Anything that we cannot read is, in effect, a code that we need to break. If it is a language, we can learn it or find someone to translate the message. But what if the language itself has disappeared?

HIEROGLYPHS

• The word ‘hieroglyphs’ comes from the Greek language and means ‘sacred carvings’.

• They were cut into the stone of significant buildings, such as temples and tombs, or painted onto the interior walls.

• The earliest date back at least 3,000 years.

The story that Egyptian hieroglyphics tell is of a highly organized and capable civilization that collapsed and was forgotten for thousands of years. Much of what we now know about it has been learned from reading its writings on walls and papyrus, and the process of discovering how to read these is similar to the code-breaking methods that helped to shorten World War II. So, in a sense, hieroglyphics became the earliest code, even though their meaning was not originally disguised. The structures on which hieroglyphics were carved or drawn collapsed, or were buried by the desert sand, while others were defaced by Christians intent on destroying remnants of a pagan past.

Hieroglyphics are pictorial writing: brightly coloured images that are both simple and complex. Various attempts were made to read the images, but it took many years for people to realize that the pictures stood for sounds (as we might draw a bee to represent the sound ‘b’) of a language that had since died.

The key to unlocking this ancient mystery was the translation of the Rosetta stone. This is a man-sized black granite rock, inscribed in three different languages, unearthed by French soldiers knocking down a wall in the Egyptian town of Rosetta in 1799. The three-quarter-tonne stone was (reluctantly, after an attempt to sneak it away on a boat) handed over to British occupying forces and taken to the British Museum in London, where it still stands.

Egyptian hieroglyphs were intricate and colourful and were used to tell stories and demonstrate the power of the pharaohs.

Its value is that the three scripts carry the same message in a trio of languages: Greek, hieroglyphics and demotic (which is a later Egyptian language derived from hieroglyphics). Historians were able to translate the Greek text and establish that it announced a decree issued by King Ptolemy V in 196 BC. It begins: ‘The new king, having received the kingship from his father . . .’. For a code breaker, knowing the meaning of the message you wish to unravel is gold dust.

The stone features 1,410 hieroglyphs compared with 486 Greek words, which suggests that individual hieroglyphs do not necessarily represent whole words, and must therefore represent sounds. After some valuable groundbreaking work by Thomas Young, the stone was finally translated by Frenchman Jean François Champollion in 1823. Knowing that royal names were contained in oval shapes known as cartouches, he made the key discovery that Ptolemy’s name was written bit by bit as p-t-o-l-m-y-s, proving it by finding the same symbols used for the shared sounds ‘p’, ‘t’, ‘o’ and ‘l’ in writings about the famous queen Cleopatra.

This wonderful discovery was the key that opened the door to understanding the language of hieroglyphics and allowed archaeologists to learn to read other ancient Egyptian writings, shedding fresh light on the world of pharaohs, such as Rameses, and the many gods, such as the sun god Ra.

Among the early forms of written communication is cuneiform writing, in which letters are carved onto tablets (cuneiform means ‘wedge writing’). There is plenty of evidence that meanings were concealed even in such early writings, and the practice continued through the centuries.

AN ANCIENT TRADE SECRET

An early instance of cuneiform writing being enciphered dates from around 1500 BC. A small tablet giving a recipe for a pottery glaze (which must have been a trade secret at the time) was found on the banks of the River Tigris. The scribe had mixed up different sound symbols to make the text confusing to those outside his profession.

• There are records of secret writings that were being used for political communication in India in the 4th century BC, and the erotic textbook the Kama Sutra lists it as one of the skills women should learn.

• Early antecedents of the Kurds in northern Iraq employed cryptic script in holy books to keep their religion secret from their Muslim neighbours.

• A mixed-up alphabet carved onto a wooden tablet and thought to date from 7th-century Egypt is believed to be the world’s oldest cipher key.

• Medieval monastic scribes entertained themselves by adding messages in simple ciphers to the margins of texts they were copying out.

• An extraordinary 12th-century nun called Hildegard of Bingen constructed an alternative alphabet and created a new cryptic language, called Lingua Ignota, claiming the inspiration for it came through visions.

• Franciscan Friar Roger Bacon wrote about cryptography in his Secret Works of Art and the Nullity of Magic in the 13th century, listing seven different kinds of secret writing.

• Medieval builders carved masonic symbols into the stone of structures on which they were working, partly as a sort of signature and possibly to help decide how much each should be paid.

• The alchemists of the Middle Ages concealed their identities and formulae with code marks.

Native American tribes used smoke signals to send simple messages over long distances, working to a prearranged code. The practice was common in ancient China, and is still carried out by boy scouts today.

Many such puffs of smoke were most likely signalling the activities of the cowboys raising cattle on the land. To prove ownership of their beasts, these men also had their own branding alphabet based on three elements: letters or numbers, geometric shapes, and pictorial symbols. Originating in the 18th century, they were designed to identify cows over long distances and partly to combat cattle rustling (see box, below and illustration overleaf).

Hobos, who travelled around the US in the 19th century, developed a code of marks chalked outside houses to inform fellow tramps of what kind of reception they could expect. The signs had meanings such as:

• Doctor

• Danger

• Safe camp

• If sick, will care for you

• You can sleep in the hayloft.

OLD BRANDS

Cattle branding has been traced back 6,000 years to the Ancient Egyptians – tomb paintings show it taking place. There is also biblical evidence that Jacob branded his livestock.

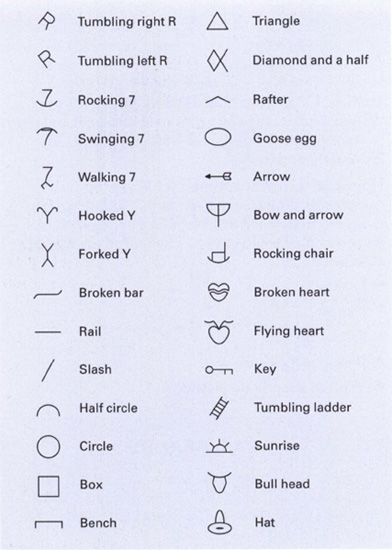

Some examples of the cowboy branding alphabet.

Numerous codes have been devised to aid communication, reflecting changes in the world over the last few hundred years: these signal codes enable the passing on of information over long distances.

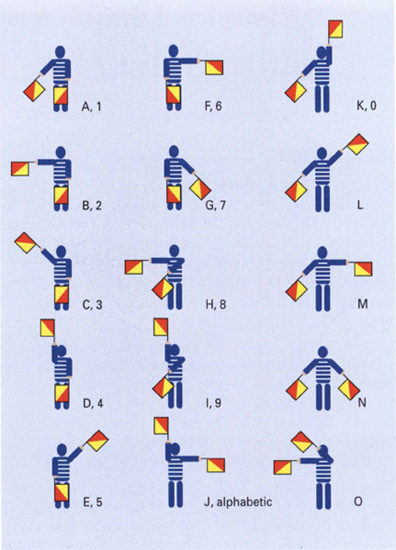

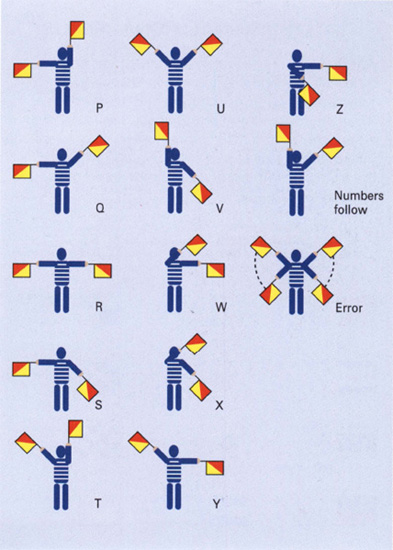

Semaphore is the common term for a system of signalling using a pair of flags. It was devised in 1817 by Captain Marryat of the British Royal Navy, who adapted it from that organization’s flag code of 1799. Although clearly developed for use at sea, the Marryat code, or the Universal Code of Signals, as it is also known, is just as effective on land.

The flags are usually divided diagonally into red and yellow, and are moved like independent hands on a clock face. Each position represents a letter, so messages are spelt out. There are also set signals for recurring content, such as ‘Error’ and ‘End’, while the digits zero to nine are represented by the first eleven letters of the alphabet (J also doubles up as ‘Letters follow’) when preceded by the message ‘Numbers follow’.

It is said that the semaphore flag system was the fastest method of visual communication at sea – quicker than a flashing light using Morse code (pages 30–3) – and was valuable even in more modern times as it allowed ships to send each other messages while maintaining radio silence.

Semaphore code allows for communication across long distances.

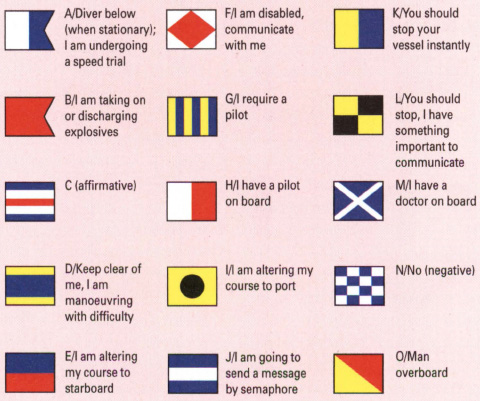

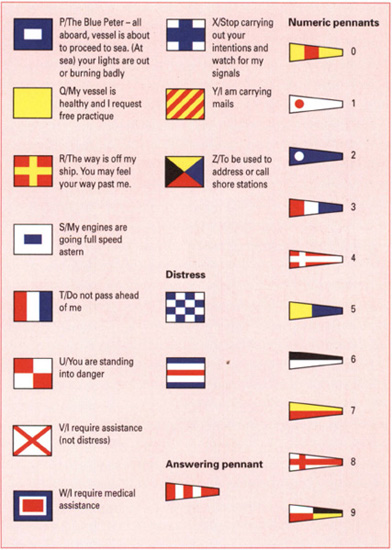

INTERNATIONAL SIGNAL FLAGS

Another flag signalling system used at sea is International signal flags, in which each flag represents a letter or number, and also carries a message for common situations at sea: two-letter signals for emergencies, three letters for general information. This is particularly useful when ships are trying to communicate without a common language.

These flags enable communication across different languages.

The optical telegraph revolutionized communication.

Copper pans, a clock face, a set of pulleys and the telescope all made a contribution to the development of a coded communication system that had a major impact on 19th-century Europe, though it is now almost forgotten.

Developed by French brothers Claude and René Chappe in the late 18th century, the optical telegraph evolved from the materials listed above into a signalling system of movable black-and-white panels mounted on a beam with angled arms that mimicked a person holding a pair of flags in different positions. It allowed rapid communication as far as you could see. Soon there were chains of optical telegraphs covering much of western Europe. This was revolutionary at a time when the fastest messages travelled at the speed of a galloping horse. The optical telegraph was a key pan-European communication system until it was superseded by the electric telegraph, which used Morse code (see pages).

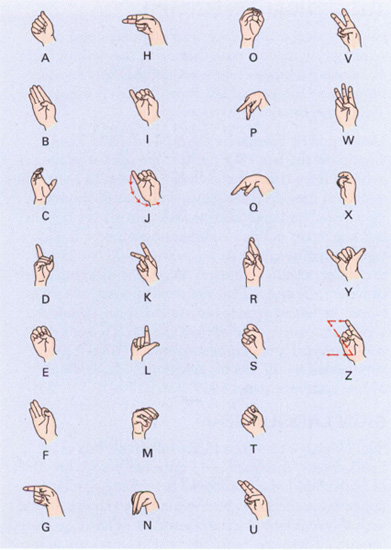

Sign language uses the oldest coding method of all: hand signals. Although used informally since the birth of humankind, the first books describing sign language appeared in the 17th century, aiming to communicate with the deaf by using hand gestures as an exaggerated ‘mouth’. There are hundreds of sign languages in use around the world, the two most common being American Sign Language (ASL, see illustration, left) and Signed English. In addition, many sports officials use standardized hand signals for some communication.

American sign language uses an alphabet for spelling out words.

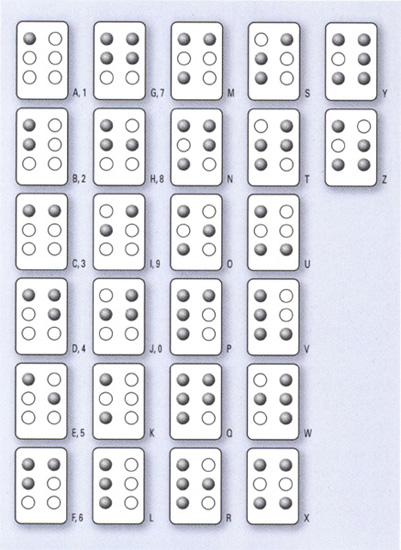

Braille is a non-secret code that allows the blind to read. Like many codes, its origins lie in the need for the military to communicate without being detected or understood.

The story begins with Artillery Captain Charles Barbier of Napoleon’s French Army in the early 1800s. Frustrated by the difficulty in reading messages safely on the front line (where smoke and the chaos of battle hindered communication, and lighting a lamp created an easy target for the enemy), he devised a code using 12 raised dots on paper, called night writing. Unfortunately, his fellow soldiers found it too difficult to learn and it was not adopted.

Thinking that it might have a role in helping the blind to read, Barbier started to visit schools for the blind. In 1821 he demonstrated his code to a group of children at the Royal Institution for Blind Youth in Paris. The audience included the 12-year-old Louis Braille, who had been blinded by accident nine years previously. Braille quickly mastered the system but found he could simplify it to use just six dots. Although he published the first Braille book in 1837, it did not catch on around the world for another 30 years.

Braille has since been adapted to nearly every language on earth and remains the major medium of literacy for blind people everywhere.

THE BRAILLE ALPHABET

The Braille alphabet of raised dots includes numbers and punctuation marks.

• Each Braille character is made up of six dot positions, arranged in a rectangle.

• A dot may be raised at any of the six positions, and a total of 64 combinations is possible, including the spaces (see opposite).

• There are Braille codes for representing shorthand, mathematics and music.

Braille characters use a system of raised dots.

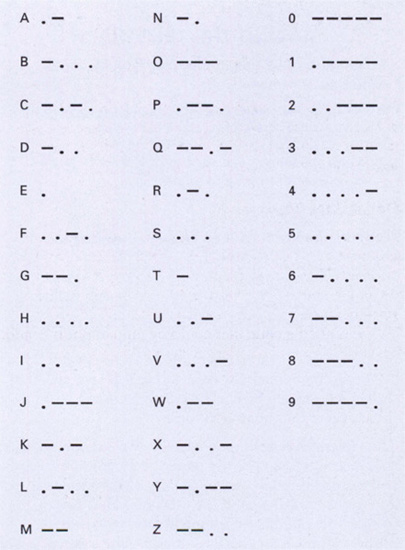

Morse code is the most famous code in the world. It allows rapid communication over long distances along wires or radio waves, or via sound or light in an easy-to-learn system of dots and dashes.

The American Samuel Morse had attempted various inventions and money-making schemes before he chanced across the opportunity to send messages along wires. He enlisted the help of experts in the field of sending an electric pulse over long distances, and in 1838 designed a code that could be tapped out by hand. Showing admirable understanding of the practicalities of communicating language, he ensured that the most frequently used letters could be entered with the least effort, thus the code for ‘e’ is a dot, and for ‘t’, it is a dash.

This combination slowly won over a sceptical public and the first telegraph line, following the 40-mile railway track between Baltimore and Washington, launched in 1844 with the message: ‘What hath God wrought’.

Morse code was treated originally as a novelty (public chess matches were played via it) and struggled to overtake the already established optical telegraph (see pages), but gradually its advantages of cheap and very fast communication were recognized. In England, it enabled the arrest of the murderer John Tawell on 3 January 1845 when his description was sent ahead of the train on which he had fled, leading to his arrest on his arrival at Paddington Station.

Morse code is designed so that the most frequently used letters require the least effort.

BEYOND THE TELEGRAPH

In addition to its use in the telegraph system, Morse code is also used:

• when armies and navies use a heliograph (which reflects the sun’s rays);

• when messages are sent with the Aldis lamp (a powerful light used at sea);

• in radio messages.

Airline pilots still have to know it, even today.

The telegraph system grew rapidly. Skilled operators soon learned to ignore the paper printouts of messages and instead listened to the clicking of the receiving apparatus to understand the message. They began using abbreviations for long common words or phrases and many variations of code words were introduced. This was encouraged by a thrifty public keen to keep the length of messages to a minimum as payment was by the word. In the American Civil War (1861–5), the telegraph was used widely for the first time in warfare, and it was imperative to encrypt important messages because of the ease of interception.

Banks, in particular, were keen to develop secure codes as it allowed them to transfer money electronically. By 1877, nearly $2.5 million was being telegraphed every year in nearly 40,000 separate transactions. Because the messages were legally binding contracts, even marriage ceremonies were known to be conducted using the equipment, with the bride and groom clicking out ‘I do’ while a congregation of telegraph operators down the line listened in.

Morse code underwent a few refinements as it continued to serve as a code in radio communication. It remained in use on the seas until it was replaced by a satellite-based communication system in 2000.

SOS

The dit-dit-dit-dah-dah-dah-dit-dit-dit SOS distress call does not stand for ‘Save Our Souls’, as many people believe. It is a code indicating that the operator will no longer be able to send messages. The lack of gaps shows that it does not represent individual letters.

Communications technology, such as computers and mobile phones, has spawned a new set of codes aiming to save costs and time by making communication as brief as possible. These are simply modern forms of shorthand, but they also carry great social kudos for the young.

Around the world, people are creating a new code language at their keyboards, which is the digital equivalent of Pig Latin (see pages) with a few hieroglyphs thrown in for good measure. Widely used in chat rooms, among hackers and computer gamers, leet, or leetspeak (leet is a corruption of ‘elite’), enables rapid communication to take place by using keyboard characters as short cuts for sounds, words and phrases.

Some basic rules for leet are:

• Numbers can replace the letters they resemble, so ‘leet’ is ‘1337’, ‘B’ (hence ‘be’) is represented by ‘8’, ‘9’ replaces ‘G’, ‘5’ or ‘$’ stands for ‘S’ and ‘4’ is ‘A’. Thus ‘leetspeak’ is ‘13375p34k’.

• Letters substitute for sounds, so words ending in C or K now end in X, and Z supplies ‘S’ and ‘ES’ endings.

However, there are many variations. For example, the first three letters of the alphabet can be shown as:

A: 4,Λ, @, /-\,

B: 8,6,|3, |:,P>

C: [, <, (

One of the rules of leet is that there aren’t really any rules: spelling and grammar conventions are largely ignored and the idiom is constantly evolving. It is particularly popular in communication between computer gamers and hackers.

Here are a few leet words and phrases:

• k3wL = ‘cool’

• m4d sk1llz = ‘mad skills’ – a talent

• n00b = ‘newbie’ – a newcomer

• y0 = ‘yo’, an alternative to ‘hi’.

Txt tlk, or txt lingo, is the language of the mobile phone, so it has similar aims to leet but has been adapted to suit use on a handset. However, it is also used in internet chat rooms along with leet. It developed through the introduction of the Short Messaging Service (SMS), which allows the sending of text messages of up to about 150 characters and is used for conversations and news and financial information services. The first message was sent in 1992, and just over a decade later texts were being sent at a rate of 500 billion per year.

Some basic rules for txt tlk are:

• Vowels are omitted.

• Whole words can be left out if the sense is not affected.

• SpacesAreMarkedByCapitals.

Txt words and phrases:

2 = ‘to’ or ‘too’

4 = ‘for’ as in ‘b4’

C = ‘see’

R = ‘are’

Y = ‘why’

8 = the syllable ‘ate’ as in ‘gr8’ or ‘m8’

bf or gf = ‘boyfriend’ or ‘girlfriend’

thx = ‘thanks’

np = ‘no problem’

Keyboard or handset characters are also used to create pictorial messages such as these ones (try tilting your head if you don’t see how it works):

O:-) = angel

:-! = bored

%) = confused