S

URVEYING HIS newly won domains in northern India, Zahirrudin Muhammad Babur was appalled. Descendant of Tamurlane and, more distantly, of Genghis Khan, the victor of Panipat (1526) would have preferred to rule Samarkand; instead he had to settle for the dusty vastnesses of Hindustan. In the few years left to him Babur set about putting the stamp of civilization on the Gangetic plain, creating not palaces and forts and cities but gardens, introducing “marvelously regular and geometric gardens” in “unpleasant and inharmonious India.”1 The Mughal ruler was neither the first nor the last invader to look upon the Indian landscape and find it wanting, and neither the first nor the last to remake it in an image more suited to his own notions of an ordered universe. Just as Mughal gardens were a microcosm of the world as it should be, so British gardens became maps of an ideal world seen through their insular prism.

Babur freely acknowledged that what had lured him to Hindustan was its wealth: it had “lots of gold and money.”2 The same magnet drew the British to India. They came originally not as conquerors but as traders, vying with many other nations for a share of the subcontinent’s riches. In 1600 Queen Elizabeth I, a contemporary of Babur’s grandson Akbar the Great, chartered the earliest merchant ventures that would evolve into the British East India Company.3 Their immediate object was to challenge the Portuguese and Dutch in the East Indies and gain a foothold in the lucrative spice trade; India was an unanticipated by-product. William Hawkins, scion of the preeminent Tudor seafaring family, was the first commander of an English vessel to set foot in India, landing at Surat on the northwest coast in 1608. From its modest “factory” or trading station, the Company sent a series of embassies to the court of the “Great Mogul” in hopes of obtaining a firman (royal license) that would smooth the path of commerce. Hawkins himself found such favor with Emperor Jahangir that he was presented with “a white mayden out of the palace.” Mutual gift-giving was a time-honored lubricant of social, political, and economic relations, and one embassy presented the emperor with paintings, “especially such as discover Venus’ and Cupid’s actes.” In fact European arts, both secular and religious, came to exert a fascination for Mughal rulers and artists.4

From Surat British merchants fanned out down the west (Malabar) and up the east (Coromandel) coasts of India, competing with the Portuguese, French, Dutch, and other nationalities. The Portuguese had long dominated the commerce of the Arabian Sea from their outpost in Goa. On the Coromandel Coast, British Madras had to compete with the French Pondicherry, while Calcutta, the latecomer, gradually extended its sway over Bengal, eliminating both European and Indian rivals. Madras, Bombay, and Calcutta became autonomous East India Company “presidencies,” each with its fort and godowns (storehouses) and its expanding staff of merchants and “writers” (clerks or junior merchants), as well as garrisons of soldiers. From the beginning the British, like all foreigners, depended on Indian intermediaries and bankers to facilitate trade, especially in the handwoven textiles that formed the bulk of exports before the Industrial Revolution in England reversed the flow. And like all foreigners they relied on good relations with local rulers—or, if not good relations, at least relations of reciprocal self-interest. This became more complex after the death of Emperor Aurangzeb in 1707 and the gradual dismemberment of the Mughal Empire, forcing them to deal with a multiplicity of successor states.

Initially “visions of conquest and dominion . . . seem never to have entered into their minds”—they were hardly necessary—but by the mid-eighteenth century the Company found itself caught up more and more in military confrontations with Indian rulers and with other European powers, often in shifting alliances.5 At the same time, European mercenaries played an ever-expanding role in Indian armies, their services offered to the highest bidder. Company officials often made policy on the spot, especially in the matter of military adventures, counting on the snail’s pace of communication with the directors in London to delay interference until it was too late. Often, too, the three presidencies acted at cross-purposes and were torn by internal dissensions, as indeed were their counterparts in London. Even the formidable Warren Hastings, invested as the first governor-general in Calcutta, found it impossible to control his own council, much less the distant communities of Bombay and Madras and his still more distant employers in Leadenhall Street. Hastings willingly relied on military force to uphold British commercial interests, although he opposed the extension of direct rule in India. Bengal, “this wonderful country which fortune has thrown into Britain’s lap while she was asleep,” had been ceded to the Company under Robert Clive in 1765, but Hastings’s ideal model was derived from the Mughals: an India administered indirectly by Indians in accordance with Indian custom and law, as long as local authorities acknowledged the supremacy of the British governor and council in Calcutta and their right to a portion of landed revenues. Not surprisingly, Calcutta’s first newspaper nicknamed him “The Great Moghul.”6

Within a decade and a half of Hastings’s departure from India, however, a sea change had taken place. In 1799 the fourth and last of the wars with Haidar Ali and his son Tipu Sultan and their French allies ended in the total defeat of Tipu, the “Tiger of Mysore,” at Srirangapatnam.7 The victorious general was Arthur Wellesley, later Duke of Wellington. The campaign marked the final transformation from commercial to imperial ambition; empire had duly followed trade. By the time the Company was dissolved in the aftermath of the Uprising of 1857, it had become the shadow master of all India, but its powers had long since been usurped by the British government. It had been “restrained and reformed” by a series of parliamentary acts until it was no longer an independent mercantile entity but a responsible administrative service. The motley collection of “rumbustious and individualistic” traders had metamorphosed into a high-minded team of district collectors, part administrator, part magistrate, part tax collector, and part development officer, “destined to join those many-armed gods in the Hindu pantheon and to become a feature of the Indian landscape.” How appropriate that their compatriots referred to them, not always approvingly, as “the heaven-born.” Over time they came to form something close to a hereditary caste, as a cluster of fifty to sixty interconnected families supplied the vast majority of the civil servants who governed India for several generations leading up to independence in 1947. The empire, it has been suggested, provided a sort of outdoor relief for the British middle class.8 Ironically, in the new order of things, the once-glorious merchants (boxwallahs) and planters ranked virtually on a par with untouchables.

British India was a curious patchwork, even an accretion. An official during its heyday likened the imperial presence to “one of those large coral islands in the Pacific built up by millions of tiny insects, age after age.” Roughly a third of the territory continued to be governed by hereditary princes who exercised considerable autonomy, albeit under the surveillance of representatives of the Indian Political Service. The rest of India was administered directly through the secretary of state in London, responsible to Parliament (when it deigned to take an interest) and the viceroy in Calcutta. Under the viceroy were the governors or lieutenant governors of the individual provinces. While their numbers increased dramatically during the century, the ranks of British civil servants responsible for local administration were ludicrously thin. A thirtysomething “collector” might find himself in charge of a population as numerous as that of Elizabethan England, having as his Burghley a magistrate of twenty-eight and his Walsingham a lad who took his degree at Christ Church scarcely fifteen months past.9 As late as 1921 some 22,000 civilians governed a population of nearly 306 million. Behind them stood a force of about 60,000 British and 150,000 Indian troops. Because both civilian and military expenses had to come entirely out of Indian revenues, poorly paid Indians or mixed-race Eurasians staffed the lower levels of government—police, clerks, and railway workers. Only very slowly did the elite Indian Civil Service admit Indians into its ranks.10

How They Lived Then:

From Garden House to Bungalow

During the early centuries the Anglo-Indians, as the British came to be known (only later did this term come to designate people of mixed race), had two intertwined goals: to live long enough to bring home a sizeable nest egg, preferably enough to set themselves up as landed gentry, possibly even to buy a seat in Parliament. It was an age

When Writers revelled in barbaric gold

When each auspicious smile secured a gem

From Merchant’s store or Raja’s diadem.11

What could be more tempting for ambitious young men without family fortune than to “shake the pagoda tree” (pagodas were a form of currency) for all it was worth?

And being young men—some as young as sixteen—they no doubt imagined they were immortal. Yet death was omnipresent. In Kipling’s words, “Death in my hands, but Gold!”12

It has been estimated that about two million Europeans, most of them British, were buried in the subcontinent in the three hundred years before independence. As the proverbial wisdom had it, “Two monsoons are the Age of a Man.”13 Of the nineteen youths who sailed out to India with James Forbes in 1766, seventeen soon died, an eighteenth a little later; only Forbes survived to return home seventeen years after he first landed and to live to a ripe old age.14 It became a commonplace that one’s dinner companion one day might be laid to rest in the churchyard the next—and an often overcrowded churchyard at that, exhibiting “the most frightful features of a charnel-house.”15 As late as 1827 a writer commented, “There is no country in the world where the demise of one of a small circle is regarded with so much apathy as in India. Sickness, death, and sepulture follow upon each other’s heels, not infrequently within the four-and-twenty hours.”16 For Emily Eden, sister of a governor-general, there was no such apathy in her reflection that “almost all the people we have known at all intimately have in two years died off. . . . None of them turned fifty.” In 1880, by which time a network of railroads crisscrossed the country, the viceroy’s chaplain was unnerved to learn that there were coffins stocked in every station along the line as a necessary precaution. Even those who are well, remarked Eden, “look about as fresh as an English corpse.”17 Added to this was the isolation of life in India. The journey from England could take six months or more before the advent of steamships in the mid-nineteenth century and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. Communication was achingly slow and unpredictable. Ships were not infrequently lost at sea, with precious cargoes and, for some, even more precious letters, newspapers, and books. “It is really melancholy to think what a time passes between the arrival of each fleet,” lamented Lady Henrietta Clive in 1800; one lived with “constant expectation of news and as continual a disappointment.”18

In the beginning, factors—merchants—were largely confined to Company forts and factories. Here they labored over their account books and dealt as best they could with the steady bombardment of directives from London, usually long out of date by the time they reached India. Not for nothing were the junior factors known as “writers,” living “by the ledger and ruled with the quill.”19 As merchants felt more confident, they moved outside the forts, but security was still a concern. A Venetian merchant made several visits to Surat in the mid-seventeenth century when it was still a hub of trade, its port full of ships from Europe, Persia, Arabia, Batavia, Manila, and China. “Upon the sea-shore, on the other side of the river,” he writes, “the Europeans have their gardens, to which they can retire should at any time the Mahomedans attempt to attack them. For there, with the assistance of the ships, they would be able to defend themselves.”20 What the gardens looked like we are not told, but they may well have been inspired by those of their Mughal hosts—and sometime enemies—enclosed in walls, with fountains and scented trees and flowers.

Unlike Surat—the principal port of the Mughals—Madras, Bombay, and Calcutta were entirely European creations. Madras was the earliest. Legend had it that its founder, Francis Day, chose the site, a small fishing village, mainly because he was enamored of a lady at the nearby Portuguese fort at San Thomé (supposed site of the martyrdom of the Apostle Thomas of the Indies). Certainly it had no obvious advantages: it was little more than a surf-pounded strand on the Bay of Bengal with no natural harbor or even a navigable river. The irascible Captain Alexander Hamilton pronounced it “the most incommodious place I ever saw,” adding that the sea “rolls impetuously on its shore, more here than in any other place on the coast of Coromandel.”21

For a first-time visitor, landing could be a harrowing introduction to India. Ships had to anchor beyond the bar, unloading their passengers and freight into small native craft (Fig. 4). Passengers climbed down a ladder, jumped into small native boats bobbing in the heavy surf, and were paddled ashore by nearly naked but extraordinarily agile seamen, clad only in a “turban and a half-handkerchief,” according to Maria Graham, who had married an English naval officer on the voyage out in 1808. Fortunately, their dark skins prevented them from looking “so very uncomfortable as Europeans would in the same minus state,” as one English lady reassured her readers. The sea could be terrifying—“I don’t know why we were not all swamped, as I never saw such frightful waves; and no ordinary boat could have lived in them. I suppose the lightness of the native boats, which are made of bark, sewn together with thick twine, renders them safe. Arrived at the pier a tub was let down, and we were hoisted up in it.”22 This was written in 1867, but little had changed from two centuries earlier except that the boatmen had become Christian and cried out to Santa Maria and Xavier as they battled the surf.

Fig. 4. Surf boats, Fort St. George, Madras. Pencil on paper

[The British Library Board, WD1349]

From its founding, Madras was divided into “White Town,” the area centered on its “sandcastle fortress,” Fort St. George, and “Black Town” along the shore to the north. The three-story governor’s house looked out over the Bay of Bengal, with St. Mary’s rising within the fort, the first Anglican church east of Suez. Textiles were the making of Madras, and as the trade prospered whole villages of spinners, weavers, dyers, and finishers transplanted themselves from the South Indian countryside to the growing town. They were joined by other artisans, farmers, and a large population of untouchables who did the menial labor; for much of its history Madras remained an amalgam of separate, largely caste- and ethnically based neighborhoods and villages with close ties to the land. “I cannot make out where it begins and ends,” wrote Lady Canning in some exasperation in 1856. At what urban core it possessed resided an expanding population of Europeans (civil and military), Muslims, and an influx of North Indians.23

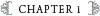

With the English came gardens. At first these seem to have been primarily practical—but not entirely. Thus, an account of the 1670s describes English gardens in the heart of the city “where besides Gourds of all sorts for Stews and Potage, Herbs for Sallad, and some few Flowers as Jassamin, for beauty and delight, flourish pleasant Topes [clumps of trees] of Plantains; Cocoes; Guiavas, a kind of Pear; Jawks [jackfruit] . . . ; Mangos, the delight of India; a Plum, Pomegranets, Bonanoes which are a sort of Plantan, though less, yet more grateful, Beetle [betel].” What is interesting in this description is that it includes only native fruits and the quintessential Indian flower, jasmine, and at the same time assumes readers will be unfamiliar with guavas and bananas. But already it singles out mangoes as the Indian treat of treats. A little later Governor Elihu Yale put in a “physick garden,” a garden for medicinal plants, within the fort. Although the Company condemned him for this unauthorized expenditure, one sympathizes with his motives.24 By 1710, however, the Company had built a leisure garden for the governor’s refreshment during the hot winds. It contained “a lovely Bowling Green, spacious walks, Teal-pond and Curiosities preserved in several Divisions are worthy to be admired,” an enigmatic addendum. Lemons and grapes also grew in the garden but demanded a great deal of water (Fig. 5).25

Before long the British were feeling claustrophobic in their tight little enclave. They had taken to picnicking on St. Thomas Mount (San Thomé), a few miles out in the country, where the government maintained a garden and sanatorium “for sickly People to recover their healths.” In the second half of the eighteenth century they began building garden houses here and then all over Choultry Plain, closer and more accessible to the center of Madras. “The English boast much of a delightful mount about ten miles distant,” wrote. Jemima Kindersley, wife of a colonel in the Bengal Artillery, in 1765, “where the Governor and others have garden houses which, they say, are both cool and elegant.” This was the moment of the “Nabobs,” the Jos Smedleys so broadly caricatured in Thackeray’s Vanity Fair who had shaken the pagoda tree with great success. The move to the suburbs came as a craving for a change of scene, an escape from the sea and sand of their working days in the White Town. “Originally the country house was not a permanent residence for its owner. It was designed for week-ends and holidays, and its great feature was its garden,” for fruit and flowers did poorly in the sandy soil and brackish water of the beachfront.26

Fig. 5. Fort St. George, Madras: Plan showing Governor Pitt’s Great Walk

and the Company’s Garden on the other side of the river

[From ray Desmond, European Discovery of the Indian Flora, 1992]

Soon the most prosperous Europeans had settled into these fine houses permanently, commuting into the fort every day in their palanquins or carriages. The air was fresher in the suburbs than in the congested fort area, and here also they could, with some stretch of the imagination, replicate the life of the English gentleman. Houses were “spacious and magnificent,” with porticoes open to catch the breeze, surrounded by gardens and trees; some even boasted ornamental lakes and deer parks (Fig. 6). By 1780 there were two hundred suburban houses in the environs of Madras, with plots ranging in size from a few acres to fifty or more, transforming what had been barren sand into a “beautiful scene of vegetation.” Dubashes, leading Indian merchants who served as agents to the Europeans, and Muslim officials attached to the court of the Nawab of Arcot shared the taste for suburban living. Their estates on Choultry Plain often outdid the Europeans in size and in the elegance of their European-style mansions and furnishings. By 1800, however, although the number of suburban residences had doubled, land had become scarcer, prices higher, and the average size of holdings smaller in consequence. By this time, too, government regulation of Company employees had begun to curb the excessive fortunes of the earlier period and diminish the role of dubashes as intermediaries between the cultures.27

Fig. 6. Palladian garden house, Madras, c. 1790. Watercolor

[The British Library Board, Add.or.740]

In the early twentieth century, Yvonne Fitzroy, secretary to the vicereine Lady Reading, reveled in the surviving eighteenth-century beauty of Madras— “the green, green gardens, the sea . . . the smiling faces of the India that escaped invasion and the hand of conquest until the English came.” Fitzroy concluded that in contrast to the pretensions of Calcutta and the vulgarity of Bombay, “Madras seems to be less a city than a vast garden where houses happen.”28 She was mistaken in her history, since Madras had been overrun by the French and raided by Haidar Ali on several occasions in the mid-eighteenth century, but correct in emphasizing its sprawling suburban character. As Lord Valentia commented in 1804, there was virtually no proper European town because “the gentlemen of the settlement live entirely in their garden-houses, as they properly call them; for these are all surrounded by gardens, so closely planted, that the neighbouring house is rarely visible.”29 Almost a century later, a visiting journalist looked down from the lighthouse atop its High Court and found Madras “more lost in green than the greenest city further north.” On the one side was “the bosom of the turquoise sea, the white line of surf, the leagues of broad, empty, yellow beach; on the other the forest of European Madras, dense, round-polled green rolling away southward and inland till you can hardly see where it passes into the paler green of the fields.”30

No doubt the avenues of trees lining the main thoroughfares from the fort to European neighborhoods enhanced the greenness that so impressed even early visitors. “The roads,” noted Emma Roberts in 1836, “planted on either side with trees, the villas chunamed . . . and nestling in gardens, where the richest flush of flowers is tempered by the grateful shade of umbrageous groves, leave nothing to be wished for that can delight the eye or enchant the imagination.” She goes on to elaborate the tropical luxuriance: plumelike broadleaf plantain; bamboo, coconut and still taller palms, areca (betel), aloe, “and the majestic banian [banyan], with its dropping branches, the giant arms outspreading from a columnar and strangely convoluted trunk, and precipitating pliant fibrous strings, which plant themselves in the earth below, and add to the splendid canopy above them.” The banyan would ever be one of India’s arboreal wonders. The chunam to which Roberts refers was also a source of awe: a “glittering material” made from burnt seashells, it was used to plaster both government buildings and domestic architecture, giving them a “marble brightness” that may have accentuated still more the deep greens of European Madras. As Eliza Fay had marveled a half-century earlier, the harmony of trees, foliage, and white chunam resembled more “the images that float on the imagination after reading fairy tales, or the Arabian Nights entertainment, than any thing in real life.”31 Landing at the city in 1780, seeing it in the brilliant sunshine, a new arrival could not resist the comparison with “a Grecian city in the age of Alexandria.”32 No such flights of Hellenistic fancy for Lady Charlotte Canning, wife of the governor-general. “Madras from the sea,” she declared, “looks like a scrap of Brighton, except that the houses are very large.” But, then, all that was visible were the endless strip of sand, the fort, and a “few offices and stores,” little enough to impress someone coming from Bombay, with its glorious harbor and Malabar Hill rising in the background.33

In Madras, as would be the case in British settlements everywhere in the world, Government House epitomized imperial rule and imperial ideology. During the early days, it was tucked safely within Fort St. George, but in the eighteenth century governors, like everyone else, were desperate to escape to the country. The first garden house was destroyed by the French in 1746. It was replaced by a fine new one set in seventy-five acres in the suburb of Triplicane, approached by “an avenue of noble trees” and with a view of the sea and of the fort.34 We do not know what these early government houses and grounds looked like, but one governor, Lord Pigot, at least had “a very English love of gardens” along with a very English love of hunting. He made the mistake, however, of quarreling violently with his council, who overthrew and took him prisoner (Madras had a habit of deposing its governors). During his captivity he suffered a sunstroke while gardening and died not long afterward.35

More fortunate than Pigot, Edward Clive, son of Robert Clive, hero of Plassey, became governor of Madras in 1798 and immediately set about improving Government House and its gardens. He was not a particularly effectual governor (“an amiable mediocrity”), but he and his wife were garden enthusiasts and avid botanists. They also made sure they got their share of the mind-boggling loot that fell to the British with the defeat of Tipu Sultan: ornate weapons, curly-toed slippers, and a jeweled tiger-headed finial from his throne; Tipu’s elaborate chintz tent made an ideal marquee for garden parties at Government House. During her travels in southern India in 1800, Henrietta Clive sent not only the spoils of war but also shipment after shipment of plants and trees to her husband in Madras. One of his triumphs was to successfully graft a mango tree that he then sent to Kew Gardens in London. To carry out his ambitious plan of renovating the Triplicane garden house, he brought in the architect-astronomer John Goldingham, who repaired and enlarged the house and laid out a large English park around it. He accentuated aspects of the landscape and added new ones, including artificial mounds and a sunken garden. Most spectacularly, Clive and Goldingham built a sumptuous banqueting hall, detached from the main house and in the form of a Tuscan-Doric temple (Bishop Heber later thought it “in vile taste”). All this expenditure was too much for the court of directors back in London, especially since it coincided with Lord Wellesley’s extravagances in Calcutta and Barrackpore (see Chapter 2), and Clive, like Wellesley, was recalled.36

Fig. 7. Government House, Madras

[Postcard, author’s collection]

Clive’s showpiece fell into neglect after his departure; the house was in ruins and the pleasure grounds a desiccated and dreary dustbowl. When Charles Trevelyan became governor in 1859 he restored both (Fig. 7). It took eleven hundred men just to clear away the undergrowth around the house and in the adjoining park of Chepauk Palace, the proto-Indo-Saracenic pile that had been the pride of the Nawab of Arcot. Ever the civic-minded builder, Trevelyan aimed to open the two as a public park, complete with zoo. With the zeal of a latter-day Capability Brown, he envisioned a “picturesque wilderness laid out according to the most approved principles of landscape gardening,” with ornamental lakes like those in St. James’s Park and a palmetum displaying “all kinds of rare flowering trees, graceful bamboos and creepers along the waterside.”37

The main reason for the neglect of the governor’s house in Triplicane was the addition of still another official country retreat in Guindy Forest, some six miles farther out of the city. The property had passed back and forth between Company and private hands, both Indian and European, until at last it was purchased for official use by Governor Sir Thomas Munro in 1824. Munro argued that the governor needed a quiet place “where he could transact public business uninterruptedly,” insisting that Clive’s country house was no longer in the country, thanks to encroaching urbanism, while the residence in the fort was being taken over by the secretariat.38 His adored wife loved flowers, and his little son Campbell (Kamen) loved to play in the gardens at Guindy. When the child became ill and his mother had to take him back to England, Munro’s visits to Guindy became almost unbearably sad. Just before leaving for a long tour of southern India, he spent a last weekend there, and he wrote to her: “I took as usual a long walk on Sunday morning; there had been so much rain [it was July], that the garden looked more fresh and beautiful than I ever saw it; but I found nobody there. . . .It was a great change from the time when I was always sure of finding you and Kamen there. It is melancholy to think that you are never again to be in a place in which you took so much pleasure.” He knew she would want to hear how luxuriantly the hinah and baboal hedges were doing and the geraniums in pots, which looked to his untutored eye like wild potatoes, but, alas, the place “has the air of some enchanted deserted mansion in romance.”39

As so often happened in India, wife and child survived, husband/father did not: Sir Thomas, one of India’s most enlightened governors, succumbed to cholera while on tour. Guindy, however, remained the official country residence, added to and improved by later governors. It was much admired by Lady Dufferin (1886), who found the “gardens glowing with the most lovely and brilliant crotons.” On another occasion the house was illuminated as a backdrop while she and her party “sauntered for a little” in the pretty garden.40 In late 1929 Viceroy Lord Irwin pronounced Guindy “the most delicious place I have seen in India,” adding, “It stands in the middle of a delightful garden, exactly like a big English garden. . . . It really is the most English place I have seen.”41 By then it was clearly no longer Lady Munro’s garden, but more likely a testimony to the English gardener whom Lady Beatrix Stanley, wife of the governor of Madras, had brought with her (Fig. 8).

The Hyderabad Residency told an even more romantic tale. It was built by James Achilles Kirkpatrick—he who married Khair in-Nissa, the great-niece of the Nizam—at just the time Clive created his showpiece in Madras. It was also contemporary with the U.S. White House, which it resembles in its domed semicircular bay on one front and colonnaded portico on the other (Fig. 9). This extravagant Palladian villa, “one of the most perfect buildings ever erected by the East India Company,” was set in the midst of a vast if decayed stretch of much older Mughal pleasure gardens that lined the River Musi. In the center of the garden was a baradari, the open pavilion typical of Mughal gardens, adapted by the British for dining and entertaining. An avenue of mature cypresses formed an axis from which ran channels of water, fountains, pools, and beds of flowers; palm trees towered over luxuriant shrubbery. And tucked away in its own walled-off garden was the zenana built for his beloved wife (and pulled down sixty years later by a Victorian Resident, uncomfortable with reminders of the freer ways of an earlier time). Kirkpatrick kept his Mughal garden pretty much as he found it, but added fruit orchards and vegetables, looking for a “good English gardener” or one from China to assist him. When a treaty in 1800 conveniently expanded his estate, he conceived the more ambitious plan of a “natural” parkland in the style of William Kent and Capability Brown, now increasingly passé in England but a novelty in the Mughalesque garden culture of Hyderabad. He stocked it with deer, and then, because the deer needed company, elk from Bombay, and a herd of Abyssinian sheep. To prevent everything from withering away in the intense heat of Deccan summers, he sent to Bombay for fire engines to water the shade trees and pleasure grounds. Like so much of Kirkpatrick’s lifestyle, the Residency and its gardens were an amalgam of Indian and European, or, as a less charitable visitor put it, “Major Kirkpatrick’s grounds are laid out partly in the taste of Islington & partly in that of Hindostan.”42

Fig. 8. Government House, Guindy

[Photograph by author]

Fig. 9. The British Residency at Hyderabad, 1813. Aquatint, colored

[The British Library Board, X400[19]

Bombay and Calcutta were also maritime emporia built around forts. Here, too, wealthy Europeans segregated themselves in garden houses and governors outdid themselves in the magnificence of their residences. In contrast to Madras, however, Bombay and Calcutta developed as urban entities rather than simply clusters of suburban villages. And as British power moved inland to embrace the entire subcontinent and the political center of gravity moved northward, Madras was eclipsed by its sister presidencies and the burgeoning outposts of the Gangetic plain. The city that, in Kipling’s words had been “crowned above Queens” became “a withered beldame . . . Brooding on ancient fame,” left behind in the new age of imperial India.43

While the British worked day in and day out with Indians and filled their homes with Indian servants, they contrived to separate themselves increasingly from Indian life. William Dalrymple may overstate the case for the easy intermingling of races and nationalities in the earlier period, but it seems clear that the trend toward self-segregation intensified during the nineteenth century, accelerated by the agonizing events of 1857. Already in the 1790s the Company had tried to discourage the “orientalizing” proclivities of some of its employees and the common European practice of taking Indian mistresses or even wives. Some have pointed the finger at the mushrooming numbers of memsahibs flocking to India who set themselves up as “guardians of English domesticity and gentility.”44 But this is only a partial explanation and needs to be factored in with the rising tide of European theories of racial purity over the course of the century. Furthermore, there were differences in place as well as time. Maria Graham noted that there was much greater social distance between Europeans and Indians in Calcutta than in Bombay in 1810. In Bombay she had been able to meet Indian families and stop by their houses, something that was not possible in Calcutta. She does not try to explain the differences in social relations between the two cities, but it may have had something to do with the ferocious patriotism of the English in Calcutta, where society might be more refined than elsewhere but every Briton “prides himself on being outrageously a John Bull.”45

To be sure, intercourse between Europeans and Hindus was more complicated than that with Muslims or Parsees, thanks to rigorous caste and food taboos. When Hindus did entertain Europeans, they often served them separately or did not dine with them. Dwarkanath Tagore, for example, maintained a sumptuous residence primarily to receive the social elite of Calcutta, and although he served all meats save beef to Europeans and sat with his guests as they dined, he did not touch the food. Even this was too much for his female relatives, who banished him from the family house.46 Several decades later, Lady Dufferin was struck by the fact that at a large official dinner given by the outgoing viceroy, “Some native gentlemen who cannot eat with us sat in another room till dinner was over.”47

Whatever their effect on social interactions, the memsahibs played a preeminent role in the garden history of British India in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. With a house full of servants, husbands on tour or shut up in their offices, and children sent home to attend school from an appallingly early age, time and loneliness often hung heavy upon them. “Nearly unmitigated ennui is the lot of the majority of luckless women in India,” lamented Emma Roberts.48 Gardening offered some diversion for those able to brave the heat. We have already seen the hand of Lady Munro in the gardens at Guindy in the 1820s. A sisterhood of gardeners followed in her wake, and many left memoirs and letters that detail this role. Most were motivated by a desire to replicate home as much as possible, and often this meant replicating English gardens and growing, or trying to grow, English flowers. To an extent, indeed, one can divide them and their consorts roughly into two groups: those determined to make their gardens a little corner of England (in particular, “their” corner of England) and those more open to the tropical flora around them.

Among the latter, myriad variations were possible. Some combined English design with indigenous plantings. Mrs. Sherwood, writing in 1805, referred to Dr. Anderson’s house in Madras as built in “a garden, beautifully laid out in the English fashion”; it abounded, however, “with trees and shrubs and flowers, such as are not known in Europe except in conservatories and hot-houses.”49 James Forbes suggests something similar in the description of the garden he laid out at Baroche, in Gujarat: “I formed it as much as possible after the English taste, and spared no pains to procure plants and flowers from different parts of India and China: it contained several large mango, tamarind, and burr trees, which formed a delightful shade; besides a variety of smaller fruit trees and flowering shrubs. . . . Shade and water were my grand objects; without them there can be no enjoyment of an Indian garden.”50 Maria Graham, too, was quite delighted with her hybrid garden in Bombay, with its walks made of ground-up seashells rather than gravel. There were chunam seats under spreading trees and “flower-beds filled with jasmine, roses, and tuberoses, while the plumbago rosea, the red and white ixoras, with the scarlet wild mulberry, and the oleander, mingle their gay colours with the delicate white of the moon-flower and the mogree.”51

Then there were the “white Mughals,” relics of an earlier age who had married Indian women and adopted Indian lifestyles and Indian gardens to varying degrees: the Kirkpatricks, Palmers, Ochterlonys, Metcalfes, Frasers, and Gardners, among others. To Colonel William Linnaeus Gardner, an American Loyalist, India was more “home” than England; he had married a Muslim princess and after an active military career settled down on his estate at Khasganj in northern India. Gardner came by his middle name as the godchild of the great botanist and, as Fanny Parks notes, was himself “an excellent botanist and pursues the study with much ardour.” The garden at Khasganj was “very extensive and a most delightful one, full of fine trees and rare plants, beautiful flowers and shrubs, with fruit in abundance and perfection; no expense is spared to embellish the garden.” Since the Begum, his wife, and other women in his family observed purdah, there was also a walled zenana garden exclusively for their use, a “pretty garden” with a summerhouse in the center and fountains. The women and girls were fond of spending time out of doors, delighting especially in swinging under the large trees during the rains.52

Hybridity was common in British gardens during much of the Company period: “a pleasing hybridity,” mingling “Eastern exoticism with European familiarity.”53 Garden houses looked to English parks, with their emphasis on trees and water and expansive grounds, for inspiration, but the trees and shrubs were of necessity tamarinds and palms and mangoes rather than oaks and elms and ash, and the lakes closer to tanks. In areas of the north, Mughal influences appealed, offering quiet seclusion and a sense of order as at Khasganj. Even the walled gardens of Peshawar in the shadow of the Hindu Kush had an “unmistakably English air about them” to the eyes of Montstuart Elphinstone, thanks to familiar plants and flowering fruit trees.54 As the garden house yielded to the bungalow, however, gardens came to reflect both the altered character of the British population and changing horticultural fashions at home, with the greater emphasis on flowers and, where possible, English flowers.

The bungalow was itself a quintessential architectural hybrid. Both name and structure were of Indian origin, but Europeans put their own distinctive stamp on them. The Bengali prototype was a simple village hut, single-story, rectangular in plan and with a raised floor. The roof was thatched or tiled and generally extended over the verandah, supported on rough-hewn posts. The classically inspired mansions with their Palladian facades that had so entranced visitors to Madras and Calcutta were not really well suited to Indian climates, no matter how beautifully polished their chunam-coated exteriors. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, these were superseded by brick bungalows, varying in size and elaboration but based on a similar module.55

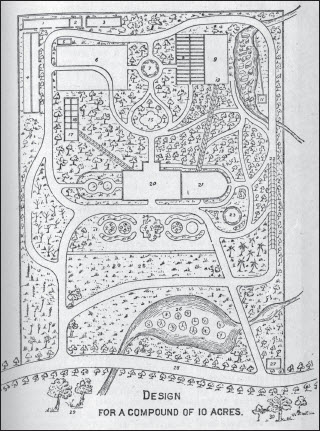

Throughout British India—and, indeed, across the empire—bungalows served as the building blocks of European life, both civil and military.56 The typical station would be set well away from its native counterpart, with streets laid out in straight lines and bordered with freestanding bungalows flanked by gardens in the middle of walled or hedged-in compounds. This contrasted with Indian houses that tended to be built around an interior courtyard garden— it was as if Indian houses were turned inside out. The size of the compound and elegance of the bungalow depended on the rank of its occupant; higher ranking officials enjoyed spacious enclosures of three to ten acres of lawn and garden (Fig. 10). A gravel path led up to a colonnaded porte-cochere—ideally high enough for an elephant to pass under—extending out from the deep verandah that encircled the house on all sides but the south and provided protection against both sun and rain. Path, verandah, and portico were lined with flowering shrubs, masses of potted plants, and climbers on elaborate trellises. The invaluable film footage in the BBC documentary series The Lost World of the Raj shows row upon row of potted plants on verandahs and along drives during the last colonial generation, as do countless photographs of bungalows spanning the century before independence (Fig. 11). Iris Portal’s dominant memory of the Delhi of her youth as daughter of the governor of the Central Provinces was the ranks of little red pots filled with chrysanthemums. Exiled to boarding school in England like so many colonial children, she missed India terribly; she remembers the joy of returning to Delhi at last and seeing the mums in their pots and thinking, “Ah! I’m back!”57

Fig. 10. Croquet on the Lawn

[Courtesy of the National Army Museum, London]

Fig. 11. Vizianagram, 1889

[From Charles Allen ]

The verandah was also the rare space where Indian and European met: here tailor, vendor, and craftsman displayed their wares or plied their trades. Larger towns were sure to have a club—European members only, with garden, tennis courts, and croquet lawns—as well as a church and a few European shops, stocked with tinned meats and preserves and chintzes. Indian bazaars, colorful as they might be, stayed in the native town. In small stations in the mofussil, the back of beyond, where Europeans were few, the bungalows might be very simple, but they were still removed from Indian settlements and they still had their gardens, however struggling.

Military cantonments, having long since outgrown the original forts, adjoined the larger colonial enclaves; in some cases they were the main raison d’être for a British presence. In these camps British troops lived separately from the larger contingents of Indian levies, but both were commanded by British officers. The officers were housed in bungalows similar to those of civilians, while British Other Ranks (BOR) lived in barracks and Indians in rows of tents, usually concentrated in the no-man’s-land between the native city and the Europeans. In time, cantonments added messrooms, officers’ clubs, racecourses, polo fields, wide green maidans (parade grounds), garrison churches, and prisons. If the bungalow was a “stationery tent,” the cantonment, adapted from the peripatetic government of Mughal rulers, was a “petrified military camp.”58 And yet the cantonment near Baroda reminded Bishop Heber of nothing so much as “one of the villages near London,” with its small brick houses, adorned with sloping tiled roofs, trellises, and wooden verandahs, “each surrounded by a garden with a high green hedge of the milkbush.” Gay and pretty as was the effect, the practical bishop wondered if the thatched roofs and deep enveloping verandahs of “up-country” bungalows might not be more appropriate to the climate. Edward Lear also found the cantonment of Monghyr on the Ganges decidedly English in layout: long streets, broad and well kept and traced at right angles, named Queen Street, Victoria Street, Albert Street, Church Street, and the like. Houses stood detached in “nice gardens in which are no end of all possible kind of vegetables, and often delightful flowers.”59

Ironically, in view of later history, some of the finest cantonment gardens were in Cawnpore (Kanpur). Cawnpore was, to Emma Roberts’s surprise, “an oasis reclaimed from the desert.” Its bungalows, their verandahs supported by Ionic columns, were situated picturesquely on high banks overlooking the Ganges, as Lady Amherst had noted, with extensive gardens of fruit trees overshadowing “a rich carpet of flowers which charms the senses by the magnificence of its colours, and the fragrance of its perfumes.” Military men were clearly no less keen gardeners than civilians, perhaps bearing out Winston Churchill’s dictum that war and gardening are the normal occupations of man. Furthermore, gardens were embraced as wholesome distractions for the Other Ranks, urged on an often bored and lonely white soldiery as an alternative to drink: “The men are given seeds, and encouraged to grow vegetables and flowers, as the life of a garrison gunner in an Indian fort is a very dull one.”60

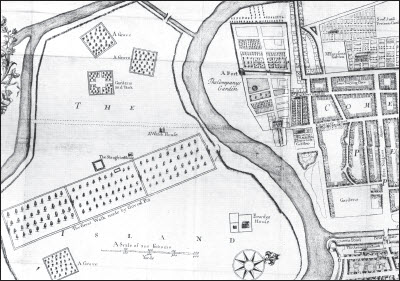

Nevertheless, the garden was usually woman’s domain. Mostly she relied on the services of a mali to supervise the actual work (Fig. 12), although Maud Diver, outspoken chronicler of the Raj, maintained that if Englishwomen had a “knowledge of the ways and needs of plants” and got out in the garden “under an Indian sun,” it would prove a “certain passport to the respect and admiration of the mali, and an excellent safeguard against his simple wiles”—and avoid the embarrassment of cabbages being planted near the front drive.61 Malis were part of every household staff, frequently drawn from the ranks of poorer Brahmins. In Assam, however, Naga malis shocked the wife of a resident by gardening in the nude. She gave them each a pair of bathing trunks “in an effort to inculcate decency,” but abandoned the idea when she found them using the garments as turbans. The mali as head gardener was assisted by a large staff that might include convicts. As late as the early 1940s the political agent at Udaipur lived in a palace with a splendid garden in which “50 prisoners in fetters weeded the lawns and the five grass tennis courts.”62 Mostly, though, labor was so cheap that one didn’t really need convicts—a scene in The Lost World of the Raj shows groups of Indian women cutting grass by hand. For grand events such as imperial durbars (ceremonial occasions) that needed instant greenswards, grass would also be planted by hand, blade by blade.

Fig. 12. Mali, c. 1840

[From Leopold Von Orlich, Travels in India, 1845]

Every morning the mali was expected to rise early and bring in a bouquet of cut flowers and a basket of fruits and vegetables for the memsahib’s table. It was a standing joke that one could get along perfectly well without a garden, with all its mud and snakes and insects, as long as one had a good mali. As Lady Dufferin put it, “The proper and healthy thing to do is to have a gardener but no garden—his duty being to provide you with flowers at your neighbours’ expense, so that you always have as many as you possibly can want, and are spared the disagreeables incident to growing them for yourself.” She adds, “I did not invent the system.”63 Whatever the “disagreeables” attendant on gardens in India, however, most expatriates were determined to forge ahead.

How Does Your Garden Grow?

Fortunately the Victorians were an instructive lot. Garden books, journals, and nurseries mushroomed in the nineteenth century to feed an ever-growing appetite for guidance. At times gardening took on attributes of a bloodsport, so fierce were the debates between partisans of different styles. The rage for bedding-out—starting tender plants in greenhouses and then setting them out in neat beds in patterns that resembled carpets—dominated the mid-century. This provoked a vehement reaction in the name of “naturalism,” spearheaded by William Robinson and Gertrude Jekyll. They favored hardy perennials or semiannuals set out in herbaceous borders, along with rock and water gardens drawing on the many exotics that could adapt to the English climate without coddling. At the same time, some garden gurus promoted a return to the formalism of Italian gardens with their statuary, terraces, and topiary. Manuals devoted to gardening in India remained largely apart from these squabbles, only distantly reflecting the changing fashions. One, dating from 1872, approved the rather garish color schemes typical of carpet bedding, but of course in India the plants had no need to be started in hothouses. A later manual recommended William Robinson’s English Flower Garden “as a reward once one has mastered the abc’s” of gardening, declaring, “it is the most instructive book in the world in English.” Agnes Harler, author of The Garden in the Plains (first published in 1901), had also clearly absorbed her Robinson and Jekyll, offering chapters on rockeries and water gardens. She suggested that a formal garden was best suited for very small compounds without room for wide lawns or spreading trees; however, she cautioned against herbaceous borders, noting that they are ill-suited to India’s lower elevations, where only a few perennials do well and even these refuse to bloom all at the same time to produce the desired color effects.64

The most popular manuals on gardening in India went through many editions and covered the whole gamut of topics.65 They provided detailed chapters on soils, temperatures, manure, watering, drainage, tools, growing from seed, grafting, pruning, transplanting, potting, kitchen gardens (best kept out of sight), noxious insects, lawns, and conservatories, along with designs for flowerbeds adapted from England and the continent. They advised how to create a spacious feeling even in a modest compound (mass shrubs and strongly colored flowers farther from the house; keep the garden simple and uncrowded) and stressed the importance of making sure that the view from the spare bedroom wasn’t onto “decaying cabbage stalks or servants hanging out the wash”—plant a little lawn under the windows with a bed of cannas or a flowering shrub or two, or a screen of climbers “to hide backyard activities.” One of the most popular offered plans for larger or smaller spreads that were simply English plans adapted only slightly to Indian conditions (Fig. 13).

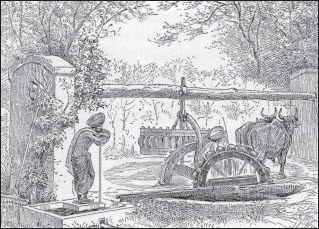

Manuals were also full of advice about how to grow English garden plants. Northern India, where the bulk of Europeans were stationed, presented particular problems because of heat and aridity: gardens had to be watered during many months of the year from a well, the “life-source” of the garden. “Morning and evening the great cream-coloured humped bullocks labour up and down an inclined plane,” wrote Edith Cuthell, wife of an official in Lucknow, “drawing up the water in a kind of square bag made of the skin of one of their deceased relatives,” which was emptied into the runnels irrigating flowers and vegetables.66 In the driest of times, the bullocks plodded back and forth all day (Fig. 14). During the monsoons the problem was reversed: gardens were turned into the bogs that Lady Dufferin so abhorred. Manuals proposed raising beds two inches above the grass to avoid flooding, but standing water in gardens was a perpetual breeding place for mosquitoes. When Constance Villiers-Stuart tried to impose an English plan of flat paths with raised herbaceous borders on her garden, she was overruled, quite rightly, by her mali, who pointed out the obvious fact that in an irrigated garden, the walks must be raised for water to run under them, just as the Mughals had done.67

Fig. 13. Garden plan for gardeners in India

[From G. Marshall Woodrow, Gardening in India, 5th ed., 1889]

One of the most encyclopedic manuals for the memsahib was The Complete Indian Housekeeper and Cook by Flora Annie Steel and Grace Gardiner. The book is written in the no-nonsense voice of an English games-mistress. It is dedicated “to the English Girls to Whom Fate may assign the task of being house-mothers in our eastern Empire.” Chapter XI, on gardening, follows a brief one on dogs. The authors take a dim view of “native gardeners,” who have no real sympathy, they claim, for flowers and must be trained to obey orders “and nothing more.” While one horticultural writer maintained that “there is no branch of gardening in India that is more overdone in the plains than pot plants” and that there is “scarcely a house or compound that is not belittered with far too many poorly kept and untidily arranged flower pots” taking up altogether too much of mali’s time,68 Steel and Gardiner were all for pots and hanging baskets. “Nothing makes an Indian house look so home-like and cheerful as a verandah full of blossoming plants, and hung with baskets of ferns,” they declared, adding, “Silent as flowers may be in complaint, they are eloquent in their gratitude, and their blossoming service of praise will make your home a pleasant resting place for tired eyes. And how tired eyes can be of dull, dusty ‘unflowerful ways,’ only those can really know who have spent long years in the monotonous plains of Northern India. There, it seems, the garden is not merely a convenience or a pleasure, it is a duty.” To back up their exhortations, they insisted that with proper manure and leaf mold almost anything could be grown.69

Fig. 14. J. L. Kipling, The Persian Well

[From Beast and Man in India, 1891]

But could it? That was the problem for those for whom the symbol of home was an English garden. Emily Eden spent more than five years (1846– 52) in India as hostess for her bachelor brother, Governor-General Lord Auckland, and kept a journal of a long official tour. It begins and ends with nostalgia for the gardens and lawns of home, for Greenwich and Kensington Gore.70 As Eden herself discovered, it was possible to grow many English flowers in India; it all depended on geography and season. In Sholapur, in the Deccan, George Roche remembers his mother’s garden: “[She] planted English seeds—sweet peas, petunias, phlox, balsam and clarkias, which, by Christmas time were in full flower. . . . The display of blooms could not have been bettered in any English garden.” Sholapur stood a thousand feet above sea level, but even at that altitude her success was unusual and made her the envy of the other ladies of the station; her son attributed it to manure from their own stables.71 The North-West Frontier Province, isolated though it might be, was far better suited to English preferences, thanks to both latitude and altitude. Posted to the garrison town of Rawalpindi, an official couple lived in a “charming house, surrounded by a garden where roses climb up trees and hang from their branches and mignonette and sweet violets pervade the air with their perfume.”72 Peshawar offered a similar climate: “Here we are, right on the Frontier,” exclaimed Lady Reading, wife of the viceroy, in 1922, “and it is the first place, strange to say, that has reminded me of England since I landed in India. Such green grass and tall trees. . . . The garden here [at the residency] is heavenly with rows of orange trees in full bloom, beds of pansies and a rose-garden with such Maréchal Niel!”73

Even lowland India does, in fact, have a winter. As Emma Roberts noted in 1836, “The climate all over India, even in Bengal, is delightful from October until March . . . ; summer gardens glow with myriads of flowers, native and exotic. . . . This is the gay season.” Even if a true herbaceous border was not possible at low elevations, a border of mixed annual flowers made a good substitute. Most cold-season flowers sown in late September or early October would bloom in the winter months, and planning such a garden was “one of the joys of an Indian year.”74 The author Rumer Godden’s mother would have heartily agreed. As soon as the rains were over, she began to plan her garden in Bengal. The packets of seed of “precious English flowers” were sown in shallow earthenware pans set in little bamboo houses on stilts. Every evening their mat roofs were rolled back so that the little seedlings could enjoy the cool air and morning dew. When the sun grew too strong, the mats were put back again. The mali watered the tiny plants by dipping a leaf in water and shaking it over the pans, explaining that even the finest nozzle on a watering can would give too strong a jet of water. When they grew big enough, the pansies, dianthus, stocks, sweet peas, and sweet sultans would be transplanted into the flowerbeds or into the big pots set along the verandahs.75

Lady Beatrix Stanley made something of a study of what flowers would grow in India “to remind one of home.” In the south annuals were limited mainly to large-flowered zinnias, coreopsis, gaillardias, phlox, and petunias, all of which could be planted in the open, or, if space was lacking, in pots. Salvias, cosmos, and various sunflowers also did well, although “roses are of no use in Madras”—in contrast to New Delhi, where they could hold their own with the best of England.76 At Agra, Baron von Orlich, a Prussian officer fighting the Sikhs alongside the British, observed that only after the monsoon did flowers reach their full perfection. Then the air was filled with the balsamic perfume of roses, violets, and myrtles. An early December morning in Dinapur seemed to Edward Lear “exactly like of a lovely autumn or even June, morning in England; zinnias, balsams, and roses included.” In the plains, annuals such as phlox and nasturtiums, pansies and corn-bottles, sunflowers and daisies did indeed grow wonderfully fast—“In India the gardener has very little waiting to do.”77 Among the tea planters in Assam there were also many passionate gardeners. One of them has left a moving memoir of her twenty years as the often frustrated and alienated wife of a planter. She describes how the hot weather lessened in early October: “There was a new smell and we walked out into a thick white mist and knew the cold weather had begun; golden days when the compound filled with English flowers mixed in with mimosa and poinsettias and the vegetable garden gave us salads and pineapples.” Evenings were at last cool enough for fires and buttered toast in front of them. At the club, gardeners competed to see who could bring in the first sweet peas or cauliflowers.78

For Edith Cuthell, too, the world came back to life in October. “For us, Westerns, the Indian year has, as it were, begun. Life is once more endurable; the rains and the hot winds have ceased.” Her My Garden in the City of Gardens, first published anonymously in 1905, is one of the most complete garden chronicles, following the seasons in Lucknow. Needless to say, the bulk of it is devoted to the cold weather and her efforts to grow annuals from seed, first in pots on the verandah, then in beds: pansies, sweet peas, stocks, nasturtiums, balsams, verbenas, heartsease—the whole repertoire. The garden reaches a climax in January and February; by April the English flowers and vegetables have been “scorched by the brand of the blinding heat” and by June she is off to the hills. But, oh, the joys of those winter months! Her rapturous paean to the violets she coaxed into blooming is quoted in almost every work on British life in India: “My violets are in bloom! You cannot think how one treasures out here the quiet little ‘home’ flower, buried in greenery. . . . Dear little English flower!” They demanded more care than all the “lurid tropical flowers” put together, kept always in their pots out of the direct rays even of the winter sun and watered by the mali carefully trickling the stream through his fingers: “for are they not the memsahib’s most cherished plants?” She was almost as ecstatic over her bed of watercress, “a pearl of great price,” which with much care could be kept going all through the cold weather, along with expatriate vegetables and fruits: cauliflowers, turnips, carrots, asparagus, tomatoes, strawberries. Then there were the roses. Roses might be the “real flower of the East,” but they cannot stand the tropical sun and in the plains bloomed only in the cold weather.79

It was widely believed that the most reliable seeds came from England, ordered from catalogs or brought by friends. Even then, it was a case of “Darwinian survival”—many of Cuthell’s seeds sent out weeks earlier in tins arrived “mildewy and spoilt.” European plants required a constant succession of fresh seeds, “for, unless the cultivators of distant places exchange their seeds with each other, foreign productions soon dwindle and die away.”80 Firms in Calcutta or Poona and botanical gardens sought to fill the growing demand for such plants. Emma Roberts gives a long account of Deegah, a remarkably extensive farm and nursery near Patna on the Ganges where a Mr. Havell raised for sale all manner of livestock (including English breeds), plants, and fruit trees, and offered warehouses full of dry goods, provisions, furniture— all that a well-heeled clientele might want. The gardens “contain an immense profusion of European flowers,” carefully tended by native “mallees” under the supervision of Dutch and Chinese gardeners. Visitors were invited to walk in the gardens, as Roberts did, observing that “its English flower-beds [show] how bright a paradise an Indian garden may be made by practiced hands.” Inevitably, Havell’s prices were high in spite of government subsidies, but even so Roberts doubted Deegah would outlast Havell’s death.81 And even Havell’s gardeners, “men of science and practical knowledge” though they might be, would not have been able to grow spring bulbs in the Gangetic plain. Raleigh Trevelyan’s parents brought with them to Gilgit daffodil bulbs specially sent out from England: At 3,000 feet Gilgit was high enough and far enough north for bulbs to flourish, just as some varieties did fairly well in the Nilgiri Hills in the south, although they rarely flowered after the first year since the weather was simply not cold enough for the dormancy all bulbs require.82

The lawn, that sine qua non of any proper English garden, presented the greatest challenge of all. Without a lawn, the “centre of social life,” how could one hold garden parties? Or play croquet or badminton or cricket? It was a particularly precious thing in hot countries, as Lady Dufferin observed. Grindal’s Everyday Gardening in India declared that the lawn should be “the principal general feature of the garden, ” adding, “The more wide and unbroken the lawns, the more beautiful and restful the effect. A beautiful lawn well may be compared to a beautiful carpet, without which any scheme of furnishing is ruined”—an interesting analogy in view of the close relationship of Mughal gardens and Persian carpets. Another guide proclaimed the lawn “the heart of the garden and the happiest thing that is in it.” It was the setting for flowering shrubs and dwarf flowering trees as well as a few formal beds of annuals, although not too many. A heading in Mrs. Temple-Wright’s highly popular Flowers and Gardens in India: A Manual for Beginners reads “A Lawn, an absolute necessity.” Even if you can’t manage a garden, she insists, “make only a lawn, or grass-plot, and this, with cleanly kept soorkee [brick dust] paths, and a few plants in pots, will be sufficient to keep up the degree of harmony you intend to maintain between the outside and inside appearance of your abode.”83

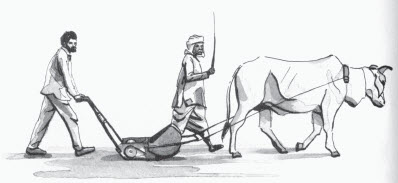

HOW THEN TO ACHIEVE this oasis of greenery? In 1836 Lord Brougham had arranged to have English turf brought out by boat for his chateau at Cannes, “stupéfiant les Cannois en créant d’immenses pelouses toujours vertes” [amazing the people of Cannes by creating immense lawns forever green], but this was hardly feasible in India. Stationed in Gujarat and the Koncan in the second half of the eighteenth century, Forbes had bemoaned the fact that the “great desideratum” of a “verdant lawn” seemed an impossibility: “A tropical sun would not admit of it in the fair season, and during the rainy months the rank luxuriant grass more resembles reeds and rushes than the soft carpet bordered by an English shrubbery.”84 Seasoned gardener though she was, Edith Cuthell didn’t even bother with a lawn in Lucknow, considering it far too expensive a luxury for any but high functionaries “who dwell more permanently than ourselves in Government Houses and the like.”85 Nonetheless, she was an exception. All the garden books provided detailed recipes for preparing the soil and tending the grass, sowing not the finely textured English varieties but the coarser, wiry Indian doob. Adapting the English formula of alternately rolling and mowing, Temple-Wright exhorts the reader that “the more like velvet you wish your lawn to appear, the more you must Mow, Sweep, Roll, Water”86 For Steel and Gardiner the advice was simpler and sterner: “Make the grass grow.”87

The maidan, at the heart of most British towns and cantonments, was the lawn writ large. The East India Company trader William Finch described the maidan in Surat early in the seventeenth century as “a pleasant greene in the midst whereof is a maypole.”88 It had its origins in the parade ground but served also as a public park and playing field. In the course of the nineteenth century British authorities added more public parks: Elphinstone Gardens, Horniman Circle, and Victoria Gardens in Bombay (see Pl. 2); Eden Gardens in Calcutta, and the “club-strewn” Lawrence Gardens in the heart of British Lahore.89 In Lahore, too, they undertook the restoration of the lovely Shalimar Garden that had been laid out by Shah Jahan in 1642 but largely destroyed under Sikh rule. As was so often the case with their “restorations,” the result was more British than Mughal: they cut down the beautiful cypresses and mango trees that were the central feature of the lowest level and transformed the terrace into flowerbeds.90

The success or failure of lawns depended on season and place. The monsoon itself could turn the landscape green: “The whole face of the country is covered with a lovely carpet of grass just like the meadows at Richmond,” wrote a Mrs. Terry from Bombay in the mid-1840s. Unlike Richmond, hyenas still came out at night and killed her ducks, alas.91 Assiduous gardeners could achieve some success, creating “a lawn quite English-looking,” as Augusta King, an official’s wife, noted in Morabadad. And when she heard the sound of a mowing machine, she wrote, “I could almost fancy we were in England”92 (Fig. 15). Such machines were expensive in India, however, and hardly necessary in a country where labor was so cheap. In Poona, “children rolled and crawled and played on the lawn that was of almost English thickness,” and in Peshawar Elphinstone found fields covered with a thick, elastic sod, that perhaps was never equaled but in England.” Returning home from the misery of school in England to their father’s plantation in Bengal, Jon and Rumer Godden were ecstatic as they rumbled through the great wooden gates arched with a canopy of bridal creeper and caught the first glimpse of what they, in fact, considered their real home: “Lawns spread away on either side, lawns of unbelievable magnitude after the strip of London garden we had grown used to.”93 This was December—“the balmy noon of a December day”—when lawns and gardens everywhere were at their dazzling peak. With the first blasts of summer, lawns turned brown and English flowers wilted and died. “They struggle so gallantly to pretend that they are happy, to persuade you that this is not so very far from England; and they fail so piteously. They will flower in abundant but straggling blossoms; but the fierce sun withers the first before the next have more than budded. . . . It is a loving fraud, but a hollow one.”94

Fig. 15. Olivia Fraser, Lawn Mowing

[From William Dalrymple, City of Djinns, 1993]

Other obstacles plagued the gardener. In Karachi, apart from the scorching temperatures, the soil was almost pure sand; if one dug deep, a “saltish damp oozed up, destroying all plant roots. All you could hope for was a few palms, casuarinas and oleanders.”95 The holy city of Benares swarmed with sacred bulls, who laid waste to English gardens. The only effective remedy was to yoke them and put them to hard labor for a day or two, “which so utterly disgusts them with the place that they never return to it.”96 Lord Valentia probably exaggerated when he claimed that one couldn’t have trees in the English quarter of Benares “unless you choose to be devoured by mosquitoes.”97 Dacca, in East Bengal, was considered a punitive military posting, not least because of its haunted houses and gardens.98 More generally, white ants were the scourge of India, “the vilest little animals on the face of the earth.” They ate their way through walls, through wooden beams, through furniture, through carpets, mats, and chintz. When they attacked the roots of trees and plants, they killed them in a day or two. In the garden the solution Fanny Parks recommended was a solution of assafoetida, but the ubiquitous pots also offered protection.99 Then there were the snakes—it was a good idea to lay a carpet on the lawn before guests moved out to the garden after dinner, since snakes like to lounge on the warm ground after sunset.100

All these inconveniences paled before the impermanence of expatriate life. As soon as one was settled in one station and began literally to sink roots, one faced transfer to another outpost, sometimes in a very different part of the country. This meant that garden design counted for less than just getting beloved flowers to grow. The Steels moved fifteen times in sixteen years. Since they spent three years in one station and two in another, the rest of the postings were very brief indeed. “We are but birds of passage in India,” lamented Anne Wilson, another civilian wife, “and have to build our nests of what material we can find.” They might cultivate gardens with plants they would never see open. Some were too discouraged to exert themselves or to settle for more than a few halfhearted shrubs at the doorstep. Nonetheless, even the birds of passage were reminded that they could still spruce things up a bit before they moved on: cut the grass, trim the shrubs, repot the plants, and maybe even sow some annuals.101 All those potted plants had the virtue of being portable and were often transported from post to post or on the annual transmigration to the hills (see Chapter 3).

If gardening in India was in the end an “act of faith,”102 the most successful gardeners learned to temper their longing for English flowers with a leavening—one might almost say a masala—of indigenous plants. In some cases it was by necessity, in others by preference. Steel’s husband discovered in his planting of roadside gardens in the Punjab that only indigenous plants would keep on growing, while European ones tended to peter out after a few years. The contrast was marked in her own garden on a summer’s day: “The English flowers meet the sun’s morning kiss bright and sweet as ever, but by noon are weary and worn by his caresses. Yet there were heaps and heaps of Oriental beauties ready for it.”103 Beatrix Stanley advised “all who care for gardening and who try it in India, to grow as many of the native plants, shrubs and creepers as possible, for although they do not always remind one of home, yet unless a few of these are grown one misses many lovely and interesting plants.” Her view was evidently shared by Rumer and Jon Godden’s mother, who added to her “precious English flowers” and pots of budding chrysanthemums abundant plantings of hibiscus and oleanders, bougainvilleas, plumbago, and a hedge of poinsettia. Just so, Edith Cuthell’s garden grew “flowers of home” alongside tropical flowers, shrubs, fruits, and trees, “lurid” though they might be.104

Manuals sensibly suggested combining the best of both worlds wherever possible: masses of annuals along with “flaming tropical flowers” in the hot months.105 There were also instructions for creating a moonlight garden, the quintessential Indian form. It would feature pale yellow or white flowers which don’t close up at night, “and since there is a theatrical quality about moonlight in the tropics, these flowers should be given as ‘stagey’ a setting as possible”—grouped around a tank or at the end of a stretch of grass. Climbers look “more ethereal” if attached to a wire mesh support or a pergola behind the flowerbed.106

Practicality aside, some reveled in tropical flora, while others detested them. Forbes might talk of laying out a Jardin à l’Angloise, a garden laid more or less “in the European taste,” but he stocked it with the Indian flowers and creeping vines he adored.107 Emma Roberts was more a Romantic than an Orientalist, but she shared Forbes’s sensual appreciation of Indian nature. One of her most memorable experiences was a stay in the house of the Collector at the small civil station of Arrah, in Bihar, not far from Patna. The “spacious mansion,” the cages filled with “brilliantly-plumed birds,” the immense chameleon, the exquisite view from the balcony over “bright parterres of flowers,” a small lake with its “calm and silvery waters,” against a glorious background of forest trees, “bearing the richest luxuriance of foliage”—all calculated to inspire bursts of enthusiasm in the weary traveler. She conjured up images of enchanted castles, of “youthful visions of the splendid retreat of the White Cat, the solitary palace of the King of the Black Islands, or the domicile of that most gracious of beasts, the interesting Azor.” Walking at dusk in the garden, which blended both Indian and European flowers, she came to a large tank in the middle of which was an island covered with lustrous flowering shrubs with innumerable small white herons daring in and out of the foliage. A ghat or flight of steps led down to the tank and opposite it a “superb tree,” a “monarch of the forest . . . held in great reverence by the Hindoo population” (a peepal tree, perhaps?), gave shade to the graceful forms of natives filling up their water-pots. The “crimson splendours of a setting sun . . . lit up the whole scene with hues divine.” Imagine her bafflement when she later met with many persons, presumably compatriots, who were familiar with this “glorious landscape” but spoke of it with indifference, when to her, even in weak health and much fatigued, it appeared “one of the loveliest spots of earth on which my eyes had ever rested.”108

Roberts’s contemporary Fanny Parks offers a glowing and only slightly more down-to-earth description of her own extensive garden at Allahabad, illumined for the Hindu festival of Dewali. Like Forbes, she had her own bower, a favorite retreat on the banks of the Yamuna, “which is quite as beautiful as the ‘bower of roses by Bendameer’s stream.’” The garden was full of luxuriant creepers and climbers forming a canopy over her bower, exuding delicate fragrances, attracting hummingbirds and butterflies. Blossoms hung from surrounding trees and nymphaea floated on the water. Among her favorite plants were two species of sag [spinach], the koonch [?], several brilliant hibiscus, and a salvia. The salvia was tended with particular care in view of the well-known adage, “Cur moriatur homo, cui salvia crescit in horto?” (Why should a man die who has salvia growing in his garden?). She writes about her flowers with “a tremulously lyrical ecstasy,” evoking Thomas Moore’s Oriental romance, Lalla Rookh, with her “plaintive apostrophe” to the “sorrowful nyctanthes” (Nyctanthes arbor-tristis), the night-flowering jasmine: “Gay and beautiful climber, whence your name of arbor tristis? Is it because you blossom but to die? With the first beams of the rising sun your night flowers are shed upon the earth to wither and decay.” She does not mention a single English flower, noting that in the bouquet presented to her every morning by her mali “many were novelties to an European.” Parks had taken to India like a duck to water, and yet nostalgia could steal upon her unbidden: cooped up in her stifling house during the heat of the rains, there were moments when even she longed to walk among the wildflowers of home: “Here we have no wild flowers; from the gardens you procure the most superb nosegays; but the lovely wild flowers of the green lanes are wanting.”109

As keen students of botany, William Jones, Lady Amherst, and Lady Canning (all of whom will reappear in subsequent chapters) also took a particular pleasure in Indian flora. Lady Amherst found it a little foolish of the missionary Dr. William Carey to insist on growing plants from England in his garden upriver from Calcutta in a “climate nature never intended them for.” Conversely, as Lady Canning was wont to remind her friends and family back home, many of the exotics in her garden had become familiar in England as hothouse plants.110 Neither Jones nor Canning lived to return home, but a few of those who did sought to re-create something of India in England. James Forbes brought back more than two hundred seeds from Gujarat for his garden at Stanmore Hall, in the midst of which he placed an octagonal temple filled with Hindu sculpture. In his glass conservatory he succeeded in growing many of the flowers celebrated by Indian poets: the crimson ipomea, the “lovely Mhadavi-creeper, . . . the changeable rose (hibiscus mutabilis), the fragrant mogree, attracting alhinna, and sacred tulsee.” At Daylesford Warren Hastings, too, tried to propagate the plants he had most appreciated in India. Drawing on meteorological data he had collected in Calcutta, he designed a stove house intended to provide the right environment for his lychees and custard apples. His attempts to cross Indian animals, such as the shawl goat from the Himalayas, with English breeds were less successful. In other respects, to be sure, Hastings’s estate was more typical of the parks of his neighbors, with extensive lawns of carefully manicured grass, beds of flowers, carefully arranged clumps of trees, and a grotto.111