CHAPTER 8

Newspapers, Theses, and Brazilian Literature

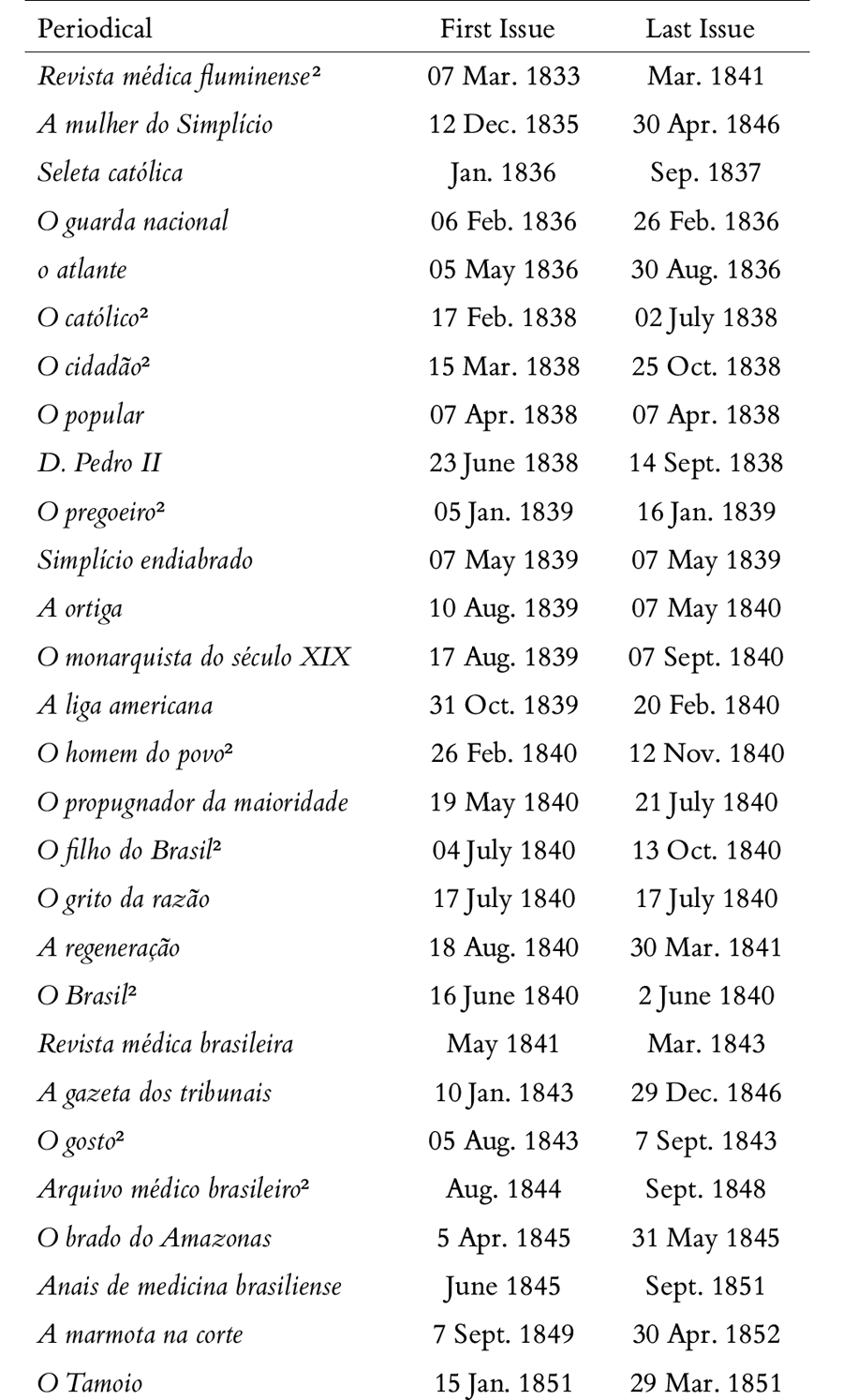

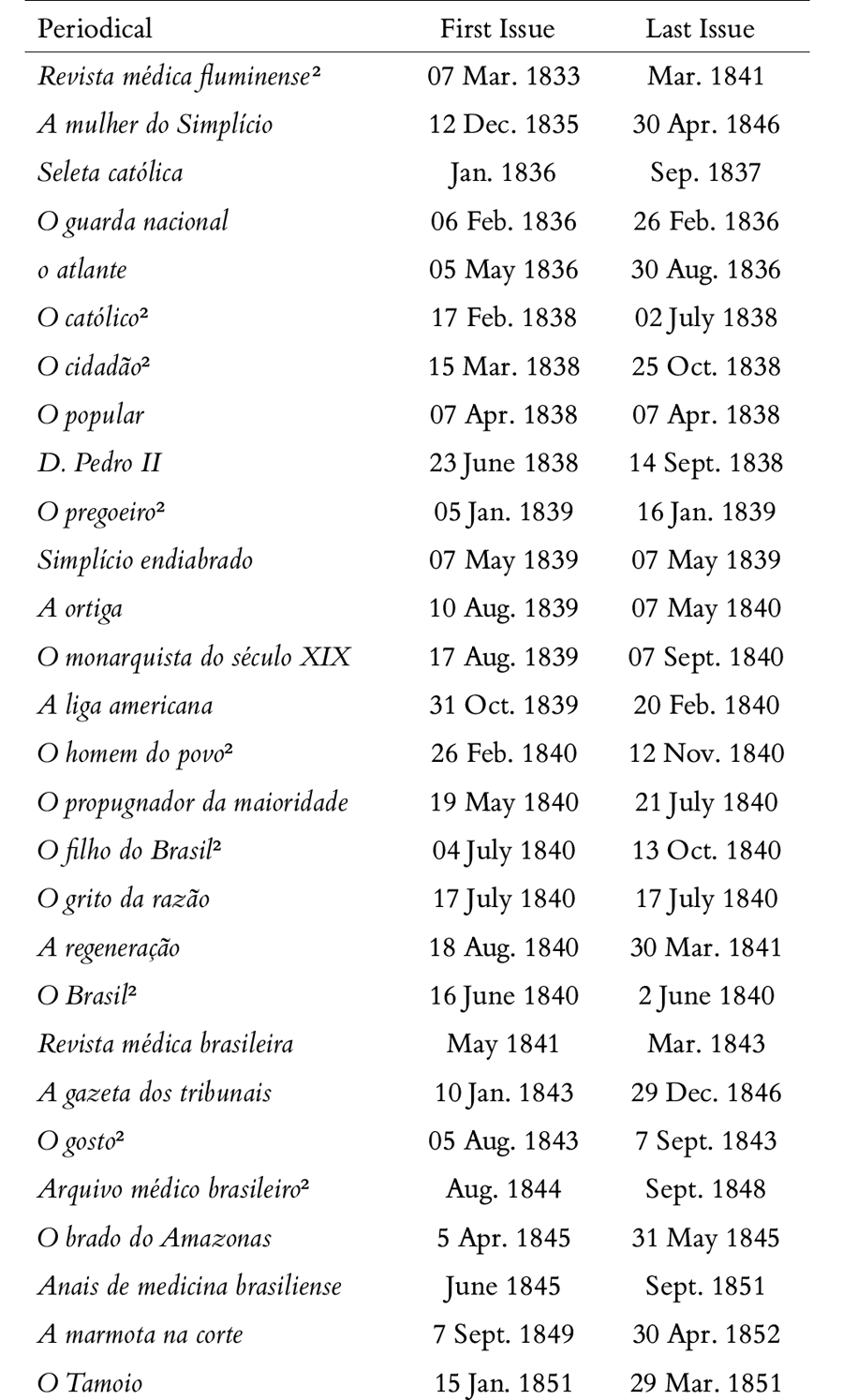

BETWEEN 1835 AND 1851 Francisco de Paula Brito’s Impartial Press printed approximately twenty-eight newspapers.1 Some of them, as we have seen in the case of O cidadão, were also printed by other presses during the course of their publication. Another important point is the political diversity of those papers. As we will see, Paula Brito became a staunch ally of the Conservative party. Nevertheless, for the good of the business, he continued to be a “free printer,” as the Impartial Press printed opposition and government newspapers. Many of them attacked each other, like O Brasil, which was conservative to its core, and A regeneração, which was linked to the Liberals who supported the early declaration of the young emperor’s majority. Unlike the Regencies, during that period a clearer distinction seems to have been established between the roles of printers and publishers on one hand and editors and authors on the other. At least, this is suggested by the editor of A ortiga, one of the newspapers printed at the Impartial Press:

First of all, we will say that as the editor of this paper, Mr. Printer, under whose power we find ourselves, and there being agreement between us and him in all things, that is, principles, good faith, and money, the various articles which, from now on, will be the responsibility of their authors, under the heroic names they adopt, for example—canoe (we will define this at the opportune time) clarion, tightrope, trumpet, etc., etc., thus giving our printer and publisher the glory of good typographical execution, if he does it, and our eternal recognition, which will go hand in hand with our existence, for the secrets he keeps about us, although that is the greatest distinction a public printer can have.2

In many cases, perhaps most, printers and publishers had no connection whatsoever with the political or apolitical opinions of the newspapers they printed. Therefore, as their authors were entirely responsible for their written content, it was up to the printer—in this case, Paula Brito—to ensure the graphic quality of the publication and the anonymity of its authors, as the law required. When each played their part, a pact was established among the parties that was based on “principles, good faith” and, it is important to note, money. Table 5 and Figure 15 show the variety of titles printed by Paula Brito’s Impartial Press, as well as the production indicators. The press campaign to declare Pedro II’s majority must have been reflected in the increased number of new papers published in 1840, the most significant year of that period. However, in addition to political broadsheets, the Impartial Press also printed Catholic, literary, and scientific journals. The scientific publications included the following medical journals: Revista médica fluminense, Revista médica brasileira, Arquivo médico brasileiro, and Anais de medicina brasiliense. A closer look at these publications would confirm a continuity among them, as, except for the Arquivo médico brasileiro, edited by Dr. Ludgero da Rocha Ferreira Lapa, the others were linked to the Imperial Academy of Medicine of Rio de Janeiro.3

In 1844, Paula Brito printed some issues of Arquivo médico brasileiro: Gazeta mensal de medicina, cirurgia e ciências acessórias (Brazilian medical archive: Monthly gazette of medicine, surgery, and accessory sciences). However, its editor seems to have been unhappy with the printer, whom he blamed for delays in the publication and consequently the distribution of the journal. Clearly annoyed, he published a notice in the journal asking the printer to make a public apology to its subscribers. Paula Brito did not overlook the taunt and published his response right below the editor of the Arquivo médico brasileiro’s notice, blaming the delay on the overwhelming amount of work at the press. As a result of that episode, Dr. da Rocha Ferreira Lapa must have decided to dispense with the Impartial Press’s services and have the journal printed at Berthe & Haring’s Press on Rua do Ouvidor, no. 123.4

TABLE 5. Periodicals printed by Francisco de Paula Brito’s Impartial Press (1835–1851)1

Source: Catalog of periodicals in the Arquivo Edgard Leuenroth (AEL-Unicamp).

1. Initially printed by Brito & Co.’s Fluminense Press.

2. In addition to the Impartial Press, some issues were printed by other presses based in Rio de Janeiro.

FIGURE 15. New periodicals printed by Francisco de Paula Brito’s Impartial Press (1835–1851). Source: Catalogue of Periodicals in the Arquivo Edgard Leuenroth (AEL-Unicamp)

However, Paula Brito maintained good relations with the publishers of the Anais de medicina brasiliense (Annals of Brazilian medicine), the journal of the Imperial Academy of Medicine. In early June 1846, the beginning of a new volume of the publication, the editor, Dr. Francisco de Paula Cândido, mentioned the “efforts and intelligence of the printer,” to whom he owed “not only the improvement of the new and larger format, which the journal will have from now on, as well as the considerable reduction in the work load of the editors of scientific articles, as Mr. Paula Brito was responsible for proofreading, etc., and other detailed tasks.”5 Days later, on June 30, the “diligence and care of Mr. Paula Brito” in printing the journal were once again underscored at the Annual Session of the Imperial Academy of Medicine. According to the minutes for that session, Paula Brito was entrusted with the “publishing and distribution” of the journal, being remunerated with copies of the publication, an agreement that relieved the Academy of the “risk of financial losses due to a lack of subscribers.”6 However, his remuneration depended on that institution’s budget. In 1847 and 1848, His Majesty’s government appropriated just 1,600,000 réis for the Imperial Academy of Medicine, which was a paltry sum compared to the 20,120,000 réis earmarked for the Academy of Fine Art.7

These amounts suggest that Paula Brito was not well paid for his work. In any event, the connection between the printer and the physicians at the Imperial Academy of Medicine may have had one advantage: the publication of theses defended at the Rio de Janeiro School of Medicine. The Law of October 3, 1832, which reorganized the medical and surgical schools of Rio de Janeiro and Bahia, covered the subject of theses in article 26, clearly stating that no student could be awarded the title of Doctor of Medicine without defending a thesis written in Portuguese or Latin, according to the regulations of each institution. What interests us here is that the law stipulated that these theses had to be “printed at the candidates’ expense.”8 As a result, newly graduated doctors became an important clientele for printers in the two cities that housed the Empire’s medical schools. An overview of this market in Rio between 1844 and 1845 can be obtained from the titles published in the “Medical Works” and “Medical Works Published in Rio de Janeiro” sections of the Arquivo médico brasileiro. As shown in Table 6, forty-two theses were printed at eleven different presses during that period, as reported in Dr. da Rocha Ferreira Lapa’s journal.

TABLE 6. Medical theses published in Rio de Janeiro and listed in the Arquivo médico brasileiro (1844–1845)

Source: Arquivo médico brasileiro: Gazeta mensal de medicina, cirurgia e ciências acessórias, Rio de Janeiro, 1844–1845.

In the mid-1840s, the Impartial Press and the Laemmert brothers’ Universal Press were the go-to establishments for young doctors in Rio wanting to print their theses. The good service provided to the Imperial Academy of Medicine when publishing and distributing its journal may have been a determining factor behind the twelve theses printed by Paula Brito, which put him at the top of the ranking. In some cases, physicians associated with the Imperial Academy were professors at the Medical School, which was based in the former Jesuit college. For example, as the editor of the Anais de medicina brasiliense, Dr. Francisco de Paula Candido maintained close contact with Paula Brito. He was also a lecturer who taught first-year students at the Medical School.9 Therefore, networks formed since the 1830s, when Paula Brito began printing the Revista médica fluminense, certainly contributed to newly graduated doctors’ preference for going to Praça da Constituição, no. 64, to print their theses. This was the case with Dr. João Arnaud de Araújo Lima, a native of Campina, near the town of Santa Luzia do Norte, Alagoas, who had his Dissertation on Amenorrhea or Suppression of Menstrual Flow printed there in 1844, as did his classmate, Dr. Joaquim Manuel Macedo, the author of Considerações sobre a nostalgia (Considerations on nostalgia), a thesis printed by the Impartial Press that same year.10

FIGURE 16. Title page of Considerações sobre a nostalgia (On nostalgia), thesis by Joaquim Manuel de Macedo (1844)

Shortly before obtaining his medical degree,11 Dr. Macedo wrote a novel entitled A moreninha (The brunette), published in a limited edition at the Tipografia Francesa, or French Press. Saint-Amant, the owner of the establishment located on Rua de São José, no. 64,12 had clearly offered the best terms to the budding novelist, who must have paid for it out of his own pocket. However, the book sold out in a few months. It was such a success that in April 1845, the publishers Dutra & Mello embarked on a campaign in the Diário do Rio de Janeiro to enlist subscribers—from among “lovers of literature, and especially the fair sex, to whose grace and kindness the gallant Moreninha owes a debt”—for a new edition of the novel. Subscriptions could be purchased at the bookshops of the Laemmert brothers, Paula Brito, and Bender, and the new edition would be illustrated with “five fine prints portraying the most important scenes in the story.”13

FIGURE 17. Title page of Um roubo na Pavuna (A robbery in Pavuna), novel published in 1843

Although he helped sell subscriptions for the second edition of A morenina, along with the Laemmert and Bender bookshops, Paula Brito played a very important role at a time when novels seduced both the intellectuals and ordinary readers of Rio de Janeiro. In 1836, following the French model, O chronista (The chronicler) was apparently the first work in that genre to be serialized in that city’s newspapers. The footer of the first page was reserved for the readers’ entertainment, and soon, following the European example, French novels colonized that space. In 1839, however, the Jornal do commercio began publishing prose fiction written by Brazilian authors, which was a novelty at the time. Paula Brito, Justiniano José da Rocha, and João Manuel Pereira da Silva were the first Brazilian authors to publish serialized novels in the Jornal do commercio. One striking feature of these early narratives, going beyond adapting the genre of the novel to Brazilian characteristics, was the legitimization of a conception of national literature, built up in opposition not only to Europe but also to the provinces, with Rio de Janeiro as its hub.14

In the course of this process, literary publishers emerged in Rio de Janeiro. When it comes to novels with Brazilian DNA, a goodly number of pages were written before Macedo published A moreninha in September 1844. When serialized novels—Brazilian or foreign—invaded Rio’s newspapers, the owners of those publications realized that they were a magnet for readers. However, despite the narratives published in Jornal do commercio in 1839, the performance of the “Brazilian novel” had not yet been tested in book form. This occurred in May 1843, when Paula Brito printed and sold by subscription the “Brazilian novel” Um roubo na Pavuna (A robbery in Pavuna).15 It was a small-format, eight-page book by an anonymous author who dedicated it to his “dear mother.” We do not know whether the novel received good reviews, or whether Paula Brito was just the printer or if he took the risk of publishing it himself after purchasing the manuscript from its author—later identified as Luís da Silva Alves de Azambuja Susano.16

About a month after the publication of Um roubo na Pavuna, in June or August 1843, Antonio Gonçalves Teixeira e Sousa serialized his work O filho do pescador, romance brasileiro original (The fisherman’s son, an original Brazilian novel) in O Brasil, a newspaper then printed at the Impartial Press.17 As soon as the final installment had come out, Paula Brito published it as a book in a single 152-page volume sold at his bookshop for 1,000 réis.18 Thus, Texeira e Sousa’s work paved the way for many other novels and short stories in nineteenth-century Brazil—they were only published in book form after reaching their readers in installments found in the footers of newspapers. Success during that initial stage certainly ensured the second, which made the newspapers’ serialized novel sections a well-calibrated gauge of the market for publishers. However, the publication of Um roubo na Pavuna and particularly O filho do pescador in serial and book form begs at least two questions: was Paula Brito aware of Rio de Janeiro readers’ interest in Brazilian novels or—as the printer and publisher of books and newspapers—was he deliberately intervening in the development of that interest?

In the prospectus for Arquivo romântico brasileiro, a periodical that publicized the novels Paula Brito published as of February 1847, we can find some significant answers to these questions:

Having recently developed in our readers an excessive taste for reading novels, or novellas, which is the same; and our newspapers serializing French novels almost daily, we observed that not a few readers, after the serialized novels are finished, will buy them in booklets, thus paying twice, once with the newspaper subscription, and again when buying the booklets, which will not happen with a regular publication that publishes novels; for once the issues in which the novel is published are purchased, or subscribed, there is nothing left to do but the binding, and there you have a beautiful and clear volume of novels. This has been attempted more than once, because such publications have been unsuccessful, and never for lack of subscribers; for the reason is that when starting to publish a novel in a publication produced for that purpose only, the major newspapers also begin to publish it, and subscribers having the same novels as [those serialized in] the daily newspapers do not renew their subscriptions, and so the publication of novels dies a slow death: this was the case with the Arquivo Romântico.

Notwithstanding these sad examples, we will undertake a publication with the above title, which will only publish Brazilian novels; that way no one will publish them but us, and only us.19

In 1847, the taste for novels was recent and growing. Paula Brito perceptively observed that readers who were eager to follow their plots were willing to pay twice for the same work, by subscribing to the newspaper and buying the book. His publication aimed to eliminate that extra expense by serializing novels in fascicles that could be collected and bound when the last installment was published. However, to ensure the project’s success, publishing Brazilian authors was the only way to deal with the unfair competition of translations. After all, at a time when bootlegging French books was a common practice, it was impossible to purchase exclusive publication rights for a specific novel. Thus, the key to survival was the exclusivity ensured by the publication of Brazilian authors—“no one will publish them but us.” Therefore, the publisher’s first justification of the preference for Brazilian novels was based on the realities of the marketplace. Nevertheless, there were other reasons:

Two advantages will result from this, or rather three: first, by writing about our own things, we will get to know our country, our antiquities, and all our things better; second, it adds to our literature, which is already vast; third, it stimulates the genius of our young people, who spurred by example have hurled themselves into the writers’ arena. In view of these advantages, we hope that all lovers of novels will subscribe to this publication, which is 500 réis per month, giving a page and a half, on good paper, good type, forming a clear edition. The Arquivo romântico brasileiro comes out every Saturday, when it is not a holiday. The publishers started their career by publishing the Brazilian novel by Mr. Antonio Gonçalves Teixeira e Sousa, which bears the title: Tardes de um pintor, ou, Intrigas de um Jesuíta (Afternoons of a painter, or, Intrigues of a Jesuit). The public’s favorable reception of Filho do pescador and Fatalidades de dous jovens (Fates of two young men) by the same author, made us turn to this novel, which, on a larger scale, is far superior to those two.20

Following Paula Brito’s reasoning, the nationalist argument preceded the justification of market forces. The first was based on the need to promote a Brazilian literature crafted by Brazilian authors. From a publisher’s perspective, publishing national authors meant first offering a product that stood apart from the French translations that swamped the newspaper footers and bookstores of Rio de Janeiro. Indeed, the novels of Teixeira e Sousa, an author already known to and well regarded by the public, would be perfectly suited to the pages of the Arquivo romântico brasileiro, whose serialized works were printed at the Teixeira & Co. Press, an establishment in which Paula Brito had been a partner since 1845.

The eldest son of a Portuguese merchant and a free parda woman, Teixeira e Sousa was born in Cabo Frio, Rio de Janeiro Province, in 1812. Due to his father’s financial struggles, he was forced to leave school at the age of ten and make his living as a carpenter. When he was thirteen, he moved to the provincial capital to hone his craft. In around 1830, the young man returned to Cabo Frio, seriously ill with a lung disease. In the following years, Teixeira e Sousa suffered a number of misfortunes, losing his siblings and his parents, and decided to return to Rio. However, during his convalescence in Cabo Frio, he had devoted himself to his studies. During that time, according to Joaquim Norberto, who published a biography of Teixeira e Sousa in the journal of the Brazilian Historical Geographic and Ethnographic Institute, the young man “not only read but avidly devoured all the books that came his way.” According to his biographer, love of learning and the adversities of life were the ingredients that brought about Teixeira e Sousa’s transformation: “The hymn of consolation had poured into his soul, tortured by loss, and the rude worker became a poet!”21

FIGURE 18. Title page of Antonio Gonçalves Teixeira e Sousa’s novel Tardes de um pintor (Afternoons of a painter), and the author’s portrait on the frontispiece, published in the Brazilian Romantic Series by Paula Brito

Young, pardo, a lover of learning and poetry. His affinities with Paula Brito were considerable, and in 1840, it was precisely that publisher who took him in “with the smile of satisfaction on his lips, and used his work, providing him with a livelihood.”22 The biographer chose the right verb, because he was certainly correct in saying that Paula Brito “used” Teixeira e Sousa’s work, “providing him with a livelihood” in exchange. The young man quickly learned the art of printing and the tricks of the book trade, becoming Paula Brito’s business partner in the Teixeira & Co. Press, located on Rua dos Ourives, no. 21. That combination press and bookshop was active from 1845 to 1849, when Teixeira e Sousa—by then married with children—decided to become a schoolmaster in Engenho Velho.23 However, it was the literary skills of Teixeira e Sousa, described as a “fruitful writer, imaginative novelist, inspired poet,” that were first recognized and “used” by Paula Brito in his publishing endeavors. In addition to the novel O filho do pescador, Paula Brito printed the Cânticos líricos (Lyrical songs), verses whose second volume, published in 1842, was dedicated to Judge Paulino José Soares de Sousa, the future Viscount of Uruguai. In 1844, it was the turn of Três dias de um noivado (Three days of an engagement), another book of poetry. Then, in 1847, came the epic A independência do Brasil (The independence of Brazil), in twelve cantos, considered by a contemporary reader to be replete with “infinite beauty.”24

The Impartial Press would also publish works by other Brazilian authors. In addition to Teixeira e Sousa, Impartial’s catalog also included Gonçalves de Magalhães and Martins Pena, primarily the author of skits and farces. However, despite Paula Brito’s efforts to publish novels, plays, and books of poetry by Brazilian authors, possibly with a view to creating a market for Brazilian literature, the number of such works was smaller than the other categories in the publisher’s catalog, such as Medical School theses and political speeches. According to the catalog of works produced by Paula Brito’s presses, collected and published by Eunice Ribeiro Gondim in 1965 and recently expanded by José de Paula Ramos Júnior, Marisa Midori Deaecto, and Plínio Martins Filho, it included three novels, four books of poetry and thirteen plays, compared with, for example, thirty-five medical theses and fourteen speeches by illustrious politicians such as Martins Francisco Ribeiro de Andrada, Francisco Gê Acayaba de Montezuma, and Paulino José Soares de Sousa.25 Nevertheless, the publication of Brazilian novelists, playwrights, and poets by Paula Brito would gain fresh impetus with the founding of the publishing firm Empresa Dous Dezembro.

Therefore, to recap a few points, we have so far seen that, after founding the Impartial Press, Paula Brito managed to expand the business, buy a mechanical press, print several newspapers and journals and numerous Medical School theses, and take a chance on publishing Brazilian authors who could successfully rival French translations. But after all, who built Thebes, the city of the Seven Gates? In other words, who composed, printed, and distributed these publications? How was the world of work organized around Francisco de Paula Brito?