5

EXPLAINING HELLAS’ WEALTH

FAIR RULES AND COMPETITION

TAKING STOCK

The evidence presented in the previous chapter shows that in the 700 years between 1000 and 300 BCE Hellas experienced a sustained era of economic growth, culminating in a strikingly high level of development. By the later fourth century BCE, the Greek world was unusual in the extent and density of its population, its level of urbanization, the material conditions of life (including housing), and the health of the adult population. In comparison with other premodern societies, wealth and income were quite equitably distributed. Many Greeks lived between the extremes of affluence and poverty and well above the level of bare subsistence. There is good reason to believe that consumption by a substantial middle class drove classical Hellas’ economic growth.

While there is room for debate about just how wealthy classical Hellas actually was, all the evidence discussed in chapter 4, drawn from a variety of primary sources and modeled in different ways, points in the same direction—and away from standard ancient and modern premises about Greek poverty. Classical Hellas was wealthy in ways that are unparalleled in earlier or later pre-twentieth century Greek history and rare in the documented premodern history of the world.

It remains to explain the phenomenon of exceptional economic performance. Why and how did Hellas become wealthy? The solution to the puzzle of Greek economic exceptionalism is political exceptionalism: institutions, understood as action-guiding rules, conjoined with civic culture, action-guiding social norms. Citizen-centered rules and norms promoted relatively open markets, enabling the constant exchange of information among many diverse people, and thereby drove continuous innovation and learning.

The institutions and civic culture that underpinned efflorescence arose in the context of dispersed authority, both at the level of the ecology of small states described in chapter 2 and at the level of individual poleis. We saw in chapter 3 how decentralized social cooperation in the form of a plethora of marketlike exchanges of information could ground high-level political order. It is because relevant information kept getting better—taking the form of greater assurance of aligned interests, more useful knowledge, and more innovative ideas, that the classical Greek world experienced dynamic and sustained efflorescence, rather than settling into a low-performing premodern normal equilibrium. But why did the quality of information keep improving? A plethora of choices leading to greater specialization is an important part of the answer. Those choices were framed by rules that served to regulate competitive markets in information, goods, and services.1

In chapter 1, I posited that specialization—along with the cooperative exchange of goods and ideas, and conjoined with innovation-driven creative destruction—was a key to the rise (as well as to the fall) of classical Hellas. The number of economic specializations that are known from classical Greek sources is striking. Edward Harris has documented 170 different nonpublic-sphere Athenian occupations, most of them from outside the agricultural sector, and many involved in one form or another with production or exchange. While acknowledging that farmers made up the most numerous single occupational category, Harris argues that, at least in Athens, most resident foreigners and about half of the citizens worked outside agriculture. Assuming that this is correct, and—as the evidence for urbanization and population density (ch. 4) seems to suggest—if Athens was not entirely exceptional in having a substantial nonagricultural population, we will need to revise, or at least to reinterpret, long-prevalent assumptions about the Greek economy.2

In the words of the Cambridge historian, Paul Cartledge, “the ancient Greek world was massively and unalterably rural.”3 This was no doubt true, in the sense that agriculture did remain the single biggest sector. Highly specialized, relatively urbanized, trade-intensive classical Greece certainly remained much more oriented around agricultural production than is the case in any developed-world modern economy. But what I take to be the ordinary connotations of the phrase “massively and unalterably rural” will need to be adjusted if we hope even to describe, much less to explain, the efflorescence of classical Hellas.

EXPLANATORY HYPOTHESES

In chapters 6–11, we will examine in detail historical examples of choices leading to classical Greek specialization, innovation, and creative destruction. Here, based on the theory of decentralized cooperation set out in chapter 3 and the evidence for Hellas’ wealth presented in chapter 4, I offer two related hypotheses to explain how and why a particular set of political institutions typical of the classical Greek world (especially, but not uniquely, manifest in democratic Athens) provided Greeks with good reasons to make choices that resulted in Hellas growing wealthy.4

Hypothesis 1 |

Fair rules (formal institutions and cultural norms) promoted capital investment (human, social, material) and lowered transaction costs. |

Hypothesis 2 |

Competition within marketlike systems of decentralized authority spurred innovation and rational cooperation. Successful innovations were spread by learning and adaptive emulation. |

The first, “fair rules, capital investment, low transaction costs,” hypothesis is related to the second, “competition, innovation, rational cooperation,” hypothesis. Each requires (per ch. 3) valuable information to be actively and regularly exchanged and shared among many individuals. Egalitarian institutions, by creating a fair playing field and limiting expropriation by the powerful, fostered competition and innovation. Lowering transaction costs lowered the costs of movement, learning, emulation, and thus of technological and institutional transfer. Learning in turn increased human capital and local and collective stocks of useful knowledge. Capital investment, competition, innovation, and rational cooperation, in a context of low transaction costs, drove increased economic specialization. Although, for purposes of testing, it is useful to look at each hypothesis individually, the two hypotheses can be combined into a general explanation for the classical Greek efflorescence:

Fair rules and competition within a marketlike ecology of states promoted capital investment, innovation, and rational cooperation in a context of low transaction costs.

I suggested in the preface that among reasons to care about classical Greek efflorescence is that it emerged in the context of democratic exceptionalism—rules, civic culture, and values that have a more-than-superficial similarity to attractive features of contemporary democratic society. It is, however, necessary to keep in mind that classical Greek rules, even in the most developed states, favored adult male citizens. Rules were fair only in a relative sense—when compared with the norms typical of premodern states. They fall far short of the demands of contemporary moral theories of “justice as fairness.”5 Likewise, the level of classical Greek innovation was not high enough, nor transaction costs low enough, to satisfy a modern market economist.

Per the argument developed in chapter 3, the high-level phenomenon of Hellas’ wealth is causally related to the microlevel of more or less rational choices made by many social, interdependent, justice-seeking individuals. Efflorescence was not a result of central planning, nor did any Greek have the conceptual means to measure or to explain the phenomenon. Like the collective behavior of ant nests as quasi-organisms, classical Greek wealth was an emergent phenomenon. That phenomenon was shaped by social-evolutionary processes that tended to select functionally efficient rules in a highly competitive environment. Rules were made self-consciously, by legislators, individual and collective. But the process by which rules were selected and distributed across the ecology was outside the control of any individual agent. The wealthy Hellas effect arose from uncounted individual choices but was not readily predicted by them.6

Before turning to the role of fair rules, capital investment, competition, and rational cooperation, other often-cited features of the classical Greek world—geography, climate, location, and exploitation of non-Greeks—deserve further attention. It seems unlikely that a marketlike ecology of citizen-centered Greek city-states would have arisen under various imaginable conditions of geography, resource distribution, and climate very different from the conditions that in fact pertained in the Greek world. Nor could the classical Greek social ecology have arisen without the prior collapse of Mycenaean civilization—a collapse that was both of the right sort (severe, long duration) and at the right time (the dawn of the Iron Age) to set the stage for a new social order.7 By the same token, natural conditions and exogenous shock were insufficient, in and of themselves, to bring about the phenomena we are seeking to explain.

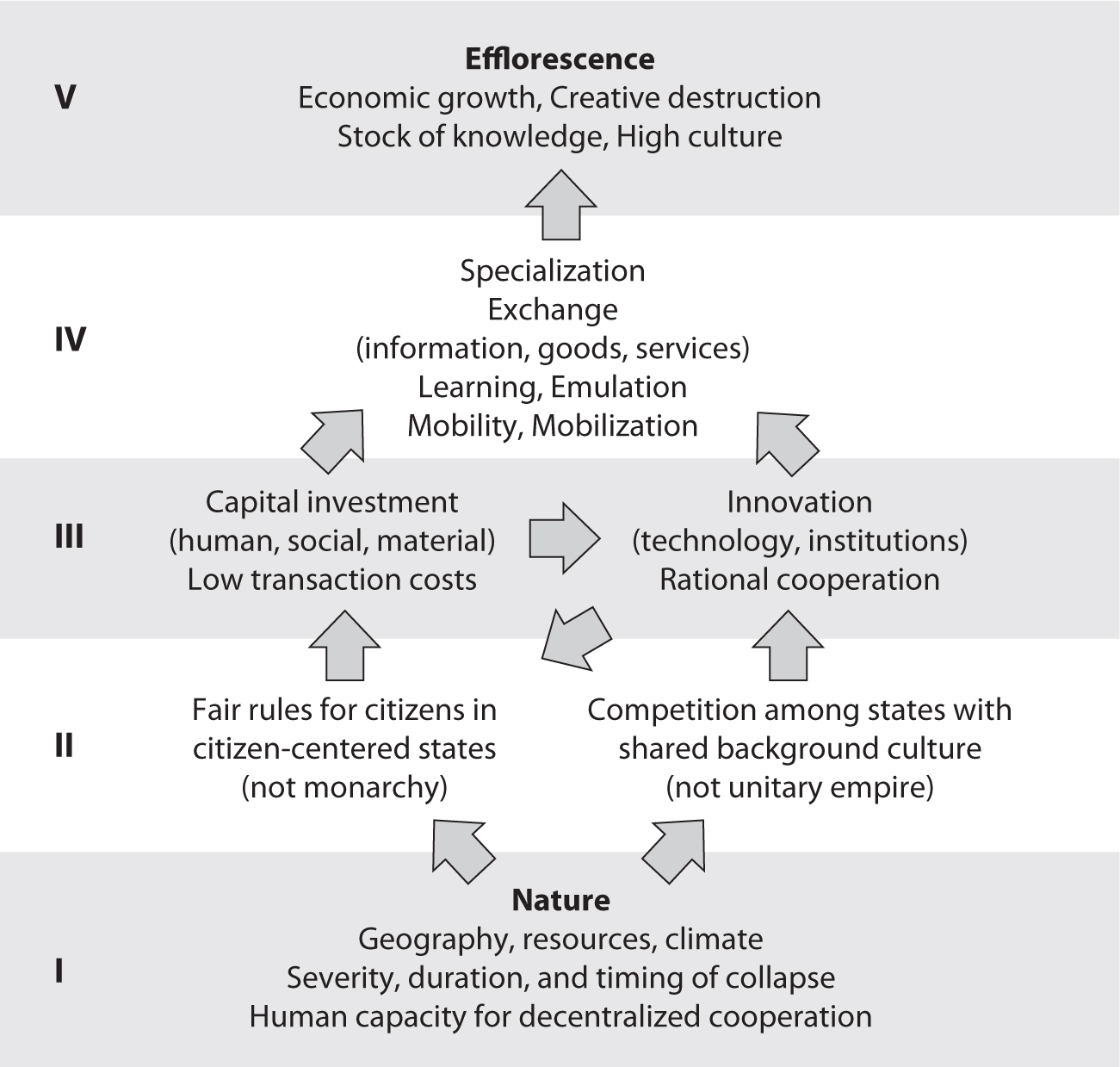

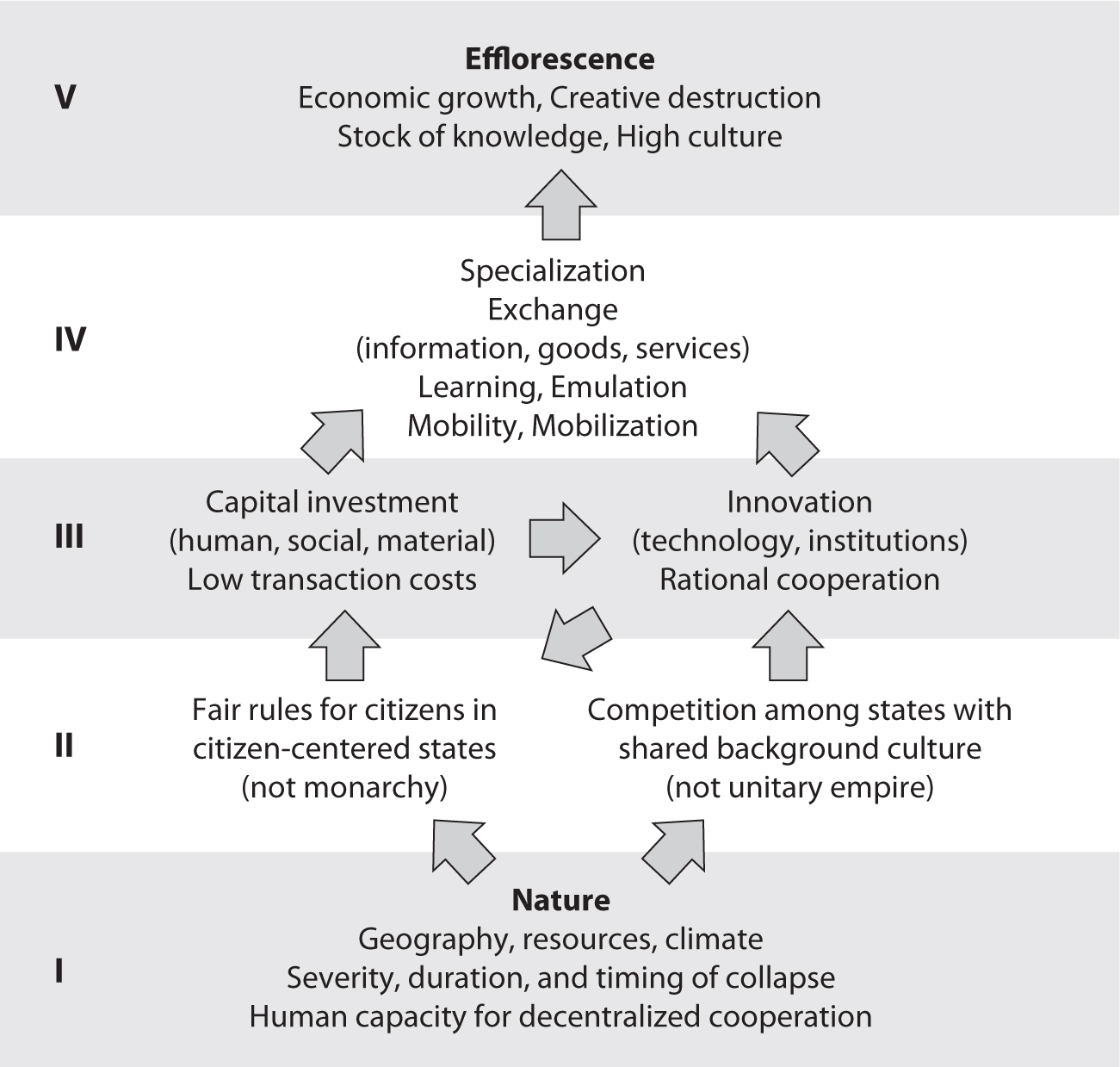

My explanation of classical efflorescence is illustrated schematically in figure 5.1. “Nature” provides the inherent human capacity for decentralized cooperation through information exchange (discussed in ch. 3) and a framework of geography, resources, climate, and collapse.8 In this chapter, I focus on the causal role played by fair rules and competition—that is, on the political inputs of institutions and civic culture that arose after the accidents of nature established humans as beings with certain political capacities, provided a specific geophysical framework, and threw in a powerful shock with the Early Iron Age collapse. Before proceeding, we should consider whether natural conditions, along with the factor of exploitation, might, in and of themselves, explain enough to relegate politics to the realm of epiphenomena.

FIGURE 5.1 Origins of efflorescence in a marketlike ecology of citizen-centered states.

NOTES: The two hypotheses developed in chapter 5 are intended to explain how, after nature has set the framework at level I, the political inputs of level II and behavioral choices of levels III–IV lead to the outcomes of level V. At levels II and III, Hypothesis 1 is on the left side, and Hypothesis 2 on the right side. The two hypotheses are integrated at level IV. The early emergence of the basic polis framework during the Early Iron Age and archaic period, in response to the accidents of “nature” (level I) are discussed in chapter 6. The economic outcomes (level V) are detailed in chapter 4.

CLIMATE, LANDSCAPE, LOCATION, EXPLOITATION

The Greek world’s geophysical conditions and location—including topography, climate, natural resources, and exposure to disease pools—unquestionably played a role in Greek history over the long run. As we have seen (ch. 2), most of the territory once occupied by ancient Greeks shares a rare (in global terms) “Mediterranean” climate. A substantial change in the climate of the Mediterranean basin has sometimes been invoked to explain ancient Greek population growth. A recent metastudy of rainfall and temperature changes in the eastern Mediterranean over the past 8,000 years has documented a long-term drying trend beginning around 2600 BCE. The study showed no evidence of a sustained regional trend toward the consistently cooler and wetter conditions that have been posited as a driver of long-term Greek population growth. Within the general frame, however, there appears to have been an especially arid period from around 1450 to 850 BCE, roughly coinciding with the Early Iron Age (EIA) collapse.9 Other recent studies suggest that this era of aridity precipitated the EIA collapse.10 At the other end of our era, the centuries from ca. 100 BCE to 200 CE—the height of the “Roman Warm,” which may have begun as early as ca. 350 BCE—were an era of relatively moister and warmer conditions. These centuries are coincident with the height of the Roman Empire. Within every climatic period there was subregional and short-term variation in temperature and rainfall, but the Roman Warm era seems to have seen much less variation than the periods preceding and following it.11

It is certainly plausible that aridity was a precipitating factor in the EIA collapse and that the end of a period of exceptional aridity enabled the population of Greece to climb back toward the premodern normal. Other, less pronounced, changes in temperature and rainfall may have had some effect on general or regional Greek social development. But, in contrast to the Roman Warm, there is as yet nothing in the known climate record of the first millennium BCE that would readily explain the intensity or duration of the classical Greek efflorescence, much less its historically distinctive framing in an extensive system of decentralized authority.12

As we have seen (ch. 2), the Mediterranean world is naturally subdivided into many microregions, each with distinct resources and microclimates. Microclimatic diversity, along with the uneven distribution of important natural resources (e.g., copper, silver, timber) contributed to making the Mediterranean basin especially well suited for the emergence of complex networks of short- and medium-distance trade. Mainland Greece has striking geophysical features: notably, a highly indented coastline with many offshore islands and a topography characterized by small agricultural plains amid rugged but not impassable mountains. The Mediterranean world was relatively easy for maritime traders to move around in. But by the same token it was quite difficult for would-be conquerors to master, especially those who (like the Achaemenid Persians or steppe nomads) relied heavily on cavalry. The mountainous Greek terrain offers certain of the geophysical features that the political anthropologist James C. Scott has documented as contributing to “the art of not being governed” by inhabitants of upland southeast Asia.13

The geography and climate of Greece were certainly potential assets, but focusing on these relatively invariant conditions leaves us with the question, raised in chapter 1, of why Greece experienced a remarkable efflorescence only beginning in the period 800–300 BCE. Why, if climate and geophysical conditions were the drivers of efflorescence, was Greece not similarly prosperous long before or long after that era? As we have seen (fig. 1.1 and ch. 4), although there were earlier (Middle Bronze Age Minoan) and later (fifth–sixth centuries CE) periods of efflorescence, there was nothing in Greek antiquity comparable to the efflorescence of the classical era. Greece did not have a particularly high-performing economy in the medieval or early modern periods; Greece’s modern economic record has been mixed at best. So, if geography and climate are to explain the phenomenon of wealthy Hellas, we need to know why these conditions proved especially valuable in 800–300 BCE and why they did not produce equally remarkable and sustained growth in much earlier and later eras.

The classical Greek world benefited from its location among extensive and well-integrated economic zones managed by great empires (notably Persia and Carthage). Classical Greek authors, for their part, claimed that mainland Greece (and especially Athens) occupied a particularly advantageous location in respect to trade.14 There were profits to be reaped by Greeks who served as Mediterranean middlemen, exploiting a favorable location between the environmentally and economically diverse regions of western Asia (especially after the consolidation of the Persian Empire in the sixth century BCE), northeastern Europe, and northern Africa (with its two great civilizations, Egyptian and Phoenician). A somewhat similar situation pertained in the Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman periods. Yet in those later periods, Greece was no longer even nominally politically independent—and Greeks were therefore subject to paying rents to an external imperial center.

Political independence may have helped classical Greeks to benefit from their location relative to big imperial economies, which might help to explain the efflorescences of the Minoan and late Roman periods.15 But, pace the standard ancient premise, which linked independence with poverty, sustained classical-era Greek political independence, in the face of Persian imperialism, was at least in part a product of Greek wealth: Large numbers of oared warships and many well-trained infantrymen, all financed by a thriving economy, proved essential to the preservation of Greek independence (ch. 7). So here we confront what social scientists call “the problem of endogeneity.” It is the exceptional wealth of classical Hellas that we are seeking to explain. If wealth is part of the location-based explanation (because wealth helps sustain political independence and independence conspires with location to create exceptional wealth), then location, in and of itself, is no longer an adequate explanatory factor. Location may, of course, be part of a causal explanation, but even in conjunction with geophysical conditions and climate, location cannot be the cause, pure and simple.16

Exploitation (in the strong sense of rent-seeking, rather than the weak sense of benefiting from favorable market conditions, on which see ch. 9) provides another possible explanation: The wealth of classical Hellas was certainly based in part on rents. The economic performance advantage of classical Greece, relative to other premodern societies, might be explained if we could show that the Greeks extracted more rents at a lower cost than did other premodern societies. There is no doubt that Greeks extracted substantial rents. In the period of classical efflorescence (as before and for a long time thereafter), Greeks employed various forms of nonfree labor, including historically innovative forms of chattel slavery.17 Athens gained very substantial revenues from subject states in the fifth century BCE, during the acme of the Athenian Empire.18 Moreover, the classical Greek world gained indirectly from forms of political domination and economic exploitation in regions at its periphery. In at least some cases, domination and exploitation in these peripheral regions arguably emerged because of, and were sustained by, Greek consumption. Grain exported to Athens at below-market prices by friendly Thracian dynasts may be construed as Athenian rents.19

Yet if we are to explain Greek economic performance by reference to rent extraction via exploitation and domination, we need to answer a prior question: Why were the Greeks (or the Athenians in the imperial period) able to extract more rents than other premodern societies? It seems implausible to explain this (hypothetical) rent advantage as a matter of will, by claiming that Greeks (or Athenians) had fewer moral qualms about exploiting and dominating in their own interest than did people in other premodern societies. If, on the other hand, something distinctive in Greek institutional development facilitated more effective rent extraction, then we are back to square one: If we posit that exceptional growth was based on exceptionally effective rent extraction, we must explain how the Greeks managed to gain rents that were “left on the table” by other societies, which were no less willing to dominate and exploit.

One explanation of why Greeks were able to exploit others as slaves or serfs is that the relatively large “middling” population of the Greek world rendered exploitation more efficient, because close cooperation among many middling citizens enabled them to dominate outsiders and control slave populations more efficiently. Sparta, with its many helots (ch. 6), and democratic Athens, with its many chattel slaves and (for a time) imperial subjects (ch. 8), might be cited as two, somewhat different, cases in point. Similarly, we might suppose that high real wages and a large “middling class” of consumers made widespread slave-owning more economically feasible.20 Yet we are, once again, confronted with an endogeneity problem: The large middling (suprasubsistence) population of the Greek world is an aspect of the general wealthy-Hellas phenomenon we are seeking to explain. So to the extent that coordination among middling citizens and high real wages are parts of the exploitation-based explanation, exploitation becomes inadequate as a standalone causal factor.

Due attention to geography, climate, geophysical conditions, location relative to other societies, and exploitation must be part of any serious attempt to explain the performance of the Greek economy. Yet even in the aggregate, these factors are inadequate to explain the phenomenon of wealthy Hellas. In the rest of this chapter, I develop the two explanatory hypotheses introduced above. Here the hypotheses are laid out in general terms, at the level of social theory. If it is to be believable as an explanatory account of the real world, a social theory must be empirically testable—in this case, by reference to the evidence of history. In subsequent chapters, we will test the two hypotheses by reference to the narrative of Greek history, from the Early Iron Age to the Hellenistic era. This method allows us to ask whether or not actual changes, over time and in different parts of the Greek world, are parsimoniously explained by the theoretical framework. The test of the theory is how well its predictions are confirmed by the actual historical record.

I do not claim that the hypotheses sketched above and developed below are fully adequate, in and of themselves, to explain the classical efflorescence. I am aware that each of my hypotheses suffers from the same problem of endogeneity that I raised above, in reference to other explanations. That is to say, the phenomenon I am seeking to explain, Greek wealth and cultural achievement, eventually became a driver, as well as a product, of fair rules and of competitive innovation. Institutions and civic culture productive of specialization, continuous innovation, and learning cannot be the whole story behind the classical efflorescence. But without understanding how distinctive Greek institutions promoted increases in productivity and in the value of exchanges, we cannot explain why and how classical Hellas became exceptionally wealthy.

In the following two sections, I illustrate the hypotheses with a few examples of Greek, mostly Athenian, institutional history. As we see in subsequent chapters, Athenian institutional development was exceptional in many particulars, and we need to juxtapose development in Athens with other paths to (and away from) development in other Greek poleis. Yet the institutional features highlighted here were not unique to Athens, or to other superpoleis; they are what made the classical Greek efflorescence such a distinctive chapter in world history.

FAIR RULES, CAPITAL INVESTMENTS, AND TRANSACTION COSTS

The first hypothesis for explaining the phenomenon of Hellas’ wealth during the era of classical efflorescence centers on the general Greek (and especially democratic Athenian) commitment to what I will call “rule egalitarianism.” Rule egalitarianism means in practice that many people within a society, rather than just a few elite people, have equal high standing in respect to major institutions: e.g., to property, law, and personal security. They have equal access to information relevant to the effective use of those institutions and to the information produced by institutions (e.g., laws, public policy). They are treated as equals by the public officials responsible for enforcing institutional rules. In sum, they can expect to be treated fairly. In an ideal rule-egalitarian society, all people subject to the rules would be treated as equals. In the Greek world, those enjoying equal high standing were, in the first instance, the adult male citizens—although, in some poleis, equal standing in respect to certain institutions was eventually extended beyond the citizen body.

Rule egalitarianism drove economic growth, first by creating incentives for investment in the development of social and human capital, and next by lowering transaction costs. A rule-egalitarian regime produces rules that respect individual equality of standing, as opposed to establishing a strictly equal distribution of goods. Yet rule egalitarianism has substantial distributive effects: Equality in terms of rules pushes back against extremes of inequality in the distribution of wealth and income. Rule egalitarianism may best be thought of as a limited form of opportunity egalitarianism. It is limited because equality of access and treatment is in respect to institutions and public information, not to all valuable goods. Of course someone committed to rule egalitarianism might also be an outcome egalitarian and/or a full-featured opportunity egalitarian—but the classical Greeks were neither. The key points are, first, that it is possible for a society to be committed, as the most developed states of classical Greece were, to equality for citizens in respect to rules governing standing without being committed to complete equality of outcomes or all social opportunities, and, next, that more equal rules tend to moderate extremes of wealth and income inequality through progressive taxation and limiting opportunities for rent-seeking by the powerful.21

It is uncontroversial to say that classical Greek society was characterized by historically exceptional levels of equality in terms of access of native males to key public institutions. The norms and rules of Greek communities tended to treat native males as deserving of some level of standing before the law, association in decision-making, and dignity in social interactions. No Greek community was ever rule-egalitarian “all the way down”—women, foreigners, and slaves were never treated as true equals. But among native males, the level of equality was remarkable when compared to other premodern (indeed pre-twentieth century CE) societies. A turn to relatively stronger forms of egalitarianism in Greece began in the eighth century, and the general trend continued (although not without interruption) through the classical era.22

In many classical Greek poleis, rule egalitarianism among native men was codified as citizen-centered government. In focusing on the citizen, Spartan-style citizen aristocracy and Athenian-style participatory democracy may be regarded as strikingly different versions of the same general regime type (chs. 6 and 7). Some Greek communities were, in George Orwell’s memorable phrase, more equal than others. But even Greek oligarchies were strikingly egalitarian by the standards of most other premodern societies. The constitutional development of individual polis communities was certainly not uniformly in the direction of greater equality of access and treatment for natives. Yet, with the increasing prevalence of democracy (chs. 9–11), the median Greek polis was more rule-egalitarian in the later fourth century BCE, at the height of the classical efflorescence, than it had been 500, 300, or even 100 years previously.23

Social norms and rules that treat individuals as equals can have substantial effects on economic growth by building human capital—that is, by increasing median individual skill levels and by increasing the aggregate societal stock of knowledge. Relative equality in respect to access to institutions (e.g., law and property rights) and to the expectation of fair treatment by officials within institutions encourages investments by individuals in learning new skills and increases net social returns to employment of diverse skills. It does so because norms and rules that protect personal security, property, and dignity lessen fear of the powerful.

When I believe that my person, property, and standing are secure (in that I have ready institutional recourse if I am assaulted, robbed, or affronted), I am less afraid that the fruits of my efforts will be expropriated arbitrarily by those more powerful than I. In this case, I have better reasons to seek my fortune and to plan ahead. It is rational for me to invest in my own future by seeking out domains of endeavor in which I can do relatively better—that is, to seek a relative economic advantage through specialization. I also have a higher incentive to invest effort in becoming more expert within that specialized domain, insofar as I believe that there is a market for that sort of expertise—so that the return on my self-investment will have a good chance of being positive. Under these conditions, I will rationally choose to defer some short-term returns by spending time and energy gaining information and developing skills that I believe will enable me to do better in the long run.24

The Greeks were not strangers to the idea of incentives and pursuit of rational self-interest, and they certainly understood the correlation between ambition, achievement, and equality of standing. When Herodotus sought to explain the break-out of Athenian military capacity after the democratic revolution of 508 BCE, he argued that “while [the Athenians] were oppressed, they were, as men working for a master, cowardly, but when they were freed, each one was eager to achieve for himself.”25 If we are to judge by their literature, ancient Greeks had a solid “folk” understanding of how individuals make choices in light of strategic calculations of interests centered on expected utility and anticipation of others’ behavior. Although the Greeks lacked a general theory of prices and markets, rules protecting individuals from exploitation, and subsequent individual choices to invest in human and social capital, led to the emergence of a vibrant market-based economy.26

Rationally chosen individual investment in human capital development can, in the aggregate, have powerfully positive economic effects through increasing societal levels of specialization and productivity. By investing in learning, each individual becomes correspondingly better at whatever endeavor in which he or she is engaged. Individuals who choose to invest in themselves, who have freedom to seek out different domains, and who have specific natural capacities (e.g., high intelligence) have reason to seek out those domains in which their capacities can be more effectively exercised. So, for example, an intelligent individual may pursue some sort of knowledge-intensive work rather than manual labor-intensive subsistence farming. Societal productivity increases because greater specialization of economic function produces more diverse goods more efficiently and because workers in each specialized domain, having invested in gaining expertise, are individually more productive. If information about the quality and availability of goods is widely shared, then better goods are produced at a lower cost, enabling more people to consume a diverse range of goods at a higher level.

Even in the absence of a general economic theory, little of this notion was lost on the classical Greeks. In the introductory section of Plato’s dialogue, Protagoras, for example, a young Athenian citizen named Hippocrates (not the famous medical writer) expresses his hope of receiving specialized training from the sophist Protagoras. Hippocrates’ boundless eagerness to learn something of value, and his willingness to pay for it, points to a culture of self-conscious investment in one’s own education. In Xenophon’s Memorabilia, Socrates urges a friend to recognize the human capital represented by the skills possessed by his female dependents and their motivation to employ those skills: “everyone works most easily, speedily, best, and most pleasantly when they are knowledgeable in respect to the work.”27 In the fifth and fourth centuries BCE and continuing into the Hellenistic era, the Greek world saw a spate of technical writing in a variety of fields: basic introductions to areas of expertise (for example, medicine, warfare, and public speaking) aimed at an audience eager to learn—and especially at potential students, like young Hippocrates, who might be willing to pay expert teachers in their drive to improve their own special skills.

Meanwhile, per the discussion of exploitation, above, specialization was also a way for the Greeks to increase gains from the forced labor of slaves. Greek states (see ch. 9) and individual slave owners alike invested in human capital by buying skilled slaves and training slaves in specialized skills.28 But slaves were not mindless machines. As the Greeks realized, slaves made behavioral choices that affected productivity. Writing in the later fifth century, the anonymous author known to classical scholars as Pseudo-Xenophon (also known as the Old Oligarch) notes that slaves in Athens would not be economically productive if they feared arbitrary expropriation. Moreover, he claims that the Athenian citizens who owned slaves recognized this behavioral fact and passed laws protecting slaves from arbitrary mistreatment accordingly (Ath. Pol. 1.11–12). We do not know how much practical protection this legislation actually afforded Athenian slaves, but the general point is that the economic value of increasing human capital, by establishing appropriate rules governing conduct, was manifestly appreciated by the classical Greeks.

Along with providing citizens, and at least certain noncitizens, with institutionalized security against arbitrary expropriation, some Greek states encouraged investment by citizens in learning skills relevant to the provision of valuable public goods, notably security and public services (e.g., clean water, drainage, reliable coinage, honest market officials) that conduce to the general welfare. Public goods benefited all citizens, and in, some cases, all members of the community.29 In Athenian-style Greek democracies, incentives, in the form of pay and honors, were offered for providing public goods through public service. The opportunity to perform public service was made readily available to all citizens by opening access to decision-making assemblies and by the use of the lot for selection of most magistrates and all jurors. At Athens, by the fifth and fourth centuries BCE, incentives included pay for service as a magistrate, a juror, or an assemblyman. Incentives offered to citizens who gained the skills necessary to be an effective provider of public goods included not only pay but also honors and sanctions. Those individuals whose service was deemed especially valuable by the community were rewarded with public proclamations and honorary crowns. Those whose service fell short, on the other hand, faced the potential of both legal punishment and social opprobrium.30

A third set of rule-egalitarian incentives for human capital investment came in the form of institutions that limited certain forms of individual risk.31 All things being equal, people are more likely to make capital investments with potential upside benefits when the risk of downside loss is limited. Suppose, for example, that I am a subsistence farmer; my family has a median income that translates into 5.5 L of wheat per day: i.e., 1.6 × basic subsistence (see ch. 4). I have the opportunity to take on a potentially lucrative new enterprise, but only if I invest in myself and/or members of my family learning some new skill. I have reason to believe that there is a good chance that the enterprise will be successful and if it is successful, it will elevate my family to the relatively greater security of middling status (say, an income of 3 × basic subsistence). But the new enterprise means less time spent on Subsistence farming. If there is a realistic risk that the failure of the new enterprise will leave my family beneath the level of subsistence (i.e., threatened with annihilation), I am unlikely to take on the new enterprise. If, however, I believe that the worst that can happen is that my family will fall to say, 1.3 × the level of subsistence (we will consume less but will not starve), I am more likely to take on the new enterprise.

Likewise, if a non-elite family knows that its own resources are its only protection against famine, accidents resulting in loss of working capacity, or death of the head of family in war, the required risk-buffering strategies usually preclude capital investments that offer potential long-term gains. Along with the high rents imposed by landlords and rulers, the high cost of private risk insurance is a structural impediment to the growth of most premodern economies.

State institutions that insure citizens against potentially catastrophic losses may enable individuals and families to invest more capital in enterprises with the potential for increasing individual welfare. Such policies raise the specter of moral hazard—that is, privatizing the gains of risk-seeking by distributing profits to the risk taker, while socializing losses by requiring others to pay for gambles that fail. But if a risk-limiting insurance institution is properly designed (i.e., part of the loss is borne by the risk taker), it serves an equalizing function that may have the effect of increasing aggregate welfare. Aggregate welfare is promoted because the state, unlike a single family, can spread risk of crippling accident or death in war across a large pool and can stabilize food prices in the face of local crop failure by encouraging imports from distant markets and by diplomatic agreements with producer-states. Getting the overall institutional design right is no simple task. But if the design challenge is met, the playing field is leveled because, for the poor, the stakes of embarking on a path of attempted self-improvement are lowered from potential disaster to survivable loss. And so the poor family can reasonably afford to take a risk that would previously have been open only to a wealthier family.

Assuming (as we have in the hypothetical scenario sketched above) that high-benefit enterprises are readily available and that the chances of success are better than even, the right policies, over time, lead to more people advancing from relative poverty to middling status. Although some risk takers will suffer losses, and so their families will be poorer, and some producers will be negatively affected by paying higher taxes, the net effect is positive for overall economic growth. Greek “public insurance” institutions (best documented for Athens, but not unique to Athens) included grain price stabilization and subsidization (reducing the risk of famine), welfare provisions for invalids (reducing the risk of loss of work capacity), and state-supported upbringing of war orphans (reducing the risk of military service by heads of families). Finding the right balance, such that the rules allowed risk-taking without inflating moral hazard, and such that the incentives of producers were not dampened by excessively heavy taxation, was a matter of institutional innovation and experimentation. We look at how public insurance institutions were developed and how they worked in practice in chapters 9 and 11.32

Examples of economically valuable individual human capital investments in the Greek (and a fortiori Athenian) world that could plausibly have been promoted by rule equality include literacy, numeracy, and mastery of banking and credit instruments. Other, perhaps less obvious, investments in human capital included military training, mastering various aspects of polis governance (e.g., rhetoric and public speaking, public finance, civil and criminal law), and individual efforts to build bridges across localized and inward-looking social networks.33

Another centrally important determinant of economic performance is the cost of exchanging goods and services. Voluntary transactions enhance social welfare insofar as they benefit both parties to the exchange (without harming others), that is, insofar as each party fares better than if the transaction had not taken place. Under such conditions, the more transactions that are undertaken, and the greater the benefit to each party, the better the economy performs as a whole. All things being equal, the more it costs each party to undertake a transaction relative to the expected benefits, the less likely it is that a mutually beneficial transaction will take place. So, once again holding all other factors steady, higher transaction costs depress economic growth; lowering transaction costs, by the same token, promotes growth.34

Rule egalitarianism can be a major factor in lowering transaction costs because inequality, in respect to access to information relevant to a transaction, or in respect to access to and fair treatment within the institutions potentially affecting a transaction, drives up transaction costs. Relevant sorts of information include, for example, the laws governing market exchanges; weights, measures, and quality standards; and the reliability of the currency in circulation. Institutions relevant to transaction costs include property rights, contracts, and dispute resolution procedures.

In the case of unequal access to information or to fair institutions, the disadvantaged party must raise the price of the goods or services in question to discount for the missing information or lack of institutional support. As the price goes up to cover these “inequality costs,” the benefit of the exchange to the other party drops accordingly. And thus, either the transaction between the parties is carried out with less aggregate benefit, or it fails because no mutually beneficial price could be arrived at. In the opposite situation, where information and access to fair institutions are more equal, transaction costs are lower and thus economic growth is (at least potentially) higher. As the political scientists Douglass North, John Wallis, and Barry Weingast demonstrate, the high transaction-cost, access-limiting social order that they call the “natural state” is historically common. Such societies can be stable, but they tend to be economically unproductive relative to societies characterized by more open access to information and institutions.35

Relatively egalitarian institutional regimes, like those of Greek city-states, ought, according to the transaction-cost argument sketched here, to be (all else being constant) more economically productive than rule-inegalitarian regimes. Moreover, the transaction-cost benefit ought to increase if access is made more equal over time. In fact, Greek weights and measures were standardized in several widely adopted systems in the archaic and classical periods (chs. 6–9). In the case of democratic Athens, access to information and institutions did become somewhat more open and equal as the laws were increasingly standardized (e.g., in the legal reforms of 410–400 BCE), better publicized (e.g., by being displayed epigraphically), and more efficiently archived (chs. 8–9). The Athenian state provided traders with free access to market officials and specialists in detecting fraudulent coins. Parties to certain commercial transactions were put on a more equal footing with the introduction of the special “commercial cases” in which resident foreigners, visitors, and probably even slaves had full legal standing. These developments are discussed in more detail in chapter 9.

COMPETITION, INNOVATION, AND RATIONAL COOPERATION

The second hypothesis for the wealth of classical Hellas is that economic growth was fostered by competition, innovation, and rational cooperation. innovation and cooperation were driven by competition. Competition among individuals to create more high-value goods and services and to provide more valued public goods (and to be compensated accordingly with pay and honors) was promoted by the even playing field created by fair rules equalizing access to institutions and information. Meanwhile, competition between states within the decentralized city-state ecology created incentives for cooperation among many individuals with shared identities and interests. Competition also promoted innovation in institutions faciliating interpersonal and interpolis cooperation. Innovation and cooperation, in the context of low transaction costs, encouraged interstate learning and borrowing of institutional best practices.

Continuous innovation is a primary driver of sustainable economic growth; the economist William Baumol emphasizes that societies dependent on stable regimes of rent extraction, rather than continuous innovation, face low and hard ceilings restricting growth. Today we often think of economically productive innovations as technological; improved energy capture (use of fossil fuels) was, for example, a major driver of the historically remarkable rates of economic growth enjoyed by some relatively highly developed countries in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Highly successful technological advances that spread quickly through the Greek world and beyond include the oil lamp, terra cotta roof tiles, and wine.36

Although the classical Greek world unquestionably benefited from these and other technological advances, technological development does not seem likely on the face of it to account adequately for the intensity and duration of the classical efflorescence. Technology is, however, only one domain in which continuous growth-positive innovation is possible. The Greek world was arguably a standout in its development of new public institutions that served to increase the level and value of social cooperation without resort to top-down command and control. Valuable institutional innovations were spurred by high levels of local and interstate competition, and they were spread by the circulation of information and learning.

Just as it is uncontroversial to say that the Greek world was, when compared to other premodern societies, comparatively egalitarian in its norms and formal rules, so too it is uncontroversial to say that the Greek world was characterized by high levels of competition. The competition among Greek communities could be a high-stakes affair, potentially ending in the loss of independence, loss of important material and psychic assets, or even annihilation. The high level of competition between rivals placed a premium on finding effective means, institutional and cultural, to build and to sustain intracommunity cooperation. One of the basic lessons that the fifth century BCE Greek historian and political theorist Thucydides offers his readers (positively in Pericles’ Funeral Oration in book 2, negatively in the Corcyra civil war narrative in book 3) is that communities capable of coordinating the actions of an extensive membership had a better chance to do well in high-stakes intercommunity competitions.37

Social institutions can provide both incentives for cooperation and mechanisms for facilitating coordination, and classical Greeks were well aware of this potential.38 One result of endemic Greek intercommunity competition was, therefore, a proclivity to value cooperation- and coordination-promoting institutional innovations: A state that succeeded in developing a more effective way to capture the benefits of cooperation across its population gained a corresponding competitive advantage vis-à-vis its local rivals. Notably, as has recently been demonstrated in detail, and contrary to the “standard modern premise,” in the classical era many Greeks (and a fortiori the Athenians) had freed themselves from “the grip of the past” in that they were quite willing to embrace the positive value of novelty in many domains.39

Greek communities readily learned from one another. Every new institutional innovation was tested in the competitive environment of the city-state ecology. Many innovations were presumably performance-neutral—that is, they had no significant effect on the community’s relative advantage in competitions with rivals. Other innovations would, over time, prove to be performance-negative. If, however, an innovation adopted by a given polis was believed to have enhanced that polis’ performance, there would be prima facie reason for other poleis to imitate it.

There were, of course, many reasons for polis B not to imitate polis A’s performance-positive institution. Most obviously, the new institution might be disruptive to polis B’s existing social equilibrium, a disruption that would, among other undesired outcomes, result in a net loss of cooperative capacity. Classical Sparta was a case in point. The Spartan social system was overall resistant to disruptive innovation, which proved a disadvantage in the early phases of the Peloponnesian War.40 Yet in other cases, the perceived chance to improve polis B’s performance, and thus do better relative to its rivals, would be a sufficient incentive to adopt polis A’s innovation. The Spartans eventually recognized the need to adapt; they did so by developing a substantial navy in the later phases of the Peloponnesian War (ch. 8).

Some innovations, such as the federal leagues of central Greece, were widely adopted across certain regions (ch. 9). Other highly successful innovations were adopted across the polis ecology. Widely (although never universally) adopted institutional innovations that we consider in the next chapters included coinage, euergetism, the “epigraphic habit,” diplomatic arrangements, theater, and cult.

Of course not all Greeks, and not all Greek communities, were equally innovative or equally willing to emulate successful innovations developed elsewhere. But the Greek world overall saw what appears to be a strikingly high level of institutional innovation and emulation across the ecology of states over the 500 years from the beginning of an age of expansion in about 800 BCE to the classical peak in the late fourth century. Major domains of institutional innovation, considered in the next five chapters, include citizenship, warfare, law, and federalism. In the domain of state governance, both democracy and oligarchy were especially hot areas of institutional innovation and interstate learning. And, ominously for the continued independence of the leading Greek poleis, interstate learning readily jumped from city-states to potentially predatory central-authority states, through the medium of highly mobile Greek experts. Several such states were developing quickly on the frontiers of the Greek world in the fourth century BCE, an era in which expert mobility seems to have reached new peaks.41

Within the city-state ecology, a regional hegemon might encourage or discourage adoption of a given institution. Oligarchical constitutions were required by Sparta of the ca. 150 states of the fifth century BCE Peloponnesian League (Thucydides 1.19). Meanwhile, in the later fifth century, Athens imposed monetary and weight standards on the 300+ states of the Athenian empire.42 Yet, as we have seen, there was no general central authority in the classical Greek city-state ecology to mandate when or how widely a given innovation was adopted across the ecology as a whole. The extended city-state environment thus operated as something approaching an open market for institutions. Opportunities for imitation were facilitated (transaction costs lowered) by the ease of communication across polis borders, which was in turn facilitated by the shared culture of the Greek world. Some impediments to institutional learning between modern nations, e.g., differences of language and religion, were much less salient in the Greek world.43 Because this “market in institutions” favored the development and dissemination of more effective modes of social cooperation, Hellas grew wealthier—and meanwhile, Hellenism grew increasingly attractive to some of Greece’s neighbors.44

PROSPECT

The “fair rules, capital investment, low transaction costs” and “competition, innovation, rational cooperation” hypotheses, taken together, suggest an explanation, not only for why Hellas grew wealthy through increased specialization, but also for the creative destruction of inefficient rule-inegalitarian institutions and for the high culture of the archaic and classical periods—the new and influential forms of art and architecture, literature, visual and performance art, and scientific and moral thought that so impressed Byron. The classical efflorescence is at least partially explained by the conjunction of deep investment in human and social capital, low transaction costs, continuous competitive innovation and rational cooperation—all of which increased incentives to specialize, exchange, and learn.

Individuals and communities alike obviously benefited from higher levels of economic specialization and higher value exchanges of goods and services. The chance to gain greater payoffs—fame and honor as well as wealth—drove incremental improvements in existing domains (heavy-infantry tactics, lyric poetry) and led innovators to pioneer new domains (light-armed infantry tactics, tragedy and comedy). Innovations spread readily across the ecology (Doric and Ionic architectural orders, epic poetry).

Advances in communications technology (alphabetic writing) were quickly adapted to multiple domains (poetry, philosophy, law, contracts). Goods and services developed in the high human capital/low transaction cost/innovation-and-learning-driven Greek context were readily exported to regions on the periphery of the Greek world (red-figure pottery; mercenary soldiers, doctors, architects). In return, the Greeks imported grain, raw materials (timber, tin, copper)—and labor in the form of slaves.

In order to be of real explanatory value, hypotheses must be testable and at least potentially falsifiable. The two hypotheses offered here as explanations for classical Greek efflorescence can be tested by examining changes over time in individual poleis and the Greek world as a whole, differences among communities within the Greek world, and differences between Hellas and other premodern socieites. The explanandum (i.e., the thing we are seeking to explain; in the language of social science, the dependent variable) is the rapid and sustained growth of wealth, in Hellas as a whole and in individual poleis, across the period 1000–300 BCE. The “fair rules, low transaction costs” hypothesis would be falsified as an explanation (i.e., as an independent or explanatory variable) if, as wealth increased, rule-egalitarian institutions declined across the Greek world. Likewise, it would be falsified if, when we compare poleis, there proved to be a negative correlation between wealth and egalitarian rules. If the least egalitarian poleis were also the wealthiest, the hypothesis must be wrong. The “competition, innovation, rational cooperation” hypothesis can be falsified by showing a negative correlation between innovation and wealth: If the poleis that were most institutionally conservative were also the wealthiest, then continuous innovation cannot be the right explanation for why Hellas was wealthy. The narrative of Greek history traced in the next six chapters supports neither falsification condition.

Two final questions remain before we turn to historical narrative. First, do we really need two explanatory hypotheses? Social science values parsimony in explanation. Assuming chapter 4’s claims about the extent and growth of Hellas’ wealth are right, are both hypotheses developed in this chapter actually needed to explain the phenomena? Can we reductively dispense either with fair rules, capital investment, and low transaction costs or with competition, innovation, and rational cooperation as an explanatory variable?

The answer, I believe, is no. Although, as noted above, the two hypotheses can be conjoined into a single statement, in order to account for the phenomenon of the growth of wealth in the context of what we know about the history of the Greek world, we must invoke both fair rules/capital investment/low transaction costs and competion/innovation/rational cooperation. But this in turn means that we ought to be able to test the interdependence of the hypotheses. One preliminary test is to ask whether especially important and widely adopted institutional innovations tend to push toward or away from fair institutions featuring equality of access to information. The development of democracy and federalism, as, respectively, particularly strong forms of rule-egalitarian intra- and interpolis cooperation, offer us particularly salient test cases. In the coming chapters, we consider how prevalent democracy and federalism actually became across the Greek city-state ecology in the classical and immediate postclassical eras.

Finally, how was the Greek efflorescence sustained for so long? The basic answer (illustrated in figure 5.1) is that ongoing advances in exchange and specialization were driven by continued innovation and capital investment, provoked by unrelenting competition and sustained by strong institutions. However, as the example of independent medieval cities shows, under some conditions civic institutions that initially produce high levels of innovation and growth, over time, predictably lead to stagnation.

David Stasavage, a political scientist at New York University, has recently demonstrated that an autonomous (citizen self-ruled) city in medieval Europe could expect a higher rate of population growth (Stasavage’s proxy for economic growth) than a comparable dependent city under the control of monarchical states—for about 100 years following the onset of independence. Thereafter, the growth rate of autonomous cities was slower than that of dependent cities. Stasavage suggests that this fast-then-slow growth pattern was a product of how institutions affected rates of innovation and trade. Initially stimulated by strong property rights and protection from outside interference, innovation and trade in autonomous medieval cities was, in the long run, stifled by restrictions on competition and limits on entry to institutions. Those restrictions and limits were enacted by citizen-rulers who were members of merchant and craft guilds, eager to protect their own monopolistic interests. Since kings had different interests, they imposed fewer restrictions and limits in cities under their control. We might expect independent Greek city-states, in which self-interested citizen-rulers controlled access to institutions, to have followed a similar fast-then-slow innovation, trade, and growth trajectory. Yet the evidence suggests that they did not.45

There are many differences between the governments of medieval European and classical Greek cities and between the contexts in which they operated. Among the salient differences is the tendency of some of the most developed Greek cities to increase access to institutions over time. Access was opened both by expanding the percentage of the adult male population exercising active citizenship and by broadening civil rights for at least some noncitizens. In the next six chapters, we trace the historical factors that led citizen-rulers in Greek cities to make choices in respect to access that were quite different from those made by the rulers of independent medieval cities. Those choices had profound consequences for the level and duration of the classical efflorescence.