73Chapter 3

The Changing Role of Skeletal Biology at the Smithsonian

Douglas H. Ubelaker

I. INTRODUCTION

The history of physical anthropology at the Smithsonian Institution is closely linked with the development of American physical anthropology. The Smithsonian chapter in this story effectively began in 1903 when officials decided that physical anthropology should be represented in the already established anthropology effort. An ambitious, young physician turned physical anthropologist named Aleš Hrdlička (1869–1943) was hired to inaugurate this effort at the Smithsonian.

Physical anthropology had long been established in Europe as the comparative science of humankind through the work of Johann Blumenbach (1752–1840), Paul Broca (1824–1880), and others. This effort included new methodology (e.g., Blumenbach’s standard positioning of crania for comparative viewing and Broca’s craniometric techniques and designs of new measuring equipment), training (e.g., Broca’s Institute), and attempts to build comparative skeletal collections (e.g., Blumenbach’s collection of human crania, Spencer, 1997a,b).

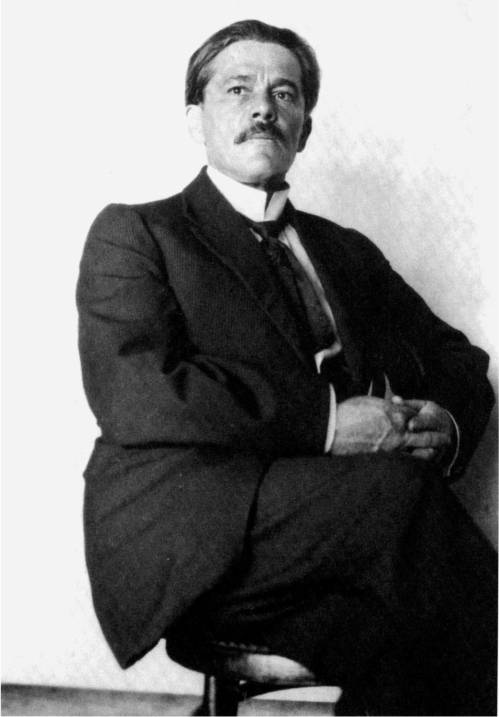

By the time Hrdlička (Fig. 1) became a professional in the late 19th century, physical anthropology and collection building had already begun in the United States. Hrdlička himself credits Samuel G. Morton (1799–1851) of Philadelphia for initiating this effort (Hrdlička, 1918, 1943a).

Aleš Hrdlička was born in Humpolec, Bohemia (now located in the southern Czech Republic). After immigrating with his family to the United States in 1881, he received his M.D. degree from New York Eclectic Medical College in 1892. Hrdlička also received training at the New York Homeopathic Medical College and exposure to techniques of physical anthropology and legal medicine in Paris. After working in private medical practice and with the New York Middleton State Homeopathic Hospital for the Insane, the Pathological Institute, and the American Museum of Natural History in New York, he joined the Smithsonian in 1903, where he spent the remainder of his career (Spencer, 1979; Stewart, 1940a; Ubelaker, 1999).

74

Figure 1 Aleš Hrdlička.

Like Morton, Hrdlička recognized the scientific need for comparative collections of human remains. Much of his pre-Smithsonian research had focused on the biological basis of abnormal human behavior. He had amassed extensive 75data on abnormal individuals but realized that to make sense of them he needed comparative information from normal individuals (Stewart, 1940a). Following Morton’s lead, Hrdlička worked to build the collections that would make this comparative research possible. Initially, this involved collaboration with George S. Huntington, anatomist with the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York, in assembling and conducting research on skeletons derived from medical school dissection (Stewart, 1940a).

As physical anthropology achieved growing visibility, the Smithsonian Institution recognized the need to add this speciality to its anthropology staff. Prior to that time, as discussed in Chapter 1, human remains acquired by the Smithsonian were transferred to the Army Medical Museum in Washington where they had received relatively little curatorial attention (Stewart, 1940a). In 1902, Smithsonian anthropologist William Henry Holmes requested that a Division of Physical Anthropology be established within the Department of Anthropology of the National Museum. According to Holmes, the purpose of this effort was “the comprehensive biological study of the many and diverse racial elements of the American nation, and the application of the results to promoting the welfare of the NATION” (Spencer, 1979:248). Hrdlička was hired in 1903 as the first physical anthropologist of this division.

Although Hrdlička likely viewed the new Smithsonian position as offering valuable potential for his collections and research interests, the necessary resources were not immediately available. According to Stewart (1940a: 12) “[o]n taking up his work in the National Museum Dr. Hrdlička found himself assigned to a small section of one of the galleries in the Old Museum building. His whole equipment consisted of an old kitchen-table, chair, a pen rack, inkwell, a pen and a pencil. Nevertheless, he was again in the position where he could plan the future course of an institutional branch of physical anthropology. He proceeded to build up his Division until it has come to rival in size and importance of collections the oldest and best in the Old World.”

It is important to note that at this early period in the development of American physical anthropology, Hrdlička conducted research and published in all major areas of the discipline (e.g., Hrdlička, 1894, 1895, 1896, 1897, 1899b, 1900, 1901; Lumholtz and Hrdlička, 1897, 1898). Gradually, his medical interests in the biological basis of abnormal behavior shifted toward a more comparative, anthropological focus (Hrdlička, 1902a,b,c). As he collaborated with archaeologists or conducted excavations himself, his intellectual engagement evolved with these new experiences. He published not only on the bones, but also on archaeological and ethnological topics (e.g., Hrdlička, 1903a,b, 1904a,b,c,d, 1905a,b,c,d, 1906a,b), as well as even more general ones (Hrdlička, 1909b, 1912c, 1919, 1920b, 1921a).

Hrdlička noted that the cornerstone of the developing field of physical anthropology consisted of the assemblage of large, well-documented collections of human remains from diverse sources. Through his own work and others, by 1918, 76he was able to report substantial progress. In the lead-off article of the first issue of the American Journal of Physical Anthropology (founded by Hrdlička), he remarked on collections available 50 years before in the United States and Europe:

… all this material was limited to crania, and was useful in arousing curiosity and false expectations rather than in leading to definite progress in our science. It required years of assiduous excavation and collecting before scientific work of any extent could anywhere be attempted. Such collecting, fortunately, has been carried on in a diligent and continued way to this day, until there are in this country alone several great and many lesser gatherings of identified skeletal and other anthropological material, led by that of the U.S. National Museum. Yet even now we are far from the goal in this direction; that is, from collections comprising adequate series of bones of the entire skeleton, besides those of other normal important parts of the body; collections that would enable us to determine the complete range of variation in these parts in at least the most significant groups of mankind. The requirements in this direction will appear more clearly when it is appreciated that, to determine the total range of variation in a single long-bone, such as the humerus, in any group to be studied, there are needed the remains of hundreds of adult individuals of each sex from that group. As it is, even the greatest collections we possess still fall short of the requirements, consequently our investigations can be seldom perfect or final. (Hrdlička, 1918:10)

The collection goals of Hrdlička, like his contemporaries in physical anthropology, were primarily to acquire comparative collections of normal individuals. Research on these collections was mostly aimed at providing “normal” perspective for other data on abnormal individuals and documenting the range of variation for skeletal attributes. Although Hrdlička made important contributions to paleopathology, despite his medical training, he did not concentrate his research in this area. Still, he recognized the need to curate the entire skeleton, not just the skull, the importance of documentation and dating of remains, and the need for large samples. Collections assembled by Hrdlička with these points in mind paved the way for future research in bioarchaeology.

II. T. DALE STEWART

Hrdlička retired in 1942 and died the following year. He was succeeded at the Smithsonian by his long-time assistant T. Dale Stewart (1901–1997). Like his predecessor, Stewart held a medical degree (Johns Hopkins, 1931), but from the beginning maintained a distinct skeletal focus (Stewart, 1930, 1931b). Stewart also encouraged the assembling of well-documented collections and published research in paleoanthropology (Stewart, 1959a,b, 1960a, 1961a,b, 1962a,b,c, 1963c, 1964) and other areas of anthropology (Stewart, 1953, 1954a). In contrast to Hrdlička, Stewart published regularly on paleopathology 77(Stewart, 1950a, 1966, 1969, 1974, 1979b, 1984a; Stewart and Quade, 1969; Stewart and Spoehr, 1952; Tobin and Stewart, 1952) and forensic anthropology (McKern and Stewart, 1957; Stewart, 1948a, 1954b, 1959c, 1968, 1970a, 1972, 1973a, 1978, 1979a,c,d, 1982, 1983, 1984b; Stewart and Trotter, 1955), emphasizing the importance of collections in this research. By improving storage and accessibility to collections, he increasingly made them available to outside researchers, enabling them to include Smithsonian collections in their own research designs. In the area of bioarchaeology, Stewart routinely analyzed human remains at the request of archaeologists and collaborated in studying direct cultural effects on the skeleton, such as cranial deformation (Stewart, 1939a, 1941a, 1948b) and intentional dental alterations (Stewart, 1941b, 1942; Stewart and Titterington, 1944, 1946). Like many of his colleagues of that time, Stewart tended to publish the results of his studies of remains from archaeological excavations as appendices of the archaeological reports (Stewart, 1940b,c, 1941c,d, 1943a,b, 1950b, 1951a, 1959d,e,f). However, his work included bioarchaeological investigation of ossuaries in the vicinity of the Smithsonian (Stewart, 1939b; 1940d,e, 1941e, 1992; Stewart and Wedel, 1937) and utilizing results of skeletal studies to address larger issues of population history (Stewart, 1973b). Stewart’s chapter in the saga of Smithsonian physical anthropology also demonstrates intellectual movement away from an emphasis on racial typology and classification of head shape toward problem-oriented detailed research.

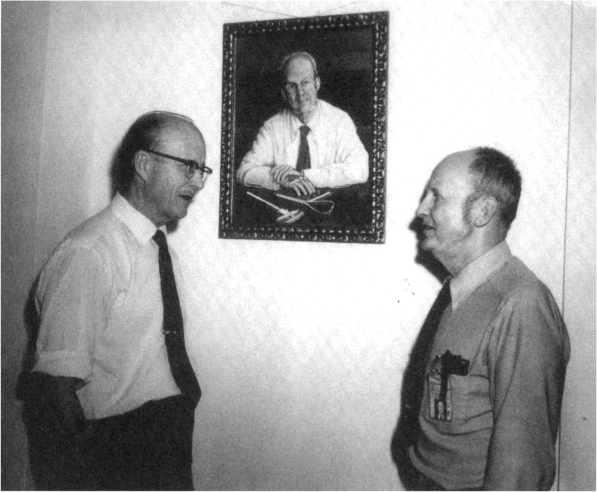

When Stewart became a museum director in 1962, the Smithsonian hired J. Lawrence Angel (1915–1986) from the Daniel Baugh Institute of Anatomy of the Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia (St. Hoyme, 1988; Ubelaker, 1989) (Fig. 2). Angel received his Ph.D. in 1942 from Harvard where he had worked extensively with Earnest Hooton (1887–1954). Like Hrdlička, Hooton’s interests were broad and included research into racial topology and the biological basis of criminal behavior. However, Hooton also published in skeletal biology. As noted in Chapters 2 and 4, his classic work, The Indians of Pecos Pueblo (1930), demonstrates an unprecedented intellectual interplay between skeletal analysis and archaeological observations that sets the stage for more recent studies of bioarchaeology.

Unlike Hrdlička, Hooton’s long tenure at Harvard generated many students who in turn greatly influenced the development of American physical anthropology. Hooton’s 19th Ph.D. student was J. Lawrence Angel. Working mostly in the eastern Mediterranean area, Angel expanded on Hooton’s ideas and methodology in bioarchaeology. Although Angel published a number of site reports and appendices, he also demonstrated how data amassed from such works could be used to address key anthropological issues of paleodemography and correlations of disease and culture, which he termed “social biology.” From his work emerged a sense that physical anthropologists involved in the excavation and analysis of human skeletal remains cannot only provide useful data to the archaeologists and use the samples in studies of human variation and paleopathology, but can also directly address broader anthropological issues.

78

Figure 2 T. D. Stewart and J. L. Angel with a portrait of Angel painted by Stewart.

Note that throughout his career at the Smithsonian, Angel worked just down the hall from Stewart. When Stewart returned to the Department of Anthropology in 1966 from his duties as director of the Museum of Natural History, he began a long period of research and writing, largely free of administration. This period also overlapped the career of skeletal biologist Lucile St. Hoyme, whose research included issues of bioarchaeology (Hunt, 2004).

Marshall T. Newman (1911–1996) worked at the Smithsonian in physical anthropology from 1941 to 1942 and then again between 1946 and 1962. Newman received his Ph.D. in 1941 from Hooton at Harvard, but left the Smithsonian to expand his teaching experience.

The summers of 1956 through 1959 also found William M. Bass working at the Smithsonian for the River Basin Surveys. During this time Bass conducted laboratory research in Washington and supervised mortuary site excavations in South Dakota. Bass pioneered bioarchaeology in the Plains and taught many students who have become leaders in this area of research.

79III. CURRENT ACTIVITY IN BIOARCHAEOLOGY

The current Division of Physical Anthropology at the Smithsonian’s Department of Anthropology of the National Museum of Natural History maintains a strong focus in areas of physical anthropology relating to bioarchaeology, although other areas of physical anthropology, such as population genetics and growth and development, are not well represented. This area of emphasis reflects hiring practices that have recognized the value and continued needs of the collections as well as areas of traditional strength.

Present staff of physical anthropology in the Smithsonian’s Department of Anthropology pursue research that combines archaeological technique and interpretation with the specialized anatomical knowledge of skeletal biology. This translates into more precision in measurement and disease diagnosis than was possible just a few decades ago, coupled with sophisticated integration with archaeological information aimed at anthropological interpretation. This work is possible because of the collections assembled by past workers with different problem orientations and because of the changing methodology of the field at large. The diversity of activity during Hrdlička’s time has been sacrificed in favor of more intense, detailed effort within the areas represented. Smithsonian skeletal biologists have managed mortuary site excavation and analysis with the aim of maximizing the amount of information retrieved in field recovery. Laboratory analysis enables information about disease, demography, stature, and other biological attributes to be correlated with site information. This research is consistent with that of colleagues throughout skeletal biology who also integrate mortuary site excavation information with that derived from laboratory analysis of human remains.

IV. REPATRIATION

Back in 1918, Hrdlička called attention to the special nature of human remains and how public sentiments about them can dramatically affect collections and related research. He noted:

The difficulties in gathering the requisite material, and even the crude data alone, have been and are still very great; in fact they are sometimes insurmountable. Religious beliefs, sentimentality and superstition, as well as love, nearly everywhere invest the bodies of the dead with sacredness or awe which no stranger is willingly permitted to disturb. It is seldom appreciated that the remains would be dealt with and guarded with the utmost care, and be used only for the most worthy ends, including the benefit of the living. The mind of the friends sees only annoyance and sacrilege, or fears to offend the spirits of the departed. This may not apply to older remains, but these in turn are frequently defective; yet even old remains are sometimes difficult to acquire. . . . (Hrdlička, 1918:11)

80Hrdlička likely would be shocked to learn just how far those sentiments recently have gone to shape bioarchaeological research. As also discussed in Chapter 15, legislation and policy formation have not only limited the acquisition and study of human remains, but have forced the transfer and loss to science of large collections of North American human remains of archaeological origin that already had been curated. United States Public Law 101–601, Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, Hawaiian Natives, Historic Preservation, H.R. 5237, 25 USC 3001, Nov. 16, 1990, addresses human remains, associated funerary objects, unassociated funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony that can be culturally affiliated with a present-day Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization. Upon request, such materials must be transferred to the appropriate group.

Although the Smithsonian Institution was exempted from the NAGPRA law summarized earlier, it was targeted by another similar law, the National Museum of the American Indian Act, Public Law 101–185, Nov. 28, 1989, 103 Stat. 1336, 20 USC 80q. This legislation requires the Smithsonian to identify the tribal origins (cultural affiliation) of human remains and funerary objects in its collections and, if requested, transfer them to the appropriate group.

Responding to federal legislation, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History formed an Office of Repatriation. A large staff is employed to assess the collections to determine which represent those factors targeted by legislation. Many of the human skeletal remains originating from archaeological sites within the United States are potentially affected, including material that Hrdlička collected and studied. A physical anthropology component of the laboratory collects standard information from the human remains in order to help determine the cultural affiliation and to salvage scientific information. Although many of these collections likely will be unavailable for future analyses, in the short term, the issue has forced attention to those remains, producing data collected in a standard format that may enable enhanced synthetic biocultural interpretation.

V. SUMMARY

The history of American activity in bioarchaeology research has recorded major changes and shifts of interest. In the 19th century, ancient mortuary sites were generally regarded by physical anthropologists as resources to be mined for comparative collections. These collections were desperately needed to document human variation and to test medically oriented theories. The Smithsonian’s Hrdlička was initially attracted to archaeological mortuary sites, not to understand ancient ways of life but to obtain the “normal” sample for his comparative studies of the biological basis of human behavior. Gradually, as he became involved 81in the necessary fieldwork, he became intellectually involved in the problems presented by the sites and the collections themselves.

Largely through the work of Hooton and his students, bioarchaeology evolved with the understanding that skeletal analysis could be coupled with mortuary site excavation to reach a greater understanding of past human populations. At the Smithsonian, this effort was championed by one of Hooton’s students, J. Lawrence Angel, especially through his work in the eastern Mediterranean. Also at the Smithsonian, T. D. Stewart demonstrated how careful research design, an attention to detail, and a problem orientation could enhance diagnosis of disease from bone and bioarchaeology research in general.

The 20th century also witnessed remarkable developments in the recovery and curation of human remains of archaeological origin. Through the early efforts of the Works Progress Administration (WPA)-sponsored archaeological projects, the Smithsonian-affiliated River Basin Surveys, and other archaeological investigation, well-documented human remains from archaeological contexts were assembled and available for research. Much of this material was deposited in the collections of the Division of Physical Anthropology of the Smithsonian because of the federal status of the Smithsonian and its traditional interest in such materials. Physical anthropologists such as William M. Bass not only increased cooperation with archaeologists in the excavation of human remains, but were available to excavate them directly.

By the 1970s, collections of well-documented human remains were available for research and of such size and documentation that remarkable research was possible on ancient biocultural patterns. It appeared that Hrdlička’s dream of adequate comparative collections would finally be realized.

However, the 1970s also witnessed an increase in concern on the part of contemporary American Indians and others about the appropriateness of maintaining those collections (Ubelaker and Grant, 1989). This concern led to law and policies that have forced a transfer of aspects of those collections to contemporary groups.

Despite these developments, research in bioarchaeology remains strong and increasingly synthetic and interdisciplinary. The Smithsonian Institution continues involvement in bioarchaeological issues not only by meeting the challenges of the repatriation legislation, but through vigorous research aimed at a greater understanding of past populations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Erica B. Jones for her assistance in manuscript preparation. Both illustrations are provided courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.82