281Chapter 11

The Evolution of American Paleopathology

Della Collins Cook and Mary Lucas Powell

In Memoriam: Patricia S. Bridges; Sit tibi terra levis

I. INTRODUCTION

Paleopathology, the study of disease in past populations, lies at the intersection of several disciplines, among them, paleontology, medicine, dentistry, and anthropology. Perhaps because it is so interdisciplinary, it has resisted professionalization until recently. Much of that professionalization has occurred in North America.

Sir Marc Armand Ruffer, a British physician known today primarily for his extensive and innovative research on Egyptian mummies, is widely credited with the invention of the term “palaeopathology.” However, this term was actually coined by an American physician and ornithologist, R. W. Shufeldt, in an article titled “Notes on Palaeopathology” that appeared in 1892 in the journal Popular Science Monthly. He wrote: “Palaeopathology: (Greek palaios, ancient, and pathos, a suffering), the word used in the title of this paper, is a term here proposed under which may be described all diseases or pathological conditions found fossilized in the remains of extinct or fossil animals” (1892:679). Shufeldt’s choice of the word pathos explicitly links this area of inquiry to the specialized study of pathology in current medical science. The term appeared in the 1895 edition of Funk and Wagnall’s Standard Dictionary and was popularized by Ruffer in his 1921 treatise, Studies in Palaeopathology of Egypt, but it 282was not included in the Oxford English Dictionary until 1985 with the expanded definition, “the study of pathological conditions found in ancient human and animal remains” (Cockburn, 1997, in Elerick and Tyson, 1997; Aufderheide and Rodriguez-Martin, 1998).

The evolution of paleopathology from a minor interest of Renaissance antiquarians and pastime of Victorian physicians to a modern scientific discipline in the 20th century has been reviewed in detail by a number of scholars, beginning with the American anatomist Roy L. Moodie (1880–1934). Moodie’s “Studies in Paleopathology. I. A General Consideration of the Evidences of Pathological Conditions Found among Fossil Animals” was published in Annals of Medical History (1917). His Paleopathology: An Introduction to the Study of Ancient Evidences of Disease, the first comprehensive review, soon followed in 1923, and a popular summary, The Antiquity of Disease, was published the same year. This slim book, published in the University of Chicago Science Series and aimed at “the educated layman,” devoted more than half its pages to evidence for disease in fossils, because Moodie’s purpose was to challenge Henry Fairfield Osborn’s thesis that disease was an important factor in extinction. His discussion of human paleopathology is concerned with trepanation and other evidence for “primitive surgery” as much as with evidence for disease. A more anthropological focus is found in the work of Herbert Upham Williams (1866–1938), who was a physician and professor of pathology at University of Buffalo. His lengthy review article titled “Human Paleopathology” in Archives of Pathology (1929) focused exclusively on examination and interpretation of human remains, a departure from the older, more comparative approach defined by Shufeldt.

In 1965, Saul Jarcho organized an international symposium titled Human Palaeopathology, supported by the National Academy of Sciences/National Research Council. The papers had a strongly Americanist focus. New studies were presented on skeletal remains from Mesa Verde in New Mexico and a Middle Horizon site in California, and there was critical reassessment of earlier work in the Southwest, the Arctic, and Peru. In addition to anthropologists, the participants included a virtual who’s who of bone biology at midcentury, Walter Putschar, Henry Jaffe, Lent Johnson, and Harold Frost among them. Innovations in radiology and histology, as well as the need for greater sophistication in diagnosis, were stressed by several contributors. The symposium papers were published the following year (Jarcho, 1966b).

This volume is particularly notable for Jarcho’s essay The Development and Present Condition of Human Palaeopathology in the United States. He presented brief biographies of the heroes of what he regarded as the Golden Age: John Collins Warren, Samuel George Morton, Joseph Jones, Jeffries Wyman, Frederic Putnam and William Whitney, Aleš Hrdlička, Marc Armand Ruffer, Roy L. Moodie, Herbert U. Williams, and Earnest A. Hooton. He situated them in an account of the institutional origins of our field in Boston and Washington. 283Jarcho called for “a revival of palaeopathology in the United States that should counteract the doldrums of the last three decades” (1966b:28), emphasizing the discovery of cranial deformation and syphilis among the ancient inhabitants of North America as questions that motivated these pioneers. Jarcho was critical of the relative isolation of paleopathology from medical sciences and of its marginal position in archaeology. He stressed the potential for innovations in method and the need for systematic data collection. He was particularly critical of publication practices in American paleopathology, pointing out that pathology journals did not recognize it as a specialty and that archaeological publications were slow, secondary, and lacking indices. He stressed the need for cross-disciplinary bibliography. In 2006, we can report that the “Renaissance and Revolution” (1966b:27) that Jarcho called for have come to pass.

However, the renaissance or revival had already begun when Jarcho wrote his essay. The first evidence of renewed life was a review essay by Erwin H. Ackerknecht (1953) included in the influential graduate text book Anthropology Today. In the 1960s, several book-length overviews of paleopathology were published by European scholars eminent in the field: Calvin Wells’ (1964a) Bones, Bodies, and Disease (1964), Ackerknecht’s (1965) History and Geography of the Most Important Diseases, and Paul A. Janssens’ (1970) Palaeopathology: Diseases and Injuries of Prehistoric Man. These authors were generally optimistic about the future of the discipline and encouraged collaborations with medically trained scholars. A substantial edited volume, Don R. Brothwell and A. T. Sandison’s (1967), Diseases in Antiquity, collected together what are now the classic studies in the field. Some researchers, however, expressed fears that paleopathology would become excessively self-referential, and some, such as Jarcho, lamented the lack of theoretical and methodological advances over the previous three decades.

The revival of paleopathology addressed a wide scientific public. Articles published by American paleopathologists during this period in Science, the first by Saul Jarcho (1965b), the second by J. Lawrence Angel on paleodemography and anemia in the Mediterranean (1966b), a third by Ellis Kerley and William Bass (1967) on the history of the discipline, and a fourth by George Armelagos (1969) on studies of health and disease in ancient Nubia, brought modern paleopathology to the attention of the larger scientific community and emphasized the necessity for interdisciplinary collaborations.

One sign of vigorous development in a scientific discipline is the steady proliferation of literature published by scholars all over the world. By that measure, paleopathology enjoyed a booming economy during the latter half of the 20th century. In 1971, George J. Armelagos and colleagues published the first comprehensive Bibliography of Human Paleopathology, which included 1778 individual international contributions. In the same year, Jay B. Crain published a substantially complementary bibliographic list of 1222 sources 284(Crain, 1971). In 1980, Michael R. Zimmerman raised the ante regarding quality with a carefully abstracted and indexed bibliography of 628 sources (Zimmerman, 1980). The work he began continues to grow through the contributions of many of our colleagues to the annotated bibliography section of the Paleopathology Newsletter. Most recently, in 1997, the San Diego Museum of Man issued a massive volume titled Human Paleopathology and Related Subjects, An International Bibliography, edited by Elerick and Tyson, which includes more than 18,000 individual entries. Six supplements to this reference work, compiled by a vast array of international scholars working in concert with the original editors, are now available in electronic form, with more additions planned in the future. Jarcho (1966b) identified systematic bibliography comparable to the Index Medicus as a critical need for our discipline. We have not yet achieved that level, but great strides have been made.

The more recent evolution of paleopathology in the United States has been addressed in three review articles, which appeared almost simultaneously in the early 1980s: “Palaeopathology: An American Account” by Jane E. Buikstra and Della C. Cook (1980) in Annual Review of Anthropology, “History and Development of Paleopathology,” by J. Lawrence Angel (1981b) in the jubilee issue of American Journal of Physical Anthropology, and “The Development of American Paleopathology,” by Douglas H. Ubelaker (1982), in Frank Spencer’s edited volume, A History of American Physical Anthropology, 1930–1980. These authors noted a new focus in the decade following Jarcho’s essay on detailed differential diagnosis (based on carefully constructed models of disease processes) and on explicit integration of biocultural context, dietary reconstruction, analyses of growth and development, and paleodemographical analysis into interpretations of skeletal pathology. Because the early history of American paleopathology has already been discussed in considerable detail in these reviews, we begin with a brief review of the first century and a half and then focus our attention primarily on major theoretical and methodological developments of the last quarter of the 20th century.

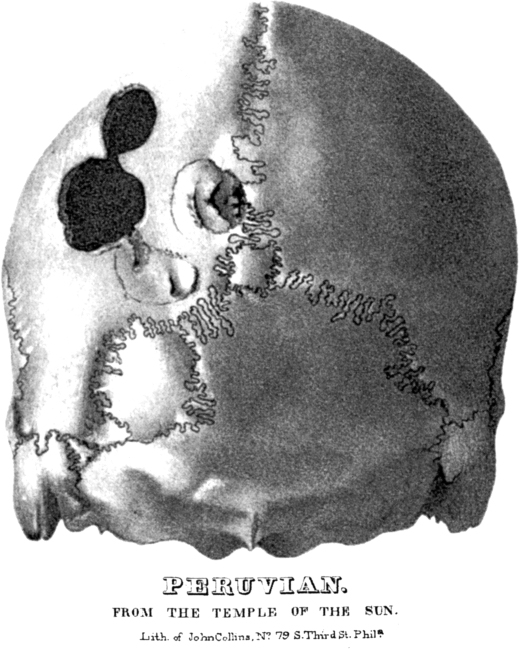

II. DEFORMED CRANIA AND ANCIENT SYPHILIS: THE BEGINNINGS OF AMERICAN PALEOPATHOLOGY

The discovery of intentionally modified crania in burials ranging from Egypt to Chile attracted the attention of North American anatomists and physicians such as John Collins Warren (1822, 1838) and Samuel George Morton (1839, 1844b). Their interest lay primarily in human cranial morphology rather than paleopathology per se, but they built large collections that remain useful to the 285present day. Their treatises (Warren, 1822; Morton, 1839) present deformed crania as extreme examples (albeit deliberately produced) of metrical and morphological variability, and their omission of other pathology has been noted (Ubelaker, 1982). Jarcho (1966b) correctly points out that Morton illustrated cranial lesions without noting them in his text and suggests that Morton’s interest in paleopathology was minimal. However, Samuel Morton’s enormous output includes several gems of paleopathology apart from his interest in cranial deformation. For example, he debunked claims for an extinct pygmy race in North America, pointing out that its proponents had mistaken the skeletons of children for very short adults (1841), and he described anomalies and pathologies ranging from atlanto-occipital fusion (1847), to bullet (1839:167) and axe wounds (Morton, 1839:131) (Fig. 1), the latter perhaps associated with unrecognized trepanation.

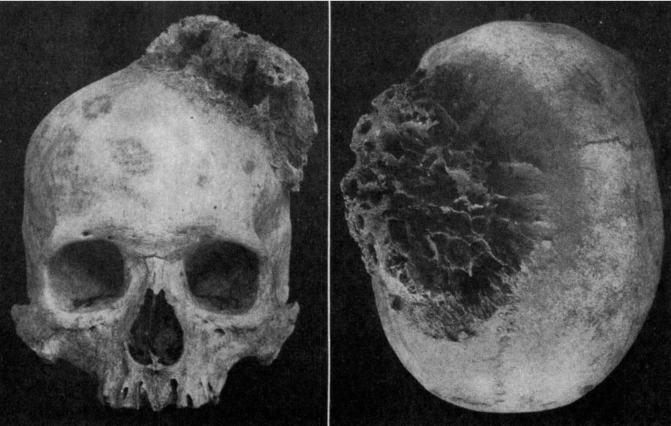

Figure 1 Axe wounds in a Peruvian skull (Morton, 1839).

286The generation that followed Morton remained chiefly concerned with skeletal morphology and anthropometry, primarily of the skull, aimed at documentation of worldwide human variation. In the words of Ubelaker (1982:341), “to some extent, disease processes and cultural modifications presented unwanted ‘noise’ in the system” because they distorted the “pure” biological evidence of population affinities. We will touch on several exceptions to this largely accurate generalization.

Jeffries Wyman (1814–1874), a physician who served as first curator of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University, was Warren’s student and successor. His work focused primarily on descriptions of normal and artificially modified cranial morphology in archaeological specimens from Oceania, the Pacific Coast of South America, and the southeastern United States (1866, 1871, 1874, 1875), but he supplemented his craniology with extensive notes on anomalies and pathologies. Ubelaker (1982) points out that Wyman’s comparative study of “auditory nodules” in prehistoric Peruvian and Polynesian crania (1868) was the first American study to take an explicitly comparative population approach to understanding lesions in ancient populations. Wyman’s work foreshadowed Hrdlička’s (1935b) monograph on auditory exostosis by nearly 70 years. Wyman’s brief contribution to the Museum’s fourth annual report (1871) compares 18 crania from his excavations in Florida to crania from Kentucky and Peru, touching on deformation, cranial capacity and variations, but the most interesting observations for our purposes concern the postcranial skeleton. Flattening of the tibia is discussed with reference to Gillman’s observations in Michigan Indians and Broca’s studies of Cro-Magnon. Septal aperture and pelvic diameters are also explored, and there is a brief discussion of pathological changes that includes what may be the first report of spondylolysis. Jarcho notes that “lesions that we might class as presumably syphilitic are described clearly and concisely but are attributed merely to ‘periosteal inflammations’” (Jarcho, 1966b: 11, citing Wyman, 1875), thereby initiating the controversy that has occupied much of the attention of American paleopathologists to the present day. Wyman’s (1874) last report is a brief but lurid account of evidence of cannibalism from his Florida excavations that might be revisited in the light of today’s controversies about taphonomy and human remains.

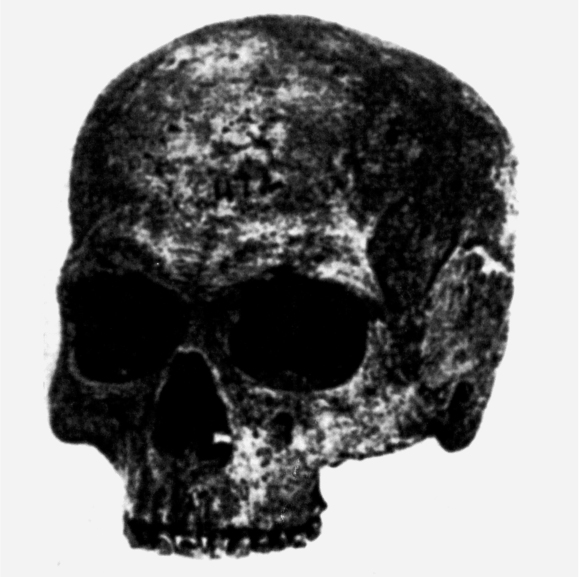

The first treatise that focused primarily on skeletal evidence of disease in ancient North America was Joseph Jones’ detailed examinations of pathology in Late Prehistoric stone box burials in the Nashville Basin of Tennessee (1876). In his Explorations of the Aboriginal Remains of Tennessee, Jones sounded a second theme that dominated American paleopathology throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries: the antiquity of syphilis. Jones (1833–1896), a physician who had served as a medical officer in the Confederate Army during the recent Civil War, was the son of the pioneering southern archaeologist, 287Charles Colcock Jones (Schnell, 1999). At the time of his Tennessee studies, Joseph Jones held the position of professor of chemistry and clinical medicine in the medical department of the University of Louisiana in New Orleans. In his paleopathological diagnoses, he drew extensively upon his own biological training and clinical experience for his diagnosis of “syphilis” and employed both macroscopic and histological examination of lesions (Fig. 2). He applied chemistry—hydrochloric acid digestion—to the question of the antiquity of the Tennessee remains, concluding that they were so old that contact with the Spanish could not account for the disease. Ten of 171 pages in Jones’ monograph are devoted to the syphilis question. The remainder is largely devoted to archaeological context. However, mortuary practices, cranial deformation, fading of hair color in mummies, misinterpretation of children’s skeletons as pygmies, and cranial capacity are explored at length. Jones might be credited as the first scholar to focus on weeding out pseudopathology. Jones cites both Morton and Wyman, as well as several European sources. Two years later he described similar lesions in shell mound remains from Louisiana and reviewed historical accounts of disease among American Indians (Jones, 1878). Jones’ careful approach to diagnosing past diseases by reference to current medical knowledge provided a powerful model for the subsequent theoretical and methodological development of American paleopathology, as well as an informed examination of one of its enduring themes.

Figure 2 Syphilitic cranium from Big Harpeth River (Jones, 1876; Williams, 1932).

288Harrison Allen (1841–1897) was a physician and professor of physiology, zoology, and anatomy at the University of Pennsylvania. His contributions to paleopathology begin in 1867 with his detailed description of the Moulin Quignon jaw. He compared the French fossil with 300 mandibles from Samuel Morton’s collection in order to rebut claims that it was morphologically distinct from modern humans, describing the effects of tooth loss in the process (Allen, 1867). He also produced one of the first careful case studies, a diagnosis of cleft palate versus trauma in a Seminole cranium from Morton’s collection (Allen, 1898), unfortunately not figured in his publication and clearly not one of the three Seminole crania described by Morton in Crania Americana (1839). Allen’s two monographs on collections from excavations, Crania from the St. John’s River, Florida (1895) and The Study of Skulls from the Hawaiian Islands (1898), are descriptive craniologies in the mainstream of the typological anthropology of the late 19th century. However, both include detailed studies of discrete traits, reflecting Allen’s deep interest in functional and comparative anatomy of the skull, and in the borderland between normal and pathological variation. An example is the discussion of the relationship of metopism to interorbital distance, citing Lombroso’s criminal typology, in the Florida monograph (Allen, 1895a). This aspect of Allen’s work is discussed at length by Hrdlička (1918).

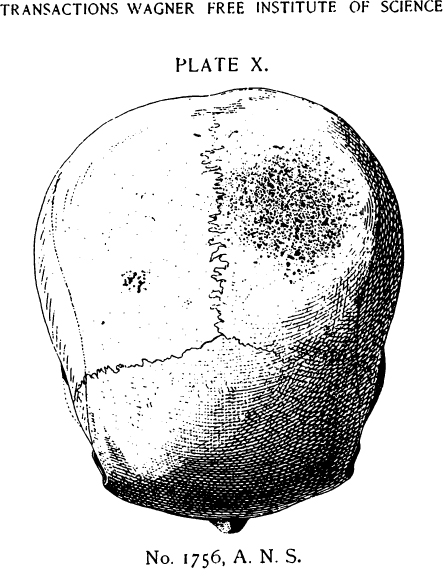

Allen’s (1898) study of Hawaiian crania is quite modern in its comparison of noble with commoner and pre-contact with post-contact specimens. Allen thus precedes Hooton in pioneering the comparative approach by more than 30 years, although his comparisons are less quantitative than Hooton’s. Osteoporosis, osteitis attributed to syphilis, hyperostosis of the mandibular condyle, and alveolar atrophy following mortuary ablation of the anterior teeth are described. His most interesting diagnosis attributes vault and nasal lesions, enamel hypoplasia, and small maxillae in a 13-year-old to measles (1898; see Fig. 3). Ubelaker (1982) notes that both Harrison Allen and Joseph Jones studied with Joseph Leidy (1823–1891) at the University of Pennsylvania. Leidy had been a student of Samuel Morton’s, and while Leidy made no contributions to paleopathology himself, he was an innovative contributor to paleontology, pathology, particularly to parasitology (Warren, 1998). Allen and Jones thus belong to an academic genealogy of Philadelphia physicians beginning with Morton.

Two physical anthropologists in the Department of Anthropology at the National Museum of Natural History, the successor to the United States National Museum in the Smithsonian Institution, were strongly influenced by Hrdlička’s interests in skeletal pathology. The International Bibliography on Human Paleopathology and Related Subjects (Elerick and Tyson, 1997) lists 85 single-authored and 9 coauthored publications by T. Dale Stewart and 108 single-authored and 15 coauthored publications by J. Lawrence Angel. Stewart published numerous studies of the effects of diet and cultural practices on skeletal and dental structures (e.g., Stewart, 1931a, 1939a, 1941a,b, 1942; Stewart and Groome, 1968), the history of premodern surgery (1937b, 1958b), forensic anthropology (1948, 1951b, 1954c, 1962d, 1979a), skeletal pathology (1931b, 1935, 1956a,b, 1966, 1974), and Native American populations of the New World (1960a, 1970b, 1973b, 1979b, n.d.).

289

Figure 3 Hawaiian child with dental and facial lesions of measles (Allen, 1898).

290The Harvard genealogy was even more prolific. William F. Whitney (1850–1921), a physician who served as curator of the Warren Anatomical Museum at Harvard University, contributed two articles to our literature, the first a short essay adding to the literature on pre-Columbian syphilis (1883) and the second (1886) a lengthy discussion of evidence for diseases of bone in ancient Indian remains in the collections of the Royal College of Surgeons in London, the Société d’Anthropologie in Paris, the Army Medical Museum in Washington, the Peabody Museum, and the Warren Anatomical Museum. In the latter paper Whitney discusses, among many topics, the association between Wormian bones and cranial deformation, the high prevalence of auditory exostoses, and specific lesions diagnosed as healed trauma, syphilis, and tuberculosis. He notes the rarity of several conditions, e.g., osteoporotic fracture: “it is remarkable that no case of impacted fracture of the neck of the femur has been found, which is of such frequent occurrence in old people” (Whitney, 1886:440). In all, he discusses 176 cases by catalogue number and includes skeletal material from Arkansas, California, Colorado, Kentucky, Iowa, Ohio, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Vancouver, Quebec, and Mexico. Writing of Whitney’s relationship to F. W. Putnam, Jarcho infers that “paleopathology was now a separate and almost segregated area of research” (Jarcho, 1966b: 12), but it is an equally reasonable inference that Putnam, who lacked an advanced degree, deferred to physicians, including Whitney and Dr. Frank W. Langdon (1881), in the study of ancient diseases.

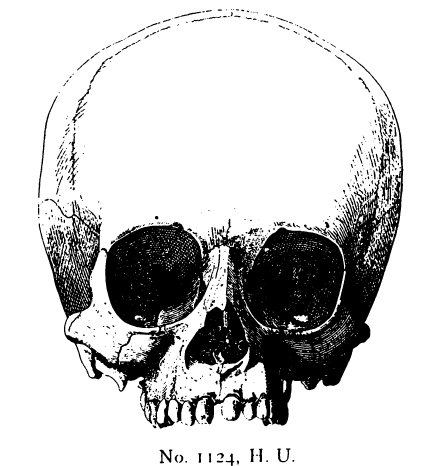

Dentistry professionalized independently of medicine in the United States with its own associations and journals. This isolation is reflected in relatively limited attention from historians and bibliographers of medicine, including those interested in paleopathology. The earliest American paper of which we are aware is a notice of remains from excavations by the Kansas City Academy of Science in Clay County, Missouri, that remarks on heavy dental wear without caries: “as the enamel of the crowns of the teeth of the Mound-Builders was absent for the greater portion of their lives, and yet the teeth remained sound, it follows that when a portion of the enamel is removed decay of the rest of the tooth does not necessarily follow” (Sozinskey, 1878:498). Dental science retained this open attitude toward drawing such general inferences from paleopathology. At the end of the 19th century, Robert R. Andrews (1893) described crania with filed and inlayed teeth from Labna in Yucatan (Fig. 4) and Copan in Honduras, noting heavy calculus deposits and a stone implant, and marveling at the skill of the ancient practitioners. Andrews’ paper reports on material recovered for the Peabody Museum’s Hemenway Expedition. It appears in an issue of The Dental Practitioner and Advertiser that celebrates the association’s meeting in conjunction with the World Columbian Congress in Chicago that year. This case was published again 2 years later in Dental Cosmos amidst a survey of ancient teeth in museum collections in the United States; the author also presents data from his own excavations at Cahokia (Patrick, 1895).

291

Figure 4 Dental filing in a skull from Labna, Yucatan (Andrews, 1893).

292III. THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY

The early 20th century roots of American paleopathology were well established in disciplines other than anthropology, as Jarcho has shown (1966b). Roy L. Moodie (1884–1934) was professor of anatomy at University of Illinois at Chicago and later at the College of Dentistry of the University of Southern California. He had studied under the University of Chicago paleontologist Samuel Wendell Williston (1851–1918). By far the largest part of Moodie’s work in paleopathology concerns fossil animals, and many of his ideas, e.g., his interpretation of hyperextension of the spine as evidence for tetanus, are now the province of taphonomy rather than paleopathology. Chicago became the locus of an active community of paleopathologists in the first decades of the 20th century. In addition to his review publications (Moodie, 1917, 1923a,b), Moodie conducted an extensive radiographic study of North American, Egyptian, and Peruvian mummies in the collections of the Field Museum of Natural History, presenting the results in a remarkably detailed atlas (Moodie, 1931). Another Chicago physician encouraged by Williston was Charles A. Parker, who described osteoarthritis in the knees of Lansing Man (1904). Henri Stearnes Denninger (b. 1904), a physician affiliated with the Fay-Cooper Cole’s Illinois archaeological survey during his student years at Illinois Medical School, published a series of careful case studies of Illinois and southwestern remains (Denninger, 1931, 1933, 1935, 1938; Cook, 1980b; see Fig. 5). H. U. Williams’ (1932, 1936) magisterial papers on the origins of syphilis include specimens and information sent to him by both Moodie and Denninger.

Other noteworthy paleontologists who found paleopathology relevant to their research include Franz Weidenreich (1873–1948), an Alsatian who spent the last years of his career at the American Museum of Natural History (Weidenreich, 1939), and William L. Straus (1900–1981), an anatomist at Johns Hopkins University (Straus and Cave, 1957). Both explored the utility of pathological changes in making behavioral inferences about early humans.

Herbert U. Williams (1866–1938), a physician, was professor of bacteriology and pathology at the University of Buffalo. Jarcho (1966b) points out his innovative use of radiology, microscopy, and serology in study of ancient bone. Williams set out to review the literature, but added new critical and analytical material throughout his review. His careful study of porotic hyperostosis is a classic in its use of sections and radiographic correlation (1929). His principal contribution to paleopathology is his extensive review of Old and New World evidence regarding the origins of syphilis (1932, 1936). These papers are noteworthy for their rigorous examination of both documentary and skeletal evidence, and for their novel arguments for paleoepidemiology: “Where the seeds of corn could be carried, the seeds of syphilis might also be carried. What now takes place in a few days may have required centuries, but one is dealing with centuries” (Williams, 1932:980). Williams reexamined an enormous quantity of skeletal material ranging from that reported by Jones (see Fig. 2) and Whitney to that published early in the century by the Peruvian physician and archaeologist Julio C. Tello (1880–1947). Tello wrote a controversial monograph, his dissertation, on cranial and ceramic evidence for syphilis, to which Williams lent his stature (Tello, 1909; Tello and Williams, 1930; Stewart, 1943c). Williams was active in the Buffalo Museum of Science and contributed collections and articles on fossil fishes and local archaeology (Goodyear, 1994). An accomplished amateur musician, he wrote the University’s surprisingly Darwinian fight song, The Bison Is King!

293

Figure 5 Denninger’s hemimelia case from Fulton County, Illinois (1931).

294Several archaeologists were early contributors to paleopathology. Perhaps the most prominent was George Grant MacCurdy (1863–1947), who was a curator and professor at Yale University. He is best remembered for his extensive excavation and collecting in Peru with Bingham at Machu Picchu, as well as elsewhere in the Americas. He was one of the founding members of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists. His publications concern trepanation and other surgical procedures as well as a wide range of pathologies in Peruvian skeletal material (1905, 1918, 1923). The cranial osteosarcoma from Paucarcancha, Peru, that has served in several publications as an icon of ancient disease is from MacCurdy’s work (1923: see Fig. 6).

Figure 6 Cranial osteosarcoma from Paucarcancha, Peru (MacCurdy, 1923).

295Dental paleopathology continued its somewhat separate history. Jarcho points out that Moodie’s later career led him to dental paleopathology and to an interest in testing the then-current focal infection theory linking dental disease with arthritis (Jarcho, 1966b; Moodie, 1928). One of Moodie’s papers on this subject appeared in a health magazine for the general public (1930). However, the true pioneer in this field was Rufus Wood Leigh (1884–1964). Leigh was a D.D.S. who also earned an M.A. in anthropology. Long associated with the Army Medical Museum, he taught at Georgetown University and later at the University of Utah. His systematic studies of caries and dental wear in prehistoric Native Americans and in ancient Egyptians explored the effects of way of life on oral health (1925a,b, 1928, 1929, 1930, 1934, 1937). The first of these papers compared Indian Knoll, Sioux, Arikara, and Havikuh Zuni collections at the Smithsonian. Leigh believed the Indian Knoll collection to be maize farmers—Ritchie’s concept of Archaic was still in the future—but found this group to have the most severe attrition and Sioux the least (1925a). He notes in this study and his later study of Peruvian crania (1937) that caries were common in these ancient peoples, but that the age of onset was much later than in modern Americans, a quite modern epidemiological insight. Leigh’s parallel publications in anthropological and dental journals reflect a commitment to the value of each discipline for the other, and they are still widely cited. The dentist Samuel Rabkin’s studies of several sites in Northern Alabama (1942) and Indian Knoll (1943) are similar in scope. In the later 20th century Albert A. Dahlberg (1908–1993), professor of dentistry and anthropology at the University of Chicago, continued this emphasis on the common ground between his disciplines (1960; Mann and Murphy, 1990).

Physical anthropology developed as a profession under the strong influence of the Czech-American physician Aleš Hrdlička (1869–1943), who was curator of the Division of Physical Anthropology of the United States National Museum, Smithsonian Institution, founder of the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, and energetic collector of skeletons. As Ubelaker points out, paleopathology was secondary to his major focus on racial typology and the antiquity of human occupation in the Americas. Much of his paleopathology concerns cultural practices that alter the morphology of the skeleton, an interest that, along with his interest in anomalies, can be seen as “a direct outgrowth of his career interest in documenting human variation” (1982:340). In 1913, Hrdlička traveled to Peru to collect specimens of skeletal pathology and surgical treatment from a broad range of Native American archaeological sites for the purpose of developing an exhibit on physical anthropology for the Panama–California Exposition to be held in San Diego in 1915. This collection, comprising more than 1000 pathological specimens, is now curated at the San Diego Museum of Man. A photographic catalogue with descriptions by Charles F. Merbs places the collection in modern scientific context (Tyson and Alcauskas, 1980). His equally vigorous efforts for the U.S. National Museum to collect large, documented skeletal series continue 296to provide samples for generations of researchers, albeit shaped by Hrdlička’s theories of the peopling of the New World (Hunt, 2002; Keenleyside, 1998, 2003; Keenleyside and Mann, 1991).

Hrdlička published numerous studies of prehistoric Native American skeletal pathology, many of them dealing with cultural modifications of the teeth and skull (Ubelaker, 1982; Elerick and Tyson, 1997). His studies on trepanation in Mexico (1897) and Peru (1914b, 1939b), on Arctic tooth ablation (1940b), and on ethnomedicine (Hrdlička, 1932; Lumholtz and Hrdlička, 1897) are among his many contributions to paleopathology that remain important to modern anthropologists. He contributed the term symmetrical hyperostosis to the lively international discussion of skeletal signs of anemia (1914b) and documented the extensive variability in the frequency of auditory exostosis among Native Americans (1935b). His early papers on congenital anomalies in ancient skeletons (1899a, 1933) are thoroughly articulated with the medical literature of his day. The earliest of these, a description of a Mexican skeleton with cervical ribs, a bicipital rib, low mandibular condyles, and numerous features he calls “anthropoid” (1899a: 103), is interesting in its weighing of individual versus “ethnic” features. Hrdlička’s ideas about the antiquity of humans in the New World had not yet crystallized; he cites Morton’s work as science rather than history, and he is open to the notion of important ethnic differentiation. Among his last publications is a detailed description of a tiny skull from Peru, which he attributes to a “midget … without … any detectable pathological condition” (1943b:81), citing just his own work on normal variation. Ortner (2003) has revised this diagnosis to congenital idiocy, finding evidence for hypoplasia of the frontal lobes. It is remarkable that a physician who began his career working in an insane asylum could construe this skull as normal.

Hrdlička’s larger concerns color his paleopathology in other ways. On the one hand, Hrdlička’s view of infectious disease is closely tied to his view of the profound isolation of New World populations from the Old World and its diseases. An early interest in, or open-mindedness toward, the diagnosis of syphilis (1908b) and tuberculosis (1911) gave way to a radical vision of a New World Eden. Late in life he argued for the absence of infectious pathogens, except for infant diarrhea and pneumonia, in the pre-Columbian Americas (1932). On the other hand, his view of Indian health is grounded in his early experience in health surveys of reservation populations, socially conscious studies that linked infectious diseases to human misery (1908c, 1909a).

In 1930, the classicist convert to physical anthropology Earnest Albert Hooton (1887–1954) of Harvard University produced the first comprehensive study of a specific pre-contact Native American population, The Indians of Pecos Pueblo (see Chapter 4). Hooton took a surprisingly modern approach in this analysis: he not only collected the usual craniometric and morphological data but also systematically recorded pathological lesions and carefully evaluated 297them within the Pecos cultural, behavioral, and temporal contexts. Thanks to the careful archaeological excavation and analysis of this large site, which had been occupied for several centuries, Hooton was able to divide the large series of burials into temporally distinct subsamples. This degree of chronological control, which permitted detailed diachronic comparisons of specific skeletal features, represented a significant advance over earlier analyses that often barely distinguished pre-Columbian from post-Columbian contexts. Hooton satisfied established anthropological expectations by publishing detailed metrical and morphological analyses of the Pecos Pueblo crania (with some postcranial data included), but he also investigated associations between patterns of diet, food preparation, and habitual activities (farming, hunting, warfare, etc.) and patterns of observed skeletal pathology. He tabulated frequency data on specific conditions, including osteoarthritis, trauma, inflammatory lesions, and porotic hyperostosis (which he called “osteoporosis symmetrica”), suggested that syphilis had been present at the site, and evaluated health for the different time periods. Hooton recruited six physicians to collaborate in the analysis of the Pecos Pueblo remains, the most prominent among them being Herbert U. Williams. Ubelaker (1982) calls Hooton’s approach epidemiological. Hooton’s student J. Lawrence Angel (1981b:510) credits Hooton with ending the early 20th-century eclipse of paleopathology through “his insistent stress on the population as a unit of study,” and Ackerknecht (1953) viewed Hooton’s concept of integration as the essential step in making paleopathology meaningful within anthropology.

Despite the integration of relevant biological and cultural data apparent in Hooton’s landmark analysis, more than three decades would pass before the widespread adoption of his approach. A large number of prehistoric Native American skeletal series were excavated by various New Deal archaeological projects funded by federal and state relief agencies during the later 1930s and early 1940s. (See Chapter 6.) Some of these series, such as those from Indian Knoll and other sites in Kentucky and Moundville in central Alabama, both analyzed by Hooton’s student, Charles E. Snow (1941a,b, 1942, 1943, 1945a,b, 1948, 1951; see Fig. 7), included several hundred well-preserved individuals and would have been ideal material for diachronic and comparative studies that built upon Hooton’s foundation. However, the physical anthropologists, including Snow, Marshall Newman (Snow and Newman, 1942; Newman, 1951), Ivar Skarland (1939), and Fred S. Hulse (1941), who analyzed these and other series for the New Deal archaeological reports, were primarily concerned with traditional typological analysis for the purpose of delineating biological relationships between Native American populations throughout North America, particularly in the eastern United States. The reporting of skeletal and dental pathology is typically nonsystematic, even anecdotal, although the diagnosis of specific infectious diseases (particularly syphilis) was often attempted and associations among diet, food processing technology (e.g., the grinding stones characteristic of the Archaic period sites), and dental pathology were noted (see Rabkin, 1942, 1943). Nevertheless, Charles E. Snow (1910–1967) did produce fine case studies of scalping (1941b) and achondroplasia (1943) at Moundville that continue to be cited.

298

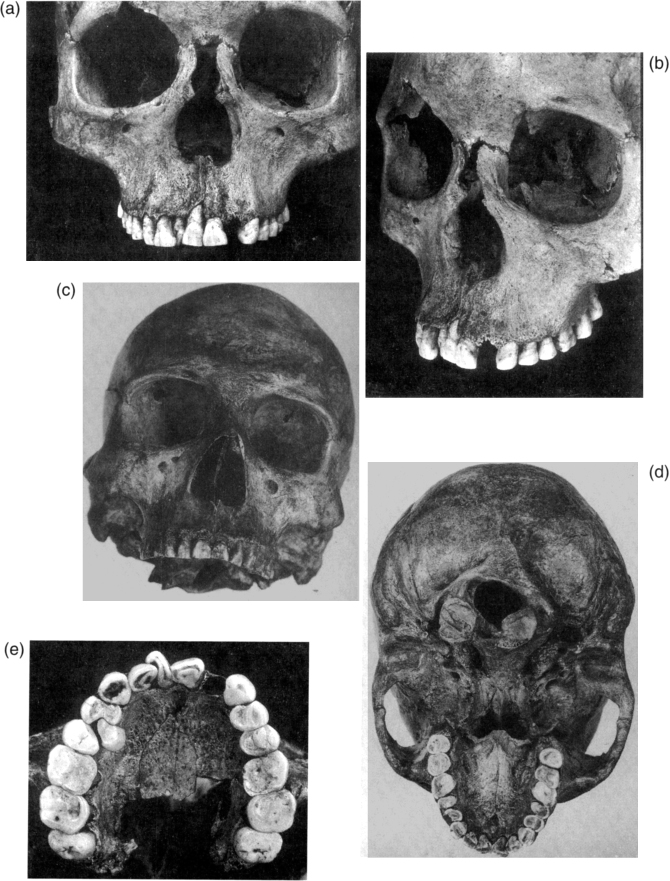

Figure 7 Photographs of skeletal pathology from the Indian Knoll site, taken by Charles Snow. (a and b) Adult female (Burial 9), Indian Knoll, remodeled nasal aperture. Reproduced from Snow (1948) with permission of the William S. Webb Museum of Anthropology (WSWMA), University of Kentucky, Lexington. (c and d) Adult male (Burial 105), Indian Knoll, atlanto-occipital fusion and facial asymmetry. (e) Adult female (Burial 349), Indian Knoll, with severe anterior malocclusion. Previously unpublished photographs curated at WSWMA, used by permission.

299The focus on typological anthropometry was continued in the published analyses of skeletal series excavated under the auspices of numerous River Basin Surveys and other federally funded archaeological projects over the next two decades. An important exception to this generalization is the work of Alice Brues, who was Hooton’s student. While her descriptions of skeletal remains include typological analysis of crania, she devoted equal attention to evidence of disease, and her reports are excellent examples of careful diagnosis (Brues, 1946b,c, 1957, 1958b, 1959a).

IV. LATER 20TH CENTURY

Two physical anthropologists in the Department of Anthropology at the National Museum of Natural History, the successor to the United States National Museum in the Smithsonian Institution, were strongly influenced by Hrdlička’s interests in skeletal pathology. T. Dale Stewart (1901–1997) was trained as a physician, although he had begun work at the Smithsonian before beginning his medical studies at Johns Hopkins. During his long and productive career he published on the effects of diet on skeletal and dental structures (e.g., Stewart, 1931a, 1963b), ancient surgery (1937b, 1943c, 1958b), skeletal pathology (1931b, 1935, 1943c, 1956a,b, 1966, 1974; Mann et al., 1990), and Native American populations of the New World (1960a, 1963a,b, 1970b, 1973b, 1979b). His studies on cranial and dental deformation constitute a large proportion of the important work on these topics (1939a, 1941a,b, 1942, 1943c, 1963a; Stewart and Groome, 1968). Stewart’s interests in population differences in arthritis patterning (1947), spondylolysis (1931b, 1935, 1956a), and neural tube defects (1975) have been particularly influential on recent research in paleopathology. Many of Stewart’s papers correct errors in the literature of paleopathology (1937b, 1966, 1969, 1975, 1976).

J. Lawrence Angel (1915–1986) studied with E. A. Hooton at Harvard, earning his Ph.D. in anthropology in 1942. His career included fieldwork in WPA projects and teaching at Jefferson Medical College, in addition to his position at the NMNH. He focused his attentions on patterns of health and disease in the ancient eastern Mediterranean and their causal relationships with temporal change in diet, activity patterns, population affinities and migrations, and demography (Angel, 1966b, 1971, 1972, 1973b,c, 1974a, 1978, 1979, 1982, 1984; Angel and Bisel, 1985). While his earliest papers are largely typological in 300focus, they include brief discussions of pathology, touching on subjects as diverse as trepanation (1943), ankylosing spondylitis (1946b), and sex differences in frequencies of skull wounds (1943). Many of his papers contain stimulating insights not amenable to testing in the small and disparate samples available for study. An example is The Cultural Ecology of General versus Dental Health (1974a), a paper exploring the association of longevity, subsistence, and caries and abscesses. These ideas recur through his work; they harken back to Moodie’s interests and have stimulated more recent scholarship with more powerful methods (Meiklejohn et al., 1992). Angel’s central focus in paleopathology was surely his effort at teasing apart malaria and thalassemia as contributors to anemia in Mediterranean remains, as well as distinguishing them from health consequences of agriculture and urban life (1966b, 1969, 1971, 1972, 1973b,c, 1978), a problem that remains unsolved. These questions led him to attempt to infer fecundity from changes in the pubic symphysis (1969), a project that, albeit mistaken, has stimulated much useful research.

During the last decade of his life, Angel became interested in the analysis of biological and cultural determinants of health and mortality among free and enslaved African-Americans in the Middle Atlantic region of the United States (Angel, 1981a; Angel et al., 1987). Angel shared with his mentor Hooton a focus on the effects of technology and diet on skeletal morphology (Angel, 1943, 1946b, 1973b, 1982; see Ackerknecht, 1953). An innovative feature of Angel’s work was his lifelong interest in activity-related modifications of the skeleton. He coined the term “atl-atl elbow” to describe patterned arthritis in California foragers (Angel, 1966a) and contributed extensively to the literature on activity markers (Kennedy, 1989). The breadth of his interests is strongly emphasized in the chapters of A Life in Science: Papers in Honor of J. Lawrence Angel (Buikstra, 1990).

The internist, medical historian, and editor Saul Jarcho (1906–2000) was a close associate of T. Dale Stewart’s. In addition to the review publications discussed earlier, he produced a series of elegant case studies (Jarcho et al., 1963, 1965; Jarcho, 1964, 1965a) that serve as models for curing the malaise he identified in midcentury paleopathology. Among them, his use of bone chemistry to demonstrate lead poisoning in Pueblo potters (1964) is a landmark in joining laboratory sciences, archaeology, and physical anthropology. Another influential medical historian was Erwin H. Ackerknecht (1906–1988). His 1953 review argued that “the pathology of a society reflects its general conditions and growth and offers, therefore, valuable clues to an understanding of the total society” (1953:120), an inclusive view consistent with his desire to integrate the study of medicine with social anthropology. Like Jarcho, Ackerknecht was an M.D., but, fleeing Germany for political reasons in 1933, he studied ethnology under the French anthropologist Paul Rivet and later jointed the Boasian community at the American Museum of Natural History. He was professor of history of medicine 301at Wisconsin and Zurich. His sojourn in the United States (1941–1957) generated important studies of ethnomedicine that should be read by anyone interested in ancient surgery (Ackerknecht, 1971).

Several archaeologists made important contributions to paleopathology in the mid-20th century. William A. Ritchie (1903–1995) was curator at the New York State Museum and is best known for defining the Archaic period in eastern North America. His excavation reports include observations of pathologies, and he authored excellent case studies of tuberculosis and multiple myeloma (Ritchie and Warren, 1932; Ritchie, 1952). Kenneth E. Kidd (1906–1994), who was curator of ethnology at the Royal Ontario Museum and professor at Trent University, contributed case studies of ankylosing spondylitis and torticollis (1954).

In Canada, James E. Anderson (b. 1926) performed much the same role as Stewart and Angel in the United States. Anderson was a student of the anatomist J. C. Boileau Grant (1886–1973) and taught anatomy and anthropology at University of Toronto, SUNY Buffalo, and McMaster University (Jerkic, 2001). He was particularly interested in development, variability, and the borderlands of pathology (Anderson, 1960). His contributions to paleopathology include diagnosing treponematosis in some of the earliest remains from the Western Hemisphere (1965) and extraction of meaningful information about ancient disease from ossuary materials (1964). In Chile, Juan Munizaga (1934–1996), who trained with T. D. Stewart, was an institution builder and important contributor to paleopathology (Aspillaga, 1996; Munizaga, 1965, 1991; Munizaga et al., 1978a,b). In Mexico, Juan Comas (1900–1979) was similarly a pioneer in paleopathology. Comas was a Mallorcan who had studied with the Swiss physical anthropologist Eugène Pittard (Spencer, 1997c). His Americanist interests included population-appropriate age, sex, and stature standards, cranial deformation, and cranial anomalies (1942a,b, 1943, 1965, 1976). Both Comas and Munizaga were interested in the history of anthropology (Munizaga, 1993; Comas, 1968). Luis Fernando Ferreira similarly pioneered a remarkable program in paleoparasitology at Fundação Oswaldo Cruz in Brazil (Ferreira et al., 1980, 1984; Araújo et al., 1980, 2003).

In the 1960s and early 1970s, paleopathological analyses, which harkened back to Hooton’s population approach, increased dramatically. These studies explicitly integrated archaeological, ethnographic, and historical data with detailed observations of skeletal pathology to explain differences in demography and skeletal evidence of changes in nutrition, trauma, infectious disease, iron deficiency anemia, and dental health in temporally sequential population samples in ancient Sudanese Nubia by George J. Armelagos (1968) and, in the New World, prehistoric Virginia by Lucille E. Hoyme and William M. Bass (1962), Illinois by Armelagos’ students John W. Lallo (1973) and Jerome C. Rose (1973), and Kentucky by Claire M. Cassidy (1972). These studies shared 302(not by accident) several important theoretical and methodological features: they emphasized the necessity of the population approach, focusing on population samples rather than unrelated “interesting” specimens in order to obtain a valid demographic “cross section” of the populations in question; they examined a broad range of skeletal and dental indicators of health; they employed methods of analysis borrowed from other disciplines, such as radiography (a long tradition in paleopathology); and they all tested the proposition long held by historians and anthropologists that the change from nomadic hunting–gathering to horticulture- or agriculture-based sedentism invariably improved “the quality of life” of human populations as reflected in patterns of growth, development, nutrition, workload, infectious disease experience, and longevity. Finally, they all concluded that increasing reliance upon cereal-based agriculture (maize in the New World, millet in ancient Nubia) was at best a mixed blessing. The earliest of them (Hoyme and Bass, 1962) was conducted as part of a federally funded dam construction project in Virginia, but the other four were doctoral dissertation projects in the Departments of Anthropology at (respectively) the University of Colorado, the University of Massachusetts, and the University of Wisconsin.

These multifaceted investigations interpreted biological data within appropriate cultural contexts for the explicit purpose of shedding light on a theoretical issue of growing importance within American archaeology: the myth of the “unmixed blessings” of the Neolithic revolution (i.e., plant and animal domestication and the rise of sedentary village life). They heralded an era of interaction between paleopathology and mainstream American archaeology, which was just entering the first stage of its own revolution: the “New Archaeology”, explicitly scientific and eager to question all previously received wisdom about the human past. In hindsight, that interaction has been more unidirectional than one would like. These studies and the large literature that followed them are relatively little cited among archaeologists, a problem that is not helped by our colleagues’ persistence in characterizing Late Woodland farmers in the Midwest as hunter–gatherers (Goodman and Armelagos, 1985).

However, the human cost of agriculture was not the only question that motivated the late 20th-century renaissance in paleopathology. A strong focus on cultural context animated new work on activity-related pathology in the Arctic by Charles F. Merbs (1969, 1983) and the Southwest (Jurmain, 1975, 1977a). By the 1970s, programmatic research integrating paleopathology as a means of understanding ancient ways of life became the rule rather than the exception for several anthropologists whose regional interests have led them to a broad focus on disease conditions. The work of Marvin Allison and colleagues in Chile (Allison, 1973, 1974a,b,c, 1979; Elzay et al., 1977; Munizaga et al., 1978a,b) and Frank and Julie Saul in Mesoamerica (Saul, 1972, 1976; Saul and Saul, 1991) are excellent examples.

303V. AMERICAN PALEOPATHOLOGY AT THE END OF THE 20TH CENTURY

The last three decades have seen a welcome proliferation of interdisciplinary projects involving archaeologists, biological anthropologists (including paleopathologists), historians, ethnographers, and other scholars aimed at broad-scale reconstructions of specific lifeways in the past. As Jane E. Buikstra predicted in the title of her chapter in the 1991 volume, What Mean These Bones? Studies in Southeastern Archaeology (Powell, Bridges, and Mires, editors), paleopathology had finally come “Out of the Appendix and Into the Dirt,” i.e., become an active partner in the formulation of research objectives in such projects from the initial planning stages onward.

The longest running of these collaborations is surely William M. Bass’ career-long focus on understanding the culture history and adaptations of Plains Indians. Bill Bass was Snow’s student at the University of Kentucky, completing a craniological master’s thesis on the Moundville series in 1956. His subsequent career at the University of Kansas and University of Tennessee is grounded in his participation in the River Basin Survey excavations on the Plains in cooperation with many archaeologists, historians, and other specialists, notably Waldo Wedel and Donald J. Lehmer. Many of his contributions to paleopathology reflect a long and fruitful collaboration with the physician and professor of otolaryngology, John B. Gregg, who had begun to apply his specialty to paleopathology in the 1960s (Holzhueter et al., 1965; Gregg et al., 1965, 1982; Bass et al., 1974). Among Bass’ numerous students, Douglas Ubelaker, Douglas Owsley, David Hunt, Ted Rathbun, and Richard Jantz have been important contributors to paleopathology, and they continue to recruit colleagues from other disciplines (e.g., Logan et al., 2003). A summary account of his influence can be gleaned from a volume dedicated to Bass, Skeletal Biology in the Great Plains (Owsley and Jantz, 1994).

Another outstanding example of such interdisciplinary cooperation is the La Florida bioarchaeological project, coordinated by biological anthropologist Clark S. Larsen and archaeologist David Hurst Thomas over the past two decades. Larsen’s investigation of diachronic changes in health, disease, mortality, and osteological markers of habitual activity patterns in Native American populations of the northern portion of La Florida (the Georgia Coast) began with his dissertation research in the late 1970s at the University of Michigan (ironically, in a graduate program that offered no systematic training in paleopathology). After completion of the dissertation in 1980, he expanded his research to include several Spanish colonial period sites on coastal islands or the adjacent mainland in the region (Larsen, 1982, 1990). So far, two generations of students in bioarchaeology, history, ethnology, and archaeology from four institutions (including Northern Illinois University, University of 304North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and Ohio State) have been actively involved under Larsen’s tutelage with La Florida investigations covering some 3000 years of Native American life in the extreme southeastern United States. Larsen’s latest book, titled Bioarchaeology of Spanish Florida: The Impact of Colonialism (2001), summarizes this landmark project. Larsen and several of his long-time colleagues on the Georgia Bight project have also applied their multidisciplinary approach in a collaborative salvage project with archaeologist Robert L. Kelly (Larsen and Kelly, 1995) to examine dimensions of health, disease, and skeletal morphology among hunter-gatherers of the Great Basin in the western United States.

VI. TEXTS AND PROFESSIONALIZATION

The last quarter of the 20th century was inaugurated nationally in 1976 by celebrations of America’s bicentennial and in paleopathological circles by the publication of R. Ted Steinbock’s Paleopathological Diagnosis and Interpretation (1976), based on his dissertation in medicine and anthropology at Harvard and written specifically to guide paleopathologists in performing differential diagnosis of specific diseases. It opens with a discussion of bone as a biological organ system, emphasizing that pathological skeletal morphology can only be recognized and interpreted by reference to normal patterns of growth and development. Subsequent chapters focus on specific categories of disease affecting bone: trauma, hematological disorders, metabolic bone disease, arthritis, and tumors, and selected specific (treponematosis, tuberculosis, leprosy) and nonspecific (pyogenic osteomyelitis) infections. Steinbock emphasized the importance of detailed comparisons between firmly contextualized archaeological specimens and medical examples from both modern and preantibiotic-era medical collections.

This landmark text was soon joined by Donald J. Ortner and Walter G. J. Putschar’s Identification of Pathological Conditions in Human Skeletal Remains (1981; see also Ortner, 2003), which greatly expanded the range of conditions discussed by Steinbock and featured almost 800 photographic illustrations of pathological specimens from medical and museum collections around the world. Some publications adopted the atlas format: the Atlas of Human Paleopathology, by Michael R. Zimmerman and Marc A. Kelley (1982), and the Regional Atlas of Bone Disease, by Robert W. Mann and Sean P. Murphy (1990). Others were explicitly comprehensive in nature, such as The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Paleopathology, by Arthur C. Aufderheide and Conrado Rodriguez-Martin (1998), an excellent companion volume to The Cambridge World History of Human Disease (Kiple, 1993) published 5 years earlier. Some texts from this period were devoted to the analysis of naturally or artificially desiccated bodies, 305such as Aidan and Eve Cockburn’s (1980) edited volume, Mummies, Disease, and Ancient Cultures, which was expanded in a second edition (Cockburn et al., 1998). New noninvasive (CAT scanning and MRI) and minimally invasive (endoscopy) methods developed for use in clinical medicine now not only reveal more detailed information than the older styles of autopsies, popular since the late 19th century, but are far more acceptable to museum curators concerned about the destruction of valuable specimens.

Other recent advances in American paleopathology include molecular investigations of ancient microbial DNA and metabolites of earlier forms of infectious diseases (e.g., tuberculosis in the pre-contact Americas), significant critical réévaluations of long-accepted methods of interpretation of skeletal evidence of morbidity, the incorporation of a broader range of relevant disease models considered in epidemiological perspective (e.g., nonvenereal forms of treponemal disease as well as venereal syphilis), the growth of scholarly societies aimed at promoting the professionalization of the discipline and strengthening international collaborations, isotopic evaluations of dietary regimens that contribute to multifocal studies of noninfectious diseases (e.g., acquired iron-deficiency anemia), and a new pedagogical emphasis upon intensive study of normal biological processes which shape bone as well as the abnormal processes that deform it.

VII. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AND INTERPRETATION IN EPIDEMIOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE

In his three-part review of paleopathology, H. U. Williams devoted 92 pages to syphilis and just 62 pages to everything else (Williams, 1929, 1932, 1936). While we have done our part to maintain this imbalance (Cook, 1980b; Powell, 1992, 2000; Powell and Cook, 2005; Jacobi et al., 1992), our colleagues have rectified it to a large extent in the last two decades. A number of interesting infectious diseases are now visible to paleopathologists, among them smallpox (Jackes, 1983), coccidioidomycosis (Harrison et al., 1991), Chagas’ disease (Guhl et al., 1999; Reinhard et al., 2003; Aufderheide et al., 2004), and perhaps Lyme disease (Lewis, 1998). The interior zoo of ancient intestinal and parasites has been enlarged greatly (Araújo et al., 2003), and there is renewed interest in external parasites (Reinhard and Buikstra, 2003). Our field has tended to view one of the most ubiquitous of infectious diseases — streptococccal infection in the form of dental caries — as unimportant because it is a trivial condition in our age of readily available antibiotics. Osteomyelitis secondary to caries has been discussed by Ortner (2003:197), and dental caries has been evaluated carefully 306as a heath hazard in several recent studies (Sciulli and Schneider, 1986; Sledzik and Moore-Jansen, 1991; Saunders et al., 1997). Philip Walker has ventured into pathology among the living to explore social status and caries (Walker and Hewlett, 1990), and status differences in caries rates have been demonstrated in some ancient populations (Cucina and Tiesler, 2003).

The variety and sophistication of diagnoses of arthritis, orthopedic, and degenerative diseases has increased as well. Instructive case studies of inflammatory arthritis (Ortner and Utermohle, 1981), juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (Buikstra and Poznanski et al., 1990; Lewis, 1998), DISH (Crubezy and Trinkhaus, 1992), and Scheuermann’s disease (Merbs, 1983; Cook et al., 1983) have appeared in recent years. Claims about the evolutionary history of rheumatoid arthritis in the Americas (Rothschild et al., 1988) remain to be substantiated with careful presentation of evidence. Nevertheless, it is still true that these conditions remain understudied in American paleopathology (Bridges, 1992).

Age-related bone loss is a topic for which paleopathology offers perplexing, and perhaps useful, comparative perspectives to medical science. Several studies have noted the scarcity of osteoporosis-related or fragility fractures in most ancient populations. It has been suggested that few people survived to advanced ages (Lovejoy and Heipel, 1981) or that activity and diet promoted better bone maintenance in the past (Agarwal and Grynpas, 1996). The claim that osteoporotic fracture is absent in the past (Agarwal and Grynpas, 1996) reflects quite stringent criteria and an incomplete reading of the literature in paleopathology in that vertebral compression fractures are seen among older people in some groups (Merbs, 1983:116; Cybulski, 1992). A recent symposium volume explores these complexities in detail (Agarwal and Stout, 2003). Other degenerative diseases have received relatively little attention, but conditions as diverse as Morgagni syndrome (Armelagos and Chrisman, 1988) and atherosclerosis (Cybulski, 1992; Zimmerman and Trinkaus et al., 1981) are now represented in paleopathology.

In contrast, there has been a remarkable growth in interest in congenital defects and genetic syndromes in the last two decades. There is now a comprehensive atlas of anomalies of the axial skeleton illustrated largely with material from ancient North America (Barnes, 1994a); a companion volume on the appendicular skeleton would be highly desirable. Some landmark new discoveries include severe neural tube defects (Dickel and Doran, 1989), congenital scoliosis (Cybulski, 1992), probable Apert syndrome with hydrocephalus (Pedersen and Anton, 1998), Rubenstein–Taybi syndrome (Wilbur, 2000), and a variety of anomalies of the extremities (Cybulski, 1988; Barnes, 1994b; Keeleyside and Mann, 1991; Murphy, 1999). More extensive studies of aural atresia (Hodges et al., 1990) and Klippel–Feil syndrome (Merbs and Euler, 1985; Danforth et al., 1994) revisit topics explored by Hrdlička and Jarcho and raise interesting issues about relatively high frequency of these conditions among certain Native 307American isolates. Genetic syndromes expressed in the teeth have a smaller literature than their diversity and ease of recognition in skeletal material might suggest (Cook, 1980a; Mann et al., 1990), but the discovery of ancient anomalies with little or no visibility in the clinical literature holds out promise of interaction between fields (Skinner and Hung, 1989; Lukacs, 1991). It is a measure of the potential of the paleopathology of congenital defects for useful application in medical research that our colleagues in clinical medicine seek out our ancient case studies (e.g., Berg, 2003).

VIII. TUBERCULOSIS: A FERTILE FIELD FOR MOLECULAR PALEOPATHOLOGY

Late 20th-century paleopathology overturned the received wisdom of the midcentury regarding the absence of tuberculosis in the New World, and it is perhaps difficult to recall how controversial the discoveries made by Ritchie (1952), Allison et al. (1973), and others (Buikstra, 1981c) once were. Recent advances in molecular analysis of ancient amplified DNA and other organic materials have provided independent verification of previous pathological diagnoses of tuberculosis in human remains from New and Old World archaeological sites. Refined methods of DNA “fingerprinting” had been used successfully to identify index cases in modern localized outbreaks of antibiotic-resistant tuberculosis, by comparing different strains of related pathogens, and protocols for the recovery of DNA from ancient human tissues had been standardized. Comparisons of ancient mycobacterial DNA recovered from skeletal individuals from archaeological sites in Peru (Salo et al., 1994), Germany (Baron et al., 1996), England (Roberts and Dixon, 1993; Taylor et al., 1996), Hungary (Haas et al., 2000), Scotland, Turkey (Spigelman and Lemma, 1993), Illinois, Canada (Braun et al., 1998), and Egypt (Zink and Nerlich, 2003) with DNA “profiles” of members of the modern Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (principally M. tuberculosis and M. bovis, the two species that infect mammalian hosts most commonly) suggest that tuberculosis has an exceedingly ancient “pedigree” as a human disease.

The majority of these molecular studies have focused on a 123-bp segment of DNA unique to the M. tuberculosis complex, known as IS6110 (Salo et al., 1994). At the 1997 International Congress on The Evolution and Palaeoepidemiology of Tuberculosis in Szeged, Hungary (Pálfi et al., 1999), discussions of mycobacterial DNA and RNA were featured in 17 of the 86 papers presented, a rate of almost 20%. Nine papers presented molecular aspects of modern mycobacteria in the United States, Guadeloupe, France, Hungary, Slovakia, and Austria. Eight other presentations summarized analyses of ancient mycobacterial DNA 308in human remains from Egypt, the Middle East, Borneo, Moravia, Lithuania, the midwestern and southwestern United States, Ontario, Peru, and Chile.

Another new molecular technique is based on the detection of mycolic acids produced by pathogenic mycobacteria inside infected human hosts. This has been applied successfully to bone samples from identified tuberculous patients in a historic hospital cemetery (Newcastle Infirmary) as well as to samples from pathological and nonpathological skeletons from two archaeological sites in England (Gernaey et al., 1999). These fatty acids in the cell walls of the mycobacteria can be readily detected by liquid chromatography (Ramos, 1994), and this method has been employed for some time in clinical settings for the verification of M. tuberculosis complex infection in living patients. Because mycolic acids may be found in tissues distant from the site of frank tuberculous lesions in ill individuals and are also detectable in individuals who have been exposed to the pathogenic mycobacteria but had not developed symptoms of clinical disease, the exciting application of this clinical technique to archaeological specimens opens the way for investigations of true prevalence of prehistoric tuberculosis, i.e., the proportion of infected to uninfected individuals in a skeletal sample rather than the mere identification of those few individuals who developed recognizable bone lesions before death. Because modern tuberculosis affects bone in fewer than 10% of clinically ill patients (Schlossberg, 1994), lesions identifiable by paleopathological criteria represent merely “the tip of the tip of the iceberg” of tuberculous infection in past populations. A critical review of the current state of paleopathological research on tuberculosis is presented in Roberts and Buikstra’s (2003) comprehensive volume, Tuberculosis: Old Disease, New Awakening.

This new technology has spurred a revival of comparative paleopathology, a relatively dormant field since Moodie’s time. M. tuberculosis complex DNA has been recovered from the skeleton of a historic Neutral Indian dog from Ontario that showed hypertrophic osteoarthropathy, a characteristic lesion of end-stage tuberculosis in that species (Bathurst and Barta, 2004). Positive spoligotyping results from a Pleistocene bison with less characteristic lesions have also been reported (Rothschild et al., 2001). This intriguing finding awaits confirmation with other samples of comparable antiquity.

IX. SYPHILIS: A BROADER VIEW OF DIAGNOSTIC ALTERNATIVES

While the emphasis placed by Wood et al. (1992) on interindividual differences in host immune response and developmental integrity in determining the form and degree of biological response to pathological insults is both apposite and timely, another quite different “osteological paradox” also deserves careful 309consideration. Differences in pathogenicity and synergistic interactions among species and strains of pathogenic organisms also play key roles in determining patterns of skeletal response to infection seen in skeletal series (Powell, 2000). American paleopathology at the end of the 20th century incorporates an increasingly sophisticated range of diagnostic models both for identification of specific ancient infectious diseases and for evaluation of the burden of morbidity and mortality upon their human hosts. Not all infectious diseases, even those variant forms caused by closely related pathogens, exact the same toll on human populations either individually or in the aggregate effect. A disease such as tuberculosis, identified in numerous pre-Columbian Native American skeletal populations and of particular interest to many American paleopathologists, may be nearly invisible in dry bone examinations of skeletal series, simply because most infected individuals follow one of three common trajectories: (a) they never develop clinical disease, (b) they recover with latent infection maintained for decades, or (c) they die before bone involvement develops. Only a few follow a fourth pathway: (d) the development of diagnostic bone lesions. As a result, mortality from this disease potentially far outstrips skeletal morbidity, but just the reverse is true for treponematosis, another major infectious disease frequently identified at pre-Columbian sites. While venereal syphilis had a high potential for severely impacting mortality at all ages (including prenatal life), two of its three modern “cousins” (yaws and endemic syphilis, but not pinta) can produce high population levels of skeletal morbidity but only very rarely cause death. These two diseases are in effect “mirror images” of one another in their capacities for morbid and mortal impact and, when present simultaneously in an individual or a population, may each exacerbate the effects of the other.

Arguments pro and contra the pre-Columbian New World presence of another major infectious disease, venereal syphilis, have been debated for some five centuries, beginning soon after the dramatic “outbreak” of this apparently new disease in 1493 in southern Europe following the so-called siege of Naples. At the first International Congress on the Evolution and Paleoepidemiology of Infectious Diseases (ICEPID), held in Toulon, France, in 1993 (Dutour et al., 1994), this question was reexamined by a broad range of scholars employing the most current evidence from historical, medical, archaeological, and paleopathological research conducted on a large number of New and Old World population samples. No clear consensus was reached on the origin(s) of venereal treponemal disease, but the pre-Columbian presence of some form(s) of treponemal disease is (at the present time) more clearly apparent in the American bioarchaeological record than in its European counterpart. Molecular investigations of treponemal disease have lagged behind similar studies of ancient tuberculosis, but the first successful identification of prehistoric treponemal antibody in a pre-Columbian Native American skeleton from Virginia (Ortner et al., 1992) will surely stimulate further research in this area. It seems possible that the introduction of New World 310treponematosis, fundamentally endemic in its native form and acquired through variable means from Native American contacts (Powell, 1994), into the quite different epidemiological context of late 15th-century European populations may have resulted in a venereally spread outbreak of a “new” disease. Furthermore, if Old World forms of treponematosis were indeed as rare in western European populations as they appear in the bioarchaeological record, perhaps because they had been very recently introduced from tropical Africa or the Near East, it is possible that these populations’ immunological vulnerability may have contributed to the savage virulence of the new disease as reported in contemporary medical accounts of the first decades of its appearance (Quetel, 1990).

A comprehensive review of the current state of research on treponematosis is presented in Powell and Cook (2005).

X. DEVELOPMENTAL STRESS MARKERS AND THE “OSTEOLOGICAL PARADOX”: CRITICAL REEVALUATIONS OF ACCEPTED INTERPRETATIONS

During the last quarter of the 20th century, advancements in theoretical and methodological aspects of analyzing a broad range of physiological “stress markers” have led to increasingly sophisticated interpretations of the relative contributions of poor diets, widespread infectious disease, heavy workloads, and significant parasite infestations to patterns of health and disease, particularly for subadults. Diets deficient in essential nutrients and/or calories fail to provide strong resistance to opportunistic infectious diseases (e.g., tuberculosis) and promote multiple specific signs of biological stress, including reduced adult tooth and body size, fluctuating asymmetry of dental and skeletal epigenetic traits and metric features, dental enamel defects, decreased neural canal diameter and cranial base height, increased risk of spina bifida, altered pelvic inlet shape, and markers of specific metabolic malfunction such as iron deficiency, anemia, rickets, and scurvy (Angel et al., 1987; Cook, 1979, 1981; Buikstra and Cook, 1980; Clark, 1988; Clark et al., 1986; Goodman and Armelagos, 1989; Huss-Ashmore et al., 1982; Cohen and Armelagos, 1984; Larsen, 1987, 1997; Stewart-Macadam and Kent, 1992; Ortner et al., 2001). Because diet plays such an important role in the development of many forms of pathology, American paleopathologists have long been interested in efficient methodologies for biochemical analysis of bone and dental tissue samples aimed at paleodietary reconstruction (Buikstra, 1992; Larsen, 1997; Sobilik, 1994). During the 1970s, paleonutrition emerged as a specialty increasingly independent of paleopathology, initially focusing on trace elements, but moving in the early 1980s to 311stable isotopes of specific elements (primarily carbon and nitrogen; Price, 1989; Sandford, 1993; White, 1999). Interpretation of pathological change in bone can now be augmented by independent investigations into diet at the individual and population levels.

These advances have prompted a series of critical reevaluations of current paradigms for the evaluation of levels of health in past human populations. In an article in Current Anthropology titled “The Osteological Paradox: Problems of Inferring Prehistoric Health from Skeletal Samples” (Wood et al., 1992), the authors challenged conventional assumptions concerning morbidity (i.e., that high frequencies of observed skeletal lesions, interpreted without reference to specific etiologies or age-at-death distributions, could directly reflect low levels of population health) and mortality (i.e., that low mean age-at-death invariably signaled demographic decline), by positing significant “intervening variables”: demographic nonstationarity and selective mortality due to intrapopulation heterogeneity in risk of death (“individual frailty”). Drawing upon clinical and epidemiological reviews of associations between morbidity and age, sex, social status, and other contextual variables, they argue that changing patterns of skeletal pathology and mortality reported worldwide for population samples undergoing the transition from hunting/gathering lifeways to reliance on cereal-based agriculture could arguably be interpreted as reflecting either improved or worsened levels of health if widely used criteria (e.g., skeletal inflammatory response) were employed without reference to demographic contexts.

A point that is equally important in such evaluations, although not addressed by Wood and colleagues (1992), is critical consideration of the different potentials for skeletal morbidity and for mortality associated with different infectious diseases. For example, tuberculosis produces recognizable skeletal pathology in relatively few of its victims yet carries a very high risk of death, while the endemic treponematoses (yaws and nonvenereal syphilis) produce some degree of skeletal pathology during the advanced stages of illness in a relatively high proportion (20–50%) of infected individuals, yet carry a negligible direct risk of death because they do not affect internal organ systems as does venereal syphilis (Powell, 1992). Overemphasis by researchers on isolated aspects of undifferentiated nonspecific skeletal pathology, e.g., periostitis on tibia shafts, without simultaneous consideration of other, more useful indicators of specific etiologies, as well as careful analysis of the mortality profile of the sample in question, can result in erroneous conclusions as to the major risks of early death in that population.

A second important réévaluation challenged the biological reality of “penalty-free adaptation” to suboptimal diets and living conditions, as set forth in the “small but healthy” hypothesis formulated by Seckler (1980, 1982). Seckler argued that “smallness may not be associated with functional impairments … the mild to moderately malnourished people in the deprivation theory are simply 312‘small but healthy’ people in the homeostatis theory” (emphasis in original, Seckler, 1982:129). Goodman (1994) disagreed, citing numerous recent studies of living populations by researchers in biomedicine, epidemiology, nutrition, and political economy that link poor nutrition with small adult stature and a host of pathological conditions, including decreased energy expenditure, reduced cognitive skills, and premature mortality, as well as the biological markers of poor development of skeletal and dental tissues familiar to paleopathologists. For example, minor reductions in adult tooth size, apparently harmless in themselves, are correlated positively in many archaeological populations with another seemingly harmless developmental defect, linear enamel hypoplasia; the important point is that both are correlated positively with shortened life span (Simpson et al., 1990). As Larsen notes in his review of the role of stress markers in bioarchaeological investigations, “clearly, there are negative consequences of small body size in disadvantaged settings, indicating that this reduction is maladaptive” (Larsen, 1997:62). Goodman and colleagues have joined forces with other proactive anthropologists who study the biological impact of political economies in modern disadvantaged populations (Crooks, 1995; Leatherman and Goodman, 1997; Stinson, 1992) to decry what they see as “Cartesian reductionism and vulgar adaptationism” (the title of his 1994 paper) in the benign interpretation of malignant consequences of politically determined inequalities of essential resources. A particularly satisfying application of this thinking is a meta-analysis of data from the American Southwest that includes social status, density, and ecological factors; substantial evidence for cultural buffering of crises emerges from this effort (Nelson et al., 1994). A recent review puts these issues in a context stressing political complexity and gender as important variables in archaeological studies (Danforth, 1999).