1

THE EFFLORESCENCE OF CLASSICAL GREECE

FAIR GREECE, SAD RELIC

In 1812, Lord Byron published a poem that made him the hero of a world poised at the brink of modernity and ready for romance. It included these poignant lines:

Fair Greece! sad relic of departed worth!

Immortal, though no more! though fallen, great!1

With just fourteen words, Byron illuminated the stark contrast between Greek antiquity and the Greece he had observed during his travels in 1809 and 1810. Byron knew a lot about Greece. As an educated English nobleman, he had read classical literature. As an intrepid traveler, he had personal experience of early nineteenth century Greece. By Byron’s day, the Greeks had suffered as subjects of the Ottoman Empire for more than 300 years, and, more recently, from the rapacity of European collectors. But Greece was already a “relic of departed worth” when Pausanias, a travel writer of the Roman imperial age, described Greek antiquities in the second century. Neither Byron nor Pausanias could have guessed that at the dawn of the twentieth century, Greece would be the poorest country in Europe or that in the early twenty-first century, two centuries after Byron wrote his memorable lines, Greece would be sadder yet—wracked by a political and economic crisis that immiserated millions of Greek citizens and threatened the financial stability of Europe.2

Byron’s vision of greatness was inspired by ancient Greek cultural and intellectual achievement: art and architecture, literature, visual and performance art, scientific and moral thought. A generation later, the British banker-scholar George Grote published his monumental History of Greece (12 volumes: 1846–1856), a work that came to define, for the English-speaking world, the greatness of classical Greece in terms of a unique set of values and institutions: democracy, freedom, equality, dignity—conjoined with a dedication to reason, critical inquiry, and innovation.

Despite its brevity and limited frame, Byron’s romantic couplet, with its sharp contrast between the fortunes of ancient and modern Greece and its explosion of exclamation points, captures the mystery that this book explains: Why and how did the ancient Greeks create a culture that became central to the modern world? If Hellas had once been great, why was it no longer? Why, once fallen, was Greece so long and well remembered?

Those questions remain vitally important in the twenty-first century, and they can be answered. Hellas—the ancient Greek world that, even before the conquests of Alexander the Great, extended east into western Asia, north to the Black Sea, south to North Africa, and west to Italy, France, and Spain—was great indeed. Hellas was great because of a cultural accomplishment that was supported by sustained economic growth. That growth was made possible by a distinctive approach to politics.

CLASSICAL GREEK EFFLORESCENCE

In a spirited diatribe against the habit of dividing world history into dichotomous eras of premodern economic stagnation and modern growth, the historical sociologist Jack Goldstone has shown that a number of premodern societies experienced more or less extended periods of efflorescence—increased economic growth accompanied by a sharp uptick in cultural achievement. Efflorescence is characterized by more people (demographic growth) living at higher levels of welfare (per capita growth) and by cultural production at a higher level. It is not signaled merely by treasure heaped up in palace storerooms or by monumental architecture. Concentrations of state capital and grand building projects may or may not be accompanied by a dramatic rise in population, welfare, and culture.

Efflorescence is impermanent by definition, but some efflorescences are more dramatic and longer lasting than others. Modernity—the experience of the developed world since the early nineteenth century—is the most dramatic, but not (yet) the longest lasting efflorescence in human history. It remains an open question whether the historically exceptional rate of sustained economic growth that some parts of the world have experienced in the past two centuries is merely the most recent and biggest (by many orders of magnitude) of a long series of efflorescences—or whether “this time it’s different,” so that modernity represents a fundamental and permanent change of the direction of human history. Goldstone focuses on examples of efflorescence after 1400 CE, but he notes in passing that classical Greece was among a handful of societies that experienced efflorescence long before that date.3

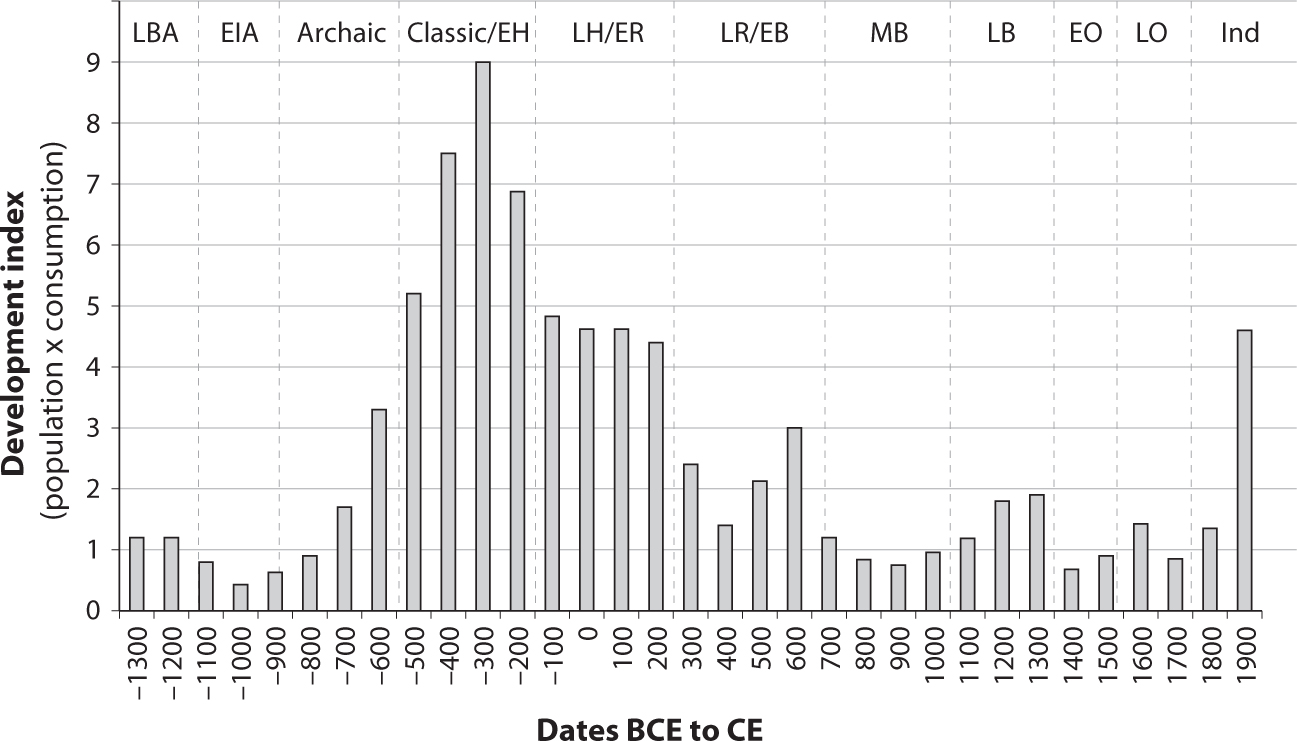

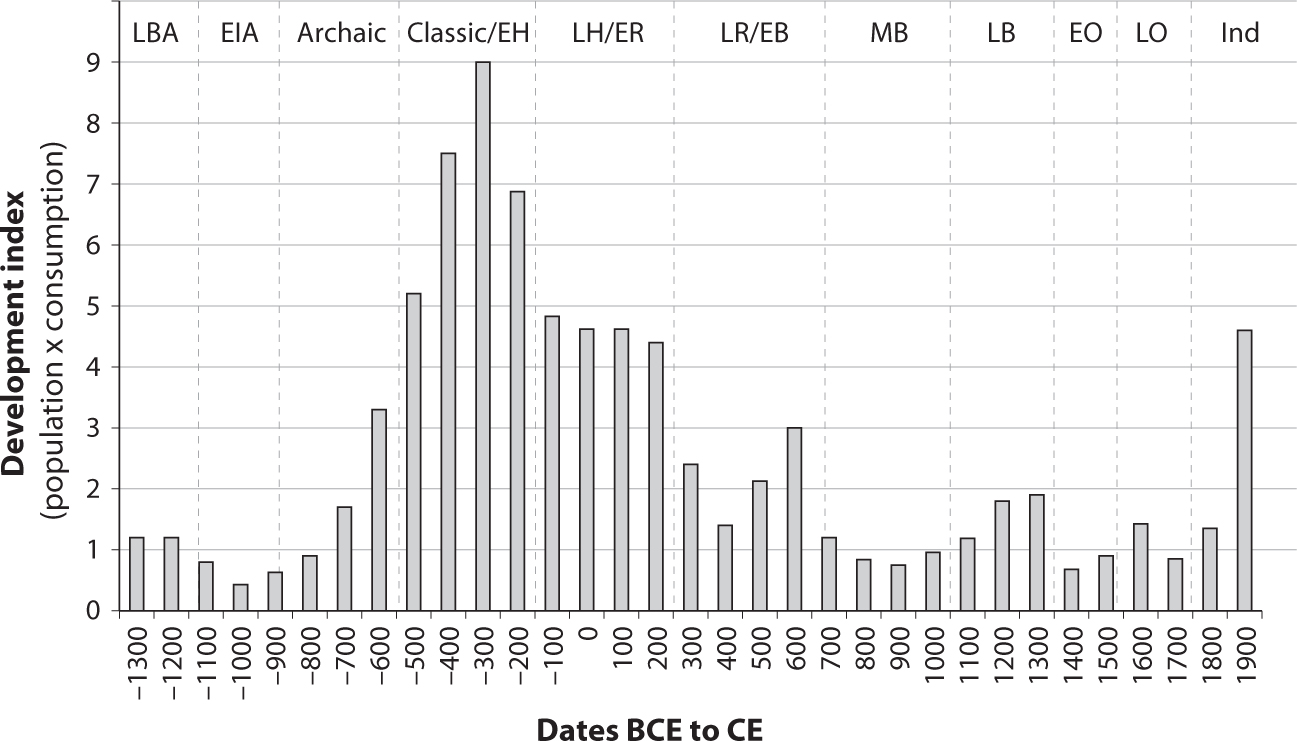

FIGURE 1.1 Development index, core Greece, 1300 BCE–1900 CE.

NOTES: The development index multiplies a population estimate (in millions) × median per capita consumption estimate (in multiples of bare subsistence). Population and consumption estimates are discussed in chapters 2 and 4, and broken out in figure 4.3. Core Greece = The territory controlled by the Greek state in 1881–1912 (Inventory regions 6–25: see map 1). LBA = Late Bronze Age. EIA = Early Iron Age. EH = Early Hellenistic. LH = Late Hellenistic. ER = Early Roman. LR = Late Roman. EB = Early Byzantine. MB = Middle Byzantine. EO = Early Ottoman. LO = Late Ottoman. Ind = Independent Greek state.

The Greek efflorescence that peaked by around 300 BCE lasted several hundred years, from the Archaic, through the Classical, and into the Hellenistic eras of Greek history. Figure 1.1, based on evidence presented in chapter 4, illustrates efflorescence in terms of economic development (measured by population and consumption) in “core Greece” from the Late Bronze Age to the dawn of the twentieth century. Because, by my definition, core Greece is limited to the territory controlled by the Greek state in the late nineteenth century CE, the graph understates the total population of the wider Greek world at the peak of the classical efflorescence by a factor of about three—so the chart captures only part of the rise. But the main implication is clear enough: it was not until the twentieth century that the number of people living in the Greek core, and their material welfare, returned to levels comparable to those achieved some 2,300 years before.4

The ancient Greek efflorescence was exceptional in premodern world history. While ancient Greek economic growth fell far short of the growth rates experienced by the globe’s most highly developed countries since the nineteenth century, the ancient Greek efflorescence was distinctive for its duration, its intensity, and its long-term impact on world culture. The Greek efflorescence took place in a social ecology of hundreds of city-states. “Greeks,” for our purposes, are the residents of communities that were, in antiquity, substantially (not homogeneously) Greek in terms of language and a distinctive suite of cultural features.5 While wealth and incomes remained unequal in those communities, a substantial part of the Greek population experienced relative prosperity. The growth of the Greek economy was driven, at least in part, by the ability of an extensive middle class to consume goods and services at a level well above mere existence.6

Ancient Greek society was unlike our modernity in important ways: Among other things, slavery was taken for granted and women never held political participation rights. Yet the most developed states of classical Hellas in some respects tracked conditions typical of developed modern states as late as the mid-nineteenth century. Residents of the most developed ancient Greek states experienced aspects of a precocious “modernity before the fact.” As Byron’s lines remind us, the classical efflorescence was not sustained indefinitely. Yet, by the same token, it was never forgotten.7

We can answer questions about Greece that remained mysterious for Byron because we have better data. We now know much more about ancient Hellas than he could have known. Happily for the contemporary investigator seeking to explain the changing fortunes of Hellas, a great deal of primary evidence for Greek history has come down to us from antiquity—it survived the fall for reasons we will explore in chapter 11. Moreover, from the age of Byron onward, classical Greece was such a hot field of inquiry that many of the Western world’s most brilliant intellects devoted their lives to investigating its every facet. After generations of exploration and reconstruction by historians and archaeologists, there is now an unrivaled historical record for the Greek world in the first millennium BCE.

Equally important, that massive and detailed record has been organized by encyclopedic projects and thereby made available for systematic analysis. The most important of these, for our purposes, is the monumental Inventory of Archaic and Classical Greek Poleis (hereafter “the Inventory”), compiled by an international team under the direction of the preeminent Danish historian of the Greek world, Mogens H. Hansen.8 The Inventory collects detailed information for 1,035 Greek states known to have existed in the extended Greek world, across 45 regions, during the 500-year period from the eighth through the later fourth century BCE. Each state has a separate entry and a corresponding inventory (i) number. These numbers (e.g., Athens = i361) help us to be clear about which Greek states are being discussed in the pages that follow (some Greek names are shared by more than one state, others are Anglicized in various ways). The 45 Inventory regions are illustrated in map 1.

Meanwhile, the archaeological and some relevant documentary evidence for the long history of the Greek world, from the Bronze Age to modernity, has been recently summarized and reassessed in a magisterial volume by John Bintliff of the University of Leiden. Bintliff’s detailed survey, which includes analyses of demographic change over time, enables us to assess the data for archaic and classical Greece against a much broader chronological context.9

The mass of quantifiable evidence assembled in the Inventory, and in other recent collections of data on Greek history, archaeology, and geography, has made it possible to employ the sharp analytical tools of contemporary social science when we seek to explain Greek history. By quantifying evidence, we can estimate the total population of the classical Greek world and of each of its regions. We can study comparative state and regional development across the Greek world, and we can compare the Greek world to other premodern societies. All of this comparison allows us to test competing explanations for the rise to greatness of Hellas, for its fall, and for its enduring influence. The data on which my statistics are based are publicly available at http://polis.stanford.edu.10

The twenty-first century has seen a renaissance in the study of ancient Greek and Roman economic history. Following a generation of scholarship grounded on the premise that a unitary “ancient economy,” lasting for millennia, was defined by a deep social structure inherently resistant to change, economic historians are now attempting to measure and to explain economic growth and decline in specific times and places within the premodern world. Much recent scholarship on Greek and Roman economies is predicated on the “new institutional economics” pioneered by the Nobel Prize–winning economist and political scientist, Douglass North and exemplified by recent work by the MIT and Harvard social scientists Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson. Their insistence that institutions (the “rules of the game”) and organizations (including, but not only, states), along with markets and networks, are fundamental determinants of economic change, grounds the arguments of this book. Scholars working in the institutional economics field seek, first, to develop a plausible theory of how specific institutions in a given society affected social choices, and then to test the theory against competitor theories by reference to a substantial body of evidence. At its best, institutional economics offers bold, new, and defensible explanations for important developments in historical and contemporary societies.11

Along with a theory of social choice under conditions of decentralized authority, and data for testing the theory, this book presents a new narrative history of Greek political and economic development. It does not pretend to offer a comprehensive account of every major event of ancient Greek history. I focus more on formal institutions and civic order than on the politically salient informal cultural performances that have been wonderfully elucidated by Sara Forsdyke, a classical Greek historian at the University of Michigan.12 I will have little to say about the Greek family, religion, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, childhood, aging, sport, or other important areas of social history. Other books, by scholars more knowledgeable than I, cover each of these areas well. Nor do I describe in detail the cultural accomplishments that so impressed Byron. While cultural accomplishment is an important part of the efflorescence I seek to explain, this terrain has been brilliantly elucidated by others. I assume that it is uncontroversial to say that in the areas of visual art, architecture, drama, historiography, philosophy (ethics, politics, epistemology, metaphysics, logic), and natural science (geometry, geography, astronomy, medicine), classical Greece provided enduringly important resources for world culture. Finally, although promising recent collaborations between historians and geneticists have demonstrated that, as a result of colonization and mobility, ancient Greeks had a profound and enduring impact on the genetic makeup of populations in the western, as well as eastern Mediterranean, I will not seek to address the genetic legacy of Hellas.13

My goal is to measure the classical Greek efflorescence and to explain how political institutions and culture enabled the Greek world to rise to greatness from humble beginnings, how the great states of Greece fell to a predatory empire, and how Greek culture was subsequently preserved for posterity.

SMALL STATES, DISPERSED AUTHORITY

After two centuries of intensive scholarly research and with the aid of the Inventory, we can now grasp, much more clearly than Byron or his contemporaries could have, the extent and development of ancient Hellas. First and foremost, it was a world defined by a startlingly large number of surprisingly small states—there were about 1,100 Greek states by the end of the third quarter of the fourth century BCE—when Aristotle was writing his masterpiece on Politics and his student, Alexander the Great, was completing the conquest of western Asia. The extended Greek world of city-states stretched from outposts in Spain and France, through southern Italy and Sicily, to the Greek peninsula; east and north to Thrace (modern Bulgaria), to the shores of the Black Sea and western Anatolia; then south to eastern and southern outposts in Syria and North Africa (map 1). By Alexander’s day, the total population of Hellas—that is, the residents of small states that were substantially Greek in language and culture—was in excess of 8 million people.14

Individual Greek states varied tremendously in their size and influence. Athens, Sparta (i345), and Syracuse (i47), which provide focal points for developing the ideas in this book, were among the largest and most influential states in Hellas. Athens boasted a territory of some 2,500 km2—about the size of Luxembourg or Orange County in southern California—and a population of perhaps a quarter-million people. A more typical Greek polis, Athens’ northwestern neighbor, Plataea (i216), had a territory of ca. 170 km2, with a population below 10,000. And a great many Greek states were considerably smaller than that. At the lower end of the range, Koresia (i493), the smallest of four poleis on the modest-sized (129 km2) island of Kea, possessed a territory of roughly 15 km2—about one-fifth the area of the island of Manhattan or one-seventh the area of Paris. Yet in important ways, the Greek states were peer polities, interacting with one another diplomatically, militarily, and economically as equals in their standing as states, if not in power, wealth, or influence.15

These small Greek states were city-states—in ancient Greek, poleis (singular polis). By Aristotle’s day, a polis was characterized by a well-defined urban center, typically walled, in which lived perhaps half of the polis’ population. The urban center was surrounded by a rural hinterland. The hinterland of larger poleis featured small towns, as well as villages, and farmsteads. Near the borders were pastureland and tracts of near wilderness. Boundaries between the many states of Hellas were quite clearly defined, although not always respected by neighboring states: Disputing borders was a major source of conflict between poleis, and wars among the Greek states were frequent. As a result of warfare, and of diplomatic negotiations carried out in the shadow of war, some poleis went out of existence altogether. Close to 100 Greek states, about one in ten of the known poleis, are known to have disappeared, through extermination or assimilation, by the time of the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE. Many other poleis were less than fully independent in terms of their authority to determine their own foreign policy. But, by definition, each polis had considerable local authority to set and to enforce the rules by which its residents lived.16

There have been dozens of small-state, “dispersed-authority” cultures in world history—prominently including ancient Renaissance northern Italy and the Hanseatic League of late medieval/early modern northwestern Europe. Other city-state cultures are documented in Europe, Asia, Africa, and the New World. When juxtaposed to “centralized authority” cultures—most obviously in the form of empires (imperial Rome, Han China), and nation-states (Europe after 1500)—that have tended to dominate the political history of the premodern world, these small-state cultures are sometimes disproportionately influential in terms of their long-term impact on world history. Examples of small-state cultures that “punched over their weight” include, in addition to the two examples above, the city-states of early Mesopotamia, which pioneered many of the basic elements of urban civilization, the commercial city-states of Phoenicia, and the Etruscans of northwestern Italy (see map 2).

Small-state, dispersed-authority systems can be compared to a natural ecology, characterized by a rich variety of plant and animal species, none of which is dominant. Large, highly centralized states more closely resemble the ecology of a modern large-scale factory farm, which efficiently produces great quantities of a single crop by eliminating diversity. Hellas was a strikingly extensive and long-lived small-state, dispersed authority culture—and it was by far the largest and the longest lived city-state culture in documented world history.

Among the central questions raised by ancient Greek history is how and why such an extensive small-state system persisted, in such a flourishing condition, for such a long time. In an inversion of, for example, European history from 1500 to 1900 or Chinese history from ca. 700 to 200 BCE, there were many more independent states in the Greek ecology by the height of the classical efflorescence than there had been several hundred years previously. Despite repeated attempts, no classical-era Greek city-state succeeded in creating a centralized empire (chapter 8). Why, during the era of efflorescence, did the many states of Hellas not consolidate into a unitary empire, on the model of Persia, Carthage, or Rome? Or, failing that, into several large competitor states, on the model of ancient Phoenicia, or Warring States China, or Europe ca. 1500–1900?17

All workable social systems are predicated on creating reliable forms of cooperation among an extensive population and then distributing the fruits of that cooperation across the population in ways that prevent the outbreak of catastrophic levels of violence. Centralized authority systems work according to the simple and powerful logic of command-and-control: Cooperation is achieved through obedience to a central coercive authority. With a unified authority structure capable of enforcing cooperation, and a distribution plan designed to ensure that those who are capable of destabilizing society through violence have no incentive to do so, conflict is effectively reduced.18

The basic logic of centralized authority has long been appreciated; Thomas Hobbes, in his great mid-seventeenth century work of political theory, Leviathan (1996), remains among the most astute and influential of its expositors. Hobbes famously argued that the choice faced by all societies is between a centralized authority system and the anarchy of “war of all against all”—a condition in which human life is inevitably, “poor, solitary, nasty, brutish, and short.” Although modern social scientists usually do not see the history of human development in such stark terms, the tendency to associate economic and cultural development with the emergence and persistence of highly centralized bureaucratic states remains pervasive, not least in discussions of premodern state formation.19

In a centralized system, people know just where they stand (or kneel) in a hierarchical social order, and that order determines who does what in the production of goods, and who gets what in the distribution of goods, services, and privilege. The system is centered on a ruler (or a small group of rulers), typically, in the premodern world, a monarch to whom divine or quasi-divine powers are attributed. Authority devolves from the godlike ruler through a pyramidal chain of authority. The residents of the state are the subjects of the ruler. Wealth and power are concentrated at and distributed from the center. Social privileges and access to important institutions (e.g., law, property rights) are determined by social proximity to the ruler. The pyramidal organizational structure allows commands to be passed down from the apex of the hierarchical system to its base, and thus, ideally at least, everyone knows exactly what is expected of him or her and what he or she can expect to get in return. As long as those expectations are met, and no one who could disturb the order of society has reason to do so, the system is stable.

The great majority of the ruler’s subjects are situated at the base of the pyramid; they provide the productive labor that sustains the system. They take orders and pass most of the surplus to those above them, in the form of rents or taxes. With most of his or her surplus appropriated, the median individual thus lives quite close to the level of bare subsistence. Because wealth is concentrated at the center and at the top, and because conflict is suppressed, a well-organized centralized state can sustain both a bureaucracy and military forces—thereby allowing the ruler to manage the state, pay off his or her coalition, and make war against rivals. An especially large and successful centrally organized state eventually subordinates its local rivals and thereby becomes an empire.20

How premodern small-state systems function is less well understood. How can a system in which authority is dispersed create adequate opportunities for cooperation at scale, redistribute the fruits of cooperation in ways that promote stability, and thereby accumulate resources sufficient to preserve itself over time? Why do small-state systems not quickly collapse into Hobbes’ “war of all against all”? The puzzle of how dispersed-authority systems are sustained is exacerbated when the stakes are high: How could a small-state system like Greece survive, much less flourish, when it was endemically threatened by a large, well-managed, and predatory empire like Achaemenid Persia?

In small-state systems authority is decentralized. There is no overarching hierarchy, no central point at which wealth and influence can readily be concentrated. As a result, as Hobbes confidently predicted, conflict remains endemic within the system. The many wars between the small states of ancient Greece are typical of other dispersed-authority ecologies, for example in early Mesopotamia, Warring States era China, or Renaissance Italy. Nor is the answer to the question of how small-state systems manage to flourish necessarily to be found in local centralization. Individual states within a small-state system may be ruled by kings and their elite coalitions. But a number of small-state systems included states with republican, citizen-centered, forms of government.21

In the most influential states of Hellas, authority was widely distributed, not only at the level of the multistate ecology but also at the level of the individual state. In the typical Greek polis, the adult male native residents were citizens, rather than subjects. In a Greek democracy, a form of government that became increasingly prevalent in Hellas after the late sixth century BCE, free and politically equal citizens collectively governed themselves. While political authority was concentrated in state institutions, power was dispersed among institutions; many citizens held offices and participated actively in both legislation and adjudication. Once again, in an inversion of the experience of state-building in early modern Europe, where, by the seventeenth century, centralized royal authority had succeeded in weakening the power of deliberative institutions, individual Greek states and the ecology of states became more democratic during the era of classical efflorescence.22

Some of the most influential and most democratic of the individual Greek states diverged markedly from the model of social order that political scientists Douglass North, John Wallis, and Barry Weingast call the “natural state”—and which they argue has been the basic form of centralized state-level social order throughout most of recorded human history. The natural state is ultimately based on domination and governed by a leader and the members of his or her elite coalition. Leader and elites cooperate to create and sustain, in their own interest, a system of production, distribution, and conflict suppression.

Natural states are not democratic; they seek to restrict access to institutions; they tend not to extend rights to secure possession of property or other privileges beyond the small and tightly patrolled ambit of the ruling coalition. But, so long as it distributes the fruits of cooperation to the right people (i.e., those with potential for violence) in the right proportion (the greater the potential for violence, the bigger the share), the natural state can be very stable. The unitary empire is one historically important kind of natural state, but the natural state, as a basic form of social order, can be scaled up or down.

While economically inefficient, when compared to modern open-access orders, the emergence of ever-larger limited-access states with ever more highly centralized authority, has, historically, been associated with political and economic development. In the light of the stubborn refusal of the Greek small-state ecology to coalesce into either an empire or a few large states ruled by strong leaders and narrow elite coalitions, the greatness of ancient Hellas becomes more mysterious. It also becomes more interesting to those who prefer democracy, freedom, and dignity—even in the incomplete form in which they were manifest in ancient Greece—to the kinds of domination typical of most premodern states.

Ancient Greek history points to a possible alternative to the dominant narrative of political and economic development, based primarily on the history of early modern Europe, as “first (and necessarily) the big, centralized, and autocratic state, and only then (sometimes) democracy and wealth.”23

SPECIALIZATION, INNOVATION, CREATIVE DESTRUCTION

One of the keys to unlocking the puzzling success of the polis ecology is economic specialization and exchange. In the Greek world, as in other times and places through history, specialization was based on developing and exploiting a local advantage, relative to other producers, in the production of some valued good or service. Assuming that costs of transactions are low enough to make exchanges mutually beneficial, specialized goods (e.g., olive oil, fine pottery) and services (of, e.g., mercenary soldiers, poets) are distributed through networks of exchange so that the products of specialized endeavor become available across a large ecology of diverse local specialists.

The powerful role that specialization and cooperative (mutually beneficial) market exchange can play in promoting economic growth was recognized and described in the later eighteenth century by Adam Smith in the Wealth of Nations (1981 [1776]). Greek specialization was often more horizontal (workshops and individual craftspeople specializing in the production of specific goods) than vertical (factories employing specialist labor at each phase of a production process). And ancient Greek writers never produced a work of economic analysis to rival Smith’s hugely influential book. Yet it is now very clear that specialization and exchange flourished at different levels in Hellas and, moreover, that the core principles of relative advantage and rational cooperation were understood by the ancient Greeks.24

Individual Greek states developed specialties based on natural resource endowments relative to other poleis—for example, the fine white marble at the Aegean island-state of Paros (i509), or favorable wheat-growing conditions in the cities of southern Italy and Sicily (chapter 6). Other poleis developed advantages by perfecting industrial processes—e.g., manufacture of painted vases and warships in Athens (chapters 7 and 8). Competition and conflict among poleis served to sharpen the recognition of the necessity of exploiting relative advantages, whereas a recognition of the value of lowering transaction costs pushed in the direction of opening access and interstate cooperation. Meanwhile, within poleis, individuals specialized in a wide range of endeavors. Within a given specialization, individuals competed with one another (“potter vies against potter,” as the poet Hesiod remarked in his Works and Days, line 25), once again sharpening the recognition of the value of relative advantage and leading to the deepening and multiplication of subspecializations.

The upshot of the cycle of competition, specialization, and cooperation in creating conditions for mutually beneficial exchange was a high premium on innovation and entrepreneurship. Innovation—the process whereby novel solutions were developed to meet new requirements or existing needs—in turn drove a dynamic that the Austrian-American economist and political scientist Joseph Schumpeter famously described as “creative destruction”: Advances in artistic and productive technique drove out earlier techniques; new institutions marginalized traditional forms of social organization; poleis that exploited relative advantages absorbed their less innovative rivals, while new poleis were continuously being created on the ever-expanding frontiers of Hellas.25

The products of local specialization were readily distributed, within poleis, across the extensive small-state ecology, and then beyond the Greek world, through increasingly dense networks of exchange and interaction. Local markets grew into regional markets, and some poleis succeeded in creating major interstate emporia where goods from across the Mediterranean and Black Sea worlds could be bought and sold. Experts in various arts and crafts migrated to new homes and established new centers of specialized production. Meanwhile, the costs of transactions were driven down by continuous institutional innovations, notably by the development and rapid spread of silver coinage as a reliable exchange medium, the dissemination of common standards for weights and measures, market regulations and officials to enforce them, and increasingly sophisticated systems of law and legal mechanisms for dispute resolution. Competition and conflict between poleis and between the Greeks and their non-Greek neighbors temporarily disrupted local networks of exchange. But those disruptions only served to motivate poleis and individuals to seek out new markets for their goods and services, to deepen and broaden their exchange networks, and to develop cooperative solutions whereby conflict could be reduced or at least rendered less disruptive.

Specialization in production of goods and exchange of the goods and services produced by specialists are common features of complex societies. If we are to explain the efflorescence of Hellas, we need to answer the question of why and how, in the Greek world, specialization and exchange achieved such high levels, and how they become so strongly intertwined with continuous innovation and creative destruction—thereby driving a sustained level of economic growth that proved high enough to overcome the costs of conflict among many small states.

Geography and climate are certainly one part of the answer. Specialization and exchange in the Greek world were encouraged by distinctive geographic and climatic features of the Mediterranean basin, a region characterized by a great variety of microclimates, diverse soil conditions, and unevenly distributed concentrations of natural resources. Moreover, the geophysical conditions that were common to the states of Hellas disfavored large-scale standardization directed from a distant imperial center. Agriculture in Hellas was primarily based on sparse but adequate rainfall in relatively small valleys and terraced hillsides, rather than large-scale irrigation in extensive plains. Unlike Mesopotamia, Egypt, or China, for example, Hellas had no great river systems that could be cooperatively managed by a centralized bureaucracy so as to create the conditions favorable to maximizing the production of a few staple crops. The geographic and climatic conditions typical of Hellas were conjoined with a highly variegated coastline and a seascape featuring many islands, which facilitated overseas trade and lowered the costs of transport. Nearby empires (Persia) and less developed societies (Thrace, Scythia) provided ready markets for the goods and services produced by Greek specialists; those societies in turn produced goods (notably food and slaves) imported by the Greeks.26

These exogenous factors, important as they were, ultimately fail to explain how specialization, innovation, and creative destruction drove the classical Greek efflorescence. That failure is manifest simply by comparing classical Hellas to earlier and later eras in Greek history. The Greek world remained geophysically similar over the millennia, and Hellas has always had more and less developed neighbors. And yet, as Byron believed and modern scholarship confirms, the classical-era efflorescence of the first millennium BCE was unique: Neither before nor after the first millennium BCE did Greece experience a world-class efflorescence. The geophysical and climatological conditions of the Mediterranean world obviously permitted high levels of economic growth and the distinctive forms of cultural flourishing that characterized classical Greece. But if those factors were primary drivers of Greek greatness, we would expect greatness to recur over time.

Natural conditions favoring specialization and exchange were reinforced by favorable cultural conditions: As the Greek polis system expanded in the eighth century BCE and thereafter, a common language and other commonly shared cultural attributes (religion, diet, marriage practices) lowered the cultural barriers to efficient exchange and thereby lowered transaction costs. But the dynamic expansion of the Greek world is one of the remarkable features of the Greek efflorescence that we are seeking to explain. Although there was no doubt a degree of productive feedback in the system, an expanding common culture cannot at once be an adequate cause and a primary effect of Hellenic greatness.27

KNOWLEDGE, INSTITUTIONS, CULTURE

In order to understand the relationship between specialization, innovation, creative destruction, and the classical Greek efflorescence, we will need to step back from Adam Smith’s early industrial-era conception of the relationship between specialization and economic growth to consider the roles played by individual exchanges of information and by the aggregation of diverse forms of useful knowledge. Smith’s prime example of vertical specialization was a pin factory. Smith vividly illustrated the advantages to be reaped from specialization by comparing the output of an efficient factory, in which workers specialize in different parts of the production process, to the output of pins that could be expected from that same number of workers if each were making pins on his or her own, from scratch. Knowledge is certainly part of Smith’s story: Someone with the relevant knowledge of how pins are made needs to set up the factory. But diverse forms of local knowledge that might be possessed by and exchanged among the workers is irrelevant—each needs to be properly trained in his or her specialized job; the rest of what he or she happens to know is not a positive factor in the performance of the factory—and indeed it may be thought of as a liability.

The idea that specialization implies that the information and knowledge component of production ought to be separated from its manual part was deeply embedded in industrial-era thinking: Henry Ford, who famously employed Smith’s core insight to create a sophisticated industrial production system for automobiles, is said to have bemoaned the fact that when he hired a pair of hands, they came with a head attached. The conjunction of specialization of production and centralization of the management of knowledge for rational planning was one of the hallmarks of the industrial era of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This conjunction might help us to understand how highly centralized societies function, but it does not explain the powerful role of specialization, innovation, and creative destruction in the decentralized world of ancient Greece.28

To explain the world of the Greek poleis, we need to move forward in time, beyond the industrial era into the contemporary world of self-consciously knowledge-based enterprises. It is now widely understood that exchanging and aggregating diverse and dispersed forms of knowledge is a key factor to the success of contemporary purposeful organizations—whether for-profit business firms (professional service and software firms are canonical examples) or not-for-profit organizations of various kinds (e.g., modern research universities).

The challenge of the knowledge-based enterprise is not detaching hands from heads à la Ford but rather providing conditions in which the different forms of useful knowledge embedded in many minds will be voluntarily disclosed and effectively organized so as to address the problems that must be solved in order for the organization to further its purposes. This system typically requires creating conditions of mutual trust and a sense of shared purpose. Those conditions are in turn facilitated by the development of the relevant forms of common knowledge—that is, the situation in which person A knows something, and B knows that A knows it, and A knows that B knows that A knows it … and so on. Under conditions of common knowledge, people are better able to align their efforts. Under conditions of effective aggregation of diverse types of knowledge, the group may effectively be wiser than any of its individual members, and important innovations may be the product of group effort rather than individual genius.29

When common knowledge and dispersed and diverse knowledge are brought together under the right conditions, and when the results are codified, the effect is to increase over time the total stock of useful knowledge. By “the right conditions,” I mean conditions of shared interests and purposes, rational trust, and fair competition (level playing field, equitable rewards), such that people voluntarily choose to share what they know with others in their organization in a timely and appropriate manner, thereby allowing for their knowledge to be applied to complex problems—that is, to problems that demand for their solution many different kinds of knowledge.

Moreover, under the right conditions, individuals voluntarily choose to deepen their own special knowledge and sharpen their skills: In other words, they invest in the development of their own relative advantages and turn those relative advantages to cooperative, prosocial ends. This process of building human capital and social capital is manifest in the operations of modern science and engineering and is therefore at least indirectly responsible for, inter alia, the dynamic growth of modern economies. As the managers of modern organizations have found, however, getting the conditions right is not easy. In the Greek world, the right conditions were achieved and sustained by innovative political institutions and a robust civic culture.30

The greatness of the Greek world that inspired Byron and so many other Hellenophiles before and since was driven by a set of political institutions and a civic culture that are historically rare—indeed, at the time of their emergence in Hellas, those institutions and that culture were probably unique. The political institutions found in many citizen-centered Greek states, but especially in democratic states and most especially in democratic Athens, put specialization and innovation on overdrive because those institutions and that culture encouraged individuals to take more rational risks and to develop more distinctive skills. They did so by protecting individuals against the theft by the powerful of the fruits of risk-taking and self-investment.

Today we typically think of such protections as “rights.” The Greeks did not have a fully modern conception of universal human rights. But they did develop a strong tradition of civic rights—immunities against arbitrary action by powerful individuals or government agents. These immunities guaranteed for each citizen the security of his or her body against assault, the security of his or her dignity against humiliation, and the security of his or her property against confiscation. It is important to remember that many residents of a polis were not citizens and so were not full participants in the regime of immunity and security. And yet, in some of the most highly developed poleis, these immunities were extended to at least some noncitizens.

Citizens, who themselves collectively held the authority to make new institutional rules, in turn were more likely to trust the rules under which they lived to be basically fair. Judgments, by citizens who were empowered (by vote or lottery) to settle disputes and to distribute public goods, were made on the basis of established and impartial rules, rather than on the basis of patronage or personal favoritism. With these guarantees in place, and because successful innovation was well rewarded, individuals had strong incentives to invest in their own special talents, to defer short-term payoffs, and to accept a certain level of risk in anticipation of long-term rewards. The end result of those rational choices, made by individuals in many walks of life in the common context of clear rules and a level playing field, was a historically unusual level of sustained economic growth and an equally unusual rate of sustained cultural productivity and innovation.31

Attention to the political foundation upon which the growth of human and social capital was predicated helps to solve an apparent paradox: In classical Hellas the benefits of specialization were reaped in such abundance because specialization did not go “all the way down” in the ways that are typical of centralized authority systems. Much of the work of governance in a democratic polis was done by amateurs—by citizen-farmers and citizen-shoemakers, and citizen-soldiers who chose to dedicate themselves, part-time, to the tasks of rule-making, judgment, and administration. The costs associated with amateurs spending part of their productive energies on the business of governance (loss of productivity in the nongovernment sector, steep learning curves) were more than made up for by the benefits that arose from the assurance that the incentives of decision-making bodies were aligned with those of the citizen population.32 Further benefits accrued from exchanging and aggregating diverse local knowledge resources and from a rising stock of social and human capital, as citizens came to trust in one another and in a political system that they collectively created and collectively managed.33

The logic of centralized authority places specialization at the heart of the system of social order: The rulers are specialists in ruling, and no one who is not a specialist in ruling has a legitimate role to play in governing the state. Rulers are supported by a military class of violence specialists, who monopolize the use of force and support the rulers in exchange for a share of the rents extracted from the rest of society. This situation of specialist-rulers was certainly conceivable to the Greeks. Indeed, “each does his own specialized job and strictly avoids interfering in the specializations of others” is the primary principle of justice in the most famous work of Greek political philosophy, Plato’s Republic. In Plato’s ideal state, that principle leads inevitably to the absolutist rule of philosopher-kings, who are described as perfectly and uniquely competent expert rulers. The philosopher-kings are supported by the auxiliary guardians, specialists in violence who enjoy a monopoly on the legitimate use of force, both internally against rule-breaking locals and for purposes of external warfare.

In practice, however, the Greek poleis rejected this kind of hyperspecialization at the level of governance and violence. In most Greek states, it was the citizens who were the warriors: either infantrymen or rowers in warships. Violence was a specialization, but not of a small military elite. Meanwhile, the embrace of collective self-governance by amateurs and the rejection of governance by experts alone played a fundamental role in making the Greek efflorescence so extraordinary, so durable, and so memorable. This embrace of amateurism did not mean that expert knowledge was excluded from the processes of decision and judgment in the making of public policy. But it did mean that no individual or small group could legitimately monopolize authority to govern the state. As we will see, when the right institutional and cultural conditions had been achieved, the many actually did prove to be adequately wise.34

The historically distinctive Greek approach to citizenship and political order, and its role in driving specialization and continuous innovation through the establishment of civic rights, alignment of interests of a large class of people who ruled and were ruled over in turn, and the free exchange of information, was the key differentiator that made the Greek efflorescence distinctive in premodern history. The emergence of a new approach to politics is what propelled Hellas to the heights of accomplishment celebrated by Byron. By the same token, however, the dynamic combination of political institutions, innovation, specialization, and low-cost distribution of goods and services across an expanding exchange network helps to explain how an authoritarian ruler was able to terminate the era in which major city-states set the course of Mediterranean history.

FALL AND PERSISTENCE

The dynamic process of creative destruction, driven by specialization and knowledge-based innovation, was central in the rise of the Greek world. It was also a key factor in the defeat of a coalition of independent poleis of mainland Greece by imperial Macedon in the later fourth century and in the subsequent conquest of the whole of the Greek world by imperial Rome in the second century BCE. The fall of most of the great Greek city-states from their dominant position in Mediterranean affairs was precipitated, at least in part, by the successful adaptation of Greek innovations by some of the Greeks’ neighbors.

Among the most notable products of Greek specialization in the fourth century BCE were new forms of expertise, notably in warfare and in state finance. While developed within a civic context, to further the purposes of Greek city-states as civic communities, military and financial expertise proved to be readily exportable. Relevant forms of expertise migrated across the borders between poleis—but also outside the classical world of the poleis, to emerging states at the frontiers of the Greek world. In the fourth century BCE, certain of these states self-consciously adopted products of Greek culture and adapted them to the expansionist needs of centralized authority systems. By the middle decades of the fourth century BCE, the kingdom of Macedon had proved the most successful of these “opportunist” states.35

In the Macedon of King Philip II (who reigned 359–336 BCE) and his son Alexander III (“the Great”: 336–323 BCE), Greek expertise in finance and warfare were conjoined with ethnonationalism, rich natural resource endowments, and a level of military and organizational skill that may legitimately be described as genius. The result was the emergence of state military capacity that was unequaled in the prior history of the Mediterranean or west Asian worlds: In the course of a single human generation, Macedon conquered not only the poleis of mainland Greece, but also the vast Persian Empire. Rome later proved spectacularly adept at borrowing expertise and technology from its various neighbors, including the Greeks, and putting those elements together into a highly effective military and administrative system. That system eventually allowed the Romans to govern an empire of some 75 million people that encompassed much of Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa.

If full independence of most major Greek states was ended by the Macedonian and Roman conquests, the classical economic and cultural efflorescence continued into the postclassical era as a result of an equilibrium struck between ambitious Hellenistic monarchs and the city-states within their kingdoms. After Alexander’s death, the sprawling Macedonian empire was carved up by Alexander’s most competent lieutenants. They quickly found in the polis system the economic and social underpinnings for their own newly created kingdoms. In the administrative systems perfected in the most advanced poleis, they found some of the tools that allowed them to manage their kingdoms.

The early Hellenistic kings often acted as predatory warlords, but the fortified, federalized, and democratic Greek poleis proved to be hard targets. The kings were constrained to allow considerable independence to the city-states and to tax them at moderate rates. Democracy became more prevalent than ever in the Greek world; public building boomed; science and culture were codified and advanced. The perpetuation of efflorescence in the Hellenistic era, long past the moment of political fall, made possible the “immortality” of Greek culture.36 The material conditions of non-elite Greeks and the population of core Greece declined after the consolidation of the Roman imperial order and fell precipitously after the collapse of the Roman Empire. But by then Greek culture had been codified and was so widely dispersed that much of it survived—enough for Byron to admire and for us to explain what made it possible.