CHAPTER 4

Slow Food for Cultural Survival

Slow Food is a movement that began in Italy in 1986. It was sparked by the outrage of an Italian journalist, Carlo Petrini, at the opening of a McDonald’s at Rome’s landmark Spanish Steps. The movement originally defined itself by its opposition to fast food. “A firm defense of quiet material pleasure is the only way to oppose the universal folly of Fast Life,” states the 1989 Slow Food Manifesto.1

Slow Food struck a chord and has since developed into a worldwide organization with eighty thousand members in 800 local “convivia” or chapters, 150 of them in the United States. I’ve made presentations to several of these groups; after all, food doesn’t get any slower than fermentation. Many of these groups host regular tasting events. The Slow Food group that I spoke with in Atlanta had recently held a tasting of different salts from around the world. To a food geek like me, that sounds really interesting and fun.

“Taste is a part of knowledge,” says Petrini,2 and taste education is one of the goals of Slow Food. One manifestation of taste education, and the firm defense of quiet material pleasure, is connoisseurship. Unfortunately, too much emphasis on buying fancy foods becomes highbrow consumerism, a costly pursuit of the very finest foods and wines that is disconnected from questions of sustainable production and far beyond the means of ordinary people. Some critics have dismissed Slow Food as elitist. Indeed, that is a reasonable critique of any organization that charges a $60 annual membership fee and typically sponsors events at expensive restaurants. To be fair, some Slow Food convivia organize mostly free, potluck events. But then $500 is the going rate for attending a dinner with Petrini himself, “A Rare Opportunity to Talk (and Eat) with Slow Food’s Founder.”3

Yet Petrini’s rhetoric and many of the projects that Slow Food has undertaken around the world suggest an agenda beyond fine dining. “Saving gastronomy is not possible if we cannot save the very context in which it is developed,” Petrini says. “The challenge ahead is to reconnect the umbilical cord of traditional knowledge that once joined man and nature and has almost been severed by industrialization.”4

Accordingly, Slow Food has championed traditional local food production. It has focused on issues of biodiversity, both at the level of preserving heirloom breeds of plants and animals in the face of homogenization and extinctions and in terms of the cultural diversity that homogenized agricultural practices threaten. Without an emphasis on supporting small-scale food producers, warns Petrini, “we all become top-class gourmets and connoisseurs of rare delicacies while ignoring the need to prevent the disappearance of those who actually work the land and supply the products.”5

In 2004 Slow Food organized an unprecedented gathering of small-scale food producers from around the world. Of course these are people with limited budgets for international travel, so this coming together was facilitated by the largesse of the Italian government (promoting food tourism) and augmented by the fund-raising efforts of Slow Food convivia worldwide. The gathering, known as Terra Madre (“Mother Earth”), brought together more than five thousand small-scale food producers—farmers, bakers, brewers, and other food processors using traditional methods at a community-based scale—from 130 countries! These producers represent what Petrini calls “food communities,” which “bind together the destinies of women and men pledged to defending their own traditions, cultures and crops.”6

“Terra Madre changed the essence of Slow Food,” reflects Petrini.7 “It became evident that if we want to properly develop actions of defense, support and service, it is essential to start looking at food communities with a much broader and more complex perspective than we have to date.”8 Vandana Shiva, one of the Terra Madre keynote speakers, calls this Terra Madre perspective “earth democracy,” which “implies having both a planetary consciousness and a local embeddedness of how we produce and consume, and how we experience our identity and sense of self.”9

Shortly after Terra Madre, I attended a presentation at the Carolina Farm Stewardship Association given by several farmers who had gone to Italy for the gathering. They all had come home feeling inspired by people they had met at Terra Madre. “There are people all over the world doing what we’re doing here,” reported farmer Libby Outlaw. For people doing the most localized of work there is—working particular land to grow food—this is needed affirmation and encouragement. After experiencing the solidarity of food producers from all over the world, farmer Emile DeFelice saw “movement potential.” The movement he envisions is a coming together of small-scale food producers and “food communities,” empowered by numbers, unity, and solidarity, keeping traditions alive in the face of global homogenization and expanding corporate concentration of the food chain.

A huge sign on the wall at Terra Madre read, “Today thirty plants feed 95 percent of the world’s population. In the past one hundred years, 250,000 plant varieties have gone extinct, and one plant variety disappears every six hours. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, Europe has lost more than 75 percent of its agricultural variety, while the United States has lost 93 percent of its crop diversity. One third of native cattle, sheep, and pig breeds have gone extinct or are on the road to extinction.”

We’ve already touched upon this issue in chapter 2 in the discussion of the disappearance of heirloom vegetable varieties, ones that evolved over time through selection by farmers and are thereby adapted to local conditions. “Improved” varieties developed by scientists in university and corporate laboratories—not adapted to local conditions—have largely replaced traditional heirloom varieties, along with the habit and practice of seed saving. Most traditional varieties listed in seed catalogs a century ago are forever lost. The plant varieties, the seed-saving practices, the farmers themselves, and their roles in their communities—all of these are manifestations of the loss of diversity, with loss of biological diversity reflecting loss of cultural diversity, and vice versa. The globalization and homogenization of food diminishes diversity on all these levels, and only by reconnecting with traditions of food production can we reclaim and reestablish practices that support and rebuild both biological and cultural diversity.

One Slow Food project is the Ark of Taste, which lists foods—either from specific breeds or made through specific processes—that are perceived to be in some danger of extinction. In most cases potential food extinctions are due to disuse and neglect. For instance, the pawpaw (Asimina triloba), a custardlike fruit that grows on a tree of the same name native to the eastern United States, is the largest fruit indigenous to the United States. The thick, sweet flesh of the fruits is compellingly delicious, yet the pawpaw is bizarrely obscure today. Pawpaws and other native “first fruits” suffered as the indigenous tribes of the eastern United States were forced to move westward without their orchards.

Pawpaw trees are still part of the landscape in the Southeast and Midwest. We enjoy pawpaws here in Tennessee every fall. The ripest pawpaws are found on the ground and are intensely sweet, with a rich, complex flavor and a gorgeous, creamy texture that melts in your mouth. My friend Hector Black sells some pawpaws at his stand at the Cookeville, Tennessee, farmers’ market, but on an extremely small scale. USA Today reported on a California pawpaw grower who sells the fruits at one of San Francisco’s premier farmers’ markets:

Pawpaw. ©Bobbi Angell. Used by permission.

Even there, at a market known as a magnet for serious foodies and chefs who welcome the most obscure fruits and vegetables, customers puzzle over the mottled green-brown fruits the size of small mangos. When he can get them to actually taste the pawpaws, they’re hooked. A quick cut to one end, a squeeze of the creamy, custardy flesh straight into the mouth and customers lap up the explosion of flavors that are reminiscent of banana, papaya, coconut, cream and even hints of caramel in the ripest. But five minutes of explanation for each sale isn’t the way to move a harvest’s worth of fruit.10

Slow Food’s Washington, DC, convivium is spearheading a “Three Sweet Sisters” campaign to generate renewed interest in pawpaws, along with two other neglected indigenous fruits, native persimmons and wild strawberries. The Three Sweet Sisters project has sponsored tasting events, Three Sweet Sisters Gardens (including one at the National Arboretum), and Restaurant Dialogues, sessions that encourage chefs to incorporate these fruits into their menus.

It is not only plant varieties that face potential extinction. According to animal geneticist John Hodges, 45 percent of existing chicken breeds, 43 percent of horse breeds, 23 percent of pig breeds, and 23 percent of cattle breeds are at risk of extinction.11 As one example, turkeys have been bred to be so grotesquely large-breasted that the single breed (Broad Breasted White) that constitutes more than 99 percent of the commercial market in the United States can no longer accomplish reproduction without human intervention.12 Bigger is not always better!

An organization called the American Livestock Breed Conservancy (ALBC) is working to preserve traditional breeds of farm animals, which, like seeds, have historically been bred to adapt to varied local conditions. Heritage farm animals have largely been replaced by “improved” breeds with the generic appeal of producing more meat (or milk or eggs) more quickly, though the resulting animals are often less healthy, less fertile, and less able to thrive on pasture and thereby require more inputs (such as water, feed, reproductive assistance, or antibiotics). The ALBC has helped to bring back from the brink of extinction a number of heritage farm-animal breeds, most notably turkeys; traditional American breeds such as the Standard Bronze and Narragansett are making a comeback. The ALBC provides information and technical resources to breeders and farmers and works with Slow Food to develop markets for heritage breeds.

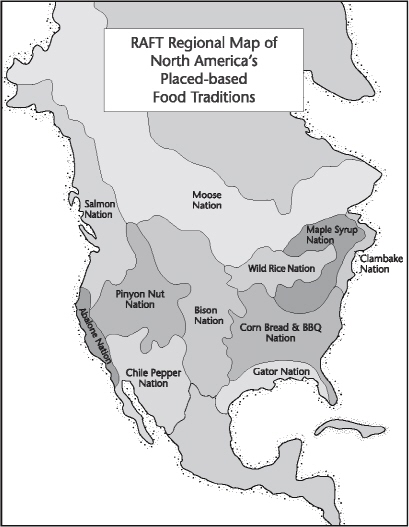

Slow Food is collaborating with the ALBC and several other organizations, including the Seed Savers Exchange and Native Seeds/SEARCH, in a project called Renewing America’s Food Traditions (RAFT). RAFT has begun holding regional events to celebrate regional foods, to brainstorm lists of regionally distinctive foods, plants, and animals, and to determine which species are abundant, threatened, endangered, extinct, or recovering. The first workshop, in the “Salmon Nation” of the Pacific Northwest, came up with a list of 180 regional foods, two-thirds of which are at risk. Workshops in the other regions will be held over the next several years, contributing to the RAFT “Redlist” of endangered foods and creating “tangible tools of eco-gastronomic conservation.”13

Traditional foods can be saved not by preaching ideology, insists Petrini, but only by reviving pleasure:

The beginning of the organic movement had a mistaken attitude because it didn’t place any emphasis on pleasure. It was an ideological, almost religious approach. It ignored pleasure. Pleasure is not antithetical to health, pleasure is not the enemy of sustainability. Pleasure is moderation and with moderation we can be sustainable. An environmentalist or an organic farmer that is not also cultivating pleasure is just out of this world. Throughout history, all of humanity has always wanted to produce food also to produce pleasure. . . . This idea is part of the complexity of a new gastronomy. We can’t change the world by just preaching boring messages. We have to re-discover the value of taste and understand that at its root, taste is connected to pleasure. Taste is pleasure that reasons, or knowledge that enjoys. Nice, eh?14

Though his agenda is pleasure-based, Petrini maintains a sense of urgency: “Either we go back to local agriculture, and go back to giving pride to these farmers, having a human rapport with these farmers, or we might as well just blow our brains out.”15

©2006 Renewing America’s Food Traditions (RAFT). Used by permission.

Wild Rice and Other Indigenous-Food Culture Struggles

The previous chapter highlighted the land struggles of the Anishinaabeg people of northern Minnesota and southern Ontario. Their struggle for their land is intertwined with their ongoing struggle to continue their age-old cultural practice, specific to that very land, of harvesting, eating, and trading wild rice, which they call manoomin, “good berry.” The story the Anishinaabeg tell of their migration to this land involves a prophecy instructing them to settle “where the good berry grows on water.”16 For more generations than anyone could count, Anishinaabeg people have enjoyed the delicious and nutritious good berries of the northern lakes. “Our rice tastes like a lake,” says Anishinaabeg activist Winona LaDuke.17 The annual harvest is a time-honored community ritual.

It is Manoominike-Giizis, the wild rice moon, and the lakes teem with a harvest and a way of life. “Ever since I was bitty, I’ve been ricing,” reminisces Spud Fineday, of Ice Cracking Lake. Spud rices at Cabin Point, and then moves to Big Flat Lake, lakes on Minnesota’s White Earth Reservation. “Sometimes we can knock four to five hundred pounds a day,” he says, explaining that he alternates the jobs of “poling and knocking” with his wife, Tater, a.k.a. Vanessa Fineday. The Finedays, like many other Anishinaabeg from White Earth, and other reservations in the region, continue to rice, to feed their families, to “buy school clothes and fix cars,” and get ready for the ever returning winter. The wild rice harvest of the Anishinaabeg not only feeds the body; it feeds the soul, continuing a tradition that is generations old for these people of the lakes and rivers of the north. . . . It is a community event, a cultural event, which ties the community intergenerationally to all that is essentially Anishinaabeg, Ojibwe.18

Unfortunately the annual Anishinaabeg rice harvest is threatened by the pursuit of biotechnological innovation, without regard for the integrity of either indigenous plants’ genetic identity or indigenous peoples’ cultural identity.

Wild rice offers us another example of biopiracy. Early in the twentieth century anthropologists from the University of Minnesota studied the Anishinaabeg and determined that “wild rice, which has led to their advance thus far, held them back from further progress, unless, indeed, they left it behind them, for with them it was incapable of intensive cultivation.”19 Intensive cultivation—growing more on less space, so the land’s productivity is intensified—is understood to be progress and traditional seasonal gathering as backward! So university plant breeders set out to improve wild rice, and in the 1950s and 1960s they developed a domesticated, paddy-grown “wild” rice.

The genetic material they started with and manipulated came from native wild rice, of course; the researchers felt free to avail themselves of this as a public resource, even though native peoples’ rights to the rice have been repeatedly recognized by treaties. As a result of this breeding effort, a domesticated “wild” rice industry developed in Minnesota, and wild rice was officially declared the state grain. As the industry grew it shifted to California, where the damaging hail and winds common in Minnesota could be avoided. “Wild” rice prices plummeted, from $4.44 per pound in 1967 to $2.68 per pound in 1976.20 The Anishinaabeg and other peoples of the northern waters, who until then had been the sole sources of wild rice, felt the impact of domestication.

Thirty years later public funds continue to be channeled into breeding for the domesticated “wild” rice industry. The University of Minnesota continues to fund studies with titles like “Molecular Cytogenics for Plant Improvement, Wild Rice Breeding/Germplasm, and Toward the Identification of Functional Genes in Wild Rice.” The Anishinaabeg, who have always harvested wild rice from Minnesota’s lakes—and whose livelihoods have already been diminished by the crop “improvements”—worry that new, genetically modified varieties will contaminate the indigenous wild rice. For them, the increasingly sophisticated genetic technology is not value-neutral science at all; it diminishes their culture. A coalition of northern Minnesota Anishinaabeg bands has demanded that the University of Minnesota declare a moratorium on genetic research on wild rice.

In addition to challenging the biopiracy of their resources and restoring their land base, LaDuke and her fellow Anishinaabeg activists are actively working to reintegrate traditional foods into the contemporary lives of their people. Their organization, the White Earth Land Recovery Project (WELRP), is promoting food sovereignty as a means of cultural survival through several related projects: encouraging rice harvesting as a source of both food and income; actively marketing wild rice online and through networks like Slow Food; encouraging other food production on the reservation; and combating an epidemic of diabetes by distributing traditional foods to diabetics and their families. In 2003 LaDuke and White Earth elder Margaret Smith were recognized for their efforts with an International Slow Food Award for the Defense of Biodiversity. More importantly, their work is taking hold and changing Anishinaabeg peoples’ lives.

The program to bring traditional foods to diabetics is called Mino-Miijim (“Good Food”). Native Americans have the highest prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the world. A third of the residents of the White Earth Reservation are diabetic, as is an estimated 40 percent of Native Americans over the age of forty nationwide.21 According to the WELRP Web site:

The process of colonization effected a dramatic change in patterns of exercise and diet. The forced adaptation of a sedentary lifestyle and the subsequent increase in obesity rates facilitated the spread of diabetes, heart disease, and other related health complications. In addition, the switch from a traditional diet, which was high in dietary fiber and lean sources of protein (wild game), to a diet rich in sugars, refined carbohydrates, and fats has fueled the diabetes epidemic.22

Many of the Anishinaabeg rely upon highly processed government-issue commodity foods. “Ironically nearly all the foods the government issued to the tribes were less nutritious and more fattening than their native foods,” says Gary Paul Nabhan, an Arizona ecologist, writer, and food activist who founded the organization Native Seeds/SEARCH.23 “It seems as though it is the poorest among us who most desperately need such traditional foods to regain their health, for they are otherwise treated as the dumping grounds for the worst of junk foods.”24 In other words, everybody needs “slow food”—not just food adventurers with disposable income.

Margaret Smith, an elderly diabetic Anishinaabeg herself, decided to assemble monthly care packages of Anishinaabeg foods—foods such as wild rice, hominy corn, and buffalo meat (bought from other reservations)—and distribute them to other diabetic Anishinaabeg elders on the reservation. Smith visits with the elders and encourages them to share the native foods with young people. WELRP sends elders into schools to introduce native foods, advocates for native-food-based school lunch programs, and teaches people to grow the traditional American “three sisters” companions of corn, beans, and squash. WELRP recognizes food sovereignty as an integral element of land sovereignty and healthy lives and seeks, on many fronts simultaneously, to reintegrate traditional food production into the lives of the Anishinaabeg people.

In the Sonoran Desert of Arizona and Mexico, Gary Paul Nabhan organized the Desert Walk for Biodiversity, Heritage, and Health, a twelve-day, 220-mile, multicultural trek through the desert intended to create awareness of the relationship between diet and diabetes. Among the participants were more than twenty Native Americans with diabetes from the Seri, Pima, and O’odham peoples. According to Nabhan, the O’odham have the highest diabetes rate of any ethnic group in the world.25 The walkers learned about indigenous foods from communities along the way, feasting on meals including venison, rabbit, birds, tomatillos, squash, pumpkins, tepary beans, mesquite, lamb’s-quarters, purslane, mustards, cress, ocotillo blossoms, prickly pear and other cacti, mistletoe, pinole, chia seeds, and mescal.

One of the ways in which these traditional foods contrast with the high-fat, high-sugar, highly processed standard American diet is that their nutrients are metabolized much more slowly (which gives us another perspective on the concept of slow food). “Traditional diets of desert peoples formerly protected them from diabetes and other life-threatening afflictions,” writes Nabhan.26 He and the other walkers were able to dramatically experience the physiological differences that a diet of native foods can produce.

These foods enabled us to hike across rugged terrain for ten hours a day, followed by another hour or two of celebratory dancing. Our collective effort made us more deeply aware that our own energy levels could be sustained for hours by slow-release foods. . . . A return to a more traditional diet of their ancestral foods was not merely some trip to fantasy land for nostalgia’s sake; it provided them with a deep motivation for improving their own health.27

Native Americans in many different places are organizing around traditional foods as a strategy for survival. Patricia Cochran, an Inupiat from northwestern Alaska near the Bering Strait, directs an organization called the Alaska Native Science Commission, which promotes cultural survival via environmental protection and health advocacy. Inupiat people eat mostly fish and sea mammals. Among their traditional delicacies are stinkfish, which are fish that are buried in the tundra to ferment, and muktuk, or whale blubber. New York Times critic Frank Bruni traveled to Alaska and wrote about sampling muktuk: “I did as told: grabbed the hide and bit into the blubber. It tasted like a wedge of solid rubber that had spent several months marinating in rancid fish oil. And it flew instantaneously from my mouth into a thicket of nearby birch trees.”28 Then the big-city critic watched a ten-month-old baby as he “gummed and licked that slimy whale fat as if it were Alaska’s biggest, brightest lollipop,” concluding that “a palate, like a mind, works better with exposure and education and is a product of its environment.”29

Both the food itself and the taste for it are products of their environment. This is exactly why globalized food makes no sense. Each ecological niche has its own unique abundance to offer. Different regions offer different sources of abundance. Human beings have been remarkably adaptable in terms of diet. What we eat has historically been central to what defines our culture. Though their traditional diet made the Inupiat and other peoples of the Arctic among the healthiest on the earth, today atmospheric and oceanic currents are now known to carry chemicals and emissions from the rest of the world and concentrate them there. “The Arctic has been transformed into the planet’s chemical trash can, the final destination for toxic waste that originates thousands of miles away,” writes Marla Cone in Mother Jones.30 PCBs, DDT, mercury, lead, and other dangerous chemicals are present in Arctic fish, and in the breast milk and umbilical cords of Arctic mothers, at alarming levels.

Some might conclude that the Inupiat people should abandon their traditional fish-based diet. But the food of any culture is more than a collection of nutrients; it is a central element of identity. Says Cochran:

How we get our food is intrinsic to our culture. It’s how we pass on our values and knowledge to our young. When you go out with your aunts and uncles to hunt or to gather, you learn to smell the air, watch the wind, understand the way ice moves, know the land. You get to know where to pick which plant and what animal to take. It’s part, too, of your development as a person. You share food with your community. You show respect to your elders by offering them the first catch. You give thanks to the animal that gave up its life for your sustenance. So you get all the physical activity of harvesting your own food, all the social activity of sharing and preparing it, and all the spiritual aspects as well. You certainly don’t get all that, do you, when you buy prepackaged food from a store.31

The Makah, a Washington State tribe that traditionally subsisted largely on the meat of the gray whale, made an attempt a few years ago to revive their food tradition. The gray whale is so central to their culture that in an 1855 treaty with the United States, the Makah traded 90 percent of their land for the right to continue whaling. As the commercial whaling industry grew, the Makah watched whale populations dwindle. In the 1920s they made the voluntary decision to stop whaling altogether, fifty years before the gray whale became legally protected as an endangered species. An international moratorium on commercial whaling, in place since 1986, has been effective enough that gray whale populations have rebounded, and in 1994 it was removed from the endangered species list. Because of that 1855 treaty, and the fact that they do not hunt for commercial purposes, the Makah are at least theoretically exempt from the commercial whaling ban. They decided to resume tradition, and after a rigorous training program, in 1999 a group of Makah went out hunting into the sea and brought home the first whale in nearly eighty years. “The biggest thrill of my life was to feed fresh whale to my grandson,” said a Makah woman in the television documentary The Meaning of Food. Some misguided environmentalists and animal-rights activists protested the Makah whale hunt with slogans such as “Abolish the treaties!” and “Save a Whale—Hunt a Makah!” In 2000 a federal court ordered the Makah to stop whale hunting, treaty or no treaty, extinction threat or not, preventing them from practicing their ancient food traditions in a sustainable way.

Other cultures in the Pacific Northwest are connected to salmon. However, dams, irrigation projects, and development have ruined most rivers for salmon spawning, and in 2004 the Bush administration scaled back by 80 percent protected salmon habitats.32 Cultures organized around salmon are struggling to survive. Susana Santos, one of the few remaining members of the Tygh band of the Lower Deschutes River in Oregon, has watched the demise of the salmon that have traditionally sustained and coexisted with her people.

I wanted to dance the salmon, know the salmon, say goodbye to the salmon. Now I am looking at the completion of destruction, from the Exxon Valdez to . . . those dams. . . . Seventeen fish came down the river last year. None this year. The people are the salmon, and the salmon are the people. How do you quantify that?”33

Food is an integral aspect of movements for environmental justice. The Karuk of the Klamath River Valley in northern California are another native people whose diet centered around wild salmon. Since the destruction of salmon spawning in the Klamath in the 1970s, the Karuk diet has become dominated by processed foods; as is the case for other native peoples abruptly cut off from their traditional foods, obesity and diabetes rates have steadily risen in the Karuk population. As the dams come up for relicensing by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the Karuk are asserting that their health crises have been caused by the destruction of salmon habitat on the Klamath, and that at least three dams on the Klamath River should be knocked down.34

On the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, a group called Village Earth is helping Oglala Lakota people get their land back from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which leases roughly 60 percent of the land allotted to the Oglala Lakota in the 1887 General Allotment Act to cattle ranchers for as little as $3 a year per acre. Village Earth is providing new Oglala Lakota settlers with various forms of assistance toward living sustainably on the land, among them “seed herds” of buffalo. The project is an effort to restore the buffalo and the people to their land, and to promote the interaction of the two. “Home, though, is a bit different than it used to be,” reports the Village Earth Web site. “Despite the promising movement toward land restoration, Pine Ridge landowners still are required to fence in their land or it will be immediately revoked again.”35

Two hundred years ago forty to fifty million buffalo roamed the northern plains. In the early nineteenth century buffalo extermination was federal policy, a means of wiping out one way of life and opening up space for the establishment of a new one—with profitable railroads and cattle ranching. “Forty-five and a half million cattle live in this same ecosystem now, but they lack the adaptability of the buffalo,” writes Winona LaDuke. The cattle require extensive infrastructure to support them. “The prairies today are teeming with pumps, irrigation systems, combines, and chemical additives. Much of the original ecosystem has been destroyed.”36

Many different projects that share the goal of restoring buffalo herds to the northern plains are under way. Forty-two tribes are collaborating on buffalo restoration and marketing efforts as the Intertribal Bison Cooperative, and the World Wildlife Fund and the American Prairie Foundation have started a buffalo restoration project on a 32,000-acre wildlife preserve in Montana. These projects are steps toward the larger goal of restoring the buffalo commons and, more broadly, healing the ecosystem and restoring the balance between people and buffalo on this land. “When we talk about restoring buffalo, we’re not just talking about restoring animals to the land,” says Fred Dubray of the Cheyenne River Nation, executive director of the Intertribal Bison Cooperative, “we’re talking about restoring social structure, culture, and even our political structure.”37 As we discussed in chapter 3, the United States has a long tradition of ignoring tribal land claims. Supporting a revival of native food traditions means supporting a return of native lands.

People, communities, and cultures suffer when they are cut off from the sources that have always sustained them. People can change and adapt, certainly, but abrupt change is profoundly destabilizing and debilitating. Food and drink, and the methods of their production, are integral elements of culture. For transplanted cultures as well as indigenous peoples, strategies for cultural survival must incorporate food, in both its consumption and its production. This does not mean that we must all be slaves to tradition. Traditions change, slowly but surely; they evolve, adapt, and influence other traditions. But even so, traditions are vitally important, for they embody accumulated cultural knowledge. “We’ve got to defend ancient wisdom,” exhorts Carlo Petrini. “It’s not a retrograde battle, it’s an avant-garde battle, because we find for ourselves so much richness inside this traditional wisdom.”38

Illegal Food: The War on Small-Scale Production

Many traditional foods and methods of food production have been prohibited by laws imposed in the name of hygiene. My current favorite example of an outlawed food is the Italian cheese called casu marzu, a traditional product of the island of Sardinia. Casu marzu is made from pecorino, an Italian sheep’s milk cheese, that is left out in the sun. Flies land on the cheese and lay eggs, which hatch into maggots that digest the hard, mild pecorino into casu marzu, “a viscous, pungent goo that burns the tongue,” according to the Wall Street Journal.39 Saveur also featured a vivid account of tasting casu marzu: “We happened to be in a light-filled room as we prepared to taste it, and the maggots started jumping around like crazy and landing everywhere, including on us.”40 As you eat casu marzu, you must cover your eyes with a hand to protect them from jumping maggots.

I’ve told many fermentation-enthused audiences about this sensational cheese, and it never fails to get people to cringe in horror. In my fermentation practice I’ve periodically encountered maggots in foods I’ve been aging. Anywhere flies can land and lay eggs, maggots will develop. It’s happened to me most often on cheeses I’ve tried to age in summer. People worry about the bacteria that flies could potentially spread, but the acids in an aging cheese make it inhospitable to pathogenic bacteria (see chapter 5 for more information about this). Emboldened by reading about casu marzu, I’ve tasted a few accidentally maggoty cheeses. The cheese digested by the maggots is incredibly creamy and strong. In my observation, the maggots themselves migrate from the creamy area to fresh cheese, so I’ve ended up with mostly viscous, gooey, pungent maggot-digested cheese and not much of the squirmy maggots themselves. No maggots jumping. And whatever maggots are there blend right in.

Really, people in this world eat all sorts of things, even insects, creepy-crawly things, and molds. People eat fish that has been buried for months until it decomposes into a cheesy paste; they eat years-old eggs and decades-old hams. My friend Alan Muskat presents me with crunchy dried ants for lunch, while the Wildroots Collective in western North Carolina serves me raccoon stew and other roadkill delicacies (see Roadkill Radicals). My friend Roman, when he was a little kid, used to eat worms, centipedes, and grasshoppers, without ill effect. The more grossed-out people were, the more encouraged he felt. Notions of what is appropriate to eat are largely subjective and culturally determined. There is no objective universal boundary between food fit to eat and food that is inappropriate or “spoiled.”

People in Sardinia have been eating casu marzu for hundreds of years, apparently without ill effect. Casu marzu sells for twice the price of the maggot-free pecorino. Except that you can’t buy it any more—at least not legally. “Selling it or serving it can be punished with a hefty fine,” according to the Wall Street Journal. Evidently the E.U. bureaucrats in Brussels cringed at the thought of maggoty cheese, so they declared it illegal, not in compliance with E.U. hygienic standards. The cultural homogenization machine grinds on, saving us from corruption by eccentric cultural variations.

Of course, the tradition of casu marzu continues. People do not simply say, “Okay, we will end our inherited tradition because you say so.” People resist any new order imposed upon their culture. And so casu marzu continues to be made and eaten, though now not sold, at least not openly. The tradition now holds a different place in the culture, as a symbol of resistance against an ever-more-distant, out-of-touch, centralized authority.

Most of the traditional foods that are being made illegal are less sensational than casu marzu. The typical story is simply that small-scale production methods have effectively been outlawed by hygiene regulations that are designed for mass production. The regulatory unification of Europe has rendered all sorts of small-scale food-processing operations illegal. “The laws and regulations are endless and forever changing,” writes a German farmer I corresponded with, “but as always in favor of the ruling bunch.” A dairy farmer and cheesemaker in a small town in central Italy reports that changes in Italian food-hygiene laws, in an attempt to make them “harmonize” with E.U. regulations, have made legal farmstead cheese production there difficult and expensive.

“In Italy,” writes E., “if you want to sell ‘transformed products,’ you have to have an E.U. standard workshop for each separate product. The only thing we can legally sell is fruit and vegetables ‘just as they are picked.’ Even wine and oil are ‘transformed’ just by being bottled.” Therefore a small-scale farm can no longer use a kitchen or other general work area to make cheese for sale; the cheese must be produced in a dedicated space, used solely for the production of cheese, that meets factory production standards. This means that legal cheese production in Italy now requires heavy capitalization, beyond the reach of the average small farmer.

So E. and other small-scale food producers in her area have started an underground market.

Our market meets at a different farm each month, on a Saturday afternoon. We start at 3 p.m. in order to allow people who have animals to get back in time for milking/feeding. Most of the farms are small and “self-sufficient,” all are organic, some are biodynamic. We started the market in 2001 after a big anti-G8 protest in Genoa during which many peaceful protesters were beaten by riot police. My companion and I, together with another local couple, were trying to think what we could do to change things since protesting in public seemed so fruitless, and we decided that we should start at home, on a very local level, and behave as if life were organized as we wish it were. So we called a meeting of all the local “alternative” people we thought might be interested in exchanging the food we produce.

We sent out fifty invitations, but at the first meeting there were only eight people. Nevertheless, we decided to start a small monthly market, and at the first one we were twelve people, at the second, sixteen, at the third, twenty. Now we have done these markets once a month for four full years and we have a list of about ninety people who participate. Out of these, about twenty are producers. At any given market, there are about fifty to seventy people. We refer to the market as il mercatino, the little market, or as “the clandestine market.”

My companion, M., and I do the organizing: We send out a letter once a month to everyone on the list with a map showing how to get to the next farm. The letter also gives local news, and we include small notices and ads from participants who want to sell/buy/exchange/donate animals/land/equipment etc. Once a year, we ask everyone for money for stamps and photocopies (10 euros each). People are happy to host the market and one reason for moving it around is so that everyone can see how other people live and work. The host usually provides cake/wine/tea and the whole event has a useful and fun social side: people meet and talk and exchange advice and news. They also arrange the buying of big items like the year’s supply of hay or wheat.

This clandestine market sounds strikingly similar to the bread club described in the introduction. E. also told me about other clandestine markets she knows of in the central Italian countryside. In many variations, all of them small and informal, such underground markets are widespread, and we need to create many more of them.

Similar regulatory changes are occurring elsewhere in the world. In 1998 India banned the sale of mustard oil and imposed new packaging requirements on other oils. This action was triggered by the death of fifty people in New Delhi, caused by contaminated mustard oil with suspicious details. The mustard oil was found to be tainted with petroleum products as well as an inedible seed oil (from an Argemone species) that contained toxic alkaloids. Contamination was found to be present in many different brands and at levels as high as 30 percent. A spokesperson for the government-owned brand of mustard oil charged, “There is a strong case for sabotage.”41 Vandana Shiva agrees: “There was no other way to explain why the contamination was so extensive.”42

The Indian government announced the ban on mustard oil on the very same day that it lifted all restrictions on the importation of soy oil. Its markets were quickly flooded with imported soy oil, most of it genetically modified. Vegetable oils in India have traditionally been quite diverse and their production small-scale, localized, and informal. People in communities all around India have always extracted oil from not only mustard seeds but also coconuts, peanuts, linseed, sunflower seeds, and sesame seeds, in small cottage industries. The contrast is stark: community-based self-sufficiency and economic democracy replaced by homogenized corporate consumerism, and in the name of hygiene and “free trade.” Free trade of locally produced goods among people at the community level is outlawed, in favor of a global free trade among huge corporations. “Mustard oil and our indigenous oilseeds symbolize freedom for nature, for our farmers, our diverse food cultures and the rights of poor consumers,” says Shiva. “Soyabean oil symbolizes concentration of power and the colonization of nature, cultures, farmers and consumers.”43

It is ironic that a contamination scare led to further concentration of oil production and distribution, since centralized systems are most vulnerable to sabotage and manipulation. In the United States we have seen a growing fear of ways in which our food supply could be vulnerable to contamination as a form of terrorist attack. When Tommy Thompson, the secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, resigned in 2004, he remarked upon his surprise that the food chain had not yet been attacked: “I, for the life of me, cannot understand why the terrorists have not attacked our food supply, because it is so easy to do.”44 And in 2005 the National Academy of Sciences published (in defiance of being asked not to by the government) an exploration of a scenario in which a single gram of botulinum toxin released into the U.S. milk supply could kill fifty thousand people.45 Vulnerability exists at this scale only because the milk is processed at this scale! Decentralized local food systems provide security because they spread and dissipate the myriad food-safety risks—not only the terrorist variety, but also accidental contamination—so that even a worst-case scenario is contained and does not have as catastrophic an impact.

The scale of impact in the event of contamination is one of the reasons that it is appropriate to hold mass producers to more stringent safety standards than small-scale producers. Unfortunately, regulations justified in the name of safety often have the effect of forcing out small producers, thereby increasing reliance on centralized supplies. In 2005 India proposed a broad new food safety and standards law that Shiva calls “food fascism.” She argues that the new law would impose upon all food production uniform standards appropriate for large-scale production, even though most of the food consumed in India (like oils until 1998) is still locally processed at a small scale and highly decentralized. “Clearly, the law has been designed to lubricate international trade and the expansion of the global agribusiness,” says Shiva. “Consumer health, nutrition, and food culture are not even mentioned as objectives of the integrated food law. . . . [It] is a law to dismantle our diverse, decentralized food economy.”46

The rhetoric of free trade is that the governments get out of the way and let market forces do their thing. Despite this rhetoric, observes Vandana Shiva,

the government is a major player in the transfer of production from small scale decentralized systems to large scale, centralized systems under monopoly control. The state in fact is the backbone of the free trade order. The only difference is that instead of regulating big business, it leaves big business free, and declares small producers and diverse cultures illegal so that big business has monopoly control on the food system.47

This process—the transfer of production from small-scale decentralized systems to large-scale, centralized systems—is arguably the foundation of the state as an institution. It seems widely agreed that nation-states first emerged in those places where settled patterns of grain agriculture developed. The storability of grains created unprecedented potential for accumulation of resources and power. If food is all perishable and fleeting, it cannot be hoarded but must be eaten. Grains, in contrast, can be stored, hoarded, and amassed. With grain agriculture came larger-scale and more hierarchical social organization, and power has been concentrated more and more ever since. Each of us reclaims some of our power when we become small-scale producers or part of the informal sector that supports them, living the slow food ethic.

Street Food and the Importance of the Informal Economy

One way in which regulatory bureaucracies all around the world bear down upon informal, small-scale food production is through mass enforcement actions against street vendors. I receive online reports of crackdowns on street food vendors almost every week. It’s happening on every continent, always in the name of safety and hygiene, as well as in defense of “legitimate” businesses that bear greater overhead costs. In many places, rules categorically exclude street vendors, without regard for the safety standards they practice. Carts and food are confiscated, and vendors are harassed, fined, or even arrested (as in Zimbabwe; see Guerilla Gardeners Reclaiming Abandoned Lots).

Personally, I love street food. It’s cheap, fast, and easy. I know the theme of this chapter is slow food, but I think that informal street food, even though it is fast, is an important part of the cultural context championed by Slow Food. “Fast food, street food, market food, is a part of the cultural idiom of nations; it can’t be franchised out any more than oral history can be,” writes cultural historian Katherine Dillon through the Listserv of the Association for the Study of Food and Society. “It’s that local, that loved, that known.”48

Some of the most delicious and memorable food I have ever eaten has been from street vendors. Wherever in the world I have traveled, I have enjoyed street food. I think of street food from my travels in Africa most vividly. Harira is a spicy tomato-based soup served in infinite variations by Moroccan street vendors. In West Africa, sticky, starchy fufu was a daily staple I frequently bought at street stalls; it’s made from pounded cassava, usually sharp from fermentation, and served with stew for dipping.

Typically a street vendor is a small-scale operation. In its simplest manifestation it is simply food prepared in the home and then brought out to the street to sell. This is the informal economy, an easily accessible way to use culinary skills to earn some money without a wage job and without investing big bucks. In this informal realm many people support themselves and feed themselves. It seems like free trade to me. Expensive facilities do not guarantee good hygiene. Conscientious practices do.

When I was a kid, some of New York City’s Upper West Side neighborhood food shops sold pastries that were prepared by old women, immigrants from Europe, in their home kitchens. This was considered acceptable practice and even something to boast about. Increasingly, though, such informal practices are not tolerated. In 2005 the Tennessee agriculture department cracked down on vendors at the Greeneville Farmers’ Market in eastern Tennessee. Vendors were informed they could no longer sell jams, jellies, pickles, baked goods, or any other prepared foods unless they were prepared in a licensed, up-to-code kitchen. In most places in the United States, a home kitchen in which daily food preparation takes place cannot be licensed as a commercial kitchen. Period.

Some of the vendors challenged the enforcement officers, asking how selling baked goods at the farmers’ market was any different from selling them at a charity bake sale. “We just physically can’t get to all of them,” replied an agriculture department official. “We don’t actively seek out somebody having a charity fund-raising sale.”49 But legally, in more and more places, even bake sales—that venerable tradition of grassroots fund-raising—are illegal.

Food production in an unregulated home kitchen is considered a potential public health danger. Because the kitchen hasn’t been inspected, something could be contaminated; people could get sick; someone could die. Therefore the only way to be safe is for all food to come from inspected facilities. A friend reports that her child’s school prohibits parents from sending homemade food to school events with their children. They must send prepackaged food. Without state inspection and factory standards, we are all presumed to be at risk.

And yet, look at all the informal food-swapping that goes on in peoples’ lives, from kids trading sandwiches at school to potluck dinners and the informal commerce of roadside garden stands and bake sales. “Without involving any advertising agencies, shipping firms, fancy packaging, or middlemen, millions of pounds of American foods have been bought with cash in hand, bartered for, or given away as gifts every summer of our lives,” writes Gary Paul Nabhan.50 Almost always, it’s okay.

Occasionally there are freak incidents of contamination, both within and outside of the system of kitchen health inspections. Sure, there are people with disgusting kitchens you wouldn’t want to eat from, just as there are inspected restaurants with disgusting kitchens you wouldn’t want to eat from. Eating has its inherent dangers that no amount of policing can prevent, and enforcement is always subject to corruption and officials “looking the other way.” Don’t succumb to the paranoid fantasy that only licensed food is safe! The free trade of delicious home cooking is a neighborly tradition everywhere that must be practiced and safeguarded.

Fortunately, centralized control can never be complete. Informal-sector food economies thrive in many varied forms. In Italy a popular underground movement is informal roving restaurants called fai date (“do-it-yourself”). Hosts publicize locations via cell-phone text messages and offer meals for around fifteen euros. “The authorities have taken a dim view of the practice . . . because the hosts avoid paying taxes and sidestep health and safety rules,” according to a British news report.51 A similar trend has been reported in the United States. “Restaurants of dubious legality, where food is cooked in apartments and backyards, abound across the United States,” writes the New York Times.52 The San Francisco Chronicle calls them “culinary speakeasies.”53 “Unlicensed restaurants tend to be very, very, very hidden, and reticent about admitting strangers,” says New York food critic Jim Leff, who also reports that “home kitchen take-outs are fairly common in the African expatriate community.”54

Legal action taken against these marginal microenterprises does not make people safer. It only outlaws amateurism in food production and makes us more dependent upon specialists and mass production. This erodes small-scale traditional practices and promotes cultural homogenization and centralized control. Freedom-loving people everywhere can resist this process by participating in informal-sector, community-based food production.

Rediscovering Traditional Food Processing

The skills needed for community-based production of many foods have become rare and require rediscovery. In fact, this is the reason that I have come to meet so many food activists working on so many different important projects: the skills of home fermentation, just like the skills of seed saving, are low-tech rituals that people have been practicing for literally thousands of years but that have become obscure in our time; they are mystifying to most folks because they have disappeared into invisible faraway factories, leading people to believe that they are potentially dangerous or require great scientific expertise or technical precision. We need to revive traditional food-processing wisdom and skills, which have the potential to improve health and nutrition and to increase the potential for community food sovereignty.

The promise of industrialized food processing was liberation from drudgery. “However much I value elements of the old ways,” explains Gary Paul Nabhan, “neither my political fervor for them, nor my intellectual curiosity about them, would be enough to convince my mother or my aunts and uncles that there was anything more than drudgery in all that daily food preparation.” When he asks his mother to teach him how her mother cooked, she replies, “That was too much work. . . . I don’t want to go back there.” Nabhan reflects:

Whenever I tell them I’d like to learn some of our family’s traditions in order to integrate them into my life, they hear but one thing: He wants to go back. . . . What is curious is that while my elders see “back” as someplace that progress has allowed them to escape from—the wrong end of a linear trajectory—I imagine my life as looping and relooping, circling back to pick up something that we have forgotten, something that we desperately need for our health and our happiness, something precious we stoop down to cradle and carry along with us, as we curve out in a new direction.55

The daily grind of food production—shared by all members of the household rather than heaped upon one overburdened person—is actually an important rhythm that can structure our lives and create a context for social interaction and community building. In our “liberation” from the drudgery of these activities, much has been lost. Children have been deprived of opportunities for skill-building and meaningful contributions to family life; for stimulation they turn instead to television and computer games. Harvest and food processing have historically brought people together for purposeful and ritualistic activity. The loss of control over our food in the name of convenience and liberation has actually been a major factor in community disintegration.

Reviving traditional food-processing skills involves a learning curve. Even with a great teacher, discovery is experimental, because subjective judgment is acquired only through experience, and every food can be produced in a multiplicity of ways. It is an adventure to learn to make cheese, butcher and cure meat, and ferment vegetables and grains. In the summer, when the milk from our herd of goats is most abundant, the Short Mountain kitchen becomes a cheese workshop, where several of us amateur experimentalists learn cheese-making techniques by observing one another’s successes and failures. This summer I’ve discovered molds, not the kinds that can grow on cheese, but rather the kinds that express shapes and hold forms. I’ve learned that people are much more excited to eat a given cheese if it has a cute shape rather than the amorphous blob that is formed when cheese hangs in cheesecloth. Producing food well takes some learning, at any scale. When I visited an Amish dairy farmer in Pennsylvania, he was eagerly awaiting the arrival of a one-hundred-gallon cheese tank. Though he already was producing butter, yogurt, kefir, cottage cheese, and buttermilk, he had no experience making harder cheese and quizzed me about aspects of making cheese with rennet.

In many parts of the United States we are seeing a revival of local cheesemaking and brewing (in microbreweries). I’m also finding locally produced sauerkraut and other vegetable ferments in more areas. But butchers have mostly disappeared from American life, and all those cured meat products people love (bacon, ham, salami, and so on) are complete mysteries to most of us. But they don’t have to be. They simply require that we be willing to learn.

My neighbor J. and his boyfriend S. have cured ham from pigs they raise. The first year, the hams were great. Then, the next year, they brought the first of the hams to S.’s family’s Christmas dinner. The ham tasted awful, but the family pretended it was delicious to be polite. J. and S. were mortified, and they realized that the ham had gone off because the weather during the initial curing period had been unseasonably warm. They waited to slaughter their next pig until it was colder outside, so the meat could cure in a cooler environment. And that seemed to do the trick.

Bill Keener, another Tennessee farmer friend, showed me a ripening salami he and his daughter Ann had prepared using methods she learned from an Italian pork farmer whose family has been making it for generations. Techniques for curing meat without chemicals have become quite obscure. Bill was concerned about the film of green mold growing over the surface. I was able to reassure him that molds are very common on the surfaces of aged foods, because the surface is the place where a food comes into contact with the spore-rich air. When we scraped it with a knife, the mold came right off and the salami was beautiful and aromatic. The Keeners were not ready to go into salami production yet, but they’re learning, and one day soon, they will.

The revival and dissemination of traditional food-production skills is at the core of a slow-food movement that seeks to be accessible and democratic, promoting community-based economies, indigenous foods, and diverse cultural practices. “I think it is important for those of us who appreciate slow food to also be doing slow food,” writes Jessica Prentice. “This is the only way to keep alive the idea of real food as everyday food, accessible food, common food. . . . Let’s get back into our kitchens and discover the magical things that happen when cabbage meets salt, or when honey meets yeast.”56 Rediscovering, reviving, and reinterpreting traditional food-production methods reinvigorates local food systems and helps diverse cultures survive the insidious erasure caused by the global thrust for homogenization.

Recipe: Gefilte Fish with Horseradish Sauce

Gefilte fish is a Jewish Passover tradition: fish is mixed with eggs, onions, and matzo meal, then formed into balls and cooked; the fish balls are usually eaten cold with carrots and horseradish sauce. Gefilte means “stuffed,” though this recipe, like all the interpretations I have tried, makes simple fish balls.

I associate gefilte fish with my grandmother. Nobody learned how to make it from her. My mother and her sisters viewed my grandmother’s hours in the kitchen as Old World drudgery. And so gefilte fish disappeared from our lives, at least as a homemade food, as my grandmother neared the end of her life. Her gefilte fish was an annual Passover tradition that I took for granted until it was over, and then I discovered how bad commercially available gefilte fish in jars is—bland and overly fine-textured.

My grandmother, Betty Ellix, was born in 1909 near Brest, in what she always referred to as Poland, though these days it is part of Belarus, near the Polish border. Pogroms and war forced her family to emigrate, and she arrived as a child in New York, where the family settled in Brooklyn. She met my grandfather, Sol Ellix, at Coney Island. How romantic is that? One of the ways Betty showered her family with love was through the elaborate preparation of food. She would come over to our house and spend hours making savory cheese blintzes to put in the freezer that we could heat up as a quick meal. The most quoted line of my childhood was when I told her, “Grandma, it’s not that I don’t like your chopped liver. I don’t like anybody’s chopped liver.”

It is common for assimilated Jews who have lost many of our food traditions to bemoan the loss of gefilte fish and other traditional holiday feast foods, as if their preparation were so mysterious and elaborate that we could not possibly learn to master them. In fact, gefilte fish is quite straightforward. It’s basically the “Hamburger Helper” of fish, a classic poor people’s culinary tactic of stretching scarce fish (or meat) by mixing it with other more abundant, cheaper ingredients. I taught myself to make gefilte fish, rescuing this delicious ritual from extinction within my family. Every time I make it, the familiar smell of the boiling fish stock brings me back to my grandparents’ apartment, and I feel uplifted by the presence of my grandmother, as if the fishy smell of revived tradition channels her spirit into my kitchen.

Ingredients (for about twenty-five gefilte fish balls, or 5 pounds)

2½ pounds fish meat (a mix of carp, whitefish, and pike, or others), plus bones and a head

2 tablespoons vinegar

6 large onions

6 carrots

2 large eggs

1½ cups matzo meal

1 tablespoon honey

1 tablespoon salt, plus more to taste

1 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper, plus more to taste

My grandmother made her gefilte fish out of a mix of three freshwater fish: carp, whitefish, and pike. Carp is very cheap, at around a dollar a pound. It is also rather dense in texture, and adding other types of fish lightens the gefilte mix. To begin, filet the fish, separating the flesh from the bones as best you can. Leaving the flesh aside, make the fish stock: gently simmer the bones and head, along with the vinegar, half the onions, and half the carrots, in about 2 gallons of water, uncovered. Vinegar’s acidity helps release minerals from the bones. The head is full of important fat-soluble nutrients and also contains the thyroid gland, which releases compounds that nourish our own thyroids. Fish stock does not benefit from all-day cooking like other meat stocks. According to Harold McGee’s On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen, fish collagen melts at lower temperatures and dissolves much more quickly than the collagen in mammal and bird bones, and it can be damaged by overcooking.57 For this reason, the stock should simmer for only about an hour.

As the stock cooks, chop the fish. A meat grinder is ideal, or you can finely mince it with a sharp knife. My friend Merril uses a rounded-blade chopper, sometimes called a mezzaluna (half moon), in a wooden bowl. Or you can use a food processor, though if you do, be sure not to overprocess it into a paste or you will lose the texture of the fish. Finely chop or process the remaining onions. Scramble the eggs, and mix them together with the fish, onions, matzo meal, honey, salt, and pepper. Traditionally matzo meal is used in gefilte fish, but any bread crumbs will do. Mix these ingredients thoroughly. If the mixture is too dry and fails to bind, add a little water to help it hold together.

Strain the stock and discard the spent solids. Add salt and pepper to the stock to taste. Slice the remaining carrots (diagonally is how my grandmother always sliced them). Form the fish mixture with a spoon and your hands into oval fish balls. Drop the fish balls and carrot slices into the hot stock, and gently simmer for twenty minutes. Remove the gefilte fish and carrots from the stock. Cool the stock, which will thicken into a somewhat gelatinous consistency. Pour the cooled gelatinous stock over the gefilte fish and carrots, and refrigerate. The gelatinous stock keeps the gefilte fish from drying out. The stock was my grandfather’s favorite part of gefilte fish, and we grandchildren would watch him slurp that gelatin down in grossed-out disbelief. Now I’ve come to enjoy the gelatin—concentrated nutrients from the whole fish—and appreciate its rich flavor and unusual consistency. I grew up eating gefilte fish cold, with a few carrot slices, and always with plenty of horseradish sauce.

Horseradish sauce is extremely simple to make: At least a few hours before serving, finely grate horseradish roots. Salt to taste and add just enough vinegar so that when you press down on the grated horseradish, it is submerged in liquid. Grate a little beet into the sauce too, for red color. Horseradish is an easy-to-grow perennial plant. Harvesting inevitably leaves root fragments that regenerate into new plants.

You can vary the gefilte fish recipe with whatever fish are available to you. I made delicious gefilte fish in Maine with hake, sole, and monkfish tails my friend Ed brought home from the fish auction where he works. It was winter, and we enjoyed them not only cold, the way I grew up eating gefilte fish, but hot in the rich and soothing fish stock, like fish dumplings in a Vietnamese soup.

Shav, a cold sorrel soup, is another compellingly delicious Old Country food that I associate with my grandparents. They kept a pitcher of it in the refrigerator in summer and drank it out of a glass. Sorrel is a sour green with cooling qualities, a perfect refreshing treat for a hot summer day. Sorrel is not commonly found in U.S. supermarkets, but it is among the easiest foods you can grow yourself, because in contrast to other greens, sorrel is perennial. This means that the plant lives for years, sending up fresh greens each year from the same roots. Sorrel also grows wild; the variety that grows as a weed in our gardens looks something like clover and is known as wood sorrel.

Ingredients (for 1 gallon, or eight large or sixteen small servings)

1 pound potatoes (some recipes specify “mealy” potatoes)

1 pound sorrel

1 tablespoon butter or oil

Salt to taste

Sour cream

Sorrel. ©Bobbi Angell. Used by permission.

Peel and coarsely chop the potatoes. Clean the sorrel and separate the leaves from the fibrous stalks. Tie the stalks into a bundle with cheesecloth, and boil them with the chopped potatoes for about fifteen minutes in 3½ quarts of water (or a stock for a richer flavor). Meanwhile, chop the sorrel leaves and sauté them in butter or oil for just a moment, until they wilt. Remove the bundle of stalks from the stock, squeeze any excess water from them back into the stock, and then discard the stalks. Mash the potatoes in the stock to thicken it, add the sautéed sorrel, and simmer for five minutes. Add salt to taste. If you have pickle brine or sauerkraut juice on hand, you can use it instead of salt, adding it to the soup after it has cooled to body temperature; the brine or juice will contribute not only the salt it contains but also other flavors and live-culture goodness. Allow the soup to cool and store it in the refrigerator. Serve shav cold with a dollop of sour cream (see recipe, Sour Cream and Cottage Cheese from Raw Milk).

The sour cream served in shav not only enhances the flavor but also plays an important protective role. Sorrel has high levels of oxalic acid, which can create problems, including kidney stones, when consumed in large quantities. Dairy calcium neutralizes the oxalic acid.

Action and Information Resources

Books

Alley, Lynn. Lost Arts: A Celebration of Culinary Traditions. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press, 2000.

Heldke, Lisa M. Exotic Appetites: Ruminations of a Food Adventurer. New York and London: Routledge, 2003.

LaDuke, Winona. All Our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life. Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 1999.

Nabhan, Gary Paul. Why Some Like It Hot: Food, Genes, and Cultural Diversity. Washington, DC: Island Press, 2004.

Nabhan, Gary Paul, and Ashley Rood, eds. Renewing America’s Food Traditions (RAFT): Bringing Cultural and Culinary Mainstays of the Past into the New Millennium. Flagstaff, AZ: Center for Sustainable Environments at Northern Arizona University, 2004. Available online at www.environment.nau.edu/raft.

Petrini, Carlo, and Ben Watson, eds. Slow Food: Collected Thoughts on Taste, Tradition, and the Honest Pleasures of Food. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green, 2001.

Prentice, Jessica. Full Moon Feast: Food and the Hunger for Connection. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green, 2006.

Shiva, Vandana. Biopiracy: The Plunder of Nature and Knowledge. Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 1997.

———. Tomorrow’s Biodiversity. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2000.

Periodicals

Cultural Survival (quarterly)

215 Prospect Street

Cambridge, MA 02139

(617) 441-5400

Food, Culture & Society: An International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research (quarterly)

Association for the Study of Food and Society

Slow: The International Herald of Good Taste (quarterly) and The Snail: All the Food That’s Fit to Print (quarterly) Available from Slow Food USA (see below)

Film

The Meaning of Food. Pie in the Sky Productions, 2005; www.pbs.org/opb/meaningoffood/.

Organizations and Other Resources

Alaska Native Science Commission

429 L Street

Anchorage, AK 99501

(907) 258-2672

American Chestnut Foundation

PO Box 4044

Bennington, VT 05201

(802) 447-0110

American Livestock Breeds Conservancy

PO Box 477

Pittsboro, NC 27312

(919) 542-5704

American Prairie Foundation

PO Box 908

Bozeman, MT 59771

(406) 585-4600

Bring the Salmon Home Campaign

Karuk Tribe of California

PO Box 1016

Happy Camp, CA 96039

(530) 493-5305

California Food & Nutrition Program

Northern California Indian Development Council

241 F Street

Eureka, CA 95501

(707) 445-8451

Indigenous Environmental Network

PO Box 485

Bemidji, MN 56619

(218) 751-4967

Indigenous Peoples Council on Biocolonialism

PO Box 72

Nixon, NV 89424

(775) 574-0248

Intertribal Bison Cooperative

1560 Concourse Drive

Rapid City, SD 57703

(605) 394-9730

Makah Tribe

PO Box 115

Neah Bay, WA 98357

(360) 645-2201

Native Seeds/SEARCH

526 North 4th Avenue

Tucson, AZ 85705-8450

(866) 622-5561

Native Web

Resources for Indigenous Cultures around the World

Navdanya

A-60, Hauz Khas

New Delhi 110016

India

Pawpaw Foundation

The PawPaw Foundation

c/o Pawpaw Research

147 Atwood Research Facility

Kentucky State University

Frankfort, KY 40601-2355

Renewing America’s Food Traditions (RAFT) Coalition

Center for Sustainable Environments at Northern Arizona University

PO Box 5765

Flagstaff, AZ 86011

(928) 523-0637

www.environment.nau.edu/raft/index.htm

Seed Savers Exchange

3094 North Winn Road

Decorah, IA 52101

(563) 382-5990

Sequatchie Valley Institute/Moonshadow

1233 Cartwright Loop

Whitwell, TN 37397

(423) 949-5922

Slow Food International

Via Mendicità Istruita, 8

12042 Bra (CN)

Italy

(39) 0172 419 611

Slow Food USA

20 Jay Street, Suite 313

Brooklyn, NY 11201

(718) 260-8000

Society for the Preservation of Poultry Antiquities

Route 4 Box 251

Middleburg, PA 17842

(570) 837-3157

www.feathersite.com/Poultry/SPPA/SPPA.html

Village Earth

PO Box 797

Fort Collins, CO 80522

(970) 491-5754

White Earth Land Recovery Project

32033 East Round Lake Road

Ponsford, MN 56575

(218) 573-3448