CHAPTER 6

RUN SAFE AND INJURY FREE

When Melissa Althen was pushing her youngest son in a stroller around the neighborhood, she was amazed by what she noticed.

Now she takes precautions. She sticks to neighborhood roads instead of busy streets; she plans her runs for times when traffic is light, like dawn; she always runs against the flow of traffic; and she looks in all directions several times when crossing the street or a parking lot entrance.

Althen isn’t alone. In a poll on the Web site runnersworld.com, 50 percent of people said that they’d had close encounters with cars. Here are a few rules you can follow to stay safe on the roads.

Leave word. Tell somebody or leave a note at home saying where you plan to go and how long you plan to be out. That way, your loved ones will know to come look for you if they need to.

Identify yourself. Run with proper ID and carry a cell phone with emergency contacts taped to its back.

Pretend you’re invisible. Don’t assume a driver sees you. In fact, imagine that a driver can’t see you, and behave accordingly.

Face traffic. It’s easier to see, and react to, oncoming cars and other vehicles. And motorists will see you more clearly, too.

Make room. If traffic gets heavy or the road narrows, be prepared to move onto the sidewalk or shoulder of the road.

Be seen. Wear high-visibility, brightly colored clothing. When out near or after sunset, reflective materials are a must. (If you don’t own reflective clothing, a lightweight reflective vest is a great option.) Use a headlamp or handheld light so you can see where you’re going and drivers can see you. The light should have a bright LED (drivers see blinking red as a hazard).

Make sure you can hear. The safest option is to avoid wearing headphones so you can hear approaching vehicles. But if you do use headphones, run with the volume low and just one earbud in.

Understand the conditions. Factors like sun glare can interfere with drivers’ ability to see you.

Beware of trouble spots. Steer clear of potential problem areas like entrances to parking lots, bars, and restaurants, where there may be heavy traffic.

Watch for early birds and night owls. At odd hours, be extra careful. Early in the morning and very late at night, people may be overtired and not as alert and as careful to avoid people who are on foot.

Mind your manners. At a stop sign or light, wait for the driver to wave you through—then acknowledge with your own polite wave. That polite exchange will make the driver feel more inclined to do it again for the next walker or runner. Use hand signals (as you would on a bicycle) to show which way you plan to turn.

Working Out in the Heat

A lot of people decide to start working out once the weather warms up. And it’s easy to understand why. More daylight before and after work means more time to get outside. What’s more, with vacations, it’s easier to be more active in the summer. That said, there are plenty of obstacles to running in warm-weather months. Heat can make the same distance and pace feel harder than they do in cooler conditions. And a variety of heat ailments, from sunburn and chafing to heat stroke, can make for some serious discomfort. Here’s everything you need to know to stay safe, healthy, and happy when you’re working out in the heat.

Get fit first. Make sure that you’ve been exercising regularly for 4 to 6 weeks before you start doing any workouts in the heat, says Douglas Casa, PhD, who heads the Korey Stringer Institute at the University of Connecticut, which studies heatstroke and other causes of sudden death in sports. “The most important thing is to get fit first,” says Casa. “The heat is basically another stress, just like the exercise. So if you’re unfit and you start exercising in the heat, it’s like throwing two swords at you at the same time.” When you get fit, he explains, you’re increasing blood volume, sweating more (so you’re able to more efficiently cool off your body), and developing a higher stroke volume (which means that each heartbeat is pumping more blood out to the body), so your heart rate doesn’t have to go as high during your workout. “All of these ways that you get in shape are going to be vital when you start working out in the heat,” he says. “When you’re introducing the unique stress of exercise, adding the extra stress of heat is a lot to handle.”

Listen to your body and back off! If you don’t feel well—whether you have a headache, feel nauseous, or the workout just feels harder than usual—always back off. If you’re running hard, go easy. If you’re running easy, walk. If you’re walking, then stop and get in the shade. “Listen to your body, lower your intensity, and have fluids available when you need to hydrate,” says Casa.

Stay hydrated. Dehydration can make you more prone to heat illnesses, so it’s important to keep your thirst quenched. When you don’t drink enough, “your blood volume drops, so your heart has to work harder to power your muscles and keep you cool,” says Casa. As a result, the workout is going to feel tougher and likely be slower. Stay hydrated throughout the day and drink low-calorie sports drink when it’s hot outside. If your urine is pale yellow, then you’re well hydrated. If it’s darker—say the color of apple juice—drink more. If it’s clear, back off. Use thirst as your guide; experts have established that thirst will guide you to drink when you need to. “If you stay hydrated, that’s going to keep your body temperature lower in the heat,” says Casa. “You’re going to be safer and feel better.” During intense exercise in the heat, your body temperature rises about half a degree Fahrenheit for every 1 percent of body mass you lose through sweat. So if you’re 4 percent dehydrated, your core temperature is going to be about 2 degrees higher. “When you are well hydrated, you’ll recover better from exercising, and you won’t have to worry about rehydrating as much at the end of the workout.” (For more, see “Hydration.”)

Give yourself time to adjust to the heat. Don’t do long or higher-intensity workouts during the heat of the day. If you must do a high-intensity run at midday, pick routes with shade or do them indoors.

Start outside workouts in cooler conditions in the winter, fall, or spring; in shady areas; at the coolest time of day; or at a gym, says Casa. Once you’ve done that, you’ll be ready to start exercising in the heat. It can take 7 to 10 exercise sessions over the course of a couple weeks to adjust to the heat. But even then, “don’t do the hardest workout in the hottest time of day,” says Casa. “Keep it easy when it’s hot; go hard during cooler parts of day.”

Dress for the occasion. Wear apparel that’s light in color and lightweight with vents or mesh. Microfiber polyesters and cotton blends are good fabric choices. Also be sure to wear a hat, sunglasses, and sunscreen with an SPF of 30 or higher.

Watch your alcohol and meds. Alcohol, antihistamines, and other medications can have a dehydrating effect. Using them just before a run can make you have to pee, compounding your risk of dehydration. Talk with your doctor about how these medications may impact your running.

Be patient. Give yourself 8 to 14 days to acclimatize to hot weather, gradually increasing the length and intensity of your training. In that time, your body will learn to decrease your heart rate, decrease your core body temperature, and increase your sweat rate.

Seek grass and shade. It’s always hotter in cities than in surrounding areas because asphalt and concrete retain heat. If you must run in an urban or even a suburban area, look for shade—any park will do—and try to go in the early morning or late evening.

Check the breeze. If possible, start your run going with the wind and then run back with a headwind. Running into the wind has a cooling effect, and you’ll need that in the second half of a run.

Head out early or late. Even in the worst heat wave, it cools off significantly by dawn. Get your run done then and you’ll feel good about it all day. Can’t fit it in? Wait until evening, when the sun’s rays aren’t as strong—just don’t do it so late that it keeps you from getting to sleep.

Run in water. Substitute one weekly outdoor walk or run with a pool-running session of the same duration. If you’re new to pool running, use a flotation device and simply move your legs as if you were running on land, with a slightly exaggerated forward lean and vigorous arm pump. (For pool-running workouts, see this page.)

CLOSE ENCOUNTERS WITH MEAN DOGS

When Mandy Hubbard started running, she had an awesome paved loop she loved to do. Then one day, she looked up and found a huge English mastiff barking at her. She swung wide to give him his space, but he bolted toward her from the open gate to his driveway.

“I skidded to a stop, slowly backed up, but the dog continued toward me, barking,” she says.

She stared toward the ground and kept backing up, but the dog kept coming and brought along his buddy. “I thought, ‘I am so screwed.’” The dog finally stopped, and she kept backing away until she was far enough away that she could turn and run. She hasn’t run that route since.

Maybe it’s happened to you, or perhaps it’s just your greatest fear: A barking dog comes racing at you unleashed. “Typically, a dog who is aggressive is doing it more out of fear than anything else,” says Maui-based dog trainer and runner Jt Clough. “When you just tell it what to do, it will back down.” Follow these tips from Clough on handling an encounter with a dog when you’re on the run.

KEEP YOUR DISTANCE. On many occasions, the dog is not going to attack you—it’s just guarding its property, says Clough. Chances are, as long as you don’t approach, the dog will stop barking and go back home.

CROSS THE STREET. If you hear a dog barking up ahead, cross the street. Most dogs won’t cross the street to chase you, because they know the danger of getting hit by a car.

TELL THE DOG, “SIT!” Even the most untrained dog typically understands this simple command. “Typically, that’s the one thing they’ve been taught,” says Clough.

KNOW THE TERRITORY. Scout out any new routes for loose dogs before you head out on it alone. The “surprise factor” is a big part of what can make these encounters so frightening, says Clough.

DON’T RUN EMPTY-HANDED. Take a water bottle to spray a dog with water if necessary, says Clough. You can throw a water bottle in the dog’s direction—just to distract it and diffuse its aggression, not to hit it, she says. “Try to entice the dog to go after something other than you,” says Clough, “while using a low, authoritative voice to command them away by saying something like ‘Go get it!’”

DON’T GET EMOTIONAL. If you cower or jump when you see the dog and your voice gets screechy, the dog will go into attack mode, Clough says. “Dogs pick up on emotion before anything else.” Get authoritative, drop your voice, and say ‘Go get on home’ like you mean it,” she suggests. “If you get hysterical, they’re going to come after you,” she says.

KNOW THE SIGNS. When you’re startled by the loud bark of a dog, it can be hard to tell if it’s just saying a rather loud “hello” or if it’s ready to attack. Signs that the dog is about to charge include:

• A stiff, pointed tail

• Raised hair, particularly behind the shoulders and neck

• Snarling

• Baring teeth, with lip raised on both sides

DON’T RUN AWAY. “If you think you’re going to outrun the dog, that’s a mistake,” says Clough. “They will catch you.”

DON’T STARE. Keep the dog in the corner of your eye, be aware of what it’s doing, and back away from it. If you turn your back and take off, it’s highly likely the dog will run after you.

PUT OUT YOUR HANDS AND FEET. If you come across a really unruly dog or you’re seriously worried about an attack, put your hand or foot out in front of you, just as you would to protect yourself if a person lunged at you. Drop your voice and be authoritative.

HOW HEAT CAN HURT

Take steps to prevent the following hot-weather illnesses.

HEAT CRAMPS

• Cause: Dehydration leads to an electrolyte imbalance.

• Symptoms: Severe abdominal or large-muscle cramps

• Treatment: Restore salt balance with foods or drinks that contain sodium.

• Prevention: Don’t run hard in the heat till acclimatized and stay well hydrated with sports drink.

HEAT FAINTING

• Cause: Often brought on by a sudden stop that interrupts bloodflow from the legs to the brain.

• Symptoms: Fainting

• Treatment: After the fall, elevate legs and pelvis to help restore bloodflow to the brain.

• Prevention: Cool down gradually after a workout with at least 5 minutes of easy jogging and walking.

HEAT EXHAUSTION

• Cause: Dehydration leads to an electrolyte imbalance.

• Symptoms: Core body temperature of 102° to 104°F, headache, fatigue, profuse sweating, nausea, clammy skin

• Treatment: Rest and apply a cold pack on head/neck; also restore salt balance with foods and drinks with sodium.

• Prevention: Don’t run hard in the heat till acclimatized and stay well hydrated with sports drink.

HYPONATREMIA

• Cause: Excessive water intake dilutes blood-sodium levels; usually occurs after running for 4 or more hours.

• Symptoms: Headache, disorientation, muscle twitching

• Treatment: Emergency medical treatment is necessary; hydration in any form can be fatal.

• Prevention: When running, don’t drink more than about 32 ounces per hour; choose sports drink over water.

HEATSTROKE

• Cause: Extreme exertion and dehydration impair your body’s ability to maintain an optimal temperature.

• Symptoms: Core body temperature of 104°F or more, headache, nausea, vomiting, rapid pulse, disorientation

• Treatment: Emergency medical treatment is necessary for immediate ice-water immersion and IV fluids.

• Prevention: Don’t run hard in the heat until acclimatized and stay well hydrated with sports drink.

Sun Safety

When you’re exercising outside in the summer, some of the biggest discomforts you may encounter may have nothing to do with how hard your muscles were working but instead how much you’ve exposed your skin to the sun’s searing rays. “You run to be healthy, but all that outdoor time is not so great for your skin,” says Brooke Jackson, a Chicago-based dermatologist and runner. “You need to do what you can every time you run to protect yourself. Alittle bit each time will benefit you in the long run!” Here are Jackson’s tips on how to stay safe in the sun.

Preventing Sunburn

• Avoid running between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m., when the most potent ultraviolet rays shine.

• Wear a hat and sunglasses to protect your face and eyes.

• Avoid running shirtless; your clothes offer protection from the sun.

• Look for running shirts and shorts that offer UV protection or wear darker colors, which block more UV rays than light colors do.

• Use a sunscreen with an SPF of 30 or greater. It should be labeled “broad spectrum,” which means it will protect you from both UVA and UVB rays.

• Apply enough sunscreen to fill up a shot glass to cover your entire body before you go outside.

• Apply sunscreen at least 20 minutes before you go out so it has time to absorb into your skin. Reapply once each hour that you’re outside.

• If running with others, offer to spray one another’s backs. This area often gets missed because it’s difficult to reach and apply sunscreen to your own back.

• Use a lip balm with SPF; men in particular have a higher risk of sunburn on the lips than women do.

YOUR SKIN CARE KIT

When you’re going out for a warm-weather workout, stash these supplies in your gym bag or car.

• BODYGLIDE OR VASELINE: Prevents chafing and blisters

• ANTIBIOTIC OINTMENT: Keeps chafing wounds and popped blisters from getting infected

• SUNSCREEN: Prevents sunburn. Apply sweat-proof formulas with a broad spectrum SPF of at least 30. Reapply each hour that you’re outside.

• MOLESKIN: Covers hot spots to prevent blisters from developing

• ANTIFUNGAL POWDER OR SPRAY: Helps prevent athlete’s foot

• ALOE VERA: Soothes sunburn

Treating Sunburn

• Get inside to cool off.

• Apply a cold compress or some refrigerated aloe.

• Take a cool shower or soak in an oatmeal bath.

• Take an over-the-counter pain reliever like Tylenol to relieve discomfort.

• If the burn is severe enough to develop blisters, you might be susceptible to infection, so it’s best to see a dermatologist.

• Stay away from gels, which are alcohol based and can further dry out the skin. Moisturizer works just as well.

• If you develop blisters covering a good portion of your body or face, or start to get chills, go to the emergency room for treatment.

You should also keep an eye out for skin cancer. Studies have shown that marathoners and outdoor athletes have a higher risk for all skin cancers.1

• Know what your moles look like.

• Look for any changes in size or color.

• A pimple, scratch, or bug bite should heal within a week. If it’s not healing, or it’s bleeding or growing, see a dermatologist.

• Get an annual skin cancer screening by a dermatologist who can examine the nuances and pick up early warning signs.

• If you have a history of skin cancer, get checked every 6 months.

CHAFING

Skin-to-skin and skin-to-clothing rubbing can cause a red, raw rash that can bleed, sting, and make you yelp during your postrun shower. Moisture and salt on the body make it worse. Underarms, inner thighs, the bra line (women), and nipples (men) are vulnerable spots. To help prevent it, wear moisture-wicking, seamless, tagless gear. Fit is important—a baggy shirt has excess material that can cause irritation; a too-snug sports bra can dig into skin. Apply Vaseline, sports lube, Band-Aids, or NipGuards before you run. To treat chafing, wash the area with soap and water, apply an antibacterial ointment, and cover with a bandage.

Working Out in the Cold and Snow

Winter can be a challenging time to stick to an exercise routine, and not just because of the weather. Aside from the ice, slush, snow, and far fewer hours of daylight to get those workouts in, you have to juggle it with holiday and family commitments.

So it can be easy to let things slide. Below you’ll find all the strategies you need to stay fit until spring, when daylight hours and temperatures are more agreeable.

Warm up inside. Before you head out the door, move around indoors enough to get the blood flowing and gradually raise the heart rate, without breaking a sweat. This will help your workout feel easier sooner. Run in place, walk up and down your stairs, do some jumping jacks, use a jump rope . . . whatever it takes to get warmed up.

Head into the wind. If you can, start your walk or run facing the wind and finish with it at your back. Otherwise, you’ll work up a sweat and then turn directly into a cold blast. Not fun! To avoid a long, biting slog, you can break this into segments, walking or running into the wind for 10 minutes, turning around to walk or run with the wind at your back for 5 minutes, then repeat.

Run with others. Exercising with a friend even once a week can help you get out the door, as it’s harder to blow off a workout if you know that someone is waiting for you. And you don’t necessarily have to run or walk. Making dates to lift weights at the gym or take a yoga or Pilates class can help you stay on track with these activities.

Stay visible. When the days are short, you’re more likely to be walking or running in the dark. Wear reflective, fluorescent gear and use a headlamp or carry a flashlight so you can see where you’re going. (As always, remember to walk or run against the flow of traffic.)

Forget about pace. Snow and ice-covered roads can be tricky. When you do run or walk, don’t worry about how fast or slow you’re going. Just focus on getting in time on your feet, enjoying some fresh air, and getting home safe. Get into a rhythm that feels easy and comfortable.

Find stable footing. Look for snow that’s been packed down—it will provide better traction. Fresh powder can cover up ice patches. Run on the street if it’s been plowed, provided that it’s safe from traffic, and watch out for areas that could have black ice. Use the sidewalk if it’s clear of ice and slippery snow. Find a well-lit route, slow down, and make sure you’re familiar with areas of broken concrete. Use products like Yaktrax to reduce your risk of falling.

Take short steps. When you’re running on ice or snow, shorten your stride to help prevent slipping and falling.

Be flexible. Winter is not the time to be rigid about when, where, and how far you go. If you’re a morning exerciser, you may need to switch to lunchtime workouts, when the air is warmest and the sun is out; if you usually hit the trails, you may need to stick to well-lit roads or even the treadmill.

Run indoors. If the roads are covered with ice, it’s better to exercise inside than risk hurting yourself. (See this page for tips on working out on the treadmill.) The treadmill doesn’t have to feel like torture. Play around with the speed and incline to fend off boredom. Most treadmills come with preprogrammed workouts that do the changing for you, so try those, too. If you can’t bear the treadmill, use the elliptical trainer or stair machine or “run” in deep water for the same amount of time that you’d spend running.

Get dry and warm postrun Damp clothing increases heat loss. Immediately after your workout, remove your sweaty clothes and get into a hot shower—or, if you aren’t ready for a shower, slip into something dry and warm.

Don’t forget to drink. Even when it’s cold, you lose water through sweating. So it’s important to stay hydrated throughout the winter. Drink half your weight in ounces throughout the day (e.g., if you weigh 150 pounds, aim for 75 ounces of fluids per day).

Dressing for Cold-Weather Workouts

Cover your extremities. Your nose, fingers, and ears are the first to freeze, so be sure to keep them well protected from wind, wet, and freezing temperatures. Balaclavas—knit masks that cover the whole head, with holes for nose and eyes—are the way to go. Or try a heavy synthetic knit cap pulled down low, with a scarf or neck muffler pulled up high.

Wear wool. Wool retains much of its insulating properties even when it’s wet, thanks to air pockets in the fiber that trap warm air. Socks made from merino wool won’t make your feet feel itchy.

Protect your private parts . . . Wind robs your body of heat. That’s why briefs or boxers with a nylon wind barrier are so important for guys on cold days. The nylon panel on the front keeps the wind out.

. . . and your hands. Mittens keep your hands warmer than gloves by creating a big, warm air pocket around your entire hand. Pick a pair with a nylon shell or wear glove liners underneath. If your hands start to feel numb and look pale, warm them as soon as possible, as these are early signs of frostbite.

Wear a shell. On wet days, look for a shell that will not only keep you dry and protected from the snow or sleet but will also vent the moisture you create as you sweat. Many jackets are made from waterproof, breathable fabrics and have large mid-back and underarm vents.

When Winter Weather Becomes Dangerous

As long as you’re dressed for the conditions and continuing to move (at least 60 percent of maximum heart rate, or roughly equivalent to your easy level of effort), you can produce enough body heat to offset the cold. Still, when it is severely cold, be sure to watch out for these two dangerous conditions, hypothermia and frostbite

• HYPOTHERMIA: Hypothermia strikes when your body loses more heat than it can produce and your core temperature falls below 95°F (35°C). Symptoms can vary widely but typically start with shivering and numbness and progress to confusion and lack of coordination. You’re most at risk when it’s rainy or snowy and your skin is damp. That’s because water transfers heat away from your body much more quickly than air.

• FROSTBITE: Frostbite happens when the skin temperature falls below 32°F (0°C) and most commonly strikes the nose, ears, cheeks, fingers, and toes. It can start with tingling, burning, aching, and redness, then progress to numbness. Windy and wet days are the riskiest times for frostbite. When the wind chill falls below –18°F (–27°C), you can develop frostbite on exposed skin in 30 minutes or less.

Side Stitches

Many runners find that the big problem when they start running has nothing to do with their legs—it’s their lungs: They can’t catch their breath, or they get side stitches.

If you are having problems breathing, consult with your doctor first to rule out any medical issues. Asthma or exercise-induced asthma and allergies are very common; wheezing and feeling like you can’t catch your breath can be common symptoms of those conditions.

Side stitches—a sharp pain in the right side, immediately below the ribs—are considered a muscle spasm of the ligaments that support the diaphragm, a muscle associated with breathing, says Susan Paul, an exercise physiologist and Runner’s World’s “For Beginners Only” columnist.

Like other muscle cramps or spasms, diaphragm spasms or side stitches are thought to occur from the strain and fatigue associated with working and breathing harder. As your overall conditioning improves, muscles tend to get less tired, and side stitches tend to go away, too.

Some research indicates that side stitches may also be related to running posture. In a 2010 study published in the Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport,2 side stitches were more common in runners who slouch over or hunch their backs. So improving your posture by strengthening your core may help the side stitches go away.

CATCHING YOUR BREATH

Going about your everyday life, you don’t think much about breathing. It happens automatically, so unless something interferes with your inhale and exhale, you don’t have to. But many people find that when they start working out, they get out of breath quickly.

Budd Coates, coach, exercise physiologist, and senior director of employee fitness and health at Rodale, developed a system of controlling your breathing—and preventing injury—called rhythmic breathing. He has used this program to help scores of runners—many of them beginners—breathe easier and stay injury free. You can read more about rhythmic breathing in his book, Running on Air.

The more air you inhale, the more oxygen is available to be transferred through your circulatory system to your working muscles. Many people breathe from their chest and take in less oxygen. The chest muscles (the intercostals) fatigue sooner than the diaphragm. That’s why it’s a good idea to learn how to breathe from the belly. Here’s how.

• Lie down on your back.

• Keep your upper chest and shoulders still.

• Focus on raising your belly as you inhale.

• Lower your belly as you exhale.

• Inhale and exhale through both your nose and your mouth.

You can also practice this sitting, standing, and during the activities of your everyday life.

Asthma

When B.J. Keeton started working out, the soreness in his legs was expected. After all, he weighed 310 pounds and had been sedentary all his life. But what he didn’t expect was the metallic taste in his mouth, and the breaths that would feel cold in his chest. “I felt like a weight was sitting on my chest as I ran,” he says. “I would start to cough and wheeze, and there’d be a lot of excess mucus I’d be coughing up for hours afterward, and a metallic taste I couldn’t get rid of.

“It wasn’t uncommon for me to be out of breath walking from my car to my office,” he says. “If I did anything to get my heart rate up, I’d be worthless for the rest of the day.”

His doctor diagnosed him with exercise-induced asthma.

Though his doctor didn’t limit his activities at all—just advised him to take along his Albuterol inhaler—he was hesitant to keep working out at first.

“Mainly, I was scared I would collapse with no one around and suffocate,” he says. And the lingering effects—having a hard time breathing after exercising—“made me feel like being active wasn’t worth suffering through the side effects.”

It can take a while before breathing on the run feels like second nature. Many people go out so hard that they huff, puff, and end up with a side stitch a few minutes into the run. It can take time to get into a rhythm that feels natural and comfortable enough to hold a conversation.

But if you keep working out and find that you consistently wheeze, cough, feel a tightness in your chest, or just can’t catch your breath when you run, you might have asthma, a condition where the tubes that bring air in and out of your lungs tighten, says Dr. Stanley Fineman, founder of the Atlanta Asthma and Allergy Clinic. Asthma can be triggered by allergies, infections, and other substances like mold, pollen, and pet dander. And some people have exercise-induced asthma (EIA), in which the symptoms are triggered by, well, exercise. With EIA, you may start to wheeze, cough, and have difficulty breathing about 8 to 10 minutes into a workout, says Fineman.

Typically, air will be warmed and moistened when it’s inhaled through the nose. But when you’re running, or exerting yourself through any exercise, you tend to breathe more rapidly and breathe through your mouth, says Clifford Bassett, a New York University–affiliated allergist who is the medical director of New York Asthma and Allergy Care of New York. When this happens, cold, dry air gets to the airways and lungs, and this can trigger asthma symptoms. Many people with asthma tend to be particularly sensitive to substances like seasonal pollens and indoor allergens (like cat dander and dust), grass, and air pollutants (like ozone and smoke). So running outside, exposed to those substances for a long period of time, may create a greater risk of an asthma attack, particularly in a more sensitive individual.

But that doesn’t make it a good excuse to hang up your running shoes. Fineman says he encourages those with asthma to exercise.

“It builds lung capacity and improves overall quality of life,” he says. “I see asthmatics who are competitive runners all the time and manage their symptoms. I think the main thing is to make sure you have a good diagnosis, check your lung function, find out what the triggers are, and make sure you have an asthma management plan once you start an exercise program.”

Indeed, that’s what Keeton found. He started walking, then running, and shed 145 pounds from his 310-pound frame. His doctor prescribed an Albuterol inhaler, from which he takes two puffs 15 to 20 minutes before he runs. Since he’s been doing that, he hasn’t had a single attack. When running in moderate weather, he doesn’t even use the inhaler. But in extreme heat, cold, or humidity, he keeps it handy or takes a few puffs before he heads out.

“Exercise has completely changed my exercise-induced asthma,” says Keeton, an English professor and author from Lawrenceburg, Tennessee. “Before starting to run, I had very little endurance because of my diminished lung capacity. But now, as long as I’m staying active, I don’t have any problems.” And now he is training for a half-marathon. “I’ve started telling people that you can’t beat having EIA, but you sure can outrun it.”

Here are some tips for managing asthma symptoms with your running life. For more information, please contact the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (acaai.org).

Get tested. Asthma and allergies can develop at any age. But cases often go undiagnosed because some of the symptoms—like coughing during exercise in the case of allergies or shortness of breath in the case of asthma—are so common to so many other ailments. “If you’re having shortness of breath, it’s important to get an accurate diagnosis,” says Fineman. Be sure to note how often and in what settings you have the symptoms and how severe they are. When you get tested, you will be given a variety of lung function tests including spirometry, which assesses how much air you can exhale after a deep breath and how fast you can breathe out, and a peak flow test, which measures how hard you can breathe out. For allergies, you will likely get a variety of blood or skin tests, where a small amount of an allergen (like mold or grass) is placed on or below the skin to test for a reaction.

Warm up and cool down. This has been known to reduce symptoms. It helps the body more efficiently deliver oxygen to the working muscles.

Have a plan. If you do have asthma, create an asthma management plan with your doctor. Some people need to take maintenance medications a few times a day, bring rescue inhalers with them on runs, or both, says Fineman. Others are prescribed fast-acting medicines like an Albuterol inhaler, which relaxes the muscles around the airways.

Know your prime times. Avoid running outside when pollen and mold counts are at their highest. You can get daily alerts about local pollen and mold levels from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (aaaai.org). If you can’t avoid your triggers, or if the air is particularly cold and dry, hit the treadmill. Avoid workouts when you have a viral infection, temperatures are low, or pollen and air pollution levels are high. Warm and somewhat humid air is generally more tolerated than cool, dry air.

Cross-train. Swimming, walking, cycling, and hiking are good cross-training activities for those with asthma. Swimming helps strengthen the upper body, and swimmers are exposed to warm, moist air during the workout. Swimming also helps strengthen upper-body muscles.

Breathe through your nose. Breathing in and out of your nose—rather than your mouth—allows air to be warmed and humidified before it reaches your airways, which can prevent an attack. Wearing a face mask or balaclava in cold conditions also warms the air you inhale.

Keep it steady. Sudden bursts of activity are more likely to provoke asthma attacks than continuous efforts. So maintaining a steady pace could help you avoid an attack.

Stay hydrated. Start by getting hydrated with H20 and low-calorie sports electrolyte drinks before, during, and after a workout, says Bassett. This is particularly important when it’s hot outside. Good hydration may help prevent the airways from getting too dry and shutting down, causing an asthma attack. For more information, you can visit allergyandasthmarelief.org.

How Running Changed My Life

Running helped Chris Keating manage his epilepsy and regain his independence

Chris Keating had a charmed childhood. He played three varsity sports, made straight A’s, and held down a part-time job. But when he was 15, that all changed. In a wrestling tournament, he hit his head and had his first seizure.

He started having up to six seizures a week. Each one would last from 5 to 25 minutes. “My self-esteem quickly diminished,” he says. “I could barely even tell if I had any left.”

He lived at home throughout college, so his parents could drop him off and pick him up.

Through it all, the seizures drained him, and so did the medications he took to manage them. To get his driver’s license, he had to go 6 months without a seizure. He was 20 before that happened. But shortly after he got the license, he had another seizure and had to wait another 6 months to drive again.

“Learning to cope with not being able to participate in the social norms has been a huge obstacle,” he says.

After losing his license for the third time, Keating vowed to find some independence. Doctors had suggested that exercise could reduce seizures.

He started cycling everywhere he wanted to go, to class or to the grocery store. He started running 13.1 miles to class each day.

A month after he started, Keating finished his first sprint triathlon, then a half-marathon. Now he has completed two half-marathons and a marathon. He’s had fewer seizures and struggles less with the side effects of medications. “My energy levels are higher and I have fewer mood swings that are not as drastic.”

What’s more, running “has given me an escape and a way to find myself,” he says. “There is no one to tell me I can’t. And nothing can stop me.”

AGE: 23

HOMETOWN: Dawsonville, Georgia

OCCUPATION: Full-time Nike+ Athlete at Nike Factory Store

What was the biggest hurdle, and how did you get over it? The hardest thing for me to get over was the side effects of the medications I am taking. With every medicine change, I would have to start over. After I took my medicine, I would become extremely tired and almost pass out; it took everything I had to get out the door and start running or biking. I viewed this as a mental block, not a physical hurdle, so I used this as a time to work on my discipline. I began to structure my daily schedule around my workouts and would wake up at 5:30 every morning to start my day. This helped me learn how to persevere, and how to make a schedule and stick to it, no matter what.

What precautions do you have to take while running to manage your epilepsy? The main precautions have to do with my diet and my sleep. I make sure I get at least 8 hours of sleep a day. If I don’t, I take a nap to make up for it. I also don’t run on days that I feel sluggish in any way. If I feel anything out of the ordinary, like tingling fingers, migraines, or any possible preseizure signs, I rest. On those days, if I do run, I’ll just run a very short distance on a track or a nearby 1-mile loop, and I will have my mom or dad watch me for a little while. Also, I always wear my RoadID, which states that I am epileptic, and I carry my medicine and cell phone with me with directions on how to administer it. I try to remain as hydrated as possible so that I don’t self-induce a seizure. I always carry water and Gatorade chews when I run.

What advice would you give to a beginner? Don’t stop, whatever you do. Don’t get discouraged, because results don’t happen overnight; it takes time, motivation, determination, and inspiration to keep going.

What advice would you give others who have epilepsy and would like to start running? Consult your doctor first. Honestly, epilepsy can hold you back in a lot of ways. It can wear out you and your family members or close friends. But it can only wear you down if you let it. When you’re running, everyone is equal. It doesn’t matter how fast you are or how far you run. It just matters that you put on your shoes and walk out your front door. Running instills confidence, and it provides a way to cope with life’s struggles.

Favorite motivational quote: “Do a little more each day than you think you possibly can.”—Lowell Thomas

Stretching

You’ve seen the iconic image of a runner bent over and touching his toes. You’ve probably seen plenty of runners doing this. So it may surprise you to hear that this so-called static stretching—attempting to lengthen muscles and tendons to increase flexibility—is generally not recommended before a run.

Stretching has been hotly debated in recent years. There is no evidence that static stretching prevents injury or improves performance, experts now say. In fact, there’s some evidence that it can hurt. When it comes to staying injury free, functional range of motion is more important than flexibility.

“If you can run comfortably, and without injury, there is no need to stretch,” says William O. Roberts, professor in the department of family medicine and community health at the University of Minnesota Medical School. He’s also runnersworld.com’s “Ask the Sports Doc” columnist.

Before your workout, your time is better spent warming up with dynamic stretching. (See this page on warming up.)

These moves, which include butt kicks and walking with high knees, improve range of motion and loosen up muscles that you’re going to use on the road. They also increase heart rate, body temperature, and bloodflow so you feel warmed up sooner and run more efficiently.

After your run, if you have an area that still feels tight—the calves, hamstrings, IT bands, and quads tend to be tight after running—you may want to try the static stretches starting on this page. But it is not necessary. Each stretch should give you the feeling of slight discomfort in the muscle. But do not stretch to the point that you feel a sensation that is sharp or intense. If you do, back off.

Five Key Postrun Stretches

Try this five-stretch routine after your workout to reduce stiffness. Hold each stretch for 2 seconds.3

QUAD STRETCH

While standing on one leg, bring your opposite heel back toward the rear of the body and grab your ankle or foot. Keep your knees aligned and your back straight. You should feel this stretch down the front of your thigh. Repeat on the opposite leg. If necessary, hold on to a stable object for balance.

HAMSTRING STRETCH

Place your leg straight out in front of you. Bend your knee and slowly extend and lower your hips back as if you’re sitting in an imaginary chair. Make sure you keep your grounded foot parallel to your outstretched leg. Repeat on the other side.

CALF STRETCH

Stand with both feet on a curb or step. Lower your heel down so you can feel a stretch in your calf. Keep both knees bent so you can deepen the stretch. Repeat with the other leg.

CHEST STRETCH

Stand with your feet shoulder-width apart. Lace your fingers together behind your head above your neck. Squeeze your shoulder blades together while trying to bring your elbows out to the sides behind you.

How Running Changed My Life

Running helped Tara Cuslidge-Staiano change her entire identity

Tara Cuslidge-Staiano reached her get-up-or-give-up moment the day after Christmas in 2009. She was getting ready for dinner, and no clothes fit.

Her weight had ballooned to 200 pounds. She was tired all the time, the doctors had said she was prediabetic, and she was taking medications to control her cholesterol and blood sugar.

“I just decided enough is enough,” she says.

The next day, she got on the treadmill and set it for 15 minutes per mile. Afterward, she told her husband, “I’m never going to do that again.”

But the next day, she did do it again. She ran 1.1 miles. And the next day, she did it again. She kept coming back. The day she set her sights on covering the 5-K distance on the treadmill—and succeeded—was the turning point when she fell in love with running.

“Wow,” she remembers thinking. “I just ran my first 5-K, and it wasn’t as bad as I thought it would be.”

From then on, running morphed to something that felt like pleasure, not punishment. She started running on days when she hadn’t planned to, and set her sights on long distances.

Four years later, Cuslidge-Staiano has finished 14 half-marathons and two marathons. She’s lost 35 pounds and is completely off medications to control her blood sugar, cholesterol, and diabetes. But the best part is the transformation in how she feels and how she sees herself.

“I have more energy. I want to do more,” she says. “And I just became somebody else—someone who wants to be out there and active, not someone who wants to be on the couch eating bonbons.”

AGE: 28

HOMETOWN: Stockton, California

OCCUPATION: Journalist, community college instructor

What’s your regular workout routine? On Sundays I do a long run of a minimum of 10 miles. I’ll do a tempo run on Monday; on Tuesday run 6 miles with a friend; cross-train and do core work on Wednesday; run 6 to 8 miles on Thursday with a friend; rest on Friday; and on Saturday, cross-train or rest, depending on what else I’ve done that week.

What is your weight-loss goal? I was at 200. My lowest was 150. When I started training for a half-marathon, I packed back on some weight. I’ve been able to maintain [at 165 pounds] for more than a year. That said, my husband and I are also hoping to have kids, so I’m trying to lose some weight to avoid diabetes rearing its ugly head again when and if I get pregnant.

What kinds of changes have you made to your diet? I let myself splurge from time to time. At the beginning, I made the mistake of limiting everything. When I’d see a cupcake, which is my biggest weakness, I would feel as if I couldn’t eat it because that one cupcake would bring back all the weight. Now I indulge in the cupcake but know I can’t do it every single day. I actually splurge on cupcakes now during race weekends, because I know I’ll be burning off those calories (and more). My biggest issue is overeating. It’s something that doesn’t go away; I just get better at controlling it. I watch my portion sizes now. If I go out to dinner, I look at the low-calorie options as well. I never realized how little food I needed to actually feel “full” until I started eating less. Now I stock up on 100-calorie snacks or fruit as go-tos for when I start to feel hungry.

What advice would you give to a beginner? The first mile is always the hardest. And that’s true if it’s your first run, or if you’re out on a 10-mile run. Just get past that point. It always feels better after the first mile. It’s not going to get easier, but every day you get stronger and better.

Favorite motivational quote: “You must do the thing you think you cannot do.”—Eleanor Roosevelt. I actually have “you must do the thing” engraved on my RoadID I wear when I run. I bought it before my first half-marathon, and it’s kind of inspired every step of my journey.

Is Yoga for You?

The health benefits of yoga have been well established: Studies have shown that yoga reduces stress, aids weight loss, helps you manage pain, and can help you stick to an exercise routine. A July 2005 study in the British Journal of Sports Medicine even showed that yoga helped runners get faster.4 But the impact of yoga on running performance has not been widely studied. That said, coaches and experts say that the strength and flexibility you develop on the mat—namely in the core, quads, and hip flexors—can help you run more efficiently and stay injury free.

“When you’re on the mat, engaging the transverse abs helps stabilize the core and lower back and translates well to running,” says Adam St. Pierre, a coach, biomechanist, and exercise physiologist for the Boulder Center for Sports Medicine. “If you have a strong and stable core, you won’t get a lot of excessive rotation in the pelvis, so you’ll be more efficient.”

Runners tend to be tight in the hip flexors, which can lead to weakness in the calves and hamstrings and excessive pronation, says St. Pierre. “That can set off a cascade of other issues, like lower-back injuries, IT band syndrome, plantar fasciitis, Achilles problems, and shin splints.”

Additionally, tightening the mind-body connection, as you do in yoga, helps you tune in to how hard you’re working so that you can better manage your efforts when you’re running, says yoga instructor Sage Rountree, an RRCA-certified coach and author of The Runner’s Guide to Yoga. Yoga helps you tune in to areas where you’re needlessly tensing up, so you can relax them and free up strength that your legs and lungs need. “It lets you notice where you’re wasting energy, so you can run more efficiently, and that’s the key to endurance,” says Rountree.

That said, many people insist that they’re too tightly wound—in body or mind—to practice. And if you’re not careful, you can end up hurt, frustrated, and even more stressed out than you were before. Here’s a guide that will help you find the right place for yoga in your running life.

Shop around. From yin yoga to vinyasa, and from gyms to spalike studios, there are a dizzying array of yoga styles and settings to choose from. And different teachers can have a radically different effect on your experience. No single style of yoga is the best for everyone. As with a good training plan, different styles can be the best fit for different runners at different times. So if on your first try you’re turned off by the teacher, the vibe, or the poses, keep searching until you find the right fit for you, says Johnny Gillespie, owner of Empowered Yoga, a Wilmington, Delaware–based studio with four locations. “It’s not the type of yoga you practice, as much as the consistency of practice, that counts,” he says. “The most important thing is finding a place where you feel comfortable, where you’re connecting with your teacher—like you would with a coach—and where that teacher is helping you to pay attention to yourself.” Rountree recommends starting at a dedicated yoga studio rather than a gym. Many studios have classes that are geared specifically to runners, focusing on areas where runners tend to be weak and tight, like the core, glutes, quads, and hip flexors.

Time it right. Practice the most-intense yoga during the least-intense periods of running. As you ramp up your mileage, run faster, and get closer to race day, you should practice yoga less frequently and with less intensity, says Rountree. If you pile on an intensive daily practice on top of your toughest running weeks, “you’re undermining yourself,” she says. “You’re interfering with the ability of the body to recover, and you run the risk of hurting yourself.” By the same token, don’t do an intense yoga practice on the same day as a hard workout.

Take it easy. Rountree suggests that runners practice restorative yoga, postures that are held for several minutes at a time, with the support of blankets, blocks, and other props. This can be a tough sell to many people who equate intensity with progress.

Don’t get hurt. The last thing you want is to inflict an injury on yourself in the process of trying to prevent one. Runners’ high pain thresholds, paired with competitive natures, may make them more prone to injury, warns St. Pierre. “You’ve got to come to terms with the fact that you might not be able to do this pose right away,” he says. Indeed, many runners, eager to loosen up tight hamstrings, end up overextending or tearing the tendons just beneath the sitting bone, says Rountree. Another reason to steer clear of the hamstrings: And it’s not just the hamstrings you have to be wary of. St. Pierre got too aggressive in Pigeon pose, trying to stretch out his glutes and piriformis, and ended up not being able to run for 3 weeks.

Be humble. Just as it takes years to master running, it can take years to master yoga postures. So don’t go into your first class—or your first 20 classes—expecting to achieve an Olympic A standard in yoga. It may be daunting; you might be self-conscious and worry about what everyone else is thinking. “You’re not going to go in there knowing everything,” says Rountree. But remember that everyone is focused on themselves, not you. And rest assured that with enough practice, you’ll be okay with less-than-perfect performance.

YOGA ETIQUETTE

Dos and don’ts for your first time at the yoga studio, from Runner’s Guide to Yoga author Sage Rountree:

GET THERE EARLY so you can tell the teachers you’re a runner, areas of tightness and injury, and whether you want them to help you adjust or get into postures.

DITCH YOUR DEVICES. Don’t take cell phones or iPads into the room to watch while you practice.

PASS THE SNIFF TEST. You’ll be taking deep breaths close to others, so go easy on the cologne and perfume.

OFF WITH YOUR SHOES. Since all yoga is practiced in bare feet, you don’t want to track in dirt and debris from the outside. Most studios will designate places near the door for leaving your shoes.

DON’T TALK during class unless the teacher allows it.

DON’T GET UP. Resist the urge to leave during Savasana, the final resting pose. No matter how busy you are, it’s distracting to others who are trying to relax and meditate.

FIND THE TIME. No time to get to a yoga class? It doesn’t have to be an all-or-nothing proposition. There are online yoga classes that you can download or do anytime, try ours at runnersworld.com/yogaseries.

Strength Training for New Runners

Strength training can help you run more efficiently and stay injury free. Research “points clearly in the direction of weakness of the hip stabilizing muscles and the inability to properly control lower-extremity joint motion,” says Reed Ferber, associate professor at the University of Calgary and the director of the Running Injury Clinic. To avoid getting hurt, says Ferber, is to follow a training plan to avoid doing too much too soon, and to strengthen the muscles that stabilize your hips—like the gluteus medius and the hip abductors.

Heather K. Vincent, PhD, director of the Human Performance Laboratory and Sports Performance Center at the University of Florida, says that those who want to begin running may benefit from starting a strengthening-routine program before they even hit the road. Increasing the strength and control of the smaller muscles in the feet and larger muscles in the lower limbs helps control movement at the pelvis, hips, and knees so you can maintain proper running form and stay injury free. “Strengthening the muscles can help runners land with more control and less risk of injury,” Vincent says. Start by doing the following routine, designed by Vincent, four times per week. After you’ve been at it for about 2 months, you can ratchet it back to three times per week.

Unless otherwise noted, for each of the following exercises, start by doing as many repetitions as you can on each side while maintaining proper form. You might start with one set of 20 reps and build up to three sets of 20 reps, resting for 45 to 90 seconds in between sets. Then increase the resistance so the effort feels harder and you can get keep getting stronger. Maintaining proper form is the most important thing. When your form starts to fall apart, that’s a sign that you’re tiring and have done your final rep. “Doing improper form puts you at risk of injury,” says Vincent. Not to mention it’s a waste of time!

Foot and Leg Strength

These exercises will help build strength in your hips, legs, and feet so you can maintain good running form and avoid common overuse injuries like runner’s knee, IT band syndrome, and foot pain. To perform many of these, you’ll need a rubber resistance band. These can be found in most sporting goods stores or online. Rubber strip bands are the least expensive, and they can be cut to different sizes. Tube bands come with handles and can be held during exercise. Bands typically come in varying levels of resistance: light (which provide 3 to 5 pounds of resistance), medium (which provide 8 pounds of resistance), and heavy and extra-heavy bands (which provide 12 to 20 pounds of resistance). Heavy and extra-heavy bands are designed for people who are already trained. To feel whether the band is right for you, test it out in the store. Look for extra features that matter to you, like clips, handles, cuffs, or rings. Consider buying two different resistance levels for different exercises.

SEATED HIP EXTERNAL ROTATOR

• Attach a resistance band to the left end of a bench or a stable object and loop the other end around your right foot.

• While sitting on the exercise bench, keep your knees together, lift your right leg out to a count of two, then release it back down to a count of two. Repeat on the other leg.

STANDING HIP FLEXOR

• Tie a resistance band to a stable object.

• Put your right foot in the resistance band and turn so you are facing away from the band’s anchor.

• Keeping your right leg straight, lift it forward to a count of two, then release it back down to a count of two. Repeat on the other leg.

STANDING HIP ABDUCTOR

• Tie a resistance band to a stable object.

• Loop the other end around your right foot so the band crosses in front of you.

• Standing with your left leg slightly behind you, keep your right leg straight and lift it out to the other side. Lift it to a count of two, then release it back down to a count of two. Repeat on the other leg.

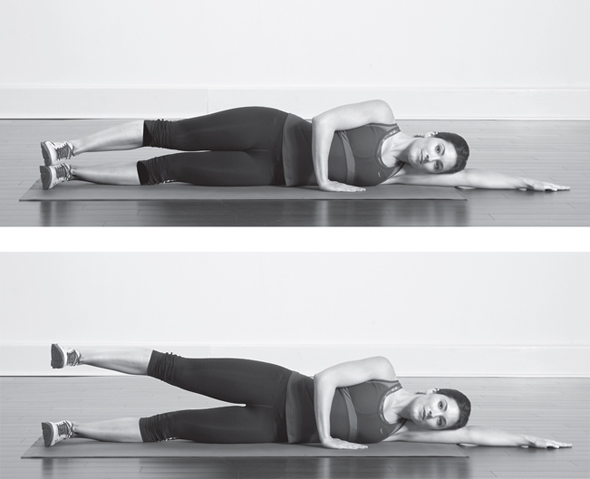

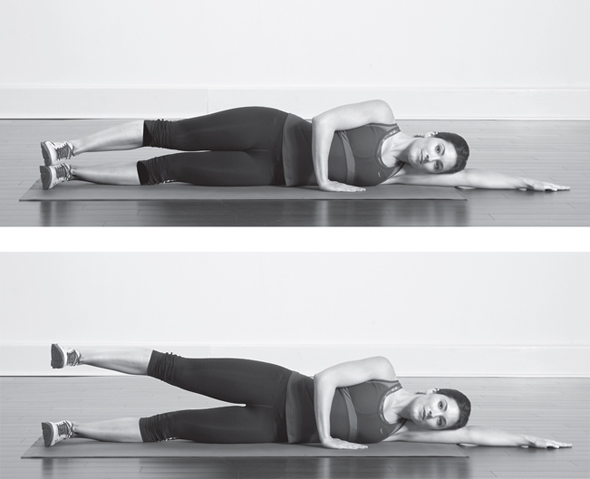

SIDE-LYING LEG RAISE

• While lying on your side on the floor, raise one leg straight up and lower it back down.

• Do not let your leg cross your midline (move in front of your body or go behind your back).

• Raise the leg 15 times. Repeat on the other leg.

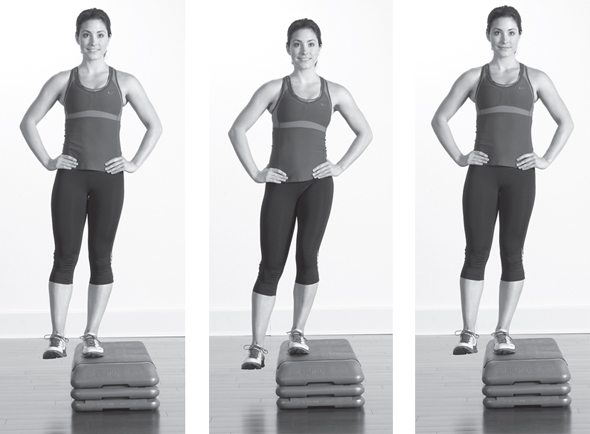

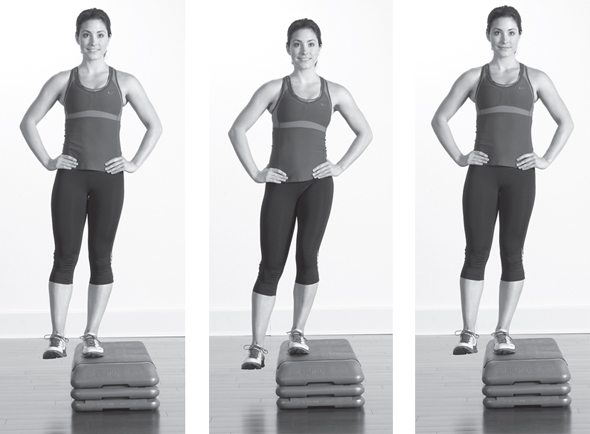

PELVIC DROP EXERCISE

• Use a stair or a step from a step exercise class.

• Stand on the step on one leg. This is your support leg. Keep that leg straight and keep your abdominals engaged.

• Allow your other leg to hang off the edge of the step. Let that leg slowly lower toward the ground by allowing your pelvis to slowly drop down. Do not let that foot touch the ground. Just control the movement with a slow, steady drop. When you’ve gone as low as you can without touching the ground, hold this position for two counts, keeping your abs tight.

• Keep your support leg as straight as possible as you lower the other leg. Don’t let it bend.

• Raise your pelvis up to raise the foot up. When the pelvis is level and your hips are even, that’s one rep.

• Do 10 to 15 reps on each side. When it becomes easy, build up to two or three sets of the exercise or hold a lightweight dumbbell in your hand to increase the resistance.

Foot Strength

Anytime you’re sitting down, you can work on strengthening your feet. You can do these exercises while you’re watching television, sitting at your desk, or taking a break. Perform 15 reps of each exercise. Do each of these exercises three to four times per week. Choose four from the group and rotate different exercises each day.

HEEL RAISE

• With your feet on the floor lift your heels up while keeping the balls of your feet on the ground.

• Lower your heels.

• Repeat.

TOE GRIP

• With your feet flat on the floor, act as if you were raking your toes backward and curling up the arches of your feet.

• Flatten your foot again.

• Repeat.

DORSIFLEXION AND PLANTARFLEXION

• With your legs stretched straight out in front of you, push down your toes like you are pointing them (plantarflexion).

• Then bring your toes back (dorsiflexion).

• Repeat.

TOE SPREAD

• With your feet flat on the floor, envision spreading your toes like you would spread the fingers of your hand.

• Relax your toes.

• Repeat. This is tricky and takes some practice.

TOE TAP

• With your feet flat on the floor, tap each of your toes up and down on the ground in sequence like you would tap your fingers on a table.

• Repeat.

EXAGGERATED INVERSION AND EVERSION

• Starting with your feet flat on the floor, drop your arches in and lift the sides of your feet outward.

• Hold for 2 seconds, then lift your arches while you push the outsides of your feet firmly down on the ground.

• Hold for two counts. Repeat.

GRABBING AND PASSING A TOWEL

• Place a small hand towel on the floor.

• Alternate which foot will pick up the towel using the toes.

• Pass the towel from the toe grip of one foot to the other foot and hold in place for two counts to strengthen the grip.

ESSAY

RUNNING WITH ASTHMA

By Caitlin Giddings, Runner’s World web producer

Exercise-induced asthma: It sounds like something a nerdy kid like me might dream up to get out of gym class, but it’s a real condition and the scourge of my running life.

When I set out too fast—or the day is hot and sticky, or there’s a chill in the air, or something (anything!) triggers my delicate race day emotions—the wheezing starts, panic sets in, and I immediately begin the process of having an asthma attack.

It happens almost without notice. One minute, I’m darting toward a finish line, high on endorphins, life, and triumph of the human spirit. Then some small, imperceptible shift takes place in my lungs, and I’m hit by a wave of powerlessness and panic, like a fish out of water, or a hamster in a shoebox without airholes.

It took me decades to break through that panic and become a runner, particularly because my asthma wasn’t diagnosed until I was in my late teens. All I knew back then was no matter how hard I tried, running felt flat-out impossible. My mom—a fitness-obsessed marathoner—didn’t know what to do with her nonathletic, comic-book-obsessed kid and used to torture me with organized family “fun runs” and laps around the block in exchange for Nintendo time. But it wasn’t that I was trying to disappoint her or reject her active lifestyle. I just wanted jogging a single mile to feel more like the first level of a video game and less like being sucked out of a space station’s airlock.

I just wanted to take deep breaths and fly.

So how did I end up carrying the family running baton? My transformation from teenage sloth to running addict wasn’t easy, and like everything else about me, it wasn’t fast.

It started with my exercise-induced asthma diagnosis and an Albuterol inhaler, which enabled me to work up to 2 miles. Just knowing I had help in my pocket made it possible to slowly and steadily increase mileage without the snowballing panic I get when my ability to take in oxygen decides to take a nap. It was scary, but I persisted, imagining each short, little run to be a snapshot in my superhero-training montage. Then after more than a year of side stitches and struggle, one day running 6 miles felt as comfortable and effortless as doing a Monday New York Times crossword puzzle.

There was no conscious thought. My limbs just locked onto the same radio frequency and started 10-4’ing back and forth like they had their own CB channel. It felt better than anything has a right to. My first runner’s high—I almost couldn’t believe it was actually good for me.

Today—eight marathons later—I carefully manage my asthma with an inhaler, a long warmup before working up to full speed (particularly in the winter), and a lot of patience with my strengths and weaknesses as a runner. I’ve learned to always carry a phone and inhaler when I’m going out on a long run. I’ve learned to run at inhumanely early hours and hydrate like water is going out of style when the weather is hot and humid, and not beat myself up if I have to take a walking break. And I’ve also learned to accept that my mile pace won’t deviate too far from my 5-K pace, which won’t be too far off my half-marathon pace. Like an old computer, it takes me a while to whir into action.

But it’s taken me so long to get here that there’s no way I’m stopping now.

If anything, my asthma only makes me more determined to keep running so I don’t have to start all over again from scratch, coaching my breathing into taking on more and more. And anytime I feel sorry for myself after a bad race, I try to remember that everyone on the course has his or her own hurdles to overcome.

So if you have exercise-induced asthma, don’t write yourself out. It might take you a bit longer to reach the point where running feels safe and comfortable, but once you build up endurance, your breathing anxiety will begin to fade, along with the snowballing panic that can trigger the worst of your symptoms. At least that’s been my experience—as I’ve grown more and more confident of my ability to prevent a midrun attack, I’ve faced those attacks less and less frequently. Racing with asthma can be scary, but it reminds me of a great quote by Ronald Rook: “I do not run to add days to my life, I run to add life to my days.”

So take a deep breath and a risk, build strong lungs, and try not to compare yourself to runners who might not be facing the same breathing challenges you’re facing.

For a few minutes, just see if you can fly.