![]()

America’s second war against Saddam Hussein was all but foreordained even before the dust from Desert Storm had fully settled. The authors of the first book on Iraqi Freedom to appear in print attributed the second Gulf War, “on the simplest level,” to “the failure of the United States’ policy makers to seize the victory its armed forces had so decisively won in the winter of 1991.”1 The allies had indeed succeeded in evicting Iraqi forces from Kuwait in less than six weeks of fighting, but the campaign did not break the back of Hussein’s Republican Guard. More important, it left the Iraqi dictator in power and allowed him to convince himself that he had actually “won” the war, thanks to the incompleteness of the allied coalition’s victory. Emboldened by Iraq’s ostensible “victory,” Hussein and his senior subordinates taunted the United States and the UN throughout the 1990s by repeatedly violating UN-imposed disciplinary resolutions and then retreating only at the last minute when confronted with a credible show of U.S. force.

In the early aftermath of Desert Storm, many observers asked why the coalition’s ground advance had ended after only four days of uninterrupted progress, just as allied air and land operations had moved into what is commonly called the exploitation phase of war, with Iraq’s occupation forces in Kuwait not just in retreat but in uncontrolled flight. In response, the first Bush administration’s leadership insisted that the intent of the campaign plan and of the crucial UN and congressional resolutions that had authorized and enabled it had never been to knock Iraq out of the regional security picture altogether, but merely to free Kuwait from Hussein’s military occupation. President Bush and his most senior associates further insisted that had the United States pressed all the way to Baghdad in an effort to end Hussein’s rule, America would have found itself bogged down in an Iraqi quagmire.2 Secretary Rumsfeld recalled in his memoirs that “regime change in Baghdad had not been among the U.S. goals when the pledge to liberate Kuwait was first made. The [first Bush] administration felt it would not have full coalition support if it [had] decided to continue on to Baghdad.”3

Yet a full-blown invasion of Iraq with a view toward driving out Hussein and his Ba’athist regime was not the only alternative to declaring a cease-fire just as the allied air and land offensive had moved into high gear. A less ambitious and problematic alternative might simply have been for the coalition to continue its ongoing air-land assault against the fleeing Iraqi forces for another twenty-four to forty-eight hours. Not only would such an alternative have remained within the spirit and letter of UN Resolution 678 authorizing the use of “all means necessary” to undo Hussein’s conquest of Kuwait, it might also have broken the back of the Iraqi military and unleashed internal forces that might have brought down Hussein’s regime on their own. Whether such an outcome would have ensued from the exercise of that alternative option will never be known. It remains, however, a telling fact of Desert Storm history that perhaps the war’s single most memorable quotation—Gen. Colin Powell’s confident assertion on the eve of the war, on being asked by a reporter what the allied strategy against Iraq’s army would be, that “first, we’re going to cut it off, and then we’re going to kill it”—was only half correct.4

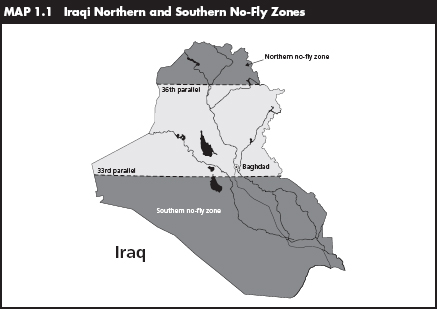

Hussein continued to pursue a confrontational policy toward the West throughout the decade that followed. He repeatedly violated the terms of the Desert Storm cease-fire arrangement and continued to pursue an active WMD program, albeit ineffectively. Despite determined Iraqi obstructionism, UN inspectors uncovered evidence of a far-ranging effort to acquire chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons. Hussein’s efforts to hamper the inspectors gave the clear impression that he had something to hide. Ultimately, he threw out the UN inspectors altogether. He also repeatedly challenged allied efforts to enforce the UN-approved no-fly zones over Iraq by firing on patrolling allied combat aircraft—some seven hundred times in 1999 and 2000, and more than one thousand times more by September 2002 (see map 1.1).5 He even tried to have his Desert Storm nemesis, the first President Bush, assassinated in 1993 while the former president was on a personal visit to Kuwait.6

Source: CENTAF

Throughout the eight years of the administration of President Bill Clinton, the United States pursued a series of measures that were more symbolic than determined either to force a change in Hussein’s behavior or to terminate his transgressions once and for all. Those measures, which included cruise-missile attacks against unoccupied government buildings in the dead of night and the limited-objectives Operation Desert Fox air strikes that were conducted for four nights in 1998, served to reinforce Hussein’s assessment of the United States as weak-willed and irresolute. In Secretary Rumsfeld’s opinion, the Iraqi dictator “came to believe that the United States lacked the commitment to follow through on its rhetoric. He saw America as unwilling to take the risks necessary for an invasion of Iraq. As he would explain to his interrogators after his capture in December 2003, Saddam had concluded that America was a paper tiger. He interpreted the first Bush administration’s decision not to march into Baghdad as proof that he had triumphed in what he called ‘the mother of all battles’ against the mightiest military power in history.”7

Saddam Hussein was thus arguably fated for a decisive showdown with the United States. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, almost certainly sealed Hussein’s fate by fundamentally altering the Bush administration’s assessment of the WMD threat, whether direct or indirect, posed by Ba’athist Iraq. The attacks also made it that much easier for the administration to persuade the American people of the merits of invading Iraq. The combination of the most consequential terrorist attack on U.S. soil in American history and Hussein’s persistent defiance of UN resolutions prompted an ultimate conviction—right or wrong—among the administration’s principals, most notably President Bush himself, that the Iraqi ruler had to be dealt with decisively before another event of the magnitude of September 11 occurred as a result of his malfeasance. As early as September 17, 2001, less than a week after the terrorist attacks, the president signed a memorandum directing the U.S. defense establishment to begin planning not only an offensive against the Taliban in Afghanistan, but one against Iraq as well.8 As the Department of State under Colin Powell continued to pursue resolutions to enforce Iraq’s compliance with the UN’s edicts, the Department of Defense under Donald Rumsfeld began preparing for war.

Laying the Groundwork

Even before the first combat moves took place in Afghanistan in early October 2001, senior Bush administration officials already had their sights set on Hussein as a perceived problem to be dealt with at the earliest opportunity in the rapidly unfolding global war on terror. On the very afternoon of the September 11 attacks, Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld broached the idea of going after Iraq as an early possible response when he wrote a note to himself asking whether to “hit S.H. [Saddam Hussein] @ same time—not only UBL [Usama bin Laden].”9 Immediately thereafter he directed Under Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz to enlist the assistance of the Pentagon’s legal staff in determining a possible Iraqi connection with bin Laden.

At a gathering of the president’s emerging war cabinet the next day, Rumsfeld asked whether the terrorist attacks had presented an “opportunity” to go after Iraq.10 Two months later, with Operation Enduring Freedom in full swing, President Bush followed up on that query. He pulled Rumsfeld aside after a National Security Council meeting on November 21 and asked him: “What kind of a war plan do you have for Iraq? How do you feel about the war plan for Iraq?”11 He also asked Rumsfeld if a buildup for such a war could be initiated in a manner that would not be clearly apparent as such. With respect to this early attention to Iraq on the administration’s part, Rumsfeld later attested to the almost instant crystallization of a sense among key administration leaders that the nation could no longer deal with terrorist threats from a defensive posture alone: “You can’t defend at every place at every time against every technique. . . . You have to go after them. And you have to take it to them, and that means you have to preempt them.”12

In his State of the Union address on January 29, 2002, Bush referred for the first time to what he called the “axis of evil” comprising Iraq, Iran, and North Korea (with the latter two reportedly included in part to make Hussein feel that he was not being singled out). The president added that the quest for WMD by these three countries and their known trafficking with terrorists had made for an intolerable convergence. Mindful of the September 11 precedent, he swore: “I will not wait on events while dangers gather.”13 Columnist Charles Krauthammer later characterized the speech as “just short of a declaration of war” on Iraq.14

On February 16, 2002, President Bush signed an intelligence order directing a regime change in Iraq and empowering the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to support the pursuit of that objective by granting the agency seven new tasks: to support Iraqi opposition groups, to conduct sabotage operations inside Iraq, to work with third countries, to conduct information operations, to run a disinformation campaign, to attack and disrupt regime revenues, and to disrupt the regime’s illicit purchase of WMD-related materiel.15 The following month, CIA director George Tenet met secretly with Massoud Barzani and Jalal Talabani, the leaders of the two main Kurdish groups in northern Iraq. The Kurds were still simmering over the failure by the previous Bush administration, in the early aftermath of Desert Storm, to follow through on its promise to support a Kurdish uprising, as a result of which Hussein’s troops slaughtered thousands of Kurdish rebels. Tenet’s message to the two Kurdish leaders was clear: this time the American president meant business. Saddam Hussein was definitely going down.16

While hosting British prime minister Tony Blair and his family at the Bush ranch in Crawford, Texas, on April 6, 2002, Bush declared to a reporter during a televised interview: “I made up my mind that Saddam needs to go. That’s about all I’m willing to share with you.” When pressed for further details, the president replied firmly: “That’s what I just said. The policy of my government is that he goes.” Bush added: “The worst thing that could happen would be to allow a nation like Iraq, run by Saddam Hussein, to develop weapons of mass destruction, and then team up with terrorist organizations so they can blackmail the world. I’m not going to let that happen.” When asked how he intended to forestall such a dire development, Bush replied: “Wait and see.”17

The major combat phase of Operation Enduring Freedom had barely ended in April 2002 before the administration began radiating indications that planning was under way for a major offensive against Iraq to begin sometime in early 2003. In his commencement address at West Point two months later President Bush declared: “If we wait for threats to fully materialize, we will have waited too long. We must take the battle to the enemy, disrupt his plans, and confront the worst threats before they emerge.”18 The president also unveiled his emerging idea of preemptive warfare, telling the assembled cadets: “The war on terror will not be won on the defensive.”19 Soon thereafter, Vice President Dick Cheney told the crew of the aircraft carrier USS John C. Stennis operating in the Arabian Sea: “The United States will not permit the forces of terror to gain the tools of genocide.”20

On September 1, 2002, Bush told his national security principals that he wanted to secure a resolution by Congress to support military action against Iraq. Toward that end, he invited eighteen key members of the Senate and House of Representatives to the White House on September 12 and reminded them that Congress had declared as far back as 1998, by an overwhelming majority, that a regime change in Iraq was essential. He further stressed that his administration had embraced that view with even greater conviction after September 11. He added: “Doing nothing is not an option.”21 Bush gave a speech to the UN General Assembly that same day emphasizing Iraq’s repeated noncompliance with a succession of Security Council directives. While preparing for that speech he had told his speechwriter: “We’re going to tell the UN that it’s going to confront the [Iraq] problem or it’s going to condemn itself to irrelevance.”22

In a major speech on October 7, 2002, Bush declared that Iraq “gathers the most serious dangers of our age in one place.” He added: “Facing clear evidence of peril, we cannot wait for the final proof, the smoking gun, that would come in the form of a mushroom cloud.”23 Two days thereafter, following two days of intensive debate, the House of Representatives passed a resolution empowering the president to use force in Iraq “as he deems to be necessary and appropriate.” The resolution passed by a vote of 296 to 133, gaining 46 more votes than President George H. W. Bush had garnered in support of Operation Desert Storm in 1990. The following day the Senate approved the same resolution by a vote of 77 to 23.24

On November 8, 2002, the UN Security Council voted 15 to 0 in favor of UN Resolution 1441, which held Iraq in material breach of previous resolutions and ruled that if Hussein continued to violate his disarmament obligations he would face “serious consequences.”25 Such a resolution had been one of Prime Minister Blair’s requirements before the United Kingdom would agree to participate in a war against Iraq, and he had already made that clear to Bush. Later, facing an imminent vote of confidence in Parliament, Blair urged Bush to seek a second UN resolution supporting action in Iran. In the end, the president elected not to do so, on the understandable ground that the 15-to-0 vote that had been registered for the first resolution would now be regarded as the expected bar, and that seemed unattainable a second time around.

In his third State of the Union address, on January 28, 2003, the president went further yet in putting the world on notice that the United States was determined to nip any assessed Iraqi threat in the bud: “Trusting in the sanity and restraint of Saddam Hussein is not a strategy, and it is not an option. . . . We will consult. But let there be no misunderstanding. If Saddam Hussein does not fully disarm, for the safety of our people and for the peace of the world, we will lead a coalition to disarm him.”26 The two most insistent charges presented by the Bush administration in justification of these threats were Iraq’s alleged (and later discredited) ties to Osama bin Laden’s Al Qaeda terrorist network and its suspected WMD program. In its Key Judgments section, a ninety-two-page National Intelligence Estimate flatly asserted that “Baghdad has chemical and biological weapons,” even though the estimate’s supporting text was reportedly more ambivalent.27

As the United States edged ever closer to war, palpable tensions arose among Bush’s national security principals, with “Powell the moderate negotiator and Rumsfeld the hard-line activist.”28 Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward called Wolfowitz “the intellectual godfather and fiercest advocate” for a forceful end to Hussein’s regime and portrayed Vice President Cheney as “a powerful, steamrolling force” throughout the lead-up to the war against Iraq.29 Even before President-elect Bush was inaugurated—and nearly eight months before the September 11 attacks—Cheney had approached the outgoing secretary of defense, William Cohen, and indicated that he wanted to get Bush “briefed up on some things,” to include a serious “discussion about Iraq and different options.”30

Framing a Plan

In consonance with the administration’s thinking in the early aftermath of the September 11 attacks, Secretary Rumsfeld directed that all regional combatant commanders review their contingency plans from the ground up, starting with the most basic assumptions. Rather than merely fine-tuning existing plans, he said, “we’re going to start with assumptions and then we’re going to establish priorities.” At the same time planners were to make every effort to compress the planning cycle dramatically.31

In its planning for dealing decisively with Hussein, CENTCOM had the advantage of ten years of uninterrupted involvement in the region as a result of its mandate to enforce the southern no-fly zone. Effective intelligence preparation of the battlefield was thus less acute than it would have been had the command faced a totally new theater of operations, as had been the case for Afghanistan the year before. Because Iraq’s main vulnerabilities and centers of gravity were well known and understood, discriminating and effective targeting could be conducted from the earliest moments of any campaign. On this point, the CIA had recently concluded that major military force would be required to topple Hussein’s regime because any attempt to foment a coup by covert action from within would simply play to the regime’s greatest strengths.32

While the major combat phase of Operation Enduring Freedom was still under way in Afghanistan, Rumsfeld called Franks on November 27, 2001, and told him that the president wanted the defense establishment to look at military options for Iraq. (Rumsfeld later recalled that the president had asked him on November 21 about the status of U.S. contingency options against Iraq. Rumsfeld had replied that there was already a plan in hand, but not one that the president would wish to implement. “Get one,” the president countered.)33 Rumsfeld also asked Franks for the status of CENTCOM’s planning in that regard. Franks replied that his command’s existing Operations Plan (OPLAN) 1003-98 for Iraq was essentially just Desert Storm II and characterized it as “stale, conventional, predictable,” and premised on a continuing U.S. policy of containment.34

The basic OPLAN 1003-98 was roughly two hundred pages long. More than twenty annexes on logistics, intelligence, and individual component operations added an additional six hundred pages.35 The plan had last been updated after the conclusion of Operation Desert Fox in 1998, yet it remained troop-heavy and did not account for subsequent advances in precision attack and command and control capability. It outlined an assault on Iraq intended to overthrow Saddam Hussein by an invading force of 500,000 troops, including 6 Army and Marine Corps divisions, to be led by air attacks and followed by a surfeit of armor. Rumsfeld characterized the plan in his memoirs as essentially “Desert Storm on steroids.”36

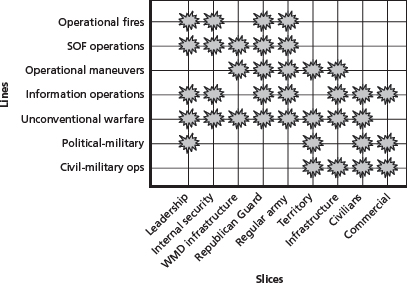

In response to Rumsfeld’s incessant prodding for more imaginative alternatives, Franks developed a new approach that was dominated by a matrix of seven so-called lines of operations and nine “slices,” the latter a concept that had been suggested earlier by Rumsfeld.37 The lines of operations embraced various ways of influencing Iraqi behavior, either singly or in combination. The “slices” sought to define the assumed centers of gravity of Hussein’s Ba’athist regime. The underlying idea of this new approach was to exploit not just military force but all elements of national power in going simultaneously after all identifiable regime vulnerabilities.

Franks’ proposed seven lines of operations were intended to minimize the amount of brute force that would be needed to bring down the regime. They included kinetic operations consisting of precision attacks by both air- and surface-delivered firepower; unconventional warfare involving Special Operations Forces (SOF) activities throughout Iraq; operational maneuver by high-speed and high-mobility Army, Marine Corps, and British ground forces; influence operations involving information and psychological warfare; support for opposition groups, to include the Kurds and disaffected Shia groups; diplomacy, including civil operations after the major fighting was over; and humanitarian assistance to Iraqi civilians.

Franks described the nine slices of Iraqi vulnerabilities in his proposed concept of operations as “a series of pillars, a kind of Stonehenge that supported the weight of the Ba’athists and Saddam Hussein.”38 The slices entailed leadership, notably Saddam Hussein, his two sons, and his innermost circle; internal security, including Iraq’s Special Security Organization, Fedayeen Saddam (Saddam’s Martyrs), with a strength of between 20,000 and 40,000 fanatic paramilitary troops, the Iraqi intelligence service, the Directorate of General Security, and the command and control network; and finally Iraq’s WMD infrastructure, Republican Guard forces, regular army, land and territory, civilian population, and commercial and economic infrastructure.

These two overlapping constructs—the lines of operation and the slices—produced a matrix of combat options and Iraqi vulnerabilities consisting of sixty-three intersections that ranged over the full spectrum of identified military, diplomatic, and economic instruments that the United States and any allied coalition could employ in an effort to topple Hussein’s regime (see figure 1.1).

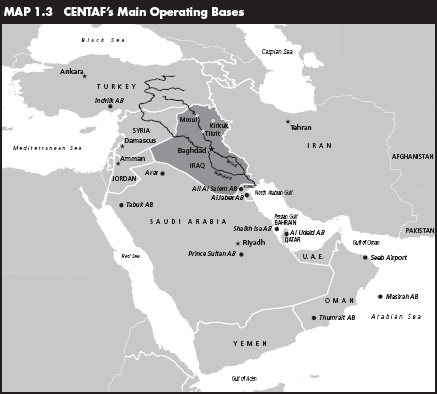

Franks further proposed three generic force employment options as a basis for a more detailed weighing of alternatives. His robust option assumed unrestricted combat and combat-support operations conducted from Turkey, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and other Persian Gulf states. It further assumed freedom for CENTCOM to stage forces from forward operating locations in Central Asia, as well as from Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria, and from U.S. aircraft carriers operating in the Mediterranean Sea, Red Sea, and North Arabian Gulf. This option offered the advantage of simultaneous or near-simultaneous operations. As Franks put it to Rumsfeld: “Simultaneous operations, not separate air and ground campaigns, represent optimum mass.”39 Franks’ second alternative, the reduced option, assumed participation by fewer supporting countries, reduced staging and support, a less concurrent introduction of forces, and a more conventional sequencing of force employment, with initial air attacks followed by a ground offensive. His third alternative was the unilateral option, which would rely solely on U.S. aircraft carriers and on bases in Kuwait. The pattern of force employment would be absolutely sequential, with ground forces introduced only gradually after a prolonged air-only offensive. The unilateral option was, said Franks, “not an option we would want to execute.”40 In all three cases Franks envisaged the required buildup of allied forces in the region as an ebb and flow of assets under the cover of Operations Northern Watch, Southern Watch, and Enduring Freedom, so as to minimize the likelihood that Iraqi intelligence would detect an undeniably threatening trend.

Source: American Soldier

On December 4, 2001, a week after his initial tasking by Secretary Rumsfeld, Franks briefed Rumsfeld and General Myers via secure video teleconference on the first iteration of his commander’s concept for a war against Iraq, with the main objectives being regime takedown and elimination of any Iraqi WMD. Franks subsequently briefed this approach to the president on December 28. During the course of that briefing he indicated that he could set a start date for a planned offensive as early as April to June 2002 if a number of preparatory measures were undertaken in a timely way. Those preparatory measures (a dozen in all) included establishing the requisite interagency intelligence capability, commencing influence operations, gaining needed host-nation support, forward-deploying CENTCOM’s headquarters and needed equipment, forward-deploying the lead Army division, and creating a sustainable logistical line of communications. They also entailed preparing to use the secondary CAOC at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar in case the primary one in Saudi Arabia should not be available, positioning the lead Marine Corps force, preparing for combat search-and-rescue (CSAR) operations, surging a third carrier battle group to the region, pre-positioning other Marine Corps equipment, and pre-positioning aircraft at selected hubs around the world so that an air bridge would be in place and ready to move forces and equipment when they were needed.41

After Franks concluded his briefing to the president, Rumsfeld directed him to come up with an executable war plan within ten days. Franks put his component commanders to work toward that end, with each commander assigned a separate security classification compartment. Only his director of operations, Maj. Gen. Gene Renuart, and a few others were allowed to see the entire picture, with Renuart pulling the overall plan together for Franks.42 Rumsfeld and Franks both later characterized the close interpersonal relationship that evolved between them during this time as “an iterative process.”43

On January 7, 2002, Franks informed his inner circle at CENTCOM that his commander’s concept would be the basis for OPLAN 1003V, a major redesign of OPLAN 1003-98 in response to specific tasking from Secretary Rumsfeld.44 The strategic goals for 1003V were to bring down and drive out the regime of Saddam Hussein; to identify, isolate, and eliminate Iraq’s WMD; to capture or drive out terrorists who had found safe haven in Iraq; to collect intelligence on terrorist networks in Iraq and beyond; to secure Iraq’s oil fields and other resources; to immediately deliver humanitarian relief; and to help the Iraqi people restore and rebuild their country.

The operations order for 1003V, as summarized by CENTCOM’s deputy air component commander, stated that the campaign objectives would be to minimize the strategic exposure of the coalition by a “fast and final” application of overwhelming force that would attack simultaneously along multiple lines of operation, work inside Saddam Hussein’s decision cycle, be prepared for the achievement of “catastrophic success,” and attempt to set the necessary conditions for Iraq’s reconstruction once the Ba’athist regime was driven out.45 The Bush administration’s leadership accepted General Franks’ concept and timetable, and the revised OPLAN 1003V became the “Generated Start” plan. Its underlying premise was that all allied forces would be in place before major combat operations commenced. The plan’s new timeline allowed 30 days for preparation of allied airfields and pre-positioning of equipment (what Franks called the “enablers”), followed by 60 days to deploy the force forward, 3 to 7 days of offensive air operations before the start of ground combat, and 135 days of joint and combined operations to bring down Hussein’s regime. The final committed force would number 300,000 military personnel, a larger force than had been fielded for Desert Storm, but with its required deployment time halved from 180 to 90 days.46

For its contribution to Generated Start, CENTAF divided Hussein’s regime into three broad target categories: leadership, security forces, and the command and control network. With respect to fielded enemy forces, CENTAF wanted to persuade Iraqi ground units to surrender or cease resisting before allied ground forces contacted them directly. Failing that, Iraqi ground units would be attacked from the air until they were neutralized or destroyed. The underlying presumption here was that a focused combined-arms assault would bring about an early collapse of the regime. The principal concern entailed the extent of risk that could be tolerated in any effort to establish the required conditions for such an early regime collapse, particularly considering that the near-concurrent onset of air and ground operations would offer little time to assess the effects of the air offensive before allied ground forces were committed to combat.47

In response to tasking from General Franks, General Moseley established eleven air component objectives for the buildup of forces in the forward area and the subsequent campaign: (1) neutralizing the regime’s ability to command its forces and govern effectively; (2) suppressing Iraq’s tactical ballistic missiles and other systems for delivering WMD; (3) gaining and maintaining air and space supremacy; (4) supporting the maritime component commander to enhance maritime superiority; (5) supporting the land component commander to compel the capitulation of Republican Guard and regular Iraqi army forces; (6) helping to prevent Iraqi paramilitary forces from impeding allied ground operations; (7) supporting the needs of the SOF component commander; (8) supporting efforts to neutralize and control Iraq’s WMD infrastructure and to conduct sensitive site exploitation; (9) establishing and operating secured airfields within Iraq; (10) conducting timely staging, forward movement, and integration of follow-on and replacement force enhancements; and (11) supporting CENTCOM’s quest for regional and international backing. The main challenges that General Moseley saw standing in the way of meeting these objectives included streamlining a suitable command structure for conducting major theater war, standing up the alternate CAOC at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar, seeing to the needs of theaterwide force protection, securing host-nation basing approval, and meeting expeditionary combat support requirements. General Moseley also underscored the severely limited number of available tanker aircraft for in-flight refueling support, significant fuel sustainment requirements, and multiple host-nation airspace challenges.48

General Franks and his staff also began discussing a “Running Start” option, in which covert operations would commence before the start of major combat. This discussion focused on what Franks called “strategic dislocators,” such as Iraq’s firing of Scud missiles into Israel. The prevention of that occurrence, which might provoke Israel to enter the war, was a top priority for CENTCOM because Israeli leaders had put the Bush administration on clear notice that they would not refrain from retaliating against Iraq during this impending war as they had done when Israel had endured repeated Scud attacks during Operation Desert Storm in 1991.49 One way of avoiding that undesirable turn of events would be for allied forces to seize control of all potential Scud launch boxes in western Iraq as soon as possible.50

On February 7, 2002, Franks briefed CENTCOM’s refined Generated Start plan to President Bush. This was the first time the president had been shown a plan that CENTCOM’s leaders believed could actually be implemented. The plan required 225 days for completion, in a breakdown that Franks labeled “90-45-90”: 90 days for laying the groundwork and moving forces to CENTCOM’s area of responsibility, 45 days of aerial bombardment and SOF activities to fix Iraqi forces while CENTCOM assembled its ground force, and then 90 days of joint and combined operations to bring down the Ba’athist regime. The plan envisaged an invasion force reaching 300,000 toward the end, with 2 armored and mechanized infantry corps attacking from the south and a third from the north, should the Turkish government ultimately consent to allow CENTCOM to conduct combat operations from Turkish territory.51

On February 28, 2002, in what Woodward described as taking the lines of operations and slices “from starbursts on paper to weapons keyed on buildings and people,” Franks briefed Rumsfeld on some four thousand potential targets that CENTCOM planners had identified from the latest overhead imagery.52 Those target candidates ranged from leadership, security, and military force concentrations to individual ground-force and air defense units and facilities. They also embraced paramilitary forces, including Hussein’s Special Security Organization (consisting of about four thousand personnel) and Special Republican Guard; command and control nodes; and more than fifty of Hussein’s palaces. Key concerns at CENTCOM included the possibility of Iraq mining waterways, firing Scud missiles into Israel, torching the country’s oil fields, and using chemical weapons (referred to colloquially as “sliming”). The possibility of such disruptive actions forced CENTCOM to compress the so-called shaping phase to an absolute minimum. (On this point, General Moseley later indicated that he had been sufficiently concerned over the possibility of a large-scale Iraqi use of chemical weapons that he arranged for a ninety-day food supply at every CENTAF bed-down location within range of a potential Iraqi air or missile attack.)53

On March 22, 2002, almost a year to the day before the start of Operation Iraqi Freedom, Franks gathered all of his component commanders for his first joint force “huddle” at Ramstein Air Base, Germany. Using an old SOF expression indicating that he was convinced that war was coming and that the time had come for CENTCOM to get serious about it, he told them: “Guys, there is a burglar in the house.”54 He added that CENTCOM’s planning activity was no longer an abstract endeavor and that each component now had to begin focus on its likely operational tasking. For the air component, this meant, first and foremost, precise determination of probable target sets and timing. Outlining his 7 lines and 9 slices and his “90-45-90” plan for a 225-day effort, Franks added: “Don’t let yourself believe that this won’t happen.”55

Franks emphasized his determination to have “joint planning for joint execution,” with “no time [allowed] for service parochialism.”56 Yet despite that injunction, and not surprisingly, in hindsight, a pronounced divergence in outlook regarding how the campaign should begin soon emerged between CENTCOM’s air component commander, General Moseley, and the Army’s land component commander at the time, Lt. Gen. Paul Mikolashek. General Moseley insisted that he needed a minimum of ten to fourteen days, preferably more than that, of air-only operations to disable Iraq’s integrated air defense system (IADS) before allied ground forces commenced their offensive. He particularly stressed the importance of beating down what his planners had taken to calling the “Super MEZ” (missile engagement zone) around Baghdad, which had remained untouched by periodic allied air attacks against various Iraqi IADS nodes inside the northern and southern no-fly zones throughout the twelve years since Desert Storm. Mikolashek, however, wanted the ground component to make the first move, not only to ensure timely seizure and securing of the endangered Rumaila oilfields but also to catch the Iraqis—who would naturally be expecting the war to begin with an air-only offensive—by surprise.57

Franks was reportedly uncomfortable with both men’s perspectives, feeling that Moseley’s prolonged air-only phase exceeded his anticipated needs, but also that Mikolashek’s alternative concept of operations would take too long to get allied ground forces to Baghdad. While he worked to come up with a better solution, he asked General Moseley to start thinking about how the air component might “adjust” (i.e., degrade) Iraq’s air defenses by responding more “vigorously” to Iraqi violations in the no-fly zones.58

In addition, General Moseley unfolded his first cut at a concept of air and space operations for a joint and combined air-land offensive. He stressed that the air armada that would figure centrally in any such offensive was not the one that took part in Desert Storm, Deliberate Force, and Allied Force. CENTCOM’s air component had sharpened its combat edge dramatically since then in four important areas: (1) its command and control and ISR capabilities, including the Global Positioning System (GPS) constellation of navigation satellites, the E-3 Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS, pronounced “a-wax”) and E-8 Joint Surveillance Target Attack Radar System (JSTARS, pronounced “jay-stars”) aircraft, and the RQ/MQ-1 Predator and RQ-4 Global Hawk UAVs (unmanned aerial vehicles); (2) its improved precision all-weather target attack capabilities that would allow CENTAF to engage multiple aim points with a single aircraft rather than the other way around; (3) its improved efficiencies in effects-based operations through more scaled and selective target destruction; and (4) its greatly improved hard-target penetration capability.

To expand on the important third point noted above, effects-based operations tie tactical actions to desired strategic results. They are not about inputs, such as the number of bombs dropped or targets attacked, but rather about intended combat outcomes. At bottom, they ensure that military goals and operations in pursuit of them are relevant to a combatant commander’s core strategic needs. As such, they are better thought of as an organizing device rather than as a more narrow approach to targeting. A classic example of “effects-based targeting” is selectively and methodically bombing enemy ground troops or surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites to induce paralysis or to inhibit their freedom of use rather than attacking them seriatim to achieve some predetermined level of desired attrition through physical destruction.59

General Moseley further noted that CENTAF’s air assets slated for deployment to the war zone would allow attacks against roughly 1,000 Iraqi target aim points per day. In the first category he listed as anticipated targets some 300 enemy IADS facilities, 350 airfields, and 250 systems for the possible delivery of WMD. In the second category he highlighted 400 identified leadership targets, 400 national command and control targets, 400 enemy security and intelligence facilities, 100 key lines of communications, and more than 1,000 potential counterland targets.60 Two days thereafter, the JCS initiated a related planning exercise called Prominent Hammer aimed at assessing the practicality of OPLAN 1003V in such areas as transportation, its impact on U.S. forces worldwide, and its effect on the war on terror and on homeland security. Remarkably, not a hint of this planning exercise ever leaked to the press.61

Franks earlier had decreed that once the war order was given he would need forty-five days to deploy the initial force forward, air operations for another forty-five days, after which offensive ground operations would commence at day 90. He later concluded that ninety days before starting the ground push was an unacceptable length of time and began working on his lines of operations to compress the allotted time, in the process accepting a modicum of risk at the operational level in order to mitigate risk at the strategic level.62 This phase compression inescapably complicated General Moseley’s force apportionment challenge because he was facing a need to conduct five concurrent air battles: the Scud hunt in western Iraq, the establishment of theater air superiority, strategic attack against leadership and command and control targets in Baghdad and elsewhere, support to land-component and SOF operations in southern Iraq, and the same in northern Iraq.63

On March 28 General Moseley convened the first “merge” meeting of planners and operators engaged in the conduct of Operations Northern Watch and Southern Watch to discuss differences in special instructions (SPINs) for aircrews, command and control arrangements, and rules of engagement governing combat operations in each of the two no-fly zones. Because Northern Watch was being conducted under the auspices of U.S. European Command (EUCOM) rather than CENTCOM, this initial meeting provided early insights into what would sometimes prove to be a frustrating relationship between CENTCOM and its sister combatant command in trying to fight a war from several countries that were not in CENTCOM’s area of responsibility. Also during this first merge meeting, CENTAF planners developed a first cut at determining the air component’s likely munitions requirements. Although these assessed requirements would later undergo numerous changes at the margins, this early estimate gave CENTAF’s logistics planners a clear initial look at the problem. In addition, the initial anticipated airspace plan and prospective SPINs for coalition aircrews were drafted for a major air war against Iraq.64

CENTAF’s main operations planners convened their first so-called Dream Team meeting on April 17, 2002, to lay the groundwork for assembling a world-class combat plans team. General Moseley personally met with this group and discussed command and control issues and desired arrangements with respect to Marine Corps involvement in the joint air war to come, as well as best ways of incorporating ongoing Northern Watch operations, combat air patrol (CAP) locations for the defensive counterair mission, and the use of the nation’s global power-projection capabilities. CENTAF’s planners concurrently forwarded their initial master air attack plan (MAAP, pronounced “map”), drafted the previous February, to the Air Staff’s Project Checkmate and to the Air Force Studies and Analysis Agency in Washington so that those expert groups could provide feedback regarding the adequacy of the draft MAAP for anticipated opening-night campaign needs. The feedback that the two groups provided included initial consideration of possible enemy GPS jamming efforts, with Checkmate providing a detailed GPS-jamming study that greatly helped CENTAF planners working to negate any such possible threat.65

CENTCOM’s initial campaign plan envisaged only a single front advancing into southern Iraq from Kuwait. Concerned over that plan’s possible insufficiency to meet prospective worst-case challenges that might arise once the campaign was under way, General Franks sought to explore the possibility of a second front that would concurrently move into northern Iraq from Turkey. (During Operation Desert Storm, Turkey’s Incirlik Air Base had provided an important springboard for strike operations into Iraq.) He summoned the commanders and principal planners from CENTAF and from the land and maritime components to CENTCOM’s headquarters in Florida for a high-level meeting on May 8–10, with the goal of synchronizing emerging ideas in that and a number of other areas. During that three-day meeting, Franks directed his component commanders to begin developing plans for a second-front option into northern Iraq from Turkey. He had little confidence that Turkey would go along with such an option, but he wanted the essential preparations undertaken anyway for an initial U.S. footprint in Turkey of 25,000 to 30,000 personnel.

The assembled participants also addressed the land component’s emerging ground scheme of maneuver and the likely support it would require from the air component, as well as various other notional courses of action. CENTAF’s planners henceforth remained intimately involved in all subsequent land- and SOF-component planning sessions throughout the joint force buildup. That close involvement led to the development of deep trust relationships across component and service lines that would pay off handsomely once major combat began.

In a synopsis of all CENTCOM deliberations to date on May 10, 2002, Franks reviewed with Rumsfeld what the latter called the “known unknowns.” The two also addressed a variety of “unknown unknowns,” one of which was the possibility that Hussein might somehow force the hand of the Bush administration before the latter was ready to be committed. At that still-early stage in the preparations, the only response options available to CENTCOM would involve coalition forces already deployed in support of Operations Northern Watch and Southern Watch. Those forces included a carrier air wing with 70 aircraft and an additional 120 land-based aircraft, which together could enable what CENTCOM called the Blue Plan with 4 to 6 hours’ notice. A more robust White Plan could be executed with about 450 aircraft that could be moved to the region within 7 days of an Iraqi provocation. Finally, a Red Plan involving 750 to 800 aircraft—half the number that had been deployed for Desert Storm—could be readied within about 2 additional weeks to conduct a gradually escalating series of attacks while allied ground forces were deployed to the region for an eventual combined air-land offensive.66

General Moseley’s chief strategist later recalled that

the Blue, White, and Red plans were not developed as separate plans. Rather, they were all part and parcel of a single concept of operations. As the air component began to execute Operation Southern Focus [described in detail below] and to become more provocative in its reactive strike activities, CENTCOM asked the CAOC’s combat plans division to develop a list of possible Iraqi actions and the recommended response to each by coalition aircraft conducting missions in Southern Watch. The Blue list was a roster of response actions that could be handled by in-place Southern Watch forces with a fairly typical Southern Focus strike. A second set of more aggressive possible Iraqi actions was represented in the White category. Such possible actions would be met by a more robust response that would require enough aircraft to execute the sort of response options that had been reflected in Operation Desert Fox. The last category was the Red list of possible Iraqi actions. These actions would require even more aircraft and would lead to the commencement of OPLAN 1003V. Of course, we also realized that any Iraqi actions that triggered a Blue or White response could escalate into a Red response, requiring coalition air power to contain the Iraqis until the required ground forces could be deployed.67

CENTAF staffers, assisted by planners from CENTCOM’s maritime component and from U.S. Air Forces in Europe (USAFE) headquartered at Ramstein, developed for each option a strategy that included a three-day MAAP, daily air operations directives (AODs), and an ensuing joint integrated and prioritized target list (JIPTL, pronounced “ji-pittle”) for each day. The MAAPs for each day in each of the three graduated options were detailed all the way down to individual target types, assigned weapons, scheduled times on target, and weapon aim-point placement.68

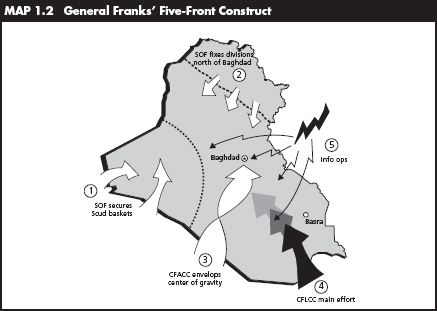

The following day, Franks traveled to Camp David for a lengthy planning session with President Bush and his senior advisers. CENTCOM’s commander proposed five notional invasion fronts: a western front dominated by SOF and air operations devoted to Scud hunting, a southern front consisting of the main axis of attack from Kuwait, an information operations front, a vertical attack on Baghdad by CENTCOM’s air component, and a northern front through Turkey if the Turkish government would permit it (see map 1.2).69

On June 3, 2002, Franks outlined the modified Running Start plan to Secretary Rumsfeld. This concept, which envisaged starting combat operations before all allied forces were in position, entailed using the Blue, White, or Red air employment options as might be needed to maintain pressure on Iraqi troops while allied ground forces were flowing into the theater. Rumsfeld was intrigued by this concept and directed Franks to refine it further. Franks also presented what he called his “inside-out” notion for dealing with the possible scenario of having to confront a “Fortress Baghdad” at the end of the campaign. Its core idea was for CENTCOM to disable Iraq’s command and control system and then to attack Republican Guard forces deployed nearest the capital first, to prevent them from concentrating in the center of Baghdad and hunkering down for a prolonged urban fight that would risk turning the city into a “Mesopotamian Stalingrad.”70 Attacks would then work from the center of the city outward to prevent any Republican Guard or Iraqi regular army troops from entering. (In connection with the inside-out approach, Franks noted that Republican Guard formations positioned within and around Baghdad would be vulnerable to precision air attacks.) Franks subsequently reconvened his component commanders at Ramstein on June 27–28 and directed them to shift their planning emphasis from Generated Start to Running Start.

Source: American Soldier

The initial seeds of 1003V envisaged a multipronged air-land attack into southern Iraq from Kuwait and into northern Iraq from Turkey, with heavy covert SOF involvement to pave the way before the formal start of the war. CENTCOM’s initial proposal called for about 250,000 ground troops, including 3 armored divisions. Under relentless prodding from Secretary Rumsfeld, however, that number was whittled down to 2 Army divisions and 1 Marine Expeditionary Force (MEF). The refined plan also placed greater reliance on precision bombing and close air-land coordination with both SOF and conventional ground forces.71 The plan underwent more than two dozen revisions before it was finally accepted in turn by Secretary Rumsfeld and President Bush.72 As attested by these progressively refined options, it was becoming clear that Franks was edging not toward a Desert Storm II–type force, but instead, in Woodward’s words, “toward a lighter, quicker plan that was more complex, with lots of moving pieces.”73

CENTAF’s main effort in support of this process in July 2002 entailed integrating key personnel from the Royal Air Force (RAF) into the emerging air options planning effort, thus embedding the RAF professionals who would soon serve with the British air contingent in the CAOC intimately into CENTAF’s planning staff at Shaw AFB. These allied staffers soon became completely enmeshed in the concurrent development of the joint air operations plan, the MAAP for the first three days of the campaign, and the JIPTL, as well as in associated planning for munitions requirements and for the bed-down of forces throughout CENTCOM’s area of responsibility. The initial RAF cadre also joined actively in the further refinement of the target list. This early cooperative work led to the development of deep and enduring trust relationships that paid off well when these same personnel later assumed key positions in the CAOC during the final fine-tuning and execution of OPLAN 1003V (see Chapter 4). Staffers from the Air Force Doctrine Center at Maxwell AFB, Alabama, also took part in a concurrent effort by CENTAF planners to consider the emerging air operations plan from a doctrinal perspective, particularly with respect to cross-command relationships and possible jurisdictional issues that might arise between CENTCOM and EUCOM for any forces that would operate out of Turkey.

On August 5, 2002, Franks and Renuart briefed President Bush and the National Security Council on Generated Start, Running Start, and a new concept called Hybrid Start that combined key elements of the first two. Generated Start still envisaged a 90-45-90 timeline. Running Start was a variation on Generated Start that envisaged a 45-90-90 timeline, with a forward flow of allied ground forces and no-notice aerial bombardment commencing simultaneously, followed by 90 days of “decisive combat operations” and 90 days more for complete regime takedown. Hybrid Start embraced four successive phases. Phase I envisaged 5 days to establish an air bridge to the region, including the mobilization of the Civil Reserve Air Fleet (CRAF) if need be, followed by 11 additional days to move allied forces forward. Phase II would entail 16 days of offensive air and SOF operations. Phase III envisaged 125 days of joint and combined major combat operations aimed at bringing down Hussein’s regime. Phase IV would entail postwar stability operations of an open-ended and unknowable duration.74

On August 6, 2002, Franks directed his component commanders to replace their focus on the Running Start concept with an emphasis on the faster Hybrid Start. Phase I of the latter plan entailed “preparation.” Phase II was called “shaping the battlespace.” Phase III was “decisive operations.” Phase IV was “posthostility operations.” Franks later recalled that he envisaged Phase IV as possibly lasting “years, not months,” and thought it “might well prove to be more challenging than major combat operations,” although those pronouncements came well after the postcampaign insurgency had already entered full swing.75

As General Franks continued to busy himself with these high-level coordination activities, General Moseley and his staff hosted a major warfighter conference at Nellis AFB, Nevada, during the week of August 5–9, 2002, that included representatives from CENTCOM, its subordinate components, the four services, and the United Kingdom. One agenda item entailed further refining CENTAF’s anticipated munitions requirements for the looming campaign within the context of CENTCOM’s recently evolved Hybrid concept of operations. Although the provision of munitions to joint warfighting commands is a service responsibility, CENTAF’s planners worked closely with their counterpart service representatives to ensure that General Moseley would have the full spectrum of needed weaponry from all services. Toward that end they organized a separate gathering of concerned parties aimed at brokering an interservice “munitions trade” to ensure that the munitions required to meet the air component’s needs would be on hand when the time came.76 Also during this conference, General Moseley’s counter-Scud working group, led by a team of experts from Air Combat Command headquarters at Langley AFB, Virginia, got down to work in earnest.77 A senior CAOC staffer later recalled of this crucial meeting that “key concepts of operations were either developed or refined, and relationships between and among the involved staffs were further strengthened.”78

CENTCOM planners identified December through February as the ideal time window within which to initiate the campaign’s formal combat operations. Iraqi ground force training was least intensive during that period and was conducted at the individual unit level rather than in larger and more cohesive formations. The period from December through March was also deemed to offer the best weather window because high winds and sandstorms typically commenced in March and April, with summer heat following soon afterward. Franks assumed that his troops would be fighting in hot and uncomfortable sealed garments to protect themselves against chemical and biological weapons. Because fighting in summer temperatures that could reach as high as 130° Fahrenheit was to be avoided at all costs, ground operations had to start no later than April 1.

On August 14, 2002, the president’s national security adviser, Condoleezza Rice, chaired a principals’ meeting to discuss a new draft national security presidential directive titled “Iraq: Goals, Objectives and Strategy.” This document stipulated that the overarching aim of the United States was to free Iraq from Ba’athist rule in order to eliminate its WMD and end threats by Iraq to its neighbors, utilizing all instruments of national power and with a coalition if possible, but alone if necessary. It stressed the need for any invasion plan to demonstrate that the American goal was to liberate rather than conquer Iraq and decreed that the underlying strategy must show that the United States “is prepared to play a sustaining role in the reconstruction of a post-Hussein Iraq.”79

That same day, Franks and Renuart again met with Rumsfeld, this time to discuss targeting. Concern over the need to avoid collateral damage at every reasonable cost led to the development of more than 4,000 target folders before the war started. CENTCOM also issued collateral-damage mitigation charts to all air operations planners detailing how specific weapons types should be employed against different kinds of targets to minimize unintended damage to adjacent structures such as homes and religious sites.80 That concern, the British national contingent commander, Air Marshal Brian Burridge, later recalled, “informed everything we did . . . from kinetic targeting through to the way in which we dealt with urban areas.”81 Out of those roughly 4,000 possible targets CENTCOM planners had identified 130 as entailing a high collateral-damage risk, defined as the likelihood that an attack would kill 30 or more Iraqi civilians. That number was expected to diminish after the application of collateral-damage mitigation measures by CENTCOM. Franks indicated that the proper servicing of 4,000 targets could require as many as 12,000 to 13,000 separate munitions for individual target aim points, because it could take from 4 to 12 munitions to achieve desired effects against some targets.82

The land component’s overall scheme of maneuver envisaged a two-pronged ground assault, with the Army’s V Corps pressing northwesterly from Kuwait through the Karbala gap and directly on to Baghdad, and the Marine Corps’ First Marine Expeditionary Force (I MEF) also attacking northwesterly from Kuwait into the Mesopotamian plain that lay between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers and ultimately joining up with the Army contingent as both simultaneously neared Baghdad. The plan was for both the Army and Marine Corps combat elements to bypass any cities that lay directly in the path of their advance to Baghdad, neutralizing with air power and long-range indirect surface fire any Iraqi forces that might be capable of ranging the highways before those forces were engaged head-on.

At that point in the planning, Secretary Rumsfeld concluded that the time had come for him to enlist the support of the JCS. He convened a meeting of the service chiefs at which the president, but not General Franks, was present. The Air Force chief of staff, Gen. John Jumper, indicated that in his judgment, CENTCOM’s emerging air plan was supportable and Iraq’s IADS could be overcome, but he expressed concern over the possibility that Iraq could jam the signals from the space-based GPS constellation of twenty-eight satellites in semisynchronous orbit on which allied navigation and satellite-aided joint direct attack munition (JDAM, pronounced “jay-dam”) weapon guidance depended. He warned that the Air Force’s air mobility assets would be stretched thin but could nonetheless handle any likely tasking by CENTCOM. Both he and the chief of naval operations, Adm. Vern Clark, questioned whether the participating services would have sufficient stocks of precision munitions. Admiral Clark further voiced concern that continuing operations in Afghanistan would mean two concurrent wars, which could impose an unusually demanding stress on aircraft carrier availability. But he too concluded that all tasks that CENTCOM might levy on the Navy’s carrier force could be accommodated.83

In September 2002 CENTAF planners visited each prospective air operating facility in CENTCOM’s area of responsibility to present a detailed air operations plan and to elicit reactions from the wing commanders at each base with respect to the plan’s supportability from their particular unit’s perspective. Planners from the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) also were embedded with the CENTAF staff at Shaw AFB for the first time. In addition, on September 19, another “huddle” between General Franks and General Moseley and their respective staffs was convened to consider proper materiel flow to ensure that the required force would be in place and ready for combat on A-day, the first day of full-fledged offensive air operations.

General Moseley hosted a “quick frag” convocation at Shaw AFB during the week of October 7–11 that included key planners from the CAOC’s strategy and combat plans divisions. The meeting also included representatives from CENTCOM’s maritime component and aviators from the 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing who would take part in the campaign. A major aim of that gathering was to update the airspace plan and SPINs, develop workable identification friend or foe (IFF) arrangements and procedures, refine the air defense plan for CENTCOM’s area of responsibility, and begin fine-tuning the database that would be used to manage the daily air tasking process. A subsequent exercise of a similar nature organized by CENTAF at Shaw on October 15–25 included participation by representatives from USAFE, the maritime components of both CENTCOM and EUCOM, Project Checkmate on the Air Staff, the RAF, and the RAAF. Subject-matter experts on the conventional air-launched cruise missile carried by the B-52 were also there, as well as experts on the B-2 and F-117 stealth attack aircraft. From these two sets of discussions emerged refined AODs, JIPTLs, and MAAPs for the first three days of planned combat operations.84

By early November 2002 the essential elements of the final war plan were in place. A Washington Post account reported that “the broad outlines are now agreed upon within the administration,” adding that several known aspects of the plan were being withheld from publication at the request of senior civilian and military officials in the Department of Defense. Those aspects included “the timing of certain military actions, the trigger points for other moves, some of the tactics being contemplated, and the units that would execute some of the tactics.”85 There were further reports that Kuwait had quietly sealed off a third of its territory for the use of American troops already deployed along the Iraqi border, that an effort was under way for U.S. aircraft to drop propaganda leaflets over Iraq urging Iraqi soldiers not to fight and to defect once the campaign began, that attacks against Iraqi IADS targets had been stepped up, and that CIA paramilitary units had already been inserted into northern Iraq to work with Kurdish resistance elements.86 (Thanks to the successful prior efforts of Operation Provide Comfort and Operation Northern Watch to keep Iraqi forces from attacking the Kurds from the air, the Kurds had managed to establish an autonomous political sanctuary in northern Iraq.) Franks was cautiously optimistic about the likely cost of the impending invasion in friendly lives, telling some on the CENTCOM staff that he anticipated fewer than one thousand coalition casualties, and probably only several hundred.87

General Moseley summoned a Red Team of experts from Air Combat Command to Nellis during the first week of November so that the team could be briefed on all aspects of CENTAF’s emerging air offensive plan.88 In addition to personnel from Air Combat Command, the Red Team also included appropriate subject-matter experts from USAFE’s 32nd Air Operations Group, the Navy’s Deep Blue staff, the Air Staff’s Project Checkmate, and other organizations. During the course of this meeting CAOC planners further fine-tuned the emerging MAAP for the first days of the impending air war. Because many of the Red Team invitees had by now been in-briefed on the emerging plan in full detail, General Moseley recruited them to join his battle staff.89

A related conference convened at Air Combat Command’s Air-Ground Operations School (AGOS) at Nellis starting on November 2 focused on refining CENTAF’s emerging concept of operations for kill-box interdiction and close air support (KI/CAS). Col. Matt Neuenswander, the AGOS commander at that time, later recalled that General Moseley directed the attendees to ensure that CENTAF’s emerging KI/CAS plan was both workable and in close harmony with the Army’s anticipated fire support needs. Among the main breakthroughs that emerged from this effort was a set of executable air-ground SPINs that enabled the fullest possible air-component support to engaged Army ground forces. Colonel Neuenswander later remarked that “General Moseley bent over backwards from the beginning to support the Army.”90 CENTAF’s rear air operations center at Shaw concurrently underwent an expansion of its already numerous campaign management functions and was staffed by most of the air component’s key planners and operators who would ultimately populate the forward CAOC at Prince Sultan Air Base. That effort provided yet another opportunity for the air component to dry-run the CAOC’s anticipated battle rhythm while at the same time building working and trust relationships within the CAOC.91

The final campaign plan aimed at seizing key objectives as rapidly as possible, which inevitably dictated concurrent air and ground operations. The plan also sought to keep Iraq from using WMD against coalition forces, firing ballistic missiles at Israel, and sabotaging its own oil fields, while simultaneously discouraging the regular Iraqi army from fighting and also making every reasonable effort to keep Iraq’s infrastructure intact. In Desert Storm such Iraqi infrastructure elements as electrical power generation, oil refineries and distribution and storage facilities, and transportation nodes—including bridges and rail junctions—had been attacked and destroyed on a substantial scale. CENTCOM was determined this time not to appear to be at war against the Iraqi people. The targeting of such infrastructure facilities during the first Gulf War had not achieved the intended goal of undermining Iraq’s immediate warfighting potential. Such assets were also included on the no-strike list to spare the United States the burden of having to rebuild them after the war and because the expected rapid success of the ground offensive did not require their destruction.92 Only command and control networks, regime security forces, select palaces, government ministries, command bunkers, counterair and countermaritime targets, and facilities associated with Iraq’s ability to produce and deliver WMD were to be struck in the air component’s initial “strategic” attacks.93 Offensive air operations this time were to be studiously effects based, seeking desired outcomes and not just attacking targets for the sake of destroying them.

CENTAF’s staff employed a strategy-to-tasks approach in accomodating these mission requirements. Targeting began with General Moseley’s operational objectives, such as achieving and maintaining air and space supremacy. Operational objectives led to tactical-level objectives, such as neutralizing Iraq’s IADS in order to mitigate its assessed threat potential. These tactical objectives drove such tactical tasks as destroying IADS command and control nodes by A+1 (the start of preplanned offensive air operations being A-day). The CENTAF staff assigned a desired effect to each tactical task (such as rendering the enemy’s IADS unable to coordinate a coherent air defense throughout the campaign’s major combat phase), a focus of effort (for example, on such key command and control enablers as the air defense operations centers, sector operations centers, and intercept operations centers), and a measure of physical achievement (for example, 100 percent of all targeted enablers destroyed). Each target aim point chosen was tied to a specific tactical task that could be traced back to General Moseley’s operational-level objectives, which supported General Franks’ operational objectives, which in turn supported the president’s strategic objectives.94

CENTAF’s planners spent most of 2002 and the initial months of 2003 studying Iraq first as a “system of systems,” then looking at candidate targets, and finally drilling down to the aim-point placement level, consulting experts from a variety of concerned national agencies who worked closely with CENTCOM’s intelligence and operations staffs. The Joint Warfare Analysis Center provided detailed targeting analysis of Iraq’s airfields and communications nodes, as well as empirically substantiated recommendations as to how best to attack certain hardened targets using particular warheads, impact angles, and impact velocities.95

Lt. Col. Mark Cline, a key participant in this process, recalled that “CENTAF’s planners and targeteers were figuratively tied at the hip for days at a time, producing several iterations of the first seventy-two hours of the air campaign from February 2002 all the way through the campaign’s commencement on March 19, 2003.” At a five-day conference in late January 2003, all of the concerned national agencies, CENTCOM’s intelligence and operations staffers, and cruise-missile operations planners reviewed every aim point associated with the most significant targets. This process was then repeated in-theater at the CAOC. “Simply put,” Cline said, “the placement of every aim point had a focused purpose.”96 In later characterizing this process in a press interview General Leaf observed: “We are working very hard to make the difficult intellectual leap to ask what it is we want to achieve instead of going right to the weapon, the platform, or the results in terms of rubble.”97

CENTAF developed a strategy that envisaged six parallel and concurrent air offensive missions: strategic attack, to include strikes against leadership, regime security and support, command and control, WMD and associated delivery systems, and the Special Republican Guard; air and space supremacy, to include disabling Iraqi access to space support and neutralizing the Iraqi air force and IADS; operations to prevent Iraqi theater ballistic missile launches and to destroy any targeted missiles that might attack Israel or Jordan; counterland operations and providing support to the land component commander by interdicting and destroying Iraqi ground forces and providing on-call CAS; supporting the SOF component commander by means of airlift, ISR, and on-call strike operations; and supporting the maritime component commander and achieving maritime supremacy by neutralizing Iraqi weapons that might threaten allied vessels and lines of communication in the Persian Gulf.98

With respect to the prodigious amount of jet fuel that would be required to sustain such large-scale air operations, General Moseley’s chief of strategy recalled:

One of the huge constraints that was imposed on CENTAF’s planners going into the initial workups for the air contribution to OPLAN 1003V was that we were not allowed to assume the availability of any provision of basing or fuel from Saudi Arabia. From the very beginning, we realized that this plan was not executable without Saudi basing and fuel, especially as the ever-evolving plan moved toward a near-simultaneous execution of air and ground operations. However, the Office of the Secretary of Defense kept this constraint on planning until the start of January 2003. Throughout the preceding months, CENTAF planners had continued to voice their concerns about the constraint until the Pentagon finally relented and gave General Moseley the go-ahead to seek basing and fuel from the Saudi government. The resultant short-notice permission granted by the Saudis for coalition basing in their country resulted in their having to contract thousands of fuel trucks to keep facilities such as Prince Sultan Air Base operating.99

As of January 2003, the overall campaign plan still envisaged 16 days of preparation (5 days to mobilize and establish an air bridge and 11 days to deploy the forces forward), followed by 16 days of shaping the battlespace (including continued SOF insertions and selective air-only attacks), leading into an anticipated 125 days of decisive offensive operations (including the start of major ground combat), and then a post-hostilities phase of unknowable duration.100 The concept of operations for the opening round was simultaneity in an aerial onslaught that envisaged 80 percent or more of the target attacks being carried out with precision-guided munitions. An Air Force planner predicted that the air employment strategy would be “highly kinetic.”101 The plan entailed the delivery of some three thousand precision-guided bombs and cruise missiles within the first forty-eight hours—ten times the number used during the first two days of Desert Storm—directed against enemy air defenses, political and military headquarters facilities, communications nodes, and suspected WMD delivery systems, followed quickly thereafter by the start of the allied ground offensive. That prospect promised an anticipated air campaign that many in the media soon came to characterize by the term “shock and awe,” an expression that had gained popular currency after Rumsfeld sent a note to General Franks in December 2002 suggesting that Franks and his planners at CENTCOM review a recent study bearing that title that maintained that precision weapons could neutralize an enemy’s command and control and thereby achieve “rapid dominance” in major combat.102

On February 5, 2003, Secretary of State Powell briefed the UN Security Council on the Bush administration’s many premises and assumptions regarding Iraq’s presumed WMD efforts. With CIA director Tenet sitting behind him, Powell laid out a raft of raw intelligence facts and figures, recited Iraq’s known UAV violations, alluded to indications of Iraqi links with Al Qaeda, and suggested that despite the contrasting religious fanaticism of Al Qaeda and secular nature of Saddam Hussein, “ambition and hatred are enough to bring Iraq and Al Qaeda together.”103 Powell argued for a UN resolution authorizing the use of “all necessary means” to prevent any such possibility from occurring. France and Russia, however, refused to endorse the stronger language. As always, Powell counseled caution. He later told President Bush privately that once Bush committed the nation to war, he would immediately become “the proud owner of 25 million people. You will own all their hopes, aspirations, and problems.” (Powell and Under Secretary of State Richard Armitage characterized this cautionary injunction as the Pottery Barn rule—if you break it, you own it.)104

Flowing the Forces

On November 26, 2002, nearly a year to the day after the president had asked Secretary Rumsfeld to get started on a war plan for Iraq, General Franks sent a mobilization deployment order to Rumsfeld for his approval. This was the first concrete step taken by CENTCOM toward implementing the planning that had taken place throughout the preceding year. The order directed an incremental movement of forces, including two Navy carrier battle groups, and notified all tasked units to prepare to deploy their forces forward to the war-zone-to-be. Rumsfeld responded: “We’re going to dribble this out slowly so that it’s enough to keep the pressure on for the diplomacy but not so much as to discredit the diplomacy.”105 The issuance of this initial deployment order represented one aspect of a two-pronged approach, one part diplomatic and the other military.106 The first deployment order approved by Rumsfeld was issued on December 6.

In January 2003, in one of the first major deployment moves for the impending invasion, Secretary Rumsfeld ordered the USS Abraham Lincoln carrier battle group to redeploy to the North Arabian Gulf from its holding area near Australia. The group was en route home from a six-month deployment in the Middle East but was directed to remain in CENTCOM’s area of responsibility as a contingency measure. The USS Theodore Roosevelt battle group, just completing a predeployment workup in the Caribbean, received orders to move as quickly as possible to reinforce USS Constellation, already in the Gulf, and USS Harry S. Truman in the eastern Mediterranean for possible operations against Iraq. A fifth carrier battle group spearheaded by USS Carl Vinson moved into the Western Pacific to complement two dozen Air Force heavy bombers that had been forward-deployed to Guam. U.S. Air Force F-15E Strike Eagles were sent to Japan and Korea as backfills to cover Northeast Asia as USS Kitty Hawk moved from the Western Pacific to the North Arabian Gulf. The USS Nimitz carrier battle group got under way from San Diego in mid-January, wrapped up an already compressed three-week training exercise, and headed for the Western Pacific. Finally, the USS George Washington battle group, which had just returned home to the East Coast in December following a six-month deployment in support of Operation Southern Watch, was placed on ninety-six-hour standby alert.107

The six carrier battle groups that were committed to the impending campaign were the core of a larger U.S. naval presence comprising 3 amphibious ready groups (ARGs) and 2 amphibious task forces (ATFs) totaling nearly 180 U.S. and allied ships, 80,800 sailors, and 15,500 Marines. The carrier battle groups were all under the operational control of Vice Adm. Timothy Keating, 5th Fleet’s commander and CENTCOM’s maritime component commander. Admiral Keating wrote that “never before in history [had] one naval force projected such a concentrated amount of firepower and technology in such a small geographic area, and not since World War II [had] a larger logistics force been assembled.”108 In late February Secretary of the Navy Hansford Johnson and the chief of naval operations, Admiral Clark, testified before the House Armed Services Committee that the Navy’s inventory of precision-guided munitions (PGMs) had been replenished since the drawdown that had resulted from major combat operations in Afghanistan and that the six forward-deployed carriers were adequately stocked for a possible conflict with Iraq. “Two years ago,” Clark told the committee, “I could not have deployed the force structure I have out there and be in the green across the board.”109

In yet another indication of ongoing preparations for major combat, the Air Force canceled its regularly scheduled bimonthly Red Flag large-force training exercise at Nellis AFB planned for the second week of January 2003 after its 4th Fighter Wing, an F-15E unit based at Seymour Johnson AFB, North Carolina, and the designated lead wing for that exercise, received deployment orders to CENTCOM’s area of responsibility.110 Two months later, the next scheduled Red Flag exercise was also canceled because at least 50 percent of the more than two thousand slated participants, many of whom were from the designated lead unit, the 48th Fighter Wing at RAF Lakenheath in the United Kingdom, could not marshal the assets needed for transportation to Nellis.111 Throughput figures at Rhein-Main Air Base, Germany, for the months of January and February 2003 attest to the increased flow rate of U.S. military personnel being airlifted to Turkey, Qatar, and elsewhere in Southwest Asia. C-17 transports averaged 30 to 35 transits a day, two-thirds of which were bound for Turkey and Southwest Asia. The ramp activity at Rhein-Main, which one official there characterized as “staggering,” saw upward of 32,000 passengers, or about 2,000 a day, in just the first half of February, up from a flow of only 10,000 passengers a month the previous November.112