Directing for the first time is a lonely and exposed experience. For other people’s experiences in every aspect of making contemporary documentary, go to The D-Word website at www.d-word.com and search their voluminous archives for your own needs and interests. It is a wonderful resource, and a great place to go online to seek specialized advice.

Normally you develop relationships of trust during the research period, but sometimes you will shoot a particular scene or topic with someone you have just encountered. You will have to convince them that something about their lives is valuable for other people to see or know about. You can for instance film an old man feeding his dog, and talking to it, because he senses you know it’s a special part of a special life. A taxi driver will happily chat to the camera while cruising for a fare because that is his daily reality and it pleases him to share it. You may even discreetly film a woman relaxing in her morning bath because it was in this very bath that she took the momentous decision to visit Egypt.

People will let you and your camera explore their lives whenever they sense that you and your crew personally accept, like, and value them.

Your success at making documentaries often depends on what took place before the camera was ever switched on. For this reason I have always avoided topics or participants for which I feel little interest or empathy. Not always, though. I once embarked with very mixed feelings on a BBC film The Battle of Cable Street (GB, 1969, Figure 13-1) in which the central figure was the renegade aristocrat Sir Oswald Mosley, leader of the 1930s British Union of Fascists. I was shocked that while I grew up, my parents and their generation had said not a word about fascism existing in Britain. My researcher Jane Oliver and I set about finding people who had taken part in the decisive anti-Semitic street confrontation, in particular those among Mosley’s followers. They turned out to be shockingly ordinary; no horns or cloven feet to be seen. They wanted to present their case, which even made sense in a specious way. Jane and I meanwhile played the part of innocent youngsters learning history from its protagonists. In the end I interviewed Mosley himself. His reputation was that of an urbane, upper-crust swaggerer with an egomaniacal sense of importance about everything connected with himself. I felt apprehensive—less over his followers’ reputation for violence, or by revulsion for their values, than from fear of his reputation for squashing interviewers. So, instead of trying to trick or expose him, I simply encouraged him to explain the events for which his published accounts seemed farthest from reality.

During the lengthy editing period afterwards, the editor and I grew fascinated and repelled. To relay Mosley’s version of the 1936 events, yet show its delusional nature, we juxtaposed his account with those of other witnesses and participants. Metaphorically speaking, he hanged himself on the rope we gave him. The film pleased the Left, which opposed the freedom Mosley had been given by the police to organize racial hatred, and it pleased Mosley, who had expected to have his account distorted.

People often ask, “How do you get people to look so natural in documentaries?” Of course, you want to shake your head and imply long years spent learning professional secrets. Actually, this is much easier to achieve than, say, a satisfactory dramatic structure, but it still takes some basic directorial skills. The key lies in the way you brief your participants, as we shall see.

Interviewing is a way to give direction to a documentary, and gripping films by Errol Morris, Michael Apted, or Werner Herzog sometimes contain little else. In an oral history piece, little other than the grizzled survivors may exist, so talking heads may be all you can really show. Most directors, intent on sparing the audience from the hypnotic intensity of being talked at for long periods, take pains to show people active in their own settings, doing what they normally do. The audience prefers, I think, to judge character and motivation from what people do, rather than from what they say. Film can capture behavior beautifully, so documentary directors try to make sure that participants have familiar things to do, things that set them at ease.

So you decide to shoot your subject in three ways: relaxing with his family at home, collaborating with a fractious employee at work, and playing pool with cronies in a neighborhood bar. These situations won’t get beyond stereotype unless you can make them yield something unusual and striking. There is also a slight hitch: your subject feels most normal when nobody is watching him. Once he’s under scrutiny by your camera, his sense of self goes to pieces. This happened once to me. Filming in a glass-door factory, we turned our camera on a lady who had spent years passing frames through a machine. To her intense embarrassment, the frames began to jam or miss the jet of rubber sealer solution. It happened because she was now thinking about her actions and watching herself do them, instead of just doing them automatically. Feeling she must “act,” she lost automatic harmony with her machine, and all I could do was reassure her that this sometimes happens. We simply waited until she managed a few rounds in her old rhythm.

Make sure your participants have familiar tasks to do, even while they talk to your camera. For every action sequence, have some suggestions lined up in case you sense self-consciousness. I should have asked the lady in the factory to mentally count backward in sevens, or to discuss her shift with a colleague, to help move her mind away from the disturbing idea that she was being filmed.

Interviewing is a highly productive skill, and Chapter 31: Conducting and Shooting Interviews in Book II is devoted to the subject. For this, your early work, here are some commonsense reminders:

Preparation

● Know what you want to explore or find out.

● Make a list of questions on an index card.

Before you roll camera

● Let your interviewee know in general what specially interests you.

● Try not to use your question list since working from a list will seem formal.

● Instead, keep it handy on your knee in case your mind goes blank.

Beginning the interview

● Stay relaxed and natural, so tension in you does not affect your interviewee.

● Maintain supportive eye contact throughout.

● React and interact facially but not vocally (see “Avoiding Voice Overlaps” below).

● Using stimulating questions, evoke answers on everything you want explored.

Ending

● Glance at your question list to ensure you overlooked nothing important.

● Before calling “Cut,” ask interviewee if there is anything he/she wants to add.

If you mean to edit out your questions, it will be important that your voices never overlap. Each new answer from the interviewee must have a clean start with no voice overlaps, and no beginning that depends on your question. You can try asking interviewees to incorporate your question’s information in their answer, but they nearly always forget.

If, for instance, you ask “Tell me about your first job” you might get an answer that starts, “Well, it was in a school bus company, and I had to…” Without your question, this is incomprehensible. So you ask him to start again, suggesting he begin with, “My first job was…” As the interviewer you must listen for comprehensive, clean starts to each answer, and to interrupt and restart the interviewee as necessary. It’s also your job not to trample on their outgoing words, since this too is an overlap.

Very important—as the interviewer, do not be afraid of silences. Stay with each issue until you are certain the interviewee has said all she is willing to say. If you suspect there’s more to come, wait. You can sometimes prompt by saying “And…?” Using digital media means that waiting costs nothing, and you’re going to edit the material anyway. A pause is not a failure—it’s being considerate, and often by waiting you get gold.

It is good manners and good policy to ask at the end, “Did we cover everything you wanted to say?” This signifies openness and an attitude of shared control. It also leaves on record that you gave the interviewee full opportunity to supplement or modify all that went before.

Organizations, especially those operating in extreme situations, may be more paranoid than individuals. At any time they may want you to explain in writing why you are filming this topic or that scene, or say they “must see your script.” Keep any explanations general, simple, and uncontroversial, especially written ones. You should be consistent (because participants compare notes) but not so specific that you box yourself into a corner.

Day-to-day direction while shooting should begin from a comprehensive printed schedule with timely updates in cases of change. Include travel directions and everyone’s cell phone number, in case vehicles get separated. Put everything in writing since shooting is no time to test people’s powers of recall.

Ideally you involve the crew in developing the film’s approach, but if you shoot for television you may get an assigned crew. If so, outline the intended filming for the day, and keep the crew abreast of developments—something I sometimes forgot when pressure mounted.

Be formal about the chain of responsibility at first, and relax the traditional structure only when things are running well. If instead you start informally then find you must tighten up, you will meet with great resentment.

Once the crew assembles at the location, privately reiterate the immediate goals. You might for instance want a store to look shadowy and fusty, or to emphasize a child’s view of the squalor in a trailer park. Confirm the first setup, so the crew can get the equipment ready. A clear working relationship with your director of photography (DP) will relieve you from deciding a myriad of details. Never forget that your main responsibility is toward participants and the authorial coherence of the film.

The transition to shooting should hide the excitement and tension you may feel and instead be a time of relaxed, professionally focused attention. You and your crew, incidentally, should all wear soft shoes that let you move noiselessly. Shooting should take place in as calm an atmosphere as possible, and the crew should convey warnings or questions to you by discreet whispers or through agreed hand signals. The sound recordist may hold up three fingers to indicate that only 3 minutes of memory remain, or the camera operator may make a throat-cutting gesture with eyebrows raised (meaning, “Shall I cut the camera?”).

Many situations—with the public or with participants—are potentially divisive, so only the director should give out information or make policy decisions. The crew preserves outward unity at all costs, and makes no comment that could undermine anyone’s authority or sow the seeds of discord. They should be scrupulous about keeping disagreements from the participants, whose concentration depends on a calm and professional atmosphere.

When student crews break down it is often because somebody considers himself more competent than the director. As difficulties arise, well-meaning but contradictory advice alights on the director, creating alarm and despondency among participants and crew alike.

Whenever the camera is on a tripod, make a habit of checking the cinematographer’s compositions before you shoot, because afterwards it will be too late. At the end of the shot, look through the viewfinder again to check the ending composition. Some camera operators may imply you don’t trust them because of this. Insist, since it is you who will be responsible, not them. After a while you’ll find checking is seldom necessary.

Each time you give the command “Roll camera,” allow a few seconds of equipment run-up time before saying the magic word “Action” to your participants. Today’s cameras reach speed almost instantaneously, but during action immediately following a startup the camera may have problems of color or picture instability, so wait a few seconds. Under “The Countdown to Shooting” in Chapter 29: Organization, Crew, and Procedures for the Larger Production is the more elaborate procedure you need when you start up separate camera and sound recorder in a “double system” recording.

Whether the camera is tripod-mounted, or handheld, position yourself just to its left so you can see what it sees, and also be close enough to whisper to the operator. Be ready to move quickly, should the camera wheel around.

To avoid distracting participants while shooting, each crew member makes no unnecessary movements, maintains a professionally neutral expression, and stays away from participants’ eyelines. Even when something funny happens, the crew tries to remain silent and expressionless. If instead you react like an audience, participants will quickly take their cue and henceforth try to entertain you.

Ahead of a shot, tell the operator brief y what you expect to happen and how you want it to look. Rather than micromanage, make your overall intention clear so that he or she can adapt to the unexpected. Once the camera is running, whisper any necessary further instructions into the camera operator’s ear, being careful that your voice does not spoil a recording. Give brief, concrete instructions: “Go to John in medium shot,” “Pull back to a wide shot of all three,” or “If he goes into the kitchen again, walk with him and follow what he does.” Often you must trust the operator’s judgment, or risk sowing confusion.

Whenever the camera is running you communicate with sound personnel using hand or facial signals. If the camera is handheld, the recordist already has much to do—adapting to the action, covering what the camera needs, and staying out of frame. She will shoot you meaningful glances now and then, growing noticeably agitated at the approach of a plane or the rumble of a refrigerator turning itself on in the next room. Wearing headphones, she won’t know what direction the interference is coming from.

Once, shooting a former policeman in a raucous London pub, an incredulous look stole over the recordist’s face as a drinker in the next bar lost his investment, followed by the clank of cleanup operations with a mop and bucket. The interviewee was still talking, having noticed nothing, but the recordist was peering around apprehensively. It took great self-control not to howl with laughter. In circumstances like this, the recordist normally draws a finger across his throat, and mimes whether to call “Cut!” What should you do?

You have many immediate decisions to make, and your head pounds from stress. You are supposed to be keenly aware of ongoing content and yet must resolve through glances and hand signals problems of sound, shadows, escaped pets, or other versions of the unexpected. At such times you are half-blind from sensory overload and can only stagger onward.

When you direct, you are fully involved all the time and tend to overlook mere bodily interruptions like hunger, cold, fatigue, and bathroom breaks. If you want a keen and happy crew, stick to 8-hour days, and build meals and breaks predictably into the schedule. On long shoots away from home, allow the crew time off to buy presents as peace offerings to their loved ones.

Nobody but the director can call “Cut!” unless you’ve agreed the right to do so beforehand. The camera operator, for instance, might abort the scene if some condition that only she can see makes it pointless to continue. An arbitrary halt, however, may damage a participant’s confidence, so it’s nearly always best to keep rolling. Sometimes a participant, unhappy with something said or done, may call “Cut!” and you then have no option but to comply. Do not however encourage participants to take over your role.

Warn participants that you have to shoot presence tracks. When the time comes, everyone stands in eerie silence for a couple of minutes. You are uncomfortably aware of your own breathing and all the little sounds in the room until the recordist calls “Cut!”

Record a minute or two of presence at each location and for each mike position. Called variously presence, buzz track, room tone, or ambience, this is background atmosphere inherent to the location. All locations, even those indoors, have their own characteristic presence, and you must shoot one per scene. Collecting some from every location and every mike setup ensures that the editor can always fill in spaces or make other track adjustments. For more information, see Chapter 10: Capturing Sound and Chapter 28: Advanced Location Sound.

Once you finish shooting with anyone, ask them straightaway to sign a personal release document. You won’t have legal problems unless people think you have tricked them, or you get involved with those who nurture the (not unknown) fantasy that you are going to make a lot of money selling their footage. Cast participants with this in mind! There are various approaches to getting clearance.

(a) Some documentarians carry a release statement in a notebook and each new participant signs under previous signatures. As door-to-door canvassers know, people sign more willingly when they see friends or neighbors have signed before them. A signature gives you the right to make public use of the material in return for a purely symbolic sum of money, such as $1. It does not however immunize you against legal action should you misuse the material or libel the signatory.

(b) Some documentarians get a verbal release by asking participants to say on camera that they are willing to be filmed and that their name and address is such-and-such. This certainly guards against claims later that they “didn’t know they were being filmed.” A verbal release does not however explicitly release you in all the ways that a lawyer would want, nor does it guard against people deciding later they don’t want to participate—thus rendering months of work void.

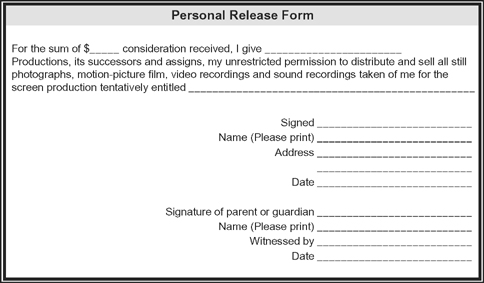

(c) A signature on the brief release version in Table 13-1 will suffice for your first productions, but any work for broadcasting will require a form whose pages of legalese send ordinary mortals pale with alarm. For full-length location and personal release forms, see this book’s website (www.directingthedocumentary.com).

Once you have shot the scene, and all necessary materials are “in the can,” it is time to strike (dismantle) the set or otherwise move on (Figure 13-2). Be sure you shot presence track, then call “It’s a wrap!” Everyone starts their winding-up responsibilities:

● Lower the lights and roll up cables while any hot lighting fixtures cool off.

● Strike the set, collect clamps, stands, and boxes.

● Take the camera off its support, dismantle it, stow it in its protective travel boxes.

● Stow sound and lighting equipment in their own travel boxes.

● Replace furniture and household goods exactly as you found them.

● Confirm the schedule for the next day’s shooting.

● Check the location is undamaged and everything is clean and tidy.

● Thank each participant and each person in the unit for a good day’s work.

Table 13-1 Short Personal Release Form suitable for student productions. See the website (www.directingthedocumentary.com) for a professional-level equivalent—its legalese can intimidate those contributing to modest productions

FIGURE 13-2

Fully equipped documentary crew moving on to the next location. (Photo Camille Zurcher/Colectivo Nomada.)

When participants are out of earshot, encourage the crew to freely discuss the production, because you often learn things from them. Don’t be shocked if they lack a holistic grasp. The cause is simple: fully engaged crew members each have particular areas to monitor.

Camera operator watches for lighting, focus, compositions, framing, movements, and whether the mike is edging into shot.

Sound recordist listens for unwanted reverb or echo; ambient noise; mike handling sounds; sound consistency from shot to shot; voice quality; and the relativity of sound levels.

Director monitors the scene for content, subtext, and emotional intensity. What does this add up to, so far? What meanings are taking shape under the surface as subtext? Where is the scene going? Is this what I expected? Does it deliver what I hoped, or is this something new?

Neither camera nor sound personnel can possibly have a balanced awareness of film content, so don’t expect it of them. They will, however, have noticed all sorts of things that have escaped you.

Crewmembers at work monitor a restricted area of quality, so you should periodically reconnect them to the project as a conceptual entity. Not everyone will appreciate your efforts. In “the industry” there is sometimes a veiled hostility by which “tekkies” separate themselves from “arty types” and vice versa. Your crew may never have had their opinions sought outside their own area of expertise. From being treated like factory hands they may not have considered filmmaking from a directing standpoint, so be ready to meet hesitant or even hostile reactions to your efforts. Persist. If you want a crew whose eyes, ears, and minds extend your own, share your thinking with them.

Acknowledge crew feedback gratefully—even when it’s embarrassingly off target. Make mental adjustment for any skewed valuations and be diplomatic with advice you can’t use. Above all, encourage involvement, and don’t retreat from communicating.

If you haven’t yet done AP-2 Making a Floor Plan, this is a good time to try it. You might also use DP-8 Dramatic Form to bring out any latent dramatic elements in your subject. This would be a good time to start interviewing with SP-10 Interview, Basic, Camera on Tripod.