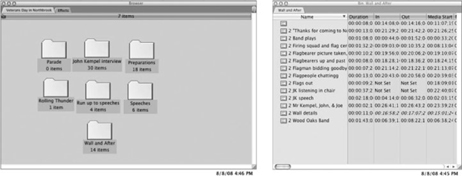

FIGURE 14-1

What the Avid ® user sees.

Postproduction is the extremely creative phase in documentary-making during which you transform the sound and picture dailies, along with any graphics, text, captions, photographs, or animation, into a stream of consciousness for consumption by an audience. Editing a documentary is normally a long, experimental procedure, and represents your second chance to direct. The major challenge usually lies in finding a strong, logical narrative structure. Some films have their temporal spine usefully predetermined because their subjects follow a well-defined process, such as rescuing miners after a mining accident, or a youthful oboe player taking an all-important music exam. Other, less process-oriented films—about researching traditional weaving processes, say, or climate changes resulting from coal-f red generating plants—may have no obvious, inbuilt time progression as a narrative backbone, and so you have to look for an alternative. Life can prove very random, and films you shoot about it can be very ad hoc. Several times I have finished shooting with no clear idea of how to assemble my film, because shooting turned out so unlike what I anticipated. Editing is then like making a collage from found objects. These, placed experimentally in juxtaposition, eventually suggest what film narrative is possible and desirable.

This part of the book describes tried and tested operations that will help you find the wood among the trees. Your film’s identity and purpose will assuredly emerge as you work on it—a truly fascinating experience.

Newcomers to editing usually do well, once they have mastered the editing software. Editing a documentary is similar no matter whether the film is long or short. Longer films require more complex structuring and of course a more extensive filing system.

Most operations described in this chapter are the small-unit editor’s responsibility.

Under the rubric of economics, the director often becomes the editor. By all means edit your own work in the early stages, but when you move on to longer and more complicated projects, a one-man band can be folly. Every film benefits from the independently questioning viewpoint of an editor, and this is not a challenge for control, but a collaboration in which the editor is consciously a proxy for the audience. Having no prior investment in research and shooting, editors can often see ideas and solutions that surprise the director, who is often depressed from a sense of failed intentions while shooting. One of my most fruitful working relationships as a director was with an editor whose politics were quite different, and even opposed to my own. We liked and respected each other, so the creative tension between us kept me in useful proxy dialogue with those in my audience skeptical of my political and social outlook.

Editing with nonlinear editing (NLE) software by Avid, Final Cut Pro, or Adobe Premiere is now ubiquitous and accessible. The early-established Avid system (Figure 14–1) is the front-runner in performance and user friendliness, but can prove costly in updates. It is the industry standard, so knowing it will be a large feather in your professional cap. Many documentarians however use Final Cut Pro (Figure 14–2) or Adobe Premiere Pro because of their lower cost (Figure 14–3).

If you have much speech in your film, transcribing your participants’ every word will be invaluable to grasping all that is there. It sounds tedious, but is never as laborious or unrewarding as people fear: it has its own fascinations, saves work later, and ensures you miss few opportunities. If your film involves court testimony, the actual words people use will be paramount, and transcribing them unavoidable. Chapter 32: From Transcript to Assembly describes how to make a whole first assembly from edited transcripts.

FIGURE 14-2

The main window of Final Cut Pro®.

Instead of verbatim transcripts, you can log stretches of discussion or interview by topic categories. You summarize topics covered during each scene or interview, and log these by approximate timecode in- and out-points. That will give quick access to any given subject, but you will then need to make decisions by ear during editing, which is hard labor of a different stripe.

Using transcripts too literally has some dangers: words that look significant on paper sometimes prove anemic on the screen, and vice versa. The act of transcribing always invites a degree of literary organization—the more so if the original scene took place impulsively and chaotically. When voices overlap, or people use special nuances or body language, transcripts mislead by interpreting reality. Also, how somebody says something can be more telling than what is said, since we qualify what we say with our faces and bodies. A transcription never conveys all the subtext.

Videomaker (www.videomaker.com) has excellent articles and reviews on everything for digital production and postproduction, and through its website one can find very helpful filmmaking videos. Try Google “Groups” to locate users of your particular software; often this yields answers at dead of night when you’re ready to tear your hair out. Likewise, entering a problem or procedure in YouTube.com often brings up a medley of instructional or demonstration videos.

The work of the editor and editing crew includes the following:

● Digitizing from the camera storage medium to the computer hard drives.

● Synchronizing sound with action (necessary if sound acquisition was via a separate “double system” recording).

● Screening dailies for the director and producer’s choices and comments.

● Logging material in preparation for editing.

● Making an editing script, unless the director and/or writer makes one.

Making a first assembly.

● Evolving the first assembly to a rough cut.

● Evolving the rough cut to a fine cut.

● Supervising, with the director, the recording of narration (if there is one).

● Locking picture in preparation for any narration and music recording.

● Preparing for and supervising, with the director, any original music recording.

● Laying sound tracks (finding, recording, and laying components of multi-track sound such as atmospheres, backgrounds, and sync effects in preparation for the sound mix).

● Supervising, with the director, the sound engineer’s mix-down of these tracks into one smooth final track.

● Obtaining titles and graphics.

● Supervising color correction with the cinematographer.

● Finalizing postproduction and supervising the making of release copies, safety masters, etc.

On a large project, postproduction is handled by specialists, but on low-budget projects the editor wears several hats. Such intensive exposure to the bone and muscle of screen creation can quickly turn you into a first rate editor, especially if you become good at solving the structural and dramatic problems that documentaries always pose. Such experience is the finest preparation for directing them.

The first step will be to transfer all selected material to the editing computer’s hard drive. Check assiduously that your editing software can handle not only the camera format, but also those archive sources such as analogue video, photographic files, and scanned film of various formats. Older material will be in antiquated screen aspect ratios, and older editing software may need modification to handle a newer camera codec.

Watch out! Your workflow can easily get complicated and very expensive if you decide to integrate, for instance, NTSC (American standard video) at 30 frames per second (fps), with film scanned from 25 fps PAL (European) video, as well as stills in JPEG f le format and others in Windows BMP (bitmap) format. Add to this that your main footage is in 24p HD (24 frames per second progressive scan high definition) and that you would like the opportunity to distribute on Blu-Ray, and your workflow has now turned into a minefield. You will be courting disaster if you kick the can down the road and deal with problems as they arise.

The solution is to first research other people’s advice and experience thoroughly. For now, especially if you have little experience, treat yourself kindly by keeping your technological pathway simple. Follow whatever experienced users recommend. For more on this see Chapter 35: Editing Refinements and Structural Solutions.

It may be an advantage when editing HD material to edit in “lo res” (low resolution) since this permits much faster computer operations. Later, use the edit decision list (EDL) to re-digitize only the material used in the cut. The computer will then reassemble the edit at high resolution.

Your dailies will probably be shot by one camera and therefore in a common digital format. This should easily transfer into your NLE program without any file conversions. Material shot in other formats, or with other picture or sound codecs, may require transcoding before it will integrate with the bulk of your material. Organize the material by digital folders called bins, each containing a major sequence or classification of material (Figure 14-4). Logging the material by shots or sections helps you memorize all the materials available, and puts the material at your fingertips.

If you shot “double system” (shot sound with an additional and separate audio recorder) then you will have used a clapper or timecode marking system while shooting. This is mandatory in order to identify each sound segment. Then during postproduction you synchronize each shot with its appropriate track, putting each take in sync by lining up the crack of the clapper bar with the first picture frame in which it is visibly closed. Over long takes, keep a weather eye open for creeping sync (drifting out of sync).

During doublesystem recording, camera operators often leave the deck mike open, thus recording a scratch track, a back-up useful when shooting conditions left separately recorded sound materials chaotic and without announcements or clapper sync points.

FIGURE 14-4

FCP project bins and the shots in one of them.

We call the unique, time-related number assigned by the camera to each video frame timecode; it is the ID by which the editing program handles all that goes into compiling its edit decision list or EDL. Log each scene, important action, or event, so you can find it later. Keep descriptions brief— they only need remind you what to expect. For example,

| 01:00:00 | WS (wide shot) man at tall loom. |

| 01:00:30 | MS (medium shot) same man seen through weaving threads. |

| 01:00:49 | CS (close shot) man’s hands with shuttle. |

| 01:01:07 | MS as he works. Stops, rubs eyes. |

| 01:01:41 | His POV (point of view) of his hands & shuttle. |

| 01:02:09 | CS feet on treadles (MOS). |

The figures are hours: minutes: seconds. Timecode ends with a frame count, but in a content log you don’t need hair-splitting accuracy. The example explains standard shot abbreviations except the last. In Britain the expression for “shot without sound” is “mute,” but America still enshrines its German immigrant directors’ call of, “Mit out sound!”—abbreviated to MOS.

Logs, bins, and shot descriptions should help you locate material quickly, so it is good to design divisions, indexes, or color codes that assist the eye. The housekeeping you set up for a short production need not be as detailed as those for one longer, where the chance of being unable to find material becomes an employment hazard. Nothing is more humiliating than searching for a shot while your director, sponsor, or employer stares at their fingernails. Inadequate filing always exacts revenge because Murphy (of Murphy’s Law) loves to lurk in sloppy filing systems.

Viewings during the editing process are an important forum for the exchange of impressions, ideas, and postmortem realizations. The processes below may seem like overkill for a short documentary, but become vital for anything more complex.

Screenings include various people and have various purposes. At any viewing you will learn much from sitting at the back and watching viewers’ body language. It will prepare you for the thoughts, feelings, and observations soon to be articulated by your trial audiences.

Even when crewmembers have seen dailies piecemeal, they should also see the entire dailies at a sitting or two after shooting ends. Everyone should see their patterns, limitations, and mistakes— not just the successful material in the final edit. The editor might attend this viewing, but discussion is likely to be a crew-centered postmortem that is not relevant to editing.

When the crew sees dailies, there will be useful debates over the effectiveness, meaning, or importance of different aspects of the material. Be ready for crewmembers to be partisan over filming situations and particular participants, and to harbor specific feelings about participants’ credibility and motivations. Listen and don’t argue, since similar thoughts may well occur to your future audience.

Keep in mind that the crew are less objective than you are. Until they see a cut, they don’t see the film holistically from an audience perspective, but from the subjective immersion of their work. Not only have they developed feelings of relationship to the participants, they are deeply involved in their own discipline, and will often overestimate its positive or negative effects. That said, their insights do often include valuable revelations.

To find and agree on the general thrust of the material, you and your editor see all the dailies together. As you face the problems in the piece, your mind working overtime to find ways out, this is a stressful time, especially as you probably feel oppressed by failed goals. Maybe you see irritating mannerisms in one of the participants that you must cut around if he is not to appear shifty. Or, one of your two main characters is more interesting and articulate, and you must shift your original premise.

Listen to what your editor sees in the material, because a newcomer not involved with acquiring the material sees it with an objectivity and sense of possibility that a director simply cannot have.

View all the material again, scene by scene. Stop whenever necessary to thrash out each scene’s problems and possibilities.

During showings, the editor or an assistant keeps notes of the director’s choices, comments, and any special cutting requests. If you must write notes, make large, scribbled notes on many pages of paper, so that your eyes almost never leave the screen. If you look away, you will undoubtedly miss important moments and nuances. The sum of the dailies viewing is a dailies notebook full of the director’s and editor’s choices and observations, as well as many glancing impressions of the movie’s potential and deficiencies.

Note all emotional high points or unexpected outcomes, since these probably contain important clues whose meaning may not emerge until you work out later where they come from, and what they signify. Almost certainly they will be mainstays in the future film.

Note any unexpected moods or feelings. If you find yourself reacting with, “She seems unusually sincere here” or “I can’t believe that really happened,” then note it down. Afterwards one can easily doubt that your gut feelings really matter, and so you are apt to ignore and forget them. But seldom are these isolated personal reactions, since whatever triggered them lies embedded in the material, and will also strike first-time audiences. Later, when inspiration lags from over-familiarity, all your early perceptions will become useful navigation stars.

Choose segments and lay them as a first loose assembly along the program’s timeline (the horizontal line across the software screen that represents the advance of time, Figure 14-5). You will be able to lay the corresponding sound track opposite its picture, and to predetermine sound levels so you can hear a relatively layered and sophisticated track as you edit. Unlike film editing, in which the editor physically altered a workprint, a digital editing program stores versions as an Edit Decision List or EDL. This is a set of internally generated access instructions to the bank of shot materials. The pool of material itself remains pristine throughout editing, like a library consulted but never emptied. Date each new version, and when the draft is complete, make a newly dated copy as the basis for starting the next draft. This will leave a trail of versions to which you (or your biographer…) may revert at any time. If you prefer an earlier sequence, it is straightforward to copy it from the earlier version of the timeline and paste it wholesale into the new version.

Now the director changes hats. No longer are you the instigator of the material: instead, you and your editor are surrogates for the audience. Every time you view parts of the film, or the whole in its entirety, you must try to see it as if for the first time.

If your film has sufficient imagery, and you first assemble all the film’s usable visual and behavioral material, something rather exciting happens because you are starting from the strength of the cinema (imagery) rather than its weakness (talking heads). By choosing a likely time-structure and arranging the material in a loosely assembled flow, you are building a rough narrative out of behavior, action, imagery, and atmosphere. The more they lead your story, the more cinematic and memorable it will become.

At some point you will almost certainly need to draw on language, but you’ll use it to supplement your visually established structure. How you do this depends on how you approached directing the subject, what you were able to shoot, how you organize the editing, and ultimately what Storyteller role you decide to play in relation to your audience.

Building a film from transcripts, however, leads to one stuffed with wall-to-wall talking. For movies based on hosts, performers, and interviews, no other kind of film is possible, and this includes any historical film for which little imagery is available. Some people telling stories are simply fascinating, but if you conceptualize a film starting with words and ideas, it will always lead to illustrating them, which means taking the path of journalism, and privileging language over the visual. The difference is starkly apparent if you compare Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi (USA, 1982) with Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth (Davis Guggenheim, USA, 2006, Figure 14-6). Both deal with the rape of the environment, but while Reggio’s film is a visual tragedy of operatic proportions, Gore’s is a one-man performance piece, as passionate as any revivalist meeting, but afterwards utterly forgettable. Reggio’s film lives on in memory, Guggenheim’s does not.

Your whole filmmaking world, for the time being, exists within those dailies that you shot. So, purge yourself of prior knowledge and intentions, since the audience’s whole understanding and feeling must arise from the screen. Besides, nobody wants to hear your war stories about what you intended, or what you could have produced.

This is the process in which the computer pauses, sometimes for unimaginably long periods, to knit its brows over making new files for shots that combine elements in some way, such as titling, or optical effects like fades and dissolves. Have other things ready to do!

A gripping narrative feels charged with forward momentum because, one way or another, it promises a meaningful experience of some kind. Michael Angus and Murray Fredericks’ Salt (Australia, 2009, Figure 14-7) does it visually. It fills us with curiosity as a waterscape reflecting the sky slowly yields a tiny Figure riding a bike towards us through a vast salt lake only inches deep. Who is he? Where is he? Why does he return year after year to live in a tiny tent under the dome of the heavens and photograph the phenomena of nature? It proves to be an anguished spiritual quest and not just one of curiosity, and it leaves him on the mobile phone, struggling to explain his absences to his wife, angry that he leaves her with their family every summer.

If you managed to realize your directorial goals while shooting, structuring the assembly may be straightforward. More often, your intentions were frustrated by the unexpected, and now you must pick yourself up and make something of what you actually filmed. Editing is your chance to regain control.

Identifying a structure for your footage begins with deciding how it should handle time, since temporal progression is an all-important organizing feature in any narrative. To develop a structure for your film, try asking yourself:

● What makes the best overall story from your dailies?

● What different ways could you tell it?

● Whose story is it?

● In what order should you show cause and effect?

● What advantage lies in altering the natural or chronological sequence of events?

● Should you use parallel storytelling to run two narratives concurrently?

If you have plenty of action and visual sequences, put a rough assembly together of observational material alone, and then view it without stopping. Then ask yourself,

● What is the thrust of this material? Does it, for instance, tell a story, convey a mood, introduce a society, or set an epoch?

● What memorable interchanges or developments did I capture on-camera? This, of course, will probably take pride of place because it’s your strongest and most persuasive “evidence.”

● What period does my material span, and how well does the assembly convey this? (It’s often helpful to a narrative if its events are pressurized by happening in a set time period.)

● What would your film convey if it were a silent film? (This is the acid test by which to recognize whether your material can be made cinematic rather than literary, theatrical, or journalistic.)

● How many phases or chapters does the material fall into, and what characterizes each?

Once you have revised and considered your rough assembly of visual and behavioral material, you can ask:

● What verbal material, as yet unused, could I employ to bring further dimensions to the “silent film” assembly so far made?

● What new dimensions does the original action- and behaviorally based film acquire? (Make a new working hypothesis.)

● How little speech material do I need to shift the film farther toward something articulate?

Beginning from visual and behavioral evidence lets imagery suggest the story. By bringing a few words to your behavioral assembly, and perhaps by using voice-over rather than “talking heads,” you can portray characters who seem to be speaking from their interior lives rather than interacting conventionally with an interviewer.

If your film is a historical retrospective, or one that scans many people’s viewpoints, you will probably start by assembling interviews. Your best word-driven structure will likely develop during the intensive process of making a paper edit from transcripts (see Chapter 32: From Transcript to Assembly).

Whatever story structure you find affects the contract you must strike with your audience. Yes, your audience expects a contract — an indication in the film’s first moments of its premise, genre, and goals. This is your promise to keep up the dramatic tension that comes from having a good tale to tell. This, as we shall say in Chapter 17: Point of View and Storytelling, is part of your Ancient Mariner’s skill at detaining the Wedding Guest. You may signal the contract in the film’s title, spell it out in narration, imply it in the logic of the film’s opening minute or two in a prequel, or otherwise as a hook by something shown, said, or done at the outset. Leo Tolstoy in his tale of the unhappily married woman Anna Karenina does it famously by beginning with, “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” All good stories engage their audience, and your work must grab their attention right away since viewers can kill off your film with a single prod at the TV remote.

You’ll find longer film structural types with examples in Chapter 18: Dramatic Development, Time, and Story Structure. The examples and discussion there may further help you decide what limitations or potential lie in your dailies. Ways to analyze your film and find alternative structures appear in Chapter 35: Editing Refinements and Structural Solutions.

A story which is going somewhere, and which manifestly has a purpose, holds our attention from sequence to sequence if it is at all skillful, for dramatic tension is at the core of all effective storytelling. With each sequence you should aim to create a question in the audience’s mind—what will she do next? Will the check really be in the mail? Can the detachment hold out until the reserves arrive? Did he decide to stay or go?

FIGURE 14-8

Michael Apted’s classic Up series, a longitudinal study over decades that began in its subjects’ childhood.

An important element in any story is that somebody in it should learn, grow, or develop—however minimally or symbolically. This, called the story’s development, may take less obvious and even “negative” forms. In Grizzly Man, Treadwell’s love of bears prevents him from protecting himself, a failure that leads to his destruction by them. Treadwell is opposing the rules of the universe, as the filmmaker and philosopher Michael Roemer would say (see “Plot and the Rules of the Universe” in Chapter 18: Dramatic Development, Time, and Story Structure). Such heroes are the norm in tragedy: their development lies in the central character’s drive for a trial of strength and a showdown.

A problem for many documentaries is that human change is often too slow to happen within an affordable shooting schedule, so development has to be implied rather than shown. Other films become longitudinal studies and chronicle their subjects’ progress over years or decades. Michael Apted’s Up series (GB, 1964–present, Figure 14-8) takes a group who were seven-year-olds in the early 1960 s and revisits them every seven years, in each film intercutting their present most poignantly with their past, and showing the serpentine unfurling of destiny for each. Robb Moss’s The Same River Twice (USA, 2003, Figure 14-9) takes a film about his friends in the late 1970 s, who once rafted nude down the Colorado river together, and revisits five of them a quarter century later to see what they have done with their lives. How satisfying to see people exploring hopes, dreams, and betrayals over a such large chunk of their lives!

FIGURE 14-9

Where are they now? Robb Moss revisits companions of a youthful journey in The Same River Twice.

Longitudinal films are more feasible now filmmakers can own equipment of their own and start filming at the drop of a hat. Paradoxically, intermittent filming is easier for independents than for corporations—so often tied to industrial schedules and the need for immediate viewing figures.

● How will your film imply that someone has grown or changed, or has been defeated by fate?

● Who in your film needs to change, and who or what does change?

● Take advantage of literary, poetic, theatrical, musical, and other disciplines with parallel stories that can help you spot what is inherent in the story you are developing.

To tackle a large, diffuse subject like industry polluting the water table, you must often find an example, a microcosm that will imply the macrocosm. Back when the UK was joining the European Common Market, I worked on a BBC series whose intention was to introduce aspects of French life to the British TV audience. Since we could not even begin to show all the different regions, we soon decided to conf ne ourselves to the capital. “Faces of Paris” thus showed aspects of France and French culture by showing the lives of interesting Parisians. You look for the particular to represent the universal, yet how typical is any Parisian? Whoever you choose only demonstrates how triumphantly atypical all examples really are.

In the relentlessly specific medium of film, making abstract generalizations is problematic. Writers solved similar problems in previous centuries. John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (1678) is a journey of adventure, but it functions also as an allegory for the journey of the human spirit. The Maysles Brothers’ superb Salesman (USA, 1969, Figure 14-10) does something similar by showing that a share in the American dream comes at the price of humiliation and moral surrender. It achieves this by showing how every phase of door-to-door selling is driven by corporately dictated sales figures, something the Maysles Brothers had endured themselves when selling encyclopedias. Don’t imagine that today’s technology has simplified a storyteller’s apprenticeship. Your models for strong narratives lie in expertise developed over centuries in all the time arts. Understand how they solved particular narrative problems, and you won’t have to reinvent the wheel.

Fred Wiseman likes to use an observational camera and an allegorical “container” structure. That is, he films an institution and treats it as a complete and functioning microcosm of the larger society. The emergency room doors in Hospital (USA, 1970, Figure 14-11) admit the hurt, the wounded, the drug-overdosed, and the dying in a frightful vision of the violence, despair, and self-destruction stalking American urban society. Yet the same “institution as walled city” idea applied in the less obviously crisis-ridden High School (USA, 1968, Figure 14-12) seems diffuse and directionless. The relationship Wiseman wants us to notice between teachers and the taught is too low key, repetitive, and unremarkable to build much momentum or sense of development. I have a similar problem with Wiseman’s At Berkeley (USA, 2013), made nearly a half-century later. His non-interventional approach and lack of guiding narration leaves him with few tools to focus, develop, and intensify the vital issues. He would probably retort that it’s my job to work that out. And this is true.1

Whether you found a structure by using a visual, behavioral approach, or a verbal one through transcripts, you can now roughly assemble the useable material. Don’t agonize over the consequences of what you are doing. Leave everything long and expect repetition. You have two different accounts of how the dam broke? Slap both in, and decide which seems best onscreen.

Making the first assembly is the most exciting part of editing, because it is like a birth. Don’t worry at this stage about length or balance. You should see a whole assembly as soon as possible before doing detailed work on any sections. Only then can you make far-reaching resolutions about its future development. Of course, you will want to polish a favorite sequence, but fixing details is often a way to evade a confrontation with your film’s lack of overall identity and purpose.

FIGURE 14-11

The institution as window on urban violence, despair, and self-destruction in Hospital.

FIGURE 14-12

High School—no place to learn democracy. (Photo courtesy of Zipporah Films, Inc.)

To judge a first assembly, try to purge all foreknowledge from your mind so you can see with the eyes of a first-time viewer. This unobstructed, audience-like way of viewing is a hard discipline to maintain, but one utterly necessary every time you run your film. What always helps is to have anyone present for whom the movie is new. Sit behind them and absorb their body language for clues. Even if they never utter a word, the presence of a newcomer somehow gives you fresh eyes.

After viewing the first assembly, your material will start telling you where and how to cut. This signals a welcome and slightly mysterious change in your role from proactive to reactive. Formerly you had to expend energy to get anything done, and now the energy starts to surge from the film itself, and you must struggle to keep up.

As your creation comes to life, early viewings begin to reveal its nature, dramatic shape, and optimal length. Look to the content of your film for guidance on length. Spend any time sitting on a festival jury and you will know that most documentaries are at least 30–50% too long. The director is the worst judge of length, and a film’s natural span depends on the richness and significance of its content, as well as where an audience sees it. Audiences for television, cable, community cable, cinema, or YouTube all bring different expectations. Where does your project really belong? If your advisers can persuade you to recognize that your film has a 10-minute content, then you can get tough with that earnest 25-minute assembly and shape it for its most likely audience.

Where your film might be shown helps determine its length and structure:

● Classroom films are normally 10 to 20 minutes.

● Television uses 30-, 40- (in Europe), 60-, and 90-minute slots.

● Festivals, where reputations are made, love short films that say a lot: the shorter the better.

● Internet videos on YouTube, etc. have been limited to 10 minutes, but are getting longer.

As the Internet moves toward delivering full fidelity, longer and more substantial pieces will inevitably join the mercifully short ones. Nobody, however, will watch a longer film unless it exhibits the storytelling f air and craft sophistication that a general audience demands.

Immediately after this viewing, scribble a list of material making the most impact—you’re going to use this list later. Facing your film in its crudest form, you must now elicit your own dominant reactions. Flush them out by asking:

Exposition:

● How much setup information should I give, and how soon?

● Who should give it?

● Does the audience presently get too much or too little? (A sequence may fail if its context is inadequately explained.)

● Can some be delayed? (Too much exposition too early can deluge viewers in information about people and issues they have not yet learned to care about.)

● Is it too clumped? (Consider thinning or holding back expository material until it’s really needed. Make the audience work—they enjoy it.)

Characters and their point of view:

● Which participants held your attention, and which didn’t? (Some may be more congenial or just better on camera than others.)

● Who is the story really about?

● Whose point of view should we mainly share? (The main character’s? The director’s? That of a secondary character?)

Content and meaning:

● What kinds of metaphysical allusions could my material make?

● Could I make use of connotation and metaphor?

● Are my film’s values and beliefs emerging? (Use open rather than leading questions.)

Dramatic shape:

● Which parts of the film seem to work, which drag, and why? (This helps to assess whether the film’s development is even, and to spot impediments in the film’s momentum.)

● Was there a satisfying alternation of types of material? (Was similar material clumped indigestibly together? Where did you get effective contrasts and juxtapositions? Can you make more? Variety is as important to storytelling as to dining.)

● Does the film feel dramatically balanced? (That moving and exciting sequence in the film’s middle may be making all that follows seem anticlimactic.)

● Were there any forces in opposition, and did they come into confrontation?

● When does the story move, and when does it hang?

The human memory is a great editor because it discards whatever lacks meaning. From a screening, compare what left a strong impression against a full sequence list. What you “forgot” is failing to deliver for some reason. This does not mean it will never deliver, only that it’s not doing so yet. Common reasons for material to misfire:

● Two or more sequences are making the same point (Repetition does not advance an argument unless there is escalation, so make choices and ditch what’s redundant.)

● A climax is in the wrong place (If your stronger material peaks early, the remainder of the film becomes anticlimactic.)

● Tension builds then slackens (Plot your movie’s rising and falling emotional temperatures: if it inadvertently cools before an intended peak, the viewer’s response is seriously impaired. Sometimes transposing a couple of sequences can work wonders.)

● The film raises false expectations (A film, or part thereof, fails when you don’t deliver what the viewer has been led to expect.)

● Good material is somehow lost on the audience (We read into film according to the context. A misleading setup, or a failure to direct attention to the right places, can make material fall flat.)

● Multiple endings (Decide what your film is really about and kill your darlings.)

If this list resembles traditional dramatic analysis, you are right. Like a playwright watching a first performance, your lifelong diet of drama sensitizes you to your assembly’s faults and weaknesses. This is tricky ground because there are no objective measurements. All you can do is assess what you feel about your material’s dramatic effectiveness.

Where does the instinct for drama come from? Certainly we learn from all the entertainment we consume, beginning with nursery stories. Probably we have been hard-wired for drama since antiquity. Think of the Greek myths, Aesop’s Fables, or Arthurian legends from the Middle Ages—they are still being adapted and updated after hundreds or even thousands of years, still giving new meaning and pleasure to people’s lives. The nameless folk who shaped them are the giants upon whose shoulders we all stand, and the enduring presence of folk art—in plays, poetry, music, architecture, and traditional tales—should alert us to how many of our tastes are ancestral and shared with each other.

Since the documentary is a tale about the actual that is consumed at a sitting, it probably carries on the oral tradition. Whenever it connects with the audience’s emotional and imaginative life, it succeeds. One must concern oneself, therefore, with more than self-expression, which can be narcissistic. Instead, one must learn how best to entertain and enlighten an audience. Like other strolling players, the filmmaker has a precarious economic existence, and pleases the audience or goes hungry.

After the first assembly, fundamental issues emerge. Maybe you see your worst fears: your film has no less than three endings. Your favorite character makes no impact at all beside others who seem more spontaneous and alive. You have to concede that a sequence in a dance hall, which was hell to shoot, has only one good minute in it. A woman you interviewed for a minor opinion actually says some striking things and is upstaging a contributor whom you considered more important.

Avoid trying to fix everything you now see wrong in one grandiose swipe. Also, forswear the pleasures of fine-tuning or you soon won’t see the forest for the trees. Wait some days and think things over. Soon you’ll be ready to tackle the major needs of the film.

If you don’t have a current working hypothesis, why not practice with DP-3 Brief Working Hypothesis? Then try using DP-1 Dramatic Content Helper to help put your ideas under dramatic expectation.

1. See Matt Zoller Seitz’s excellent and illuminating review, www.rogerebert.com/reviews/at-berkeley-2013.