Party Realignment and American Industrial Structure: The Investment Theory of Political Parties in Historical Perspective

1. INTRODUCTION

IN MID-SEPTEMBER 1912 a gentleman representing Woodrow Wilson, the Democratic nominee for president of the United States, came calling on Mr. Frank A. Vanderlip. At that time Vanderlip was one of the most prominent businessmen in America. Quoted frequently in the press and recognized as a leading Progressive, he served on the boards of 12 major corporations, including E. H. Harriman’s Union Pacific Railroad, the mammoth U.S. Realty and Improvement Co., and four sizable banks. He was also a trustee of New York University and the Stevens Institute, a member of the executive committee of the New York Chamber of Commerce, and active in the National Civic Federation. Most important, however, he was president of the National City Bank of New York, after J. P. Morgan & Co. probably the most important bank in America.

Nothing in the record suggests that the banker felt any embarrassment at receiving the envoy of a party associated in American folklore (and much subsequent academic writing) with straitened Southern and Western farmers. It is easy to understand why: the visitor was Henry Morgenthau Sr., himself a director a dozen corporations (including the big, multinationally oriented Underwood Typewriter Co.) and a major figure in Manhattan real estate.

As was his custom with anything important, Vanderlip later wrote a detailed account of the encounter to James Stillman. Along with William Rockefeller (younger brother of the even more famous and wealthier John D.), Stillman had been prominently associated with the bank for many years. He was probably its largest stockholder. Now retired in France, he superintended the bank by remote control. Almost every other day brought a long letter from Vanderlip, describing his activities and decisions. After reading the letters, Stillman would write back his comments and instructions, dispatching them once in a while by secret courier or sometimes sending them in code. Because the months prior to the 1912 election had been filled with acrimonious controversies that importantly affected National City, especially the discussions of what eventually became the Federal Reserve Act, Vanderlip could be sure of Stillman’s attention as he related how

I had a two-hour session with [Charles D.] Hilles, the chairman of the Republican Campaign Committee, and one of equal length with Morgenthau, who is Chairman of Wilson’s finance committee, and who is, with [William G.] McAdoo, practically directing the campaign. Hilles is not hopeful. I think the most [William Howard] Taft really hopes for is to get a larger vote than [Theodore] Roosevelt, although he believes that sentiment is swinging back to him some, and there is some evidence of that. . . . I had a very thorough going over of the administration with Hilles and I must say the result did not improve my views any of its efficiency. There never has been any clear understanding in the White House in regard to the National City Company [National City’s newly organized and controversial securities affiliate], and the whole disposition was to avoid trouble and to pass the question along. My conversation with Morgenthau left me more pessimistic about the political outlook than I have been at all. I am afraid not a great deal that is good is likely to come out of a Wilson administration. At least, I am afraid that a good deal that is foolish and ill considered may come out of it. I think Wilson is really pretty well imbued with the “Money Trust” idea, and I fear he lacks the sincerity that I believed at one time he had. Morgenthau told me positively that it would not be his plan to have any extra session of Congress and that he proposed to take up banking legislation before the tariff; that he favors a central bank and one of the arguments he proposed to use is that the people are now under all the evil conditions of an unrestrained central bank, through the operations of the “Money Trust”; that there is a “Money Trust” that is practically a central bank, without any legislative control, and that they might much better replace it with a real central bank that will do them some good and will be controlled. I can see how just such stuff as this would appeal to Wilson’s mind, but I am disgusted with his thinking and using such clap trap. He has told Morgenthau that the Aldrich Bill [which many major American banks sponsored] never can be passed, because it bears the Aldrich name. They have got to get up another bill which he supposes will have to be about 60% the Aldrich Bill to start with and probably will be 80% before they got it passed, but it must have another name.

This is about as scientific an attitude toward the banking question as you would expect from Tim Murphy. Morgenthau tells me that [New York attorney Samuel] Untermeyer is preparing for a thoroughgoing campaign to begin after election—I believe the date is November 20th—and has got a lot of men working on it now. His whole ambition is to, in some way, get a white-wash for his character. He has offered a hundred thousand dollars (all of this is quite confidential, of course) if he can be assured of a foreign mission. Indeed, he would give any amount for an important one, and has even the audacity to think that he might possibly be appointed to England. Wilson will make no promises whatever and they have accepted only $10,000 as yet and probably will accept no more. He would also like to be Attorney General. Morgenthau says that, of course, is quite impossible, although he could imagine that he might be sent to some post of about the grade of Italy.1

As a primary source for the study of modern American politics, this letter is uncommonly rich. Even on casual reading it brims with exciting implications for a wide range of issues now extensively debated by social scientists and historians—the impact of financial innovation on American political development, for example; or the relationship between congressional investigations (like that Untermeyer had just directed into banking practices on behalf of the so-called Pujo Committee) and the evolution of the national political agenda; or the role of professionalization in U.S. diplomacy of the period; or the significance of class and, perhaps, ethnic factors in elite politics. With more deliberate attention to the letter’s historical context and stylistic idiosyncrasies still more would be revealed. A reading that was sensitive to the political choices other leading businessmen made during the same election, for instance, could certainly throw rare light on several first-order mysteries of the great American organism of that epoch, notably the delicate balance of rivalry and cooperation that characterized the “Money Trust” before World War I, and the precise ways in which the preferences of its members, allies, and opponents translated into party politics and public policy.

But perhaps the most important reflections suggested by this correspondence concern this essay’s central theme: the primary and constitutive role large investors play in American politics. For much about this missive’s tone and contents—the famous banker’s condescension toward the White House (where “the whole disposition was to avoid trouble and to pass the question along,” while—as Stillman and Vanderlip were both well aware—securing National City’s vital interests); the Olympian assurance which acts as though nothing could be more natural than that top operatives of both major parties should drop by for intimate campaign discussions; or the matter-of-fact disdain with which Vanderlip relates to Stillman that the “Archangel Woodrow” (as H. L. Mencken called him) doesn’t really believe what he is saying about what was probably the campaign’s prime issue—bank reform—and that he has no plans to appoint Untermeyer, the archenemy of the big banks, to high diplomatic post—almost irresistibly raises a series of subversive doubts about the basic conceptual framework that most recent studies of American politics rely on to understand the workings of the political system over time and as a whole.

As summed up in the “critical realignment theory” elaborated by a succession of scholars since the late 1950s, this view understands political change primarily—though of course not exclusively—in terms of changing patterns of mass voting behavior.2 Most American elections, it considers, are contests within comparatively stable and coherent “party systems.” While any number of short-term forces may momentarily alter the balance of power within a particular party system, and cumulative, long-run secular changes may also be at work, the identity of individual party systems rests on durable voting coalitions within the electorate. So long as these voting blocs (which in different party systems may be defined variously along ethnic, class, religious, racial, sexual, or a plurality of other lines) persist, only marginal changes are likely when administrations turn over. Characteristic patterns of voter turnout, party competition, political symbols, public policies, and other institutional expressions of the distribution of power survive from election to election.

“Normal politics,” of course, is not the only kind of politics that occurs in the United States. The “critical realignments” of critical realignment theory refer to a handful of exceptional elections—those associated with the New Deal and the Great Depression of the 1930s, the Populist insurrection of the 1890s, the Civil War, and the Jacksonian era are most frequently mentioned, though other dates have also been proposed—in which extraordinary political pressures find expression. Associated with the rise of new political issues, intense social stress, sharp factional infighting within existing parties, and the rise of strong party movements, these “critical” or “realigning” elections sweep away the old party system. Triggering a burst of new legislation and setting off or facilitating other institutional changes that may take years to complete, such elections establish the framework of a new pattern of politics that characterizes the next party system.

With few exceptions, the higher stakes involved in realigning elections do not sway realignment theorists from their emphasis on popular control of public policy.3 The sweeping changes in the political system that occur are again ascribed to voter sentiment. By raising the salience of political issues, most analysts suggest, critical elections facilitate a large-scale conversion of new voters from one party to another, or a mass mobilization of new voters into the political system. Either way, the partisan division of the electorate alters decisively.

An illuminating and sophisticated variation on classic liberal electoral themes, critical realignment theory continues to be widely held by both social scientists and historians. It has also inspired increasing numbers of journalists, consultants, and political activists professionally concerned with interpreting political events. But in recent years skeptical appraisals of the theory have proliferated and many of its claims have come in for heavy criticism (Lichtman, 1976, 1980, 1982; Kousser, 1980; Benson, Silbey, and Field, 1978; Ferguson, 1986).

The pivotal arguments raised against conventional versions of critical realignment theory undermine precisely the aspect of the theory that the Vanderlip-Stillman exchange challenges so vividly: the inspired confidence in what might be termed “voter sovereignty.” As several studies have argued in detail, evidence is mounting that the durable voter coalitions which are supposed to underlie party systems never existed, and that so-called critical realignments are not only very difficult to define, but simply have not witnessed major, lasting shifts in voter sentiment.4 In the words of one sophisticated quantitative study of American voting patterns by three scholars very sympathetic to the realignment perspective (Clubb, Flanigan, and Zingale, 1980, p. 119),

[E]lectoral change during the historical periods usually identified as realignments was not in every case either as sharp or as pervasive, nor was lasting change as narrowly confined to a few periods, as the literature suggests. Although these periods were marked by both deviating and realigning electoral change, which shifted the balance of partisan strength within the electorate toward one or the other of the parties, these shifts did not involve the massive reshuffling of the electorate that some formulations of the realignment perspective describe. Moreover, indications of substantial continuity of the alignment of electoral forces across virtually the whole sweep of American electoral history can be observed. . . . [E]lectoral patterns do not, by themselves, clearly and unequivocally point to the occurrence of partisan realignment.

To this evidence of massive public policy change without correspondingly sweeping electoral realignment, and other difficulties, adherents of critical realignment theory respond variously. The common denominator in virtually all their replies, however, is a determination to shore up the theory by making it even more complicated, “more multidimensional.” The hope is to supplement the already complex electoral analysis with more and more variables—conducting more detailed studies, for example, of the president and the electorate, Congress and the electorate, the president, Congress, and the electorate, etc.5

But it is doubtful that such moves will do more than postpone the inevitable. As an earlier paper argued (Ferguson, 1986), adding baroque variations to already complex themes is likely only to generate rococo variations on the same themes—and provide very little additional illumination. Nor are these efforts likely to constitute an effective reply to the direct evidence emerging from both quantitative and case studies indicating that the relationship between public policy change and party platforms, electoral margins, and voting behavior is weak and unstable.6

It is time, therefore, to recognize that the chief reason why no social scientists have succeeded in specifying unambiguous electoral criteria to identify “partisan realignment” may well be that there are no such criteria to be found. And it is high time, accordingly, to begin developing a different approach—a fresh account of political systems in which business elites, not voters, play the leading part; an account that treats mass party structures and voting behavior as dependent variables, explicable in terms of rules for ballot access, issues, and institutional change, in a context of class conflict and change within the business community.

The present paper represents an attempt to revise conventional accounts of American party systems and critical realignments along precisely these lines. Parties, the paper argues, are not what critical realignment theory (and most American election analyses) treat them as, viz., as Anthony Downs defined them in his celebrated formalization of the liberal (electoral) model of parties and voters, the political analogues of “entrepreneurs in a profit-seeking economy” who “act to maximize votes” (Downs, 1957a, pp. 295 and 300). Instead, the fundamental market for political parties usually is not voters. As a number of recent analysts have documented (Burnham, 1974, 1981; Popkin et al., 1976; Ginsberg, 1982), most of these possess desperately limited resources and—especially in the United States—exiguous information and interest in politics. The real market for political parties is defined by major investors, who generally have good and clear reasons for investing to control the state. In a two-party system like that of the United States, accordingly, incidents like those recounted in Vanderlip’s letter to Stillman are far more typical of U.S. parties than the usual median voter fantasy. Blocs of major investors define the core of political parties and are responsible for most of the signals the party sends to the electorate.

During realignments, I shall argue, basic changes take place in the core investment blocs which constitute parties. More specifically, realignments occur when cumulative long-run changes in industrial structures (commonly interacting with a variety of short-run factors, notably steep economic downturns) polarize the business community, thus bringing together a new and powerful bloc of investors with durable interests. As this process begins, party competition heats up and at least some differences between the parties emerge more clearly.

Since the business community typically polarizes only during a general crisis, it is scarcely surprising that in such cases voters also begin to shake, rattle, and roll. Only if the electorate’s degree of effective organization significantly increases, however, does it receive more than crumbs. Otherwise all that occurs is a change of personnel and policy that, because it may reflect nothing more than a vote of no confidence in the current regime, bears no necessary relation to any set of voting patterns or consistent electoral interests. Assuming that the system crisis eventually eases (possibly, but not necessarily, because of any public policy innovation), the fresh “hegemonic bloc” that has come to power enjoys excellent prospects as long as it can hold itself together. Benefiting from incumbency advantage and the chance to implement its program, the new bloc’s major problem is to manage the tensions among its various parts, while of course making certain that large groups of voters do not become highly mobilized against it—either by making positive appeals to some (which need not be the same from election to election) or by minimizing voter turnout, or both.

The discussion comprises the following major sections.

Section 2 outlines the basic notions of the investment theory of parties and applies them to the problem of critical realignment. This effort involves two separate tasks: first, to explain clearly why voters can only rarely define public policy through elections; second, to indicate how businesses (and, in some party systems, labor or middle-class organizations) importantly influence or control political parties and elections. Now the first problem, the paper argues, has already been completely solved by recent contributions to the so-called economic theory of democracy developed by Downs and other theorists. Also, the paper proposes that by pursuing the logic of the arguments developed in one of these recent essays, “What Have You Done for Me Lately? Toward an Investment Theory of Voting” (Popkin et al., 1976), an easy solution materializes to the second—the question of how elections and policies are in fact controlled. Building on these arguments, the present paper contrasts the “investment theory of political parties” point by point with conventional voter-centered models of elections. As part of this exercise, the paper reconsiders aspects of Mancur Olson’s famous analysis of The Logic Of Collective Action to gain a clearer view of the unique advantages major investors enjoy in providing themselves with what look to all other actors in the system like “public goods” (Olson, 1971).

How to test the theory is considered next. Section 3 begins with a brief discussion of criteria for recognizing “large” investors and similar definitional issues. To demonstrate the existence and stability of the investor coalitions that the theory posits, the paper develops a method for the graphical analysis of industrial (and, where necessary, agricultural) structures. By analyzing how blocs of investors whose interests center in different parts of the economy map into multidimensional issue space, this technique produces spatial models of the distribution of major investors within the political system—models that can be estimated with actual data to reveal whether a coalition really exists. When analyzed developmentally, such models can also indicate whether these coalitions are becoming more or less coherent.

Section 4, the longest part of the paper, presents a series of sketches of the major investor blocs that have dominated the various party systems in American history. Necessarily stylized and subject to further revision, these accounts largely bring together research gathered for longer studies which have appeared or will appear separately.

Finally, section 5 ties up loose ends and considers the possibilities for enhancing the power of ordinary voters in advanced industrial societies in light of the investment theory of parties.

II. FROM ELECTORAL TO INVESTMENT THEORIES OF POLITICAL PARTIES

Ironically, it was Anthony Downs’s classic formalization of the liberal theory of elections and public policy which took the first and perhaps most important step down the path toward an alternative account. For by the middle of An Economic Theory of Democracy, Downs (1957a, p. 258) concluded:

The expense of political awareness is so great that no citizen can afford to bear it in every policy area, even if by doing so he could discover places where his intervention would reap large profits.

This and similar observations led Downs into a pathbreaking analysis of the costs and benefits of becoming informed about public affairs and choosing between alternative courses of action. At several points Downs recognized that the logic of an information cost model potentially undermined democratic control of public policy, for if voters cannot bear these costs they have no hope of successfully supervising the government.7 But Downs did not finally give much empirical weight to this possibility, and his work became famous as a demonstration of how voters controlled government policy in countries similar to the United States.8

More recent analysis has demonstrated, however, that serious application of Downs’s ideas about information costs to actual political systems leads to many striking conclusions, which stand both traditional voting analyses and Downs’s preferred models of democratic control on their heads.

The most important of these contributions is that of Samuel Popkin and his associates. A pioneering attempt to incorporate the cost of obtaining and processing information into the analysis of voter behavior, their paper presents a detailed critique of the conventional “socialization” approach to partisan identification and mass political choices. In this view, which work done during the 1950s on The American Voter (Campbell, et al., 1960) appeared to support, an individual’s attachments to political parties are shaped by non- or a-rational group and family socialization experiences involving a minimum of cognitive orientation.9 By reanalyzing data presented in several earlier studies along Downsian lines, however, Popkin et al. demonstrate that the orientation of most voters toward politics is and has been primarily cognitive rather than affective.

Following a path Downs himself briefly explored,10 Popkin et al. suggest that voters are only acting rationally when they cut information costs by using shortcuts like partisan identification or demographic facts to evaluate complex vectors of political variables. But—and here lies one major part of their paper’s interest for this essay—Popkin et al. (1976, p. 787) also provide a clear argument and a series of vivid examples illustrating how, in a political system like that of the United States, where even highly motivated voters face comparatively enormous costs when they attempt to acquire, evaluate, and act upon political information, effective electoral control of the governmental process by voters becomes most unlikely:

[T]he understanding that information is costly leads to expectations about the voter which differ from those of the SRC or citizen-voter [i.e., “socialization”] model. Whereas citizen-voters are expected to have well developed opinions about a wide range of issues, a focus on information costs leads to the expectation that only some voters—those who must gather the information in the course of their daily lives or who have a particularly direct stake in the issue—will develop a detailed understanding of any issues. Most voters will only learn enough to form a very generalized notion of the position of a particular candidate or party on some issues, and many voters will be ignorant about most issues.

As a consequence it is not necessary to assume or argue that the voting population is stupid or malevolent to explain why it often will not stir at even gross affronts to its own interests and values. Mere political awareness is costly; and, like most of what are now recognized as “collective goods,” absent individual possibilities of realization, it will not be supplied or often even demanded unless some sort of subsidy (at least in the form of advertising) is supplied by someone.11

To further clarify the issues involved in the decision to participate in collective action under uncertainty, Popkin et al. introduce their most striking idea—the notion that political action should be analyzed as investment, with “the simple act of voting” requiring at least an investment of time and attention as a limiting case.12

Now, this suggestion has many exciting implications—too many implications, indeed, for this paper to assess. Consider, for example, how non-Downsian it is at its core. Though Popkin et al. generally claim they are following Downs, conventional neoclassical exchange theories provide the basic framework for most of Down’s work. While, as mentioned earlier, Downs pioneered the analyses of investment, he did not pursue the sweeping implications of his results. As a consequence, in his presentation investment enters largely as a further complication in a more detailed model of voter control. Because investment does not really emerge as a prominent theme in its own right, neither Downs nor later analysts who share his methodological bent have fully recognized the implications of their own theory. As Joan Robinson and other critics of neoclassical microeconomics have observed, even the simplest acts of investment imply change over time and accordingly are almost impossible to incorporate into the general equilibrium framework that Downs himself champions as an ideal (Robinson, 1971, Chap. 1). Similar logic also inspires John Roemer’s insufficiently appreciated observation that much politically relevant behavior involves shattering the boundaries of what most microeconomic analysts too hastily identify as the “feasible set.”13

For this paper, however, the chief importance of the investment analysis of Popkin et al. lies in the possibility of its consistent extension to political parties. In several passages strongly reminiscent of parts of Burnham’s work, Popkin et al. (1976) sharply criticize the Michigan group for assuming that most individuals can normally afford to contest outcomes that are products of a whole system whose scale is many times that of the average voter.

The SRC also assumed that the major barriers to participation were internal to the individual. In 1960 they stated “[t]he greater impact of restrictive electoral laws on Negroes is, in part at least, a function of the relatively low motivational levels among Negroes.” The increase of participation among black voters in the 1960’s is, of course, a clear example of a situation where political participation as well as political interest and involvement, rather than being fixed expressions of individual motivation, responded instead to an increase in investment opportunities and a legal decision by Congress to reduce the cost (or more aptly, to provide subsidies to aid blacks in paying the costs) of voting, (p. 790)

In the investor voter model, interest, involvement, and participation depend on the voter’s calculation of the individual stakes and costs involved in the election; included in this calculation are the voter’s issue concerns and his estimates of his opportunities for participation. As a result, much of the stigma of “apathy” is transferred from the voter to the electoral system, (pp. 789–90)

Instead of arguing that irresponsible voters lead to irresponsible parties, we argue that a fragmented system with weak parties leads to information problems for the individual voter which make the best possible decisionmaking strategies less than ideal. (p. 795)

But despite their inspired and often very amusing beginning, Popkin et al. do not pursue their inquiry to its logical conclusion. Their analysis points out the vast disproportion between what the individual voter-investor can afford and the range of potential information and action in principle available to him or her, and exposes the flimsiness of much of the “spatial modeling” now popular in political science, but there it halts. Remaining content with an investment theory of voting, Popkin et al. refrain from taking the obvious next step. They do not broach the question that their study clearly implies: if ordinary voters can’t afford to invest much in American political parties, then who can? And by virtue of their unique status, do not these “big ticket” investors automatically become the real masters of the political system?

Raising these questions, I think, transports one to the heart of the disastrous misunderstanding of the nature of political parties inscribed at the center of the Downsian approach to political parties (and its less formal ancestors). For what can be taken as the core proposition of the “investment theory of political parties” denies the validity of the Downsian treatment of parties as simple vote maximizers. Instead, the investment theory of parties holds that parties are more accurately analyzed as blocs of major investors who coalesce to advance candidates representing their interests.

As should momentarily become apparent, this proposition does not imply that such investor blocs pay no attention to voters. It does, however, mean that in situations where information is costly, abstention is possible, and entry into politics through either new parties or existing organizations is expensive and often dangerous (that is, in the real world in which actual political systems operate) political parties dominated by large investors try to assemble the votes they need by making very limited appeals to particular segments of the potential electorate. If it pays some other bloc of major investors to advertise and mobilize, these appeals can be vigorously contested, but—and this is the critical deduction which only an investment theory of parties can draw—on all issues affecting the vital interests that major investors have in common, no party competition will take place.14 Instead, all that will occur will be a proliferation of marginal appeals to voters—and if all major investors happen to share an interest in ignoring issues vital to the electorate, such as social welfare, hours of work, or collective bargaining, so much the worse for the electorate. Unless significant portions of it are prepared to try to become major investors in their own right, through a substantial expenditure of time and (limited) income, there is nothing any group of voters can do to offset this collective investor dominance.

While the “principle of noncompetition” over the vital interests of all major investors constitutes the most important predictive difference between the investment and the Downsian theory of political parties, it is scarcely the only one. A whole series of contrasts can be drawn between them.

1. Downsian theory privileges voters, who are said to exercise control over at least the broad shape of public policy. The investment theory holds that voters hardly count unless they become substantial investors. When the ranks of significant investors are limited to relatively small numbers of elite actors commanding disproportionate shares of politically mobilized resources, mass voting loses most of its significance for controlling public policy. Elections become contests between several oligarchic parties, whose major public policy proposals reflect the interests of large investors, and which minor investor-voters are virtually incapable of affecting, save in a negative sense of voting (or nonvoting) “no confidence.”

Because the claims made by the investment theory of parties can easily be misunderstood, the logic of the underlying argument is worth pursuing a bit further. Two points in particular require clarification: one relates to the potential role of voters according to the theory; the other, involving a rather complicated set of considerations growing out of the “rational choice” literature that Popkin et al. rely on, concerns the precise nature of some of the advantages large investors enjoy when they act politically.

In regard to voters, what the investment theory of parties does not say is every bit as important as what it does say. The theory does not deny the possibility that masses of voters might indeed become the major investors in an electoral system, or that, if they did so, conditions approximating a Downsian ideal of voter sovereignty might exist. As a later section briefly illustrates in discussing the expansion of unions during the New Deal, such conditions are conceptually very clear and empirically identifiable. To effectively control governments, ordinary voters require strong channels that directly facilitate mass deliberation and expression. That is, they must have available to them a resilient network of “secondary” organizations capable of spreading costs and concentrating small contributions from several individuals to act politically, as well as an open system of formally organized political parties. Both the parties and the secondary organizations need to be “independent,” i.e., themselves dominated by investor-voters (instead of, for example, donors of revokable outside funds). Entry barriers for both secondary organizations and political parties must be low, and the technology of political campaigning (e.g., cost of newspaper space, pamphlets, etc.) must be inexpensive in terms of the annual income of the average voter. Such conditions result in high information flows to the grass roots, engender lively debates, and create conditions that make political deliberation and action part of everyday life. What the theory claims is merely that in the absence of these conditions a party system that is competitive in the relevant Downsian sense cannot prevent a tiny minority of the population—major investors—from dominating the political system. The costs that the voters must bear to control policy will be literally beyond their means.

A proper analysis of the reasons why large investors are likely to dominate political systems, however, need not rest with the observation—however weighty—that, to paraphrase Hemingway, the rich are different because they have more money. By pursuing several themes in the literature on economic theories of politics that Popkin et al. draw upon, we see that a more subtle picture emerges of the special position that large investors occupy in a political system.

There is first of all a point whose potential importance was clearly recognized by Downs, though I do not believe that he ultimately accorded it sufficient weight (Downs, 1957a, Chap. 13). This is the simple fact that much of the public policy–relevant information that voters must pay heavily in time or money to acquire comes naturally to businesses (i.e., major investors) in the daily course of operations.

Closely related to this edge that large investors enjoy in acquiring information are the advantages they usually command in analyzing it. Computers engaged to service customers, for example, easily perform all sorts of politically relevant tasks. Perhaps a little less obviously, the business contacts that an international bank maintains also constitute a first-rate foreign-policy network. And the sometimes thin line separating normal advertising from lobbying virtually disappears for many producers of major weapons systems.

In many cases vast economies of scale further enhance the position of large investors. What is for a voter an absolutely prohibitive expense a large firm can afford on a regular basis. As long ago as the eighteenth century, for example, large investors routinely consulted their lawyers before making major moves. Two hundred years later, these consultations are likely to be done in a committee which includes not only lawyers but also public relations advisers, lobbyists, and political consultants.15 In sharp contrast to voters, for whom even jury duty can become an onerous burden, large firms also can easily afford to divert personnel to special projects.

Still other advantages armor what is sometimes cited as the Achilles’ heel of large investors—their very size and frequent diversity of interests (Bauer, Poole, and Dexter, 1972). Modern management structure developed precisely to afford top executives the capacities for detailed command and control that they need to adjudicate conflicts within the firm and to optimize complex sets of interests.16 Such organizational forms, along with the informal retinue of advisers large investors have always maintained, constitute uniquely institutionalized “memories” that dwarf the resources available to most voters.

Olson’s well-known study The Logic of Collective Action demonstrates that, in addition to all these advantages, major investors also derive subtle but decisive benefits from certain general characteristics of the process of interest intermediation and articulation (Olson, 1971).* Both because several of the most significant consequences of Olson’s argument have not as yet been integrated into empirical research and because his own applications of it to the business community were cursory and, in part, misleading, his analysis is worth retracing in some detail.

Its initial stages have been well summarized by Barry (1970, p. 24):

Olson’s argument is intended to apply wherever what is at stake is a “public good,” that is, a benefit which cannot be deliberately restricted to certain people, such as those who helped bring it into existence. A potential beneficiary’s calculation, when deciding whether to contribute to the provision of such a benefit, must take the form of seeing what the benefit would be to him and discounting it by the probability that his contribution would make the difference between the provision and the non-provision of the benefit.

In a world in which most collective goods can be safely assumed to be beyond the means of isolated individuals, Olson’s formal theory of collective action follows directly from his judgment that the probability that one actor’s decision to contribute will influence another’s drops steeply with increases in the size of the group which will enjoy the collective good (see Olson, 1971, p. 44):

In a small group in which a member gets such a large fraction of the total benefit that he would be better off if he paid the entire cost himself, rather than go without the good, there is some presumption that the collective good will be provided. In a group in which no one member got such a large benefit from the collective good that he had an interest in providing it even if he had to pay all of the cost, but in which the individual was still so important in terms of the whole group that his contribution or lack of contribution to the group objective had a noticeable effect on the costs or benefits of others in the group, the result is indeterminate. . . . By contrast, in a large group in which no single individual’s contribution makes a perceptible difference to the group as a whole, or the burden or benefit of any single member of the group, it is certain that a collective good will not be provided unless there is coercion or some outside inducements that will lead the members of the large group to act in their common interest.

Now, this argument is of course subject to all the limitations of its premises, which include two that have frequently become targets for criticism: that human behavior is an exercise in rational calculation and that it is exclusively self-interested.17 But it is doubtful if the criticism in this vein that Olson’s argument has received makes much difference. It is possible to agree that strictly neoclassical approaches to political economy invidiously neglect ideology. One can therefore endorse the search for a more comprehensive theory of action. It is equally possible to reject Olson’s implicit assumption that action is always a cost rather than a good in itself, and allow that the process of collective action can become a uniquely rewarding experience in its own right. And anyone can recognize that the assumption that humans are exclusively self-seeking may sometimes be a potentially serious distortion of reality even in a capitalist society.

But unless one is prepared to make truly heroic counter-assumptions, Olson’s fundamental point is likely to stand. Expectations that large groups of people will voluntarily provide huge subsidies over long periods of time to projects that return no benefit to themselves (and may often be completely wasted) is unlikely to prove fruitful as an approach to most of human history—and particularly to the analysis of market societies. As rival accounts of collective action put forward by Olson’s critics inadvertently illustrate when they initially posit the origins of collective action in attempts to escape misery and deprivation, reason (or history) may be cunning, but it is rarely philanthropic: much, probably most, collective action undertaken is straightforwardly instrumental and animated by perfectly ordinary passions.18 Most of it, accordingly, should follow the basic logic of Olson’s model.

But while his general analysis identifies an important reason for expecting small groups of large investors to display capacities for self-organization far beyond the capability of ordinary citizens, Olson’s actual application of his model to the business community is perhaps the least satisfying section of his work.

In part this is almost certainly the consequence of an ambiguity in his original presentation that has a most important bearing on its implications for large investors. If Olson is correct, one would expect to find many instances in American history in which relatively small groups of major investors organized and bore most of the costs of political campaigns directed toward ends that greatly benefited themselves. Since in the United States most of what the state provides is formally provided for the benefit of the whole population, these investor groups would therefore supply collective “goods” to the rest of the country in the perhaps elongated technical sense that Olson employs the term.19 And, indeed, though many contemporary social scientists often are unable to distinguish accounts of small groups of major investors efficiently providing themselves with public goods from outlandish and improbable “conspiracy theories,”20 American history is replete with vivid examples of the fundamental asymmetry Olson’s account suggests between the markets for collective action enjoyed by the rich and poor, respectively. Three of the greatest investors in the United States, for example, virtually financed the later stages of the War of 1812 all by themselves (Brown, 1942, p. 126; Hammond, 1957, pp. 231–32). Much of the money required for the force that quelled Shays’s Rebellion came from a handful of very affluent (and very nervous) investors.21 The original promoters of what eventually became the Brookings Institutions were a bloc of investors frankly hoping to reduce their taxes by curbing federal spending (by promoting the establishment of what became the Budget Bureau), while another group of millionaires bore the lion’s share of the costs for the effort to repeal Prohibition with the no less bluntly declared aim of reducing their taxes through the taxation of liquor (which the poor would pay).22

Oddly, however, Olson discounts such cases as “empirically trivial” (1971, p. 48, no. 68). He does this because in addition to making his main argument (discussed earlier), which relates group size to the likelihood that individual action can decisively affect the provision of a collective good (for instance, by the influence of one’s example on others), he also develops another line of thought. In this second account he tries to derive his proposition that large groups will not provide themselves with collective goods (absent coercion or selective incentives) directly from an analysis of how an individual’s share of a collective good varies with group size.23

Now, this is an exceedingly dangerous way to make the case. For as Olson himself is well aware, the only calculation strictly relevant to deciding whether an individual will participate in collective action relates to the net advantage that accrues to that individual from that action. While there is no reason anyone who wishes to cannot relate this condition of the total gains to the group as a whole (by simply forming the appropriate ratios), additional formulations simply distract from this crucial point. And, as an examination of Olson’s mathematical presentation shows, his efforts on this score led him into an error that has no consequences for his basic argument but which obscures the vitally important case of major investors who provide themselves and the country as a whole with collective goods.24

Olson’s own discussion of the business community is very brief, and largely confined to underscoring the conclusion that industries in which only a small number of firms compete will find it easier to organize. Cursory and highly stylized, it makes no sustained effort to engage empirical material (1971, pp. 141–48).

Many of the most interesting implications of his findings are not discussed at all. For example, if one accepts Olson’s arguments about the difficulties of achieving coordination in decentralized industries, then large merger waves, such as the United States experienced in the 1890s, 1920s, and more recent past, acquire potential political significance. Mergers, in effect, are a prime method by which actual businesses solve their collective action problems. Also, if Olson is correct, then the usual neoclassical dismissal of the importance of “aggregate” (in contrast to particular “industry”) concentration is probably mistaken, for it is clear that the scope of rivalry among a few giant firms which can coordinate and trade off operations in many industries at once will be vastly different from highly atomized and decentralized competition.25

The most significant omissions in Olson’s discussion of collective action within the business community, however, concern his neglect of the financial system and the potential role of coercion (even) within market systems. The former is important because the strategic position that leading financiers enjoy in many economies may at least partially solve free-rider problems among businessmen. Of course, the leverage banks can exert over other enterprises varies with many factors, including the secular trend of economic growth, the business cycle, and, obviously, the development of credit markets.26 No less clearly, the interests being served in such cases may not be those of “business as a whole” or some similarly exalted abstraction, but primarily those of the banks themselves. But it is probably no accident that empirical studies of really powerful cross-sectoral business organizations like the Business Council or the Committee for Economic Development (CED)—neither of which Olson mentions—reveal the omnipresence of big banks.27 And a long search I undertook of private records yielded direct evidence of pressure banks exerted on reluctant industrialists to enroll in the CED.28

Olson’s analysis should also stimulate a re-evaluation of the role coercion plays among large investors. Both Olson and his critics dwell overmuch on the “voluntary” character of social interactions. When he discusses individual cases, Olson customarily breaks off the discussion after he reaches his conclusion that, while huge gains accrue to groups which succeed in organizing themselves, absent coercion or selective incentives this is quite unlikely.29 By contrast, many of his critics, concerned either to reestablish the rationality of large group organizing efforts, or, more rarely, bothered that reality seems to provide more examples of successful collective action by large groups than theory predicts, often reply by tracing out arabesques of increasingly farfetched reasoning which might lead a large group to come together voluntarily in its own interest. But of course, the real alternatives facing a group with free-rider problems frequently include options more lively than dialogue among the members to build up a perhaps irrational mutual trust (Offe and Wiesenthal, 1980), encouraging the probably mistaken realization that none can hope to advance independently of the others (Roemer, 1978), or even locally based federation (which, since it associates small groups, fits Olson’s model as a part to collective action.) Specifically, it often is the case that the real “logic of collective action” for a large group with a vital interest at stake is the swift application (by some—perhaps self-appointed—subgroups) of coercion to erring members of the larger group.

Of course Olson, and his readers, are all perfectly well aware that coercion, force, violence, terror, and such practices are possibilities for social groups. The point, however, is that only in his discussion of labor unions does Olson energetically pursue the strategic trail in this direction (1971, pp. 66 ff.). Yet there is no reason to single out unions (or managements confronting unions). In general, any group of rational actors seeking to organize a large group will experience the same incentives—including major investors in the business community organizing various sorts of political coalitions.

American history is replete with examples of business groups and individual firms retaining vast arrays of military and paramilitary forces for long periods of time. In the nineteenth century many railroads kept private armies. The Pennsylvania Coal and Iron police ran their own Obrigkeitsstaat for decades. General Motors maintained the Black Legion; Ford sported a veritable Freikorps recruited by the notorious Harry Bennett; and any number of detective agencies, goon squads, “special consultants,” and wiretappers have also been active.30 That most of these—though clearly not all, for railroads often fought pitched battles with competitors—are usually said to have been directed at labor makes little difference. While this claim does underline the quasi-military character of many of the most important cases of collective action in American life, there is little reason to believe that it represents the whole truth. Force on such a scale potentially menaces competitors, buyers, and suppliers almost as much as it does workers.31

It is true that market forces place definite limits on the scope for coercion within the business community. But as the earlier reference to financial pressure on businesses should suggest, even an economy that might be reasonably competitive in the long run contains all sorts of imperfections and uncertainties that leave plenty of scope for direct pressure. Accordingly, it ought to surprise no one if, especially in times of extreme emergency, as, for example, during a war or strike wave, many businessmen turn rapidly to structures that contain strong elements of coercion—either by (some part of) themselves, emergency provisions in a liberal constitution, or, in truly dire emergencies, a Führer. And in less straitened circumstances political coalitions should be scrutinized carefully for elements of coercion as well as voluntary accord even within dominant groups.

2. Inside political parties, Downsian theory focuses all the attention on professional politicians. Investment theory takes care never to confuse investors/employers with politicians/employees.

The investment theory of politics does not deny that candidates and professional politicians have a great stake in their success, or indeed that they might have a greater interest than their major backers in winning at almost any price. But investment theories maintain that political organizations are (sometimes very complex) investments; that, while they need small amounts of aid and commitment from many people, most of their major endorsements, money, and media attention typically come as direct or indirect results of their ability to attract heavyweight investors. As a consequence not even former presidents with enormous personal popularity like Theodore Roosevelt could run insurgent campaigns without support from investors like U.S. Steel or investment banker George Perkins.32 In addition, for all the attention Downsian theorists focus on offices as the primary lure for candidates and parties, the investment theory of parties expects that a fairly clear distinction exists between routine lower-level appointments, with limited discretion and established formal and informal role expectations, and top policymaking slots. These latter, the investment theory of parties anticipates, are often reserved for representative major investors or their immediate designates (Ferguson, 1986).

3. Downsian theory expects parties to move near the voters on important policy dimensions and, indeed, often even “leapfrog” rivals in their haste to find the median voter. The investment theory expects very modest moves toward the public on all issues affecting major investors, rocklike stability toward the vital interests of these investors, and many efforts to adjust the public to the parties’ views rather than vice versa.33

The Vanderlip-McAdoo-Hilles deliberations regarding the Federal Reserve System discussed earlier, or the many other examples American history offers of major party candidates who flatly refused to take immensely popular steps opposed by almost all major investors (such as abandoning a balanced budget to extend relief during major economic downturns)34 should embarrass Downsian theory but scarcely the investment theory of parties. On the contrary, if, for example, George McClellan in 1864, Horatio Seymour in 1868, Rutherford Hayes in the late 1870s, Grover Cleveland in the 1880s and 1890s, Alton Parker in 1904, William Howard Taft in 1912, all major party candidates in 1924 and 1932, Alfred Landon in 1936, Barry Goldwater in 1964, Jimmy Carter in 1980, and any number of other presidential candidates all expressly repudiated major factions of their party immediately ahead of closely contested elections, the investment theory just looks for the investors who insisted on having their way.35

4. Downsian theory anticipates competition between the parties on most issues; the investment theory of parties, on the contrary, expects that whole areas of public policy will not be contested at all, while on others the parties will differ like Ford and GM before the Japanese arrived.

Downs hedged his original analysis of political dynamics with all sorts of qualifications about single-peaked preferences, etc. Subsequent commentators added a variety of other caveats, of which those concerning the number and types of issues contested were probably the most important (Stokes, 1966). But neither Downs nor most of his critics ever indicated they believed that most major parties in advanced industrial societies would actually fail to compete on many important issues in which the interests of many citizens were fairly clearly defined, or could, through political campaigning, readily be defined. Nor, so far as I can discover, did anyone ever do more than glance at systematic pressures put on parties not to make issues out of certain questions of public policy or entertain the possibility that both major parties (in a two-party system) would regularly do precisely this. To the investment theory of political parties, of course, nothing is more natural. If all major investors oppose discussing a particular issue, then neither party is likely to pick the issue up—no matter how many little investors or noninvestors might benefit—not because of any active collusion between parties but because no effective constituency exists to force the issue onto the public agenda.

Also, the investment theory of parties would scarcely be surprised to discover that the major parties in party systems marked by great economic inequality or sharp swings in national income often confine almost all competition to noneconomic issues less threatening to elite investors. This does not, it should be observed, imply that political parties generate these noneconomic cleavages. It says merely that, if an emphasis on noneconomic issues protects major investors in all parties, then emphases on ethnic, racial, or cultural values will proliferate relative to economic appeals. And, the investment theory adds, studies of voting behavior that cite ethnocultural voting patterns congruent with such partisan appeals as evidence against older economic interpretations of U.S. political behavior are invalid in principle.36 Without an analysis of party leadership and public policy output, the voting patterns cannot be interpreted.

The contrast between the Downsian and the investment theory of political parties could go on indefinitely and with endless refinement. But the implications for this paper on critical realignments should now be clear: for all its merit and intellectual interest, Downs’s An Economic Theory of Democracy misspecifies the basic market in which political parties operate. Not voters but investors constitute their fundamental constituency.

Once this central point is clarified, a revised approach to the definition of party systems and critical realignments becomes immediately available. If, according to the investment theory of parties, political parties are constituted by “core” blocs of major investors interested in securing a small set of specific outcomes, then “party systems” are the systems of action organized by these major investment blocs. Depending on the relative strength of the contending blocs, several different types of “party systems” can be distinguished. In rare cases (such as the Era of Good Feeling after the War of 1812) virtually all major investors may be organized into one massive, utterly “hegemonic” bloc, so that national party competition literally ceases to exist. Similarly, even where competition between rival blocs has brought into being another party, one investment bloc may still strongly dominate the other. Where one bloc succeeds in controlling most outcomes and reducing its opponents to variations on its themes (as, for example, the Democrats did to the Republicans for years after the New Deal), it also makes sense to continue to refer to the dominant bloc as “hegemonic,” though this case is clearly very different from instances where no organized opposition exists at all. Where no one party exercises hegemony, rival blocs will simply be “competitive.” Since the identity of parties—and thus of a party system—depends on the blocs that make them up and not on whether some party happens to win or lose, it is perfectly reasonable to speak of a party system as decaying over time from hegemony to competitive status, or even as having a life cycle, provided that is understood as referring, say, to changes in the relative power of various elements composing a once-dominant bloc or to minor shifts between the parties. And, obviously, party systems also pass away. In theory this could happen by slow change of identity in an industrial equivalent of Key’s “secular realignment” (which could lead to tedious definitional arguments).37 In actual fact, however, for reasons adumbrated in the next section, all but the first American party system ended catastrophically in brief critical realignments that ushered in new and notably different party systems.

Also, in the spirit of the earlier analysis of the crucial role size differentials among coalition partners play in political coalitions, one would expect that a bloc that is hegemonic for any length of time might be—in Gramsci’s famous phrase—“crowned” by a particularly outsized and active unitary (or near unitary) actor. Because of its disproportionate size relative to the rest of the coalition, and its relatively enormous stake in the system as a whole, this “hegemon” often becomes the final source of the emergency subsidies any political coalition sometimes requires. Its prominence within the system may also afford it some scope for coercion, which also will help keep the bloc together.

III. TESTING THE INVESTMENT THEORY OF POLITICAL PARTIES: METHODOLOGICAL AND OPERATIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

Many discussions of the methodological issues involved in testing highly abstract social science theories strongly resemble Sunday morning radio broadcasts. Inspired more by a desire to protect a license than by any audience demand for the information, they fill the air with a hodgepodge of pious cant and sententious banality that only rarely connects to real problems. At the risk of further blackening the good name of empirical social science, however, some discussion of methodology is indispensable in this paper, for it is perfectly obvious that any number of questions are likely to arise naturally in the course of operationalizing the theory just sketched. If, for example, blocs of major investors constitute party systems, then how should one distinguish “major” from “minor” investors? For that matter, just exactly who or what constitutes an “investor” in the relevant sense?

Assuming that these notions can be satisfactorily elucidated, what counts as evidence for claims that major investors “support” particular candidates, issues, and parties? Still more importantly, let us agree for the sake of argument that the evidence shows that powerful blocs of investors have actually massed behind different parties at different times. How can the existence and stability of such coalitions over the course of a whole party system be demonstrated? Without evidence on these points the investment theory of parties is vulnerable to the same sort of embarrassments that electoral theories endured when tests failed to reveal the stable voting blocs persisting through the “party systems” that they were supposed to define. And finally, of course, how does one recognize and deal with situations which the investment theory itself acknowledges, when major investors do not dominate a party system and something like effective mass democracy actually occurs?

Not all of these questions are equally urgent. The first, for example, sounds far more profound than it really is, and can be dealt with summarily. Essentially the investment theory of political parties postulates that a strong relationship exists between the extremes (or “tails”) of two different distributions; the distribution of investors in political action and the distribution of investors in the circumambient economy. In testing the theory nothing important depends on the exact values of the cutoff points used to indicate “large” investors in each distribution—the top 5 percent, 10 percent, 12 percent, or whatever.38 So long as both distributions actually are skewed, large investors can be meaningfully distinguished, though, of course, in any case study specific characteristics of a particular skewed distribution are almost certain to become important facts.39

The closely related question of who or what counts as an “investor” also sounds more penetrating than it really is. As the proliferating literature on managers, owners, and corporate control suggests, identifying the locus of working control in certain organizations can be difficult and time-consuming (Herman, 1981; Burch, 1972; Zeitlin and Norwich, 1979). In some cases, accordingly, unravelling the identity of the relevant “investors” may be tedious and complicated. But there is little point to pursuing such considerations here. The significant operational point is plain: depending on the historical period, the relevant investing units could be individuals, partnerships, firms, foundations, financial groups, or, in cases where the fortunes of particular families or individuals are centrally invested and controlled, a “fortune.” In rare cases, a state agency or bureaucracy might also be considered a “major investor,” as could the exceptional case mentioned earlier, of an autonomously acting division of a large firm going into business on its own. Beyond the jejune injunction that empirical inquiries into these questions need to be guided by the best available literature and techniques of the parts of business history concerned with them, nothing general can be said. What is at stake are complicated facts whose meaning is bound tightly to context and particular cases.

While puzzles about the identity of investors are therefore problems less for the investment theory of political parties than for other branches of the social sciences such as business history, the same cannot be said about the methodological problems involved in inquiries into which parties or policies a firm or a group of investors supports at particular moments. In the absence of a clear justification for these sorts of claims the investment theory of parties cannot hope to flourish.

Records of campaign contributions by major investors, of course, can provide important clues about who supports what. But while such evidence often yields important insights, it is most commonly marked by distinct limitations. The biggest problem is with the fragmentary character of the data for nearly all periods of American history. Analysts of campaign contributions are nearly unanimous in pointing to its inadequacies (Overacker, 1932; Thayer, 1973). Large numbers of pecuniary contributions were understated or never recorded at all. Cash paid in the form of excessive consultant, lawyer, and other third-party fees is rarely noticed and in-kind contributions almost never listed. “Loans” which are never repaid or are granted on preferential terms rarely attract notice. Neither do “gifts” to “friends.”

Not surprisingly, almost every seriously pursued investigation of campaign contributions, from the Hearst-inspired attacks on Theodore Roosevelt and E. H. Harriman to the recent inquiries into corporate bribery conducted under the auspices of the Securities and Exchange Commission, has unearthed unreported contributions of astronomical magnitude. And there is reason to think the omissions have often followed systematic patterns. In an ingenious statistical comparison, Pittman has demonstrated that a series of striking and predictable differences exist between the original “public” campaign contribution lists of the 1972 Nixon campaign and the secretly maintained files that later court cases brought to light (Pittman, 1977). A good rule of thumb, accordingly, is to treat published campaign contributions (even after the recent changes in the law) as the tip of an iceberg, and be wary of any analysis that relies only on them.

This is less devastating to political analysis than it appears. Sometimes a fuller pattern of corporate contributions can be retrieved by careful archival work. Other cases can sometimes be clarified by thorough analysis of apparent patterns in corporate contributions: looking either at a sample of core actors that one has defined on other grounds as possessing a strong common interest, or checking carefully among the attorneys for major actors.

The beginning of real wisdom in these matters, however, occurs when one reflects that direct cash contributions are probably not the most important way in which truly top business figures (“major investors”) act politically. Both during elections and between election campaigns, their more broadly defined “organizational” intervention is probably more critical. As the earlier discussion of free-riders suggested, such elite figures function powerfully as sources of contacts, as fundraisers (rather than mere contributors) and, especially, as sources of legitimation for candidates and positions. In particular, as I have sought to document elsewhere, the interaction of high business figures and the press has frequently been pivotal for American politics (Ferguson, n.d.). Merely for J. P. Morgan or David Rockefeller to make known his choice for president or his policy views to newsmen is to instantly confer substantial newsworthy reality to them—and to contribute an in-kind service whose value dwarfs most cash contributions.

This “organizational” influence is less conveniently available than national campaign committee records, but it is not impossible to obtain, and it has the virtue of being far more reliable than published single-figure dollar totals. While of course anyone can reel off a long list of their potential limitations,40 private archival sources provide unparalleled access to this sort of evidence. If Thomas Lamont of J. P. Morgan & Co. in 1932 was writing intimate small-circulation letters to other New York bankers in support of incumbent President Herbert Hoover, and one can obtain these letters, that should settle the question of Lamont’s choice for president, no matter how often American historians have asserted he was Franklin D. Roosevelt’s friend (Ferguson, 1986, n.d.). Similarly, if the chairman of the General Electric Company was actively aiding New York Senator Robert Wagner in preparing the National Labor Relations Act, it is a fair conclusion that he favored it over alternatives (Ferguson, 1984, n.d.).

But published sources contain much more evidence than most scholars realize. Newspapers print ads with endorsements; obituaries often disclose a remarkable political history; and collating newspaper accounts of campaigns and campaign press releases often is enormously illuminating. Even biographies, institutional histories, and magazine profiles of businessmen sometimes contain important facts, while for figures active in the present and recent past, oral interviews can be hazarded.41 In most cases, if one cannot come up with the full roster of a candidate’s supporters, still one can generally identify a “core.” When this is examined for internal consistency and structure (perhaps in the light of preexisting theory), very striking patterns often emerge.

Political appointments can also furnish important evidence. As several recent studies have shown, a systematic examination of these can be remarkably revealing.42

Complicating questions of evidence are instances in which industries or firms appear to be operating in both parties. These are often cited by analysts who wish to deny that businesses promote definite public policies or that they wield their influence to obtain these policies, so the logic of the situation is important to understand.

The first step in a realistic analysis is to focus sharply on the ways in which issues figure in political campaigns. Party politics in America most commonly displays only loose relations to issues. As a consequence, in practice, issue politics in America at a national level always implies a focus on a particular candidate. Right here, a fair number of cases of business bipartisanship become immediately intelligible.

In the nomination stage of election campaigns it is only common sense for many firms to float a candidate (or more) in each party. The chances of getting a winner are thus much enhanced. Similarly, different levels of government and different regions of the country may make useful mixed strategies of candidate support by one firm. Other forms of bipartisanship are no less intelligible but depend on different reasoning. The guiding principle is that selection of political parties is merely a special case of rational portfolio choice under uncertainty: one holds politicians more or less like stocks.

A firm cannot predict exactly who will win or know for certain exactly what policies will be implemented if a candidate or party is victorious. But, as the Vanderlip-Stillman exchange suggests, it has some useful knowledge of the candidates and parties. So it has to estimate its chances of advancing a particular policy and discount for the possibility it will lose. Some industries or firms find themselves wanting policies that the other party clearly could never accept. Having nothing to gain from bipartisan strategies, these industries (or firms) become the “core” of one party, as, for example, textiles, steel, and shoes were in the Republican Party after the New Deal because of labor policy, and chemicals because of trade (Ferguson, 1984, n.d.). Other industries or firms, differently situated, can try out both parties. But this is the crucial point: rarely equally. For everyone to find it in his or her interest to hold identical portfolios of parties is as outlandish as the case of everyone’s attempts to buy and hold one stock, and for exactly the same reasons.

The chance of one candidate’s simultaneously satisfying high- and low-tariff advocates, labor-intensive and high technology firms, or exporters and importers is zero. And, especially in large firms which have resources big enough to affect the outcome, some clarity about this can be shown to obtain.43

The underlying dependence of business bipartisanship on an incomplete articulation of issues is pointed up by critical elections like the one of 1936. That election had been preceded by several in which issues had not always been clearly defined. It was thus easy, and common, for many (not all) investors with a party identification (especially attorneys, whose position in the party depended on party regularity) to swallow their disappointment at one or another candidate they disapproved of and remain to support him in the general election. But the 1936 election showed that, as policy divergence between parties grew, the bipartisanship of firms disintegrated in a perfectly obvious and—it can be shown—predictable fashion (Ferguson, 1984, n.d.).

Once intensive research has produced data linking as many major investors as possible to particular candidates, issues, and parties, the focus of the inquiry turns naturally from the facts of “support” (or the “support network”) to attempts to explain it. Now, the general thrust of the investment theory of parties on this question is straightforward: The political investments of major investors are governed by the same criteria that all their other investments are.44 For this essay, where there is not space to consider the many rather obvious ways one can modify or qualify this postulate, this should be taken to normally imply an attempt to maximize wealth (relative, perhaps, to some level of risk) in whatever form existing institutional arrangements permit this to be augmented: revenues in a business, salaries in a bureaucracy, or whatever.45 Accordingly, the investment theory of political parties predicts that the political investments of major investors can usually be related directly (if commonly more subtly than most “economic” theories of politics suggest) to their particular positions in the political economy.

Now, it should be clear that a general methodological analysis cannot hope to specify precisely how one defines the politically relevant aspects of these “particular positions in the political economy.” Such analyses emerge only from a detailed analysis of specific historical periods.

Nevertheless, it is quite possible to identify a general method for handling most of the data that one usually encounters. Essentially a graphical analysis of political coalitions in terms of industrial (and, where necessary, agricultural) structures, this procedure has the happy property of providing a means for displaying the coherence of coalitions during a single election. In addition, a simple extension of the technique to several elections provides the answer to another of the questions raised earlier, viz., how it is possible to demonstrate the coherence and stability of entire party systems (as well as, of course, their eventual breakdown).

An application to industrial structures of spatial analysis techniques used for many years in many parts of the social sciences, this technique is perhaps most conveniently explained by outlining the steps one might take once one had finished acquiring information on the empirical pattern of “support,” as discussed previously.

The procedure is straightforward. First one identifies what appears to be the major outcomes or issues involved in an election. As I have elsewhere observed (Ferguson, 1986)—and it should be obvious anyway—the identification of the relevant outcomes requires great care. The judgments involved (which may, and indeed commonly should, be justified as far as possible by reference to quantitative evidence) frequently rely on intelligent aggregation of cases, measures, and other particulars. They are therefore normally complex and sometimes delicate, making it very easy to overlook major policies that the analyst happens not to care about, that involve recondite or obscure facts (such as monetary policy), or which require reference to so-called nondecisions or subtle policy moves disguised as administrative measures.46

Once a plausible list of outcomes that brought the coalition together has been identified, the second and most important step becomes obvious. When compared with the objective facts of the actual economic structure, the issues define a multidimensional space. By simply plotting each major investor’s position in this space, a “spatial” profile emerges that displays relationships between investors’ policy positions and their economic situation. One can then see—sometimes at a glance—whether a logic exists within the business structure to a candidate’s support “network” during an election or to a whole party system.

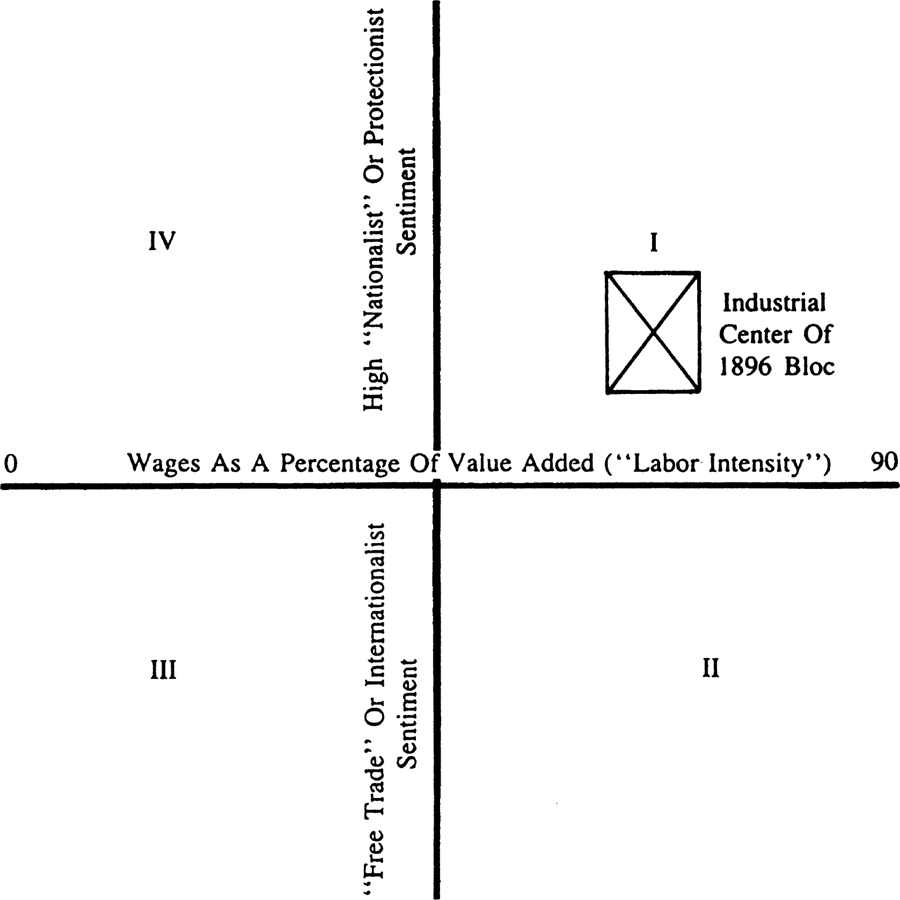

A concrete example (adapted and greatly simplified from an actual model conceptualized in an earlier essay) that illustrates the use of these techniques to analyze a party system as a whole may be helpful. An inquiry into the sources of the monolithic policy cohesion exhibited by the Republican Party during most of the “System of 1896” suggested that a two-dimensional scattergraph of the contemporaneous American business structure might be quite revealing.47 For present purposes let us regard the first dimension as referring to the “labor intensity” of an individual firm’s production process. The second can then be described as a nationalist-internationalist dimension in which free-trading businesses opposed tariff-seeking protectionists.48 When the nonfinancial sectors of the business community are scattergraphed along those dimensions and the financial community is then added in,49 it is impossible to miss seeing the gigantic—indeed hegemonic—antilabor, intensely nationalist bloc of the system of ’96 centered in quadrant 1 of figure 1.1