Romania, scored high on effecting change in legislation. This involvement in changing legislation was particularly prevalent in certain countries with an authoritarian legacy—China, Romania, and Hungary—though not in Russia. We also found that data on involvement in legislative change is sensitive to contemporary events. In 2016, for example, China implemented the Charity Law, and this legislation allowed social organizations to move from a quasi-legal framework to a legitimate and regulated space. The social enterprises in China that we surveyed seemed to be actively involved in this process.

Our data supports perspectives that treat institutional change efforts as an integral aspect of the work of social enterprises (Mair and Ganly 2008; Dover and Lawrence 2012). The pervasiveness of such efforts among organizations in our sample runs counter to claims by commentators who exclude advocacy from the repertoire of activities that define social entrepreneurship (Martin and Osberg 2007). Interestingly, research on institutional change or social movements that focuses on organizations whose primary objective is to change the law or influence policy has largely failed to recognize the role of social enterprises as advocates of policy and legal change. Paying more attention to the latent goals (Mair et al. 2016) or hidden transcripts of social enterprises (Scott 1990) may help researchers compare and reconcile the institutional change and social delivery efforts of social enterprises. Such an approach helps forge a productive conversation about social change and is less prone to deepen ideological divides.

Continuing Research on Social Enterprises as Disciplined Exploration

The data generated by our exploration demonstrates clearly that social enterprises do not operate in an institutional vacuum. Societal, economic, and political aspects of the environment in which they operate matter for how they function, which legal form they adopt, which problems they address, and their potential to create impact. The aim of this chapter is to advance the study of social enterprises: to provide room for imaginative theorizing based on disciplined exploration and to foster dialogue across disciplinary lines. As with the ambition of Humboldt and Bonpland in their study of plants, the objective here is to embrace the diversity inherent in the phenomena under review—social enterprises, in this case—as a starting point to detect patterns (Verflechtungen) and possible features of a global archetype. Going forward, I see two foci of exploration that present especially promising opportunities to advance this agenda.

First, future research can investigate in more detail the relationship between legal form, problem domain, and institutional context. The outer form matters for organizations (Weber [1922] 1978), just as it does for plants (Humboldt and Bonpland 1807). For example, an examination of how legal forms are used offers an analytical framework for assessing how institutional context affects social enterprises; for revisiting the relationship between social enterprises, the market, and the state; and for generating new insights on how problem domains are governed (Seibel 2015). Using data from our study, we analyzed the likelihood that two social enterprises will adopt the same legal form if they operate in the same country and in the same problem domain. The results of that analysis, as shown in Figure 14.8, reveal the level of homogeneity in the choice of legal form across countries and problem domains.9

In the United Kingdom, social enterprise legal forms are fairly heterogeneous across problem domains, as indicated by the low likelihood that any two social enterprises in a domain will choose the same legal form from the range of options identified in Figure 14.1 (for-profit, nonprofit, dual, cooperative, and community interest company). In other countries, we identified important intracountry differences. In Portugal, for example, social enterprises in health are likely to assume the same legal form as their peer social enterprises, whereas social enterprises in housing and development vary more widely in their choice of legal form. Our data reveals dominant governing patterns in specific problem domains; in Hungary almost all social enterprises in education and research share the same legal form, and a similar pattern applies in Romania to social enterprises in health and (to a slightly lesser degree) to social enterprises in social services. How problem domains are governed differs across countries, and that difference affects the choice of legal form in ways that reflect a variety of factors, including historical legacies, the salience of a problem domain in society, political debates and party politics, and the perceived and actual magnitude of the underlying problem. Future research can probe these factors in greater detail and thereby put the study of social enterprises in active dialogue with prominent work on classifying social welfare regimes and different varieties of capitalism. The data shown in this chapter is cross-sectional, but the analysis offered here can inform future longitudinal studies that place social enterprises in the context of how societies, welfare regimes, and systems of economic order—along with their respective institutional arrangements—evolve over time (Anheier and Krlev 2014; Deeg and Jackson 2007).

Second, future research can continue the search for features that social enterprises hold in common in order to identify a global “social enterprise” archetype. Our dataset is limited to nine countries; it does not cover the United States or any other country in the Americas, nor does it cover any developing countries. However, the analysis presented in this chapter reveals a number of features that characterize social enterprises across geographies. Along with a focus on social mission and the practice of revenue generation through commercial activity, our study identified the measurement of social performance and collaboration in the pursuit of public purpose as defining characteristics. Complementing the study of the outer (legal) form of social enterprises with research on internal organizational features will help identify the features of a global archetype and examine variations of that archetype more explicitly.

Table 1 Patterns of collaboration by social enterprises across countries

Sample sizes: China: N=102, Germany: N=107, Hungary: N=122, Portugal: N=111, Romania: N=109, Russia: N=104, Spain: N=125, Sweden: N=106, UK: N=135

Table 2 Distribution of problem domains for social enterprises across countries

Sample sizes: China: N=102, Germany: N=107, Hungary: N=122, Portugal: N=111, Romania: N=109, Russia: N=104, Spain: N=125, Sweden: N=106, UK: N=135

Table 3 Distribution of primary beneficiaries of social enterprises across countries

Sample sizes: China: N=102, Germany: N=107, Hungary: N=122, Portugal: N=111, Romania: N=109, Russia: N=104, Spain: N=125, Sweden: N=106, UK: N=135

Humboldt and Bonpland distinguish between species of plants that grow only in certain geographies and “social species” that grow in multiple habitats. Similarly, future studies examining the repertoire of organizational features of social enterprises may detect different species of social enterprises. Research in this area will also help uncover how such species, or particular features of a species, travel across different contexts or take root only in specific contexts. Finally, combining an analysis of organizational features with a systematic analysis of problem domains and country contexts will allow for a disciplined exploration of novelty and unconventionality in the study of social enterprises. Opportunities for the empirical and theoretical study of social enterprises are numerous. The greatest potential may lie less in developing a grand theory of social enterprise than in pursuing disciplined exploration that thoroughly deploys the tools we have at hand.

Note

* This chapter builds on a large-scale research project—SEFORÏS—that has benefited from financial support provided by the European Union through the Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development, and demonstration under grant agreement 613500. I would like to thank my fellow travelers on the SEFORïS journey, especially Marieke Huysentruyt, Ute Stephan, and Tomislav Rimac. Nikolas Rathert helped explore the data presented in this chapter and has provided valuable insights. Woody Powell reminded me of the beauty and richness in Alexander von Humboldt’s work. Patricia Bromley, Magali Delmas, and other participants in the workshop that led to this volume provided very helpful comments.