yoga sutra 2.3

avidyā-asmitā-rāga-dve a-abhiniveśa

a-abhiniveśa kleśa

kleśa

Misunderstanding (avidyā), confused sense of self (asmitā), habitual desire (rāga), habitual aversion (dve a), and profound fear (abhiniveśa) are the afflictions (kleśa)

a), and profound fear (abhiniveśa) are the afflictions (kleśa)

yoga sutra 2.4

avidyā k etram uttare

etram uttare ā

ā prasupta-tanu-vicchinna-udārā

prasupta-tanu-vicchinna-udārā ām

ām

The ground (k etra) in which all afflictions grow is misunderstanding (avidyā). These afflictions can be dormant (prasupta), weak (tanu), truncated (vicchinna), or fully mature and reproducing (udāra)

etra) in which all afflictions grow is misunderstanding (avidyā). These afflictions can be dormant (prasupta), weak (tanu), truncated (vicchinna), or fully mature and reproducing (udāra)

One of the ways to understand a new concept is through the use of metaphors, similes or analogies. We describe something new with reference to what we already know. Although no metaphor is perfect, by imposing previous understandings onto a new concept, we are able to see it (or some aspect of it) more clearly and our comprehension slowly grows. A common contemporary metaphor for the mind is a computer—people talk about “reprogramming” their minds, or “downloading” new ideas. Patañjali uses images from nature in tune with a more rural and agricultural culture.

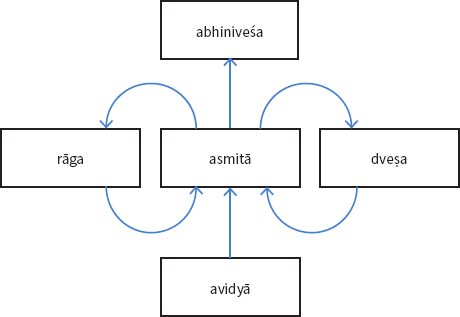

In YS 2.3, Patañjali simply lists the kleśa. Often translated as the “afflictions,” they run throughout life and are felt by all to various extents at different times. They are part of what it means to be alive. There is a very significant order to the list, and we can consider how these afflictions relate to each other and how they may manifest in the body. Arising out of misunderstanding (avidyā) comes a confused sense of self (asmitā) to which we cling. This is a misidentification with something ephemeral (like our current thoughts or feelings). By clinging to this feeling, we make an idol out of shadows; there is nothing permanent there. This feeling of self is perpetuated by habitual likes and dislikes (rāga and dve a respectively). Like an engine, rāga and dve

a respectively). Like an engine, rāga and dve a power the creation and continuity of identity and “feeling of me.” And running through all of these afflictions is a thread holding it all together: fear (abhiniveśa).

a power the creation and continuity of identity and “feeling of me.” And running through all of these afflictions is a thread holding it all together: fear (abhiniveśa).

In the next sūtra, YS 2.4, Patañjali goes on to describe the grounds for them all as a field (k etra). This is the field of misunderstanding (avidyā). Out of this field, other afflictions can grow and they, too, will have different stages in their lifecycle. Patañjali outlines four potential states of kleśa: dormant (prasupta), weak (tanu), truncated (vicchinna) or fully mature (udāra).

etra). This is the field of misunderstanding (avidyā). Out of this field, other afflictions can grow and they, too, will have different stages in their lifecycle. Patañjali outlines four potential states of kleśa: dormant (prasupta), weak (tanu), truncated (vicchinna) or fully mature (udāra).

When dormant and unseen (prasupta), they are like seeds in the ground. We think there is no problem, and yet—given the right conditions—a desire or an aversion can suddenly sprout and begin to show itself. As a seedling, the affliction is stretched thinly; it is weak (tanu). Here there is a “thin fuzz” of new growth, as the plants begin to develop. They are still easily managed, but their very presence shows that the soil contained seeds. The “kleśa plant” can continue to develop in the soil but before it reaches full maturation it can be cut down (vicchinna), or eclipsed. This is usually because another affliction overrides it: the desire for one thing (an ice cream) may be obscured because of a fear of something else (a spider in the way). By the time the plant becomes fully mature (udāra), we are no longer in control—it dominates us. Not only that, but having come into flower it can now spread its seeds to further perpetuate the cycle of karma. This fully mature stage of kleśa is extremely dangerous to our equilibrium; our decisions and actions are clouded by imbalances, and our minds inevitably become a breeding ground for yet more imbalance and affliction by propelling us into further actions based in kleśa.

We have already seen how the heart of the yoga project concerns the mind rather than the body, and the source of our suffering is our misunderstanding. It is extremely important to grasp that avidyā is misunderstanding, and not simply a lack of understanding or ignorance. Avidyā is far more profound than that; it is unconscious. We can be consciously ignorant of something—I know that I don't speak Spanish. This is not avidyā, because in a state of avidyā, we do not realize what we don't know. This is why avidyā is so difficult to detect—it is utterly unconscious and we are unaware of it. It is, in effect, our blind spot, and according to Patañjali, this blind spot is at the heart of our very existence (until we wake up). In this way, avidyā, and the resulting kleśa, permeate our lives.

yoga sutra 2.5

anitya-aśuci-du kha-anātmasu nitya-śuci-sukha-ātma-khyāti

kha-anātmasu nitya-śuci-sukha-ātma-khyāti avidyā

avidyā

Confusing the impermanent, the impure, the limited and nonessential with the permanent, the pure, the spacious and the essential is avidyā

There are many ways in which we can be confused or wrong, many potential arenas for our misunderstanding. But Patañjali defines avidyā in very specific terms by presenting four pairs of opposites—and in each we back the wrong horse. These are:

| I | II |

| anitya (impermanent) | nitya (permanent) |

| aśuci (impure) | śuci (pure) |

du kha (limited, restricted) kha (limited, restricted) |

sukha (unconfined space) |

| anātma (nonessential) | ātma (essence) |

Avidyā is a way of seeing. It is the specific misunderstanding that gives birth to the four other kleśa and it is defined as the confusion of the second column with the first. Thus, we project qualities from column II onto column I, thereby denying the reality of column I.

We give permanence (nitya) to the impermanent (anitya); we think the impure (aśuci) is pure (śuci); we believe the limited (du kha) is unlimited (sukha); and finally, we superimpose essence (ātma) onto what is simply not there (anātma). It is interesting that the word khyāti (embedded in ātmakhyāti) means both to “perceive” and to “declare.” In a state of avidyā, we perceive qualities of ātma or puru

kha) is unlimited (sukha); and finally, we superimpose essence (ātma) onto what is simply not there (anātma). It is interesting that the word khyāti (embedded in ātmakhyāti) means both to “perceive” and to “declare.” In a state of avidyā, we perceive qualities of ātma or puru a in our bodies and minds and declare this to be the case by acting as though it were true. This is misperception. The reason that this is avidyā is because our minds and bodies are subject to change and thus subject to gu

a in our bodies and minds and declare this to be the case by acting as though it were true. This is misperception. The reason that this is avidyā is because our minds and bodies are subject to change and thus subject to gu a. Because they change, decay and die, they are in the realm of prak

a. Because they change, decay and die, they are in the realm of prak ti, whereas what we are projecting onto our bodies and minds are the qualities of puru

ti, whereas what we are projecting onto our bodies and minds are the qualities of puru a.

a.

Each of the pairs is significant. The first pairing reminds us that there is nothing permanent in our experience. Not only does every cell of the body continuously change, but so do our thoughts, our feelings of who we are, our moods, our very perception of the world. Sometimes I feel like a good person, sometimes I feel bad! Confusing the impermanent for the permanent, we could sum up this first pair thus: we refuse to accept change.

Is there an implicit morality in the second pairing? Does Patañjali imply that we must “purify” our impure bodies through some kind of ascetic denial? We can consider our bodies (and minds) “impure” in so far as they need maintaining: they need cleaning and looking after. If they were inherently pure, they would need no maintenance. Moreover, we tend to cloak our fallibilities with “purity.” All too often, we deny or repress unwholesome feelings or motivations and thereby fail to acknowledge an aspect of our humanity. We are not perfect!1 We could sum up this second pair, of confusing the impure for the pure, thus: we refuse to accept our shadow.

We have translated du kha as “limited, or restricted” (space), while sukha is “unconfined space.” These are more commonly understood as “pain” and “joy” respectively, but du

kha as “limited, or restricted” (space), while sukha is “unconfined space.” These are more commonly understood as “pain” and “joy” respectively, but du kha is really about the pain, frustration or suffering that arises when we feel constricted or limited. Sukha is its opposite; it is the feeling of open, free and easy space. Interestingly, however, the feeling of too much space can be just as disorientating as too little. Too much choice, for example, can also be overwhelming.2 As incarnated beings, we necessarily have to exist within limits—we are to some extent confined by our physical limitations and these limitations increase as we grow older. What is important, however, is that form and structure (and therefore limits) need not be perceived as prison walls. The structure of a haiku or a sonnet define the poem's limits; once those limits have been understood and accepted, they can be used creatively and harnessed to become supports. However, if we rail against limits, misunderstand boundaries or think the world should be otherwise, we simply bang our heads on walls in unrealistic utopianism. We could sum up this third pair, of confusing du

kha is really about the pain, frustration or suffering that arises when we feel constricted or limited. Sukha is its opposite; it is the feeling of open, free and easy space. Interestingly, however, the feeling of too much space can be just as disorientating as too little. Too much choice, for example, can also be overwhelming.2 As incarnated beings, we necessarily have to exist within limits—we are to some extent confined by our physical limitations and these limitations increase as we grow older. What is important, however, is that form and structure (and therefore limits) need not be perceived as prison walls. The structure of a haiku or a sonnet define the poem's limits; once those limits have been understood and accepted, they can be used creatively and harnessed to become supports. However, if we rail against limits, misunderstand boundaries or think the world should be otherwise, we simply bang our heads on walls in unrealistic utopianism. We could sum up this third pair, of confusing du kha and sukha, thus: we refuse to accept our limits.

kha and sukha, thus: we refuse to accept our limits.

The final pair suggest that we give a solidity and form to something that is simply not there. Ascribing essence (ātma) to that which is not there (anātma) gives rise to defensiveness, hostility, and a feeling of being “up against the world.” In this state, we see our skin as the end of our territory, and everything inside that skin (including the thoughts and feelings that are produced by our current state of being) needs defending against the ravages of what lies outside. Ultimately, it's a losing battle. We deny the possibility that there is anything beyond our superficial understandings and cling to the idea that the reality we exist in is the only one possible. We could sum up this last pair, of confusing ātma and anātma, thus: we refuse to accept depth—and thus we are happy to be anaesthetised by the superficial.

The four aspects of avidyā can appear somewhat abstract and impenetrable, but by seeing them as four refusals3 we can see how they play out in our lives:

we refuse to accept change

we refuse to accept our shadow

we refuse to accept our limits

we refuse to accept depth.

These refusals appear unconsciously in our attitudes and motivations and thereby drive our actions without our awareness. Although shining a light on their presence may begin to lessen their impact, simply knowing about them is not necessarily enough: they are unconscious forces at the heart of how we think and act.

Patañjali asserts that until we fully wake up, kleśa will color our lives, and behind all kleśa is avidyā. We could go as far as to say that actually there is only one kleśa—avidyā—and these four are simply its various manifestations. Yoga's concern, therefore, is the clarification of avidyā.

yoga sutra 2.6

d g-darśana-śaktyo

g-darśana-śaktyo ekātmatā iva asmitā

ekātmatā iva asmitā

When the energy of the Seer becomes confused with the process of seeing, a false identity arises

Without a sense of self, life would not only be intolerable, it would be unlivable. We need to have an identity in order to interact with others, to give us perspective on our experiences and to coordinate the many functions of our body-mind. The term Patañjali uses for “sense of self” is asmitā, but it's important to appreciate that this has two forms: asmitā rūpa and asmitā kleśa, and only the latter is pathological. Asmitā rūpa4 simply means “the feeling of one's Self.” However, when we (mis)identify that feeling and become glued to concepts of who we are, this becomes a kleśa. So, in YS 2.6, Patañjali deepens his discussion of avidyā by clarifying how it manifests as asmitā kleśa. Asmitā kleśa is fundamentally a confusion. It is seeing two things as one: iva means “as if” and ekātmatā means “one (eka) essence (ātma).” Here, the power of the Seer (d g śakti) is confused with the faculty for perception (darśana śakti)—that is to say, with our senses and our minds. A “pseudo Self” is created from the very real feeling of being alive. By projecting identity onto thoughts and perceptions, the illusion of form and continuity crystallizes around mental fluctuations. Our work, our relationships, our likes and dislikes become who we think we are. Asmitā kleśa is a very serious state: it is a heavy burden which may manifest as a furrowed brow, hypersensitivity, and a feeling of discomfort, anxiety, arrogance or defensiveness in our own body.

g śakti) is confused with the faculty for perception (darśana śakti)—that is to say, with our senses and our minds. A “pseudo Self” is created from the very real feeling of being alive. By projecting identity onto thoughts and perceptions, the illusion of form and continuity crystallizes around mental fluctuations. Our work, our relationships, our likes and dislikes become who we think we are. Asmitā kleśa is a very serious state: it is a heavy burden which may manifest as a furrowed brow, hypersensitivity, and a feeling of discomfort, anxiety, arrogance or defensiveness in our own body.

a: Replaying our past desires and aversions

a: Replaying our past desires and aversions

yoga sutra 2.7

sukha-anuśayī rāga

Rāga is the desire to repeat previously pleasurable experiences

yoga sutra 2.8

du kha-anuśayī dve

kha-anuśayī dve a

a

Dve a is the desire to avoid previously painful experiences

a is the desire to avoid previously painful experiences

Just as not all feelings of self are pathological, so not all desires or aversions are problematic. The desire for water when we are thirsty, or the repulsion towards things which are dangerous to us, is natural and healthy. Patañjali talks about a specific type of desire and a specific form of aversion—these are called rāga and dve a respectively.

a respectively.

In some senses, rāga and dve a are opposites of one another. Common to both of them is the term anuśayī, which means “flowing on from” and implies a tendency towards repeating experiences. Rāga is defined as the desire to repeat pleasurable experiences, while dve

a are opposites of one another. Common to both of them is the term anuśayī, which means “flowing on from” and implies a tendency towards repeating experiences. Rāga is defined as the desire to repeat pleasurable experiences, while dve a is the attempt to avoid previously painful experiences. What makes them kleśa is that they are not based in present time, but in past conditioning. Even if we want something new, the desire is a replay of a past habit: we might want a new piece of technology, but the pattern of desire is the same old, same old. Rāga and dve

a is the attempt to avoid previously painful experiences. What makes them kleśa is that they are not based in present time, but in past conditioning. Even if we want something new, the desire is a replay of a past habit: we might want a new piece of technology, but the pattern of desire is the same old, same old. Rāga and dve a “replay” desires: they both arise from asmitā kleśa and also perpetuate it.

a “replay” desires: they both arise from asmitā kleśa and also perpetuate it.

Rāga can be seen as a form of addiction—many drug addicts have talked about how their addiction stems from the desire to repeat their very first experience of a drug. Unfortunately, this is a doomed venture: we cannot repeat it and feel the same way because we (and everything else) have changed. This is a replay that endeavors to take the experience out of the present, like trying to taste fruit we dreamed we ate. Although it may feel that we are giving ourselves what we desire (and thereby supporting ourselves), it is actually illusory. We trick ourselves into chasing after the unreachable.

In the same way, dve a is also out of the present time. Dve

a is also out of the present time. Dve a is a rerun of a previous unhappy experience and it shuts us down from the present moment because we are heavily conditioned by our prejudices against whatever stimulated our aversion in the first place. We may wish to avoid something—but in doing so we become trapped. While running away from our fears may reduce our anxiety momentarily, eventually we simply paint ourselves into a corner and have nowhere to hide. Dve

a is a rerun of a previous unhappy experience and it shuts us down from the present moment because we are heavily conditioned by our prejudices against whatever stimulated our aversion in the first place. We may wish to avoid something—but in doing so we become trapped. While running away from our fears may reduce our anxiety momentarily, eventually we simply paint ourselves into a corner and have nowhere to hide. Dve a is the illusion of really being free.

a is the illusion of really being free.

It is interesting to reflect on the nature of play. Play is an “as if” experience—it is both serious and also light. When children play, they are completely absorbed in the experience: it is their present. At its most profound, play takes us “out of time” and, in this sense, is unlike “replay,” which is very much in time. Thus sportsmen and women are so utterly engrossed in the present moment that thoughts of yesterday or tomorrow are irrelevant (indeed, such thoughts would interrupt the flow). We are not suggesting those in a “flow state of play” have permanently undermined asmitā, but we can say that at that moment, it is greatly reduced. Perhaps this is one of the reasons that sport, and indeed any experience of heightened presence (enthralled dancing, listening to music, singing) can feel so good: it takes us out of our habitual confined sense of self and opens us to a far more transcendent and spacious sense of Being. These experiences are “liberating.” One antidote therefore, to the seriousness of asmitā kleśa, and the replay of rāga and dve a is simply to play: be present, light of heart, and engaged.

a is simply to play: be present, light of heart, and engaged.

yoga sutra 2.9

svarasa-vāhī vidu o'pi samārū

o'pi samārū ha

ha abhiniveśa

abhiniveśa

Abhiniveśa is a clinging to the “feeling of oneself” and is experienced even by the wise

There is an instinctive reaction towards preservation of life against death. Our autonomic nervous systems quickly fire up when we are in danger—we gasp if our breathing is compromised, we flinch from something which burns, we fight to stay alive when there is a threat to life. As long as we are alive, this fear of death will operate at some level simply because it is hardwired in us. The traditional commentators of the Yoga Sūtra see abhiniveśa as exactly this fear of death. The word vāhī means “carrying” or “bearing”; svarasa is “one's own juice.” The first word of the sūtra, svarasavāhī, therefore means “holding (onto) one's vital fluid.”5 Abhiniveśa is defined as the “clinging to (this tendency)” and it affects everyone equally (samārū ha

ha )—even the highest sage, a vidu

)—even the highest sage, a vidu a

a .

.

Some say that because abhiniveśa is experienced by all, it means that kleśa are also fundamental to the embodied experience. Avidyā is certainly seen as a common experience for everyone who has yet to awaken to vidyā, but let us not confuse abhiniveśa with a generic autonomic reaction to danger or a general fear of death. Instead it can be understood as a very specific fear arising out of protecting a false identity. It is how we feel when we are so wedded to our own identity—our views, ideas and habits—that any change or threat provokes a profound fear and resistance. Abhiniveśa is the fear of letting go, of being challenged or destabilized. As long as there is avidyā, there will be asmitā, powered by rāga and dve a, and if there is asmitā, there will be abhiniveśa. Asmitā is like “constructing (and inhabiting) our castle”; abhiniveśa arises when we feel the threat of eviction!6

a, and if there is asmitā, there will be abhiniveśa. Asmitā is like “constructing (and inhabiting) our castle”; abhiniveśa arises when we feel the threat of eviction!6

Relationship between kleśa

As we have seen, the kleśa will not be dominant (udāra) all the time; it is quite possible, indeed probable, for the kleśa to be weak (tanu) or even dormant (prasupta) until circumstances conspire to push the kleśa into a more noticeable manifestation. However, importantly, we should acknowledge that these different levels of kleśa are natural—and sometimes kleśa will be overwhelming. This is not an indication of us failing or being “bad”; it is simply part of a natural cycle. And remember: things change and what is overwhelming now will once again retreat to a tanu or prasupta state in due course.

yoga sutra 2.10

te pratiprasava-heyā sūk

sūk mā

mā

These five kleśa are subtle and are overcome by a return to their original state

Yoga is sometimes described as “swimming upstream.” The very first limb of kriyā yoga is tapas7—that is, purifying actions that challenge us. Tapas requires us to go against our habitual patterns and to swim upstream. In using the term pratiprasava (the second word of the sūtra), Patañjali alludes to this concept since prati means “against” and prasava means “the flow.” We can therefore understand the term as a sort of backtracking, of retracing one's footsteps back to the source. From a traditional perspective, pratiprasava is the process of moving our attention from the most external and grossest parts of our being (our physical form, our senses) through progressively more subtle aspects (the various parts of our mind) until we have flooded the whole system with a clarity born of sattva.

“Returning to the source” is not historical. In other words, it is not about going back in time. Pratiprasava is not concerned with intra-psychic archaeology—digging around for clues in our earliest memories. A slightly unusual way of understanding this “returning to the source” is becoming present to this very moment, becoming aware of the right now. As we have seen, we can understand this presence as an antidote to kleśa, which are fueled by the endless replay of rāga and dve a. Becoming alive to the present moment is the opposite of “spinning out” into fears, desires, aversions and fortifying one's sense of entitlement. It is the simple and profound realization that we are here and now, and that kleśa are built upon avidyā—an elsewhere which, by disguising itself as reality, usurps it.

a. Becoming alive to the present moment is the opposite of “spinning out” into fears, desires, aversions and fortifying one's sense of entitlement. It is the simple and profound realization that we are here and now, and that kleśa are built upon avidyā—an elsewhere which, by disguising itself as reality, usurps it.

yoga sutra 2.1

dhyāna-heyā tadv

tadv ttaya

ttaya

Through meditation (dhyāna), the causes of afflictive mental activity (v tti) are overcome (heya)

tti) are overcome (heya)

What is the route to this elusive present moment? How do we swim upstream? Here, Patañjali equates the kleśa with their mental symptoms—the (citta) v tti—and states that the way to both understand and manage their effects is dhyāna (meditation). In dhyāna, we begin to settle the mind's activity by focusing on a single object (dhāra

tti—and states that the way to both understand and manage their effects is dhyāna (meditation). In dhyāna, we begin to settle the mind's activity by focusing on a single object (dhāra ā), and as that process stabilizes, the mind's tendency towards “spinning the wheel of kleśa” is reduced. The gravitational pull of the kleśa weakens as we reorient ourselves. Ultimately as we remain in the practice, dhyāna evolves into samādhi and profound insights arise as well as a loss of sense of self. The present moment shines and replaces the usual thoughts, distractions and feeling of “self-consciousness.”8

ā), and as that process stabilizes, the mind's tendency towards “spinning the wheel of kleśa” is reduced. The gravitational pull of the kleśa weakens as we reorient ourselves. Ultimately as we remain in the practice, dhyāna evolves into samādhi and profound insights arise as well as a loss of sense of self. The present moment shines and replaces the usual thoughts, distractions and feeling of “self-consciousness.”8

yoga and kleśa

yoga and kleśa

yoga sutra 2.17

dra

-d

-d śyayo

śyayo sa

sa yoga heya-hetu

yoga heya-hetu

Confusing the Seer and that which is seen is the cause of the suffering that is to be avoided

We have seen (in Chapter 4) how we can understand sa yoga as embodied avidyā. The state of sa

yoga as embodied avidyā. The state of sa yoga, as described by Patañjali in this sūtra, is thus a consequence of avidyā. This state can include how we hold ourselves, how we move, how we interact and even how we think. Fundamental to yoga is an understanding of space and difference; yoga is concerned with the creation of a space which enables a good relationship. Sa

yoga, as described by Patañjali in this sūtra, is thus a consequence of avidyā. This state can include how we hold ourselves, how we move, how we interact and even how we think. Fundamental to yoga is an understanding of space and difference; yoga is concerned with the creation of a space which enables a good relationship. Sa yoga is its opposite: space is compromised and boundaries become blurred.

yoga is its opposite: space is compromised and boundaries become blurred.

In any space that joins two principals—the space between bones in the body, between married couples, between children and parents, between body and mind—unwanted material can accumulate. In āyurveda, undigested material which is not expelled is called āma. As āma accumulates, it begins to overflow and circulates in the system, lodging itself wherever it finds a free space. Once it is has become embedded, it begins to compromise that space so that instead of a free relationship, it creates an unhealthy singularity. Although āma is generally considered a physical substance, we can think of a psychological and emotional equivalent. Undigested thoughts, feelings and experiences can also accumulate and lodge themselves in our system. Eventually, this unprocessed material can severely compromise the health of a relationship; the free space between the two principals becomes a confused space where the autonomy of each principal is lost and where identities become blurred. Pointing to the problem, each side blames the other.

In a healthy joint, two bones slide freely in relationship to one another, allowing the space between them to be uncomplicated. Where there is pathology, this space becomes compromised, manifesting as pain and limited movement. Toxins (unwanted material) restrict the space, creating discomfort or pain. In effect, the two bones are no longer able to work interdependently, but rather only work as one—when one moves the other is affected.

In the same way as bones or other parts of our bodies can become “stuck” together, so we can become “glued” to outdated ideas or perceptions that block us from seeing the reality of the present moment. We become fixed in our own preconceptions. And from an interpersonal perspective, a couple can become so used to each other that they no longer see each other for who they are. Accumulated and habitual ways of interacting block clear and fresh perception, and the relationship loses its vitality and becomes stale.

This state of confusion is called sa yoga—literally “complete joining in a confused way.” Just as avidyā can look like vidyā (because it is a wrong understanding rather than no understanding) so sa

yoga—literally “complete joining in a confused way.” Just as avidyā can look like vidyā (because it is a wrong understanding rather than no understanding) so sa yoga can look very much like yoga (because it is wrong relationship rather than no relationship). It is “yoga in disguise,” an attempt at maintaining a relationship which is failing because of the accumulated detritus of the past. What should not have been joined has become as one; two principals have become inseparable and confused. In the state of sa

yoga can look very much like yoga (because it is wrong relationship rather than no relationship). It is “yoga in disguise,” an attempt at maintaining a relationship which is failing because of the accumulated detritus of the past. What should not have been joined has become as one; two principals have become inseparable and confused. In the state of sa yoga, space is compromised, resulting in a feeling of restriction, loss of vitality and an inability to move or interact freely. This is du

yoga, space is compromised, resulting in a feeling of restriction, loss of vitality and an inability to move or interact freely. This is du kha.

kha.

Sādhana: Moving from sa yoga to viveka in body and breath

yoga to viveka in body and breath

The key principle of yoga which helps us overcome sa yoga is viveka: the ability to see things from both sides, to discern. Viveka is a fundamental requirement for yoga, and our initial steps on the path help us to cultivate this discriminating awareness. When we are ignorant about a particular subject, it is very difficult to make any judgments about that subject (although, of course, many people do!). Someone who knows nothing about jazz may be unable to distinguish the sound of Charlie Parker from that of John Coltrane. It is only through experience and practice (in this case, of listening) that we begin to develop an understanding of how, where and what to distinguish. As this understanding deepens, we are able to make finer and finer judgments, and so cultivate viveka.

yoga is viveka: the ability to see things from both sides, to discern. Viveka is a fundamental requirement for yoga, and our initial steps on the path help us to cultivate this discriminating awareness. When we are ignorant about a particular subject, it is very difficult to make any judgments about that subject (although, of course, many people do!). Someone who knows nothing about jazz may be unable to distinguish the sound of Charlie Parker from that of John Coltrane. It is only through experience and practice (in this case, of listening) that we begin to develop an understanding of how, where and what to distinguish. As this understanding deepens, we are able to make finer and finer judgments, and so cultivate viveka.

yoga in the body

yoga in the bodyWhen someone first comes to a yoga class, they are likely to have poor body awareness unless they have had training through another discipline like T'ai Chi, dance or Alexander Technique. Perhaps because our culture is so mental (in both senses of the word), many people are disconnected from their bodies and function like disembodied heads on trolleys. Bodies are something, as the educator Ken Robinson graphically put it, “to take you from one meeting to the next.”9 It is no surprise, therefore, that making subtle adjustments to the spine, or being aware of the movement of the shoulder blades, or noticing the relationship between the knees and the hips is a total mystery for the novice yoga practitioner. To begin with, sensations need to be fairly gross for them to register at all. This common experience for beginners is a form of sa yoga because everything seems to move together, but not in a harmonious or conscious way. The beginner's body often moves as a single block.

yoga because everything seems to move together, but not in a harmonious or conscious way. The beginner's body often moves as a single block.

The innovative body-mind therapist Moshé Feldenkrais often described unconscious movements that accompany conscious ones as “parasitic”: they “feed off” a host movement. As we refine our practice, we learn to inhibit these unconscious and unnecessary movements, which can confuse transmission of lines of force, making the body work harder because it is pulled in more than one direction. For example, if we bring our knees over the chest when we are lying down, we might find our chin lifting, thereby compressing the back of our necks, and our sacrum coming off the ground, resulting in a rounding of the lower back.

If the body is working against itself, the support for the movement is obscured and the direction becomes confused. By removing unnecessary twitches, tensions, or movements we are able to create a cleaner direction that enables clear transmission from a stable base.

This process is more akin to sculpture (the removal of unnecessary material to reveal an essence) than painting (in which something is created by being “built up”). The sa yoga of movement, therefore, is the unconscious and inefficient use of the body where true support for the movement is eclipsed, resulting in excess and unnecessary effort. The ability to simplify a movement, such that we create a stable base and then move in a clear direction, is to apply viveka in āsana.

yoga of movement, therefore, is the unconscious and inefficient use of the body where true support for the movement is eclipsed, resulting in excess and unnecessary effort. The ability to simplify a movement, such that we create a stable base and then move in a clear direction, is to apply viveka in āsana.

yoga in three polarities

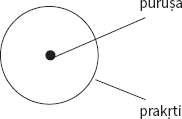

yoga in three polaritiesWe can poetically describe three polarities which, while not being exactly equivalent, do nonetheless have a certain thematic consistency. The first of these is simply the two fundamental principles of yoga and Sa khya: puru

khya: puru a and prak

a and prak ti (fig 8.1):

ti (fig 8.1):

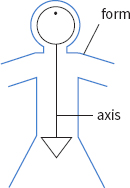

We are taking a bit of a liberty by representing puru a as a dot in a circle because, actually, it is out of time and out of space, and certainly not confined “within” prak

a as a dot in a circle because, actually, it is out of time and out of space, and certainly not confined “within” prak ti. However, with imagination we can see how this diagram represents one aspect of the polarity between the observer (puru

ti. However, with imagination we can see how this diagram represents one aspect of the polarity between the observer (puru a) and that which is observed (prak

a) and that which is observed (prak ti). At its most global and profound, sa

ti). At its most global and profound, sa yoga is exactly the confusion between these two polarities: this is the fundamental avidyā. It lies at the very heart of the philosophy of yoga and Sa

yoga is exactly the confusion between these two polarities: this is the fundamental avidyā. It lies at the very heart of the philosophy of yoga and Sa khya. As you practice, ask yourself: can you create the time and space to notice how the body moves and to observe, without becoming enmeshed?

khya. As you practice, ask yourself: can you create the time and space to notice how the body moves and to observe, without becoming enmeshed?

In the texts of Ha ha Yoga, another pair is introduced which reflects something of this initial polarity. This pair defines the vertical axis in the body: at the top is the head, symbolized by the moon (candra) and at the bottom is the pelvis, symbolized by the root (mūla) (fig 8.2 on page 161).

ha Yoga, another pair is introduced which reflects something of this initial polarity. This pair defines the vertical axis in the body: at the top is the head, symbolized by the moon (candra) and at the bottom is the pelvis, symbolized by the root (mūla) (fig 8.2 on page 161).

Candra is a synonym for the highest, most subtle part of the mind, called buddhi, whose function is to discriminate. In the yoga tradition, it is seen as that which reflects the light of puru a (just as the moon reflects the light of the sun). It is not exactly the same as puru

a (just as the moon reflects the light of the sun). It is not exactly the same as puru a, but it can be thought of as a sign—how the light and awareness of puru

a, but it can be thought of as a sign—how the light and awareness of puru a manifest in the body. At the other end is the pelvis, which contains the densest bone of our body, the sacrum. This end of the vertical axis is mūla, which literally means “root.” It contains our “tail” (the coccyx), which symbolizes our roots in humanity and even the animal kingdom—and is thus something of a reflection of prak

a manifest in the body. At the other end is the pelvis, which contains the densest bone of our body, the sacrum. This end of the vertical axis is mūla, which literally means “root.” It contains our “tail” (the coccyx), which symbolizes our roots in humanity and even the animal kingdom—and is thus something of a reflection of prak ti. The ascent through the vertical axis is thus a symbolic journey from the grossest aspects of the material world through to the most rarefied and subtle realms of spirit. Because they are two ends of the spine, how one end moves affects the other and consequently there is tremendous potential for unconscious or “parasitic” movement in the head or pelvis as one or the other moves. In our practice, can we become sensitive to the relationship between the movement of the head and the movement of the pelvis?

ti. The ascent through the vertical axis is thus a symbolic journey from the grossest aspects of the material world through to the most rarefied and subtle realms of spirit. Because they are two ends of the spine, how one end moves affects the other and consequently there is tremendous potential for unconscious or “parasitic” movement in the head or pelvis as one or the other moves. In our practice, can we become sensitive to the relationship between the movement of the head and the movement of the pelvis?

The vertical axis is two-dimensional, and it cannot exist alone in space. It needs a container to take it into three dimensions. We can further elaborate this essential polarity by contrasting the vertical axis and the form within which it abides (fig 8.3).

It is wrong to equate the axis with puru a, but in construing an imaginary line around which our form dances, we can say that something of puru

a, but in construing an imaginary line around which our form dances, we can say that something of puru a is reflected in the axis. Similarly, although the form is not pure prak

a is reflected in the axis. Similarly, although the form is not pure prak ti, it is what we can directly observe (the way we are in the world, how we hold ourselves and how we manifest), so it can be seen as a reflection of prak

ti, it is what we can directly observe (the way we are in the world, how we hold ourselves and how we manifest), so it can be seen as a reflection of prak ti. It is a useful exercise to practice āsana with full concentration on the axis, or full concentration on the form, and indeed sometimes with full concentration on their relationship.

ti. It is a useful exercise to practice āsana with full concentration on the axis, or full concentration on the form, and indeed sometimes with full concentration on their relationship.

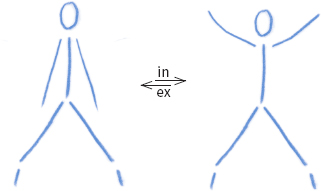

Try the simple sequence shown on page 162 (fig 8.4), first focusing on the axis, then the form, and finally on the relationship between the two.

At its most sophisticated, when yoga is really working, the axis is both supported by and a support for, the form; just as puru a is both supported by and a support for prak

a is both supported by and a support for prak ti.

ti.

yoga of the body and breath

yoga of the body and breathNovices are often confused about the coordination of breath and movement in āsana, but with practice, it does not take long to intuit whether a movement should be performed on an inhalation or an exhalation. As we have seen, the basic rule of thumb is that any movement in which the abdomen is compressed (primarily forward bends and twists) should be performed as we exhale, and actions which cause the sternum to lift or the ribcage to expand (primarily backward bends) should be performed as we inhale. As practitioners become increasingly experienced, the breath and body begin to settle into a very comfortable relationship and get to know each other pretty well. There's a feeling that because we are raising the arms, we need to be inhaling; because we are folding forward, we need to exhale. This sort of bodily intuition is necessary and in many ways desirable, but like all relationships, it comes with a potential problem: familiarity allows us to switch off. Sometimes (particularly with experienced practitioners) the body and breath can look like they are working together: both are smooth, even and long, but despite appearances, they are not really in relationship. Instead, both breath and movement have an automatic quality and the relationship has become dull, habitual and unconscious. Neither surprises one another.

The challenge therefore is to keep the relationship fresh and to avoid this “pseudo-relationship” of sa yoga. One way of challenging this is to become very sensitive to the habitual movements of the body as we inhale and as we exhale. Notice the shoulders, the spine, the head and the hands. Do they move with the breath? Does that movement support the breath, or is it simply an unconscious result of the breath? Sometimes it is worth keeping an area fixed and stable despite a habitual tendency, as if the body were saying to the breath: “You do your thing, but I'm going in this direction!” This sort of separation between breath and movement is a form of viveka, and can re-invigorate their relationship with freshness and dynamism.

yoga. One way of challenging this is to become very sensitive to the habitual movements of the body as we inhale and as we exhale. Notice the shoulders, the spine, the head and the hands. Do they move with the breath? Does that movement support the breath, or is it simply an unconscious result of the breath? Sometimes it is worth keeping an area fixed and stable despite a habitual tendency, as if the body were saying to the breath: “You do your thing, but I'm going in this direction!” This sort of separation between breath and movement is a form of viveka, and can re-invigorate their relationship with freshness and dynamism.