From ‘Normalcy’ to New Deal: Industrial Structure, Party Competition, and American Public Policy in the Great Depression

IN OCTOBER 1929, only weeks after Yale economist (and investment trust director) Irving Fisher publicly announced that “stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau,” and virtually on the day that J. P. Morgan & Co. partner Thomas W. Lamont reassured President Herbert Hoover that “there is nothing in the present situation to suggest that the normal economic forces . . . are not still operative and adequate,” the New York Stock Exchange crashed.1 Over the next few months the market continued dropping and a general economic decline took hold.2 As sales plummeted, industry after industry laid off workers and cut wages. Farm and commodity prices tumbled, outpacing price declines in other parts of the economy. A tidal wave of bankruptcies engulfed businessmen, farmers, and a middle class that had only recently awakened to the joys of installment buying.3

While the major media, leading politicians, and important businessmen resonantly reaffirmed capitalism’s inherently self-correcting tendency, havoc spread around the world. By 1932, the situation had become desperate. Many currencies were floating and international finance had virtually collapsed. In part because of the catastrophic fall in income and in part from mushrooming tendencies toward consciously pursued policies of trade restriction, world trade had shrunk to a fraction of its previous level. In many countries one-fifth or more of the workforce was idle. Homeless, often starving, people camped out in parks and fields, while only the virtual collapse of real-estate markets in many districts checked a mammoth liquidation of homes and farms by banks and insurance companies.4 As a new spiritus diaboli, Fascism, joined the old specter, Communism, to haunt Europe and the world, conflicts multiplied both within and between nation states.

In this desperate situation, with regimes changing and governments falling, a miracle seemed to occur in the United States, the country that, among all the major powers in the capitalist world economy, had perhaps been hit hardest. Taking office at the moment of the greatest financial collapse of the nation’s history, President Franklin D. Roosevelt initiated a dazzling burst of government actions designed to square the circle that was baffling governments elsewhere: how to enact major social reforms while preserving both democracy and capitalism. In a hundred days his administration implemented a series of emergency relief bills for the unemployed; an Agricultural Adjustment Act for farmers; a bill (the Glass-Steagall Act, also sometimes referred to as the Banking Act of 1933) to “reform” the banking structure; a Securities Act to reform the stock exchange; and the National Industrial Recovery Act, which in effect legalized cartels in American industry.5 Roosevelt suspended the convertibility of the dollar into gold, abandoned the gold standard, and enacted legislation to promote American exports. He also presided over a noisy public investigation of the most famous banking house in the world: J. P. Morgan & Co.

For a while this “first New Deal” package of policies brought some relief, but sustained recovery failed to arrive and class conflict intensified. Two years later, Roosevelt scored an even more dramatic series of triumphs that consolidated his position as the guardian of all the millions, both people and fortunes. A second period of whirlwind legislative activity in 1935 produced the most important social legislation in American history—the Social Security and Wagner acts—as well as measures to break up public-utility holding companies and to fix the price of oil. The president also turned dramatically away from his earlier economic nationalism. He entered into agreements with Britain and France informally to stabilize the dollar against their currencies and began vigorously to implement earlier legislation that empowered Secretary of State Cordell Hull to negotiate a series of treaties reducing U.S. tariff rates.6

After winning one of the most bitterly contested elections in American history by a landslide (and giving the coup de grace to the old Republican-dominated System of 1896), Roosevelt consolidated the position of the Democrats as the new majority party of the United States. He passed additional social welfare legislation and pressured the Supreme Court to accept his reforms. Faced with another steep downturn in 1937, the Roosevelt team confirmed its new economic course. Rejecting proposals to revive the National Recovery Administration (NRA) and again devalue the dollar, it adopted an experimental program of conscious “pump priming,” which used government spending to prop up the economy in a way that foreshadowed the Keynesian policies of demand management widely adopted by Western economies after 1945. This was the first time this had ever been attempted—unless one accepts the Swedish example, which was virtually contemporaneous.7

Roosevelt and his successive New Deals have exercised a magnetic attraction on subsequent political analysts. Reams of commentary have sought to elucidate what the New Deal was and why it evolved as it did. But while the debate has raged for over forty years, little consensus exists about how best to explain what happened.

Many analysts, including most of those whose major works shaped the American social sciences and historiography of the last generation, have always been convinced that the decisive factor in the shaping of the New Deal was Franklin D. Roosevelt himself.8 They hail his sagacity in fashioning his epoch-making domestic reforms. They honor his statecraft in leading the United States away from isolationism and toward Atlantic alliance. And they celebrate the charisma he displayed in recruiting millions of previously marginal workers, blacks, and intellectuals into his great crusade to limit permanently the power of business in American life.

Several rival accounts now compete with this interpretation. As some radical historians pose the problem, only Roosevelt and a handful of advisers were farsighted enough to grasp what was required to save capitalism from itself.9 Accordingly, Roosevelt engineered sweeping attacks on big business for the sake of big business’s own long-run best interest. (A variation on this theme credits the administration’s aspirations toward reform but points to the structural constraints capitalism imposes on any government as the explanation for the New Deal’s conservative outcome.)

Another recent point of view explains the New Deal by pointing to the consolidation and expansion of bureaucratic institutions. It deemphasizes Roosevelt as a personality, along with the period’s exciting mass politics. Instead, historians like Ellis Hawley single out as the hallmarks of the New Deal the role of professionally certified experts and the advance of organization and hierarchical control.10

Some of these arguments occasionally come close to the final current of contemporary New Deal interpretation. This focuses sharply on concrete interactions between polity and economy (rather than bureaucracy per se) in defining the outcome of the New Deal. Notable here are the (mostly German) theorists of “organized capitalism,” several different versions of Marxist analysis, right-wing libertarian analysts who treat the New Deal as an attempt by big business to institutionalize the corporate state, and Gabriel Kolko’s theory of “political capitalism.”11

These newer approaches provide telling criticisms of traditional analyses of the New Deal. At the same time, however, they often create fresh difficulties. “Organized capitalism,” “political capitalism,” or the libertarian “corporate state” analyses, for example, are illuminating with respect to the universal price-fixing schemes of the NRA. But the half-life of the NRA was short even by the admittedly unstable standards of American politics. The historic turn toward free trade that was so spectacularly a part of the later New Deal is scarcely compatible with claims that the New Deal institutionalized the collective power of big business as a whole, and it is perhaps unsurprising that most of this literature hurries over foreign economic policy. Nor are more than token efforts usually made to explain in detail why the New Deal arrived in its classic post-1935 form only after moving through stages that often seemed to caricature the celebrated observation that history proceeds not along straight lines but in spirals. It was, after all, a period in which the future patron saint of American internationalism not only raised more tariffs than he lowered but also openly mocked exchange-rate stability and the gold standard, promoted cartelization, and endorsed inflation.12 Similarly, theorists who treat the New Deal chiefly as the bureaucratic design of credentialed administrators and professionals not only ignore the significance of this belated opening to international trade in the world economy, but they also do less than full justice to the dramatic business mobilization and epic class conflicts of the period.

Nor do any of these accounts provide a credible analysis of the Democratic Party of the era. Then, as now, the Democratic Party fits badly into the boxes provided by conventional political science. On the one hand, it is perfectly obvious that a tie to at least part of organized labor provides an important element of the party’s identity. But, on the other, it is equally manifest that no amount of cooptation accounts for the party’s continuing collateral affiliation with such prominent businessmen as, for example, Averell Harriman. Why, if the Democrats truly constituted a mass labor party, was the outcome of the New Deal not more congruent with the traditional labor party politics of Great Britain and Germany? And, if the Democrats were not a labor party, then what force inside it was powerful enough to contain the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) and simultaneously launch a sweeping attack on major industrial interests?13 These analyses also slip past the biggest puzzle that the New Deal poses. They offer few clues as to why some countries with militant labor movements and charismatic political leaders in the Depression needed a “New Order” instead of a New Deal to control their workforce.

Nor has theory, especially economic theory, figured significantly in most of these studies. The centrality of issues like the money supply, international finance, and macroeconomic policy has failed to come into focus. Important theoretical discussions (like debates over Federal Reserve policy during the period) echo only faintly, or not at all, in more general writing, while neoclassically inclined economists have thus far ignored all aspects of the New Deal that create difficulties for their particular theoretical viewpoint.14

In this chapter I contend that a clear view of the New Deal’s world historical uniqueness and significance comes only when one breaks with most of the commentaries of the last thirty years, goes back to primary sources, and attempts to analyze the New Deal as a whole in the light of explicit theories about industrial structure, party competition, and public policy. Then what stands out is the novel type of political coalition that Roosevelt built. At the center of this coalition, however, are not the workers, blacks, and poor who have preoccupied liberal commentators, but something else: a new “historical bloc” (in Gramsci’s phrase) of capital-intensive industries, investment banks, and internationally oriented commercial banks.

This bloc constitutes the basis of the New Deal’s great and, in world history, utterly unique achievement: its ability to accommodate millions of mobilized workers amidst world depression. Because capital-intensive firms use relatively less direct human labor (and that often professionalized and elaborately trained), they were less threatened by labor turbulence. They had the space and the resources to envelop, rather than confront, their workforce. In addition, with the momentous exception of the chemical industry, these capital-intensive firms were world as well as domestic leaders in their industries. Consequently, they stood to gain from global free trade. They could, and did, ally with important international financiers, whose own miniscule workforce presented few sources of tension and who had for over a decade supported a more broadly international foreign policy and the lowering of traditionally high American tariffs.

In the first part of this chapter I develop a formal theory of industrial partisan preference as the joint consequence of class conflict and the differential impact of the world economy on particular businesses. I also relate the theory to the V. O. Key–Walter Dean Burnham-(Michigan) Survey Research Center (SRC) discussions of party systems and critical realignments, arguing that transformations of elite industrial coalitions lie behind the phenomena voting analysts have for so long tried to analyze. This section also presents an explicit account of the dynamics of the transition from the System of 1896 to the New Deal.

In the second part I outline the major elements of the coalition that triumphantly came together during and after Roosevelt’s Second New Deal—the coalition that, in its successive mutations, dominated American politics until Jimmy Carter. Employing the first part’s theoretical framework, I sketch the systematic, patterned disintegration of the System of ’96 and the simultaneous emergence of another New Deal bloc, whose interests and ideology shaped what can conveniently be termed “multinational liberalism.”

1. PARTY COMPETITION AND INDUSTRIAL STRUCTURE

My principle argument divides conveniently into two subordinate parts. The first, what might be called the “static theory of industrial partisan preference,” builds on recent work by James Kurth, Peter Gourevitch, and Douglas Hibbs, among others.15 Introducing first the “labor constraint” and then issues in international political economy, I present an abstract, basic model of partisan choice by particular industries and firms exhibiting differential sensitivity to class conflict and foreign economic policy issues. Following two earlier articles, I show how the policy—and hence, partisan—choices of these firms define the durable party systems extensively discussed by analysts of mass voting behavior.16 I also demonstrate a method for the measurement and graphical analysis of these political coalitions.

The second spells out the dynamic implications of the static model. It investigates how major changes in the level of national income (i.e., long booms or major depressions) affect party systems and political coalitions. Major spurts of economic growth and protracted economic decline, runs the argument, destabilize political coalitions in quite specific, predictable ways. By tracing how steadily rising or falling income affects a given industrial structure, one glimpses the logic by which earlier coalitions, built around increasingly obsolescent combinations of trade and labor, decay, while new coalitions arise. One also comes to understand how booms and depressions characteristically generate brief but intense conflicts over certain issues, notably money and finance, which can enormously complicate transitions from one party system to another. By examining in detail how such forces affect the basic model of the System of ’96’s partisan cleavages, I provide an account of the dynamics of the New Deal—one that explains not only the long-run evolution of the System of ’96 into the New Deal but also the complex sequence of apparently contradictory policy changes through which the New Deal evolved before it assumed its classic Second New Deal form.

The Static Theory

The basic argument connecting industrial structure to political parties and public policy is uncomplicated. It follows from two widely acknowledged facts. The first can be summarized as the ubiquitous and enduring presence of social class conflicts within the electoral systems of virtually all countries permitting at least moderately free elections and modestly competitive political parties. As one careful quantitative study of the cross-national evidence recently observed, “Although the importance of socioeconomic status as a basis of electoral cleavage varies substantially across party systems, the mass constituencies of political parties in most advanced industrial societies are distinguished to a significant extent by class, income, and related socioeconomic characteristics.”17 The second merely highlights the policy consequences of the first: the actual influence of labor and the working classes on public policy varies substantially over time, both within and across countries.18

Thus, as a long and distinguished tradition of social theory emphasizes and evidence from some, but not all, countries suggests, it might well be the case that labor’s ability to dominate a political party—and, when that party is in power, government policy—is such as to threaten gravely the institution of private business itself or at least to strike deeply at the prerogatives and earnings of all employers. In these instances, other things being equal, the whole business community will rush into opposition and establish one or more political parties of its own.

But if labor’s social position is weak, if it cannot organize its own political party, what happens? Most social scientists and historians recognize that in such circumstances labor enters into a coalition, appearing as one among several interest groups within a party or government. Most do this implicitly, in the course of narratives or analyses that record the historical facts. A few substantially improve upon this practice and try deliberately to spell out what the artless language of modern game theory often refers to as the “payoffs” to each partner in particular political coalitions in various countries at different times.19

Viewed in the light of industrial structure, however, a more general logic to political coalitions involving labor becomes plain. For what is at stake in these coalitions is the exact “price” that businesses seeking to coalesce to advance their own ends must “pay” to obtain support from the workforce. If one could specify in detail which firms or industries could most easily afford this price, one would have developed a predictive model of party competition. Such a perspective might cast light on the strange character of the Democratic Party in the United States and, perhaps, some of the tamer social democratic parties in postwar Europe.

Such an assessment of abilities to “afford the price” is not beyond the reach of current interpretative capability. Two polar cases make the essential points transparent. Consider the hypothetical case of a business that employed absolutely no labor, one that relied entirely on robots. Such an enterprise would have an exceedingly remote interest in most of the issues historically disputed between business and labor.20 Other things being equal, it could quite easily afford to support what looked to the unaided and untheoretical eye like a “labor” party, or at least practice consistent bipartisanship. By contrast, industries that rely on masses of un- or semiskilled labor, for whom national labor issues are highly salient, would enjoy far less freedom of maneuver. Unlike the fully automated firm, they could not afford higher social insurance, could not pay higher wages, could not accept a union. Where the workforce was already organized, they could not resist the pressure to attempt to undermine it. And a legislated minimum wage would usually constitute a direct threat to them. In Europe, such firms would most likely bulwark a conservative party; in America, they would have no alternative but to become rockribbed Republicans.

Of course, some level of class conflict always exists beyond which all industries retreat to a single business party (a case more common in Europe than in the United States). But short of that point, different industries featuring differential sensitivities to what can be termed the “labor constraint” can seize the opportunity to govern through the votes of their laborers.

The rule of “minimal accounts of labor” obviously needs to be modified in many cases.21 But, as the allusion to robot-run factories suggests, in general a business that relies less on workers than it does on, for example, capital should properly be considered less “labor-sensitive” than one that does the reverse. Accordingly, industry statistics for variables like “wages as a percent of value added” provide rough quantitative estimates of an industry’s ability to afford a coalition with labor and make it quite easy to order industries and firms along this dimension.

The firms least likely to undertake such an effort (and thus most likely to support the “business party”) are, obviously, low-wage labor-intensive firms like those commonly found in the textile industry. Thereafter, using 1929 estimates from the Census of Manufacturers of wages as a percentage of value added, we can identify:

Then come two industries—commercial banking and investment banking—whose labor costs measured in this manner are almost irrelevant since their costs are overwhelmingly the costs of borrowed money (paid to depositors or whomever); and, finally, real estate (local only).22

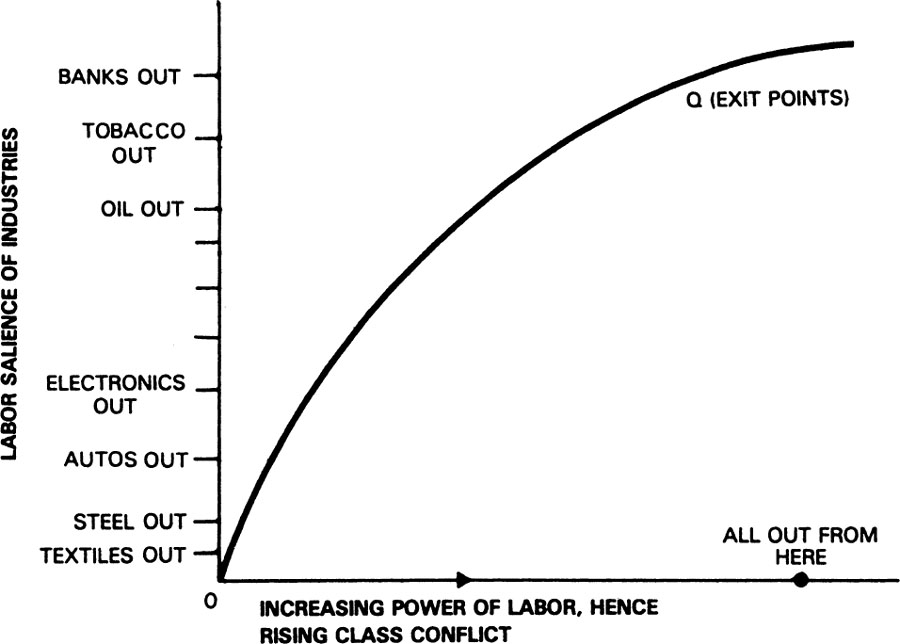

Combining an industry’s “labor sensitivity” with the known facts of class conflict yields a simple, comparative static model of industrial structure and party competition, which can summarized visually (see figure 2.1). On the horizontal axis runs a continuous variable representing a proxy (which can be as complex as the analyst desires) for the degree of class conflict, or its equivalent, the balance of power between labor and capital actually struck in terms of public policy over some stretch of time.23 On the vertical axis is an estimate of an industry’s sensitivity to the labor constraint (as derived from the above listing). In a simple model, where taxes or international issues do not induce complications, this establishes the value of a probability function Q, the “exit point” at which labor’s ability to define public policy in its interest makes it useless for the industry to extend any support to the “labor” party.24 At successively higher levels of class conflict (equivalent to a move out along the horizontal axis), more and more industries drop out of the labor party, until at length none are left and the system passes from an American “pluralist” type to a classic, highly polarized “European” party system.

FIGURE 2.1. The Labor Constraint: Industries Vary Widely in Their Sensitivity to Labor

Formidable problems naturally stand in the way of attempts to apply a scheme such as this to any event as complex as the New Deal. For example, empirically ascertaining which parties or policies a firm or an industry is supporting at a particular point can be very laborious.25 It is also clear that some industries can afford to extend at least some support to both parties (though both logic and history suggest that this support will not be offered equally). But already some clearly testable propositions can be generated that have obvious relevance to the New Deal. For example, one would not expect that a relatively labor-intensive economy, dominated by textiles, steel, and shoes, would find it easy to accommodate mass movements for unionization. By contrast, if it turned out that in the decade immediately preceding the New Deal the characteristic modern American form of capital-intensive enterprise, the giant integrated, multinational petroleum company, ascended to the pinnacle of the American industrial structure, an important clue to the historical uniqueness of the New Deal has probably been located. Similar reasoning might explain why other countries, like Germany, seemed able to transplant the New Deal in the 1950s but not in the 1930s, or why deradicalized labor parties in Europe were often able to cooperate more closely with big business after World War II than before it.

But if characterizing parties—and, by extension, party systems—according to their labor sensitivity illuminates the politics of advanced capitalist countries, it is by itself obviously not enough. Class conflict, after all, scarcely exhausts the sources of political turbulence. Accordingly, the single-dimension, simple class-conflict model needs to be supplemented if it is to have much predictive value. In principle, the number of complicating supplementary issues could be infinite, dashing all hopes for parsimonious explanation and making analyses impossibly difficult.

During most of the period that concerns me here, comparatively few issues that were not broadly labor-related were potent enough to stir major, persisting conflicts within the generally laissez-faire American political system.26 Accordingly, while references to other dimensions are sometimes necessary for detailed discussion of particular cases and are required for an analysis of the actual transition from the System of ’96 to the New Deal, the most general (or “normal”) case needs but a single extra dimension—one that summarizes the competitive positions of various firms and industries within the world economy. Thus I divide firms into “internationalists,” whose strong position vis-à-vis international competitors leads them to champion an open world economy with minimal government interventions that would hinder the “free” market-determined flow of goods and capital; and “nationalists,” whose weakness in the face of foreign rivals drives them to embrace high tariffs, quotas, and other forms of government intervention to protect themselves (see figure 2.2).27 Combining this line of cleavage with the class-conflict dimension yields an analysis in which each firm or industry as a whole can be located at two coordinates: one summarizes the characteristics of its production process with respect to the workforce; the other, its situation in the world economy.

A party system as a whole can now be characterized in these terms. If most elements of the industrial structure cluster tightly together in one or another “quadrant” of figure 2.3, political conflict within the system is likely to be muted.28 Assuming that the workforce can be contained, the conditions are satisfied for the stable hegemony of a particular historical bloc. In sharp contrast, should class conflict and the world economy combine to scatter large firms and major industries among all the quadrants, the party system would be incoherent. Similarly, figure 2.3’s sharp division between two diagonally opposed quadrants yields a rather stable, fairly well-balanced, two-party system in which the less labor-intensive bloc, by allying with labor, might well achieve hegemony.

FIGURE 2.2. International Competitive Status of Selected U.S. Firms and Industries in 1929 and 1935

Source: Based on M. Wilkins, The Maturing of Multinational Enterprise (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1974), and sources cited in note 27.

Notes: In several cases notable intra-industry differences are not reflected here, especially in petroleum. There is no significance to the distance between categories, only to the ordering.

FIGURE 2.3. Industrial Structure and Party Competition: A Stylized Two-Party Case

From the Statics of Party Competition to the Dynamics of Party Systems

The account of partisan choice and party systems presented here is static in the sense that it applies to actions and events at a single moment in time. Yet, as the earlier allusion to the rise of the major oil companies during the Roaring Twenties suggests, the static theory can be extended to cover dynamic issues. It thereby renders possible a fresh explanation of the oft-debated and still not entirely resolved puzzles surrounding the timing and sequence of the major New Deal policy initiatives.

Perhaps the most convenient way to begin is to refer again to figure 2.3. Instead of the diagonally opposing clusters of firms it shows, however, imagine the figure’s space as representing the American political system around 1900. In that case, nearly all the dots will cluster tightly in quadrant 2, indicating the power bloc defined by the almost monolithically Republican business community of that period, whose component firms were nearly all strongly protectionist and labor-intensive.29

If the figure were drawn a quarter-century later it would exhibit substantial differences. In the interval, major cumulative changes in industrial structure have occurred. World War I and the boom of the 1920s have spurred the mechanization of production. Large, science-based corporations have become far more prominent. The war has also transformed the United States from a net debtor to a net creditor in the world economy. Textiles have withered away in the Northeast, meat packing and steel have declined relative to oil, and so forth. Virtually all these developments affect the distribution of firms in regard to labor and trade policy, and thus, to some degree, transform the party system. In terms of the graphical analysis many dots have begun to migrate. New ones—representing firms in developing industries—have suddenly appeared in new places while some old dots, marking marginal firms in dying industries, have disappeared.

In the United States after World War I, the analysis implies, a new bloc of big, capital-intensive firms that increasingly dominate the world market for their products is beginning to grow in quadrant 4, diagonally opposite the old System of ’96 bloc. It is obvious that such a party system is headed for trouble, with or without a major depression. As firms increasingly move into the other quadrant, the old bloc will clearly come under strain. As it disintegrates and the new bloc, which will dominate the next party system, is born, policy fights and transaction costs associated with public policy-making will rise. Political stalemates are likely to increase and the sense of a vacuum forming will probably spread, as traditional political alliances evaporate and surprising new ones emerge.

The exact form the transition from one party system to another will take, however, depends critically on the level of national income. National income is important for two different reasons. First, over time it exercises what might be termed “direct effects” on the location of business firms on the two “primary” dimensions of labor and international economic policy. Second, and much less obviously, major fluctuations in the trend of national income roil the transition to a new party system by temporarily forcing certain characteristic kinds of new issues to the fore, issues that supplement or even momentarily replace labor and international economic policy as pivots for the system.30 The nature of these “secondary” tensions (“secondary” in contrast to the “primary” issues of labor and trade, not in the sense of having lesser importance) is perhaps best spelled out by tracing how they combine with the “direct effects” of changes in national income to define two distinct, idealized models of the transition path from one party system to another.

Transition via Prolonged Boom. In the first transition path, national income sustains a high rate of growth for a substantial period of time. The prolonged boom consequently exerts powerful “direct effects” on the party system’s primary defining axes of labor and trade by rapidly transforming productive techniques and the operation of firms. In the boom of the 1920s, for example, some firms and sectors experienced high rates of technical change and mechanization, and consequently changed their position on labor policy. With the major exception of the chemical industry, which still lagged behind the Germans, they commonly changed position on international economic policy as well. New leading sectors also appeared, of course, while some older industries slowly disappeared.

If growth were sustained, successive scattergraphs of the party system would show a continuous, gradual migration of more and more firms or sectors from one quadrant to the other as the new bloc gained strength and the older one declined. Parallel to these shifts, political histories would probably chronicle a widening sense of dislocation, followed by increasingly intense polarization and, at last, the emergence of a distinctly new ruling bloc. But for all the conflict such an account might record, moments of high drama would be few and far between. As a whole the process would be protracted and, in principle, straightforward. Marked by an absence of complicating issues and identifiable turning points, this sort of change would by itself pose comparatively few puzzles for political analysis.

Even a transition of this kind, however, would probably be complicated by at least two sorts of “secondary” tensions generated by the process of growth itself. A sustained boom, for example, is highly likely to bring about the rise of new firms and sectors. If older business elites do not succeed in entering these fast-growing sectors, whole new groups of entrepreneurs will emerge. While most major battles between what are commonly advertised as “new” and “old” elites turn out to involve clashes between different sectors on primary issues of labor and trade policy (and thus call for no special interpretative apparatus), the rise of new entrepreneurs can in itself generate a certain degree of tension. Or, as has often happened in American history, a major boom scrambles existing financial markets. As financial innovations proliferate to meet historically unprecedented demands for finance from whole new regions, sectors, and firms, competition heats up. Older market shares become unbalanced, and pressures build for regulatory change. While such “secondary” cleavages normally lack the permanence of the “primary” conflicts (since, after all, new elites eventually mature, and large-scale uncertainty resulting from long-term developmental pressure in the financial system typically results in “landmark” legislation that resolves whole ranges of issues), such conflicts confuse the transition to a new party system.

Transition via Economic Depression. The most dramatic complications of the transition from one party system to another, however, arise from the simple fact that the history of the American political economy is far from a chronicle of continuous growth and progress. Along with the booms and growth spurts that help build and destroy political coalitions come cyclical instability and, often, deep and protracted depressions. These catastrophic events define the second transition path.

The statistical record of depressions and party realignments demonstrates that even a very steep downturn will not by itself suffice to wreck an entrenched party system.31 But if, as in 1837, 1857, 1893–94, and the 1930s, the party system is already decaying because of a previous boom, then a shattering depression is likely to generate a variety of new pressures that will further complicate the transition to a new party system.

Several distinct sorts of pressure are likely to emerge. First of all, the “direct effects” of deep depressions are frequently very dramatic. While a depression, unless it persists for many years, will not greatly affect the labor intensity of an economy’s production processes (though, of course, speedups and spreading anxieties about unemployment can deeply color work relations, particularly in labor-intensive sectors), it will certainly produce abrupt changes in different firms’ preferred international economic policies. When an American depression coincides with a world economic collapse, for example, many American industrialists are drastically affected by the strategies their foreign competitors adopt. If the volume of world trade shrinks, and export drives proliferate as domestic demand collapses, economic nationalism is certain to grow within the business community. If the depression persists, even many previously successful “internationalists” will be forced to change colors. In terms of the scattergraphs of the System of ’96, this implies a swift and substantial reshuffling of positions along the nationalist-internationalist axis—in a direction that in the short run dramatically reverses long-term trends working in favor of an open economy.

The collapse of political blocs favoring internationalism is, however, only one (direct) effect of prolonged drops in the level of national income. Such periods also typically lead to a whole series of uniquely “pathological” (in the sense of non-normal and transitory) secondary tensions. Sustained economic decline, for example, normally intensifies economic rivalries, leading to waves of bankruptcies and defensive mergers. Appearing on the scattergraphs as abrupt disappearances and sudden relocations of dots, these, if sufficiently numerous, can redraw the shape of the whole party system almost overnight. Even if no general merger wave occurs, the positions of the largest firms in the system often change dramatically as the strongest surviving business groups attempt to capitalize on their positions and take control of other, momentarily undervalued, assets.

A prolonged depression is also likely to trigger two further sorts of “secondary” conflicts (or, perhaps more precisely, sets of secondary conflicts), which, when they suddenly burst forth, are likely to mystify observers used to thinking in terms of categories derived from the preceding boom.

The first of these additional tensions can be readily identified: it is a dramatic rise in the importance of the money supply as a political issue. Whereas during most boom periods money is fairly readily available at a reasonable real cost—and thus as a political issue is unlikely for most businesses to bulk as large as labor and international economic policy—persisting economic declines will eventually generate powerful movements for lower interest rates and an increase in the money supply. This process, of course, takes time to start. In the early stages of a depression, for example, most firms react by cutting production, laying off workers, and, in the less oligopolistic parts of the economy, cutting prices. But while firms may briefly welcome reductions in the level of economic activity—because they cool off demands for wage increases and make the labor force more tractable—no one is likely to remain enthusiastic if the downturn persists and cuts deeply into profits. Nevertheless, for a while the bulk of the business community, or at least those in it not facing immediate bankruptcy, put up with the deflationary adjustment process, since generations of academic economists have persuaded most of them that deflation is the path to revitalization.

In all modern economies, however, it has eventually become clear that deflation does not always restore the conditions for profitable accumulation at a price most of the business community can afford. As this lesson dawns, and losses mount even among the rich, firms and sectors begin to divide over measures for reflation—either an increase in the money supply, which, of course, carries with it the prospect of abandoning the gold standard or other international mechanisms regulating the volume of money in circulation; or higher government expenditures, which almost irresistibly expand the money supply as the government deficit is financed; or both. On one (deflationary) side are firms that want above all to preserve the value of financial assets, to retain foreign deposits (which they will lose as the currency devaluation consequent upon the abandonment of gold takes hold), and, perhaps, to protect what they believe to be the long-run best interests of the international financial system. Chief among the proponents of deflation are big international banks, insurance companies, and bond holders. Opposed to them is nearly everyone else for whom the overriding priorities increasingly become the maintenance of any degree of purchasing power, escape from increasingly heavy fixed charges, devaluation to shore up fading international competitiveness, or some combination thereof. This latter camp includes many prominent industrialists and retailers, as well as farmers and ordinary people.

While many accounts of deflationary periods stress the misery they have brought to farmers, an industrial sector analysis of this transition’s pathology highlights the role of certain types of industries, namely those with large amounts of fixed capital. Because their capital is fixed, these firms take enormous losses as the depression persists and they have to run far below capacity for long periods. Many will have borrowed heavily in the preceding boom to finance expansion and thus feel pressure from financiers; but even where debt service is light, the opportunity costs of underutilized fixed capital still remain enormous. Firms enjoying very strong oligopolistic positions may be able to cope by keeping prices up; many others that are heavily dependent on bank financing may not dare to protest the deflation. These two exceptions notwithstanding, the logic of the demand for reflation yields an unambiguous prediction of which industries will lead the “emergency reflation” coalition “for national economic recovery”: giant, capital-intensive industries whose prices are breaking and that are relatively independent of banks (large oil companies in the Depression, for example).

Once the forces of national recovery begin to march (and since by that moment most of them have become ardent economic nationalists and many are also labor-intensive, they do indeed march), a final kind of secondary conflict is likely to break out within the financial sector.

It is, of course, quite possible—and it certainly was the case in the 1930s—that segments of the banking community may already be at one another’s throats for various “secondary” reasons mentioned earlier: because rising entrepreneurs challenge older elites who happen to be bankers; because of competitive pressures derived from secular changes in the financial structure, changes that the previous boom brought about; or because powerful financial groups come into conflict as they try to aggrandize their own relatively strong positions as everyone else’s asset values are collapsing.

As economic disaster continues unabated and pressures mount for “national recovery,” however, fragmentation within the financial community is for several reasons likely to increase enormously. First, the spiraling collapse of the international economy increasingly calls into question older political alliances premised on a growing national income (and volume of trade). At length even some financiers will begin to break ranks. Obviously, defectors are most likely to come first and in the greatest numbers from among investment bankers with the smallest stakes (though their stakes may still be substantial by comparison with other sectors’) in the business of international banking and commercial bankers with the strongest ties to those parts of domestic industry which are up in arms over reflation—for example, the oil industry. Once this fragmentation gets under way it is likely to pick up momentum as it becomes enmeshed in debates over financial reform stimulated either by the previous boom or by the increasingly urgent monetary debates of the economic crisis.32

Together with the direct effects of falling national income, these accumulating secondary tensions will immensely complicate the conflicts over labor and trade generated by the preceding boom. What during the period of prosperity (the first transition path) had seemed so clear—the rapid growth of a powerful bloc of internationally oriented, capital-intensive firms with their own distinct interests in more liberal trade and labor policies—now appears hopelessly confused. The development of the internationalist bloc first slows, then ceases altogether. As income continues to fall, history almost appears to be running backward. Economic nationalism spreads like wildfire. As older alliances premised on a growing international economy break down, “secondary” tensions and pathologies characteristic of depressions get full play and further scramble previous alignments. At length, even big banks begin openly to attack one another and investment banking is riven by dissent. A “national recovery” coalition comes to power as the internationalists scatter.

In the short run, the strange new package of public policies that holds this coalition together appears only tangentially related to the primary tensions that had dominated the system for so many years. For, given a sufficiently deep contraction of the international economy, this transition coalition inevitably takes a strongly nationalist form, thus flying in the face of previously dominant trends that favored increasing international integration. But this impression is an illusion; it derives entirely from the special circumstances of the colossal decline in national income. As soon as recovery starts and other transition issues (such as monetary and banking reform) begin to be resolved, the old lines of cleavage over primary issues reappear. The national recovery coalition blows apart over labor and foreign economic policy, and the long-run trends evident in the preceding boom reassert themselves.

In the latter part of this article I trace how a distinct multinational bloc first emerged in the United States after World War I. Gaining coherence during the boom of the 1920s, it virtually fell apart in the early 1930s, until national income began very slowly to rise again, during FDR’s “Second New Deal.” It was only then that a fresh party system, crowned by a new historical bloc, could emerge.

2. HIGH CARDS IN THE NEW DEAL

I begin with a brief analysis of the System of ’96 as it looked in its pre-World War I “stable phase.”33 After identifying the institutional basis of the period’s well-known Republican hegemony in the relative unity of most industry and major finance, I turn to the system’s crisis at the end of World War I. By tracing how the dislocated world economy combined with existing social tensions to divide a business community that until then had been solidly Republican, it becomes clear how the older hegemonic bloc of the System of ’96 began breaking into two—one part intensely nationalist, protectionist, and (with a few notable exceptions) generally labor-intensive; the other oriented to capital-intensive production processes and free trade.

A newer multinational bloc rose to power during the New Deal. In accord with my earlier discussion of variations in national income and the two distinct paths of transitions between party systems, I distinguish three stages in the new bloc’s ascent. The first includes the period immediately following World War I and the great boom of the 1920s. In this interval of generally rising national income (the first transition path), the leading firms of the emergent multinational bloc began to articulate their interests on labor and trade separately from the rest of the business community. Along with several secondary cleavages that the boom generated and a feature peculiar to American society in the 1920s (Prohibition, discussed below), the efforts this bloc made to alter American policy toward labor and the rest of the world created considerable turbulence in American politics. By the 1928 election, the accumulating tensions had “dealigned” the existing structure of U.S. politics.

The second stage of the new bloc’s rise to power occurs after the great crash of 1929 and major events associated with it, including the East Texas oil field discoveries and the British abandonment of the gold standard. In this interval, the political coalition that had dominated the United States for a generation collapsed completely, setting off a scramble for power. However, as I will show, the wreck of the System of ’96 amid frightful deflation (the second transition path) did not immediately bring the multinational bloc to power. Instead, with the collapse of the international economy, Hoover’s determination to remain on the gold standard at all costs sharply divided the business community, including the multinational bloc.

Out of these tensions, by sequential stages, came the American political world we now know: first, a gradual massing of nationalist and inflationist business groups (and farmers); second, the rapid emergence of increasingly bitter divisions within the financial community as heretofore “secondary” disputes over the control and future shape of the financial system escalated, and older alliances based on a growing economy lost their raison d’être; third, the temporary coalescence during the First New Deal of the nationalists and inflationists with a famous group of financiers who sought to challenge the preeminence of the House of Morgan; and, finally, as soon as decline was arrested and the long-run logic of the first transition path could assert itself, a slowly improving economy that began spawning epic class and trade conflicts, leading to the triumphant reemergence of the multinational bloc during the Second New Deal.

A Boom and a Bloc: The First Transition Path, 1918–1929

At the center of the Republican Party under the System of ’96 was a massive bloc of major industries, including steel, textiles, coal, and, less monolithically, shoes, whose labor-intensive production processes automatically made them deadly enemies of labor and paladins of laissez-faire social policy.34 While a few firms whose products dominated world markets, such as machinery firms, agitated for modest trade liberalization (aided occasionally by other industries seeking specific export advantages through trade treaties with particular countries), insistent pressures from foreign competitors led most to the ardent promotion of high tariffs.35

Integral to this “national capitalist” bloc for most of the period were investment and commercial bankers. These had abandoned the Democrats in the 1890s when Free Silver and Populist advocates briefly captured the party. The financiers’ massive investments in the mid-1890s and after, in huge trusts that combined many smaller firms, gave them a large, often controlling, stake in American industry, brought them much closer to the industrialists (especially on tariffs, which Gold Democrats had abominated), and laid the foundation for a far more durable attachment to the GOP.36 Most financiers also shared the industrialists’ enthusiasm for aggressive foreign policies directed at the other great powers, especially in Latin America, though they were sometimes less willing to challenge the British, whose capital (in many senses) remained the center of world finance.

World War I disrupted these cozy relations between American industry and finance. Overnight the United States went from a net debtor to a net creditor in the world economy, while the tremendous economic expansion induced by the war destabilized both the U.S. and the world economy.37 Briefly advantaged by the burgeoning demand for labor, American workers struck in record numbers and for a short interval appeared likely to unionize extensively.38 Not surprisingly, as soon as the war ended a deep crisis gripped American society. In the face of mounting strikes, the question of U.S. adherence to the League of Nations, and a wave of racial, religious, and ethnic conflicts, the American business community sharply divided.

On the central questions of labor and foreign economic policy, most firms in the Republican bloc were driven by the logic of the postwar economy to intensify their commitment to the formula of 1896. The worldwide expansion of industrial capacity the war had induced left them face to face with vigorous foreign competitors. Consequently, they became even more ardent economic nationalists. Meeting British, French, and later German and other foreign competitors everywhere, even in the U.S. home market, they wanted ever higher tariffs and further indirect government assistance for their export drives. Their relatively labor-intensive production processes also required the violent suppression of the great strike wave that capped the boom of 1919–20 and encouraged them to press the “open shop” drive that left organized labor reeling for the rest of the decade.

However, this response was not universal in the business community. The new political economy of the postwar world pressured a relative handful of the largest and most powerful firms in the opposite direction. The capital-intensive firms that had grown disproportionately during the war were under far less pressure from their labor force. The biggest of them had by the end of the war also developed into not only American but world leaders in their product lines. Accordingly, while none of them were pro-union they preferred to conciliate rather than to repress their workforce. Those that were world leaders favored lower tariffs, both to stimulate world commerce and to open up other countries to them. They also supported American assistance to rebuild Europe, which for many of them, such as Standard Oil of New Jersey and General Electric, represented an important market.

Joining these latter industrial interests were the international banks. Probably nothing that occurred in the United States between 1896 and the Depression was so fundamentally destructive to the System of ’96 as the World War I-induced transformation of the United States from a net debtor to a net creditor in the world economy. The overhang of both public and private debts that the war left in its wake struck directly at the accommodation of industry and finance that defined the Republican Party. To revive economically and to pay off the debts, European countries had to run export surpluses. They needed to sell around the world, and they, or at least someone they traded with in a multilateral trading system, urgently needed to earn dollars by selling into the United States. Along with private or governmental assistance from the United States to help make up war losses, accordingly, the Europeans required a portal through the tariff walls that shielded Republican manufacturers from international competition. (Following the procedures described earlier, Figure 2.4 estimates as closely as possible the shape of both blocs. They are defined—somewhat arbitrarily—to include the top thirty firms [ranked according to assets], the big banks, and cotton textiles, by far the largest American industry characterized by small firms.)39

The conflict between these two groups runs through all the major foreign policy disputes of the 1920s: the League of Nations, the World Court, the great battles over tariffs, and the Dawes and Young plans. Initially, the older, protectionist forces won far more than they lost. They defeated the Leagues, kept the United States out of the World Court, and raised the tariff to ionospheric levels. But most trends in the world economy were against them. Throughout the 1920s the ranks of the largely Eastern internationalist bloc swelled.40

Parallel to the multinational bloc’s increasing numbers was its growing unity of interest. In 1922, the British opened negotiations to admit Standard Oil interests into Iraq. A milestone in the integration of the world economy, this step and related developments also removed a major obstacle to concrete forms of cooperation among the internationalists.41 Indeed, it had been a split between big oil and big banks over the specific terms of the peace treaty that was pivotal in defeating the League of Nations. The original American champions of the League, as Massachusetts Senator Henry Cabot Lodge’s correspondence reveals he was vividly aware, were international financiers located mostly in port cities; free-trading merchants like Edward A. and A. Lincoln Filene; and the relative handful of American industrialists who favored either low tariffs (e.g., Phelps Dodge’s Cleveland Dodge, a major supporter and close friend of Woodrow Wilson) or direct foreign investment. By contrast, the League terrified most American manufacturers who feared, as the American Tariff League expressed it, that “the League of Nations is simply a rally ground for free traders and all who are opposed to the doctrine of ‘adequate protection’ for the industries and labor of the United States.”42

FIGURE 2.4. The New Deal Coalition, ca. 1929 and 1935

Notes: Vertical axis is ordinal, as in fig. 2.2. Companies and industries located left and above the dashed line were far more likely to favor the New Deal; the line thus encloses the leaders of the capital-intensive free trade bloc in the 1920s and 1930s. Between the late 1920s and the mid-1930s the copper industry changed position. In the 1920s it belongs near “other auto companies”; in the 1930s, near “steel.” See note 27.

Led by groups like the American Tariff League, the Boston Home Market Club (a long-time political base of Lodge’s, “the Senator from Textiles”), and the League for the Preservation of American Independence—dominated by upstate New York industrialist Stuyvesant Fish and Louis A. Coolidge, a close friend of Lodge’s and treasurer of the giant Boston-based United Shoe Machinery (which was probably seeking to protect its clientele among U.S. shoe producers)—these “Irreconcilables” launched a powerful counterattack.43 Their success came only because of a fatal split among the internationalists. At the climax of the struggle over the League of Nations, the Standard Oil companies, which had already come out for tariff reform, were locked in a bitter struggle with the British over control of Middle Eastern and Latin American oil reserves. Because of the advantages the League was thought to afford British interests, Rockefeller, Standard Oil policy adviser and Rockefeller family associate Charles Evans Hughes, and other dedicated internationalists allied with petroleum producers were able to endorse the League only “with reservations.”44 Their opposition, added to that of Lodge’s “Irreconcilables” and many other protectionist spokesmen, helped doom Wilson’s original plan. Warren Harding’s subsequent plan to resubmit a compromise measure, endorsed in principle by all the internationalists, was shelved after it was bitterly attacked by the nationalists; and after the multinational bloc discovered it could achieve its immediate foreign-policy objectives by working unofficially around Congress with key executive-branch functionaries and New York Federal Reserve Bank officials.45

Along with its increasing internal homogeneity, the multinational bloc enjoyed several other long-run advantages, which helped enormously in overcoming the new bloc’s relative numerical insignificance vis-à-vis its older rival. The multinational bloc included many of the largest, most rapidly growing corporations in the economy. Recognized industry leaders with the most sophisticated managements, they embodied the norms of professionalism and scientific advance that in this period fired the imagination of large parts of American society.46 The largest of them also dominated major American foundations, which were coming to exercise major influence not only on the climate of opinion but on the specific content of American public policy.47 And, while I cannot pause to justify the claims in this article, what might be termed the “multinational liberalism” of the internationalists was also aided significantly by the spread of liberal Protestantism; by a newspaper stratification that brought the free-trade organ of international finance, the New York Times, to the top; by the growth of capital-intensive network radio in the dominant Eastern, internationally oriented environment; and by the rise of major news magazines. These last promised, as Raymond Moley himself intoned while taking over what became Newsweek, to provide “Averell [Harriman] and Vincent [Astor] . . . with a means for influencing public opinion generally outside of both parties.”48

Closely paralleling the business community’s differences over foreign policy was its split over labor policy. Analysts have correctly stressed that the 1920s were a period of violent hostility toward labor unions. But they have largely failed to notice the significant, sectorally specific modulation in the tactics and strategy employed by American business to deal with the labor movement.

The war-induced boom of 1918–19 cleared labor markets and led to a brief but sharp rise in strikes and the power of labor. A White House conference called by Wilson to discuss the situation ended in stalemate. John D. Rockefeller Jr. and representatives of General Electric urged conciliatory programs of “employee representation” (company-dominated, plant-specific works councils). Steel and other relatively labor-intensive industries, however, rejected the approach. Led by Elbert Gary, head of U.S. Steel, they joined forces, crushed the great steel strike of 1919, and organized the American-plan drives of the 1920s.49

Rockefeller and Gary broke personal relations. Rockefeller supported an attack on the steel companies by the Inter-Church World Movement, an organization of liberal Protestants for which he raised funds and served as a director. Later he organized a consulting firm, Industrial Relations Counsellors, to promote nonconfrontational “scientific” approaches to labor conflict. For a while the firm operated out of his attorney’s office, but eventually it acquired space of its own. It continued to receive grants from the Rockefeller Foundation and to involve Rockefeller personally.50

Industrial Relations Counsellors assisted an unheralded group of capital-intensive firms and banks throughout the 1920s—a group whose key members included top management figures of General Electric, Standard Oil of New Jersey, and partners of the House of Morgan. Calling themselves the “Special Conference Committee,” this group promoted various programs of advanced industrial relations.51

Industrial Relations Counsellors worked with the leading figures of at least one group of medium-sized firms. Perhaps ironically, they were organized in the Taylor Society, once the home of Frederick Taylor’s well-known project for reorganizing the labor process. Two types of firms comprised this group: technically advanced enterprises in highly cyclical (hence, in the 1930s, highly depressed) industries like machine tools, and medium-sized “best practice” firms in declining sectors. Mostly located in the Northeast, these latter firms hoped that the introduction of the latest management and labor relations techniques would afford them cost advantages over burgeoning low-wage competitors in the South. A sort of flying buttress to the core of the multinational bloc, most of these firms strongly favored freer trade, while several future New Dealers, including Rexford Tugwell and Felix Frankfurter, worked with them.52

The leading figures in Industrial Relations Counsellors and their associates (who included, notably, Beardsley Ruml, head of the Spelman Fund, a part of the Rockefeller complex that began funding the first university-based industrial relations research centers) played important roles in virtually all major developments in labor policy across the 1920s. These included the campaign that forced the steel industry to accept the eight-hour day (which Herbert Hoover led in public); the milestone Railway Labor Act; and the increasing criticism of the use of injunctions in labor disputes (a legal weapon that was an essential element of the System of ’96’s labor policy) that eventually led to the Norris-La Guardia Act.53

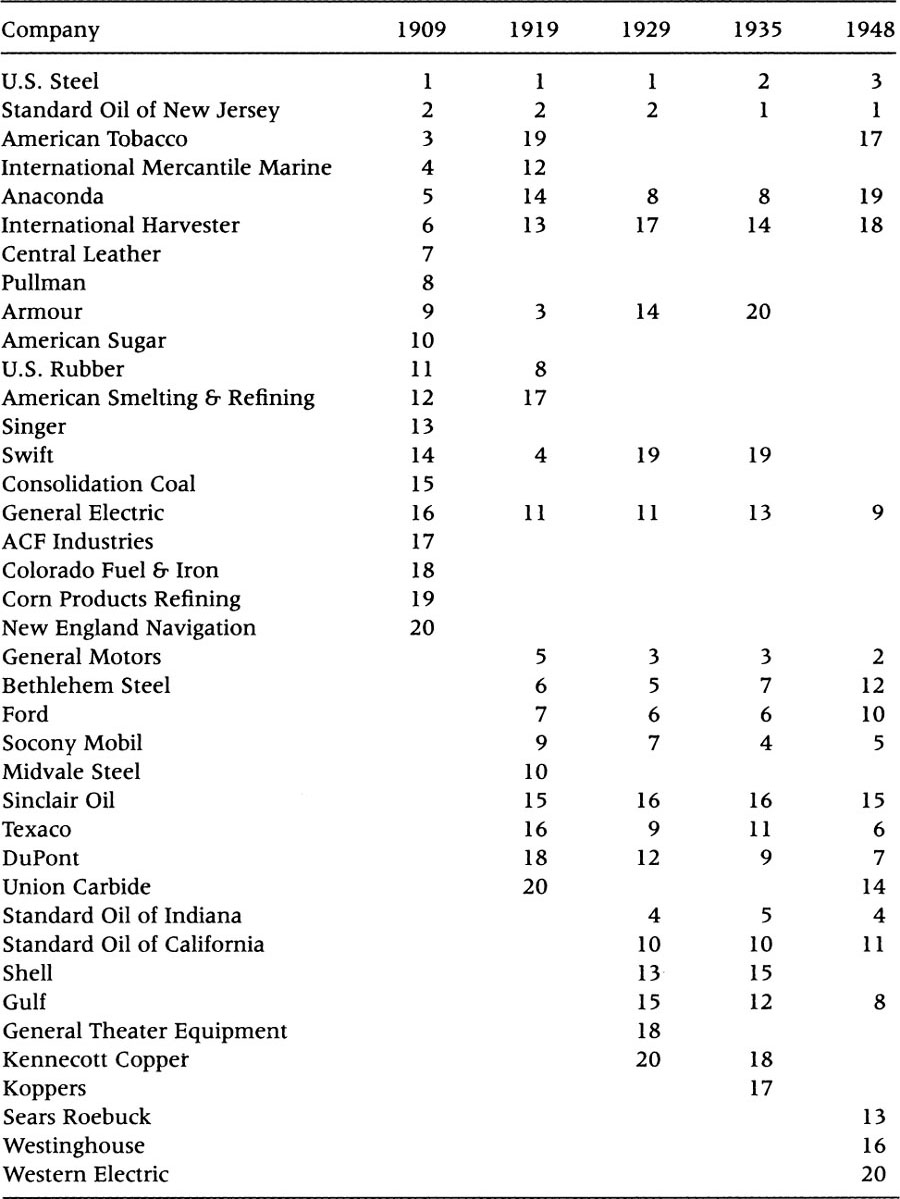

Under all these accumulating tensions the elite core of the Republican Party began to disintegrate. The great boom of the 1920s exacerbated all the primary tensions over labor and international relations just described, while it greatly enhanced the position of the major oil companies and other capital-intensive firms in the economy as a whole (see table 2.1). Though their greatest effects came after the downturn in 1929, secondary tensions also multiplied during the boom. One, which affected partisan competition even in the 1920s, concerned investment banking. A flock of new (or suddenly growing) houses sprang up and began to compete for dominance with the established leaders: the House of Morgan and Kuhn, Loeb. In time these firms would produce a generation of famous Democrats: James Forrestal of Dillon, Read; Averell Harriman of Brown Brothers Harriman; Sidney Weinberg of Goldman, Sachs; John Milton Hancock and Herbert Lehman of Lehman Brothers. Because many (though not all) of these bankers were Jewish, the competition with Morgan almost immediately assumed an ugly tone. J. P. Morgan Jr. quietly encouraged Henry Ford’s circulation of the notorious Protocols of the Elders of Zion in the early 1920s, and later his bank forbade Morgan-Harjes, the firm’s Paris partner, to honor letters of credit from Manufacturers Trust, a commercial bank with strong ties to Goldman, Sachs, and Lehman Brothers.54

In commercial banking, rivals also began to contest Morgan’s position. The Bank of America rose rapidly to become one of the largest commercial banks in the world. Though the competition did not yet take partisan form, the bank bitterly opposed Morgan interests, which attempted to use the New York Federal Reserve Bank against it. Morgan also was hostile to Joseph Kennedy and other rising financial powers.55

TABLE 2.1 Largest American Industrials, 1909–1948 (Ranked by Assets)

Source: A.D.H. Kaplan, Big Enterprise in a Competitive Setting (Washington, D.C.: Brookings, 1962), pp. 140 ff.

The cumulative impact of all these pressures became evident in the election of 1928. Some of the investment bankers, notably Harriman, turned to the Democrats. Enraged by the House of Morgan’s use of the New York Fed to control American interest rates for the sake of its international objectives, Chicago bankers, led by First National’s Melvin Traylor, organized and went to the Democratic convention as a massed body.56

Most sensationally of all, elements of the arch-nationalist, previously rockribbed Republican chemical industry went over to the Democrats. A more vivid illustration of how primary and secondary tensions generated by the boom were dealigning traditional elite alliances could scarcely be found. For more than a generation, the chemical industry had been solidly Republican. Industry spokesmen and publications never ceased observing that only the GOP tariff walls stood between them and ruin at the hands of foreign, especially German, competitors.57 Before 1928 it would have been unthinkable for DuPont or some Union Carbide executives openly to support a national Democrat.

Behind this dramatic reversal is a political evolution that has three main parts. The special situation of the DuPont family in relation to other great fortunes in American society of that period constitutes the point of departure. Such statistics as are available indicate that the bulk of the truly colossal fortunes in America were made prior to World War I. (Not that a great amount of money has not been made since, but few newer fortunes have been generated to match those of Rockefeller, Morgan, or Henry Ford.)58 The rise of the DuPonts, however, began with their profits from World War I explosives sales and continued with their investment in General Motors.59 By comparison with most of the American superrich in the 1920s, the DuPonts’ ratio of wealth to income was considerably below average. Consequently, while all the rich were strongly in favor of reduced taxes, which had risen as a consequence of the war, the DuPonts had a bigger incentive than most.60

Their spectacular success in the 1920s rendered the situation even more urgent. Not only did their General Motors investments and the DuPont corporation grow, but so did their position in United States Rubber and other large companies. By about 1925 Pierre DuPont had decided that reduced income taxes would require finding another source of revenue for the government. Consequently he, his brothers Irénée and Lammot, and several close associates, including John J. Raskob, took over the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment (AAPA). They campaigned throughout the country, opening contacts with hundreds of newspapers, aiming to encourage a repeal of national Prohibition and then to levy taxes on liquor. At the start, the campaign was bipartisan: “As our average tax collections for the years 1923–26 from individuals and corporations were $1,817,000,000 resulting in a considerable surplus, it is fair to say that the British liquor policy applied in the United States [i.e. the legalization of liquor] would permit the total abolition of the Income Tax both personal and corporate. Or this liquor tax would be sufficient to pay off the entire debt of the United States, interest and principal, in a little less than fifteen years.”61

The enormous departure this program represented from previous norms of the American upper class merits some attention. For over a century prohibition had been a cause not only of rural drys but, more importantly, of major manufacturers.62 Large fortunes like the Rockefellers’, together with some big retailers like J. C. Penney, had been lavish contributors to the Anti-Saloon League and other proponents of liquor restrictions.63 Their opposition to liquor was rationalized on religious grounds, although it was certainly also rooted in their desire to control unruly lower-class behavior.64 DuPont, however, represented the cutting edge of science-based industry, the most powerful secularizing force in history.

But the DuPont interests had more concrete objectives than witnessing the cultural transformation of modern capitalism. Friction was increasing between this newly ascendent group and other large American fortunes—in particular with the House of Morgan, which had a strong, though minority, position in General Motors. After several unpleasant encounters, including a dispute over how much DuPont enterprises should pay for Morgan financing, the DuPonts made a bid for a share of Morgan’s own U.S. Steel. After DuPont began a massive purchase of U.S. Steel stock, the Federal Trade Commission began an investigation (on a few hours’ notice), forcing DuPont to back off.65

Meriting separate mention as a cause of the “dealignment” of the party structure was an aspect of the rivalry with Morgan that related directly to the great foreign economic policy dispute that marked the 1920s but has so far been virtually unappreciated: American attempts to aid the reconstruction of Germany. American officials had seized German patents in the chemical and other industries during the war. Though the peace agreement (the United States, of course, did not ratify the Versailles Treaty) with Germany acknowledged the U.S. right to the patents, a Homeric struggle quickly broke out over what was to be done with them. Internationalists wanted to return at least some of them so that the Germans could build up an export capacity and pay off war debts. The chemical industry wanted to keep them.66

At first, the chemical industry prevailed. The Chemical Foundation was established to hold and license the patents. DuPont held about one-third of the stock, and the rest was held by other concerns. The foundation became the battleground for internationalist and protectionist forces. German chemical company agents worked with American bankers and government officials, including senators and President Harding himself, to get the patents back. To keep track of these efforts, the Chemical Foundation’s able head, Francis P. Garvan, engaged private detectives. The surviving reports from these men, who were probably former Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agents, can be partially verified from other sources and vividly testify to the tensions that quickly developed.67

The banks and their allies could not overcome protectionist opposition. Former Attorney General Harry Daugherty was indicted for taking a bribe to help return German assets.68 J. Edgar Hoover, a close political ally of Chemical Foundation attorney A. Mitchell Palmer and Garvan, was appointed, and removed suspected German agents from the FBI. And the government lost the suit it brought to force the Chemical Foundation to return the patents—in Wilmington, Delaware.

Continuing strains on the world economy intensified the pressure to aid Germany and heightened the antagonism between DuPont and the multinationals. Allen Dulles and other high officials in the U.S. Department of State attempted to stop American munitions exports that competed with the Germans; meanwhile, the Chemical Foundation was actively encouraging French resistance to Allied plans to put Germany back on its feet.69 As American bankers helped organize huge loans to the Germans and looked on while most of the German chemical industry consolidated into one gigantic combine—I. G. Farben—tensions mounted.70

Although the DuPont Co. had repeatedly explored (and would continue to explore, without much success) possibilities for coming separately to terms with the Germans, Pierre’s brother Irénée, the president of the company, hand-delivered a stiff note protesting American loans for potential German competitors to Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover.71 The Chemical Foundation and other industry leaders joined in the campaign, but their efforts drew strong opposition. When the newly established Institute of Economics in Washington, D. C., prepared a skeptical report about foreign loans, the banks intervened and threatened its grants. Shortly thereafter the institute merged with another organization (creating the modern Brookings Institution).

I learned yesterday, confidentially but reliably that the continued existence of the Institute of Economics in Washington . . . is threatened. The Institute lives off a yearly grant of $150,000.00 which the Carnegie Corporation of New York awarded for ten years. In the next few days the Carnegie Corporation will decide whether this grant will be paid beyond 1932. In the heart of the Corporation strong opposition has risen. The leader of the opposition is [Russell] Leffingwell, a member of the Morgan firm, who has for a long time been angry at the publications of the Institute, especially the books over Germany and France, because they depict the economic situation of these lands skeptically, and therefore influence the prospects for the bringing of the loans to these lands on the American market. It is clear that Leffingwell as a banker doesn’t like such books. Also, [Garrard] Winston from the Treasury Department who in previous years had been friendly to the Institute is said in the most recent days to have turned and labeled the publications of the Institute “simple propaganda.”

Whether under these circumstances the plan of the Institute to write a new book on Germany and [the] Dawes plan can be carried out, or whether [Harold] Moulton [the Institute’s head], who now fears the anger of the bankers, can find the courage to publish such a book is questionable.72

As the presidential election of 1928 loomed, all sides organized. The DuPont Co., for example, bought more than two dozen memberships for its top officials in the American Protective Tariff League, which had until then been declining.73 The Chemical Foundation repeatedly sought to dissuade financiers from making additional foreign loans.

In early 1928 these conflicts came to a head. Anxious to secure support from leaders of the internationalist bloc, Secretary of Commerce Hoover sent emissaries to Thomas Lamont at the House of Morgan. While not as rousing as it might have been, Lamont’s response suggested that he and other internationalists might be open to persuasion:

The ground swell for Hoover seems to be rolling up. Within the last two weeks, Hoover sent first Norman Davis [a close associate of Lamont’s and formerly Woodrow Wilson’s undersecretary of state], then Julius Barnes to me, complaining that our partners—he mentioned you as a former one, and Tom Cochran—had been working against him and for Dawes [who later dropped out]. Barnes wanted to know what our real attitude was. I told him that there was no attitude as attaching to the firm in the whole matter. Each member of the firm, Republican or Democrat, as the case might be, had his own particular preferences. I said that we had always felt very friendly here toward Hoover. . . . I said that if Hoover were the nominee of the Republican Party we should all expect to support him loyally. With this Barnes expressed himself as very well satisfied and said that what he feared was that even if Hoover were the nominee the prejudice of some members here against him was so great as to lead them to work against him. I reassured him on that point.74

A tense and complex process of accommodation now began between Hoover and most of the multinational bloc. First, Wall Street lawyer John Foster Dulles, Lamont’s old associate at the Versailles Conference and (because he was widely recognized as the leading American expert on Germany) already deeply involved in the advance planning for what eventually became the “Young Plan” revision of the older Dawes Agreement, crossed party lines—Dulles had backed Democratic candidate John W. Davis in 1924—and jumped aboard Hoover’s bandwagon.75 Warning German newspaper correspondents about the sensitivity of German reconstruction questions, Dulles quickly emerged as an important Hoover adviser. As Dulles joined his campaign, Hoover called a conference attended by representatives of most of the major American chemical companies, in part to discuss American policy toward I. G. Farben. Then he left town while a top operative in his preconvention campaign, Assistant Attorney General William (“Wild Bill”) Donovan, addressed the group. Basing his decision in part on material supplied by I. G. Farben (through the German embassy), Donovan announced that the I. G.’s practices did not violate American antitrust laws.76

Almost simultaneously, long-running negotiations to divide parts of the world market for various products between DuPont, I G. Farben, Britain’s ICI, Allied, and other big chemical companies stalled. So did other talks aimed at wider agreements between DuPont, I. G. Farben, and ICI. Standard Oil of New Jersey formed its notorious “cartel” with I. G. and, together with the National City Bank and others, began preparing to establish American-I. G. Farben.77