417Chapter 16

A View from Afar: Bioarchaeology in Britain

Charlotte A. Roberts

I. INTRODUCTION

The United States has, to date, overshadowed the U.K. in the study of osteology and palaeopathology due to its deep grounding in anthropology … but we are catching up slowly. (Roberts, 2003:107)

The study of human remains from archaeological sites has a long history in Europe, as it has in North America. However, some parts of Europe have seen more rapid development than others. In Britain it is only fairly recently (since the mid-1980s) where we have seen a significant change in the quantity and quality of data produced from skeletal analysis, data that have been used from a bioarchaeological perspective. It is noticeable, but not surprising, that Europe as a whole (but particularly Britain) has lagged behind in the development of a biocultural/bioarchaeological approach to using skeletal data to contribute to our understanding of past human populations. First, this is probably because most work, until recently, had been undertaken by people working in other disciplines such as anatomy, dentistry, and medicine who had little background knowledge of archaeology to allow them to contextualize their biological data. Second, until the 1980s, there was no specific training for people wishing to work in the field of (palaeo) physical anthropology/bioarchaeology (i.e., archaeologically derived human remains and not early hominid remains), at both undergraduate and graduate levels, nor were there many people employed as (palaeo) physical anthropologists to teach in departments of archaeology, certainly in Britain. Key to this problem has been the emphasis on archaeology departments in universities rather than anthropology departments, as seen in North America. 418The long-standing four-field approach taken in anthropology in North America (incorporating linguistics, cultural anthropology, physical/biological anthropology, and archaeology) has allowed the development of a truly integrated bioarchaeological approach to the study of past humans, and the production of graduates with a broad all-encompassing knowledge.

This chapter compares and contrasts the study of the bioarchaeology of past human populations (utilizing their skeletal remains) in North America and Britain, highlighting the major similarities and differences. Where relevant, examples from the rest of Europe are used to emphasize particular points. The chapter starts with a commentary on the use of terms in Britain to describe the study of human remains, follows with a brief history of development of study in Europe, focuses on the contribution of British people to bioarchaeology (recognizing that some non-British people have contributed and continue to do so), highlights recent impacts on the progress of the discipline, and makes predictions for the future.

II. DEFINITIONS

The study of skeletal remains from archaeological sites (the most common type of human remains most [palaeo] physical anthropologists deal with) in North America has been termed physical anthropology, biological anthropology, and more recently bioarchaeology. While all these terms have been used in Britain, at some time and in parallel with North America, there are many more that practitioners have decided are/were more appropriate at certain points. These include human skeletal biologist, osteologist, palaeopathologist, and osteoarchaeologist. Of interest here is the term “bioarchaeologist” used in Britain where it describes somebody who studies any biological materials (as opposed to North America where it relates only to human remains). In Britain, bioarchaeology could include the study of macroscopic/microscopic plant remains, animal bones, molluscs, or human remains. As the Preface to this book shows, however, the term bioarchaeology has seen a long history in Britain, which stretches back to Clark’s work at Starr Carr (1972). At that time, the term was reserved for plant and animal remains, whereas “osteoarchaeology” has become (since the early 1980s) the word in Britain associated with the study of both human and animal remains (as seen in papers represented in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, founded in Britain in 1991, and in the names of a number of MSc courses). However, it should be noted that Vilhelm Møller-Christensen in Denmark had already referred to the term in the 1950s (1973; see Preface). Previous to these more recent developments, the term environmental archaeology encompassed the study of all archaeologically derived biological materials, and of interest here is the Association of Environmental Archaeology, based in Britain, whose members 419concentrate on any biological materials, but rarely human remains (Association for Environmental Archaeology home page). Another oddity is the lack of understanding of all these terms by the British archaeological community whereby, for example, a “palaeopathologist” commonly describes somebody who studies “human remains,” although strictly speaking it refers only to the study of ancient disease. The term “bioarchaeology” is used where appropriate throughout this chapter, but it should be understood that it is not by any means a widely accepted term in Britain for the study of archaeologically derived human remains.

III. THE STUDY OF BIOARCHAEOLOGY IN BRITAIN TO THE 1950S

A. EUROPE

By the second half of the 19th century, physical anthropology as a discipline in its own right had been recognized in Europe (Shapiro, 1959). Work by scholars such as Paul Broca, a surgeon in France (1873), and Rudolph Virchow, a physician and anatomist in Germany (1872), pioneered research on human remains. However, in terms of the study of disease, the German naturalist Johann Friederich Esper had already identified a neoplastic lesion in a cave bear’s femur (1774). The late 19th century also fixed the stereotype of the physical anthropologist with calipers in hand busily measuring heads (Shapiro, 1959), but by this time the wider implications of studying human remains had been realized in Europe. Interestingly, Shapiro (1959) believed that European physical anthropology then began to influence its development in North America; I shall argue later that the influence reversed in later years with reference to bioarchaeology. Of note, however, is the work of Marc Armund Ruffer (1859–1917), a French/German medical doctor, who appears to have taken the study of human remains beyond the curiosity stage to attempt to understand palaeoepidemiology (e.g., 1913). It was he that coined the term “palaeopathology” (Aufderheide and Rodriguez-Martin, 1998:6).

B. BRITAIN

Early work in physical anthropology in Britain was done by many scholars. In the 19th century, biometric studies became prominent, with Karl Pearson (1857–1936) of University College, London, and Geoffrey Morant (1899–1964), a “disciple” of Pearson (Stepan, 1982:137), contributing in the area of the evolutionary significance of Neanderthals and the origin of modern humans 420(Spencer, 1997d). However, skeletal remains of early humans in Britain have always been rare and overshadowed by finds elsewhere. Although late Upper Palaeolithic remains have been found in Britain, little can be said of this time period because of the scarcity of data (Roberts and Cox, 2003). A British interest in craniology was also established in the 19th century, as elsewhere in Europe, the impulse coming from phrenology (e.g., Davis and Thurnam, 1865). In 1800 all British scientists thought (like the rest of Europe) that there was a single human biological species united by a common humanity (Stepan, 1982). However, by the end of the 18th century there was doubt about a single created species. Polygenic thought specified that human “races” were separated from each other by mental, moral, and physical differences, in the manner of species. By the 1860s polygenism was a distinct but minority strand of British racial thought, specifying that the “races of humankind formed separate biological entities created independently of each other” (Stepan, 1982:3). By this time, too, whites were considered superior to nonwhites and “… culture and the social behaviour of man became epiphenomena of biology” (Stepan, 1982:4); science followed the public opinion of “race.” During the 1860s, new sciences in Britain shaped the study of “race” and these included comparative anatomy, physiology, histology, and palaeontology. Information on human racial variation was gathered and, although there was less reliance on the Bible for ideas, there remained an insistence on the permanency of racial “types” (Stepan, 1982). By the close of the 19th century, “race” was firmly established in popular opinion and science in Britain. Between 1900 and 1925 the eugenics movement reinforced “race science,” although in Europe this was never as extreme as in other parts of the world (Stepan, 1982:111). By the first years of the 20th century the eugenics movement became established and by the 1920s this was almost a worldwide movement. The eugenics movement aimed to explore the hereditary nature of traits in human populations that were desirable or undesirable and to establish variability in individuals, with the ultimate aim of classifying people.

Karl Pearson took a “statistical population approach” and explored the belief that evolution proceeded by small and continuous variations (Stepan, 1982:136). However, some physical anthropologists determined “racial” averages on just a few skulls, and Pearson was of the opinion that this was unacceptable; standards of recording the variables to determine “averages,” which affected comparative studies, were criticized and environmental factors affecting these variables were also highlighted (Stepan, 1982:136). Pearson’s interest in the people of Britain, and his obvious criticisms of other work to identify groups of people with the same biological features, led to his opinion that “there was no such thing as a physically and mentally ‘typical’ Englishman” (Stepan, 1982:137). His recognition of this fact early in the history of the study of physical anthropology underpins how the study of human remains from archaeological sites in Britain has developed, and his view that there was no relationship between physical and 421mental traits was inspirational for that time period. Nevertheless, his thoughts and opinions fell on deaf ears (Stepan, 1982). Pearson (1899) with Bell (Pearson and Bell, 1919) also wrote on the stature of prehistoric “races” and the character of the long bones of the English skeleton, both studies involving large numbers of skeletons/bones.

Following Pearson, the anatomist Arthur Keith (1924) published on a range of subjects, such as human remains from early cave deposits, and Parsons and Box (1905) wrote about the relationship of the cranial sutures to age. Cave studied a variety of subjects such as cervical ribs (1941) and trepanation (1940), and the anatomist Warren Dawson (1927) worked on mummified remains mainly from Egypt. Another British anatomist, Frederic Wood-Jones (Elliott-Smith and Wood-Jones, 1910), studied skeletal remains from Egypt; Elliott-Smith and Wood-Jones’ work is undeniably an innovative piece of work because of the number of remains studied at that time. Later, Kenneth Oakley (1950) was involved with the relative dating of the Piltdown skull, but also considered subjects ranging from trepanning (Oakley et al., 1959) to ancient brains. In the 1960s, Berry and Berry (1967) were instrumental in applying methods developed from the study of non-metrical variants in house mice to human skeletons, research that is used by many even today. Nineteenth- and early 20th-century work on archaeological human remains in Britain (and Europe) was very focused on specific variables that classified different groups of people and usually concentrated on normal rather than abnormal variation.

Early (palaeo) physical anthropology study in Britain had covered all aspects of the study of human remains: age and sex estimation and normal and abnormal variation. By the late 1800s Britain had established itself as one of the leading industrial nations of Europe and had created an unrivaled colonial empire (Spencer, 1997d). In the 1860s, the Anthropological Society of London (ASL) was established by James Hunt (1833–1869). Hunt also secured anthropology as a discipline in the British Association for the Advancement of Science; during the 19th and early 20th centuries much anthropological work was reported through this organization. By 1971 the ASL had merged with the Ethnological Society of London to form the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (Spencer, 1997d). The institute aimed to have a balance between its cultural and physical anthropological work, but the former always dominated.

At this point it is worth considering the many museums that were and are devoted to curating skeletal remains in Europe, skeletal remains that have been and will contribute to understanding our data. This of course includes the many museums that house skeletal remains from archaeological sites, but also those museums established in the 18th and 19th centuries as a result of collecting activities, principally by medical doctors and anatomists. Reviewed here are the main collections in Britain — examples of the tradition. The Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh Museum (The Royal College of Surgeons 422of Edinburgh home page) is one of the largest and most historic collections of surgical pathology in Europe, while the two Hunterian Museums in Glasgow and London are probably the most famous. The Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery was established in Glasgow in 1783; William Hunter (1718–1783) was born in Glasgow and studied medicine, becoming a well-respected anatomy and surgery teacher, and one of the first male midwives. He collected anatomical and pathological specimens plus other items, which were all bequeathed to Glasgow University (hunterian.gla.ac.uk/collections). The Hunterian Museum in the Royal College of Surgeons, London was established as a result of the collections of John Hunter (1728–1793), brother to William and a surgeon and anatomist. This private museum in the Royal College of Surgeons acquired his collection through the government on the day after his death in 1799 (Fforde, 1990). Following extensions to his original collection by scholars such as Arthur Keith, by the end of the 19th century 65,000 specimens existed. The collection includes human and animal pathology, physiological, and anatomical specimens. However, in the 1941 bombing of London, two-thirds of the collection were destroyed, but later the remaining collection was separated into “anatomical and pathological,” “odontological,” and “Hunterian” museums (The Royal College of Surgeons of England). Over the last few years the museum has been reorganized and refurbished, being opened by HRH Princess Anne in early 2005.

Perhaps of more relevance and direct interest to people working on human remains from archaeological sites is the Duckworth Osteological Collection at Cambridge (named after a former reader in anatomy, W. L. H. Duckworth). The collection has been assembled over the last 150 years by professors of anatomy (Foley, 1990; University of Cambridge, Duckworth Laboratory web site), and now there are over 17,000 human and nonhuman primate skeletal items (University of Cambridge, Duckworth Laboratory web site). The Natural History Museum in London also curates the famous collections of skeletons from Christchurch, Spitalfields. Three hundred and eighty-three skeletons are historically documented with age-at-death, sex, and date of death (Molleson and Cox, 1993). Undoubtedly these museum collections have been very valuable for educating people from different backgrounds about our ancestors. Important for bioarchaeology, these collections have facilitated the opportunity to observe the features useful for identifying age-at-death and sex, and dry bone pathology, in skeletons with known age, sex, and medical histories. However, in contrast to America [the “Robert Terry Collection,” Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (Hunt and Albanese, 2005), and “Hamann Todd Collection,” Cleveland, Ohio] and Portugal (the “Identified Skeletal Collection” in Coimbra and the “Luis Lopes” Collection in Lisbon), where there are large collections of complete skeletons that are documented, much of the skeletal collections in the museums in Britain described earlier that have “modern” collections mainly curate individual bones more often than complete skeletons.

423IV. THE SECOND HALF OF THE 20TH CENTURY

A. EUROPE

It was not until the 1950s and 1960s that more extensive and innovative research on human remains was seen where a truly bioarchaeological approach was taken using large amounts of data collected from many skeletons. Turning back to the rest of Europe briefly, we should consider the work of Vilhelm Møller-Christensen (Bennike, 2002) and his seminal work on the bone changes of leprosy as seen in late medieval Danish skeletons from a number of sites (Møller-Christensen, 1961). Møller-Christensen (1903–1988) was a doctor in Denmark by trade but had a strong interest in archaeology (like Calvin Wells in Britain). His most famous work involved the excavation of the cemeteries of Æbelholt in the 1930s and the medieval leprosy hospital at Naestved between 1948 and 1968, including examination of the skeletal remains recovered. His excavation technique was termed “the osteoarchaeological technique” (Møller-Christensen, 1973), a term that has seen recent favor in the United Kingdom. He had criticized the methods archaeologists were using to excavate skeletons. His newly developed excavation technique involved excavating a “ditch” around the grave and then excavating the skeleton on top of the “pedestal” left (similar to the approach taken in an anatomy dissection room/operating theatre). Møller-Christensen’s contribution to bioarchaeology during those early years was mainly in his detailed observations of leprous bone changes at Naestved and his corresponding confirmation of the changes in contemporaneous leprous patients in other parts of the world. The rest of Europe has also contributed to our understanding of the past from a bioarchaeological perspective, although the archaeological context has not always been of prime importance in the final interpretation. We now turn to focus in more detail on Britain.

B. BRITAIN

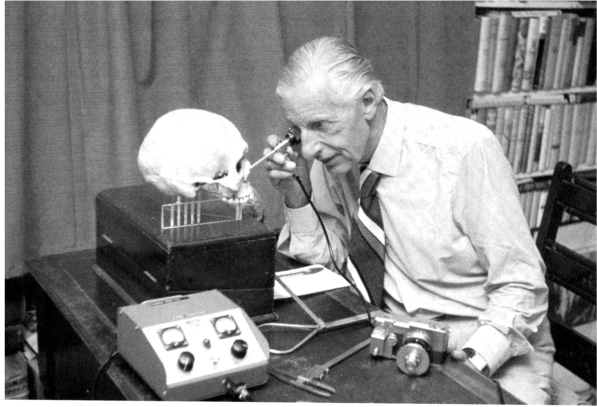

In Britain, two key people really advanced the study of human remains from archaeological sites from a bioarchaeological perspective: Calvin Wells (1908–1978) and Don Brothwell (born in 1933), the former a doctor from Norfolk. Both practitioners were unaware of the term “bioarchaeology” when they were working in the early years, and for Don Brothwell it will only have become a term used in more recent times. Nevertheless, their approach was bioarchaeological and, for Brothwell, remains so. The late Calvin Wells (Fig. 1) had a strong interest in archaeology and soon became the person in Norfolk who would produce reports on human remains for archaeologists (e.g., 1966). From this he consequently noticed interesting pathological lesions (e.g., 1965), not a 424real new development in physical anthropology as “case studies” were already prominent and have been maintained throughout the 20th century and into the 21st in Britain and elsewhere. Of recent relevance here is Mays’ (1997) review of the study of palaeopathology in Britain and the United States. Of seven journals considered between 1991 and 1995, 51/90 (57%) papers were on palaeopathology and 55% (28) were case studies compared to 15/53 or 28% in the United States. When population studies of palaeopathology were considered there were 14 (27%) from Britain compared to 23 (43%) from the United States. Although in recent years this has improved, people working in Britain still need to consider more hypothesis and question driven approaches to the study of past populations, including comparisons with other studies, and this includes any physical anthropological study.

Figure 1 Calvin Wells (with permission of the Department of Archaeological Science, University of Bradford).

Calvin Wells started publishing in the 1950s (Wells and Clarke, 1955) and quickly became known for his “stories” about people in the past that he inferred from what he observed from their skeletal remains. While many question his interpretations of the data (e.g., his paper on skeletal changes of “rape” in an Anglo-Saxon woman; Hawkes and Wells, 1975), he “brought alive” the people he was studying and considered not only biological data, but the relevant archaeological evidence.

The pattern of disease and injury that affects any group of people is never a matter of chance. It is invariably the expressions of stresses and strains to which they were 425exposed, to everything in their environment and behaviour. It reflects their genetic inheritance (which is their internal environment), the climate in which they lived, the soil that gave them sustenance and the animals and plants that shared their homeland. It is influenced by their daily occupations, their habits of diet, their choice of dwellings and clothes, their social structure, even their folklore and mythology. (Wells, 1964a: 17)

These statements should be followed by all bioarchaeologists attempting to reconstruct the health status of a past population. His work was phenomenal in breadth and included two books, most notably Bones, Bodies and Disease (1964a; Fig. 2), and eight chapters in books, e.g., the paper on radiography of human remains (1963) and that published on pseudopathology (1967a). He also published alone, and with others, over 100 papers in journals (fully listed in Hart, 1983). The papers are wide ranging and include population studies (almost 40 reports on inhumations and cremated burials from different periods and geographic locations in Britain). For example, his extremely detailed study of the burials from the Roman–British cemetery at Cirencester, Gloucester (1982) shows his attempt to place the burials in context to be able to interpret his findings. He also published on many pathological conditions affecting the skeleton. This includes fractures, Paget’s disease, malignant disease, leprosy, and obstetrical problems, and he studied the link between pollution and health using maxillary sinus evidence (the first of its kind in the world; Wells, 1977), and the evidence for the treatment of long bones fractures (1974). He delved into diseases in other animals (e.g., 1964b), considered the history of disease from other perspectives such as sculpture (e.g., 1968) and surgical instruments (e.g., 1967b), and even made a set of videos as a teaching tool at the Castle Museum in Norwich with the University of East Anglia. How he managed to do all this and practice as a doctor is unknown! Wells should be considered, along with Brothwell, a bioarchaeologist in the American definition sense. Some criticize his background as being inappropriate in some respects to studying and interpreting human remains from archaeological sites (he was a doctor and not an archaeologist/anthropologist). However, he did consider his biological data from the point of view of context, even though this was usually only in a broad manner. In fact, he was of the very strong opinion that physical anthropologists should not be attempting to diagnose disease in skeletal remains if they were not medically trained. However, it is now widely accepted that any number of educational backgrounds can contribute in different ways to our knowledge of the human past.

Don Brothwell (Fig. 3) is the other key figure in bioarchaeological study in Britain [see a recent tribute to his work in Dobney and O’Connor (2002)]. He graduated in 1956 from Cambridge with a BSc in anthropology and archaeology (with geology and zoology). This perhaps explains his diverse interests in bioarchaeology. Commencing publishing also in the 1950s, he has made a huge impact on many a scholar’s work from a global point of view, and still does. Unlike Calvin Wells, he has worked on a much wider range of biological materials, including practically based considerations of biological evidence from human and nonhuman skeletal remains and mummified materials; he has also contributed to theoretical debates about the human and animal past. His 16 authored/edited books have proved influential throughout his lifetime, particularly Diseases in Antiquity (Brothwell and Sandison, 1967), Digging Up Bones (1963c, 1981), Dental Anthropology (1963b), Science in Archaeology (Brothwell and Higgs, 1969, revised and enlarged edition), Handbook of Archaeological Sciences, (Brothwell and Pollard, 2001), and Skeletal Biology of Earlier Human Populations (1968). Brothwell and Sandison (1967) provided a survey of knowledge of disease and injury in the past from human remains at that time, a source book that many return to time and again today. His book in 1981 provides a general survey of the study of human remains from all aspects and puts data into archaeological context. “Digging up Bones” (Fig. 4) was a landmark book used by many, including field archaeologists, and is currently being revised for a new edition; it has been translated into other languages. Of course he has published many papers and book chapters on a wide variety of subjects (around 150). These include palaeodemography (1972–1973), dental wear as an indicator of age (1989), many on palaeopathology, e.g., neoplasms (1967), trauma (1999), the history of syphilis (1970), tuberculosis (Morse et al., 1964), paralysis and possible diagnoses in skeletal remains (Brothwell, 2003a), and early humans (e.g., 1960), and the zoonoses (1991). He has also published on demography and health of skeletal samples from various sites of all periods in Britain, plus more focused studies on dental disease, leprosy, amputation, trepanation, trauma, congenital disease, cannibalism, epigenetics, metrical analysis, radiography, scanning electron microscopy, pollution in the past, and hair analysis. Unlike most people working in bioarchaeology he has, furthermore, contributed to the study of mummified material (e.g., 2003b). Of all his contributions, the zoonoses and their impact on humans is an area that needs much more work in bioarchaeology and much more of an integrated approach between archaeozoologists and people studying human palaeopathology. Brothwell also published (with Baker) in 1980 the only review of animal diseases in the archaeological record, but this work has yet to stimulate much reaction in the archaeozoological world. Although many diseases can be transmitted to humans from animals (e.g., tuberculosis; Roberts and Buikstra, 2003), reflecting their close economic association and their clear relevance to appreciating impacts on human health, there has been little advance in this field of study. However, the problems of studying animal bones for evidence of disease have been outlined by O’Connor (2000), and it seems that the development of the methodology for recognizing and interpreting pathological changes in animal remains is badly needed. Britain is well placed to do this in the future.

426

Figure 2 Cover of Bones, Bodies and Disease.

427

Figure 3 Don Brothwell (courtesy of the Department of Archaeology, University of York).

428

Figure 4 Cover of Digging up Bones.

429Keith Manchester, another doctor, but this time from West Yorkshire, followed in the same vein as Calvin Wells and has published numerous papers from a bioarchaeological standpoint. Most notable is his work on the infectious diseases, especially the diagnostic features of leprosy (e.g., Andersen and Manchester, 1987), and his commentary on the cross-immunity hypothesis in relation to leprosy and tuberculosis (1984). His book (1983) was a landmark in the study of palaeopathology, where he considered the history of disease from a theoretical and practical standpoint, incorporating the history of medicine, where appropriate; this book has now evolved into its third edition (Roberts and Manchester, 2005). Cecil Hackett (1967) and Eric Hudson (1965) also contributed to our knowledge of the infectious diseases and focused on the history of syphilis. Both were physicians, like Wells and Manchester, who had a strong interest in the history of disease and attempted to explain the evidence using a socioeconomic context. Hackett used his experience of working with treponemal disease in other parts of the world to develop diagnostic criteria for the treponematoses (1976). Other people with medical training have, over the years, been part of the development of human bioarchaeological study, including the late Juliet Rogers, who contributed so much to our understanding of joint diseases and their diagnosis and interpretation in archaeological contexts (Rogers, 2000; Waldron and Rogers, 1991; Rogers and Waldron, 1995). Tony Waldron himself has made notable contributions to the literature on joint disease (e.g., 1992), made us think about palaeoepidemiology (1994), and emphasized that determining occupation from bone changes in the skeleton is by no means easy (Waldron and Cox, 1989).

Teeth have also been a focus for several people in Britain, most notably Dorothy Lunt, a dentist from Scotland who prepared many dental reports for skeletons excavated from archaeological sites (e.g., 1972), and Simon Hillson. Hillson’s books have had a large impact on scholars around the world (1986, 1996) along with his papers focusing on diagnostic criteria (e.g., 2001; Hillson et al., 1998). The 1980s, 1990s, and into the new millennium have 430also seen a number of scholars contributing to bioarchaeological studies, such as Chamberlain on palaeodemography (2000), the late Trevor Anderson on a variety of subjects (e.g., 1994), Lewis’ work on medieval child health (2002), Brickley’s work on metabolic disease (2000), Cox’s particular contribution to post-Medieval skeletal analysis and interpretation (1996), Molleson’s work on a wide range of subjects (e.g., 1989; Molleson and Cohen, 1990), and McKinley’s monumental work on cremations and many other aspects of human remains study (e.g., 1994, 2000). Finally, Simon Mays of English Heritage has contributed tremendously to bioarchaeological studies of human populations in Britain, with his work ranging from bone reports to studies on osteoporosis (1996a), amputations (1996b), infanticide (Mays and Faerman, 2001), treponemal disease (Mays et al., 2003), and biomolecular studies on tuberculosis (e.g., Mays et al., 2001). His book (1998) and edited book with Cox (2000) have been particularly influential in a global sense and have contributed in part to putting the study of archaeological skeletal remains “on the map.”

However, of particular note is Britain’s contribution to biomolecular studies of archaeological human remains since the early 1990s. Analysis of ancient DNA (e.g., Taylor et al., 2000; Bouwman and Brown, 2005) and mycolic acids (e.g., Gernaey et al., 2001) to diagnose disease and stable isotopes to reconstruct palaeodiet (e.g., Richards et al., 1998) and mobility of populations (e.g., Montgomery et al., 2005) have all been used to answer specific questions about the archaeological past in Britain. Nevertheless, while some of this work in Britain may appear to some, in many respects, to be at the forefront in the world, the use of stable isotopes to address questions of palaeodiet has seen little attention until recently compared to the New World; this has mainly come through work by Mike Richards and his students (e.g., Richards et al., 2000).

V. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS AFFECTING THE PROGRESS OF BIOARCHAEOLOGY AS A DISCIPLINE IN BRITAIN (LATE 20TH CENTURY TO DATE)

A. TRAINING

In the 1980s, a major development occurred in Britain that has become unique in the world: the establishment of 1-year masters courses, which involved taught courses and a research dissertation; surprisingly North America has not followed this lead. This was a key turning point from which the study of bioarchaeology was placed on a firm footing and encouraged “practitioners” to take a more holistic view of human remains study by considering the biological evidence for people within its archaeological context. Up until this time, the only people 431who had really taken a serious bioarchaelogical approach were Calvin Wells and Don Brothwell.

The Institute of Archaeology, University College, London, and the Department of Archaeology and Prehistory, University of Sheffield commenced masters courses in the study of human/animal remains and human remains, respectively, in the 1980s. Small numbers of students were given the chance to specialize in an area of archaeological study that had, until then, been the remit of doctors, dentists, and anatomists in their spare time. Until then too, archaeology departments had not, on the whole, provided any undergraduate training in human bioarchaeology, although anthropology departments naturally taught human evolution using skeletal casts. When looking back, it was therefore not surprising that work on human remains was usually devoid of any integration of biological data with archaeological context. By 1990, a joint Universities of Bradford and Sheffield course (MSc in Osteology, Palaeopathology, and Funerary Archaeology) had been initiated and ran very successfully with international recruitment for 10 years until the two universities decided to go it alone.

Since 1990 other MSc courses have been set up at the universities of Bournemouth, Durham, Edinburgh, and Southampton, with variations on the theme including MSc courses in forensic archaeology and anthropology and skeletal and dental bioarchaeology (Institute of Archaeology, University College, London). If the Bradford/Sheffield course was being set up now it would probably have been named an MSc in Bioarchaeology, especially to attract North American students! What’s in a name? Universities in Britain would say “a lot of money potentially.” Therefore, as of the early 21st century we now have a plethora of MSc courses running in Britain, training people from mainly archaeological and anthropological backgrounds; with this background they are able to approach the study of skeletal remains from a truly bioarchaeological standpoint, and some of us would have welcomed these courses when we were younger! It has also encouraged students to extend their studies into Ph.D. programs, where they are much better prepared to do their research. The MSc course in Britain is equivalent to the 2-year masters program in North America, which then leads on to a Ph.D. These masters courses have transformed the nature of how people in Britain study the skeletal past, have opened up the eyes of higher education to the potential of this area of study in archaeology, and have ultimately led to more posts being created for physical anthropologists in archaeology departments. However, creating more qualified people has produced a problem for employment of these graduates in jobs that use the skills they have acquired. Most people work in museums and with contract archaeological units as practicing field archaeologists with osteological expertise, but many go on to a Ph.D. program (with inevitable competition for limited funding). The units appear to now recognize the expertise that these graduates can bring with both their archaeological/anthropological and their osteological backgrounds.

432Research students in bioarchaeology have also increased. However, it is pleasing to see that more wide-ranging themed projects, with hypotheses to test and questions to answer, are being tackled that use a bioarchaeological perspective in the interpretation of data (a clear move away from the “cottage industry”; Roberts, 1986). This can only be seen as a good thing and a positive development from the often narrowly focused projects undertaken back in the 1980s. As an extension to the masters courses, short courses in palaeopathology have developed, mainly because of Don Ortner’s commitment to teaching. Don Ortner, along with Walter Putschar, taught a short course in palaeopathology from 1971 through 1974 at the Smithsonian Institution. After a break to write their book, this course ran again in 1985 at which the author was present (along with some other authors in this book). Through his research links through Keith Manchester and the author at the University of Bradford, short courses were held at Bradford in 1988, 1994, 1998, 2001, 2003, and his last in 2005. However, it is anticipated that these short courses will continue in the future.

B. THE MEDIA

Of interest is the parallel development in the 1990s of a very strong desire by the media in making television programs involving skeletal and mummified remains. The BBC’s “Meet the Ancestors,” Channel 4’s programs in the series “To the Ends of the Earth” and “Secrets of the Dead” and programs in the “Timewatch” series have enthused the public and developed their interest in the study of human remains as a subdiscipline of archaeology. In Britain if a program has three to four million viewers, this is considered a success (which the aforementioned always have had).

C. STANDARDS FOR RECORDING DATA

There have been a number of developments in bioarchaeology in Britain and Europe, developments that are both positive and negative. Although, again, late in coming compared to North America, standards for data collection and reporting of skeletal material have been published for Britain (Brickley and McKinley, 2004; Fig. 5). Its stimulus was Roberts and Cox’s experiences of collating palaeopathological data from published and unpublished sources for their book (2003). The lack of standards for data collection and reporting was clear, but acknowledged as a historical development that had not been addressed or discussed within the “bioarchaeological” community. Following a workshop between the authors of chapters in the publication (very like that which preceded Buikstra and Ubelaker, 1994), the final volume was produced. Along with the volume, and developments in training at masters level in Britain, it is anticipated that bioarchaeological data produced from Britain will improve markedly in the future. Of interest, however, are the different stimuli that led to both these publications; unlike for Britain, the repatriation and reburial act in the United States precipitated the need to record data in a standardized way before skeletons were repatriated and/or reburied (NAGPRA; Rose et al., 1996). In Britain, we may be glad that we also have standards for recording now as we see more controls on our skeletal resource (see later). Another stimulus to the production of good quality data in Europe as a whole has been the establishment of the “Health in Europe Project” based at Ohio State University in Columbus and headed by Richard Steckel (Steckel et al., 2002). In this project, an extension of the Western Hemisphere Health project (Steckel and Rose, 2002), a standard on-line recording form has been developed for participants to use in the coding of thousands of skeletons curated across Europe. This process should enable valid comparisons to be made of data both geographically and temporally; it will also incorporate contextual information that will allow a bioarchaeological approach to be taken once all data have been collected.

433

Figure 5 Cover of Brickley and McKinley (eds.) (with permission of the Institute of Field Archaeology and BABAO).

434D. DATABASES AND THE BURGEONING “GREY LITERATURE”

One of the major problems to advances in human bioarchaeological study in Britain and elsewhere in Europe is the lack of cohesion in knowledge of our resource base, although there have been some developments recently, such as the medieval cemeteries database (Gilchrist and Sloane, 2005). First, there remains no database of skeletal collections available for study in Britain, or where they are curated, which makes generating and carrying out research proposals difficult. Second, much of the work on skeletal remains that exists in Britain is published in the “grey literature” and may never come into the public domain. For example, of the 311 reports on human skeletal remains considered for Roberts and Cox (2003), 38% were unpublished, and access to their contents was enabled only through very cooperative colleagues willing to share data. Without knowledge of what has already been done, it is impossible to identify gaps in our knowledge about the past from a geographical and temporal point of view. Much of this problem has become more apparent since the introduction of Policy Planning Guidance 16 (1990), where archaeologists bid to gain archaeological work in advance of development (“contract archaeology”); the cheapest bids often get the work, including that for analyzing skeletal remains that are excavated, and the quality of the work can thus be poor. In addition, much of the work may never be published; for example, the author produced many reports in the 1980s but only a handful have been published.

435E. CONTROLS ON OUR SKELETAL RESOURCE: REPATRIATION/REBURIAL/DAMAGE?

The second major problem that may prevent advances in bioarchaeological study in the future is the threat to survival above ground of our skeletal collections. In 2001 the British government (Department of Culture, Media, and Sport) established a working party to consider the future of skeletal remains in museums and other institutions in Britain. Initially this was aimed at remains from elsewhere in the world but it is clear that all remains could be at risk; in 2005, a report was produced (Department of Culture, Media, and Sport, 2005). This was supplemented by a report from the Cathedrals and Church Buildings Division of the Church of England and English Heritage’s Human Remains Working Group (Church of England and English Heritage, 2005). This report looked at ethical, legal, and scientific issues to agree on guidelines covering the excavation and treatment of Christian burials in archaeological projects and their reburial. Ireland and Scotland already have guidance on the treatment of human remains (Historic Scotland, 1997; Heritage Council, 2002), in addition to guidance on the law and burial archaeology in England (Garratt-Frost, 1992). Clearly, the spotlight is on skeletal collections in Britain, and better guidelines for their treatment were badly needed, but it would be regrettable if eventually all skeletal remains were unavailable for study in the future in Britain. As Buikstra and Gordon (1981) have indicated, the retention of skeletal remains for future research is very beneficial, especially with the rapid advancement in analytical techniques (although destructive sampling for biomolecular analysis should be carefully controlled and restricted to proposals of real scientific value). What is happening in Britain appears to follow earlier developments in the United States (Rose et al., 1996), as are so many aspects of our lives today!

Of relevance to maintaining the integrity of our resource is a recent study of damage that may occur through handling of skeletal remains and the need to limit that damage (Caffell et al., 2001). In Britain, particularly, the proliferation of masters courses (and Ph.D. students) has led to pressure on the handling of skeletal remains curated in universities (and on skeletal samples in other institutions such as museums through masters and Ph.D. dissertations). This might be expected to be an inevitable outcome but up until recently little thought has been put into controlling access and limiting damage to such a valuable resource. As an extension of the work of Caffell and colleagues, Bowron (2003), a conservation masters student at Durham University, developed a box suitable for skeleton curation to prevent needless damage during use. This boxing system is slowly being recognized in museums as a solution to prevent damage, but the curatorial state of skeletal collections in many museums is far from ideal.

436F. RESEARCH FUNDING

Funding for research in bioarchaeology in Britain has been reasonably generous over the years but the type of projects funded has changed. In the 1980s, basic research on palaeopathology was likely to get funded from a number of funding bodies (Natural Environmental Research Council, www.nerc.ac.uk; Wellcome Trust, www.wellcome.ac.uk). However, from the mid-1990s research funding is now more focused on biomolecular studies such as aDNA and isotope analysis, although the range of funding bodies supporting such research has increased. Of particular note is the bioarchaeology awards program from the Wellcome Trust, a program that ran for 10 years until 2005. Its aim was to fund research on the history of human disease, health, and human evolution and biocultural adaptation. It provided excellent career opportunities for many and granted thousands of pounds to bioarchaeological research, using cutting-edge biomedical techniques of analysis. This trend in concentrating funding on biomolecular work in some respects is unfortunate because there is much basic work in bioarchaeology to be done in Britain and many skeletal samples have not yet been studied using standard methods of data collection nor have data been interpreted in relation to context. Perhaps one exception to this funding anomaly has been the generous funding by the Wellcome Trust of the Centre for Human Bioarchaeology and the Spitalfields project at the Museum of London. This has enabled a number of people to be employed to undertake the basic analysis of several thousand skeletons from a late medieval site, and the creation of a database of human skeletal remains from London sites (Museum of London home page).

Despite restricted funding for bioarchaeology in Britain over the years, there have been many significant contributions to bioarchaeology in a global sense. While an integrated approach to studying human remains has been slow in arriving in Britain, and much work remains unpublished, some of the work over the years has been influential in the world of bioarchaeology. For example, Britain has set standards for recording specific diseases (e.g., Rogers and Waldron, 1995), generated hypotheses to test (e.g., Manchester, 1984), stimulated interest in animal palaeopathology (Baker and Brothwell, 1980), and undertaken hypothesis-driven population studies (e.g., Roberts et al., 1998).

There have also been some recent bioarchaeological studies fully integrating mortuary analysis with biological data (e.g., Buckberry, 2004; Gowland, 2002, 2004; Loe, 2004; recent Ph.D. submissions by Groves and Redfern; and a critique by Tyrrell, 2000), although more work needs to be done in this area (a forthcoming book may address this gap; Gowland and Knüsel, for 2006). There have also been some recent stable isotopic studies that have utilized biological and funerary data such as grave goods (e.g., Montgomery et al., 2005), although interpretations can be problematic (e.g., Privat et al., 2002). Work up 437to now, when its exists, has been by “funerary archaeologists” who have tended to use both biological and funerary archaeological data but often with a poor understanding of the subtle nature of biological data (e.g., Harke, 1990; Stoodley, 1999), especially with respect to palaeopathology. This is seen as a problem of the science/theory “divide” in Britain.

Furthermore, even though much of it will never be seen by the rest of the world because it is published in inaccessible form (or not published at all), there are hundreds of “skeletal reports” on individual skeletons, small and large groups of individuals, from prehistory to the post-Medieval periods, in most areas of Britain; some of these reports are very much bioarchaeological studies (e.g., Molleson and Cox, 1993; Boylston et al., 2001; Brickley et al., 1999). However, and unfortunately, if studies such as these do not reach the international peer-reviewed literature they remain invisible to the global bioarchaeological community.

In Britain we are fortunate to have a wealth of skeletal collections, a huge range of archaeological data to make bioarchaeological interpretations, and contemporary historical records from the medieval period onward. Another strength, but one that is not used particularly well, is a very strong tradition in the study of the history of medicine, grounded at the Wellcome Trust in London and other centers around Britain. While both bioarchaeologists and medical historians in Britain recognize the strengths of their opposites, there is little attempt to develop complimentary research proposals or activities, although there have been recent attempts (Maehle and Roberts, 2002). However, there have been a series of successful conferences in Europe [France, on syphilis (Dutour et al., 1994); Hungary, on tuberculosis (Pálfi et al., 1999); Britain, on leprosy (Roberts et al., 2002); and France, on the plague] where clinicians, medical historians, molecular biologists, and bioarchaeologists have come together to discuss the same disease from their own perspectives. Furthermore, the European Anthropological Association (European Anthropological Association home page), the European members of the Palaeopathology Association (Palaeopathology Association home page), and the British Association of Biological Anthropology and Osteoarchaeology (BABAO home page, Fig. 6) are very active in promoting bioarchaeological study. The BABAO has been a uniting force in Britain since its establishment in 1998, and with its excellent web site, annual conference, “Annual Review” publication, and an active email list, “bioarchaeological activity” has increased considerably.

VI. THE FUTURE FOR BIOARCHAEOLOGY IN BRITAIN

This chapter has perhaps painted a bleak picture of bioarchaeology in Europe, particularly Britain. However, the future looks particularly bright. We now have many scholars with the “right” background to fully appreciate the need to integrate biological data from human remains with archaeological data to test hypotheses and answer questions about our past. We are moving toward developing a database of curated human remains in Britain that will help scholars locate the right skeletal samples for their research questions. There are now skeletal recording standards to ensure that collected data in the future conform to a set pattern and can therefore be used for comparison with other “population” studies. Furthermore, we have an increased awareness in the field archaeological community that the study of human remains can offer considerable insights into our past. As a country, we have moved from physical anthropologists who were interested in studying human remains for their own sake, with little attempt to contextualize their data, to a proliferation of people (“bioarchaeologists”) who truly wish to do this and make their data matter to understanding our ancestors. However, there are real threats to our resource base of human remains, as discussed earlier. North American bioarchaeology grew up in a very different tradition when compared to Britain, a tradition (under the umbrella of “anthropology”) that emphasized an integrated approach. In Britain we have faced, and are facing, the same problems that North America has faced, but we are now in a position to rapidly “catch up” with our neighbors across the Atlantic.

438

Figure 6 Logo of the British Association of Biological Anthropology and Osteoarchaeology (with permission of BABAO).

439ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Jane Buikstra for inviting me to write this chapter and giving me a chance to reflect on how bioarchaeology has developed in Britain and the key factors in its “emergence.” Both Jane and Elsevier are also thanked for their patience in waiting for the chapter due to the author’s personal circumstances. Becky Gowland has also contributed to this chapter by enlightening the author to research linking funerary context with biological data from skeletal remains. Finally, Jeff Veitch at Durham University transformed Figs. 1, 2, and 4 into electronic versions, Martin Smith (Birmingham University), webmaster for BABAO, provided the BABAO logo, and Jackie McKinley (Wessex Archaeology) provided the cover image for Brickley and McKinley (2004).440