Chapter Twelve

Trade Shocks and Response, 1979–1992

The 1980s were one of the most difficult periods in the history of US trade policy. The combination of two powerful macroeconomic forces—a severe recession from 1979 to 1982 and the significant appreciation of the dollar against other currencies from 1980 to 1985—squeezed domestic producers of traded goods, particularly in manufacturing. The United States also began running large trade deficits, which became a symbol of the country’s troubles with trade. The intensification of foreign competition meant that the political pressures for import restrictions increased dramatically.1 The Reagan administration responded by limiting imports in many sectors, but also resisted congressional pressure to do more, particularly with respect to Japan. The economic recovery starting in 1983 and the fall in the value of the dollar starting in 1985 eventually helped relieve the pressure on producers of traded goods and enabled the import restraints to be removed by the early 1990s. This period also saw the continued reversal of the historic partisan divisions over trade policy, as many Democratic constituencies were now hurt by imports, while Republicans constituencies stood to benefit from open trade.

Double Trouble: Deep Recession and Strong Dollar

The macroeconomic forces driving trade policy originated with a shift in monetary policy designed to stop inflation. In 1979, with consumer prices rising at about 12 percent a year, Federal Reserve Board chairman Paul Volcker started tightening monetary policy. This policy succeeded in reducing inflation, but also drove up real interest rates and produced the most severe recession since the Great Depression. The manufacturing sector was particularly hard hit: employment dropped 12 percent from 1979 to 1983, with massive layoffs in large, trade-sensitive industries such as automobiles and steel. The full force of the Federal Reserve’s policy was felt in 1982, when industrial production fell more than 7 percent, and the unemployment rate peaked at almost 11 percent by year’s end.2

The new administration of President Ronald Reagan also pursued an expansionary fiscal policy, cutting tax rates and ramping up defense spending. The combination of a tight monetary policy and a loose fiscal policy led to a growing fiscal deficit, high real interest rates, and a steady appreciation of the dollar on foreign-exchange markets. Between 1980 and 1985, the dollar rose about 40 percent against other currencies on a real, trade-weighted basis. The dollar’s appreciation dealt a crushing blow to the competitive position of domestic producers of traded goods. The strong dollar undermined exports by making American goods more expensive to foreign consumers and gave imports a significant edge in the domestic market by making foreign goods less expensive to consumers. Consequently, the merchandise trade deficit grew to reach nearly 3.5 percent of GDP in 1987. Only after the dollar began to depreciate in 1985 did the trade deficit eventually begin to subside.

Why did such large trade deficits, which were completely outside the range of previous historical experience, suddenly appear at this time? A fundamental change in the international financial system, discussed in chapter 11, now made large, sustained trade imbalances possible. In previous decades, trade imbalances had been small because the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates involved government restrictions on the international movement of capital. When countries could only buy and sell goods with each other, exports and imports had to be roughly balanced. When the fixed exchange-rate system finally collapsed in 1973, and countries adopted floating exchange rates, these capital controls were no longer necessary. As governments began to permit greater international capital movements, investors in different countries were able to buy one another’s assets as well. Consequently, financial flows between countries increased enormously.3 The increase in capital movements between countries allowed large trade imbalances to emerge. In the US case, other countries wanted to use the dollars they earned exporting to the United States to buy US assets rather than American-made goods. As a result, the dollar appreciated in value and exports began to fall short of imports as foreign investment in the United States surged.

Changes in Japan’s policy were particularly important. Japan had long been a country with a high savings rate and low interest rates. In December 1980, Japan liberalized capital outflows and allowed Japanese investors to purchase assets in the United States, a country with a low savings rate and relatively high interest rates. As a result, Japanese financial institutions began selling yen to buy dollars, so that they could purchase higher-yield, dollar-denominated assets.4 This drove up the value of the dollar in terms of yen on foreign-exchange markets. The appreciation of the dollar (or, conversely, the depreciation of the yen) made Japanese goods more price-competitive and American goods less price-competitive in world markets.

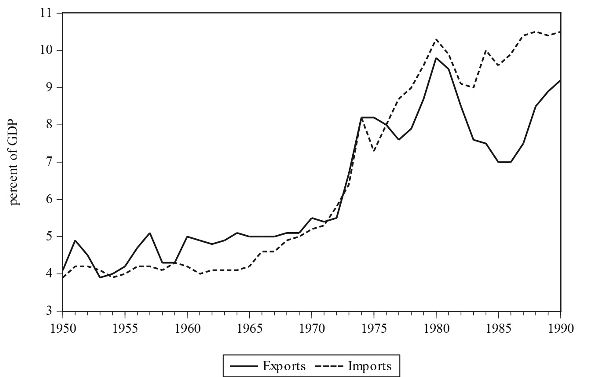

Both the severe recession and the strong dollar put export-dependent and import-competing sectors of the economy under enormous pressure. In the early 1980s, as figure 12.1 shows, exports fell sharply as a share of GDP, while imports were roughly unchanged. Yet this figure is misleading in suggesting that imports were not of growing importance in the domestic market. The value of imports relative to GDP did not increase much in part because the price of imports was lower due to the strong dollar, even as the volume of imports rose significantly. Over the period 1982–85, the volume of imports of semi-finished and finished manufactured goods grew 50 percent and 72 percent, respectively. Meanwhile, the volume of exports of semi-finished and finished manufactures grew only 9 percent and 1 percent, respectively.5

Figure 12.1. Merchandise exports and imports as a percentage of GDP, 1950–1990. (US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, www.bea.gov/.)

The strength of the dollar against other currencies also contributed to a significant change in the structure of the trade balance. During the 1970s, the overall trade deficit was driven by net imports of mineral fuels (petroleum) that slightly exceeded net exports of manufactured and agricultural goods. During the 1980s, as figure 12.2 shows, the trade surplus in agricultural goods continued, and the deficit in mineral fuels stabilized, but the trade balance in manufactured goods fell sharply into deficit. Starting in 1983, the United States became a large net importer of manufactured goods.

Figure 12.2. US balance of trade, by category, 1967–1990. (US Department of Commerce, Highlights of U.S. Trade, various issues.)

These developments led to an ongoing debate about the health of the manufacturing sector. Much of the concern focused on jobs. After rising by nearly 4 million during the 1960s, manufacturing employment oscillated between 18.5 and 21.0 million workers during the 1970s and 1980s. Large declines in manufacturing employment were seen in 1968–70, 1973–74, and 1979–82. In the first two periods, the declines were almost entirely cyclical, coinciding with recessions and largely unrelated to trade. But in 1981–82, when manufacturing employment fell 12 percent, a loss of nearly 3 million jobs, about a third of the employment decline was due to trade—the fall in manufactured exports and rise in imports—and the other two-thirds were due to the recession.6

Over the longer period from 1979–94, however, trade actually contributed to higher employment in manufacturing. Although manufacturing employment fell 13 percent during this period, Kletzer (2002) calculates that if exports and imports had been frozen at their 1979 level, manufacturing employment would have declined 16 percent. The reason is that both exports and imports of manufactured goods grew during this period, but exports are more tightly linked to job creation than imports are linked to job destruction. In particular, not all imports of manufactured goods are direct substitutes for domestic production: imports may be so different from domestically produced goods that they do not really compete with one another.7

Aside from these cyclical fluctuations, the economy was also undergoing long-term structural changes that resulted in significant employment shifts between industries. While some manufacturing industries were expanding employment, others were experiencing large, permanent declines in employment. Between 1977 and 1987, the number of production workers in the primary metals industry (blast furnaces and basic steel products) fell by 390,000, and employment in textiles and apparel fell by nearly 600,000. For these sectors, production cutbacks and plant closures led to mass layoffs of blue-collar workers. The term “deindustrialization” came into use, and images of shuttered factories across the Rust Belt, as the industrial Midwest came to be known, became etched in popular memory. On the other hand, employment in the transportation and electronics industries rose 350,000 over this period, and increased by 430,000 in printing and publishing.8

Despite the difficulties for workers, overall manufacturing output continued to grow through most of this period. Even during the severe recession of 1979–82 when manufacturing employment fell 12 percent, manufacturing production fell just 4 percent. Conversely, in the 1983–89 expansion, manufacturing production grew 36 percent, but employment rose only 4 percent. Production and employment were no longer coupled with one another: productivity improvements enabled output to grow without new workers being hired. This was due to changes in the composition of manufacturing output (the expansion of technology and capital-intensive industries, and the relative decline of labor-intensive industries), as well as the general improvement in labor productivity due to new technology and equipment.

Manufacturing also declined as a share of the economy during this period: between 1970 and 1990, manufacturing’s share of GDP fell from 24 percent to 18 percent. In view of the growing trade deficit, foreign competition was often blamed for the 6 percentage-point decline. But manufacturing’s share still would have fallen five percentage points over that period even if trade in manufactured goods had been balanced, as Krugman and Lawrence (1994) note. In other words, the overwhelming proportion of the declining share of manufacturing in the economy was due to non-trade factors, such as the shift in consumer demand from goods to services and the decline in the relative price of manufactured goods owing to rapid productivity growth. (Furthermore, manufacturing’s share of economic output was stable in real terms, suggesting that much of its declining share of nominal GDP was due to the falling relative price of manufactured goods due to productivity growth.)

However, the experiences of the 1970s and 1980s were different. In the 1970s, the United States had a growing trade surplus in manufactured goods. Trade expanded manufacturing’s share of the economy because exports of skill-intensive goods (aircraft and machinery) more than offset imports of labor-intensive goods (apparel and footwear). The story was different in the 1980s. During that decade, manufacturing’s contribution to GDP fell 3.1 percentage points, almost the same magnitude as in the 1970s, but manufacturing’s share would have fallen just 1.7 percentage points if trade had been balanced. Thus, more than half of the decline in manufacturing’s share of GDP in the 1980s can be attributed to the trade deficit.

The real issue confronting the manufacturing sector was an intensification of competition, driven as much by developments in technology as by foreign competition, which forced restructuring in almost every industry. Domestic firms responded to greater competition by trying to become more efficient, closing inefficient production facilities, and finding ways of maintaining production with fewer workers in order to reduce costs. Competition forced all domestic firms to reduce production costs, upgrade the quality of their products, or move into new lines of business in order to survive. Firms struggled to reduce costs and increase efficiency by adopting new technology, trimming the workforce, and reorganizing production. Of course, different industries adjusted in different ways. The automobile industry was driven to improve product quality and produce smaller, more fuel-efficient cars. The steel industry began to rationalize production by shutting down excess capacity. Labor-intensive industries modernized by substituting capital (machinery) for labor. In industries where capital or technology could not be substituted for labor, such as the assembly of consumer electronics or the manufacture of shoes, domestic production was likely to be sent abroad to take advantage of cheaper labor. Consequently, the labor-intensive assembly stage of production in many industries moved to other countries.

This restructuring across industries occurred regardless of its exposure to international competition: trade was only slightly related to cross-industry variation in worker displacement rates. Although industries with high displacement rates were often import-sensitive, not all import-sensitive industries had high displacement rates.9 Restructuring was usually achieved by reducing the number of workers employed rather than by cutting the wages of existing workers.10 Regardless of whether they lost their jobs because of changes in imports, improvements in technology, shifts in consumer demand, the displacement of workers from their jobs was a hard blow for those affected. The earnings of displaced workers often fell significantly when they lost their jobs. In particular, older, unionized workers received a substantial wage premium above the average worker in manufacturing and earned substantially less if employed elsewhere in the economy.11 On the other hand, workers in the labor-intensive sectors that were most vulnerable to competition from imports—such as footwear, leather products, and textiles and apparel—tended to be women and minorities with few skills. If displaced from their jobs, these workers often found employment at comparable wages elsewhere in the economy, because they were already among the lowest paid workers in the labor force.12

While unemployment rose sharply in the 1979–82 recession, the unemployment rate fell back down to 5 percent by the end of the decade. While trade did not affect total employment, it did affect the composition of employment across different sectors of the economy. Imports destroyed jobs in low-wage manufacturing industries (apparel, footwear, leather) and in some high-wage unionized sectors (autos and steel), while exports created jobs in high-wage industries (aerospace, machinery, pharmaceuticals). Unfortunately, the strong dollar prevented exports from keeping pace with imports in the early and mid-1980s, and both exporters and import-competing industries were squeezed. This pressure shifted employment out of the production of tradable goods and into the production of non-tradables, such as services.

Even in the absence of this pressure, the United States was increasingly becoming a service economy. As incomes rose, American consumers demanded more services, ranging from health care, education, and finance to recreation and leisure. Because labor-productivity growth in services was slower than in other sectors of the economy, the share of the labor force devoted to the production of services also had to increase to accommodate this demand. Just as workers in previous generations had transitioned from agriculture to manufacturing, the growing share of the labor force employed in services—which rose from 67 percent in 1970 to 77 percent in 1990—was part of a long-run trend. While the total number of workers in manufacturing was about the same in 1970 and 1990, their share in total employment fell from 27 percent to 17 percent. This development had little to do with trade: productivity improvements in manufacturing, due to the substitution of capital for labor in production and the advance of new technology, were far more important in explaining the declining share of employment in manufacturing than increased imports. Even if trade had been balanced, manufacturing’s employment share would have been only one percentage point higher than it was—18 percent instead of 17 percent—given the rapid growth in labor productivity in manufacturing.13

The confluence of these many different factors in the early 1980s led to concerns about the “competitiveness” of US manufacturing and fears about the “deindustrialization” of America. To be sure, some industries had fallen behind their foreign competitors in productive efficiency and product quality, and competition was forcing domestic firms to improve both or go out of business. However, the main problem facing manufacturers was not some deep-rooted structural issue, but an exchange rate that posed an enormous obstacle to its ability to compete in domestic and foreign markets. The 40 percent real appreciation of the dollar against other currencies over 1979–85 made it extremely difficult for both export-oriented and import-competing producers to remain price-competitive against foreign producers. The dollar’s appreciation reduced manufacturing employment in trade-impacted industries about 4–8 percent, on average.14 That domestic producers did not suffer from a structural “competitiveness” problem was demonstrated by the resurgence in manufactured exports and the pickup in factory employment once the dollar started depreciating in 1985.

In sum, increased imports were just one of many challenges facing the manufacturing sector in the early 1980s. Unlike a sharp decline in domestic demand, increases in productivity growth, intensified competition and technological change, and shifts in consumer demand, all of which significantly affected employment in manufacturing but were beyond the immediate reach of policymakers, restricting imports was an action that policymakers could take in order to help import-competing industries. Consequently, there was a sharp increase in protectionist pressures.

Emergence of Protectionism

The nation’s struggling economy was a key issue in the 1980 presidential election. While trade was not yet a major concern, the Republican nominee, Ronald Reagan, held out the prospect of import relief to drum up political support, particularly in the South. Reagan pledged to protect the textiles and apparel industry from further market disruption.15 Regarding automobiles, Reagan initially disavowed import quotas, saying that the industry’s problems stemmed from excessive regulation rather than Japanese imports, but campaign advisers floated the idea that Japan might “voluntarily” restrain its exports. While Reagan did not make an explicit pledge to reduce steel imports, he promised tax and regulatory relief for the industry and criticized the Carter administration’s decision to suspend the trigger-price mechanism, saying that trade had to be “fair.”

Reagan won the 1980 election on a platform of reducing government’s role in the economy. In their public pronouncements, the president and his administration appeared strongly committed to free trade.16 The administration’s July 1981 Statement on Trade Policy declared that free trade, a term that previous administrations had never explicitly endorsed, was critical to ensuring a strong economy. It vowed to “strongly resist protectionism,” yet warned that “the United States is increasingly challenged not only by the ability of other countries to produce highly competitive products, but also by the growing intervention in economic affairs on the part of governments in many such countries. We should be prepared to accept the competitive challenge, and strongly oppose trade-distorting interventions by government.”17

In fact, the Reagan administration was sharply divided over trade policy. Officials in some agencies (the Treasury and State Departments, the Office of Management and Budget, the Council of Economic Advisers) wanted to uphold free-market principles and reduce government intervention in the economy. Elsewhere, officials in the Commerce and Labor Departments representing the business community and labor wanted the government to help firms and workers struggling with foreign competition. Reagan himself was often conflicted between his strong belief in free enterprise and limited government and his desire to help out American industries and their workers.18

As a result, despite its free-trade rhetoric but in light of the tremendous shocks affecting traded-goods industries, the Reagan administration often accommodated domestic industries seeking relief from foreign competition.19 At critical junctures, the administration either made a political calculation about the electoral benefits of protecting large industries from imports, or restricted imports to forestall congressional legislation. Consequently, the share of imports covered by some form of trade restriction, after rising from 8 percent in 1975 to 12 percent in 1980, jumped to 21 percent in 1984.20 “For the first time since World War II, the United States added more trade restraints than it removed,” noted William Niskanen (1988, 137), a former economic adviser in the administration. He described policy in this period as “a strategic retreat,” in that the outcome, while not desirable in itself, was better than the most likely alternative, which was believed to be import quotas imposed by Congress. The administration’s strategy, he said, was “to build a five-foot trade wall in order to deter a ten-foot wall [that would have been] established by Congress.” This pattern can be seen by looking at trade policy with respect to automobiles, steel, textiles and apparel, and other goods.21

Automobiles

The automobile industry was the last major manufacturing industry to be affected by the intensification of foreign competition that began for most industries in the late 1960s. It was also the first to receive protection from the Reagan administration. The automobile industry was structurally similar to the steel industry: a few firms dominated the market (the Big Three: General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler), production was regionally concentrated (in the industrial Midwest), and a powerful union represented labor (the United Auto Workers). As in other industries, imports were not a major concern in the decades after World War II. In the 1960s, the foreign share of the domestic market was stable and less than 7 percent, mostly imports from Germany. As late as 1968, Japan’s market share was only about 1 percent. The Big Three ceded the low-margin, small-car segment of the market to foreign producers and concentrated their product line on the more profitable mid-size and large-car segment of the market.

This strategy was upended when the oil price shock of 1973 shifted consumer demand to smaller, less expensive, more fuel-efficient cars. Caught without a deep product line in this category of vehicles, the Big Three saw the foreign share of the domestic auto market nearly double between 1975 and 1980, as figure 12.3 shows, particularly from Japan.

Figure 12.3. Foreign automobiles as a share of US car registrations, 1960–1990. (Ward’s Automotive Yearbook [Detroit: Ward’s Reports], various issues.)

As Japan’s share of the market grew, the views of labor and management began to change. Unlike other unions, the United Auto Workers (UAW) had opposed the Burke-Hartke bill of 1971, but soon it was demanding that import quotas be imposed and that Japanese firms begin building cars in the United States. At this point, GM, Ford, and Chrysler did not want to restrict imports because they themselves had begun importing foreign-produced cars under their own nameplate. In 1975, the UAW charged twenty-eight foreign auto manufacturers in eight countries with dumping, but domestic producers did not support the petition because 40 percent of imported cars came from their subsidiaries, especially in Canada. The Treasury Department dropped the antidumping investigation after receiving assurances of corrective action from foreign manufacturers.22

A second oil price shock in 1979 combined with the severe recession of the early 1980s inflicted far more damage on domestic producers. The Big Three suffered enormous financial losses and cut back production, throwing about three hundred thousand auto workers out of work, while a greater number of workers in supplying industries lost their jobs as well. Chrysler was on the verge of bankruptcy until it received government-backed loan guarantees.

In the summer of 1980, Ford and the UAW filed a section 201 escape-clause petition for import relief. General Motors and Chrysler did not support the petition: GM imported small cars from Japan under its nameplate, while Chrysler did not want to alienate the Carter administration, which had given it financial assistance and was on record as opposing import restrictions. In November 1980, just days before the presidential election, the International Trade Commission (ITC) voted unanimously that the automobile industry had suffered serious injury as a result of imports, but in a 3–2 vote ruled that imports were not a “substantial cause” of serious injury and therefore the industry was not entitled to relief. This finding appeared to hinge on a technicality: under the Trade Act of 1974, a substantial cause is “a cause which is important, and not less important than any other cause,” meaning that imports had to be the most important cause of injury for relief to be granted. But the ITC determined that the growing demand for compact cars and the declining demand for large cars was a greater source of injury than foreign competition and, on this basis, the petition was rejected. Following that decision, both presidential candidates promised some form of aid for the automobile industry. The House also passed a resolution authorizing the president to negotiate limits on Japanese exports, and Senator John Danforth (R-MO) introduced a bill restricting the number of cars imported from Japan to 1.6 million per year.

In March 1981, shortly after President Reagan took office, Transportation Secretary Drew Lewis urged the president to “keep faith with our campaign pledge” and restrict auto imports from Japan. Budget director David Stockman (1986, 154) was appalled: “This preposterous idea was so philosophically inimical to what I thought we stood for that for a few moments I just sat back, concussed . . . here was a cabinet officer talking protectionism in the White House, not two months into the administration.” Reagan’s advisers were divided: Lewis, Commerce Secretary Malcolm Baldrige, and Trade Representative William Brock favored restricting automobile imports, while Stockman, Treasury Secretary Don Regan, and Council of Economic Advisers Chair Murray Weidenbaum were opposed. The split between the business advocates and the free-market proponents reflected a tension that was present throughout the Reagan administration.

The president was undecided but clearly sympathetic to the auto producers, noting that government regulation was part of the industry’s problem. He refused to threaten a veto of the Danforth bill, a clear signal to Japan that something was going to be done to limit imports if it did not restrain its exports. When presented with various options, Reagan favored the idea of asking Japan to “voluntarily” limit its exports of automobiles, and so this approach was taken.23 Stockman (1986, 158) remarked bitterly: “And so the essence of the Reagan administration’s trade policy became clear: Espouse free trade, but find an excuse on every occasion to embrace the opposite. As time passed, we would find occasions aplenty.” After being pressured by the administration, Japan soon announced that it would limit its auto exports to the United States to 1.68 million cars per year, a reduction of nearly 8 percent from the quantity exported in 1980. The voluntary export restraint would be in effect for three years, from April 1981 to March 1984, although the export limit could increase over this time.

The voluntary export restraint (VER) was not a new trade-policy instrument, particularly for Japan. More than any other country, Japan seemed to increase its exports in narrow product categories rapidly, causing problems for producers in importing countries. When cotton textile producers complained about excessive imports from Japan in the 1930s, Japanese producers decided to limit their own exports rather than face import restrictions imposed by the United States. In the 1950s, Japan adopted a number of VERs on products ranging from tuna to cotton textiles and stainless steel flatware.24 As noted in chapter 11, exporting countries generally favored VERs rather than having to face a tariff or quota imposed by the importing country. With a VER, exporters would profit from a quota-rent, the extra revenue that they received from charging a higher price in the protected market for their limited exports.

The auto VER was probably not binding on Japan’s exports in 1981 and 1982, when the severe recession depressed the demand for automobiles. As a result, the export restraint initially failed to provide much help for domestic producers. The UAW continued to demand that Japanese firms build production facilities in the United States to create more jobs at home. Congress also began considering domestic content legislation that would require all cars sold to contain a certain proportion (up to 90 percent) of US-made parts and labor or else face import quotas. In December 1982 and again in December 1983, the House passed a domestic-content bill with Democratic votes and Republican opposition, although in each case the Senate failed to take it up. While it was widely recognized that the president would veto the domestic-content bill, the House votes sent a signal to Japan about the domestic political problems caused by its exports.

The 1984 election played a role in Reagan’s decision to ask Japan to renew the VER, because he did not wish to alienate large numbers of voters in the industrial Midwest by lifting the restriction. As the economy recovered and automobiles sales rebounded, the VER became a binding constraint on Japanese auto sales in 1984 and 1985, though set at the higher level of 1.85 million vehicles. The economic effects of the VER are considered later in the chapter, but the export restraint and the opening of Japanese production facilities in the United States stabilized the import share of the market by the end of the decade.

Steel

The steel industry was also hit hard by the recession in the early 1980s. The large, integrated producers, including US Steel and Bethlehem, suffered enormous financial losses that forced them to reduce output and lay off hundreds of thousands of workers. Although steel imports declined with the collapse in demand, domestic production fell more rapidly. As figure 11.3 showed, the share of imports in domestic consumption rose from 15 percent in 1979 to nearly 22 percent in 1982.25

In January 1982, major steel firms filed 155 antidumping and countervailing duty petitions against forty-one different suppliers of nine different products from eleven countries, but aimed primarily at the EEC.26 The ITC ruled affirmatively in about half of these cases, but the prospect of long-lasting and severe tariff penalties on European producers, as well as highly varied antidumping duties being imposed across a range of countries and producers, was unattractive to all parties. To persuade the firms to withdraw their petitions, the Reagan administration brokered a new voluntary restraint agreement (VRA) that limited EEC exports to 5.5 percent of the US market in eleven product categories. European producers preferred the quantitative restrictions, because those would allow them to avoid steep antidumping or import tariffs and enable them to charge higher prices. The domestic steel industry also preferred this outcome, because it fixed the volume of imports (unlike the trigger-price mechanism or antidumping and countervailing duties, which affected the price) and applied to all EEC countries. Japan continued to restrict its steel exports by agreement, limiting them to 5–6.5 percent of the US market, depending upon the product.

The restraint agreements failed to provide as much help as the domestic steel industry had hoped, because imports grew from countries whose exports were not constrained by the VRA. The share of the market held by producers outside of Japan, the EEC, and Canada rose from 5 percent to 10 percent between 1982 and 1984. Thus, the overall foreign market share continued to climb, reaching 26 percent in 1984. Steel producers sought to plug the holes in this leaky system by filing more than two hundred antidumping petitions against imports from countries not party to the VRAs, such as South Korea, Spain, Brazil, Mexico, Poland, and South Africa.

In a further effort to block imports, Bethlehem Steel and the United Steel Workers filed a section 201 escape-clause petition in 1984. The ITC concluded that imports were a substantial cause of serious injury in five product categories, but found no injury in four others. The petition had been timed so that the president would have to make a decision about the ITC recommendations just eight weeks before the 1984 presidential election. The president was put in a difficult position: with about half of steel capacity located in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and West Virginia, many potential votes were at stake. The Congressional Steel Caucus pressed for a mandatory five-year quota limiting imports to 15 percent of domestic consumption. Reagan’s Democratic opponent in the election, former Vice President Walter Mondale, proposed capping the foreign market share at 17 percent.

Reagan rejected the ITC’s proposed tariff on the grounds that it was “not in the national economic interest to take actions which put at risk thousands of jobs in steel fabricating and other consuming industries or in the other sectors of the US economy that might be affected by compensation or retaliation measures to which our trading partners would be entitled” in an escape-clause action. Instead, he directed USTR to negotiate “surge control” arrangements or understandings with countries “whose exports to the United States have increased significantly in recent years due to an unfair surge in imports—unfair because of dumping subsidization, or diversion from other importing countries who have restricted access to their markets”—with the goal of “a more normal level of steel imports, or approximately 18.5 percent, excluding semi-finished steel.”27 Thus, the president went well beyond the section 201 case in promising to secure export-restraint agreements covering all segments of industry considered in the petition, even those the ITC turned down, against all major foreign suppliers of steel.

Of course, the restraint agreements still had to be negotiated. Steel imports surged in late 1984 and early 1985 before the market-share quotas could be finalized, prompting additional dumping and subsidy complaints against various European and Latin American countries. By August 1985, the product- and country-specific quotas of the VRAs were in place and covered fifteen countries accounting for 80 percent of steel imports. The VRAs were scheduled to expire in December 1989.

Textiles and Apparel

As Reagan had promised in the 1980 election campaign, the Multifiber Arrangement (MFA) was renewed for a third time in 1981. In effect from 1982–86, MFA-III reduced the annual growth of textile and apparel exports from developing countries from 6 percent to 2 percent and included tighter country-of-origin requirements and anti-surge and market-disruption provisions to limit export growth in sensitive categories. Over the course of the 1980s, the restraints were expanded to include other countries. By 1985, the MFA covered imports of textile and apparel goods from thirty-one countries in 650 separate product categories.

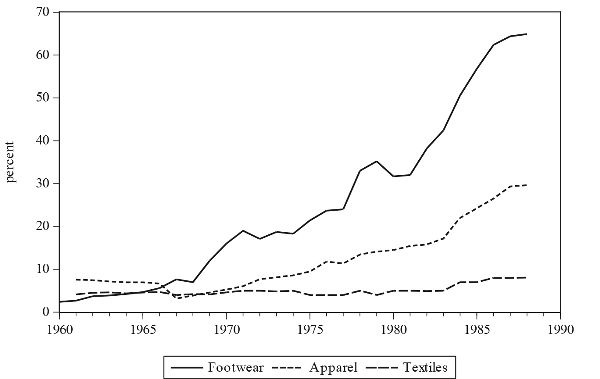

Like its predecessors, however, MFA-III failed to stem the rapid growth in apparel imports. This growth occurred because the quota allocations had grown over time, and some product categories were vastly underutilized. There was ample room for foreign exporters to expand their shipments by shifting products between categories and years: apparel from countries with filled quotas could ship their products to countries with unfilled quotas for some minor processing and then be exported to the United States. (For example, if a country’s exports of shirts hit the limit, it could export sleeveless shirts to another country with an unfilled export quota for final stitching.) Foreign producers could also alter their production mix, upgrading their products to take advantage of different limits in different categories. As a result, the protection provided by the MFA was a “screen rather than a solid wall,” as Cline (1990, 169) put it. The porous nature of the MFA allowed imports to surge in 1983 and 1984, fueled by the economic recovery and the strong dollar, and import penetration increased sharply, as figure 12.4 shows.

Figure 12.4. Imports as a share of domestic consumption, textiles and apparel, 1960–1988. Note: Textile mill products (SIC 22), apparel and other mill products (SIC 23), and non-rubber footwear (SIC 314). (US Department of Commerce, Industrial Outlook, various issues.)

Figure 12.4 also shows that import penetration was quite different for the textile and apparel industries. While the two were often lumped together, they were actually quite distinct. The textile industry produced fabrics and found it relatively easy to substitute capital machinery for labor and thereby improve productivity. Textile mills manufactured yarn, thread, carpets, and upholstery in highly automated mills located mainly in Georgia and the Carolinas. By adopting advanced technology, the industry shed workers but remained competitive: the import share was neither high nor rising, and some segments of the industry were able to export.

By contrast, the apparel industry produced clothing and garments. This involved cutting textile fabric and sewing and assembly operations—including pressing, dyeing, washing, and packaging—to convert it into clothing and other finished goods. This was a labor-intensive process that employed mainly unskilled women and minorities in plants spread out across Pennsylvania, the South, and southern California. Because production was necessarily labor-intensive, domestic firms found it difficult to innovate, keep costs low, and remain competitive against foreign producers who had access to low-wage labor. As a result, the share of the market taken by imports was rising rapidly and a much larger share of the job losses in the industry was due to foreign competition. Meanwhile, import penetration in the non-rubber footwear market, which was not protected after the failure of the OMAs in the late 1970s, surged as domestic shoe production plummeted.28

The MFA’s failure to stop apparel imports explains why apparel producers and allied textile firms, and particularly labor unions, made enormous political efforts to secure legislation that would tighten the restrictions on imports and slow the decline in employment. The textile and apparel industries remained one of the country’s largest employers in manufacturing, with nearly two million workers in the mid-1980s. Industry representatives argued that tighter import restrictions were needed to save jobs and that domestic production was critical for national defense. It succeeded in getting Congress to approve import limits in 1985–86, 1987–88, and again in 1990, only to have each bill vetoed by the president.

The first battle was over the Textile and Apparel Trade Enforcement Act of 1985, introduced by Rep. Ed Jenkins (D-GA). In pleading the industry’s case, Jenkins stated, “I know of no other industry or group of workers that has suffered more hardships than has the textile industry, as a direct result of cheap foreign imports.”29 The legislation would have reduced textile and apparel imports from 10 billion yards to 7 billion yards from twelve countries, mainly in Asia. The bill had more than 260 House cosponsors, and support came not just from the South, but also Pennsylvania (the home to many small mills) and even New England (although mills were fast dying out there).

This campaign ran up against widespread opposition. Some apparel manufacturers, such as Levi Strauss, had become importers and wanted the freedom to source from abroad. Retailers, such as Gap, JC Penney, and Kmart, opposed import limits and stressed the consumer interest in inexpensive clothing. Agricultural producers, represented by the American Farm Bureau Federation and other groups, feared foreign retaliation against their exports if the bill passed. Administration officials also rejected new import restrictions as a protectionist move that would jeopardize US negotiating goals in the next GATT round. The industry also suffered from bad press. The media portrayed the industry as an uncompetitive one that employed low-wage, unskilled workers who could get jobs in other sectors of the economy. The implication was that the shrinkage of the industry was inevitable and that the United States could do without domestic apparel production if it wanted to compete in high-technology sectors in the twenty-first century. Many members of Congress saw it as a low-wage, sunset industry of the past, not a sunrise, high-technology industry of the future.

Still, the House passed the Jenkins bill in November 1985 by a vote of 262–159; Democrats voted 187–62 in favor, while Republicans split 79–75 in opposing it.30 A month later, the Senate passed a less stringent version by a vote of 60–39, which the House accepted to avoid a protracted reconciliation process. To no one’s surprise, Reagan vetoed the bill. While he was “well aware of the difficulties” facing the industry and “deeply sympathetic about the job layoffs and plant closings that have affected many workers in these industries,” the president concluded, “It is my firm conviction that the economic and human costs of such a bill run far too high—costs in foreign retaliation against US exports, loss of American jobs, losses to American businesses, and damage to the world trading system upon which our prosperity depends.”31

Supporters of the bill delayed an override vote until the upcoming midterm election, hoping to force the administration to strengthen the expiring MFA. In July 1986, the Reagan administration announced a new, five-year MFA that included export limits on new fibers such as ramie, linen, and silk blends, new bilateral agreements with Hong Kong, South Korea, and Taiwan, the countries targeted in the Jenkins bill, and new safeguards to stop import surges. This was not enough to satisfy the labor unions, however, and the prospect of a close congressional override vote led the president to spend time phoning members of the House and asking for their support. In the end, the House failed to override the veto.32 In 1987, the industry and its workers again tried to get Congress to enact legislation that would cap overall textile and apparel imports at 1986 levels. The House passed the bill in late 1987 and the Senate followed a year later, but once again it was vetoed by President Reagan.

What explains the failure of the apparel industry and its workers to receive protection through legislation beyond that given in the MFA negotiated by the executive? Despite the efforts of the congressional Textile Caucus, the industry and its workers did not have as much political strength as might appear from the number of workers in the industry. Textile and apparel firms were divided about the merits of trade protection; textile firms were embracing new technology that enabled them to remain competitive, while apparel firms were increasingly sourcing their production from other countries. Advocates of import relief also encountered unexpectedly strong opposition from retailers, who put up a strong fight on behalf of consumers. Finally, the industry was already the beneficiary of the MFA, and its decline was not due to “unfair trade practices” by foreign governments. Import restraints were seen, at best, as a costly way of slowing the inevitable contraction of the industry.

Agriculture

Agricultural producers were also affected by the economic hardship caused by the recession and strong dollar. While farmers prospered during the commodity-price boom of the 1970s, they suffered when commodity prices collapsed in the early 1980s. Net farm income dropped by a third between 1979 and 1982, pushing farm indebtedness to record levels. Lower prices meant that it was more attractive for farmers to sell their crops to the government at the fixed price support than to sell them at the prevailing market price. As a result, the cost of federal farm programs escalated rapidly.

As government outlays to purchase and hold surplus crops grew, the Agriculture Department attempted to boost farm prices by reducing domestic production. This was done through acreage set-asides, in which farmers were paid to keep land idle. In addition, export subsidies were sometimes used to dispose of the government-held commodity stocks. These export subsidies put the United States on a collision course with the EEC, which had long been doing the same thing. One commodity, wheat, took on particular importance. Formerly a net importer, the EEC became a net exporter of wheat in the 1980s after it set domestic target prices so high that large production surpluses appeared. These surpluses were dumped on the world market using export subsidies. That policy, as well as the strong dollar, led to a sharp decline in foreign demand for American wheat. In 1983, the Reagan administration debated using selective export subsidies to reduce wheat stocks and punish the Europeans for distorting the world wheat market. The 1985 farm bill created the Export Enhancement Program to combat the EEC’s subsidies by providing for targeted export assistance to help American farmers increase sales in foreign markets.33 In one case, the United States displaced French exports by selling wheat to Egypt at $100 a ton when the US market price was $225 ton. Taxpayers were left to make up the difference.34

The United States was not alone in intervening in agricultural markets. The increasing use of domestic price supports, import restrictions, export subsidies, and other policies led to massive distortions in world agricultural markets. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) documented the extensive support that governments gave to agricultural producers: in 1986, about 23 percent of US farm income, 39 percent of EEC farm income, and 65 percent of Japanese farm income came from policy measures.35 Interventions in one country led to spillover problems in other countries. For example, the Common Agricultural Policy enabled the EEC to increase its share of world food exports from 8 percent in 1976 to 18 percent in 1981.36 This depressed world prices, which led to more import restrictions and more costly price supports in other countries. The agricultural subsidy wars of the early 1980s made farm reform a major US negotiating priority in the next GATT round.

With most American farmers trying to export their produce to world markets, the demand to cut agricultural imports was not strong, with the exception of sugar.37 In the 1970s, raw sugar was protected only by a modest import tariff. The 1981 farm bill established a new domestic price support program for sugar at a time when world prices were relatively high, but mandated that it involve no federal outlays. In 1981–82, the falling price of sugar exposed the contradiction of having a government price support program that did not allow for any budgetary expenditures. The only way to keep the domestic price high and avoid government payments was to restrict imports in a bid to keep the domestic price at the government’s target price.

To do so, the Department of Agriculture imposed emergency quotas on imported sugar in May 1982. This slashed sugar imports from 5 million tons in 1981 to 3 million tons in 1982. To comply with GATT provisions about non-discrimination, the quotas were allocated to countries based on their share of imports in 1975–81, when a non-discriminatory tariff was in place. As sugar prices kept falling, officials reduced the import quotas six times over the next two years, resulting in a 75 percent reduction in the sugar imports allowed from Caribbean and Central American countries.

The government’s attempt to restrict sugar imports to balance supply and demand at the target price sometimes pushed the domestic price of sugar to more than five times the world price. This enormous price gap made it profitable to import refined sugar products that were not covered by the quotas—including packets of iced tea and cocoa, boxes of cake mix, tins of maple sugar, and other high-sugar content products—and then extract the sugar for sale at the high domestic price. In 1983, the Reagan administration banned imports of certain blends and mixtures of sugar and other ingredients in bulk containers on the grounds that they interfered with the price support program. Foreign exporters of processed foods, particularly in Canada and the EEC, vehemently protested the move.

The high domestic price of sugar also accelerated the substitution of high-fructose corn syrup for sugar in food manufacturing. In 1984, Coca Cola and Pepsi announced that they would use corn syrup instead of sugar as the sweetener in their soft drinks. This sharply reduced domestic demand for sugar and required the Agriculture Department to slash the import quota by another 20 percent for all exporting countries. The high domestic price of sugar meant that sugar-using industries faced higher production costs in comparison to their foreign competitors, driving many candy and confectionary producers to other countries and reducing domestic employment in the food-manufacturing industry.

Finally, the sharp reduction in sugar imports led to foreign-policy problems. The quotas reduced the export earnings and damaged the economies of Caribbean and Central American countries at a time when many of them were struggling with the global debt crisis and even fighting Communist-backed insurgencies. The US move hurt relations with those countries, and so the United States tried to help them with other trade preferences, such as the Caribbean Basin Initiative of 1983. The sugar quotas also led farmers in the region to stop producing sugar and start cultivating illegal narcotics that were smuggled into the United States, starting a war with drug traffickers.

The United States compounded all of these problems in August 1986 when it decided to subsidize the sale of the entire accumulated stock of 136,000 tons of sugar to China. The government took an enormous loss; sugar had been purchased at 18 cents per pound but was then sold at just under 5 cents per pound. Within two days of the sale, the world price of sugar dropped more than 20 percent, from 6.3 cents to 5.0 cents per pound, to the outrage of sugar-exporting countries.38

The Rise of Administered Protection

As we have seen, three large and politically powerful industries—automobiles, steel, and apparel—all benefited from executive-negotiated agreements with foreign countries to limit their exports. For their part, farmers relied on government price supports to insulate them from fluctuations in world commodity prices. But what about the many smaller, less politically influential industries that also felt the pain of the recession and increased foreign competition? What could they do to obtain government relief from imports? Since these producers could not command the attention of Congress or the executive branch, they fell back upon the system of trade laws that allowed domestic firms to petition the government for temporary duties on imports.39

As we saw in chapter 11, the main legal avenues by which domestic firms could request trade protection were the escape clause, antidumping duties, and countervailing duties. The escape clause, based on section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974, was supposed to be the principal means by which industries harmed by imports could receive temporary relief from foreign competition. If imports of a particular good were found to be “a substantial cause of serious injury,” the ITC would recommend that the president impose a higher tariff, phased out over five years, on imports from all sources. The president had complete discretion about whether to grant import relief or not.

However, we also saw that, in most escape-clause cases, either the ITC failed to find that imports were a substantial cause of serious injury, or the president rejected the provision of any relief. After the auto petition was turned down in 1980, the ITC dismissed petitions on fishing rods in 1981, tubeless tire valves in 1982, stainless steel table flatware and non-rubber footwear in 1983, canned tuna and potassium permanganate in 1984, and electric shavers, metal castings, and apple juice in 1985. President Reagan did grant escape-clause protection to heavyweight motorcycles, some steel products, and wood shakes and shingles, but turned down relief for unwrought copper and another non-rubber footwear case that the ITC had approved. Given this record, domestic firms knew that they were unlikely to obtain much assistance using the escape clause and therefore few bothered to initiate cases. As Senator Fritz Hollings (D-SC) put it, “going the 201 route is for suckers.”40

Consequently, domestic producers turned to antidumping and countervailing duties. Figure 12.5 presents the number of antidumping and countervailing duty petitions filed from 1960 to 1990 and shows that the demand for trade remedies increased significantly in the 1980s. From 1980–93, 682 AD cases and 358 CVD cases were filed. Many of them (38 percent of AD and 55 percent of CVD cases) were filed by the steel industry as a way of forcing the president to negotiate VRAs with foreign exporters (after which the petitions were withdrawn) or as a way of closing the market to countries or products not covered by the VRAs.41 Regarding countervailing duties, petitioning firms had a significant burden of proof in having to demonstrate that the foreign exports were subsidized and a cause of material injury. The difficulty in proving the existence of subsidies meant that relatively few CVD cases were filed, except by the steel and chemical industries. Just 21 percent of the CVD cases resulted in duties being imposed, because they were often terminated or suspended when replaced by VRAs.42

By default, the antidumping law became the principal means by which small industries received some relief from foreign competition. The low burden of proof needed to find dumping and the high likelihood that duties would be imposed were the main attraction to potential filings. Congress also changed many of the provisions in the trade laws to encourage the filing of petitions and increase the probability of import duties as being the final outcome. Perhaps the most important procedural change came in 1979, when authority over dumping cases was shifted from the Treasury Department (which had little interest in the enforcing the statute) to the Commerce Department (which championed producer interests).

The antidumping process started with a firm or industry association filing a petition with the Commerce Department and the ITC alleging that imports from a particular country were being sold at “less than fair value” and causing “material injury.” Commerce made the “less than fair value” determination, and the ITC made the “material injury” determination. Under normal circumstances, foreign sales were considered “dumping” (sold at less than fair value) if a foreign exporter charged a lower price on its sales in the United States than in its home market.43 Commerce almost always ruled that dumping occurred: from 1980–92, dumping was found in 93 percent of all cases. Commerce often found large dumping margins: the average antidumping duty was 26 percent in the period 1980–84 and 41 percent from 1985–89. The average antidumping duty in effect in 1992 was 46 percent in non-steel cases and 27 percent in steel cases.44

Meanwhile, the ITC would determine if the petitioning industry had suffered from or was threatened with “material injury”—defined as “harm which is not inconsequential, immaterial, or unimportant”—as a result of the dumped imports. In making the injury determination, the ITC looked at such factors as changes in the industry’s output, employment, and capacity utilization. (Under the law, only the harm to domestic producers was considered, not the harm or injury to consumers or other domestic industries that might result from the imposition of additional duties.) The ITC made an affirmative injury finding in two-thirds of cases from 1980 to 1992, and about 40 percent of antidumping cases filed resulted in duties being imposed.45 In the 1980s, antidumping duties covered a wide array of products such as staples from Sweden, color television sets from Korea and Taiwan, raspberries from Canada, pistachios from Iran, candles from China, cut flowers from Colombia, and frozen orange juice from Brazil. However, because the goods subject to antidumping duties were narrowly defined products, the total share of US imports covered by such duties was less than 1 percent.

From the standpoint of domestic petitioners, the antidumping process had several advantages over the escape clause. First, the “material injury” standard in a dumping case was much less stringent than the “serious injury” requirement in an escape-clause case, making it more likely that the ITC would make an affirmative injury finding. The antidumping process also did not involve any presidential discretion: if Commerce and the ITC ruled in favor of the petitioner, antidumping duties went into effect automatically without further review. And unlike escape-clause relief, which was usually phased out over five years, antidumping duties could remain in place for an indefinite period. In the early 1990s, the mean duration of an antidumping duty was seven years, and about a fifth of such duties had been in place for ten or more years.46

However, unlike escape-clause duties, which applied to imports from all sources, antidumping duties only applied to imports coming from countries named in the petition. In other words, antidumping duties were selective and did not prevent other suppliers from expanding their exports when the targeted countries were hit. Such supply diversion made antidumping duties a leaky form of protection. For example, after antidumping duties were imposed on semiconductors from Japan, imports from Japan plummeted and production shifted to Taiwan. As Taiwanese semiconductor exports surged, they too were hit with antidumping duties. Then production shifted to Korea, where the same pattern repeated itself. Eventually, firms learned to file multiple petitions to cover imports from many different potential sources of supply.

As antidumping actions were increasingly used against imports, they came under criticism from economists. The administrative system strongly favored domestic petitioners and did not consider the interests of consumers, either downstream user industries or households, when such duties were imposed. Finger (1993, 13) argued that “antidumping is ordinary protection, albeit with a good public relations program” because it was based on the allegation of “unfair” foreign competition. The welfare cost of US antidumping and countervailing duty actions amounted to $4 billion in 1993—a considerable sum.47 Although US exports were adversely affected by the spread of antidumping to other countries, Congress favored the existing system so much that it refused to allow changes in the process to be negotiated at the multilateral level.

Assessing the Protectionism of the 1980s

Three questions can be posed about the new import restrictions imposed in the 1980s: What explains the type of policy instruments used? What were the economic effects of the import barriers? Did protection helped revitalize the protected industries?

The main policy instruments used to protect domestic firms from foreign competition were tariffs (antidumping, countervailing duties, or escape-clause actions) or quotas (export restraints). Generally speaking, the largest and most politically influential industries were protected from foreign competition through negotiated export-restraint agreements—textiles and apparel with the MFA, automobiles with the VER, and steel with the VRAs—whereas smaller, less politically influential industries had to file petitions for other trade remedies. Domestic producers liked the certainty that came with a specific quantitative limit on imports; foreign exporters also preferred an export quota because they could charge a higher price in the US market and earn a valuable “quota rent.”

The main difference between an import tariff and an export restraint is that a tariff generates revenue for the government while an export restraint generates a quota rent for exporting firms. Thus, an import tariff redistributed income from domestic consumers to domestic producers and the government, whereas an export restraint redistributed income from domestic consumers to domestic and foreign producers. Not surprisingly, foreign firms strongly preferred an export restraint to an import tariff, but the welfare consequences for the importing country were very different in the two cases. With a tariff, the losses to consumers exceeded the gains to domestic producers and the government by a deadweight loss that arose from the distortion of production and consumption. With a foreign export restraint or import quota, the losses included the deadweight loss and the much larger quota rent captured by foreign exporters. Furthermore, export quotas gave foreign firms an incentive to upgrade the quality of their products. This meant that they could move into the production of new, higher-end products and compete more directly with American producers.

In the 1980s, economists began producing quantitative estimates of the impact of various trade restrictions. For the first time, policymakers were confronted with an explicit calculation of the costs and benefits of trade protection. In almost every case, the costs of such restrictions to consumers and downstream industries exceeded the gains reaped by the protected domestic industry.48 For example, De Melo and Tarr (1992, 199) concluded that all major US trade restrictions in 1984 resulted in a net welfare loss of $26 billion, about 0.7 percent of GDP—about the same welfare loss that would have been generated by a 49 percent across-the-board tariff. Almost all of this loss—$21 billion of the $26 billion—was due to foreign export restraints in textiles and apparel, automobiles, and steel. About 70 percent of the $26 billion was due to the transfer of quota rents from domestic consumers to foreign producers; the remainder was due to the deadweight losses. Such findings suggested that the economic loss could have been significantly lower if tariffs had been used to protect domestic industries instead of export restraints or import quotas (or if the government had auctioned off the rights to import under the quota).49 Of course, foreign countries would have strongly objected if tariffs had been imposed, possibly even retaliating against them, whereas the quota rents compensated their exporters to some extent for accepting restrictions on their exports.

The Multifiber Arrangement (MFA) protecting the textile and apparel industry was the single most costly trade intervention of this period. De Melo and Tarr (1992) calculated that the welfare loss amounted to $10.4 billion in 1984, of which $6 billion was due to the transfer of the quota rent to foreign exporters.50 The MFA losses were large because of the high implicit barriers, the large volume of restricted imports, and the sizeable quota rents generated by the policy.51 The main purpose of the MFA, as with other import restrictions, was to slow the loss of jobs in the industry. Most estimates suggested that the MFA kept domestic employment in the textile and apparel industry higher than it otherwise would have been by about two hundred and fifty thousand jobs—about 10–15 percent of industry employment.52 Import restrictions could not stop the loss of jobs due to technological change; indeed, most of the fall in employment during this period was due to productivity improvements and the shift to more capital-intensive production methods, not declining output due to rising imports.53 The problem was that import restrictions were a costly and inefficient way of saving some jobs in the industry. The import restrictions were being used to save very poor jobs: average hourly earnings in the apparel and non-rubber footwear industries were among the lowest in all of manufacturing. The consumer cost of protection per job saved, which measured the total loss to consumers divided by the number of jobs saved in the protected industry, was more than $100,000 for industries in which the average worker earned perhaps $12,000 annually.54

By quantifying the consumer cost per job saved as a result of restricting imports, these studies put advocates of protectionist policies on the defensive. While some members of Congress were willing to have consumers pay this price with the hope that it would ensure the continued employment of their constituents, most policy analysts were less sympathetic. They pointed out that trade protection preserved jobs in relatively low-wage industries at the expense of high-wage jobs in export industries. Some analysts explicitly stated that these jobs were simply not worth keeping at that price. After studying the matter in relation to the textile, apparel, and non-rubber footwear industries, the Congressional Budget Office (1991, xi–xii) bluntly concluded that because “the estimated consumer costs are all higher than the average annual earnings of the workers. . . . it would generally be more efficient for government to allow the jobs to disappear and compensate any displaced workers who cannot find equivalent work.”

The second most costly trade restriction in the 1980s was Japan’s auto VER. If the VER had been removed in 1984, De Melo and Tarr (1992) calculate that the welfare gain would have been $10 billion, of which $8 billion was the quota rent transferred to Japanese producers. The restraint allowed Japanese exporters to increase their price by about $1,000 per car.55 The jobs saved in this industry were high-wage union jobs, but some analysts questioned the fairness of forcing consumers with lower average incomes than unionized workers to pay more for their cars to save the jobs of highly-paid auto workers. Others noted that export restrictions might ultimately hurt domestic producers because they gave foreign producers an incentive to upgrade the quality of products so that they could charge the highest possible markup on their constrained exports. For example, Japanese automobile producers, which had specialized in producing small, inexpensive, fuel-efficient cars, began producing larger, higher-quality vehicles that competed more directly with American brands after the VER was imposed.

Studies such as these provided greater information about the economic effects of trade restrictions, something that had been absent in previous discussions of trade policy. The findings of various studies bred widespread skepticism in policy circles about the wisdom and rationale for those restraints, giving members of Congress reason to pause before endorsing them. For example, in 1984 the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) was asked to evaluate the economic consequences of proposed legislation that would impose a five-year quota on imported steel that would cap the foreign market share at 15 percent. The CBO (1984) estimated that the quotas would raise the price of imported steel by 24–34 percent, increase domestic production by 6 percent, and boost steel-industry employment by 6–8 percent. However, by increasing the average price of steel by 10 percent (both domestic and imported), the quotas would reduce domestic steel consumption by 4–5 percent and lead to employment losses in steel-consuming industries that would roughly offset the employment gains in the steel industry. The fact that trade protection would not result in a net gain in employment (since it was an intermediate good used by other industries) was a strike against it. Furthermore, the CBO (1984, xv) argued that “there is little prospect that the quota would reverse the secular decline in the industry, since it does not address the underlying factors that have conditioned this decline.”

There was also little evidence that temporary trade protection helped protected industries adapt to the new world of global competition. In a report entitled “Has Trade Protection Revitalized Domestic Industries?” the CBO (1986, 101) concluded that “trade restraints have failed to achieve their primary objective of increasing the international competitiveness of the relevant industries.” Similarly, another study of the escape clause found that most industries receiving such protection were undergoing long, secular declines that limits on imports could not reverse. Looking back, the International Trade Commission (1982b, 86) concluded, “One observes how relatively little effect escape-clause relief had on firm adjustment either because so much of the firm’s injury was caused by non-import-related factors, or because the decline of imports following relief was small.”

These reports, among many others, identified two reasons for the failure of import restrictions to help struggling domestic industries. First, the restrictions were not very effective in reducing imports. The MFA was a porous sieve, Japan’s auto VER was not binding in its first two years and was then circumvented by foreign investment in the United States, and the steel VRAs and antidumping/countervailing duties could not prevent supply diversion. Indeed, most country-specific or product-specific trade restrictions were ineffective because of growing imports from new sources of supply or from new types of products. Despite an orderly marketing arrangement, machine tool imports were 10 percent higher in 1988 than in 1986 due to increased shipments from unconstrained suppliers.

Second, import barriers could slow but not stop the competitive pressures that were forcing producers to improve their efficiency. Like all labor-intensive industries, the textiles and apparel industry was modernizing and reducing employment only partly because of imports. In the textile industry, for example, the ITC report found that domestic producers of tufted carpets drove existing Wilton and velvet carpet producers out of business. The auto and steel industries also faced competitive pressure to increase productivity and improve product quality. By the late 1980s, an increasing number of Japanese auto producers had production facilities in the United States, meaning that import restrictions could no longer significantly diminish foreign competition. Similarly, the large, integrated steel producers had to fend off the rapidly rising market share of the small but efficient domestic mini-mills. The mini-mills had much lower costs than the integrated producers because they could process scrap metal instead of forging it from raw materials. By the early 1980s, mini-mills had captured about 20 percent of the steel market. The mini-mills were also responsible for the dramatic increase in the steel industry’s productivity in the 1980s and 1990s. While the industry lost about 75 percent of its workforce between 1962 and 2005, about four hundred thousand workers, shipments of steel were roughly the same in the two years, meaning that output per worker rose by a factor of five.56 Thus, steel producers would have faced massive restructuring even in the absence of foreign competition.

All of these cases illustrated what Robert Baldwin (1982) called the “inefficacy of trade policy” in helping struggling domestic industries.57 A classic example of the limitations of import restrictions was the celebrated Harley-Davidson motorcycle case, often heralded as the import-relief success story of the decade. As conventionally told, Harley-Davidson was pushed to the brink of bankruptcy by Japanese competition, but the company recovered quickly after it received temporary import relief in 1983 in an escape-clause case. In fact, import relief had little to do with Harley-Davidson’s turnaround. The early 1980s recession, rather than imports, had been the primary cause of the steep decline in demand for Harley’s products. The company’s resurgence came with the general economic recovery that began in 1983. Furthermore, Harley-Davidson mainly produced “heavyweight” motorcycles with piston displacements of more than 1000 cc, which were not imported because Honda and Kawasaki already produced them in the United States. Japanese producers mainly exported medium-weight bikes of 700–850 cc piston displacement, but Suzuki and Yamaha simply evaded the tariff by producing a 699 cc version that was not subject to the duty (initially set at 45 percent). Thus, protection had almost no impact on Harley-Davidson because Honda and Kawasaki were already manufacturing heavyweight motorcycles in the United States and other Japanese producers easily evaded the escape-clause tariffs on medium-weight bikes.58

If import barriers were so ineffective, why were they so often used? They arose as a second-best response to the inability or unwillingness of the president or Congress to adjust the underlying macroeconomic policies that were responsible for the strong dollar and the large trade deficit. The reality was that trade policies alone could do little to make the adjustment process less painful as long as the dollar continued to strengthen. Trade protection may have bought some firms more time to adjust, but ultimately it did not prevent large employment losses in labor-intensive industries. The main reason that most trade-sensitive industries began to perform better was that the economy began to recover in 1983, and the dollar began to depreciate in 1985. Trade protection played a very limited role in helping these industries, but it often imposed large costs on consumers.

Congress Threatens Action

While the Reagan administration protected several large American industries—automobiles, steel, and textiles and apparel—from foreign competition, it was still doing far too little to address the trade situation in the eyes of many in Congress. Legislators were frustrated by the administration’s apparent indifference to the growing trade deficit and the problems of struggling industries. In response, some administration officials argued that the trade deficit reflected the strength of the American economy and that the strong dollar reflected international confidence in the nation’s economy. To members of Congress, particularly those from regions struggling to cope with the recession and strong dollar, this benign interpretation showed a callous disregard for the difficult situation facing industries in their states and the lost jobs of their constituents. The pressure in Congress to “do something” about the trade situation came most strongly from the Midwest and the South Atlantic, where half of all import-sensitive employment was located, as table 12.1 shows. Both areas of the country saw large numbers of plant closings and the layoff of thousands of workers in the early and mid-1980s.

Table 12.1. Distribution of employment in trade-sensitive manufacturing industries, by region, 1990

| Region | All manufacturing | Industries sensitive to | Factory workers receiving trade adjustment assistance (1987–92) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imports only | Exports only | Both imports and exports | |||

|

Employment (thousands) |

19,143.3 |

1,391.9 |

2,117.6 |

412.9 |

314.9 |

|

Percent |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

New England |

6.4 |

8.2 |

8.7 |

11.7 |

8.0 |

|

Mid-Atlantic |

14.3 |

19.7 |

10.9 |

18.4 |

21.3 |

|

South |

23.9 |

26.0 |

14.2 |

15.8 |

28.0 |

|

Mid-West |

29.5 |

24.4 |

22.3 |

41.5 |

25.5 |

|

Oil States |

8.2 |

6.5 |

12.1 |

4.6 |

9.4 |

|

West |

17.8 |

15.3 |

32.0 |

8.1 |

4.8 |

Source: Shelburne and Bednarzik 1993, 6–8.

Note: As a percentage of GDP, figures may not sum to totals due to rounding.

The nation’s old manufacturing belt, which stretched from upstate New York through Pennsylvania and Ohio and into Illinois, was particularly hard hit. This region, shown in figure 12.6, was the location of heavy industry production, particularly automobiles and steel. It became known as the “Rust Belt” because it was where most of the nation’s “deindustrialization” was occurring. While national manufacturing employment rose 1.4 percent between 1969 and 1996, manufacturing employment in the Rust Belt fell by a third.59 The manufacturing jobs lost in this region did not come back even after the recession had ended and the dollar had declined in value, leaving the Rust Belt region depressed. Although unemployment rates in the Rust Belt returned to the national average within five years of the massive job losses experienced in the early 1980s, this adjustment took place almost entirely through the out-migration of people rather than in-migration of jobs or a change in labor force participation.60 Of course, the United States remained a large exporter of manufactured goods, so the Midwest had significant export-sensitive employment as well, but these industries also suffered under the strength of the dollar.

Figure 12.6. The Rust Belt. (Map courtesy Citrin GIS/Applied Spatial Analysis Lab, Dartmouth College; based on work by Brendan Jennings 2010, Benjamin F. Lemert 1933, and John Tully 1996.)