In recent years, data-based marketing has swept through the business world. In its wake, measurable performance and accountability have become the keys to marketing success. However, few managers appreciate the range of metrics by which they can evaluate marketing strategies and dynamics. Fewer still understand the pros, cons, and nuances of each.

In this environment, we have come to recognize that marketers, general managers, and business students need a comprehensive, practical reference on the metrics used to judge marketing programs and quantify their results. In this book, we seek to provide that reference. We wish our readers great success with it.

A metric is a measuring system that quantifies a trend, dynamic, or characteristic.1 In virtually all disciplines, practitioners use metrics to explain phenomena, diagnose causes, share findings, and project the results of future events. Throughout the worlds of science, business, and government, metrics encourage rigor and objectivity. They make it possible to compare observations across regions and time periods. They facilitate understanding and collaboration.

“When you can measure what you are speaking about, and express it in numbers, you know something about it; but when you cannot measure it, when you cannot express it in numbers, your knowledge is of a meager and unsatisfactory kind: it may be the beginning of knowledge, but you have scarcely, in your thoughts, advanced to the stage of science.”—William Thomson, Lord Kelvin, Popular Lectures and Addresses (1891–94)2

Lord Kelvin, a British physicist and the manager of the laying of the first successful transatlantic cable, was one of history’s great advocates for quantitative investigation. In his day, however, mathematical rigor had not yet spread widely beyond the worlds of science, engineering, and finance. Much has changed since then.

Today, numerical fluency is a crucial skill for every business leader. Managers must quantify market opportunities and competitive threats. They must justify the financial risks and benefits of their decisions. They must evaluate plans, explain variances, judge performance, and identify leverage points for improvement—all in numeric terms. These responsibilities require a strong command of measurements and of the systems and formulas that generate them. In short, they require metrics.

Managers must select, calculate, and explain key business metrics. They must understand how each is constructed and how to use it in decision-making. Witness the following, more recent quotes from management experts:

“. . . every metric, whether it is used explicitly to influence behavior, to evaluate future strategies, or simply to take stock, will affect actions and decisions.”3

“If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.”4

Marketers are by no means immune to the drive toward quantitative planning and evaluation. Marketing may once have been regarded as more an art than a science. Executives may once have cheerfully admitted that they knew they wasted half the money they spent on advertising, but they didn’t know which half. Those days, however, are gone.

Today, marketers must understand their addressable markets quantitatively. They must measure new opportunities and the investment needed to realize them. Marketers must quantify the value of products, customers, and distribution channels—all under various pricing and promotional scenarios. Increasingly, marketers are held accountable for the financial ramifications of their decisions. Observers have noted this trend in graphic terms:

“For years, corporate marketers have walked into budget meetings like neighborhood junkies. They couldn’t always justify how well they spent past handouts or what difference it all made. They just wanted more money—for flashy TV ads, for big-ticket events, for, you know, getting out the message and building up the brand. But those heady days of blind budget increases are fast being replaced with a new mantra: measurement and accountability.”5

The numeric imperative represents a challenge, however. In business and economics, many metrics are complex and difficult to master. Some are highly specialized and best suited to specific analyses. Many require data that may be approximate, incomplete, or unavailable.

Under these circumstances, no single metric is likely to be perfect. For this reason, we recommend that marketers use a portfolio or “dashboard” of metrics. By doing so, they can view market dynamics from various perspectives and arrive at “triangulated” strategies and solutions. Additionally, with multiple metrics, marketers can use each as a check on the others. In this way, they can maximize the accuracy of their knowledge.6 They can also estimate or project one data point on the basis of others. Of course, to use multiple metrics effectively, marketers must appreciate the relations between them and the limitations inherent in each.

When this understanding is achieved, however, metrics can help a firm maintain a productive focus on customers and markets. They can help managers identify the strengths and weaknesses in both strategies and execution. Mathematically defined and widely disseminated, metrics can become part of a precise, operational language within a firm.

A further challenge in metrics stems from wide variations in the availability of data between industries and geographies. Recognizing these variations, we have tried to suggest alternative sources and procedures for estimating some of the metrics in this book.

Fortunately, although both the range and type of marketing metrics may vary between countries,7 these differences are shrinking rapidly. Ambler,8 for example, reports that performance metrics have become a common language among marketers, and that they are now used to rally teams and benchmark efforts internationally.

Being able to “crunch the numbers” is vital to success in marketing. Knowing which numbers to crunch, however, is a skill that develops over time. Toward that end, managers must practice the use of metrics and learn from their mistakes. By working through the examples in this book, we hope our readers will gain both confidence and a firm understanding of the fundamentals of data-based marketing. With time and experience, we trust that you will also develop an intuition about metrics, and learn to dig deeper when calculations appear suspect or puzzling.

Ultimately, with regard to metrics, we believe many of our readers will require not only familiarity but also fluency. That is, managers should be able to perform relevant calculations on the fly—under pressure, in board meetings, and during strategic deliberations and negotiations. Although not all readers will require that level of fluency, we believe it will be increasingly expected of candidates for senior management positions, especially those with significant financial responsibility. We anticipate that a mastery of data-based marketing will become a means for many of our readers to differentiate and position themselves for career advancement in an ever more challenging environment.

This book is organized into chapters that correspond to the various roles played by marketing metrics in enterprise management. Individual chapters are dedicated to metrics used in promotional strategy, advertising, and distribution, for example. Each chapter is composed of sections devoted to specific concepts and calculations.

Inevitably, we must present these metrics in a sequence that will appear somewhat arbitrary. In organizing this text, however, we have sought to strike a balance between two goals: (1) to establish core concepts first and build gradually toward increasing sophistication, and (2) to group related metrics in clusters, helping our readers recognize patterns of mutual reinforcement and interdependence. In Figure 1.1, we offer a graphical presentation of this structure, demonstrating the interlocking nature of all marketing metrics—indeed of all marketing programs—as well as the central role of the customer.

Figure 1.1. Marketing Metrics: Marketing at the Core of the Organization

The central issues addressed by the metrics in this book are as follows:

• Chapter 2—Share of Hearts, Minds, and Markets: Customer perceptions, market share, and competitive analysis.

• Chapter 3—Margins and Profits: Revenues, cost structures, and profitability.

• Chapter 4—Product and Portfolio Management: The metrics behind product strategy, including measures of trial, growth, cannibalization, and brand equity.

• Chapter 5—Customer Profitability: The value of individual customers and relationships.

• Chapter 6—Sales Force and Channel Management: Sales force organization, performance, and compensation. Distribution coverage and logistics.

• Chapter 7—Pricing Strategy: Price sensitivity and optimization, with an eye toward setting prices to maximize profits.

• Chapter 8—Promotion: Temporary price promotions, coupons, rebates, and trade allowances.

• Chapter 9—Advertising Media and Web Metrics: The central measures of advertising coverage and effectiveness, including reach, frequency, rating points, and impressions. Models for consumer response to advertising. Specialized metrics for Web-based campaigns.

• Chapter 10—Marketing and Finance: Financial evaluation of marketing programs.

• Chapter 11—The Marketing Metrics X-Ray: The use of metrics as leading indicators of opportunities, challenges, and financial performance.

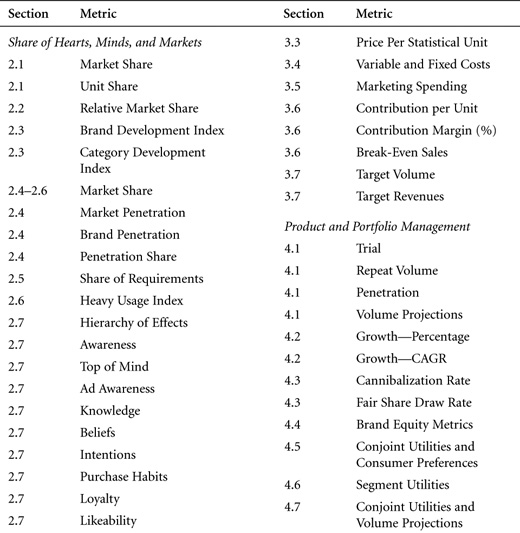

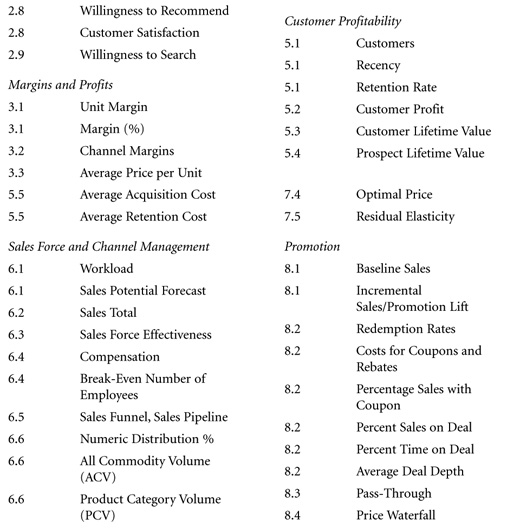

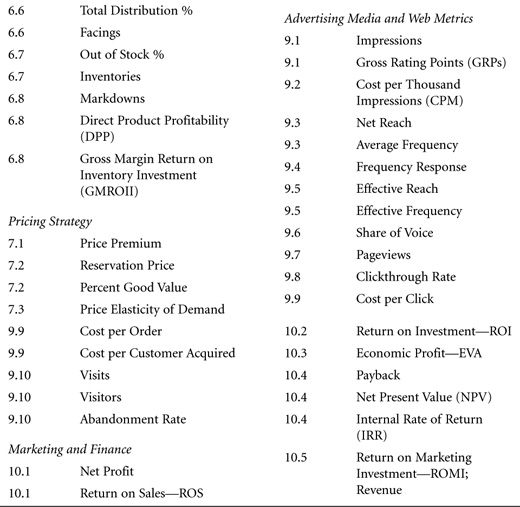

As shown in Table 1.1, the chapters are composed of multiple sections, each dedicated to specific marketing concepts or metrics. Within each section, we open with definitions, formulas, and a brief description of the metrics covered. Next, in a passage titled Construction, we explore the issues surrounding these metrics, including their formulation, application, interpretation, and strategic ramifications. We provide examples to illustrate calculations, reinforce concepts, and help readers verify their understanding of key formulas. That done, in a passage titled Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions, we probe the limitations of the metrics under consideration, and potential pitfalls in their use. Toward that end, we also examine the assumptions underlying these metrics. Finally, we close each section with a brief survey of Related Metrics and Concepts.

In organizing the text in this way, our goal is straightforward: Most of the metrics in this book have broad implications and multiple layers of interpretation. Doctoral theses could be devoted to many of them, and have been written about some. In this book, however, we want to offer an accessible, practical reference. If the devil is in the details, we want to identify, locate, and warn readers against him, but not to elaborate his entire demonology. Consequently, we discuss each metric in stages, working progressively toward increasing levels of sophistication. We invite our readers to sample this information as they see fit, exploring each metric to the depth that they find most useful and rewarding.

With an eye toward accessibility, we have also avoided advanced mathematical notation. Most of the calculations in this book can be performed by hand, on the back of the proverbial envelope. More complex or intensive computations may require a spreadsheet. Nothing further should be needed.

Throughout this text, we have highlighted formulas and definitions for easy reference. We have also included outlines of key terms at the beginning of each chapter and section. Within each formula, we have followed this notation to define all inputs and outputs.

$—(Dollar Terms): A monetary value. We have used the dollar sign and “dollar terms” for brevity, but any other currency, including the euro, yen, dinar, or yuan, would be equally appropriate.

%—(Percentage): Used as the equivalent of fractions or decimals. For readability, we have intentionally omitted the step of multiplying decimals by 100 to obtain percentages.

#—(Count): Used for such measures as unit sales or number of competitors.

R—(Rating): Expressed on a scale that translates qualitative judgments or preferences into numeric ratings. Example: A survey in which customers are asked to assign a rating of “1” to items that they find least satisfactory and “5” to those that are most satisfactory. Ratings have no intrinsic meaning without reference to their scale and context.

I—(Index): A comparative figure, often linked to or expressive of a market average. Example: the consumer price index. Indexes are often interpreted as a percentage.

Abela, Andrew, Bruce H. Clark, and Tim Ambler. “Marketing Performance Measurement, Performance, and Learning,” working paper, September 1, 2004.

Ambler, Tim, and Chris Styles. (1995). “Brand Equity: Toward Measures That Matter,” working paper No. 95-902, London Business School, Centre for Marketing.

Barwise, Patrick, and John U. Farley. (2003). “Which Marketing Metrics Are Used and Where?” Marketing Science Institute, (03-111), working paper, Series issues two 03-002.

Clark, Bruce H., Andrew V. Abela, and Tim Ambler. “Return on Measurement: Relating Marketing Metrics Practices to Strategic Performance,” working paper, January 12, 2004.

Hauser, John, and Gerald Katz. (1998). “Metrics: You Are What You Measure,” European Management Journal, Vo. 16, No. 5, pp. 517–528.

Kaplan, R. S., and D. P. Norton. (1996). The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action, Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.