The Carmelites

The new form of Carmelite imagery to emerge in the Netherlands and Germany towards the end of the fifteenth century was to depend heavily on the viewer’s fundamental understanding of Tree of Jesse iconography. A Carmelite legend of a vision on Mount Carmel shared many characteristics with the prophecy of Isaiah, and by drawing on traditional Tree of Jesse representation, the Carmelites were able to reinforce the myth surrounding their claim to a special relationship with the Virgin and her mother Saint Anne.

The Carmelites rose to prominence in Europe in the thirteenth century, yet their origins were not in the West. Their name derives from Mount Carmel, a holy site in the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem, now Syria, which had been identified from the fourth century as the mountain from which the Old Testament prophet, Elijah, had brought down fire on the men of King Ochozias.3 The first Carmelites were a community of hermits who had established themselves on Mount Carmel, living a life of solitary contemplation in emulation of the anchoritic example set by their patron Elijah. Attacks on the kingdom of Jerusalem by the Saracens eventually forced many Carmelites to emigrate to the West, and by the mid-thirteenth century they were living in urban centres. Consequently, their contemplative life was replaced by an active one, similar to that of the other mendicant orders. Despite attempts to have the Order suppressed by the Council of Lyon in 1274, the Carmelites received papal approval in 1286, the year they also adopted their distinctive white mantle. Finally, in May 1298, they received official endorsement from Boniface VIII.

During this period the Carmelites had already established themselves in several towns and cities in Germany. Their first settlement appears to have been founded in 1259–60 in Cologne, closely followed by houses in Boppard and Frankfurt.4 By 1291 there were approximately fifteen houses in the upper Rhineland alone. By contrast, fewer houses were established in the Netherlands, although communities did exist in Brussels, Bruges, Mechelen and Haarlem in the thirteenth century, and new foundations continued to be established in both countries throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.5

Unlike the Dominicans and Franciscans, the Carmelites lacked a famous founder and, in order to help formulate their identity, they were keen to promote their claim to an ancient and distinguished heritage. This claim, one that went right back to Elijah, was disseminated in a series of short historical treatises from the end of the thirteenth century.6 Furthermore, the Order also alleged a special relationship with the Virgin, adopting the title fratres ordinis beatae Mariae de Monte Carmeli, which had been officially conferred by Pope Innocent IV in a papal bull of 1252. The number of Marian feasts celebrated by the Order increased significantly during the fourteenth century. In 1306, following Franciscan practice, the Carmelites celebrated the feast of the Conception of the Virgin; in 1342, Marian devotions were extended to include a daily mass to the Virgin.

As the mother of the Virgin, Saint Anne acquired a special status for the Carmelites, and from the late thirteenth century onwards her feast was celebrated by the Order on the 26th July.7 As we have seen in the previous chapter, texts dedicated to the life of Saint Anne spread rapidly throughout Germany and the Netherlands in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Among her many promoters were a number of distinguished humanist scholars, including the Carmelite Arnold Bostius from Ghent (1446–99).8 Although the Carmelite humanists numbered no more than twenty or so, Bostius’s influence, both directly and indirectly, on members of the Order and the larger humanist circle outside, was considerable.9 Bostius’s Speculum Historiale, written some time before 1491, wove together the story of the Order’s origins with the legend concerning a vision on Mount Carmel.10 According to this narrative, the first Carmelites, the devout hermits who lived on Mount Carmel, were regularly visited by a young girl, Emerentiana, the mother of Saint Anne. When her parents decided she was old enough to marry, Emerentiana went to the hermits for advice; they prayed for three days and were finally rewarded with a vision. In this vision they saw a beautiful tree with many branches, yet one branch was far more beautiful than all the others and bore an exquisite fruit, from which an even more beautiful flower bloomed. A celestial voice explained the vision to the hermits: the tree represented Emerentiana’s marriage, the one beautiful branch symbolised Emerentiana’s future daughter, Anne, whilst the fruit on the branch signified Anne’s future daughter, Mary, a virgin, who in turn would give birth to the flower, Christ. Parallels with Isaiah’s prophecy are obvious, yet Emerentiana has replaced Jesse as the root of the tree that ultimately produced the flower of Christ. Other contemporary texts further propagated this legend and, according to Ton Brandenbarg, some authors even referred to Emerentiana as the ‘root of Jesse’.11 The other branches on the tree were meant to represent Emerentiana’s other descendants, who were to help promote and support the kingdom of God.12

The concept of the Virgin as a branch sanctified on the root of Jesse had been widespread among Carmelite theologians from as early as the fourteenth century, and John Baconthorpe (died c.1348) had summed up the notion in his maxim ‘virgo fuit concepta ex semine David sanctificato’ (the Virgin was conceived from the sanctified seed of David). This idea was expressed even more eloquently by the Carmelite theologian FitzRalph, in his sermon for the Feast of the Conception in 1342:

Most pious lady… I believe and acknowledge, since you, the most beautiful branch, gave birth to and brought forth the lasting flower from the root [of] Jesse, but through this, from you… by means of that flower we are liberated from the sin of original man.13

By 1369 a special Marian hymn, known as the Flos Carmeli (Flower of Carmel), had also become popular.14 In addition, the Tree of Jesse came to be associated with the life of Saint Anne in Carmelite liturgy. This is evident from a late fourteenth-century missal from the Carmelite convent in London (British Library, Add Ms.44892, fol.165r).15 The feast of the Conception of the Virgin is illustrated with scenes from the lives of Joachim and Anne, while the first verse of the prophecy of Isaiah, ‘egredietur virga de radice Jesse’, is used as the alleluia versicle of the grail of the Conception Mass. Given this established association, any visual representation of the vision on Mount Carmel was also likely to reference the Tree of Jesse, and it is unsurprising that the two themes became intertwined in Carmelite imagery.

A mendicant order incorporates individual and collective poverty into its rule and, consequently, is dependent on secular donations for its livelihood. A lucrative source of income in the late medieval period were the confraternities or brotherhoods that were linked to the monastery churches.16 These confraternities had several functions and played an important part in the religious life of towns and cities. Not only did they provide the opportunity for members to perform pious acts, thereby easing their journey into the next life, but also members believed that mutual benefits could be gained from the prayers and devotional activities of their fellow members. Furthermore, through regular meetings, confraternities provided a forum for social networks, allowing members the opportunity to make valuable contacts. Members would pay a subscription in return for the spiritual administration of their brotherhood, which included the saying of regular masses, celebration of special feast days and praying for the dead. Additional donations were made via indulgences and endowments, and members also commissioned works to decorate their chapels.17 Confraternities tended to adopt a holy patron and Saint Anne was a popular choice for many such organisations, particularly from the latter part of the fifteenth century. This appears to have been linked to a large extent to the activities of the Carmelites, who, having identified the economic potential of such brotherhoods, seem to have actively encouraged them. This has been corroborated by Angelika Döfler-Dierken, whose study of the emergence and spread of Saint Anne brotherhoods in Germany revealed how influential the Carmelites had been in their proliferation.18 In addition, she ascertained that few confraternities were established prior to 1479, but that their numbers grew rapidly after this period, reaching a peak between 1495 and 1515, when records show approximately 241 brotherhoods dedicated to Saint Anne. Döfler-Dierken’s findings have been supported by Virginia Nixon, who, when looking at the introduction of the cult of Saint Anne in Augsburg, discovered that the Carmelites’ financial problems in 1494 were a major factor in their decision to introduce their Saint Anne Brotherhood.19

The Frankfurt Brotherhood of Saint Anne

One of the most influential confraternities was established by the Carmelite Order in Worms and included among its members not only the bishops of Worms, Mainz, Trier and Cologne, but also the Emperor Maximilian.20 Despite this, it was the Frankfurt confraternity that was to become the largest and most important.21 In 1479 the prior of the Frankfurt Carmelite monastery, Rumold von Laupach, applied to incorporate a confraternity of Saint Anne into the brotherhood of the Order, and its foundation followed in 1481.22 Formal consent was given by Pope Innocent VIII in 1491, although it was only officially ratified by the archbishop of Mainz in 1493.23 This was also the year that the monastery acquired a fragment of Saint Anne’s arm from the Benedictine monastery in Lyon. A document from the church archive provides us with further details regarding the acquisition of this relic and suggests that the Frankfurt Brotherhood were able to obtain it with the help of merchants from the Netherlands.24 Fur thermore, the document demonstrates how the concept of a genealogical tree of Saint Anne was a familiar metaphor in Carmelite circles. The author argues that the relic should be transferred to the Carmelite monastery because of the Carmelites’ special relationship with the female ancestors of Christ, and equates Saint Anne with a fruitful tree, ‘We judged it to be thus far most worthy… that fruitful tree that produced such abundant and healthy fruit’.

Laupach went to great efforts to promote his confraternity and commissioned Johannes Trithemius, the abbot of the Benedictine monastery at Sponheim, to write a eulogy in praise of Saint Anne. Trithemius’s De Laudibus sanctissime matris Anne was then followed by a text by Johannes Oudewater that discussed the history of the Order. This text, the Liber trimerestus de principio et processu ordinis carmelitici, also mentioned the Frankfurt Brotherhood of Saint Anne, thereby advertising the confraternity throughout the Rhineland and Saxony.25 Laupach was a central figure in both texts and consequently his confraternity grew very quickly; by 1497, membership had reached 4,000.26 This is an astonishing number, particularly when we consider that the total population of Frankfurt at this date was only about 10,000.27 Given the location of the Carmelite church, in the western part of Frankfurt near the trade area in the Römerberg district, it appears that membership numbers were swelled to a great extent by the large number of merchants who visited Frankfurt during the biannual trade fairs held in the spring and autumn. Saint Anne was a popular patron for merchants, as she was seen as a protector of those who undertook hazardous journeys, and several of her supposed miracles concern merchants and shipping.28 In addition, a number of rich patrician families lived in the area between the Römerberg and the Carmelite monastery, and it seems that they too became members of the Brotherhood.29 The huge success of the confraternity was clearly a concern for the local clergy, who were anxious that their income was being diverted. Trithemius, in De Laudibus sanctissime matris Anne, discusses this potential problem, but defends the Carmelites, stating that townspeople would turn to them only if they were not being taken care of properly by their own parish priests.30

The Brotherhood of Saint Anne initially had to share a chapel in the Frankfurt Carmelite church with the Confraternity of Saint George. However, as their numbers grew this was no longer feasible and money was raised by its members to build a dedicated chapel. In 1489, the cardinal legate, Raimund Peraudi, granted a hundred-day indulgence for visits and donations for the construction of the chapel and, on the 3rd April 1494, a new chapel between the choir and transept, next to the sacristy, was consecrated by the archbishop of Mainz.31 The new Saint Anne chapel, with its important relic, was considered a significant religious site, and documents from the church archive record that the confraternity received further indulgences following the visits of various bishops.32 This was apparently followed by a visit from the main dignitaries of the Empire, including the Emperor Maximilian and his wife.33

The new chapel required an altarpiece, and there is convincing documentary evidence to suggest that the sixteen panels from the wings from a large retable, now preserved in the Historische Museum in Frankfurt, originally came from this chapel (Figures 3.1 and 3.2). An official agreement which discusses mutual rights and duties, dated the 8th September, 1501, between the Brotherhood and the prior of the Carmelite monastery, Philip von Nuyß, makes reference to an altarpiece already situated in the chapel:34 ‘Die kunstlich tafel vff dem altare in der selben capellen und ein monstrantzien zu sant Annen heyltum, alles vß der gemeynen bruderschafft und unser mithulffe… vff gericht’ (The retable from the altar in the same [Saint Anne] chapel and a monstrance containing Saint Anne’s relic, all the property of the brotherhood [with] our [the Frankfurt Carmelites] help).35 Furthermore, in 1867, Phillip Friedrich Gwinner referred to eight panels, painted on both sides and subsequently separated, that featured the Legend of Saint Anne.36 These he claimed were the wings of a late fifteenth century altarpiece from the Carmelite church, which came into the possession of the town of Frankfurt following the secularisation of church property in 1802–3. According to Koch, Laupach’s last will and testament also stated that the prior had honoured the parents of Saint Anne by means of a retable.37 Although this document is now lost, it gives further support to the hypothesis that the wings were originally from an altarpiece in the monastery church. As Laupach died in 1496, we can assume that the panels must have been commissioned sometime before his death and may have even been in place by 1494.

Figure 3.1 Frankfurt Altarpiece of Saint Anne from the Carmelite Monastery, Interior Wings, Anonymous Flemish Master, c.1495

(Individual Panel Size: 91.5 × 52.5 cm) Historisches Museum, Frankfurt am Main (Photo: Horst Ziegenfusz)

The iconography of the wings provides a fascinating example of how the legend of Saint Anne was linked with the myth of the vision on Mount Carmel to produce a powerful piece of Carmelite propaganda, even though funds to pay for the work must have been raised by the lay confraternity.38 Each wing is comprised of eight panels, four on the interior and four on the exterior. The complexity of their icono-graphic programme clearly indicates the involvement of a Carmelite theologian or scholar, in all likelihood Rumold von Laupach himself. Although the museum currently attributes the wings to a Flemish master, whom Guy de Tervarent believed was perhaps a successor to Rogier van der Weyden, Gwinner attributed them to a lower German master, and there are stylistic similarities with Cologne painting of a similar period.39 Unfortunately the middle section of the altarpiece is now lost, although it is assumed that it probably contained a carved shrine, possibly a representation of the Holy Kinship.

Figure 3.2 Frankfurt Altarpiece of Saint Anne From the Carmelite Monastery, Exterior Wings, Anonymous Flemish Master, c.1495

(Individual Panel Size: 91.5 × 52.5 cm) Historisches Museum, Frankfurt am Main (Photo: Horst Ziegenfusz)

The top left panel on the interior of the left wing, clearly appropriates Tree of Jesse iconography in a manner similar to the Tree of Saint Anne images discussed in the previous chapter. Replacing Jesse at the base of the tree in this instance however, is Hismeria, the apocryphal elder sister of Saint Anne, who is richly dressed and identified by an inscription at the foot of her large gothic chair. From her shoulders grow the roots of two branches; in a flower blossom to the viewer’s left is her daughter, Saint Elizabeth, with her son John the Baptist directly above her. On the right branch, is Hismeria’s son, Eliud, and above him, his son, Eminen. Directly above Hismeria, encircled by tendrils from both branches, sits Eminen’s descendant, Saint Servatius. Saint Servatius is dressed as a bishop and, besides a crosier, he holds two silver keys which according to legend were given to him by Saint Peter. As discussed in the previous chapter, Saint Servatius was the fourth-century bishop of Tongeren and archbishop of Maastricht on the Meuse and, as such, was particularly venerated in Germany and the Netherlands. The appropriation of Tree of Jesse iconography in this panel serves not only as a reminder of the extended genealogy of Saint Anne, but also invokes the prophecy of Isaiah, reinforcing the authority of the whole iconographical programme of the wings.

The neighbouring panel moves on to the main subject of the altar, Saint Anne and her association with the Carmelites. Anne is depicted as a young girl being introduced to the Carmelites on Mount Carmel by her parents, Emerentiana and Stollanus, while a small vignette in the background depicts her birth. The two lower panels continue the story, with the engagement of Anne and Joachim and then the marriage itself.40 The Marriage of Anne and Joachim takes place in front of a temple portal in the presence of her parents and seems to deliberately reference traditional Marriage of the Virgin iconography. As with the representation of Hismeria, the couple are dressed in rich and elaborate robes, which would resonate with an audience of patricians and wealthy merchants. In addition, Anne wears a crown, which is presumably intended to infer that she, like the Virgin, is descended from King David. This depiction of Saint Anne as a royal ancestor of Christ is relatively unusual, and is a further example of how the Carmelites were prepared to manipulate standard iconography for their own purposes.

The sequence continues on the inner right wing with four scenes from the married life of Anne and Joachim, which Ashley and Sheingorn have suggested may have served as an exemplary model of marriage for the members of the brotherhood.41 Sev eral well-known episodes from the life of Saint Anne are missing, such as the Rejection of Joachim’s Offering, the Annunciation to Anne and Joachim and the Meeting at the Golden Gate. It may be that these scenes were either incorporated in the lost central shrine, or not considered of particular relevance to the iconographic programme of this work, which is fundamentally concerned with promoting the Carmelites and their personal relationship with a saint on whom they had bestowed great power.

The outer wings of the altar illustrate Anne’s appearance in visions and the representation of various miracles. On the exterior of the left wing, the first panel refers to a miracle of Eliseus (Elisha), thought to have been one of the original founders of the Carmelite Order.42 The following depicts Saint Anne among the Carmelites with her children and grandchildren, where the Holy Kinship appears once again in the background, portrayed as an altarpiece that has come to life. Beneath these, the first panel tells the story of the hermit Procopius and how, because of him, Saint Anne came to the aid of the queen of Bohemia during childbirth.43 The following features the vision of Saint Bridget; Saint Anne appears in the sky in the top right corner of the panel, while Saint Bridget can be seen writing her Sermo angelicus, which is being dictated to her by an angel.44 These sermons, which are devoted to the Virgin, contain the daily readings for Matins and became an essential part of the Birgittine nuns’ liturgy. The blessing for the second lesson on Wednesday refers to Isaiah’s prophecy, stating

This Virgin also is the rod which Isaias foretold would come out of the root of Jesse, prophesying that a flower would spring out of it, upon which the Spirit of God would rest. O ineffable rod! The while it grew within Anne’s womb, the pith thereof abode even more gloriously in heaven.45

The exterior of the right wing starts with the vision of the prophet Elijah. According to Carmelite tradition, Elijah’s vision of a cloud that produced rain, thereby ending a major drought and restoring the fruitfulness of the earth, was seen as a metaphor for the Virgin.46 In this interpretation, however, we seem to have a conflation of Elijah’s vision with that of the hermits on Mount Carmel. Elijah is depicted kneeling before an apparition of Saint Anne, who is seen hovering above the sea in a position of prayer. Above her is the Virgin, floating in a light filled cloud surrounded by four angels; she is shown holding the stem of a blossom that supports the Christ Child. This image can also be interpreted as a subtle reference to the Tree of Jesse: Christ is the beautiful flower of the Carmelite vision and the flos of Isaiah’s prophecy. In this way the conflation of Elijah’s vision with that of the hermits is imbued with the inherent authority of well-established iconography.47 Like much of the other plant imagery in this work, the lily of the valley growing from the rock in the foreground has obvious Marian connotations.

The following panel features a vision of Saint Anne on an altar, with the figure of the Virgin as a tiny infant in her womb, an image that was often used as an illustration of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin, a concept vigorously supported by the Carmelites.48 God appears at the top of the panel and the words from the Song of Solomon 4:7, ‘Tota pulchra es’ are inscribed on a scroll above his head; half figures of David with his harp and Solomon appear either side of Him. David’s speech scroll carries a verse from the Book of Psalms 9.36, ‘his/her sin shall be sought, and shall not be found’.49 The inclusion of David and Solomon featured half-length and with scrolls, again evokes a visual tradition that relates back to traditional Tree of Jesse imagery. Beneath the upper panels are scenes from the legend of Saint Colette, who experienced visions of Saint Anne.50

It seems clear therefore, that the complex iconography of the sixteen wing panels, commissioned on behalf of the Brotherhood of Saint Anne in Frankfurt, was intended primarily to honour Saint Anne as the mother of the Virgin. In addition, they communicated to the viewer the vital role played by the Carmelites in the fulfilment of Isaiah’s prophecy and may have also had a secondary and more subtle function. By highlighting their unique relationship with the female ancestors of Christ, the Carmelites were able to project a strong identity and advertise the advantages of confraternity membership. The viewer was invited to become associated with an order that Christ’s great-grandmother and grandmother had depended on, and established Tree of Jesse iconography was appropriated to help explicate and give authority to this association. Furthermore, although celibate, the Carmelites can also be seen to be actively promoting family life, reassuring current and prospective members that their spiritual needs, and those of their families, would be assiduously taken care of.

Carmelite Imagery in Other Fifteenth-Century Works Dedicated to Saint Anne

Several other works survive which employ similar iconography, yet their origins remain uncertain. Some of these have been associated with Carmelite patronage, while others appear to have a more complicated provenance. Nevertheless, they are an important source of evidence, and a contextual interpretation allows conclusions to be drawn regarding their audience and function.

The first work to be examined is a triptych, now in the Musée d’Histoire de la Médecine in the Université Paris Descartes, which provides another example of how Carmelite imagery, with its clever appropriation of the Tree of Jesse, was used to venerate Saint Anne (Figure 3.3).51 This work has been dated c.1476–85 and attributed by Max Friedländer to the Master of Saint Gudule, although both the date and attribution remain uncertain and it seems more likely, given the popularity of confraternities of Saint Anne in the 1490s, that the altarpiece was painted at a later date.52 The main subject of the work is Saint Anne and the matrilineal genealogy of Christ, and the interior of both wings feature tree imagery that is clearly derived from Tree of Jesse iconography.53 The left wing has a representation of the vision on Mount Carmel; Emerentiana is seen kneeling before four Carmelites. A tree growing from above her breast divides into two branches, whose blooms hold half-figures of Saint Anne and her sister Hismeria. Above them, on the highest branch in a rose blossom, appears the half figure of the Virgin surrounded by a mandorla. Growing from her head is a small twig, which supports an open fruit, out of which steps the naked figure of the Christ Child. Two angels in the corners hold banderols whose inscriptions have many similarities with the prophecy of Isaiah. These read: ‘Emerentia, beautiful clean virgin pure, from the offshoot of the tree that will please God, shall come forth a rose, sweet of scent, that will carry the fruit of life’ and ‘Emerentia, you shall be the root of the rose tree Anna, which will be trusted, and [of the] rose Maria, praised for her virtues, mother of the fruit Jesus, who will keep everything safe’.54

Figure 3.3 The Life and Parents of Saint Anne Triptych, Anonymous Netherlandish Master, c.1476–85

(Size: Centre panel, 113 × 83 cm) Université Paris Descartes, Musée d’Histoire de la Médecine, Paris (Photo: © KIK-IRPA, Brussels)

It has been suggested by Charles Sterling that these inscriptions are in a dialect originally spoken around Maastricht and the Lower Rhine, which could indicate that this was the original location of the altarpiece.55 However, Geert Claassens, a specialist in Middle Dutch literature, believes that there is no evidence for this supposition, as the limited amount of linguistic material makes a dialectological analysis problematic. Furthermore, from c.1450, Middle Dutch dialects were developing into a more or less common Dutch, which was showing fewer and fewer outspoken regional features. Consequently, there are no dialectic characteristics in these inscriptions that would connect the wording of the text with Maastricht, or even eastern Middle Dutch regions. Nevertheless, the fact that the inscriptions are in the vernacular rather than Latin would suggest that the altarpiece was intended to be seen by a secular audience.

The right wing features the genealogy of Hismeria, who is depicted at the base of the tree with her husband Ephriam, wrongly named here as Eliud.56 The roots of a tree are suspended above their breasts and above them in blossoms sit their descendants, Eliud and his son Eminen, on the left, and Elizabeth and John the Baptist, on the right. Crowning the tree is Eminen’s descendant, Saint Servatius. At the bottom of the wing, seen kneeling towards the central panel, is the unknown donor, whose black fur almuce indicates that he is a canon. Brandenbarg has suggested that this triptych may be connected directly with Oudewater, whom he claims was a canon of the church at Saint Gudule in Brussels.57 However, this seems unlikely, as Oudewater joined the Carmelites in 1455 in Mechelen, and as a friar in a mendicant order could not have been a canon, a position that could be held only by a secular or diocesan priest.58 As Douglas Brine has demonstrated, memorial tablets were a favoured means by which late medieval canons in the Southern Netherlands had themselves commemorated, and these sometimes took the form of triptychs, as in the memorial of Jean Thorion of Saint Omer. It is possible therefore that this work, like some of those mentioned in the previous chapter, could have served such a function.59 However, the absence of any defining text means that this can only remain a supposition. Even so, the presence of a single patron does suggest that this altarpiece was not commissioned by a confraternity.

The central panel is divided into nine scenes, presented in three rows, designed to be read from left to right, around a traditional Selbdritt image of Saint Anne with the Virgin and Christ Child at the centre. The first scene in the uppermost row shows Stollanus and Emerentiana in the countryside, with their two small daughters, Anne and her sister Hismeria. The following scene shows the Rejection of Joachim’s Offering, followed by the Meeting of Joachim and Anne at the Golden Gate, with a vignette of the Annunciation to Joachim in the background. The middle row features a young Virgin with her parents, to the left of the central image, and a depiction of Saint Anne, with her second husband, Cleophas and their daughter Mary, on the right. The first scene of the bottom row shows Mary Cleophas with her husband Alpheus and their four children; Saint Anne appears again in the middle scene, with her third husband, Salome, and their daughter, Mary Salome; the final image depicts Mary Salome with her husband, Zebedee, and their children. All the figures in the panels are shown richly dressed and, to avoid any confusion, each is identified with an inscription.

Based purely on the iconography, both Sterling and the current museum catalogue suggest that this altarpiece was commissioned for a Carmelite monastery. However, the main focus of the work is its veneration of Saint Anne, and although the genealogy of Hismeria is similar to that seen on the Frankfurt altarpiece wings, the Carmelite friars feature only in the depiction of the vision on Mount Carmel. The combination of the inscriptions in the vernacular and the rich dress of the holy figures may indicate that the altarpiece was designed to be seen by a wealthy secular audience. However, the presence of the canon donor implies that it was not commissioned by a Carmelite-administered brotherhood of Saint Anne. The main function of the work is to honour the matrilineal genealogy of Christ, and the juxtaposition of the tree of the vision on Mount Carmel with the family tree of Hismeria, on either side of scenes from the Life of Saint Anne, draws on Tree of Jesse iconography to remind the viewer of the important role played by these sacred figures in the fulfilment of Isaiah’s prophecy, and of the importance of Saint Anne’s family connections.

A small panel, known as the Virgin of the Carmelites, dated c.1500 and currently in the Museo Lázaro Galdiano in Madrid, also features the vision of the hermits on Mount Carmel (Figure 3.4). Emerentiana is depicted semi-prostrate in the act of prayer with a tree emerging from behind her back, and her girdle is arranged to give the impression of its roots. The tree has only one branch, which leads to a flower that contains a half-length image of Saint Anne holding the Virgin. A further branch leads from the chest of the Virgin to a blossom that contains the figure of the Christ Child. Witnessing this vision are three kneeling Carmelites, their monastery visible in the background. An angel, to the viewer’s left, gestures towards Saint Anne and the Virgin, explaining the vision to the friars with the words ‘hec visio ista significat’ (this vision of yours signifies). The hands of the Carmelite friar, next to the tree, are open in astonishment as he comprehends the meaning of what he is seeing.60 Once again, Emerentiana has replaced Jesse as the root of the tree that is destined to produce the virga of Carmel and the flos of Christ.61 The careful positioning of the strawberry plant, on the edge of Emerentiana’s robes, directly beneath the vision, is clearly not incidental. The iconography of the strawberry plant, with its trifoliate leaf, has often been linked to the Holy Trinity, and as a member of the rose family, also has obvious Marian connotations. Furthermore, it is depicted here in full flower, just before producing its fruit and, therefore, the association of ideas is evident.62

Although this work is rather narrow in its dimensions (99 × 52.5 cm), previous scholarship has assumed that the work was originally the middle part of a triptych, which is supported by the fact that there is some deterioration on the edges of the panel that could have occurred if the wings were removed.63 If this was the case, then the main focus of the altarpiece would have been the vision of the hermits, a particularly Carmelite image, which would suggest a Carmelite commission. However, it is also possible that this panel was a wing of a larger work, one perhaps dedicated to Saint Anne, which could give it an entirely different provenance.64 The presence of the canon donor in the Musée d’Histoire de la Médecine triptych, described earlier, suggests that representations of the vision on Mount Carmel were not restricted to Carmelite commissions. It also appears that accounts of the vision were included in non-Carmelite texts, as both Jan van Denemarken, a secular priest, and Dorlandus, a Carthusian, who wrote Lives of Saint Anne at the end of the fifteenth century, began their works with a description of the vision.65 Furthermore, some manuscripts entirely devoted to the legend of Emerentiana have been discovered, such as the Legenda sanctae Emerencianae, in a collection of Latin hagiographies from the fifteenth century, now in the Royal Library of Belgium in Brussels (Ms.4837–44, ff.145–190).66 It seems entirely possible, therefore, that the Carmelites were so successful in propagating the myth surrounding the early history of their Order that the vision on Mount Carmel, with its attendant imagery, came to be adopted as a standard feature in Saint Anne iconography, regardless of the religious affinity of the donor. This theory is further supported by the existence of some later works, several of which appear to derive from non-Carmelite sources.

Figure 3.4 The Virgin of the Carmelites, Painted Panel, Anonymous Flemish Master, c.1500

(Size: 99 × 52.5 cm) © Museo Lázaro Galdiano, Madrid

Carmelite Imagery in Sixteenth-Century Works Dedicated to Saint Anne

Figure 3.5

Two Wings From a Kinship of Saint Anne Polyptych, Attributed to a Follower of Bernard van Orley, c.1528

(Size of each wing: 139 × 70.5 cm) © Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels (Photo: J. Geleyns—Art Photography)

Commissions for sixteenth-century works that include the vision on Mount Carmel alongside episodes from the life of Saint Anne appear on the whole to have been placed with Brussels artists. While this may be an accident of survival, it could also be seen as an attempt by some patrons to counter Reformation ideas, which were increasingly finding support in the city.67 The first example to be considered is found on the dismembered wings of a polyptych dedicated to the Kinship of Saint Anne, now in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, and attributed to a follower of Bernard van Orley (Figure 3.5).68 The reverse of the left wing features the vision on Mount Carmel; Emerentiana is depicted in a rocky landscape on her knees in prayer, surrounded by a group of Carmelite friars; in the upper part of the panel, three more friars can be seen looking in astonishment at an angel in sky above them. The angel gestures towards a miraculous blossom that seems to emerge from an ordinary tree; in this blossom stands the naked figure of the Christ Child, holding a globe and surrounded by a mandorla. To the left of the panel in the background, beyond a stream, we can see the house and church of the Carmelites. The reverse of the right wing, which is inscribed with the date 1528, features the subsequent Marriage of Emerentiana and Stollanus, in which Emerentiana can be seen wearing a crown to indicate her royal descent. The front of the left wing features the Rejection of Joachim’s Offering, with small scenes in the background depicting the Annunciation to Joachim and the Meeting at the Golden Gate. The right wing depicts the Birth of the Virgin and a small vignette features the Presentation of the Virgin.

The wings were purchased in 1859 from the Sablon church of Notre-Dame in Brussels; however, as the church was closed by the Calvinists in 1581 and worship did not resume until 1803, it seems unlikely that this was the original location of the altar-piece.69 Yvette Bruijnen has suggested that the wings might have originally come from the Convent of the Great Carmelites in Brussels, which was closed during the French Revolution in 1796, although lack of documentary evidence means this can only be speculation.70 The missing central panel in all likelihood featured either a Selbdritt or Holy Kinship image and, therefore, it is also conceivable that the work was commissioned by a confraternity or donor with a special devotion to Saint Anne, who may have been unconnected to the Carmelites.

A second altarpiece dedicated to the legend of Saint Anne, also in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, attributed to Jan van Coninxloo and dated 1546, provides more convincing circumstantial evidence that this iconography could be used for non-Carmelite commissions.71 When open, the central panel of the altarpiece portrays the Holy Kinship in a garden, with small scenes in the background illustrating scenes from the life of Saint Anne. The interior of the left wing features the Rejection of Joachim’s Offering; in the background is a depiction of the vision on Mount Carmel. Other background scenes illustrate the Birth of Saint Anne followed by the Marriage of Anne and Joachim, where, once again, Saint Anne wears a crown to indicate her Davidic descent. The interior of the right wing depicts the Death of Saint Anne and, through the windows can be seen two further scenes: Saint Anne in the desert and her funeral procession.

The iconographic programme of this altarpiece is similar to several of the works previously described. What makes it unusual, however, is the subject matter on the exterior of the wings (Figure 3.6). When the altarpiece is closed, Saint Anne can be seen holding the Virgin and Child before a kneeling nun, who is holding a scroll which carries the prayer ‘SANTA MATER ANNA ORA PRO ME’ (Holy Mother Anne Pray For Me). The nun is being presented to the holy group by Saint Anthony.72 As Saint Anthony was one of the major desert hermits, he was important to the Carmelites, yet the nun does not wear the Carmelite habit of a white mantel over a brown or smoke coloured tunic (depending on the dye), and it is likely that she belonged to another religious community. Prior to 1794, when the altarpiece was seized by the French, this triptych was in the l’eglise des Bogards in Brussels, the church of the Cordeliers, which is a branch of the Franciscans.73 If the church of the Cordeliers was the original location of the work, the nun could have belonged to the Franciscan Order of the Poor Clares of Saint Colette, who wore a black cloak over a grey tunic and had a special devotion to Saint Anne. Alternatively, it has been suggested that the nun is wearing the habit of the Benedictines, and that the altarpiece may have originally been commissioned for a Benedictine convent.

Figure 3.6 Legend of Saint Anne Triptych, Exterior Wings, Attributed to Jan van Coninxloo II, 1546

(Size of each wing: 114.5 × 74 cm) Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels (Photo: © KIK-IRPA, Brussels)

Several scholars have associated Jan van Coninxloo II with the Benedictine convent of Groot-Bijgaarden in Vorst, now a suburb of Brussels.74 Surviving double wing panels from a polyptych, originally thought to have come from this convent but now in the parish church of Saint Denis, could also be connected with this artist in some way.75 When fully closed, the wings depict the Virgin and Child with Anne and Joachim in a semi-interior space.76 The first opening shows scenes from the life of the Virgin, and the second and final opening, which would have originally flanked the lost central shrine, has the vision on Mount Carmel on the left (Figure 3.7), with the families of the Virgin’s sisters, Mary Cleophas and Mary Salome, in a meadow on the right.

The portrayal of the vision depicts two events shown simultaneously: in the background, four Carmelite friars greet Emerentiana in front of a church, while, in the foreground, she is asleep in a rocky landscape with five Carmelite friars kneeling in prayer behind her. Emerentiana’s head is resting on her right hand, and from her breast grows a tree, a composition reminiscent of contemporaneous representations of a seated Jesse that are discussed further in Chapter Six. This tree has only a single branch, which blossoms into a large red flower that supports a naked Christ Child in a mandorla.77 The frame is stamped with the Brussels mark and dated 1552, and on the first opening of the wings, a glass pane in the window of the Annunciation scene, contains the coat of arms of Margareta Liederkerke, abbess of Vorst.78 It is probable,

Figure 3.7 Saint Anne Polyptych, Interior Wing, Anonymous Netherlandish Master, c.1552

(Size of wing: 166 × 84 cm) Church of Saint Denis, Vorst (Photo: © KIK-IRPA, Brussels)

therefore, that the altarpiece was commissioned for the high altar of the Benedictine abbey church, either by Margareta I van Liederkerke, abbess from 1500 to 1541, or by her niece and successor, Margareta II van Liederkerke, abbess from 1541 to 1560, and that the polyptych was moved to the parish church in 1795, the first year it was not mentioned in the abbey inventory.79 The missing central panel, or carved shrine, could have featured a representation of Saint Anne with the Virgin and Child, or even a Tree of Saint Anne, which would have completed the iconographical programme of the polyptych.

The fact that an altarpiece intended for a Benedictine altar also included Carmelite imagery may not be particularly surprising, given the previously discussed association between the prior of the Frankfurt Carmelite monastery, Rumold von Laupach, and Johannes Trithemius, the abbot of the Benedictine monastery at Sponheim. Other examples where Carmelite imagery has been used in a Benedictine context can also be found, for instance, in a woodcut affixed into a Latin missal from the Benedictine Abbey of Gembloux, c.1535, now in the Royal Library of Belgium in Brussels, Ms.5237, fol.8v (Figure 3.8).80 Even though it is the Carmelite vision that is depicted, there is a view of Gembloux Abbey with its distinctive belfry in the background, although it is possible that this could have been added at a later date. Similarities between the woodcut and the Vorst panel are obvious and, given the relatively short distance between the two locations, there may be a connection.

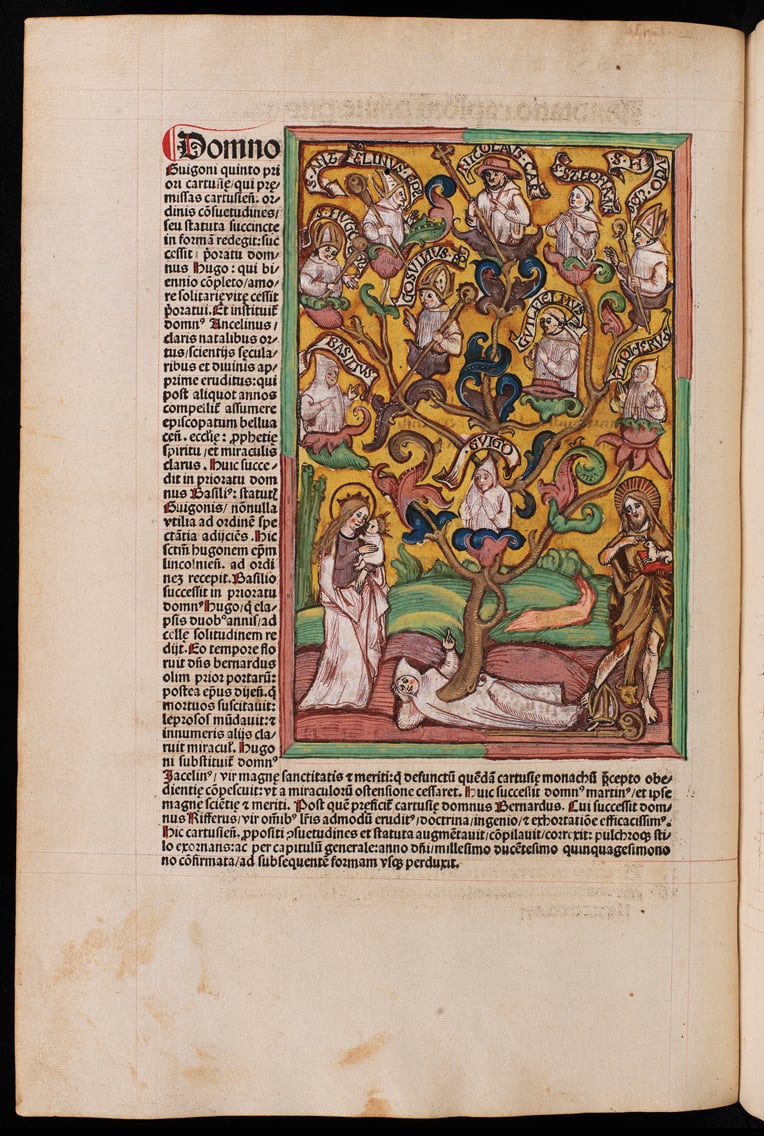

It seems apparent that Benedictine patrons were unperturbed by the appearance of Carmelite imagery in their own works of devotion, adopting the legend of the vision on Mount Carmel as part of the wider story of the life of Saint Anne. Other orders have also adopted this imagery, and it can be found on the wings of a spectacular altar-piece commissioned in 1521 by Ruttger Schipmann, prior of the Franciscan church in Dortmund. Now in the protestant Petrikirche, this retable is commonly known as the Goldene Wunder, because of its gilded central shrine that contains a detailed story of the Passion.81 The painted double wings are attributed to Adrian van Overbeck and, closed, depict a large representation of the Mass featuring the pope and emperor, developed from the established iconography of the Mass of Saint Gregory. However, it is with the first opening that we become fully aware of the complexity of the altar’s iconographical programme (Figure 3.9). A series of thirty-two individual panels tell the Holy Story, combining scenes from the apocrypha and the Bible. Beginning in the lower left and ending in the upper right, the painted panels are arranged over four rows, with eight panels in each row. The lower row is dedicated to the Legend of Emerentiana; the fourth panel depicts her visit to the hermits on Mount Carmel and the fifth features the Vision.82

To summarise, it seems apparent that images played a key role in establishing and communicating the Carmelite story. The analysis of the iconographic programme of sixteen wing panels, commissioned on behalf of the Brotherhood of Saint Anne in Frankfurt, demonstrates how clever appropriation of Tree of Jesse imagery was used to convey the Carmelites’ unique relationship with the matrilineal genealogy of Christ. While the Tree of Hismeria, on the interior of the left wing, is an obvious allusion to the Tree of Jesse motif, the conflation of Elijah’s vision with that of the hermits on Mount Carmel is a far more subtle referencing. In this way, the invocation of well established iconography reinforced the myths surrounding the Order’s foundation and provided a sense of authority. This helped the Carmelites construct a strong

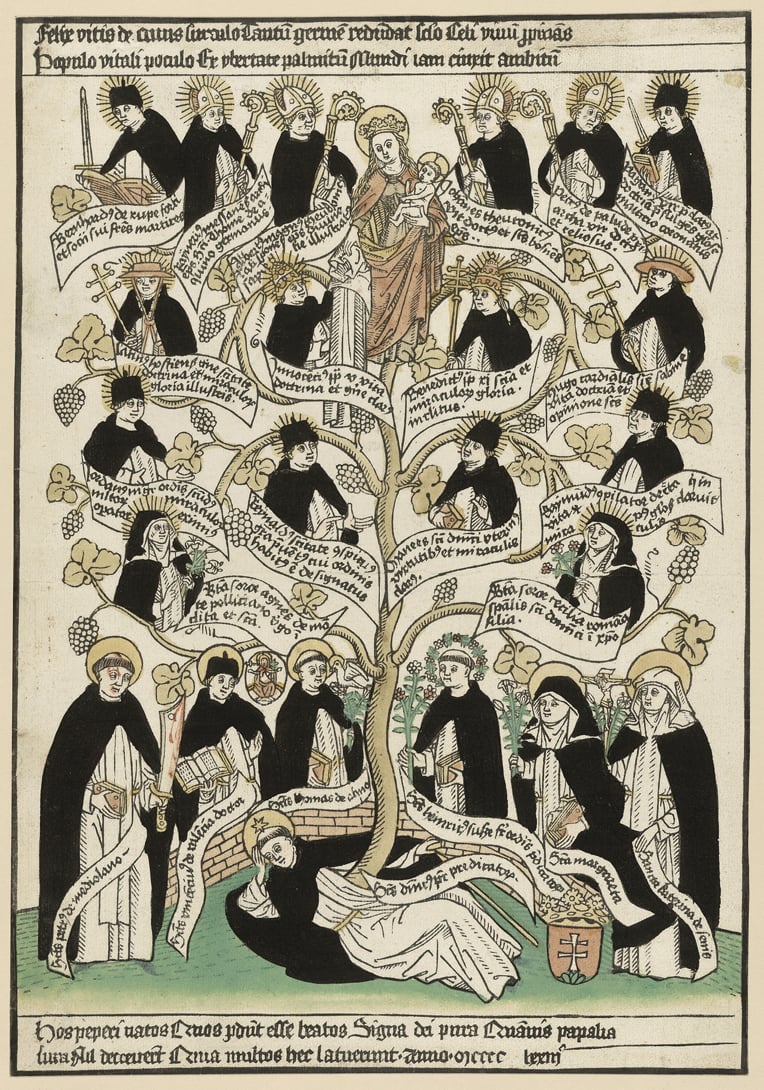

Figure 3.8 Vision of the Carmelites, Woodcut From a Latin Missal, From the Benedictine Abbey of Gembloux, c.1535

Royal Library of Belgium, Ms.5237, fol. 8v

identity, one based on an ancient and distinguished heritage. The altarpiece may have also had a secondary function, which was to advertise the advantages of confraternity membership. Members of the brotherhood came from both patrician families and a wealthy merchant class, and the use of rich and elaborate dress for the holy figures may have been a deliberate attempt to connect with this elite social group.

Figure 3.9 The Goldene Wunder Altarpiece, First Opening of Wings, Attributed to Adrian van Overbeck, c.1521

(Size Open: 565 × 749 cm) Saint Petrikirche, Dortmund (Photo: Rüdiger Glahs)

Although their context remains uncertain, there are other works that incorporate this type of Carmelite imagery, and it has been widely assumed that they must also have been commissioned on behalf of Carmelite churches. However, an examination of these works has indicated that their provenance may be less obvious. The account of the vision on Mount Carmel was not restricted to Carmelite texts, and it seems that other religious groups adopted the Carmelites’ very specific imagery as part of the wider story of the life of Saint Anne. Support for this theory is provided by several works that incorporate the vision on Mount Carmel yet were evidently linked to non-Carmelite houses. The function of the appropriated Tree of Jesse motif in these works is rather different to those featured in works commissioned on behalf of the Carmelites. The Carmelites were not the only religious organisation to appropriate Tree of Jesse iconography, and the second part of this chapter will consider how the subject was employed by some of the other orders, particularly the Dominicans.