![]()

Tapping the Power of the New Consuming Class

VERY FEW PEOPLE HAVE HEARD OF CLARKS VILLAGE SHOPPING CENTER in the small town of Street, in southwest England. Even fewer count it among the globe’s “must-visit” shopping destinations. And virtually nobody would associate it with the boom in emerging-market consumerism. Yet as a closer look at the history of and recent visitor patterns to Street reveals, emerging markets—specifically China—have had a surprising influence on this small town in rural Somerset.

In the nineteenth century, Street’s most prominent Quaker family, the Clarks, and their shoe factories were the town’s lifeline. As Clarks brand grew in strength and international presence, Street flourished, surviving the Industrial Revolution and two world wars largely unscathed. But it couldn’t weather the rise of low-cost manufacturing in Asia in the late twentieth century.1 As the quality of Chinese- and Vietnamese-produced shoes rose, Clarks needed to move production offshore to remain competitive. By 2005, every one of Clarks’ UK factories had shut down.2 In Street, redundant factory buildings were converted to form Clarks Village, a designer outlet shopping complex that opened to the public in 1993.3

Fast-forward twenty years, and the shopping complex—with more than ninety-five stores, over a thousand employees, and four million visitors each year—has become a new lifeline for the town. In an era when many derelict high-street stores are sad reminders of the recent recession, Clarks Village is booming.4 The unlikely ingredient in Clarks Village’s secret recipe? Emerging-market consumers. Chinese tourists have become an increasingly important source of retail, leisure, and hospitality-industry income across the United Kingdom, contributing over £550 million ($878.5 million) to Britain’s economy in 2013.5 Building on its unique tourist-route location, on the way to Cornwall and Devon, Clarks Village has added organized tourist bus visits and VAT advice to its offerings. So, in addition to attracting price-conscious British shoppers, Clarks Village now draws thousands of Chinese tourists who are aware of the premium certain brands command in their home country. The shopping center’s vision is now, as the manager put it, “for Clarks Village to be a ‘must do’ destination for international visitors to the West Country.”6 In an interesting twist, Chinese tourists are now flocking to Clarks Shoe Museum and are an increasingly powerful force behind the prosperity of Street.7 “Clarks shoes are a phenomenon in China; their quality and design are famous,” says Stephanie Cheng, managing director of London-based China Holidays Ltd.8

TREND BREAK

Two decades ago, the notion of shoppers from China, or any emerging market, driving economic activity in Street—or anywhere else—would have seemed preposterous. For centuries, less than 1 percent of the world’s population enjoyed sufficient income to spend it on anything beyond basic daily needs. As recently as 1990, 43 percent of the population in the developing world lived in extreme poverty, earning less than $1.25 per day, and only one in five people on the planet earned more than $10 a day—the level of income at which households reach the “consuming class” threshold and can afford to buy discretionary items.9 The vast majority of those consumers were in advanced economies in North America, Western Europe, and Japan.

Over the past two decades, the amplifying forces of industrialization, technology, and the urbanization of emerging economies have driven incomes higher for billions of people, lifting 700 million out of poverty and adding 1.2 billion new members to the consuming class.10 From a societal perspective, this level of poverty eradication prevents more deaths from poverty-related diseases and hunger than the lives saved per year through eradication of smallpox, often hailed as the greatest health-care achievement of the twentieth century.11 From a market perspective, it means the center of the global consuming class, with huge spending power, is shifting east and south. By 2025, we expect the consumer class to add another 1.8 billion people and total 4.2 billion. Much has been made about the world’s population crossing the 7 billion threshold in 2012. But the 3 billion additional members of the world’s consuming class added in just thirty-five years is a far more significant milestone.12 That’s as many new consumers added as there were people on the planet in the mid-1960s.13 As Sanjeev Sanyal, Deutsche Bank’s global strategist, notes, “The real story for the next two decades will be emerging economies’ shift to middle-class status. Although other emerging regions will undergo a similar shift, Asia will dominate this transformation.”14

Three billion people joining the consuming class between 1990–2025

1. Historical values for 1820 through 1990 estimated by Homi Kharas; 2010 and 2025 estimates by McKinsey Global Institute.

2. Defined as people with daily disposable income above $10 at purchasing power parity (PPP). Population below consuming class defined as individuals with disposable income below $10 at PPP.

SOURCE: Homi Kharas; Angus Maddison; McKinsey Global Institute Cityscope database

Incomes have been rising, and the consumer class has been expanding, for some years. But we have reached a tipping point where the spending of a new generation of consumers in emerging economies has become an overwhelming force.

By 2030, almost six hundred million people with annual income greater than $20,000 a year will live in emerging markets—roughly 60 percent of the global total. They will account for an even higher proportion of spending in categories such as electronics and automobiles. Seven emerging markets—China, India, Brazil, Mexico, Russia, Turkey, and Indonesia—will be fueling almost half of all global GDP growth over the coming decade.15

The billion-plus populations of China and India are at the heart of the phenomenon. Technological progress, in which millions of people in emerging economies now have access to the Internet and mobile communications, is fueling consumption. In India, discretionary spending jumped from 35 percent of average household consumption in 1985 to 52 percent in 2005, and it looks set to hit 70 percent by 2025.16 In China, a new generation of consumers born after the mid-1980s—Generation 2 or G2—will be crucial for the economy. While their parents lived through many years of shortages and were primarily concerned with building economic security, G2 consumers have been raised in relative material abundance. They are confident, willing to pay a premium for the best products, eager to experience new technology, and heavily reliant on the Internet for price information.

To illustrate the strength of the consumption wave, China should overtake the United States in terms of spending on consumer electronics and smart phones by 2022. The speed of change is extraordinary. In 2007, ten million flat-screen televisions were sold in China. Five years later, sales were fifty million units—more than were sold that year in the United States and Canada combined.17 And it’s not just basic products: the Chinese are moving upmarket. China has already overtaken the United States as the world’s largest market for all car sales, and in 2016, China will outstrip the United States in sales of premium cars.18 Tesla Motors is already shipping its expensive electric sports cars to China.19 Trading up is becoming an ever more important part of China’s consumer story. In some luxury goods categories, emerging-market consumers are the fastest-growing segment of the market. That explains why L’Occitane, the privately held French beauty products company, floated its 2010 IPO in Hong Kong and not on the Euronext in Paris.20

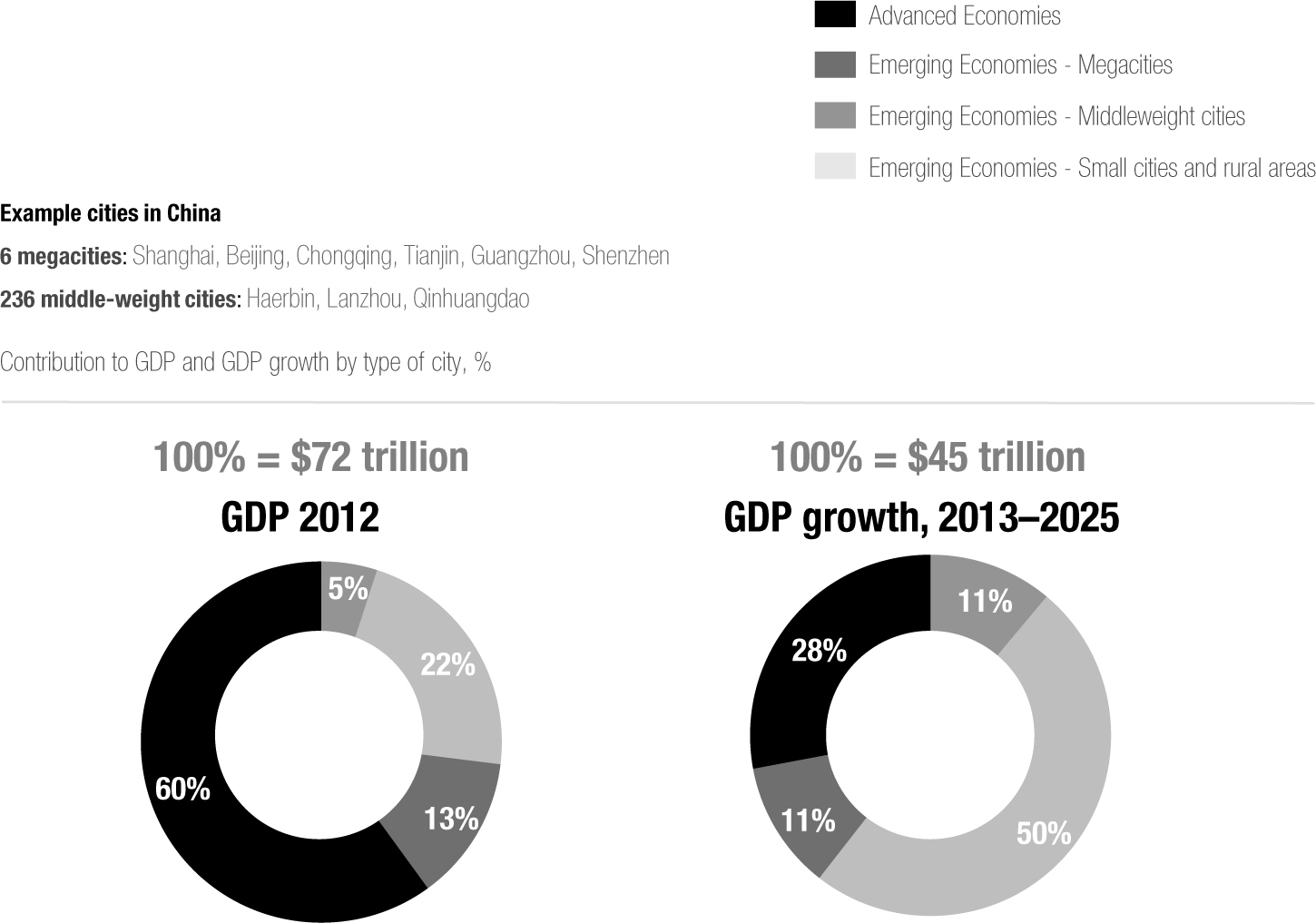

Many of these new consumers will come from relatively unknown “Middleweight” cities in emerging markets

1 Megacities are defined as metropolitan areas with ten million or more inhabitants. Middleweights are cities with populations of between 150,000 and ten million inhabitants.

2 Real exchange rate (RER) for 2007 is the market exchange rate. RER for 2025 was predicted from differences in the per capita GDP growth rates of countries relative to the United States.

SOURCE: McKinsey Global Institute Cityscope database

Although there will be turbulence and periods during which the rate of economic growth of emerging markets may slow, we expect these trends to continue at least through 2025. In fact, even under pessimistic scenarios, we believe the emerging economies will likely continue outperforming developed economies. The annual consumption in emerging markets will reach $30 trillion by 2025.21 Some 440 emerging-market cities, including 20 megacities (population over ten million), will account for nearly 50 percent of the additional GDP growth between now and 2025.22

TECHNOLOGY WILL BENEFIT CONSUMERS

The spreading reach of the Internet also means that these new consumers will be plugged in and online. China already has more than six hundred million Internet users, equivalent to 20 percent of the global Internet population.23 More than a quarter of Brazilians using the Internet have opened Twitter accounts, making Brazil the world’s second-most enthusiastic tweeting nation.24 In India, consumers are leapfrogging the traditional technology trajectory. Landlines may be slow to reach remote villages, but more than nine hundred million Indians are mobile users.25 A desire to cater to the nearly 300 million Indians who are illiterate is spurring the development of voice-activated websites and services.26 Of Facebook’s 100 million users in India, more than 80 percent access their accounts through mobile devices.27

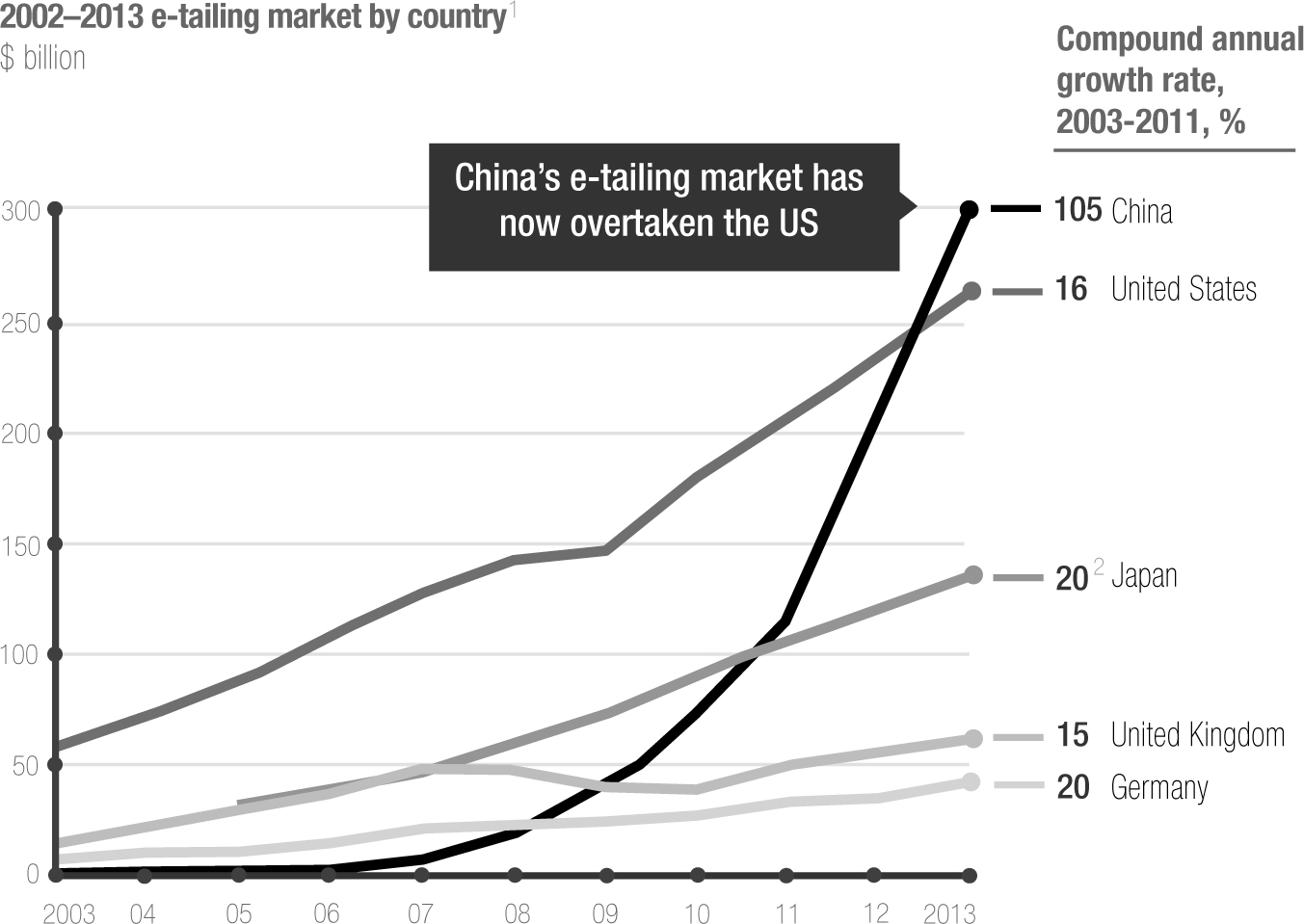

In 2013, we witnessed two firsts for the Chinese e-commerce market. First, China’s e-tail market, which has been growing at a stunning compound annual rate of more than 100 percent since 2003, overtook the United States to become the world’s largest, with an estimated $300 billion in sales.28 By 2020, China’s e-commerce market could be as big as today’s markets in the United States, Japan, the United Kingdom, Germany, and France combined. Second, as we noted in the introduction, on November 11, 2014—Singles Day in China—Alibaba recorded sales of more than $9.3 billion, a record for a single day anywhere in the world, and more than triple the combined online purchase of US consumers during Black Friday and Cyber Monday in 2013.

In a phenomenon that is often underplayed and challenging to quantify, the consuming classes will also receive most of the value created by most of the new disruptive technologies. Free information, apps, and online services, lower-cost goods, greater access to information, and lowered barriers to communications will enrich the lives of billions. Unfortunately, this is not picked up in the way we measure GDP. Established companies, on the other hand, may find themselves temporarily shortchanged and unable to monetize the newly created consumer surplus. Technology disruption has historically represented as a negative-sum game for the disruptor and the disrupted. Think of Apple’s iTunes and the rise of digital music sales: following the introduction of iTunes in 2003, physical music sales in the United States fell from $11.8 billion to $7.1 billion in 2012, adjusted for inflation; industry revenues have fallen by more than half. The consumer receives the benefit.29

HOW TO ADAPT

We are dealing with very large numbers. And it is easy to be overwhelmed by the single overriding growth story. But the $30 trillion consumption opportunity is as granular as it is vast. New-growth markets come in a range of sizes and development stages, and new customers span a multitude of ethnic and cultural backgrounds. Their tastes and preferences are constantly evolving, in many cases accelerated by the mutually amplifying forces of interconnectivity and technology. As these new markets grow, they are also fragmenting into many segments with a proliferation of product varieties, price points, and marketing and distribution channels.

Technology is opening up new routes to these consumers

1 Excluding online travel.

2 Japan’s compound annual growth rate covers 2005–2013.

SOURCE: Euromonitor; Forrester; US Census Bureau; Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry; iResearch; McKinsey Global Institute analysis

Even for the most seasoned executives, the sheer speed and scale of change can be daunting, and many continue to be held hostage to their existing strategy bias. The success stories are plentiful: we’ve been hearing for years about emerging-market “insiders” like Unilever, which has made great inroads in the Indian consumer market, and SAB Miller, a South African firm that grew into one of the largest beer companies. But we’ve seen a great number of failures as well. Yahoo and Amazon have both stubbed their toes badly in China. India has proved a formidable challenge for many otherwise successful multinationals.

To succeed in this emerging climate, business leaders have to reset their intuition. Under the old model of global expansion, big firms that had conquered their home markets could thrive by methodically planting their flags in fertile foreign soil, all directed from a headquarters thousands of miles away. But winning consumers in these new high-growth markets requires a radical reallocation of resources, a smart shift in capabilities, and a rethinking of multiple aspects of operations. New emerging markets are not vast homogenous entities that will readily accept products and services transplanted whole from developed markets. Nor are these new consumers simply looking for watered-down, low-price versions of existing products. As executives navigate these new opportunities, they also don’t have the luxury of waiting and watching. Growth is often explosive in these emerging markets, with sudden bursts of 70 to 100 percent expansion possible in certain product categories. Leaders must learn to reallocate resources to these new-growth markets with speed and at scale, while managing risk and diversity at an entirely new level.

The companies that will succeed in the race for these extraordinarily diverse emerging markets will most likely share four traits.

• They will think of the next opportunity in terms of cities and urban clusters, not regions or countries, and reallocate their capital and talent accordingly.

• They will customize and price products to meet local tastes and needs and will build faster, lower-cost supply chains and innovative business models in order to be cost competitive and deliver price points across a broad spectrum.

• They will design and control multichannel routes to market and rethink their brand and marketing and sales strategies.

• They will overhaul organizational structures, talent strategy, and operating practices to reflect the new shift.

Focus on Cities and Urban Clusters, Not Regions or Countries

Global consumption is experiencing an unprecedented shift in power toward emerging-market cities. The continued rise of megacities—familiar entities with populations of ten million or more, such as Shanghai, São Paulo, and Moscow—is driving this trend. But the truly dramatic consumption growth will come from middleweight cities such as Luanda, Harbin, Puebla, and Kumasi, four hundred or so of which will generate the GDP equivalent to the entire US economy by 2025.30 In China, the shift in the weight of consuming households from the megacities on the east coast to interior middleweight cities (populations of between two hundred thousand and ten million people) is already visible. In 2002, only 13 percent of China’s urban middle class lived inland, with the remaining 87 percent living in coastal areas; that figure is set to rise to nearly 40 percent by 2022.31

The consumer landscape in these new-growth cities remains incredibly diverse. India embraces about twenty official languages, hundreds of dialects, and four major religious traditions. The residents of Africa’s fifty-three countries speak an estimated 2,000 languages and dialects. Even cities close to each other in the same country can be very different.32

Many global companies, for example, make the mistake of conducting Brazilian consumer research in São Paulo, not realizing that the cosmopolitan city has more in common culturally with New York, 4,771 miles away, than with Curitiba, the capital of Parana state (population 1.7 million), which is just 210 miles away.

Take the southern Chinese cities of Guangzhou and Shenzhen, which are roughly the same size and only one hundred kilometers apart. The majority of people living in Guangzhou speak Cantonese. In Shenzhen, Mandarin-speaking migrants make up more than 80 percent of the population. These differences have deep business implications.

Chinese premium auto buyers from coastal cities like Hangzhou and Wenzhou, who have long been exposed to international brands, are looking for cars that reflect their social status. They react favorably to advertising that appeals to this impulse. But in interior cities like Taiyuan and Xi’an, drivers rely heavily on word-of-mouth and in-store experience to reassure themselves that cars provide what brands advertise.33

Given the granularity of the $30-trillion opportunity and the rapid urbanization of these economies, the answer to “where next?” will be found in urban clusters and cities. In consumer goods, companies that target older generations will consider Shanghai and Beijing among the most attractive markets. By contrast, companies that sell baby food will find more than half of the top cities that are experiencing a baby boom and whose households have sufficient income to buy their products are in Africa. In midmarket apparel, nine out of the top ten growth cities, including Chongqing, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, will be in emerging markets. But in luxury apparel, developed-market cities will continue to fuel growth, with only four emerging-market cities—Saint Petersburg, Moscow, Seoul, and Singapore—among the top ten.34

Rather than competing in the cutthroat retail markets in emerging-market megacities, many executives will find better growth opportunities in the rapidly growing middleweight cities. In Brazil, the GDP of São Paulo state is larger than that of the entire country of Argentina. Competitive intensity is high and retail margins thin as a result. For new entrants to Brazil, the populous but historically poor northeast of the country, where boomtowns like Salvador are expected to grow 2.4-fold by 2015, may offer better prospects, even if setting up operations is more difficult.35 This is not exactly a new idea. Walmart grew into America’s largest retailer from the inside of the country out, finding underserved towns and avoiding highly competitive metropolitan markets.

Anticipating when to take action will matter as much as choosing where to compete. Growth in emerging markets is rarely linear. The demand for a particular product or category of products typically follows an S-curve trajectory. Consumption takes off and enters an explosive growth “hot zone” once consumers have enough money to buy a product. At higher GDP-per-capita income levels, markets tend to become more saturated and then enter a slower-growth “chill out” zone. Take Nigeria’s beverage market as an example. While cities such as Warri, Benin City, and Port Harcourt have already entered the beverage hot zone, larger cities like Lagos, Ibadan, and Abuja are still walking toward the takeoff point. By understanding the dynamics of the product category and the local marketplace, companies can time market entry—ideally right before a category enters the hot zone—and benefit from the fastest growth stage in each city.36

Understanding and coping with the trade-offs between growth and costs is a complex business. One way to start is by segmenting and clustering the new-growth-market cities similarly to the way you segment consumers. Multiple smaller cities with common demographic, socioeconomic, and cultural characteristics, as well as infrastructure and retail landscape, could form an urban cluster and provide scale efficiencies across all aspects of operations. You can then orchestrate your expansion cluster by cluster, focusing on “going deep” before “going wide.”

Think Locally, Act Globally

On its own, understanding where and when to focus isn’t sufficient. To ensure relevance and achieve scale in the new market, you must decide how and how much you need to tailor your products or services.

As these new consumers emerge over the next decade, their needs, preferences, and consumption behavior will vary vastly across product categories, geographies, and segments. Although some trends travel the globe, there is no such thing as a “global consumer.” LG refrigerators have larger vegetable compartments in India than in Brazil, where freezer compartments are larger. Nestlé instant coffee is sweeter in China than in most other markets.37

A deep understanding of consumer needs and preferences and of smart segmentation will continue to differentiate leaders from the pack. And companies will increasingly need to craft more nuanced product strategies that balance scale and local relevance. In recent years, many companies have assimilated a polarized caricature of emerging-market customers—the free-spending, luxury-loving nouveaux riches at the high end, arrayed against the bottom of the pyramid. But given the increasing proliferation of customer needs and rising sophistication of data and analytics, these are neither the only strategic alternatives nor necessarily the most apt.

Seek, rather, to understand markets on their own terms. A careful understanding of local tastes and flavor preferences propelled consumer goods companies such as Frito-Lay in India and Tingyi and Wrigley in China to meteoric growth.

• Frito-Lay has captured more than 40 percent of India’s branded snacks market since entering in 1990. How? Rather than tailoring its global, American-heritage brands such as Lay’s potato chips to local tastes, the company created Kurkure, inspired by traditional Indian-style street food and Western-style potato chips. The product, which relies on simple, authentic ingredients used in any Indian kitchen, is now sold in countries such as South Africa, Pakistan, and Kenya.38

• Tingyi, a start-up founded by two Taiwanese brothers in China, became China’s leading food and beverage vendor after it used local designers to shape its entire instant noodle product category, creating new flavors and launching brands such as Kangshifu (“Master Kong”) and low-cost brands such as Fu Man Duo (“full of luck”). Tingyi’s Master Kong brand is the most popular brand in China.39 With its portfolio of food and beverage products, Tingyi generated revenue of $10.9 billion in 2013.40

• Wrigley, which has built its market share of the Chinese gum market to 40 percent, succeeded by tailoring its gum flavors to suit local consumer preferences and by investing in consumer education to emphasize chewing gum’s health benefits.41

Pricing is another key decision in determining how much to customize. The amount a company is able (or willing) to charge its customers and relative positioning compared to its peers can have interesting nuances from market to market. In Brazil, Diageo capitalized on its understanding of affluent costumers when pricing its Johnnie Walker product. The company recognized that in Brazil retail price was a quality differentiator and that the spirits markets enjoyed lower price elasticity compared with other markets. Subsequently, Diageo repositioned Johnnie Walker into a higher premium category, and Brazil is now one of its most important markets.

For many players, however, the only way to be successful locally means rethinking their existing cost structures. Emerging-market companies have proven to be formidable competitors on cost. As we will allude to in Chapter 9, emerging-market players, particularly in capital-intensive industries, are increasingly capital light and inventive. That elevates the need for developed-market companies to innovate and localize research and product design, rethink supply-chain management and financing, and, in some cases, partner up to gain easier access to existing infrastructure.

• In India, General Electric has devised an electrocardiograph machine that can be sold profitably for $1,500, less than one-fifth the price of traditional electrocardiograph monitors in advanced markets. The new design not only helped General Electric make inroads in the rapidly growing Indian market, but also helped it figure out how to create a monitor it could sell for $2,500 in developed markets. Learning from this experience, GE now develops more than 25 percent of its new health-care products in India—with explicit intentions to deploy them both in emerging and advanced economies.42

• South Korea’s LG Electronics is another example of successful innovation in the Indian market. LG had struggled in India until the 1990s, when a change in foreign-investment rules enabled it to heavily invest in local R&D facilities and in top-notch Indian design and engineering talent. Local developers knew that Indians used their televisions to listen to music. So LG introduced new models with better speakers, while swapping flat-panel displays for cathode tubes in order to keep prices down. Today, LG’s product innovation center in Bangalore is the company’s largest outside South Korea, and LG has become India’s market leader in televisions, refrigerators, air conditioners, and washing machines.43

• In China’s ready-to-drink coffee market, Nestlé has been able to reduce prices by 30 percent by establishing a local low-cost supply base in Yunnan and relying almost entirely on Chinese sources.44

• VF Corporation, one of the ten largest fashion companies in the world, redesigned the way it manages its supply chains in response to an increasingly expanding footprint. Relying on an integrated IT system, VF designed “The Third Way,” in which different brands in its portfolio aggregate their sourcing needs in order to create economies of scale. The company also works closely with manufacturers so that it can produce many different branded products in a single factory. From the mid-to-late 2000s, doing so allowed VF to reduce the production cost of jeans and other apparel by between 5 and 10 percent.45

• As Tingyi built its business in China, it set up new plants in every province, including rural areas like Qinghai, Sichuan, and Henan provinces. The strategy was to be local at the province level in order to take advantage of low-priced inputs, labor, and tax benefits, and to adapt product, sales, and distribution strategies to on-the-ground realities.

Learn to Market and Sell Through Multiple Channels

Businesses must meet customers where they are, where they prefer to shop, and where they prefer to make decisions. For example, our research underscores the importance of in-store interaction in emerging markets. In China, nearly half of consumers make purchasing decisions in-store, compared with just one-quarter in the United States. The in-store part of the consumer decision journey in emerging markets tends to be longer and more meaningful. Chinese consumers take two months and four store visits before making decisions about big-ticket consumer electronics.46

However, controlling that consumer in-store experience represents an enormous challenge for many executives. The Walmart in Optics Valley Center in Wuhan, China, would be immediately recognizable to any Westerner, with its neatly organized and brightly lit aisles featuring clothes, diapers, electronics, snack foods, and household goods—plus the tub of croaking bullfrogs in the food section. But elsewhere, the retail landscape can be unfamiliar and bewildering. In markets such as India and Indonesia, retailing is highly fragmented, with small proprietors accounting for over 80 percent of sales. By comparison, in markets such as China and Mexico, modern trade already makes up over half of all sales. You must therefore prepare to simultaneously deal with global retailers, such as Carrefour and Walmart, and with local champions, such as CR Vanguard in China and Big Bazaar in India—as well as with a fragmented array of small proprietors.47

Many global companies get things wrong by relying on the key-account techniques and sales teams of third-party distributors that worked in home markets. As a result, multinationals should rethink their approach in these new locations and be prepared to build much larger in-house sales operations, segment sales outlets, and devise precise routines and checklists for monitoring the quality of the in-store experience.

Coca-Cola, which has been operating in emerging markets for decades, goes to great lengths in emerging markets to analyze and segment the range of retail outlets. For each category, it generates a “picture of success”—a detailed description of what the outlet should look like and how it should display, promote, and price Coke products. The company uses a direct-sales model for high-priority outlets and relies on distributors and wholesalers when that model isn’t cost effective. Coca-Cola then scrutinizes everything from service levels and delivery frequencies to where the coolers are positioned in the store. In Africa, Coca-Cola has built a network of 3,200 microdistributors by recruiting thousands of small entrepreneurs who use pushcarts and bicycles to deliver Coke products to “last mile” outlets. In China, where the logistics infrastructure is more developed, Coca-Cola sells directly to over 40 percent of its two million retail outlets and monitors execution in 60 to 70 percent of all its retail outlets through regular visits by Coca-Cola salespeople and merchandisers. Coca-Cola is not an isolated example. In markets like India, Brazil, and Africa, long-established firms such as Unilever and Nestlé use everything from handcarts to bicycle carts to floating barges to get their products to consumers.48

In addition to distribution, companies must figure out how to position their brands and market in these new territories. Emerging-market consumers tend to have a smaller number of brands they initially consider and are less likely to switch to a new brand later. Our recent research indicates that Chinese consumers initially consider an average of three brands and purchase one of them about 60 percent of the time. The comparable figures for European and American consumers are four brands, with a purchase rate of 30 to 40 percent.49

The smaller and more important initial consideration set favors brands with high visibility and an aura of trust. In order to achieve awareness and consideration, testing of messages and geographically focused campaigns will be key. Locally focused campaigns tend to accelerate network effects and make it easier for new players to generate positive word-of-mouth, which is a critical prerequisite for emerging-market success. After all, many consumers reside in countries where trust in the media is at a relatively low level. For instance, in China, positive recommendations from friends and family are nearly twice as important as they are for consumers in the United States or Britain. In Egypt, the importance is nearly three times higher.50

You will need to rely on customer insight and local consumer testing to decide how much you need to adapt your brands and messaging. Acer’s slogan “simplify my life” worked well with electronics customers in Taiwan. But when Acer China tested it in mainland China, the message didn’t resonate. In focus groups, it became clear that Acer’s intended message of simplicity and value was raising suspicion about the reliability and durability of the company’s products. A change in Acer’s message to stress reliability rather than simplicity and productivity helped the company to build a more relevant and trusted brand and to ultimately double its market share in less than two years.51

Adapt Your Organization and Talent Strategy

As global players grow bigger and more diverse, the costs of coping with complexity rise sharply. In a series of surveys and structured interviews with more than three hundred executives at seventeen of the world’s leading multinationals, less than 40 percent of the executives said they were better than their local counterparts at understanding the operating environment and customers’ needs. Many high-performing multinationals also suffered from a “globalization penalty,” scoring lower than more geographically focused companies on key dimensions of organizational health. Managing tension between local adaptation and global complexity, setting a shared vision among employees, encouraging innovation, and building government and community relationships were among the commonly cited culprits.52

In order to increase agility in pursuing new opportunities, to maximize chances for success, and to reduce the globalization penalty, you may need to rethink your organizational structures and processes. For a company with most of its growth potential in emerging markets, does it still make sense for the board to be dominated by English speakers and even for the headquarters to be located in Europe or North America? Furthermore, would it be unthinkable to have the general manager of the São Paulo cluster hold a similar rank as the corporate head of the European market?

Increasingly, global players have started to move their core activities closer to priority markets. But “stickiness bias” toward existing strategy and resource allocation prevents many from acting in a timely manner. ABB, IBM, and General Electric are recent examples of organizations tilting toward emerging markets.

• ABB, the Swiss engineering giant, moved the global base of its robotics business from Detroit to Shanghai to pursue its “designed in China, made in China” strategy.53

• IBM, which gets 64 percent of its sales outside the United States, now runs human resources from Manila, accounting from Kuala Lumpur, procurement from Shenzhen, and customer service from Brisbane for its Japan business.54

• General Electric, which reaps more than half its revenues from overseas, in 2011 moved its X-ray business from Wisconsin to Beijing.55

“In some ways, capital is easier to reallocate than people—you can sit in Brussels, look at the annual capital flows of the different businesses, and act accordingly,” said Jean-Pierre Clamadieu, chief executive officer of Solvay, the Belgian chemicals company. “With people, there is always a tendency to manage in geographic or business ‘silos.’ That’s why we have recently established a new principle: that the top 300 people in the group are corporate assets.”56 In other words, the company’s leading employees will be rotated across global operations based on local needs and growth rather than remaining at the company’s headquarters.

In addition to rethinking organizational structures, companies need to decide on the right level of autonomy between headquarters and new markets. Many firms still operate with cumbersome reporting lines, in which international divisions oversee country-specific fiefdoms that don’t collaborate and sometimes operate in their own languages, frustrating communication. This model often leaves C-level executives at headquarters too removed to understand the speed of change and the scale of the opportunity in emerging markets.

Our observation, however, is that companies experience success when they are able to break away from the “investing in a market” mentality and give local leaders sufficient freedom to chart their own path. When LG Electronics set about increasing its market share in India by building a local subsidiary, expatriate Korean managers acted only as mentors or advisors, without the authority to make decisions.57 Tingyi’s success in China stemmed in part from its strategy of giving local management full authority to make decisions and to tailor and develop new products that cater to the needs of Chinese consumers.

Attracting, developing, and retaining top talent to lead these new-growth markets is another crucial element of a successful emerging-market strategy. Based on a recent survey of leading global companies, only 2 percent of their top two hundred employees hail from key Asian emerging markets.58 This is in part a reflection of a scarcity of supply, but also a result of stickiness bias to existing resource allocation or unclear “employer brand” proposition in new territories. Some global firms have tackled the issue by developing clear talent propositions that differentiate them from local competitors. In South Korea, L’Oréal became the top choice for female sales and marketing talent by creating greater opportunities for brand managers and by improving working hours and child-care infrastructure. In India, Unilever has attracted top Indian talent by creating a global leadership program that includes rotation and permanent placement programs.59

![]()

The rise of a new class of consumers around the world is imposing a tough new set of requirements on established companies. Advantages in a home market can’t be easily replicated or taken for granted in far-flung markets. But the opportunities are too large to ignore. As impressive as recent growth has been, the process is just beginning. With each passing day, more people are moving from rural areas to cities, more people are going online and plugging in, and more people are joining the ranks of the world’s consumers. As a result, more organizations may find, as Clarks Village did, that the world is beating a new, entirely unpredicted path to their doorstep—at the same time that consumers in markets previously considered closed off are acquiring a taste for the types of products they make. Smart companies that systematically rethink the way they approach, manage, and serve all the world’s promising markets can figure out how to meet customers where they are—and where they will be.