A tree constitutes the single most powerful and most often used image of evolutionary history. Unlike the easily traceable Aristotelian ladder or scale of life, the origins of the biological tree of life imagery present a much more tangled but nonetheless traceable history. Evolutionary tree of life imagery constitutes an amalgam of male descent traceable from at least the Roman Republic with combined Roman religious and political acanthus-laden, tree-like imagery borrowed from the Greeks that appeared in temples recording birth-death-rebirth within cyclical nature. Early Christians adopted the acanthus/tree motif almost wholesale, with increasing dollops of Christian symbols added over time. Some truly phantasmagorical Christian tree designs and mystical images appeared. Within this framework emerged a hybrid of religious trees and familial trees using the ancient ideas of tracing familial descent within the context of a tree-like ascent.

Roman Obsession with Ancestors and Reverence for Nature

Ancient Romans at once feared and venerated their dead. After cremation, internment took place outside the city walls, except in the case of a few lucky emperors. Yet any Romans who could afford to do so prominently displayed wax masks (imagines) of their ancestors in the atria of their houses along with a stemma centered on the lineal descent of the male heirs of the household. The word “stemma” borrows from the Greek word for “wreath,” and in the plural form “stemmata” means “wreaths or garlands of honor” but also refers to pedigrees and lineages. Italians still call their family coat of arms their stemma, but whereas some sculptural representations of ancestral masks exist (for example, a statue of a patrician holding lifelike imagines of his grandfather and father [Museo del Centrale Montemartini, first century b.C.E.]), no stemmata survive.

A number of ancient Roman sources describe both the masks and the stemmata. For example, in the first century C.E., Pliny the Elder (1952) writes, “In the halls of our ancestors…wax models of faces were set out each on a separate side-board…to be carried in procession at a funeral in the clan…pedigrees too were traced in a spread of lines running near the several painted portraits” (book 35.6). Seneca (1935) noted around the same time, “Those who display ancestral busts in their halls, and place in the entrance of their houses the names of their family, arranged in a long row and entwined in the multiple ramifications of a genealogical tree—are these not notable rather than noble?” (book 3.28.2).

Stemmata probably resembled later forms in which wavy lines or ribbons connected names or portraits of forebears, often in medallions starting at the top with the common ancestor, sometimes expanded to show filial relationships, women in the family, or even adoptions (Klapisch-Zuber 1991, 2000). Maurizio Bettini (1991) emphasizes that these stemmata never showed tree-like genealogies, notably because they were read from top to bottom, not upward as in a tree, but on occasion references to ramusculi (branchlets) of the stemmata occur for various individuals, a feature that later became important for jurists in describing kinship (Klapisch-Zuber 1991).

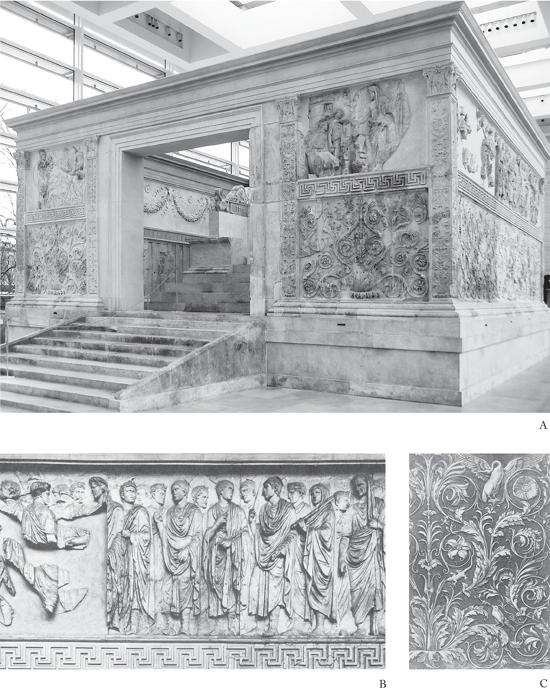

Although the Roman dead were mostly placed outside the city walls, the city streets were lined, arched, and diverted by great heroic monuments as well as all manner of political and religious edifices. In ancient Rome, politics and religion formed an inseparable bond, even as they lamentably do today in many parts of the world. A small, now lesser known but in its day very powerful politico-religious structure arose during the reign of Augustus Caesar on the Campus Martius (Field of Mars), halfway between the still splendid Pantheon (rebuilt by Hadrian in 126 C.E.) and the now derelict mausoleum or tumulus of Augustus Caesar. This structure, the Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Augustan Peace), consecrated in 9 B.C.E., celebrated the emperor’s triumphs.

The Ara Pacis provided the stuff for ancient Roman texts both in Rome and around the empire. The Res gestae Divi Augusti (Acts of Divine Augustus) engraved by the Galatians on the walls of the temple of Augustus in what is modern-day Ankara, Turkey, references the Ara Pacis: “[T]he senate resolved that an altar of the Augustan Peace should be consecrated next to the Campus Martius in honor of my return” (Velleius Paterculus 1924:12). The historian Dio Cassius (1917:54.25, 3) wrote about discussions as to whether the altar should be built in the Curia (Senate house); Ovid (1931:1.709) made reference to the Ara Pacis in several works, for example, Fasti (The Festivals); and the altar is depicted on the reverse side of ancient coins such as one with Nero and another with Domitian on the obverse side (for other sources, see Rossini 2008). Another, less certain image of the Ara Pacis forms part of the rectangular center of a possibly early-fourth-century hanging mosaic now housed in the Room of Masks in Rome’s Palazzo Colonna dealing with the founding of the city. In the central rectangle, the goddess Roma appears as Minerva; also present are the she wolf with Romulus and Remus, and their discoverer, the shepherd Faustulus. In the upper right of the mosaic appears an obviously rectangular structure with a pedestalled base and triangular cornices as well as a semicircle arising in the middle (for example, Safarik 2009). If any surface detail ever existed, age and wear obliterated it. This may be an early-fourth-century remembrance of the Ara Pacis, as palazzo guides indicate, or perhaps a sarcophagus.

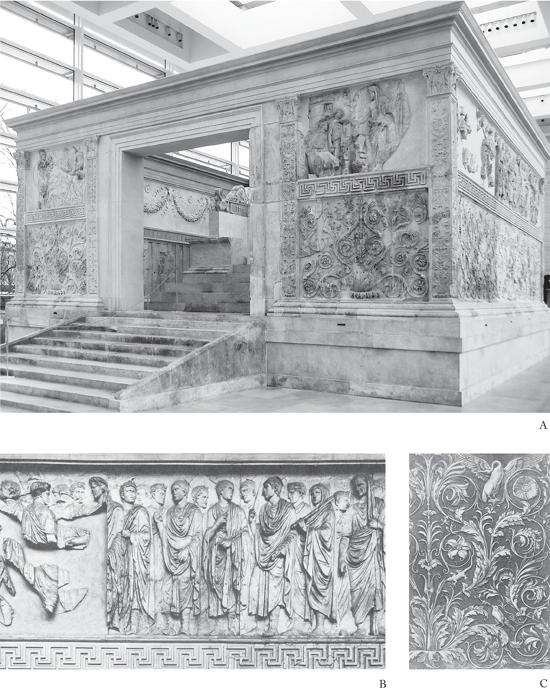

FIGURE 2.1 Ara Pacis Augustae: (A) exterior; (B) procession of members of Augustus’s family, on the exterior; and (C) photograph of an engraving of a fragment from the Ara Pacis attributed to Agostino Veneziano (ca. 1530–1535).

Fragments of the lost altar appeared in the sixteenth century and formed the basis of one or more engravings (figure 2.1C), but these fragments then once again vanished (Vickers 1975). The true rediscovery and recognition of the Ara Pacis dates from only the last part of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century. With great difficulty, many fragments were extracted from underneath existing buildings in the 1930s and relocated, reassembled, and restored near the Mausoleum of Augustus. In 1938, Mussolini had a glass-sided enclosure built around the Ara Pacis as part of his Piazza Augusto Imperatore glorifying Fascist Italy. A new enclosure dating from 2006 now protects the Ara Pacis (Crow 2006).

The exterior of the Ara Pacis appears today as a rather austere off-white marble structure (see figure 2.1A), but when first built, its bas-relief walls shown brightly with color—certainly a striking presence on the open Campus Martius even though it measures only 35 feet (10.6 m) wide by 38 feet (11.6 m) long, and 20 feet (6.3 m) high (Rossini 2008). The longer sides, both open in the middle, had faced east and west, with the west being the entrance. The most famous section of the Ara Pacis encircles the exterior upper half of the altar, showing, among others, a procession of members of Augustus’s family as well as more allegorical human and animal figures (see figure 2.1B). The lower half, sometimes referred to as the vegetal frieze, also encircles the structure. It is the largest such vegetal frieze known from ancient Greece or Rome. The exquisitely crafted, lifelike imagery suggests the work of Greek artisans (Hughes 2011).

Figure 2.2A shows the north side of the vegetal frieze, with an enlarged section of the north frieze immediately below (see figure 2.2B). An exhibition of the vegetal frieze in the Ara Pacis Museum noted about seventy species of plants in the frieze, although Caneva (2010) now identifies ninety unique plant species. This number will likely grow with more discoveries and analysis. The common plants include bear’s breeches (Acanthus), Italian arum (Arum), lily (Lilium), date palm (Phoenix), water lily (Nymphaea), and above all asters and thistles (Carduaceae), most representing plants found in local meadows, grazing lands, and scrublands typical of the Mediterranean region.

Although sometimes treated simply as a decorative element of the Ara Pacis, the vegetal frieze clearly denotes symbolic themes. The plants form a continuous linkage with the dominant acanthus, a symbol of immortality and resurrection (Caneva 2010). According to the exhibition at the Ara Pacis Museum, the frieze evokes the idea of self-replicating clones and germination during the summer or following a drought. The profusion of thistles unfolding and blooming, possibly symbolizing the Augustan aurea aetas (golden age), suggests this. The profusion of spiraled branches, leaves, buds, and flowers but no fruiting represents the endless natural cycle of regeneration rather than an ending, known from ancient Greek as anakyklosis, an entirely pre-Christian perception resembling Lucretius’s (2006) statement from De rerum natura (On the Nature of Things), “nullam rem e nihilo gigni divinitus umquam” (1.150). This is variously translated as “Nothing from nothing ever yet was born” (Rossini 2008) or “Nothing at all was ever born by divine agency” (E. Genovese, personal communication, 2012). The conspicuous swans at the top of the frieze honor Apollo, Venus, or Augustan patron gods (see figure 2.2C). Other small animals appear throughout: scorpions, snails, lizards (see figure 2.2D), butterflies, snakes threatening nestling birds (see figure 2.2E), and frogs (see figure 2.2F).

For us today, the imagery of a tree to show genealogy or evolutionary history seems natural, but in pre-Christian Rome, top–down stemmata showed human genealogy, and the idea of evolutionary history was unimagined; for these Romans, the branching acanthus motifs represented nature’s cycle of birth-death-rebirth. With the toppling of the Roman religion by Christianity during the reign of Constantine in the early third century, Christianity began to embrace acanthus motifs in its churches, adding first simple Christian symbols and later magnificently ornate images. The vegetal friezes in Roman structures such as the Ara Pacis formed the ancestral basis for these later representations. Early Christians, however, began doing something different. Instead of showing top–down stemmata with lines of descent for the divine and other biblical personages, they arranged such figures from bottom to top, ascending to heaven superimposed on acanthus or tree-like backgrounds.

Expropriating the Acanthus Motif with Added Symbolism

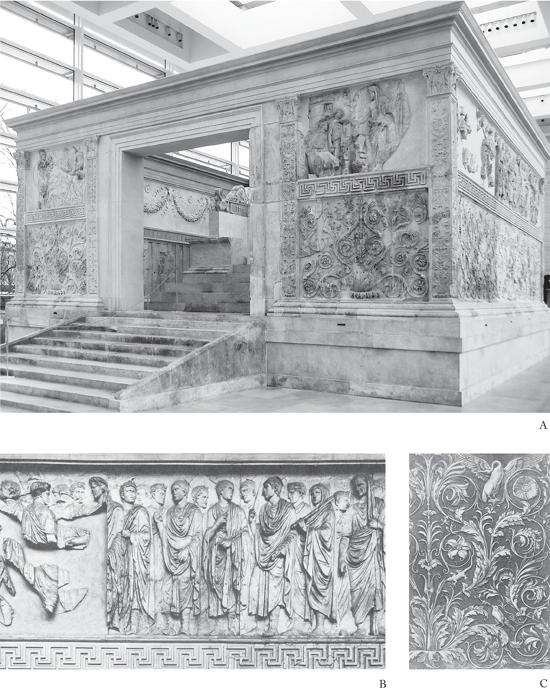

Although now rather faded and forlorn, a mosaic from the fifth century bridges the time between the Ara Pacis of the first century B.C.E. and later, much better preserved and better-known Christian acanthus motifs. This mosaic occupies the apse in the narthex, or antechamber, of the octagonal Baptistery of the Arcibasilica Papale di San Giovanni in Laterano (Papal Archbasilica of St. John Lateran), likely the oldest baptistery in Christendom (figure 2.3A and B).

The Lateran Baptistery arose from an older Roman structure, possibly a nymphaeum donated by Emperor Constantine soon after his politically expedient conversion to Christianity and arguably before the Ara Pacis faded from view and memory. As with the Ara Pacis vegetal frieze, the narthex mosaic, although incomplete, shows some fairly crude but honest restoration (see figure 2.3B). The mosaic bears relatively few clearly Christian symbols. Flowers represent only three or so different forms (see figure 2.3C). Six small crosses, barely discernible except for one reconstructed on the far right (see figure 2.3D), encircle the top of the vegetal frieze. Four small doves and a lamb crown the vegetal portion of the mosaic. No other animals occupy the mosaic. A much later Baroque cross and two cherubs jut outward from the lower center of the mosaic, partially obscuring the restored acanthus at the bottom center. The central stalk arises from the acanthus, with two intertwined vines forming four ovals, quite similar in design to such ovals in later Christian mosaics. Plants occupy at least the lower two ovals, reminiscent of the many plant species in the central stalk of the Ara Pacis vegetal frieze.

FIGURE 2.2 Ara Pacis Augustae: (A) photograph of the north side of the color-enhanced (now black and white) vegetal frieze, (B) with an enlarged section. Some animals on the exterior of the Ara Pacis include (C) a conspicuous swan, (D) a lizard (broken head), (E) a snake threatening nestling birds, and (F) a frog (missing head). (The figures of the animals were enhanced for viewing.)

FIGURE 2.3 Baptistery of the Arcibasilica Papale di San Giovanni in Laterano: (A) exterior; (B) mosaic in the apse in the narthex; and details of (C) flowers and (D) a cross.

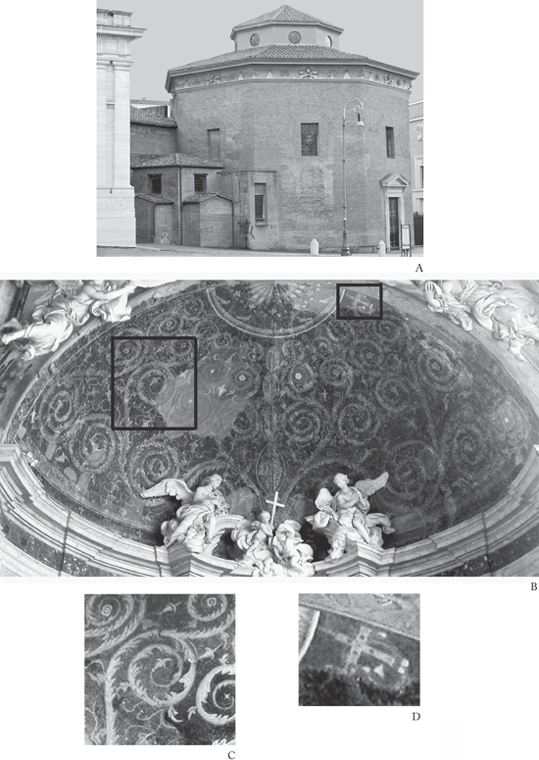

The acanthus motif reaches its most glorious excess in the small Basilica di San Clemente (Basilica of St. Clement), dedicated to the traditionally recognized fourth pope, Clement I, and one of the oldest churches in the city (figure 2.4A). The extant basilica, in what passes for one of the quieter corners of Rome but only some 985 feet (300 m) from the Colosseum, dates from probably the early twelfth century, although times for building on the site remain confused and confusing (Boyle 1989; Collegio S. Clemente and Gerardi 1992). Churches abound in Rome, but this one holds more than a few surprises. The site preserves as many as four levels, at least three of which encompass religious histories. The lowest layer includes the remnants of structures likely destroyed in the fire of 64 C.E. during the reign of Emperor Nero. Above this, parts of structures from the first century preserve areas for religious practices of early Christians as well as areas for the Mithraic religion, including the mostly enclosed sanctuary and surrounding rooms considered as areas for indoctrinating followers into that religion, named after the Persian god Mithras. As the Christian sect came to dominate, it took over this space when the Mithraic religion became illegal in 395. The third level is the first and larger Basilica di San Clemente, probably completed in the late fourth century and heavily damaged by fire during the Norman invasion in the eleventh century. The slightly smaller, existing basilica arose upon the fourth-century structure relatively soon after 1100 (Boyle 1989).

These older structures below San Clemente offer a fascinating glimpse of religion throughout Roman history, but they do not provide the most striking extant features of San Clemente. This honor belongs to the incredible twelfth- or thirteenth-century golden mosaic that covers the semicircular recessed apse behind the altar (see figure 2.4B). The inclusion of clearly third- and fourth-century motifs suggests that this may be a copy of a similar and probably larger mosaic in the earlier version of the basilica. The large crucifix in the middle of swirling curlicue plant tendrils, however, does not come from third- and fourth-century sensibilities but represents a more twelfth-century religious perception (Boyle 1989). The crucifix emerges from a clump of foliage at the bottom middle of the mosaic. The clump is an acanthus plant, which pre-Christian Greeks associated with cyclical nature and life enduring beyond the grave. This sort of motif in architectural design, known as spiraling rinceaux, refers to the later French term for this botanical form (Semes 2004), with an unmistakable resemblance to the same motifs in the Ara Pacis and Lateran Baptistery. Interestingly, the French rinceaux derives originally from the ramusculus discussed earlier, which is Latin for “small branch.”

FIGURE 2.4 Basilica di San Clemente: (A) exterior and (B) mosaic in the apse.

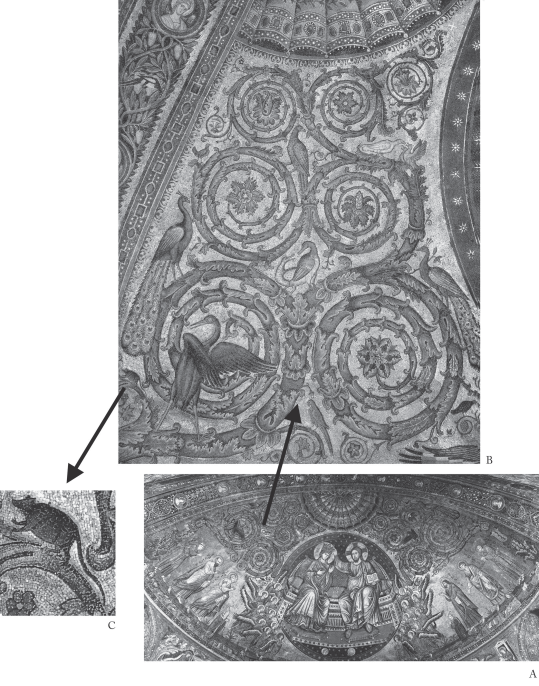

As in the Ara Pacis vegetal frieze, the San Clemente apse mosaic sends out curved acanthus tendrils of various plants from a large central acanthus. In the mosaic, the large crucifix dominates the center, whereas the Ara Pacis acanthus sprouts a large vegetative stalk from its center comprising six different plant species (Caneva 2010) (see figure 2.2A and B). Even the number, directions, and manner of joining of the spiraling vines in the mosaic and the frieze bear an uncannily striking resemblance. The apse mosaic also presents many animals as well as people: deer, peacocks, chickens, cattle, sheep, goats, dolphins, and doves, some with Christian symbolism. The alternating positions of the doves on the upright of the crucifix (see figure 2.4B) recall the vegetative stalk emerging from the acanthus in the Ara Pacis frieze.

The mosaic supposedly expresses a Byzantine influence (Gerardi 1988) in the Cosmatesque or opus Alexandrinum style. Such mosaics grace much of medieval Italy, especially in the vicinity of Rome. Cosmatesque takes its name from the Cosmati family, the thirteenth-century craftspeople who arranged ancient marble fragments into geometric inlays, including interconnected spirals. Possibly the San Clemente apse mosaic includes some Byzantine designs, but the great similarity in design and symbolism between this mosaic, the Lateran Baptistery mosaic, and the Ara Pacis vegetal frieze cannot be dismissed, although they span more than a millennium. The Christian symbols represent life and constant rebirth, but whereas the vegetal frieze shows Roman themes, some with a Hellenistic source, the apse and Baptistery mosaics place these within the context of a Christian credo. Further, all three structures are in close geographic proximity. Before Mussolini moved the Ara Pacis to its current location in the 1930s near Augustus’s tumulus, it stood little more than 1 mile (1.6 km) from San Clemente and another half-mile (0.8 km) farther on to the Lateran Baptistery.

The Ara Pacis vegetal frieze, the Lateran Baptistery narthex mosaic, and the San Clemente apse mosaic quite literally as well as metaphorically depict trees of life. The later emerging scientific use of the tree of life symbolism most directly comes from biblical references and familial genealogies, but even these derive from older traditions in Roman and Greek antiquity. We cannot say that the first-century B.C.E. Ara Pacis frieze led directly to the fifth-century c.e. Lateran Baptistery mosaic, which in turn led to the likely twelfth-century San Clemente mosaic (figure 2.5), but they resemble one another too much for mere coincidence, observations in part made separately by others (Toubert 1970; Tcherikover 1997; Caneva 2010). As we shall see, other early examples of the spiraling acanthus motif strengthen and support this conjecture. Although a Roman quip, “Se non è vero, è ben trovato” (If it’s not true, it’s still a good story), tempers the desire to accept such coincidences, I think the evidence supports the truth of the matter as to the continuity through time of these motifs.

FIGURE 2.5 Comparison of (A) mosaic in the apse of the Basilica di San Clemente, (B) mosaic in the apse of the Baptistery of the Arcibasilica Papale di San Giovanni, and (C) enlarged section of the north side of the vegetal frieze on the exterior of the Ara Pacis.

Everywhere, Swirling Acanthus

The likely relationship between the Roman vegetal frieze and the two Christian apse mosaics stands more clearly because of the ubiquity of the acanthus motif. Architecturally, acanthus plants are everywhere, from the ostentatious capitals of Corinthian columns, such as those adorning the Pantheon in Rome (figure 2.6), to the spiraling rinceaux gracing the interiors and exteriors of many structures from ancient to modern. If one looks even passingly at buildings with any classical Greek or Roman influences, the acanthus abounds. Examples, much less elaborate than in San Clemente and less integral to the design, survive in or near Rome and vary considerably in age.

The oldest example, and the only one not found in Rome, adorns the very well-preserved Maison Carrée in Nîmes, France. As with many ancient Roman buildings—most famously, the Pantheon in Rome—it survives in such good condition because of its requisition by the Catholic Church. Built around 16 B.C.E. for an uncertain purpose, the building was dedicated between 5 and 2 B.C.E. to Gaius and Lucius Caesar, the sons of the building’s designer, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, and heirs of Augustus Caesar. Above the columns supporting the building, a relief band of spiraling stems and leaves emerges from a central acanthus plant. The stems and leaves are interspersed with flowers and occasional birds (figure 2.7A).

The Terme dei Sette Sapienti (Baths of the Seven Sages) from 130 C.E. at Ostia Antica, the ancient port some 12 miles (20 km) southwest of Rome, preserves much of a circular mosaic floor 40 feet (12 m) in diameter. The circular room possibly served for some time as a market and at other times as the cold room of a bathing complex. From what can be determined from observation and various sources, two acanthus stalks arise from two quadrants 90 degrees from each other, each giving rise to spiraling acanthus (see figure 2.7B). Although some flowers are shown, a hunting scene with humans and a host of wild beasts among spiraling acanthus dominates the design. Notably, as we pass from the first-century B.C.E. Ara Pacis to the second-century c.e. Terme dei Sette Sapienti to the twelfth-century San Clemente, animals and humans become more prominent in the design as the likely meaning of the design changes.

The next younger example preserves a painted decoration from a room known as the Sala dell’Orante found in a fourth-century Roman house supposedly belonging to two men, John and Paul, who worked for Emperor Constantine. As the story goes, they suffered martyrdom, and the Basilica di Santi Giovanni e Paolo al Celio (Basilica of Sts. John and Paul on Caelian Hill) now overlies their house. A painted band in the Sala dell’Orante, although faded and less elaborate than the relief on the Maison Carrée and the mosaic at Ostia Antica, unquestionably shows the same motif of an acanthus plant, spiraling stems, and leaves (see figure 2.7C).

FIGURE 2.6 Top of a Corinthian column on the Pantheon.

A number of churches in Rome use the acanthus as a decorative motif. The oldest of these examples is almost a thousand years younger than the painted acanthus decoration in the Sala dell’Orante. These churches vary in the elaboration of both painted decoration and ornamented relief. The order of the often overlapping time intervals when most of the extant portions of these basilicas were built or repaired is Sant’Agostino (St. Augustine) in the thirteenth through fifteenth centuries (figure 2.8A), San Luigi dei Francesi (St. Louis of the French) in the sixteenth century (see figure 2.8B), and Santa Maria del Popolo (Our Lady of the People) in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries (see figure 2.8C). Just as with the older Maison Carrée ornamentation and the Sala dell’Orante decoration, all these later examples of the acanthus motif do not represent the centerpiece of any display, altar, nook, or nave but serve as embellishments that frame paintings or form wall or ceiling panels.

Santa Maria Maggiore (St. Mary Major) uses acanthus plants as a more important but still not central theme in its interior decoration. This major basilica in Rome supposedly ranges in age from about 350 C.E. to the eighteenth century. The acanthus plants in question flank each side of the main apse mosaic, which depicts the Coronation of the Virgin, created by Jacopo Torriti in the late thirteenth century. The tree-like acanthus plants flank the far left and right sides of the main panel of the mosaic, each sending forth six large, spiraling stems (figure 2.9A). The center of each spiral bears a flower, each of which appears to be distinct from the others. At least twelve smaller spirals on each side possess different flowers. In addition, eleven birds adorn the (viewer’s) left acanthus and nine embellish the right, including—among others—ducks, peacocks, cranes, and a raptor, as well as small passerines (see figure 2.9B).

FIGURE 2.7 (A) Spiraling stems and leaves emerge from a central acanthus plant at the top of the exterior of the Maison Carrée, with details of birds; (B) partial image of the mosaic floor at the Terme dei Sette Sapienti; (C) illustration of painted decoration of acanthus from a room known as the Sala dell’Orante, from Germano di San Stanislao’s La Casa Celimontana dei SS. Martiri Giovanni e Paolo (1894).

FIGURE 2.8 Scrolled acanthus motifs in Roman churches: (A) Sant’Agostino; (B) San Luigi dei Francesi; and (C) Santa Maria del Popolo.

As an aside, having worked on mammals throughout my academic career, I take special interest in the only two mammals represented in the mosaic. A rabbit sits rather boldly on a flower-like blossom on the lower-right spiral of the right acanthus. A small rodent scurries up the lowest small spiral on the left (see figure 2.9C). I cannot determine what species this might be or what, if anything, it may symbolize. A likely candidate, the black rat (Rattus rattus), reached the Roman Empire from Asia at least by the first century c.e. The long, thin tail suggests this species, but it also might represent the edible or fat dormouse (Glis glis), much favored by Romans as a snack. This species and that portrayed in the mosaic are rather chubby, but the dormouse has a fluffier tail. Notably, one of the frescos in the fourth-century home below the Basilica di Santi Giovanni e Paolo al Celio also shows a rodent more strikingly similar to the edible dormouse.

These acanthus and spiraling rinceaux motifs, arguably with the exception of those in Santa Maria Maggiore, largely represent subsidiary embellishments. Not so for the San Clemente apse mosaic, which far exceeds the ornamental and decorative acanthus motifs (see figure 2.4B). The San Clemente acanthus spirals intertwine with many layers of religious symbols and symbolism; one description intones that “the sum total is that the mosaic depicts the Tree of Life, which has withered after sin entered the world but then turns into the new Tree of Life, the Cross of Christ which is the ultimate symbol of Christ’s victory over sin” (Churches of Rome 2012). The use of acanthus in the basilica obviously continues the Greek ideas of life beyond death into the Christian notions of resurrection but on a far more elaborate scale.

The Tree and the Acanthus Are Joined

The swirling acanthus trees in San Giovanni in Laterano and San Clemente, with their Christian symbolism of the crucifix, evoke the life of Christ yet provide no literal genealogy. The crucifix dominates the form in San Clemente, whereas that in Santa Maria Maggiore celebrates the Coronation of the Virgin (see figure 2.9A). This is not so with other acanthus trees of similar vintage. In these other trees, a true blending of acanthus and genealogy occurs, albeit of biblical persons, and rather than the descending in a human lineage, they ascend to heaven—an obvious reversal of the stemma.

FIGURE 2.9 Santa Maria Maggiore: (A) mosaic in the apse; (B) a left-spiraling acanthus; and (C) detail of an unidentified rodent.

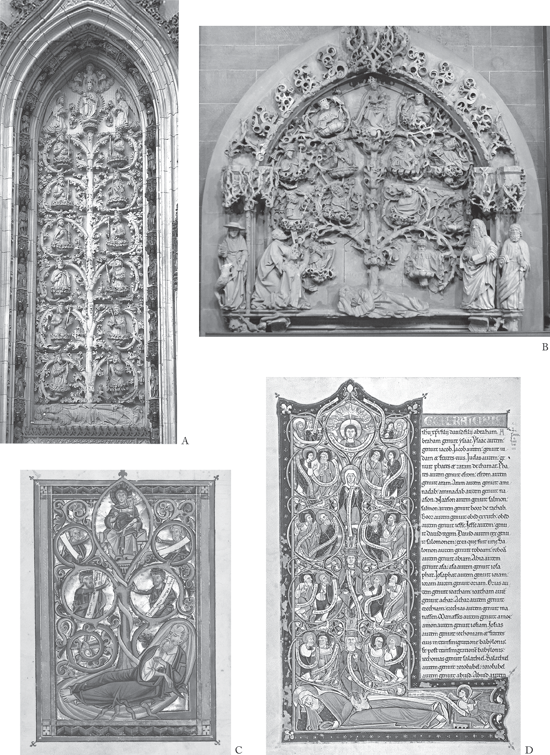

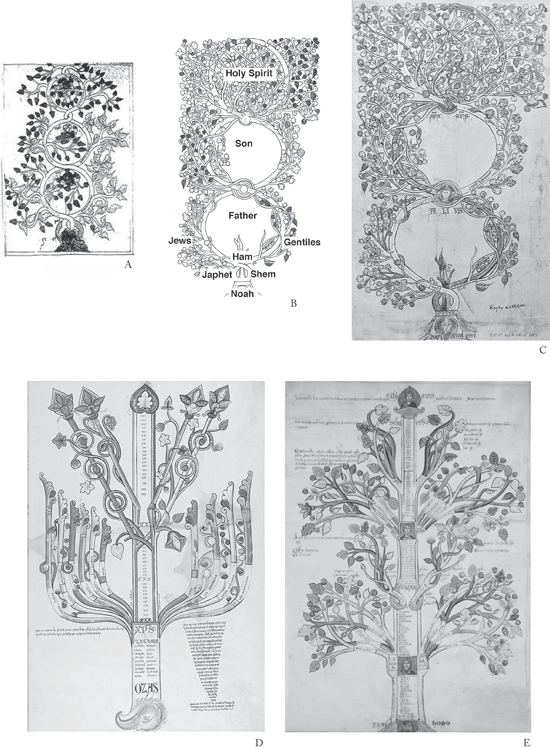

A common theme, the Tree of Jesse, such as in the beautiful window at Chartres Cathedral, most often shows Jesse as the base or root from which the tree leads through the House of David most often upward to Jesus of Nazareth. Inspiration for this image comes from the prophecy in Isaiah 11:1. The translation from Latin of the Vulgate Bible (commonly in use in the Middle Ages) reads, “A rod will come forth from the root of Jesse, and a flower shall rise up.” The Latin word for “rod,” virga, sometimes served as a pun referring to the Virgin Mary (virgo Maria in Latin), with the flower referring to Jesus. In the representations of the Tree of Jesse in churches and illuminated manuscripts, Jesse forms the root or base from which sprouts the tree ascending to the Virgin and Child. Various versions show assorted prophets and saints (figure 2.10).

In these trees, we see subdued and less subdued echoes of the acanthus motif in the Ara Pacis vegetal frieze and the Lateran Baptistery and San Clemente mosaics. One fifteenth-century carved example of the spiraling rinceaux Tree of Jesse comes from Germany. It appears on the south side of St. Lamberti in Münster. A tall portal includes a Tree of Jesse first carved in sandstone in the fifteenth century and then restored in the early twentieth century (see figure 2.10A). A splendid late Gothic carved example of the Tree of Jesse with the spiraling rinceaux ornamentation exists in the Cathedral of St. Peter in Worms, Germany. The north aisle preserves five tympana, the semicircular decorative surfaces over entryways, one a Tree of Jesse (see figure 2.10B). These tympana once surmounted the entrances of the demolished cloister associated with the cathedral from the end of the fifteenth century. Examples of the Tree of Jesse coeval with the San Clemente mosaic derive from an unknown source from Würzburg, Germany, from around 1240 to 1250 (Kren 2009) (see figure 2.10C), and the Capuchin’s Bible, from around 1180 (see figure 2.10D). Both include the flourished curlicue vines entwining the edges of each scene, but despite their unmistakably tight coils, neither of these comes close to the exuberance of the Ara Pacis frieze or the San Clemente mosaic. Such vine motifs also occur as marginal embellishments on many other illuminated manuscripts, although none with a clear tree-like meaning as in Trees of Jesse.

Examples abound, but the four shown in figure 2.10 most clearly evoke earlier Hellenistic/Roman and then Christian trees of life replete with symbolism harking back to the acanthus and its spiraling tendrils. Two elements missing or nearly so are flowers and animals, except for one dog in the St. Peter tympanum and what appears to be a dove in the Capuchin’s Bible, but they do ascend upward.

The Tree Mosaics of Otranto, the Sacred and the Profane

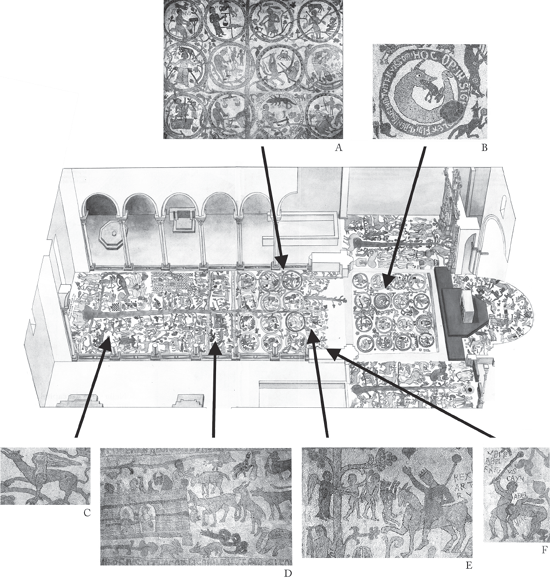

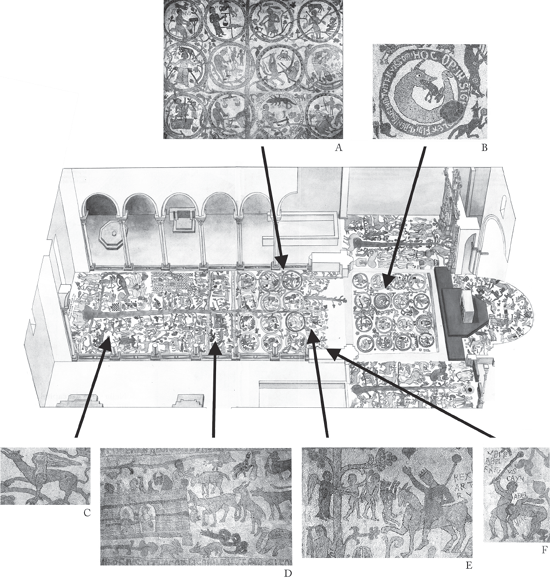

No discussion of trees of life in Christian churches would be complete without mentioning the unquestionably most grandiose of them—the 700-square-foot (65 sq. m) mosaic that covers the entire floor of the Cathedral of Otranto (Nigro 2000; Gianfreda 2008). Otranto, a small town on the Adriatic Sea, lies almost at the end of the boot heel of Italy. The cathedral was consecrated in 1088, but the mosaic floor was not laid until the latter third of the 1100s, about a hundred years before the very different apse mosaic in San Clemente. Five distinct parts define the floor mosaic: the apsidal area behind the altar, the presbytery area in front of the altar, two small trees of life (one each in the side naves), and the large tree in the central nave (figure 2.11).

FIGURE 2.10 Tree of Jesse: (A) St. Lamberti; (B) Cathedral of St. Peter; (C) unknown source from Würzburg; and (D) Capuchin’s Bible. ([C] reproduced by permission of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ms. Ludwig VIII 2, fol. 7v)

A tree motif does not define the apse floor mosaic behind the altar but shows a variety of biblical and phantasmagorical creatures. The presbytery floor in front of the altar does include a small tree at its base and sixteen circular medallions, some with clear biblical significance. The two medallions at the bottom flanking the small tree, presumably the Tree of Knowledge, show the temptation of Adam and Eve by the serpent. The medallion next to Eve shows the behemoth referred to in Job 40:15 (“Behold now behemoth, which I made with thee; he eateth grass as an ox” [King James Bible]), probably referring to a hippopotamus. The medallion just above Adam is a large, serpent-like form with a hare in his mouth; attributed to the leviathan in Job 41:1 (“Canst thou draw out leviathan with an hook?” [King James Bible]), it may refer to a crocodile (see figure 2.11B). In the upper left of the presbytery floor, medallions show the Queen of Sheba and King Solomon.

Other motifs in the presbytery may be satirical. Directly above the small tree but outside a medallion, a dog beats cymbals, symbolizing folly, and above it an ass strums a harp, symbolizing ignorance. Various phantasmagorical beasts are depicted. A siren with a split tail appears in one medallion. A centaur in another medallion fires arrows at the stag in the next medallion, with one imbedded in its chest. A griffin—sometimes mistakenly identified as a basilisk, cocktrice, or leopard—seems to be attacking a goat (another griffin is shown in figure 2.11C). A man, tentatively identified as the creator of the mosaic, kneels next to a unicorn. Real mammals include a camel, an elephant, a stag (with arrow), an antelope, a bull, and a leopard attacking a fox (representing lust and cunning, respectively).

The right nave holds the Tree of Redemption. It displays an identified biblical figure, Samuel, but also mythological creatures such as a harpy, a sphinx, a minotaur, and a lion, supposedly of Judah, biting a dragon. Names in Latin identify Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob in the left nave mosaic, which shows the final Resurrection and Judgment. Three beasts and a scapegoat guard the gates of hell, with a man bound hand and foot and a figure next to him identified as Satan.

When observed in plan view, the floor mosaic in the central nave bursts with detail. One does not know where to look first, but a few motifs stand out. A tree runs the entire length of the center of the nave, extending branches large and small. Twelve circular medallions near the top of the tree name the twelve months and show the zodiacal signs with human and animal figures performing normal seasonal tasks (see figure 2.11A). Immediately above these and to the left, two small trees tell the story of Adam and Eve, first with their fall after partaking of the Tree of Knowledge. Next, to the right, they whimsically wave good-bye while being driven from the Garden of Eden by an angel. Oddly, a labeled King Arthur intervenes between this (see figure 2.11E) and the labeled story of Cain and Abel’s sacrificing to God, here showing Cain slaying Abel (see figure 2.11F).

FIGURE 2.11 Mosaics of the Cathedral of Otranto, using a floor plan modified after Grazio Gianfreda’s Il mosaico di Otranto (2008): (A) twelve circular medallions near the top of the tree name the twelve months and show the zodiacal signs with human and animal figures performing normal seasonal tasks; (B) a large, serpent-like form with a hare in his mouth, attributed to the leviathan in Job 41:1; (C) a griffin, sometimes mistakenly identified as a basilisk, cocktrice, or leopard, appears to be attacking a goat; (D) left to right, the story of Noah and the Flood unfolds; (E) Adam and Eve (left) partake of the Tree of Knowledge and (right) whimsically wave good-bye while being driven from the Garden of Eden by an angel, but a labeled King Arthur intervenes; and (F) labeled story of Cain and Abel’s sacrificing to God, here showing Cain slaying Abel.

Immediately below the calendar medallions, reading from left to right, the story of Noah and the Flood unfolds (see figure 2.11D). On the next branches below, the eye is drawn to a checkerboard design on the left side that tells the story of the Tower of Babel. To the right, below, and diagonally across from the tower, a host of real and mythological humans, part-humans, part-animals, and animals occupy the bottom half of the mosaic. Immediately below the tower, the huntress Diana slays a stag. Slightly above and to her right, a clearly labeled figure of Alexander the Great stands before two griffins. At the very base of the expanded caudex of the tree stand two formidable elephants facing away from each other. In the mosaic immediately below and near the entrance to the church appears the name Pantaleone, the monk who supervised the work over the four years it took to complete the mosaic.

Pantaleone’s intended meaning for this eclectic floor mosaic remains obscure. It certainly presents elements found in other Christian mosaics—primarily, Hebrew Bible and New Testament stories—but Greek mythology and even elements from Asia and the Islamic world often appear. Part of this may be explained by Otranto’s proximity to these other regions. Various countries and peoples repeatedly invaded the Otranto region, and thus a cosmopolitan interpretation of the tree of life is not unexpected. The frequent inclusion of not only biblical but also more obscure texts within the mosaic seems out of place for a time when almost no one could read. In part it reads like an allegorical inside joke. Other trees in churches so far discussed do not register a clear sense of linear time. The Otranto mosaic as a whole provides an even more nonchronological narrative, although certain parts do follow a story line. Nevertheless, the tree design of the mosaic seems to be an attempt to unify many stories of the Judeo-Christian God with gods, humans, and animals, both imagined and real, from the cultures of the then known world. It is a history of sorts even if time frames and events thoroughly mingle with one another.

Cyclical Time Becomes Linear

From at least ancient Rome onward into medieval Europe, trees or other plant motifs became powerful religious symbols, many but not all opening upward toward heaven. Tree motifs in both Roman religions and Christianity used plants, especially acanthus, along with humans and a variety of real and imagined animals. In both traditions, the trees could symbolize death and renewal in nature or immortality of the soul. Cyclical themes of death and rejuvenation commonly occurred in these representations, with historically accurate representations of time of less concern, as especially seen at Otranto. Historical time versus cycles became more important parts of tree representations when a truer sense of spiritual and physical history emerged. At least two uses of history appeared at this time: one vision for the ages of man, as popularized by Joachim of Fiore, and the second employing trees to show human or even domestic animal genealogy. The ages of man framed a spiritual history for humans, whereas the human genealogical diagrams showed who begat whom.

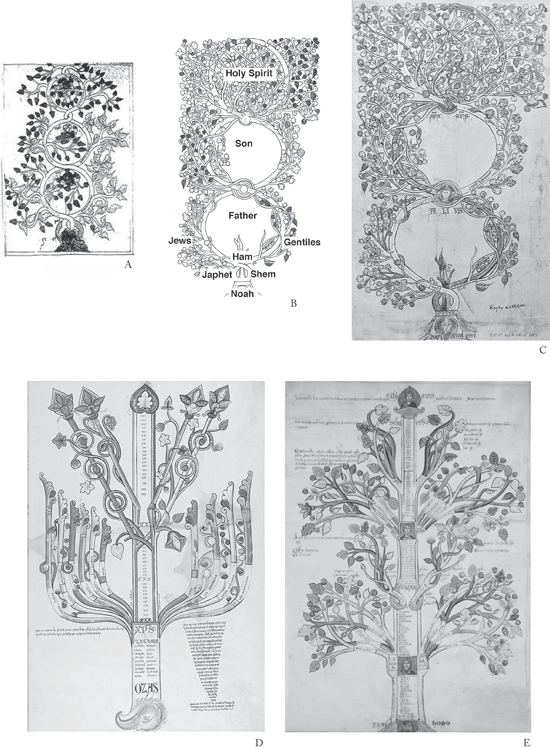

Joachim of Fiore (1135–1202), an Italian monk, mystic, and biblical scholar, produced many sorts of geometric figures—circles in circles, triangles, spirals—but is best known for tree-like figures appearing in two primary works: Liber concordie novi ac veteris Testamenti (Book of Harmony of the New and Old Testaments) and Liber figurarum (Book of Figures) (Reeves and Hirsch-Reich 1972; Reeves 1999). Through both biblical study and mystical experiences, he often elucidated in these trees what he called the three stages of time. God’s law defines the first stage. The second stage of grace comes through God’s son. The third stage, coming in the future, forms from the Spirit with the time of liberty and love awaiting the Second Coming (figure 2.12). Joachim of Fiore envisioned these three stages as the tree of life mentioned three times in the book of Revelation. Representations of these trees often show intertwining branches, each of which encircles one of the three stages, emphasizing the three stages of spiritual history (see figure 2.12A–C). German romantics and their materialist and Marxist descendants inherited this, as did the positivist philosophy of Auguste Comte (Hestmark 2000).

Joachim of Fiore’s revolutionary ideas conceived of the overlap of historical periods and change as a process of germination and fruition (Cook 1988). Notwithstanding claims that his trees express God’s purpose through the natural time span of history in biological terms (Reeves 1999), he visualized a historical framework not common for his contemporaries; thus what better than to use a tree? A new shoot generates from those that preceded it and, in turn, germinates the ones that follow in an upward trajectory.

Most of his trees possess multiple layers of meaning, not always in plain view. One motif, his Tree Eagle, when viewed upright represents a tree-like form, but when inverted, an eagle’s head reveals itself with branches for wings and tail (see figure 2.12D), supposedly a hidden symbol of the coming of his third historical age of the Spirit. Other, even more tree-like figures include trunks, branches, leaves, and buds but with the ever-present three-part spiritual history incorporated (see figure 2.12E). These trees presage and even remarkably resemble some of the biological trees of life that first appeared in the beginning of the nineteenth century, whether the budding profession of biologists attributed the cause of the change to a deity or to evolution.

FIGURE 2.12 Joachim of Fiore’s (A–C) trees with intertwining branches that emphasize the three stages of spiritual history; (D) Tree Eagle, which viewed upright represents a tree-like form, but when inverted reveals an eagle; and (E) more tree-like figure but with the ever-present three-part spiritual history incorporated.

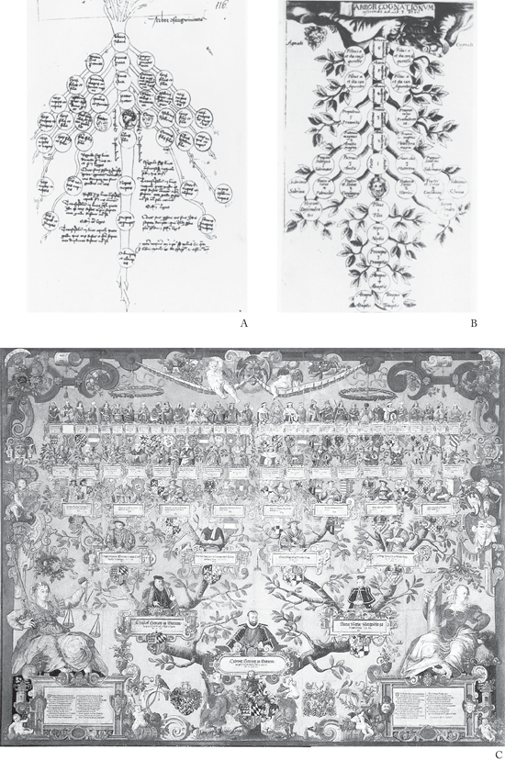

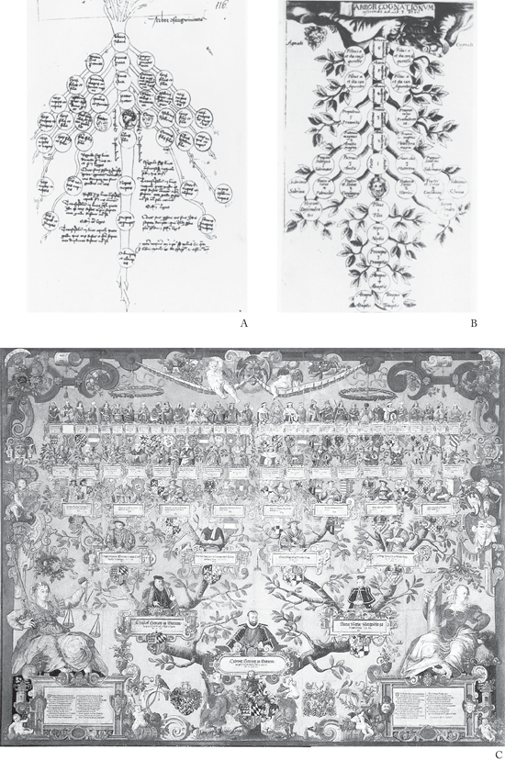

From the tenth to the fourteenth centuries, tree-like genealogies proliferated, both profane and religious, such as the Tree of Jesse described earlier. A majority of these genealogical trees carried on the tradition of showing the idea of descent—that is, from the top down. By the latter half of the sixteenth century, the more botanical tree form came into vogue (Klapisch-Zuber 1991), but, as shown earlier, this tradition had worked its way into use through other, often religious sources showing trees opening upward toward heaven. A striking aspect of these representations occurred with the reversal from a top–down to a bottom–up genealogy with the adoption of a true tree image. Schemata transformed from the idea of descent, as Christiane Klapisch-Zuber (1991) phrased it, to the idea of “an ascent and spreading-out” (112). All the old meaning from which they arise meant that genealogies read from the top down, metaphorically as a stream flows. We now generally interchange freely the words “descent” and “ascent” in genealogic or evolutionary sense, showing the diagrams opening in various directions, but this came about relatively recently, perhaps in the past two hundred years at most.

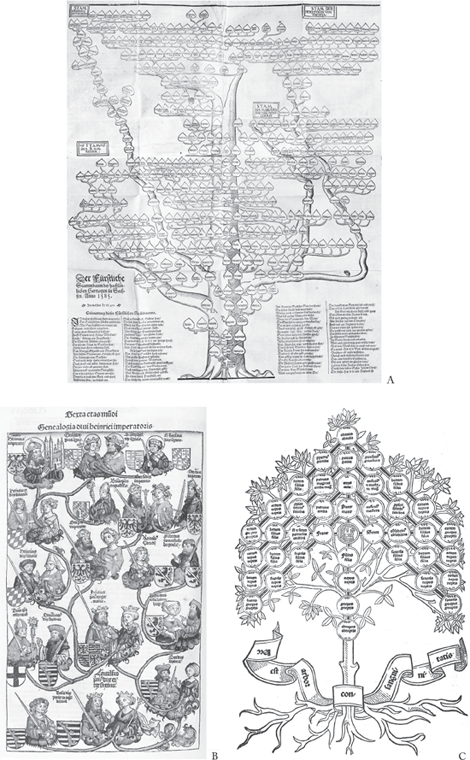

The iconography on more than one occasion bordered on the absurd. Figure 2.13A and B shows trees that open downward, with ancestral roots topsy-turvy. Figure 2.13B shows an upside-down Tree of Jesse. Even more confusion reigns when the tree finally becomes upright but the descent of one individual is shown at the base of the tree with ancestors in its upper branches. Figure 2.13C, a late-sixteenth-century family tree, at first appears to show a normal, tree-like genealogy, but look closer. The base of the tree shows Louis (Ludwig) III (1554–1593), known as Louis the Pious because of his religiosity, who served as the fifth duke of Württemberg from 1568 to 1593. Leafy branches, dangling fruit, overflowing cornucopias, and even spiraling architectural borders highly embellish this tree. The problem: the duke had no heirs, so why does he lie at the base of a family tree? The answer: the iconography is confusingly inverted. A genealogy of his ancestry or his pedigree is represented, starting with the sixth generation at the limb tips and extending down the tree, through his father, Cristoph (left), and mother, Anna Maria (right), to him at the base. Thus considerable confusion arises from using the same tree for both a pedigree and a genealogy. A pedigree shows all known ancestors of one person or a family and in older representations opens downward, whereas a genealogy shows a person’s parents, the individual offspring, and all that person’s descendants.

While visiting southern Italy in 2009, my wife and I stayed about 80 miles (130 km) north of Otranto in a masseria abandoned around World War II. Masserie are fortified farming estates in the southern coastal regions of Italy. Since Italy did not have a centralized government and armies until the nineteenth century, most masserie had to be defended against the various invaders that came ashore through the centuries. The one in which we stayed, Masseria Il Frantoio, preserves olive trees planted at least five hundred years ago. Although many of the buildings are from the nineteenth century, an underground olive press (no longer in use) may date from the sixteenth century. In the main house hangs a badly water-damaged family tree, which by appearances may date to at least the nineteenth century, if not earlier (figure 2.14A). I include it in spite of its poor condition because of its unusual form and presentation. A cartoonish, dark green-gray central stalk arises in the middle with now indiscernible dates and with side branches coming from the stalk. From the tree hang medallions with names and presumably birth dates, because the word nato (born) appears near the dates. Nato is also written on the stalk, but damage renders the dates illegible. The oldest discernible date on the lowest better-preserved medallion on the right reads 1639 or 1689. One can imagine, although not see, even older natal dates on the stalk. The most recent come from the early nineteenth century. Unlike most family trees, which show pedigrees of direct descent, the main stalk of this tree forms segments, with the medallions on side branches probably showing whole families.

FIGURE 2.13 Trees that open downward: (A) ancestral roots facing up; (B) upside-down Tree of Jesse, from Vincent Placcius’s Justiniani Instiutiones juris reconcinnatae (1682); and (C) what appears to be a family tree, but is actually a pedigree of Louis III, fifth duke of Württemberg. ([A] reproduced by permission of Innsbruck, Universitätsbibliothek)

FIGURE 2.14 (A) Badly water-damaged Italian family tree; (B) “Genealogical Tree of the Queen [Victoria] and Her Descendants.”

A much more sophisticated (probably early-twentieth-century) version of a tree with medallions records the “Genealogical Tree of the Queen [Victoria] and Her Descendants” (see figure 2.14B). Unlike the Italian version, this one portrays Prince Albert, Her Majesty, their offspring, and in turn their offspring. This otherwise rather normal family tree represents the earlier generation at the base and later generations closer to the tips, much as we see with late-nineteenth- and twentieth-century representations of evolutionary history.

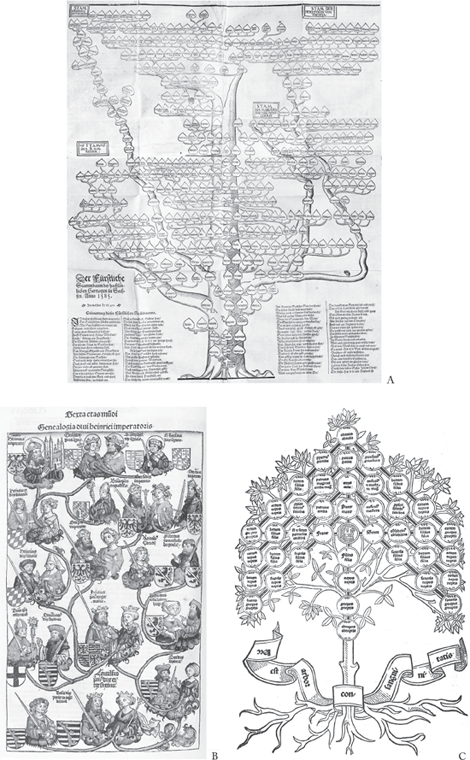

A particularly engaging tree-like representation comes from Lorenz Faust’s quirky work Anatomia statuae Danielis (Anatomy of Daniel’s Statue, 1585). He shows genealogical relationships not only as trees but also on the armored physique of a knight and another on the palm of a hand (Rosenberg and Grafton 2010). The tree shown in figure 2.15A traces the history of Saxon rulers. The tree evokes a rather massive presence as of a spreading oak, with each of the sparse larger limbs sprouting much smaller branches that march along horizontally in a Germanic fashion, budding off small heart-shaped leaves at regular intervals. Each leaf presents the name of a Saxon ancestor. As discussed in chapter 3, the tree first used to show botanical relationships in the earliest nineteenth century, although not evolutionary, employed the same motif—a tree with leaves but with the name of plant species rather than that of a Saxon ruler in each leaf.

Certainly one of the greatest uses of trees for biblical, royal, and pontifical lineages was that of Hartmann Schedel in Nuremberg Chronicle (1493). This monumental work provides many drawings of cities and real and imagined people, no matter from what epoch, dressed in medieval garb. Schedel is probably best known for his phantasmagorical monsters harking from the then unknown East—a dog-headed man, a one-eyed individual, a headless figure with his face in his chest, a one-legged man with an enormous foot with which he shades himself, a figure with elephantine ears extending below his hips, a figure with a long S-shaped neck with a beak in lieu of a mouth—in all fourteen such figures.

Many genealogies adorn the work. I lost count at about 150 for the number of what Schedel (1493; Schmauch 1941; Rosenberg and Grafton 2010) variously called lineages and genealogies of real and imagined personages. The most elaborate are those termed genealogies, showing vining tendrils extending from one couple to another. A visually interesting example traces the ancestry of Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor (972–1024) (see figure 2.15B). Regally adorned and holding a cathedral, the sainted Henry occupies the upper-left-hand corner. The genealogy starts in the bottom middle with Liudolf, the first duke and king of Saxony, and his unnamed wife. Presumably alluding to the woman giving birth, each vine emanates from the belly of the mother. In a bit of stylistic irony, the male figure below Henry II is his father, Henry II the Quarrelsome, grasping the vine that gives rise to his son and future emperor. This touch occurs in other genealogies.

Not all early trees represented specific religious or familial genealogies. One such curious tree appears in Isidore of Seville’s amazing Etymologiae: De summo bono. Illustrated manuscript versions of this work dating from around his lifetime as well as incunabular printed versions from the late fifteenth century survive (Isidore 1483). Isidore (ca. 560–636) served as the archbishop of Seville until his death. He converted the Visigoths from one form of Christianity (Arianiam) to Catholicism but was not strictly sectarian in his approach to his flock. In his work, he integrated older Greek and Roman ideas with those of the barbarians into his views of Christianity and the world. He attempted the large task of writing an encyclopedia of all knowledge of the then presumed inhabited world. Although hardly cartographically instructive, he produced a now famous small circular pie diagram showing Asia, Africa, and Europe as slices.

FIGURE 2.15 (A) Tree tracing the history of Saxon rulers, from Lorenz Faust’s Anatomia statuae Danielis (1585); (B) tree tracing the ancestry of Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor, from Hartmann Schedel’s Registrum huius operis libri cronicarum (1493); (C) “Tree of Shared Blood,” from Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae (1483).

Somewhat stylized but otherwise naturalistic, the roots, trunk, branches, and leaves of the tree in the Etymologiae form the underlayer in the diagram (see figure 2.15C). Upon this, superimposed circular medallions align along a series of connected thick, black lines. These lines do not follow the growth pattern of the tree but are upside down like the stemmata and trees noted earlier, yet the metaphor of a tree-like form is clear. The Latin “hec est arbor con-sangui-ni-tatis” on the ribbon above the roots means “this is the tree of shared blood”—that is, a family tree. The text in the pages preceding and following the tree figure (Isidore 2011:206–19) makes it clear that the tree does not show the ancestry of Isidore.

Isidore (2011) writes, “The family tree that legal advisers draw up concerning lineage is called a stemma [pedigree or family tree] where the degrees of relationship are spelled out—as, for example, ‘this one is the son, this one is the father, this one the grandfather, this one the relative on the father’s side,’ and all the rest. Here are the figures for these relationships” (210). Although a bearded man (Isidore?) is depicted in a medallion in the middle of the tree, no names of relatives appear in the surrounding medallions. Rather, the medallion immediately above the bearded man reads “father mother,” and ascending from there are “grandfather grandmother,” “great-grandfather great-grandmother,” and finally, at the very top, “great-great-grandfather great-great-grandmother.” Immediately below, trailing down the trunk of the tree, are “son daughter,” “grandson granddaughter,” “great-grandson great-granddaughter,” and finally, at the bottom, “great-great-grandson great-great-granddaughter.” To the right of the medallion of the man we find “brother” and to the left “sister” medallions. Emanating from these, medallions display various familial names such as cousin, aunt, and uncle with a host of modifiers (brother’s nephew, their daughter, great uncle, and so on). For Isidore, as with many ancient scholars, understanding original meanings of words was very important because such understanding yielded direct knowledge of nature. These words, which were more than arbitrary labels, instead embody the essence of the thing itself (Arnar 1990). What better way to represent this than as a tree, even if the metaphor seems upside down? Almost 1,500 years later in biological trees, the names of specific species, families, and orders came to represent members in God’s creation and then, shortly thereafter, the evolutionary history of life.

The Sacred, Profane, and Biological Meet

With the influence of Joachim de Fiore’s trees showing human history in a Judeo-Christian tradition, Isidore’s even earlier tree showing the etymological origins of familial relationships, and the emergence of family genealogies figured as trees, inevitably someone would suggest that nature also be presented literally as a tree and not simply metaphorically, as the ancient Romans did in the Ara Pacis. We do not know with certainty when and how this iconography first represented the history of a life as a tree in diagrammatic form, but the German naturalist Peter Simon Pallas (1741–1811), who worked in Russia, envisioned such a diagram.

Pallas described a systematic arrangement of all organisms in the image of a tree in Elenchus zoophytorum (1766):

But the system of organic bodies is best of all represented by an image of a tree which immediately from the root would lead forth out of the most simple plants and animals a double, variously contiguous animal and vegetable trunk; the first of which would proceed from mollusks to fishes, with a large side branch of insects sent out between these, hence to amphibians and at the farthest tip it would sustain the quadrupeds, but below the quadrupeds it would put forth birds as an equally large side branch. (23–24; Archibald 2009)

We must show caution in interpretation. Whereas today we see evolutionary history in such trees, almost certainly Pallas did not intend this. He was more clearly indicating plants’ and animals’ relative position one to another, as done in the scala naturae discussed in chapter 1, except now it is a tree. This appears very similar in intent to Isidore’s tree of familial relationships; certainly it was accepted that such relationships resulted from consanguinity, yet there almost certainly was no intent in Pallas’s musings that his tree of relationships was a result of common descent.

In 1801, thirty-five years after Pallas’s suggestion, an obscure French botanist produced such a tree, a tree showing the systematic arrangement, ironically, of trees replete with leaves giving the names of tree species. The age of biological trees of life had begun, and evolutionary explanations rapidly followed, but the first half of the nineteenth century also saw other visual metaphors for nature’s order that for some time lessened the impact of tree imagery.