9

Commentary

Criminal Capital for Illegal Enterprise

In Chapters 3 and 7, we discussed several themes surrounding criminal enterprise. This chapter continues with this enterprise focus by describing how criminal social and cultural capital, in the form of attitudes, skills, networks and ways of thinking is necessary for long-term viability in criminal enterprise.

The “job” demands facing any prospective dealer in stolen property in-volve managing the economic and legal realities of running a fencing busi-ness. On the economic side, the would-be fence must confront and solve the problems that present themselves to any business: capital, supply, demand, and distribution. On the legal side, he must cope with the dangers posed by control agents and the potential disruption of his fencing business. The material here, along with some prior writings on the trade in stolen goods (see review in The Fence), suggests that successful fences typically must engineer five demands or interrelated conditions. These conditions—which shape whether fencing stolen goods is objectively possible—must be more or less continuously and simultaneously met, but for descriptive purposes each may be considered separately.

1. Keep up-front cash. Most deals are cash transactions, so an adequate supply of ready cash must usually be on hand. Several factors contribute to the general rule in fence-thief dealings: the fence must pay on the spot or within a relatively short time frame. These factors are the need for secrecy, inability to call on the law to enforce agreements, and, frequently, the thief’s need for money. More so than in legitimate commerce, running a fencing business requires upfront cash, or at least the ability to raise cash quickly.

2. Display knowledge of dealing-knowing the ropes. Learning to become a dealer of stolen goods revolves around four themes. The first is the sharpening of one’s larceny sense or “eye for clipping,” that is, learning skills and attitudes conducive to general forms of theft and fraud. Second, there is learning how to “buy right”—to buy and sell stolen property profitably while maintaining the patronage of both sellers and buyers. Third, there is learning how to “cover one’s back”—to buy and sell regularly and routinely without getting caught. Fourth, intertwined with the other learning experiences, is learning how to “wheel and dear’—to exploit one’s environment, to make one’s opportunities rather than simply buying and selling stolen merchandise when the opportunity presents itself.

3. Maintain connections with suppliers of stolen goods. Persons engaged in certain occupations, such as pawnbroker, jeweler, secondhand dealer, salvage yard operator, and auctioneer, are likely to be approached to purchase stolen property because of the similarity between the types of property commonly stolen and those routinely handled in their occupations. Likewise, bartenders, bondsmen, drug dealers, criminal lawyers, gamblers, and established thieves or hustlers (and many ex-thieves) also are likely to be invited to buy stolen property because of the types of people they routinely meet. Indeed, many ordinary citizens are likely to be approached at one time or another to buy stolen property.

The professional dealer differs from such persons by his ability to generate and sustain a steady clientele of suppliers in order to buy stolen property regularly and routinely. Creating a steady stream of willing sellers may not be difficult if the prospective dealer is willing to buy from the thief with a low level of sophistication. But building up a clientele of thieves who steal merchandise of good value and with whom it is also relatively safe to do business is a quite different matter. In this regard, the fence’s suppliers of stolen goods may include not only burglars, shoplifters, car thieves, and other criminal types, but truck drivers, warehouse workers, shipping clerks, salesmen, or corrupt police.

4. Maintain connections with buyers. The successful fence must have continuing access to buyers of stolen merchandise who are inaccessible to most thieves. Some fences with legitimate holdings may sell stolen goods to their customers but many fences also must rely on other outlets. Many, if not most, fences rely on outlets other than their legitimate business for disposing of the stolen merchandise they purchase. Thus, in what is probably a more difficult and complicated matter than making connections with thieves and suppliers, the prospective dealer needs to establish contacts with merchants or other secondary purchasers as markets for selling the stolen property he has bought.

5. Gain the complicity of law enforcement. By buying and selling stolen property on a regular basis, the fence is likely to acquire a reputation as a “dealer” not only among thieves but among the police. He must, then, contend with the prospect of aggressive enforcement efforts targeted at him. The fence can handle this problem in one of two ways. He may corrupt the authorities with favors, such as good deals on merchandise or cash payments, with the latter paid directly by the fence or made through the services of a well-connected attorney. Or the fence may play the role of informer, and supply criminal intelligence to the authorities in exchange for being permitted to operate. He may aid in the recovery of stolen property that police are under special pressure to recover, and he may facilitate the arrest of thieves or other criminals. Many fences employ both strategies—bribery and informing. Also, some fences may discourage thieves from informing or testifying through a threat or reputation for violence that serves as a halo for the fence’s activities. The actual threat (“leaning on” people, as Sam says) may be applied directly by the fence or is handled through the services of the fence’s connections. Finally, although official complicity is a protection for many fences, all employ procedures aimed at frustrating attempts to prove illegal conduct by making their fencing activities indistinguishable from those of the legitimate business world.

Particular dealerships may require different solutions to the economic and legal realities of running a fencing business and the five conditions above, as illustrated in the shifts and oscillations characterizing Sam’s fencing involvement. Some fences may need only a modest amount of up-front cash because they deal with thieves who are willing to give them short-term credit. Some fences may have extensive legitimate holdings or may deal in only one or two product lines, so that they have less need to develop outside markets for disposing of the stolen property they buy. Still other fences who deal with a handful of carefully selected thieves may manage to keep their fencing involvement more or less secret. They thus will have less need for complicity from law enforcement than the fence who deals with a wide array of general thieves, many of whom are prone both to police arrest and informing.

The conditions for successful fencing and the necessity of developing solutions to the various demands of the enterprise require definite skills and criminal capital. Just as Sutherland (1937) emphasized the importance of acquiring skills and social resources in The Professional Thief, we explain the skills, character traits, and types of criminal social capital necessary for fencing and perhaps other criminal enterprise.

Criminal Capital for Criminal Entrepreneurs

Entrepreneur or “capitalist”—someone who, in the pursuit of profit, takes the initiative in order to manipulate other persons and resources.

—Darrell Steffensmeier, The Fence

There are differing views in the criminological literature about the talents and attributes of criminals and career thieves, including professional thieves and illegal entrepreneurs. One view emphasizes the professionalism and the acquired criminal capital of at least some categories of career thieves and depicts them as being highly skilled (e.g., Sutherland 1937, 1947). The other common view is that criminals are relatively unskilled and inept. The “anyone can do it” view is held by many criminologists. In this popular view, it is conscience, fear of sanctions, and self-control, rather than lack of criminal skill, that keeps noncriminals from committing crimes (see Gottfredson and Hirschi 1990; Bennett, Dilulio, and Walters 1996).

This view of ineptitude is not shared by ethnographies of crime, nor by most criminals themselves. Sam’s narrative suggests that not only con men and other elite criminals, but thieves, drag dealers, and others who support themselves through crime manifest a portfolio of skills, and some exhibit considerable entrepreneur ship. This can be said even of many habitual thieves, in spite of Sam’s typically derogatory stance toward them.

Sam’s narrative supports a middle-of-the-road position on the skill-level issue: most career thieves are not exceptionally talented, as Edwin Sutherland (1937) tends to portray them; but neither are they as inept and slothful as contending views hold. Some criminals are much more skilled than others, and some may not be very skillful at all. Importantly, those who possess a fuller portfolio of crime-relevant skills are more likely to be respected and successful criminals and criminal entrepreneurs.

In a general sense, a mix of interactional, social, perceptual, organizational, technical, and even perhaps physical skills are needed to survive and to succeed as a thief or illegal entrepreneur. Errors of judgment and poor performance or effort, especially early on in one’s career, can end it. The fullest complement of these skills, obviously, is not required of every professional criminal, and some talents are more required of some criminal specialties than others. The skills required of the seasoned burglar may overlap to some degree but will be different in many respects from the skills required of the dealer in stolen goods. Craftsmanlike skills are prerequisites for successful burglary, whereas ingenuity, business sense, and “people skills” are more required of successful fences.

Further, the talents and attributes that are prerequisites for involvement may vary within a criminal specialty. The successful safecracker, for instance, who commits burglaries for cash must have technical skills that are not necessarily required of the burglar who specializes in antique theft—which may require specialized knowledge about the value and marketing of antiques. Likewise, the successful dealer in stolen automobiles must be able to do different things than the dealer in jewelry, furs, or guns. On the other hand, the specialist fence who only deals in stolen goods that match his legitimate trade does not have to do the vast number of things required of the generalist fence.

What are the necessary talents and attributes for being able to support oneself through crime or to be relatively successful at it? The specific attributes of criminal capital described next are helpful, if not required, qualifications for becoming an established thief or illegal entrepreneur. However, some offenders may be able to compensate in one area for what they lack in another.

Heart: “Nerve” and “Coolness”

“Most people could never hack it” is a common statement of seasoned thieves, in reference to the dangers, risks, and physical demands inherent in a criminal lifestyle. To gain respect or to recruit associates, the thief or illegal entrepreneur must demonstrate that he has “heart.” “Heart” is a set of traits, a combination of physical and mental toughness, of courage and coolness. To have heart is to be someone who does not scare easily and who is able to perform at one’s best when the stakes are high and the risks great. The ability to keep cool, remain in control, and exercise fast-action judgments in situations that are unpredictable and suspenseful are highly valued work skills. Having these skills contributes to status and respect in the underworld for those who possess them. As with most work skills, they can become something that one is proud of.

The chief basis of heart is courage and tenacity. These qualities are not easily acquired; one either possesses them or one does not (unlike, “coolness,” which can be partly acquired). Heart implies mental toughness, the capacity to endure pain if necessary and an ability to see a task through in difficult situations. It also implies the ability to “get rough,” should the need arise. Physical toughness and some “muscle” are essential for dealing with security safeguards (e.g., watchdogs) and for managing criminal associates.

Too much nerve can be a drawback, however, since it can lead to carelessness. Being brave to the point of being “crazy,” to the point that the freedom or safety of oneself and that of one’s criminal associates are jeopardized, is not helpful. Instead, nerve should be coupled with “coolness.” Coolness refers mainly to the ability to keep one’s composure in the face of difficulties encountered on capers and/or during illegal transactions; it is staying calm and circumspect when the action is heavy. Coolness also may refer to the day-to-day living of the thief—that he is careful not to draw unwanted attention and “heat” by bragging about his criminal exploits or by living in a high-profile manner (see also Irwin 1970:9-10; Akerstrom 1985:21).

Heart, nerve, and coolness are important for choosing associates, and for being recruited by other offenders. Someone who scares easily, who cannot keep his nerve, or who caves in when the “going gets tough” may put his partner or associates in a “tight” spot and therefore is not to be trusted. Losing one’s nerve is one main reason for quitting at least those criminal activities that require courage (e.g., burglary). Also, using either alcohol or narcotics before committing crimes in order to get the needed confidence or “false courage” is a strongly disapproved but fairly common practice.

Inventiveness, Scheming, Ingenuity

The criminal activities and/or lifestyles of many thieves and illegal entrepreneurs require a lot of inventiveness and ingenuity. This inventiveness is seen in various ways. First, it is seen in “the ability of property criminals to view everyday surroundings—buildings, situations—in the light of crime potential” (Akerstrom 1985:25). Second, inventiveness is required because of the difficulties in establishing contacts, the non-automatic process of tutelage, the lack of possibilities for realistically “rehearsing” criminal acts, and the dif-ficulty of “beating the system” for success and profit.

The way thieves and criminal entrepreneurs learn their work has often been described as a tutelage process, i.e., older or more skilled ones train their young or less skilled companions. However, this implies a recruitment process that is too automatic and uncomplicated. The reality involves a good deal of effort by the prospective thief. Established thieves are often not open or friendly toward newcomers—who may draw attention to the group or talk too much. A certain amount of testing and worry (and even competition) always exists. Instead of being open and diffuse, the tutelage process is one of “learning as you go” by watching, by asking others, and by experimenting or “trial and error.” Criminals often have to figure a lot of things out themselves or improvise, since nobody has ever told them what to do. This also implies that, at least to some extent, thieves and illegal entrepreneurs must be hardworking and energetic.

Strategies also need to be developed for outwitting the system and for showing that one can exercise control. One of the main strategies is having a front for the authorities. For example, Sam used his legitimate business as a front, and earlier in his career, had a phony job lined up in order to get parole. Other fronts can include use of welfare or unemployment as a front for illegal sources of money, and part-time jobs and live-in girlfriends as fronts for sta-bility and sources of alibis.

Successful illegal entrepreneurs such as large-scale fences and all-around racketeers need to be able to wheel and deal They require what the fencing literature refers to as ingenuity—the ability not only to discover or act upon opportunities but also to make them. One must actively exploit his environment in order to create and control his opportunities, rather than relying on chance opportunities. This is reflected in terms such as “operator” or “schemer,” which are often used by acquaintances to describe illegal entrepreneurs.

The “wheeler-dealer” or professional fence, for example, in a kind of free-floating fashion, is required to make success happen by buying and selling stolen property in ways that appear to be no different from what others in his environment normally and legally do. That is, he must hold his own and not be outhustled by thieves and other trade partners; and he must make the contacts and gain the confidence of lawbreakers, law enforcers, and all others on whom his success as a dealer ultimately depends. Wheeling and dealing is a combination of cunning and resourcefulness, and it is an ongoing creation of the dishonest possibilities of the entrepreneur’s environment. It builds on his knowledge of the suppositions of the underworld, the conventions of his business environment, and the discretionary workings of the law.

Practical Knowledge of Things, Language, and People

Whereas modern society puts a premium on knowledge that is associated with theoretical and reasoning skills, the underworld rewards practical knowledge—the ability to implement in a practical way a project or task, not just theoretically knowing how (Akerstrom (1985:24;77ie Fence 1986). Even though many criminals may not need specialized craftsmanship, they do need a lot of practical knowledge about things, language, and people: how to break into a house or store, how to gauge the value of what they steal, how to acquire information about would-be associates or the police, how to handle people, how to judge potential buyers. This kind of knowledge is not easily learned from books, if at all, but must be experienced and lived.

The practical knowledge required of seasoned criminals builds on their street knowledge described below; it also complements and extends the sen-sibility of knowing how to do practical things that characterizes many blue-collar and lower-strata members of society who—like thieves—need compar-atively more practical knowledge than other groups in order to get by in the world. Whereas theoretical and reasoning skills are considered superior among professionals and academics, criminals and working-class men value practical knowledge.

That the emphasis on the existence and importance of practical knowledge is even greater among criminals stems partly from the lack of protective institutions for appeal if they are cheated, partly from the lack of traditional sources of information such as certificates or licensing for acquiring knowledge about people, and partly from the free-floating and happenstance work environment they face. Criminal pursuits are characterized by less specialization and routine performance than noncriminal pursuits. Consequently, making a living through crime requires much more in the way of individual decision-making and, perhaps, greater judgment and knowledge about a wide range of things. Learning how to get that information through trial and error, through associates, and through underworld grapevines is crucial, and often involves inventiveness and effort as well as the developed ability to “read” others and discern good from bad information.

Street Smarts

For many thieves and illegal entrepreneurs, practical knowledge is anchored in a heavy dosage of street smarts. Being “streetwise” means knowing the underlife of society; what is going on in it or how to find out; knowing what to say or not say to the police. It also means having the angles and not being easily duped by thieves and others who are both prone to and skilled at hustling. Furthermore, because things can change quickly in the underworld, being streetwise is an ongoing process and requires that one stay on top of things or have easy access to those who do.

Worldly-Wiseness

In addition to street smarts, a more far-reaching kind of practical knowledge—worldly-wiseness—is often required of illegal entrepreneurs. Being “worldly-wise” refers to a kind of all-around knowledge that blends together the suppositions of the theft subculture, the business community, and the society at large. Because they deal with so many different types of people and in a wide variety of situations, the generalist fence or all-around racketeer must “know a little bit of everything” and also be socially skilled enough to handle himself in different crowds and in different situations.

Social Skills

As in many legitimate occupations, the need for social skills and managing people is prominent among many successful thieves and criminal entrepreneurs. Seasoned thieves, hustlers, and illegal entrepreneurs exhibit social skills in many areas, including identifying and “sizing up” others, “passing,” making contacts, and managing other people. Regular hustling, wheeling and dealing, and thwarting discovery or arrest foster the development of a specific sensitivity for “reading” others in order to take advantage of them. This sensitivity is apparent for successful con artists, but other criminals—burglars, fences, drug dealers, even serious shoplifters—both need and often possess this role-taking proficiency.

Seasoned thieves believe they are adept at identifying others—another crook, an undercover policeman, a prospective customer, or accomplice. Exactly how this is done not well-defined or articulated by thieves, but apparently it is based on outward appearances, gestures, language, and so forth that give the thief a “feeling” or sense of “just knowing.” Often, it is not just identifying others that is important, but being able to “read” them, especially their character (what is the individual “made of,” can he be trusted, does he pose a danger, is he a “bullshitter”?) The ability to ferret out phony talk or behavior is especially valuable. Since contacts and trustworthy relationships are so important for criminals, it is not surprising that they emphasize its importance, and that they believe they are more able to determine whom to trust and mistrust than most people. These skills are learned or developed situationally, observing other thieves, and often via prison experience (as was the case with Sam).

In some situations, such as being caught in the act, criminals need to “act normal” or to “pass”—such as the safecracker’s need to “act natural” when someone enters the room where he is in the act of opening a safe. How one carries himself and plays the part that one impersonates is obviously important (see The Fence:\25). Criminals get a lot of practice at passing, since they encounter a lot of “strategic moments”:

Here, then, is a standard for measuring presence of mind, one involving the ability to come up quickly with the kind of accountings that allow a disturbing event to be assimilated to the normal. . . . Thieves, of course, have a special need to construct false, good accounts at strategic moments and have a word, “con,” to cover ability in this sort of covering. (Goffman 1972:263)

Fourth, criminals also develop social skills for managing or manipulating people. That is, criminals become skilled at social dramaturgy and presentation of self (Goffman 1959), and they need knowledge about others and what others consider normal. They often are “operators” who consciously calculate and adapt to take advantage of a situation. This may entail using deference and showing respect to the police, acting incompetent or stupid, or perhaps puffing up a counselor or parole officer to impress him or her favorably. Thieves have also usually acquired some practical legal sense of how to present themselves in the best light by showing remorse and conventionality (e.g., getting a regular job, or bringing a tearful mother or pregnant fiancée to court).

Finally, social skills are essential both in judging who of one’s associates is reliable and for establishing a reputation of being trustworthy. Thieves and others are more likely to do business with someone they trust, and as discussed later in this chapter, the one trusted is also likely to actively cultivate such a reputation.

Larceny Sense—“Eye for Clipping”

What criminologists label as “larceny sense”—the ability to perceive and capitalize on the opportunity to make money in less than legitimate ways—is required of thieves and illegal entrepreneurs. Larceny sense is partly attitude and partly acquired knowledge. In the underworld, it is the ability to read one’s environment with an “eye for clipping,” as when one thief says of another, “He has a good eye for clipping.”

To have larceny sense means, first, that one has “larceny in his heart,” or is willing to steal or swindle. He is unconstrained by conventional beliefs about what one is supposed to do. “A second and more subtle aspect of larceny sense is that one be observant and sensitive to circumstances and opportunities for illicit gain, and know when to take advantage of them or to desist” (The Fence:190). As Sam recounted in The Fence, “It’s being able to see the openings, to pick out the right information, to have a good eye for a score; it’s also knowing when to pick your spots or when to back away if the risks rise” (ibid.: 191).

By relying on commonsense interpretations of society, the average citizen also has the ability to perceive favorable theft opportunities, such as when police surveillance is greatest in a neighborhood, or when residences can be seen to be vacated because of newspapers left lying around. However,

It is the more specific socialization, such as that which occurs in early hustling experiences or in association with other criminals, that forges in the seasoned offender a complex series of visual cues not readily observed by the layman or the average businessman. Seasoned thieves and illegal entrepreneurs (like Sam) may be ignorant or unmindful of many social conventions but they are criminally sensitive to subtle social expectations and routines, (ibid.)

Business Skills and Knowledge

Successful criminal entrepreneurs must possess at least rudimentary knowledge about the product that is being sold or traded, its pricing, and its marketing. Acquiring such knowledge may require some inventiveness on the entrepreneur’s part but can generally be acquired by trial and error or coaching from one’s associates.

Illegal entrepreneurs (and some seasoned thieves) must also be knowledgeable about business practices and conventions, such as those utilized by the small business owner. Some knowledge of technical regulations and practices may also be required. And some illegal entrepreneurs must also possess technical or craftsmanlike skills pertinent to their particular trade or specialty (such as Sam’s skills at furniture refinishing and repair, antique restoration). They also must be sufficiently skilled at money management to maintain an adequate cash reserve to be able to purchase illegal goods and services in an unpredictable market. The particular kinds of business knowledge required will depend on the entrepreneur’s criminal specialty.

Trust, Being Solid

For those with whom the thief or illegal entrepreneur does business, reliability and trust are highly valued. Will the other person deliver? Is he dependable? Does he keep his word? Would he increase risks of trouble with the law? Established thieves and criminal entrepreneurs like Sam place a great deal of emphasis on being “solid.” In fact, they often consider it a prime reason for their rise and eventual success as a burglar, dealer in stolen goods, racketeer, or whatever. A “solid” person is one who is reliable and trustworthy. He keeps appointments, honors agreements, and seldom contributes to another’s trouble with the law. Some degree of trust is generated by the shared recognition that “we’re all doing things we’re not supposed to,” but concerns about trustworthiness are maximized when trouble arises with victims or with the police. Snitching is the most visible violation of being solid.

Because of its importance for acceptance in the underworld and for making connections, acquiring a reputation for solidness is often an active pursuit of established criminals (see also Pistone 1987). In this sense, too, the appearance of being solid—which is as important as its reality—will depend partly on the entrepreneur’s skills in convincing others of his trustworthiness.

Concerns about reliability and trustworthiness are greatest among established thieves and illegal entrepreneurs. This does not mean, however, that they are always paragons of integrity. Many, if not most, are at least occasionally prone to “pull the rug out” from under or “bury” a crime partner or associate by absconding when the action gets heavy, or by informing to the police. Some fences and racketeers, for example, compromise with the police and gain immunity from the law by informing on thieves or by assisting the authorities in other ways, and some illegal entrepreneurs set up other fences and racketeers as a way of eliminating or sabotaging competition.

Nonetheless, even though it is often violated, the rule of not informing is generally respected, if for no other reason than that general compliance with the code “honor among thieves” is essential for expediting ongoing transactions and sustaining an illegal business. (The Fence:203).

Acting as an informant can lead to loss of prestige, loss of business, or possible reprisals—as well as loss of self-respect, because of the loyalty and identification that many thieves and illegal entrepreneurs have with the criminal community, growing out of the common experiences that they typically share with other underworld members.

When they do inform, moreover, established thieves and illegal entrepreneurs usually do so selectively—meaning they are more likely to inform on the “riffraff,” the garden-variety thieves and hustlers who lack status within the criminal community. Sam’s narratives in The Fence (see pp. 148-51) as well as here illustrate this tendency. Established criminals are much less likely to inform on a good thief or another established criminal unless they are under very strong pressure to do otherwise. This evasion of the rale against informing is at least partly accepted in the underworld, in the sense that “creeps and assholes” are less deserving of protection from the police.

Seasoned thieves and good burglars apparently violate the rule against informing less frequently than most other underworld types. Fences are more trustworthy than garden variety thieves but less trustworthy than some other illegal entrepreneurs or racketeers. The latter may have considerable protec-tion from arrest because of extensive connections with the police and other public officials. Moreover, although “honor among thieves” is easily and fre-quently violated by many ordinary thieves, the average citizen or legitimate businessperson who finds him- or herself under pressure from the police is probably most prone to snitch.

Being solid also entails honesty in living up to agreements, paying debts, and not “ripping off” associates. However, considerable finagling and “getting over” are also customary in transactions among underworld operatives—for whom hustling and sharp trading are taken for granted. It is also important to note that honesty here also means honesty within one’s own group. To not cheat or steal from citizens or legitimate businesspeople, if the opportunity presents itself, is to be a sucker.

Muscle

Sustained involvement in crime is physically demanding both in the sense that physical prowess is often required to execute crimes and because the potential for violence and/or protecting oneself from getting “pushed around,” “ripped off,” or “snitched on” is ever-present. Strength, prowess, and muscle are useful for the successful commission of crimes, for protection, for enforcing agreements, and for recruiting and managing reliable associates. Physical strength and speed are obviously useful for committing crimes such robbery, burglary, breaking into autos, and many kinds of cartage theft; and, depending on the merchandise handled, may also be useful for dealing in stolen goods. Less obviously, they are important in theft and hustling activities (including drug dealing) in which the potential for violence or need for quick getaway is considerable. The criminal entrepreneur has to rely on his own or his associates’ ability to protect, threaten, retaliate, or inspire respect among crime associates (and perhaps others as well, such as victims or law enforcement).

For many illegal entrepreneurs and racketeers, then, violence or its threat is a critical resource for inspiring respect among one’s associates. However, the need for “muscle” does not mean that illegal entrepreneurs have to be “toughs” or heavies. As explained in The Fence:

Indeed, within the criminal community, persons thought too reliant on physical force for doing business or resolving difficulties tend to be distrusted. While it is fairly common in the underworld to hear persons expressing threats to injure or kill others who have violated their notions of fair play, these threats are carried out infrequently. A more likely response is that of slandering or blackballing the offender and encouraging others to avoid dealings with him. (p. 202)

Variability in Stock of Skills Across Types of Offenders

The skills required of seasoned criminals and illegal entrepreneurs are diversified, depending on the criminal’s specialty or range of criminal involve-ment. Some of the skills are at least partly common to all members of society but they are systematized and sharpened by the criminal who consciously uses them. These skills cannot be learned (at least easily) from books but must be experienced and lived. The combination of skills and distinctive stock in trade that make up the “working personality” of a seasoned thief will overlap with yet differ somewhat from those required of an illegal operator. The large-scale fence or all-around racketeer, for example, must possess or acquire a fuller complement of skills to effectively exploit his environment in large part because his activities blend together the underworld, the business community, and the society at large; and because he interacts with a much wider range of people, from thieves to businessmen and from the police to the public. Often, therefore, the talents of illegal entrepreneurs such as fences or racketeers are a mixture of the stock in trade of seasoned criminals as well as successful businessmen and salespersons.

The Fence as a Special Case of Networking: The Importance of Making Contacts

We described above key skills or qualifications that contribute to success as a criminal entrepreneur. Such skills are an important element of having or acquiring what, broadly speaking, can be referred to as criminal social capital (see also Uggen and Thompson 2003). A crucial element comprising criminal capital is contacts and supportive relationships or networks for criminal endeavors. In Sam’s view, “getting the connections” is the hardest obstacle for building and sustaining a criminal career. As Sam put it, success in crime requires “contacts, contacts, contacts.”

Though the importance of “connections” for success at theft or illegal enterprise is widely recognized in the criminological literature, there is very little description about the forms and dynamics of how contacts are actually developed and sustained. We learn from Sam’s narratives in the previous chapters that the process of making contacts in the underworld is similar in many respects to that in legitimate endeavors. But there also are qualitative differences, such as the greater importance of “trust” and “word of mouth” that characterize the underworld. Even more so than in legitimate commerce, contacts within the underworld derive from mutually beneficial exchanges among persons who trust each other (at least somewhat) and whose skills and resources are mutually supportive. They also often depend on the compatibility of the individuals involved. Typically, trust and connections are based on a preexisting tie or acquired through third-party mediation.

The relatively stable arrangements or partnerships a thief or an illicit entrepreneur develops may be characterized as his personal criminal network—a comparatively fluid and negotiable set of relations or working associations subject to considerable vacillation, even termination, as the varying parties attempt to come to terms with their lives and the relative payoffs they associate with one another. For the thief as well as the illicit entrepreneur, the process of building a personal network involves overlapping networks and an ongoing appraisal by prospective associates of one’s character and skills.

We can gain further perspective on the notion of contacts and networking as important criminal capital for the illegal entrepreneur by taking a closer look at the dealer in stolen goods, especially the generalist fence (like Sam) whose trade is characterized by diversity both in the kinds of products handled and the types of thieves dealt with. Our analysis here examines in more detail the nature of crime networks and networking skills, which were evident in the previous chapter’s narrative (“Running a Fencing Business”) and are further expressed in Sam’s next narrative (“Skills, Character, and Connections”).

As explained in The Fence (pp. 160-64), there are three general ways of making contacts: word of mouth, existing contacts introducing one to others, and one’s own active recruiting.

Word of Mouth

Word of mouth is your best advertisement ‘cause there ‘s a helluva grapevine out there. Really, there are different grapevines.

—Sam Goodman

Since the illicit entrepreneur cannot advertise publicly, he must rely on informal channels of communication to locate prospective partners with whom to hustle, burglarize, or buy and sell stolen goods. “Word of mouth” grapevines are probably the most common method of making contacts. Each grapevine mixes rumor and fact, and some grapevines provide more reliable information than others. Access to grapevines also varies. The “street grapevine” is accessible to almost anyone acquainted with the criminal community. Other grapevines may interface with it but are more narrowly confined to individuals in specialized locations. The latter grapevines tend to be almost personalized information channels linked both to specific cliques of offenders and to particular kinds of criminal enterprise.

Third-Party Referral: “Being Recommended”

Referral of one party to another is another way to bring thieves or criminal entrepreneurs together. Unlike word of mouth through the underworld grapevine, third-party referral is less diffuse and the information is more reliable. More established offenders and those not associated with the underworld (e.g., businesspeople, joe blows) are likely to link up with criminal entrepreneurs on this basis. For example, one businessperson may tell another of services provided by a particular criminal entrepreneur, and then also offer to “vouch” for him. Further, the grapevine and third-party referral may work in tandem, as when an established burglar hears through the grapevine about a particular fence and checks it out with a trusted associate before initiating contact. Or, the burglar may have a fellow thief recommend him to the fence.

Third-party referral is more than a one-way process in which one party acts as an intermediary for the other. Seasoned offenders will come to know a variety of “contact-men” whose assistance they solicit on an impromptu basis to make a timely connection. Almost anyone can be a contact-man, but they frequently are drawn from the ranks of lawyers, late night bar and night club operators, fences, and local organized-crime members.

Importantly, establishing contacts by way of referral or recommendation increases trust and confidence among parties as compared to contacts through grapevine information. Moreover, the referral process tends to be an outgrowth of friendship networks and business or work associations. By contrast, the street grapevine derives mainly from peer relations and involvement in specific criminal subcultures.

Sponsorship

Closely allied and overlapping third-party referral or being recommended is having “sponsors” who actively vouch for and make connections on one’s behalf. We see this in previous chapters, for example, in how Louie, Scottie, and Woody proactively introduced Sam to a variety of contacts. In return, the sponsor may expect payment in kind such as a kickback or a share of the profits, or the favor may have to be returned in some other way. (Relatedly, see our discussion of patron-client transactions among criminal entrepreneurs in Chapter 15.) The significance of sponsorship will depend on one’s longevity and visibility within the local underworld. By comparison to “locals” or established criminal entrepreneurs, newcomers or “outsiders” cannot rely on childhood friendships, kinship, or ties with the local “clique” or syndicate as a source of contacts.

Recruitment

The process of making contacts also involves the criminal entrepreneur’s active role in developing and sustaining connections. He must “work” his environment by encouraging and soliciting referrals and sponsorships, and by personally hustling and recruiting associates. We see this throughout Sam’s narratives, for example, in how he subtly “worked” and cultivated auction contacts, truck drivers, warehouse people, business buyers, and others. The recruiting process may be a spinoff of largely accidental or fortuitous encounters; a result of going to the “right” places for prospective associates or partners; an outcome of checking out someone known or suspected of being a little shady; or a consequence of “opening up” people not necessarily linked to the theft subculture and baiting them to defraud or steal. Successful recruiting is enhanced by a reputation for being “solid” and a “talking ability” that minimizes risks and moral concerns among those being recruited.

There is considerable overlap among making word of mouth contacts, third-party referral, and sponsorship—each in practice may blend into the other. The emphasis for word-of-mouth networking is on the process whereby a would-be thief or associate hears about a particular criminal entrepreneur and seeks him out. In referral, someone already linked to the entrepreneur sends him an associate, either as a favor to the criminal entrepreneur or to the associate. Sponsorship also involves third-party recommendation, but usually the sponsoring individual has a stronger tie to the criminal entrepreneur and acts on his behalf on a sustained basis.

Spokes in the Wheel

However they come about—by third-party referral or by individual active recruiting—certain contacts typically play an especially important role in fostering one’s career as a seasoned thief or a wheeling-and-dealing criminal entrepreneur. Some contacts become key “spokes in the wheel” to use Sam’s metaphor—designating someone who has helped in a major way to overcome the obstacles (e.g., legal, economic, technical) associated with a particular criminal specialty or illicit business. Probably more so than in legitimate occupations, one or a few “spokes” can strongly shape a criminal career. Examples of crucial spokes in Sam’s American City wheel were Jesse, Louie, Angelo, Rosen, “Fat Charlie,” Woody, and Cooper. As described in later narratives, key spokes in Sam’s diminished Tylersville wheel included Phil, Lenny, Ollie, and Rosen.

Contact-Making Differences Across Offender Types

The hardest thing is getting the connections, ‘cause [to be a dealer] you have to have the con-tacts with all different kinds of people.

—Sam Goodman, in The Fence

The description so far has been on the general processes by which offenders develop contacts. The processes that come into play, in certain ways, will depend on the type of thief or illicit entrepreneur, and on who is connecting with whom. The paths bringing offenders together will vary both between and across ordinary thieves, seasoned offenders, fences, racketeers, and quasi-legitimate businessmen.

When thieves seek to locate fences, for example, some learn about fences through word of mouth and the underworld grapevine. Others through a third-party referral—perhaps from a thief-associate, a drug dealer, or another illicit entrepreneur. Still other thieves discover fences by checking out “suspect” businesses to see if the proprietor will buy suspect goods.

Drag addicts and less established thieves rely heavily on street talk and contacts, whereas good thieves and more seasoned offenders view the street grapevine as unreliable and also prefer not to associate with dopers and “penny-ante thieves.” Instead, seasoned thieves are likely to connect with a reliable fence through another established thief, another dealer who cannot handle the merchandise the thief is bringing (for example, see the account of how Rocky, a key burglar in Sam’s network, was introduced to Sam by way of Louie, in The Fence:168), or perhaps a lawyer, quasi-legitimate businessman, or member of the local syndicate.

While the paths leading criminal and employee thieves to dealers in stolen goods overlap, there also are some differences. Track drivers and warehouse thieves are less aware of the underworld grapevine and of ways to locate a fence. Moreover, because their stealing is usually an individual rather than a group activity, they are less likely to spread the word to fellow employees than is the case with full-time thieves. Also,

Since the theft activities of employee thieves tend to be sporadic and their theft careers short-lived, there is rapid turnover among them. As a result, the self-generating effects of word of mouth and third party referral are less operative among employee than among criminal thieves. This also means that, more so than with full-time thieves, a more sustained recruiting stance is required of the fence if he intends to maintain a steady supply of driver and employee thieves as suppliers of stolen goods. (The Fence:168)

Initially attracting thieves is somewhat fortuitous and partly beyond the fence’s control, but maintaining the connection is a matter he can considerably influence.

The two processes obviously intertwine in that satisfied thieves are a major adver-tisement for attracting other thieves. And factors like trust, money, and camaraderie which contribute greatly to recruiting thieves in the first instance are at the core of sustaining their patronage, (ibid.: 170)

As Sam’s previous two narratives show (Chapters 6 and 8), a fence may offer a number of incentives to encourage thieves to keep doing business with him, especially in comparison with some of his competitors. These incentives include:

paying a reasonably decent price for stolen merchandise, at least in the thief’s eye

paying cash immediately for what is purchased

being a dependable outlet for the thief s merchandise

being conveniently located

offering advice on thievery and the criminal justice system

being a “nice” guy who is amusing and generous; and

providing perks such as bail money, a temporary job to satisfy parole requirements, or a short-term loan.

Together, these foster feelings of loyalty and reciprocity in the thief and incline him to avoid the risk of “shopping around.” However, the perks will be mainly effective with in-between and younger thieves, who are more easily swayed by extra services and a friendly atmosphere. Older, more established thieves are more influenced by profit and safety.

The fence’s contacts, of course, must extend beyond thieves and other suppliers of stolen goods to include buyers or purchasers of goods bought by the fence. As with thieves, word of mouth and third-party recommendations are important paths for connections between merchants, wholesalers, and other business buyers and large-scale fences. More so than with thieves, however, the fence is likely to seek and recruit business buyers, although in some instances a merchant may seek a known fence and let him know what his needs are.

However they develop, the recruitment and the contacts are likely to be an outgrowth of the fence’s legitimate business activities, particularly when the stolen merchandise matches his legitimate product line. This match provides both him and the would-be buyer with a cover for, as well as an “opening” for, illicit trade relations. As Klockars (1974:174) notes, a fencing operation may need as few as a “dozen different businesses” as buyers to be profitable.

In general, the grapevine linking merchants and other business buyers to dealers in stolen goods is much less self-generating than that among thieves— although similar snowballing effects may exist among some types of merchants such as antique dealers, private collectors, secondhand dealers, and auction houses. The latter frequently will meet at common meeting places. They also share with fences a “larcenous heart” and a readiness to buy or trade stolen goods “no questions asked.” Not surprisingly, fences who themselves (e.g., Sam) are antique or secondhand dealers will find it easier to develop contacts among them than among ordinary merchants. It is worth noting here, moreover, that almost any thief or part-time criminal receiver can, as some certainly do, sell stolen merchandise at flea markets, auctions, and similar “open trade” settings. But to do so regularly and in volume requires contacts with key individuals associated with these operations.

Complicit contacts between illicit entrepreneurs and law enforcement officials require a special trust and loyalty. These contacts occur in several main ways: through prior friendships linked to work or leisure activities; through association with the local syndicate; through well-connected attorneys; and through the active “grassing” (offering bribes or deals) of some police or court officials. Association with local “racketeers” or syndicate group may be particularly important, since it signals that one is safe to do business with. Where the latter practice is prevalent, it also suggests a broader political and legal corruption in which some individuals, but not others, receive special treatment. “The officials not only accept but sometimes solicit ‘favors’ from illicit entrepreneurs if they can do so safely. In some ways, it isn’t so much that the criminal entrepreneur has corrupted local officials as that he has become part of the group able to corrupt them” (The Fence:180).

Networkings “Building a Spider Web”

Criminal networks, like conventional ones, are forms of social organization made up of actors who pursue exchange relations with one another of varying duration (Podolny and Page 1998), though unlike conventional networks, they lack a legitimate organizational authority to arbitrate and resolve disputes that may arise during exchange. We would also note that the ability to operate effectively in a network (what Sam called his “spider web”) is a skill that must be learned. As Podolny and Page argue, “the ability to exploit the substantive knowledge gained through network relationships without killing the proverbial goose can be viewed as an important capability in its own right” (ibid.:72).

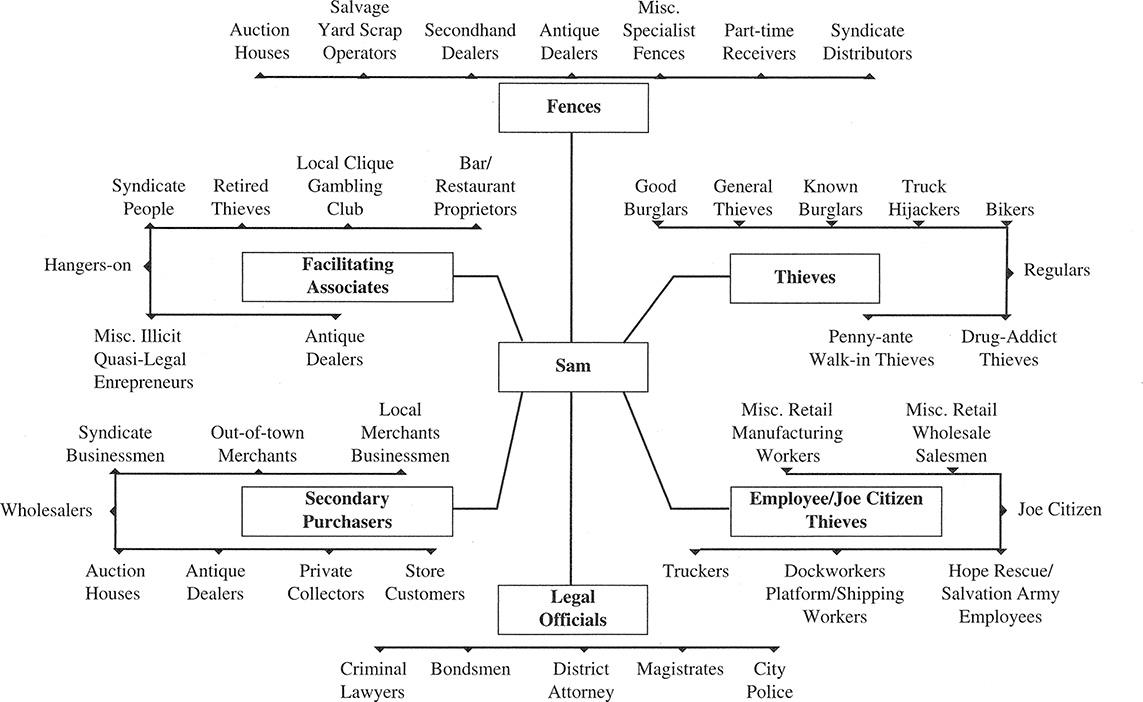

The network map in Figure 9.1 depicts the varied individuals linked to Sam’s trade in stolen goods during his peak fencing period (i.e., in the early 1970s prior to his incarceration for “receiving stolen property”).

The map suggests both the importance of the fence’s reputation and the need for contacts in maintaining his career. As characterizes the underworld more generally, Sam’s contacts derive from mutually beneficial exchanges with persons who “trust” each other and whose skills and resources are mutually supportive. The exchanges also often depend on the compatibility of the individuals involved, especially when they develop into relatively stable arrangements or partnerships. Typically, the trust and the connection is based on a preexisting tie or develops through the mediation of a third party who introduces the participants and vouches for their reliability.

Figure 9.1

Sam’s Fencing Network*

Earlier, we noted the divergent views in the criminological literature about the talents and attributes of criminals and career thieves, including professional thieves and illegal entrepreneurs. One view emphasizes the skills and attributes of professionalism that characterize at least some categories of career thieves and criminals (Sutherland 1937, 1940). The other common view is that criminals are fundamentally unskilled, unintelligent, inept, and/or lacking in self-control (see Gottfredson and Hirschi 1990; Bennett et al. 1996). Sam’s narratives, and our discussion above, have suggested that a number of skills and character attributes are crucial for successful property crime and criminal entrepreneur ship.

Furthermore, network relationships and social bonds between thieves, fences, and other criminal entrepreneurs are not necessarily “cold and brittle” (Korn-hauser 1978). While we do not view such relationships through rose-colored glasses, it is clear that trust, reliability, and reciprocity, at least within one’s own group, appear to be crucial for sustainable burglary, fencing, and other forms of criminal entrepreneurship. In turn, as we elaborate in Chapter 11, network relationships and social bonds in the work of burglary and fencing appear to be held together by a variety of structural, personal, and/or moral commitments.

Such networking brings several advantages for sustained criminal enterprise. First, networks are not coercive; participants are willing members who choose to associate with each other. This is in contrast to some other kinds of work-related or business relationships in the legitimate world, which may be more constrained in that one’s coworkers and business associates are often chosen for him or her, or dictated by circumstance. Voluntary network associations may in turn facilitate easier exchanges of information and assistance.

Second, the mutual selection process in voluntary network associations makes it more likely that participants will be (or become) comfortable with one another’s work habits, work styles, commitments, and culture. This feature of networks, in turn, provides opportunities for long-term bonds and mutual respect.

Last, we propose that the size and diversity of one’s criminal network or “spider web” is an important marker of underworld status. In a manner similar to one’s prior criminal record, the nature and extent of one’s criminal ties is also an indicator of the “seriousness” of one’s criminal career.

As Sam’s narrative and our commentary strongly demonstrate, networks, as well as other forms of criminal social and cultural capital, matter a great deal for sustained criminal enterprise and for pulling off more lucrative and more organized kinds of crime. A successful criminal enterprise of more than minimal size or longevity is simply not possible without making and maintaining contacts. We believe this fact is insufficiently recognized by many criminolo» gists today. Understanding criminal networks and the activity necessary to build and sustain them is a significant gap in the criminological literature, and Confessions helps to fill that gap. Furthermore, a variety of criminal and conventional business skills, as well as leaerned habits and ways of perceiving one’s world, also contribute to success and longevity in fencing, and likely other forms of criminal enterprise as well.