Monetary Policy, Loan Liquidation, and Industrial Conflict: The Federal Reserve and the Open Market Operations of 1932

GERALD EPSTEIN AND THOMAS FERGUSON

. . . in the United States the fear of the Member Banks lest they should be unable to cover their expenses is an obstacle to the adoption of a wholehearted cheap money policy.

J. M. Keynes, September 19321

IN THE SUMMER of 1929, output and employment in the American economy began falling. After the stock market crashed in late October, the decline turned into a catastrophic rout. By mid-1930, the United States, along with many other countries, was clearly sliding into deep depression. Yet the Federal Reserve System, widely trumpeted in the 1920s as the final guarantor of financial stability, did very little to offset what soon developed into the greatest deflation in American history.

For two long years the Fed maintained its posture of Jovian indifference. On occasion the New York Fed promoted very modest increases in liquidity; discount rates were lowered and flurries of open market purchases occurred, but nothing more.

In the spring of 1932, however, the Fed abruptly came to life. Following passage of a new banking law, the Glass-Steagall Act of 1932, which liberalized collateral requirements for Federal Reserve notes, the Fed seemed poised for a dramatic effort to break the deflationary cycle.2 As one eyewitness, who enjoyed special access to top Fed officials during this period, recalled many years later:

The Federal Reserve Bank’s experts, meanwhile, attempted their own cure by monetary controls aimed at expanding the supply of money. The strategy of “open market” purchasing of bonds by the Federal Reserve Banks had been used earlier; but now it was employed on a gigantic scale by [New York Fed Governor George L.] Harrison, who headed the Open Market Committee for the country’s twelve Reserve Banks. Under the new banking rules, he had one billion dollars more in gold available. With these funds he began to buy $100 million in U.S. government bonds every week during ten successive weeks up to May, 1932, by which date a hoard of $1.1 billion in bonds was accumulated. These transactions, of a size unequalled in the history of any central bank, put cash in the hands of the Reserve’s member banks and were expected to form the basis for the expansion of loans or investment in the ratio of 10 to 1.3

But the campaign ended almost as quickly as it began. In the summer of 1932, the Fed effectively abandoned the new policy. A few months later, like millions of other Americans, Herbert Hoover lost his house. Soon thereafter another wave of bank failures began. Eventually the entire financial system of the United States collapsed completely.

Ever since those dark days, debates have raged over the Fed’s policies.4 Little of this new work, however, has analyzed the Federal Reserve System’s shortlived attempt in early 1932 to reflate the economy through open market operations. Yet, as we will demonstrate, a reconsideration of the Fed’s actions in the period raises searching questions about the most widely accepted explanations of the Fed’s behavior in the Depression. We highlight the potentially disastrous consequences of one of the Fed’s most basic structural characteristics: its dual responsibility for both the health of the member banks and the welfare of the economy as a whole.

THE ROLE OF THE FED: PREVIOUS VIEWS

Among the recent works addressing the question of what the Fed thought it was doing are those by Friedman and Schwartz; Wicker; and Brunner and Meltzer. Their accounts of the 1932 episode can be compared by contrasting the answers each provides to three questions. Why did the Fed wait so long to begin its reflation program? Why did the campaign begin when it did, in early 1932? Why was the effort hastily abandoned the following summer?

Friedman and Schwartz offer explicit answers to each of these queries. Three reasons, they believe, explain why the Fed was reluctant to move against the Depression before 1932. The first is the untimely death in 1929 of the Fed’s dominating personality, New York Federal Reserve Bank Governor Benjamin Strong. What made his demise so significant were the other two factors Friedman and Schwartz stress: the Fed’s weak, decentralized organizational structure and the absence within the Federal Reserve System (save for the New York Fed) of a broad “national” point of view. “Parochial” and “jealous of New York,” the regional banks were “predisposed to question what New York proposed.” Their reluctance to cooperate increased turmoil in the Fed and made bold action impossible.5

Flatly denying that most Fed officials harbored any desires to reflate on their own, Friedman and Schwartz argue that pressure from Congress explains the timing of the open market operations of 1932. The close of the congressional session, they suggest, freed the Fed from these pressures and accounted for the tapering off of the program in the summer of 1932.

Wicker’s account is less clearcut. In different parts of his work he mentions various factors, including a failure by most of the Fed’s directors and officials “to understand how open market operations could be used to counteract recessions and depressions,” and a concentration on short-term rates “to the neglect of member bank reserves and the money supply.”6 Unlike Friedman and Schwartz, who downplay international considerations, Wicker refers frequently to the Fed’s anxiety about the international gold standard and, at least occasionally, free gold. Although Wicker does not focus on what caused the Fed to begin the open market operations, he is clear on why the Fed abandoned them: Fed officials misinterpreted the meaning of the accumulation of excess reserves, and considered monetary policy easy.7

Brunner and Meltzer do not specifically discuss the 1932 reflation and, as discussed below, large-scale open market purchases are precisely what their theory of Fed behavior does not predict. But if their account thus affords no answer to the second of our three questions (why the open market operations began), it is easy to reconstruct implicit answers to the other two questions from their general account of the Fed in this period. Their discussion focuses on the latter point mentioned by Wicker, the misinterpretation of excess reserves and short-term rates. They argue that the severe deflation of the early 1930s made nominal interest rates unusually poor guides to real interest rates.8 With severe deflation, low nominal rates represented a comparatively high real rate. During much of the Depression, and particularly in the summer of 1932 when nominal rates were quite low, the Fed may simply have misinterpreted conditions in the money market; it believed real rates were low, when they in fact were high.

Brunner and Meltzer also argue that the reigning Fed doctrine on open market operations, referred to as the “Riefler-Burgess-Strong framework,” led the Fed astray. The doctrine, they assert, not only failed to distinguish nominal from real rates, but also upheld the “real bills” theory, according to which bank lending for actual trade (real bills) represented the only acceptable asset for rediscount by central banks.9

Each of these accounts clarifies vital points. But we cannot accept any of them as definitive. For example, all place heavy weight on policy errors, mistaken theories, and, in the case of Friedman and Schwartz, and Wicker, personalities. Yet, not only the Fed, but virtually all other central banks failed to move vigorously against the Depression.10 How far can one press an argument that a deceased Benjamin Strong was responsible for all of this?

The assumptions and claims in the literature about targets and indicators relied upon by the Fed during this period are also problematic. The claim of Brunner and Meltzer, and Wicker that the Fed did not understand the difference between real and nominal rates relies on an implication that is difficult to believe: that bankers were unable to see that real interest rates were high but that the industrialists, who joined them on the boards of the Federal Reserve banks, were. (That is why they did not borrow, according to the argument.) References to the real-nominal distinction among top bankers, economists, and leading members of the Federal Reserve System were also far more common than the work of Brunner and Meltzer suggests. Material in the Fed’s archives indicates that, at least in the 1930s, neither Burgess nor Riefler subscribed to the doctrines bearing their names.11

Direct evidence of a relationship between real bills and Fed behavior is also weak. Our own statistical tests failed to confirm earlier views of the influence of short-term interest rates on Fed policy, while a continuation of Meltzer’s own table relating changes in the gold stock, member bank borrowing, and interest rates on three-month to six-month notes to Fed decisions on open market operations past his mid-1931 cutoff point shows that the Fed repeatedly ignored the signals sent by member bank borrowing.12

Friedman and Schwartz’s account of the making of monetary policy in this period raises other questions. It emphasizes domestic concerns and underestimates the role international economic considerations, especially a concern for protection of the gold stock and maintenance of the gold standard, played in the making of policy throughout most of the period of 1929 to 1932. As we will explain below, although Friedman and Schwartz are correct in claiming the passage of the Glass-Steagall Act of early 1932 temporarily alleviated the free gold problem for the Federal Reserve System as a whole, they are mistaken in dismissing both gold and the international economy as constraints thereafter.

To see how the international economy affected Fed policy after the Glass-Steagall Act of 1932, however, it is necessary to break with the tradition of analyzing the Fed’s actions in terms of their effects on broad categories, such as the total gold stock, the balance of payments, or the national income. One must look in detail at the microeconomics of the banking sector to identify how various actions of the Fed potentially affected bank profitability at different points in time. If, following Stigler, Posner, and other recent analysts of the symbiosis of regulator and regulated, one gathers evidence on the policy preferences of private bankers and their interaction with the regulators, we find a ready answer to our three central questions about the Fed’s open market program of 1932.13

WHY DID THE FED WAIT SO LONG?

Our principle concern is the behavior of the Federal Reserve System between January and July 1932, and thus we concentrate on answering the last two of the three questions. Responding to the first query, why the Fed waited so long to act, however, requires a glance backward at Fed policy in earlier stages of the Great Contraction.

Between October 1929 and April 1931, industrial production fell by 26 percent, while the monetary base declined by 90 million dollars. In the period it is clear that the Fed did not pursue an activist policy to revive the economy, but some differences occasionally developed in the approaches various reserve banks took to manage the deflation.

Immediately after the stock market crash, for example, the New York Fed purchased $160 million of government securities and encouraged the New York banks to discount freely. During the next year and a half, the New York Fed pressed for reductions in discount and acceptance rates. Opposition from the board of governors and the other reserve banks, however, generally delayed or reduced the impact of these measures.14

But, if the New York Fed generally favored easier money than the rest of the Federal Reserve System, it did not advocate large-scale reflation. New York Fed Governor Harrison’s report of the open market policy conference to the governor’s conference on April 27, 1931, for example, clearly repudiated the notion of an active countercyclical policy.15

Why was the New York Fed more expansionary than other reserve banks, and why did no one seriously try to revive business? The answer to the first question surely relates to the important connection between the New York commercial banks and the stock market (or perhaps, the banker directors of the New York Fed, many of whom were later shown to have been in some distress in this period).16

The reasons for the lack of interest in more expansionary policies are more interesting and can be pieced together from primary sources and our statistical investigation, Archival sources make a point which is obvious in retrospect, but which later accounts do not take seriously enough: Conventional doctrine among businessmen, bankers, and economists in the period held that occasional depressions (or deflations) were vital to the long-run health of a capitalist economy. Accordingly, the task of central banking was to stand back and allow nature’s therapy to take its course. As one well-known voting member of the Fed’s board of governors, Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon, expressed it, the way out of a depression consisted of a sustained effort to “liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate.”17 In private discussions among bankers, economists, and Fed officials, the need to compel liquidation was a common topic of conversation. Reasons given included correcting the mistakes of businessmen, curbing the excessive spending of governments, and especially, reducing the wages of labor.18

Among industrialists and high government officials, faith that wage reductions would eventually revive prosperity was less strong than among bankers. After the stock market crash, for example, President Hoover made several highly publicized efforts to promote work sharing and discourage wage cuts. His efforts were backed strongly by a number of major industrialists in predominantly capital-intensive industries, including the heads of Standard Oil of New Jersey and AT&T. In the end, however, the campaign did not amount to much. Petering out as the Depression grew worse, it failed to move the Fed.19

Their inability to move the Fed led the industrialists either to give up and join the bankers in calls for wage reductions or to influence Congress in favor of legislated directives for monetary expansion. Hoover, who left to himself would probably have moved more vigorously against the Depression than has been presumed, in practice gave in to pressures from the banks, especially J. P. Morgan & Co., and the Treasury.20

Though Friedman and Schwartz argue that in the period free gold and the gold standard were not major concerns of the Federal Reserve Board, we believe they are mistaken. Their narrative, for example, alludes to a memorandum from a January 1931 meeting of the Federal Reserve Board. Yet at the conference, many participants were deeply concerned with gold. Fed economist E. A. Goldenweiser, for example, reports that “There was a good deal of discussion about free gold. Anderson had made a statement that free gold was down to $600,000,000, and we were, therefore, nearer to the time when credit policy would have to be guided by the availability of gold.” To which A. C. Miller of the Federal Reserve Board bluntly replied that “purchases of securities by diminishing free gold are a dangerous procedure.”21

Although convertibility remained axiomatic to everyone in the banking system, real bills did not. Some top Fed officials seem to have subscribed to this doctrine.22 But many Fed officials and bankers (especially in New York) actively promoted the removal of the extra constraints on free gold imposed by existing limitations on the definition of the “eligible paper” acceptable as backing for Federal Reserve notes. Goldenweiser observed to the Federal Reserve Board in early January 1930, “My own view is that collateral provisions are obsolete and unnecessary.”23 His statement counts heavily against Brunner and Meltzer’s argument on the importance of the real bills doctrine as an explanation of Fed behavior. The collateral provisions associated with the definition of free gold were one of the major embodiments of the real bills doctrine in the Federal Reserve System.

The desire to force wages down, intermittent anxiety about gold, and (to a lesser extent) the belief of some in real bills, probably account for most of the Fed’s inactivity until the fall of 1931.24 An event then occurred which explains the Fed’s inaction throughout the rest of 1931 and the timing of its belated reflation efforts in early 1932. That event was the British abandonment of the gold standard in September 1931.

THE DECISION TO REFLATE

Friedman and Schwartz, who deemphasize international factors in their account, agree that the desire to remain on gold controlled Fed policy in the next few months. The run on the dollar that followed Britain’s announcement that it was leaving gold resulted in a heavy gold loss for the United States. From September 16 to September 30, 1931, the U.S. gold stock declined by $275 million. In October it decreased by an additional $450 million. The losses just about offset the net influx during the preceding two years.25

For a brief time Harrison and the New York Fed hoped to avoid a sharp rise in the discount rate, but experience in the first few weeks persuaded everyone in the Federal Reserve System that the time had arrived to apply the classic remedy for halting a run on gold. In two weeks the Fed raised the rate by 2 percentage points, the sharpest rise in such a brief period in the Fed’s history. It also halted all expansionary open market operations.

The benefits of this policy were predictable: The run on the dollar halted; gold outflows ceased and then began to reverse. But its costs were no less obvious and foreseeable: There were massive new waves of deflation, business bankruptcies, and bank failures.

The chorus of voices demanding reflation swelled, and calls for public works expenditures, veterans’ benefits, government-sponsored cartelization of industry, and other forms of market intervention proliferated. As Friedman and Schwartz suggest, many of the new pressures found expression in Congress, where bills mandating various forms of monetary expansion, including one coauthored by Irving Fisher, were introduced.26

All the tumult certainly worried the Fed and the banking community at large. The banks, however, had major worries of their own. The rise in the discount rate sent bond prices plunging, even triple-A bonds. The collapse of bond prices threatened the solvency of many banks.27

With many large banks facing the potential of trouble, many leading bankers joined veterans, industrialists, and farmers in calling upon the Fed for action. A few financiers, including several Morgan partners, advocated expansionary monetary policies explicitly for macroeconomic reasons.28 Most bankers, however, appear to have been dubious or uncomprehending about the macroeconomic case for reflation. But at this juncture it hardly mattered, for with runs on banks, hoarding, and other threats to deposits developing, most banks had a desperate need for action by the Federal Reserve to revive the almost defunct bond market and to restore liquidity.29

Unable for several months to do anything with monetary policy (because their sovereign commitment to gold left them no choice but to support discount rate increases), leading bankers began consultations with Hoover’s Treasury Secretary Ogden Mills (who had replaced Andrew Mellon), Fed Chairman Eugene Meyer, and other top officials. Led by Thomas W. Lamont of J. P. Morgan & Co., they evolved a plan for a private “National Credit Corporation.” The NCC, however, had one drawback: It was “National” in name only. Actually, it functioned as a bank bailout fund, operating on capital privately supplied by leading bankers, which exposed them to possible losses. As soon as the run on gold abated in the last couple of months of 1931, Lamont, other private bankers, Hoover, Mills, and high Fed officials gradually evolved new and different plans.30

The new program was represented to the open market policy conference in early January 1932. Standard accounts of the Fed in this period accurately present five of the six points in the plan “to stop deflation and encourage some credit increase.” These five are: (1) passage of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, (2) Federal Reserve and member bank cooperation with the Treasury program, (3) the buying of bills when possible, (4) the reduction of discount rates, and (5) the purchase of governments. The remaining point is usually reported as “support for the bond market.” In the minutes it reads “organized support for the bond market predicated upon railroad wage cuts.”31

Thus a major goal of the program was to revive railroad bond values, of which major New York banks held $200 million, comprising a third of their private bond portfolios in December 1931, and bond prices in general. Private bankers and the Federal Reserve saw wage cuts as a necessary condition to reviving those values. By reviving the bond market the Federal Reserve hoped to regenerate the savings and investment process and revive the banks.

Another component of the program, hidden in the January minutes, appears in a memorandum from W. Randolph Burgess to Harrison: “most of the points of our January program have now been achieved: rail wages have been reduced, the administration had made a definite commitment on balancing the budget, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation is in operation, and the bond pool has been operating—though feebly. Everybody else has done the tasks assigned to him, but the reserve system. . . .” Burgess adds, “there was a very good reason for not doing so, and that was the limited amount of our free gold in the face of European gold withdrawals.”32

Though Friedman and Schwartz discount it, Fed memoranda during the period show that free gold did handicap the Federal Reserve System for several months. After massive lobbying by the Fed and private bankers, however, Congress passed the Glass-Steagall Act.33 The new law permitted government securities to be used as backing for Federal Reserve notes, thus freeing additional gold for export.

Keeping careful watch on critical variables (the gold stock, excess reserves, free gold, foreign balances, and bank suspensions), the Fed commenced open market operations.34 In a memorandum prepared for an April 5 meeting of the executive committee and the board of governors, Harrison reported that “the program . . . has been even more successful than could well have been hoped for at that time, as member bank indebtedness has been reduced by more than $200,000,000.”35

At that meeting, Harrison “reviewed the current economic situation, the continued decline in prices, the increase in the pressure of debts, the increase in bankruptcies, and the threat of radical action in Congress. . . . After extended discussion of these questions it was moved and carried that purchases of government securities be continued at a rate of $25,000,000 a week.36 The mention of “the increase in the pressure of debts” after “the continued decline in prices” suggests that, contrary to Brunner and Meltzer, Harrison was aware of the effects of falling prices on the real value of debt. Harrison’s allusion to congressional pressure also confirms Friedman and Schwartz’s suggestion that this factor was a concern at the Fed. But the reference also sets this factor in its proper context as but one among several figuring in the decision to reflate.

At an April 12 meeting, Treasury Secretary Mills, Fed Chairman Meyer, Miller of the board, and Harrison urged the Fed’s Board of Governors to approve a major increase in the scale of open market purchases. Mills asserted that “[f]or a great central banking system to stand by with a 70% gold reserve without taking active steps in such a situation was almost inconceivable and almost unforgiveable.” Harrison explained the delay in moving toward an expansion program after the passage of the Glass-Steagall Act as the effect of “[t]he uncertainty as to the budget and bonus legislation [which] had constituted obstacles to inaugurating such a program, but he believed that the outlook in these directions was hopeful, and that it would not be possible or necessary to wait until these questions were completely solved.”37

THE PROGRAM ABANDONED

By this time, however, serious opposition to the program had surfaced among the reserve banks and on the board of governors. Governor J. B. McDougal of Chicago had strongly opposed it virtually from the beginning. In this pre–New Deal period, when authority for open market purchases was not as yet vested firmly in the board of governors, McDougal’s opposition was very important, for his bank was, with the exception of New York, the most important in terms of its influence within the Federal Reserve System and in terms of the number of securities it could buy.38 Often, however, Governor Roy Young of the much smaller Boston bank supported him, at least to the extent of speaking against the program before committing his bank to participating.39

At the April 12 meeting McDougal and Young questioned the program again, and a revealing exchange with Harrison occurred. Objecting that as the program continued, reserves would pile up in reserve centers, Young allowed that “he was skeptical of getting the cooperation of the banks . . . and was apprehensive that a program of this sort would develop the animosity of many bankers.” Harrison replied, most meaningfully, that in “the present situation the banks were much more interested in avoiding possible losses than in augmenting their current income, and that their attitude had changed gradually since last year in the face of the shrinkage in values.”40

This exchange between governors provides one of the first clear hints of the importance of one of the three major factors that eventually led to the abandonment of the whole program. We call it the “loan liquidation effect.”

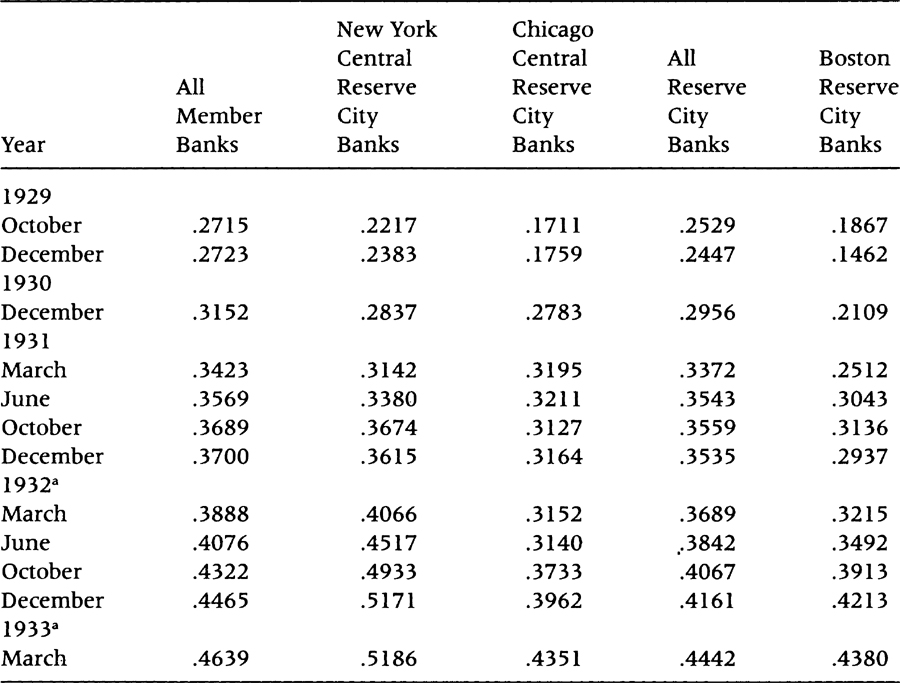

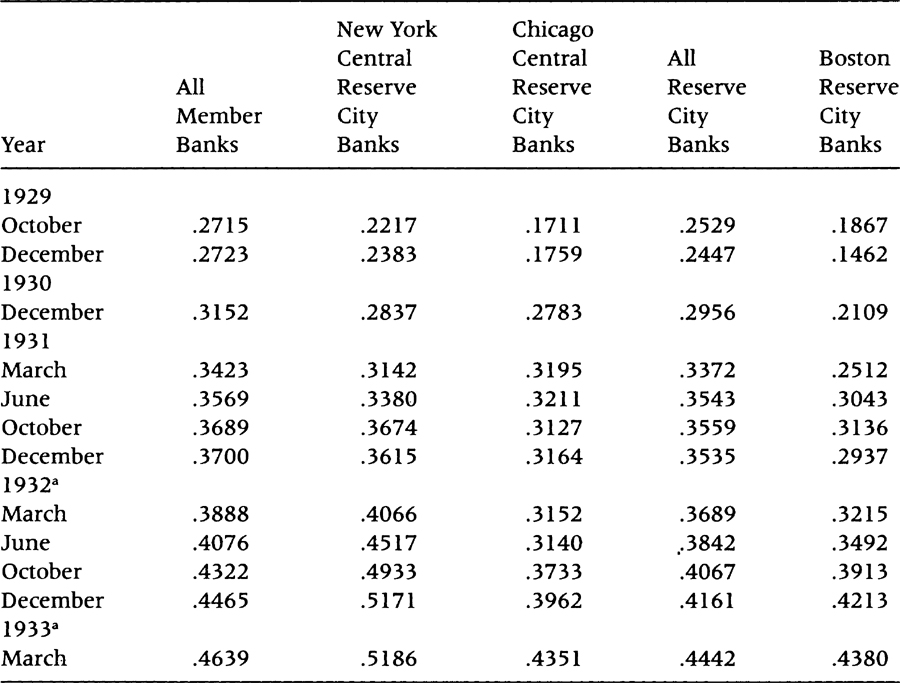

By the middle of the Great Contraction, bank portfolios in many Federal Reserve districts were beginning to assume a curious shape. Either because bankers were becoming very wary or because good lending opportunities were difficult to find, loans were falling off catastrophically. The loan liquidation effect then took hold. As loans and many bonds became increasingly risky, bankers looked around for ways to maintain earnings. In due course, they began to purchase larger and larger amounts of the safest asset that remained available in large quantities—short-term government securities. Tables 3.1 and 3.2 indicate the dimensions of this change. Whereas in 1929 investments made up less than 30 percent of member bank earning asset portfolios, by the end of 1933 they made up almost 50 percent (see table 3.1). A large percentage of the increase took the form of increases in holdings of government securities.

TABLE 3.1. Ratio of Investments to Loans and Investments For Selected Member Banks

Source: Board of Governors of the United States Federal Reserve System, Banking and Monetary Statistics (Washington, D.C., 1943), pp. 72, 74, 80, 86, 92, 696.

aCall dates except for March 1932, 1933, which are linear interpolations since there were no call reports for those dates.

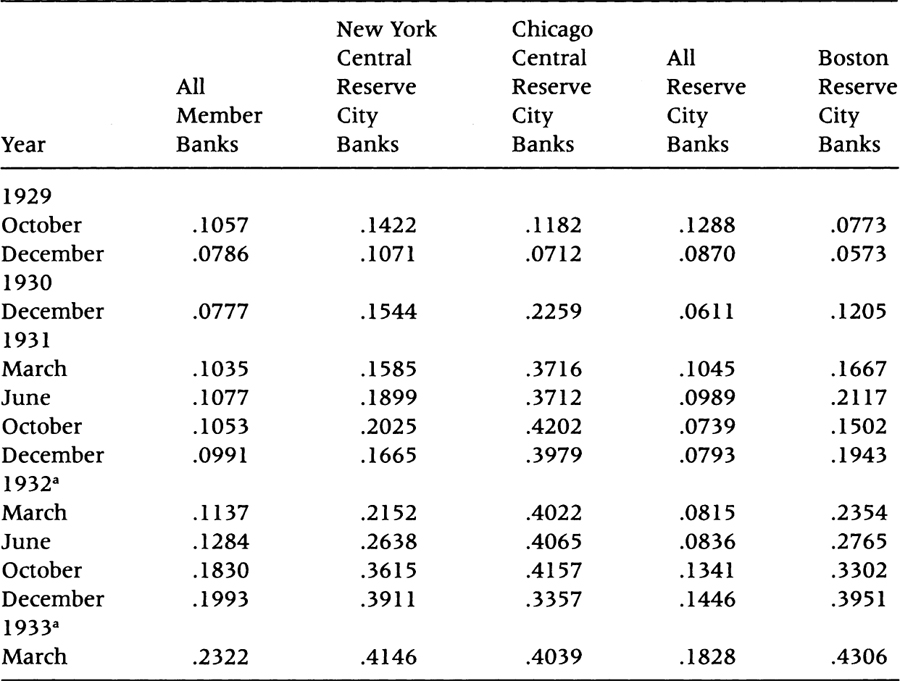

TABLE 3.2. Ratio of Bills and Notes to Total Investments For Selected Member Banks

Source: Board of Governors of the United States Federal Reserve System, Banking and Monetary Statistics (Washington, D.C., 1943), pp. 77, 84, 90, 96, 700.

aCall dates except for March 1932, 1933, which are linear interpolations since there were no call reports for those dates.

These shifts had important consequences for bank earnings. The net return on investments tended to be lower than that on loans.41 In addition, table 3.2 indicates the banks, especially the reserve city banks, bought a sharply rising percentage of short-term securities.

With expansionary open market operations and reductions in nominal income moving short-term rates to extremely low levels (rates on three-month to six-month Treasury notes and certificates plunged from 3.4 percent in November of 1929 to 0.34 percent in June of 1932), a squeeze on bank earnings developed.42 Unable to obtain capital gains because of the shortness of their portfolios, banks had to face diminished earnings as they turned over portfolios and as rates on short-term governments fell.

Of course, rate reductions would not have impaired current earnings if rates on the money banks borrowed and other expenses had fallen just as rapidly. But while rates on borrowed money did decline, there were pitfalls here. In 1932, banks still paid interest on demand deposits. As rates paid approached zero, it would become increasingly difficult to hold deposits, especially if a run materialized.43 Even worse, the banks still had to pay expenses, and these, especially payments for salaries and wages and “other expenses” (which included fees for directors and advisory committees), failed to decline as much as earnings in 1932 (and several other years). Accordingly, net earnings, before losses, fell more or less steadily after 1929. But earnings after losses on loans and securities plunged steeply in 1932 and 1933, leading to –$0.89 and –$1.42 in net profits per $100 of loans and investments in 1932 and 1933.44

These developments led to growing opposition to the open market campaign in a straightforward manner. Although loan liquidation ultimately spread to banks in all Federal Reserve districts, some districts were hit much harder than others in 1932. Banks that stood to lose the most from declining rates were those with a relatively high percentage of short-term debt in their portfolios. Table 3.2 indicates that Chicago’s central reserve city banks, the city’s larger banks, had a much higher proportion of bills and notes in their portfolios than all member banks or all other reserve city banks, and that Boston’s reserve city banks were adding short-term governments to their portfolios at a breakneck pace between October 1931 and June 1932. (Note that Chicago central reserve city banks had double the percentage of bills and notes than those in New York through 1931, with New York catching up only in the last quarter of 1932 after the open market purchases were abandoned; while between October and December 1931, reserve city banks in Boston and central reserve city banks in New York changed the composition of their portfolios in virtually opposite directions.)

These portfolio changes had important consequences for net earnings of member banks by Federal Reserve district. Since earnings on the overall portfolios reflected the interest rates on assets accumulated in previous months, current security rates would have their major effects on portfolio earnings some months after they were purchased. So, for example, returns in December of 1932 would reflect the interest rates on securities purchased in the summer of 1932. There were great reductions in net earnings facing banks in the Chicago district in the half-year ending December 1932, reflecting the earlier decline in interest rates. Their net margin (earnings per $100 of loans and investments) fell to $0.23 from $0.43 in the period six months earlier, which translates into a substantial drop in total profits. New York bank earnings margins, on the other hand, still held up comparatively well even at this late date, falling only from $0.62 to $0.54. The rates for other districts (generally of less significance within the system than Chicago or New York) were scattered.45

That the governors of the Boston Fed and, especially, the Chicago Fed should be early critics of the reflation program is therefore no mystery.

Opposition on the other grounds was soon registered in minutes and memoranda. A memo on open market purchases, April 5, 1932, reported that between March 2 and April 6, the Fed had bought $130 million of securities. But only four reserve banks participated in the open market purchase program directly. Moreover, the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City had discontinued its participation on March 23, “owing to its free gold position.”46

This reference points to a second reason for the eventual termination of the program, what might be termed the growing problem of “gold distribution.” As Friedman and Schwartz emphasize, especially after the passage of the Glass-Steagall Act, both the Federal Reserve as a whole and the New York Fed had more than enough gold to meet any conceivable run. But Federal Reserve banks in each district still had to maintain a 40 percent gold cover for their notes. And here an acute problem began shaping up. The Federal Reserve was, after all, only a federal reserve. A series of unresolved controversies in the 1920s had led to debates about the Federal Reserve Board’s legal authority over individual reserve banks. Though it is difficult to be sure, since the issue eventually was settled not in court but by New Deal banking legislation, it is doubtful that individual reserve banks would have surrendered their gold without struggle. (Indeed, under far graver conditions a year later, the Chicago Fed flatly refused the New York Fed’s desperate request for emergency rediscounting assistance and made the refusal stick.)47

As a consequence, not only the total amount of gold but its distribution among the Federal Reserve banks became important. As individual banks lost gold and approached the legal limit for their gold cover, they would have to stop participation in the reflation program. Over the next few months this happened: Not only Kansas City but other reserve banks became more and more nervous about running out of their gold. As their nervousness increased, they stopped supporting reflation.48

The last of the three major factors which induced the Fed to abandon its open market program also concerned gold. Like the question of distribution, however, it has not figured significantly in the literature. The problem, at its starkest, was this: At the time the open market program began, foreign balances held by American institutions amounted to more than $1.2 billion. These sums were not distributed evenly throughout the system’s districts, but were heavily concentrated in New York (with, probably, lesser amounts in Boston and one or two other reserve centers).49 Difficulty arose because the French (and toward the end, British and other interests) withdrew large sums, and the British threatened to withdraw still more. That the Federal Reserve System as a whole had reserves that more than covered the foreign deposits was all very well. To the big New York banks, however, this was academic. It was their deposits that were leaving, to the detriment of their earnings and safety.

In a theoretically perfect world, of course, the deposit loss might have been neutralized by continued open market operations. But America in 1932 was not a theoretically perfect world. First of all, for reasons already discussed, the whole open market program was acutely controversial. No New York bank could be sure how long it would continue or what the purchases would amount to. In addition, the magnitude of foreign deposits involved was large—almost equal to the projected total of open market purchases for the system as a whole. There was also the possibility that Americans would look at the foreign withdrawals and themselves begin fleeing from the dollar, especially as the battle over the budget climaxed.

From the beginning of the open market program, private bankers and Fed officials sought ways to minimize losses of foreign gold. It is uncertain whether Prime Minister Pierre Laval pledged to maintain French deposits when he visited the United States in the fall of 1931, but, in any case, the Banque de France soon compelled the Fed to agree to their withdrawal. With the faint hope of persuading the French to change their minds. Thomas Lamont of J. P. Morgan & Co. made a special trip to France in the early spring. For a while, Lamont and other bankers believed these efforts might succeed. But events gradually proved them mistaken. Encouraged by a series of widely discussed articles by H. Parker Willis, an economist well known for monetary orthodoxy that criticized the Fed’s program as “inflationary,” the Banque de France and other foreign interests continued withdrawing deposits from the Fed and other banks.50

Though Fed officials and bankers worried privately about the lost deposits, for a while the losses were bearable. The French withdrew most of their deposits, but under Harrison’s leadership the Fed continued with the program. In late spring, however, the British threatened to emulate the French.

As early as March, the Bank of England had indicated that it did not want to let sterling appreciate in response to an expansionary program in the United States. At that time, however, the Bank of England was pursuing a modest “cheap money” policy of its own (with the enthusiastic support of the British Treasury, which urged the Bank of England to proceed even more vigorously.)51 With sterling declining about as much as the dollar, there was no necessary conflict between the policies of the two central banks for several months. But while little overt conflict existed, concern on both sides led the two central banks and the Morgan bank to begin a round of discussions.

As they negotiated, influential New York bankers, including Morgan partners who supported monetary expansion, complained about their lost foreign deposits:

loans and deposits of the New York banks have fallen almost perpendicularly. . . . The loss of French and other foreign deposits, particularly since sterling went off gold, has fallen principally upon New York. Not only actual withdrawals of balances from America to abroad, but transfers of balances from banks to the Federal Reserve Bank have taken place. This loss of deposits has forced the New York banks to realize on assets.

I question whether the Federal Reserve Banks’ liberal purchases of bills and governments have even so much as kept step with the member banks’ losses in deposits and stillhaltungs [sic]. Such purchases cannot begin to have an affirmative effect on the general price level until they have exceeded the amount of the frozen credits and withdrawn deposits.52

In late spring the Bank of England (though not the British Treasury) became concerned that sterling would drop too far. By May 26, the New York Fed was receiving cables that the Bank of England was selling dollars.53 Pressure on the dollar mounted. Whereas French deposits in New York banks had been falling for a number of months, British funds plunged between May and August by over a third. Withdrawals of the remaining French deposits also accelerated.

The continued loss of gold and deposits put many New York banks in an increasingly uncomfortable position. As the difficulties associated with the pursuit of an independent monetary policy in a context of international capital mobility and a managed exchange rate were expressed in their balance sheets and income statements, the banks were faced with a dilemma. If interest rates rose, they would encounter losses on their bond portfolios that might lead to bank runs and insolvency. If interest rates fell, foreigners would withdraw deposits, forcing the banks to liquidate bonds and therefore realize losses on their bond portfolios due to the inelasticity of demand for bonds at the time of the forced sale.

Not surprisingly, the New York financial community began sending mixed signals. Many complained that the reflation program had “demoralized money and exchange markets.”54

Adding to the turmoil was the climax of the long-running battle over the national budget in early June. Harrison believed that the gold outflow would slow down once France removed its gold. But that did not prevent him from joining with leading businessmen in using the preservation of the gold standard as an argument in an ultimately successful fight for a sales tax and a balanced budget and against the reflation bills being debated in Congress.55

For these reasons—the loan liquidation effect, the problems of gold distribution with the Federal Reserve System, and the problem of withdrawal of foreign balances—opposition to “inflation” intensified within the Fed and among bankers in the early summer. At various meetings complaints were voiced above the slowness with which monetary policy seemed to be working. Extensive discussion about the need to find borrowers and to coordinate investments and loan applications took place. Private bankers, Fed officials, and prominent industrialists laid plans for officially sponsored “banking and industrial committees.” Rather clear evidence that the proponents of monetary expansion were losing strength, these committees were shortly announced with a great flurry of public attention.56

In June, just as optimistic Fed staffers and some private experts were announcing that the worst of the gold crisis had passed, the Bank of England asked the Fed to earmark more gold. Discussions between the Bank of England and the Fed continued into July; there are indications that these concerned sterling/dollar exchange rates. In any event, various Fed minutes and official documents refer quite explicitly to the anxiety felt in the New York district about the loss of foreign deposits (which now totaled almost half a billion dollars, since the first of the year—half the size of the reflation program for the system as a whole).57

At the June 16 meeting of the executive committee of the open market policy conference, even Harrison declined to press for increases in the open market program. Something had changed. He suggested the Fed aim to “. . . maintain the excess reserves of member banks at a figure somewhere between $250,000,000 and $300,000,000 until there was some expansion of credit which would make it desirable to reconsider the program.”58 Harrison’s decision to place the target in these terms probably reflects the increasing difficulty in getting more expansionary policies passed as much as a desire to use excess reserves as a target. It probably does not reflect confusion over the role of excess reserves, as Wicker maintained. Support for this view is found in the same minutes where “it was pointed out that a number of the [Federal Reserve] banks were limited by relatively low reserve percentages from taking their full quota of participation in System purchases.”

At the beginning of July, the coup de grâce to the program came from Chicago (which was then recovering from a staggering wave of bank failures and where bank margins were being desperately squeezed). As McDougal bluntly wrote Harrison in a letter: “We are of the opinion that no additional purchases should be made by the system. . . . While purchases by the system for the purpose of offsetting gold exports were probably justified, we believe that the additional purchases made were much too large and have resulted in creating abnormally low rates for short-term government securities.”59

By the end of the month, open market operations were virtually stopped. At the July 14 meeting of the open market policy conference, “The Governors of a number of banks pointed out that with their reserve percentages not far from 50 percent their directors were reluctant to participate much further in open market purchases, particularly unless the operations were a united system undertaking.” Expressing hope that the banking and industrial committees would secure better results, the Fed and the bankers effectively abandoned the experiment as well as another privately financed bond pool announced in June.60

STATISTICAL TESTS

Our evidence thus far has been mainly archival, and statistical tests would provide further confirmation. An ideal test of our underlying hypothesis, that the Federal Reserve policy in the Great Contraction responded primarily to the needs of the larger banks, would relate Fed behavior to the profits of large banks, controlling for the influences of other relevant variables in the economy. This test, however, is very difficult to perform because of the existing bank profit data. Most published sources report only semiannual figures for all banks by Federal Reserve district.61 Several different kinds of statistical problems, requiring a variety of more or less plausible assumptions for their solution, must also be faced.62 Within these limits, however, it is possible to estimate the determinants of the Federal Reserve Board’s monetary policy to see whether statistical evidence supports our explanation of the 1932 open market operations.

Consider first the dependent variable. Most of our sources suggest that the policy variables usually manipulated by the Federal Reserve were the amount of securities bought plus the amount of bills bought in its open market operations. (The open market committee made decisions about security purchases while the New York Federal Reserve had more control over the amount of bills bought, which it could affect by altering the rate offered on bills.) The larger the amount of securities and bills bought (OMO), the more expansionary is the monetary policy.

Our analysis implies that several sets of independent variables are relevant. One involves various domestic influences on bank profits, and another reflects international constraints. A third group relates Federal Reserve reactions to pressure from industry, while a final set tests miscellaneous variables related to the structure of financial markets as well as other factors suggested in the literature.

The first “domestic” variables include, for example, real wages. The Fed wanted to reduce real wages, hoping that lower wages would help restore bond prices by reestablishing industrial profitability and lowering inflationary expectations. Thus, when real wages increased, the Fed should have reacted by tightening the money supply, giving an expected negative sign on the real wage variable, RWAGE.

When bond prices fall, our hypothesis is that monetary policy would become more expansionary. Triple-A corporate bond prices (CORP) are measured in absolute terms. Another variable to measure direct responses to bond prices is the difference between the long-term and short-term interest rates (DIFF). A widening difference might be a sign that the riskiness of long-term bonds was increasing, which would lead the Federal Reserve to attempt to expand the money supply to reduce the spread.

Archival evidence suggests that alterations in the portfolios of non–New York large banks from loans and long-term assets to short-term assets led these banks in 1932 to pressure the Federal Reserve to tighten monetary policy in order to raise their profit margins. To measure the loan liquidation effect on non–New York banks, we have constructed a measure, RATM, which is the ratio of loans and long-term assets to total assets of non–New York large banks. As RATM falls these banks should have put pressure on the Fed to tighten monetary policy, implying a positive influence of RATM on OMO.

International variables include free gold, foreign deposits, and currency sent abroad. Archival evidence indicates that the Federal Reserve was constrained by the availability of free gold, Friedman and Schwartz’s claims to the contrary. Free gold captures both the international and the domestic constraints imposed by the gold standard. The Federal Reserve was forced to maintain gold and collateral as backing for notes; even after Glass-Steagall, it still had to keep gold for cover. When the United States lost gold internationally the Fed was less willing to expand. If free gold was a constraint, then when more free gold became available, the Federal Reserve could more freely engage in open market operations. We have constructed a measure of free gold (FGOLD) which includes the freeing up of gold with the Glass-Steagall Act of 1932. We expect a positive coefficient on the FGOLD variable.

As U.S. banks lost foreign deposits, the Federal Reserve became concerned about the effects on bank liquidity and profits. This suggests that as foreign deposits fell, monetary policy would become tighter, in order to protect the deposits. Our proxy for “deposits” is foreign deposits held at the New York Federal Reserve Bank. As an earlier quotation from Russell Leffingwell indicates, deposits were being taken out of the New York commercial banks and placed in the New York Federal Reserve. This loss of deposits to the New York banks would not be picked up in our data. With this caveat, we would expect a positive coefficient on the foreign deposit variable (FB).

Our archival research also indicates that in crises the Federal Reserve was concerned that U.S. currency hoarded by American and foreign holders could be liquidated for gold or foreign assets. Data collected by the Fed on currency sent to and from abroad by New York banks can be used to estimate such occurrences. In crises currency tended to be sent to New York banks from abroad, apparently reflecting a previous hoarding of U.S. currency that was sent abroad and sold for foreign assets and gold; the currency then returned to New York banks for redemption.63 We expect the Federal Reserve to tighten monetary policy when the flow of currency from abroad to New York (CURAB) is positive, indicating a threat to U.S. gold reserves.

By January 1932 bankers and the Fed could not entirely ignore the effects of monetary policy on industry, if for no other reason than that industrial production affected loan demand and the profits of the banks. Thus, one might expect the Federal Reserve to conduct countercyclical monetary policy as suggested by Carl Snyder and other staff members of the New York Fed. This leads us to test for a third major type of independent variable, one that could be called “industrial,” based on the industrial production index (IP). Open market purchases by the Fed might be expected to increase when IP decreased.

Finally, Wicker, Brunner and Meltzer, and others have hypothesized that the Federal Reserve mistakenly used excess reserves as an indicator of monetary policy. When excess reserves were high, they argue, the Federal Reserve stopped expanding the money supply. This hypothesis would suggest that when excess reserves (EXRE) went up, the Federal Reserve contracted the money supply, implying a negative relationship between EXRE and OMO.

It might also be expected that, given the function of the Federal Reserve as a potential lender of last resort, the Fed might try to reduce bank failures. In this case, when there was an increase in failures (FAIL), monetary policy would become more expansionary.

The equations we estimate are in double log form and the coefficients are the elasticities. All independent variables have been lagged by one period, and the results have been corrected for first-order serial correlation by using the Corchrane-Orcutt technique. The time period, from February 1930 to February 1933, was chosen to avoid the effects of the stock market crash in October 1929 and the banking panic of March 1933. All data are monthly. Definitions and sources are given in appendix 3.1.

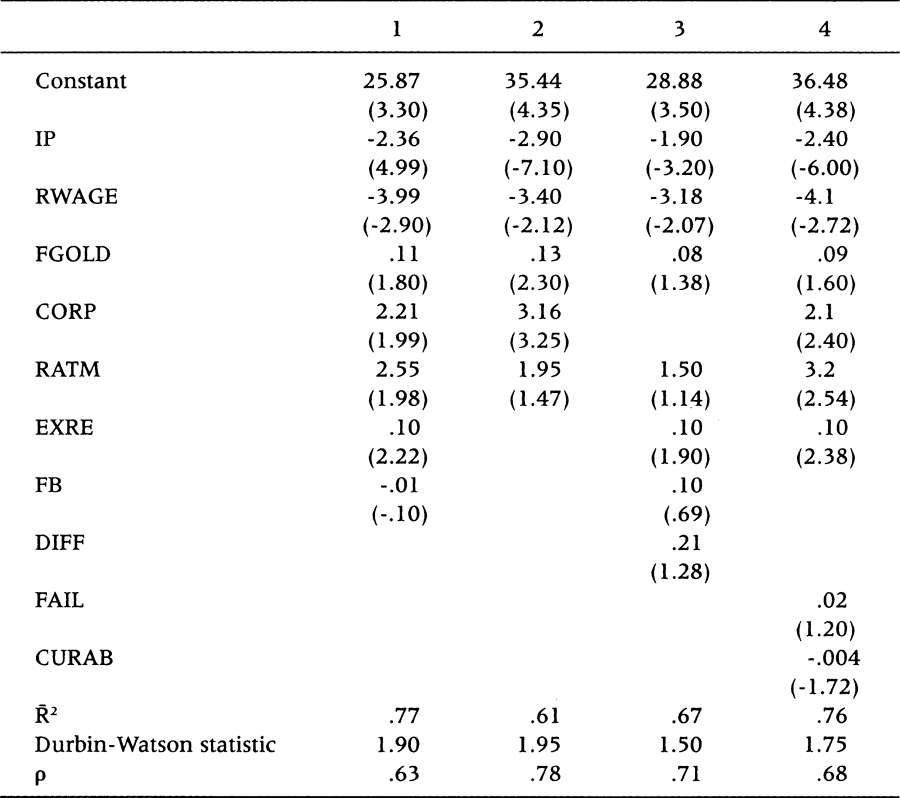

Three of the coefficients in table 3.3, industrial production, real wages, and free gold, are uniformly of the hypothesized sign and are significant at least at the 10 percent level and usually at the 1 percent level for a one-tailed test. During this period, the Fed tightened money when real wages or industrial production rose and when free gold fell.

TABLE 3.3. Explaining Open Market Operations Monthly Data, February 1930 to February 1933 (Dependent variable: securities plus bills bought)

Source: See text.

Note: t-statistics in parentheses.

The loan liquidation variable (RATM) is also of the hypothesized sign and is usually significant at least at the 10 percent level. This variable indicates that, other things being equal, as the loan-liquidation effect took hold (that is, as banks become more dependent on bills and security investments for their earnings), Fed policy became less expansionary, as our hypothesis implies.

The bond risk variable (DIFF) also has the correct sign and is almost significant at the 10 percent level. But an alternative measure of the capital loss variable (CORP) has the wrong sign, and the coefficient is significant, although RATM, which is significant, may already reflect this capital-loss effect. The explanation of the coefficient on CORP is not clear and calls for further analysis.

Among the international variables, the free gold variable (FGOLD) has the predicted sign, as does “currency sent to and from banks abroad” (CURAB). Alternative foreign deposit variables, however, do not show up as well, perhaps because the data for foreign balances include balances held at the New York Fed. Results for deposits of failed bank (FAIL) indicate that the Federal Reserve was unconcerned about all banks.64

Finally, excess reserves are indeed significant determinants of Fed policy during this period, but the coefficient is the opposite sign of that implied by the Brunner-Meltzer hypothesis. The Federal Reserve seemed to have reinforced excess reserves rather than worked against them; other variables remain unchanged.

In summary, the results on the main domestic and international variables appear consistent with our major hypotheses, and the Brunner-Meltzer hypotheses are not supported.

THE FEDERAL RESERVE AND THE PROBLEM OF BANK REGULATION: CONCLUDING REMARKS

We have argued that conflicts of interest within the Federal Reserve System, and between it and the rest of the economy, help account for the Fed’s notorious failure to arrest the Great Contraction. Although our findings are tentative, we believe we have established a prima facie case that previous accounts of the Fed in this period are mistaken in several important respects. There were, for example, real international constraints on the Fed throughout the period 1929 to 1932. Free gold was a problem until early 1932; thereafter, the loss of foreign deposits in private banks and the need to maintain the 40 percent gold cover on Federal Reserve notes constrained the Fed. As a consequence of what we termed the loan liquidation effect, bitter conflicts arose within the Fed concerning yields of short-term government securities.

By ignoring or abbreviating consideration of these factors, the existing literature has failed to come to grips with important historical questions and major theoretical points. Viewed in terms of our analysis, most of the mystery evaporates about two controversial issues in the later financial history of the Depression: the final disastrous run on the banks that led to the “bank holiday” of early 1933 and all the subsequent worries within the system about inflation after 1935. Both of these are almost unintelligible in terms of the standard historiography. That the Federal Reserve System largely sat on its hands as the entire American financial structure collapsed seems unbelievable. That anyone could fear “inflation” in 1935 to 1936 is not any more comprehensible.

In our view, of course, neither of these issues poses a problem. At the January 4, 1933, meeting, before the final banking crisis and after Governor Meyer observed that “at no time since the war has the relation between the open market policy of the Federal Reserve System and the general economic situation been so important,” Governor George Norris of Philadelphia aptly summarized our thesis. “Further increases in excess reserves,” he noted, “would adversely affect bank earnings, and incur the risk of disturbance which might arise from eliminating interest on deposits.”65

As the Depression deepened, the loan liquidation effect proceeded apace. By the mid-thirties, the position of all the Federal Reserve banks had come to resemble the position of Chicago in 1932. With their earnings tied directly to rates on the government securities they now widely held, most bankers, not surprisingly, favored the increases in reserve requirements that the Fed eventually awarded them. They were less concerned with the effects these might have on the rest of the economy.66

Previous research has failed to reckon with the possibility of what might be termed a “supply-side liquidity trap.” As Keynes alone seems to have recognized (see the headnote), the capitalist organization of finance implies that interest rates may fail to drop low enough to revive an economy because bank earnings might not permit it in an acute depression. Moreover, contemporary students of money and banking have not reconciled a fundamental problem of the current system of bank regulation: that the Federal Reserve System is charged with performing two often incompatible tasks—that of advancing the interests of a specific industry while simultaneously overseeing the protection of other businesses and the public at large.

A Note on Sources

Specification of all the variables used in this paper is contained in appendix 1 of our “Monetary Policy.” Most data came from the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Banking and Monetary Statistics (Washington, D.C., 1943), hereafter BMS. Other variables, not drawn from that source or indirectly derived from figures in it, follow. CURAB, shipments of currency abroad from New York banks in thousands of dollars: Federal Reserve Bulletin, January 1932, p. 9, and February 1933, p. 103. Figures do not reflect outflows of currency from non–New York banks. FAIL, deposits of suspended banks (in $ thousands): Federal Reserve Bulletin, September 1937, p. 909. Figures are monthly, and cover all banks. RWAGE, M. Ada Beney, Wages, Hours, and Employment in the United States, 1914–36, National Industrial Conference Board Study No. 229. (New York, 1936), p. 50. FB, monthly data for total short-term foreign liabilities reported by banks in the United States (in $ millions): BMS, pp. 574–80, and subtract out French foreign balances after January 1932, since the Fed had reached an agreement with the French Central Bank concerning removal of the balances, and monetary authorities proceeded in the expectation they would be removed. FGOLD, free gold: February 1930 to January 1932: BMS as described in Federal Reserve Bulletin, March 1932. See also H. Villard, “The Federal Reserve System’s Monetary Policy in 1931 and 1932,” Journal of Political Economy, 45 (December 1937), 734. February 1932 to February 1933, FGOLD is represented by bank excess reserves, to take account of Glass-Steagall. The data are from Annual Report of the Federal Reserve Board, 1933 (Washington, D.C.), p. 94, Table 9. IP, manufacturing and mining production, seasonally adjusted: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Washington, D.C., 1960), pp. 150–151. OMO, bills purchased plus government securities purchased, from BMS. RATM, the ratio of loans and long-term bonds to total assets for non–New York reserve city banks and Chicago central reserve city banks, has been converted to monthly data by linear extrapolation from quarterly data in BMS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Earlier versions of this chapter were read at the Annual Conferences of the Southern Economics Association and the American Historical Association. The authors are especially grateful to Richard Sylla and Peter Temin for extensive comments on several drafts. For other assistance, they should also like to thank Carl Backlund, Samuel Bowles, James Crotty, Richard Duboff, Michael Edelstein, Barry Eichengreen, John Garrett, Brian Gendreau, Stephen Goldfeld, Ellis Hawley, Edward Herman, Robert Johnson, Charles Kindleberger, Stanley Lebergott, Richard Nicodemus, Leonard Rapping, Juliet Schor, Barrie Wigmore, David Weiman, and the editors and referees of the Journal of Economic History. This essay was in every sense joint work, and the alphabet was therefore allowed to determine the order of the authors’ names. The essay has also benefited liberally from the discussion of the American political economy of the late 1920s and early 1930s in Thomas Ferguson, Critical Realignment: The Fall of the House of Morgan and the Origins of the New Deal (New York, Oxford University Press, forthcoming). For further discussion of the issues in this paper see Epstein and Ferguson, “Answers to Stock Questions: Fed Targets, Stock Prices, and the Gold Standard in the Great Depression,” Journal of Economic History, 51, 1 (March 1991), 190–200.