Fun with Formulas and Functions

Maybe you won’t consider this chapter fun, exactly (although I do), but it should at least remove any stress accompanying your dealings with formulas and functions.

It starts with the two quick ways of accessing the most common spreadsheet functions (such as SUM and AVERAGE): the Function Button and the Quick Calculations Bar (which has an alternative identity as the Smart Cell View).

Then we’ll move on to creating your own formulas, starting with what you need to know about basic math operations as they relate to entering information in a formula: Typing Mathematical Operators and The Order of Operations. Next, we’ll make sure you understand Cell References—the different ways you can refer to cells; it’s particularly important to understand Relative vs. Absolute Cell References.

You’ll also learn how to work with The Formula Editor, building formulas and handling tokens inside in it, and then learn about Functions and Arguments—the built-in formulas that a spreadsheet can’t live without—and see how helpful The Function Browser can be.

The Function Button and Quick Calc Bar

The Function Button and the Quick Calculations bar provide very different approaches for quickly entering common spreadsheet functions—most of which provide handy statistics such as the average of a group of numbers, or the largest or smallest number in the group. Both approaches are quick and simple—no experience required.

Function Button

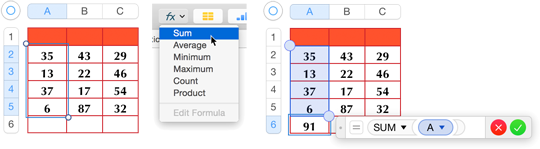

The most commonly used spreadsheet functions are available at the click of a button—the Formula  button in the toolbar:

button in the toolbar:

- Select cells in a column or row that have numeric entries, making sure there’s a blank cell available after the selection.

- Click the Formula button in the toolbar and choose a function from its menu.

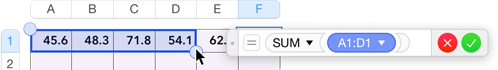

Numbers enters the result of the function, such as the sum of the cells, in the cell beneath a column selection or to the right of a row selection. Behind the scenes, it has put a formula into the formula editor, using the function you chose from the menu and the cells you selected as its argument (Figure 88).

Here are some important things to note about this simple procedure. I use the SUM function as an example, but they apply to all choices in the Function menu:

- A formula OVERWRITES EXISTING DATA when it’s plopped into a cell, so make sure there’s a blank cell after the end of the selection.

- If you select an entire column or row with a click on its label, the formula is entered in the last cell, even if there are available blanks before it, and whether or not it’s defined as a footer row.

- If the entire column or row is filled with numbers, and you’ve selected all the cells, a new column or row is added to the table to accommodate the results.

- To sum several columns, select all the cells you want included and then choose from the Function menu. The results are inserted at the bottom of the selection, in each column.

- To sum several rows, select them by clicking or dragging across their labels (the numbers in the Row bar at the left of the table) so that Numbers knows you want to work with the rows in the block you’ve selected, and not the columns. Then choose from the Function menu.

All but one of the other functions in the Function button menu are straightforward:

- AVERAGE: The AVERAGE function provides what we usually refer to as an “average,” but more properly, it’s the arithmetic mean (and that’s pronounced arithMETic). The related MEDIAN and MODE functions are available when you’re working in the formula editor.

- MINIMUM and MAXIMUM: These find the smallest and largest values in a range of cells.

-

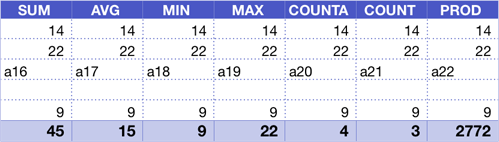

COUNT (COUNTA): This is the problem child in the family. The menu lists the COUNT function, but in fact it’s the COUNTA function that’s entered into the cell, as you’ll see if you check the cell’s formula afterward. It’s beyond my imagination (and, like Han Solo, “…I can imagine quite a bit”) why it’s listed this way, especially as it’s correctly defined as COUNTA in the Quick Calc bar.

The COUNTA function counts how many cells in its referenced range are not blank (think of it as COUNTA for data). COUNT, on the other hand, counts cells that contain numbers, expressions that resolve to numbers, or dates, ignoring both blanks and any other kind of data, such as text (Figure 89).

-

PRODUCT: The only non-statistical function in the menu, this multiplies the selected cells together using the PRODUCT function instead of mathematical operators. So, you wind up with

PRODUCT(B1:D1)instead ofB1×C1×D1.

Quick Calculations Bar

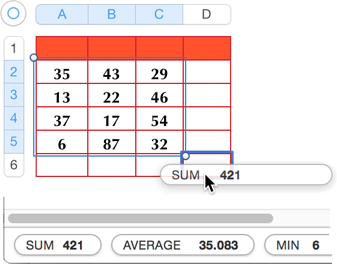

At first, I thought the Quick Calc bar at the bottom of the Numbers window was just a quick reference—you’d get an immediate idea of the sum, average, and so on, of any cells you select. Which, of course, you do, and that’s a convenience even if it went no further.

But then I wondered… and, yep, by golly, drag one of the statistical tokens into any cell in a table, and the appropriate formula, calculated from whatever’s selected in the table, is entered in that cell, no matter where you drop the token (Figure 90). And there’s the big difference between using the Function button and the Quick Calc bar: with the former, the formula is entered in a blank cell adjacent to the selection, while dragging from the latter lets you place the formula anywhere.

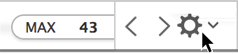

The Quick Calc bar starts out with tokens for five of the six functions in the Function button (PRODUCT is missing), but you can customize it:

- Add a token: Add other functions by selecting them from the more than two dozen listed in the Action pop-up menu at the far right of the bar (Figure 91).

- Reorder the tokens: Drag them to their new positions.

- Remove a token: Uncheck it in the Action pop-up menu.

- Scroll the overflow: When your token collection no longer fits in displayed area of the bar, scroll it by clicking in the arrows at its right end (shown in the figure above), or use a two-finger swipe on a trackpad.

Formula-building Basics

You may be eager to get to the actual formula-building part of working in the formula editor, but first there are some fundamentals to cover.

Typing Mathematical Operators

To enter formulas, you need to know basic computer-math conventions for typing multiplication and division, and other math symbols.

But first, a reminder: before you type even a simple formula like 1+1 into a cell, you must start with an equals sign to tell Numbers that it’s a formula and not a string of numbers and symbols that might stand for, say, a serial number. As soon as you type the equals sign, the formula editor pops open. Just keep typing; edit, if necessary, within the editor, and click Accept  or Cancel

or Cancel  when you’re finished. (I have lots more to say about the formula editor later, when it comes to working with functions.)

when you’re finished. (I have lots more to say about the formula editor later, when it comes to working with functions.)

To enter basic mathematical operators in the editor:

- Addition and subtraction: Type the standard plus and minus signs.

-

Multiplication and division: The asterisk (Shift-8) has long served as the multiplication symbol on computers, while the forward slash (/) is used for division. But Numbers is elegant in this regard: type either of those symbols in the formula editor, and they are automatically transformed to genuine multiplication and division symbols when you close and reopen the editor. So, type

3*4/8and you’ll get3×4÷8. -

Exponents: Type the caret (

^) in front of the exponent:6^3.

The Order of Operations

When you construct a formula that includes multiple mathematical operators, some operators take precedence over others, so the numbers aren’t always handled from left to right. (This hierarchy, or order of operations, is not specific to Numbers or spreadsheets, but a math basic.)

Multiplication and division are of equal importance, but are performed before addition and subtraction (which are of equal importance to each other). Reading from left to right might lead you to believe that 22-8÷2 is the same as 14÷2 but that’s incorrect: with division taking precedence over subtraction, it boils down to 22-4.

You can override the normal order of operations with parentheses; items inside parentheses are always performed first. So:

22-8÷2 = 22-4 = 18

but

(22-8)÷2 = 14÷2 = 7

Cell References

The basic cell name is its column and row—in effect, its coordinates: B5, K9, AB14. (After Z, columns have double letters: AA, AB, and so on.) But, cell references are often much more complex. In this topic, I tell you about several types of references:

- Referencing multiple cells, in groups such as an entire row or column, by coordinates, and single or multiple cells in another table or on another sheet (just ahead)

- Using written out names to refer to cells (see Referencing by Header Names)

- Creating a cell reference that won’t change when a formula is copied (in Relative vs. Absolute Cell References)

Cell Coordinates

You’ll usually enter cell references in a formula by clicking in, or dragging across, table cells. Still, you need to know about the many ways to refer to cells because sometimes you will want to type them, but also because Numbers enters these reference when you click and drag the targets, and you’ll want to be able to read them in a formula. Here’s what references can look like:

-

Single cell: Its column and row:

A1orB247. -

Range: Its upper-left and lower-right cells:

B2:B12orA1:AF247. -

Entire row: The row number twice, with a colon in between:

2:2. -

Multiple entire rows: The first and last row numbers, separated by a colon:

2:4or15:32. -

Entire column: The column letter:

B. -

Multiple entire columns: The first and last column letters, separated by a colon:

B:D.

-

Cell or range in another table on the same sheet: The table name, followed by double colons and the cell reference:

TableName::B5orPersonal::B5:J12. -

Cell or range in another table on a different sheet (tab): The sheet name, the table name, and the cell coordinates, with double colons between the elements:

SheetName::TableName::B5orExpenses::Personal::B5:K9. You can’t reference a cell in a different document.

Referencing by Header Names

You can make your formulas easier to read by referring to them by row and column header names instead of row coordinates. To set this up, choose Numbers > Preferences > General and check Use Header Names as Labels. And then set up row and column headers—not just labels for your data, but defined row and column headers, as described in Headers and Footers.

With this setup, the formula editor uses cell references like January:Income or Q1 Profit instead of C:20. If you type C:20 into the formula editor, or click the cell to enter a reference, the formula editor substitutes the header names. As a bonus, if you start typing a header name in the editor, you’ll get an autocomplete suggestion for any matches.

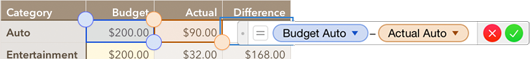

Figure 92 shows a slice from the Personal Budget template that uses header references instead of cell coordinates; you can see how much clearer the formula is than if it referred to B2-C2.

Here’s how to refer to cells by header names:

-

Single cell: Give the header names for the column and row, citing the column first. In the previous figure, that’s

Budget Auto,notAuto Budget,instead ofB2. -

Entire row or column: Use the header name instead of the row number or column letter:

Auto,Entertainment,Budget,Actual. -

Cells, rows, or columns in another table or sheet: If the cell name, based on its row and/or column header, is unique to the document (that includes all the tables in all the tabs), you can refer to it by just its name:

BudgetAuto. Otherwise, first identify the table or sheet followed by a double colon and then the named cell reference:SummarybyCategory::BudgetAuto. Usually, you’ll enter such a reference by clicking in the other table so you don’t have to think about capitalization. If you type it, however, you can ignore capitalization and Numbers will correct it for you when you enter the formula. Spelling and spaces, on the other hand, must be exact, or you’ll get a formula error.

Relative vs. Absolute Cell References

If you set up a function that averages the numbers in a column—AVERAGE(B2:B4), say—and then copy or autofill it to another column, the function’s argument changes to accommodate the move; it refers to different, analogous cells, such as AVERAGE(C2:C4) (Figure 93). This is called relative cell referencing, since the changes keep the referenced cells relative to the formula’s cell. In effect, this copied formula really says “average the three cells above me.”

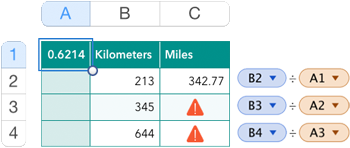

But sometimes relative cell referencing isn’t helpful. Say you have to convert from kilometers to miles, so you put the conversion factor (0.6214) in a cell and refer to it in a formula. When you copy the formula down, you get errors because the default relative referencing refers to empty cells (Figure 94).

A1 change to refer to empty cells.To avoid that problem, formulas can use absolute cell referencing, which means the cell references don’t change when you copy or autofill the formula. Absolute references are indicated by using a dollar sign in front of the row or column reference (or both); an absolute reference to cell A1 in the previous figure would be $A$1. In a situation where you want the column reference to remain static but the row to change, you’d use $A1; for the reverse, you’d use A$1.

You can type the dollar signs, or use the popover menu from a cell token in the formula editor (Figure 95). Check Preserve Row or Preserve Column, or both; you’ll see the dollar signs inserted into the cell reference. (Tokens and their menus are covered in detail ahead, in Cell References and Tokens.)

The Formula Editor

There’s quite a lot to know about working in the formula editor efficiently, and this section provides the details. But let’s start with a quick look at how to get in and out of the formula editor:

- Select a cell and type an equals sign to open the formula editor. (If you type an equals sign and it appears in the cell, that cell is specifically formatted for text. In the Format Inspector’s Cell pane, choose Automatic from the Data Format menu to make the cell recognize the signal for the formula editor.)

- Click or type your way to the formula you need. For example, your formula could read

1+1orB2+B3×B4. Numbers changes cell references to tokens, as you can see in the figure below; I talk more about them a little later. - Close the formula editor by clicking the Accept

button or pressing Tab or Return to move to the next cell. (Remain in the cell by pressing Enter or Command-Return). To cancel your entry or edits, click the Cancel

button or pressing Tab or Return to move to the next cell. (Remain in the cell by pressing Enter or Command-Return). To cancel your entry or edits, click the Cancel  button or press Esc.

button or press Esc.

To re-open the formula editor, double-click the cell, or select the cell and press Option-Return.

A cell displays the results of a formula, but you can see the formula that’s stored in a selected cell in the Smart Cell View at the bottom of the window (Figure 96).

B5. Right: With B5 selected, the Smart Cell View shows the formula.Move or Resize the Editor

The editor is easy to move, which is a good thing, since it obscures its own and adjacent cells. Just place your pointer over the editor’s left edge until it changes to the grabber hand, and drag it.

It’s not obvious that you can resize the editor, especially since it automatically expands horizontally as a formula gets longer. To change the length or height, hover over either the bottom or right edge for a resize  cursor and drag. To change both dimensions at once, hover over any corner until you see the pointing hand and drag (Figure 97).

cursor and drag. To change both dimensions at once, hover over any corner until you see the pointing hand and drag (Figure 97).

If you click a sheet tab when the formula editor is open, the editor stays floating on the screen, even when you’ve switched to another tab. This makes it easy to enter a reference to a cell in a far-off table with a simple click. You won’t have to remember the sheet, table, and cell name on one sheet—and the syntax for all of that info—to enter it in a formula on another sheet.

Cell References and Tokens

To enter cell references in the formula editor, click a cell, drag across multiple cells, or simply type (B12, for instance). The formula editor turns the reference into a token.

Numbers assigns each token a color in the editor; the token’s related cell is highlighted with that color, making it much easier to analyze the components of the formula. In addition, when the formula cell is merely selected, its referenced cells are colored both in the table and in the formula displayed in the Smart Cell View (Figure 98).

To change the cell reference at any point, click its token, which darkens in response, and then:

- Replace it: Click a cell, drag across multiple cells, or simply type.

- Edit it: Drag the blue handles at the corners of the selection in the table to add or remove cells (Figure 99).

-

Move it: If the cell range is going to be the same size, but shifted (changing from

A1:D1toB1:E1, for instance), you can drag the selection itself—not with the handles, but from within the highlighted area—to a new position.

You can also use the Option and arrow keys, with and without Shift, to enter and edit cell references. I discovered this accidentally, and am not quite sure how handy it will be in the long run. There are two approaches:

-

For a selected token: Press Option and an arrow key to move the highlight that shows referenced cells in the table. If for instance, your token refers to

C8and you press Option-Down arrow, the token changes toC9. If the token is for the rangeB2:B8, pressing Option-Right arrow changes it toC2:C8.Add Shift to expand the size of the cell reference range instead of moving it. If the token is for

C8, Option-Shift-Down arrow changes it toC8:C9. -

For a new cell reference in the formula: When the blinking insertion point is in the formula (click in a spot, or press the Left or Right arrow key to deselect a token and place the insertion point), press Option to see a cell-reference token

whose color varies depending on the color of any nearby tokens. With Option still down, press an arrow key to get a cell reference to a cell adjacent to the currently selected one.

whose color varies depending on the color of any nearby tokens. With Option still down, press an arrow key to get a cell reference to a cell adjacent to the currently selected one.

Add the Shift key, and your selection expands in the direction of the arrow key you’re using.

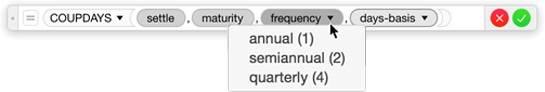

Function and Argument Tokens

Cell references aren’t the only tokens in the formula editor. Functions and Arguments are represented by tokens, too.

When you enter a function that needs arguments, the formula editor prompts you with a token for each one. If the argument uses something like a number code to represent an option, its menu helpfully provides a cheat sheet (Figure 100).

Enter and Edit Functions from the Keyboard

Are you a keyboard jockey? You can enter all of the information you need in a formula without leaving the keyboard.

The formula editor tries to read your mind as you enter information, popping up suggestions as you type. You can click on a suggestion, but you can also select it with keystrokes. And, since a selected token can be replaced by typing, and you can move between argument tokens by pressing Tab and Shift-Tab… you get the idea. Try this procedure to familiarize yourself with the click-free way to enter formulas:

- With a cell selected, type an equals sign to open the formula editor.

- Type

ran. As you typer, Numbers suggests the nearest alphabetic equivalent, RADIANS, inside the token, and displays a bar showing other functions that begin with those letters. When you get ton, RAND is suggested in formula editor, and the bar beneath it narrows to include only functions that begin withran. - Hit Tab to move to the bar; the selection jumps to RANDBETWEEN in the bar, because you’ve already declined to use the first item, RAND. (If you tab again, you’ll move to the next item in the bar, which might be displayed partially, or not at all; if you tab beyond the last choice, it cycles back to the first one.)

- Press Return to enter the RANDBETWEEN selection; the bar disappears, and the function editor displays the function and its argument tokens (Figure 101). The first argument is already selected; type a number to replace it. Press Tab to move to the next token and then type another number.

Figure 101: Top: Typing Rsupplies many suggestions, but by the time you typeRAN, the choices narrow and you can use Tab to select RANDBETWEEN. Bottom: When the function is in the editor, you can tab from one token to another. - Press Command-Return to close the formula editor.

Work with Text in the Formula Editor

Sometimes it’s easier to work with text in the formula editor rather than with its tokens. Say, for instance, you entered a cell reference for something on another sheet: do you really want to go to the other sheet and reselect the area when all you need is to change B2:B7 to B2:B8? Or scroll through the Function Browser to replace a function token when you just need to change HLOOKUP to VLOOKUP?

You can change a single token, or the entire formula, to text:

- Change a token: Double-click the token.

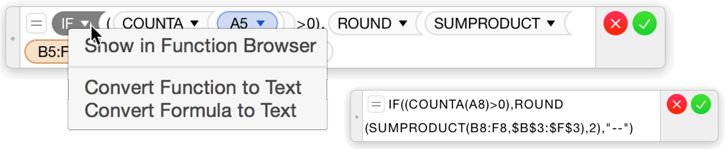

- Change the entire formula: Open the function token menu and choose Convert Formula to Text (Figure 102). (Choosing Convert Function to Text is the same as double-clicking the function; Show in Function Browser is covered later, in The Function Browser.)

To return to the token view, close the formula editor and reopen it. You can do this quickly with the keyboard: press Enter or Command-Return to close the editor but remain in the cell, and then press Option-Return to open the editor again.

Functions and Arguments

A function is a built-in formula that spares you from reinventing the wheel when you perform mathematical (or text-based) operations. Calculating an average, for instance, requires adding up a series of numbers, and then dividing that sum by how many numbers you added together. In spreadsheet-speak, that formula might look like this: (A1+B1+C1) / 3. But, instead of typing all that (taking time and risking errors), you can use a function—AVERAGE—that knows to add things together and then do the division.

You tell the function which numbers to use by providing one or more arguments in parentheses. If the argument refers to cells containing numbers, the reference could be a cell range AVERAGE(A1:C1) or a list AVERAGE(A1,B1,C1). Some functions need, or can use, specific numbers rather than cell references as arguments. These are sometimes referred to as constants because… duh… they don’t change, while references can change when cell contents change. So, you could actually use a formula like this: AVERAGE(12,14,18).

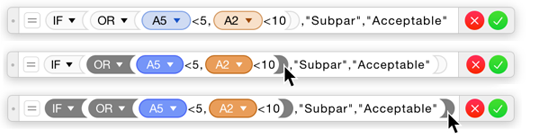

Functions have very specific needs, and you must use the correct syntax—the grammar of functions—or they won’t work. For instance, you can’t simply say B1 OR C1; you must use OR(B2,C1). But you don’t have to worry about remembering the correct syntax for hundreds of functions. As you saw in the previous section, when you enter a function in the formula editor, it comes with tokens that stand for each of its arguments, with the proper syntax already in place.

Nested Functions

It’s not unusual to use more than one function in a formula: =SUM(A2:A27) + RANDBETWEEN(2,10) for instance. What’s slightly less usual, but potentially very confusing, is the use of nested functions—one function inside another, with the inner one replacing an argument the main function needs.

In an example elsewhere in this book, there’s a small table that calculates whether a customer gets a discount, which happens when one purchased item is over $40 or the total order is more than $100. Cell B5 holds the total order with SUM(B2:B4); cell C2 checks for the highest-priced item with MAX(B2:B4). The discount calculation checks if B5 is over $100 or C2 is over $40. The part of the formula that checks whether either discount threshold is met uses the OR function and references the cells holding the calculations:

OR (B5>100, C2>40)

It’s unnecessary to do this two-step process, however, because the calculations themselves can go directly in the OR construct. This is the same formula snippet as the one above, with the cell references replaced by the formulas:

OR (SUM(B2:B4)>100, MAX(B2:B4)>40)

In the real world, these nested functions would be further nested in the fuller formula, which uses the IF function to describe the results if either of these formulas is true, but there’s no reason to go there now—you get the picture.

Mind Your Parentheses

Numbers bends over backwards to help you parse function components by displaying the function name in an odd shape that serves as part of an opening parenthesis; the closing parenthesis a matching chunky moon-slice.

When there’s more than one set of parentheses in a formula, you can click on any parenthesis to highlight its partner, and all the tokens in between, to help you analyze the elements and how they go together (Figure 104).

If you’re typing or editing a function with parentheses, you can just type them regularly and they’ll be replaced with their graphical representations. And, you can skip typing a final closing parenthesis completely; Numbers inserts it for you. (By “final,” I mean the last one in the formula, not the closing parenthesis for any interior component.)

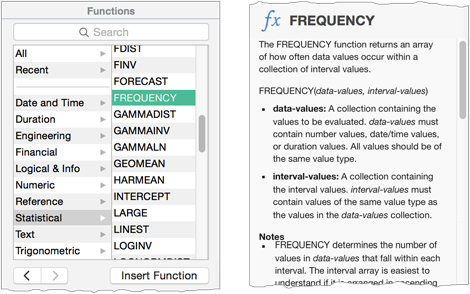

The Function Browser

The Function Browser replaces the Format Inspector in the panel at the right of the window the moment you type an equals sign to start a formula or otherwise open the formula editor. The Sort & Filter Inspector, however, holds its ground under these circumstances, so to see the Function browser you must either choose Show Function Browser from a function token menu or—in another interface oddity—click the Format Inspector  button.

button.

The Browser’s upper area lists categories and functions. Beneath that is description of the selected function (Figure 105).

To use the Function Browser:

- Select a function to see its description and syntax in the lower part of the Browser.

- Use the search field at the top of the Browser to jump directly to the function you want.

- Click the Previous and Next arrow buttons under the list to review functions you’ve previously selected.

- Put a selected function into the formula editor by clicking the Insert Function button.

- Insert any function by double-clicking its name in the list.