Fear is the mind killer. Fear is the little death that brings total obliteration.

I will face my fear. I will permit it to pass over me and through me.

And when it has gone past me, I will turn to see fear’s path.

Where the fear has gone there will be nothing. Only I will remain.

—Dune by Frank Herbert

If you do not understand the nature of fear, you will never find fearlessness.

—Shambhala Buddhism

In the previous chapter we explored just how experimental animals and humans become trapped in fear-dominated paralysis; and, thus, how they become traumatized. In this chapter, I introduce the “antidote” for trauma: the core biological mechanisms that therapists must be aware of and able to elicit in their clients in order to assist in resolving their traumatic reactions. The engaging of these biological processes is equally essential whether treating the acute phase immediately following threatening and overwhelming incidents, such as rape, accidents and disasters, or in transforming chronic PTSD.

Until the core physical experience of trauma—feeling scared stiff, frozen in fear or collapsing and going numb—unwinds and transforms, one remains stuck, a captive of one’s own entwined fear and helplessness. The sensations of paralysis or collapse seem intolerable, utterly unacceptable; they terrify and threaten to entrap and defeat us. This perception of seemingly unbearable experiences leads us to avoid and deny them, to tighten up against them and then split off from them. Resorting to these “defenses” is, however, like drinking salt water to quench extreme thirst: while they may give temporary relief, they only make the problem drastically worse and are, over the long haul, counterproductive. In order to unravel this tangle of fear and paralysis, we must be able to voluntarily contact and experience those frightening physical sensations; we must be able to confront them long enough for them to shift and change. To resist the immediate defensive ploy of avoidance, the most potent strategy is to move toward the fear, to contact the immobility itself and to consciously explore the various sensations, textures, images and thoughts associated with any discomfort that may arise.

When working with traumatic reactions, such as states of intense fear, Somatic Experiencing®* provides therapists with nine building blocks. These basic tools for “renegotiating” and transforming trauma are not linear, rigid or unidirectional. Instead, in therapy sessions, these steps are intertwined and dependent upon one another and may be accessed repeatedly and in any order. However, if this psychobiological process is to be built on firm ground, Steps 1, 2 and 3 must occur first and must follow sequentially. Thus, the therapist needs to:

1. Establish an environment of relative safety.

2. Support initial exploration and acceptance of sensation.

3. Establish “pendulation” and containment: the innate power of rhythm.

4. Use titration to create increasing stability, resilience and organization. Titration is about carefully touching into the smallest “drop” of survival-based arousal, and other difficult sensations, to prevent retraumatization.

5. Provide a corrective experience by supplanting the passive responses of collapse and helplessness with active, empowered, defensive responses.

6. Separate or “uncouple” the conditioned association of fear and helplessness from the (normally time-limited but now maladaptive) biological immobility response.

7. Resolve hyperarousal states by gently guiding the “discharge” and redistribution of the vast survival energy mobilized for life-preserving action while freeing that energy to support higher-level brain functioning.

8. Engage self-regulation to restore “dynamic equilibrium” and relaxed alertness.

9. Orient to the here and now, contact the environment and reestablish the capacity for social engagement.

After my accident, the first inkling my body had of being other than profoundly helpless and disoriented was when the pediatrician came and sat by my side. As simple as this seems, her calm, centered presence gave me a slight glimmer of hope that things might turn out OK. Such soothing support in the midst of chaos is a critical element that trauma therapists must provide for their unsettled and troubled clients. This truly is the starting point for one’s return to equilibrium. The therapist must, in other words, help to create an environment of relative safety, an atmosphere that conveys refuge, hope and possibility. For traumatized individuals, this can be a very delicate task. Fortunately, given propitious conditions, the human nervous system is designed and attuned both to receive and to offer a regulating influence to another person.53 Thankfully, biology is on our side. This transference of succor, our mammalian birthright, is fostered by the therapeutic tone and working alliance you create by tuning in to your client’s sensibilities.

With the therapist’s calm secure center, relaxed alertness, compassionate containment and evident patience, the client’s distress begins to lessen. However minimally, his or her willingness to explore is prompted, encouraged and owned. While resistance will inevitably appear, it will soften and recede with the holding environment created by the skilled therapist. One possible roadblock, however, happens between sessions; when they are without their therapist’s calm, regulating presence, clients may feel raw and thrown back into the lion’s den of chaotic sensations when exposed to the same triggers that overwhelmed them in the first place. The therapist who provides only a sense of safety (no matter how effectively) will only make the client increasingly dependent—and thus will increase the imbalance of power between therapist and client. To avoid such sabotage, the next steps are aimed at helping the client move toward establishing his or her own agency and capacity for mastering self-soothing and feelings of empowerment and self-regulation.

Traumatized individuals have lost both their way in the world and the vital guidance of their inner promptings. Cut off from the primal sensations, instincts and feelings arising from the interior of their bodies, they are unable to orient to the “here and now.” Therapists must be able to help clients navigate the labyrinth of trauma by helping them find their way home to their bodily sensations and capacity to self-soothe.

To become self-regulating and authentically autonomous, traumatized individuals must ultimately learn to access, tolerate and utilize their inner sensations. It would, however, be unwise to have one attempt a sustained focus on one’s body without adequate preparation. Initially, in contacting inner sensations, one may feel the threat of a consuming fear of the unknown. Or, premature focus on the sensations can be overwhelming, potentially causing retraumatization. For many wounded individuals, their body has become the enemy: the experience of almost any sensation is interpreted as an unbidden harbinger of renewed terror and helplessness.

To solve this perplexing situation, a therapist who (while engaging in initial conversation) notices a momentary positive shift in a client’s affect—in facial expression, say, or a shift in posture—indicating relief and brightness, can seize the opportunity and try to direct the client toward attending to her sensations. “Touching in” to positive experiences gradually gives a client the confidence to explore her internal bodily landscape and develop a tolerance for all of her sensations, comfortable and uncomfortable, pleasant and unpleasant.

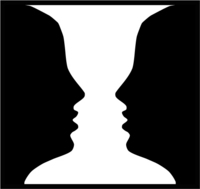

The client can now begin to allow the underlying disowned sensations—especially those of paralysis, helplessness and rage—to emerge into consciousness. She develops her experience of agency by choosing between the two opposing states: resistance/fear and acceptance/exploration. With a gentle rocking back and forth, oscillating between resistance and acceptance, fear and exploration, the client gradually sheds some of her protective armoring. The therapist guides her into a comforting rhythm—a supported shifting between paralyzing fear and the pure sensations associated with the immobility. In Gestalt psychology, these back-and-forth movements between two different states are described as figure/ground alternations (see Figure 5.1). This shifting, in turn, reduces fear’s grip and allows more access to the quintessential and unencumbered (by emotion) immobility sensations. This back-and-forth switching of attention (between the fear/resistance and the unadulterated physical sensations of immobility) deepens relaxation and enhances aliveness. It is the beginning of hope and the acquiring of tools that will empower her as she begins to navigate the interoceptive (or the direct felt experiencing of viscera, joints and muscles) landscape of trauma and healing. These skills lead to a core innate transformative process: pendulation.

Figure and Ground Perception

Figure 5.1 This figure demonstrates the alternation of figure and ground perception. Do you see the vase or the face? Keep looking. Now what do you see now? You will probably notice that the vase and face alternate but cannot be perceived at the same time. This is a useful concept in understanding how fear is uncoupled from immobility. When one experiences pure immobility, one cannot (like vase and face) also feel fear at the same time. This facilitates expansion and the gradual discharge of activation shown in Figure 5.2.

Expecting the worst, you look, and instead, here’s the joyful face you’ve been wanting to see.

Your hand opens and closes and opens and closes.

If it were always a fist or always stretched open,

you would be paralyzed.

Your deepest presence is in every small contracting and expanding.

The two as beautifully balanced and coordinated as birdwings.

—Rumi (1207–1273)

All God’s children got rhythm, who could ask for anything more?

—Porgy and Bess

While trauma is about being frozen or stuck, pendulation is about the innate organismic rhythm of contraction and expansion. It is, in other words, about getting unstuck by knowing (sensing from the inside), perhaps for the first time, that no matter how horrible one is feeling, those feelings can and will change. Without this (experienced) knowledge, a person in a state of “stuckness” does not want to inhabit his or her body. In order to counter the seemingly intractable human tendency to avoid horrible and unpleasant sensations, effective therapy (and the promotion of resilience in general) must offer a way to face the dragons of fear, rage, helplessness and paralysis. The therapist must inspire trust that their clients will not be trapped and devoured by first giving them a little “taste treat” of a pleasant internal experience. This is how our clients move toward self-empowerment. Confidence builds with the skill of pendulation.

One surprisingly effective strategy in dealing with difficult sensations involves helping a person find an “opposite” sensation: one located in a particular area of the body, in a particular posture, or in a small movement; or one that is associated with the person’s feeling less frozen, less helpless, more powerful and/or more fluid. If the person’s discomfort shifts even momentarily, the therapist can encourage him to focus on that fleeting physical sensation and so bring about a new perception; one where he’s discovered and settling on an “island of safety” that feels, at the very least, OK. Discovering this island contradicts the overarching feelings of badness, informing the person that somehow the body may not be the enemy after all. It might actually be grasped as an ally in the recovery process. When enough of these little islands are found and felt, they can be linked into a growing landmass, capable of withstanding the raging storms of trauma. Choice and even pleasure become a possibility with this growing stability as new synaptic connections are formed and strengthened. One gradually learns to shift one’s awareness between regions of relative ease and those of discomfort and distress.

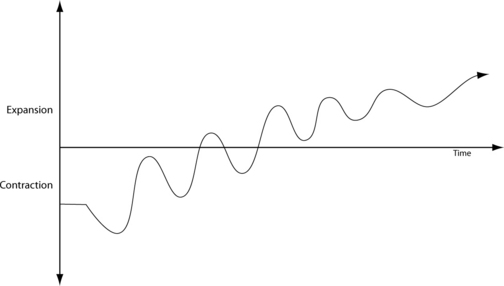

This shifting evokes one of the most important reconnections to the body’s innate wisdom: the experience of pendulation, the body’s natural restorative rhythm of contraction and expansion that tells us that whatever is felt is time-limited … that suffering will not last forever. Pendulation carries all living creatures through difficult sensations and emotions. What’s more, it requires no effort; it is wholly innate. Pendulation is the primal rhythm expressed as movement from constriction to expansion—and back to contraction, but gradually opening to more and more expansion (see Figure 5.2). It is an involuntary, internal rocking back and forth between these two polarities. It softens the edge of difficult sensations such as fear and pain. The importance of the human ability to move through “bad” and difficult sensations, opening to those of expansion and “goodness,” cannot be overstated: it is pivotal for the healing of trauma and more generally, the alleviation of suffering. It is vital for a client to know and experience this rhythm. Its steady ebb and flow tell you that, no matter how bad you feel (in the contraction phase), expansion will inevitably follow, bringing with it a sense of opening, relief and flow. At the same time, too rapid or large a magnitude of expansion can be frightening, causing a client to contract precipitously against the expansion. Hence, the therapist needs to moderate the scale and pace of this rhythm. As clients perceive that movement and flow are a possibility, they begin to move ahead in time by accepting and integrating current sensations that had previously overwhelmed them.

Figure 5.2 This figure describes the cycle of expansion and contraction through the process of pendulation. This vital awareness lets people learn that whatever they are feeling will change. The perception of pendulation guides the gradual contained release (discharge) of “trauma energies” leading to expansive body sensations and successful trauma resolution.

Let’s look at three universal situations that register this innate capacity of pendulation to restore feelings of relief and life flow: (1) We have all watched the inconsolable anguish of a child who, after a nasty fall, runs screaming to its mother and collapses in her arms. After a short time, the child begins to orient back out to the world, then seeks a moment’s return to its safe haven (perhaps through a glance back at mother or a connection through touch); and then, finally, returns to play as if nothing ever happened. (2) Consider the adult who is struck down by the gut-wrenching reaction to the sudden loss of a loved one. One may collapse, feeling that this experience will go on forever, resulting in one’s own death. Grieving can stretch out for quite a long time, but there is a clear ebb and flow in the tide of anguish. Gradually the rhythm of acceptance and pain yields a calming release and a return to life. (3) Finally, recall the last time you were driving and experienced a shockingly close call with disaster. Your nerves were raw with fear (hair standing on end) and rage, and your heart was pounding wildly, ready to explode in your chest. Then a wave of relief reminded you that you haven’t been catapulted into the horror of an accident. This moment of relief is usually followed by a second “flashback” of the near miss, which provokes another round of lessened startle, followed by yet another wave of restorative relief. This reparative rhythm occurs involuntarily, usually in the shadow of awareness, thankfully allowing one to focus on the task at hand. Thus, pendulation allows you to recover your balance and return to life’s moment-to-moment engagement.

When this natural resilience process has been shut down, it must be gently and gradually awakened. The mechanisms that regulate a person’s mood, vitality and health are dependent upon pendulation. When this rhythm is experienced, there is, at least, a tolerable balance between the pleasant and the unpleasant. People learn that whatever they are feeling (no matter how horrible it seems), it will last only seconds to minutes. And no matter how bad a particular sensation or feeling may be, knowing that it will change releases us from a sense of doom. The brain registers this new experience by tuning down its alarm/defeat bias. Where before, there was overwhelming immobility and collapse, the nervous system now finds its way back toward equilibrium. We cease to perceive everything as dangerous, and gradually, step by step, the doors of perception open to new possibilities. We become ready for the next steps.

Steps 3 and 4—pendulation and titration—together form a tightly-knit dyad that allows individuals to safely access and integrate critical survival-based, highly energetic states. Together, they allow trauma to be processed without overwhelm, and hence the individual is not retraumatized.

In Steps 5, 6 and 7, the gradual restoration of active defensive and protective responses—along with the carefully calibrated termination of the immobility reaction is accomplished. This, along with the discharge of bound energy, reduces the hyperarousal. Together these steps lie at the heart of transforming trauma. In particular, the egress from immobility is associated with intense arousal-based sensations, along with the powerful emotions of rage and frantic, fearful flight. This is the reason the process of trauma release must be worked in tiny increments.

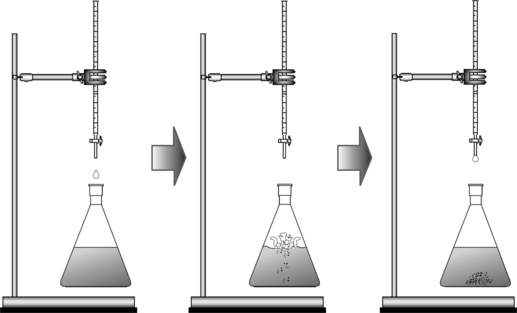

I use the term titration to denote the gradual, stepwise process of trauma renegotiation. This process operates like certain chemical reactions. Consider two glass beakers, one filled with hydrochloric acid (HCl) and the other with lye (NaOH). These extremely corrosive substances (the acid and the base, respectively) would cause severe burning if you were to place your finger in either beaker; indeed, if you were to leave that finger there for a few moments, it would simply dissolve since both of these chemicals are so caustic. Naturally, you would want to make them safe by neutralizing them; and, if you knew a little chemistry, you might mix them together to get a harmless mixture of water and common table salt, two of the basic building blocks of life. This reaction is written HCl + NaOH = NaCl + H20. If you simply poured them together, you would get a massive explosion, surely blinding yourself and any other individuals in the lab. On the other hand, if you skillfully use a glass valve (a stopcock), you could add one of the chemicals to the other one single drop at a time. And with each drop there would be a small “Alka-Seltzer fizzle,” but soon all would be calm. With each drop the same minimal reaction would repeat (see Figure 5.3). Finally, after a certain number of drops, both water and crystals of salt would begin to form. With several titrations, you would inevitably get the same neutralizing chemical reaction, but without the explosion. This is the effect that we want to achieve in resolving trauma: when dealing with potentially corrosive forces, therapists must somehow neutralize those sensations of intense “energy” and the primal emotional states of rage and non-directed flight without unleashing an explosive abreaction.

Titration

Figure 5.3 Titration in the chemistry lab is a way of combining two corrosive and potentially explosive substances in a controlled mixing that transforms the reactants gradually.

During my accident, as I was propelled into the windshield of the car, my arm stiffened to ward off the impact to my head. The amount of energy that goes into such a protective response is vast; muscles stiffen to maximal exertion to fend off a lethal blow. Also, at the moment my shoulder smashed into the glass and I was propelled into the air and onto the road, my body went limp.

When your muscles “give up” like that and collapse, you feel helpless and defeated. However, underneath that collapse, those flaccid (hypotonic) muscles still carry the signals to protect you even though they have “lost” their power, liveliness and ability to do so.

Our human sensorimotor memory is poised and ready to carry out its marching orders to champion our protection and safety. In my case, with interoceptive awareness, the active bracing pattern was gradually restored, and energy began to return to my arms. I allowed my muscles to do what they had “wanted” to do and were prepared to do in the moment prior to impact before they collapsed into helplessness. Bringing that into consciousness allowed me to experience a deepening sense of empowerment. Similarly, twenty-four-year-old Nancy (my very first trauma client from Chapter 2) and I discovered, unwittingly, that (rather than continuing to feel overpowered and overwhelmed by the surgeons as she had at age four), she could now escape from being held down and terrorized. These new experiences contradicted and repaired both of our experiences of helpless terror.

Briefly, the way these active self-protective responses are reestablished is as follows: Specific tension patterns (as experienced through interoceptive awareness) “suggest” particular movements, which then can express themselves in minute or micro-movements. The positions that my arms and hands spontaneously and powerfully assumed during the accident had protected my head from smashing into the windshield and then from being cracked open on the pavement. Later, when I was in the ambulance, I revisited these instinctual reflexive movements and expanded them through sensation awareness—a process that allowed me to consciously experience the activation of muscle fibers as my body prepared for movement. These actions had previously been incomplete and remained nonconscious. By slamming forcefully, first into the windshield and then onto the pavement, these muscular reflexes had been truncated, leaving me with collapsed and constricted muscles and a vast reservoir of latent energy. Instead of feeling helpless and victimized by this dreadful event, I created a powerful sense of agency and mastery. In addition, the restoration of defensive responses has the effect of automatically titrating the energies of rage. In other words, the explosive energy that would be expressed as rage and non-directed flight was now channeled into effective, directed healthy aggression.

Empowerment derives directly from expelling the physical attitude of defeat and helplessness and restoring the biologically meaningful active defense system—that is, the embodied triumph of successful protection and the visceral actuality of competency. Such renegotiation (as we shall see in Step 6) also helps to dissolve the entrenched guilt and self-judgment that may be byproducts of helplessness and repressed/dissociated rage. By accessing an active and powerful experience, passivity of paralysis and collapse is countered.

Because of the central importance of restoring these lost (rather, misplaced) instinctive active responses in healing trauma, I will—at the risk of repetition—address this subject from a slightly different angle. It can be said that the experience of fear derives from the primitive responses to threat where escape is thwarted (i.e., in some way—actual or perceived—prevented or conflicted).54 Contrary to what you might expect, when one’s primary responses of fight-or-flight (or other protective actions) are executed freely, one does not necessarily experience fear, but rather the pure and powerful, primary sensations of fighting or fleeing. Recall, the response to threat involves an initial mobilization to fight or flee. It is only when that response fails that it “defaults” to one’s freezing or being “scared stiff” or to collapsing helplessly.

In my case, in the ambulance, it was in my limbs—in the micro-movements of my arms rising upward to protect my head from mortal injury—that I first felt an opposite experience that contradicted my sensation of helplessness. For Nancy, it was her legs running to escape the doctor’s surgical knife. In both cases, consciously feeling our way through these active self-protective reflexes with precision brought us the physical sense of agency and power. Together, these experiences countered our feelings of overwhelming helplessness. Step by step, our bodies learned that we were not helpless victims, that we had survived our ordeals, and that we were intact and alive to the core of our beings. Along with instilling active defensive responses (which reduces fear), individuals learn that when they experience the physical sensations of paralysis, it is with less and less fear—each time trauma loosens its grip. With such a body-based epiphany, the mind’s interpretation of what happened and the meaning of it to one’s life and who one is shifts profoundly.

My clinical observations, drawn from more than four decades of work with thousands of clients, have led me to the solid understanding that the “physio-logical” ability to go into, and then come out of, the innate (hard-wired) immobility response is the key both to avoiding the prolonged debilitating effects of trauma and to healing even entrenched symptoms.55 Basically, this is done by separating fear and helplessness from the (normally time-limited) biological immobility response as described in Chapter 4. For a traumatized individual, to be able to touch into his or her immobility sensations, even for a brief moment, restores self-paced termination and allows the “unwinding” of fear and freeze to begin.

Of equal importance in resolving trauma is therapeutic restraint in not allowing the unwinding to occur precipitously. As with the nontitrated chemical reaction, abrupt decoupling can be explosive, frightening and potentially retraumatizing to the client. Through titration, the client is gradually led into and out of the immobility sensations many times, each time returning to a calming equilibrium (the “Alka-Seltzer fizzle”). In exiting from immobility, there is an “initiation by fire”; the intense energy-packed sensations that are biologically coupled with undirected flight and rage-counterattack are released. Understandably, people commonly fear both entering and exiting immobility, especially when they are not aware of the benefit of doing so. Let us look more deeply into these fears.

The fear of entering immobility: We avoid experiencing the sensations of immobility because of how powerful they are and how helpless and vulnerable they make us feel. Some of these even mimic the death state. When you consider how the thought of something as routine as being compelled to sit rigidly still in the dentist’s chair can cause you to wince, you begin to understand the challenge of voluntarily entering immobility mode. You may anticipate the pain of being trapped with no way to escape. For anxious or traumatized individuals, having to lie immobile during an MRI or CT scan can be downright terrifying. For children, these procedures may be vastly more difficult. Sitting quietly at one’s desk, unable to move for hours at a stretch, is a challenge for any youngster. For an anxious or “sensitive” child, it can be unbearable, perhaps even contributing to attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. This may be especially true for children who have had to undergo immobilizing procedures, such as when casts or metal braces are required for orthopedic correction of hips, legs, ankles or feet during the developmental stage when a child would normally be learning how to walk, run and explore the world.

Even adults who meditate often struggle with sitting still. Those few fortunate ones who can crawl into a warm bed, lie absolutely still, and drift quickly off into a restorative sleep are bestowed a most precious blessing. However, for many (perhaps even a majority), bedtime is often fraught with anxiety. It can become a nightmare in itself. In frustration, you may try to lie still while “counting sheep.” Mind spinning, you are unable to let go and surrender into Morpheus’s waiting arms. And then when some people awaken during (or shortly after) REM sleep, their bodies are still literally paralyzed by the neurological mechanisms designed to inhibit running or fighting (or even actively moving) in a dream for self-protection and prevention against hurting someone else. Waking up from this normal “sleep paralysis” can be terrifying, particularly when people experience themselves detaching from their bodies, a frequent component of immobility. For others, the sleep-induced REM paralysis is a curious, enjoyable, even “mystical,” out-of-body experience. For those who perceive this detaching from their bodies as terrifying, panic reactions are typical. In traumatized people, fear-potentiated immobility is their wrenching companion, day and night.

Although avoidance of immobility is understandable, it has a price. Whatever experiences you turn away from, your brain-body registers as dangerous; or colloquially, “that which we resist persists.” Thus, the time-honored expression, “time heals all wounds,” simply does not apply to trauma. In the short run, the suppression of immobility sensations appears (to our denial-biased mind) to keep the paralysis and helplessness at bay. However, in time, it becomes apparent that evasive maneuvers are an abject failure. This “sweeping under the rug” not only prolongs the inevitable, it often makes the eventual encounter with immobility even more frightening. It is as if the mind recognizes the extent of our resistance and in response interprets it as further evidence of peril. If, on the other hand, one is able to utilize the vital assistance of titration and pendulation, one can touch gently and briefly into that deathlike void without coming undone. Hence, the immobility response can move ahead in time toward its natural conclusion, self-paced termination.

The fear of exiting immobility: In the wild, when a prey animal has succumbed to the immobility response, it remains motionless for a time. Then, just as easily as it stopped moving, it twitches, reorients and scampers off. But if the predator has remained and sees its prey returning to life, the story has a very different ending. As the prey comes back to life and sees the predator standing ready for a second (and this time lethal) attack, it either defaults to all-out rage and counterattacks, or it attempts to run away in frantic non-directed flight. Thus reaction is wild and “mindless.” As I mentioned in Chapter 4, I once saw a mouse counterattack a cat that had been batting it about with its paws (bringing the mouse out of its stupor), and then scurry away, leaving the cat dazed, like Tom-cat in a Tom and Jerry cartoon. Just as the immobilized animal (in the presence of the predator) comes out ready for violent counterattack, so too does a traumatized person abruptly swing from paralysis and shutdown to hyper-agitation and rage. Fear of this rage and the associated hyper-intense sensations prevents a tolerable exit from immobility unless there is education, preparation, titration and guidance.

The fear of rage is also the fear of violence—both toward others and against oneself. The exiting of immobility is inhibited by the following double bind: to come back to life, one must feel the sensations of rage and intense energy. However, at the same time, these sensations evoke the possibility of mortal harm. This possibility inhibits sustained contact with the very sensations that bring relief from the experience of immobility, thereby leading to resolution. Recall the prescience of Kahlbaum (in Chapter 4) when he wrote in 1874: “In most cases catatonia is preceded by grief and anxiety and in general by depressive moods and affects aimed against the patient by himself.”56 Because the rage associated with the termination of immobility is both intense and potentially violent, frequently traumatized people inadvertently turn this rage against themselves in the form of depression, self-hatred and self-harm.

The inability to exit from the immobility response generates unbearable frustration, shame and corrosive self-hatred. The therapist must approach this Gordian knot carefully and untangle it through deliberate and careful titration, along with reliance on the experience of pendulation and a resolve to befriend intense aggressive sensations. In this way, the individual is able to move out of this “kill or be killed” counterattack bind. As one begins to open gradually to accepting one’s intense sensations, one enhances the capacity for healthy aggression, pleasure and goodness.

It is no surprise, then, that traumatized individuals constrict and brace against their rage as socialized animals. But let us look at the cumulative consequence of suppressing rage. Tremendous amounts of energy need to be exerted (on an already strained system) to keep rage and other primitive emotions at bay. This “turning in” of anger against the self, and the need to defend against its eruption, leads to debilitating shame, as well as to eventual exhaustion. This involution adds another layer to the complexity and seeming intransigence of the festering traumatic state. For these reasons, titration becomes even more crucial as a measure to interrupt this self-perpetuating “shame cycle.”

In the case of molestation and other forms of previous abuse, a substratum of self-reproach has already been laid beneath a later trauma during adulthood. Indeed, because immobility is experienced as a passive response, many molestation and rape victims feel tremendous shame for not having successfully fought their attackers. This perception and the overwhelming sense of defeat can occur regardless of the reality of the situation: the relative size of the attacker doesn’t matter; nor does the fact that the immobility might have even protected the victim from further harm or possibly death.† And I haven’t even included here the additional blanket of confusion and shame that occurs within the complex dynamics of secrecy and betrayal in the incestuous family.

As traumatized individuals begin to reown their sense of agency and power, they gradually come to a place of self-forgiveness and self-acceptance. They achieve the compassionate realization that both their immobility and their rage are a biologically driven, instinctual imperative and not something to be ashamed of as if it were a character defect. They own their rage as undifferentiated power and agency, a vital life-preserving force to be harnessed and used to benefit oneself. Because of its profound importance in the resolution of trauma, I’ll repeat myself: the fear that fuels immobility can be categorized, broadly, as two separate fears: the fear of entering immobility, which is the fear of paralysis, entrapment, helplessness and death; and the fear of exiting immobility, of the intense energy of the “rage-based” sensations of counterattack. Caught in this two-sided clamp (of entering and exiting), immobility repels its antidote implacably so that it seems impossible to break through it. However, when the skillful therapist assists clients in uncoupling the fear from the immobility by restoring “self-paced termination of immobility,” the rich reward is the client’s capability to move forward in time. This “forward experiencing” dispels fear, entrapment and helplessness by breaking this endless feedback loop of terror and paralysis.

As fear uncouples from the immobilization sensations, you may scratch your head and ask, where does the fear go? The short and confounding answer is that when titrated, “fear” simply does not really exist as an independent entity. The actual acute fear that occurred at the time of the traumatic event, of course, no longer exists. What happens, however, is that one provokes and perpetuates a new fear state (one literally frightens oneself) and becomes one’s own self-imposed predator by bracing against the residual sensations of immobility and rage. While paralysis itself need not actually be terrifying, what is frightening is our resistance to feeling paralyzed or enraged. Because we don’t know it is a temporary state, and because our bodies do not register that we are now safe, we remain stuck in the past, rather than being in present time. Pendulation helps to dissolve this resistance. We might best heed the words of the 1960s jug band Dan Hicks and his Hot Licks: “It’s me I’m afraid of … I won’t scare myself.”

During therapy, a graduated (titrated) progression or “forward moving of experiencing” keeps building on itself until the fear (now receding into the background) is eclipsed by a fully experienced immobility response. Frequently, one notices this physical sensation and acknowledges it with simple comments such as “I feel paralyzed, like I can’t move,” or “it feels like I am dead,” or even “it’s funny—I am dead and it doesn’t frighten me.” In addition, individuals may even experience blissful states similar to those reported in studies about near-death experiences. In exiting immobility, people may report that they feel “tingling vibrations all over my body” or “I feel deeply alive and real.” As the innate response of paralysis naturally resolves, sensations of “pure energy” are accepted; the individual opens into a mother lode of existential relief, transformative gratitude and vital aliveness. The mystic poet William Blake celebrated the intrinsic relationship between energy and the body: “The Body is a portion of the Soul discerned by the Senses, the chief inlet of the Soul in this age. Energy is the only life and is from the Body … and energy is pure delight.”

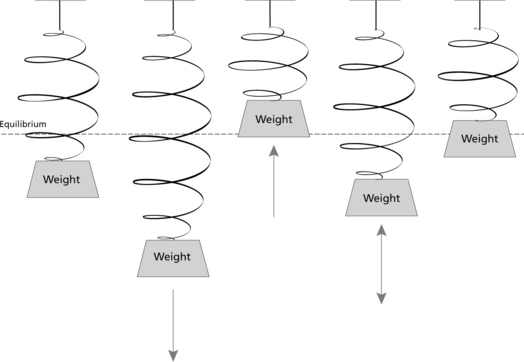

As one’s passive responses are replaced by active ones in the exit from immobility, a particular physiological process occurs: one experiences waves of involuntary shaking and trembling, followed by spontaneous changes in breathing—from tight and shallow to deep and relaxed. These involuntary reactions function, essentially, to discharge the vast energy that, though mobilized to prepare the organism to fight, flee or otherwise self-protect, was not fully executed. (See Chapter 1 for my own experience of such reactions after my accident, and Chapter 2 for Nancy’s as she discharged the arousal energy that had been bound up in ever-increasing symptoms since her early-childhood tonsillectomy.) Perhaps the easiest way to visualize the release of energy is through an analogy from physics. Imagine a spring fastened firmly to the ceiling above you. A weight is attached to the free end of the spring (see Figure 5.4). You reach up and pull the weight down toward you, stretching the spring and creating in it potential energy. Then as you release the spring, the weight oscillates up and down until all of the spring’s energy is discharged. In this way, the potential energy held in the spring is transformed into the kinetic energy of movement. The spring finally comes to rest when all the stored potential energy that has been converted to this kinetic energy is fully discharged.

Discharge of Traumatic Activation and Restoration of Equilibrium

Figure 5.4 Stretching the spring increases its potential energy. Releasing the spring transforms this potential into kinetic energy, where it is discharged and equilibrium restored.

Similarly, your muscles are energized (“stretched”) in preparation for action. However, when such mobilization is not carried out (whether fight-or-flight or some other protective response such as stiffening, twisting, retracting or ducking), then that potential energy becomes “stored” or “filed” as an unfinished procedure within the implicit memory of the sensorimotor system. When a conscious or unconscious association is activated through a general or specific stimulus, all of the original hormonal and chemical warriors reenergize the muscles as if the original threat were still operating. Later this energy can be released as trembling and vibration. Risking oversimplification, I can say that an amount of energy (arousal) similar to what was mobilized for fight-or-flight must be discharged, through effective action and/or through shaking and trembling. These can be dramatic as with Nancy (Chapter 2), while others are subtle. They may be expressed as gentle fasciculations and/or changes in skin temperature. Along with these autonomic nervous system releases, the self-protective and defensive responses that were incomplete at the time of the incident (and lie dormant as potential energy) are frequently liberated through micro-movements. These are almost imperceptible and are sometimes referred to as “premovements”). In this way, Steps 4 through 7 link together.

A direct consequence of discharge of the survival energy mobilized for fight-or-flight is the restoration of equilibrium and balance (as in the previous example of the spring). The nineteenth-century French physiologist Claude Bernard, considered the father of experimental physiology, coined the term homeostasis to describe “the constancy of the internal environment [milieu intérieur] as the condition for a free and independent life.”57 More than a hundred and fifty years later, this remains the underlying and defining principle for the sustenance of life. However, since equilibrium is not a static process, I will use the term dynamic equilibrium instead of homeostasis to describe what happens when the nervous system becomes hyperaroused in response to threat and is then “reset,” only to be aroused and reset once again. This continual resetting both restores the prethreat level of arousal and promotes the shifting state (process) of relaxed alertness. Over time this contributes to the building of a robust resilience. Finally, the interoceptive experience of equilibrium, felt in viscera and in your internal milieu, is the salubrious one of goodness: that is, the background sense that—whatever you are feeling at a given moment, however dreadful the upset or unpleasant the arousal—you have a secure home base within your organism.

Trauma could appropriately be called a disorder in one’s capacity to be grounded in present time and to engage, appropriately, with other human beings. Along with the restoration of dynamic equilibrium, the capacity for presence, for being in “the here and now,” becomes a reality. This occurs along with the desire and capacity for embodied social engagement.

The capacity for social engagement has powerful consequences for health and happiness. As young children we are wired to participate in the social nervous systems of our parents and to find excitement and joy in such engagement. In addition, fascination with the face of another person generalizes to the environment and to the wonder of “newness.” Colors become vibrant, while one perceives shapes and textures as though seeing them for the first time—the very miracle of life unfolding.

In addition, the social engagement system is intrinsically self-calming and is, therefore, built-in protection against one’s organism being “hijacked” by the sympathetic arousal system and/or frozen into submission by the more primitive emergency shutdown system. The social engagement branch of the nervous system is probably both cardioprotective and immuno-protective. This may be why individuals with strong personal affiliations live longer, healthier lives. They also maintain sharper cognitive skills into old age. Indeed, one study examining the effects of playing bridge in reducing dementia symptoms concluded that the main independent variable was socialization (rather than computational skills per se).‡ And, finally, to be engaged in the social world is not only to be engaged in the here and now, but also to feel a sense of both belonging and safety. So, ultimately freeing clients from the repercussive isolation that fear and immobility create has the potential of bringing not only freedom from debilitating symptoms, but also the potential to generate energy into the establishment of satisfying connections and relationships.

* This is a method I have developed over the past forty years.

† It is not clear when fighting or succumbing is the best survival strategy for rape. A dependent child experiencing molestation, however, really has little choice but to succumb.

‡ The so-called 90+ study at the University of Southern California began in 1981. It has included more than 14,000 people aged 65 and older and more than 1,000 aged 90 or older. Dr. Kawas, a senior investigator, concluded, “Interacting with people regularly, even strangers, uses easily as much brain power as doing puzzles, and it wouldn’t surprise me if this is what it’s all about.”