Building a coop can be great fun. In this sort of project, the planning and design stage is just as fun — and as important — as the hammering and sawing. You need to address several preliminary questions before you strike the first nail. What sort of protection do your chickens need from the weather? How big does the coop need to be? Do you want the coop to be a fancy fairy-castle affair or a plain and sturdy pen? What type and quantities of supplies will you need? Do you have a place for the coop in your yard where it will comply with any existing building setback requirements? Building a chicken coop and keeping a small flock of chickens in your garden will be easy once you have answers to these questions.

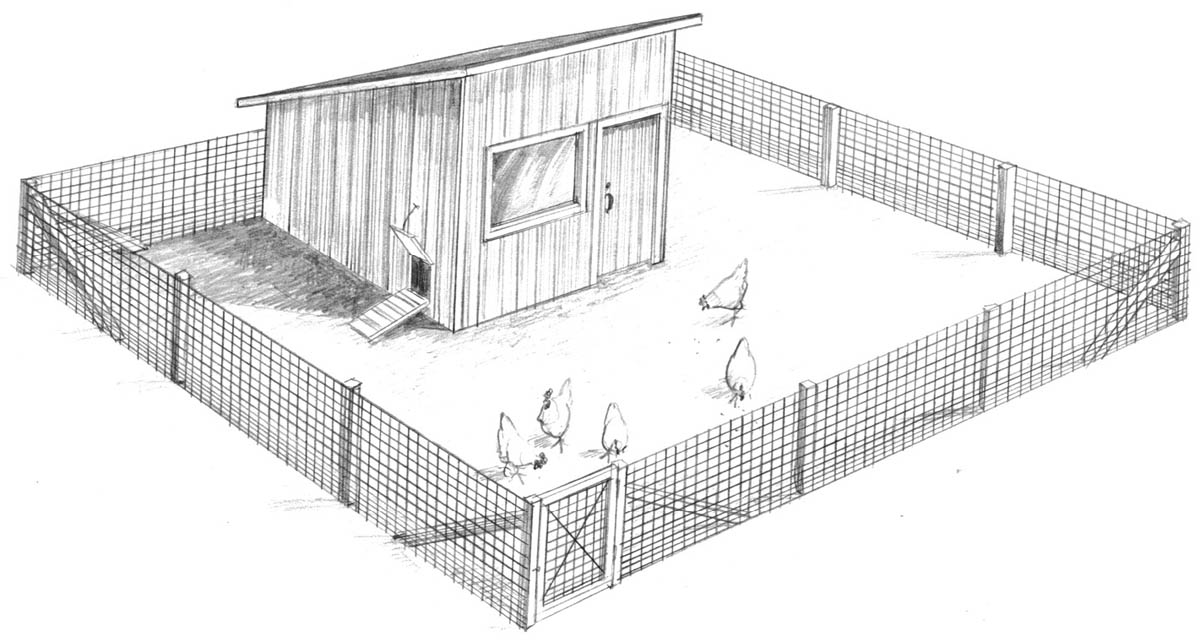

The term coop refers to the entire hen habitat, which includes a chicken run and a henhouse. The chicken run is the outdoor portion of the coop, enclosed by chicken wire. The floor of the run is usually dirt and should be covered with gravel or absorbent materials, such as straw and cedar shavings. It can be enclosed with a roof or left open to the elements. Obviously, the chicken run and the chickens in it will stay cleaner and cooler if the run is roofed.

What do chickens do in the run? They hang out. Think of the run as a poultry living room or a chicken bar and grill. They eat and drink in the run, walk around, dig in the dirt, cluck among themselves. When they wake up in the morning, chickens head right out the hole in the henhouse door to the run to do the same thing they did the day before. And they love it!

The henhouse is a fully enclosed wood structure inside or adjoining the chicken run. Your hens sleep in the henhouse at night and lay eggs in it during the day. A small doorway in the henhouse opens into the chicken run. The floor of the henhouse should be raised off the ground on cement blocks or a solid cement pad.

Inside the henhouse, on opposite walls, are one or more perches and nest boxes. The perch is where the hens sleep, or roost, at night. Nest boxes are small, private cubicles where hens lay their eggs. Both perches and nest boxes should be firmly secured to the henhouse walls and elevated some distance from the floor.

The coop is bounded by a sturdy wire fence. The henhouse, located within the coop, is where the chickens sleep and lay eggs.

Chicken coop refers to the entire hen habitat, including a chicken run and a henhouse.

Chickens play in the chicken run and lay eggs and sleep in the henhouse.

How much space do chickens need? Per chicken, no less than 2 square feet (0.2 m2) in the henhouse and 4 square feet (0.4 m2) in the run. Halve those figures for bantams. A coop that is 10' x 4' x 5' (305 x 112 x 152 cm) with a henhouse that is 4' x 4' x 5' (122 x 122 x 152 cm) is a vast, comfortable estate for three chickens. In my neighborhood, I’ve seen smaller habitats that work, though they don’t allow any extra wing room for the chickens. If you plan to keep your chickens in a smaller coop, you’ll need to let them roam free in the garden a few times each week. They’ll be a lot happier and healthier if they can stretch their legs from time to time.

If you have the room, give the hens extra space in the coop. If you don’t give your chickens enough room, they will get anxious and start to stress out. Chicken anxiety creates coop chaos by manifesting in bad habits and compulsions, like pecking and biting one another, feather pulling, eating their own eggs, and cannibalism. For a happier place, give chickens their space! Then again, don’t be impetuously motivated and build a coop big enough for 50 hens. Keep the coop at a reasonable scale for your lot and neighborhood. After all, we’re talking about housing just a few chickens.

Another good idea is to make the coop and henhouse tall enough that you can walk in them. Crawling into your coop and henhouse to clean them is no picnic, no matter how much you like your chickens. Also, feeding, watering, and egg collection are easier to manage if you can walk inside the henhouse. You may want to install two doors into the henhouse — a chicken-sized door leading out into the run and a human-sized door at the back allowing you to enter the henhouse without having to walk through the run.

I recommend enclosing the coop completely, including a roof. By entirely enclosing the chicken coop, you protect your hens from predators like stray dogs, cats, raccoons, and occasional fly-by raptors. The roof can be made of netting, leaving the run open to the elements, or of a solid surface, such as plywood. A solid roof (made of plywood or tin, for example) will provide shade and keep rain off the chickens when they are out digging on a rainy, winter day.

If you’re keeping bantam hens, definitely enclose the chicken run with some kind of roof; bantams have no problem catapulting themselves over a 6-foot (1.8 m) fence. Heavy breed hens, like the Girls, get only a few feet of altitude when they try to fly (but they do get a standing ovation for trying).

The climate where you live will influence not only what breed of hens you get (see chapter 6) but also what kind of coop you build.

In colder climates, the henhouse should be equipped with a heat lamp for cold nights. It also should employ double-walled construction for additional insulation against the elements.

In warmer climates, the coop should encompass plenty of shaded areas. The henhouse should have windows that you can open on hot days for additional ventilation. You may want to design the henhouse roof so that it’s hinged to the frame instead of permanently affixed; you can raise the roof and prop it open for extra ventilation on especially hot, humid days. Another special option for a warm-weather coop might be an automatic watering system that ensures a continuous supply of fluids on the hottest days. If you’re keeping large hens, install a box fan in the coop to help keep your big girls cool. How do you know if your chickens are feeling too hot? Well, if you’re feeling too hot, chances are the chickens are, too.

A compact, warm-weather coop can be designed to be mobile. While mobile coops are most practical on larger parcels, they can also be used by suburban gardeners. The idea is to put the coop and chickens in one area, let them naturally compost and till the soil for a few weeks, then move the birds to another spot where the soil needs tilling and amending. This way, you (forgive the pun) get two birds in one shot — housing for your flock and year-round direct-soil composting.

A mobile chicken pen allows you to have your chickens “graze” different sections of your yard, tilling and composting the soil as they go.

Location, location, location is the guiding mantra for real estate, no matter what type of building — a simple restored cottage, a sprawling Victorian mansion, or a chicken coop. In the long run, location matters much more than appearance.

If local code specifies certain setback restrictions, put these into play in your yard. You know about how large the coop needs to be (see How Big?). Eliminate from the list of possible sites those that won’t accommodate the coop without exceeding the setback boundaries. Depending on the code where you live, the boundary may be related to the nearest door, window, or property line of neighboring residents.

Common sense and courtesy dictate that you should locate the coop site as far away as you can from your windows and your neighbors’ windows. By practicing coop etiquette in the planning stages, you prevent the likelihood that the scent of summer-warmed chicken droppings will waft into any nearby windows — including yours. As an added preventive measure for my own coop, I planted jasmine and honeysuckle on one side of the henhouse and run. Their lovely and scented blossoms upstage any unlikely possibility of a whiff of chicken coop on a breezy day.

While the chicken coop should be properly ventilated to avoid a build-up of moisture, the hen-house needs to be relatively draft-free so chickens don’t catch cold in the winter.

Make sure the proposed chicken run gets adequate amounts of both sun and shade, so if you’re not home during the day in summer, your chickens won’t roast inside their coop. Also make sure that the proposed coop is not sited on ground that’s lower than the rest of the yard. Otherwise, be ready to provide your hens with snorkeling equipment during rainy weather.

When you have settled on the most likely coop site, envision where you will put the door leading into the coop, making sure it will have plenty of room to swing out. You must give yourself access to the nest boxes (where hens lay their eggs), especially if you are building a short coop you can’t enter standing up.

Once you find the right site in your yard, use string or spray paint to outline the general size of the coop area on the ground. Double-check to make sure the run has enough room for each hen. Check the paint or string boundaries once and then again. If you are confident that the coop is the right size, is in the right place, and falls within setback regulations, then you’re ready to proceed with construction.

Chickens don’t care what their coop and henhouse look like, so long as their living arrangements are clean, dry, warm, easy to clean, and adequately ventilated. As you imagine your future coop, begin in your mind’s eye with a basic structure made from wood — a shed, an A-frame cabin, or an enclosed lean-to. Then let your imagination run free, like a chicken in an unfenced clover pasture.

Supplies and equipment for a simple coop and henhouse can run as low as $100. A larger, roomier coop, like the one I built, might cost a few hundred dollars. All supplies are readily available at any well-stocked hardware store.

To protect the floor of your henhouse from ground moisture, which leads to rot, you must keep it raised off the ground. Setting the henhouse on cement blocks will work. However, setting the house on a solid cement slab is better, because it insulates the birds from drafts and prevents incursions from tunneling rats. A cement slab can also serve as the actual floor of the henhouse; it’s easy to scrape and sweep.

If you decide to go with the cement blocks, make sure that the floor of the henhouse, when set on the blocks, is level. You may have to dig out around the blocks and fiddle with their placement to achieve a level footing.

If you choose the cement slab instead, you can pour it yourself (if you know how) or have a local contractor do it for you.

Poultry Tribune, circa 1940.

The run can be constructed of chicken wire, chain-link fencing, or heavy-duty netting — anything that secures the hens away from outside dangers and predators, such as cars and neighborhood cats.

If you’ve ever fenced in a garden, you know that it’s tiring, sweaty work. In the case of the chicken run, you’ll need to make sure that the work is carefully done and the resulting fencing sturdy — you wouldn’t want an animal throwing itself at an unsuspecting chicken to hit the netting and knock it down. To be installed properly, chain-link fencing generally requires the expertise of a professional. A fence of chicken wire or netting can be a do-it-yourself project. However, if you’re uncertain of your carpentry skills, you may wish to have a contractor do the job for you. If you’re willing to brave the challenge, read on.

The fencing will be supported by a series of anchor posts spaced 3 to 4 feet (0.9–1.2 m) apart. The anchor posts will also support the roof rafters, so they must be placed symmetrically — each anchor post must have a corresponding post opposite it. Most of the coops I’ve seen use 2 x 4s as anchor posts. Cut the posts to the desired height, taking into account that they’ll be set 8 to 12 inches (20–31 cm) in the ground. You may wish to have the posts on one side be 6 to 12 inches (15–31 cm) taller than the posts on the opposite side, with the posts on the two remaining sides (if any) sloping from one end to the other. The difference in height will cause the roof, when fit on the rafters, to slope, forcing rainwater to drain off in the direction of the lower side.

Use a post-hole digger (available for rent from most garden centers) to dig a hole for each post. Prepare a batch of quick-drying cement. Place a post in its hole and pour the cement into the hole. Hold a level along the side of the 2 x 4 to ensure that it is upright, and hold the post steady in place until the cement sets. (This job is easier done by two people — but quite amusing if done by one and watched by another.)

Once the anchor posts are secure, cut and fit roof rafters over the anchor posts, spanning the gap between each anchor post and the one opposite it.

It’s usually easiest to staple the netting or wiring, attach the roof, and install a door and doorframe to the run after the henhouse has been framed. You’ll have to look at your particular setup and decide the proper sequence of steps.

A fully enclosed coop gives chickens freedom to roam without fear of predators.

The henhouse should be weather-tight and draft-free for the winter yet able to provide adequate ventilation for hot summer days. You can reduce the possibility of drafts by siting the henhouse adjacent to a protective wall, a fence, or shrubs. If this isn’t possible, create a windbreak by planting shrubs near the henhouse or putting up a wood fence on one or two sides of the coop area. If you keep your hens warm and dry in their run and henhouse, they’ll be happy and lay lots of eggs.

We’ve already discussed a few ways to keep hens cool in hot weather, but they’re important enough that I’ll mention them again here. To ensure your henhouse is adequately ventilated during summer, plan for one or more of the following:

However, make sure these openings are constructed so that they shut and seal tightly for cold or rainy weather.

If you’ve poured a concrete slab foundation, then the floor of the henhouse is good to go. If you’re going to set the henhouse on concrete blocks, you’ll need to frame a floor from 2 x 4s and place a large solid sheet (plywood works well) over the framework. For more detailed instructions on foundation work and framing, check out How to Build Small Barns and Outbuildings by Monte Burch (see Recommended Reading).

If the henhouse was designed to adjoin the coop, you may have installed 2 x 4 framing for the henhouse walls at the same time you were putting in anchor posts for the chicken run. If the henhouse is a freestanding structure, you’ll need to frame and roof it separately. If you don’t want to do a lot of measuring and cutting, consider buying a premade shed for use as a henhouse; you will most likely be able to put it together easily and then have to make only minor modifications to make it suitable for chicken living quarters.

If you’ve never framed anything before, I would suggest that now is the time to solicit the help of a licensed carpenter.

If the coop is close to your house and an outdoor electrical plug, you’ll be able to run extension cords out to the coop to power fans and heat lamps, when necessary. However, if your coop is located a good distance from your house, you may wish to hire an electrician to wire it. Contact the electrician early on in the construction process to find out at which stage of construction he or she would prefer to work.

Paint or seal all exterior wood. However, don’t use paint or sealant inside the henhouse — hens nibble on everything!

Inside the henhouse, secure a wooden dowel 2 inches (5 cm) in diameter to a wall, no less than 2 feet (61 cm) off the ground. Chickens always roost above the ground, for warmth and for safety. To the opposite wall, attach two or three nest boxes — little wood compartments — also about 2 feet (61 cm) off the ground. Chickens are quite secretive when laying eggs, and they like to find cozy, out of the way places to sit and lay. Make your nest boxes about the size of a shoebox stood on its narrow end, or perhaps a bit bigger for a “super-sized” hen. In colder regions, the back wall of the nest boxes should be against the inside wall of the henhouse, not against the wall exposed to the outside.

A henhouse should always have nest boxes (top right) on one wall and roosts or perches (bottom left) on another.

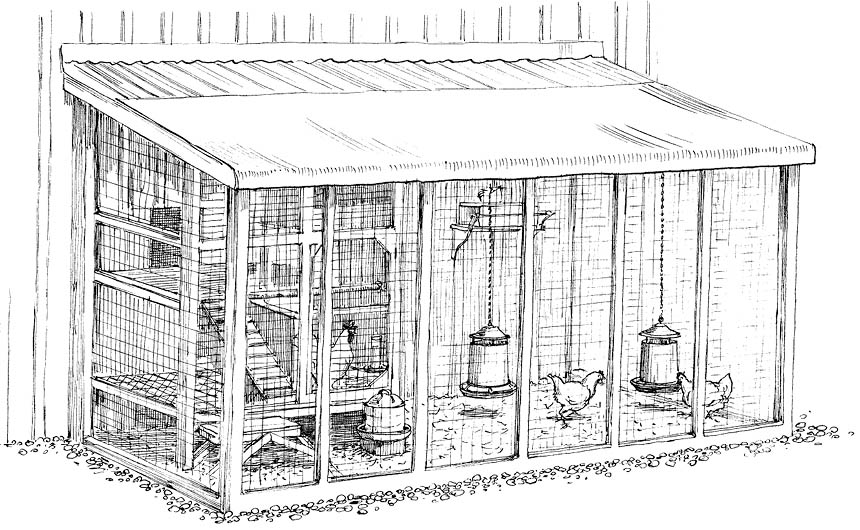

Suspend a feeder and waterer from roof rafters of the run, about 6 inches (15 cm) off the ground. If you have an open-roofed coop, put the food and water dispensers in the henhouse, away from the perch. Make sure the dispensers are away from the coop and henhouse doors and all foot traffic to prevent spillage.

Hang the feeder and waterer inside the coop’s run.

The perfect coop depends on you. You can be a minimalist. Run chicken wire around some posts for the run. Set a big wooden crate on short posts or thick, heavy bricks, cut a square hole in it for a door, lay down a small plank as a door ramp, and rig up a perch and nest box inside for roosting and laying. It can be that simple.

Or be laboriously elaborate! Add decorative moldings to the henhouse and coop framing to invoke Victorian, Bavarian, or Art Deco styles. Paint the henhouse crazy colors and hang silly signs. Or paint a mural on it of a Mexican cantina, complete with faux shutters, climbing ivy, and a sombrero, and hang a painted sign over the henhouse door that says “Casa de Pollo” (that’s “House of Chicken” for all you gringos). Use a French bistro mural theme and call your gaily painted henhouse the “Chez Poulet.”

The only limits to your henhouse design are your creative genes and your wallet. So long as your hens are safe and sound inside with plenty of personal space, the coop and henhouse design are up to you. It takes vision, chutzpah, and a certain degree of wackiness to add a chicken coop to your city garden. Why should our chickens’ coops be rudimentary when they can be extraordinary? The perfect coop is whatever you want it to look like.

My coop started as a lean-to shaped like a parallelogram alongside the house. The site available for the entire coop was narrow but long. I sank ten 2 x 4 posts in the ground with a concrete base, leaving 5 feet (1.5 m) of each post aboveground for the roof to sit on.

My spouse and I framed the roof on a slant to run off rainwater and topped it with corrugated tin. Tin roofs sound lovely in the rain. Along the eaves of the roof, we installed a PVC-pipe gutter system to divert rainwater away from the coop and into the yard. To make the gutter, we simply snipped away one-third of the diameter of the pipe, leaving a U-shaped piece. (House gutters would have worked as well, but they’re more expensive than PVC pipe.)

Next were the henhouse walls and doors. We built two human-size doors in the henhouse: one accessible from inside the coop and other at the rear, opening out into the feed and bedding storage area. We cut a small rectangular opening at the bottom of the front henhouse door so that the hens could enter and exit at will. We also installed a small slit of a door right behind the nest boxes. We call it the “egg door,” because it allows us to collect the eggs without having to enter the henhouse.

We attached the roof on the henhouse with two large hinges at the rear of the roof, nearest to the house. We can lift the henhouse roof and prop it open during hot summer days for extra ventilation.

Finally, we poured a decorative concrete walkway to the coop from the patio and trimmed it with river rock for a serene effect and to encourage drainage away from the coop. We planted native ferns, ivy, and other durable creeping and shade-tolerant plants alongside the path. The several shrubs near the walkway are sturdy enough to be practically chicken proof.

Once or twice a year, I touch up the coop and henhouse with paint and make whatever small repairs are necessary. Mostly, I just enjoy the coop and its residents.

I used to look down on the coop from a rear window in my house, but I could see only a sliver of hen action from that vantage, not nearly enough for me. I made an offhand remark to my spouse about this small dilemma. Have I mentioned my spouse’s nearly unhealthy obsession with electronics? Once word of my chicken-image deprivation was released, a solution was quickly announced. The chickens went wireless.

Wireless remote cameras, that is. We installed three of them in the henhouse and coop and then hooked them up to our TV. We can get up in the morning and turn on “Chick TV” to see what the Girls are doing, which is probably scratching and eating, but I guess I like watching that. If you love chickens as much as I do, you enjoy watching whatever they are doing. Believe me: To remote-view your chickens is to love them!

Design and build your chicken coop so it is as safe and secure from rats and predators as possible.

Most coops, no matter how ingenious and sturdy, won’t keep out rats completely, regardless of whether they are slim, surreptitious barnyard rats or fat, bold, slow city rats. Rats are expert diggers and tunnelers. If they smell chicken feed inside your coop, they will dig under the coop and pop out of a tunnel they have burrowed unerringly to right under the feeder.

I’ve tried subterranean concrete barriers. I’ve tried sinking lengths of fencing below ground. Neither worked very well to keep out the vermin. In my experience, there’s no sure-fire way to keep rats out of your chicken coop if they’re determined to get in. My advice: Be prepared for a long, continuous battle against rats.

I have found that rats are somewhat seasonal (at least up here in the Northwest). Rain in winter seems to bring them up out of the ground. Spring rat flings and resulting newborns bring rats forth like unwanted weeds in March and April. Things settle down during the summer and fall, as if the rats had packed up and gone to their summer cottages.

Don’t be discouraged. There is a way to deal with rats: poison. Poison is tricky, however, because you have to be crafty enough to give the rats access to the poison and bait trap but careful enough to keep your hens and other neighborhood animals out of the traps’ vicinity.

A few years ago, the city of Portland dealt with an increase in the city rat population by handing out “rats only” traps. These were plastic black bait boxes with a small hole big enough for a rat to fit into. The hole led through a short maze into the opposite end of the box containing rat poison. The rat ate the poison and left contented, then got a fatal stomachache a short time later. This trap set-up is quite effective, and I have never had a problem with one of my own critters getting into the bait box. Inquire at your local health department about these types of rat traps.

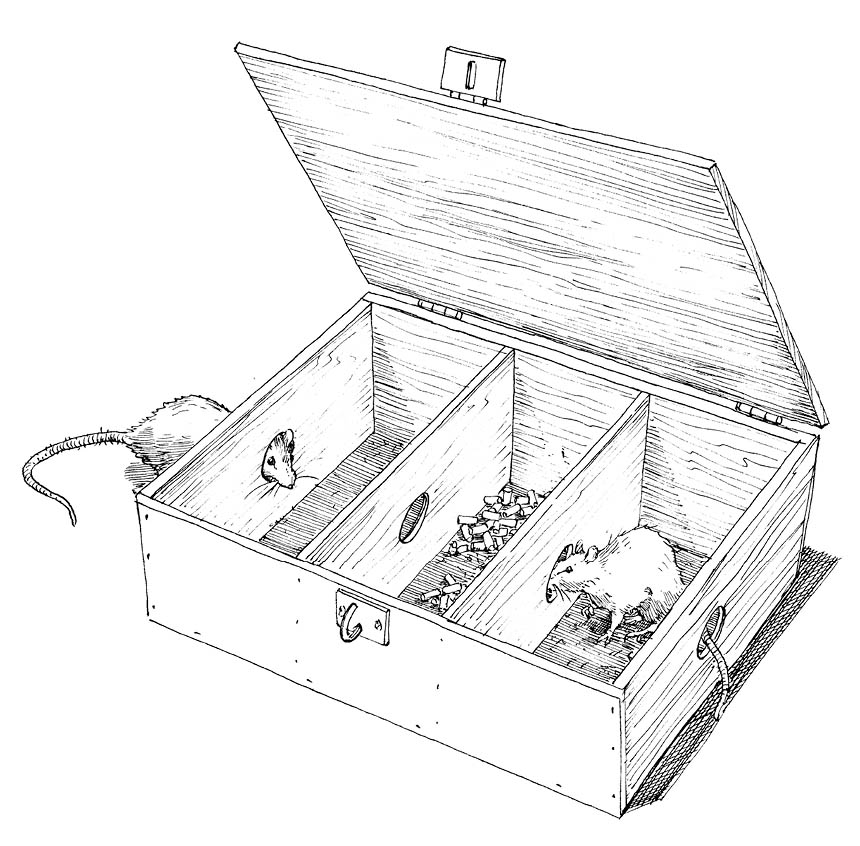

A bait box made from scrap wood provides a safe way to offer poison to rats without inadvertently injuring other local critters.

If your health department does not have bait traps available, you can build your own from scrap wood and nails. Construct a wooden box 11⁄2 feet (46 cm) long and 1 foot (31 cm) wide with a hinged and clasping or locking lid. Cut a rat-sized hole in the narrow end of the box. (Remember, rats can squeeze into an opening one-fourth their size.) Insert two partitions inside the box to create a short maze to the bait and poison location at the other end of the box.

If you’re setting a traditional “neck snapper” rodent trap, place it just outside the coop and henhouse at night. Set the trap inside a box just big enough for the trap and the rat. This way, there’s no danger of your hens or other pets getting caught by the trap. Bait trap with peanut butter for a couple of nights without setting the trap. On the third or fourth night, set the trap with the bait the rat has come to expect. You will probably have a rat to dispose of in the morning when you check on your hens.