Freud said, “I am interested only in the basement of the human being.” Psychosynthesis is interested in the whole building.

—Roberto Assagioli

In 1931, Assagioli published the seminal pamphlet, Psicoanalisi e Psicosintesi (Psychoanalysis and Psychosynthesis), in which he presented the fundamental outline of psychosynthesis theory and practice. So key is this work that it was translated into English and published again in 1934, and it finally was revised to become the lead chapter of his first book, Psychosynthesis (1965a), under the title, “Dynamic Psychology and Psychosynthesis.” This article begins by placing psychosynthesis historically within the development of Western psychology, beginning with Pierre Janet, moving through Freud, Adler, Rank, and Jung, and including Karl Abraham, Sandor Ferenczi, Wilhelm Stekel, Melanie Klein, Karen Horney, Erich Fromm, Ludwig Binswanger, and Viktor Frankl.

After setting this historical context, including some comments about broader cultural movements (e.g., psychosomatic medicine, the psychology of religion, interest in Eastern psychology, etc.), Assagioli presents the vital core of psychosynthesis theory, outlining (1) the basic psychosynthesis model of the person and (2) the stages in the process of psychosynthesis. He thereby presents both the structure or “anatomy” of the person as well as the growth and transformation—the “physiology”—that one encounters over the course of psychosynthesis. This chapter examines the basic psychosynthesis model of the person, and the next chapter presents the stages of psychosynthesis.

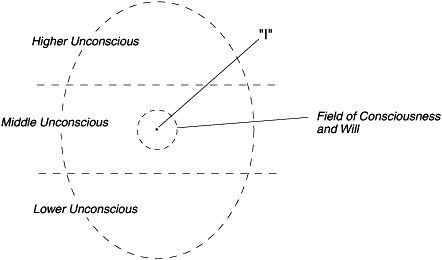

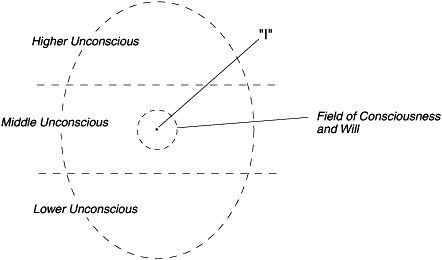

Assagioli’s basic model of the person has remained an integral part of psychosynthesis to the present time. Assagioli (1965a) said that this model was “far from perfect or final” (16), and that it was “of course, a crude and elementary picture that can give only a structural, static, almost ‘anatomical’ representation of our inner constitution” (17). In light of these words, we shall develop here an understanding of this model that brings it more into alignment with current thinking in psychoanalysis, developmental psychology, contemporary psychosynthesis, and the study of psychological disturbances and childhood wounding. A modified version of the original diagram is presented in Figure 2.1.

FIGURE 2.1

The major difference between this diagram and the original is that Self (or Transpersonal Self) is not depicted at the apex of the higher unconscious, half inside and half outside the oval. Instead, Self is not represented at all and should be imagined as pervading all of the areas of the diagram and beyond. The need for this change will be discussed at the end of the chapter.

One general comment about the diagram is that Assagioli understood the oval to be surrounded by what C. G. Jung called the collective unconscious (unlabeled), or “a common psychic substrate of a suprapersonal nature which is present in every one of us” (Jung 1969a, 4). This realm surrounds and underpins the personal unconscious and represents propensities or capacities for particular forms of experience and action common to us all. The collective is the deepest fount of our shared human potential, or as Assagioli wrote, “The collective unconscious is a vast world stretching from the biological to the spiritual level” (1967, 8).1 In the words of Jung,

the [collective] unconscious is not merely conditioned by history, but is the very source of the creative impulse. It is like Nature itself—prodigiously conservative, and yet transcending her own historical conditions in her acts of creation. (Jung 1960, 157)

A last general comment about Assagioli’s diagram is that the different levels of the unconscious constitute a spectrum of potentially conscious experience. That is, these various strata are called “unconscious,” simply because the material contained in them is not within the immediate field of awareness. But the dotted lines shown separating the sectors indicate that contents from these sectors may move through these boundaries—a “psychological osmosis” (Assagioli 1965a, 19, 68)—and thus may enter consciousness under different circumstances. The dotted lines also symbolize the fact that even when unconscious material remains unconscious, it nevertheless causes effects, sometimes powerful effects, in a person’s conscious life (e.g., one may find an unconscious feeling of rage or fear wreaking havoc in interpersonal relationships, or one may be inspired to self-transformation by a pattern in the collective unconscious). Let us now examine this diagram in some detail, knowing that we will further explore most aspects of the diagram in later chapters as well.

Assagioli wrote that the middle unconscious “is formed of psychological elements similar to those of our waking consciousness and easily accessible to it. In this inner region our various experiences are assimilated” (Assagioli 1965a, 17). Thus this is the area in which we integrate the experiences, learnings, gifts, and skills—guided by the patterns from the collective unconscious and in relationship to our particular environment—that form the foundation of our conscious personality. In order to understand the middle unconscious, then, it is necessary to discuss how we form our inherited endowments and life experiences into a coherent, personal expression of ourselves in the world.

There is no hard and fast division between conscious and unconscious.

—Roberto Assagioli

As many researchers have noted (e.g., Bowlby 1969; Piaget 1976; Stern 1985), from the earliest stages of life we form inner patterns that constitute maps or representations of our ongoing experience of self and other. Through these inner patterns—called variously schema (Piaget), internal working models (Bowlby), or representations of interactions that have been generalized (Stern)—we understand ourselves and our world, develop our personalities, and learn to express ourselves.

According to Jean Piaget, this mapping can begin with the most basic reflexes, such as sucking. Here forming a map or pattern (Piaget’s schema) for sucking allows the infant to apprehend the sucking reflex and to incorporate it into a more elaborate pattern of volitional behavior: “After sucking his thumb during fortuitous contact, the baby will be able, first, to hold it between his lips, then to direct it systematically to his mouth for sucking between feeding” (66). So it seems that even our most basic preverbal sensorimotor functions are mapped and then integrated into more elaborate structures of self-expression.2

This developmental achievement is, of course, conditioned by the preexisting pattern within the collective unconscious: “The entire pattern—thumb-to-mouth—is an intrinsically motived, species-specific behavioral pattern” (Stern 1985, 59). This learning also takes place within a facilitating matrix of empathic nurture provided by caregivers; as has been said, archetypal patterns need to be triggered by a facilitating environment (Neumann 1989) or what we will call a unifying center.

This inner structuralization pertains to all dimensions of human experience, including physical, emotional, cognitive, intuitive, imaginal, and transpersonal. It appears that through interacting with the different aspects of our own psyche-soma, and with the environment, we gradually build up structures that synthesize various elements of our experience into meaningful modes of perception and expression.

Whether learning to walk, acquiring language skills, developing roles within family and society, or forming particular philosophical or religious beliefs, we go about this by synthesizing patterns of experience into increasingly complex structures—guided by the innate proclivities from the collective unconscious and our unique social environment. But what does this have to do with the middle unconscious?

THE ROLE OF UNCONSCIOUSNESS

It is important to recognize that while certain patterns are the building blocks for more elaborate structures, the individual building blocks themselves must remain largely unconscious for the structures to operate. The diverse elements that form the more complex expressions cannot remain in consciousness, or we would simply be unable to function beyond the most basic level; our awareness would be so filled with the many individual elements, that a focus on broader, more complex patterns of expression would be impossible.

The following statement by Piaget illustrates the importance of individual elements remaining out of awareness: “Hence we can quickly walk down a flight of steps without representing to ourselves every leg and foot movement; if we do, we run the risk of compromising this successful action” (41). That is, if the many elements of the movement were not somewhat unconscious, our awareness would be filled with them (their “representations”), thereby impairing the larger movement. Assagioli also writes about this natural role of the unconscious:

. . . there occurs a gradual shifting from a conscious focusing of the full attention on the task to an increasing delegation of responsibility to the unconscious, without the direct intervention of the conscious “I.” This process is apparent in the work of acquiring some such technical accomplishment as learning to play a musical instrument. At first, full attention and conscious direction of the execution are demanded. Then, little by little, there comes the formation of what might be called the mechanisms of action, i.e., new neuromuscular patterns. The pianist, for example, now reaches the point at which he no longer needs to pay conscious attention to the mechanics of execution, that is, to directing his fingers to the desired places. He can now give his whole conscious attention to the quality of the execution, to the expression of the emotional and aesthetic content of the music that he is performing. (Assagioli 1973a, 191)

In other words, if we must be aware of the many discrete patterns involved in walking down a stairway, playing the piano, speaking a language, or performing a social role, we will be unable to perform these actions at all. We will instead be overwhelmed by the array of diverse elements making up the action. But by remaining unconscious of these many elements, we can enjoy a smooth, volitional movement. This is a function of the middle unconscious: to store many individual elements outside of awareness so that they may be synthesized into novel, more complex modes of expression. They become what John Bowlby (1980) called automated systems within the personality.

The concept of the middle unconscious thus indicates a sector of a person whose contents, although unconscious, nevertheless remain available to normal conscious expression. The middle unconscious demonstrates the wondrous gift of human unconscious functioning, “that plastic part of our unconscious which lies at our disposal, empowering us with an unlimited capacity to learn and to create” (Assagioli 1965a, 22). This “plastic” or pliable quality describes the capacity to embed patterns of skills, behaviors, feelings, attitudes, and abilities outside of awareness, thereby forming the infrastructure of our conscious lives. This is why the middle unconscious is depicted as immediately surrounding the consciousness and will of “I,” the essence of personal identity.3

SUBPERSONALITIES

Central among the structures of the middle unconscious are what Assagioli (1965a) called subpersonalities. These are semi-independent coherent patterns of experience and behavior that have been developed over time as different expressions of a person.

For example, continuing Assagioli’s example of the man learning to play the piano, we might envision that person, over time, synthesizing many elements—technical skill, natural ability, knowledge of theory, love of music, a joy of performance—into a pianist identity, a pianist subpersonality. This he would have accomplished by drawing on patterns established by past musicians and by being held within a social milieu suitable to nurture this development.

This subpersonality has become a structure within the larger personality by which these learnings and gifts may be expressed. An identity system has been born, a subpersonality, from which the person may experience and act in the world as a pianist. Of course, this will be only one of his subpersonalities, and this subpersonality will have to relate to other subpersonalities that he has developed in expressing other aspects of himself.

While subpersonalities are not limited to the middle unconscious, they often are the most striking psyche-somatic structures to move in and out of awareness on a daily basis. Subpersonalities are common even in psychologically healthy people, and while their conflicts can be the source of pain, they should not be seen as pathological. They are simply discrete patterns of feeling, thought, and behavior that often operate out of awareness—in the middle unconscious—and emerge into awareness when drawn upon by different life situations. Again, their formation has followed the same process that we saw earlier in more basic structuralizations of the personality (e.g., the thumb-to-mouth behavior).

A common way to become aware of subpersonalities is to notice that we seem to become “different people” in different life situations. For example, we may be dynamic and assertive at work but may find ourselves passive and shy in relationships; or we may find our self-confidence suddenly collapsing into anxiety and even panic in the face of an authority figure; or we may surprise others when our easygoing disposition turns to ferocious competitiveness when playing a sport. These are not momentary moods but consistent, abiding patterns—subpersonalities—moving into and out of consciousness from the middle unconscious.

The organization of the subpersonalities is very revealing and sometimes surprising, baffling or even frightening.

—Roberto Assagioli

Subpersonalities can be harmonized into a more coherent expression of the whole person through a variety of different techniques. Such work may or may not involve integrating them into a larger whole, but it will tend toward a situation in which each part can make its unique contribution to the life of the person. Although we devote Chapter 4 to subpersonalities, let us take a brief look at working with a subpersonality.

THE CASE OF LAURA

A woman we shall call Laura4 entered counseling because she found herself acting like a helpless child when relating to her parents and other perceived authority figures. She would become childlike and passive with such people and then finally become angry when she was ignored. This had been causing difficulties in all of her adult relationships, and especially now with her current boyfriend.

Over the course of counseling, Laura realized that this younger part of herself was a subpersonality—she called it “Little One”—with particular feelings of anxiety, shame, and anger. She began relating to this subpersonality instead of attempting to get rid of it, and she became increasingly familiar with how it responded to other people and how it influenced her daily behavior. In listening to the subpersonality, Laura gradually became aware of Little One’s deeper needs for acceptance, affection, and safety, and she began to intentionally make more room in her life for these valid human needs.

This work involved Laura in some brief, lower unconscious exploration as well. She uncovered the childhood roots of her negative feelings and had the painful realization that her parents, although nurturing in many ways, had been emotionally unavailable at a very basic level. She also came to see that her inward rejection of Little One replicated her parents’ rejection of her.

As Laura formed an ongoing, empathic relationship with the subpersonality, there was a marked decrease in the feelings of anxiety, shame, and anger, and she found herself less and less overcome by these problematic feelings in her relationships. Furthermore, the positive qualities of Little One—creativity, playfulness, and spontaneity—became more available to her as well, enriching her relationships as never before.

Laura was involved primarily with the middle unconscious, in that she sought to develop an ongoing, conscious relationship with a subpersonality that moved easily into and out of awareness. Although she also did some lower unconscious investigation (uncovering the childhood conditioning of the subpersonality) and had some contact with the higher unconscious (unlocking the positive potential of the subpersonality), she remained focused upon work with the middle unconscious.

PROFUNDITY, DEPTH, AND CREATIVITY

The function of the middle unconscious can be seen in all spheres of human development, from learning to walk and talk, to acquiring a new language, to mastering a trade or profession, to developing social roles. All such elaborate syntheses of thought, feeling, and behavior are built on the learning and abilities that must eventually operate unconsciously. It is important to remember that the individual elements of these structures are not extinguished but merely operate in the unconscious—thus they often can be made conscious again if need be.

There also is a mysterious profundity of the middle unconscious that can be seen in the creative process. Here we may have been working toward a creative solution to a problem, become frustrated, and finally let go of consciously working on it, only to suddenly have an “Aha!” in which the solution appears to our consciousness fully formed. This type of experience is common in human creativity (see Vargiu 1977), in flashes of intuitive insight, and in the wisdom of nocturnal dreaming. Such experiences make sense in light of the middle unconscious, an active, organizing area operating outside of consciousness that can draw together many disparate elements into new patterns, wholes, or syntheses that can then become available to conscious functioning. As Assagioli wrote, in the middle unconscious “our ordinary mental and imaginative activities are elaborated and developed in a sort of psychological gestation before their birth into the light of consciousness” (Assagioli 1965a, 17).

The depth of the middle unconscious has further been revealed by biofeedback research. Here autonomic processes formerly thought to be beyond voluntary control—such as brain waves, heart rate, and blood pressure—have been brought under the influence of consciousness and will through various feedback devices. Similarly, the study of the mind-body connection in medicine has shown that conscious beliefs, attitudes, and images can influence physical health and disease. All of this research illustrates the interplay between consciousness and the deepest levels of psyche-soma organization in the middle unconscious, that supportive, unconscious substrate of our conscious lives.

Paradoxically, paying conscious attention to, or being emotionally preoccupied with, creative processes disturbs them.

—Roberto Assagioli

Last, the middle unconscious is that area in which we integrate material from the repressed sectors of the unconscious. As we shall discuss shortly, sectors of the personality have been rendered unconscious not in service of self-expression but in order to manage psychological wounding. After discovering and reowning repressed material, whether the heights of transpersonal experience or the depths of childhood wounding, we eventually can integrate these into expressive patterns that support our lives rather than disrupt them.

So the gift of unconsciousness is clear. It is that ability by which aspects of the personality remain outside of consciousness and yet make an active contribution to conscious expression. Here is a potential for developing increasingly creative modes of self-expression, allowing us to bring the widest range of our human potential to our lives. If we had to remain continuously conscious of all of the minute, individual components of our inner and outer expressions, we would function with only a very small percentage of our potential.

As we saw earlier in the case of Laura, it also may be that some of these structures in the middle unconscious are disruptive of our conscious functioning due to early wounding. In these cases, the process of structuralization will involve accessing and healing the wounded pattern, thereby allowing that aspect of ourselves to come into harmony with the personality as a whole. We shall discuss this process more fully in Chapter 4.

Having said all of this about the gift of unconsciousness, we must now say that this gift also is pressed into service of a much more desperate purpose—to survive within a traumatizing environment. Because such an environment is hostile to certain aspects of our experience, these aspects are simply too dangerous and disruptive to be a part of our day-to-day functioning. We therefore seek, in effect, to push these aspects of experience well beyond consciousness, well beyond the middle unconscious, and thereby to form areas of the unconscious that are not simply unconscious but repressed as well—the higher unconscious and lower unconscious. Unlike the middle unconscious, these realms of the unconscious are not in close communion with conscious functioning but are areas that we attempt to insulate completely from consciousness.

Before examining the lower unconscious and higher unconscious, let us first briefly discuss the wounding that we believe creates them, what we have called primal wounding (Firman and Gila 1997).

As Freud (1965) recognized, there is not only an unrepressed unconscious available to conscious functioning but a repressed unconscious, an area of the personality forcefully kept beyond the reach of consciousness and will (Freud’s unconscious). Repression is simply an extreme use of the “plastic” or malleable quality of the unconscious, of our ability to keep areas of our personalities out of awareness. But in repression we do not use unconsciousness to empower consciousness through a supportive, deep structure. We instead attempt to defend consciousness by permanently separating aspects of ourselves from consciousness. From what are we defending ourselves by these extreme measures? We defend against primal wounding.

Primal wounding results from violations of a person’s sense of self, as seen most vividly in physical mistreatment, sexual molestation, and emotional battering. Wounding also may occur from intentional or unintentional neglect by those in the environment, as in physical or emotional abandonment; from an inability of significant others to respond empathically to the person (or to aspects of the person); or from a general unresponsiveness in the surrounding social milieu. Furthermore, wounding is inflicted by “the best of families”—some of what we thought was acceptable and normal in child rearing is now found to be harmful (Miller 1981, 1984a, 1984b).

In sum, it seems that no one among us has escaped some amount of debilitating primal wounding in our lives. All such wounding involves a breaking of the empathic relationships by which we know ourselves as human beings; it creates an experience in which we know ourselves not as intrinsically valuable human persons but instead as nonpersons or objects. In these moments, we feel ourselves to be “It”s rather than “Thou”s, to use Martin Buber’s (1958) terms. Primal wounding thus produces various experiences associated with facing our own potential nonexistence or nonbeing: isolation and abandonment, disintegration and loss of identity, humiliation and low self-worth, toxic shame and guilt, feelings of being overwhelmed and trapped, or anxiety and depression/despair.

When we undergo primal wounding, we repress the experience in an attempt to prevent it from affecting our ongoing functioning. By forcing the wounding from consciousness, we seek to protect ourselves from its impact and create some semblance of safety within the traumatizing environment.

However, we not only repress the pain and trauma but also those valuable aspects of ourselves that were threatened in the wounding. True, we banish the pain so that our consciousness and will are not overwhelmed, and we can continue to function. But we also cleverly seek to protect and preserve the aspects of ourselves vulnerable to wounding by submerging them in the unconscious.

So, for example, if we expressed our creativity as a child, and this was rejected and shamed by others, we would quickly learn that it was dangerous to be creative, and that we must instead learn the rules and abide by them. In order to survive in such an environment, we strive to form ourselves into a more constricted, controlled personality, a mode of being in which creativity is not felt or expressed.

But in order to form such a personality, we have to somehow rid ourselves of creative impulses as well as the painful experiences of shame. We accomplish this by splitting (Fairbairn 1986; Freud 1981; Klein 1975) the shame experience from the experience of creativity within us. In this way we inwardly preserve the creativity safe from the shame. Then we repress both the shame and the creativity so that we can function oblivious of these dangerous experiences. This splitting and repression allow us to survive in an environment in which there is a rejection of our creative potential, because now the environment appears safe—there is now, seemingly, no shaming and no creativity in this world, thus there is no danger. We have survived the wounding.

Staying with the example of the repression of creativity, we can imagine that later in life we find that our days are beginning to seem endless and dreary, that something essential is missing. In exploring the roots of this crisis, we may uncover a powerful need to break the bounds of our rigid life, to be spontaneous, to express creativity. However, simultaneously we may feel extremely anxious, as if our very identity were threatened by this (seemingly) new potential. Phrases such as “You’d better do this perfectly or not at all” or “Watch out or you’ll show how inept and worthless you are” might ring in our minds. These critical and shaming messages are precisely the other side of the creativity-shame split in us that we created long ago in the early nonempathic environment. Now, in reowning the creativity, we need to face the early shame as well. Both sides of the original split may now emerge to be owned, healed, and integrated.

But whatever is repressed returns later, and often in disguise, to claim its due.

—Roberto Assagioli

Over the course of our lives, there have been many wounding events and environments that have necessitated this type of splitting and repression, and all of us function with some amount of this. Thus the repressed area of the unconscious may be quite extensive and can be seen as having two distinct sectors. The sector in which are hidden the rich human potentials threatened by wounding—perhaps our ability to love, create, express joy, commune with nature, or sense a unity with the Divine—is called the higher unconscious. Similarly, the sector that hides the pain of the wounding—whether from covert or overt neglect and abuse—is called the lower unconscious. The lower unconscious and higher unconscious are the other two major levels of the unconscious represented in the oval diagram (Figure 2.1). We now will examine each of these areas in turn.5

The lower unconscious is that realm of ourselves to which we relegate the experience of overwhelming woundings that we have suffered in our lives. Since a repressed unconscious is, by definition, inaccessible to consciousness, its presence must be inferred; this inference is drawn from moments in which highly charged material emerges into consciousness, which in retrospect had been present all along outside of awareness. (We will, for simplicity’s sake, employ usages such as “lower unconscious experience” and “higher unconscious experience” when referring to experiences of material originating in each sector.) The emergence of lower unconscious material can be seen in the words of a man in psychotherapy:

I always thought I’d had a great childhood. My parents seemed like they were always there for me, and all my friends used to say they wished they had my parents instead of theirs. But hitting my 40s, after my divorce, I began to have all this depression, feeling really bad about myself, and feeling abandoned by everyone, even my friends. It was very confusing and scary at first.

But then I began to examine those feelings and see they were coming from a child part of me who had felt totally abandoned by my parents. Looking back, I could see that I had always felt this way at some level. And then I finally began to get that my parents were chronic functional alcoholics. They never missed a day’s work or forgot one of our birthdays, but alcohol was always there acting as a barrier between them and us kids.

If we look back into this man’s life, it is clear that he functioned up until his forties with no awareness of this experience of abandonment by his parents. He had become a successful, skilled professional, learning to express himself in productive ways that made full use of his middle unconscious. Yet a fundamental aspect of his life experience—his abandonment, depression, and low self-esteem—was never allowed into consciousness. Triggered by the divorce, this abandonment depression emerged from the lower unconscious into the middle unconscious and began to enter into his awareness until he was impelled to address this in therapy.

As this level of himself began to become conscious, it was at first “very confusing and scary.” Why? Because the existence of such feelings went counter to the identity by which he had survived, that identity which was based upon the affirmation, “My parents were great.” But this smoothly functioning and successful identity, under the stress of his divorce, began to be disrupted, and this deeper layer of his unconscious began to reveal itself. Here was a stunning challenge to the view he had of himself and others throughout his whole life.

Obviously, then, the lower unconscious exists in the present and affects our daily lives. In fact, this splitting of our experience also makes us blind to the current violation and neglect of ourselves by other people and by society in general. We may be relatively unaware of how we are personally affected by the tremendous level of violence pervading modern life, and indeed, we may be unaware of this even when we are the direct victims or perpetrators of this violence. This repression of the traumatic thus can support a variety of dramatic departures from authentic being and our sense of self, including naive optimism, otherworldly spirituality, and chronic patterns of abuse.

The lower unconscious contains . . . many complexes, charged with intense emotion.

—Roberto Assagioli

So note well: The lower unconscious does not simply comprise experiences we have had in the past and then repressed; it is our lost ability to experience the tragic dimension of existence.

SURPRISED BY PAIN

When material from the lower unconscious suddenly breaks through to consciousness, we may be “surprised by pain,” as were Robert and Rachel. Robert entered therapy because his wife Rachel was complaining of his chronic demeaning attitude toward her, and she had threatened divorce if he did not correct this. Initially, Robert simply saw his behavior as “just joking around” and Rachel as being “too sensitive.” But gradually he became aware of his rage underlying his behavior, and beneath that rage, the feelings of shame and worthlessness from childhood. As he got in touch with this childhood wounding, he recognized the abuse entrenched in his family of origin and so became sensitive to the hidden abuse in his own behavior.

As Robert began to change his demeaning attitude, Rachel found it necessary to work on her own attitude of contempt and on her need to control, which often triggered Robert’s worthlessness and rage. Rachel also found herself exploring her own early wounding as she struggled to change. As they worked through their wounding and the reactions to this, Robert and Rachel gradually were able to create a safe, healing environment that could support their own growth and that of their children.

Robert and Rachel were “surprised by pain”—they experienced a disrupting emergence of lower unconscious material into their marriage. These feelings and attitudes had always been present, though operating outside of their awareness, and healing here led to a more trusting, intimate relationship.

Thus healing in the lower unconscious is not simply a healing of the past but a healing of the present. In such personal transformation, our here-and-now perception of self and world becomes increasingly clear and accurate; there is a developing freedom from compulsivity and rigidity; and we begin to find a sense of authentic personal identity and power from which to embrace life.

But the lower unconscious is not the only realm of human experience lost to normal, everyday awareness; we may split off not only the dimension of traumatic wounding but the positive dimensions of life as well. This splitting is a way we seek to protect our capacities for wonder, joy, creativity, and spiritual experience from an unreceptive, invalidating environment. This repression of our higher human potential has been discussed as the repression of the sublime (Desoille) by psychosynthesis psychotherapist Frank Haronian (1974), and it forms what is called the higher unconscious—a realm of ourselves that, like the lower unconscious, exists now, affects us in the present, and is cut off from normal, everyday awareness.

Recall the case of the man above who in his forties became aware of his abandonment depression and began psychotherapy. As he worked with his depression, he began having an inflow of a new kind of positive energy as well. He had a number of experiences in which, at the depths of the pain of his wounding, he felt a new appreciation for himself, his parents, and the world. At one point he had an important peak experience in which he felt connected to all of humanity and to a sense that all things were held by an even deeper presence that he could only call God. Here was a healing of the split from his early years, a reowning of a repressed “lens” through which he could appreciate the mystery and depth of life—an inflow from the higher unconscious.

The higher unconscious (or superconscious) denotes “our higher potentialities which seek to express themselves, but which we often repel and repress” (Assagioli 1965a, 22). As with the lower unconscious, this area is, by definition, not available to consciousness, so its existence is inferred from moments in which contents from that level affect consciousness.

Higher unconscious experiences are those moments—often difficult to put into words—in which we sense deeper meaning in life, a profound serenity and peace, a universality within the particulars of existence, or perhaps a unity between ourselves and the cosmos. This level of the unconscious represents an area of the personality that contains the “heights” overarching the “depths” of the lower unconscious. Assagioli says of the higher unconscious:

From this region we receive our higher intuitions and inspirations—artistic, philosophical or scientific, ethic “imperatives” and urges to humanitarian and heroic action. It is the source of the higher feelings, such as altruistic love; of genius and of the states of contemplation, illumination, and ecstasy. In this realm are latent the higher psychic functions and spiritual energies. (Assagioli 1965a, 17–18)

Note, however, that the higher unconscious does not indicate some realm of pure qualities or essences separated from the world. The characteristics of love, joy, unity, or beauty found in higher unconscious experiences are not independent higher qualities drifting down to the world from some heavenly realm; they describe empirical modes of sensation, feeling, and cognition in which we experience certain aspects of this world in particular ways. Higher unconscious experience is not so much an encounter with another higher world as it is a deeper, an expanded, or a more unitive view of this world.

Just as the lower unconscious prevents us from perceiving our own pain and the pain of others, so the higher unconscious is our lost ability to perceive the more sublime or spiritual aspects of the world. Splitting and repression have caused us to become blind to the profound mystery of the world, our unique place within it, and our fundamental relationship to it, to other people, and to the Divine.

Higher unconscious experience has long been studied by Western psychology, and here we will mention some of the thinkers that Assagioli himself regarded as addressing this area. As early as 1901, Canadian psychiatrist Richard Bucke (1967) published his study of higher unconscious experiences in his book, Cosmic Consciousness, making him one of the first transpersonal psychiatrists. Around the same time as Bucke’s work, psychologist William James (1961) published his classic work on spiritual experience, The Varieties of Religious Experience. And adopting a term used by Rudolf Otto, C. G. Jung (1969b) affirmed higher unconscious contents as numinosum, which he said could cause an “alteration of consciousness” and pointed to the universality of such experiences.

The superconscious is only a section of the general unconscious, but which has some added qualities that are specific.

—Roberto Assagioli

Assagioli also believed that Viktor Frankl, in his system of logotherapy, referred to the higher unconscious in speaking of the noetic or noological dimension and of height psychology (Assagioli 1965a, 195, 197). Lastly, Abraham Maslow’s study of peak experiences was, in Assagioli’s view, dealing directly with the higher unconscious. In Maslow’s words:

The term peak experiences is a generalization for the best moments of the human being, for the happiest moments of life, for experiences of ecstasy, rapture, bliss, and the greatest joy. (Maslow 1971, 105)

This quotation is a clear description of higher unconscious experience. As mentioned earlier, Maslow’s groundbreaking work was instrumental in the birth of the fields of humanistic and transpersonal psychology. Many others, too numerous to name, have made higher unconscious experience the subject of serious psychological study.

SURPRISED BY JOY

As with the lower unconscious, splitting and repression keep the higher unconscious aspects largely out of awareness—the repression of the sublime. A strong repression of this spectrum of human experience eventually leads toward an uninspired life, a life from which all deeper love, wonder, and greater meaning have been excluded. Here we inhabit only one small dimension of the rich, multidimensional cosmos, adopting an attitude that is matter-of-fact, materialistic, and perhaps jaded or cynical. Unaware, we are cut off from the compassionate touch of the infinite and the eternal, and we come to assume that the deadness of our lives is a deadness of life itself. Again, the split in ourselves is not simply a split in the past but a split in the present; it affects how we experience ourselves and the world on a day-to-day basis.

However, as is the case with the lower unconscious, we can be surprised by the higher unconscious breaking into awareness—this is often what a peak experience is. Here C. S. Lewis’ (1955) phrase, “surprised by joy,” is very apt, as a seemingly new realm of human experience is revealed before our disbelieving eyes. A vast array of people from many different traditions and cultures throughout history have reported such experiences and have witnessed the power of these moments to transform human life.

But as Assagioli (1965a) pointed out, these higher experiences may surface lower unconscious material as well; we may feel our wounding, our fear, anger, and depression, in the face of this sublime aspect of reality. As the repression barrier is breached, the original reason for the repression—the earlier wounding—also may be brought to light. It is as if our organismic striving for wholeness attempts to bridge this original split between higher and lower, so that an emergence of either sector quite often entails the emergence of the other.6

MIDDLE UNCONSCIOUS EXPANSION

The higher unconscious and the lower unconscious become of practical importance, and perhaps a matter for psychosynthesis therapy, as we encounter these areas of potential experience and seek to include them in our lives. As we shall see, the integration of both the higher and lower unconscious is tantamount to an expansion of the middle unconscious; that is, our daily experiential range—the spectrum of reality that we potentially may be aware of and respond to—expands to include more of the heights and depths of human existence.

We shall discuss this type of work more fully later, but let us say here that this integrative expansion of our experiential range allows us to engage the world in a more whole way. The heights and depths of existence are not so much “surprises” but become more a part of our ongoing daily living: we can feel the joy of a sunset and then be touched by a sadness at the transience of life; we can feel the grief of childhood losses and then feel gratitude for the gifts that we have gained; we can fall in love and then be touched by the struggles of our beloved; or we can enjoy the richness and beauty of a forest and then become suddenly pained by humankind’s abuse of nature. This wide dynamic range of experience, often repressed and unconscious, becomes more available to us on a daily basis as we integrate the higher and lower unconscious.

Note again that the higher unconscious and the lower unconscious do not simply comprise experiences that we have had and that are now repressed. Rather, they represent a splitting of our experiential range in the moment, and as such, they affect any new experiences that we have. They are not simply areas in which we store past experiences but are broken and missing “lenses” whose loss renders us blind to the heights and depths of existence. Following Bowlby (1980), we can say that “defensive exclusion” cannot only exclude from consciousness information already stored in long-term memory but also information arriving through sensory input in the present moment (i.e., “perceptual blocking”).

Having discussed these three levels of the unconscious, we now can turn our attention to the last element of the oval diagram: the “who” who lives and moves among these levels—the human spirit or “I” who possesses the functions of awareness and will. “I” is represented by the point at the center of the oval diagram (Figure 2.1) and also is called personal self (written with a lower-case “s” to distinguish personal self from Self, written with an uppercase “S”).

Recall the case of Laura, described in the earlier section on the middle unconscious. Laura recognized a child subpersonality whose behavior was disrupting her adult relationships, and she was able to facilitate its harmonious inclusion in her life.

Implicit in Laura’s transformation was her realization that she was not simply a childish person but that she had a child part of herself. This realization gave her the freedom to come into a relationship with this child subpersonality, to take responsibility for working with her, and to learn to nurture her as her parents had been unable to do. In other words, she discovered that her deeper identity was distinct—though not completely separate—from this subpersonality. Here is a movement from the stance “I am a child” to “I have a child.” This ability to identify with, or disidentify from, different aspects of the personality reveals the profound nature of “I.”

“I” is the essential being of the person, distinct but not separate from all contents of experience, a characteristic that we call transcendence-immanence (Firman 1991; Firman and Gila 1997). That is, Laura realized that she was distinct from—transcendent of—her child subpersonality, and from this disidentification, she found that she could be present to the child and include her—that is, she could be immanent, engaged, with the child. “I” is transcendent, in that “I” cannot be equated to any content, yet “I” is immanent, meaning “I” can be with, embrace, and experience all content. This profound transcendence-immanence is why “I” can be thought of as human spirit and not as a structure, a complex, or an organization of content.

“I” further possesses the two functions of consciousness (or awareness) and will (or personal will) whose field of operation is represented by the concentric circle around “I” in the oval diagram. “I” is placed at the center of the field of awareness and will to indicate that “I” is the one with consciousness and will. “I” is aware of the psyche-soma contents as they pass in and out of awareness; the contents come and go, while “I” may remain present to each experience as it arises. But “I” is dynamic as well as receptive: “I” has the ability to affect the contents of awareness, and can even affect awareness itself, by choosing to focus awareness, expand it, or contract it. Let us first briefly examine consciousness and then will, using Laura’s work as an example.

CONSCIOUSNESS

As “I” disidentified from the child subpersonality, Laura’s consciousness or awareness was no longer simply that of a child who was feeling completely overwhelmed by anxiety, shame, and anger. Instead, her awareness became open to more adult aspects of her personality from which she could then act in relationship to both the subpersonality and the outer environment. Note that in disidentification, her consciousness did not become dissociated from the feelings of the child, but rather her consciousness expanded to include the adult perspective as well as the feelings of the child. This clarification or expansion of awareness takes place as “I” disidentifies from a particular limited identification, and “I” is thereby able to include other perspectives as well—again, the principle of transcendence-immanence.

WILL

This ability to disidentify and become aware of different perspectives demonstrates not only the nature of consciousness but the nature of personal will. As Laura shifted her identification from “I am a child” to “I have a child part of me,” she experienced the freedom to make choices that were not totally controlled by the child. She could choose, for example, to relate to the child, to explore her feelings and, finally, to make decisions in her life that were not limited to the perspective of this single part of herself. Laura’s freedom clearly illustrates what Assagioli means by the term will.

Note that the will of “I” is not, then, the repressive force commonly referred to as “willpower.” Willpower usually denotes the domination of one part of the personality by another, as Laura might have done had she attempted to push the child out of her life completely. Quite the contrary, will is that gentle inner freedom to act from a place that is not completely conditioned by any single part of ourselves. Will allows “I” to disidentify from any single perspective, and thereby to be open to all of the varied aspects of the personality.

. . . the central place given in psychosynthesis to the will as an essential function of the self . . .

—Roberto Assagioli

Through these functions of consciousness and will, transcendent-immanent “I” is the focus for engaging all the rich multiplicity of our personalities. Since “I” is that “who” who is able to identify with, and disidentify from, all of the many changing parts of the personality, “I” has the potential of being in communion with all of the parts, of knowing and acting from our wholeness.

THE RELATIONSHIP OF CONSCIOUSNESS AND WILL

The field of consciousness and will is illustrated as a single circle in the oval diagram (Figure 2.1). However, we may think of that circle as representing, in fact, two interpenetrating fields, one of will and one of consciousness. The field of consciousness and the field of will are in constant flux, with one or the other becoming larger and more operational often from one moment to the next.

For example, consciousness may overshadow will: imagine that you are relaxed and enjoying a sunset or a piece of music, allowing your mind to drift. You are not choosing to focus on anything in particular, not limiting your awareness in any way, but instead you are receptive to all of the myriad feelings, thoughts, and images that might arise. In this case, your consciousness is in the foreground, while your will remains in the background. You might even find it difficult to make a decision in this state, being aware of so many possibilities that you are hard put to choose anything at all. You might even know people who tend to be habitually imbalanced toward the awareness pole, who seem to have a broad consciousness but a limited ability to choose, to act.

On the other hand, will may overshadow consciousness: imagine that you are highly focused on riding a bicycle through heavy city traffic. In this experience, you will keep your awareness focused on the traffic, the road conditions, and the position of your bicycle. Instead of allowing yourself to be receptive to any and all content, you choose here to limit your awareness to task-related content only. In this way, your awareness strictly serves the many continual choices needed to ride safely through the traffic. Your will is in the foreground in this situation, with consciousness playing a more secondary or supportive role. There also are people whose will function habitually outbalances their consciousness function—they can be highly effective, making quick choices with ease and competence, but they may, perhaps, have little awareness of how their behavior affects themselves or others.

THE NATURE OF “I”

The nature of “I” is explored in psychotherapy when there is a focus on facilitating (1) the ability to become aware (consciousness) of various aspects of the personality or behavior, and (2) the ability to make choices (will) in relationship to these. This focus is in fact quite common among otherwise very dissimilar psychotherapies. For example, psychoanalysis encourages free association, a choice to focus upon the flow of thoughts, feelings, and images within us; humanistic/existential psychology encourages us to explore the reality of our direct experience and to take responsibility for this experience; cognitive-behavioral psychology directs our attention to the thought processes underlying particular moods and allows us to intervene in these; and transpersonal psychology might facilitate an awareness of higher states of consciousness and assist us in expressing these insights in our lives.

The nature of “I” also is revealed in spiritual practices such as vipassana and Zen meditation in the East and contemplative and centering prayer in the West. An aspect of these types of practice is to allow psyche-soma contents to come and go in awareness without becoming caught up in them. The principle is that we can learn to simply sit in silence, being present and mindful to the moment, while allowing sensations and feelings and thoughts and images to pass unhindered through awareness. What is sometimes overlooked is that this is not simply a state of “pure consciousness” but is actually a very intentional state—we choose or will to remain in this receptive state. In fact, we may frequently need to choose to bring back consciousness when it is caught up in distracting sensations, thoughts, and feelings.7

All such practices, whether psychotherapeutic or meditative, demonstrate that “I” is distinct, though not separate, from all of these contents of experience, in other words, “I” is transcendent-immanent within contents of experience, otherwise it would be impossible to observe such contents continuously coming and going, with our point of view remaining ever-present to each succeeding content. There must be someone who is distinct but not separate from the contents, remaining an observer/experiencer of the contents, and who can choose to affect them. “I” is this transcendent-immanent “who” who is in, but not of, the changing flow of experience and therefore can be present to any and all contents of experience.

. . . the direct experience of the self, of pure self-awareness—independent of any “content” of the field of consciousness.

—Roberto Assagioli

This distinction between “I” and the content of experience is implicit in these spiritual practices, but it also is characteristic of any disidentification experience. For example, this distinction is central to Laura’s realization that she was not the child subpersonality, that she need not be dominated by it, and that she could learn to care for this younger part of herself. Whereas a person in meditation might observe contents of experience passing into and out of awareness, Laura could observe her child subpersonality coming and going in her awareness. Here she was not only noticing her sensations, feelings, and thoughts but was conscious of the deeper structure that organized her sensations, feelings, and thoughts. She thus could realize that she was distinct from (transcendent of) this larger pattern and begin to work with it and include it (become immanent, engaged with the pattern).

Experiences such as these indicate that “I” is not a content or an object of experience but the subject of experience. Although “I” may indeed be caught up in strong feelings, obsessive thoughts, or habitual patterns of behavior, “I” is ever the experiencer, distinct but not separate from any of these. As we shall explore later, “I” also can be referred to as no-self or no-thing, because “I” is beyond anything that we can grasp and hold, beyond any content, process, or structure by which we might define ourselves. We shall take up the nature of “I” at length in Chapter 5.

Pervading all of the areas mapped by the oval-shaped diagram, distinct but not separate from all of them, is Self, which also has been called Higher Self or Transpersonal Self. The concept of Self points toward a deeper source of wisdom and guidance, a source that operates beyond the control of the conscious personality.8

Both Assagioli and Jung called this source Self and believed that this manifested as a deeper direction in an individual’s life. One might experience Self as a movement toward increasing psychological wholeness, toward a growing “fidelity to the law of one’s own being” (Jung 1954, 173), or perhaps toward a sense of purpose and meaning in life. Both thinkers also believed that many psychological disturbances were a result of finding oneself out of harmony with the deeper direction indicated by Self.

Jung deemed the experience of this direction of Self vocation, an invitation from the “voice of the inner man [or woman]” to undertake the way of individuation. Assagioli spoke of this deeper direction as the will of Self, or transpersonal will, and he saw the potential for a meaningful interaction between transpersonal will and personal will, or the will of “I.” What follows is one example that Assagioli uses to illustrate this relationship of personal will and transpersonal will, the relationship of “I” and Self:

Accounts of religious experiences often speak of a “call” from God, or a “pull” from some Higher Power; this sometimes starts a “dialogue” between the man [or woman] and this “higher Source.” (Assagioli 1973a, 114)

Of course, neither Jung nor Assagioli limited the I-Self relationship to those dramatic experiences of call seen in the lives of great women and men throughout history. Rather, the deeper invitations of Self are potential to every person at all times. As will be discussed later, this deeper direction may be assumed to be present implicitly in every moment of every day, and in every phase of life, even when we do not recognize this. Whether within our private inner life of feelings and thoughts or within our relationships with other people and the wider world, the call of Self may be discerned and answered.

“I” AS AN IMAGE OF SELF

Among all of the elements depicted in the oval diagram, “I” has the most direct and profound relationship with Self. In earlier versions of the diagram, this relationship was illustrated well by a straight dotted line connecting “I” and Self (although the latter was placed at the apex of the higher unconscious). Assagioli spoke of the I-Self connection in the following way:

. . . the personal conscious self or “I,” which should be considered merely as the reflection of the spiritual Self, its projection, in the field of the personality. (Assagioli 1965a, 37)

That is, “I” is not a differentiation of Self, not one aspect of Self, not an emanation of some supposed “substance” of Self, but a direct reflection or image of Self. The metaphor here is perhaps a candle flame whose image is reflected in a mirror, or the sun’s image reflected on the surface of water. “I,” essential human identity, is not an independent, self-sustaining entity but is directly and immediately held in existence by deeper Self.

To approach the metaphor from another angle, we might say that “I” is as indissolubly united to Self as a mirror image is indissolubly united to that which it reflects. Of this profound level of union, Assagioli says, “There are not really two selves, two independent and separate entities. The Self is one” (Assagioli 1965a, 20). There are, indeed, many experiences, known within both religious and nonreligious contexts, which seem to indicate this fundamental human dependency on, and hence unity with, a deeper source of being.

While Assagioli affirms this essential unity of “I” and Self, he also is extremely careful to emphasize the importance of maintaining the distinction between them. As profound as the I-Self unity is, this unity does not imply that “I” is an illusion. To apply the mirror metaphor: the mirror image has a relative or contingent existence, because it is dependent on the source, but this does not mean that its existence is unreal.

Not maintaining this distinction between “I” and Self can lead to serious difficulties in a person’s life. Assagioli, along with many others, consistently warns about the dangers of confusing the reflected image with the reflecting source, “I” with Self:

In cases where awareness of the difference between the spiritual Self and the personal “I” is lacking, the latter may attribute to itself the qualities and power of the former, with megalomania as the possible end product. (Assagioli 1976, 10; see also 1965a, 44–45; 1973a, 128)

Thus the notion of “I” as a reflected image of Self can be helpful in understanding the paradoxical unity of “I” and Self. The two selves are one, fundamentally united by Self’s act of creation, yet they are two, the image ever remaining an image and not the source.

THE NATURE OF SELF

Assagioli’s idea that “I” is a reflection of Self also suggests a way of understanding the nature of Self by analogy to “I.” By such an analogy, the nature of “I,” which is implicit in personal experience, can be extrapolated to Self, a deeper center not nearly so available to personal experience. Assagioli (1973a, 124–25) himself states that analogy is a method by which to approach an understanding of Self.

The first thing that becomes apparent by this analogy is that Self is living, conscious, willing, Being. That is, if individual I-amness is a reflection of Self, then Self must be deeper I-amness. Self is, therefore, not to be viewed as a blind, undifferentiated unity; nor as an energy field, however subtle and rarefied; nor as an organismic totality; nor as a collective pattern or image of some sort; nor as a higher level of organization; nor as some impersonal or inanimate energy source; rather, it is to be viewed as deeper Being with consciousness and will.

In other words, Self is not something, not an “it” but someone. Self is a “Thou” to whom we may meaningfully relate. It is true that a sense of this “Thou-ness” may be submerged in a powerful moment of experienced union with Self, when “I” and Self are known as one. But quite practically, the ongoing, intimate, empathic relationship of “I” and Self is an “I-Thou”—not an “I-It”—relationship. This view of Self can be seen in Assagioli’s words, quoted earlier, in which he affirms the possibility of meaningful “dialogue” with the “higher Source”—an activity that would be nonsensical if dealing with some sort of blind, impersonal cosmic force or universal energy. Such dialoguing is applied in many effective and practical psychosynthesis techniques designed to support a conscious relationship with Self (e.g., see Assagioli 1965a 204–7; Miller 1975), and it also is found in the field of transpersonal psychology (see Vaughan 1985).

. . . his spiritual Self who already knows his problem, his crisis, his perplexity.

—Roberto Assagioli

Pursuing this analogy of “I” to Self, we come to a second important insight into the nature of Self. If, as stated above, “I” is distinct but not separate from contents of awareness—transcendent-immanent—then Self also may be understood as distinct but not separate from such contents—transcendent-immanent. We might speculate that since “I” is “in but not of” all of the passing sensations, feelings, and thoughts of daily experience, Self is “in but not of” all of the content of all of the levels represented in the oval diagram (and perhaps beyond, as we shall discuss in Chapter 8).

SELF AND THE OVAL DIAGRAM

This transcendent-immanent omnipresence of Self implies that Self may be met at any level of the oval-shaped diagram, but that Self should not be confused with any particular level. Whether encountering the bliss of peak experiences, the more mundane events of daily life, or the depths of early childhood trauma, we can assume that Self is present, active, and available to relationship.

As mentioned earlier, the original oval diagram portrayed Self at the apex of the higher unconscious (on the boundary with the collective), but such a representation tends to obscure just this profound omnipresence and immediacy of Self at all levels of experience. That earlier placement of Self can give the impression that Self is approachable through the higher unconscious only, a view that Assagioli himself appeared to support at times: “The superconscious [higher unconscious] precedes consciousness of the Self” (Assagioli 1965a, 198, emphasis added). In effect, the earlier diagram seemed to represent Self-realization as leading, at least initially, upward into higher states of consciousness.

But this belies the fact that our life journey—the following of our path of Self-realization—can lead us to engage any level of experience at any point on the path. What follows is just one of countless examples:

This morning I sit in prayer, discouraged, angry, and confused. I do my usual intentional connecting with Self, nature, etc. I speak out my anger and hopelessness directly to Self. My situation has not changed. Nothing is happening in my life, no movement is occurring, no changes are imminent. My heart is closed. The events that seemed to portend an opening and a new beginning for me a few days ago are gone. Nothing positive seems to have come from them. It is clarifying for me to speak this way. I feel present and deeply connected to my pain and confusion. The awareness that comes up for me is that I feel very available to myself right now.

As I sit more with this, I can also feel held and supported in my pain and despair—no movement, no inrush of happy feelings—just held. It strikes me that this is Self, the Empathic Therapist at work, engaging me as I attempt to build a bridge with my anger and frustration. I’m more congruent with my feelings now.

I am reminded of how often I attempt to provide a validating, empathic atmosphere for clients as they wrestle with their own difficult feelings and experiences. Often we end a session and they are still with their pain. Their struggle is not resolved but they seem more able to cope and they often tell me so. Right now I feel this way. More able to cope, not especially liking the experience, but definitely more present to a difficult cycle I am going through. (Meriam 1996, 21–22)

This experience of communion with Self involved little higher unconscious experience but rather a call to engage current feelings of pain and despair, an invitation to “be here now.” If we are direct “reflections” of Self, we are held in being throughout the entire range of our experience, and we may be called to engage any point on this range, from the heights to the depths. Remaining faithful to our deepest sense of truth, following our callings or vocations in life, can take us most anywhere and draw upon many different aspects of ourselves. To alter Assagioli’s phrase just quoted, it may be anything at all that precedes contact with Self.

Given this observed omnipresence of Self, we and some others in the field (see Brown 1993; Meriam 1996) choose not to represent Self at the apex of the higher unconscious, rendering no image of Self at all, while making it clear that Self is to be understood as active and present throughout all of the levels of the person. We feel that representing Self in the direction of the higher unconscious can give the impression that Self-realization necessarily involves an ascent into the higher unconscious.9 Others in the field elect to preserve the earlier rendering of Self, although they too agree that the omnipresence of Self throughout all levels must nevertheless be made quite clear (Djukic 1997; Marabini and Marabini 1996).

Man’s [and woman’s] spiritual development is a long and arduous journey, an adventure through strange lands full of surprises, difficulties and even dangers.

—Roberto Assagioli

In understanding Self as pervading all levels of the person, we must avoid the mistake of then equating Self to the wholeness of the person—Self is not simply the entire oval. Self is not the “totality” of the person, as Jung stated at times (Jung 1969a, 304; 1969b, 502). Self would be distinct but not separate from such a totality, always transcendent of the totality, yet immanent within the totality. In much the same way that “I” can be simultaneously aware of several different feelings and thoughts at one time, so Self might be simultaneously aware of all of the processes of the entire organism (and beyond) at the same time.

In sum, it seems clear that approaching the nature of Self through an analogy to “I” leads to various useful insights, and to the same single conclusion: Whether envisaging a deeper I-amness as the abiding ground of individual I-amness, or envisaging a deeper transcendence-immanence as the source of individual transcendence-immanence, it seems clear that the I-Self relationship can exist throughout all life experiences, in all spheres of life, and in every stage of life. This profoundly intimate relationship is the fundamental axis of the journey called Self-realization, discussed in more specific terms later.

Thus we have explored Assagioli’s “anatomical” and “static” model of the human person, but what about the psychological “physiology” of the person, the dynamic changes of healing and growth? Keeping the oval diagram in mind, we now turn to the other major framework of psychosynthesis thought and practice outlined by Assagioli: the stages of psychosynthesis.