![]()

TRADE, PEOPLE, FINANCE, AND DATA

SHANGHAI’S SPRAWLING DOWNTOWN OFFERS A SNAPSHOT OF GLOBALIZATION past, present, and future. The Huangpu River carves an arc past the Bund, home to the Beaux-Arts corporate headquarters buildings the colonial powers erected in the nineteenth century. On the eastern shore, Pudong, which was a collection of rice paddies and villages thirty years ago, has sprouted into a modern financial center. The gleaming skyscrapers—ICBC Tower, HSBC Tower, Citigroup Tower, Deutsche Bank Tower—belong to the giant financial institutions that act as portals for the vast amounts of capital flowing around, in and out of the country. From here, a maglev (magnetic levitation) train shuttles tourists and businesspeople eighteen miles in seven minutes to Pudong International Airport, which saw 47.2 million passengers come through its massive terminal in 2013.1 While barges still ply the waters and dock at the city’s wharves, the real action takes place at the giant Yangshan Port. The world’s busiest port, connected to the mainland by the 20.2-mile Donghai Bridge, handled about thirty-two million containers in 2013, more than double the volume in 2004.2

The story of trade in Shanghai—and in China—is no longer simply a matter of dollars and euros arriving in exchange for manufactured goods shipped to the United States and Europe. Goods, services, and people flow in and out of all of Shanghai’s ports of entry at a pace that is noteworthy for its size and growth. Oil arrives from Congo, motorcycles leave for Vietnam, tourists fly to Paris, investments flow through the banks to factories in China’s interior, and funds flow out to buy bonds in New York. The often-frenetic activity embodies the rising pace, intensity, and complexity of global connections, the higher flows of people, goods, services, money, and information.

These tides have been rising for decades. Connections have always risen along with growth. But the long-term trend is accelerating. In the twentieth century, things moved, often at slow speed, from one point to another along reliable routes. In the twenty-first century, things, people, and information move much more quickly, often at the speed of sound, sometimes at the speed of light. And in this second great wave of globalization, cross-border flows of goods, services, finance, and people are growing and dispersing rapidly. Driven and amplified by the disruptive forces of growing prosperity in the emerging world and by the spread of the Internet and digital technologies, these flows—and the greater connections they spawn—are changing the nature of the game. With each passing year, more goods, services, people, information, and capital move around from place to place. These flows add between 15 and 25 percent to global GDP growth each year. If the impact of these disruptive forces continues, flows could triple in volume by 2025.3

Few countries and companies are sitting this out. As Ann Pickard, executive vice president of Arctic at Royal Dutch Shell, notes, “I think the world is far more interconnected. We’ve got Alaska thinking about Norway thinking about Greenland. The interconnectedness becomes absolutely important.”4 The web of the world economy is ever more intricate and complex. These flows present both opportunities and the potential for crisis. Companies have never been more able to reach more new customers, tap into new sources of financing, and find new sources of both supply and demand. But greater global interconnections have also produced a proliferation of channels that can transmit shocks across sectors and borders. A disruption in a seemingly remote area—an earthquake in Japan, a political crisis in Ukraine, a fiscal meltdown in Greece—can have instantaneous effects around the world. In order to tap into this flow of energy without getting shocked, it is imperative to understand how these interconnections affect your business, and then to reset your intuition accordingly.

A NEW WAVE OF GLOBALIZATION: TRADE IN GOODS AND SERVICES

The growth of trade is a centuries-long trend that has accelerated with containerization and higher productivity of transportation networks. Today, a host of new technologies and networks are amplifying the trend. The rise of consumers and businesses in emerging economies is remaking, intensifying, and deepening the process of globalization. The network of supply chains is growing more complex and has greater geographic reach, and the volume of goods and services moving around the world is on a scale and at speeds that are unprecedented. With the notable blip of 2009—the first year since 1944 in which the global economy shrank—the connections, and the volume of stuff flowing through them, have been growing much more rapidly than the economy as a whole.5

• Between 1980 and 2012, the value of total goods trade grew at a 7 percent compounded annual growth rate, while the value of services traded rose at an 8 percent annual rate.6

• In the same period, thanks to rapidly expanding supply chains, goods flows increased nearly tenfold in value, from $1.8 trillion to $17.8 trillion, and amounted to 24 percent of global GDP.7

• Fueled by dramatic declines in the cost of international communications and a sharp increase in travel, global services flows nearly tripled between 2001 and 2012, from $1.5 trillion to $4.4 trillion, or 6 percent of global GDP.8

• By 2011, the volume of global trade in goods and services had surpassed 2008 levels. Today, the world is more trade intensive than ever. The cross-border movements of goods, services, and finance in 2012 reached $26 trillion, or 36 percent of global GDP—1.5 times the share of GDP in 1990.9

International trade hasn’t simply grown in volume. It has broadened and branched out, like a river moving through its delta. In 1990, more than half of all goods flows were between developed countries. The typical transaction might have been a Toyota Celica shipped from Japan to the United States. But in 2012, such transactions accounted for only 28 percent of all goods flows.10

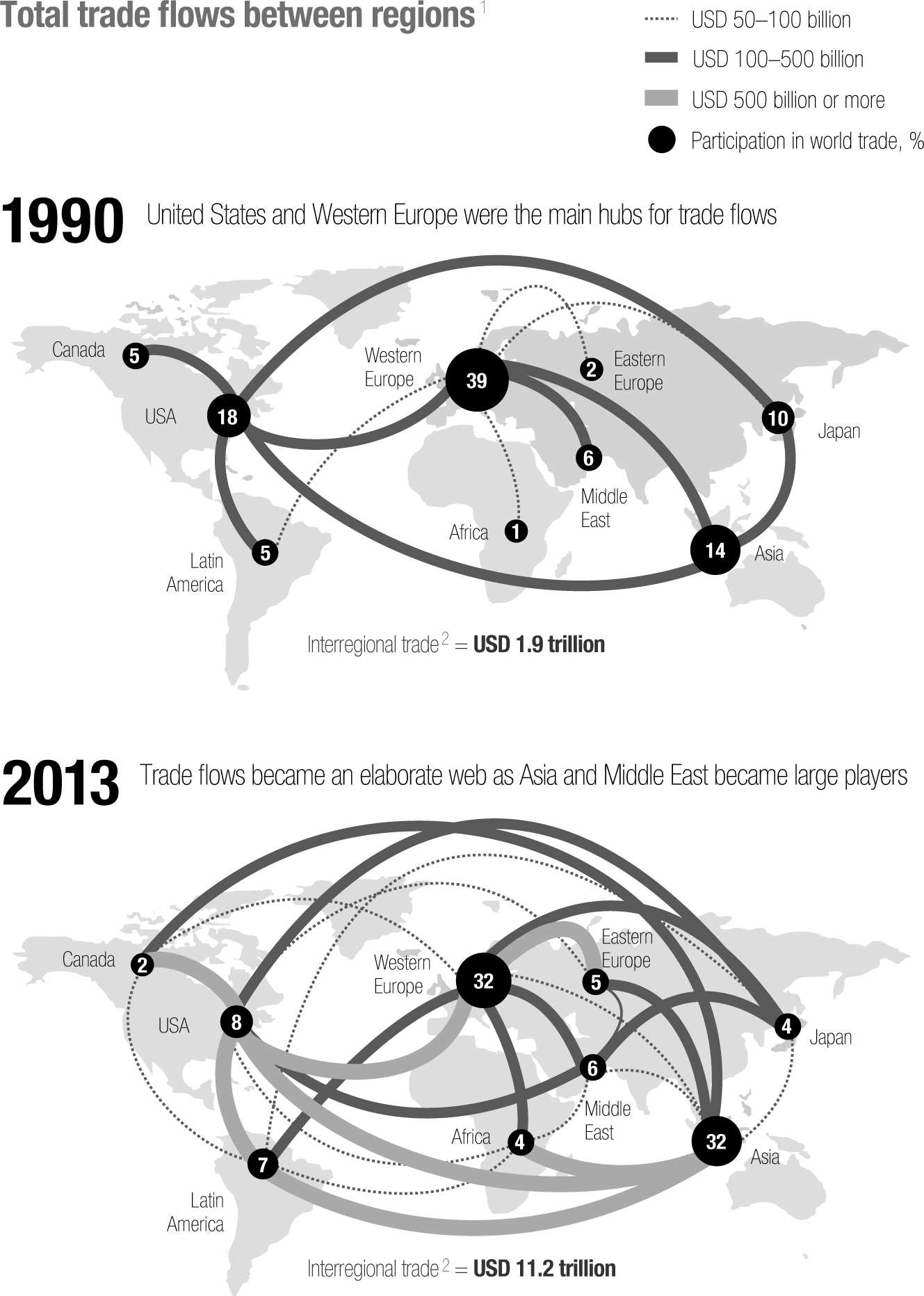

Since 1990, trade routes have evolved from hubs in the United States and Western Europe into a global web of trade, with Asia as the largest trading region. Emerging economies now account for 40 percent of all goods flows, and 60 percent of those go to other emerging economies—known as south-south trade. In 1990, this trade accounted for 6 percent of global goods flows; it rose to nearly 24 percent by 2012.11 It might, for example, involve a barrel of oil going from Congo to China, or soybeans farmed deep in Brazil shipped to Malaysia, or an Indian pharmaceutical shipped to Algeria. China’s bilateral trade with Africa has exploded, from about $10 billion in 2000 to nearly $200 billion in 2012.12 Trade between emerging economies is likely to continue to grow as a share of global trade as incomes in these countries increase, boosting the number of consumers with a voracious appetite for goods of all kinds, and as business activity grows.

In an important trend break, technology is shifting trade from the formerly exclusive province of large companies to an activity that all sorts of companies—even individuals—can participate in. Online platforms such as eBay and Alibaba facilitate production and cross-border exchanges. More than 90 percent of eBay commercial sellers export to other countries, compared with less than 25 percent of traditional small businesses.13 The types of goods being traded are changing as well. In the past, labor-intensive products shipped from low-cost manufacturing locations and commodities originating in resource-rich nations dominated global flows. Today, trade in knowledge-intensive goods like pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, and aircraft make up nearly 50 percent of the total value. Trade in knowledge-intensive goods is growing 30 percent faster than trade in labor-intensive goods such as apparel and toys.14 Twenty years ago, the prototypical traded object may have been a $3 T-shirt. Now it could be a 30-cent pill, a $3 e-book, or a $300 iPhone.

FINANCE

For decades, oil was the main liquid asset moving around the world. Today, the flows of black gold are abetted—and eclipsed—by the rapid movement of a different commodity: money. Finance enables trade, and the flow of capital has become a phenomenon in its own right. It is easier to ship large sums of money and credit than it is to send oil or shoes—you don’t have to put electronic money on a tanker or a container ship. So it is not surprising that financial globalization has proceeded at an even faster pace than trade globalization since 1990. Between 1980 and 2007, annual cross-border capital flows increased from $0.5 trillion to a peak of $12 trillion, a twenty-three-fold increase that was in large measure driven by Europe’s monetary and trade integration.15 Such flows fell sharply in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis and then bounced back. In 2012, estimated financial flows stood at $4.6 trillion, nearly five times the level in 1990.16

Trade routes have expanded and trade patterns have become increasingly more complex

1 Includes only merchandise.

2 This value does not include the trade flows between countries in a region. If intraregional trade flows are included, the total trade for 2009 is $18.3 trillion. Overall value estimate for 2013, breakdowns calculated on data until August 2010.

Updated February 2011/May 2014.

SOURCE: Global Insight – World Trade Service; McKinsey Global Institute analysis

As with the trade in physical goods, the flow of capital is becoming more varied and complex. Developing countries, long the recipients of private capital flows, are now emerging as sources of global foreign direct investment, and the web of cross-border investment assets has grown in depth and breadth. For example, Angola, a former Portuguese colony, has reportedly invested between 10 and 15 billion Euros into high-profile Portuguese assets in sectors such as media, banking, telecommunications, and energy.17 The investment office of S. D. Shibulal, one of the founders of Indian outsourcing giant Infosys, has purchased more than seven hundred apartments in the Seattle area.18 In May 2014, Chinese dairy firm Bright Foods paid about $1 billion for a majority stake in Tnuva, an Israeli dairy cooperative.19 Financial outflows from emerging economies rose from 7 percent of the global total in 1990 to 38 percent in 2012.20

Capital markets are the main international arenas in which money flashes around the world in seconds. But today, the big players are not just clustered in the traditional power centers of New York, London, and Tokyo. They’re also in Abu Dhabi, Mumbai, and Rio de Janeiro. While the assets of households in the United States and Western Europe grew on average 3 to 4 percent annually between 2000 and 2010, those of households in emerging markets rose much more quickly: by 23 percent annually in the Middle East and North Africa and by 16 percent in China, for instance. Total assets are still much smaller in emerging regions than they are in developed economies, but they are catching up.21

The forces of financial globalization were severely weakened in the 2008 recession and its aftermath. By 2012, cross-border capital flows had fallen 60 percent from their 2007 peak.22 But the long-term trend remains intact. As the global financial and banking system reconstitutes itself and becomes better capitalized, and regulation becomes more effective and coordinated, the financial system could effectively reset and enable the rapid growth of financial globalization to resume.

PEOPLE

People, too, are increasingly interconnected globally. While the number of people traveling, working, and studying globally has increased steadily for centuries, the past few decades have seen an explosion in the volume of those movements. Once people move to cities and earn higher incomes, it becomes much easier to move or travel to other countries. The number of international migrants—people living outside their country of birth—grew from 75 million in 1960 to 232 million in 2013, according to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.23 In the first ten years of the new millennium, the rate of immigration doubled compared with the 1990s. One of the new characteristics of immigration is that movement between developing regions has grown faster than immigration from developing to developed countries. The labor market, too, is becoming truly global for the first time. And the phenomenon manifests up and down the income and skills ladder.

Between 1994 and 2006, the ratio of foreign-born to US-born scientists and engineers working in the United States doubled. In Silicon Valley, more than half of business start-ups over that period involved a foreign-born scientist or engineer; one-fourth included an Indian or Chinese immigrant.24 Since 2012, 30 percent of Romanian resident doctors have left the country and moved to wealthier European Union countries, such as the United Kingdom, Germany, and France, in search of higher pay.25 More than 130,000 Bangladeshi migrant workers are working in Qatar, one of the richest Gulf states, with many of them engaged in building venues for the 2022 World Cup.26 In his book China’s Second Continent, the veteran foreign correspondent Howard French cites a common estimate that some one million Chinese citizens have moved to Africa in the past two decades. In Latin America, comparatively more prosperous southern countries like Chile, Argentina, and Brazil are exerting the type of magnetic force that the United States does to the north. In Buenos Aires, many of the taxi drivers and virtually all the people staffing corner fruit and vegetable stands are Bolivian. The International Organization for Migration reports that the Bolivian population in Argentina has increased by 48 percent since 2001 (to 345,000) and that the country’s Paraguayan and Peruvian populations have grown even faster.27

People are not just traveling more frequently for work. World tourism has also expanded exponentially. In 1950, only about 25 million people traveled beyond their own countries. In 2013, there were more than 1 billion international tourists. Their impact is massive, not just due to the money they spend but for the rich exchange of culture and knowledge they bring. Estimates put the GDP of the global tourism industry at $2 trillion and its payroll at more than 100 million people.28 More than 110 million US citizens—more than double the number in 2000—had valid passports in 2013.29 More than 100 million additional Chinese tourists are expected to travel abroad by 2020.30 Galeries Lafayette, the Parisian department store, now has an Asian department to accommodate the rising number of shoppers coming from China. At the top of Vail Mountain, the ski resort in Colorado, it is common to see Australian instructors teaching Mexican skiers how to negotiate black diamond slopes.

Students, too, are crossing borders in large numbers. More than 750,000 international college students study in the United States, 200,000 more than in 2006. A quarter of these students are Chinese.31 At Lake Forest College, a small liberal arts institution outside Chicago, of the 410 entering members of the class of 2015, 63, or 15 percent, hailed from thirty-three different countries. President Steven Schutt spends a portion of his year recruiting students—not just in New York and Boston, but in Shanghai and Beijing. “US education is a brand that travels well,” he notes.32

DATA AND COMMUNICATION

Perhaps the most dramatic change in recent years has been the speed at which information is flashing around the world. More than two-thirds of humans have a mobile phone, and the proportion is rising rapidly. “Today, there are more phones than people. . . . And we can call almost any part of the world at almost no cost through Internet services such as Skype,” notes Kishore Mahbubani, dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore. “This level of teledensity means that people have become interconnected at a level never seen before in history.”33 One-third of the planet is online. At more than 1.35 billion, the community of Facebook users is equivalent to the population of the world’s largest nation. Global online traffic rose from eighty-four petabytes a month in 2000 to more than forty thousand petabytes a month in 2012—a five-hundred-fold increase. Cross-border voice traffic has more than doubled over the past decade, and Skype call minutes have increased more than 500 percent since 2008.34

These connections have already had an enormous impact and are poised to have an even greater one, especially in developing countries. Internet-related consumption and expenditure is now bigger than either global agriculture or the worldwide energy sector.35 In 2005, mobile subscriptions in aspiring countries—defined as the thirty countries with the economic size and dynamism to become significant global players—accounted for 53 percent of worldwide subscriptions; just five years later, that share had risen to 73 percent. By 2015, 1.6 billion of the estimated total 2.7 billion Internet users globally are likely to be from aspiring countries.36

Many areas with large populations still have a great deal to gain from going online. Mobile subscriptions in Africa have rapidly increased, from fewer than 25 million in 2001 to around 720 million in 2012.37 This has significantly expanded Africans’ access to markets and services; the impact of mobile telephony on GDP has been three times as large as in developed economies. However, Internet penetration in Africa lags behind, and the Internet’s contribution to GDP in Africa averages just 1.1 percent, half that of its contribution in other emerging economies.38 Although Internet penetration is only around 16 percent on the continent, some 25 percent of Africa’s urban population goes online daily, with Kenyans (47 percent) and Senegalese (34 percent) leading the way.39 The economic opportunity this online gap represents is vast. By 2025, the number of Internet users in Africa could quadruple, to six hundred million, while the number of smart phones could rise more than fivefold to 360 million, bringing a $300 billion annual Internet contribution to GDP.40 Rocket Internet, the Germany-based global digital incubator, in 2013 struck a $400 million investment deal with South African mobile network operator MTN to develop a host of e-commerce start-ups in the Middle East and Africa.41 The joint venture will provide Rocket Internet with access to a huge number of new customers and allow it to further accelerate its practice of launching and scaling business models that been proven to work elsewhere. Examples of Rocket’s success in Africa include the Jumia e-commerce platform (modeled on Amazon.com), the Easy Taxi taxi-ordering app (modeled on Hailo), Carmudi auto classifieds, and the Jovago hotel-booking system.42

WHY IT MATTERS

The rise, diversification, and power of global flows are not just fascinating; they are of significant importance to businesses all over the world for several reasons.

First, the more connected you are, the better off you are. Although some companies and workers have been and will continue to be displaced by increased connectivity, research further reinforces long-held economic theories suggesting that countries, cities, and companies receive a net benefit by participating in flows. In advanced economies, multinational firms—with their global networks of customers, suppliers, and talent—tend to make outsize contributions to growth and productivity. Prior to the 2008 recession, multinationals made up less than 1 percent of all US companies, but they generated 25 percent of gross profits, 41 percent of productivity gains, and nearly 75 percent of the nation’s private-sector R&D spending.43

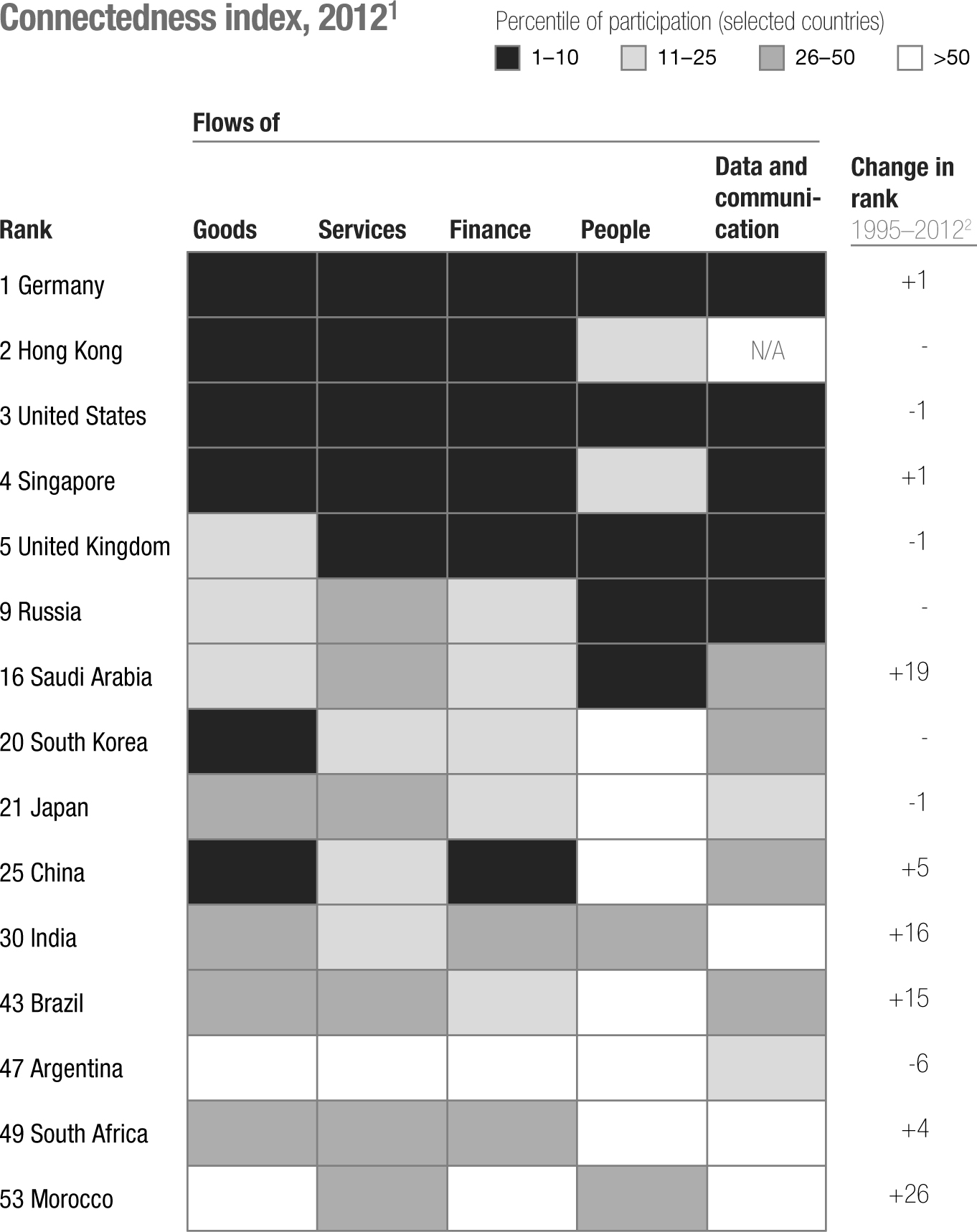

Connectedness matters for countries, too. Global flows add between $250 billion and $450 billion—or 15 to 25 percent—to global GDP growth each year and contribute to faster growth for countries that participate. In fact, the most connected countries can expect to increase GDP growth from flows by up to 40 percent more than the least connected countries.44 Germany ranked as the most connected country in the world in 2012.45 Developed economies by and large dominated the rankings, though some large emerging economies have made significant gains in the past two decades. India and Brazil, for instance, jumped fifteen and sixteen ranks, respectively, thanks to their participation in global flows of services (India) and commodities and finance (Brazil). China rose five spots due its participation in goods and financial flows. The fastest riser of all, Morocco, leaped twenty-six spots in the connectedness ranking.46

Second, global interconnections are rewriting the rules of the game and are one of the major factors changing the basis of competition, as we will see in Chapter 9. The new landscape of global flows offers more entry points to a far broader range of players. Large companies from emerging markets are increasingly formidable competitors. Traditional sector boundaries are blurring. Small businesses and start-ups can be instantly global. Whereas in the past, developed-economy multinationals competed against each other, today’s competitors can be individuals and companies in all shapes and sizes, from anywhere in the world and from unexpected sectors. Put differently, if a business today has data and a platform that engage millions of people, few attractive business opportunities in just about any sector are “unthinkable” for it.

Third, global flows provide companies with new ways to put their assets to productive use. Large firms can mobilize cash assets on their balance sheets to provide financing to companies and projects that can unlock new markets, as General Electric has done in Africa. For GE, Africa is one of the most promising growth regions, having produced revenues of $5.2 billion in 2013. GE in 2014 partnered with the Millennium Challenge Corporation to provide $500 million in financing for the Ghana1000 project, a huge, 1-gigawatt power plant the company is helping to build in Western Ghana.47 Beyond tapping tangible assets, companies are able to mine intangible assets—knowledge, competencies, data—that can help them participate in global flows. Some do so for philanthropic purposes. Coca-Cola used its market distribution expertise in sub-Saharan Africa to manage the storage and delivery of AIDS drugs in countries such as Tanzania. “We’re not lending our trucks or our fleet, or our motorcycles,” as Coca-Cola CEO Muhtar Kent put it. “We’re lending our expertise.”48

Trade routes have expanded and trade patterns have become increasingly more complex

1 Migrants data from 2010 used for people flows; 2013 cross-border Internet traffic used for data and communication flows. For data on complete country set, download the full report, Global flows in a digital age: How trade, finance, people, and data connect the world economy.

2 Calculations exclude data and communication flows, for which data are not available for 1995.

SOURCE: IHS Economics and Country Risk; TeleGeography; United Nations Comtrade database; World Development indicators, World Bank; Word Trade Organization; McKinsey Global Institute analysis

Finally, a more interconnected world leads to some surprising new outcomes. Several decades ago, the sovereign default of a small economy like Greece would barely register on the world’s financial radar. (Indeed, Greece has been in default on its debt around half the time since gaining independence in the nineteenth century.)49 But with Europe on a single currency and a high level of integration in the financial sector, Greece’s fiscal woes threatened banks in Germany, France, and the United Kingdom. Similarly, natural disasters or seemingly isolated geopolitical conflicts can disrupt supply chains or access to markets for players around the globe. Commodity prices are also showing an interesting new pattern. The correlation between commodity prices and the price of oil is now greater than at any time since the oil-shocked 1970s. In the 1980s and 1990s, prices of commodities such as corn, wheat, beef, and timber were largely uncorrelated with the price of oil (or even negatively correlated, in the case of timber); they now move in lockstep. This phenomenon can be explained by several factors: the growth in demand for resources from developing giants such as China; the fact that some resources (oil) are substantial input costs for other resources (grains); and the rise of technology that allows substitution between resources (like corn-based ethanol for oil). The combination of increasing correlation, surging demand, and supply constraints points to more volatility in commodity prices in the years to come.

When it comes to dealing with such disruptions—and the opportunities and risks they present—the most agile companies will have a significant advantage. In fact, the companies that perform well on measures of agility, such as shifting capital reallocation from year to year, post significantly higher performance with lower risk. Based on data from more than 1,600 companies, we found that total return to shareholders of the top one-third most agile companies—those with the highest capital reallocation year after year—was 30 percent higher than that of the least agile companies, whose capital allocation remain fixed year after year.50

The auto sector provides an excellent illustration of the increasing focus on agility. In recent years, Volkswagen has moved toward a modular architecture that provides greater flexibility for manufacturing several products on the same assembly lines.51 BMW maximizes asset agility through the use of its Mobi-Cell, a robot that can be moved from plant to plant. Toyota standardizes line design and a host of processes across models to ensure greater flexibility. But other sectors have been striving to become more agile as well, often by sharing information and working more closely with suppliers. Helix, a maker of high-performance vacuum pumps, breaks its manufacturing processes into so-called subprocesses and shares each subprocess with suppliers. In case of a disruption in Helix plants, suppliers can easily take over parts of the manufacturing processes. A leading retailer in the United States shares its data with suppliers at the point of sale through an integrated IT system, so that the suppliers can also be aware of real-time delivery flows.52

ADAPTING TO AN INTERCONNECTED WORLD

Most executives have thought in global terms for years. Yet established multinationals, mostly from advanced economies, remain significantly underweight in emerging markets, even as newcomers from these countries are expanding aggressively. The accelerations in global interconnectivity require an intuition reset on the part of companies. They must plan early to scale up globally, tailor business models to new markets, get to know new competitors, develop global talent, and prepare for shocks and volatility in an increasingly interconnected world economy. Businesses that focused mainly on cost effectiveness in global supply chains now need to consider how “value” chains may evolve—who the participants may be, which regions could play a role, and how value could shift along the value chain.

Just as the introduction of electricity was an important factor in pushing the world’s industrialized economies into higher gear a century ago, the current of economic energy from global economic flows coursing through the system offers similar potential today. Incumbent firms will need to brace for a new wave of competition propelled by the lower cost of starting and scaling up a business in the new era. Capturing the opportunities emerging from these flows requires business leaders to rethink the positioning of their companies’ physical locations, the way they use digital platforms, the nature of the competition they face, and the prospect of potential shocks.

Prepare for Entrants from Anywhere

It is important that companies position themselves smartly to take advantage of flows. Here, too, the technology revolution is providing unrivaled opportunity for companies of any size and age to be instantly international. Start-ups can immediately tap into global networks for talent (oDesk), funding (Kickstarter and Kiva), and suppliers (eBay and Amazon) through a host of online platforms. We have dubbed this rapidly growing class of companies that are born global “micro-multinationals.” Virtually all technology start-ups have some cross-border links from the outset. Among many examples of new micro-multinationals is Solar Brush, a Berlin-based start-up that has developed lightweight robots that clean solar panels. The company has an office in Chile, has presented at a business plan competition in Washington, DC, and is targeting customers throughout the United States and the Middle East.53 Shapeways, a company founded by Dutch entrepreneurs and based in New York, provides 3-D printing services and a platform to sell 3-D printed designs to customers around the world.54

The instantly plugged-in phenomenon isn’t confined to the technology and digital sectors. Even traditional industries such as manufacturing are increasingly seeing small businesses with multiple-country production sites and global operations, practices once reserved for established multinationals. In the United Kingdom, many small and midsized engineering companies serve customers around the world and operate multiple plants in a mixture of low-cost and advanced-economy locations. Bowers & Wilkins, a UK-based firm that makes high-end speakers and has consolidated turnover above £100 million, has invested in a purpose-built factory in China, which now makes much cheaper models of its original product.55 Colbree, an electrical and military equipment parts manufacturer, operates plants in the United Kingdom and Thailand. “Having the Thailand plant has been a big help to gaining new customers which are keen to benefit from the lower costs that are possible with the factory in Asia,” explains Robert Clark, Colbree’s general manager. “But at the same time they like to see us maintain our most advanced production technology in Britain.”56

These instantly global new entrants are not confined to developed economies. In fast-growing developing economies, more than 143,000 Internet-related businesses launch every year.57 Jumia, a Nigerian e-commerce company that now operates in Ivory Coast, Kenya, Egypt, and Morocco, in 2013 became the first African winner of the World Retail Award for “Best Retail Launch of the Year.”58 M-pesa, a mobile-money service started in Kenya, is now disrupting traditional banking, payments, and money-transfer service providers across Africa.

Build New Global—and Digital—Ecosystems

Digital platforms enable companies to expand rapidly and profitably to customers further away from their home markets than was possible in the past. Building cross-border ecosystems ranging from global supply chains to innovation networks could help companies take advantage of this opportunity.

Many companies are exploiting global interconnections and digital platforms to weave together networks of suppliers, distributors, and after-sales service providers—not just for procurement but also for preemptive maintenance that reduces production downtime, and for more efficient parts supply. The Boeing Edge, a new service division of Boeing, is seeking to transform the company from a traditional supplier of aviation equipment into something that more closely resembles a “digital airline.” The company aims to use the vast amounts of data that the airline business generates to build an integrated information platform. By connecting real-time data from aircraft, passenger engineers, maintenance groups, operations staff, and suppliers, Boeing believes it can help its customers—airlines—maximize efficiency, profitability, and environmental performance.59 And as firms like Boeing and Airbus push toward increased digital tracking of individual parts and components, companies such as Fujitsu and IBM are becoming part of the aerospace ecosystem through their RFID and other automated intelligence tracking products and services.

Companies are also relying on digital platforms to reach potential partners, to connect customers, suppliers, and financiers and to crowd-source ideas. Etsy, an online global marketplace in which independent artisans sell a wide range of products, connects thirty-million buyers and sellers and exemplifies the twenty-first-century digital ecosystem. The company recently partnered with Kiva to help crowd-source funding for its artisans. In addition to providing a digital portal that links buyers to sellers, Etsy provides entrepreneurial education and connects designers to suppliers. In 2013, the Etsy community generated more than $1.35 billion in total sales, a 50 percent increase from 2012.60

Pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca launched a digital open innovation platform in 2014 and aims to connect with researchers and academics at the UK Medical Research Council, the US National Institutes of Health, and similar organizations in Sweden, Germany, Taiwan, and Canada, among others.61 Consumer packaged goods companies, including Unilever and Procter & Gamble (P&G), often engage customers in new product development. Unilever’s “Challenges and Wants” digital portal is a tool for developing partnerships with innovators on topics from sustainable laundry products to improved packaging.62 And German equipment-maker Bosch uses its innovation portal to connect with individual and institutional researchers in power tools, new materials and surfaces, and the automotive aftermarket.63

Exploit Your Position in Global Flows

Countries and cities that have developed as hubs for certain types of flows have created a competitive advantage. Companies tapping into these hubs will likewise be able to benefit.

Take the United States, which is ranked number one in people flows, as an illustration.64 Broadly speaking, US-based firms are unrivaled in their ability to attract global talent. Those positioned in hubs that are already global capitals—New York for finance, Houston for energy, Los Angeles for entertainment—are particularly well situated to do so. The impact of foreign entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley, for instance, has been significant. One-third to one-half of Silicon Valley high-tech start-ups have foreign-born founders. Foreign-born residents represent 36 percent of Silicon Valley’s population, almost triple the national average of 13 percent. Among all adults in Silicon Valley, 46 percent have at least a bachelor’s degree, compared with the national average of 29 percent. Foreign talent has provided critical engineering skills, often developed at US universities, the lack of which might otherwise have hampered Silicon Valley’s growth.65

Take Frankfurt as another illustration. It is the highest-ranked city in terms of participation in data and information flows globally and is home to the German Commercial Internet Exchange, which handles over one-third of Europe’s Internet traffic.66 The city houses over five thousand software firms, such as SAP and Symantec, and is Germany’s hub for industries that benefit from proximity to high bandwidth and connectivity, such as financial services and games development. Ironically, even in an area of instant communications, companies are realizing the benefits of locating people-intensive operations in close physical proximity to other firms. In the late twentieth century, many businesses tried to carve out their own environments in vast campuses and office parks in the suburbs of North America. But the efforts to isolate corporate headquarters have often proven to be unproductive and are falling away in favor of sites that are more integrated into cities.

If your business is not yet taking advantage of being located in a major hub, considering whether to move to one should be on your agenda. Western multinationals have moved portions of their operations to Singapore precisely because it is a major conduit for Asian flows of goods, services, and finance. Singapore has the highest density of regional head offices relative to its GDP in the world. Nearly half of all large foreign subsidiaries in emerging Asia outside China are located in the city.67 Examples of companies that have located in Singapore include P&G, which moved its beauty and baby-care divisions from Cincinnati in 2012 to position itself in the growing Asian market.68 Unilever opened a new state-of-the art leadership development center in Singapore in 2013—its first training center outside the United Kingdom.69 In 2009, Rolls-Royce relocated its marine business from London to Singapore, reflecting Asia’s emergence as the world’s center for shipping.70

Be Agile in an Interconnected World

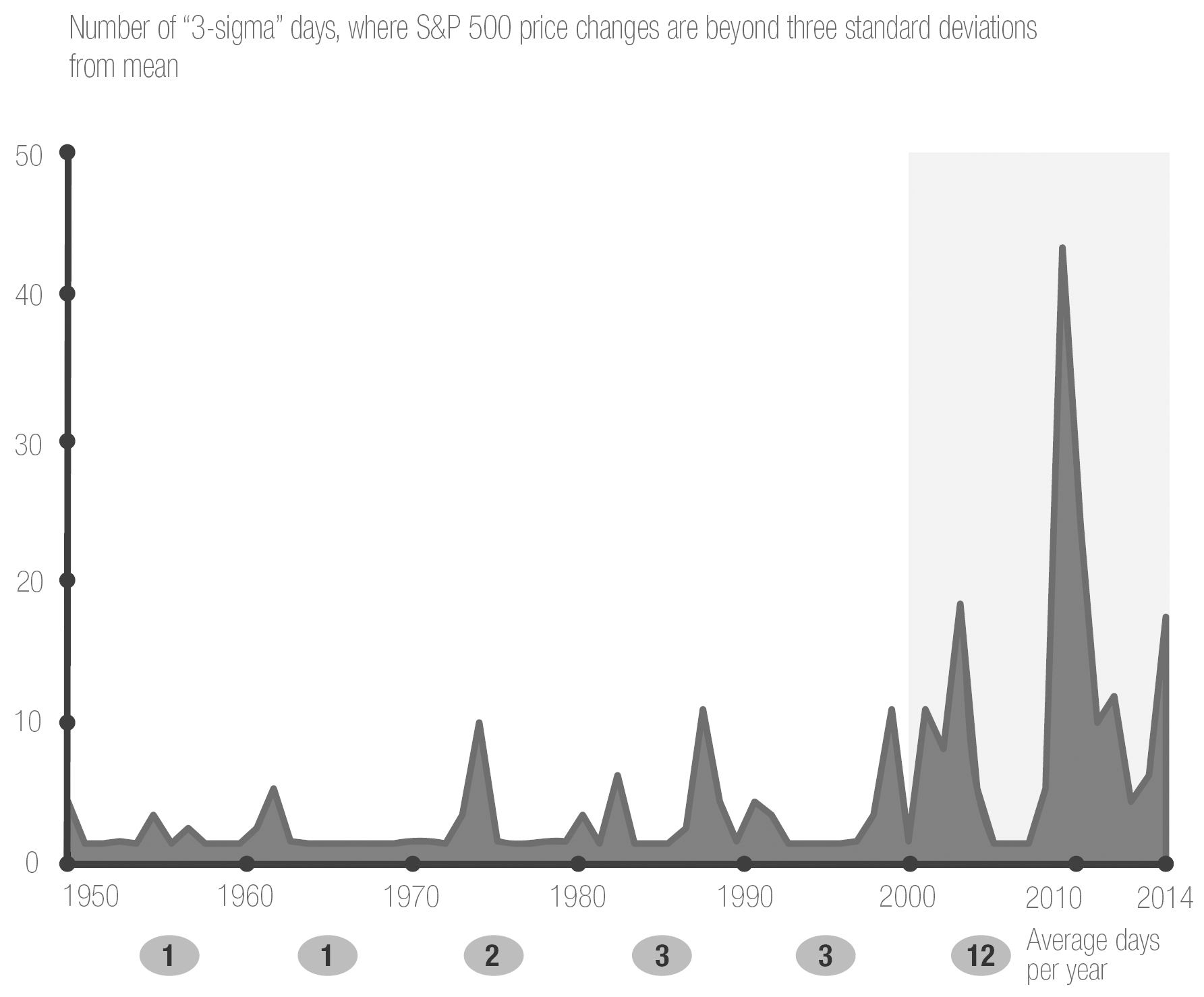

Fostering global interconnections also means reevaluating the way you think about opportunity, risk, and volatility—and how to respond nimbly. On the one hand, an interconnected world should bring opportunities to diversify risk and improve stability. In a highly connected world, it is much easier to offer round-the-clock customer service by English-speaking call agents in locations such as the Philippines and Costa Rica. However, disruptions can now travel around the world much faster and through the same channels that enable diversification and redundancy. Shocks can be transmitted—more quickly than ever—through financial and physical markets, the same way pain travels throughout the nervous system. Now that supply chains are longer than ever, and trade relationships of all types span the globe, they are in many ways more fragile. Product quality issues, supply-chain problems, and natural or man-made disasters can quickly and massively affect businesses in unexpected and uncontrollable ways. “These days, there are things that just come shooting across the bow—economic volatility and the impact of natural events like the Japanese earthquake and tsunami—at much greater frequency than we’ve ever seen,” said Ellen Kullman, chief executive officer of DuPont. “And the world is so connected that the feedback loops are more intense.”71

The external environment is volatile, with capital markets increasingly characterized by more extreme events

SOURCE: Standard & Poor’s; McKinsey Global Institute analysis

In the old paradigm, companies sought to insulate themselves from disruptions by bulking up, relying on proven strengths, and sticking to their core competencies. Today, however, agility is increasingly becoming a focus. Agility, the ability to act quickly and nimbly in response to problems that arise, is a vital attribute for thriving in the age of accelerating global flows. Companies that invest in preparing for, detecting, and being able to respond quickly to sudden crises will have a vital competitive advantage. After seven of its factories were hit by the Tohoku earthquake in March 2011, the semiconductor manufacturer Fujitsu recovered its production levels in less than a month. The speedy recovery was possible because Fujitsu had changed its production processes after a 2008 earthquake in Iwate. The new emergency response strategy included devising ways to rapidly restore electricity, water, and other utilities in case of disaster. It also built redundancy in manufacturing across plants so that unaffected factories could cover for damaged facilities.72

It’s easier for a business to develop these kinds of agile responses to the opportunities and risks presented by global linkages than it is for a nation to do likewise. But it is no less vital that countries do so. As we’ve noted, the more nations are connected to global trade, the faster they tend to grow. In order to reduce their exposure to global shocks, some countries have started implementing systematic mitigation measures that reduce their vulnerability.

Tanzania is one country that recently diversified its trade exposure, mitigating further risks from dependency on advanced economies. Tanzania once relied heavily on the export of agricultural commodities to developed economies. In recent years, it has enacted reforms aimed at liberalizing financial markets, diversifying production, building a manufacturing base, and focusing more on exports to emerging nations like China and India. As a result, the proportion of Tanzania’s exports sent to Asian and African countries has risen from 30 percent in the early 2000s to more than 60 percent today. In 2009, when the developed world remained mired in a deep recession, Tanzania’s economy grew 6 percent.73

![]()

Like information technology, the rising flows of global connections are both a tool to be exploited and an unavoidable force to be reckoned with. The keys are understanding them on their own terms and making concerted efforts to ride the waves without drowning in them. Smart planning, a willingness to change, and an openness to new ways of conducting and managing business will all be vital attributes in harnessing the power of global flows.