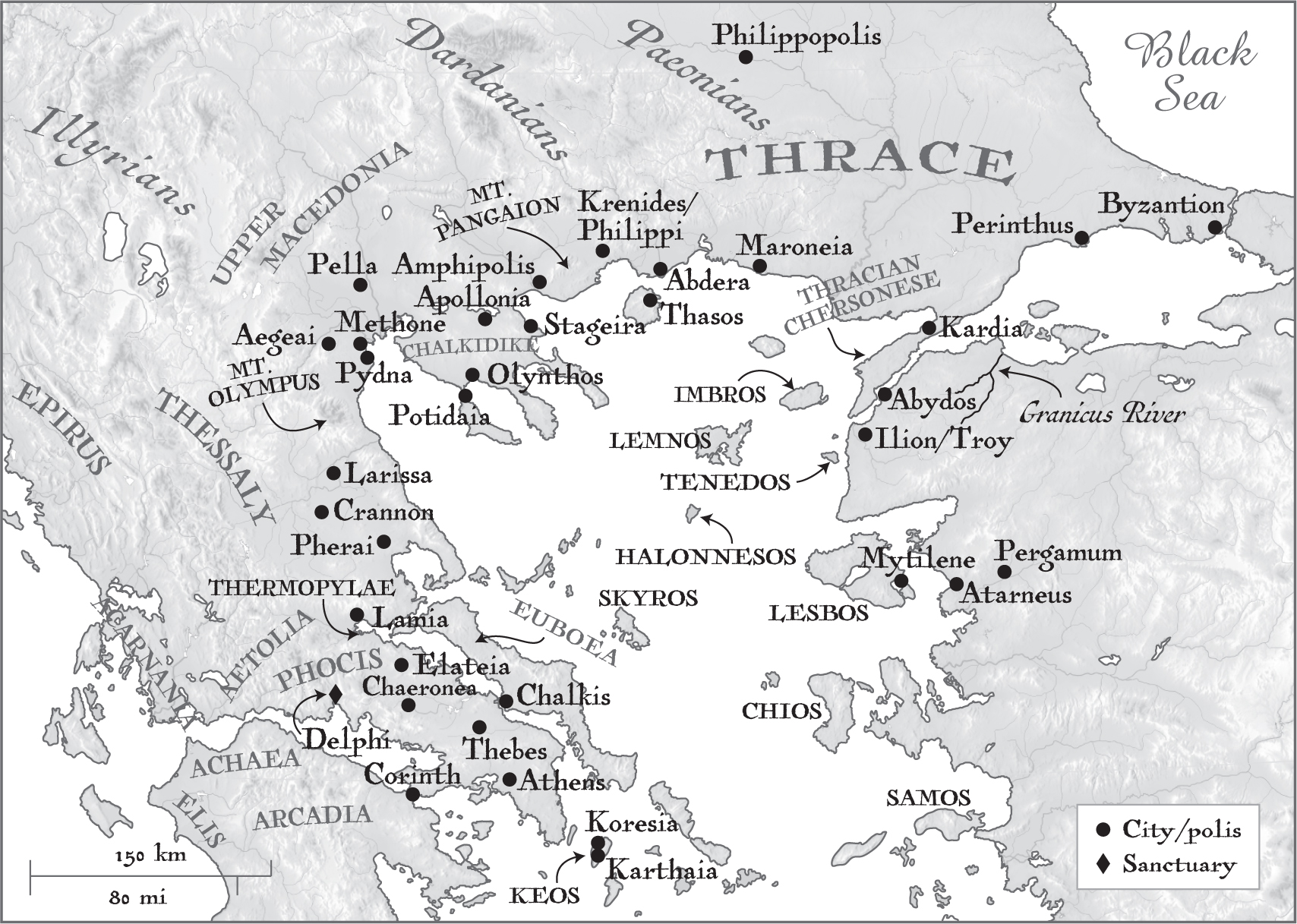

MAP 9 Northern Aegean Greek world, mid-fourth to third century BCE.

POLITICAL FALL, 359–334 BCE

THE TERMINATION OF THE CLASSICAL ERA

LOOKING AHEAD

Warfare was rife in the half century after the Peloponnesian War. Yet, with the exception of Leuctra, where Sparta’s long run as a superpolis abruptly ended in 371 BCE, there were few truly decisive battles. That changed in the seventh decade of the fourth century, when a series of battlefield decisions remade the Greek world: In 338, at Chaeronea, Philip II of Macedon defeated a Greek alliance led by Athens and Thebes. His victory ended the era in which great and independent poleis dominated the Aegean world. Philip’s son, Alexander III “The Great,” then brought down the once-mighty Persian Empire in three battles in 334, 333, and 331. Having spent the next decade expanding and partially consolidating an empire that eventually stretched east to the Indus River, Alexander returned to Mesopotamia, where he died in Babylon in June 323. Revolts against Macedonian rule that broke out in Greece upon the news of the king’s death were quickly suppressed.

The Hellenistic era of Greek history, from the death of Alexander to the Roman takeover in the second century BCE, was dominated by Macedonian dynasts and, in Sicily and south Italy, by their Greek imitators. A few city-states, notably Rhodes, remained fully independent and centrally important in Mediterranean affairs. Syracuse became the capital of a Sicilian kingdom. The Achaean and Aetolian federal leagues (ch. 9) periodically broke free of Macedonian royal control. But from the later fourth century into the early second century, many poleis paid tribute taxes to one or another of the Hellenistic kings. Some key cities, including Athens, Chalkis, and Corinth, periodically received Macedonian garrisons.

The diminution of the role of great and independent Greek poleis in Mediterranean history in the late fourth century BCE is the political fall that had been averted by the successful fifth century resistance to Persia and Carthage.

This chapter answers the question of why and how Philip and Alexander of Macedon succeeded in defeating a Greek coalition led by two great poleis, whereas Darius and Xerxes of Persia had failed in their earlier attempts. The political fall of Hellas in the later fourth century was precipitated, at least in part, by the Macedonian kings’ masterful appropriation of the by-now familiar instruments that had driven Hellas’ economic rise in the preceding centuries: specialization and expertise, developed as a result of the deep investments in human capital, along with competitive emulation of successful technological and institutional innovations. In the final chapter (ch. 11), we explore the relationship between the political fall and the robust persistence of economic growth, federalism, and democracy in a transformed ecology of city-states.

THE “OPPORTUNISTS”

The sudden rise of Macedon in the mid-fourth century was not the historical equivalent of a “crater of doom” meteor strike, terminating a thriving ecology at a stroke.1 Rather, Philip emerged as the most successful of a group of very effective, highly ambitious, and at least semi-Hellenized dynasts who ruled territories on the fringes of the Greek world in the early to mid-fourth century BCE. Several of these rulers posed serious problems (as well as employment opportunities) for certain of their Greek neighbors, and they shared some methods in common. John K. Davies of the University of Liverpool aptly dubbed the members of this informal club “the opportunists” because each of them borrowed opportunistically (that is, selectively, seeking their own advantage and that of their community) from Greek culture and institutions. Each made extensive use of Greek experts—notably including mercenary soldiers, commanders, and designers of military systems. “Opportunist” is not meant here as a derogatory term—we might just as well call the Hellenized dynasts of the fourth century “the entrepreneurs.” And of course they were hardly unique in their opportunistic borrowing: As we have seen, the emulation of institutions and technology among Greek states was a primary driver of the classical efflorescence.2

Prominent dynasts on the margins of Hellas included Evagoras and Nicocles, rulers of Salamis on Cyprus; Jason and Alexander of Pherai (i414), each sometime master of Thessaly; Mausolus and Artemisia II of Caria; and Hermias of Atarneus (i803) in northwestern Anatolia, Aristotle’s father-in-law and patron. The opportunists’ club also included other ambitious and semi-independent governors of Anatolian provinces in the Persian Empire; the Thracian and Scythian rulers of new and emerging Black Sea states from which the Greek poleis imported great quantities of wheat; Tachos of Egypt, and other rebels who from time to time broke free of the Great King of Persia. At a further remove, but in the category of states beyond the Greek world that made effective and selective use of Greek expertise, were the Carthaginians and the Great King himself.

The opportunists’ employment of Greek experts would threaten the Greek world (rather than the ambitions of specific Greek states) only if it put the overall ecology of independent poleis at risk. As it turned out, the danger posed by most of the opportunists, even to individual Greek states, was episodic. The Great King had retaken the Anatolian poleis, and, for a time, major Aegean island states, including Samos and Rhodes. As we have seen (ch. 9), some poleis suffered under the Persians, but overall the Persian-ruled Anatolian Greeks did quite well in the fourth century. The Carthaginians were fought to a standstill by the tyrants of Sicily and then by Timoleon; Carthage ended up controlling about a third of Sicily, but no more. Jason and later Alexander of Pherai were assassinated before realizing their full potential as leaders of a united Thessaly. Mausolus died soon after launching his challenge to Athens in the Social War of 357–355; his successors were less threatening to Athenian interests.

Philip of Macedon stood out among the fourth century opportunists. He shared their taste for selective features of Greek culture, and, like them, he employed Greek experts to his own ends. But he went his fellow dynasts one better in various ways. As a leader, Philip possessed many of the characteristics that Thucydides had so admired in Pericles: He was a subtle diplomat, a superb manager of men and money, a bold and astute military strategist. He had a focused and a far-sighted vision of what his state might accomplish and of what natural and human resources would be required in order for his vision to be fulfilled.

Like Dionysius I of Syracuse, Philip made creative use of advances in military technology and actively pursued new technological advances. Like Epaminondas of Thebes, Philip saw the value of military training and experimented successfully with novel battlefield formations. Philip innovated in combining cavalry, light infantry, and heavy infantry. He employed both strategic pursuit of defeated enemies and strategic foundation of cities. Moreover, Philip was lucky, if not in his total life span (born in 382, he died in 336 at age 46), then both in his relatively long reign and in his heir. Unlike the other leading opportunists, Philip ruled for long enough (23 years: 359–336 BCE) both to expand and to consolidate his state. Moreover, upon Philip’s death, his son, at age 20, was ready to assume control. Alexander quickly proved to be his father’s equal as a ruler, diplomat, strategist, and field commander.3

The Macedonian conquest of Greece was not inevitable. Philip’s career might have followed an arc similar to that of other opportunists: He suffered at least two life-threatening battlefield wounds before arriving on the plain of Chaeronea; either incident could have killed him before Alexander was ready to take over as Macedon’s ruler. Like Jason and Alexander of Pherai, Philip was assassinated by a trusted member of his inner circle. His death came two years after he had beaten the Greek allies at Chaeronea, but had an assassin struck a few years earlier, the Macedonian imperial state might have fallen apart before any decisive encounter with the great poleis of central Greece had taken place. If, upon coming to the throne in 336, Alexander had proven less than superbly competent, the effects of Philip’s victory at Chaeronea might have proved ephemeral.

Philip did very well in the domain of leveraging Greek expertise—his choice of Aristotle as a tutor for his son is exemplary. Each of the earlier opportunists, however, had also been skilled in the domain of borrowing expertise, as they were in various other domains (strategy, management) relevant to hegemonic ambitions. Had one of the earlier opportunists been luckier in regard to his length of reign and heir, Philip might have been beaten to the punch; Macedon might have been absorbed into someone else’s empire. On the other hand, in counterfactual worlds in which one imagines that Philip died before consolidating the Macedonian state, or that his heir was not his equal, other opportunists could have emerged as existential threats to the Greek world—Darius III, as Great King of Persia, is among the plausible candidates.

In sum, we ought not imagine that the political fall of Greece had to happen just when and just as it did—or that the loss of Greek independence was nothing more than a bizarre twist of fortune that sequentially placed two world-class military and organizational geniuses on the Macedonian throne. While the rapid rise of Macedon and the political fall of classical Greece could not have been predicted ex ante, they are certainly explicable ex post, when viewed against the wider context of the development of expertise relevant to empire-building and the mobility of that expertise in the late classical Greek world.4

MACEDON BEFORE PHILIP

Macedonia was a large and resource-rich region north and east of Thessaly and the Chalkidike Peninsula (map 9). It had long been connected culturally, economically, and politically to the mainland Greek world. But Macedonia also had historical and geographic connections with Epirus to the west, with tribal regions of inland Eurasia to the north, and with Thrace and Persian-ruled Anatolia to the east. Topographically, Lower Macedonia was centered on the fertile lowland plain formed by the Axios River in the south and east, while Upper Macedonia was an extensive zone of mountainous highlands extending west and north from Mt. Olympus. While Lower Macedonia lay within the Mediterranean climatic zone, Upper Macedonia lay outside it. Indeed, the Macedonian highlands may be generally defined as that part of the Greek peninsula lying outside the Mediterranean zone. As such, much of Macedonia was colder and wetter than the Mediterranean Greek world.

The history and culture of Upper Macedonia, especially, was nearly as foreign to the Greeks as that of Thrace or Scythia. Macedonia was rich in natural resources that were rare in the rest of Greece. Upper Macedonia was especially famous for its timber, producing in abundance the large trees essential for ship-building and for the ceiling elements of monumental buildings, including temples, stoas, shipsheds, and military towers. Poleis like Athens that regularly constructed warships and large public buildings had strong reasons to seek access to Macedonian resources.5

The Inventory lists 17 poleis as having been established in the region of Macedonia by 323 BCE. I estimate the population of these poleis at 145,000, but the total population of Macedonia was certainly higher. Many Macedonians, especially residents of Upper Macedonia, lived in settlements not categorized as poleis. By the end of his reign in 336 BCE, Philip had created a Greater Macedonia that incorporated the coastal plain west of the Thermaic Gulf, the whole of the Chalkidike Peninsula, and much of coastal Thrace. Greater Macedonia was the core of an empire that, by 336, also included Thessaly, inland Thrace, Epirus, and the Greek mainland (map 9).

Philip sent an expeditionary force to establish a beachhead in northwestern Anatolia shortly before his untimely death. This move made it abundantly clear that he intended to continue Macedon’s imperial expansion to the east, into regions controlled by Persia. Although we cannot say how much of the Persian Empire Philip imagined he might conquer, Alexander went after the entirety of the Great King’s domain—and more. By the time of Alexander’s death in 323 BCE, the king of Macedon ruled over the largest empire the Western world had ever seen. But none of that could have been foreseen when Philip came to the throne in 359 at age 23. Before Philip, the king of Macedon had not been a major player, even on the Greek scene—much less an existential threat to the greatest of the Greek poleis and to the Great King himself.

As early as the Persian Wars of the early fifth century, the Greeks regarded the king of Macedon as within their orbit—if not exactly as one of themselves. Alexander I (who ruled ca. 498–454 BCE) was reputed to have brought the Greeks intelligence of the Persian advance early in the great Persian Wars of 481–478. By the end of the fifth century, the Macedonian court was sufficiently Hellenized to have become the “off-off Broadway” of Greek tragedy: Euripides ended his career by producing his plays for Macedonian audiences. Some elite Macedonian social customs were, however, still regarded as typically “barbarous” by the Greeks—notably the Macedonian symposium, at which heavily armed men downed mass quantities of undiluted wine (wine was always mixed with water in a proper Greek symposium). The impression of barbarism was not reduced when, as sometimes happened, drunken arguments escalated into murderous violence.

Much of Macedonian society before Philip appears to have been essentially feudal. Macedonian nobles were in some ways reminiscent of Homeric heroes, glorying in hunting, feasting, and war. They were willing to follow a king into battle if he was a strong leader but limited in their loyalty to the weak Macedonian state. While most Macedonians practiced monogamy, as did the Greeks, the Macedonian king (at least as exemplified by Philip and Alexander) might take multiple wives, perhaps in imitation of the practice of Persian royalty. How culturally or linguistically “Hellenic” the general Macedonian population was in the age before Philip II, or even a generation after his death, remains controversial. It is in any event unlikely that most Greeks in the fourth century regarded most Macedonians as truly Greek—or for that matter that most Macedonian elites regarded the citizens of Greek city-states as their own social peers.6

Unlike the polis-dwelling Greeks to their south, the Macedonians had long been at least nominally ruled by kings. The royal capital was, by the early fourth century, located at the town of Pella (i543: size 4) on the Axios River plain. Aigeai (i529: size 2), the former capital, was situated some 35 km to the southwest and remained an important ritual center. It was also the royal burial ground and the site of some extraordinary late fourth century tombs, one of which has been (somewhat dubiously) identified as that of Philip II. Macedonian kings were invariably drawn from the extended Argead lineage. In a familiar bit of specious and self-serving mythologizing (cf. the Athenian myth of Ion as founder of the Ionian ethnos: ch. 8), the Argead clan traced its ancestry to Herakles. The royal succession did not, however, necessarily pass from father to son. The succession seems to have been based on “necessary if insufficient” conditions of bloodline and competence. When there were multiple plausible heirs, the choice was presumably made by a coalition of powerful Macedonian elites. Kings were acclaimed, but not elected, by the Macedonian army.7

Macedon can best be understood as a basic “natural state,” centered on a ruler and his elite coalition, in which rents were distributed according to the potential for violence. Although “Macedonian” was a recognized status and some Macedonians were citizens of poleis, Macedon as a state certainly had no pretentions to being a citizen-centered order. Any movement in the direction of more open access was carefully controlled. The authority of a king of Macedon was not based on a formal constitutional system but on the king’s personal capacity to mobilize an army and to command the loyalty of other powerful Macedonian families. Although there had been occasional strong Macedonian rulers—notably Archelaus I (417–399: Thucydides 2.100.2), most kings before Philip II had been relatively ineffective. The king’s authority was often undercut by bloody dynastic struggles. Plato (Gorgias 471a–d) offers a colorful account of how Archelaus I murdered his way to the throne. Royal authority was further undercut by the independence of the barons of Upper Macedonia and by strategic meddling by major poleis of central Greece.

In the earlier decades of the fourth century, both Athens and Thebes maneuvered to place their own chosen pretenders on the Macedonian throne. The resources of Macedonia, especially its abundant stands of timber, were highly valuable, and those resources were more accessible when Macedonian central authority was weak enough to be readily manipulated. The Macedonian state was, moreover, periodically threatened by Persia to the east, and by Illyrian, Triballian, and Paeonian tribes to the west and north. In the early fourth century, there were new threats to Macedon’s standing: the emergence to the south of the Chalkidike confederation, led by the great polis of Olynthos (i588: size 5); the consolidation of independent kingdoms in Thrace and Scythia; and the growing ambitions of the Thessalian dynasts, Jason and Alexander.8

PHILIP AND THE RISE OF MACEDON (359–346 BCE)

In 359 BCE, King Perdiccas III was killed on the western Macedonian frontier in a battle against Illyrian tribes. His brother, Philip II, took over as king. The new king faced challenges on multiple fronts. He bought time: first by paying off the Illyrians and Paeonians (presumably using reserves from timber sales and harbor dues, see the section in this chapter on “explaining Philip’s success”), and then by diplomatically false-footing Athens with vague assurances about his support for their claim to Amphipolis. Meanwhile, Philip took his first steps in the program of military reform that would, within a decade, fundamentally realign the power structure of the Greek world. before Philip, the Macedonian king had only limited military forces on which he could dependably rely: perhaps a small body of infantry and the “mounted companions”—an elite unit of light cavalry. Given the weaponry and tactics of the classical era, light cavalry was trumped by heavy infantry—especially when the infantrymen were well trained and backed up by light-armed slingers, archers, javelin throwers, and accompanied by their own light cavalry. Having been fostered to Thebes as a teenager, Philip knew all that. He recognized that without an army capable of taking on a sizable phalanx of Greek hoplites, Macedon would always be forced to serve the interests of better-organized states.9

Building a bigger, better trained, and more loyal army was the essential prerequisite to Philip’s ambitious plans for Macedon. The key to expanding the army was, first, more secure frontiers, and then successful imperial expansion into territories with fertile agricultural land. Spear-won land could be distributed to Macedonian families from the hardscrabble uplands in the form of grants of real estate contingent on the provision of young men for military service. Since conquered land belonged to the king, implementing this strategy made Philip the patron of a growing body of clients, thus bypassing the feudal relations that had bound ordinary Macedonians to local chiefs. When the barons realized that they could be end-run and thus made socially redundant, they chose to join the king’s coalition as their best remaining option.

The dynamic of growing royal power, driven by the imperative to recruit and train more armed men, and to distribute more land to them, meant that a logic of continuous territorial expansion underlay Philip’s reign. The king’s capacity to keep most of the barons in his coalition, working with him rather than plotting against him, depended on continuously growing the army, which in turn depended on building a Greater Macedonia. And build he did.10

Within a year of coming to power, Philip had recruited and trained an infantry force of 10,000 men. He used this force, in close coordination with several hundred cavalry, to win a major battle against the Illyrian tribes. That victory stabilized Macedonia’s western frontier and thereby helped Philip to lay the groundwork for at least somewhat greater royal control over Upper Macedonia. That in turn gave Philip access to a substantially increased population, from which he could recruit more soldiers—assuming he could pay them. Paying recruits with land (or promises of land) meant expanding to the east and south, where there were fertile agricultural tracts that might be distributed to Macedonian families who provided the king with soldiers. Those fertile lands were, however, controlled or claimed by powerful poleis.

In 357, in a surprise move, Philip besieged Amphipolis, the big (size 5), strategically located former Athenian colony that dominated the Strymon River valley—the region that lay immediately to the east of Lower Macedonia. The Athenians, who had never given up their claims to a city that had been independent for two generations, were shocked and outraged. But, as Philip must have known, they were tied up with their Social War against their former allies (who were being backed by Mausolus of Caria) in the north Aegean and unable to respond effectively to Philip’s gambit. Amphipolis fell; Philip took the Strymon valley and over the next three years systematically extended Greater Macedonia south and further east.

To the south, on the eastern and western shores of the Thermaic Gulf, Philip took, among other places, the cities of Pydna (i544: size 3), Potidaia (i598: size 2), and Methone (i454: size 1). In the east, on the south Thracian coast, he seized Apollonia (i627), Abdera (i640: size 5), and Maroneia (i646: size 5). In addition to his military victories, Philip also made strategic alliances, often cemented with dynastic marriages: In Illyria (wife Audata), in Epirus (wife Olympias), in Thessaly (wives Nikesipolis and Philinna), with the Chalkidikean League, and with certain of the Thracian kings (wife Meda). As we have seen (ch. 9), in the later 350s Philip campaigned against the Delphi-robbing Phocians in support of his allies in Thessaly. Philip beat the Phocians at the Battle of the Crocus Field in 352 but was turned back at the pass of Thermopylae by the Athenians when he sought to move south in order to consolidate his victory. This was, as events soon showed, only a temporary setback.11

In 356, Philip had made one of the most fiscally significant territorial acquisitions of his reign. The town of Krenides (i632), located 45 km east of Amphipolis and 15 km inland from the Thracian coast, between Mt. Pangaion to the west and a southern spur of the Rhodopian range, was the primary processing center of a productive gold- and silver-mining region. Control of the mines had been hotly contested since the sixth century by Athens, Thasos, and various Thracian dynasts. Philip refounded the town a few kilometers to the east and renamed it Philippi (i637: size 2)—among the first known instances in the extended Greek world of a founder naming a city for himself. According to Diodorus (16.6.6–7) Philip’s control of the Pangaion mining region substantially enriched the Macedonian king, increasing his revenues by more than 1,000 talents per annum—a sum equivalent to Athens’ annual revenues in the high imperial era preceding the Peloponnesian War.

The main part of the new mineral resource revenue stream may not have come on line immediately, but in the mid-340s Philip was minting silver tetradrachms on a large scale. Instead of the Athenian weight standard (tetradrachm weight 17.15 g), Philip used the weight standard that had previously been employed by the Chalkidikean League and Amphipolis (tetradrachm weight 14.5 g). Philip’s silver coinage circulated within Greater Macedonia and northward into inland Europe. But Alexander, Philip’s successor, switched to the Athenian weight standard, and within a generation, Macedonian coinage had overtaken Athenian coinage as the dominant form of exchange in the eastern Mediterranean world. Philip added to his repertoire by minting gold staters (weight 9.5 g). Greeks associated gold coins with the mints of the Great King, a fact that is unlikely to have been lost on Philip. Philip’s gold coinage was both voluminous and popular; it soon became the dominant gold coinage in the Aegean. Philip and Alexander were, in effect, at once emulating and competing with the minting practices of the Athenians and the Great King alike.12

Philip’s coins, both silver and gold, were produced to high standards; they were reliable in weight and precious metal content. They were also superb examples of the engraver’s art and must have made a splash when they first appeared in northern Aegean markets. Philip’s coins portray a god (Zeus or Apollo) on the obverse, and a mounted rider (generally believed to be Philip himself) on the reverse. They resemble the finest Greek coins in fabric, iconography, and craftsmanship. Yet unlike any of the coins issued by the city-states, even those minted under the auspices of the grandiose tyrants of Syracuse, Philip’s coins advertised the ruler’s own name: each was stamped Philippou—belonging to (i.e., minted by) Philip. Greek coins were typically stamped with an abbreviated form of the name of the minting state (e.g., ΑΘΕ: Athe[nians]). By the age of Philip, if not before, the Macedonian state was the king. Philip’s style of silver and gold royal coinage set the standard for the gigantic coinages of Alexander and later Hellenistic kings. In his coinage, as in other ways, Philip both built upon classical Greek practice and introduced innovations pointing toward the postclassical era of Greek history.

By 352, just eight years after Philip’s accession to the kingship, Macedon had moved out of the shadows and had joined the ranks of the greatest powers of the extended Greek world. Over the next six years, Philip consolidated and extended his position. After the collapse of his alliance of convenience with the cities of Chalkidike, he besieged and, in 348, captured Olynthos, giving him effective control of the entire peninsula. The surviving population of Olynthos was enslaved or expelled; the city itself was looted and sacked. Because the site was never substantially reoccupied, excavations at the ancient site of Olynthos have provided archaeologists an extraordinarily comprehensive example of fourth century Greek domestic architecture and assemblages. Prominent among the small finds are Macedonian arrowheads and sling bullets engraved with Philip’s name.13

Having failed to relieve either Amphipolis in 357 or Olynthos in 348, the Athenians now faced up to the new reality of Macedonian power, signing a treaty with Philip in 346 that is traditionally called the “Peace of Philocrates,” after one of the Athenian ambassadors. In the course of the protracted negotiations, the cities of Phocis surrendered to Philip. Although allied with Athens, they had been excluded from the truce at Philip’s insistence. The population of the cities of Phocis, like that of Mantinea earlier in the century (ch. 9), was dispersed to villages—thus angering the Thebans who had thought Phocis would be theirs to plunder.

Macedon was, by the mid-340s, the most powerful state in the Greek world—comparable to Athens in the 430s or Sparta in the 380s. Eight years later, at Chaeronea, when the Macedonian army proved superior to the united forces of Athens and Thebes, it would be clear that Macedon had exceeded all earlier city-state-based hegemonies. But in the immediate aftermath of the truce of 346 and the humbling of the Phocians, Philip focused on expanding his empire west, north, and east and on diplomacy aimed at preventing (or at least delaying) the formation of a potentially dangerous Athens–Thebes alliance.14

TO CHAERONEA (346–336 BCE)

In the eight years between the Peace of Philocrates and the battle of Chaeronea, Philip was busy consolidating the Macedonian Empire and extending it on several fronts. After suppressing restive poleis in Thessaly, he reorganized that large region under Macedonian-appointed governors. He campaigned in the north against the Illyrians and Paeonians. In the southwest, he extended his influence south of Epirus. In the east, he deposed Thracian and Scythian kings and incorporated much of inland Thrace into his empire. By early 338, as king of Greater Macedonia and archon of Thessaly, Philip ruled perhaps 1.25 to 2 million subjects.15

Meanwhile, Macedonian relations with Athens had worsened after the signing of the Peace of Philocrates. Some Athenian leaders, notably the orator Demosthenes, were never reconciled to Philip’s incorporation of Amphipolis into Greater Macedonia or with treating Macedon as Athens’ peer polity. Rightly or wrongly, Demosthenes and other Athenian hawks interpreted Philip’s ongoing campaigns in Thrace and his conquest of the small north Aegean island of Halonessos—a notorious pirate lair that lay about 30 km south of the Athenian-controlled island of Lemnos—as deliberate provocations. Philip offered to give Halonessos to Athens and proposed an expedition against Aegean pirates, to be carried out by the Athenian navy and financed by Macedon. Ambassadors went back and forth, but negotiations bogged down over, among other things, the question of whether Philip would be “giving” or “giving back” (as the Athenians insisted) Halonessos.

Philip sought to build alliances with leading central and southern Greek states—activity that Demosthenes interpreted in the worst possible light. In fact, Philip’s diplomatic successes in Greece south and east of Phocis were limited: For a short time in the late 340s, it appeared that Philip would bring the poleis of Euboea, the big island off Athens’ east coast, into his sphere. But Athenian diplomacy and military intervention turned the situation around, with the result that an independent Euboean League was formed that was friendly toward, if not formally allied with, Athens. Philip found some friends among the Peloponnesians, but there was no Peloponnesian state on which he could rely for military aid.

Exactly what Philip was aiming at in his “Greek policy” during this period has been much debated. It has been argued that he was already focused on the invasion of the Anatolian provinces of the Persian Empire, which offered the prospect of rich booty and fertile lands. Under this interpretation, his goal in central and southern Greece was stable peace rather than conquest, given that the cost of the conquest of Greece was likely to be higher than any possible payoff and that the payoff for invading Asia was likely to be high. This interpretation suggests that Philip’s negotiations with Athens were sincere and that the breakdown of the treaty was primarily due to warmongering Athenian leaders.

The alternative view is that Philip could not afford to contemplate an expedition into Asia until he had definitively eliminated the endemic and serious danger to Macedonian security represented by the independent states of central Greece, especially Athens and Thebes. The Peace of Philocrates had been a delicate balancing act that, from Philip’s perspective, avoided the unhappy prospect of Athens and Thebes uniting against Macedon. But that danger would remain until both great poleis had been defeated in battle. according to this latter interpretation, Philip was biding his time with insincere negotiations, waiting for the opportunity to crush his Greek rivals militarily. On the whole, this second interpretation makes more sense. Assuming that Philip did plan to invade Persia, and that such an invasion would take the Macedonian army a long way from Macedon and Greece, it is hard to see how the undefeated Greek states could have credibly committed not to exploit the situation.16

In the event, Philip’s imperial expansion eastward across Thrace and toward the Hellespont, along with Athenian determination to retain a strong presence in exactly this region, precipitated the final collapse of the Peace of Philocrates. By 341, Athenian generals stationed in the Thracian Chersonese on the west shore of the Hellespont were raiding Macedonian shipping and fighting what amounted to a proxy war against Thracian poleis allied with Philip. In 340 BCE, continuing his drive to the east, Philip threw an army of 30,000 into a siege of Perinthus (i678: size 5) on the south shore of Propontic Thrace. When Perinthus held out, he split his forces and extended his siege operations to nearby Byzantion (i674: size 5), thereby threatening to take control of the Bosphorus straits. If Philip took Byzantion, he would control the entrance to the Black Sea and could deny Athens access to its primary source of imported grain.

Athens now dispatched a fleet to reinforce Byzantion. The Great King independently sent aid to the two besieged cities, as did Chios, Rhodes, and Cos—the Aegean island states that had been Athens’ primary foes in the recent Social War. In the face of massive fortification walls, determined resistance, and substantial external support, both of Philip’s sieges failed. But in autumn of the year, his navy, still too small to engage the Athenian fleet in battle, managed to capture a big convoy of mostly Athenian grain ships. The transport ships were mustering at the Bosphorus, awaiting an Athenian military escort to take them, down the Propontis, through the Hellespont, into the Aegean, and onward to Piraeus. Philip appropriated the timber and grain from 180 Athenian ships. He let free the other 50 ships, bound for non-Athenian ports.

Athens and Macedon were by this point unquestionably at war.

The question now was which central and southern Greek states would join Athens against Philip—or vice versa. For his part, Philip found no new allies. Demosthenes led the Athenian diplomatic effort. Most Greek states chose to stay on the fence. The anti-Philip alliance included the Achaean League, Corinth, Megara, the Ionian Sea island states of Corcyra and Leukas (i126), and some of the poleis of Euboea and Acarnania (Demosthenes 18.237). But by far the most important addition to the Athenian alliance was Thebes. Philip had reportedly offered the Thebans the right to plunder Athens if they joined him. Demosthenes claimed that the Theban alliance was his own doing, the product of his persuasive skills. No doubt the initiative was his. But Thebes had a long and troubled history with Macedon. The Theban leadership must have realized that if Philip defeated Athens, Thebes would be left without significant allies. Philip would have little incentive to fulfill his promises and ample incentive to take down the last of the great independent states of mainland Greece.

Athens’ diplomatic efforts had resulted in an alliance of states with a total estimated population of something under 1 million people.17 As we have seen, Philip now probably controlled a population of 1.25–2 million. At least as important as total population, however, was the strategy dictated by the alliance. Athens’ success in creating a multistate alliance that included Thebes meant that the showdown with Philip would take the form of a land battle—rather than a war of attrition in which protracted sieges and naval maneuvers might play a major role in the outcome: Unlike Athens, Thebes’ strength lay in its heavy infantry rather than in its fortification walls or navy; the defense line must now be drawn in northwestern Boeotia, in advance of the city of Thebes. Demosthenes’ approach to alliance building either forced or enabled Philip to risk a major land battle against a substantial coalition—a battle that Philip might have lost but was probably quite confident that he could win.18

The Athens–Thebes axis meant that Philip was denied the option of continuing to pursue the incremental strategy of capacity building and imperial expansion that he had employed successfully since the early 350s. But on the other hand, a protracted war of attrition and maneuver might have made things more difficult for Philip: His last two major sieges had failed, and his navy was vastly inferior to that of Athens. Counterfactually, Athens might have chosen to employ against Philip a variant of Pericles’ strategy in the Peloponnesian War—that is, trusting to the walled city–Piraeus circuit to keep Philip at bay while seeking allies to help fund large-scale naval operations against his imperial assets in the north. Such a strategy would mean that, in the place of Thebes, Athens would have sought as its main allies the major poleis of the northern Aegean and the Great King—i.e., the states that had rallied against Philip during the sieges of Perinthus and Byzantion. It is impossible to predict what would have happened had that strategy been pursued; the point is that the breakdown of the Peace of Philocrates by 340 did not necessarily mean that the fate of the independent poleis of Greece would be decided by a set-piece land battle.

In the event, the showdown came in August 338. After a barrage of charges and countercharges of impious state behavior (reminiscent, mutatis mutandis, of the religious charges leveled by both Athens and Sparta before the Peloponnesian War: Thucydides 1.126–128), Philip was summoned to march in arms into central Greece by the Amphyctions of Delphi—the sanctuary’s managing board that Philip had effectively controlled since becoming master of Thessaly. Once south of Thessaly, Philip diverted his forces from his ostensible target (Locrian Amphissa: i158, accused of having impiously built on sacred lands) and seized the strategic Phocian town of Elateia (i180). The way into the Boeotian plain now lay open.

The anti-Macedonian allies responded quickly, mustering in the narrows of the plain, near the small Boeotian town of Chaeronea (i201: size 2). The opposing forces were similar in size, and each was primarily composed of heavy infantry and cavalry: Philip fielded some 24,000 Macedonian infantry, 6,000 allied infantry, and 2,000 cavalry. On the Greek side there were 12,000 Thebans, 6,000 Athenians, and 12,000 allied infantry, along with 3,800 cavalry. Altogether, there were on the order of 65,000 combatants on the field, certainly more than any in any land battle ever contested between Greek city-states.19

The battle was hard fought but never in doubt. The Macedonians were better led, well trained, armed with novel weapons (the sarissa), and battle-hardened. Thousands of allied troops were captured or killed—the dead included 1,000 Athenians and the entire Theban Sacred Band of 300 picked men. The surviving allied soldiers (including Demosthenes, who fought as an ordinary hoplite) fled the field. In stark contrast to the confused aftermath of the battle of Mantinea in 362 (ch. 9), Philip’s victory was decisive. As the historian Justin (9.3.71) put it, “For the whole of Greece, this day marked the end of its glorious supremacy and its ancient independence.”20

LEAGUE OF CORINTH

Thebes was forced to accept a Macedonian garrison, a narrowly oligarchic pro-Macedonian government, and the reconstitution of the Boeotian League on genuinely federal (rather than Thebes-dominated) lines. Corinth also surrendered and was garrisoned. The Athenians, by contrast, prepared for a siege. But Philip had little to gain from a protracted siege of a huge and heavily fortified city: We may assume that the 30,000 infantry he had brought to Chaeronea was as large an army as he could safely muster while leaving Macedon and Thrace properly garrisoned. A Macedonian army of similar size had failed to take Perinthus. Besieging Athens would be a more daunting undertaking than Perinthus and Byzantion combined—and all the more so if the Great King saw it in his own interest to support the besieged city, as he had two years before. It is hardly surprising, then, that Philip offered to negotiate a truce with Athens on reasonable terms: There would be no garrison or new government. Athens would cede control of the cleruchies on the Thracian Chersonese but would retain the strategic and productive islands of Lemnos, Imbros, and Skyros, along with Delos and the cleruchy on Samos. Athens accepted the terms.21

That winter (338–337 BCE), all major Greek mainland states, other than the now-irrelevant Spartans, sent representatives to meet with Philip at the headquarters he had established at Corinth. Here the Greeks agreed to a common peace, reminiscent of the King’s Peace of 387 (ch. 9). They also joined a Macedonian-led Hellenic federation known to history as the League of Corinth. Philip’s new arrangements borrowed freely from earlier and contemporary Greek practices, conjoining mechanisms familiar from Sparta’s fifth century Peloponnesian League, from the fourth century Athenian naval league, and from the central Greek federal leagues that had emerged in the late fifth and fourth centuries.

The peace and federation agreement signed by the member states specified that no state would act so as to harm the interests of Philip, or his descendants, or any of the other league states. Moreover, interstate constitutional meddling was strictly forbidden: Each state was to continue indefinitely with the constitutional arrangements it currently enjoyed—whether oligarchy or democracy. As had been the case in Sparta’s consistent support of Peloponnesian oligarchies in the fifth century, this entrenchment of existing regimes gave the ruling coalition in every member state a strong reason to prefer the Macedonian-guaranteed status quo. The league was to be headed by a leader (hegemon), but like the Athenian fourth century naval league, its council (sunedrion), made up of representatives from each of the constituent states, excluded the hegemon. Like contemporary federal leagues, the decrees of the league’s council regarding war, peace, and interstate relations were binding on its member states, but each state retained its autonomy in local affairs. As in these other successful federalized systems, the member states of the League of Corinth agreed, jointly, to punish defectors. Those who failed in the duty of punishment could expect to be treated in their turn as defectors by the other member states and, when necessary, by the hegemon.22

In its first formal meeting, in spring of 337, to no one’s surprise, the Council of the League of Corinth elected Philip as its hegemon, and he announced his plan for invading the Persian Empire. The ideological justification offered for the proposed attack was, first, borrowing from the Athenian playbook of the early fifth century, vengeance for Persian sacrilege and destruction during the Persian Wars. Next, borrowing from the Spartan playbook of the later Peloponnesian War, Philip proposed to liberate the poleis of western Anatolia from Persian domination.

There can have been little doubt in anyone’s mind that the actual purpose of the invasion was booty and land for Macedonians: The imperative to continuous imperial expansion, the dynamic Philip had set in train in the early 350s, had not changed. But expansion had been stalled during the last few years, while Philip had been settling affairs in Greece—whatever Philip’s true motives after 346, it was true that the cost of pacifying Greece exceeded any immediate material gains. Macedon needed to resume the full-throated imperialism that had been interrupted, at considerable expense to the king’s treasury, by the relatively muted (and not lucrative) imperialism represented by the League of Corinth.23

In spring of 336, Philip, who now controlled the Thracian Chersonese, established an Asian base of operations by moving 10,000 men across the Hellespont to Abydos (i765) in northwestern Anatolia. Several Anatolian poleis, including Ephesus (i844), some 260 km (straight line) to the south, broke with the Great King and declared for Philip. But the Great King had hired his own highly competent Greek military expert, Memnon of Rhodes, who defeated Philip’s lieutenants in several engagements.

Then, in July of 336, Philip himself was assassinated by a member of his bodyguard while officiating at his daughter’s wedding in the theater at Aegeai. The Athenians cheerfully passed a resolution honoring the assassin but otherwise stood pat: Having grasped the fact that their best hope for striking a favorable bargain was an impregnable city, they had spent the two years following Chaeronea modernizing their fortifications and building warships. The Thebans were bolder, expelling the Macedonian garrison and deposing the pro-Macedonian government.

Philip’s heir was up to the challenge. Upon being acclaimed as king of Macedon, Alexander moved quickly south to Corinth, where the council of the league duly declared him hegemon. In 335, after a lightning campaign in the northern empire against restive Illyrian tribes, he returned to central Greece, where he successfully besieged and then eliminated Thebes. The resident population of the polis was killed or enslaved. As with the destruction of Eretria and Miletus by the Great King in the early fifth century (ch. 7), Alexander demonstrated that he had no qualms about destroying one of the greatest of the Greek poleis if and when he was defied.

The next year, at the head of a large army that included substantial contingents from the states of the League of Corinth, Alexander crossed the Hellespont into Asia, declaring the continent to be his spear-won domain. Within three years, and after as many battles, the Persian Empire had fallen and the Greek world was about to be transformed. The classical era was ending; the Hellenistic about to begin.24

EXPLAINING PHILIP’S SUCCESS

How are we to explain the political fall of Greece? Appeal to Hellenic decline, in the form either of the putative weakness of individual Greek states or of divisions among them, does not get us far. It is certainly true that individually each of the greatest of the eastern Greek states—Sparta, Athens, and Thebes—was in 338 less militarily powerful than it had been at its historical peak: Sparta after Leuctra was a shadow of its sixth–fifth century self. Thebes had suffered in the wars of the 360s and 350s but still commanded a very large army as the dominant state of the Boeotian League. Athens, with a citizen population of about 30,000, was less populous than it had been a hundred years earlier, and state income was probably still well below that of the imperial peak. But Athens’ finances had recovered substantially from the Social War era low, and there were as many triremes in the shipsheds as there had been in the mid-fifth century. Overall, as we have seen (ch. 4), the population of mainland Greece appears to have reached all-time highs, and Hellas was remarkably wealthy by historical standards.

It is also true that Greece was far from united in 338: As we have seen, the states in the anti-Philip alliance had a total population of under a million; something on the order of 1.5 million Greeks in central and southern mainland Greece and the islands stood aloof.25 But division among the Greek states was nothing new. As we have seen in previous chapters, Greece had always been divided, insofar as there was never a “Leviathan” central authority capable of coercively coordinating the actions of “the Greeks” at scale and over time. Cooperative action among coalitions of Greek states was always predicated on shared interests, not obedience. After the Persian Wars, some 29 other Greek states had their names inscribed on the Serpent Column at Delphi as having joined Sparta and Athens in opposing the invasion. That coalition represented only a fraction of the total manpower of the mainland Greek world. In 338, the anti-Macedonian coalition put an army into the field that was equal in size to that of the invaders—something that the Greek allies had certainly not managed to do when faced with the Persian invasion. There is no reason to believe that the Greek soldiers in 338 fought any less well than their ancestors had done when facing the Persians at Thermopylae, Marathon, and Plataea. In brief, in seeking to explain the “political fall of Greece,” it is more informative to ask what Philip did right, rather than what his Greek opponents did wrong.

Philip took Macedon from relative weakness to greatness in a very short time. By defeating a coalition of leading Greek poleis, and then by bringing all of mainland Greece, along with Thrace, under a coherent hegemonic order, Philip succeeded where a sequence of empire-building city-states, with imperial populations roughly comparable to that of imperial Macedon before Chaeronea (table 2.3), had failed (chs. 8 and 9). Many details of how he accomplished all that remain murky, due to the fragmentary nature of our sources. But we can dispel much of the fog by making informed guesses based on the evidence we do have.

In many particulars Philip must be seen as a ruler of a continental (as opposed to coastal), resource-rich autocratic state (as opposed to a human capital rich, citizen-centered state). As such, he took an approach to empire-building that differed markedly from that taken by any Greek polis. Philip saw the possibilities offered by his world in different terms than did his southern neighbors. Unlike the polis-dwelling Greeks, Philip was not bound, culturally or otherwise, to a coastal littoral (ch. 2). He exploited inland natural resources (especially timber and, later, minerals), and he founded cities deep inland in Thrace—some 150–200 km inland from the coast—in order to promote overland trade.26

Once he had built a strong coalition that included the formerly independent barons of Upper Macedonia and an army of soldiers bound to him by patronage and grants of land, Philip possessed a degree of centralized control over state policy that no government of a citizen-centered state could hope to match. Philip’s authority, unlike a democratic or oligarchic polis government, was in principle indefinitely scalable, at least insofar as social cooperation was based on obedience and hierarchy (ch. 3). Unlike the natives of the Greek city-states, Macedonians were not used to thinking of themselves as citizens; the centralization of Philip’s authority does not seem to have been a problem for his Macedonian subjects. Philip certainly needed to attend to the concerns of the barons and soldiers in his extensive coalition. Like Alexander after him, Philip participated in the social-capital-building rituals of the Macedonian symposium and the military camp—joining in the dangers and pleasures of the men he led. He surrounded himself with talented individuals and depended on loyal lieutenants. But he did not need to clear his policy plans with a representative council, nor did he have to move legislation through a large assembly of independent and critical-minded citizens.

Philip’s position as Argead king gave him a degree of legitimacy as sole ruler that no Greek leader could aspire to. Since the king effectively was the Macedonian state, he was able to act more quickly and with less advance publicity than was conceivable in the world of the city-states. This was, as his polis-based opponents realized at the time, a substantial advantage in war and diplomacy. While he devoted a great deal of time and energy to military affairs, Philip was famous for his diplomatic acumen and was said to prefer a victory won by ruse to one gained by open combat. Moreover, the king was not bound by the rules that constrained the social behavior of ordinary mortals. Royal polygamy enabled him to cement political alliances through marriage alliances with other dynasts and to display his affinity for other regions. Unlike Greek leaders of citizen-centered states, or even Greek tyrants who ruled over men accustomed to citizenship, Philip could advantageously adopt some of the ideological apparatus of godlike kingship. While it is debatable how far he went in portraying himself as godlike, and exactly who were the intended audiences for his performances of divinity or near-divinity, there is no doubt that he went further in this direction than any Greek leader had ever dared.27

These various deviations from polis norms help to explain certain of Philip’s advantages in pursuing his imperial project—advantages that were denied to Athens, Sparta, Thebes, and Syracuse. But these deviations do not adequately answer a second question: Why did Philip succeed in the conquest of central and southern Greece, when the Great Kings of Persia, who would seem to have similar advantages and vastly greater resources, had failed? This question is more pointed insofar as once-popular explanations, based on the discredited assumption that the fourth century Greek poleis were impoverished or somehow degenerate, must be rejected in light of the evidence for classical efflorescence.

In order to answer the question of why Philip succeeded where Darius and Xerxes had failed, we need to look at the other side of the comparative coin—that is, how Philip’s Macedon was like an advanced fourth century Greek polis. The core similarity lay in a capacity to identify and recruit specialized expertise that could be useful for state purposes. Given the thinness of our sources for Philip’s reign, this claim rests as much on inference as it does on evidence. But there seems good reason to infer that Philip employed Greek expertise and that it was important to his success. The Liverpool historian, John K. Davies, has shown that in the Hellenistic period Macedonian dynasts borrowed extensively from fourth century Athenian fiscal institutions, especially in the area of taxation. This is especially clear in Egypt, where the documentary record is exceptionally rich (thanks to a climate that preserves scraps of papyrus). I suggest that the Macedonian adaptation of useful Greek expertise began earlier. Philip, who anticipated the practices and methods of his royal Macedonian successors in so many areas, was also a leader in the essential domain of opportunistic emulation. As we will see, however, in this domain Philip was himself anticipated by Perdiccas III, his royal predecessor.28

Some of the skilled experts recruited by Philip were talented Macedonians, but others were Greek. The availability of Greek expertise is not a sufficient explanation for the rise of Macedon or the political fall of Greece. As noted above, there were in the fourth century any number of states at the margins of the Greek world, ruled by aggressive “opportunists” who were eager and able employers of Greek expertise. In the end, of course, it was Macedon alone that posed an existential threat to the independence of the great poleis of the Greek world. Although the ready availability of Greek expertise cannot be sufficient to explain Philip’s success, it is entirely plausible to suppose that it was a necessary condition for it. Pushing the argument one step further, the availability of Greek expertise and a recognition of how to use it to advantage may be regarded not only as the key similarity between Philip and the other fourth century opportunists, but also as the key differentiator between imperial Macedon in the fourth century BCE and imperial Persia in the fifth.

Unlike Xerxes, who took on an alliance of Greek states at the head of military forces (at least insofar as the land army is concerned) organized and armed in the tradition of multiethnic Persian armies, Philip led a state that was, in various ways, Greek-like in its financial and military organization. When Greek armed forces confronted Macedonians in the mid-fourth century, they had none of the advantages in arms, armor, unit cohesion, training, maneuver, or morale that their ancestors had enjoyed relative to the armies of Darius and Xerxes in the fifth century. In a meaningful sense, when they faced Philip’s Macedonians, Greek soldiers were confronted with more experienced, better-armed, better-trained, and better-led versions of themselves.

I suggest that the two key areas in which Philip’s Macedon benefited from Greek expertise were financial administration and military organization and technology. But those specific areas were developed against a general background of Greeks in Macedonian service and the related phenomenon of elite Macedonian uptake of Greek culture. There is no doubt that Greek language, literature, art, and architecture were increasingly incorporated into elite Macedonian society during Philip’s reign. Elite Macedonians in the king’s court spoke Greek and were at home in the greater Greek world. While we know regrettably little about Philip’s civil administration, we do know that he employed Greeks as ambassadors (e.g., Python of Byzantion) and at least one Greek secretary: the ferociously competent Eumenes, a citizen of Kardia (i665), a small (size 2) but important (fame rank 3) polis on the northern shore of the Thracian Chersonese. Eumenes’ role in Philip’s administration is unknown, but under Alexander he became a principal secretary. After Alexander’s death Eumenes became a first-tier military commander in an age otherwise dominated by ethnically Macedonian warlords and soldiers.29

Perhaps most telling is Philip’s selection of Aristotle as tutor to his son, and presumptive heir. Aristotle, the son of a Greek physician who had attended Philip’s father, Amyntas III, was born in 384 BCE in Stageira (i613), then a prominent (size 4, fame 3) polis on the northeast coast of the Chalkidike Peninsula. Stageira was probably destroyed by Philip, in or around 348 when the Chalkidike was absorbed into the Macedonian empire, although the city may later have been refounded by him. Since about 366 BCE Aristotle had lived in Athens, as a member of Plato’s Academy. He left Athens after Plato’s death in 347. After a few years in Atarneus on the northwestern coast of Anatolia, as the guest of the local dynast/Persian governor Hermias, and then in nearby Mytiline on Lesbos, Aristotle was invited by Philip to Macedon to be Alexander’s tutor. Plutarch mentions instruction in Homeric poetry, but he also supposed that Aristotle offered his pupil political counsel.

The canonical list of Aristotle’s writings includes two lost treatises that were said to have been specifically written for Alexander, one “on behalf of colonists” and another “on kingship.” I have suggested elsewhere that the treatise on behalf of colonists should be understood in light of Aristotle’s development in book 7 of the Politics of a design for a “best practically achievable” polis. The lost treatise may have specified the sort of men Aristotle believed should be recruited for at least one of the new colonial foundations that he knew Philip and Alexander were planning. While Philip’s aims in hiring Aristotle as a tutor were certainly very far from Dion of Syracuse’s specious plan for having Plato transform the tyrant Dionysius II into a philosopher-king (ch. 9), Philip must have believed that immersion in aspects of Greek rational thought, including Greek political theory, would be of value to his heir (see further, below). Alexander himself presumably agreed on the value; in any event when he set off to conquer Asia, he brought with him Aristotle’s nephew, the historian Callisthenes, who had been born in Olynthos before its sack by Philip, along with other Greek experts in various aspects of science and administration.30

We may readily imagine that Philip recruited useful Greek experts both from free Greeks willing to be paid for their services, like Aristotle, and from enslaved Greek populations; Callisthenes may not have been the only talented Greek from Olynthos in Philip’s employ. There was, in any event, no lack of accomplished Greeks eager to bring themselves to Philip’s attention. Our fragmentary literary record includes genuine letters addressed to Philip by the Athenian orator Isocrates and by the Athenian philosopher Speusippos, as well as spurious letters to Alexander by Aristotle. At any given time, there would be a number of Greeks resident in the court; Speusippos’ letter implies, for example, that the historian and rhetorician, Theopompus, had made himself unpopular at Philip’s court.31 Philip had, as it were, a number of Greek resumes in hand from which he could pick and choose if and when he sought to recruit new talent. Among the Greeks he would have been particularly eager to recruit were individuals with deep experience in taxation and state finance, and in the related areas of mining, coinage, and minting. As we have seen (ch. 9) there is good reason to think that such individuals existed at Athens (and probably in other major poleis) and that the employment of experts by the Athenian state was a key element in sustaining Athens’ economy and influence in the fourth century.32

Philip was certainly well aware of the power of money. He was as famous in the Greek world for his clever use of money for diplomatic purposes as he was for his military innovations and victories. He was believed to have used his money freely to bring individuals and communities over to his side and was said to have quipped that there was no citadel to which one could not “send up a little donkey laden with gold” (Cicero ad Atticum 1.16.12). Although according to the historian Theopompus, Philip was a poor manager of state funds, this is contradicted by the evidence of his accomplishments and is probably the result of a polemical tradition conjoined with ignorance of how late-classical-era state finances actually worked.33 There is some reason to believe that the Macedonian state was, in the age of Philip, able to raise money through the mechanism of sovereign debt. The Macedonian treasury was thought to be in the red when Alexander took over as king, and Alexander was said to have borrowed heavily before embarking for Asia. If these reports have a basis in truth, they would account for Philip’s reputation as a bad manager among historians who failed to grasp the value of deficit financing. The same reports likewise point to the sophistication of Macedonian state finances.34

While Philip probably made especially good use of Greek experts, he was not the first Macedonian king to recognize that Macedon needed the kind of fiscal expertise that the Greek world could readily supply. We get a hint of the use of Athenian financial experts by a Macedonian king shortly before the reign of Philip from a late fourth century text wrongly attributed to Aristotle:

Callistratus, when in Macedonia, caused the harbor-dues, which were usually sold for twenty talents, to produce twice as much. For noticing that only the wealthier men [among the Macedonians] were accustomed to buy them because the sureties for the twenty talents were obliged to show [provide collateral] talent for talent, he issued a proclamation that anyone might buy the dues on furnishing securities for one-third of the amount, or as much more as could be procured in each case.

—Pseudo-Aristotle, Economics 2.1350a, trans. Armstrong (Loeb) adapted

Callistratus of the Athenian deme of Aphidna was a prominent politician who was in exile from Athens in the mid-360s. He was apparently employed as a sort of financial consultant by Perdiccas III, Philip’s immediate predeceessor, and was set to work on the problem of how to increase royal revenues. Callistratus’ innovation, allowing tax farmers to leverage their collateral, evidently broke the monopoly of a few extremely wealthy Macedonians. Once the tax auction was opened to men outside the superwealthy few able to put up twenty talents of collateral, the resulting competition drove up the bidding for the right to farm the relevant taxes to what we may guess was closer to its market price (i.e., just below the amount that could prospectively be realized by the tax farmer).35

Assuming that the story is true, it is a vivid example of opening access in ways that benefited the state—i.e., the king. The opening of access was done in a carefully controlled and limited way that appears calculated to expand the king’s revenues without upsetting his coalition: The very rich now could participate in an institution formerly monopolized by the super-rich. It is tempting (albeit entirely speculative) to link the passage in the Economics concerning Callistratus to Philip’s success in buying off the Illyrian tribes upon the death of Perdiccas III. A recent increase in the revenues from farming the export taxes could have left enough in the state treasury to give Philip, as incoming king, the means to purchase the time he needed in order to recruit and drill his first substantial army—and thus to begin the process that led to the rise of Greater Macedonia.

As we have seen, Macedon became a major gold- and silver-minting state after Philip’s takeover of the Pangaion mines in 356. The production and distribution of coinage—including the mining and refining of precious metals, minting of high quality (standard weight, high purity, iconographically distinctive) coins in large quantities, and circulating them through northern Aegean markets—required specialized knowledge at each stage. When recruiting experts to operate his mining and minting operations, Philip could have looked to Athens, the state that had, since the mid-fifth century, been the leading silver-coin producer of the Mediterranean. Athens, like Macedon, controlled rich silver mines. The fourth century was a period of innovation in Athenian practices of mining and refining silver ores. In the middle decades of the century the production of the Laurion mines increased substantially, a result both of new technology and legislation that encouraged mineral exploration. The Athenian mint produced great numbers of high quality coins, which circulated at a premium in Aegean markets (ch. 9). As we have seen, Philip adopted the tetradrachm form (although at a different weight standard) as a standard large-denomination coin. Although we lack direct evidence that Philip brought in Greek experts in mining, processing ores, and minting, it is altogether likely that he did, perhaps, as at Athens, acquiring experienced slaves for some of the work.36

Along with state finance and resource management, the military is the most obvious area in which Philip’s reforms catapulted Macedon to preeminence in the mid-fourth century. Here, Philip’s innovations not only resemble, but ultimately transcend, the state of the art in the leading Greek poleis of the era. And once again, there is reason to think that Philip self-consciously and selectively employed Greek expertise in achieving his own ends. As his revenues increased, Philip augmented his Macedonian army with Greek mercenaries, but, unlike the armies of the Sicilian tyrants, there is no reason to believe that Macedonian forces were ever predominantly mercenary, nor did Philip hire Greek mercenary generals to command his armies. The most prominent military commanders who fought for Philip were native Macedonians. Yet, as suggested above, the principles on which Philip’s military was organized—heavy infantry, in massed ranks, supported by cavalry and other arms—was adapted from techniques developed in fourth century Greece, and especially Thebes, where Philip had spent several years as a privileged hostage.

Philip’s ability to build on and ultimately to transcend Greek military practices is demonstrated by the development of a new offensive infantry weapon: the sarissa. The standard heavy infantry weapon of the Greek world had long been the thrusting spear: about 8 feet (2.4 m) long, with wood shaft, iron point and butt spike, weighing about 2.2 lbs (1 kg). The Greek spear was wielded in the hoplite’s right hand; his left hand and arm carried a heavy round shield. Under Philip, the Macedonian infantry began using a much longer and heavier thrusting spear, 15 to 18 feet (4.6–5.5 m) long, weighing about 12–14.5 lb (5.5–6.5 kg), and wielded with both hands. A light shield that could be slung over one shoulder replaced the heavy hoplite shield, leaving both hands free to manage the heavy sarissa. The sarissa was at some point, perhaps as early as the reign of Philip, adopted by Macedonian cavalrymen. As shown by the famous Alexander mosaic, the Macedonian cavarlyman held his long pike low over his horse’s withers, employing an underhand thrust that used the horse’s forward momentum, rather than the rider’s strength, to deliver the blow.

The sarissa reform involved a rethinking of long-canonical approaches to warfare. Far from a simple incremental improvement (“long spear good, longer spear better”), incorporating the sarissa into military operations involved fundamental changes in armor, shield, battlefield formation, and training methods, for infantry and cavalry alike. The idea of a long thrusting spear may have been borrowed from the equipment of light-armed Thracian peltasts.37 Yet the new approach was based solidly on the fundamentals of Greek land warfare as they had been modified in the course of the later fifth and fourth centuries: a deep and maneuverable phalanx of trained and reliable heavy infantrymen, each armed with a thrusting spear and shield, closely supported by smaller numbers of trained and reliable light arms and cavalry.

While the inventor of the sarissa is not preserved in the ancient tradition, we may imagine the sarissa reform as the product of a self-conscious project of military innovation driven by Philip and carried out by experts in arms, armor, and training. Given that the sarissa reform was a direct development of the contemporary Greek approach to warfare—as opposed to, for example, being based on masses of bowmen and cavalry supported by light infantry (as in fifth century Persia), or mounted archers, backed up by warriors armed with long swords and battle axes (as in Scythia)—it is reasonable to suppose that Philip employed Greek military experts in designing and implementing the reforms.38

By the 340s Philip was able to deploy a small navy of triremes. The Macedonian navy under Philip remained too small to challenge even a modest, 20-ship Athenian naval squadron, but it was sufficient to capture an Athenian grain fleet at the Bosphorus in 340. Since there was no Macedonian navy before Philip, he was required to build from scratch. Thus, there is circumstantial reason to suppose that Philip enlisted expert advice in ship construction and naval operations. The most obvious source of that advice would be from within the Greek world, although the Phoenicians and Carthaginians were also highly experienced in trireme construction and operations.39

We lack direct evidence to show that Philip hired Greek experts to restructure the Macedonian infantry and cavalry, or to build the Macedonian navy. We are on firmer footing with siegecraft. Philip clearly saw, from the very beginning, that having an effective siege train was essential to his plans: The successful siege of Amphipolis in 357 was the essential first step in the expansion of Greater Macedonia. Philip was not always successful in taking walled cities. In 340, as we have seen, he failed in his assaults of Perinthus and Byzantion (both size 5). But Philip did successfully take a number of Greek cities by storm, including Potidaia (size 2) and Methone (size 3). By his sieges of Amphipolis and Olynthos, he demonstrated that the Macedonian forces were sufficiently disciplined and determined to take very large (size 5) and well-fortified Greek cities.

Part of Philip’s success in siegecraft, but also in open-field battle, can be attributed to technological and operational innovations in artillery. Philip certainly made use of the nontorsion (crossbow-type) catapults that were probably invented in Syracuse at the beginning of the fourth century (ch. 9). It is, moreover, very likely that the torsion (hair- or sinew-spring-type) catapult was invented, around mid-century, by engineers in Philip’s pay. Torsion springs allowed for a major advance in the power of ancient artillery, and pointed to the potential for further advances. Torsion catapults proved to be a big factor in Alexander the Great’s campaigns in Asia. Increasingly tall and massive, yet mobile, siege towers were a related development. Siege towers allowed artillery to be used to maximum advantage, and enabled soldiers to gain access to circuit walls without resorting to flimsy ladders.

Philip is known to have employed several Greek designers of siege machinery. Like Xenophon and Aeneas the Tactician earlier in the fourth century (ch. 9), at least three of Philip’s poliorcetic experts wrote technical manuals. Polyidus, a Thessalian, the author of On Machines, was with Philip at the siege of Byzantion in 340, where he reportedly devised a huge mobile siege tower that was (somewhat prematurely) dubbed the “city-taker” (helepolis). At the siege of Perinthus, in 340, one Macedonian siege tower is reported to have reached a height of 37 meters. Polyidus had at least two Greek students who were also associated with Philip: Charias and Diades, another Thessalian. Like their teacher, each wrote a treatise on siege machines and both of these men accompanied Alexander to Asia.40

In addition to the marquee developments in artillery and siege towers, Philip’s siege engineers may be responsible for more subtle innovations: Not only are the catapult javelin heads, from bolts shot from Macedonian catapults and found in the ruins of Olynthos, heavier than earlier javelin heads, but Macedonian arrow heads and sling bullets are somewhat heavier than those used by the Olynthians. It is possible that Macedonian siege troops were using projectiles specifically designed for siege warfare.

PHILIP AND ALEXANDER BETWEEN ARISTOTLE AND HOBBES

In sum, one reason that Macedon under Philip succeeded in conquering the mainland Greek city-states, whereas Persia under Darius and Xerxes had failed, was because Macedon took on some, but only some, of the characteristics of a Greek superpolis. Macedon was like Athens and Syracuse in making effective use of experts and seizing a first-mover advantage from institutional and technical innovations. Even at the level of political institutions and culture, Philip’s Macedon was in certain ways more like a polis than was the Persia of Xerxes or Darius. Of course Macedon remained very unlike any great polis in that it was a monarchy, ruled by a king who could keep his own counsel, make his own policy, and did not need to worry about challenges to his legitimacy—at least so long as he was militarily successful.

As subjects of the king, Macedonians were never citizens of Macedon in the strong political sense that Athenians or Spartans were citizens of their respective states. Yet, like the citizens of a leading Greek polis, many Macedonians must actively have supported the regime at least in part because they saw that doing so was in their own interest, as rational people, capable of cost–benefit reasoning, and concerned (although not uniquely) with maximizing their own utility. While power played a part, Macedonians (unlike, say, the helots of Sparta) were not merely coerced into obedience. Nor did they obey only because they accepted a state ideology claiming for the king a godlike status. The Macedonians in Philip’s and Alexander’s armies expected to do better for themselves and their families than their ancestors in Upper Macedonia could ever have hoped to do. Alexander was not exaggerating wildly when he (reportedly) dressed down restive Macedonian troops by reminding them where they had come from and what they had gained:

Philip took you over when you were helpless vagabonds, mostly clothed in skins, feeding a few animals on the mountains and engaged in their defense in unsuccessful fighting with Illyrians, Triballians, and the neighboring Thracians. He gave you cloaks to wear instead of skins; he brought you down from the mountains to the plains; he made you a match in battle for the barbarians on your borders…. He made you city dwellers and established the order that comes from good laws and customs. It was due to him that you became masters and not slaves and subjects…. He annexed the greater part of Thrace to Macedonia and, by capturing the best placed positions by the sea, he opened up the country to trade.

—Arrian, Anabasis 7.9.2–3, trans. Brunt (Loeb) adapted41

Macedonians fought, not only for king and country, but also for themselves.

Like Cleisthenes of Athens, Philip was a sociopolitical innovator in that he created a vastly expanded coalition that included tens of thousands of ordinary (non-elite) men. In a move that is in some ways analogous to the radical expansion of the Athenian navy in the era of the Persian wars, Philip’s military reforms incentivized a great many more individuals to undertake service in the armed forces and enabled them to see themselves as primary stakeholders in the outcomes of state-directed military operations.

A rational commitment to advancing a community’s common interest in welfare and security, well aligned with the self-interest of many members of that community, had undergirded the reforms of Lycurgus of Sparta and of Solon, Cleisthenes, and Themistocles of Athens. That alignment of collective and individual interests was made explicit in the speeches put into Pericles’ mouth by Thucydides. It was the key to the rise of Thebes in the age of Epaminondas, to the rebuilding of Athens after the Peloponnesian War, and to the rise of the Greek federal leagues. The failure to align collective and individual interests at a scale beyond that of the city-state ultimately doomed the various imperial projects of Athens, Sparta, Syracuse, and Thebes. A similar failure led the poleis of Sicily into a cycle of tyranny and economic downturn in the mid-fourth century. Timoleon revived the Sicilian economy by aligning the interests of many Greeks around a common project of resisting Carthaginian expansionism and ending an era of warlord exploitation.