GOLDEN AGE OF EMPIRE, 478–404 BCE

PREEMPTIVE WAR

In 478 BCE, as they surveyed the wreckage of their once-beautiful city, the Athenians reckoned the cost of victory in the Persian wars. There was much to celebrate: The bulk of the population had survived, evacuated in advance of the Persian attack to safe havens in the Peloponnesus. The bold choice of the young democratic regime to fight at sea had been vindicated. The tenuous alliance with Sparta had remained intact for the duration of the war. Athens’ reputation had grown. Along with the Spartans, the Athenians were honored at Delphi by their fellow Greeks as having contributed decisively to the victories on land and sea. A great bronze tripod monument in the form of intertwined snakes had been inscribed with the names of the states that had defied the Persians. Punishment had been and would be meted out to Greeks who had too eagerly embraced the Persian side.1

On the other side of the ledger, Athens’ losses, collective and individual, were profound. Many good men, hoplite infantrymen and rowers in the fleet, had died in battle; the elders who had made a desperate stand on the acropolis had been massacred. The urban center had been twice occupied by the invaders and twice looted and sacked, its temples and sanctuaries burned. The dozens of marble statues and other dedications that had graced the peak of the Acropolis had been defiled; they were tossed into a heap and buried. Sacred buildings were deliberately left in ruins as a reminder of Persian sacrilege. Towns in the countryside had been plundered. Agriculture, trade, and industry were disrupted. It would be a full generation before the Athenian mint would be ready to return to full production of silver coins.2

Worse yet, in 478, there was little reason for anyone in the Greek world to believe that the Persian threat had been eliminated by the victories at Salamis, Plataea, and Mycale. With the exception of the Aegean islands and the Greek cities on the south coast of Thrace and along the western coasts of Anatolia, Persia’s empire was intact. Persia still controlled vast capital resources and a huge population. The Persian Great King had made two serious attempts to conquer mainland Greece and was known not to tolerate failure. There was every reason for the Greeks to suppose that he would try again.

The Spartans had lost soldiers at the land battles of Thermopylae and Plataea, but their territory was untouched by the war. They had gained in prestige from their military leadership in the successful operations, and they regarded themselves as the natural leaders of Hellas. In what must have seemed to many Athenians a blatantly self-seeking ploy to extend their authority and to weaken rival states in central Greece, the Spartans now proposed that no Greek city north of the Isthmus of Corinth should be fortified—ostensibly to deny the Persians a base of operations when they next invaded. Returning to a plan that they had urged after the pass at Thermopylae had been turned in 480, Sparta proposed constructing a defensive wall across the isthmus—a plan that would explicitly sacrifice all Greek poleis north of the Peloponnese, including, of course, Athens (Thucydides 1.90).

Herodotus (7.139.3) had mocked Sparta’s earlier isthmus wall plan as strategically absurd (the Persians could readily use transport ships to land expeditionary forces south of the wall). Moreover, it did not take strategic genius to recognize that the plan played directly to Sparta’s relative advantage in military operations. Without urban fortifications, the states north of the isthmus would be endemically vulnerable to the Peloponnesian League armies, led by Sparta’s crack army of hoplite warriors. The Spartans, backed by the allies, were formidable in open-field battle but had no deep experience in siege operations. Without fortifications, Sparta’s rivals were much more vulnerable to coercion.3

Rejecting the Spartan plan, the Athenians quickly threw a circuit wall around their city, employing as some of their construction materials rubble from public buildings wrecked by the invaders. For the Athenians, the strategic question was not how to fight the Persians once they returned but how to preempt their return. Sea power was the key. The operations of the recent wars had demonstrated with stark clarity the essential role played by sea power in Persia’s capacity to invade Greece in force. The first attack on the mainland, in 490, had come by sea, across the Aegean. The second attack, in 480, had come over land via Thrace and Thessaly, but the size and complexity of Persia’s land forces required massive and continuous resupply by sea. The army was much too large for the invaders to count on “living off the land” by commandeering local food supplies along their route. So long as the Greeks had a credible navy, Persian supply ships (in the form of unarmed sailing vessels), upon which the invading army depended, had to be protected by Persian warships (oared galleys).4

The Greek naval victory at Salamis in 480 had turned the tide of the war by putting the Persian overseas logistical operation at risk. Without naval supremacy, the Great King had been constrained to evacuate the bulk of his army (along with himself). The Persian army that fought at Plataea in 479 was only a fragment of the original invasion force—albeit it was composed of elite troops and well led by top Persian commanders. The naval victory at Mycale had temporarily knocked out the bulk of the Persian navy. But with its store of treasure and a huge population that included many with experience in naval operations, the Persians could soon be ready to put a new naval force into the Aegean from bases in Phoenicia, Cyprus, and Egypt. Unless, that is, someone stopped them.

The Athenians had a plan for how to do that. Their own navy of triremes was largely intact. Moreover, the victory at Mycale had liberated the Greek poleis of the Aegean islands, southern Thrace, and western Anatolia. Whether they welcomed the liberation or not, the residents of these Aegean, Thracian, and Anatolian poleis knew that if the Persians returned, the king would be likely to take vengeance upon them as traitors to the Empire. As the hapless residents of Eretria and Miletus had learned, “Great King of Persia as taker of vengeance, in the name of god, against despicable traitors” was a central part of Persian royal ideology. No doubt there was a range of opinion among Persia’s former subjects about the costs and benefits of having been part of the Persian Empire. While some former subjects certainly longed to be free of Persia (Herodotus 8.132), being subjects of the empire had certainly offered advantages for others. But with the Great King absent and assumed infuriated, and with the Athenians and Spartans in no mood to brook any expression of pro-Persian sentiment, the citizens of the liberated Greek states now had strong reasons to cooperate in a plan that would prevent a Persian reconquest.5

With these factors in mind, the Athenians proposed their plan: A new anti-Persian alliance, extended in membership and in duration, would be formed under the same joint Spartan–Athenian leadership that had brought victory in the recent war. Its goal would be to keep naval pressure on the Persians, through privateering and preemptive attacks on any organized force of Persian warships that dared show itself in Mediterranean waters, thereby preventing the reemergence of a Persian military presence substantial enough to threaten any part of the extended Greek world. But the Spartans demurred, as they had before in the face of Gelon of Syracuse’s offer to support the eastern Greek cause against Persia at the price of his own participation in leadership—or at least they dragged their feet for so long that the Athenians proceeded without them.

Sparta’s hesitancy to join in the naval confederation plan was determined at least in part by a path dependency—the constraint of current choices by past decisions—arising from their prior commitment to specialization in land warfare. Despite the success of Spartan naval commanders in the later phases of the war against Persia, seaborne operations were not Sparta’s strong suit: Warships required big capital outlays and large crews of reliable men who were not needed for hoplite service. Sparta had neither: Those who were reliable were needed as hoplites; those who were not needed as hoplites were unreliable.6

Moreover, the Spartans needed to keep most of their military forces relatively nearby if they were to maintain escalation dominance—the capacity to win wars at increasing scale (“if the conflict escalates, we still win”)—over both the numerous helots and potentially restive Peloponnesians.7 Finally, to ice the cake of their disapproval, a Spartan king who had been posted in the north Aegean as part of the anti-Persian operations late in the war had gone seriously off the rails: Reportedly, he had conspired with the Great King of Persia. Whatever the truth of that accusation, he had certainly acted in a very un-Spartan fashion, dressing and feasting in the Persian manner and surrounding himself with a foreign bodyguard. This was clear enough evidence for the Spartans, had any been needed, that the social panopticon of the Lycurgan system was essential for maintaining Spartan society in its current equilibrium.

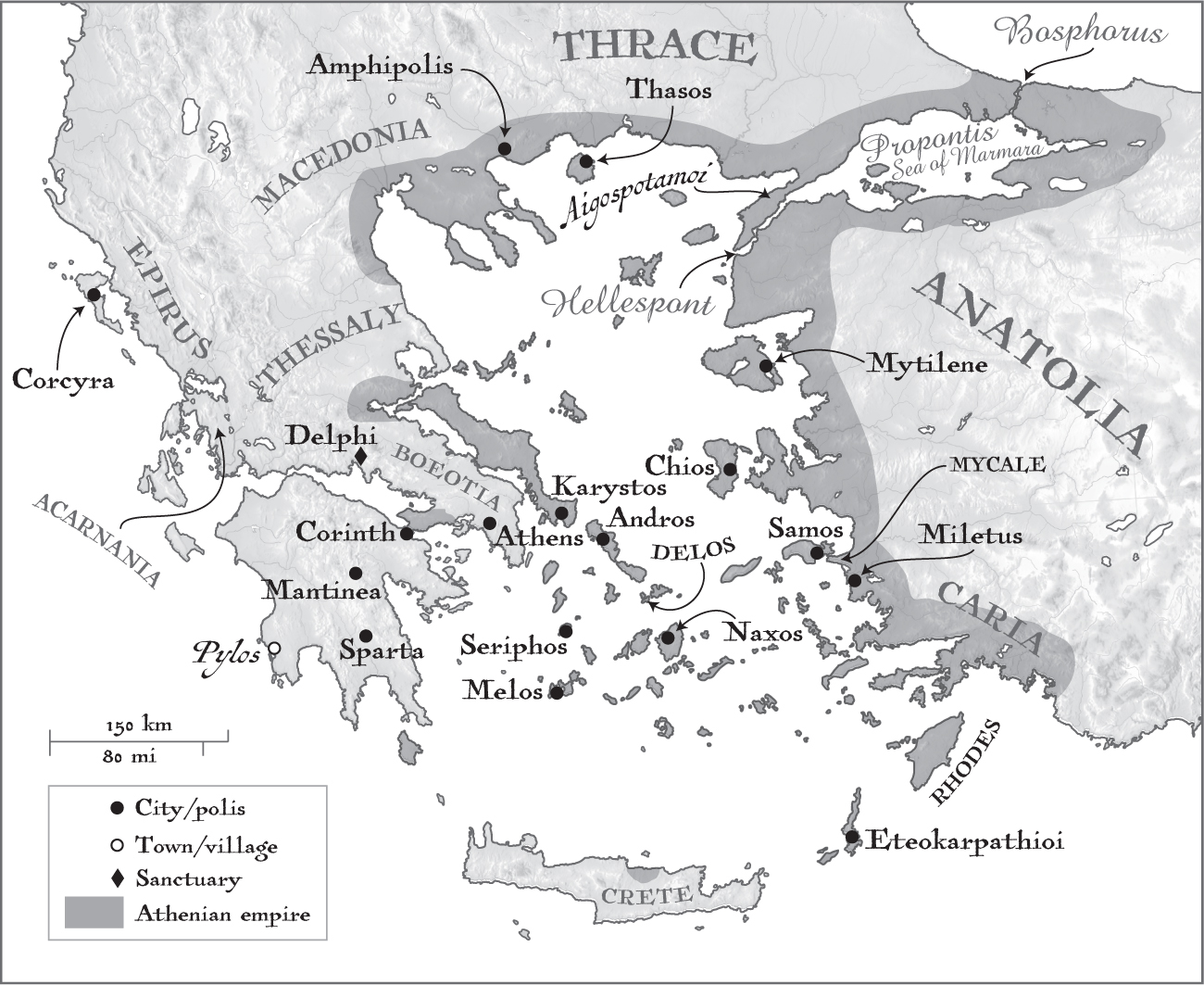

So Athens was left to implement the anti-Persian confederation on its own. Most of the Aegean and coastal Anatolian Greek states were quickly signed up, and other states joined, voluntarily or otherwise, in the years to come. The result was the Delian League (map 7), named after the tiny Aegean island (later a Roman-era trade center and notorious slave market) dedicated to Apollo. Here, at a site especially sacred to the Ionian Greeks who were, ethnolinguistically, the majority of the League’s membership, a common treasury was to be established and league meetings would be held to discuss policy. The league’s stated purpose was to build and man enough warships to maintain active naval patrols in the Aegean throughout the sailing season—winter operations were for the most part out of the question, due to weather.8

But who would build and who would man the warships? Many of the member states of the league were very small. Most had neither the local expertise nor the facilities to build, row, or store (in the off-season) the state-of-the-art trireme warships that would be the ships of the line in all major anti-Persian operations. Athens had both growing expertise and experience in ship-building and a large population with a proven willingness to take to the sea in force. But the post-Persian War Athenians were obviously in no condition to pay for all necessary work themselves—Athens had taken a big hit in the war and already had heavy calls on whatever funds they could raise from their own pockets.

Expost, the solution was obvious: Athenians, with their recognized specialization in naval architecture and naval warfare and a manpower base to match, would build and operate most of the ships. Several other major poleis would contribute their own ships and men. But most of the members of the league would contribute money instead. An Athenian named Aristeides came up with the schedule of payments—in ships or silver—for each polis in the league, famously earning himself the nickname, at least among Athenians (Plutarch Life of Aristeides 7.6), of “the Just” for the equitability of his arrangement.

The agreement that brought the new confederation into existence was sealed with solemn oaths that would be kept, it was promised, until iron ingots, ceremonially thrown into the sea, floated. The new league began operations immediately, reducing several important Persian strongholds in the north Aegean and forcing the south-Euboean polis of Karystos (i373), which had been pro-Persian during the war, into the league. The league’s first decade was capped by a major victory in 469 BCE at the Eurymedon River on the southwest coast of Anatolia. The strategic plan was working: Persia had not come back. And meanwhile, a newly invigorated Aegean exchange economy was emerging. It was dispersed across many markets but more focused than before on Athens and its port at Piraeus.9

TROUBLE WITH SPARTA

There was, however, trouble almost from the beginning. Insofar as Persia was a real threat, the security provided by the Delian League against any potential resurgence by Persia was a nonexcludable public good, in the sense that every Greek state potentially vulnerable to Persian predation benefited from the league’s activity in preventing Persian operations. Those states that contributed nothing to the effort to muzzle Persia reaped just as much of the benefit as did those that contributed much. Moreover, in an easily conceivable counterfactual, if Persia were someday to defeat the forces of the league and thus retake the eastern Aegean, those states that had refused to participate in anti-Persian military actions might be spared the full force of the Great King’s righteous vengeance. Thus, there was a strong incentive for each of the league states to free ride on the security conditions produced by the collective action of the others, by failing to contribute to the league. If one state were successful in this self-interested strategy, it could precipitate an emulation cascade of defection, dooming the league and leaving Athens, and all Hellas, vulnerable to Persia.

The wealthy Aegean polis of Naxos (i507: size 4, fame 4) was the first Greek state to attempt to defect from the league. The response was swift: Naxos was besieged by an Athenian-led naval group and forced back into compliance. The pattern of attempted defection (through nonpayment of dues) followed by efficient reprisal was to be repeated on a fairly regular basis over the next two generations, generally with the same result. As Thucydides (1.98–99) notes, the Athenians, who built and manned the ships, also did most of the actual fighting. They were therefore constantly gaining in military experience—in, for example, naval operations, siegecraft, and logistics—relative to those league states that contributed only money.

It is not surprising that specifically Athenian interests were increasingly furthered by league-financed operations. As a positive (to Athens) externality arising from the necessity of preempting Persian naval power, Athens had taken the next big step as a superpolis by leveraging the resources of many other states. Athens had, in short, embarked on the road to empire.10

These developments were viewed with alarm in Sparta. Thucydides (1.101) reports that in 463 BCE the Spartans secretly offered to aid the defection from the Delian League of the prominent north Aegean island-polis of Thasos (i526: size 4, fame 5). They were, however, prevented from doing so by a major earthquake that killed many Spartans and triggered an uprising by the helots of Messenia.

The helots threw up improvised fortifications on the steep slopes of Mount Ithome in central Messenia, enabling them to defy the Spartans, whose skill in open-field battle was not matched by their siege technique. In a quick turnabout, Sparta appealed for aid to Athens, by now the Greek state with the deepest expertise in siege operations. An Athenian army headed south, led by the highly successful general Cimon, who had long advocated closer relations between the two former allies. But there was another surprising turnabout. The Spartans, who, according to Thucydides (1.102), were now alarmed by the Athenians “daring and revolutionary nature” and feared that they might side with the helots, abruptly informed the Athenians that their services were not needed. Deeply offended, the Athenians returned home—and ostracized the pro-Spartan Cimon.

The events of 462 are sometimes described as a watershed in Athenian political history. With the eclipse of Cimon came a constitutional reform that limited the judicial authority of the Areopagus council of former archons to a few categories of criminal trial, eliminating its role in reviewing (and possibly setting aside) legislation passed by the assembly. The way was opened for a new style of leadership, prominently exemplified by Pericles—who was related by birth and marriage to the Alcmaeonids—the family of Cleisthenes. The decades after 462 saw an intensification of the democratic features of the Cleisthenic system.11

Over the course of the next generation, the system of people’s courts and the practice of paying citizens who held public office were expanded, enabling ordinary men to take an increasingly active role in polis governance. But those developments were hardly a revolutionary change of political direction. The increasingly important role of the navy in ensuring state security gave the ordinary-citizen rowers substantial bargaining power. But the growth of imperial wealth, conjoined with ever-deepening social networks made possible by the Cleisthenic tribal system, obviated for the time being any need for difficult bargains between elites and masses. Prodemocracy members of the elite, like Pericles, provided effective leadership for the state. Meanwhile, the ostracism of several prominent Athenians suspected of obstructionism undercut the ability of those elite Athenian who were opposed to deepening democracy to coordinate behind their own preferred leadership.12

The events of 462 showed that there would be no quick return to the Athens–Sparta alliance that had defeated the Persians, but there was no fundamental change in the direction in Athenian foreign policy. Like Cimon and Aristeides before him, Pericles and his political allies were ready and able to employ the Delian League to further Athenian policy goals. The decade following 462 saw ambitious operations in several theaters: against Persian bases in Cyprus and Phoenicia, in support of anti-Persian uprisings in Egypt, and against Athens’ old rivals in mainland Greece. Megara and Aegina were among the major Greek states now added to the league. An effort to incorporate the poleis of Boeotia, to Athens’ north, was, however, ultimately stymied by Spartan military opposition. Recognizing the status quo, the two superpolis rivals declared a five-year cessation of hostilities in 451; after another brief spate of hostilities, which included a Spartan incursion into Attica, a second armistice agreement was signed in 446 BCE. This time the peace was meant to last 30 years. In the event, it lasted for fewer than 15. The war that broke out in 431 BCE, recorded in great detail by Thucydides and usually known as the Peloponnesian War, would polarize the Greek world and convulse Hellas, on and off, for 27 years.13

ATHENIAN EMPIRE

Meanwhile, by the 450s, it was increasingly clear that the anti-Persia confederation was quickly morphing into an Athenian empire (map 7). In 454 BCE, following a major setback in which an Athenian expeditionary force was lost off Egypt, the Delian League’s treasury was moved from Delos to Athens. After this, we hear of no further meetings of the league assembly, an institution that had, in any event, devolved to a rubber stamp for policy decisions made in Athens. The same year saw the inauguration of the so-called Athenian Tribute Lists, a monumental set of inscriptions on a great marble stele set up on the acropolis. The inscriptions record the goddess Athena’s 1/60th share of the annual contributions of Athens’ sometime allies. In 449, some sort of peace agreement was struck between Athens and Persia. It appears that by the terms of the agreement, the Athenians agreed to cease raiding Persian territory, and the Persians agreed to keep their military forces away from the Anatolian coast and out of the Aegean. The ostensible goal of the league, containment of Persia, would now seem to have been fulfilled. But the mandatory annual contributions to the league treasury by member states quickly resumed. The question, by this time, is no longer whether the league was an Athenian empire but rather what sort of empire was it?14

The most obvious imperial model was Persia. The Athenians adapted some features of Persian imperial imagery, along with the system of assessing tribute and perhaps some Persian techniques of rule.15 But Persia’s empire was, measured in population, some 20 times the maximum size of the Athenian empire. There were, moreover, structural differences that went well beyond the difference in scale. Persia’s empire stretched across much of western and central Asia, encompassing a vast land area and a huge diversity of cultures and languages. Athens’ empire was not only smaller, it was much more homogeneous, culturally and linguistically. Virtually all the states under Athens’ control were at least Hellenized, if not fully Hellenic.16

Athens had another big advantage over Persia as an imperial power: Athens did not confront the intractable principal-agent problem faced by every extensive premodern continental empire. In light of slow overland communications and difficult logistics, the agents (local governors) must be granted considerable scope for independent decision and action by the principal (the central government or emperor). But, the greater an agent’s independence (and thus his capacity to serve his own interests), the lower is his motivation loyally to advance the interests of the principal. Most of the states controlled by Athens were on or very near the Mediterranean coast, and because Athens had a dominant navy of fast and powerful warships, communication, command, and control were much simpler for Athens than for Persia or any great continental empire. As the events of the Peloponnesian War would soon show, Athens was able to concentrate military forces in trouble spots with great speed and devastating efficiency. By contrast, it might take months, even years, for a Persian army to respond to a distant uprising. As a result, the Athenians had no need to create a Persian-like system of quasi-autonomous, and thus potentially rebellious, provincial governors.17

On the other side of the imperial control ledger, the Athenians lacked a legitimating ideology that could stand in for the Great King’s claim to have a special relationship to a great god. The closest thing the Athenians had to an imperial ideology was the claim that Athens was the mother-city of the Ionians—that is, the Greeks who spoke an Ionian dialect. It seems clear enough that the Athenians did make some efforts to assert an “ancestral” leadership over Ionians, claiming, for example, that Ion, the mythical ancestor of all Ionians, was the son of an Earth-born Athenian queen (see Euripides’ tragedy Ion). Yet there is little evidence than anyone outside Athens ever behaved as if that claim were in any meaningful sense action-guiding. In order for an imperial ideology to function in the interests of the hegemonic power, those subject to it must act under moral constraint: They must behave in a dutiful manner out of something exceeding the cost–benefit reasoning of economically rational agents. I know of no evidence that any of Athens’ imperial subjects ever acted out of a sense of duty to Athens arising from an ideology of “Ionicism.” Moreover, it is not the case that Athens’ empire was homogeneously Ionian—some subject states in northwestern Anatolia were Aeolic; others were Doric; yet others, notably in Caria in southwestern Anatolia, fell completely outside Greek ethnolinguistic subdivisions.18

The problems that could arise in the absence of a legitimating ideology of empire were exacerbated by the strong Greek commitment to the normative ideal of local citizenship. Although, as we have seen (table 2.3), many Greek states lacked full independence, at least in their ability to set their own foreign policy, there were limits to the degree of dependency that could be accommodated within a value system centered on citizenship. While ordinary citizens might see Athens as a supporter of local democracy, as a bulwark against domination by local oligarchs, there was some point at which at least part of the populace of a given state would push back against the devolution from “free and equal citizen of polis X” to “humbly obedient subject of imperial Athens.” The option of exchanging “citizenship in polis X” for the status of “citizen (or even quasi-citizen) of a greater Athenian state”—the approach to imperial expansion that was being adopted by the Romans in Italy—was never on the table.19

The Athenians guarded the status of Athenian citizenship jealously. Indeed, in 451 BCE a new law, passed by the assembly on a proposal sponsored by Pericles, restricted Athenian citizenship to people who could demonstrate that each of their parents had been an Athenian native. Mixed marriages (which had usually been of the form native Athenian male with nonnative wife) were no longer recognized as legitimate. The male offspring of a mixed marriage was now legally a bastard. As such, he was ineligible to inherit an equal share in the family property or to be presented by his father before the demesmen as a candidate for inclusion in the ranks of the Athenians.20

In lieu of an imperial ideology based on divinity, shared ethnicity, or shared citizenship, the Athenians could, in some cases, lean on shared regime preferences. In the course of the fifth century BCE, more Greek states, and especially those within the Athenian empire, adopted some version of democratic government. We seldom know many of the details. As we have seen in the example of Syracuse’s adoption of democracy in 465, the constitutional form taken by popular government might vary considerably from the Athenian model. But all democracies shared the common feature of being “not oligarchy.”

As the Greek historian Matthew Simonton has demonstrated in recent work, in the Greek world the political form “oligarchy” is not best thought of as the generic background political condition of all nondemocratic Greek states. Rather, oligarchy, as it was understood by classical Greeks, was a specific reaction by “the few who were wealthy” to the emergence of democracy as a strong form of extensive citizenship and collective self-government. Thus, with the development of democracy came the possibility that democracy might be subverted—not only by a tyrant, but also by an organized effort on the part of local elites to establish a government in their own interest. Elite interests might overlap with, but were far from identical to, the interests of the masses of non-elite natives. The ordinary citizens of a democratic Greek polis could, therefore, expect to do substantially worse if and when their polis was transformed by elites into an oligarchy—and vice versa.21

While Athens never consistently required subject states to adopt democratic constitutions, the Athenians were obviously sympathetic to democracy as a form of government in ways that the Spartans and Persians, for example, were not. Among the advantages, then, that might be enjoyed by the ordinary citizens of a Greek polis in the Athenian empire was the expectation of a certain level of solidarity with the demos of Athens. In several high-profile cases, notably after a revolt by the great island state of Samos (i864: size 5) in the 440s, the Athenians did actively promote the establishment of a democratic regime. Democratic states within the empire could expect some measure of Athenian support were local elites to seek to overthrow a democratic regime in favor of oligarchy. And thus, democracy may have encouraged some Greeks to accept their position as subjects.22

The most widespread benefit that the Athenian empire offered to its subjects was, however, economic. Most obviously, by guaranteeing protection against Persian privateers and against the ordinary pirates that have historically infested the Mediterranean in the absence of a strong naval power determined to suppress them, the Athenians created the baseline conditions for peaceful trade. Smaller states no longer needed to fear predation by larger states, or raids on their ships or coastal settlements by pirates—which was an endemic problem when there was no power strong enough to keep piracy down to a minimum.23

Reliable security, along with reliable punishment of would-be free riders, encouraged rational submission to imperial rule: Unlike raid-and-grab pirates, the Athenians had a vested interest in keeping order and in protecting the economic interests of tribute-paying imperial subjects. In the face of the alternative, residents of weak states were relatively better off, all things considered, when they paid a reasonable and predictable level of protection money to a stable hegemon with relatively long time horizons. The long Athenian horizon was graphically expressed, for example, by the Athenian Tribute Lists: The great stone stele set up prominently on the Acropolis in 454, on which the lists were inscribed, had room for 15 or more years of records: Clearly by setting up that massive stele, the Athenians signaled that they planned to be in the empire business for many years to come.24

The logic of rational acquiescence to rule was not lost on Greeks of the fifth century. An inscription found in Athens dated around 445–430 details the relations between “the community (koinon) of the Eteokarpathians” (on the island of Karpathos, between Crete and Rhodes) and the Athenians. The Eteokarpathians (i488: size unknown but surely small) seem to have taken some initiative in getting themselves assessed for tribute, and they donated building materials (in the form of a cypress log from a sacred precinct) to a construction project on the Athenian acropolis. In turn, they had received Athenian military intervention in a local dispute, and thus their community’s continued existence was guaranteed. The inscribed record of mutually beneficial interaction points to the self-consciousness on the part of a small community of the benefits it might receive by being under the control of a great state. Like most of the Greek states overall (figure 2.2), most states of the Athenian empire were small (size 3 or below).25

In the first book of his text, in an abbreviated analytic narrative of earliest Greek history, Thucydides theorized the relationship of rational acquiescence in a quasi-historical account of the rise of Greek civilization. He notes that in the distant past, before the Trojan War, there were no substantial coastal towns due to piracy.

But after Minos [mythical king of Crete] had organized a navy, sea communications improved…. [he] drove out the notorious pirates, with the result that those who lived on the coasts were now in a position to acquire wealth and live a more settled life. Some of them, on the strength of their new riches, built walls for their cities. The weaker, because of the general desire to make profits, were content to put up with being governed by the stronger, and those who won superior power by acquiring capital resources brought the smaller poleis under their control.

—Thucydides 1.8, trans. Warner (Penguin), adapted

Despite its setting in a mythic past, this passage is clearly meant to alert the reader to a central logic of empire—and especially of the kind of maritime empire that had been created by the Athenians during Thucydides’ own lifetime.

In fact, the Athenians seem to have run their empire with a close eye to the balance sheet of interests reckoned as costs and benefits—in the first instance, their own interests but, because the imperial system was based on increasingly high levels of economic integration and interdependency, the interests of other states as well. Both the strength and, as we will see, one of the weaknesses of the Athenian empire was the historically unusual degree to which it was predicated on assumptions about rationality of behavior, understood as the pursuit of interests capable of being reckoned upon a cost–benefit basis. Lacking any very promising ideological justification for their rule, the Athenians went on the assumption that, so long as the subject poleis were net gainers from the existence of the empire, local rulers (whether democrats or oligarchs) would, under most conditions, act like the Eteokarpathians. They would realize that their collective interests were better served by cooperation with the hegemonic power than by defection.26

The Athenian empire did indeed provide very substantial economic benefits for the states and their residents within its ambit in exchange for the costs they were asked to bear in the form of imperial tribute and loss of foreign policy independence. The total tax burden of the empire was probably in the range of 3% to 6% of imperial GDP. If, counterfactually, this comparatively light burden had been shared across the entire population of the Empire on a regressive per capita basis (in fact local elites bore most of the tax burden), an average family would have had to devote no more than one or two days of labor per month to paying the imperial taxes.27 In return, in addition to security against rapacious states and pirates, Athens provided substantial economic services: First there was, at Piraeus and in the Athenian agora, a central market for exchange. The costs of entering that market were not exorbitant—a standard (as it appears insofar as we have comparative Greek evidence) 2% tax on imports and exports. Although many goods were exchanged through cabotage—i.e., local coasting voyages by small-scale merchants—and so did not need to go through a central market, there were obvious advantages to some traders to having a single major market to which bulk and luxury goods could be brought for exchange. Fifth century writers were explicit about the advantages that central exchange brought, both to Athenians and to those who traded in Athens.28

The advantage was multiplied when the central market was well regulated; was liquid (well-supplied with specie); employed standard weights, measures, and units of exchange; provided first-rate facilities (docks, storage areas, transport system); and when there was a great deal of local wealth. Athens made major improvements in infrastructure and imposed regulations meant to reduce cheating by unscrupulous traders. The Athenians at first encouraged, and ultimately required, throughout their empire, the use of standardized weights and measures, and a standard coinage, in the form of Athenian owls. Finally, because of the massive production of owls by the Athenian mint after 449 BCE, the Athenians effectively guaranteed market liquidity: With perhaps 12–24 million silver drachmae produced each year by the Athenian mint, there was no lack of specie available with which to transact exchanges.29

The upshot of these several measures was to lower the costs of transactions and thereby to increase the value of voluntary and mutually beneficial exchanges. Under the relatively high-security, low-transaction-cost conditions promoted by the Athenian empire, increasing investment in specialization to maximize relative advantage and increasing the percentage of production aimed at exchange relative to that aimed at subsistence were rational behaviors. And thus, as we would expect, the part of Hellas controlled by Athens became wealthier. Moreover, Athens had a very limited capacity to impose a mercantilist policy that might have limited imperial subjects to trading within the empire—even if the Athenians had formed a preference for such a policy.30 Because imperial subjects traded outside as well as inside the empire, the growth of the imperial economy benefited all of Hellas—and thus it promoted the efflorescence that we are seeking to explain.

The Athenians themselves, of course, benefited most of all. Athenians benefited directly, as rentiers. Elite Athenians reaped rewards from military leadership positions, especially when, as was often the case, military operations resulted in booty. Non-elite Athenians had the chance to raise their socioeconomic status by sharing rents from distribution of goods, notably when agricultural land was confiscated from a subject state that had failed fully to grasp the rationality of acquiescence. Confiscated lands were divided among Athenian “cleruchs” (klerouchoi: “shareholders”—the Greek root kleros is the term that was used for the “allotment” of land and helots controlled by each Spartan in the Lycurgan system). Cleruchs, often drawn from the ranks of formerly poorer Athenians, might take up residence abroad to look after their new landholdings in person. Alternatively, they might lease the land on a sharecropping basis back to its original owner. Other Athenians benefited from the imperial revenues that were plowed back into the Athenian economy: Athenian rowers, marines, and infantrymen were relatively well compensated for military service on the annual naval patrols in the Aegean and for garrison duty among potentially restive subjects.31

Yet other Athenians, of all classes, benefited from pay for government and legal service and from a surge in public building. That surge began in earnest in the mid-440s: A series of extraordinary new temples and related sacred buildings were constructed on the Acropolis and in major towns of Attica. The Parthenon, the most technically advanced temple that had ever been constructed in Greece, was the masterpiece. But it was only one sacred building among many that went up in the city of Athens and at the demes of Rhamnous, Eleusis, and Sounion. The city and Piraeus fortification circuits were now connected with monumental long walls, which created a fortified corridor from the coast to the city, five miles inland. Piraeus was fitted out with monumental dockyards and shipsheds to protect the precious warships when they were not on active duty. The theater of Dionysus was for the first time built in stone. A new concert hall (the Odeon) was the largest roofed performance space ever contemplated in the Greek world. And a host of other public buildings, many of them constructed at an unprecedented level of grandeur and attention to artistic detail, went up in the agora and in other parts of the city and countryside. Based on the limited evidence preserved in inscriptions, the wages, even for unskilled or semiskilled construction work were good—well above the subsistence level that was the premodern norm (ch. 4).32

Athenian industry was growing apace: Silver production from the mines of south Attica reached all-time highs, as did the marble and limestone production of Athenian quarries and vase production in pottery workshops. It is a reasonable guess that other industries (weaving, leatherworks, bronze and iron foundries, etc.) flourished as well. Prominent Athenian politicians were reputed to have made their fortunes in industry—in, for example, tanning and the production of musical instruments.33

Meanwhile, the population of Athens was also growing. Athens was a highly desirable destination for economic migrants, both temporary and permanent. Despite casualties of war and a more restrictive citizenship policy, conditions of improved welfare also promoted increased natural population growth. By the mid-430s, Athenian (adult male) citizen population had reached its ancient peak of perhaps 50,000 or more. A good number of citizens lived abroad, as cleruchs or garrison soldiers, and Athens led a new wave of Greek colonization, collaborating in the founding of new poleis in Thrace (notably Amphipolis [i553: size 5]) and Italy (Thurii [i74: size 3]). Nonetheless, the total resident population of the polis certainly exceeded 250,000; if we add nonresident Athenians (cleruchs, garrison troops, etc.), the total probably exceeded 300,000.34

The growth of Athens was both spurred by and was a result of more intensive and more diversified specialization, both in Athens and across the Greek world. The imperial-era comedies of Aristophanes preserve a startlingly high number of names for work specializations in industry and service.35 Intensified specialization, in a context of competition and cultural conditions enabling ready emulation, drove innovation. The results are, today, vividly evident in the high-cultural products of what has often been described as the Athenian Golden Age: These include the tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides; the comedies of Aristophanes; the architecture of Ictinus; the sculpture of Pheidias; the histories of Herodotus and Thucydides; the moral philosophy of Socrates; the astronomy of Anaxagoras; the anthropology of Democritus; the medicine of Hippocrates—the list could be very readily extended.36 It would be even more impressive if so much had not been lost since antiquity. Fifth century Athens was, for example, the center of major innovations in large-format figurative painting and in musical composition and performance. These remarkable cultural results were, as we have seen, the basis of Byron’s (and many others’) belief in Greek greatness. They were produced both by native Athenians and by artists and intellectuals drawn to Athens by its role as a cultural capital. As Ian Morris and Reviel Netz have shown with simple statistics, Athens was unquestionably the intellectual and cultural hub of the Greek world through much of the fifth century BCE.37

Less visible to us than the products of high culture, but of great consequence for Athens and Hellas, were innovations in other domains. Athenian warships were not only numerous, they were also capable of speed and maneuvers that were well in advance of those built and maintained by other Greek states—the incremental results of ever-deepening expertise gained by thousands of hours of experience by naval architects, captains, steersmen, and rowers. The management of the empire led to deepening expertise in the organization of state finances—the leadership of Pericles and other prominent Athenians of this era was in part based on their skill in the traditional roles of generalship and public speech but in part on the new domain of organizing the finances of an imperial state.38

GREEK THEORIES OF WEALTH, POWER, AND POLITICS

These dramatic changes did not go unnoticed—or untheorized—by contemporaries. The so-called sophists, a highly diverse group of Greek intellectuals, wrote texts and offered to teach students (typically the offspring of elite Athenians capable of paying their fees), in fields of expertise relevant to political leadership: broadly speaking, they taught “political science” (politike techne)—which conjoined theories of human nature and the nature of power with the theory and practice of rhetoric, music, mathematics, and ethics. Behind their theorizing about politics lay a general theory of specialization and education: The sophists claimed to have mastered the essence of what it took to be a specialist and that they knew how to achieve genuine expertise.39

Some Athenians scoffed at the sophists’ claims. Among their most prominent critics was Socrates, whose dialectical method was meant to show that (among other things) the sophists’ pretensions to be masters of political science were spurious. But many others, like Socrates’ young friend Hippocrates (ch. 5), took the sophists seriously and learned from them—or hoped to. Herodotus was clearly well aware of arguments developed by the sophists about the techniques that produced efficient centralized authority and about the strengths and weaknesses of various forms of government. But among surviving fifth century writers, it was Thucydides who most obviously and effectively adopted the techniques and arguments of the sophists (as well as those of other imperial-era intellectuals—notably including the Hippocratic medical writers), in his exposition of the origins and conduct of the Peloponnesian War.

While his text (as far as we know he produced just the one) is often read simply as a brilliant historical narrative of a terrible war, Thucydides goes beyond the discipline of history, as we now tend to think of it, in his analytic framework and aims. His expressed goal was not only to offer an accurate account of the course of events but also to enable readers to be effective political actors in the future. Thucydides’ explanation for why the Peloponnesian War broke out, and why both powerful and weak states acted as they did in the course of the war, was based on a view of human political nature as, to a significant degree, rationally self-interested.40

Humans are, for Thucydides, driven by, on one side, fear of loss, and on the other by desire for wealth, power, and glory. States, as aggregates of human fears and desires, are likewise driven by their perceived self-interest. All states seek to survive; powerful states also seek rents and resources that enable them to dominate other states. All states, and all powerful states, therefore, shared some features in common with one another. But they also had salient features that made them differ from one another. For Thucydides, the three superpoleis of Athens, Sparta, and Syracuse—which were the most important (but certainly not the only) collective historical agents in his history—were at once relevantly alike and relevantly different. Both their similarities and their differences helped to determine the choices that in turn determined the course of the war—or helped to affect it, given that chance was also a major factor in Thucydides’ narrative.41

Thucydides was intensely interested in precisely the puzzle that concerns us, that is, explaining the changing situation of Hellas in terms of both wealth and organized political power. Thucydides pointedly contrasts the impoverished and weak Greek communities of ancient times with the rich and powerful states of his own era. As we have already seen, he regarded it as rational for a small and weak state to choose to accept subjection to a powerful hegemon capable of providing security and welfare. This allowed him to explain the emergence and persistence of the coalitions of states that enabled Athens, Syracuse, and Sparta to leverage human and natural resources. Thucydides was especially interested in the phenomenon of the dramatic growth in Athenian wealth and power in the 50-year era between the Persian Wars and the Peloponnesian War. For Thucydides, Athens in the age of Pericles represented a new and fascinating condition of human possibility.42

The necessary conditions for Athens’ dramatic rise were, in Thucydides’ view, the massive and extensive fortifications that ensured security against hostile powers, a great navy that provided the capacity to enforce the will of a powerful hegemon with unmatched quickness and efficiency, and huge capital resources that funded both the walls and the navy. These three conditions were created and sustained by a large, highly experienced, highly motivated, and relatively cohesive citizen population. But these were still only necessary, not sufficient, conditions. The essential ingredient that propelled Athens into a new condition of human possibility was self-conscious human reason and leadership. Thucydides wrote his account of the great Peloponnesian War in part to demonstrate to readers the role of human knowledge and knowledge-based choices in the rise, and ultimately also in the fall, of Athens as a great imperial power.

Thucydides singled out Pericles as a leader who had come to understand the underlying factors that could and did, under his direction, make Athens into a new kind of superpolis—a Greek state that had moved to a higher level of achievement and that had the potential to bring much of the rest of the Greek world along for the ride. Three explanatory speeches are put into Pericles’ mouth in Thucydides’ history: The second and most famous is an inspiring funeral oration over Athenian soldiers who fell in the first year of the Peloponnesian War. In the funeral oration (2.35–46), Pericles celebrates the extraordinary achievements of Athens’ post-Persian War generation, links Athens’ present greatness to its democratic form of government and to the depth and diversity of individual Athenian skills, and suggests that Athens can and should be a model for all of Hellas. The first Periclean speech in the text (1.140–144) is delivered to Athens’ citizen assembly. Here Pericles sets out the necessity of fighting Sparta and enumerates the unique resources that Athens would bring to the struggle and that, as he confidently predicted, would enable Athens to be victorious. The third and final speech is again delivered to the citizen assembly (2.60–64), but this time in the aftermath of a plague that had devastated Athens during the war’s second year. In this speech, Pericles explains why the Athenians cannot afford to abandon the imperial project and emphasizes how each Athenian’s private interests were inextricably conjoined to the collective fate of the Athenian state.43

Pericles is credited by Thucydides with extraordinary insight and talent as a leader, but he did not work in the shadows nor did he ever have anything like autocratic political authority: Each of his speeches in Thucydides’ text was delivered to a mass audience, and in reality his policy recommendations, which were offered in the face of rival policies urged by other leaders, were deliberated and voted upon by Athenian citizen bodies. Pericles was a highly skilled player within a game with rules that were widely understood. although Thucydides’ analysis of Athenian power and wealth is unique in its depth and detail, other Athenian writers also grasped the essentials of the imperial age.44

A short text by Pseudo-Xenophon, an anonymous author, nicknamed “The Old Oligarch” by modern classicists, describes Athens as a democratic imperial state that was at once “bad” (because not dominated by the excellent few) and extremely effective at gaining and keeping wealth and power. The Old Oligarch’s text is (or affects to be) by a politically disaffected Athenian (he speaks of Athenians as “we”) writing for an audience (“you”) that is antidemocratic in political sympathy and relatively ignorant of Athenian norms. The Old Oligarch assumes that his reader wants to understand how and why “bad” Athens rose to such a remarkable level of prominence in the Greek world. Athens’ effectiveness is succinctly explained as a result of non-elite Athenians’ capacity to recognize and to pursue their own best interests and of their development of expertise in naval operations. That expertise enabled them to exploit a favorable location and to leverage the talents of a large and diverse population at home and abroad. Moreover, noted the Old Oligarch, the Athenians were (unfortunately, in his view) not at risk of an oligarchic coup because both masses and elites benefited materially from the imperial order that their conjoined efforts maintained. Finally, our author recognized that the Athenians benefited by legally protecting not only their own interests but also those of slaves and noncitizens.45

While we can now see why the growth of the Athenian imperial economy would have had positive knock-on effects for the economies of other parts of the Greek world and thus we can begin to explain some part of the general phenomenon of efflorescence, the rise of Athens was a serious and growing problem for its rivals. The control Athens exercised over its imperial subjects meant that, even without implementing a general mercantilist strategy, Athens could punish trading states with which it was displeased. One of the triggers of the Peloponnesian War was the Athenian decision to exclude Megarian merchants from the harbors of the empire after Megara left the Athenian empire to rejoin the Peloponnesian League (Thucydides 1.139.1–2). Moreover, the fast and continued growth of Athenian wealth and power threatened the established position of Sparta. Because Sparta’s economy was more or less a closed system, based primarily on extracting the surplus of the agricultural production of Laconia and Messenia, Sparta stood to one side of the system of economic integration and interdependency of the Athenian empire. After the falling out of 462, and in spite of the uneasy truce of 446, Athens’ gain looked, at least potentially, to be Sparta’s loss.

The demonstrated Athenian ability to take member states away from the Peloponnesian League degraded Sparta’s alliance system and thereby its military capacity. Corinth was one of the most important poleis of Sparta’s league due to its size, wealth, large navy, and strategic location on the isthmus, potentially controlling movement between southern and northern Greece. Corinth’s threat to leave the Spartan alliance in favor of Athens (Thucydides 1.71.4), was, in Thucydides’ account of the outbreak of the war, a matter of grave concern to Sparta. But the ultimate reason for the war was, according to Thucydides, deeper: The Spartans were terrified by the growth of Athenian power (Thucydides 1.23.6, 1.88.1).

The underlying reasons for the Spartans’ fear are traced in detail by Thucydides through the device of a speech given by “the Corinthians” at a Peloponnesian League assembly held to debate recent Athenian moves against league members (Thucydides 1.68–71). The Corinthians argue, with devastating rhetorical force, that a new Athenian approach to state power and its uses was quickly rendering the Spartan approach to power politics obsolete. The Corinthians portray the Athenians as dynamic risk takers who had recognized that quickness, innovation, and an experimental approach to policy drove the continuous growth of wealth and power. Moreover, individual Athenians eagerly cooperated in collective state ventures because they recognized that their individual interests were bound up in that growth. In the Corinthians’ assessment, the Spartans were, in every sense, the Athenians’ opposites: Slow, conservative, risk-averse, and (contrary to Plutarch’s vision of Lycurgus’ Sparta as a state defined by virtuous common-good seeking) narrowly and selfishly self-interested. Athenian collective dynamism had potential downsides and might collapse under intense pressure, but only if the Spartans pressed the issue by declaring war. The main points of the Corinthians’ argument in Thucydides’ text are summed up in table 8.1.46

Although Thucydides’ Corinthians tended to make their argument in terms of inherent Spartan and Athenian “national characters,” their core argument—that the Athenian system was generative, influential, and capable of indefinite expansion (if not stopped in time)—suggests that Athens’ success was not uniquely a matter of a peculiarly Athenian character. Rather, indirectly mirroring Pericles’ claim in the funeral oration recorded by Thucydides (2.41.1.) that Athens could be “an education to Hellas,” the Corinthians seem to regard the Athenian approach as both attractive to others and, at least in some senses, a model that other communities might successfully emulate. The implication was clear enough: While conservative Sparta stagnated, much of the rest of the Greek world, led by dynamic and aggressive risk-taking Athenians, would continue to grow. At some time, the tipping point would be reached and Sparta’s military specialization would no longer be enough to maintain its superpolis status. And at that time, there would be a cascade of defection from the Peloponnesian League, ultimately leaving Sparta isolated in a world dominated by hostile rivals who had chosen, out of fear or desire, to follow the Athenian path of dynamic growth.

TABLE 8.1 Thucydides’ “Corinthian Assessment”

Growing Athens: Strong Performance |

Stagnating Sparta: Weak Performance |

Negative Side of Athenian Growth |

|

Agility • Speed • Innovation • Flexibility/versatility across domains |

Clumsiness • Slowness • Conservatism • Domain-specific expertise |

Decision gridlock, as a result of too much information, conflicting information |

|

Ambition • Hard work • Risk-taking • Future orientation |

Complacency • Laziness • Risk aversion • Past orientation |

Rashness, failure to calculate downside risk. Overambitious leadership |

|

Common-ends seeking • Public goods • Long-term goals |

Narrow, short-term self-interest seeking by groups and individuals |

Free riding, factionalism |

NOTE: Source: Thucydides 1.70.2–71. Adapted from table in Ober 2010b: 74.

If the Corinthians’ arguments were valid, then Sparta certainly did have a lot to worry about. Thucydides’ claim that the ultimate cause of the Peloponnesian War was Sparta’s fear at the growth of Athenian power appears entirely plausible as a rational explanation of a cost–benefit calculation: The Spartans were not afraid of a democratic bogeyman. They were afraid of the consequences of unusually rapid growth by a hostile rival and the prospect that its growth was sustainable into the foreseeable future. Under these circumstances, unless they were willing to abandon the contest for preeminence, the Spartans had no choice but to attack before the power disparity became too great. Whether that would be a matter of months, years, or decades was and still is an open question. The question of how long the attack could be postponed was, according to Thucydides (1.79–87), hotly debated by the Spartans in a closed meeting. But it came down to a question of when, not whether, to attack. In this sense, Thucydides’ claim that the war’s origins must be sought, not in particular incidents, but in deep structural changes in the Greek world, in changes that were caused by what we can now characterize as an extended period of unusually robust efflorescence, seems well supported. And thus, for the first time but not the last, the prospects for an era of Greek efflorescence that might continue indefinitely were put at risk by the considerations of interstate rivalry and the politics of state power.

PELOPONNESIAN WAR TO 416 BCE

Thucydides’ account leads us to believe that Pericles and the Spartans had done the same math and had come to similar conclusions: Pericles realized that war with Sparta was inevitable. But, as he assured the Athenian assembly in the first of his speeches in Thucydides’ text, it was winnable so long as the Athenians did not overreach by seeking to grow the empire before Sparta had given up the attempt to end it. Pericles’ optimism about Athens’ prospects was not universally shared. Many Greeks apparently agreed with the Spartans that, given Sparta’s unquestioned superiority in infantry forces and the fact that Greek wars on the mainland tended to be decided by infantry battles, it would be a relatively short war: Within a few campaigning seasons, at most, the highly trained Spartan hoplites, backed by the Peloponnesian infantry and Boeotian cavalry, would crush the Athenian land forces, deciding the contest decisively in Sparta’s favor (Thucycides 2.8.4, 5.14.3).

Pericles foresaw a very different war: The Peloponnesians would invade Attica annually, but the Athenians would not meet them in the field. Since the Peloponnesian allies had farms of their own to look after, the occupation of the Athenian homeland would be fairly brief. The Athenian cavalry, along with garrison troops at fortified outposts, would harry the invaders, preventing them from dispersing to plunder efficiently, and thus protecting, as well as possible, Athenian extramural assets. The Athenians did not, in any event, need to confront the Spartan–Peloponnesian army on land. Athens’ extramural population would be evacuated from the villages and towns of Attica and housed in the fortified city–Piraeus complex. The entire population could readily be fed for as long as necessary with imported food, paid for by the unimpaired imperial economy. The Athenian fleet would keep order in the Empire and would launch maritime raids on vulnerable targets along the Peloponnesian coasts. Megara would be subjected to biannual invasions and forced back into the Athenian fold. Eventually the Spartans would tire of the fruitless enterprise and retire to their strongholds in Laconia and Messenia, leaving the rest of the Greek world to be integrated into the empire and developed at leisure under Athenian leadership.47

The first year of the war, 431 BCE, went exactly according to Pericles’ policy recommendations and plans. The Peloponnesians marched into Attica, but despite some grumbling by the residents of the very large deme of Acharnai, where the Spartans, not coincidentally, made their camp, there was no break in Athenian discipline. Harrying by Athenian cavalry and garrisons kept the invading forces relatively compact, and the damage done by the invaders was minimal. The counterraids and invasions of Megara went off like clockwork. Pericles’ inspiring funeral oration, given over the bodies of the relatively few Athenian soldiers who fell in the course of the year, was offered at a high point of optimism and enthusiasm. The democratic political order, characterized by skillfully deployed expertise and rational planning, had brought Athens to its acme of wealth and power. Athens appeared to be a whole new kind of superpolis, capable, it seemed, of taking on the Spartans in a new kind of war.

The second year of the war was starkly different: In the summer of 430 BCE, the Peloponnesians stayed in Attica for longer (40 days) and were able to range more widely and to do more damage. But the real crisis came with the outbreak in Athens, although not among the Peloponnesians, of a highly contagious and usually fatal disease. Within two years, the plague had carried off at least a quarter of Athens’ population, a total of perhaps 75,000 people. Neither scientific medicine in the new Hippocratic style nor old-fashioned prayers to the gods had any effect. This was a staggering blow to Athens’ plans, in every possible sense. Pericles’ second assembly speech in Thucydides’ text was delivered in the aftermath of the first and worst outbreak of the disease. Pericles was indicted on legal charges, fined, and temporarily deposed from his position as general. But the surviving Athenians nonetheless took his advice to stay the imperial course. Meanwhile, democratic political order proved robust: The government continued to function, and military operations continued unabated.48

After Pericles died of plague in 429, his grand strategy for the war was initially adhered to by his political successors. In 428, the Athenians faced their next great test: the revolt of the major subject state of Mytilene (i798: size 4, fame 5) on the eastern Aegean island of Lesbos and the threat of a simultaneous Peloponnesian land and sea attack on Athenian territory. Thucydides’ vivid account of the Athenian response demonstrates the depth of Athenian military expertise and also the value of individual Athenians’ adaptive versatility.49

Upon receiving news of the revolt, the Athenians dispatched 40 warships to Lesbos, where they established a naval blockade. The Peloponnesians, meanwhile, were slow to muster, “being both engaged in harvesting their grain and sick of making expeditions” (3.15.2). The Athenians responded to the Peloponnesian naval threat with a devastating show of force, manning 100 ships with which they descended upon the Peloponnesian coast, ravaging at will.50 In order to pay for the necessary operations, the Athenians levied a 200-talent property tax upon themselves while also sending commanders abroad to collect imperial funds. When the discouraged Spartans disbanded their half-assembled invasion force, the Athenians dispatched a general to Mytilene with additional forces.

The Athenian reinforcements came in the form of an army of hoplites, who rowed themselves in triremes to Lesbos. When they arrived, they built a siege wall to complement the naval blockade. Hard pressed by the siege, the Mytilenean oligarchs armed the lower classes, who then demanded distributions of grain. Caught between a rock and a hard place, the Mytilenean oligarchs surrendered. More than 1,000 of them were executed. The agricultural land of Mytilene was turned over to Athenian cleruchs.

The Mytilene campaign of 428–427 seemed to confirm the Corinthian portrait of the agile, ambitious, and cooperative Athenians. After an informal intelligence network brought advance warning of hostile intentions, the Athenian military response to the revolt was masterful and multifaceted. The closely coordinated naval blockade of Mytilene, siegeworks, land operations against other Lesbian cities, and naval patrols in the Aegean accomplished Athens’ goals with dispatch. The threat of a Peloponnesian land and sea invasion in late summer 428 failed to panic the Athenians. By digging deep into their reserves of human and material resources, they launched a huge naval force manned by heavy infantry: Athenian hoplites, it turns out, were capable oarsmen, and they took up oars without the foot-dragging that stymied plans for a Peloponnesian expedition.

The operations of 428–427 reveal that the all-important technical expertise of rowing warships at a high Athenian standard was widely dispersed across the Athenian citizen population.51 When the occasion demanded it, there was no resistance on the part of “middling” hoplites to take on the oarsman’s role usually fulfilled by poorer citizens. Neither technical incapacity nor social distaste stood in the way of generating the required level of projectible power at the right moment. There seems to be a clear connection between democratic culture, with its emphasis on basic equality among a socially diverse citizenry, the wide distribution of certain kinds of technical expertise, and Athenian military proficiency. Just as the Athenian hoplite accepted a poorer fellow citizen as an equal when sitting in assembly or on a jury, so too he accepted the “lower class” role of rower when the common good of the state demanded it. And upon arrival at his destination, he proved to be a willing and skilled wall builder in the bargain.52

The capacity of the individual Athenian to acquire a wide range of technical skills and to recombine various of his diverse abilities into new skill sets as the situation demanded meant that the Athenians could be flexible in deploying their manpower reserves. Thucydides’ military narrative gives substance to the boast in Pericles’ funeral oration: “I doubt if the world can produce a man, who where he has only himself to depend upon, is equal to so many emergencies, and graced by so happy a versatility as the Athenian. And that this is no mere boast thrown out for the occasion, but plain matter of fact, the power (dunamis) of the state acquired by these habits proves” (Thucydides 2.41.1).

What is particularly striking about Thucydides’ Mytilene narrative is that the Athenians’ ability to excel is not limited to upward social mobility but implies mobility to any point on the “social status–labor map” that the situation demanded. Athens’ democratic advantage was on full display.53

The Mytilene campaign demonstrated the extent of Athenian potential, but not all military operations went so smoothly; there were serious setbacks in Aetolia, Boeotia, and other theaters. Meanwhile, the Spartans produced in Brasidas a highly competent and strikingly innovative commander who saw that the best hope for breaking the impasse of the war was to take the war to Athens’ imperial subjects. The result was a broadening of the conflict. Brasidas’ new strategy not only put pressure on Athens; it exacerbated latent conflicts between prodemocratic and pro-oligarchic elements in Greek states, resulting in savage civil wars.54

The huge expense of fighting the long war led to a sharp increase in the imperial taxation rate, and in general to a more coercion-intensive approach to imperial control. Because, as we have seen, the nature of the maritime Empire allowed an unusual degree of command and control compared to extensive continental empires with their principal-agent problems, Athens could readily increase tax and coercion rates, and, in the 420s, did so. Direct tribute taxes on states were raised in 425, and new indirect taxes on trade from the Black Sea were imposed. The total tax burden on the subject states of the Empire must have doubled, at the very least. Meanwhile, in 428 the Athenians for the first time imposed substantial internal war taxes on themselves. In sum, the costs to both Athenians and their imperial subjects of imperial centralization were rising sharply, while the benefits were declining.55

After years of seesawing conflict and serious losses for both of the principal competitors and their allies, the rival powers were exhausted. A truce was declared in 421 BCE that reestablished something very like the prewar status quo. But many on each side remained unsatisfied: While Athens had taken a huge demographic hit and had spent down its capital surplus, the structural danger to Sparta of sustained Athenian growth had not gone away. On the Athenian side, the primary goal of reducing Sparta to a regional power incapable of standing in the way of expanding the empire had not been achieved. Ambitious men on both sides, and third-party opportunists, were eager to see hostilities recommenced.56

In 416, Athenian hawks persuaded the citizen assembly to vote for an attack on Melos (i505), a small (size 3), oligarchic, Aegean island polis. Melos was an ostensibly neutral state that had never been part of Athens’ league or empire and may have provided some material support early in the war for Sparta. When an Athenian expeditionary force arrived at Melos, but before the commencement of hostilities, the Athenian commanders sought permission to speak to a full assembly of Melian citizens: Clearly they hoped to persuade the Melians of the rationality of acquiescing to Athenian rule. Melos’ oligarchic leaders refused the request. Thucydides produces the resulting discussion between anonymous Athenian commanders and the equally anonymous Melian oligarchs in the form of a dialogue.57

In the Melian dialogue, the Athenians make arguments readily identifiable as sophistic in origin: Their premise is that their mission at Melos is entirely motivated by Athens’ perceived interests in eliminating a neutral state in a region otherwise dominated by Athenian subjects. The anticipated benefits to Athens outweigh the cost of the operations that would be necessary to complete the conquest. The Athenians prefer that the Melians submit voluntarily but will eliminate the Melians if necessary. The cost–benefit calculation favoring conquest will not be changed by a Melian choice to resist. The Athenians pointedly refuse to listen to justice-based arguments. The Melians are left to assert that they will place their trust in the admittedly slim hope of succor by the Spartans or by the gods. The outcome, as the Athenians had pointed out, was never seriously in doubt. After the Melian resistance failed, the Athenians killed the male citizens and sold the rest of the population into slavery. The land was then redistributed to Athenian cleruchs.58

Thucydides’ account of the Melian dialogue and its aftermath makes an important point about the limits of human rationality when it is understood in cost–benefit terms. By the strict economic accounting advanced by the Athenian commanders, the Melian leaders made a painfully irrational choice: giving up the opportunity to retain much of what they currently had for a vanishingly small chance of keeping everything by somehow defeating the superior Athenian forces. Yet, and I think this is Thucydides’ point, the Melian choice to take an enormous risk of a catastrophic loss, in the vain hope of maintaining their status quo, followed from an entirely normal human decision process, in which the emotional attachment to what we have outweighs considerations of what we can actually expect. That process, which is described by the behavioral psychologist Daniel Kahneman in terms of “prospect theory,” is irrational in the economic terms of risk assessment, probability, and cost–benefit payoffs. Yet it is the way most of us make decisions much of the time: Faced with the prospect of a substantial loss and a slight chance to avoid all loss, most people will choose to gamble at odds that no economically rational individual with a basic intuitive conception of mathematical probability would ever accept.59

The Melian oligarchs’ “irrational” decision to fight demonstrated the limits of the rationality of acquiescence to Athenian rule. Ominously for the Athenians, if the rulers of enough states were similarly irrational in making their choices about resistance or submission, the Athenians would be unable to maintain their empire. They could take on only so many battles at one time, even assuming the high standard of military efficiency that they had manifested in the suppression of the Mytilenean revolt. The decision of the Melians to gamble on resistance pointed to a weakness in the sophistical “realist” analysis of power and human motivation. In the wake of Melos, Thucydides’ text would seem to imply, the Athenians would do well to remember Pericles’ cautious advice that there be no attempt to expand the empire until the war against the Peloponnesians had been concluded on terms favorable to Athens.

ATHENS VS. SYRACUSE

In the summer following the attack on Melos, the Athenians embarked on the most ambitious military operation of the war: a massive invasion of Sicily, aimed at conquest of the superpolis of Syracuse and at radically expanding the Athenian empire into the western Mediterranean. Thucydides (6.8–26) offers a detailed narrative of the assembly meeting at which the decision was made. Although a substantial Athenian force had campaigned in Sicily in the 420s in support of states friendly to Athens, Thucydides claims that the Athenian voters were largely ignorant of the physical size, demography, and political history of Sicily. He implies that they were misled by Alcibiades, the most prominent of the hawkish leaders who overemphasized divisions within and between Sicilian poleis. Others, by contrast, urged caution. The most prominent of the cautious leaders was Nicias, the general who had brokered the peace with Sparta in 421 and who, ironically, ended up as Athens’ chief commander on Sicily. Nicias pointed to Sicilian manpower and material resources that could be brought to bear against an Athenian invasion and challenged the hawks’ optimistic portrayal of Sicilian divisiveness.60

In fact, the situation in Sicily was complex. In the decades after the end of the tyrannies and the establishment of republican governments in the 460s, the Sicilian economy, still heavily based on agricultural exports, continued to grow. Carthage and the Aegean Greek world provided ready markets for Sicilian food products. Wealthy Syracuse and Akragas, and to a lesser degree other Sicilian poleis, spent lavishly on public buildings, minted large issues of silver coins, and became centers of culture and science. There were, however, deep political divisions—and not only between Greek poleis. In the 450s, Syracuse, Akragas, and the major Greek states had confronted an insurgent movement driven by ethnic nationalism among the native Sikels of east-central Sicily. That movement had been crushed and its leader coopted, leaving Syracuse free to rebuild a mini-empire in eastern and northern Sicily. Hostilities had flared anew between democratic Syracuse and oligarchic Akragas. Leontini in eastern Sicily was threatened by Syracuse’s expansion. The major Elymian city of Segesta was threatened by Greek Selinous. And there were festering social tensions within Sicilian Greek cities, dating back to the fall of the tyrannies, centered on disputes over citizenship and property and on antagonism arising from stark inequalities between wealthy elites and ordinary residents.

Athenians who attended to Sicily’s growing economic prosperity could have concluded either that it would be a tough opponent or a highly desirable prize. Those focusing on Sicilian politics might point either to endemic divisions that an invader might readily exploit or to the alliance among Sicilian poleis that had doomed the Carthagian invasion of 480. In the background was the historical tendency of the Sicilian Greek cities to exchange information and to follow regional trends in cascades of emulation—a factor that could tilt either in the invaders’ favor or against them.

The original agenda of the Athenian assembly meeting at which the fateful decision was made to invade Sicily with a massive force was quite narrowly framed: The assembly was to decide on details of the logistics for a relatively modest military expedition to Sicily, of about the same magnitude as the Athenian force that had campaigned there in the 420s. The expedition’s ostensible goals were defensive, to support Segesta and other Athenian allies against expansionism on the part of Syracuse and Selinous. But Nicias, who was an elected general in 415, feared that a modest expedition could quickly escalate, given the ambitions of the Athenian hawks.

In what proved to be a fateful speech to the assembly, Nicias unconstitutionally raised an issue that was not on the Council-approved agenda: the option of canceling the expedition altogether. He also ferociously attacked the character and motivations of Alcibiades, the prominent hawkish leader. Then, when the assembly evinced no interest in scuttling the planned expedition, Nicias tried a second ploy. He raised the stakes of the invasion, arguing that if there must be an expedition to Sicily, it must be a huge one, since only a supersized force would be able to control the risk of failure. He gambled that the Athenians would prefer the no-expedition option to the high cost of guaranteeing the outcome by voting for a hugely expensive show of military might. As it turned out, he badly misjudged his audience.

In a logical inverse of the irrational (from a cost–benefit, probable-outcome perspective) choice to risk everything on a slight chance of saving everything, made a year before by the oligarchs of Melos, the democratic Athenians proved ready to pay an irrationally high “insurance rate” to lock in the gains they now felt confident they could reap from the expedition. Once again, as Kahneman’s experimental work on prospect theory demonstrates, this is a common reaction of people facing the possibility of a large gain. They willingly spend heavily to ensure against a small chance of failure.