Have you ever noticed that you behave differently in your office, at home, in social interplay, in solitude, at church, or as a member of a political party?

—Roberto Assagioli

Part of me wants to be with him, but another part of me says, “No way.” It’s very confusing.

I’m always beating myself up. If I make one little mistake, I can hear the critic inside me yelling at me for being stupid—just like my father used to.

One minute I can be sailing along happy and carefree, and then suddenly, for no reason at all, I feel sad and scared. My girlfriend says I’m too moody.

I couldn’t go to sleep because the committee was having a meeting in my head. All these arguments. It made me so upset I finally got out of bed.

As we begin to explore our ongoing inner experience in the first stages of psychosynthesis, it becomes obvious that there are many different parts operating within us. These different parts will be noticed emerging in response to the different life situations that we face daily. At work, we may recognize that we are intellectual and task oriented; with a lover, warm and intimate; with authority figures, anxiously passive or angrily rebellious; and when playing a favorite sport, perhaps ferociously competitive.

We may even refer to these aspects of ourselves in ordinary conversation: “That was my heart talking, not my head,” or “My feelings got hurt,” or “My artistic side needs to express itself.” Other people also may notice our shifting parts: “This is a whole side of you I’ve never seen before,” or “You don’t seem yourself today,” or “I like it when you let your playfulness out.”

Each of these different parts of us is composed of various personality elements—particular skills, gifts, values, attitudes, worldviews—which are formed into an operating whole or synthesis through which we function in different environments. As mentioned in Chapter 2, these semi-autonomous subsystems within the personality are what Assagioli (1965a) called subpersonalities.

Before examining subpersonalities more closely, let us emphasize that multiplicity within the human personality is quite normal. Subpersonalities are an aspect of the gift of the middle unconscious (Chapter 2), an example of the structuralization process that begins with some of our most basic inborn reflexes. It is simply that in subpersonality formation this structuralization has proceeded to such an extent that an entire identity system has been created. From a range of different inborn abilities and learned skills, through interaction with the environment, a sophisticated expression of self has been formed. Further, as the various subpersonalities begin to relate in cooperative and synergistic ways, the same structuralization process may create even more sophisticated expressive patterns from the relationships among subpersonalities (discussed later).

It is quite true, of course, that there is a less common personality organization commonly known as multiple personality disorder, lately renamed dissociative identity disorder, or DID (First 1994). In personality structure, the subpersonalities or alters are so dramatically dissociated that there is little continuity of consciousness among them. For example, among other things, people with DID may have the experience of “losing time,” in which they do not remember what occurred when another subpersonality was in charge. This personality organization can be seen as existing further along on a continuum of dissociation that we all share.

The difficulties that any of us experience with our multiplicity—inner conflict, ambivalence, anxiety, depression, and so on—are not a problem of multiplicity per se but of a lack of cooperation among the parts of the personality. The “cure” for our maladies here is not a matter of eliminating the multiplicity but of seeking better relationships among the multiple parts. Just as the United States is not a melting pot in which various ethnic and cultural groups are to be dissolved into one undifferentiated homogeneous mass, so the human personality is not a melting pot in which subpersonalities are to be fused into a seamless whole. The challenge—for both inner and outer societies—is to seek right relationships among diversities.

The normality of multiplicity within the personality has been recognized by many different psychological systems and cultural traditions, both past and present. The West historically has understood this diversity as the multiple abilities, faculties, and habits operating for good or ill within the human soul. In the East, there are vasanas and samskaras, terms that refer to tendencies, desires, and habits that may be in harmony or conflict within the person. And in a traditional African worldview, the normal human personality is “seen as a community in and of itself, including a plurality of selves” (Ogbonnaya 1994, 75).

In Western psychology, inner diversity has not only been widely recognized but has become the foundation for entire approaches to psychotherapy: from Freud’s ego, superego, and id, Jung’s complexes, William James’ various types of selves, Melanie Klein’s internal objects, Paul Federn’s ego states, Fritz Perls’ top dog and underdog, Virginia Satir’s parts of the person, Erv Polster’s population of selves, and Assagioli’s subpersonalities, to the systems of transactional analysis (Berne 1961), gestalt therapy (Perls 1969; Polster 1995), ego therapy (Shapiro 1976), voice dialogue (Stone and Winkelman 1985), internal family systems therapy (Schwartz 1995), and ego state therapy (Watkins and Watkins 1997).

It also is safe to say that subpersonality theory is perhaps the most common topic of psychosynthesis literature (e.g., Brown 1983; Brown 1993; Carter-Haar 1975; Ferrucci 1982; Firman and Gila 1997; Firman and Russell 1993; Hardy 1987; Kramer 1995; Meriam 1994; Rueffler 1995a; Sliker 1992; Vargiu 1974b; Whitmore 1991). For an overview of a variety of approaches to subpersonalities, see John Rowan’s Subpersonalities (1990).

Suffice it to say that numerous observers, both past and present, from diverse cultures and disparate disciplines have looked at the human being and seen the multiplicity of which we are made. Again, and perhaps more to the point, this is easily demonstrated by anyone who is willing to undertake a careful examination of his or her lived experience over time.

. . . the psychological multiplicity that exists in each of us.

—Roberto Assagioli

Before moving into a discussion of subpersonality formation and harmonization, it should be noted that Assagioli himself wrote little about subpersonalities beyond affirming their existence and locating them within then-current psychological research (see Assagioli 1965a, 74–77). Like much of psychosynthesis thought and practice, it has been up to subsequent thinkers in the field to elaborate and extend Assagioli’s initial concepts. What follows below is our own understanding of the genesis of subpersonalities, followed by a stage or phase theory modified from the work of Steven Kull, Betsie Carter-Haar, and James Vargiu (Vargiu 1974b) at the Palo Alto Psychosynthesis Institute, a theory that did have its origin in direct conversations with Assagioli.1

George was generally satisfied with his career as a technical writer but was looking for something more in his life. One weekend he happened to attend a motorcycle rally with a friend and was intrigued by what he saw. He was attracted—one might even say “called”—by the beauty of the shiny motorcycles, the camaraderie among the riders, and the general atmosphere of freedom and adventure at the rally.

Note that the general culture of the motorcycle rally presented George with a unifying center, a center of meaning that began to evoke a deep response in him. His relationship to this unifying center offered him qualities such as beauty, camaraderie, freedom, and adventure (as we shall see, these qualities are called transpersonal qualities in psychosynthesis). He felt seen, held, and called by this environment; his spirit felt nurtured as a plant is nurtured by soil and sun, and he began to unfold a new branch of himself.

This relationship with the motorcycle world was the beginning of a process in which George gradually was to form a motorcyclist subpersonality. The motorcycle unifying center acted as a mirror, showing him hitherto unconscious potentials within himself that he could then work to actualize if he so chose. In Assagioli’s words, “When the unifying center has been found or created, we are in a position to build around it a new personality—coherent, organized, and unified” (Assagioli 1965a, 26).

What George did not realize at the time was that he already had within him an adventuresome aspect of himself, a part that was feeling called by the motorcycle unifying center. As a boy, he had hitchhiked with his father and had grown up listening to his father’s stories of his own youthful adventures hitchhiking and riding freight trains. As a young man, George too had hitchhiked, both through his own country and abroad, and he had always had a passion for travel, even working at various jobs that involved this passion. With the emergence of his professional career, however, this adventuresome spirit had languished until this awakening at the motorcycle rally.

THROUGH CHAOS TO ORDER

After some thought and planning, George finally bought a motorcycle and enrolled in a riding course—another important aspect of his newfound unifying center, which included his instructor, his fellow students, and the philosophy of the course. During the class he found that learning to ride involved mastering a number of different skills, including the use of the shifter, brake, clutch, and throttle, in addition to remaining aware of the road and other vehicles.

Early in the learning curve, he needed to focus intently upon these individual skills, seeking to master each of them in turn. But he found that when he gave his attention to shifting, he was not as aware of the road or the brakes, and when attending to the road and braking, that he could not use the clutch or shifter very well, and so on. He simply could not give every task the attention it needed to function as a smooth, stable, coordinated pattern.

Initially this process was extremely overwhelming and scary, but he felt sustained by his connection to the various elements of the motorcycle unifying center now working in his life; his respect for those centers, his desire to remain connected to them, and his determination to ride allowed him to persevere in his effort. Again, he felt called to motorcycling, even though he needed to move through significant amounts of anxiety, self-doubt, and pain to respond to that call.

However, over time, George gradually found that he did not have to focus so much on the mechanics of operating the motorcycle and that a new level of organization, a new synthesis, was emerging. The discrete behaviors that at first demanded so much attention began to function effortlessly and unconsciously—in the middle unconscious—leaving his consciousness free to enjoy the sights and sounds around him, and his will more free to choose how and where to ride.

Note that George’s process of learning is dynamically the same as all other structuralizations that he has achieved throughout his life. Even as an infant, through this process he learned to stick his thumb in his mouth and suck on it: “The product of this development—a smoothly functioning thumb-to-mouth schema—may go unnoticed once formed [i.e., unconscious]. But the process of formation, itself, will be quite salient and the focus of heightened attention” (Stern 1985, 60).

Like the infant learning to suck a thumb, the child synthesizing a new role, or Assagioli’s pianist moving from mastering technique to performing artistically (see Chapter 2), a structuralization of the middle unconscious began to support George’s conscious expression of new aspects of himself.

TRANSPERSONAL QUALITIES AND ARCHETYPES

Throughout this process George also found new transpersonal qualities emerging as he related to his motorcycling unifying center (again, this unifying center includes things such as his instructor, his fellow students, the philosophy of riding, and the entire motorcycling world). Besides the original qualities that had attracted him, he also began feeling a certain joy, freedom, and courage that were new to him. It was as if his relationship with the motorcycling unifying center became an axis around which a pattern of innate aptitudes, instinctual drives, learned skills, and transpersonal qualities was coalescing that made up his ability to become a motorcyclist.

He further recognized that this developing pattern in himself resonated with an ancient pattern in the collective unconscious, a pattern called the Warrior. He felt connected to this archetype when he was riding his motorcycle, feeling like a courageous warrior in facing the dangers and adventure of the open road. This archetype functioned as still another unifying center, one that allowed him to feel a kinship with heroes and explorers throughout human history.

A SUBPERSONALITY IS CALLED INTO BEING

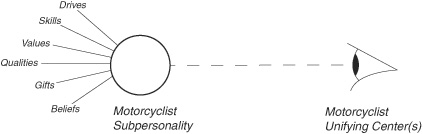

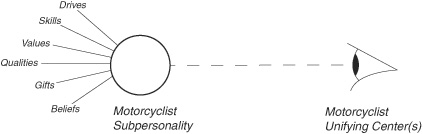

As George gained increasing experience with other motorcyclists and the motorcycle culture over time, this synthesis in him eventually developed into a discrete motorcyclist identity system. This new identify unified or synthesized the skills, gifts, drives, and qualities that he developed in riding, as well as particular beliefs and values concerning being a motorcyclist. The motorcyclist unifying center(s) in effect saw him as a motorcyclist and allowed him to see himself as a motorcyclist in turn, thereby supporting him in developing and unifying different elements into this unique expression of himself. The subpersonality arose from this relationship, with each side of the relationship playing its part. This process is illustrated in Figure 4.1.

From this new synthesis within him, he identified himself as a motorcyclist: he felt, thought, and viewed the world as a motorcyclist; he was alive to the sight and sound of any passing motorcycle; he viewed positive and negative comments about motorcycles in a personal way; and he even voted as a motorcyclist.

This new identity as a whole, then, came and went in his awareness—into and out of the middle unconscious—as appropriate. With nonmotorcyclist colleagues and friends, George’s new identity did not enter consciousness at all, while in a motorcycle environment it emerged into consciousness and full expression.

Note too that the motorcyclist unifying center here has been to some extent internalized, becoming an internal unifying center (Firman and Gila 1997). The existence of the subpersonality no longer depends solely on the external unifying center (Assagioli 1965a) but has an internal structure supporting it, whether or not the external motorcycle environment is present. We will further explore internal and external unifying centers in subsequent chapters.

George’s brief story reveals the birth of a subpersonality. Through a relationship with a unifying center(s), he felt called to develop a semi-independent discrete identity, a coherent synthesis of more basic elements, which could then move into and out of expression as needed. In George’s case, this subpersonality arose from an even earlier subpersonality that had emerged in relationship to his father, which he called the Adventurer. (In Figure 4.1, the Adventurer might be drawn within the Motorcyclist subpersonality.)

FIGURE 4.1

But whether a subpersonality develops early or late in life, we can imagine many different types of subpersonalities developing in much the same way as the Motorcyclist did. These different subpersonalities would arise in relationship to many different unifying centers—parents, siblings, school, profession, philosophical systems, religious environments, and the natural world (we will examine this developmental process more fully in Chapter 6).

Subpersonalities are called into being within our relationships to significant inner and outer environments that function as unifying centers for our experience. As we interact with these environments of meaning, we actively draw from the vast riches of our unique human potential, both learned and inherited, to form different unified, stable modes of expression. It is as if we are artists, our human potential is our palette, and subpersonalities are our creative expressions within particular environments (unifying centers). These creative expressions together, then, help form the larger system of the personality, that overall expression of ourselves in our lives as a whole.2

. . . each one of us has different selves—according to the relationships we have with other people, surroundings, groups, etc.

—Roberto Assagioli

Clearly, subpersonality formation seems a natural and healthy structuralization process of the human personality, a gift of the middle unconscious, the subsystems that make up the larger system of the personality as a whole. So why should we be aware of them, much less learn to work with them? The answer is that few subpersonalities escape primal wounding, and so often will have difficulty finding their authentic expression within our inner and outer worlds. Indeed, we often first become aware of subpersonalities because they are disrupting our lives in some way.

Accordingly, the following phases of personality harmonization begin with a survival phase—quite like the survival stage in the larger process of psychosynthesis—in which subpersonalities operate as defensive structures rather than free expressions of our true selves. The phases of personality harmonization are: (0) survival, (1) recognition, (2) acceptance, (3) inclusion, and (4) synthesis (modified from Vargiu 1974b).

To the extent that there has been an empathic responsiveness to us within our early environments—within early unifying centers—the subpersonalities and their relationships will be authentic expressions of who we truly are, together forming a larger personality that is authentic—in other words, authentic personality. But to the extent that empathic responsiveness is absent in our early environments, the subpersonalities and their relationships will embody strategies for surviving the primal wounding sustained in these environments, forming a personality devoted to this survival—in other words, survival personality.

For example, George’s motorcyclist subpersonality might have developed as a result of being shamed and rejected by his father—primal wounding. Here the motorcyclist subpersonality might be based on an earlier Angry Teen subpersonality, developing eventually into an Outlaw Biker identity. This Outlaw Biker would be fueled by a rage and rebellion in reaction to these inner feelings of low self-worth. The subpersonality would now not be a free and natural expression of George’s gifts and skills but a formation that manages primal wounding. This type of subpersonality might act out in a variety of ways, making it difficult to contact and heal the wounding.

Primal wounding can force any of our subpersonalities into a survival mode. Wounding might create, for example, not a parental subpersonality expressing our natural nurturing ability but a parental subpersonality who treats children as objects to fill a void of meaninglessness and loss. Or, instead of a lover subpersonality who expresses a gift for giving and receiving love, we might find a lover subpersonality who addictively uses relationships to stave off a sense of loneliness and isolation. Or, in place of a businessperson subpersonality expressing our highest values, instead there may be a subpersonality dominated by fear, greed, and self-centeredness.

Subpersonalities operating in survival mode are not natural expressions of our truest essential self or “I” but are dominated by the urgent necessity of managing primal wounding. Here our personality is rife with the rigidity, compulsions, and conflicts of the subpersonalities, and our consciousness and will are lost in these strong dynamics. In other words, we become chronically identified with, immersed within, the subpersonalities and so become unconscious of who we are. To the extent that this identification with subpersonalities occurs—and it seems to happen to each and every one of us to a greater or lesser degree—many different difficulties arise.

For one, subpersonalities in the survival phase place us at the mercy of the environment, because different situations will automatically trigger them in ways that may not serve us. Encountering an authority figure, we may unwillingly find ourselves becoming intensely hostile or overly passive—subpersonalities perhaps reacting to early abuses of parental authority. Or, as we begin to make an important speech, we may be filled with anxiety and have trouble even getting the words out—a young subpersonality still feeling the embarrassment and fear of childhood piano recitals. Or, facing the angry bullying of a partner, we may become frozen and unable to confront this emotional abuse—a helpless part of us going along in order to survive. Or, finally, attempting to become physically intimate with a lover, we may find ourselves inexplicably panicky or angry—a subpersonality reacting to early sexual wounding.

All such situations are ones in which the wounds of a subpersonality are impinged upon, automatically triggering learned survival reactions that may now be out of place and counterproductive in our lives. These reactions take place in spite of our will to do otherwise and in spite of our consciousness of a better way to respond. The subpersonalities are driven by primal wounding, and because of this powerful dynamic, they easily dominate and obscure our sense of “I.”

Another thing that happens when subpersonalities are driven by wounding is that the relationships among them become highly charged and conflictual. For example:

Beth reached out to her new friend with what she hoped was a humorous comment. But because she was fearful of rejection, the comment was forced and unnatural; the comment came out not humorous, but cynical and cutting, surprising and offending her friend. Alone later, Beth found herself in a terrible emotional state, feeling utterly ashamed and foolish. She angrily berated herself: “How could you have been so stupid? What a total idiot! Just keep your mouth shut next time.” She felt hopeless, and her dark mood lifted only gradually over the next several days.

In Beth’s case, she had a subpersonality who wanted to reach out to the new friend. But because of early experiences of rejection, the situation was profoundly clouded by an anxiety that caused a clash rather than a connection with the friend. Then a critical subpersonality took over, furious that the first subpersonality had made them vulnerable with the humorous comment. Further exploration revealed that the critical subpersonality also was afraid that being vulnerable in relationships would only lead to the hurts suffered in earlier relationships. In short, the wounding of the two subpersonalities caused a strong conflict within Beth, an interpersonal disconnection with her friend, and finally her depressed mood.

Much of our anxiety, depression, rage, and low self-worth often can be traced to such conflicts between subpersonalities, not to mention our everyday moods and ambivalences. For example, a risk-taking subpersonality may conflict with one who is seeking security; a relationship-oriented subpersonality might fight with a subpersonality who fears commitment; a subpersonality who wants to be liked may clash with one who wants to speak the truth; a student subpersonality’s desire to study might collide with another’s desire to go to the beach with friends; or a spiritual subpersonality may criticize the mundane practical concerns of a pragmatist subpersonality.

If there has been little or no wounding, we would expect minimal conflict among subpersonalities; conflicts such as those just listed, if they occurred at all, would be quite easily resolved as all of the various underlying needs were included in our lives as a whole. With wounding, however, such conflicts may become painful and even debilitating. Here subpersonalities operate from desperate, rigid positions, and mutual coexistence and cooperation are extremely difficult. Wounding creates a highly charged inner atmosphere that makes it difficult to have any sense of self from which to guide and express the parts in a coherent way.

Oddly enough, another problem with wounded subpersonalities occurs when they do not cause disruptions in our lives and instead operate smoothly to form survival personality. Here we move seamlessly among the subpersonalities over days, months, and years, never noticing that we are automatically adopting different and even dissonant patterns of thought and action in various situations. There is no thread of consciousness, no sense of “I,” which is aware of the subpersonalities as they move into and out of expression. Thus the subpersonalities live our lives for us; we live on automatic pilot, in a trance.

Such a survival personality can be extremely high functioning and successful by all social standards. However, achievements and possessions will ultimately fail to fulfill; relationships will be superficial; compulsions, obsessions, and addictions will abound (though these often will be well hidden); the underlying despair, anxiety, and emptiness will haunt us; and the heights and depths of human existence will be beyond our grasp.

Whether wounded subpersonalities are reacting extremely to events, fighting among themselves, or forming a well-functioning survival personality, their need to manage the wounding can dominate our lives. Our essential I-amness is buried; we are identified with, immersed within, the tumult and trance of the subpersonalities. So too we are distracted from uncovering and expressing our highest values, our ultimate concerns, and our more profound life directions—treasures to be found in relating to deeper Self. This type of chronic identification with subpersonalities is characteristic of the survival stage of psychosynthesis, and as we will see shortly, working through the phases of personality harmonization can be an effective way to engage the stages of exploration and emergence.

As discussed earlier, the transition out of the survival stage of psychosyn-thesis seems most often marked by some crisis of transformation that breaks through our status quo. In terms of subpersonalities in the survival phase, this can mean a subpersonality reaction that finally becomes too much for us, as perhaps a reaction to authority that endangers our job; or an anxiety or rage that disrupts our lives; or perhaps a powerful event—positive or negative—that shakes our world.

However it occurs, when this unconscious functioning is disrupted, we move toward empathically connecting to our subpersonalities and allowing them to become authentic expressions of who we truly are. We are then ready to move out of survival into the next phase of developing a relationship with subpersonalities—recognition.

After our survival mode is disrupted in some way, we can develop a careful mindfulness toward our ongoing inner experiences. This introspective focus leads to the discovery that our moods and passions and feelings and thoughts are not simply inexplicably random events but expressions of deeper organizing structures—subpersonalities. For example, we may, over the course of a day, find that we are feeling critical, then later on move from that experience into feeling loving, and then after some time has passed may find that we are feeling sad. But these are not simply fleeting, unpatterned experiences.

Tracing the experience of feeling critical, we may uncover a judgmental subpersonality, a part of us with a particular value system, specific emotional tone, unique history in our lives, and even a characteristic body posture and visceral sense.

Exploring the feeling of love, we may recognize a lover subpersonality, one who has over the years learned to love in a particular way, to have particular likes and dislikes, and to feel and act physically in certain ways.

Looking into our sadness, we may discover a younger, sensitive part that feels our pain and the pain of others, that believes the world is a desolate place, that remembers our losses, a part whose affect is melancholy and whose physical manifestation is a certain downcast of shoulders and head.

Here are subpersonalities within us, each with their own unique and abiding pattern of physicality, affect, thought, and behavior. They move into and out of our awareness from the middle unconscious (see Chapter 2), and they operate in our lives whether we are conscious of them or not.

This exploration into subpersonalities amounts to an emergence of the consciousness aspect of “I,” as described in Chapter 3. Here arises an ability not only to observe our passing experience but to see the patterns that organize this experience. Dynamically, the process of recognizing subpersonalities is quite like that stance adopted when doing meditation or contemplation in which we simply observe the passing contents of consciousness without becoming involved in them. The difference here is that instead of observing only the contents of consciousness, we are observing the organizing structures or contexts of our consciousness as well.

The starting point is the complete immersion in each subpersonality, with degrees of awareness of the incongruity of the situation. The goal is the freed self, the I-consciousness, who can play consciously various roles.

—Roberto Assagioli

By practicing this deeper mindfulness over days, months, and even years, we can learn to recognize and affect these abiding structures of our inner worlds. An expression of “I” thereby begins to emerge that is distinct-but-not-separate from both the contents and structures of consciousness; this emergence heralds a deeper engagement with and full expression of the many aspects of ourselves.

MANY PATHS TO RECOGNITION

Once we are willing to observe our experience in this mindful manner, recognition of subpersonalities may occur in any number of ways. Working with nocturnal dreams, we may realize that what appears as a threatening figure in a dream is actually a subpersonality emerging from the unconscious that can eventually add valuable new qualities to our lives. Or we may begin to feel phony or dishonest in realizing how radically different we are with different people, only gradually discovering that these are simply multiple parts of ourselves. Or perhaps other people will give us surprising feedback about our behavior: that our seemingly innocent comments have a cutting, hurtful edge to them, or that we hide a wonderfully creative or gentle side of ourselves, or that we always seem to become humorous whenever emotionally loaded issues come up.

In fact, when we become willing to become conscious in this way, it is quite easy to begin recognizing subpersonalities. It is important, then, in the recognition phase, to remember the principle of fractional analysis, discussed in Chapter 3. That is, the idea is not to uncover as many subpersonalities as we can, because this would simply tend to confuse and overwhelm us:

So recognizing most subpersonalities is hardly ever a problem. In fact it often takes less work to find new ones than to deal effectively with the ones we already have recognized. When people are first acquainted with the idea of working with subpersonalities, they often tend to do just that, becoming so fascinated with uncovering a teeming cast of thousands that the more fruitful work of understanding and integrating the central ones is neglected. (Vargiu 1974b, 77)

The aim in the recognition phase is not simply to discover all of our subpersonalities (even if this were possible) but instead to focus on those perhaps two to six that seem to be naturally emerging in our lives. This allows the exploration to remain meaningful and gives plenty of time to develop empathic relationships with each of them.

Subpersonalities often are recognized in counseling and therapy. Here, looking carefully at the deeper patterns underlying our lives, we will find the hidden world of subpersonalities. Let us look at Mark, who began to recognize two important subpersonalities.

MARK IN RECOGNITION

Here are the words of Mark, a twenty-seven-year-old graphic designer who entered psychosynthesis therapy struggling with a conflict between career and relationships:

I hate relationships. Well, not totally. At first it’s great, but then it begins feeling like they’re too much emotionally. So then I sort of let it fall apart, not doing much about it, and eventually it’s over and I can get back to my work. Yeah, work’s a pain sometimes, but at least I’m good at it. Then I start feeling lonely again, wanting someone.

In the above quotation, we can hear a work-oriented subpersonality and a relationship-oriented subpersonality who are in strong conflict with each other. As painful as this conflict is, Mark is at least somewhat aware of these two dissonant attitudes within himself. Formerly he had been caught in an unconscious survival personality pattern in which he cycled through periods dominated by work, then relationships, then work, and so on. During this time his partners were aware of mixed messages: at times his behavior would be saying, “I want to be close to you,” and at other times, “Go away and leave me alone.” Thus his inner conflict, even though he was not yet aware of it or its effects on his life, was causing hurt and confusion for other people.

For years Mark moved unknowingly between these two parts of himself, oblivious of the conflicting motivations within him. So in some ways this was inwardly a very harmonious time for him; he cycled unconsciously between career and relationships with no overarching awareness embracing both parts—no sense of “I” that could include these two inner structures of consciousness. When in one mode, he knew little about the other, so there was no sense of inner dissonance. The idea that he might have an inner duality would have seemed quite foreign to him at this point; if his contradictory behaviors had been pointed out to him, he might have argued quite honestly that he was simply acting differently at different times. These two subpersonalities were important elements in his survival personality, hiding the uncomfortable dynamics underlying his conscious experience; the subpersonalities were like atoms making up the molecule of the survival personality.

But as time passed, the repetitive pain of failed relationships grew, his loneliness became more intense, and his work began to suffer. Eventually the unconscious harmony of the survival personality was broken, and he entered a period of turmoil in which he began to encounter inexplicable feelings of loneliness, anxiety, and depression—a crisis of transformation, leading him toward hitting bottom. The intensity of his pain and confusion led him to consider the possibility that something might be happening within him that was causing this chronic, painful state of affairs. For the first time he began to consider that the problem may not be “relationships” or “the world” but something within himself, something of which he knew nothing at all.

Returning to Mark as he spoke the words quoted above, we can follow him as he begins to recognize the subpersonalities underlying his turmoil. The following occurred in the therapy session shortly after his earlier statement:

Therapist: So how does it feel when you’re lonely?

Mark: I don’t know, like it would be nice to have somebody and not be alone all the time.

T: Would you like to explore this a bit?

M: Sure, anything to get rid of it.

T: Okay, then, first, do you feel this loneliness in your body?

M: I guess so. Yeah, it’s like an ache in my chest, my heart.

T: Let yourself experience that if you are willing to.

M: It actually hurts a little. My chest and throat feel all tight.

T: If you’re willing to, let yourself keep feeling that, tune into it even more.

M: (Pause.) I feel a tightness all through here (indicates his chest area). It feels constricted. There’s tension in my neck and shoulders too. Feels hot.

T: Let yourself stay aware of this. Close your eyes if you want.

M: (Closes his eyes.) It’s just tight, tight, like a ball. It’s a little bit scary. Hmm, now I feel sad. That’s weird. Sad, real sad. It feels totally alone too. There’s no one. (A tear rolls down Mark’s cheek.)

T: Are there words?

M: Just that I feel real, real alone.

T: If you let an image come for that one who is alone, what would you see?

M: I just see this lonely guy in the dark, no one around. He’s got his head down in his hands.

T: How do you feel towards him?

M: He sorta repulses me. He’s like, wallowing in self-pity. He’s the wimp in me.

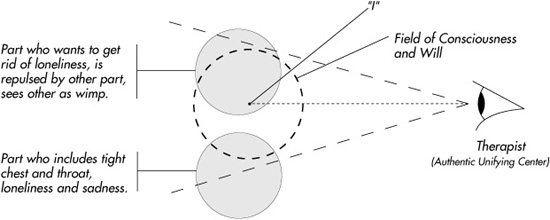

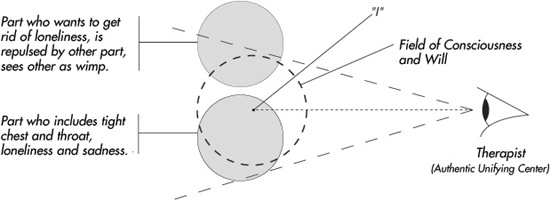

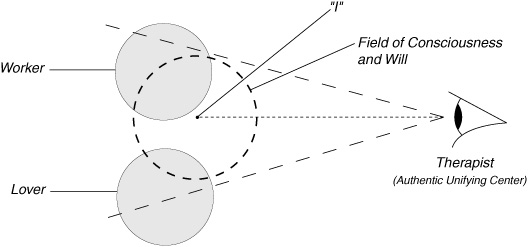

Mark has clearly recognized a part of him with feelings of sadness and loneliness, which at this point he called a wimp. To review the steps of this recognition, it began with his conflict between career and relationships, moved to his loneliness, and then to the physical sensations associated with the loneliness, and finally to the subpersonality who felt lonely. With guidance, here Mark has begun an intentional exploration into the depths beneath the surface layer of his conscious experience—the emergence of largely middle unconscious material into awareness. Mark’s inner experience at this point in the session is illustrated in Figure 4.2.

Here we see his personal essence—“I”—embedded within the part that dislikes the loneliness and sadness; that is, his consciousness and will seem to originate from within this part, conditioning how he views and responds to the lonely part (note that his field of consciousness and will extends only to the outer layer of the lonely part).

FIGURE 4.2

The therapist acts as an authentic unifying center, seeing Mark not as identical to either part but as one who is distinct but not separate from the parts. As we shall see, this empathic connection will allow Mark to actualize a potential for moving among the parts and working with them.

But Mark now faces the next phase in developing a relationship with a subpersonality—acceptance.

The phase of acceptance is the beginning of an empathic concern for the subpersonality, a beginning respect for the subpersonality “as a person,” so to speak. From a foundation of acceptance, an ongoing relationship with the subpersonality can grow, leading eventually to that subpersonality finding its place within the larger community of the personality as a whole.

Note, however, that acceptance of a subpersonality does not necessarily mean condoning or allowing its behavior. Often acceptance of a subpersonality is like the acceptance shown by an experienced schoolteacher toward a problematic student: the teacher establishes an empathic bond of trust and respect but sets limits on disruptive behavior, thus allowing the student a safe relationship within which to grow and change. So, for example, subpersonalities who feel impelled to act destructively out of their rage or anxiety may need help in working with their behaviors.

Without this type of empathic acceptance for the various parts of ourselves, we will be ever at war with them, and they with us. As we return to Mark, it becomes clear that he is being challenged in the acceptance phase.

MARK IN ACCEPTANCE

At the point where we stopped in Mark’s session above, he is repulsed by the part that was feeling lonely and sad. Acceptance clearly is not yet present, as exemplified by the pejorative word “wimp” itself. When this type of tension is found in a relationship with a subpersonality, acceptance will need to emerge if the inner conflict is to be ameliorated. We pick up the session at the point where Mark is feeling repulsed:

M: He sorta repulses me. He’s like, wallowing in self-pity. He’s the wimp in me.

T: How does he respond to you saying that?

M: He just hangs his head and turns away.

T: How does that make you feel?

M: That’s fine with me. Who needs him? He’s the one always wanting to be with people and getting us in trouble. I’d rather just focus on my work. That’s what’s important.

T: Try something, Mark. Imagine for a moment that you can become him. Actually enter into him, become him, feel what he feels.

M: (Pause.) Okay, I’m the wimp.

T: How do you feel?

M: Hmm. Sad, lonely, and pissed at that Worker guy for saying those things. The hell with him. Let him work and die alone, for all I care.

T: Tell him that.

M: I did, and he’s surprised. He didn’t think I had it in me (chuckles).

Since the therapist is holding Mark as distinct but not separate from both parts, Mark is free to move from his initial identification into the experience of the lonely part in order to get to know this subpersonality better.

This shift of identity is illustrated in Figure 4.3, in which “I” is shown located now within the lonely part. He is now conscious and willing from within the lonely part. From this new perspective, he is, in effect, looking at the former identification, the part he has now named “that Worker guy.” Through this shift, Mark has further discovered some of the inner experience of the lonely part, uncovering anger as well as loneliness and sadness.

Let us now return to the session, as the therapist invites Mark to continue his exploration by shifting his perspective between the parts. Note again that such an invitation can be extended because the therapist is still focused on Mark as one who is distinct but not separate from both parts, that is, “I.”

T: Okay, now become the Worker guy again. How do you feel towards the lonely guy now?

M: Well, yes, surprised he’s got so much umph. I guess he’s not a wimp after all. I sort of respect him for that.

FIGURE 4.3

T: Ask him what his name is.

M: He says he’s the Lover.

T: How is it to hear that?

M: Good. It’s sure different than “wimp.” He sounds interesting.

T: Want to go a little further with this?

M: Sure.

T: Okay, try stepping back from the Worker and the Lover, so that you can see both of them. What do you see?

M: (Pause.) I see two guys facing off each other. (Chuckling.) The Worker’s real intense, sweaty, with his sleeves rolled up. They’re in a stalemate. (Pause.) I guess that’s where I’ve been for a long time now, right? Whew.

T: How do you feel towards them?

M: Good. Sort of fatherly. Compassionate.

As Mark discovered, he had begun the session identified with the Worker subpersonality; his sense of “I” had been merged with the viewpoint of the Worker. Identified with the Worker, he couched his problem as a conflict between himself and the problematic subpersonality later revealed as the Lover. From this initial identification, the Lover was “the problem” rather than the issue being the conflict between two parts of him.

However, disidentifying from the Worker and entering into the Lover (Figure 4.3), he could then directly contact the world of the Lover, fully experiencing the sadness, loneliness, and finally the anger toward the Worker. Then, as he disidentified from both the Worker and the Lover (illustrated in Figure 4.4), he found an inner stance that could accept and include both the Worker and the Lover.

FIGURE 4.4

Through disidentification, Mark finds a position from which he can connect empathically to each part more deeply, facilitate their relationship, and eventually move toward a resolution of their conflict. His sense of identity is no longer caught up in either part, and he is free to extend his consciousness and will to each part as needed. Paradoxically, this allows him to uncover heights and depths in both parts that would have remained hidden by an identification with either of them. Again, this is facilitated by the therapist seeing Mark and not simply the two parts or their conflict.

. . . the observer is not that which he observes.

—Roberto Assagioli

NAMING SUBPERSONALITIES

Note that names for the subpersonalities emerged as the session progressed, following closely Mark’s own descriptions of them. Naming can be an important step in developing an ongoing relationship with subpersonalities, as can learning the name of someone new in our lives. An infinite variety of names seems to exist for subpersonalities, for example, The Student, The Judge, Supermom, The Mystic, The Thrill Seeker, Savior, The Pragmatist, The Crone, The Jock, Dreamer, Guardian, or Thinker.

It is important when naming subpersonalities, however, to keep in mind that the purpose is to develop an empathic relationship with these parts of ourselves. For example, inaccurate or demeaning names will need to be changed over time as recognition and acceptance deepen. Nor is it helpful to objectify subpersonalities by the use of standardized labels or categories for them; again, the focus is on respect for the uniqueness of each part.

SUBPERSONALITY TECHNIQUES

Note that Mark’s approach to his subpersonalities via body sensations, imagery, feelings, and dialogue is only one way that such work can be carried out. For example, one might act out the two parts and their relationship in the form of a psychodrama; or, as in Gestalt therapy, use pillows or chairs to represent the two subpersonalities, moving physically between them as the relationship develops (psychosynthesis would add a third chair representing the disidentified point); or move nonverbally among the different positions exploring the experience through the body alone; or develop a relationship with the parts using painting, clay, drawing, writing, or small figurines, as in sand tray work.

Subpersonality work can be carried out using a tremendous variety of techniques drawn from virtually the entire spectrum of different schools of psychology. In fact, individual practitioners who understand the overall process of subpersonalities have frequently created their own techniques on the spot to meet the specific needs of a particular client.

Given the variety and availability of techniques, finding a technique usually is not a problem. Problems can arise, however, if we become distracted by the techniques and forget the purpose they are to serve: to begin developing an empathic relationship with these various aspects of ourselves. Let us now move on to the third phase of personality harmonization—inclusion.

Once we have recognized and accepted a subpersonality, we are in a position to receive that part into our personality as a whole, to welcome it as a valuable aspect of who we are, and to allow it to become a part of our lives. This involves an even deeper level of empathic connection, a phase that we have called inclusion.

A key to beginning the inclusion phase is to become increasingly intimate with the subpersonality so that we begin to move beneath its superficial presentation to the deeper needs that motivate it. We can see this deepening of empathy as Mark’s individual session continues:

T: How do you feel towards them?

M: Good. Sort of fatherly. Compassionate.

T: Ask the Worker what he wants.

M: He says he wants to work, work, work, to get ahead, to make something of himself. He’s very strong.

T: How do you feel about that?

M: I like his drive, but he’s sorta got tunnel vision.

T: Tell him that, how does he respond?

M: He likes being liked.

T: Ask him what he most essentially needs from you.

M: He says he needs me not to forget him, to let him create and express. Also it seems like he’s scared somehow about not making it in life.

T: Okay, now turn to the Lover and ask him what he wants.

M: He says he wants the Worker to go away. Forever.

T: How does that make you feel?

M: Kinda sad. The Worker seems an okay guy.

T: How does the Lover respond?

M: He gets it in a way, but doesn’t know what else to do.

T: Ask him what he needs from you.

M: He says he just needs me to be with him, not to judge him.

T: Are you willing to meet these deeper needs they have?

M: Sure, especially if they’ll stop fighting.

T: How are they doing now?

M: They’re both just standing there. They’re more relaxed. Tolerant of each other. They’re glad I’m here.

Here there is a movement from the more surface level of behaviors and wants to the more essential level of needs. Contacting this deeper level means that Mark is not faced with the impossible task of dealing with the Worker’s rigid demand for “work, work, work” and the Lover’s impossible demand that the Worker “go away forever.” Instead, Mark can deal with the much more flexible need of the Worker, “to create and express,” and the Lover’s, “to be with me.” His empathic connection here reaches beyond the surface to the depths of the subpersonalities, touching a level at which right relationships can be formed.

This stance—of Mark relating to each subpersonality in an empathic manner—is fundamental to the inclusion phase. He is not so much addressing the relationship between the subpersonalities as he is establishing a direct connection with each one from a more objective and compassionate point of view. The subpersonalities do not have to trust each other at this point; they only have to trust Mark. It is this direct empathic connection that will allow each to heal and grow, to be included in the personality, and eventually, in the next phase of synthesis, to perhaps come to a new, creative relationship with each other.

LIVING WITH THE SUBPERSONALITY

Mark has done some fine work in this session, but if his transformational experiences with the subpersonalities are to actually manifest in his life, his active involvement with them will need to continue into his daily living; subpersonalities do not disappear when the session is over! In fact, it can be said that in a session we only glimpse potential, creating a template or pattern for possible change, and for this potential to actualize, this pattern must be acted upon, made manifest.

Such active manifestation is termed grounding (Vargiu 1974b), because insights and experiences from sessions are hereby grounded in ongoing daily living. Lack of attention to grounding is a criticism often leveled at psychotherapy in general, to wit, that psychotherapy only produces insight without any meaningful life change. However, grounding bridges insight with action, new experiences with ongoing experience, sessions with daily life.

In Mark’s case, he maintained a mindful stance toward the Worker and Lover over the course of his day. This involved some amount of time-sharing (Vargiu 1974b) between the two subpersonalities, as he made sure each had some share of time in his life. Devoting quality time to the Worker, he was able to become more creative and expressive at work, and maintaining contact with the Lover, he was increasingly able to find times in which to enjoy his friendships and to begin to date once again.

However, the simplest and most frequent way in which we discover our will is through determined action and struggle.

—Roberto Assagioli

This time-sharing was not easy, because there were periods in which he became lost once more in the Worker, becoming obsessed with work and ignoring relationships. This put him back into the conflict with which he began, but at least he knew where he was, how he got there, and how to proceed. Invariably this involved him reconnecting with the Lover, saying he was sorry, and then making amends, usually by giving the Lover (and so himself) more quality relationship time.

The ways that people find to include subpersonalities in their lives are as numerous as the subpersonalities themselves. From taking a nature-loving one to the ocean or the mountains; to buying art materials for an artistic part; to taking a class, playing a sport, or learning a craft; to challenging a friend whose remarks are hurtful to a vulnerable subpersonality; to watching particular films or reading particular books; to beginning to be aware of, and to express, one’s feelings; to simply being with subpersonalities when they are in need—all such concrete actions, infused by empathic concern, are ways of including the many parts of ourselves in our lives. Such acts represent a commitment to change our lives in concrete ways so that all of who we are can find the space to live and express—the burgeoning of authentic personality.

THE HIGHER AND LOWER UNCONSCIOUS

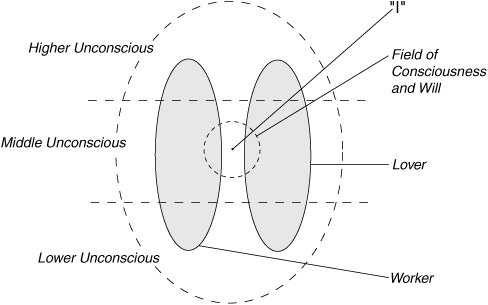

For Mark, this type of ongoing empathic relationship involved getting to know his subpersonalities at even more profound levels of intimacy, uncovering their roots in the higher and lower unconscious.3

Relating to the Worker, he learned about the abuse suffered at the hands of his hypercritical and demanding father. Mark could never do enough to gain his father’s respect, and the compulsivity of the Worker was an attempt to manage the pain of this primal wounding (lower unconscious material) by working harder and harder. But, too, Mark could now discover the gifts of personal integrity, self-respect, and power in the Worker, a contact with the higher unconscious that allowed him to meet his deadlines in a creative, more relaxed way. At one point, he reported that his work no longer felt like “a matter of life and death.”

Relating to the Lover, Mark found many memories coming to him from his high school years, experiencing feelings such as shame, isolation, and grief, which took him eventually to early childhood memories of emotional and physical abuse—an exploration of the lower unconscious dynamics underlying the Lover. But as this empathic relationship with the Lover continued to grow, the Lover also became much more able to express qualities such as sensitivity, humor, and play, which long ago had been hidden away in the higher unconscious. His relationships became relatively free of the desperate push from the underlying loneliness and much more lighthearted and fulfilling as these transpersonal qualities were given expression.

Using Assagioli’s oval-shaped diagram, the higher and lower unconscious areas of these subpersonalities might be represented as in Figure 4.5. This diagram illustrates that both the Worker and Lover contain aspects of themselves in the higher unconscious and lower unconscious. As Mark disidentified, he could empathically connect not only with the immediate manifestations of these subpersonalities in the middle unconscious but could reach as well to their heights and depths. His consciousness and will were free to relate to each and to guide each.

FIGURE 4.5

So rather than Mark unconsciously bouncing between these two parts of himself, or suffering their intense conflict, he now began to experience them as valuable modes of self-expression that added richness to his life. Formerly, the transpersonal qualities had been split off, repressed, and blocked by the conflict; now, with Mark’s sense of “I” playing an active, nurturing role, these two subpersonalities began to unfold.

The phases of recognition, acceptance, and inclusion seek to establish a direct, one-to-one, trusting relationship with a single subpersonality and to include it consciously within the personality; this holds true even when working with more than one subpersonality at a time, as Mark was doing. Although the first three phases may involve ameliorating a conflict between subpersonalities, this is done primarily to give each subpersonality a safe, nonconflictual space in which to heal and grow. This is an important principle, because often subpersonalities need to develop into their own unique identities before exploring their relationship with other subpersonalities.

Although there is not often a clear boundary between inclusion and synthesis, we might say that to the extent a subpersonality has blossomed within the secure holding of our empathic concern, it is ready to explore a more creative relationship with other subpersonalities—the phase of synthesis. This phase has to do with how subpersonalities interact with each other, how they may work together to form a more harmonious inner and outer expression of the personality as a whole. Clearly, this can happen only to the extent that the subpersonality is secure in its deeper connection to “I” and its place within the family of the personality.

SYNTHESIS AS A CONTINUATION

Working with subpersonalities will not only reduce feelings such as anxiety, anger, and depression created by inner conflicts, not only heal these parts of us and unlock their treasures, but gradually may allow a new synthesis to emerge among the parts. Just as discrete learnings and gifts are brought together to form a subpersonality, so the subpersonalities themselves may be brought together to form a larger expression. That is, it is possible to look toward an even more developed pattern arising from an intimate communion among the parts.

For example, as the Lover and Worker resolve their conflict and begin to trust each other, they may begin to appear together in certain situations. At work, Mark might find that the Lover brings a certain playfulness and interpersonal sensitivity to his relationships with coworkers and clients, making work much more enjoyable and productive. In his social life, Mark may discover that the Worker’s qualities of integrity and self-confidence are quite helpful, creating a much more pleasurable and satisfying experience.

This communion or “dance” between the two parts may eventually give birth to a new subpersonality, who might be called the “Artist.” This new subpersonality will be able to manifest the qualities of both the Lover and the Worker within a single expression. For example, the Artist might be extremely focused on a project while at the same time sensitive and responsive to the people around him; or the Artist, in synthesizing initiative, planning, and love, might allow Mark to express his caring and concern in creative ways, truly touching the people he loves. Here the two subpersonalities work together to create a larger conscious expression, embodying potentials that neither could manifest alone. A synergy between the two creates a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts.

Note that this process of synthesis is again the same one that we have seen from the earliest months of life. Mark’s bringing together the Lover and the Worker in a coherent expression is dynamically the same as the infant synthesizing various schema into a smooth, thumb-to-mouth behavior, or bringing together different experiences into a coherent sense of self and other, or Assagioli’s piano player developing from technique to artistic expression. In this process of synthesis, prior structures can become elements within a larger whole, forming a broader expression of who we are.4

SUBPERSONALITIES ARE PRESERVED

It is important to note in the phase of synthesis that as we begin to express this communion of subpersonalities, we may not be as directly conscious of the individual subpersonalities as we were in earlier phases. The reason for this is quite simple—the middle unconscious. What happens in such a synthesis is that our awareness shifts to a level of expression that the subpersonalities support from behind the scenes, from within the middle unconscious. But it is not that the subpersonalities have disintegrated and disappeared. The Artist does not demand the extinction of the Lover and the Worker any more than a sports team demands the extinction of the players or an orchestra demands the extinction of the musicians. In fact, the synthesis or team can only manifest as the individuals maintain their own individual integrity. Synthesis implies that individuality at all levels is preserved.5

This notion of synthesis-as-community holds too when this team is not based on the especially close interplay seen between the Lover and the Worker. Often the new synthesis may be simply a generalized pattern of personal coherence in which subpersonalities cooperate in the living of a single life (this can be true for people with true multiple personalities, for example). This would be the case if Mark remained able to shift between the Worker and the Lover as needed and, similarly, among all of his other subpersonalities.

Any appropriate shifting among various parts implies synthesis, an esprit de corps, a higher-order organizing principle operating among the parts. Here there are less debilitating inner conflicts and more fluidity and responsiveness, which again indicate the emergence of a team or community with an overall life direction. In short, synthesis and psychological health do not demand some seamless fusion of all of the parts but rather the parts form a cooperative community in which the gifts of each of the parts are recognized, valued, and included within a meaningful life direction.

Having said all of this about the preservation of subpersonalities, we must add that there are times that can be characterized as the death of a subpersonality. This occurs when there is a subpersonality whose structure must de-integrate so that a new structure may arise. Often this seems to involve a subpersonality who has been highly structured and focused on a particular role or function, a role or function that the subpersonality no longer needs to fulfill. These times can be poignant, involving an appreciation for the service of that part and a grieving of its passing. Of course, the talents and skills of the old form will then become available in the growth of a new structure, so this is in fact a death and a rebirth. Nevertheless, the pain and grief are quite real and need to be engaged as this transformation proceeds. Even subpersonalities can have crises of transformation.

Here the biological analogy is illuminating: there is no material fusion of organs or apparatus of the body—they remain anatomically and physiologically distinct—but their fusion is a functional unity.

—Roberto Assagioli

Finally, the phase of synthesis implies an overall expression of the personality that is in alignment with the deepest currents of meaning in our lives (i.e., the expression of authentic personality). Just as a subpersonality discovers a unique part to play within the whole personality, so we may look to discover the unique part that we can play in the unfoldment of life around us. By analogy, it is as if we each are subpersonalities within a larger personality—whether a friendship, couple, group, or the world at large—and have a unique place within this larger whole, a call or vocation to express our gifts within this wider arena. To speak of this call, of course, is to speak of Self-realization, a developing relationship with Self in all aspects of our lives. We have outlined Self-realization in our discussion of the stages of psychosynthesis in the previous chapter, and we shall again take up this subject in Chapter 8.

But now let us turn our attention to the one who emerges in subpersonality work, the one who can be present and responsive to any and all subpersonalities—our essential identity, “I.”