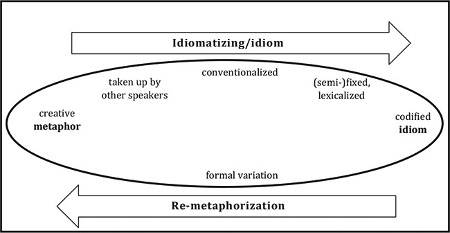

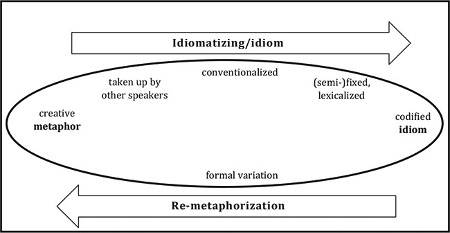

Figure 19.1 Idiom building and re-metaphorization

p.233

Creativity, idioms and metaphorical language in ELF

Marie-Luise Pitzl

Introduction

Idioms are semi-fixed (multi-word) expressions that have acquired a conventionalized, specific, usually figurative, meaning in the course of time and are usually codified with this meaning in reference works. There is an abundance of definitions of the concept in the literature, which usually also overlap with related terms like phraseology, fixed expressions, proverbs and multi-word units. Many idiom researchers have proposed a rough distinction between a broad and a more narrow definition of idiom, with the narrow meaning of idiom referring to a unit which is “fixed and semantically opaque or metaphorical” (Moon 1998: 4). Expressions in this narrow idiom category and their variable and creative use in ELF are the focus of this chapter.

For a number of years, ELF researchers have been interested in the use of idioms in ELF, investigating phenomena like idiomatizing (e.g. Seidlhofer and Widdowson 2007; Seidlhofer 2009, 2011) and chunking (e.g. Mauranen 2009), but also metaphoricity (e.g. Pitzl 2009, 2011, 2012) and figurative language (e.g. Franceschi 2013) in relation to idioms. Idioms as discussed in this article (i.e. in the narrow sense) are typically low in frequency and high in metaphoricity; they stick out from the surrounding conversation because of their figurativeness. Other expressions often referred to as ‘idiomatic’ and captured by terms like collocations, phraseological units or formulaic language are very often just the opposite: high in frequency, but low in metaphoricity. These will not be discussed here in detail (but see e.g. Mauranen 2012; Vetchinnikova 2015 for insights on ELF phraseology).

After introducing the concept of norm-following and norm-developing creativity and exploring the synchronic-diachronic link between idiom and metaphor, this chapter will use examples mostly from the Vienna-Oxford International Corpus of English (VOICE) to provide an overview of how ELF speakers vary idioms. It will discuss the multilingual aspect of metaphorical creativity in ELF settings and finally illustrate the range of functions that creative idioms and metaphors have been shown to fulfill in ELF interactions.

p.234

Creativity in language use, creativity in ELF

Many descriptive studies have brought to light the variability and situational adaptability of ELF (see e.g. Jenkins et al. 2011; Seidlhofer 2011; Cogo and Dewey 2012; Björkman 2013; Vettorel 2014 and many chapters in this handbook). Although certain processes of variation as well as certain functional motivations, such as increasing explicitness or emphasizing (see below), recur, ELF is different in each context of use, influenced by “the situationality factor which determines every lingua franca interaction anew and on its own” (Hülmbauer 2009: 323; emphasis in original). Prompted by descriptive ELF insights (from the mid-2000s onwards), creativity has thus been proposed as an essential category for ELF to help us make sense of the variability that is so characteristic of it.

Creativity is a phenomenon that psychologists often see as a precursor (or even prerequisite) for innovation and change in a particular domain (e.g. Csikszentmihalyi 1999). Fields of science or art or technology are usually seen as such domains, but so is language (cf. e.g. Carter 2004; Pope 2005; Pitzl 2012, 2013). It is therefore not surprising that creativity is generally viewed as one of the key properties of human language (e.g. Pope 2005; Yule 2010). Humans’ ability to coin new words, build novel sentences, write new texts is something that many linguists and non-linguists call creative.

If we delineate the concept more concisely in relation to variability, i.e. a key characteristic of ELF interaction, we might define linguistic creativity as “the creation of new (i.e. non-codified) linguistic forms and expressions in ongoing interaction/discourse or the use of existing forms and expressions in a non-conventional way” (Pitzl 2012: 37). Defined in this way, linguistic creativity includes new (surface) forms as well as new meanings ascribed to conventional forms. Crucially, this does not imply intentional creation or even necessarily open-choice processing (see e.g. Sinclair 1991; Erman and Warren 2000); it only describes the occurrence of forms or meanings we might call ‘creative’. Whether these forms are brought about consciously by (ELF) speakers or not, is a different matter.

As is evidenced in this definition, creativity in language use (and other domains) always relies on norms and conventions. As is discussed below, creativity needs norms, since without them, any attempt at creativity would be inappropriate, meaningless and unintelligible – and thus useless (and not creative) (see Pitzl 2013: 5–7). A crucial aspect of conceptualizing (linguistic) creativity therefore rests in the role we attribute to these norms and conventions.

Norm-following and norm-developing creativity

During the past decades of research in linguistics, linguistic creativity has, on the one hand, been conceived of as essentially rule-governed, even rule-generated by Chomsky (whose position is critically examined by Joseph 2003, for example). While Chomsky’s account of rule-generated creativity is certainly an extreme one (not shared by the author of this chapter), more moderate but similar positions on creativity being brought about through the more or less regular application of norms are also held by many non-generativists. Thus a new word can be created relying on the norms of morphology, for example. On the other hand, linguistic creativity has also been conceived as going beyond this rule-generated nature, subverting existing ‘laws’ and conventions (Ricoeur 1981 [2000]: 344). Like the first kind, this second kind of creativity necessarily involves the recognition of and reliance on existing norms. Crucially, it is not just generated by these norms; it tests their boundaries and expands them.

We can therefore distinguish two types of creativity: norm-following and norm-developing creativity. Norm-following creativity is rule-generated, combinational, and exonormative (cf. Type 1 creativity in Pitzl 2012). It encompasses the infinite number of ways in which a normative system can be realized, resulting in a potentially infinite number of creative linguistic outcomes. In contrast to this, norm-developing creativity is rule-generating, exploratory-transformational, and endonormative (cf. Type 2 creativity in Pitzl 2012). It goes beyond what the normative system allows at a certain point in time. Variability, as is so characteristic of ELF, occurs as a result of both these types of creativity. But it is the second type of creativity that may prompt linguistic change, since it has the potential to transcend the boundaries of current norms and may therefore effect changes in the normative system itself (Pitzl 2012; cf. Larsen-Freeman 2016: 141).

p.235

A crucial issue, which is the subject of ongoing discussion in ELF research (see e.g. Baird et al. 2014; Baker 2015b; Vetchinnikova 2015; Larsen-Freeman 2016) in this respect, concerns the question of what we mean by normative system. At which level are linguistic norms (creatively) applied and potentially transcended? On the one hand, it is common to conceive of ‘languages’ and ‘varieties’ as such systems. So one way of transcending conventional boundaries might be to transcend language boundaries. Code-switching, code-mixing and multilingual practices might be viewed as examples of this in many contexts (see section on metaphorical creativity and multilingual resources below). Yet, if extensive code-mixing is the common mode of communication for a particular Transient International Group (cf. Pitzl 2016) of ELF speakers, transcending language boundaries might arguably not be seen as very creative for this group (cf. e.g. Jenkins 2015; Cogo 2016). On the other hand, it is equally commonplace to view different levels within a language as normative systems (such as grammar, lexis, morphology, pronunciation – and also idioms). Each of these levels is governed by norms that are more or less regular (at the level of morphology or grammar, for example) or rather intransparent and somewhat unsystematic (like at the level of idioms). Crucially, because of these different levels, it is possible for norm-following and norm-developing creativity to occur simultaneously. So although words like increasement, approvement, or bigness (cf. Pitzl et al. 2008; Seidlhofer 2011: 103–104) are instances of norm-developing creativity (Type 2) at the level of lexis, they are also norm-following (Type 1) since they conform to general principles of ‘English’ morphology by making use of ‘regular’ suffixation. It is this tension between conventionality and norm-following creativity at one level and nonconformity and norm-developing creativity at another level that ensures intelligibility and functionality of many new linguistic expressions. This is also central for the use – and variation – of idioms in ELF interactions.

A second crucial issue, once again of particular (but not exclusive) relevance for idioms, is that norms and conventions are always tied to a particular context and point in time. Norms are not norms, once and for all. They are not generalizable across centuries, sometimes not even across decades or years. What used to be creative at one point in time, may become ‘normal’ and regular – and thus eventually un-creative. (Or it may not.) Linguistic creativity can thus be regarded as an essential driving force of language change. It offers a synchronic pragmatic window on developments that may (or may not) have more long-term diachronic effects. This synchronic-diachronic dimension of creativity is particularly relevant when we look at the notion of idiom and also metaphor, in the context of ELF, but also in L1 use of any language.

Idioms, metaphors and re-metaphorization in ELF

Considering the definition of idiom proposed at the beginning of this chapter, researchers commonly agree that the distinction between what is seen as an idiom and what as a metaphor is, in many ways, a diachronic one. Best-example idioms of a language are often described as “frozen phrases that were originally metaphors” (Hanks 2006: 26). Idioms are regarded as complex linguistic constructions that are intrinsically creative because “their internal structure incorporates the systematic and creative extension of semantic structures” (Langlotz 2006: 11).

p.236

Broadly speaking, metaphors – in themselves a highly complex category – can be viewed as instances of norm-following and potentially norm-developing creativity. They are norm-following and combinational in that they combine previously unrelated words/concepts in individual realizations of the general convention ‘A is B’. This leads to instances of norm-developing creativity at the level of semantics and idioms, i.e. new meanings and new syntagmatic combinations are created. The fact that some creative metaphors eventually become established as conventional idioms (as illustrated in Figure 19.1) indicates the link between dispersed individual instances of linguistic creativity and the general process of language variation and change.

If we are interested in idiom variation and in creativity as it occurs in ELF, it makes sense to take on board the argument that

the degree to which an idiom can be systematically and creatively manipulated in discourse is dependent on the degree to which the idiom’s intrinsic creativity [i.e. its metaphoricity] remains accessible to the language user or can be reestablished by him or her.

(Langlotz 2006: 11)

In other words, the degree of metaphoricity still inherent in a conventional idiom might be an indicator of how/in what way this conventional expression can be varied by a speaker. While the statement by Langlotz is made for L1 English use, it seems essential for ELF, which is characterized by linguistic variability (see e.g. Dewey 2009).

What we might find in ELF – as well as in language play with idioms by L1 users (e.g. Carter 2004) – is that the possibly dormant metaphors ‘contained’ in idioms are actually quite active (or re-activated) and thus allow for a considerable degree of flexibility in the formal use of an idiom, while still maintaining intelligibility through the (re-)activated metaphor. I have thus proposed that idioms might undergo a process of re-metaphorization (Pitzl 2009, 2011, 2012; cf. also Franceschi 2013: 86) in ELF (and sometimes also L1 use), through which metaphoricity is re-introduced or re-emphasized in otherwise conventionalized idioms. Whether this is done intentionally (or not) by a speaker, is secondary; the underlying mechanism of re-metaphorization is the same.

The path described by the upper arch and upper arrow in Figure 19.1 is thus the commonly known and generally accepted one in L1 use: Some creative metaphors turn into conventional, semi-fixed (and possibly codified) idioms. A conventionalized idiom (on the right) then has mostly ceased to be creative – at a particular time for a particular group of (L1) speakers in a particular context. It might still be interpreted as a creative metaphor, however, by someone who is not part of the particular group of speakers (or by someone who makes the interpretation in a different decade or century).

p.237

Figure 19.1 Idiom building and re-metaphorization

If the idiom is varied in form, whether intentionally or not, and therefore different from what is conventional at the time for the group, this is an instance of linguistic creativity, as defined above. Some idiom variations might be norm-following creativity in that they are relatively systematic. Whether a speaker says smooth the way or smooth the path, for example, makes relatively little difference semantically, as way and path are nearly synonymous. If an ELF speaker in VOICE says we should not wake up any dogs (cf. Pitzl 2009) or it will explore por- hopefully not in our faces but it will explore (cf. Pitzl 2012), however, this clearly transcends the boundaries of conventional syntagmatic idiom structures; so these examples would be instances of the second type of creativity (i.e. norm-developing). Crucially, this does not mean that these occurrences necessarily lead to long-term changes; it just means that they would have the potential to trigger them.

Formal variation, especially when it transcends accepted conventional use, can thus heighten and re-emphasize the metaphoricity of an expression through the process of re-metaphorization (see the lower arch and lower arrow in Figure 19.1). Instead of regarding an idiom as a frozen or dead metaphor, one might therefore consider certain deliberate uses of metaphors in ELF as formally resembling already existing English – or also other language – idioms. Crucially, re-metaphorization is not a process that is ‘reserved’ or specific just to ELF; it also happens in L1 use (e.g. in language play and punning as well as unintentional idiom variation by ‘native speakers’). Similarily, idiom building is not just the prerogative of L1 speakers, but can also happen in ELF contexts (see e.g. Seidlhofer 2009).

Starting with more conventional and systematic examples of idiom variation, the next section will outline how ELF speakers vary idioms. This will be followed by a short discussion of more complex instances of creative idioms that relate to the multilingual dimension of metaphorical creativity. Finally, the range of functions that creative idioms and metaphorical language fulfill in ELF interactions will be illustrated.

How are idioms varied in ELF?

In describing formal characteristics of creative idioms in ELF (i.e. idioms that are instances of linguistic creativity), it makes sense to start categorizing examples according to three types of idiom variation that are well attested also in L1 English corpora: lexical substitution, syntactic variation and morphosyntactic variation (cf. Langlotz 2006: 179). The examples cited in the following sections are produced by ELF speakers in speech events recorded in VOICE, unless otherwise indicated.

Beginning with the first type, lexical substitution means that a speaker replaces one lexical element in an idiom with another lexical element. Original and substituted elements tend to belong to the same word class, i.e. a noun is usually replaced by a noun, an adjective by an adjective. One way of classifying instances of creative idioms with lexical substitution is therefore in relation to the word class. Alternatively, however, it seems more interesting to look at the semantic relationship between the two words (cf. Langlotz 2006: 180).

p.238

Not surprisingly, ELF speakers generally tend to substitute semantically related words, creating expressions like draw the limits (cf. ‘draw the line’) or turn a blank eye (cf. ‘turn a blind eye’). Sometimes these substituted words are hyponyms or superordinate terms, such as in don’t kill the messengers (cf. ‘shoot the messenger’) or sit in the control of (cf. ‘be in control of’) in VOICE. Examples of this are also found in ELF online use by Vettorel (2014: 202), for example play with phrases (cf. ‘play with words’), and in ELFA (English as a lingua franca in academic settings) by Franceschi (2013: 86), for example, don’t step on each other’s feet (cf. ‘step on somebody’s toes’). In the example by Franceschi, a term of embodiment is substituted for another (feet for toes), but lexical substitution also occurs with terms of embodiment being used in the place of more abstract concepts. Examples of this kind in VOICE are keep in the head (cf. ‘bear/ keep [sb/sth] in mind’) or doesn’t come to their head (cf. ‘come to mind’) (cf. also Seidlhofer 2009: 204–205; Pitzl forthc.). Only on rare occasions is the substituted word more abstract than the original. If this is the case, the substituted term is usually more closely linked to the topic of discussion, as in smooth the process (cf. ‘smooth the path/way’), which is uttered when ELF speakers are actually discussing a process.

With regard to morphosyntactic variation, creative idioms in VOICE exhibit instances of pluralization, (such as carved in stones or pieces by pieces), flexible use of determiners (like in sit in the control of, already mentioned above), and prepositional variation such as in the right track, on the long run and remember from the head (cf. also examples in Vettorel 2014: 202–203 in ELF online use). Syntactic variation, i.e. changes in the constructions that are considered part of an idiom, happens either via extending constructions or, more frequently, via internal syntactic modification. Such internal modification may, for example, occur through insertion of adjectives, adverbs or pronouns. Some examples of this in VOICE are a bigger share of this pie, go er into much details, the big crest of the wave and two different sides of the same coin.

As some examples indicate, the three types of variation are not mutually exclusive. They can occur in combination, up to the point where it becomes difficult to identify a particular type (or types) of variation. Thus, expressions like it will explode por-hopefully not in our faces but it will explode or the phrase i feel that many times i am pulling the brakes are varied considerably from potentially corresponding idioms, to the extent that it seems justifiable to regard them also without reference to conventional idioms. As ELF speakers build on, re-activate and exploit the “metaphoric potential” (Cameron 1999: 108) and inherent creativity (cf. Langlotz 2006: 11) of conventional expressions, it makes sense to look at some examples primarily as instances of metaphorical creativity, that is to say, new linguistic forms and expressions that rely upon and become possible through metaphor as a shared universal mechanism.

Metaphorical creativity and multilingual resources

Shifting the focus from idiom to metaphor, we can therefore posit that deliberate metaphors and metaphorical creativity in ELF interactions tend to arise in three different ways: they may be related to and varied from existing English idioms (like most examples in the previous section). Second, they may be entirely novel in that the metaphorical image seems to be created ad hoc by the speaker. And third, metaphors may be created when other language idioms are transplanted into ELF. While in theory, each of these scenarios can occur on its own, expressions like we should not wake up any dogs illustrate that more than one of them may also apply to the same expression. That is to say, the metaphor we should not wake up any dogs may have been influenced by an idiom from another language as well as by an English idiom (see Pitzl 2009: 308–310).

p.239

The extent to which the individual multilingual repertoires (IMRs) of speakers in an ELF interaction will overlap in the shared multilingual resource pool (MRP) of a particular ELF group is unpredictable (see Pitzl 2016; cf. also Hülmbauer 2009, 2013; Cogo 2012). The shared MRP of a group of ELF speakers is bound to vary considerably from context to context and will often only be discovered gradually by participants throughout an interaction (see Jenkins 2015: 64). Sometimes speakers’ IMRs may overlap quite a bit; in other ELF contexts, they may be rather distinct.

Of course, idioms in languages other than English are always present in ELF speakers’ IMRs – and any idiom that is part of the speaker’s IMR is linked to a particular metaphorical image. We can thus conceive of a speaker’s IMR as encompassing idioms in several languages as well as their corresponding metaphors. This means that the shared MRP in a particular ELF context also encompasses (the same or similar) idioms in different languages – as well as the corresponding metaphors and mental images. Participants in an ELF situation therefore do not only have a shared MRP, but, more specifically a shared multilingual idiom resource pool and a shared multilingual metaphor resource pool (see Pitzl 2011: 289–290; 2016: 301–304). If, to what extent and how ELF speakers make use of these (shared) non-English idioms and metaphors, however, is situationally dependent.

When non-English idioms and/or their corresponding metaphorical images become relevant in ELF contexts, this can happen in essentially two ways. On the one hand, metaphorical images inherent in non-English idioms can ‘leak’ (see Jenkins 2015: 75 on ‘language leakage’) into ELF discourse without speakers’ (and listeners’) awareness, for example by means of implicit and usually unconscious transfer. This is, of course, a process that is not unique to ELF as a site of transient language contact in transient international groups (Pitzl 2011: 33–36; 2016; see also Jenkins 2015) but a process that is equally relevant for long-term language contact situations typical in postcolonial settings (see Schneider 2012). On the other hand, non-English idioms may enter ELF interactions as explicitly signaled and flagged instances of multilingual metaphorical creativity that function as representations of multilingual and multi/transcultural identities and repertoires. In these cases, the speakers themselves draw attention to the multilingual and transcultural nature of ELF as a site of language contact and emphasize that ELF is always more than just ‘English’ or ‘Anglo’.

Such explicit signaling can occur with ‘Englishized’ versions, i.e. non-English idioms and metaphorical images from other languages translated into English. This happens, for example, when a Dutch ELF speaker introduces a saying in holland that er we don’t have savings but under the bed we have a lot of er money in the sock in an ELF business meeting in VOICE (see Pitzl 2009: 314–316). Yet, metaphorical creativity may occasionally also involve switches into another language, which may (or may not) be the speaker’s L1. When a Serbian ELF speaker in conversation with Maltese ELF speakers signals we [i.e. Serbians] have a proverb like Italians immediately before uttering the idiom fuma come un turco in its original Italian wording in VOICE, this switch is clearly motivated by the particular situation; it is appropriate and functional because of the shared MRP of these particular ELF speakers. Uttering the proverb in Italian, the Serbian ELF speaker indicates “a special bond to another language or culture” (Klimpfinger 2009: 361) with regard to Italian, i.e. the language she switches into, but also with regard to Serbian (i.e. her L1), which, she says, has a proverb just like Italian. She displays her multilingual identity and builds linguistic as well as ‘cultural’ rapport with her Maltese ELF interlocutors, who, she knows, will understand her Italian phrase (see Pitzl 2016 for a more detailed discussion).

p.240

Why do ELF speakers use metaphors and creative idioms?

As is illustrated by this example of multilingual metaphorical creativity, ELF speakers’ use of idioms and metaphors – including non-English ones – tends to fulfill a range of functions in different ELF contexts. Signaling ‘cultural’ affiliation(s) and multilingual identities is particularly noticeable when non-English idioms are explicitly introduced, as in the examples in the previous section. Oftentimes ELF speakers negotiate their ‘cultural’ identities as individuals and/or members of particular communities in ELF encounters, affiliating (or distancing) themselves from others (cf. Baker 2015a, 2015b; Zhu Hua 2015). In this way, ELF speakers build inter/transcultural territories relevant to particular ELF contexts. As illustrated, this inter/transcultural dimension of (non-English) idioms and metaphors often also coincides with other functions, like creating solidarity and rapport in the case of fuma come un turco.

When creative idioms and metaphors are used without explicit reference to other languages/cultures, they fulfill a range of specific functions in ELF interactions that can be broadly organized along the lines of Halliday’s (1985: xiii) distinction between ideational and interpersonal (see e.g. Pitzl 2012; Pitzl forthc.). A similar organization of two overall categories is also suggested by Franceschi (2013), who distinguishes communication strategies and social functions in relation to idioms in ELFA, a distinction that also partly corresponds to the Hallidayan one.

With regard to the interpersonal/social dimension of idioms and metaphors, establishing and maintaining rapport and solidarity are just one aspect, illustrated for example by creative idioms like we are all on the same [. . .] on the same boat I think . . . on the bus on the train discussed by Cogo (2010: 303). Related to maintaining rapport, creative idioms and metaphors are also used by ELF speakers to mitigate propositions and minimize potential face threats, which may involve humorous undertones, as in the ball is in your corner in VOICE (Pitzl forthc.; see also examples in Pitzl 2009; Franceschi 2013). Humor and joking by means of metaphorical creativity can, however, also occur just for their own sake, i.e. without being intended to mitigate a face threat. Furthermore, ELF speakers sometimes use creative idioms and metaphors to express subjectivity, project stance and position themselves in relation to a particular issue, as in expressions like to my head or i feel that many times i am pulling the brakes in VOICE.

When we turn to the second category, i.e. idioms and metaphors being used for ideational and transactional purposes, metaphorical expressions serve functions like emphasizing (e.g. i’m up to my hh big toe i’m a cargo guy; all this shit it takes hell a lot of time), summarizing (e.g. what i was trying to sort of like put together in a nutshell here) and increasing explicitness (e.g. a joint program doe- doesn’t exist in the air so to say) in different ELF interactions. On several occasions, these transactional functions become especially relevant when speakers are discussing rather abstract concepts or topics that they try to explain or describe by using metaphors and idioms.

A central characteristic of many creative idioms and metaphors in ELF interactions is that they are multifunctional, that is to say they fulfill more than one specific function. Thus, many instances of metaphorical creativity cited above operate at an interpersonal as well as at an ideational level. The same phrase can express humor and mitigate a sensitive proposition (interpersonal/interactional) and summarize what was said before (ideational/ transactional). Although evidence in VOICE suggests that some ELF speakers have a greater tendency of using creative idioms and metaphors than others, metaphorical creativity as discussed in this chapter is widely used by ELF speakers from all kinds of L1 backgrounds. Individual creative expressions, as illustrated in this chapter, are generally not on the way to becoming new lexicalized ‘ELF idioms’, i.e. they are not on the way ‘back’ to becoming conventional idioms in the idiom-metaphor loop proposed in Figure 19.1. They are, however, part of localized practices of ELF communication. Rather than being a hindrance or the cause for confusion, they are usually successful in the respective ELF contexts in fulfilling a range of interpersonal and ideational discourse functions.

p.241

Conclusion

This chapter has summarized existing research on creativity and the use of idioms and metaphor in ELF. Having outlined the notion of norm-following and norm-developing creativity, it has discussed these concepts in relation to idiom and metaphor, paying particular attention to the synchronic-diachronic link of idiom and metaphor and to the process of re-metaphorization. In the second half, the article has attempted to provide insights to the questions how idioms are varied and why they are used by ELF speakers. Relying primarily (though not exclusively) on examples from VOICE, the chapter has provided an overview of different types of formal idiom variation, such as lexical substitution, syntactic and morphosyntactic variation. The multilingual aspect of metaphorical creativity was discussed, showing how non-English idioms may enter ELF either implicitly (without being flagged or noticed) or explicitly as ‘Englishized’ versions or code-switches. Finally, the range of interpersonal and ideational functions fulfilled by creative idioms and metaphors was illustrated, providing evidence that metaphorical creativity is part of ELF as situationally created by multilingual speakers.

Related chapters in this handbook

4 Larsen-Freeman, Complexity and ELF

16 Osimk-Teasdale, Analysing ELF variability

17 Cogo and House, The pragmatics of ELF

24 Canagarajah and Kumura, Translingual Practice and ELF

27 Pullin, Humour in ELF interaction

29 Cogo, ELF and multilingualism

40 Wright and Zheng, Language as system and language as dialogic creativity: the difficulties of teaching English as a lingua franca in the classroom

Further reading

Franceschi, V. (2013). Figurative language and ELF: idiomaticity in cross-cultural interaction in university settings. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 2 (1), pp. 75–99.

p.242

Pitzl, M.-L. (2009). “We should not wake up any dogs”: idiom and metaphor in ELF. In Mauranen, A. and Ranta, E. (eds), English as a lingua franca: Studies and findings. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 299–322.

Seidlhofer, B. (2009). Accommodation and the idiom principle in English as a lingua franca. Intercultural Pragmatics, 6 (2), pp. 195–215.

References

Baird, R., Baker, W. and Kitazawa, M. (2014). The complexity of ELF. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 3(1), pp. 171–196.

Baker, W. (2015a). Culture and complexity through English as a lingua franca: rethinking competences and pedagogy in ELT. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 4(1), pp. 9–30.

Baker, W. (2015b). Culture and identity through English as a Lingua Franca: Rethinking concepts and goals in intercultural communication. Boston, MA: De Gruyter Mouton.

Björkman, B. (2013). English as an academic lingua franca: An investigation of form and communicative effectiveness. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

Cameron, L. (1999). Identifying and describing metaphor in spoken discourse. In Cameron, L. and Low, G.D. (eds), Researching and applying metaphor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 105–132.

Carter, R. (2004). Language and creativity. The art of common talk. Abingdon: Routledge.

Cogo, A. (2010). Strategic use and perceptions of English as a lingua franca. Poznan Studies in Contemporary Linguistics, 46 (3), pp. 295–312.

Cogo, A. (2012). ELF and super-diversity: a case study of ELF multilingual practices from a business context. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 1 (2), pp. 287–313.

Cogo, A. (2016). “They all take the risk and make the effort”: intercultural accommodation and multilingualism in a BELF community of practice. In Lopriore, L. and Grazzi, E. (eds), Intercultural communication: New perspectives from ELF. Rome: Roma Tre Press, pp. 365–383.

Cogo, A. and Dewey, M. (2012). Analyzing English as a lingua franca: A corpus-driven investigation. London: Continuum.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1999). Implications of a systems perspective for the study of creativity. In Sternberg, R. (ed.), Handbook of creativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 313–335.

Dewey, M. (2009). English as a lingua franca: heightened variability and theoretical implications. In Mauranen, A. and Ranta, E. (eds), English as a lingua franca: Studies and findings. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 60–83.

ELFA. (2008). The corpus of English as a lingua franca in academic settings. www.helsinki.fi/elfa/elfacorpus (accessed 22 December 2016).

Erman, B. and Warren, B. (2000). The idiom principle and the open choice principle. Text, 20 (1), pp. 29–62.

Franceschi, V. (2013). Figurative language and ELF: idiomaticity in cross-cultural interaction in university settings. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 2 (1), pp. 75–99.

Halliday, M. (1985). An introduction to functional grammar. London: Edward Arnold.

Hanks, P. (2006). Metaphoricity is gradable. In Stefanowitsch, A. and Gries, S.T. (eds), Corpus-based approaches to metaphor and metonymy. Berlin: de Gruyter, pp. 17–35.

Hülmbauer, C. (2009). “We don’t take the right way. We just take the way that we think you will understand”: the shifting relationship between correctness and effectiveness in ELF communication. In Mauranen, A. and Ranta, E. (eds), English as a lingua franca: Studies and findings. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 323–347.

Hülmbauer, C. (2013). The real, the virtual and the plurilingual: English as a lingua franca in a linguistically diversified Europe. Unpublished Dissertation: Universität Wien.

Jenkins, J. (2015). Repositioning English and multilingualism in English as a lingua franca. Englishes in Practice, 2 (3), pp. 49–85.

Jenkins, J., Cogo, A. and Dewey, M. (2011). Review of developments in research into English as a lingua franca. Language Teaching, 44 (3), pp. 281–315.

Joseph, J.E. (2003). Rethinking linguistic creativity. In Davis, H.G. and Taylor, T.J. (eds), Rethinking linguistics. London: Routledge Curzon, pp. 121–150.

Klimpfinger, T. (2009). “She’s mixing the two languages together”: forms and functions of code-switching in English as a lingua franca. In Mauranen, A. and Ranta, E. (eds), English as a lingua franca: Studies and findings. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 348–371.

p.243

Langlotz, A. (2006). Idiomatic creativity: A cognitive-linguistic model of idiom-representation and idiom-variation in English. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2016). Complexity theory and ELF: a matter of nonteleology. In Pitzl, M.-L. and Osimk-Teasdale, R. (eds), English as a lingua franca: Perspectives and prospects. Contributions in honour of Barbara Seidlhofer. Boston, MA: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 139–145.

Mauranen, A. (2009). Chunking in ELF: expressions for managing interaction. Intercultural Pragmatics, 6 (2), pp. 217–233.

Mauranen, A. (2012). Exploring ELF: Academic English shaped by non-native speakers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moon, R. (1998). Fixed expressions and idioms in English: A corpus-based approach. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Pitzl, M.-L. (forthc.). Creativity in English as a lingua franca: Idiom and metaphor. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Pitzl, M.-L. (2009). “We should not wake up any dogs”: idiom and metaphor in ELF. In Mauranen, A. and Ranta, E. (eds), English as a lingua franca: Studies and findings. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 299–322.

Pitzl, M.-L. (2011). Creativity in English as a lingua franca: Idiom and metaphor. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Vienna.

Pitzl, M.-L. (2012). Creativity meets convention: idiom variation and re-metaphorization in ELF. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 1 (1), pp. 27–55.

Pitzl, M.-L. (2013). Creativity in language use. In Östman, J.-O. and Verschueren, J. (eds), Handbook of Pragmatics: 2013 Installment. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 1–28.

Pitzl, M.-L. (2016). World Englishes and creative idioms in English as a lingua franca. World Englishes, 35 (2) (Special issue on Language contact in World Englishes), pp. 293–209.

Pitzl, M.-L., Breiteneder, A. and Klimpfinger, T. (2008). A world of words: processes of lexical innovation in VOICE. Vienna English Working Papers, 17 (2), pp. 21–46. Available from: http://anglistik.univie.ac.at/fileadmin/user_upload/dep_anglist/weitere_Uploads/Views/views_0802.pdf (accessed 1 April 2016).

Pope, R. (2005). Creativity: History, theory and practice. London: Routledge.

Ricoeur, P. (1981) [2000]. The creativity of language. In Burke, L. Crowley, T. and Girvin, A. (eds), The Routledge language and cultural theory reader. London: Routledge, pp. 340–344.

Schneider, E.W. (2012). Exploring the interface between World Englishes and second language acquisition – and implications for English as a lingua franca. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 1 (1), pp. 57–91.

Seidlhofer, B. (2009). Accommodation and the idiom principle in English as a lingua franca. Intercultural Pragmatics, 6 (2), pp. 195–215.

Seidlhofer, B. (2011). Understanding English as a lingua franca. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Seidlhofer, B. and Widdowson, H.G. (2007). Idiomatic variation and change in English: The idiom principle and its realizations. In Smit, U., Dollinger, S., Hüttner, J., Kaltenböck, G. and Lutzky, U. (eds), Tracing English through time: Explorations in language variation (Festschrift for Herbert Schendl, Austrian Studies in English vol. 95). Wien: Braumüller, pp. 359–374.

Sinclair, J. (1991). Corpus, concordance, collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vetchinnikova, S. (2015). Usage-based recycling or creative exploitation of the shared code? The case of phraseological patterning. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 4 (2), pp. 223–252.

Vettorel, P. (2014). English as a lingua franca in wider networking: Blogging practices. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

VOICE. (2013). The Vienna-Oxford International Corpus of English (version 2.0 online). Director: Barbara Seidlhofer; Researchers: Angelika Breiteneder, Theresa Klimpfinger, Stefan Majewski, Ruth Osimk-Teasdale, Marie-Luise Pitzl, Michael Radeka. http://voice.univie.ac.at (accessed 1 April 2016).

Yule, G. (2010). The study of language (4th edn). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zhu Hua, (2015). Negotiation as the way of engagement in intercultural and lingua franca communication: Frames of reference and interculturality. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 4 (1), pp. 63–90.