As for electricity—without form or matter, thing-like but intangible, its qi inheres within all things and moves throughout the universe. Its utility is broader and more marvelous than that of all other things; it can be used for illumination, for transmission, for transportation, for rearing animals, for digging mines…. And yet, to draw on electricity one relies, of course, on power, and to produce power one depends on coal. Recently, however, there are those who have thought up a new method, which is to use the waterpower of waterfalls to generate electricity. If you store the energy mechanically then you could save it for use out of season anywhere it was needed. This is, moreover, something that can be extracted without limit and used without depletion.

The Yangtze Gorge Project is a “CLASSIC.” It will be of utmost importance to China. It will bring great industrial developments in Central and Western China. It will bring widespread employment. It will bring high standards of living. It will change China from a weak to a strong nation. The Yangtze Gorge Project should be constructed for the benefit of China and the World at large.

—John Lucian Savage, 19442

A CLASSIC

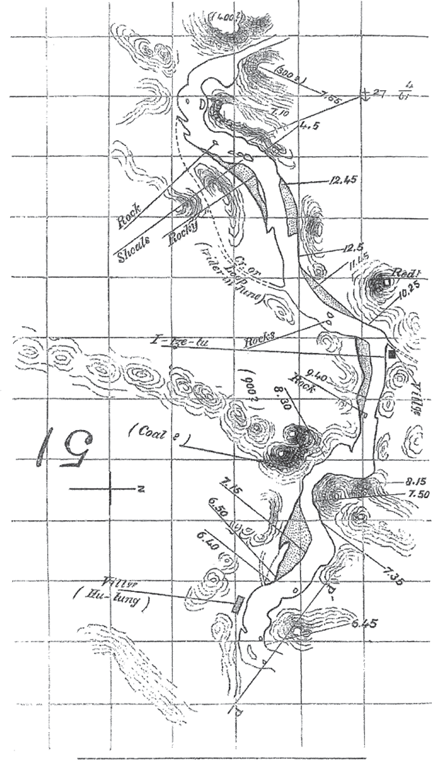

Mao Zedong’s vision of the damming of the Three Gorges in his poem “Swimming,” which closes chapter 2, is one of the most enduring elements of the modern mythology of the People’s Republic of China as developmental state. Soaring bridges and towering dams were part of a “grand plan” (hongtu 宏圖) of socialist construction that is still being implemented (albeit in radically expanded scope and ambition). Though tailored to the politics and aesthetics of the new state, Mao’s plan was deeply rooted in both the high modernist ideology he had inherited from early reformers, especially Sun Yat-sen, and in the even earlier scientific remapping of the Yangzi, which began in the mid-nineteenth century as part of an imperialist project to “open” China’s interior. The classical Chinese language that Mao uses in his poem obscures not only these imperial entanglements, but also what makes the Three Gorges Dam a “CLASSIC” expression of high modernist planning, as John Savage describes it in the second epigraph to this chapter. Chief design engineer of the American Bureau of Reclamation between 1924 and 1945, Savage was commissioned by Chiang Kai-shek toward the end of the Second World War to collaborate with Chinese engineers in producing a feasibility study for damming the Three Gorges (figure 3.1). For Savage, who oversaw the design of the Hoover, Shasta, and Grand Coulee dams, the “Yangtze Gorge Project” was a dream; massive in scale and far-reaching in impact, it promised to change China and the world forever.

FIGURE 3.1 A proposed dam design from John Savage’s Preliminary Report on the Yangtze Gorge Project (1944).

Savage, Sun, and Mao all followed in the footsteps of a long line of nineteenth- and twentieth-century travelers, scientists, and merchants who had fantasized about transforming China by mastering the Yangzi. To reconsider myths of the national origins of the dam project in relation to these earlier efforts to reconceptualize the river, Part II investigates a broad range of representational and material processes, including the systematic remapping of the landscape according to the metrics and optics of modern science and commerce—from geology and cartography to mining, shipping, tourism, and hydroelectric power generation; the reinscription of the Three Gorges as both a symbol of China’s status as modern nation state and a site for that state’s ongoing creation; and the projection of a set of “national characteristics” onto the people and places of the river. What is at stake in all of these processes is not simply the construction through representation of an imaginary “China” for Euro-American or Chinese audiences, but rather how imagination and reality interact to shape China’s “undeniable presence in the world that represents it.”3

The imaginative production of the Three Gorges as a national and cultural Chinese landscape began in the 1860s, when the first Western survey and travel account of the Upper Yangzi was produced. This attempt to reinscribe the landscape cartographically and textually marks the proximate (if not ultimate) horizon of possibility for the “undeniable presence” of the Three Gorges Dam. Much of my archive for this chapter consists of nonfiction English-language travel accounts, maps, and related visual materials produced between 1861 and the early 1930s by British subjects. The earliest of these materials appear just after the Chinese interior was forcibly opened to Western merchants and navies by the treaties that were signed in the wake of the “opium” wars. The latest come from the period when steam travel and shipping were regularized, fundamentally disrupting earlier technologies and ways of knowing, seeing, representing, and moving on the river.

Though I compare these sources to important Chinese maps and route guides from the same period, I have dedicated much of this chapter to the British because they were the earliest and most systematic Western explorers of the Yangzi Valley, a region that came to be seen by the end of the nineteenth century as a British “sphere of influence.” As a result, there is a body of highly intertextual British travel accounts and surveys that is mostly untouched by the rich Yangzi lore I introduced in Part I. It is in these and related sources that the river and the Three Gorges were first conceptualized not as a landscape of historical traces or important cultural sites, but as a national landscape integral to the economic and political development of the modern Chinese state. That this newly “Chinese” landscape often functioned in Western accounts as a symbol of eastern stagnation does not change the fact that the region was seen as a prospect for modernization. Mao and Jiang Zemin would eventually blend the mythopoetic and technological in their celebration of the Three Gorges Dam project, but the Chineseness of the landscape was first articulated in very different terms.

Despite the ambitions of the British, the “opening” of the Yangzi was by no means a one-sided affair, and the story I tell here is not of Western imperialists dominating passive Chinese. British travelogues, navigational guides, and photographs bear traces of an unequal and exploitative but also collaborative and competitive process whereby the Yangzi was reinscribed as an object of economic and national development. Westerners exploited Chinese knowledge of the river, but the new technologies and spatial ideas they introduced were soon adopted by both the Qing and Republican governments and Chinese merchants as part of a nationalist project to establish Chinese control over shipping. Chinese and Western forces were never equally matched during this period, but to assert a rigid distinction between Western imperialism and its Chinese object is to miss the “patchwork nature [and]…improvisational aspects” of China’s modernity.4

The materials I explore in this and the next chapter are an integral part of the history of the Three Gorges Dam as a project that is simultaneously imperial and sovereign, international and national, aesthetic and material. They force us to confront the collaborative (rather than collaborationist) aspects of imperialism as well as the deep bonds between European imperial power and the “ ‘imperial’ view of nature” that underlies certain forms of national development.5 In this chapter and the next, I approach these aspects of the history of the Three Gorges from two interrelated perspectives—the production of Chinese landscape and Chinese bodies. By tracing two histories of the Three Gorges and the Yangzi between the 1860s and 1930s, I show not only how Western ideas about landscape and labor interacted with a burgeoning discourse of Chinese nationhood to produce the Three Gorges as a Chinese landscape, but also how such ideas came to support the technological capture of the Yangzi as a natural resource—a source of energy “that can be extracted without limit and used without depletion.”

TO REALIZE CHINA

With the establishment of the lower Yangzi city of Chinkiang (modern Zhenjiang) as a treaty port in 1858, the Qing Dynasty and its European counterparts launched a process that would forever change the Yangzi and the Chinese interior.6 The travel narratives, scientific surveys, drawings, photographs, and maps that travelers produced soon after they gained access to the interior strove to make Yangzi River landscapes legible and visible according to a set of universal standards. This had a number of effects. First, by collecting and disseminating information about rapids, currents, and seasonal variations in water level, these writers diminished the dangers of the river as well as the power of local and often oral forms of knowledge that had previously been used to negotiate them, preparing the way for the introduction of steamships around the turn of the twentieth century. Steam travel, which was carefully controlled by the Qing government and quickly adopted by Chinese merchants, further challenged earlier ways of knowing and moving on the Yangzi, beginning its transformation from a space defined by long-standing patterns of use and representation to what Richard White has described as an “organic machine,” a techno-landscape engineered for maximal control.7

Second, by remapping the Yangzi according to supposedly “universal” scientific standards, early European travelers worked to insert China into a world system in which any one place could be compared to another. Insistence on commensurability helped foster a view of China beyond the Qing, sometimes as a colonial prospect and sometimes as a nascent (if ineffectual) nation-state. The Qing was similarly concerned with establishing its sovereignty in universal terms. Shellen Xiao Wu argues that the use of Zhongguo 中國 (China) in place of Da Qingguo 大清國 (The Great Qing State) in 1902 mining regulations parallels a shift in the conception of natural resources from a means of supporting the welfare of the population to a material possession of the sovereign nation, which monopolized all rights of access and development.8 For Western writers, however, straightforward comparison based on universal standards was complicated by continued attempts to account for Chinese racial difference, which was often framed as a difference in “national character,” a topic I discuss in the next chapter. It is in the space between the production of a standardized China and the belief in Chinese difference that two interdependent and still active modes of “Chinese landscape” came to maturity. As ways of conceiving, visualizing, and mastering the Yangzi and its Gorges, these modes—one developmental, the other fantastic—perform an important division of labor.

The developmental mode approaches landscape as a physical stretch of land made legible through scientific surveys, mapmaking, military reports, and travel writing. It helps produce not only a geographical landscape primed for territorial and commercial conquest, but also a national landscape in need of development. The fantastic mode treats landscape as an aesthetic or symbolic form, a reservoir of Chinese difference and a figure for the romance of travel. Though no less symbolic than the second, the first is based in an objectivist ideology that demands complete faith in the realism of its representational modes. If the rationalized Chinese landscape is the product of processes of knowledge production that represent the Yangzi in order to transform it, the fantastic Chinese landscape serves as an alibi for that process by proclaiming the enduring Chineseness—however and by whomever it might be defined—of the river. The fantastic landscape lends both imperial and national projects an affective power that can be channeled through poetry, landscape art, touristic imagery, and other forms. Though distinct and even superficially antithetical, these modes of “Chinese landscape” are complementary manifestations of a single process of producing and “opening” the Chinese interior. If one looks carefully enough, it is easy to discern the geometric logic of the chart in even the most scenic of prospects.

⋆

When the Three Gorges made their first impact on what Mary Louise Pratt calls European “planetary consciousness” in the 1860s, they were seen as the greatest obstacle to the opening of Sichuan, a region admired for having avoided the faults of more accessible provinces.9 Its people were considered friendlier, its land richer and better administered, and its opportunities for trade far greater than in coastal regions. It maintained, in short, a hint of the utopian aura that had surrounded China in early modern Europe.10 To access (and remove the commodities of) the commercial utopia of Sichuan, however, one had to pass through the treacherous Yangzi gorges, a landscape that was both forbidding and awe-inspiring, as it appears in the frontispiece to Thomas Wright Blakiston’s 1862 travel account, Five Months on the Yang-tsze.11 The image shown in figure 3.2, with its geological strata and towering cliffs, is simultaneously a rebuke to fantastic ideas about China’s landscape, a call for a generalized scientific understanding of the world, a reminder of the physical obstacles that isolated Sichuan, and an early expression of a discourse of adventure and grandeur that grew up around the Three Gorges.

FIGURE 3.2 Frontispiece to Five Months on the Yang-tsze (1862); etching based on a sketch by Thomas Blakiston’s travel companion, Alfred Barton. The small Western figure in the foreground sketching the gorge informs readers at the outset that Blakiston’s book and the images it contains were based on personal observation carried out on the ground. Note the two Chinese onlookers to the right of the artist.

It was in the interest of penetrating this landscape and developing the Chinese interior that Blakiston, a British military officer, led one of the earliest trips by a foreigner through the Gorges into Sichuan in 1861. As the progenitor of the English-language genre of Three Gorges travel accounts, Blakiston’s narrative not only laid the foundation for the production of the Yangzi as national Chinese landscape, it also inspired an enduring vision of the Three Gorges as a land of wonder. Blakiston and his companions began their journey at Shanghai as part of the British military flotilla that inaugurated new navigational and commercial rights established by the 1860 expansion of the 1858 Tianjin Treaty. The Royal Navy went only as far as Hankou, but Blakiston had more ambitious plans—to travel along the Yangzi “through China, thence into Tibet, and across the Himalayas into North-western India.”12 His plan to explore beyond the newly opened treaty ports was made possible by a clause in the Tianjin Treaty that allowed for the establishment of an overland trade route between India and China. Rebellions along the route to Chengdu made Blakiston’s journey impossible, but the prospect of linking British South Asia and China would continue to draw British adventurers, including Augustus Margery, whose 1875 murder in Yunnan resulted in the Chefoo Convention treaty, which hastened the development of British trade on the Yangzi. Though Blakiston did not complete his journey, he succeeded in navigating farther up the Yangzi—some 1,600 miles—than any other Englishman.

Blakiston’s stated goal of “open[ing]the Yang-tsze Kiang to foreign trade” makes him a direct forerunner of more commercially oriented travelers. Perhaps his greatest contribution to the development of the river, however, was in carrying out the first modern scientific survey of the Upper Yangzi, the portion of the river extending west from Yichang through the Three Gorges and up to the confluence of the Yangzi and the Min River, which led north to Chengdu. The luggage that his Chinese crew carried included a small collection of scientific instruments: “an eight-inch sextant and artificial horizon, prismatic compass, pocket compasses, and thermometers, together with a couple of aneroid barometers furnished by gentlemen in Shanghai, [and] telescopes and binoculars.”13 Blakiston used these devices to keep careful geographical, geological, meteorological, and hydrological records, measure distances for the production of a map, and keep a detailed field-book that marked, among other things, navigational hazards, depth soundings, topographical features, coal deposits, villages, and other landmarks.14

According to Blakiston, one purpose of his narrative and visual account of the Yangzi was to sweep away inaccurate conceptions of China back home. Coming late to the European pastime of representing the “Orient,” he struggled against tenaciously picturesque ideas of the Chinese landscape. In his introduction to the city of Wan (now Wanzhou), he calls on his readers to “cast [off] the ‘willow pattern,’” and rails against “preconceived notions of China, as derived from geographies; where it is represented as one immense fertile plain…in which golden-pheasants innumerable nestle…where porcelain pagodas and high-arched bridges meet the eye at every turn.”15 For Victorians, the fantastical China of mass-produced willowware porcelain, which loosely imitated earlier Chinese import ware, was ubiquitous. In the example shown in figure 3.3, two highly repetitive and involuted borders surround a dense garden scene of pagodas, an arched bridge, and stylized trees. The only empty space on the dish lies between these borders and in portions of the image corresponding to air or water. This is a landscape outside of time and space, an object of contemplation accessible only by passing through its two fantastical frames. The viewer is drawn not so much into the image as toward a fixed, flat tableau in which the same frozen scene unfolds, a European emblem of Chinese timelessness—China as china.16

FIGURE 3.3 The “willow pattern.”

Source: Wikimedia Commons

It is not simply the fantastical nature of this “ ‘fertile valley’ notion, and…‘willow pattern’” landscape that disturbs Blakiston, but the failure to understand that geography is a universal rather than a particular phenomenon, though this must be taken on faith: “We must believe in mountains, in inland seas, and all the usual physical features of other parts of the world…before we can even begin to realize China” (emphasis added).17 In the midst of this call to cast aside one’s illusions of China, to see it as commensurate with the rest of the world (and open to the same forms of knowledge), Blakiston both advocates a leap of faith (“we must believe”) and suggests that this landscape of “physical features” is yet to be realized. For Blakiston and those who followed him, to “realize” China is not simply to understand it fully or to correct misconceptions about it, but to make what is popularly conceived in fantastic terms real. It is also to make money from it and even, potentially, to possess it as a form of colonial real estate. The semantic range of “realize” illuminates the intimate connections between knowledge, fantasy, economics, and imperial force that underlay the British contribution to the production of the Yangzi as Chinese landscape.

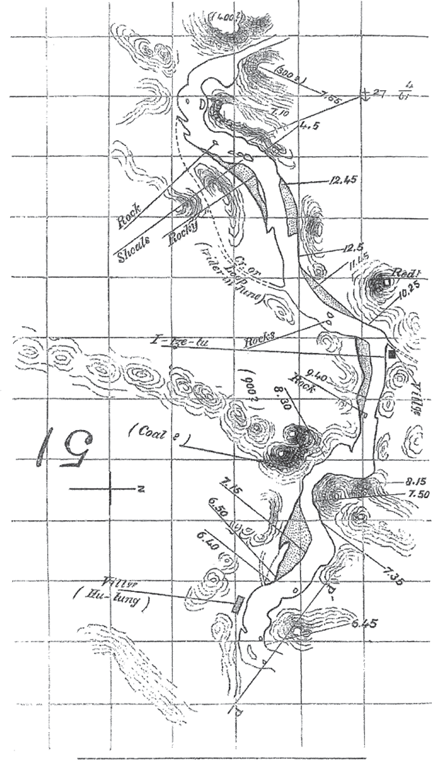

As an officer in the Royal Artillery, Blakiston was trained at the Royal Military Academy in basic methods of surveying and mapmaking, skills essential to managing the logistics of warfare and colonial occupation. These are the same skills that helped maintain what James Hevia has described as a British imperial “information system…designed to command and control the space of Asia.”18 One of Blakiston’s greatest contributions to this information system are the charts of the river he produced. Though Chinese painters and mapmakers had been producing images of the river for centuries, Blakiston’s survey yielded the most mathematically precise inscription of the Yangzi above Hankou that had ever been produced. The layout of his book reinforces the importance of mapmaking to his project: its final numbered page consists of an image of a river chart taken from his field-book (figure 3.4), and the book ends with a foldout map of the Upper Yangzi. Together with the frontispiece, these maps form a visual frame that marks the starting and ending points of a symbolic narrative that runs parallel to his textual one. From a sublimely forbidding gorge to a gridded river chart, Blakiston’s book fixes this unfamiliar landscape as visual and material prospect. While this design suggests a passage through an awe-inspiring, albeit objectively rendered, landscape to a cartographically ordered space, the drama of the intervening travel narrative reminds us that the latter is contingent on the former, that there is an affective and aesthetic undercurrent to Blakiston’s universal geography.

FIGURE 3.4 A “specimen page” of Blakiston’s field book; published as an appendix to Five Months on the Yang-tsze. Note the label “Coal?” that appears to the left, just below center.

The type of precision mapping that Blakiston practiced aimed not only to inscribe the Yangzi and its dangers graphically—no easy task given its length and enormous seasonal variability—but also to situate the river in hierarchical relation to other nations using the global locational system of longitude and latitude, the latter measured “from Greenwich.” Only the careful remapping and representation of the Chinese landscape based on firsthand observation could establish China’s status as a geographical entity like any other nation, overturning earlier fantastic visions and the “geographies” that generated them. Blakiston sought to achieve this with an assiduity bordering on the obsessive. The work of collecting data so preoccupied him toward the end of his trip that he had nightmares about being “tied down” so that he “could not get out to take the times and bearings” or losing the field-book in which he constantly traced the river. Time and again, he explains, he awoke suddenly in the middle of the night to carry out his tasks, only to find “not a sign of morning in the eastern sky.”19

Blakiston’s anxieties notwithstanding, he attributes his health throughout the trip to the rigors of the journey and the constancy of his labors: “I do not know how many half-sleepless nights I endured…but this I know, that, had I been living luxuriously…I should have been prostrated by fever long before the work could have been accomplished.”20 Despite his narrative of British fortitude, the success of Blakiston’s intellectual labor was in fact dependent on the physical labor of others. These included the “Seikhs,” who guarded the four “Europeans” (one of whom was American) from a sometimes very hostile population, as well as the trackers and the boat’s other Chinese crewmembers. It is in the relationship between these racially divided modes of labor that one can discern the careful institution of what Pratt describes as a “secular, global labor that, among other things, made contact zones sites of intellectual as well as manual labor, and installed there the distinction between the two.”21

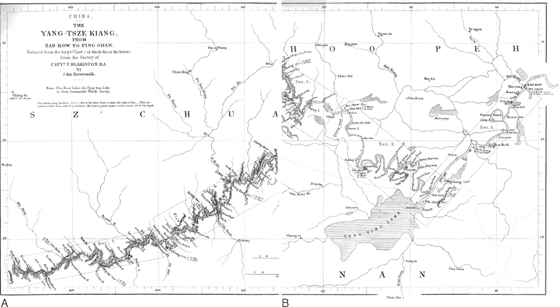

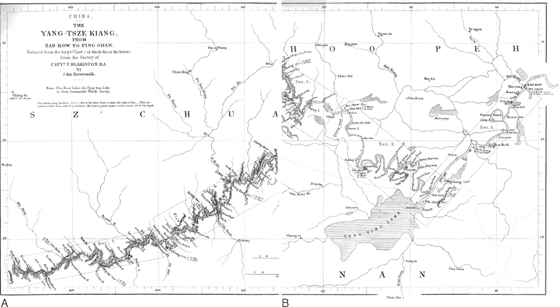

Working in a state between hallucination and obsession made possible by the labor of his crew, Blakiston collected material for the creation of a detailed chart of the Yangzi from Hankou (modern Wuhan) to Pingshan. The full-size version, which was produced by the London mapmaker John Arrowsmith, consists of seven separate two-page sections and includes information regarding “the nature of the banks, the shoals, rocks, and country adjoining the river.”22 The smaller “Index” chart represents the entire stretch of the Upper Yangzi in one sheet and was included as a foldout map at the end of Five Months on the Yang-tsze (figure 3.5). If Blakiston’s narrative plots the diachronic experience of moving through space over time, Arrowsmith’s map frames the Upper Yangzi synchronically, realizing it as a single prospect. It flattens both the human and natural landscapes into a series of “divisible segments” that were “optically consistent” with other forms of representation.23 Consistency allowed for comparison and cross-referencing, but it also had important logistical functions. By linking together Britain and its imperial prospects, universal geographic and cartographic systems facilitated the predictable movement of people, goods, resources, and military bodies across the globe.

FIGURE 3.5 The first (A) and last (B) sections of the “The Yang-Tsze Kiang from Han-Kow to Ping-Shan.” This index chart was produced by John Arrowsmith based on Blakiston’s survey.

Arrowsmith’s chart conveys this sense of movement in a number of ways. First, by tracing the sequence of place names (some coined by Blakiston) along the river, the viewer can journey virtually. Unlike narrative accounts, which tend to emphasize the episodic difficulties of travel and the danger of the river, the virtual journey is effortless and continuous. Later modifications of the river can be understood partly as an attempt to render the physical journey as close to the seamless virtual journey as possible. To fix the river inscriptionally is to begin the process of fixing it materially. Second, in the near absence of information beyond the river, the rectangular frames that provide coordinates and form a regular grid take on a temporal quality, the minutes and seconds of latitude and longitude beating out a steady tattoo for surveys and journeys to come. The spatial and temporal regularity of the map is disturbed only by the cities and rivers that break through the outer frame, as well as by the Yangzi itself, which flows east past present-day Wuhan, almost to the edge of the page (figure 3.6).

FIGURE 3.6 Arrowsmith index chart (detail) showing the Yangzi flowing east through the frame. Note the English names that Blakiston has given to landmarks and other topographical features.

These breaks link the rationalized territory of the chart to both the nation that surrounds it and the globe that contains it. They also imbue it with a dynamism that neither frame nor page can contain. The sense of free movement and spatial control offered by Blakiston’s narrative and map was powerful, even if, in the 1860s, mastery over the Yangzi remained mostly aspirational. Though travelers like Blakiston were not directly engaged in territorial conquest, by the turn of the century they were part of a global debate on “spheres of interest,” which some considered a step in the partition of China. Typically more economic than administrative, spheres of interest were conceived to give individual European nations and Japan a large measure of control over development in specific regions. The English staked claim to the entirety of the Yangzi Valley, “an area of 600,000 square miles inhabited by about 18,000,000 of the most industrious and peaceable people in the world.”24 “If Chinese partition is inevitable,” as an American reviewer of Archibald Little’s 1888 Yangzi travelogue, Through the Yang-tse Gorges: Or, Trade and Travel in Western China, writes, “this is the portion which Great Britain would demand as her share of the spoils.”25 Chinese partition was not inevitable, but Britain’s territorial ambitions—as boldly outlined on the cover of Little’s book (figure 3.7)—helped drive the textual and graphic reinscription of the Upper Yangzi as imperial prospect and modern Chinese landscape.

FIGURE 3.7 Cover of Archibald Little’s Through the Yangtse Gorges (1888) with the “British Sphere” outlined in red. See also color plate 6.

If Blakiston launched the reinscription of the Upper Yangzi, Archibald Little’s efforts to promote steam travel on the Yangzi over the last two decades of the nineteenth century greatly advanced it. In both cases, their contributions to the spatial production of the region were grounded in the sequence of “unequal treaties” signed by the Qing and foreign powers. While the 1858 Treaty of Tianjin made possible Blakiston’s exploratory survey, it was not until 1876, with the signing of the Cheefoo Convention between the British and the Qing, that a path was opened for direct foreign access to Sichuan.26 In addition to opening Yichang, eastern gateway to the Gorges and a major economic center, as a treaty port, section III of the Convention stipulated that “British merchants will not be allowed to reside at Ch’ung K’ing, or to open establishments or warehouses there, so long as no steamers have access to the port. When steamers have succeeded in ascending the river so far, further arrangements can be taken into consideration.”27 Supplementary articles added to the treaty in 1890 weakened this condition, proclaiming that Chongqing was to “forthwith be declared open to trade on the same footing as any other Treaty Port” (this happened in 1891), though it limited British merchants to the use of Chinese boats between Yichang and Chongqing and further stipulated that British steamships could access Chongqing only once Chinese-owned steamers had achieved the same feat.28

The Chinese government was well aware that the introduction of steamships on the Upper Yangzi as far as Chongqing represented the final stage in the opening of the river to foreign merchants and navies.29 Despite attempts to control this process through the introduction of various conditions in the treaties they signed, it was only a matter of time before maritime technology caught up with the economic and political desires of the British.30 In 1898, Little, who had actively lobbied to make an experimental steamer journey up the Yangzi as early as the 1880s, succeeded in navigating the Chinese-owned steamer Leechuan (Lichuan 利川) between Yichang and Chongqing.31 Two years later, another Englishman, Cornell Plant, piloted Little’s new steamship, Pioneer, through the Gorges, finally meeting the conditions laid out in the Cheefoo Convention’s supplementary articles.32

When the Leechuan powered through the Gorges in 1898, it loosened (without fully breaking) the ties binding travel and trade to the wide seasonal fluctuations and the forms of labor and technology that had defined life on the river for millennia. The successful navigation of the Gorges in steamships still depended on the expertise of Chinese pilots, but it was made possible by the kinds of spatial knowledge disseminated in Blakiston’s and Plant’s charts. As graphic inscriptions of nature scientifically ordered, these charts allowed the traveler to plot a course in the real world, imposing on the flux of the river fixed routes and anchorages. Though designed to help travelers negotiate and not change the river, they were far more than representations; by fixing the Yangzi as inscription, they aimed to fix some of the many geographical and hydrological problems that hampered “free trade.” Steamships did not simply master the river, leaving its obstacles unchanged; they transformed the cities of the Yangzi into “nodes in a dynamic transport system,” and made demands on its spatial organization (the demolition of reefs and other large obstacles as well as the construction of docks and treaty port settlements) that were only fully met with the construction of the Three Gorges Dam, a key function of which is to allow oceangoing vessels access to Chongqing.33

There is, to be sure, a much longer history of physical changes made to the banks and bed of the Yangzi in the Three Gorges region. Nanny Kim, for example, has written about a philanthropic project carried out by two Hankou (modern Wuhan) merchants after they were nearly drowned in the Ox Mouth Rapids (Niukou tan 牛口灘) in 1804.34 These men and their descendants sponsored not only the repair of the paths used by “trackers” but also the clearing of erosion debris and the removal of “massive amounts of solid rock” in especially dangerous sections of the Gorges.35 At least two things distinguish these improvement projects from later attempts to develop the Yangzi, however: First, whereas later projects, such as the dynamiting of large rocks that began in 1889 and became systematic between the 1930s and 1970s,36 made permanent changes to the river, earlier projects were often erased by it fairly quickly.37 Second, if the primary goal of nineteenth-century philanthropic projects was to make travel and trade safer for local residents and regional travelers, later changes to the region were part of an effort to integrate the Yangzi into a national and international transportation and commercial system. It is the reinscription of the Yangzi and its Gorges as Chinese landscapes that can be compared to other national landscapes that makes possible not only physical changes that facilitate shipping but also the eventual development of the river into a source of power.

DISPLACING KNOWLEDGE

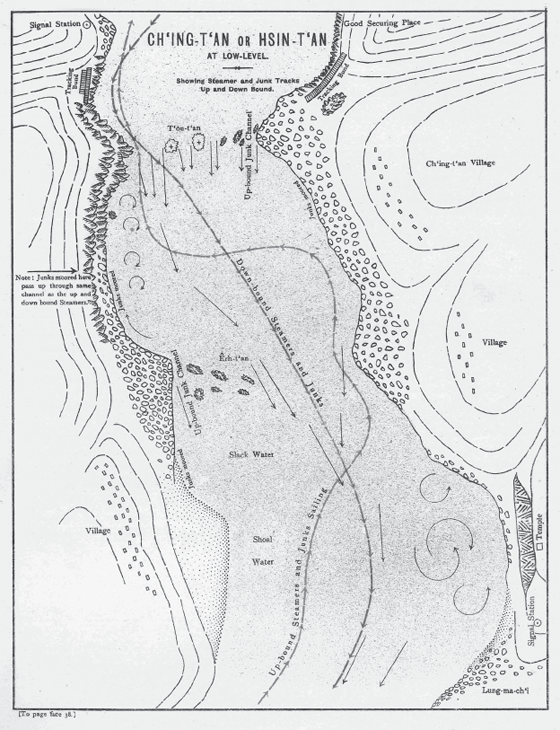

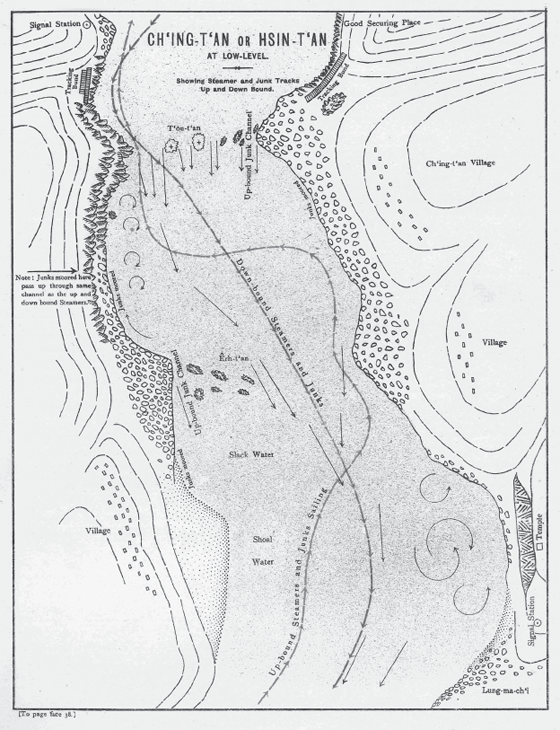

Blakiston’s efforts to “realize” China introduced forms of spatial knowledge that forever changed how Westerners and Chinese saw and moved along the Yangzi. In the nearly four decades between his 1861 journey and the successful introduction of steamships on the Yangzi, the British—as well as the French, Americans, Japanese, and Chinese—continued to reinscribe the river textually and visually, while also reshaping it physically.38 What began as part of an attempt to situate the river in relation to the nation and the world that contained it took on an increasingly fine-grained quality in the construction of a string of treaty ports between Shanghai and Chongqing, the creation of ever more detailed charts of the river, and eventually the construction of a network of signal stations and lighthouses that managed river traffic. By 1920, nearly sixty years after Blakiston’s journey, Western knowledge of the river extended to its seasonal and historical variations in flood level, its currents, its whirlpools, and the individual rocks and rapids that made travel so dangerous. The throroughness of such knowledge is evident in a plate from Cornell Plant’s Handbook for the Guidance of Shipmasters on the Ichang-Chungking Section of the Yangtze River (1920), a publication of the Chinese Maritime Customs (figure 3.8).

FIGURE 3.8 A plate from Cornell Plant’s Handbook showing routes for steamships through the Xintan 新灘 or “New Rapid.” It was in the village of Xintan that a monument to Plant was erected after his death and subsequently shifted to make way for the Three Gorges Dam reservoir (see chapter 1). Note the signal stations in the upper left and lower right corners, as well as the “tracking bunds” near the top of the plate. The latter were built to provide trackers with level paths for towing boats over the rapids. See also color plate 7.

Plant was one of the most important figures in the reinscription of the Yangzi. A well-respected ship captain, he worked in the employ of both the Chinese Sichuan Yangzi Steam Navigation Company (Chuanjiang lunchuan gongsi 川江輪船公司) and the French navy between 1898 and 1915, when he was appointed the first river inspector of the Chinese Maritime Customs, an organ of the Qing government that was staffed by a combined Chinese and international bureaucracy, with British subjects dominating the upper levels.39 Founded in 1854 to assess customs on maritime trade, its responsibilities gradually expanded to include the collection and publication in English and Chinese of information related to trade, weather, navigation, and a wide variety of other topics. Produced by a Qing governmental organization but for a combined Chinese and “foreign” audience, this body of material constitutes perhaps the best-developed “information system” centered on China’s coasts and rivers in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Part guide to the Yangzi and part tool for its commercial capture, Plant’s Handbook was conceived of not only as an aid to Western navigators but also as a tool for ending their reliance on Chinese pilots:

The study of it, it is hoped, will be most useful in assisting the master to learn the ropes quickly and thus not leave him so long entirely in the hands of the Chinese pilot, a situation which has been very keenly felt since the advent of steamers on the river and is a constant menace not only to the reputation of the master himself but to the best interests of his owners, to say nothing of lives and property on board.40

Described as a menace to life and property, the Chinese pilot embodied an imbalance of power unacceptable to Western ship captains and owners. Despite advances in the mapping of the Yangzi, in 1920 most steamships could not function without local Chinese knowledge (navigational and linguistic) when confronting the dangers of the Three Gorges.41 Plant’s goal of making Chinese pilots unnecessary was still unmet a decade after the first edition of his Handbook was published. According to the Shanghai-based journalist H. G. W. Woodhead, writing in 1931, “piloting…[was still] entirely in the hands of the Chinese. The pilots serve an apprenticeship of six or seven years and usually have had considerable practical experience as helmsman of junks. They have no theoretical knowledge of navigation, never look at a compass, and could not take a cross bearing. But they are able to read underwater conditions from the appearance of the surface with almost uncanny accuracy.”42

Drawing on more than two decades of experience on the Upper Yangzi, Cornell Plant sought to render the uncanny skills of the Chinese pilot unnecessary by producing a comprehensive visual and textual guide to the river. The publication of his Handbook roughly coincided with a shift in the balance of power on the river, from Chinese-owned (and government-backed) companies often employing Western steamship captains, which dominated trade between the late 1890s and early 1920s, to a more mixed configuration of competing Western and Chinese shipping concerns.43 That Plant’s Handbook, a Chinese government publication, was designed to benefit Western ship captains and merchants might seem strange in this context, but his actions were not necessarily contrary to Chinese interests. As Thongchai Winichakul argues in his classic study of cartography and the modern Thai state, it is the displacement of indigenous spatial knowledge—often by the state and its agents—that “has in effect produced social institutions and practices that created nationhood.”44 Plant’s Handbook was designed to benefit Western ship captains and merchants, but it also helped fix the river in its broader national and international contexts. By creating charts that could be used by anyone with the proper training, Plant contributed to the reinscription of the Yangzi as part of a modern China that could be conceived of as both a semicolonial trading partner and a homeland. The Chinese development of the Yangzi over the last century is at least partly an extension of a Western imperial project that was simultaneously improvised, contested, and collaborative, even as it was based in an imbalance of power.

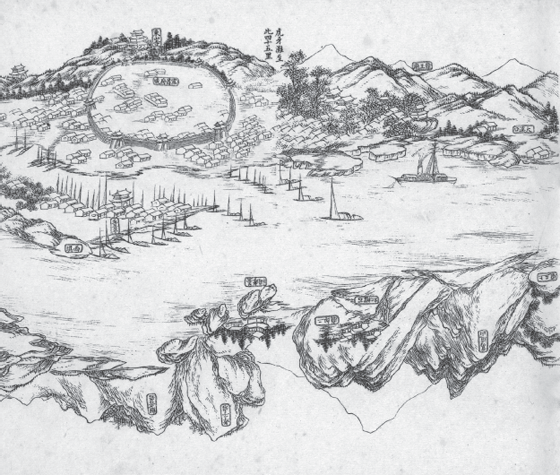

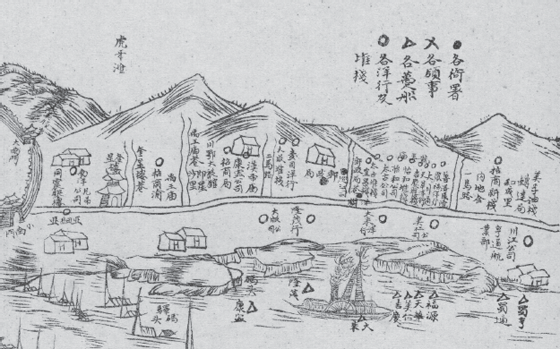

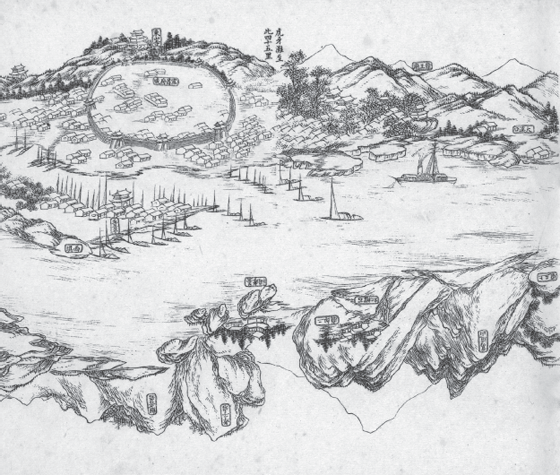

If Plant’s Handbook was designed to benefit Western merchants, it also serves as a reminder that Western efforts to reinscribe the Yangzi textually and physically would have been impossible without the “uncanny” (i.e., local, oral, embodied) knowledge of the Chinese pilots who knew the river so well, not to mention the countless Chinese officials and merchants who employed them as well as the river trackers who pulled boats over the most difficult rapids in the Gorges. There is evidence, for example, that foreign travelers made extensive use of the 1883 route guide, Xingchuan biyao 行川必要 (Essential Guide to Traveling in Sichuan), and its accompanying chart, Xiajiang tukao 峽江圖考 (A Critical Chart of the Yangzi Gorges), both of which were produced by the Qing official Luo Jinshen 羅縉紳 (figure 3.9).45 Luo’s Essential Guide and Critical Chart include information from gazetteers, poetry, and other textual sources as well as folk sayings and oral knowledge gleaned from Yangzi boatmen.46 Together, they constitute only one example of a number of combined guides and charts of the Upper Yangzi produced by Chinese officials, merchants, and cartographers between the early 1880s and the mid-1920s, the period during which steamship navigation on the river was first conceived, inaugurated, and finally regularized as a multinational enterprise.47

FIGURE 3.9 This section of Luo Jinshen’s Critical Chart of the Yangzi Gorges (Xiajiang tukao 峽江圖考; 1883) depicts Yichang, just east of the Gorges.

Though they were intended as practical navigational guides, these new charts draw on many of the same premodern geographical and cultural sources that are inscribed on both the The Shu River, which I discussed in chapter 2, and the closely related Changjiang wanli tu 長江萬里圖 (10,000 li of the Yangzi River) painting tradition.48 As in The Shu River, blank spaces on these maps are often inscribed with excerpts from gazetteers or other geographical works, poems, and folk sayings, as well as information about navigational dangers and distances between major settlements. Despite their incorporation of “traditional” Chinese mapmaking techniques—particularly in their placement of text and their pictorial landscape style—these Qing and early Republican charts are nonetheless marked by traces of the kinds of spatial knowledge and technology that Western mapmakers deployed in their reinscription of the river.

By the 1920s, Chinese map and guide makers were well schooled in the most up-to-date methods used by Western cartographers and were eager to deploy them for both commercial and nationalistic purposes. In one 1923 work, a patriotic editor borrowed portions of Plant’s Handbook (without attribution) and included them within a navigational guide that drew on older pictorial mapping techniques (see below). In a publication from 1920, a team of Chinese surveyors produced a guide to the river’s obstacles that also borrows from Plant but frequently surpasses him in detail and scope.49 Plant’s Handbook was deeply indebted to the forms of knowledge that it sought to displace, but it also provided raw materials essential to the Chinese reinscription of the river. Such acts of appropriation mark an important transition in the production of the modern Yangzi—from a Chinese river scientifically fixed as an imperial and commercial prospect to a Chinese river reinscribed as part of a sovereign nation.

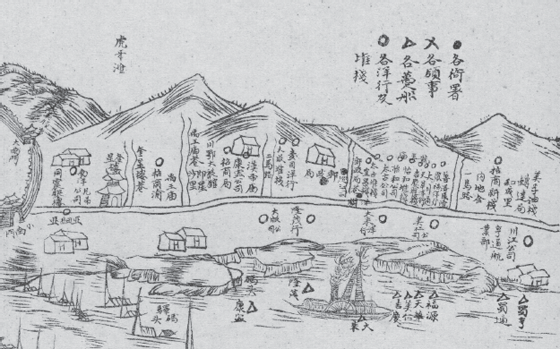

These processes of appropriation and adaptation are evident in the evolution of a group of closely related charts and navigational guides that drew, as did many British texts, on Luo Jinshen’s 1883 Essential Guide and Critical Chart. The earliest of these, the Xiajiang tukao 峽江圖考 (A Critical Chart of the Yangzi Gorges), shares a title with Luo’s chart. Though it was compiled by the Qing official Guo Zhang 國璋 (dates unknown) in 1889, it does not seem to have been published until 1901.50 According to the preface to his chart, Guo Zhang combined, amended, and expanded three earlier charts (including Luo’s), each of which covered a series of shorter stretches of the river. Unlike Luo’s chart, Guo Zhang’s Critical Chart (figure 3.10) adopts an orientation sometimes found in official charts and topographical images: For journeys upriver (east to west), one opens the book from the title page and follows the normal right to left orientation of premodern Chinese texts. For journeys downriver, one flips the book upside down and reads it in reverse (though still from right to left). Regardless of the direction of the journey, the bank on the “bottom” of the chart appears upside down. Designed to give equal prominence to the course of the river as well as its southern and northern banks, this “opposed scene” (duijing 對景) format depicts the river and its obstacles from overhead while representing each bank from an angle that maximizes detail while also leaving space for the printed annotations that are so central to this type of chart.

FIGURE 3.10 Yichang and its environs from Guo Zhang’s Essential Reading for Sichuan Travels: A Critical Chart of the Yangzi Gorges (Chuanxing bidu xiajiang tukao 川行必讀峽江圖考; undated [1901?] but identical to the 1916, 1919, and 1926 editions). Note the upside-down landscape at the bottom of the page. Though more detailed than Luo Jinshen’s Essential Guide, this map still depicts Yichang and its environs using a stylistically generic landscape scene.

By contrast, the woodblock images in Luo’s 1883 Critical Chart (see figure 3.9) render the river’s southern bank little more than a foreground frame for its depiction of the northern bank and the river, which occupies an extended vertical field. These differences can be attributed at least partly to the different functions of the charts. Luo’s chart was produced to accompany a text that promoted the workings of a philanthropic lifeboat system with roots stretching back to the early Qing.51 Because it predates the introduction of steamships on the river, it is geared toward junk traffic and the organizations and physical infrastructure that supported it. While Guo Zhang’s Critical Chart contains much of the same visual and textual information, it was designed first and foremost as a navigational guide for merchant shipping at a time when steamers were being introduced to the Three Gorges region. It is in Guo Zhang’s chart that one first finds small traces of the new technology of steamships and the spatial demands they made on the region. Mapmakers continued to reproduce Guo Zhang’s Critical Chart through the 1920s, though as steamships became more common and their impact on the Upper Yangzi more pronounced, they altered its basic template to reflect changing spatial and political realities. A comparison of the undated version of the Critical Chart (figure 3.10) with an adaptation of it contained in the 1923 Zuixin chuanjiang tushuo jicheng 最新川江圖說集成 (Updated Compendium of Illustrated Guides to the Yangzi in Sichuan) (figure 3.11) shows how the latter was rearranged to reflect these new realities.52

FIGURE 3.11 Yichang and its environs as depicted in the Updated Compendium of Illustrated Guides to the Yangzi in Sichuan (Zuixin chuanjiang tushuo jicheng 最新川江圖說集成; 1923). In this image, the landscape east of Yichang’s walls has been replaced by a street map with detailed labels.

The chart contained in the 1923 Updated Compendium, which also bears the English title Guide to the Upper Yangtze River, Ichang-Chungking Section, is borrowed directly from Guo Zhang’s Critical Chart, but with two changes. The lithographic plates for the starting and ending points for journeys on the Upper Yangzi—Yichang and Chongqing—have been significantly altered. In all editions of the Critical Chart (figure 3.10), the northern bank of the river leading up to the city walls of Yichang is depicted as a landscape of rock formations, trees, and other foliage as well a walled pagoda and other timbered structures. In the Updated Compendium (figure 3.11), however, the engraver has replaced the trees, temples, and low hills closest to Yichang with a crudely drawn map of a street running parallel to the river and smaller streets running north from it, up the sides of low hills.

The names and locations of official offices, foreign consulates, pontoons for mooring boats (dunchuan 躉船), and foreign and Chinese shipping firms are printed along the road and the banks of the river. A previous owner has added a key to the map in blue ink as well as additional labels, including one for the American consulate, which is located just beyond the easternmost of the city’s gates (figure 3.12, far left). That both this chart and the various versions of the Critical Chart from which it has been adapted include a paddle steamer belching smoke by the river’s northern bank suggests that steam technology had become a familiar component of the landscape, at least in Yichang, as early as 1901. It is only the “updated” 1923 edition, however, that fully depicts changes in the spatial organization of the river and its ports necessitated by this technology. By altering Guo Zhang’s Critical Chart to highlight the well-developed infrastructure of steam shipping and international trade, the producers of the Updated Compendium addressed an audience that included merchants and officials directly engaged with (or concerned about) foreign shipping firms and steamships.

FIGURE 3.12 Updated Compendium (1923) chart (detail). The landscape that comprises the lead-up to Yichang in Guo Zhang’s Critical Chart has been replaced here with a crudely drawn street map. Note the addition of a symbol key in blue ink: open circles mark foreign shipping concerns, triangles mark pontoon docks, X’s mark consular offices, and closed circles mark government offices. The Chinese-owned Sichuan Yangzi Steam Navigation Company is labeled at far right as Chuanjiang gongsi 川江公司. At far left, the American consulate (Mei lingshi 美領事) is marked with an X. See also color plate 8.

Compiled by Yang Baoshan 楊寶珊, one of the founders of the Chinese Sichuan Yangzi Steam Navigation Company, which employed Cornell Plant starting in 1908, the Updated Compendium introduces a number of additional features beyond its alteration of the plates depicting Yichang and Chongqing.53 These include a preface that provides a history of the introduction of steamships on the Yangzi (in which Little and Plant figure extensively) as well as two large foldout pages. The first of these is a map of the Upper Yangzi produced using “naval surveying techniques” (haijun celiangfa 海軍測量法) but in reality copied directly from Plant’s Handbook (place names are written in Chinese characters). In his preface, Gao Zongshun 高宗舜 frames the Updated Compendium as part of a commercially driven patriotic imperative to support Chinese steam navigation skills, without which “shipping rights will certainly fall into the hands of foreigners.”54 Gao’s geopolitical anxieties, along with the new views of Yichang and Chongqing and the inclusion of material copied from Plant’s Handbook, visualize the river as an object of international commercial and political rivalry. In framing the Upper Yangzi for a Chinese audience, Yang Baoshan and Gao Zongshun also encourage its reinscription as a national Chinese river, on which the rights of Chinese merchants should predominate.

As an artifact of conceptual and economic transitions, the Updated Compendium responds to and participates in the reinscription of the river by drawing on a seemingly traditional cartographic technique—the use of pictorial landscape representation. This is perhaps the most obvious difference between the group of Chinese charts I have been discussing in this section and those produced by Plant and Blakiston for a Western readership. In the former, major cities are not depicted from above, fixed within the relational grid of longitude and latitude, but rather framed by stylized mountains. Information about distances and administrative boundaries is conveyed not through scale measurements or conventionalized symbols, but through the annotations that occupy blank space above the landscape and the textual route guides that accompany the chart. At least superficially, the maps contained in Luo Jinshen’s Essential Guide (1883), Guo Zhang’s Critical Chart (1901), and Yang Baoshan’s Updated Compendium (1923) seem to have more in common with The Shu River painting of the Song Dynasty than with Blakiston’s chart or Plant’s diagrams. It is only in the Updated Compendium’s alterations to Yichang, with its simple street plan, that we find anything that resembles a “modern,” planimetric map, which renders objects independent of elevation, as though seen from the air.

Tempting as it is to read this addition as a crude attempt to modernize a work of traditional cartography, such an interpretation reinforces a misleading dichotomy between landscape representation as a quintessentially traditional form and mathematical cartography as a modern one. What constitutes the “traditional” in traditional Chinese cartography is, in fact, open to debate. For one Mainland Chinese scholar writing about Guo Zhang’s Critical Chart, “traditional” mapping is described as following a “pictorial landscape method” (shanshui huifa 山水繪法), a “freehand sketch landscape style” (shanshui xieyi shoufa 山水写意手法), or an “impressionistic perspective” (xieyi toushi jiaodu 寫意透視角度) and is contrasted with the “realistic perspective” (xieshide toushi jiaodu 寫實的透視角度) and “symbolic notation” (xiangxing fuhao 象形符號) of Western “planimetric representation” (pingmian fuhao biaoshifa 平面符号表示法).55 As Cordell Yee has argued, however, to judge traditional Chinese cartography based on a perceived lack of modern (i.e., Western) scientific characteristics is to establish criteria that are irrelevant to the form. “Geometric and mathematical fidelity to observed reality was not an overarching aim” of Chinese cartography before the twentieth century.56 Instead, cartography was part of a “unified conception of the arts” in which “oppositions between visual and verbal, cartographic and pictorial, mimetic and symbolic representation may not apply.”57 Landscape painting does not provide the same information as contour lines or triangulation, but it reflects ways of seeing and moving through space no less informative and no less capable of responding to change.

Perhaps more importantly, “landscape,” or shanshui 山水, is not a homogenous or ahistorical form. It may be true that the Critical Chart uses a “pictorial landscape method,” but such a designation provides no information about its particular style of landscape or its artistic medium. While the chart draws on earlier woodblock images, including those of the 1883 Essential Guide, Guo Zhang and the artists with whom he collaborated also had other influences. The fluid lines of their chart closely resemble an orthodox landscape style typical of topographical paintings and woodblock prints of the high Qing.58 The ability of the artists and printers to echo and mass-produce such a finely detailed style, however, was contingent on a technology that was central to China’s “visual modernity”—lithography.59 Introduced into China in 1826 by the English missionary Robert Morrison, lithography became commonplace only in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, when it was used to publish books, periodicals, and visual materials.60 Capable of producing images quickly and cheaply, lithography is what made the mass print culture of the late Qing possible.

The links between Guo Zhang’s Critical Chart, its adaptation in the Updated Compendium, and earlier images of the river are easy to see. What is less obvious is how these examples of “traditional” landscape-based cartography embody the shifting technological and representational currents of a modern China in formation. They remind us that the reinscription of the Yangzi and its Gorges as national Chinese landscapes was not based solely in the universalizing methods of Western cartography. Planimetric maps would eventually supplant pictorial charts of the Yangzi, but the popularity of Luo Jinshen’s Essential Guide and the existence of multiple editions and updates of the Critical Chart suggest that older ways of knowing and navigating the river remained important to both Chinese and Western travelers and merchants through the 1920s.

“A LAND OF LEGEND”

If Guo Zhang’s chart appears “traditional,” perhaps it is because modern Western maps of the Yangzi eschew landscape, even as their makers and users produced landscape images in great quantities for a readership hungry for scenes of China. It is this dissociation—explicitly promoted by Blakiston—that makes landscape such an important counterpart to and alibi for commercial, territorial, and resource forms of imperialism. By promoting a systematic geography against the fantastic landscapes familiar to British readers, the maps produced by Blakiston, Plant, and others framed the Yangzi in order to open it up to forces eager to exploit it. Despite their scientific pretensions, these maps are not so much descriptive as prospective tools—a class of treasure maps. They depict China “as it is” for the benefit of those invested in what it might become. In this sense, they are as much objects of fantasy as the timeless landscape of the willowware pattern. And like the willowware pattern, they frame the Chinese landscape in repeatable form—emptied of local detail and offered up as a commodity (and source of commodities). Contrary to Blakiston’s claims, the romance of the “willow pattern” landscape and the universal objectivity of Arrowsmith’s chart are two sides of a shared method of producing and exploiting Chinese space.

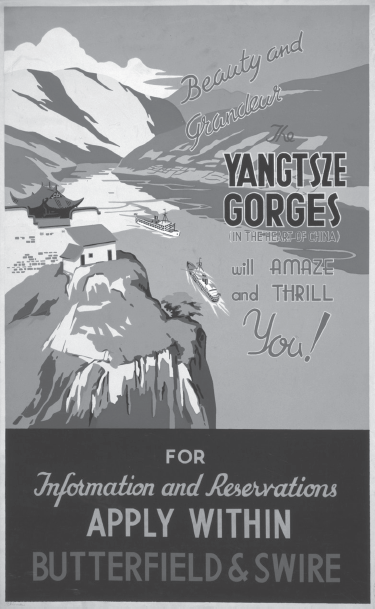

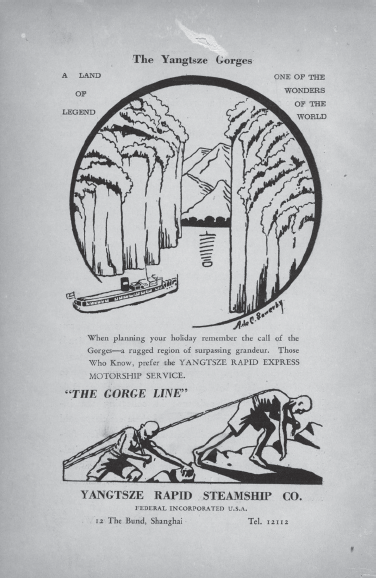

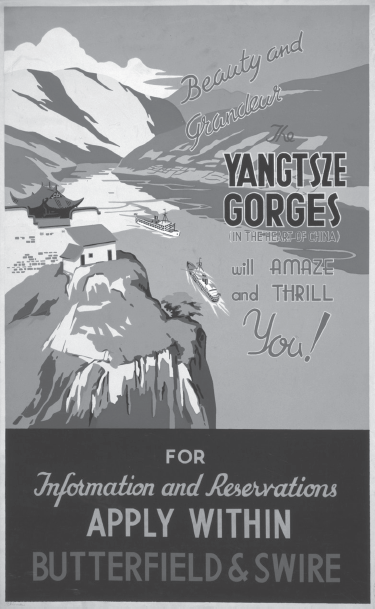

As the Yangzi and its Gorges became increasingly legible over the course of the nineteenth and early twentieth century, the fantastical Chinese landscapes that Blakiston rejected began to return in new guises. No longer scenes of “golden-pheasants innumerable…porcelain pagodas and high-arched bridges,” landscapes in the age of steam signaled their Chineseness in more subtle ways. In a 1930 travel poster for the Hong Kong– and Shanghai-based trading and shipping company Butterfield & Swire (figure 3.13), for example, a traditional structure with upturned eaves and a tiled roof looks down serenely on two steamships crossing in opposite directions. The Gorges are promoted here as a landscape of “beauty and grandeur” that is made accessible, but otherwise unchanged, by modern technology. The Chineseness of the landscape plays an equally large role in an advertisement that precedes H. G. W. Woodhead’s The Yangtsze and Its Problems (figure 3.14), a collection of newspaper articles written in the spring and summer of 1931 and originally printed in the Shanghai Evening Post and Mercury.61

FIGURE 3.13 A 1930 travel poster for the Hong Kong– and Shanghai-based trading and shipping company Butterfield & Swire. See also color plate 9.

Source: U.S. Library of Congress

FIGURE 3.14 Yangtzse Rapid Steamship Co. advertisement from H. G. W. Woodhead’s The Yangtsze and Its Problems (1931).

This advertisement (figure 3.14), for the American-owned Yangtsze Rapid Steamship Co., occupies a full page between the text’s Introduction and opening plate and is split into two pictorial fields.62 The upper field (I discuss the lower field in the next chapter) is contained within a circular frame and consists of a river gorge formed by steep, corrugated cliffs. A steamship enters the scene at lower left through a break in the frame. The sleek boat, accompanying text, and landscape promise not only a wondrous experience, but a modern one—motorized and express. Despite such promises, few travelers of any nationality were likely to be traveling with such ease on the middle and Upper Yangzi in 1931.63 According to Woodhead, the presence of Communist snipers shooting “indiscriminately” at boats from the banks of the river caused a precipitous drop in Chinese shipping and travel on the middle Yangzi around 1930.64 Because they could call on the protection of gunships of the “British and Other Navies,” foreign steamers were less adversely affected, though they could still be commandeered by Chinese troops looking for transport upriver.65 Woodhead’s own boat, which was owned by the Yangtsze Rapid Steamship Co., was seized for such purposes in February of 1928.66

The Yangtsze Rapid Steamship Co. advertisement shows no evidence of the many “problems” that Woodhead catalogs. Instead, it offers not only the promise of speed and comfort but also a taste of the cultural difference that gives the river journey its exciting exoticism for Western travelers. The landscape’s Chineseness is subtle, almost subliminal. It appears first in the circular frame, its variations in thickness suggesting the trace of a calligraphic brush, and is reinforced by what look like ripples or reflected light on the water of the river. The artist has rendered this pattern as a small, open box topped by a series of seven horizontal lines that grow larger as they approach the center of the circle, where they are topped by an eighth horizontal line and a small vertical line. The overall effect is of an elongated variation on the Chinese character yan 言, which means “to speak.” Though few of the expatriate readers or tourists targeted by this advertisement would have read these ripples as 言, their textual character makes a powerful promise: that the artist and the advertisement, and by extension the Yangtsze Rapid Steamship Co., “speak the language,” that they offer unmediated access to this “land of legend.”

To see the Chinese script “writ large” on and as landscape was nothing new.67 For centuries, it had been idealized as a form of pure writing, a natural language or pictographic script. With origins in seventeenth-century philosophy and a legacy that extends to contemporary tattoo parlors, the idea that Chinese signifies without recourse to speech, that it maintains a natural connection to the realm of things and actions, has long “functioned as a sort of European hallucination.”68 The textlike lines at the center of this advertisement rely on just such a mirage: they draw on the imagined legibility of Chinese as natural language to promise the viewer and traveler access to a Euro-American “hallucination” of China as a land of wonder. The steamship notwithstanding, we seem far removed from Blakiston’s universal landscape. What brings us back to it, however, is the circular frame that contains this Chinese “text” and landscape. Though designed to look as though it were drawn with a traditional ink brush, the frame’s perfect roundness also evokes the technical extension of the eye in the camera, telescope, binoculars, and theodolite, optical technologies central to attempts to “realize” the Chinese landscape by fixing it scientifically. A form of porthole picturesque, this encircled scene distills the structural logic at the heart of landscape representation in an imperial mode—it represents the physical world as a discrete visual field, isolated from its surroundings and consumable as landscape from the perspective of a sovereign viewer.

As in the map that completes Blakiston’s narrative (see figure 3.6), the frame directs an act of penetration that is literalized by the break in the circle and the boat that moves through it.69 Designed to enclose, it also opens the landscape to the viewer as imagined traveler. This particular frame does not capture territorial prospects, however; it offers up an image of the natural world as object of both touristic consumption and technological domination. As touristic images, both of these advertisements represent the goal of a fully commercialized cultural landscape, a conflation of the economic and aesthetic interests that remain segregated in a work like Blakiston’s. As poetic images of technological domination, they use landscape to promote a version of what Donald Worster calls the “ ‘imperial’ view of nature.”70 It is this form of imperialism, which makes the Chinese landscape not only accessible through the introduction of new technologies and the removal of physical obstacles to movement but also productive through the extraction of resources, that further links British legacies of territorial and “free trade” imperialism with national development projects such as the Three Gorges Dam, which reduces the entirety of the Yangzi to a natural resource.71

The “ ‘imperial’ view of nature” is grounded in the idea “that man’s proper role on earth is to extend his power over nature as far as possible.”72 Worster’s use of “imperial” is analogical, but the imperialism that he attributes to Baconian and Linnaean natural history did, in fact, undergird the modern scientific disciplines that developed alongside European imperialism and colonialism in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.73 As expressions of an imperial view of nature developed as part of imperial and colonial enterprises around the world and later adapted to support national development through the management of natural resources, the scientific disciplines of geology, geography, natural history, hydrography, and cartography were deployed to rationalize and control Asian space. Beginning in the second half of the nineteenth century, scientists working in a range of disciplines, as well as explorers, artists, tourists, and merchants, contributed to the reinscription and reconceptualization of the Yangzi and the Three Gorges by using increasingly sophisticated technologies, many of them visual. Intentionally or not, they helped advance not only territorial and commercial imperialisms, but also a form of resource imperialism that relied on the visual framing of the land as a means of supporting (and sometimes distracting from) the exploitation of its natural resources. They also laid the foundation for a touristic conception of the landscape that was contingent on its spatial reorganization but invested in promoting its immutability.

Territorial and commercial forms of imperialism in China have been well studied, but modern resource imperialism and its links to both Qing empire and post-Qing national development have received far less attention, partly because, with the exception of the Japanese annexation of Manchuria beginning in 1931, foreign imperial powers were not able to gain control over large areas and the resources they held.74 This does not mean, of course, that such resources were not of interest to European travelers. The people of the Upper Yangzi had little trouble intuiting the link between the seemingly innocent use of cameras, binoculars, and telescopes and the extractive desires of foreign travelers, even if they had no knowledge of modern geology and the types of mining it made possible:

The men asserted, as they did everywhere on the river, that with my binoculars and camera I could see the treasures of the mountains, the gold, precious stones, and golden cocks which lie deep down in the earth; that I kept a black devil in the camera, and that I liberated him at night, and that he dug up the golden cocks…. They further said that “foreign devils” with blue and grey eyes could see three feet into the earth.75

This passage from Isabella Bird’s 1899 travelogue is intended to illustrate the ignorance of the Chinese population, a variation on the more familiar theme of the camera as soul-stealing device.76 The Scottish photographer John Thomson dismissed Chinese anxieties by drawing on similar tropes:

The literati, or educated classes, had fostered a notion…that, while evil spirits of every kind were carefully to be shunned, none ought to be so strictly avoided as the “Fan Qui” or “Foreign Devil,” who assumed human shape, and appeared solely for the furtherance of his own interests, often owing the success of his undertakings to an ocular power, which enabled him to discover the hidden treasures of heaven and earth.77

What the locals that Bird and Thomson encountered accurately divined was the complicity among travel, commerce, political interests, and the optical technologies that framed the Chinese landscape in order to realize it. Regardless of what the upper and lower classes of China actually believed about photography, the fear of the “ocular power” of the “Foreign Devil” that is ascribed to them is prescient. As cultural producers, Bird, Thomson, and others used their binoculars and cameras to mine the land for Chinese scenes and figures—fantastical, amusing, picturesque, typical—exporting them to eager reading publics around the world. The technologies they deployed were often identical to those used both in the imperial production of rationalized Asian landscapes for military and commercial conquest and in the resource imperialism that sought to exploit those landscapes. In framing the Yangzi as geographic, commercial, and scenic prospect, cameras, telescopes, binoculars, artificial horizons, and theodolites created the conditions of possibility for those eager to exploit the landscape, reconfiguring the entirety of the Yangzi as a natural resource capable of producing not only exotic adventure but also raw materials and massive amounts of energy.

One of the early steps in the reconceptualization of the landscape as a source of energy can be traced not to British interest in “golden cocks,” but to a less glamorous “treasure”—coal. Through the end of the nineteenth century, European travelers paid careful attention to the distribution of coal seams and active mines along the Yangzi (see figure 3.4).78 They were concerned not with exporting the raw material, or using it for domestic and industrial purposes as Chinese residents of the region did, but with using it to fuel the steamships they hoped to introduce on the river. Steam travel’s demand for coal encouraged travelers to see and make seen the region surrounding the Yangzi not just as a massive market or source of raw goods, but also as a ready reserve of potential energy similar to what Martin Heidegger, in “The Question Concerning Technology,” calls a “standing reserve” (Bestand). For Heidegger, the act of “revealing” the natural world as a source of power constitutes “a challenging [Herausfordern], which puts to nature the unreasonable demand that it supply energy which can be extracted and stored as such.”79 Revealing and challenging are not simply ways of using modern technology to act on nature; they change how one experiences and sees the earth: under modern geology and mining, “the earth…reveals itself as a coal mining district, the soil as a mineral deposit.”80

In Heidegger’s account, nature is “revealed” as “standing-reserve” through a process he calls “enframing” (the German word is Gestell, a noun meaning frame or skeleton that Heidegger turns into a verb). Heidegger compares “enframing” to the Greek word poiesis, a form of making or “bringing forth” that he famously identifies as a “saving power” against the more destructive forces of modern technology.81 What concerns me here is not the purported saving power of the poietic, but rather the ways in which the visual, textual, and conceptual reinscription of the Yangzi and its Gorges as Chinese landscapes contributed to their enframing as a natural resource and standing reserve of energy “that [could] be extracted without limit and used without depletion,” as Sun Yat-sen describes hydroelectric power generation. Landscape in all its many forms is contingent on framing—the demarcation of a discrete unit from a larger whole, which stands within its frame as a unified entity. Framing is the ur-condition for landscape, both in its sense as an art genre and in its extended meaning as a distinct tract of land. The framing of a poem or landscape image does not simply “reveal” the landscape; it abstracts and challenges it, transforming it into a sign that can be emptied and filled at will—it makes of it a standing reserve of the symbolic, which can then be mobilized in the physical transformation of the landscape.

The landscape in the Yangtsze Rapid Steamship Company’s advertisement does not simply sell a fantasy of oriental ease and adventure; it also prefigures the dammed Yangzi’s future as a reserve of energy, a route for commerce, and a touristic object. It does the last by presenting the river and its landscape as inviting prospects accessible through the break in the frame. There is no trace of the obstacles that still made the Yangzi so dangerous in 1931. Instead, we see the river as placid lake and the old promise of “free” access fulfilled by the convenience of modern travel. The circle and the landscape it contains are no longer a Chinese mirage or imperial prospect but a touristic target, the linguistic ripples its bull’s-eye, the steamship its luxurious arrow. The river is revealed here as a touristic destination forever on reserve. The aesthetic and affective claims of the advertisement are contingent, however, on the long history of rationalization and scientific framing that led to the enframing of the river as a source of natural resources and, eventually, a resource in its own right. As in the river charts, it is the advertisement’s frame that enframes the landscape, offering it up as visual and material prospect.

What I am suggesting here is that technological enframing is sometimes prefigured by aesthetic framing and that framing can also challenge the earth. In other words, poetic and pictorial landscape representation might support, directly or indirectly, the construction of dams, and vice versa. Before the Three Gorges Dam extended across the Yangzi, it first towered in Mao’s “Swimming.” For decades, many scholars have understood landscape art in the West as a way of seeing the world that is intimately bound up with the extractionist and expansionist ideologies of capitalism, imperialism, and nationalism: landscape frames the world it seeks to possess. In contrast, Chinese shanshui 山水 traditions in poetry and painting are frequently described as a way of seeing the world not as it appears to the eye, but in its conventionalized forms, according to systems of cosmological, political, and literary symbolism. In such accounts, landscape frames the underlying structures of the world, but does not necessarily seek to represent it mimetically, let alone possess and transform it physically. But what if the relationships between symbolism and mimesis, idealization and possession, traditional and modern, Eastern and Western and landscape, were blurrier than they seem? How might framing, as both the formal feature of aesthetic landscape and the ground of enframing, persist across cultures and over a timescale far greater than that proposed by Heidegger or those scholars writing about Western landscape since the 1400s?

The Three Gorges Dam is a monument to the imperialist-modernist exploitation of nature updated for China’s global rise. It is also an expression of a 2,500-year-long representational tradition manifested in multiple media, technologies, and languages. The mythology of Yu the Great, the lyrical prose of Li Daoyuan’s Commentary to the Classic of Rivers, Li Bai’s and Du Fu’s poetry, Blakiston’s, Plant’s, and Guo Zhang’s charts, the Yangtsze Rapid Steamship Co. advertisement, Mao’s “Swimming,” and the Three Gorges Dam are historically distinct expressions of a landscape tradition that not only frames but also enframes the earth.

Over the course of more than two millennia, the poetry, prose, and painting of the Three Gorges have produced a cultural landscape grounded in a set of images, metaphors, and tropes that have remained remarkably stable, even as the natural and built environment of the region has changed in significant ways. This landscape is in turn deeply rooted in an inscriptional tradition that makes the Three Gorges Dam thinkable as a simultaneously symbolic and material form of landscaping. The dam exists not simply because the hydrology of the Yangzi makes it practicable, but because, starting with Yu the Great, the Three Gorges have been inscribed and reinscribed as a land of wonder. It is the enduring fame of this inscriptional landscape that makes it an especially attractive site for a project that links the “Chinese people’s spirit of tenacious struggle” against nature with the political and economic triumphs of contemporary China (as Jiang Zemin does in the second epigraph to this chapter), while also concealing the environmental and social consequences of a mega-dam behind timeless images of rugged gorges and tales of mythical flood-quellers.