III

THE RELATION OF A JOURNEY TAKEN TO PERSIA IN THE YEARS 1598–1599 BY A GENTLEMAN IN THE SUITE OF SIR ANTHONY SHERLEY, AMBASSADOR FROM THE QUEEN OF ENGLAND

Translated into English from the French Original of ABEL PINÇON

WE sojourned about two months in Halep [Aleppo], whence we departed after we had supped, the second day of September in the year one thousand five hundred and ninety-eight, taking the road to Babylon [Baghdad]. We arrived about midnight at a village called Gibrin,1 five miles distance from Halep. On the third of the said month we came to another village named Bab [Bāb], near which there is a spring of very good water. The fourth day, or, more exactly, the fourth night—as we marched always by night—we passed by a ruined and deserted village a mile from Bab, and three miles away from Bab another called Abissin,2 which is inhabited.

On the fifth day we came to Bule [Bīra], which lies on the river Euphrates. The country between Alep and Bule is very beautiful and fertile, though it is ravaged by certain Arab marauders who, when they find themselves the stronger, will not let a single traveller pass without robbing him. Bule is an enclosed town with a castle fortified after the manner of the Turks. We sojourned here for five or six days, making the necessary preparations, overhauling our boat, and buying biscuits, cheese, butter, meat, chickens and other supplies obtainable on the spot.

Very early in the morning on the tenth of September we embarked on the Euphrates. There were thirteen barges, among them being those of the Cadi and of the Diftendar [Daftardār], who were on their way to take up their duties at Babylon [Baghdad]. There were many Turkish merchants and peasants, and in our barge there were three or four Venetians and the same number of Jews. That day we saw nothing remarkable, other than the poverty of the Arabs. We saw a great number all naked, some of whom crossed the river on skins which were inflated and filled with air. Likewise we saw on the shores of the river an ancient house which the Jews said had been a house of Abraham, and we passed by ruined edifices built of stone blocks of great size.

On the eleventh day we saw a market-town situated in an elevated position on the shores of the river, which our Arab boatmen called Sarin.1 That day a number of Arabs on foot and on horseback, armed with slings and bows and arrows, appeared on the riverbank. They slung stones and shot arrows at us, but when they heard the noise and racket of our arquebusade they took to flight.

On the twelfth day appeared some of these ruffians who had come to water their herds; they shouted abuses at us, but retired when they heard our carbines which we fired in the air. The same day we saw three towns, one called Arborera [Abū Hreyra], the other Giabar [Qal‛at Jābir], and I could not learn the name of the third. The day before we had passed another called Bélis [Balis]. We saw in this district five lions, two very large and three medium in size, and certain birds with red wings, much larger than geese. Watermelons are also found there, and the Arabs used to bring them to us at night, swimming to our boat and exchanging them for bread or money; they called this species of melon angurie.1 On the fourteenth day we saw again three lions on the river-bank; near by, an attendant of the said Diftendar unintentionally killed a Turk while firing an arquebus, which nearly caused us a great deal of trouble at Raccha [Raqqa], a very ancient town, because the Turks there tried to lay the blame on the Christians of our company. However, we were able to escape because Aborice [Abū Rīsha]2 was in the neighbourhood and would not allow innocent men to pay for the blood of a Turk. Aborice is a king of the Arabs and he usually lives in Mesopotamia, camping in tents and never wishing to enter a town. He is a prince of about thirty-two years of age; he has a certain majesty, being of shapely form, but his skin is very black. He has a large stud of several thousand camels, which he uses as a rampairt with which to enclose his encampment. He also keeps many small horses and birds of prey, and leopards with which to catch gazelles. On the fifteenth day some of our company went to present their gift to the said King, and to make their obeisance; the gift consisted of four robes of cloth of gold and silver, to which the Venetians contributed, as we were all travelling in the same boat.

On the sixteenth day one of our rowers was wounded by an arrow discharged by an Arab; on the same spot we caught sight of another lion.

On the seventeenth at about daybreak a misfortune occurred to one of our ship’s masters. He was sleeping by the river-bank when he felt his turban being pulled off his head. This was followed by a dangerous shower of blows which were delivered by an Arab whom it was impossible to overtake, for he disappeared with his booty into a neighbouring wood; and though some of our men pursued him they were unable to capture him. The same day we arrived at the ruins of an ancient town which in Arabic is called Zelbe [Chelebi], and is situated on a hill surmounted by a castle. Formerly it was encircled by walls in the style of those of Antioch.

On the eighteenth day we came to Der,1 an enclosed market-town, where we rested from mid-day until dawn the following morning, which was the nineteenth. That same day at sundown we arrived at a castle which is three or four bow-shots within the territory of Rabba [Rahaba]. From there we continued to Aziera [Achera], which we reached before dark, and where we spent the night.

The following morning, which was the twentieth, we passed by many erections constructed for the purpose of conducting water; they are like elevated pillars above the river and have enormous wheels by means of which the water is spread over the fields, and they caused us great inconvenience in navigating. During four or ve days we were constantly troubled in this way. Later we came across other methods of irrigating the country, machines for drawing water with an ox or some other animal suitable for that purpose. Many wild boars and roebuck are found in this district.

The following morning, the twenty-first, we started before daybreak on the way to Ana [‛Ana], but we could not reach our destination the same day, so we spent the rest of the night in a place five miles distant from Ana. The country in these parts is very fertile, full of trees and verdure.

On the twenty-third, two hours after sunrise, we reached Ana. It comprises seven small and beautiful islands which are like little towns, and where there grow quantities of dates. We left Ana after mid-day and slept at a village ten miles away, from whence we departed the following day, the twenty-fourth of September.

All that day we saw nothing worthy of notice, other than a little island which was very fertile. In the evening we reached a large and very ancient town called Adita [Haditheh].

We left there the following day, the twenty-fifth, very early in the morning. After midday we reached another town where there are some fine buildings and a castle still beautiful in spite of its old age.

On the twenty-sixth we passed by very beautiful and fertile country in which was situated a little hamlet; thence before nightfall we came to Ith [Hit], a very ancient town with a castle about a mile away. There is a great spring from which flows bitumen in large quantities, even the surrounding soil and pebbles contain bitumen, and the inhabitants of the country say that when the Tower of Babylon was being built bitumen was fetched from there. This spring is horrible, by reason of its black, bubbling water, and is commonly known as the “mouth of hell”. The surrounding fields produce large quantities of saltpetre.

On the twenty-seventh we passed neither town nor village, but we saw a number of herds and stud farms and many machines by means of which oxen and other animals draw water to irrigate the country. We took little rest that night, but as soon as we had supped we set out again downstream.

On the twenty-eighth we reached Faluge [Fellūja], where we stayed two days awaiting the arrival of camels to carry our baggage, and where we procured mounts for ourselves. A day later we reached Babylon [Baghdad]. This city is built on the banks of the Tigris and is about the size of Alep, although the population is not as large. It is enclosed by walls on the north, east and south, except on that part of the south where the river Tigris flows. This river is crossed by a bridge formed of boats on which are placed wooden planks and at either end are courtines. The castle of Babylon [Baghdad] stands at one end of the town between south and north. It is rather large, but, in spite of possessing a good deal of artillery, not very strong for defence. The towers are round and well built, partly of stone and partly of purple-coloured tiles. One can see the ruins of older buildings, such as the private residence of the Caliph, which is on the left-hand side of the bridge on entering the town. Opposite, on the other side of the river, there is a big ruined mosque, also several beautiful columns or obelisks and some mosques similar to the one which is near the castle. One can also see a little fortress which lies lower down towards the east on the same side of the river. There are likewise many chans [Khān] or palaces where the merchants live and keep their wares. The most beautiful is that belonging to Cicala [Chighālazāda], which was built while he was governor of the province. The second belongs to Murat [Murād Pasha], The others are not very well constructed; but during our stay Chassan Bassa [Hasan Pasha] was having a new one built on the north side of the river. As far as one can judge by foundations and by plans, this should be the most beautiful and the largest of all. It is being built of certain tiles, both large and beautiful, which are found in the ground outside the city, on what I believe to have been the site of ancient Babylon. As regards private houses, those of Mustapha [Mustafa] Agha, of Mehemet [Muhammad] Agha and of Mutucugi1 seem to me the most beautiful, though none of them are especially fine. All the women of this country, at least the greater number of them, bore a hole through their nose and attach a ring thereto. The town women have an extreme horror of the scent of musk and believe it to be poison to their little children. As the European merchants carry on a great trade in musk, we were chased away from one quarter of the city where we had taken lodgings, the people thinking we wanted to traffic in it.

In Babylon, otherwise named Bagadet [Baghdad], one lives well and cheaply; bread, wine, fruit, milk and cream are excellent and to be had for nothing, as also mutton, gazelle, chicken and pigeon, but especially the most exquisite partridges in the world, of which we bought a brace for two Venetian gazettes, which are eighteen deniers. The biggest boars cost only half a teston. Stuffs for clothing are also very cheap, and there are groceries of all sorts. Money, however, is expensive; for the loan of it one usually has to pay fifty per cent per annum. The Moors and the Turks there are much more courteous towards strangers than any of the people whom I have encountered in wandering round the world. It happened one day that a drunken Turk unsheathed his dagger at us, whereupon Hassan Bassa [Hasan Pasha], being told of this, immediately ordered that he should be given a hundred blows with a stick on the soles of his feet and the buttocks; this offence would not have been punished in Alep.

The Tower of Babel is at least two days’ journey away from the city. There is another tower which is only half a day’s journey away; the Venetians called this the false tower. The Moors in their tongue call it Carcuf [‛Aqarqūf], which signifies “sacrifice of the lamb”. We sojourned over two months in Babylon [Baghdad], waiting until there should be a caravan and until the Bassa of the district had paid Monsieur Sherley money which he owed him for certain cloths of gold, silver and silk; but having found about five hundred Persian pilgrims who were on their way to perform certain devotions in those parts, we joined them, hiring some of their mules and horses. We remained with them up to the borders of the Sophi of Persia, but we did not travel by the direct road.

We left Babylon [Baghdad] at sundown on the fourth of November in the year fifteen hundred and ninety-eight. We marched all night long, seeing neither house nor village.

At sunrise the following morning we reached a village named Dochala [? Dahala]. The country between this place and Babylon [Baghdad] is one vast plain, which, were it cultivated, would be fertile in many parts. It is irrigated by certain dykes or canals, through which flows water from the river Tigris.

On the sixth we left Dochala before sunrise, and three miles off we saw a beautiful and well-situated village called Angigsia.1 It lay on our right within bow-shot of our road. Having passed through another much populated village, we reached before mid-day a large market-town named Chasania [?Hasaniyya]. From Dochala to Chasania one traverses open country, but the road is rather troublesome on account of trenches and ditches which are made for the purpose of irrigating the fields.

We departed from Chasania two hours after sunset, finding the road very bad on account of the many hills, streams and torrents by which we were drenched. But once past this district we found the country very barren, and towards sunrise at seven o’clock in the morning we reached a valley, or rather a depression in the earth between two moats, which the inhabitants of the district claim to have been the site of a large town. We could, however, see no vestige of such a town other than a huge mound of earth. This place is distant from water, of which there was great scarcity, and, according to the guide of our caravan, is known as Bat,1 which name the Arabs give to all similar places. Later we passed through a pleasant little wood, and at some distance away past another town we came to a great desert, in which all the Persians and their guides on their way to their devotions at Samarra [Sāmarrā] lost their way; so much so that from dinner-time onwards for a good part of the night we kept on turning round in every direction without recognizing our road. At last we halted in order to rest ourselves and to refresh our mounts, and the following day, which was the eighth of the month, we were set on our road. A short while later we discovered the towers of Samarra, where we arrived at ten o’clock. In ancient times this was a very great town, as one can recognize by the ruins of old Samarra which lay facing us at a distance of about two bow-shots. One can see there the ruins of a mosque, which in my opinion must have been one of the most admirable buildings in the world. It has a spiral staircase on the outside.2 The place is named Samarra after its Lord.1 He is buried with his wife and children in a richly gilded room or chapel; and Persians of every age and sex come here in great devotion, through which means the government of the place receives great benefit.

We remained there that whole day and part of the following night, waiting until the Persians had finished their prayers. These completed, we departed, walking the rest of the night, and reached another pilgrimage place named Scherschersene2 about two or three hours before mid-day, this being the ninth day. This mosque is built in the Persian style, and several marble columns lie upon the ground. There was no one guarding this place like the preceding one; it remains always open and deserted. Here we found great scarcity of water, as there was only one salty and evil-smelling well, and, our casks being empty, we had to continue until midnight, when we reached a valley near a small wood where our guides hoped to find water: but in order to procure any we had to dig and make wells for ourselves, otherwise we would have remained thirsty.

We left there immediately after mid-day, and, walking at night-time, came upon the great road which goes from Bagadet to Persia. We spent that night in view of a great plain, facing certain inaccessible-looking mountains which we traversed the following morning, this being the eleventh day. We arrived two hours before daybreak in a large market-town built of earth near a small river. The place is called Seirp,3 and we remained there the rest of the day and night until the following day, the twelfth. On that day one of our camels and a mule died of cold, for the nights were getting cold in those parts.

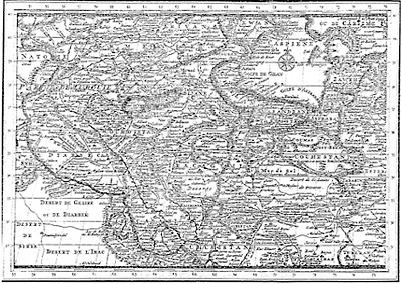

SECTION OF THE “Carte de Perse, dressée pour l’usage du Roy, par G. de l’isle, premier Geographe de S.M., de I’Atadtmie Royale des Sciences d Amsterdam. (Cbez Jean Covens et Cornçille Mortier, Geographes.)”

1724

Passing on from there and walking a great part of the night through very pleasant country where there were many ditches and streams, we reached another spot which is charming on account of the bushes and date-palms which grow there, and because it is surrounded on nearly all sides by low hills. The place is called Stéroban,1 and the neighbouring country is very fertile; a short distance away we had to cross six arms of a river, also many ditches, some full of water and others dried up, which gave us much trouble. We walked most of the night, going about hither and thither, for we had strayed off our road. Finally after midnight we called a short halt, but as soon as the day began to break we started again, this being the fourteenth day.

After having passed many mountains, we a: rived at the remarkable ruins of Farhatserin,2 formerl, a very large town. We rested until midnight beside a little stream in the vicinity, then continued, always ascending or descending until we reached the summit of a high mountain three hours after sunrise. An Italian of our company designated it as Caucasia, which I do not believe. A castle stands on the top of the said mountain; it is built as a quadrangle with uneven sides and is not very strong; it is surrounded by walls made partly of earth and partly of stone. Within the castle’s boundaries are many dwellings [loges] made of earth and covered with reeds. There we ran short of bread and fuel. The inhabitants speak neither Arabic nor Turkish, Armenian nor Persian, but have a language of their own, in the same way that the population has a name of its own, and does not obey a single living prince. From here to the borders of the Kingdom of Persia all the people are known as Courdes. The inhabitants of the castle, upon discovering the arrival of our caravan took much trouble to relieve us and to refresh us, cooking for us des tourteaux dans les tertrières according to their custom and bringing us butter made in their own way. They possess a great quantity of cattle, rice, dates and chick-pea. For a sheep we exchanged linen and handkerchiefs, which they value much more than money; in this way we obtained from them bread, butter, fruit and vegetables. The name of this place is Tanghi, and the whole country is called Tetang.1 One can see guns on the castle ramparts. The landscape around is very rocky and contains many good wells; at these one has to pay the toll charge of two schaiz [shāhīs] per horse and mule. We remained there until the seventeenth day, departing thence at sunrise.

On the eighteenth day of the month we came to Calachérin [Qal‘-i-Shīrīn],2 a wondrous place where the houses are built on a reef of rock, to which access is immensely difficult. We bought provisions for two days, as we would not be able to find any sooner. In this district one finds partridges which are larger than geese,3 they are grey with red feet, head and eyes.

One pays one schai for a horse, one for a mule and two for a camel, the same as at the castle of Tanghi. That day I saw a horse’s bone being cut; the malady of the bone is very strange and affects horses who have eaten too much barley. There is a similar illness which affects the lip of a horse; if this is not removed in time it will in the space of three or four days cause the horse’s death. The horses of this country are acutely subject to these maladies, as they are fed exclusively on barley.

We departed thence on the twentieth after sunrise, and on the eve preceding our departure one of our company had an unfortunate encounter, Having arisen on account of a colic and having gone out of the tent unarmed, he was surprised by a Kurd, who hit him on the head with a stick; fortunately he was wearing a well-quilted and padded bonnet, and he covered his head with his hand, which saved him from certain· death. The custom of these robbers, as also of the Arabs, is to watch for the arrival of a caravan and, when it stops anywhere, to lie flat on the ground, hiding behind hedges, bushes or trees: when some one ventures forth, particularly at night, they deliver him a blow on the head in order to stun him, then remove his turban or anything else they can lay hands on, and flee. When out on such a thieving expedition they are usually in pairs, one to deliver the blow with the stick, and the other a little way off with bow and arrows, prepared to shoot, should anyone attempt to attack his companion.

On the twenty-first we could advance little on account of the rains, and we spent the rest of the day at five or six miles distance from the castle of Heiderberg. [Hayderbeg].1 The whole length of this road there is a beautiful plain abundant in cattle, and one sees the remains of a ruined castle.

We departed on the twenty-first before mid-day, and, as we could cover little more than seven miles that day, we halted beside a ruined castle. Before reaching it we passed through a mountain gorge, which was extremely awkward for our laden camels and mules. All this country is one beautiful plain, half of which is very fertile, while the other half is marsh-land and in the swamps are numberless wild birds such as cranes, ducks, teal, plovers and others. There is also a very pleasant little river.

We suffered continually from the rain pouring down on our backs, and we ran great risks on account of robbers who caused our caravan to scatter several times. We departed from there at mid-day on the twenty-second of the month, and after about eight miles of road we passed across a wondrously beautiful plain, at the end of which we came to a mountain. After much ascending and descending we traversed the mountain and rested that night at its foot.

On the morning of the twenty-third we left before sunrise and marched all day, finding neither house nor any shelter whatsoever. At nightfall we ascended another mountain, and descending the other side we came to a rich and fertile valley, That day we left [the main] caravan beside a broken bridge and a dangerous torrent named Abmorradan.1 Five or six miles’ distance from there we rested for the night.

On the following morning, which was the twenty-fourth, we crossed a small river which divides the lands and countries of the Turk from those of the Sophi of Persia; it is called in the language of the country Kara-Su, which translated into French means “Noíre Eau”. A well-constructed stone bridge crosses this river; it is called Pulischa [Pul-i-Shāh], which means the King’s Bridge. As soon as we had crossed it we entered a country rich in grain and every kind of cattle. After dinner we arrived at a big ruined Han [Khān], which is the name given to the palaces and houses where are lodged all ambassadors, merchants and merchandise. Some soldiers and customs officials were on guard there, for in that place one pays toll to the King of Persia. The said place is built below a very high ridge or mountain of living rock where are carved many images of men and animals with Greek inscriptions, but these have already been so destroyed by time that one cannot recognize more than two or three letters in sequence. One finds the image of the Ascension of Our Lord, with some Greek characters: the place is called Brisseton [Bīsutūn].1 We remained there the rest of the day and the whole of the following night, leaving an hour before daybreak of the next day, which was the twenty-fifth. We passed through some of the most beautiful country imaginable, with many houses and tents or pavilions.

That same day we passed through a town which had been burnt six years previously by the Bassa Cicala [Chighālazāda], who was then governor of Bagadet. We slept in a place called Chengagiur [Kengaver], and left after dinner on the twenty-sixth of the month. The town is quite large and is built entirely of earth, no other materials being used. From there we continued to another town called Mastrabad,2 which we reached before evening and where I left Monsieur Sherley. On the twenty-seventh of the said month I started off in haste with Ange, who was our interpreter, and another,1 who was a servant of the said lord, in order to reach Casnivot, or, as others call it, Casnem or Casbin [Qazvīn], and prepare the house for him. From Mastrabad to a large market-town called Sadarvad [Asadābād] it is three miles. All the country is very mountainous and was at that time covered in snow, That same day, an hour before sunset, we reached a market-town called Sadca [?Zaga] and departed thence before midnight. After changing horses we came before sunrise to Raican [?Razan], where we breakfasted. This was the twenty-eighth day, and that evening we reached Caha,2 where we slept, having strayed from the road on account of a thick fog.

Three hours after daybreak on the twenty-ninth day we came to Darghesin [Darguzin], where we changed horses. It is a large town, where are to be found all the necessities of human life, such as bread, wine, fruit, and among other things the most delicious melons I have ever tasted. After leaving there we slept at a small village called Ana [?Ava], situated on a mountain called Karagan [Kharaghān], which means “murderous”, for one or two hundred people usually perish there in winter-time. At the foot of this mountam lies quite a good market-town, at one end of which there is a Han, that is to say a palace which, both for its size and for its apartments, built in the modern style, is one of the most beautiful to be seen, Leaving Ana two hours before daylight and marching all day until night of the following day, which was the thirtieth, we came to a small place called Ismansada.3 Here we had great difficulty in finding food either for ourselves or for our horses, or even a spot where we could take cover against the cold, which at that time was very great.

Coming away from this place at midnight, two hours before sunset on the following day, the first of December, we reached Casvin, or Kasbin, which is at present the capital of the lands of the Sophi. It lies in ancient Media, about ten days’ distance from Tauris [Tabrīz], in a great plain between hills and mountains. It is a little smaller than London in England, and the same length, but it is very badly built of baked earth, and the houses on the interior are of chalk. The town has no walls or fortress, also no river to give water, except a little stream which flows through one quarter of the town. There is nothing remarkable except a few mosques and the doorway of the palace of the King, which is well built. There are a great many merchants, but not many rich ones, also several artisans such as goldsmiths and cobblers, who make the best shoes in the whole country out of segrin [shagreen], in green, white and other colours. There are some masters who make gilded and coloured bows with arrows to match, and others who make richly gilded horse-saddles with gilded and coloured saddle-bows.

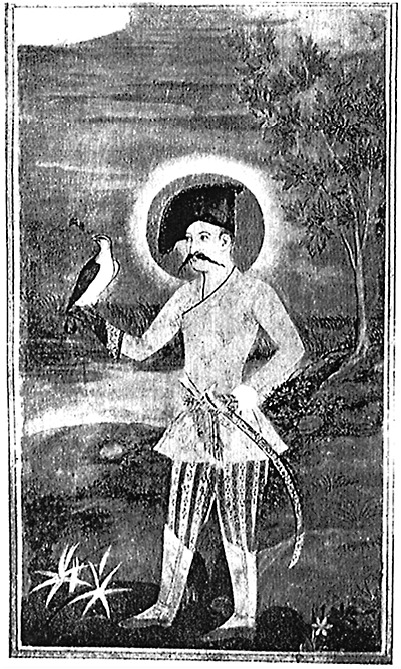

There we awaited the King, who was returning victorious, having conquered the lands of the Tartars of Usbec [Uzbeg], whom he had been away fighting for some time. When the King approached Casbin and heard of our arrival, he ordered us to issue forth two miles outside the gates of the town to offer him homage; we were conducted there by one of the stewards of the King, who was governor of Casvin and guardian of His Majesty’s wives. When our company had approached to within five or six steps of the King, the steward made a sign to Monsieur Sherley, his brother and myself to dismount in order to kiss His Majesty’s feet, for it is thus that this prince is accustomed to being saluted. He was five or six steps ahead of a large squadron of cavalry, and while he stretched out his leg he pretended the whole time to look in another direction. After we had kissed his boot he spurred his horse sharply and, guiding it dexterously, dashed across the camp after the manner of the country. He was clad in a short garb without a robe, which is against the custom of Mahommedans, and he wore a gold brocade doublet and tight breeches of the same material. On his head was a turban, adorned with many precious stones and rich plumage. In his hand he carried a battle-axe, playing with it, carrying it now high, now low, and now and then placing it on his shoulder with rather strange movements.

In his triumphal entry he caused to be carried on the end of strong and heavy spears twenty thousand heads of Tartars whom he had defeated in Usbeg, which appeared to me a hideous spectacle. After those who carried the heads came young men dressed like women richly decked, who danced in a manner and with movements which we had never seen elsewhere, throwing their arms about and extending them above their heads even more than they raised their legs from the ground, to the sound of atabales,1 flutes and certain instruments which are provided with strings, and to the sound of a song composed on the victory which they had gained, this being sung by four old women. In the midst of these young men were two grown men who carried while dancing, two lanterns like those of the largest galleys at the end of a stick which was attached to their girdle. On these lanterns were painted flowers, crowns, laurel-leaves, and birds, and along the stick hung mirrors and other glittering things. Among all this crowd was a large troop of courtesans riding astride in disorder, and shouting and crying in every direction as if they had lost their senses, and frequently they approached the person of the King to embrace him. Behind this noble squadron there came on foot a number of pages who carried good bottles and flasks of wine and cups, which they presented very frequently to the King and to his nobles. On either flank followed the cavalry, and in the first ranks there were four trumpeters who played on certain trumpets and sackbuts of extraordinary dimensions, which gave a bitter and broken sound very alarming to hear. The cavalry numbered two thousand five hundred horse; the first and those which were near the King were in good condition, covered with large cloths of brocade on which were represented angels and horses and other animals of all kinds, after the manner in which they decorate their materials in this country. All the inhabitants of Casbin and of the neighbourhood were come to receive their King two miles outside the gates of the city. They were separated into two groups between which the King was to pass with his triumphal retinue. And so the King on entering the town would go straight to the Midan [maydān], which is the public square, in which they have horse-races and training and shooting with the bow and other exercises. In the middle of this place two houses have been built, one on each side. The King, on dismounting outside one of these houses, entered it, and we were led thither. There had been prepared a collation of fruits such as pears, melons, raw quinces, pomegranates, oranges, lemons, pistachios, nuts, almonds, grapes, sweets and wine. Monsieur Sherley, his brother, his interpreter and myself were led into the chamber where the King was, and there we drank joyously with His Majesty, who gave us a very good welcome, show-ing us by word and by deed that our arrival was highly agreeable to him, Noticing that we were sitting on the ground somewhat uncomfortably, he had some benches and chairs brought for us and passed them to us with his own hand. Thus having drunk a little with us, he departed straight for his palace without warning us. And we, for our part, having realized by the number of people who had gone that the King had retired, went towards our lodging; but three hours after we had supped he sent for us to come to the Bazar—this word in the Arab language signifies “market”. This is a covered place or a market where are situated the greater part of the shops of the town, which the merchants had festooned and painted a month before the arrival of the King, in order that the King might there make festival and rejoicings. This is how they do it: the artisans come there at nightfall, open their shops which have been closed all day, light an infinite number of candles and lamps, using the fat of ox and other animals instead of oil, displaying outside their shops all their most expensive wares, even their money, and seat themselves in their shops as if they wished to sell this merchandise. The King, for his part, causes infinite treasure to be brought there, as gold and silver coins, horse-saddles, swords, vases covered with precious stones, especially with rubies and turquoises, and pictures which are brought from Venice, in which this prince takes a great delight All these things are exposed to the view of all; besides which there are many booths covered with all kinds of fruit, sweet-meats and good wine. In short, they eat and drink and jump about, and the children dance with the courtesans, and the fools make a thousand antics; and here I should observe that there are no banquets in Persia without music and courtesans, for otherwise they would take very little notice of them. Et s’il advient que quelque chrétien vient à se mêler avec ces femmes il ne court fortune comme en Turquie. Cette liberté coûta cher à un des nôtres, car il pêcha des huîtres à la Persane. The festivities of the Bazar lasted four or five nights, and the Francs were always invited. This is the name which one gives everywhere in the Levant to people from Europe.

After these pleasant recreations Monsieur Sherley presented to the King a number of girdles and pistols which he had brought from Alep, and an emerald pendant shaped like a grape. The matchlocks of the pistols were inlaid with mother-of-pearl, but this present was not of much value. The King gave him in exchange thirty horses with their trappings, of which two were of gold enriched with turquoises and rubies, but the rubies, for the most part, were not very fine. I myself got a good Arab horse, the rest were old hacks badly saddled and with old bridles. At the same time he sent him twelve camels, five mules, and some carpets and mats to decorate his house and to sit on; an Indian tent suitable for sleeping in the open, and one hundred and fifty Philippe-dales [Spanish dollars] in cash. Having done this, the King desired to go to Spahan [Ispahān], the ancient capital of Parthia, distant twelve days’ journey by caravan from Casbin, whither we followed him. One finds on the road some fine cities as, for example, one which is called Com [Qum], and another, Cassan [Kāshān], which is larger and richer than Com, and one finds also many towns and villages. All the road is level, and on one side or the other one always sees mountains; among these, not very far from Com, there is one which the Persians call the mountain of the devil, saying that all those who ascend it are carried off by him without knowing whither; I was very anxious to know whether the devil was as malicious as they make him out, so I climbed to the top of the mountain, accompanied by an Englishman, and he and I walked for some time, but I fancy that he (the devil) did not yet want us, for he never appeared.

The town of Spahan, formerly called, according to some, Hecatompyle,1 is very large, but it has no fort nor any beautiful palace. It is not so lacking in water as Casbin, but it is very deficient in trees. Within the town there are fountains, and a small stream flows by, from which they water the country when they need to irrigate their crops. This manner of watering the soil is common to all that country, and by this invention they mitigate the heat of the sun. Persia abounds in all things necessary for human life, such as grain, wine, rice, meat, chickens and game, but she has a special abundance of fruits of every kind. Nevertheless the poor eat the meat of horses and camels which are sold by the butchers, a habit they have probably acquired from the Tartars who are their neighbours. The present King of Persia is called Scha Abas. He is about thirty years of age, small in stature but handsome and well-proportioned, his beard and hair are black. His complexion is rather dark like that of the Spaniards usually is: he has a strong and active mind and an extremely agile body, the result of training, and far more so than one might suspect. He is very gracious to strangers, specially to Christians. He has in his court many Armenians and Georgians descended from Renegades, to whom he pays honourable wages. Among them there is one called Stammas Culibeg [Tahmāsp-Quli-Beg], without whom the King could not live a single day. We also found an old Frenchman, a clock-maker, who is among the King’s artisans; although he is decrepit and cannot work any longer the King keeps him by charity, but his officers reduced his pension, deceiving him about [gabellaient] the liberality of their Prince, of which they complained to him. One day the old man related to me in his jargon, which is neither Italian nor French, how he had arrived in that part of the world, saying that he had been quite comfortable in Constantinople where he had plied his trade. He had, however, been induced by the words of Simon Chan [Khān], Prince of the Georgians, to leave Constantinople and to come to his country, where he promised him mountains and wonders. And, having charmed him by his tales, he took him to Japan where, on arrival, he took from him all that he had in money and goods, made him his slave, and forced him by beating to work at his art down to the time of his extreme old age, and treated him as if he had bought him in a market. He continued, as he told me, for ten years in this wretched plight until, having become useless, people took little notice of him, and so he saved himself by these means and came to the place where we found him and left him, burdened with many years but with even more troubles. He had been brought out to make us understand by the adventures of this poor and miserable old man the barbarity of a Christian prince and the kindness and humanity of a Muhammadan. But this prince of Persia treats in another way his own subjects, behaving towards them inhumanely and cruelly, cutting off their heads for the slightest offence, having them stoned, quartered, flayed alive and given alive to the dogs, or to the forty Anthropophagi and man-eaters that he always has by him.

There happened on the road from Casvin to Spahan, of which we have just spoken, a very remarkable thing, whereby I learned his severity towards his subjects. Once at Cassan [Kāshān] one of his soldiers began laughing and disporting in a garden with a courtesan; she, displeased by the importunity of the soldier, cried out so loudly that the King heard, forthwith had her brought before him and asked her why she called so lustily, to which she replied that he was using force. The soldier was arrested before he had a chance to escape and was brought into the presence of the King, who with his own hands committed a strange butchery, first of all cutting off, with a knife which he wore, his lips, his nose, his ears, his eyelids and his scalp; he afterwards broke all his teeth with a flint, without this poor unfortunate being able to utter so much as a sigh. Near Spahan I saw him hack with his scimitar several who had come near him, pushed by the crowd. Among others he killed one of our interpreter’s servants, giving him a blow on the head, which rolled the length of his neck, cleaving him to the very heart, which one saw moving and palpitating; the boy immediately fell to the ground, calling his master by name. When the King had heard this he asked the interpreter if the boy had belonged to him, to which he replied in the affirmative; and the King made answer, “Do not worry, I will give you another.” For my part, wondering why he thus ill-treats his subjects, the only reason I can find is that it is necessary to keep a tight rein on their innate bad instincts, for by nature these people are very dangerous, extremely greedy for money, liars, wantons, blackguards, drunkards, cheats, and in a word, base, worthless and entirely lacking in courage, although there are some modern authors who have praised them to the skies and commended the nobles of Persia for generosity and liberality; either their knowledge of the present state of this country is very poor, or they are not speaking of those of this century. For all, whoever they may be, excepting the King, are miserly, although in appearance they have some shadow of generosity and nobility. And to return to Scha Abbas, although he is so familiar with his people that he makes no scruple about entering the booth of a merchant and drinking with him, yet he is so feared by them that as soon as they see him they bow their heads to the earth as if they saw some divinity, crying in their language “Long live Scha Abbas.” And the most solemn oath that they have at the present time is to swear by his head, which they do thus: Scha Abbassom Bassi [Shāh ‛Abbāsin bāshī], and if one is ever to believe them it is when they swear that oath.

The King of Persia and his nobles take exercise by playing pall-mall on horseback, which is a game of great difficulty: their horses are so well trained to this that they run after the balls like cats. They also shoot with the bow on horseback, coursing at full speed; the target, of the size of a plate, is suspended on a tree and they often hit it and bring it down. They carry out these exercises in the public places of towns, to the music of drums [atabales], flutes, singing and those great horns or trumpets of which we have already spoken, which they play one after the other. I have seen the King exhaust seven or eight horses in such pastimes between noon and four or five of an evening, and I marvelled how they could endure such great exertion in the heat of the sun and the dust rising from the hooves of their horses. I have seen an exhibition of his force and dexterity when, stretched full length on the ground and taking one of the strongest bows, he bent it as if to discharge an arrow, and then, without using his hands or putting them on the ground, he raised himself with great agility from the earth with his bow bent; this seemed to me an invincible strength. He also takes great delight in the chase, and breeds more birds for hawk ing than I have ever seen elsewhere, falcons, tercels, vultures, merlins, with which they catch all kinds of birds that they meet: partridges, quail, pheasants, larks, rooks and others. By means of vultures they also trap a species of roe-deer which they call gazelles, which are very beautiful. They also catch these by means of leopards who creep along flat on the ground, and, when they see that there is a chance of springing up in three leaps and catching the animal, they attack it; and, if it so happens that it escape them, they fight and bite so angrily that they would kill each other, were it not that the huntsman strokes them, imploring them and telling them that they have done their duty well, but that fortune willed that their beautiful leaps should be in vain.

As for the religion, or rather the superstition, of this King, he is a Mahometan [Muhammadan], Nevertheless under his shirt and round his neck he always wears a cross, in token of the reverence and honour which he bears towards Jesus Christ. He had a crucifix of gold inlaid with divers stones of great price, but he gave this, in recompense for a small present, to a Portuguese monk of the Order of St. Augustine, who came from the East Indies and arrived in Persia while we were there. As for eating and drinking, he eats the flesh of the pig, which is not done by other Persians or Turks. It seems to me unnecessary to treat here of the origin of the Sophi of Persia, starting with Ismaël, who lived about a hundred years ago, and equally unnecessary to treat of the hatred and discord which exist between them and the Turks over the explanation of the Alcoran [Koran],1 and over the precedence and dignity of their false prophets, for there are volumes thereon written in every language, and I know that you have more knowledge of these things than all those who have written about them.1

I will only say that the Persians hold the Turks in great abomination, saying that they are impure in their law, and once every week a herald goes from square to square and market to market with an axe in his hand, which he holds aloft as high as he can, cursing the Turks and their adherents the while; and one sees several quarters which the present King of Persia has put to fire and sword because they inclined towards the religion of the Turks.

As for his revenue, from what I have been able to learn, it is not above three million chequins, and I believe his reserves are not large. As for the forces which he can put in the field, according to what I have been able to learn from certain Armenians who know his country very well, he can muster as many as forty thousand horsemen armed with bows and arrows, scimitars, shields and battle-axes. Infantry is held in poor esteem. Quite recently they have acquired some arquebuses. They have no artillery at all, nor corselets nor cuirasses, although there are some who have written that Selim in his war against the Sophi2 left there all the artillery which he had transported over the Euphrates, and that in that time all the Persians were clothed in heavy armour. It must be that these have been consumed by rust and mice. Many of the coats of mail which they wear are brought to them from Muscovy.

After the knight Sherley had stayed about three months in Spahan the Sophi sent him back to Christendom, with one of his nobles, bearing presents and letters addressed to the Pope, the Emperor, the King of France, the King of Spain, the Queen of England, the King of Scotland, of Poland, the Signory of Venice and the Earl of Essex, nevertheless he kept by him Monsieur Sherley’s brother for a hostage. His presents were not of much value. To each of the above-mentioned princes he sent nine scimitars, nine wrought and gilded bows with quivers and arrows of the same workmanship, nine pieces of the material of which they make their turbans, which they call seroiscia or, as some say, cessa,1 nine girdles of pure linen painted in the Indian fashion,2 nine more broad girdles made of the wool of the goat which secretes within itself the Bezoar stone. Before all these presents were ready to be transported there was much doubt about the route he was to take for his journey, for it was impossible to pass through Turkey, which is the shortest way, by reason of the letters and presents which he carried, also because, when he passed through Turkey he had given out that he was a merchant, but later he had been recognized as something other by Turkish agents at the court of the Sophi. To take his way through India was to throw himself into a labyrinth full of great difficulties, and it was to be feared that the Portuguese would not receive an Englishman in their ships or ports. It was decided that the best plan would be to go through Muscovy, although there was much difficulty even there. And to further this plan he wrote to the Grand Duke of Muscovy, begging him, for the sake of the alliance and fraternity which exist between them, to give passage through his land to the knight Sherley.

Having thus taken leave of the King and having received two thousand Persian chequins for the expenses of the journey, we returned to Casbin on our way to embark at Ghilan [Gīlān], a province bordering on the Caspian Sea. I believe that the province of Ghilan is that which the ancients called Hyrcania, for the sea itself is called the Hyrcanian Sea and the Sea of Bacchu [Baku]. Ghilan is situated on the territory of Casbin, which is a part of Media. The mountains there are so rugged and so difficult of passage that they are in no way inferior to the Alps, and it is not possible to carry baggage there on camels, but only on mules. In four days we came from Casbin to Rudassen [Rūdesar], which is a town of Ghilan, and near the roadstead where the King of Persia keeps the few vessels he has, which sail the Caspian Sea. One cannot imagine how great is the fertility of the province of Ghilan: as soon as one has passed the above-mentioned mountains there are fine pasturage, meadows, woods, and rich well-cultivated fields sown with wheat, rice, and all kinds of vegetables; any number of fine and beautiful trees; and especially important is the silk industry, for one finds men working at it everywhere. The countryside is so covered with white mulberry-trees and is so delightful that I often wondered why the King always lives on the other side of the mountains. They do not speak genuine Turkish in this district, nor Arabic nor Persian, but they have a particular idiom of their own.1 On our way from Media to Rudassen we found towns and villages furnished with all kinds of provisions, and very fertile fields: the best of the whole countryside is Langeron (Lenkorān). We were entertained everywhere. It is the custom in Persia that whenever an ambassador or personage of note arrives on a mission to the King, or on business in the country, he is entertained and the King provides him with soldiers to conduct him to the governors of the provinces, so that he lacks nothing. And if the peasants too do not bring what they have, God knows how they are beaten; I had no pleasure in seeing these poor people so maltreated.

We also had with us letters patent from the King addressed to a merchant of Rudassen who has control of all the traffic on the Caspian Sea, commanding him to equip a vessel for us immediately and to furnish it with a good pilot, with provisions and with everything of which we might have need. This was performed in seven or eight days. My provisions consisted of rice, biscuit, very good butter, and mutton which had been roasted, cut in pieces and powdered with salt; this was put into large jars which were then filled up with melted butter in order that it should not get spoiled; also live sheep, chickens, goslings, and, since there was no great quantity of wine in Ghilan, we had a plentiful supply of eau-de-vie.

The ships of this country are exceedingly strong, made of great beams and very thick boards; but they are badly polished, undecked, and have only one sail, one mast and two tillers made of two large planks which lie along the two sides of the ship, as if they were two great tails. If these ships are badly constructed, the sailors are even worse, and ill-versed in their trade; for they understand as much about the stars as pigs do about spices, and they never use the compass: that is the reason why they always keep close inshore, not daring to venture into the open sea. There are some who hold that the Caspian Sea is six hundred Italian miles long and four hundred miles wide, but I would not dare to believe that. The wind was violently contrary to us and we took six weeks to cross the sea, enduring terrible heat, for it was July and August. The gale was then very heavy, and although this sea is, properly speaking, only a lake, yet it is so subject to tempests that the pilots ought to know their calling somewhat better. On one particular day we were assailed by such a storm, such heavy rain and so devilish a wind that many of my companions, who had sailed the greater part of the coasts of the Indies and the European seas, said they had never seen the like; one of our helms was broken and we were nigh capsizing in the confusion. One heard a dreadful medley of voices and prayers. We of the Religion prayed in one way; there were some Portuguese monks who threw figures of the Agnus Dei into the sea to appease it, and muttered certain words, repeating “Virgin Mary”, “St John” and the In Manus. The Mahommedans invoked “Ali, Ali Mahomet,” but instead of all these I feared that the Devil would come to carry this rabble to Hell. But when we had been three hours in this storm God cast on us His eye of pity and delivered us. Here and there in this sea one meets stretches of fresh water, by which pilots well know that they are approaching port; this state is caused by the rivers which flow into it. As one approaches Astracan [AstraKhan] one enters a shallow expanse of fresh water which the sailors call “La Mer Douce,” and at the end of it in a certain place the Grand Duke of Moscovie keeps a garrison of Karagoli [Karakul]1—they are thus called in the language of Moscovie—who are a hundred poor soldiers who do duty both as soldiers and rowers on the rivers when they are needed; and, cowards as they are, they are sent to war when the affairs of the Emperor require this to be. When they are employed as rowers they wear large soutanes and carry an oar over the shoulder and an arquebus in the hand, and this they handle about as dexterously as an ox would a flute; they do not carry swords, because there is a law of the country which forbids it, for fear that, having drunk too much wine or eau-de-vie, they might commit some harm. They are shod with little high-heeled, low-toed boots which do not reach the knee, the men and the women generally wear these, and they have a wooden spoon attached to their girdle under their armpits; a large loaf of rye-bread, a small bag of salt with which to season their bread, and perhaps a fish being all in the way of provision; then they embark with their captain aussi vaillant qu’une quenouille, and that suffices them for ten days; as for drink, the river-water seems quite good to them, and they live joyously; for the rest they are great Sodomites. These honest people conducted us to Astracan in a day and a half by way of a river where they fish so many sturgeons, and so large, and make so much camaro,1 that it must be seen to be believed.

On the fourteenth or fifteenth of September the heat was excessive, and we were so afflicted and stung by gnats and midges that, in my opinion, the road from the garrison to Astracan was a veritable Hell, I was sent on ahead to announce the arrival of the Ambassadors from Persia to the governor of the place. It was an hour after noon when I arrived. I think that everyone in the town was asleep, excepting those who could not rest for hunger, for it is the custom of the country of this great prince to sleep from noon until four o’clock, when the bells begin to sound vespers; this is an inviolable rule in summer and winter alike, so much so that during these hours the most thickly populated towns in Moscovie seem like deserts. There are no hostelries, and no one of the country would dare to receive a stranger in his house without leave of the governors. That was the reason why we had to wait in the middle of the public square, surrounded by a great crowd of idlers who took much delight in gazing on us, until the governor should awake, As soon as the bells began to ring, the governor was advised of our arrival and sent Tartar interpreters to us; for we always used the Turkish language on our journey to Mosco. They asked us whence we came, what we wanted and whither we were going, and put many other questions to us in the square, the which they wrote down, together with our replies, and took to the governor. Finally they returned, turned one of the townsmen out of his house, and put us in it. Then the governor gave us one of his Caragoli for an attendant, and this man never went further from us than the threshold of our door. They generally give them to strangers, chiefly in order to spy what they are doing, and to see that no one of the country has intercourse with them and that they never go out to reconnoitre the fortifications of the towns, and to prevent the Moscovites, when drunk, from pillaging them: and also for a sign of their greatness, and to serve those who go there without attendants and may have need of them. Our daily fare was sent to us (for it is the Emperor’s custom to behave in this way towards ambassadors and others passing through his realm by his good pleasure), sheep, chicken, fish, beer, eau-de-vie, and money with which to pay for the small necessities of lodging: and they give more abundantly and in better order than is done in Persia, for here it is given by those who receive money from the Emperor, and the peasants are not forced to give.

The same day the governor sent a Baïar [Boyar], a captain of a hundred Caragoli, to receive Monsieur Sherley into the garrison, and the next day sent ships and provisions there to conduct him and his company of Europeans and Persians to Astracan: when they arrived they were led to their lodgings—the Persian gentleman to a separate one, and they were given attendants and food, The Sophi of Persia had sent another Ambassador expressly to the Emperor of Moscovie, with letters and presents and to rejoice with him on his accession to the Empire1; and, notwithstanding the fact that he had put to sea a fortnight before us, it happened that our company arrived at Astracan two or three days before him. He had a suite of forty, among whom were several Persian merchants and a gentleman who was chief falconer to the Sophi. He brought with him much merchandise, saying it belonged to his master, and this he wished to barter in Mosco for divers merchandise of Europe, such as woollen cloth, coats of mail, precious skins of animals— black foxes, sables and others—falcons and other birds for hawking, which sell for nothing in Moscovie. The merchandise which they brought from Persia consisted of satin, velvet, cloth of gold, many cotton materials and wide belts of silk. The Moscovites dress in these cloths, out of which they make quilted soutanes, and in robes of cloth brought to them from England, and were it not that Persia and England provide them they would have nothing in which to dress except the skins of wild beasts; for the wool of their sheep is too coarse and too rough, besides which they do not know how to dress it.

The Ambassadors stayed a fortnight in Astracan, until the vessels which were to take them to Mosco were equipped, and this fortnight was spent in feasting and rejoicing.

The town of Astracan is of medium size, almost round, and entirely built of wood, including the walls and towers; the castle is built of the same, but it is surrounded by a wall of small burnt bricks. It is the capital town of the kingdom of the Zagatay [Chaghatai] Tartars, which is also called Astracan; it is well situated on the beautiful river Volga, which affords the only outlet from this region to the Caspian Sea. That is why one sees many merchants there, Persians, Armenians and Japanese. There is a Moscovite governor, a kinsman of the Emperor John1 who died three years ago; he governs this country with secretaries, who are given to him as associates and without whom he cannot carry through any important business. This governorship is one of great value for, in addition to the importance of the post and the richness of the country, no Ambassador or merchant comes there without making him some honourable present. The town is peopled by a colony of Moscovites, The land is rich and fertile in corn, cattle and fruits, among the latter being very delicate melons and anguries.2 There are salt-mines (salines) which bring in great wealth, the rents of which, when added to the taxes, tremendously increase the Emperor’s revenue, It is the custom that when some Ambassador from Persia or other countries arrives in Astracan they immediately send a courier with all speed to Mosco by river in several boats, often changing rowers in order to arrive the sooner; they row night and day and advise the Emperor forthwith; and the stranger who has arrived there can go neither forward nor back until there has been a reply from His Majesty. And there have been those who awaited a reply for a year or two before being allowed to proceed. The delay happens sometimes when he does not like the embassy, for first of all the governor makes full enquiries and then informs his master of them. When we were passing through, there was a chief of a certain company of Tartars, who was much troubled to find himself detained there as a prisoner. However, we were not allowed to make a long stay because winter was near, and they feared the river might freeze. In the very hour of our arrival the governor sent a gentleman to Mosco.

We set out on the second day of October 1599, and Monsieur Sherley took a boat for himself and for his company of Europeans; the Persian Ambassador who has gone to Europe likewise took one for the transport of himself and the presents which the great Sophi was sending to the Christian princes. And he whom the Persian had sent to the Grand Duke of Moscovy took three boats by reason of his great suite and to carry the large amount of merchandise which he was bringing with him. All these were very well equipped with all kinds of provisions, enough for ten days and more, and with Caragoli rowers and their Basars [sic for Baïars] or captains, who serve as guides and couriers and prepare everything necessary for the journey. And all this is done at the expense of the Emperor of Moscovy, The vessels are very large and comfortable, with their cabins as long and broad and well-proportioned as any to be seen; and, since one’s course by the river Volga from Astracan to Mosco is upstream, in places where trees and other objects offer no impediment these Caragoli haul the boats by means of collars which they wear round their necks and hempen ropes round their waists; and they generally use their oars when they cannot haul the boats by strength of shoulder or when the wind is contrary; for their boats carry a very large sail, and when they sail before the wind they make good way. Thus is the custom in these countries, for it is very dangerous to go by land, by reason of certain Tartars and a host of ruffians called Cosacchi [Cossacks], barbarian robbers who plunder and kill travellers; one risks this danger as far as Cahan [Kazan], the capital town of the Tartary desert. And although this land between Astracan and Mosco is not inhabited in many parts, nevertheless the way is not so difficult as many people imagine; the river is most delightful by reason of its expanse, more especially because it is much wider than the Euphrates and the Tigris joined together, and also because it is bordered almost continuously on both sides by fertile woods; and the said river is so full of fish that one has but to throw in a hook to catch a fish immediately. Every evening they tie up, and everyone lands in order to take a walk; and along the river one finds great heaps of wood, which have been thrown up by the river when in flood, and this wood serves for cooking and for warming oneself, and it is so dry that one needs but to put a light to it for it to flare up. Thus progressing and passing up the river every other day one notices small towns which have beautiful castles, but their only means of resistance against Tartars are the wooden defences which surround them, such as we noticed in Astracan. Our Baïars, otherwise called Pristani,1 replenished our provisions from place to place, and our boats were unmoored in an instant without noise and without interference on the part of the poor who come to beg.

Before we landed we saw three castles almost equidistant one from another, and here was once the royal seat of the King of the Tartars, Vlochan [Ulugh Khān], being a mile from Cassan, The governor sent one of his nobles to us to greet the Ambassadors, and this man made an extremely ridiculous speech to them, the substance of which was that they were very welcome in the land of the Grand Duke, who was, he said, the greatest prince in the world; he lauded the governor in similar terms, and said that he was styled “Monsieur”. He made his speech in the language of Moscovie to one of his Tartar interpreters, who repeated it after in the Turkish tongue to our interpreter, who was a Greek by nationality, and “en trois secousses” we had from him the interpretation in the Italian language. Afterwards he had horses sent to us, on which to make our entry into Cassan, whither we were escorted by a troop of Moscovite Baiari [Boyars] on horseback, bearing whips and switches in their hands; for they are not yet used to spurs, and the horses do not respond to them, but as soon as they feel them begin to rear and kick as if they were mad. The governor of Astracan and the governor of Cassan are of the race and blood of the Emperor recently dead,1 who was called Boris Feritelli: the present Emperor is called Rorik, and his son Feodet Borisoich. The father was elected Emperor by the Patriarch and all the clergy, by the nobles, the soldiers and all the people,

1 Not identified.

2 Not identified.

1 Not identified.

1 See Manwaring, p. 190 and Index.

2 Abu Risha (a hereditary name) was the paramount chief of a tribe group who had their base at ‛Ana, and were independent of the Sultan of Turkey.

1 Ad-Deyr or Deyr az-Zur.

1 Not identified with any Muslim name.

1 Possibly Qādisiyya, which lies about ten miles south of Samarra.

1 Perhaps the Arabic badu—desert.

2 This, no doubt, refers to the zigurrat form of minaret, which is found also in Ibn Tūlūn’s mosque in Cairo.

1 The origin of this name is unknown. The Caliph Mu’tasim when he took up his residence there called it officially sura-man-rā’a, “he rejoiced who saw it”.

2 This is marked on de l’Isle’s map, but I have not identified it with any modern place.

3 Marked in de l’Isle’s map, and may stand for Sar-i-āb, i.e. “head of the stream”. Possibly the modern Qara Tepe.

1 ? Shāhraban, a village near Daskara. See le Strange, Lands of the Eastern Caliphate, p. 62.

2 Possibly the Karat Sirin of de l’Isle’s map—i.e. Qasr-i-hīrīn, where the scene of the famous romance of Farhād and hīrīn is laid. Pinçon may have mistaken these personal names for the name of the town.

1 Tanghi is not a place but merely tang—a pass. Tetang appears in de l’Isle’s map as a district.

Manwaring gives Tartange which stands for Dartang, the modern Zohāb.

2 Le Strange (op. cit., p. 63) says that the legend of Farhad and hīrīn is localized in many places in the surrounding district.

3 Bustards.

1 See Manwaring, p. 198, for variants of this name.

1 Not identified: possibly stands for Āb-i-Murād Khān.

1 This description of Bīsutūn is especially interesting in that the writer has taken the Achaemenian bas-relief for a Christian monument, and the Persian cuneiform for Greek.

2 ? Mandirābād shown on some maps between Kengaver and Asadābād.

1 John Ward: see p. 200

2 See de l’Isle’s map.

3 Possibly Imāmzāda Husayn, near Qazvīn.

1 Arabic tabl pl. atbāl, drum.

1 This is of course incorrect. Damaghan in the N.E. of Persia is said to occupy the site of the ancient Hecatompylos.

1 Referring of course to the Shi‘a Persians and the Sunni Turks.

1 This passage would seem to indicate that Pinçon’s narrative was originally in the form of a letter addressed to some European scholar acquainted with Arabic. I am not able to suggest his identity.

2 This refers to the battle of Chaldiran in 1514, and the capture of Tabriz by Sultan Selim I, who after occupying the capital for a few weeks again withdrew.

1 Sir William Foster tells me that the word serassa occurs many times in his English Factories for a cotton cloth exported from Gujarat or Masulipatam. He also refers me to Peter Munday (Vol. II, p. 154) where chassaes—i.e. khāssa—is a thin cloth made near Dacca.

2 The text which is obviously corrupt reads: “neuf ceintures de fin ou façonnés à l’Indienne.”

1 Pinçon is quite correct in saying the Gīlānis have a dialect of their own: but it is a form of Persian.

1 Karakul or Karāūl—sentinel.

1 This word has not been traced. Possibly a printer’s error for caviaro—caviare.

1 See Part I, p. 24.

1 Ivan, the father of Feodor, died in 1584: Pinçon’s Russian history is all astray. See also below, p.

174.

1 Apparently misreading of pristavi—“Zoverseers”. Pristanmeans a landing-stage.

1 This approximately fixes the date of Pinçon’s narrative. Boris died in April, 1605. I have failed to make any sense of Pinçon’s other names. Feritelli may be a corruption of Filaret, the name taken by Feodor, the father of Michael Romanov, when he became a monk.