When a man has learned within his heart what fear and trembling mean, he is safeguarded against any terror produced by outside influences.

—I Ching, Hexagram #51 (circa 2500 BC)

NO MATTER HOW SELF-ASSURED WE ARE, in a fraction of a second, our lives can be utterly devastated. As in the biblical story of Jonah, the unknowable forces of trauma and loss can swallow us whole, thrusting us deep into their cold dark belly. Entrapped yet lost, we become hopelessly frozen by terror and helplessness.

Early in the year 2005, I walked out of my house into a balmy Southern California morning. The gentle warmth and soft sea breeze gave a lift to my step. Certainly, this was the kind of winter morning that makes everyone in the rest of the country (with the possible exception of Garrison Keillor of Lake Wobegon) want to abandon their snow shovels and move to the Southland’s warm, sunny beaches. It was the beginning of a perfect kind of day, a day when you feel certain that nothing can go wrong, when nothing bad can possibly happen. But it did.

I walked along, absorbed in happy anticipation of being with my dear friend Butch for the celebration of his sixtieth birthday.

I stepped out into a crosswalk …

… The next moment, paralyzed and numb, I’m lying on the road, unable to move or breathe. I can’t figure out what has just happened. How did I get here? Out of a swirling fog of confusion and disbelief, a crowd of people rushes toward me. They stop, aghast. Abruptly, they hover over me in a tightening circle, their staring eyes fixed on my limp and twisted body. From my helpless perspective they appear like a flock of carnivorous ravens, swooping down on an injured prey—me. Slowly I orient myself and identify the real attacker. As in an old-fashioned flashbulb photo, I see a beige car looming over me with its teeth-like grill and shattered windshield. The door suddenly jerks open. A wide-eyed teenager bursts out. She stares at me in dazed horror. In a strange way, I both know and don’t know what has just happened. As the fragments begin to converge, they convey a horrible reality: I must have been hit by this car as I entered the crosswalk. In confused disbelief, I sink back into a hazy twilight. I find that I am unable to think clearly or to will myself awake from this nightmare.

A man rushes to my side and drops to his knees. He announces himself as an off-duty paramedic. When I try to see where the voice is coming from, he sternly orders, “Don’t move your head.” The contradiction between his sharp command and what my body naturally wants—to turn toward his voice—frightens and stuns me into a sort of paralysis. My awareness strangely splits, and I experience an uncanny “dislocation.” It’s as if I’m floating above my body, looking down on the unfolding scene.

I am snapped back when he roughly grabs my wrist and takes my pulse. He then shifts his position, directly above me. Awkwardly, he grasps my head with both of his hands, trapping it and keeping it from moving. His abrupt actions and the stinging ring of his command panic me; they immobilize me further. Dread seeps into my dazed, foggy consciousness: Maybe I have a broken neck, I think. I have a compelling impulse to find someone else to focus on. Simply, I need to have someone’s comforting gaze, a lifeline to hold onto. But I’m too terrified to move and feel helplessly frozen.

The Good Samaritan fires off questions in rapid succession: “What is your name? Where are you? Where were you going? What is today’s date?” But I can’t connect with my mouth and make words. I don’t have the energy to answer his questions. His manner of asking them makes me feel more disoriented and utterly confused. Finally, I manage to shape my words and speak. My voice is strained and tight. I ask him, both with my hands and words, “Please back off.” He complies. As though a neutral observer, speaking about the person sprawled out on the blacktop, I assure him that I understand I am not to move my head, and that I will answer his questions later.

After a few minutes, a woman unobtrusively inserts herself and quietly sits by my side. “I’m a doctor, a pediatrician,” she says. “Can I be of help?”

“Please just stay with me,” I reply. Her simple, kind face seems supportive and calmly concerned. She takes my hand in hers, and I squeeze it. She gently returns the gesture. As my eyes reach for hers, I feel a tear form. The delicate and strangely familiar scent of her perfume tells me that I am not alone. I feel emotionally held by her encouraging presence. A trembling wave of release moves through me, and I take my first deep breath. Then a jagged shudder of terror passes though my body. Tears are now streaming from my eyes. In my mind, I hear the words, I can’t believe this has happened to me; it’s not possible; this is not what I had planned for Butch’s birthday tonight. I am sucked down by a deep undertow of unfathomable regret. My body continues to shudder. Reality sets in.

In a little while, a softer trembling begins to replace the abrupt shudders. I feel alternating waves of fear and sorrow. It comes to me as a stark possibility that I may be seriously injured. Perhaps I will end up in a wheelchair, crippled and dependent. Again, deep waves of sorrow flood me. I’m afraid of being swallowed up by the sorrow and hold onto the woman’s eyes. A slower breath brings me the scent of her perfume. Her continued presence sustains me. As I feel less overwhelmed, my fear softens and begins to subside. I feel a flicker of hope, then a rolling wave of fiery rage. My body continues to shake and tremble. It is alternately icy cold and feverishly hot. A burning red fury erupts from deep within my belly: How could that stupid kid hit me in a crosswalk? Wasn’t she paying attention? Damn her!

A blast of shrill sirens and flashing red lights block out everything. My belly tightens, and my eyes again reach to find the woman’s kind gaze. We squeeze hands, and the knot in my gut loosens.

I hear my shirt ripping. I am startled and again jump to the vantage of an observer hovering above my sprawling body. I watch uniformed strangers methodically attach electrodes to my chest. The Good Samaritan paramedic reports to someone that my pulse was 170. I hear my shirt ripping even more. I see the emergency team slip a collar onto my neck and then cautiously slide me onto a board. While they strap me down, I hear some garbled radio communication. The paramedics are requesting a full trauma team. Alarm jolts me. I ask to be taken to the nearest hospital only a mile away, but they tell me that my injuries may require the major trauma center in La Jolla, some thirty miles farther. My heart sinks. Surprisingly, though, the fear quickly subsides. As I am lifted into the ambulance, I close my eyes for the first time. A vague scent of the woman’s perfume and the look of her quiet, kind eyes linger. Again, I have that comforting feeling of being held by her presence.

Opening my eyes in the ambulance, I feel a heightened alertness, as though I’m supercharged with adrenaline. Though intense, this feeling does not overwhelm me. Even though my eyes want to dart around, to survey the unfamiliar and foreboding environment, I consciously direct myself to go inward. I begin to take stock of my body sensations. This active focusing draws my attention to an intense, and uncomfortable, buzzing throughout my body.

Against this unpleasant sensation, I notice a peculiar tension in my left arm. I let this sensation come into the foreground of my consciousness and track the arm’s tension as it builds and builds. Gradually, I recognize that the arm wants to flex and move up. As this inner impulse toward movement develops, the back of my hand also wants to rotate. Ever so slightly, I sense it moving toward the left side of my face—as though to protect it against a blow. Suddenly, there passes before my eyes a fleeting image of the window of the beige car, and once again—as in a flashbulb snapshot—vacant eyes stare from behind the spiderweb of the shattered window. I hear the momentary “chinging” thud of my left shoulder shattering the windshield. Then, unexpectedly, an enveloping sense of relief floods over me. I feel myself coming back into my body. The electric buzzing has retreated. The image of the blank eyes and shattered windshield recedes and seems to dissolve. In its place, I picture myself leaving my house, feeling the soft warm sun on my face, and being filled with gladness at the expectation of seeing Butch that evening. My eyes can relax as I focus outwardly. As I look around the ambulance, it somehow seems less alien and foreboding. I see more clearly and “softly.” I have the deeply reassuring sense that I am no longer frozen, that time has started to move forward, that I am awakening from the nightmare. I gaze at the paramedic sitting by my side. Her calmness reassures me.

After a few bumpy miles, I feel another strong tension pattern developing from the spine in my upper back. I sense my right arm wanting to extend outward—I see a momentary flash; the black asphalt road rushes toward me. I hear my hand slapping the pavement and feel a raw burning sensation on the palm of my right hand. I associate this with the perception of my hand extending to protect my head from smashing onto the road. I feel tremendous relief, along with a deep sense of gratitude that my body did not betray me, knowing exactly what to do to guard my fragile brain from a potentially mortal injury. As I continue to gently tremble, I sense a warm tingling wave along with an inner strength building up from deep within my body.

As the shrill siren blasts away, the ambulance paramedic takes my blood pressure and records my EKG. When I ask her to tell me my vital signs, she informs me in a gentle professional manner that she cannot give me that information. I feel a subtle urge to extend our contact, to engage with her as a person. Calmly, I tell her that I’m a doctor (a half-truth). There is the light quality of a shared joke. She fiddles with the equipment and then indicates that it might be a false reading. A minute or two later she tells me that my heart rate is 74 and my blood pressure is 125/70.

“What were my readings when you first hooked me up?” I ask.

“Well, your heart rate was 150. The guy who took it before we came said it was about 170.”

I breathe a deep sigh of relief. “Thank you,” I say, then add: “Thank God, I won’t be getting PTSD.”

“What do you mean?” she asks with genuine curiosity.

“Well, I mean that I probably won’t be getting posttraumatic stress disorder.” When she still looks perplexed, I explain how my shaking and following my self-protective responses had helped me to “reset” my nervous system and brought me back into my body.

“This way,” I go on, “I am no longer in fight-or-flight mode.”

“Hmm,” she comments, “is that why accident victims sometimes struggle with us—are they still in fight-or-flight?”

“Yes, that’s right.”

“You know,” she adds, “I’ve noticed that they often purposely stop people from shaking when we get them to the hospital. Sometimes they strap them down tight or give them a shot of Valium. Maybe that’s not so good?”

“No, it’s not,” the teacher in me confirms. “It may give them temporary relief, but it just keeps them frozen and stuck.”

She tells me that she recently took a course in “trauma first-aid” called Critical Incident Debriefing. “They tried it with us at the hospital. We had to talk about how we felt after an accident. But talking made me and the other paramedics feel worse. I couldn’t sleep after we did it—but you weren’t talking about what happened. You were, it seemed to me, just shaking. Is that what brought your heart rate and blood pressure down?”

“Yes,” I told her and added that it was also the small protective spontaneous movements my arms were making.

“I’ll bet,” she mused, “that if the shaking that often occurs after surgery were allowed rather than suppressed, recovery would be quicker and maybe even postoperative pain would be reduced.”

“That’s right,” I say, smiling in agreement.

Horrible and shocking as this experience was, it allowed me to exercise the method for dealing with sudden trauma that I had developed, written about and taught for the past forty years. By listening to the “unspoken voice” of my body and allowing it to do what it needed to do; by not stopping the shaking, by “tracking” my inner sensations, while also allowing the completion of the defensive and orienting responses; and by feeling the “survival emotions” of rage and terror without becoming overwhelmed, I came through mercifully unscathed, both physically and emotionally. I was not only thankful; I was humbled and grateful to find that I could use my method for my own salvation.

While some people are able to recover from such trauma on their own, many individuals do not. Tens of thousands of soldiers are experiencing the extreme stress and horror of war. Then too, there are the devastating occurrences of rape, sexual abuse and assault. Many of us, however, have been overwhelmed by much more “ordinary” events such as surgeries or invasive medical procedures.1 Orthopedic patients in a recent study, for example, showed a 52% occurrence of being diagnosed with full-on PTSD following surgery.

Other traumas include falls, serious illnesses, abandonment, receiving shocking or tragic news, witnessing violence and getting into an auto accident; all can lead to PTSD. These and many other fairly common experiences are all potentially traumatizing. The inability to rebound from such events, or to be helped adequately to recover by professionals, can subject us to PTSD—along with a myriad of physical and emotional symptoms. I dread to think how my accident might have turned out had I lacked my knowledge or not had the good fortune to be helped by that woman pediatrician and her scent of holding kindness.

Over the past forty years, I have developed an approach to help people move through the many types of trauma, including what I went through that February day when I was struck by a car. This method is equally applicable directly after the trauma or many years later—my first serendipitous client, described in Chapter 2, was able to recover from a trauma that occurred about twenty years prior to our sessions together. Somatic Experiencing®, as I call the method, helps to create physiological, sensate and affective states that transform those of fear and helplessness. It does this by accessing various instinctual reactions through one’s awareness of physical body sensations.

Since time immemorial, people have attempted to cope with powerful and terrifying feelings by doing things that contradict perceptions of fear and helplessness: religious rituals, theater, dance, music, meditation and ingesting psychoactive substances, to name a few. Of these various methods for altering one’s way of being, modern medicine has accepted only the use of (limited, i.e., psychiatric) chemical substances. The other “coping” methods continue to find expression in alternative and so-called holistic approaches such as yoga, tai chi, exercise, drumming, music, shamanism and body-oriented techniques. While many people find help and solace from these valuable approaches, they are relatively nonspecific and do not sufficiently address certain core physiological mechanisms and processes that allow human beings to transform terrifying and overwhelming experiences.

In the particular methodology I describe in these pages, the client is helped to develop an awareness and mastery of his or her physical sensations and feelings. My observations, in visiting a few indigenous cultures, suggest that this approach has a certain kinship with various traditional shamanic healing rituals. I am proposing that a collective, cross-cultural approach to healing trauma not only suggests new directions for treatment, but may ultimately inform a fundamentally deeper understanding of the dynamic two-way communication between mind and body.

Over my lifetime, as well as in writing this book, I have attempted to bridge the vast chasm between the day-to-day work of the clinician and the findings of various scientific disciplines, particularly ethology, the study of animals in their natural environments. This vital field reached a pinnacle of recognition in 1973 when three ethologists—Nikolaas Tinbergen, Konrad Lorenz and Karl von Frisch—shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.*

All three of these scientists utilized patient and precise observation to study how animals express and communicate through their bodies. Direct body communication is something that we reasoning, language-based human animals do as well. Despite our apparent reliance on elaborate speech, many of our most important exchanges occur simply through the “unspoken voice” of our body’s expressions in the dance of life. The deciphering of this nonverbal realm is a foundation of the healing approach that I present in this book.

To convey the nature and transmutation of trauma in the body, brain and psyche, I have also drawn upon selected findings in the neurosciences. It is my conviction that clinical, naturalistic animal studies and comparative brain research can together greatly contribute to the evolution of methodologies that help restore resilience and promote self-healing. Toward this end, I will explain how our nervous system has evolved a hierarchical structure, how these hierarchies interact, and how the more advanced systems shut down in the face of overwhelming threat, leaving brain, body and psyche to their more archaic functions. I hope to demonstrate how successful therapy restores these systems to their balanced operation. An unexpected side effect of this approach is what might be called “Awakening the Living, Knowing Body.” I will discuss how this awakening describes, in essence, what happens when animal instinct and reason are brought together, giving us the opportunity to become more whole human beings.

I aim to speak to the therapists who seek a better understanding of the roots of trauma in brain and body—such as psychological, psychiatric, physical, occupational and “bodywork” therapists. I also hope to reach the many medical doctors who are confounded by patients presenting inexplicable and mutable symptoms, the nurses who have long worked on the frontlines caring for terrified, injured patients and the policy makers concerned with our nation’s problematic healthcare. Finally, I look for the larger audience of voracious readers of a wide variety of subjects—ranging from adventure, anthropology, biology, Darwin, neuroscience, quantum physics, string theory, relativity and zoology to the “Science” section of the New York Times.

Inspired by a childhood of reading Sherlock Holmes, I have attempted to engage the reader in the excitement of a lifelong journey of mystery and discovery. This voyage has carried me into a field that is at the core of what it means to be a human being, existing on an unpredictable and oftentimes violent planet. I have been privileged to study how people can rebound after extreme challenges and have borne witness to the resilience of the human spirit, to the lives of countless people who have returned to happiness and goodness, even after great devastation.

I will be telling some of this story in a way that is personal. The writing of this book has presented me with a very exciting challenge. I offer an account of my own experience as a clinician, scientist and inner explorer. My hope is that the occasional use of storytelling will help to create an accessible work that engages the clinical and scientific, but is sparse on jargon and is not unduly tedious and pedantic. I will utilize case vignettes to illustrate various principles, as well as invite the reader to participate in selected awareness exercises that embody these principles.

While directed to clinicians, physicians and scientists, as well as to interested laymen, ultimately this book is dedicated to those who have been tormented by the hungry ghosts of trauma. To these people, who live in a cage of anxiety, fear, pain and shame, I hope to convey a deeper appreciation that their lives are not dominated by a “disorder” but by an injury that can be transformed and healed! This capacity for transformation is a direct consequence of what I describe in the next section.

In spite of my confusion and disorientation after the crosswalk accident, it was my thoroughly ingrained knowledge of trauma that led me first to request that the off-duty paramedic back off and allow me some space, and then to trust my body’s involuntary shaking and other spontaneous physical and emotional reactions. However, even with my extensive knowledge and experience, I doubt whether I could have done this alone. The importance of the graceful pediatrician’s quiet support was enormous. Her noninvasive warmth, expressed in the calm tone of her voice, her gentle eyes, her touch and scent, gave me enough of a sense of safety and protection to allow my body to do what it needed to do and me to feel what I needed to feel. Together, my knowledge of trauma and the support of a calm present other allowed the powerful and profoundly restorative involuntary reactions to emerge and complete themselves.

In general, the capacity for self-regulation is what allows us to handle our own states of arousal and our difficult emotions, thus providing the basis for the balance between authentic autonomy and healthy social engagement. In addition, this capacity allows us the intrinsic ability to evoke a sense of being safely “at home” within ourselves, at home where goodness resides.

This capacity is especially important when we are frightened or injured. Most every mother in the world, knowing this instinctively, picks up her frightened child and soothes him or her by rocking and holding the child close to her body. Similarly, the kind eyes and pleasant scent of the woman who sat by my side bypassed the rational frontal cortex to reach directly into the recesses of my emotional brain. Thus, it soothed and helped to stabilize my organism just enough so that I could experience the difficult sensations and take steps toward restoring my balance and equanimity.

In 1998, Arieh Shalev carried out a simple and important study in Israel, a country where trauma is all too common.2 Dr. Shalev noted the heart rates of patients seen in the emergency room (ER) of a Jerusalem hospital. These data were easy to collect, as charting the vital signs of anyone admitted to the ER is standard procedure. Of course, most patients are upset and have a high heart rate when they are first admitted to the ER, since they are most likely there as victims of some terrifying incident such as a bus bombing or motor vehicle accident. What Shalev discovered was that a patient whose heart rate had returned to near normal by the time of discharge from the ER was unlikely to develop posttraumatic stress disorder. On the other hand, one whose heart rate was still elevated upon leaving was highly likely to develop PTSD in the following weeks or months.† Thus, in my accident, I felt profound relief when the paramedic in the ambulance gave me the vital signs that indicated my heart rate had returned to normal.

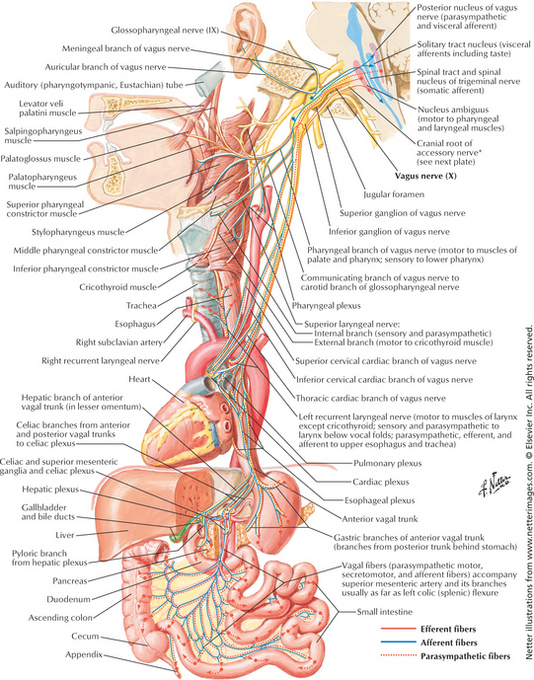

Briefly, heart rate is a direct window into the autonomic (involuntary) branch of our nervous system. A racing heart is part of body and mind readying for the survival actions of fight-or-flight mediated by the sympathetic-adrenal nervous system (please see Diagram A after this page for a detailed depiction of the physiological pathways underlying the classic fight or flight response). Simply, when you perceive threat, your nervous system and body prepare you to kill or to take evasive countermeasures to escape, usually by running away. This preparation for action was absolutely essential on the ancient savannahs, and it is “discharged” or “used up” by all-out, meaningful action. In my case, however, lying injured on the road and then in the confines of the ambulance and the ER—where action was simply not an option—could have entrapped me. My global activation was “all dressed up with nowhere to go.” If, rather than fulfilling its motoric mission in effective action, the preparation for action was interfered with or had lain dormant, it would have posed a great potential to trigger a later expression as the debilitating symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder.

What saved me from developing these symptoms was the ability to bring down my fight-or-flight activation by discharging the immense survival energy through spontaneous trembling. This contained discharge, along with my awareness of the self-protective impulse to move my arms and shield my head, helped return my organism to equilibrium. I was able to surrender to these powerful sensations while remaining fully aware of my spontaneous bodily reactions, and with the pediatrician’s steady presence and “holding of the space,” I could restore my nervous system to equilibrium. By staying aware while “tracking” my spontaneous bodily reactions and feelings,‡ I was able to begin the process of moving through and out of the biological shock reaction. It is this innate capacity for self-regulation that let me regain my vital balance and restored me to sanity. This capacity for self-regulation holds the key for our modern survival—survival beyond the brutal grip of anxiety, panic, night terrors, depression, physical symptoms and helplessness that are the earmarks of prolonged stress and trauma. However, in order to experience this restorative faculty, we must develop the capacity to face certain uncomfortable and frightening physical sensations and feelings without becoming overwhelmed by them. This book is about how we develop that capacity.

The shaking and trembling I experienced while lying on the ground and in the ambulance are a core part of the innate process that reset my nervous system and helped restore my psyche to wholeness. Without it I would have surely suffered dearly. Had I not been aware of the vital purpose of my body’s strange and strong sensations and gyrations, I might have been frightened by these powerful reactions and braced against them. Fortunately, I knew better.

I once described, to Andrew Bwanali, park biologist of the Mzuzu Environmental Center in Malawi, Central Africa, the spontaneous shaking, trembling and breathing that I and thousands of my therapy clients have exhibited in sessions as they recover from trauma. He nodded excitedly, then burst out, “Yes … yes … yes! This is true. Before we release captured animals back into the wild, we try to be sure that they have done just what you have described.” He looked down at the ground and then added softly, “If they have not trembled and breathed that way [deep spontaneous breaths] before they are released, they will likely not survive in the wild … they will die.” His comment reinforces the importance of the ambulance paramedic’s questioning the routine suppression of these reactions in medical settings.

We frequently shake when we are cold, anxious, angry or fearful. We may also tremble when in love or at the climax of orgasm. Patients sometimes shake uncontrollably, in cold shivers, as they awake from anesthesia. Wild animals often tremble when they are stressed or confined. Shaking and trembling reactions are also reported during the practices of traditional healing and spiritual pathways of the East. In Qigong and Kundalini yoga, for example, adepts who employ subtle movement, breathing and meditation techniques may experience ecstatic and blissful states accompanied by shaking and trembling.

All of these “tremblings,” experienced in diverse circumstances and having a multiplicity of other functions, hold the potential for catalyzing authentic transformation, deep healing and awe. Although the fearful trembling of anxiety does not in itself ensure a resetting and return to equilibrium, it can hold its own solution when guided and experienced in the “right way.” The distinguished Jungian analyst Marie-Louise von Franz notes: “The divine psychic core of the soul, the self, is activated in cases of extreme danger.”3 And, in the Bible, it is said that “God is found where you have trembled.”

What do all of these involuntary shakes and shivers have in common? Why do we quake when frightened or tremble in anger? Why do we quiver at sexual climax? And what might be the physiological function of trembling in spiritual awe? What is the commonality of all these shivers and shakes, quivers and quakes? And what have they to do with transforming trauma, regulating stress and living life to its fullest?

These gyrations and undulations are ways that our nervous system “shakes off” the last rousing experience and “grounds” us in readiness for the next encounter with danger, lust and life. They are mechanisms that help restore our equilibrium after we have been threatened or highly aroused. They bring us back down to earth, so to speak. Indeed, such physiological reactions are at the core of self-regulation and resilience. The experience of emergent resilience gives us a treasure beyond imagination. In the words of the ancient Chinese text, the I Ching,

The fear and trembling engendered by shock comes to an individual at first in such a way that he sees himself placed at a disadvantage … this is only transitory. When the ordeal is over, he experiences relief, and thus the very terror he had to endure at the outset brings good fortune in the long run.4

Learning to live through states of high arousal (no matter what their source) allows us to maintain equilibrium and sanity. It enables us to live life in its full range and richness—from agony to ecstasy. The intrinsic relationship of these spontaneous autonomic responses to the broad phenomenon of resilience, flow and transformation is a central theme of this book.

When, on the other hand, these “discharges” are inhibited or otherwise resisted and prevented from completion, our natural rebounding abilities get “stuck.” Being stuck, after an actual or perceived threat, means that one is likely to be traumatized or, at least, to find that one’s resilience and sense of OK-ness and belonging in the world have been diminished. Again, in the prescient words of the I Ching:

This pictures a situation in which a shock endangers a man and he suffers great losses. Resistance would be contrary to the movement of the time and for this reason unsuccessful.5

On that sunny winter morning of my accident, I was able—with the help of the kind pediatrician—to allow those physiological processes to complete moment-by-moment, moving time forward and releasing the highly charged “survival energy” lurking in my body and seeking its intended expression. This immediate emotional and “physical” first-aid prevented me from getting “stuck,” or locked in a vicious cycle of suffering and disability. How did I know what to do, as well as what to avoid, in this extremely stressful and disorienting situation? The short answer is that I have learned to embrace and welcome, rather than to fear and suppress, the primitive trembles, shakes and spontaneous body movements. The longer answer takes me back to the beginning of my last forty years of professional life as a scientist, a therapist and a healer.

Diagram A This is a detailed depiction of the physiological pathways underlying the classic fight-or-flight response. The illustrator was the late Dr. Frank Netter, one of the foremost medical illustrators.

Diagram B This Netter illustration shows the intricate and robust relationship between the viscera and the brain. The dorsal vagus nerve (the tenth cranial nerve at the back/dorsal part of the brain stem) mediates the immobilization system. It acts upon most of the visceral organs. The (ventral/front) nucleus ambiguus mediates the social engagement system through its connections with the middle ear, face and throat.

* Tinbergen’s was for his study of animals in their natural environments, Lorenz’s for his study of imprinting and Von Frisch’s for his study of how the dance of honey bees communicates the location of pollen to the rest of the hive.

† Edward Blanchard and his colleagues questioned Shalev’s data. However, in their study the vast majority of subjects were women and were only subjects who had sought treatment. Women tend to have more of a “freezing” stress response associated with the vagus nerve (which lowers heart rate)—in contrast to men, who tend to have a dominant sympathetic adrenal response. See Blanchard, E., et al. (2002). Emergency Room Vital Signs and PTSD in a Treatment Seeking Sample of Motor Vehicle Accident Survivors. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 15 (3), 199–204.

‡ These varied reactions included shaking, trembling and the restoration of biological defensive and orienting responses (including head and neck movements and the protective bracing of my arms and hands to protect my head).