A minor setback. Even though you own the property out to the property line, you may not be allowed to add new construction beyond the setback line.

The planning and design phase of fence building involves much more than choosing a style, materials, and decorative elements. There are laws to satisfy (not to mention neighbors and homeowner association boards), as well as numerous design considerations, both practical and aesthetic. Many of your decisions will hinge on your answers to two big questions: 1) Why are you building the fence? and 2) How will the fence affect the look, the function, and the feel of your home and landscape? When you’re ready to take your ideas from the drawing board to the ground, a few simple layout techniques will help you get it right.

Fences often are subject to strict legal definitions and restrictions. Building codes, zoning ordinances, and homeowners associations may specify whether or not you can build a fence at all, what style of fence you can build, how high the fence can be, and how far it must be kept from a property line or street.

Start your research at your local building department, typically an office of city government. Many city websites include checklists that outline the basic rules and restrictions for fences, as well as what types of projects need permits. In addition, it’s also a good idea to talk with a department official to confirm that your fence plan meets all requirements — even if you’re confident you won’t need a permit. Be prepared to explain the fence in detail and where you want to build it (how close to the neighbors’ property, sidewalks, streets, and so forth). Your local building code may have minimal requirements other than those mentioned in this book.

You should also make preparations to have your property marked for underground electrical, plumbing, and other service lines. (See Before You Start Digging.)

If your fence project needs a building permit, your local building department will provide you with details for obtaining one. Be sure to find out what information you need to submit to the building department, how much the permit will cost, how long you are likely to have to wait to get it, and at what stage or stages you will need to have the fence inspected. If you plan to take your time building the fence, you should also ask how long the permit will remain valid; most permits are valid for no more than 1 year.

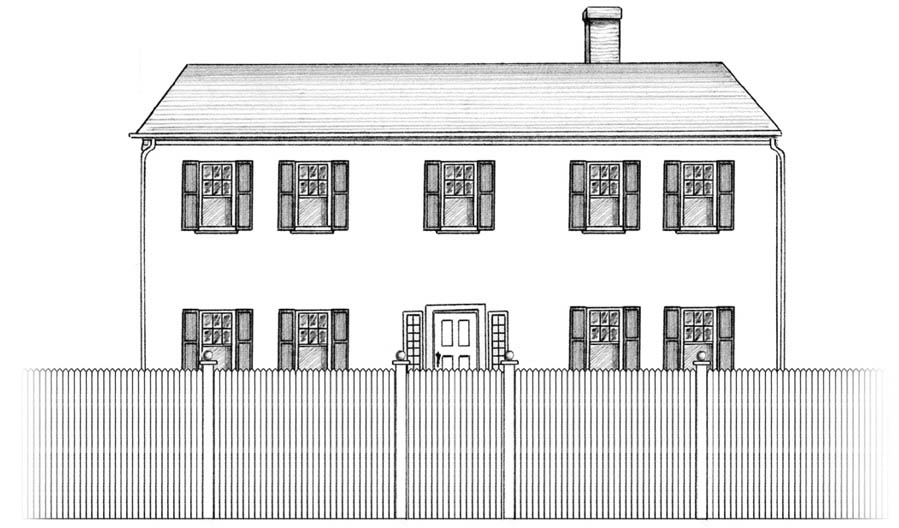

Most zoning laws relate to property lines and property use, both of which can affect your fence design. Common restrictions include a 3-foot height limit on fences facing the street and a 6-foot limit on side and backyard fences. Another restriction is the setback. Often, you can’t build a fence right up to the edge of your property line. Instead, you must set it back several feet from the line.

A minor setback. Even though you own the property out to the property line, you may not be allowed to add new construction beyond the setback line.

If you run into a code or zoning problem with a fence project, it’s worthwhile finding out exactly what the relevant board considers to be a “fence.” You may find that a fence is defined as something that is built, and not something that is planted. If you are prohibited from building a fence high enough to suit your needs, you may still be allowed to plant a hedgerow or some trees that can meet the height you need. Such a “living fence” offers little security and won’t corral animals, but it can be an effective privacy screen. And neighbors might be much less offended by some shrubbery than by a solid fence. Hedgerows can be created with trimmed shrubs, ornamental grasses, small evergreen trees, even living bamboo.

Another potential solution for building a fence higher than allowed is to offer to use a more transparent material, such as metal or lattice, on top of the solid lower portion of fencing.

A high, solid fence or wall (left) may not be allowed by local code, but you might be able to achieve the same effect by building a shorter fence and topping it with lattice (right) or vines.

If you want to build a fence 20 feet from the street, but a zoning law says it must be at least 30 feet away, you can apply for a variance (special permission to build something that violates existing requirements). Don’t hesitate to apply for one if you feel you have a legitimate argument, and be prepared to do some research and present a good case.

Take the time to understand the law and learn why your fence might not follow it. If the issue is public safety, such as with fences on corner lots restricting traffic visibility, you probably won’t win your case. On the other hand, if you want to build a privacy fence to block an unpleasant view but the view is uphill from the fence location, you might be able to successfully argue that a height limit of 6 feet is too restrictive for your needs.

An easement defines the rights of parties other than the property owner to use the property for specific purposes. For example, utility companies may have a right to drive their trucks through your property to tend to repairs. Shared driveway arrangements between adjoining properties are other protected areas.

Easements typically are noted in title reports (ask your title insurance company for a copy if you don’t have one), and it’s the homeowner’s obligation to know about them. A fence that violates an easement may have to be taken down at the owner’s expense. If you have any concerns about easements, it might be wise to discuss the matter with a real estate attorney.

Every major decision about fence design is best made with specific goals in mind. Often, various needs and functions overlap, which means you’ll likely have to prioritize and prepare for compromises. For example, if security is your sole objective, you might choose a type of fence that has little visual appeal. But if you also want your fence to be an attractive addition to your property, you may have to sacrifice a bit of security in favor of a nicer looking fence.

The two goals of privacy and security often go together in fence design, but not always. Privacy fences can substantially expand the usable living space of your house, turning much of your yard into functional outdoor rooms where you can sit, read, relax, and converse without feeling that you are on display. A good fence designer will think about privacy fences the way an interior decorator might think about walls, and try to create different colors and textures to help define different “outdoor rooms.”

Privacy is usually achieved by way of a high fence with solid or near-solid infill — the slats, planks, or other materials that make up the fence panels. Board fences are the most common choice, but a thick row of hedges could also achieve the same end result.

In a property with an open expanse of yard (left), privacy is confined to the house interior. Fences effectively enlarge the living space by expanding the privacy realm away from the house (right).

By contrast, a security fence is designed to discourage intruders from going over, under, or, in extreme cases, through the structure. Height and sharp edges can address the first concern, while strength and ground-hugging construction can handle the second. Chain-link fences are easy to install and relatively inexpensive (if unattractive) options for security. A wood fence is hard to kick through but easy to saw through. For combining good looks and solid security without blocking views, a fence made with ornamental metal is tough to beat.

Gate construction is frequently the weak link in a security fence. The hinges must be strong and fastened securely to both the gate and the post, and the latch should be lockable and jimmy-proof.

Boundary fences offer simple comfort, neither blocking views nor discouraging conversations. They define limits without excluding. Typically low and simple, a boundary fence subtly reminds neighborhood athletes that your front yard is not a soccer field, just as it encourages visitors to approach the house via the sidewalk. Many boundary fences are built simply for visual impact, perhaps to break the monotony of a large stretch of turf or to provide a backdrop for a garden or a support for climbing vines. Classic choices for boundaries include picket, post-and-rail, and ornamental metal fences.

Wind, snow, and noise can all be subdued with the right type of fence in the right place.

Fences for shade. Like shade trees that prevent the summer sun from heating up a house, a fence can shade a driveway, sidewalk, or patio to reduce heat buildup in the solid mass. It can also shade the side of the house from early morning and late evening sun.

Fences for windbreaks. In cold climates, wind contributes to heat loss. A fence can reduce the velocity of the wind striking your house and thus potentially reduce heating bills. Contrary to what you might think, a solid fence typically isn’t the best windbreak. It’s better to let some wind pass through, such as with horizontal louvered fence boards that are angled down toward the house. A hedgerow planted a foot or two away from a house wall can help redirect a cold breeze up and onto the roof. In warm weather, a windbreak fence can tame breezes and improve the comfort of outdoor sitting areas. Note: Windbreaks are effective only when placed perpendicular to the prevailing breeze, or as close to perpendicular as possible.

Fences for snow. A good windbreak fence can also control snowdrifts. Style and location are critical considerations. A solid fence creates deep drifts on both sides of the fence, while an open-style fence produces longer, shallower drifts and less snow buildup on the downwind side. Don’t place a snow fence too close to a driveway or sidewalk; it should be at least as far from the passageway as the fence is high. As with windbreaks, snow fences are most effective when running perpendicular to prevailing winds.

Fences for blocking noise. Noise is airborne vibration, so a dense barrier (such as a concrete or stone wall) is the best fencing solution for reducing noise. A fence made from solid wood is the next best choice. Because fences offer minimal noise reduction, the most effective strategy for noise reduction indoors is to soundproof the house.

Swimming pools must be surrounded by code-approved fencing. The United States Consumer Product Safety Commission offers guidelines for safety-barrier fencing (follow the link in Resources). More importantly, check with your local building department for specific requirements in your area. Typical recommendations include (but may not be limited to):

A dog fence needs to be only higher than your dog can jump. Typically, large dogs require a 6-foot-high fence and small dogs a 4-footer. If your intent is to keep other dogs out, plan on a 6-footer. Also remember that dogs can dig. Thwart a tunneling pooch by incorporating wire mesh fencing along the bottom. On the inside of the fence, extend the mesh straight down from the fence 3" to 4" into the ground, then bend the mesh and extend it horizontally about 2 feet.

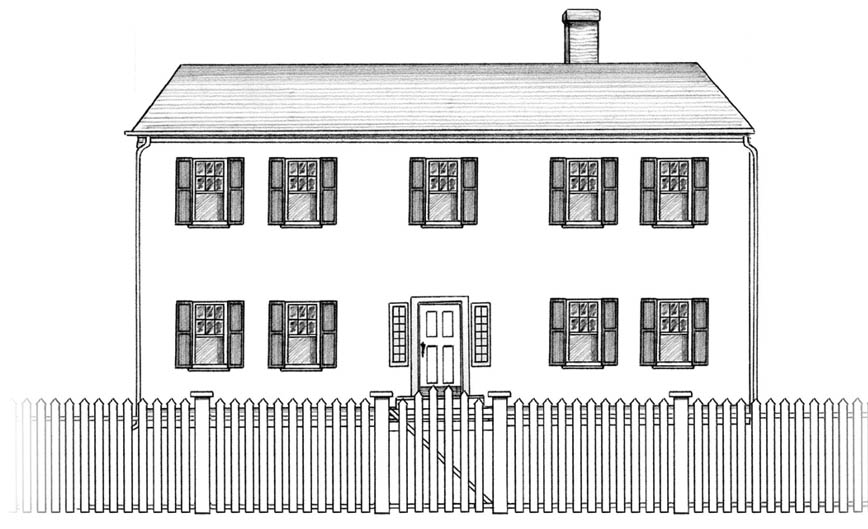

View your fence as an extension of your house. For inspiration, look to the trim around windows and doors. These accents could suggest decorative touches for the fence. Dominant posts on a porch may be a model for the fence posts (especially gateposts). Or you might be inspired by the house’s siding or finish materials. In general, long and flat houses look good with horizontally oriented fences, while a house with a prominent gable or complex roof lines might be better complemented with a fence composed of varying heights.

The high, solid, and more contemporary-looking fence both obscures the house and contrasts with the house style.

The lower, more open and more historically matching fence is a better fit.

This question of “open or closed?” relates to the fence infill, which can range from that of a high, solid privacy fence to a low, skeletal border fence. Closed fences offer privacy but also cut off your view of the neighborhood. Open fences provide less privacy but do not block off neighborhood views. When choosing an appropriate degree of enclosure, be sure to consider the views from inside the house as well as from the yard. Open fences tend to suit front yards, while closed fences might be better suited along the sides and back of a property. (On urban lots with small yards, high and solid fences can create a buffer against noisy sidewalks and streets, and create a beneficial “out of sight, out of mind” effect.)

Good designers are good observers. Take a walk or bike ride through different neighborhoods, or drive along some rural areas — camera or sketch pad in hand — with the single purpose of observing fences. You can search through magazines and conduct research online, but such activities are no substitute for looking at real fences in real yards. Don’t be afraid to stop and talk to homeowners about their fences. Do-it-yourselfers are almost always more than happy to talk about their creations and to share information about their expenses, frustrations, and lessons.

Security and privacy fences typically require a strong, solid gate with a lock. With other fences, the inclusion of a gate is a matter of choice. Many boundary and purely decorative fences are left gateless. A gate can serve as a decorative focal point or it can blend in almost invisibly with the fence. If you choose to gate your fence, read chapter 4. During the design phase it’s important to include any gates in your overall plan.

Contrast can be incorporated into fence design in two primary ways. The first is to differentiate the two sides of a fence. For example, with a relatively solid fence, the plain, simple face on the street side could be contrasted with a lush, decorative garden running along the fence’s interior. More simply, the fence could be a light color on one side and a dark color on the other.

Incorporating differing elements is the second way to provide contrast. Consider alternating high sections with low sections, open sections with closed, hard surfaces (wood or metal) with soft (hedges or other vegetation). You can even mix materials: both wood and metal fencing pair beautifully with brick columns and gateposts.

Height is most often related to the function of a fence. But height can involve additional considerations, such as legal restrictions (see Fence Law), as well as the view you wish to preserve or block, and the topography of your property. For example, a low fence placed atop a berm or small hill can provide as much privacy as a tall fence on flat ground. Think about where you will spend much of your time when either you are outside or you are looking outside from indoors: a 6-foot fence that’s close to the viewer blocks more of the view beyond than does the same fence placed farther away from the viewer. There are also technical considerations that affect the height of the fence: the taller (and heavier) the fence, the more securely it needs to be connected to the ground.

Some general rules of thumb can help you determine your fence’s height:

Time to hit the drawing board. Start with a camera, and take some shots of your property from different angles and depths. Drive stakes in the ground along the intended fence line, and then stretch a string line between them at the planned height of the fence. Include this mock-up in your photos.

Print out the best photos in 5" × 7" or 8" × 10" format, and then use a marker to draw your fence on the images. Repeat as needed until you feel comfortable with the results. Pay particular attention to the gate or entry sections as well as potential obstructions in the fence line (such as trees or existing gardens).

Note: If you haven’t done so already, now is a good time to have utility lines marked on your property (see Before You Start Digging). If you do have buried lines to contend with, mark their locations on your site plan drawing, and adjust your post layout accordingly.

Use a 50- or 100-foot tape measure to measure the length of the fence lines. On a sheet of paper, make a rough plan drawing with the dimensions. If you are planning a gate, be sure to note its location and size.

Refine your initial sketches. Then create scaled drawings that plot the plan view (the overhead or bird’s-eye perspective), the elevation (side view), and details (such as post ornamentation). Drawings allow you to work out important dimensions, confront potential obstacles, and calculate the quantity of materials. You can also use these drawings to obtain a building permit, if necessary.

Graph paper makes it easy to scale your drawings. Paper with a 1⁄4" grid is a good size. Use it to scale your designs such that 1⁄4" on paper equals 1 foot of actual distance. A ruler will help you to draw straight and accurate lines.

An architect or landscape designer could lecture for hours on the applications of scale and proportion in fence design, but here I’ll just slip you the crib sheet:

Scale: Make sure your fence isn’t too big or small for the house, keeping in mind that proximity matters. A fence that’s closer, taller, and/or more solid (dense or massive) has greater impact than a fence that’s farther away, shorter, and/or lighter.

Proportion: Use a simplified version of the ancient “golden section” design formula to calculate things like post spacing and the overall shape of your fenced area(s). The proportion ratio is roughly 5:8 (or 1:1.6). That means if your fence is 5 feet tall, the posts should be spaced 8 feet apart. A 6-foot fence looks best with posts spaced 10 feet apart.

If the footprint of your fenced area is square, you’re in good shape. If it’s rectangular, try to stay within the limits of the 5:8 ratio— for example, a 50-foot wide area should be no more than 80 feet long (if possible). The reason is that a square or nicely proportioned rectangular area feels like a room, while a long, narrow area can feel more like a hallway.

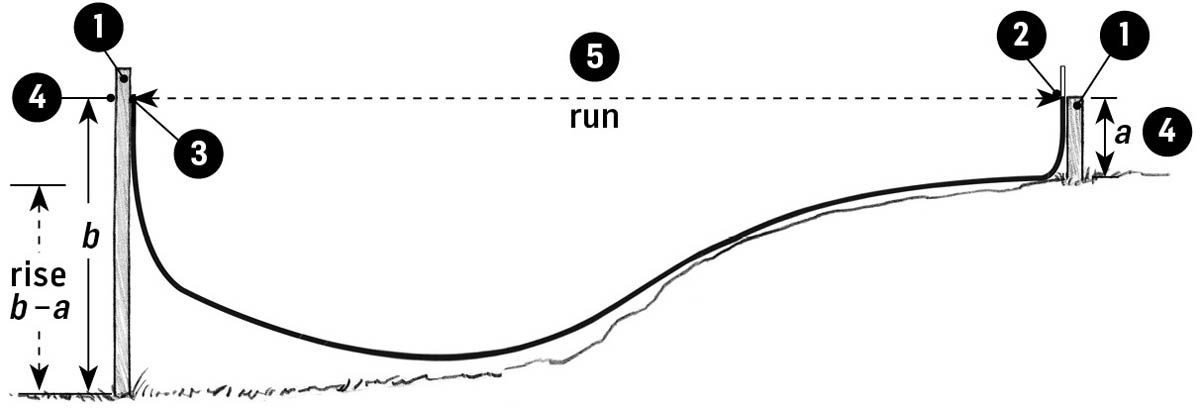

If your fence covers sloping ground, measure the slope’s grade to determine which style of framing to use for the fence. If you decide to use a stepped framing technique, you should also work out the size of each fence section. For most do-it-yourselfers, it’s easiest to measure slope with a water level (see Using a Water Level).

Chart the slope on your graph paper: Draw a level baseline along the bottom, then plot the run and rise, and then draw a line to indicate the slope. Lay some tracing paper over the drawing and divide the fence into sections with equally spaced posts. Use these drawings to help decide which of the following framing methods will work best.

Stepped framing. Works well on gradual slopes. Calculate the rise of each section by counting the total sections and dividing the rise (in inches) by the number of sections. The end result looks best with evenly spaced posts and an equal distance between the tops of the posts and the infill.

Sloped framing. The fence mirrors the slope. A good choice for steep slopes or rolling terrain.

Hybrid framing. Employs stepped framing, with the infill cut to match the slope. Best for very steep slopes.

Ideally your fence line is not interrupted by trees or other obstacles. But if it is, you can pass around the obstacle with a little bump-out in the fence, or you can incorporate the obstacle. However, don’t fasten a fence to a tree; over time, this can damage both the tree and the fence. Instead, place a post several feet away at either side of the trunk, then let the rails and infill overhang the posts enough to fill in the gap.

The basic carpentry principles of plumb and level are critical to fence building. Let’s start with the essential terminology:

Plumb means perfectly vertical. A plumb post maximizes the force of gravity by transferring its load straight down to the earth. Any deviation from plumb weakens that force, and it also looks bad.

Level means perfectly horizontal; that is, to the horizon.

Square refers to a 90-degree corner, or a square or rectangular frame made up of four 90-degree corners.

A post level quickly straps to wood posts (or magnetizes to metal) and has three vials for quickly checking for plumb at a glance. This tool is simple to use and is very handy if you’re working alone. However, its small size means limited accuracy.

Checking for plumb and level requires only one tool: the simple carpenter’s level. The single best tool for fence building is a 4-foot level, while a 2-footer can be especially handy at times. Keep in mind that a level provides a read only on the surface on which it’s placed. Generally speaking, the longer the level, the more accurate the reading. I like to set posts using two carpenter’s levels, attaching them to adjacent sides with Velcro strips. This allows me to keep an eye on all four plumb vials before bracing the post.

Check a post for plumb with levels on two adjacent sides.

To transfer level lines from one post to the next, strap a level onto the edge of a straight 2×4 that’s longer than the post spacing. Hold one end of the 2×4 on your reference line, raise or lower the other end until the bubble centers in the middle vial, then mark the spot on the other post.

A water level is a traditional, effective, and cheap tool for finding level over long distances. It’s nothing more than a hose or long tube filled with water. The water levels itself at both ends of the hose, no matter how many twists and turns the tubing makes.

You can make a water level with any length of 3/8" or 5/16" clear vinyl tubing. Alternatively, you can use a garden hose that is fitted with water-level ends (available at home centers and hardware stores). There are even versions that beep to indicate level, which is handy when you are working alone. One warning about water levels: If one part sits in the shade and another part sits in direct sunlight for a long period of time, the water temperature (and, thus, the water density) will differ between the two areas, producing misleading results.

To use a water level, make sure there are no air bubbles or kinks in the tubing, and keep the ends open. Set one end of the tubing so that the water level aligns with the reference you have previously marked. Then place the other end of the tubing in the desired location. Once the water stabilizes, the water level at one end will be level with the water level of the other end.

For fence building, a laser level is the high-tech alternative to a water level. Small handheld versions are pretty affordable these days (and they’ll likely prove useful for future jobs around the house). But laser levels are not effective when leveling over long distances, especially outdoors. A better option is to rent a professional-grade rotary laser level. These levels can send a beam up to 100 feet and include a sensor unit that detects the beam, meaning that bright outdoor light will not interfere with the visibility of the laser light. Laser units with a self-leveling feature simplify setup. Regardless, make sure you get a tutorial before leaving the rental center.

Slope is a measure of rise (vertical distance) over run (horizontal distance).

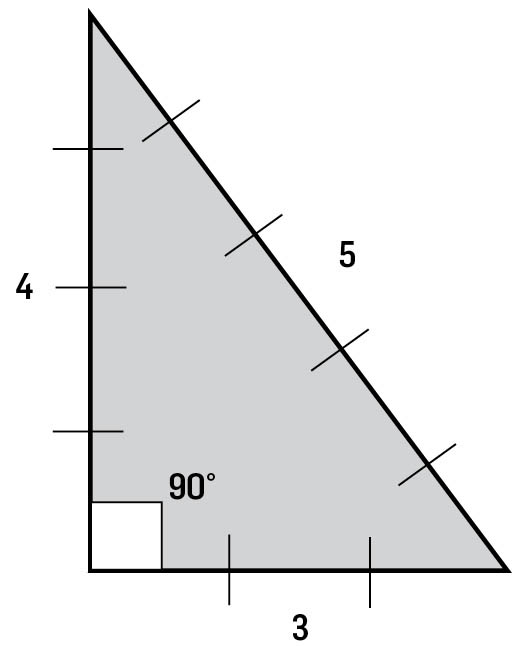

If your fence line needs to turn a corner, in most cases you will want the turn to create a perfect right angle. The easiest way to do this is to use the 3-4-5 technique (otherwise known as the Pythagorean theorem: a2 + b2 = c2). Measure along one side of the fence line and make a mark at 3 feet, then measure along the perpendicular side and mark at 4 feet. Finally, measure the diagonal between the marks. If the distance is 5 feet, the corner is square. You can scale up the numbers for greater accuracy. For example, 6-8-10 or 9-12-15.

using the 3-4-5 technique to turn a corner

Most fences require that you dig some holes for the posts. Before you pick up your shovel, however, make sure that you know what you are likely to encounter underground. Drainpipes; water and gas supply lines; septic tanks and drainage fields; and cables for electrical supply, telephone, and cable or satellite TV are all frequently buried. Knowing if you have any such underground obstacles on your property — and, if so, exactly where they are — is information that you as a homeowner should have, regardless of whether you are building a fence. Although there is not necessarily any problem with building a fence that passes over a buried cable or pipe, you certainly do not want to encounter such objects when you dig your postholes.

Having your lines marked now is easier than ever before: Pick up your phone and dial 811 (in the United States) to reach the national “Call Before You Dig” hotline. Your call will be routed to a local One Call Center. Explain the details of your project to the center operator, and the center will notify all of your local utility companies with lines on your property. Within a few days, a representative will come out and mark your lines — for free.