G

AZING OUT upon Delhi in 1838, Fanny Parks beheld a vast panorama of gardens, pavilions, mosques, and burial places. But the “once magnificent city” was now “nothing more than a heap of ruins.”1 When the British became masters of Delhi in the opening years of the nineteenth century, they had found it a city of gardens and a city of ruins, the two often intertwined. The plains were dotted with crumbling walls of palaces and tombs, often cannibalized by later conquerors, and even more with the faded, weed-infested gardens in which earlier kings, nobles, and saints had once taken their pleasure or their solace (Fig. 45). The last Mughal emperors were of a piece with their diminished surroundings, eking out a threadbare existence until the dynasty finally collapsed in wake of the events of 1857–58. The British were then left to decide just where the city fit into their imperial agenda. The more the Mughals receded into history, the safer—and more tempting—it became for the Raj to style themselves as their heirs in everything from gardens to rituals.

Fig. 45. The Ruins of Delhi, with Humayun’s tomb in the background:

from an early sketch by Capt. R. Elliot, RN

[From Charles Lewis and Karoki Lewis, Delhi’s Historic Villages, 1997]

Delhi Before Shah Jahan

Unlike the presidency towns of Madras, Calcutta, and Bombay, Delhi was not a British creation. Its serial incarnations—“as numerous as the incarnations of the God Vishnu”—stretched back into protohistoric times, from Indraprastha to Shahjahanabad, from the era of the Mahabharata to the glory years of Mughal rule.2 The city lies within a large triangle, bounded on the east by the river Yamuna and on the west by a series of jagged ridges running north and south. Whoever held Delhi, tradition had it, held India. Neither the ridges nor the river provided much protection; the “bride of peace was ravished” by wave after wave of foreign invaders from Central Asia, spilling through the mountain passes to the northwest onto the great plain of northern India. Some came simply to loot and massacre, others to stay and found dynasties of varying duration. In truth, foreigners dominated Delhi for so much of its history that its final incarnation as a British imperial city was hardly an anomaly.

The earliest Delhi was the semilegendary Indraprastha, dating from the Later Vedic period (c. 1000 b.c.e.). In historic times, Rajput kings were followed by a series of Muslim invaders: Turks, Afghans, and finally Mughals, descendants of Timur (Tamerlaine), who had ravaged Delhi in 1398. Most raised new cities, monumental buildings being the time-honored way to proclaim power and prestige. They chose their sites either because they seemed to be defensible (warfare was endemic) or because they might catch the northern breezes (Delhi summers are scorching). Rarely did they show any interest in conserving the works of predecessors. An exception was Firoz Shah Tughlak (d. 1388), who anticipated the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) in his concern for the preservation of the past. He brought a pillar of Ashoka to his new city of Firozabad. Already fifteen hundred years old, the pillar recorded Ashoka’s project of planting trees along the main roads of his empire, along with digging wells and establishing serais for travelers, all of which Firoz Shah himself emulated.3 The ruler also dedicated himself to protecting forests and made the first attempt to afforest the Ridge, to the north of the capital, where he maintained a hunting preserve.4

When Percival Spear reminisced that “Delhi was always a city of gardens and greenery for me, even more than of monuments,” he was thinking above all of the Mughal period, still so evident when he first arrived in the city in 1924.5 But gardens predated the Mughals, although descriptions are few and the sites ephemeral. Kingship was proclaimed through gardens as well as palaces and new urban centers. Thus ‘Ala’ al-Din Khalji (1296–1316) built gardens in the royal city of Siri, both within and around the palace and at Hauz Khas, the tank he had constructed to supply water to his city. Inclined no doubt to hyperbole and a touch of sycophancy, the great poet, musician, and Sufi mystic Amir Khusrau (1253–1325) described the Delhi of this time: “It can well be compared to the Garden of Aram in Paradise. . . . Gardens surround it for three kilometres and the river Yamuna flows nearby.”6 A midfourteenth-century Arab writer from Damascus refers to gardens extending for twelve thousand paces on three sides of the city (the fourth side was the rocky ridge with its many ravines). About the same time the poet Mutahar of Kara extolled Firoz Shah’s Delhi: “There is verdure everywhere and hyacinths, basils, roses and tulips were blooming,” while Zia-Barni, the Sultan’s chronicler, declared: “Sultan Firoz had a great liking for the laying out of gardens, which he took great pains to embellish. He formed 1,200 gardens in the vicinity of Dehli [sic]. . . . All gardens received abundant proofs of his care, and he restored thirty gardens that had been commenced by [‘Ala’ al-Din]. . . . In every garden there were white and black grapes.”7 To be sure, we must take these figures with a grain of salt, and it is unclear whether the gardens were mostly intended to produce fruit for court and market or whether some also served as places of pleasure.

That they also grew flowers, however, is implied not only by the poets’ encomia but also by the traveler Ibn Battuta’s account of the importance of flowers in funeral rituals in fourteenth-century Delhi. He describes a cemetery outside one of the city’s twenty-eight gates: “This is a beautiful place of burial; they build domed pavilions in it and every grave must have a [place for prayer with a] mihrab beside it, even if there is no dome over it. They plant in it flowering trees such as the tuberose, the raibul [white jasmine?], the nisrin [muskrose?] and others. In that country there are always flowers in bloom at every season of the year.” When his own baby daughter died while in Delhi, he carried out the appropriate rituals: on the third day after burial, they spread carpets and silk fabrics on all sides of the tomb and placed on it the flowers mentioned in the preceding passage. In addition they set up orange and lemon branches with their fruits, together with dried fruits and coconuts.8

Delhi, then, had long been a city of tombs and tomb gardens when Babur captured it in 1526 and established Mughal rule in India. Indeed, on his first tour of inspection he lists nothing but tombs, culminating with those of the most recent Lodi rulers, Sultan Bahlul and Sultan Iskander, both of which had gardens attached. Apparently they did not impress him, for, as we have seen, Babur dismissed all the gardens he found in Hindustan, lumping Muslim and Hindu indiscriminately in his blanket indictment.9 Later writers take issue with this verdict. They argue that gardens were an important part of Sultanate culture before the Mughal conquest and not as miserable as Babur suggests. In practical terms, of course, they provided food and income to their owners, but on a symbolic level they provided a foretaste of paradise, settings for mausolea and palaces, and retreats for leisure and relaxation. The Mughals may in fact have borrowed from the Delhi sultans their preference for situating family tombs in gardens, a practice that their Timurid forebears had not followed.10 Nevertheless, it seems quite likely that the gardens of pre-Mughal Delhi lacked the formal, ordered structure that typified the Mughal charbagh. Then, too, Babur’s own preference as a man of the mountains was for hillside gardens, with sparkling streams carefully straightened and channeled to run down the terraces, something that could hardly be replicated on the level plains of Delhi.11

In India riverfronts had to substitute for streams and springs, and gardens were adapted accordingly. Babur chose Agra rather than Delhi for his capital even though it was just as flat and, if anything, hotter and dustier. His very first act was to create a garden on the banks of the Yamuna for his residence—true heir of Timur, he was more at home in the open than confined within fort or palace. Members of the imperial family and notables soon followed his example, so that both shores of the river were lined with gardens during his reign (he died in 1530) and the reigns of his successors as royals and nobles vied with each other in the magnificence of their creations. As Sylvia Crowe writes, “gardens . . . were in fact open-air rooms on a lavish scale,” often with colorful tents hung with tapestries pitched on the lawn or carpets unrolled on the clover and grass. “Just as [Mughal] camps on the march were laid out as if in a garden, so their gardens served as a form of encampment.”12 Francisco Pelsaert, factor of the Dutch East India Company in Agra from 1621 to 1627, during the reign of Babur’s grandson Jahangir, noted that anyone who aspired to be someone had a garden along the river, giving the city a curiously narrow, elongated form. He listed thirty-three gardens by name, noting that the “luxuriance of the groves all round makes it resemble a royal park rather than a city.”13 A map of Agra made for the Maharaja of Jaipur in 1720 shows the banks of the river in detail, identifying the gardens depicted, including those of the Taj Mahal and the tomb of I’timad-ud-Daula, Jahangir’s powerful father-in-law.

Because land could only be inherited in rare cases, elites had little incentive to build extravagant palaces that the owners could not bequeath to their heirs but reverted at death to the crown, to be redistributed to a member of the royal family or to another noble. The same inheritance laws apparently applied to gardens unless they contained tombs. This encouraged the practice of creating luxurious pleasure gardens during one’s lifetime, gardens which, Pelsaert observed, “far surpass ours . . . for their gardens serve for their enjoyment while they are alive, and after death for their tombs, which, during their lifetime they build with great magnificence in the middle of the garden.”14

During more than a century of rule in northern India, the Mughals virtually ignored Delhi in favor of Agra and Lahore and, for a time, Akbar’s new city of Fatehpur Sikri. True, Babur’s son, Humayun, moved the capital back to Delhi for a brief period late in his life, intending to build a new palace and a new city in the time-honored tradition. The hapless ruler had managed to lose most of the territory conquered by his father before being overthrown by the Pashtun Sher Shah and forced into exile. After years as a “wanderer in the desert of destruction,”15 he at last regained his throne, only to die a few years later in a fall from the library in the Purana Qila as he was rushing to answer the muezzin’s call to prayer. Humayun had always been not only devoutly religious (as his father never was) but inclined toward mysticism; at the same time he was intensely superstitious and in thrall to his astrologers, unable to make a move without consulting the stars.16 Like most of his family, he was addicted to alcohol and opium, but unlike them he had little interest in gardens or things horticultural even though important events of his reign continued to take place in gardens as they had under Babur.17 It is more than a little ironic, therefore, that his magnificent garden tomb became the prototype for the genre itself.

Shahjahanabad

In 1638, more than a century after Humayun’s false start, Shah Jahan decided to move his capital definitively to Delhi. This may seem strange in view of the attention and resources he had lavished on the fort at Agra—and even stranger when one remembers that the Taj Mahal, the memorial to his beloved wife Mumtaz Mahal, was well underway in Agra and would be completed by the time the new capital was built. The reason given for the move was the ruler’s pique at the merchants of Agra for their refusal to allow him to open up the narrow, congested streets of the city—“irregular, and full of windings and corners”—so that stately processions with their legions of elephants could pass through.18 A Pyrrhic victory for the merchants: the rise of Delhi meant the decline of Agra.

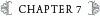

Shah Jahan entered his new city by the river gate on April 8, 1648, a day chosen as auspicious by the royal astrologers.19 Shahjahanabad was intended to outshine anything that had gone before. The emperor called upon the finest craftsmen of the day: architects and garden designers, stonecutters and carvers, masons, carpenters, and jewelers. Its fame reached all the way to Europe, thanks to the accounts of François Bernier, the youthful Venetian courtier Niccolao Manucci, and the jeweler Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, who cast an expert eye over the jewel-encrusted Peacock Throne; their reports “created the legend of the Great Mogul.”20 Measuring some four miles around, the planned portions of the city, laid out as symmetrically as the site allowed, included the Friday Mosque and other mosques, boulevards and bazaars, an elaborate system of water channels, and several extensive gardens lining Chandni Chowk, the primary artery (Fig. 46).21

Fig. 46. Panorama of the Walled City of Delhi, c. 1856

[From Anthony King, Colonial Urban Development, 1976]

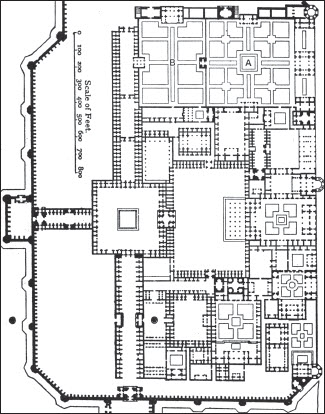

At its heart was a huge complex, the Qila-e-mubarak, the Exalted Fort, later known as the Red Fort from the red sandstone of its walls and gateways (Fig. 47).22 It was surrounded with a moat on the three sides that did not face the river and, beyond the moat, a garden “filled at all times with flowers and green shrubs, which, contrasted with the stupendous red walls, produce a beautiful effect.”23 There was in fact a succession of gardens ringing the fort: the Rose Garden in front of Lahori Gate with its adjoining Grape Garden and the High Garden before the Delhi Gate. From the principal gates one entered what was a walled world to itself, the administrative and military hub of the empire but also a center of manufacturing and commerce, and above all the residence of the emperor and his seraglio. Larger than any European palace of its time, the fort’s inner, private quarters alone encompassed an area five times that of Spain’s Escorial.24

Fig. 47. The Delhi Palace before 1857

[From Constance villiers-Stuart, Gardens of the Great Mughals, 1913]

The palace fortress was built on the banks of the Yamuna, where it could benefit from both the defenses and the easterly breezes the river provided. It represented the culmination—and endpoint—of the modular riverfront plan that evolved from Babur’s earliest gardens. Gardens occupied more than half the area of the Red Fort: “The garden is to the buildings,” reads the main inscription, “as the soul is to the body, and the lamp to an assembly.”25 Like the waterfront gardens in Agra, major pavilions and halls within the fort were constructed on terraces facing a canal on the riverfront. In front of each, was “a garden . . . of perfect freshness and pleasantness,” whose vegetation is so exuberant that it draws “a veil across the green sky and the sight is presented to the eyes of the beholder like the highest paradise.”26 Bernier describes spacious alcoves facing flower gardens, embellished with small canals of running water, reservoirs, and fountains. He was not allowed into the zenana, the women’s quarters, but he was told by some of the eunuchs that on every side the apartments opened onto “gardens, delightful alleys, shady retreats, streams, fountains.”27 The last of the series of zenana buildings on the riverfront was known as the Khurd Jahan, the “Little World.” The origin of the name is uncertain, but it may have been chosen to suggest that within were collected all the flowers and trees to make it a “microcosm of the world.”28

Most of the gardens within the fort were domestic spaces intended for the ruler, his immediate family, and their servants, private places of pleasure and relaxation but encoding their own message of dominion for all that. As absorbed with garden design as with architecture, Shah Jahan oversaw the dazzling integration of both. Because most of the pavilions were single-story and were often extended out by awnings, screens, and arcades, boundaries between art and nature, exterior and interior, dissolved. “In most of the private imperial areas, there was no strict boundary between built and open space. Space flowed into the building from the outside through the open arches—in the views that it provided of the court or garden, in the sound of birds, in the scent of flowers and trees, and through cool breezes . . . The garden was carried into the building by decorating the floors and the walls with inlaid flowers of semi-precious stones.”29 Tiny mirrors set in plaster intensified the illusion of shifting and infinitely permeable boundaries.

The two largest gardens in the northern portion of the inner palace were the Hayat Baksh (Life-giving) and the Mahtab (Moonlight)—“two separate enclosures treated in one design”30—while the southern half was devoted to the harem gardens described by Bernier.31 The Hayat Baksh was the ultimate khanah bagh or house garden, Shah Jahan’s masterpiece. A classic square measuring five hundred feet on a side, the garden surrounded a central water tank with a summerhouse in the middle, 49 silver fountains surrounding it, and another 119 bordering the four rims of the tank. The avenues extending from the tank to the walls of the garden were bisected by canals of water, also set with fountains that cast spray high into the air. At the northern and southern ends of the avenues were two more pavilions, mirror images built in marble, with porticoes opening to the east and west. They were named, appropriately, after the Hindu monsoon months of Bahadun and Sawan. The emperor’s artists decorated the southern one with paintings of herbs, trees, and flowers; water rushed in one side of the house and out the other, bringing the coolness for which its monsoon namesake was noted. Niches in the wall held gold vases filled with flowers during the day and wax candles at night, like “stars and fleecy clouds . . . lighted under the veil of water.”32

The gardens themselves were planted with flowers and fruit trees. Muhammad Waris, a court historian, declared: “A heaven-like garden in this state of flourishing has not appeared before on the face of the earth. He [Shah Jahan] took pains so that every work was the rarest and beyond computation. A variety of fresh plants and fruitful trees grew to a great height. . . . The pleasantness of the garden area . . . and the colorfulness and greenness and abundance of the narcissus and sambal and the loveliness of the flowers caused this area to be the envy of the heavens.” Hyperbole, yes, but not entirely: the accounts preserved for the construction of the palace underscore the extravagance of the Hayat Baksh and its neighboring bath.33 And added to this was their upkeep through the parched non-monsoon months. The “Moonlight Garden” was smaller and less ambitious, planted with pale flowers such as lilies, narcissus, and jasmine that would fill the night air with their fragrance.34

Ebba Koch sees the Hayat Baksh as a major innovation in the representation of Mughal imperial power. Not only was it of unprecedented size, it employed the vocabulary of art to make the garden itself an expression of Shah Jahan’s self-image as ruler of the world. Forms such as the baluster column and the curved bangla roof that had hitherto been used only for “palatial architecture of the highest ceremonial order, namely the marble jharokas [balconies] and baldachins in which the emperor appeared before his subjects,” now appeared in the pavilions of the garden. Only the emperor was allowed to use motifs of plants in art and architecture, and he did so with a vengeance. As at the Taj Mahal, flowers adorned the walls and ceilings of the garden buildings, inlaid with semiprecious stones (pietra dura), carved in marble relief, gilded and painted: “different kinds of odiferous plants and flowers and various kinds of designs and pictures so colourful and pleasing that . . . the artisan Spring . . . itself is pierced by the thorns [of envy].”35 The pictures became “virtual flower gardens” and Spring itself comes off second best to the emperor’s artists. As a metaphor of the entire palace, the Hayat Baksh “epitomized its concept as a garden.” Shah Jahan’s ever-blooming gardens symbolized his claims to have made Hindustan indeed “the rose garden of the earth,” in the words of the chronicler, and his reign a golden age of prosperity and unending spring.36 The inscription over the Diwan-i-Khas was intended as no idle boast: “If there is a paradise on the face of the earth it is this, it is this, it is this.”37

Koch’s argument is compelling, given her profound knowledge of the art and architecture of the period, and yet it contains a certain paradox. If the Hayat Baksh garden and its attendant buildings embodied a statement of kingship audacious even by Mughal standards, this would nevertheless have remained invisible to most of the world since the garden was the most private of spaces within the palace. For whose eyes was it intended?

Louis XIV’s versailles was almost contemporary with Shah Jahan’s Red Fort and provides a comparable example of “garden imperialism.” With its vast size, its unswerving geometry, its architecturally trimmed shrubs, its army of fountains, Versailles was meant to overwhelm, to broadcast the power of the sovereign. If one needed reminding that he was the Sun King, there were statues of Apollo throughout the garden.38 Two rulers staking their claim to dominion over nature through gardens, the one as Sun, the other as Spring. For most of us, the Mughal garden, with its more human scale, its flowers and fruit trees, its cooling breezes and soft carpets, is the more beckoning.

Unlike Agra, the Delhi riverfront itself was imperial territory, reserved for the emperor alone and a few favorites such as his son Dara Shikoh.39 Others had to build their gardens and houses inland, especially along the Paradise Canal. But build they did during Shah Jahan’s reign and after, dotting both city and suburbs with gardens large and small. The largest by far (almost fifty acres) was the Sahiba Abad Bagh, also known as the Begum Bagh, bordering the Chandni Chowk, designed by Shah Jahan’s favorite daughter, Jahanara, who also oversaw the construction of the most beautiful mansions and gardens within the harem area of the Red Fort. Sahiba Abad was fed by one branch of the canal (the other ran down the middle of Chandni Chowk) on its way to the palace-fortress. Part of the garden consisted of an opulent caravanserai and bath intended for wealthy Persian and Uzbek merchants, but a greater portion was filled with flowers and fruit trees and reserved for women and children of the royal household, a “private, intimate space in the middle of the city—a cool, green area” refreshed by the spray of myriad fountains and waterfalls.40 One can only imagine the delight of an outing to this glorious garden for those usually confined day and night, year after year, to the zenana.41

Outside the city walls, about four miles to the north, one of Shah Jahan’s wives built the Shalimar Bagh, a very large if rather conventionally laid out garden. Here Shah Jahan entertained and here Aurangzeb crowned himself king after locking up his father and doing away with his brothers. Bernier refers to it as the “King’s country house” but judged it inferior to French counterparts such as Fontainebleau or Versailles.42 Nor could it match its namesakes in Lahore and Kashmir for sheer beauty. It did, however, serve as a convenient staging post for royal progresses to the north. Even in the latter half of the seventeenth century, the Mughals had not given up the habit of assembling in gardens, whether for war or peace. When Aurangzeb camped here for six days in 1664 to prepare for his upcoming expedition to Lahore and Kashmir, his retinue of military, officials, and assorted camp followers totaled perhaps a hundred thousand, accompanied by some hundred and fifty thousand animals, if Bernier’s account is reliable.43

Nobles and members of the royal family constructed two types of gardens: the traditional charbagh (a garden divided into quadrants) and the house garden, khanah bagh.44 The latter, modeled on the Hayat Baksh in the imperial palace, was domestic space, serving only the pleasure of the families and servants of the elite. Impressed nonetheless with the magnificence and size of these establishments, Bernier wrote in 1663: “A good house has its courtyards, gardens, trees, basins of water, small jets d’eau in the hall or at the entrance. . . . They consider that a house to be greatly admired ought to be situated in the middle of a large flower-garden.”45 The charbagh, on the other hand, might be open to the public on certain occasions, and, like the royal Shalimar Garden, it often functioned as a country retreat.

The charbagh might also, as we have seen, be the site of a future tomb. A number of these were built by women. Among them was the Roshanara Garden, containing the tomb of the younger sister of Jahanara. Jealous of her sister’s influence with their father, she sided with her brother Aurangzeb in his successful struggle against both father and brothers. Roshanara created the garden twenty years before her death. Jahanara, in contrast, asked only for a simple grave with green grass around it, writing as her epitaph:

Let nought but the green grass cover the grave of Jahanara

For grass is the fittest covering for the tomb of the lowly.46

But Jahanara was the rare exception; most rivaled each other in the magnificence of their garden tombs.

As Mughal power declined in the century and a half following the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, however, tombs fell into decay and gardens into neglect. Approaching the city from the northwest in 1793, William Franklin, a lieutenant in the Bengal infantry, was struck by “the remains of spacious gardens and country-houses of the nobility” now “nothing more than a shapeless heap of ruins.”47 Such descriptions of a landscape in ruins run as a leitmotif through travelers’ accounts of Delhi from the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Delhi and the Raj

In 1803 the British captured Shahjahanabad (which they always referred to as Delhi or some variant thereof) and gained control over the diminished estates of the Great Mogul. Ruling under the auspices of the East India Company, they claimed to bring peace and order after a long period of bloody turmoil that saw Delhi despoiled by a series of foreign invaders. In 1739 the Persian Nadir Shah had sacked the city, carrying off the fabled Peacock Throne and leaving the poet to lament, “The lovely buildings which once made the famished man forget his hunger are in ruins now. In the once-beautiful gardens where the nightingale sang his love songs to the rose the grass grows waist-high around the fallen pillars and ruined arches.”48 In the wake of nadir Shah came Afghans, Mahrattas, and Jats, to say nothing of internecine struggles among the Mughals themselves.

After conquering Delhi, the British left the emperor nominally in power, a puppet ruler pottering about his crumbling palace with a multitudinous retinue of dependent relatives, servants, and hangers-on, or, in the case of the last Mughal, Bahadur Shah (r. 1837–1857), composing verses in the Roshanara Gardens.49 He had little influence outside the walls of the Red Fort; even here, he had to accept British ways and British intrusions, on view like an animal in the zoo. Most British travelers were curious to glimpse the ruler in his fabled palace, but the word that most captured their impressions was “melancholy.” Bishop Heber, for example, “felt a melancholy interest in comparing the present state of this poor family with what it was 200 years ago.” He found the royal pavilions still lovely, with their white marble and inlay of flowers in precious stones. The gardens attached to these buildings, he wrote, “are not large, but, in their way, must have been extremely rich and beautiful,” adding, “They are full of very old orange and other fruit trees, with terraces and parterres on which many rose-bushes were growing, and, even now, a few jonquils in flower. A channel of white marble for water, with little fountain-pipes of the same material, carved like roses, is carried here and there among these parterres, and at the end of the terrace is a beautiful octagonal pavilion, also of marble, lined with the same Mosaic flowers as in the room which I first saw, with a marble fountain in its centre, and a beautiful bath in a recess on one of its sides.” But everywhere the effect of all this loveliness was spoiled by debris, gardeners’ sweeping, walls stained with droppings of bird and bat; “all . . . was dirty, desolate, and forlorn,” flowered inlays and carvings defaced, doors and windows in a “state of dilapidation,” old furniture strewn about, torn hangings dangling in archways.50 Emily Eden, sister of the governor-general, records much the same impression from her audience with Bahadur Shah in 1838: “The old king was sitting in the garden with a chorybadar [mace bearer] waving the flies from him; but the garden is all gone to decay too, and the ‘Light of the World’ had a forlorn and darkened look.”51

Things were even worse by the time the American traveler Bayard Taylor visited in 1853. The garden pavilions were tumbling down, green scum covered the fountain basins, rank weeds infested the walks; old trees were a tangle of parasitic plants, and unpruned rose bushes ran wild. Still, a walk in the garden was a relief after the decay of the imperial halls and the great quadrangle leading into the palace, which he compared to “a great barn-yard, filled with tattered grooms, lean horses, and mangy elephants” and called “a miserable life-in-death, which was far more melancholy than complete ruin.”52

For those British actually living in Delhi in the first half of the nineteenth century, the view was not so grim. They could not, of course, occupy the fort, as they had done in Agra, nor were they initially allowed to own land. Instead they took over Mughal palaces and mansions, especially in the prestigious area around Kashmir Gate, and adapted them to their purposes.53 Sir David Ochterlony, Resident at the time of Heber’s visit, appropriated a portion of a palace that had once belonged to Dara Shikoh, Shah Jahan’s favorite son and heir-apparent, remodeled it and restored the large garden, “laid out in the usual formal Eastern manner, but with some good trees and straight walks.”54 Subsequently a very long extension was added running along the length of the garden. As a result the building was no longer centered on the garden but on a new curved driveway that led past a spread of lawn to a porticoed entry in a tripartite Palladian gateway. As if to underscore the intrusion of English styles, a stately staircase was affixed to the entrance of the building, echoing Government House in Calcutta.55

The Shalimar Gardens outside the city also became a favored retreat for Ochterlony and his fellow officials, as they had been for their Mughal predecessors. After years of neglect, the wilderness of trees and undergrowth was cleared, the old pavilions refurbished, and the pools restocked. The results did not impress Emma Roberts, who sought in vain to recognize the “paradise of flowers and foliage” of Shah Jahan.56 Nevertheless, Ochterlony loved the garden and often took refuge in it. Here, too, another Resident, Sir Charles Metcalfe, built a simple house where he could live secretly with his Indian wife and half-caste family.57 Ochterlony, in contrast, had no such inhibitions, openly flaunting his Indian family. One of the fabled sights of Delhi was the evening outing with his thirteen wives, each on her own elephant, around the walls of the Red Fort. A short distance south of Shalimar Bagh, he bought a large property that he named Mubarak Bagh after one of these bibis. Here he built his tomb, a “wonderful hybrid monument” with a cross surmounting a dome and a forest of minarets clustered on the side wings.58

In due time Charles Metcalfe’s younger brother, Thomas, also Resident in Delhi, built “the last of the princely riverine palaces,” a mansion that rivaled those of the Mughal amirs.59 A huge rectangular building, Metcalfe House overlooked the river and the eighteenth-century Qudsia Bagh that lay between the house and the city walls. Perhaps the best description is provided by the novelist Flora Annie Steel, who knew India well. The parklike grounds around the house were laid out in the manner of an English garden, but with broad verandahs full of rare plants. At their height in the late winter months, the gardens bloomed in all their glory: “There was not a leaf out of place, a blade of grass untrimmed. Long lines of English annuals in pots bordered the broad walks evenly, the scentless gardenia festooned the rows of cypress in disciplined freedom, the roses had not a fallen petal, though the palms swept their long fringes above them boldly, and strange perfumed creepers leaped to the branches of the forest trees.” On a raised dais near the house, a regimental band played. Very English, to be sure, but the scene was leavened with oriental touches: a splendid marquee of Kashmir shawls and Persian carpets, luxurious divans for reclining, a polyglot assemblage of Delhi’s elite, both Indian and European.60

Metcalfe also converted a tomb adjacent to the Qutb Minar into a country house; the space allotted for coffins made a nice dining room, and off of it he grouped an octagonal set of rooms (see Pl. 22).61 “Round the house he laid out a very pleasant garden, and built three or four rooms for the accommodation of gentlemen in the garden,” wrote his daughter Emily. “Our house was called the Dil-Koosha (the delight of the heart) and was constantly lent by my Father to bridal parties for their honeymoons. It was a most enjoyable spot in itself, and had also the additional charm of being close to the beautiful Kutub Minar, the great historical tower, and all the wonderful ruins surrounding it. The grounds on which the tower and ruins stood had been laid out, at my Father’s suggestion, as a beautiful garden, and the place was kept scrupulously clean and in excellent repair.” After Metcalfe’s death in 1853, this, too, fell into ruin and became known as “Metcalfe’s Folly.”62

Because they settled into a preexisting walled city, the British in the first half of the nineteenth century could not very well segregate themselves as in the presidency towns of Madras and Calcutta; there was no separate “Black Town.” Company officials rented and refurbished houses, living and working with Indians in a confined area. Their country residences outside the city gates depended on grants of land bestowed by the Mughals. The older generation, personified by such men as Ochterlony, James Skinner, and William Linnaeus Gardner, openly embraced an oriental manner of life and married Indian women. This became less and less common and more and more frowned upon (witness Charles Metcalfe’s secret life). At the same time, housing became increasingly segregated as the British presence grew and attitudes changed. The so-called Civil Lines gradually expanded in a triangle bounded by the river, the Ridge, and the northern wall of the city. Here Europeans lived in “detached houses, each surrounded by walls enclosing large gardens, lawns, out-offices,” a pattern already anticipating that of New Delhi.63

Nevertheless, there was still considerable interaction between the British, Muslim, and Hindu populations in the daily life of Delhi in the period before 1857. The court was the cultural center, diminished though it might be; Hindus dominated the commercial sphere; and the British ran the administration. Briton and Mughal shared a common love of hunting. Mughal princes, Hindu bankers, and British officials with wives in tow attended official garden parties at Metcalfe House. On the Indian side, Begum Samru “was wont to give superb entertainments and receive the highest mark of respect from her European visitors” in her mansion at the upper end of the Chandni Chowk, “in the centre of a spacious and stately garden.” The Begum was the immensely rich and powerful widow of a German adventurer and commanded her own private army. When she converted to Catholicism, she built a church on the model of St. Peter’s in the small principality that she contrived to keep out of British hands after the conquest of 1803.64 As for religious ecumenism, the Muslim court celebrated the Hindu holidays of Dewali and Holi, while “Hindus were almost as proprietary of Mohurram ceremonies as Muslims.”65 And, important for future generations, Europeans and Indians joined together in 1847 to form the Delhi Archaeological Society, ancestor to the ASI. Its first publication was an account of Delhi’s historic monuments, written by a Muslim scholar and dedicated to Thomas Metcalfe.66

The Uprising of 1857

The British made little attempt to change the face of the city during the early decades of their dominion.67 On the administrative level, however, the conviction grew that the “dual mandate” of emperor and Company could not be maintained indefinitely, but attempts to negotiate an end to Mughal rule with Bahadur Shah went nowhere. Known by his poet’s name of Zafar, he had little interest in anything besides poetry and gardens (he oversaw the layout of two). Besides, a court astrologer had predicted long before that he would be the last of his family to occupy the throne, so what was the point of negotiating?68

The future of Delhi and of the dynasty was abruptly and brutally altered by the events of 1857.69 The spark of mutiny touched off in Barrackpore and Meerut eventually spread to Delhi and much of the Gangetic plain. The eighty-two-year-old Bahadur Shah was forced to accept nominal leadership of the rebellion. Mutineers held the Red Fort over the summer before the British succeeded in relieving the siege of the city and restoring their rule. Both sides committed horrendous atrocities during the conflict, but these paled in comparison with the savage reprisals after victory. British troops were given license to loot the city and did so with abandon; mass executions were the order of the day. Theophilus Metcalfe was so enraged by the despoiling of his father’s house that he set about killing Indians indiscriminately. When the governor-general (now styled viceroy) at last imposed some restraint on the retribution, he was reviled in the press as “Clemency” Canning.

The most extreme voices called for the total destruction of Delhi itself—or failing that, the razing of the Red Fort. In the end, Muslim Delhi suffered severely: “Delhi was made to forget that it was a Mughal city.”70 The great mosque, the Jama Masjid, barely escaped demolition, only to be turned into soldiers’ quarters as a deliberate act of desecration. Barracks also took over large areas of the rest of the city: “Where is Delhi?” lamented the poet Ghalib, “By God, it is not a city now. It is a camp. It is a cantonment.”71 The fort was not demolished, but many of its buildings, already damaged by British shelling, were reduced to rubble and barracks built within its precincts with no regard to existing architecture or gardens. The zenana, which had encompassed the southeast quadrant of the fort, was almost entirely torn down and replaced by military quarters; one of the few pavilions left standing, the terraced Mumtaz Mahal overlooking the river, was used as a prison and later as a sergeants’ mess. The military also took over much of the Hayat Baksh, Shah Jahan’s “life-giving garden.”72

Twenty years later the botanical artist Marianne North lamented, “Alas, alas! The hideous barrack buildings and other atrocities introduced by my countrymen.”73 With the benefit of almost a half-century of hindsight, the ASI, too, acknowledged the “severe treatment” meted out to the buildings of Shahjahanabad and the conversion of the fort into a cantonment. “On the west,” a report lamented, “all traces of the Mahtab Bagh [Moonlight Garden] have long since been entirely swept away and hideous barracks erected in its stead.”74 In less restrained language, William Dalrymple refers to them as “the most crushingly ugly buildings ever thrown up by the British Empire—a set of barracks that look as if they have been modeled on Wormwood Scrubs.”75 Nor did the surviving parts of the palace go unscathed: Emily Metcalfe’s diary refers to soldiers using the ends of their bayonets to pry out leaves and petals of the flowers inlaid in precious stones in the marble walls of the most important imperial buildings. They also removed plates of gold from the domes of the beautiful Pearl Mosque, the Moti Masjid, and sold them; fountains were stripped of their silver finials.76

Even before 1857 the British had encroached on garden areas within the city, especially the public gardens along the river front and Daryanganj. After the uprising, the royal gardens and retreats that had once lined the river and extended onto the Ridge were confiscated. Those immediately outside the fortress walls were swept away completely, along with adjoining mosques, shops, and mansions, and turned into a defensive area 450 yards wide, virtually an island isolated from the city.77 Inexplicably, the tree-lined canal running down the center of Chandni Chowk was covered over by a footpath. The Shalimar Garden was sold off for commercial cultivation, its original footprint now barely visible. The vast gardens laid out on the north side of the Chandni Chowk by Begum Jahanara were renamed Queen’s Gardens, in honor of Queen Victoria, but more commonly viewed as the “Hyde Park” of Delhi. The serai’s walls and pavilions, built for visiting merchants, were leveled and replaced by a town hall and library, across from which rises an incongruously Gothic clock tower.78 The Qudsia Gardens, enclosed within a monumental three-story wall, had the misfortune of housing a British gun battery during the siege. It was badly damaged and much of the garden was later taken over for a bus terminal and tourist campsite. Just outside its southwest corner, the Nicholson Garden commemorates the grave of General Nicholson, killed during the rebellion.79 As Constance Villiers-Stuart remarked apropos of the tomb of Safdar Jung, few Mughal gardens have survived British rule and those that have are invariably associated with tombs: “Respect for a tomb seems to have been the only protection for its garden.”80

The reconstruction and modernization of Delhi after the rebellion brought far-reaching changes to the city, inevitably affecting its spatial layout generally and its gardens specifically. A railroad line ran across Salimgarh and the adjacent corner of the Red Fort, leading to a station that destroyed large sections of the city north of Chandni Chowk. By the early twentieth century, seven lines radiated out from Delhi, making it the most important transportation and commercial center in northern India.81 Roads, too, changed the face of the city. “It is the new roads more than anything else,” lamented Villiers-Stuart, “which have ruined the gardens like the old pleasance of the Princess Roshanara, or the Queen’s Gardens in Delhi City; the winding drives which give a sense of restlessness and exposure as they cut up the garden with their broad bare gravel sweep and make the flower borders, however large, look mean and unrelated to each other.”82 Only a few Mughal gardens, such as the Talkatora Bagh on the lower slopes of the Ridge, preserved something of their original form thanks to their isolation, but it was almost hidden beneath a tangle of scrub and thorn bushes.83

Modernization and neglect were the twin ills afflicting the gardens and monuments of Delhi; and yet “restoration” was itself a mixed blessing. Serious concern for the conservation and restoration of the country’s heritage as a whole did not begin until the turn of the century with Lord Curzon. In Delhi attention focused primarily on Humayun’s tomb and the Red Fort. The walls surrounding Humayun’s tomb had collapsed and much of the garden was planted in tobacco. Curzon ordered the reconstruction of the walls and the clearing and replanting of the gardens, which in turn required the repair of the system of channels and tanks that watered the garden.84

The Red Fort posed more serious problems. Its appropriation by the military had led not only to the rampant demolitions and erections of barracks, but also to the intrusion of roads that served the military but destroyed the carefully designed spatial relationships of Shah Jahan’s palace. In considering restoration, the ASI faced a multitude of questions. Should its goal simply be conservation of old buildings still in good enough shape to be worth saving? Should it aim more ambitiously to rebuild what had been there before, and, if so, how could anyone be sure what this was? How should gardens and other open spaces be treated? Here, too, there was a lack of detailed information about original plantings and hydraulic systems. Those who had carried out the “fearful piece of Vandalism” after 1857, declared the British architectural historian James Fergusson, had not even thought it “worth while to make a plan of what they were destroying or preserving any record of the most splendid palace in the world.” True, some of the finest buildings had survived the onslaught, but situated in the midst of a “British barrack-yard, they look like precious stones torn from their settings in some exquisite piece of Oriental jeweller’s work and set at random in a bed of commonest plaster.”85 And hovering over all these dilemmas loomed the perennial shortage of funds and the conflicting claims of the military.

Curzon himself, as was his wont, gave specific instructions. He ordered that the garden between the Diwan-i-Am, the Hall of Public Audience, and the Rang Mahal reproduce the lines of the rectangular garden that had once existed there. As for the Diwan-i-Khas, the Hall of Private Audience, whose original plinth had sunk into the ground so that the bushes in front obscured the view of the facade, he directed that the flowerbeds lining the paths be totally eliminated and a new garden laid out along with the adjoining garden areas. Pathways, he directed, should be constructed “on the same level as the lawns and not above them”—an odd proposal since he was familiar with Bernier’s account of pathways raised well above parterres. When the ASI set to work on the Hayat Baksh, it lay under some three feet of earth, roads, and debris. Excavations turned up two marble tanks with inlaid bottoms. Still, those “hideous barracks” remained; rather pathetically, an iron rail was erected to fence off the area being restored from the barracks which continued to occupy almost half of the original garden.86

Once again the ASI adopted a double standard, aiming for the greatest authenticity possible for architectural restoration, all the while adopting a much more casual attitude toward gardens. It was not necessary to reproduce the original plantings exactly, they insisted, since horticulture had made immense strides in later times and tastes had changed as well.87 As a result “pleasing lawns and shrubbery” came to define the destroyed gardens, courtyards, and colonnades. Sometimes they were at least an improvement on the intrusive roadways and buildings of the military, but elsewhere they were stunningly out of place, as in the forecourt of the Diwan-i-Am. “The vastness of the courtyard,” proclaimed the official archaeologist with evident satisfaction, “wherein a throng of courtiers daily assembled before the ‘Great Mughal’ is now suggested by a pleasant stretch of lawn and the gorgeous colonnades decked out in rivalry by the nobles of the realm, by screens of flowering shrubs.”

As Anisha Mukherji explains, this misses the “effortless spatial integration of the original design, wherein open spaces formed the necessary prelude to built structures; and built structures in turn provided a focus to, or defined, the open space in front of them.” The Diwan-i-Am, in fact, would have stood in a paved courtyard, the climax of a carefully orchestrated passage through exterior gateway and intervening passages and buildings.88 Where gardens were appropriate, they consisted of little more than the same English formula of lawn and shrub. Gone were “the fruit trees, parterres, and cypresses,” only to be “replaced everywhere by turf and gravel paths.”89

The Delhi Durbars

The belated attention paid to the Red Fort, misguided though it might sometimes have been, was inspired by more than antiquarian interest. Much had changed since 1857–58. Increasingly the British assumed the mantle of the Mughals, whom they had once disdained as weak and decadent. Now they were happy to seize upon the rituals of empire of their erstwhile enemies, rituals that required noble spaces resonant with past glories. Chief among these were durbars. A Persian word, the durbar had been indigenized by the Mughals along with many other Persian customs (and words). The durbar took many forms, but the one seized upon by Lord Canning as a means of reasserting British authority in the aftermath of the uprising had as its focus the public submission of subjects amid an exchange of gifts and pageantry. In the winter months from 1858 to 1860 Canning and his entourage of twenty thousand toured northern India with a succession of grand levees at which local notables reaffirmed their allegiance to the viceroy as representative of the queen.90

Splendid as they were, these traveling durbars were dwarfed by the imperial Delhi assemblage of 1877. It was the brainchild of the viceroy at the time, Lord Lytton, who had a flair for the theatrical as well as strong Tory leanings. He proposed that Queen Victoria be proclaimed Empress of India, arguing that the title would “place her authority upon the ancient throne of the Moguls, with which the imagination and tradition of [our] Indian subjects associate the splendour of supreme power.”91 Although she dearly loved Indians, the queen decided against coming herself, no doubt still put off by the “heat and the insects.”92

The durbar lasted for two weeks, attended by some 84,000 people, housed in a sea of camps, with Indians carefully segregated from Europeans, and everyone sorted out by their place in the social hierarchy from maharajas to sweepers. The Indian and European camps were a study in contrasts. The former were so arranged that each ruler was responsible for disposing of his allotted space as he chose. To western eyes, they were “cluttered and disorganized,” a jumble of cooking fires, people, and animals. The European camps “were well ordered, with straight streets and neat rows of tents on each side. Grass and flowers were laid out to impart the touch of England which the British carried with them all over India.” All of which demonstrated why the British were the rulers, the Indians the ruled, at least in the view of Sir Dinkar Rao. On the other hand, the Indian camp looked more colorful, livelier, and altogether more inviting to many Europeans.93

The viceroy held court in an enormous tent, sitting on the viceregal throne, behind which a stern portrait of the monarch, dressed all in black (she was still in mourning), oversaw the proceedings. At last, at noon on January 1, 1877, he rode into the great amphitheatre to the strains of Wagner’s “March from Tannhäuser,” mounted the throne in front of the imperial pavilion decked out in red and gold, and announced that henceforth “Empress of India” would be added to Queen Victoria’s Royal Styles and Titles.94 In Lord Salisbury’s view, the durbar had to be “gaudy enough to impress the orientals” while at the same time concealing “the nakedness of the sword on which we rely.”95 Somewhat more oddly, it was replete with medieval imagery because that was what appealed to Lytton and seemed to him, in much romanticized form, well suited to pomp and ceremony. It did not appeal to the artist Val Prinsep, who had been brought along to paint a huge picture of the scene for Victoria. Prinsep was aghast at the whole “circus.” He found the imperial pavilion a real monstrosity; the frieze hanging from the canopy was decked with, inter alia, an Irish Harp, the Lion Rampant of Scotland, the Three Lions of England, and, oh, yes, the Lotus of India. It “outdoes the Crystal Palace in ‘hideosity,’” he wrote. Even the viceroy’s wife had to agree that it was indeed “all in rather bad taste.”96

Bernard Cohn cites the 1877 durbar as a prime example of the “invention of tradition.” It was neither authentically European nor authentically Indian, nor even “Indo-Saracenic,” a style that was rapidly catching on as the appropriate architectural idiom of empire.97 But whatever the eclecticism of its content, the 1877 durbar did put Delhi on the world map.

Twenty-six years later, another durbar celebrated the coronation of Edward VII as Emperor of India. The then viceroy, none other than Lord Curzon, saw it as the climax of his proconsulship. Far more knowledgeable about India and far more sophisticated in his tastes, Curzon dismissed Lytton’s “medieval” frumpery: “So far as these features were concerned, the ceremony might equally have taken place in Hyde Park.”98 His durbar was to be emphatically Indian. The great amphitheater constructed for the occasion was crowned with a “Saracenic dome” and adorned with other ornaments of Mughal inspiration. The whole arena, he declared, was “built and decorated exclusively in the Mogul, or Indo-Saracenic style.”99 In addition, the genius of Indian civilization would be on display in a major exhibition of crafts set up in the Qudsia Gardens: carpets, jewelry, paintings, and gold and silverware.100

But while Curzon’s durbar—and it was very much Curzon’s durbar—put the spotlight on the glory that was India and the grandeur of the Mughals, it was even more a celebration of the British Empire and all it stood for: “the outward sign of an ideal, the heavenly pattern of an Empire to which his life was devoted.” The pageantry, the great ingathering from all over the subcontinent, was meant, as Curzon put it, to be an “overwhelming display of unity and patriotism.”101 The King-Emperor would not be attending; he had “done” India in 1875–76 as Prince of Wales and did not share his mother’s enthusiasm. In his stead he sent a pair of lesser royals, the Duke and Duchess of Connaught, who were unlikely to upstage the viceroy.

As the king’s representative, Curzon set about planning for it with the same meticulous attention to detail he bestowed on all his projects. To begin with, he vetoed “Onward Christian Soldiers,” the hymn chosen for divine services during the durbar, not because most of the soldiers present were non-Christians (it was in fact a general favorite) but because it contained the lines “Crowns and Thrones may perish, Kingdoms rise and wane”—hardly the note he wished to strike.102 Then he turned to the layout of the vast camp. Like his predecessor Lord Lytton, he was acutely aware of the symbolism of the city to be created for the thousands of visitors, a city, indeed, as large as Greater London.103 The 1877 durbar had provided a precedent, its “camp spread over a large tract of country transformed for the time into a pleasure ground, with lawns, flower-gardens, triumphal arches and gay pavilions.”104 The 1903 durbar would match this and much more.

The viceroy’s camp alone boasted some fourteen hundred tents covering ninety-three acres just south of the Ridge that had been carved out of a “howling wilderness of jungle scrub” (Fig. 48). It was bisected by a broad avenue, “bounded on each side by hundred-foot-wide lawns decked with palms, potted ferns, flowerbeds, and by side streets named after British proconsuls or heroes of the Raj.”105 The new building erected for the viceroy and vicereine in a commanding position on the slope of the Ridge faced a lawn and fountain at some distance from the road that led to the central avenue of the camp, and in the center of another expanse of turf towered the forty-foot-high viceregal flagstaff. Spread out close by and also in a sea of grass were suites of tents housing the Duke and Duchess of Connaught and other notables, as well members of the viceroy’s staff.106 Specially constructed ducts brought water from the Najafgarh Canal to maintain the vast acreage of lawns and gardens.107 With three polo grounds also demanding turf, the planners had to commission a local dairy farmer to set up a grass-farm near the camp.108 Nothing was left to chance: once the festivities were underway, coolies flicked the dust off all the flowers with feather dusters.109

Fig. 48. The Durbar Camp, Delhi: Main street of the camp

from the roof of the circuit house. Niele and Klein, December 30, 1902

[The British Library Board, Mss.EUR F111/270(55)]

As before, Indian rulers were provided acreage for their camps and left to dispose of it as they would. With more time for planning than in 1877, the results were more varied, providing a microcosm of the country itself. And this time around the native chiefs were not going to be caught without gardens. Because the state color of Hyderabad was yellow, there were yellow flowers in the garden to match the yellow flags and banners and livery of the Nizam’s men. The four Rajput camps were grouped around a small circular garden where a band played. There were also bands in the “tastefully laid out gardens” attached to the Begum of Bhopal’s camp. Maharaja Scindia combined the old and the new in his camp: “Like the beautiful Jai Belas Palace at Gwalior itself, [it] was enclosed in an elaborate and well laid-out garden. It was difficult to believe that, only a few weeks before, this trim and well-cultivated plot, with its fountains and palm trees, had been nothing more than a field of wheat.” The Maharani had her own enclosed winter garden. The Nawab of Junagadh in the Kathiawar Peninsula, famous for its forest of Gir, the only place in the country where the Indian lion was still to be found, produced a “fine display of garden flowers” that had all been brought from his home. The Maharaja of Jaipur was also eager to show that he was a man of the world, able to combine tradition with a cosmopolitan taste. Although his camp followed the time-honored Rajput defensive plan of concentric circles, it also boasted “the refinement and elegance” of a “carefully-planned Italian garden.”110

All of these gardens were overshadowed, however, by those of the Punjab chiefs. Because their camps were situated close to plentiful supplies of water, they were able to bring their “groves and gardens to a greater perfection than those of any other camp.” The star among them was the young Maharaja of Patiala; “[His camp] was surrounded by a hedge of orange and rose bushes, and over six hundred palm trees . . . planted in the gardens, in which a dozen fountains were continually playing. Two colossal statues of knights in armour, bearing electric lights, guarded the entrance to the camp, which at night was illuminated by a profusion of lamps, arranged to form legends expressive of devotion to the Sovereign, while Urdu and Persian mottoes, written in letters of gold, and breathing the same sentiments, were visible by day.”111 No one was going to dismiss these camps as “jumbled and disorganized”!

The full fortnight of scheduled events ran like clockwork, from the state entry into Delhi with Lord and Lady Curzon and the royal party riding on borrowed elephants, to the Coronation Proclamation in the great amphitheater, to the state ball held in the Red Fort. For many the ball was the highlight of the entire affair—“the greatest entertainment ever given in the Indian Empire.”112 The Diwan-i-Am had been enlarged to three times its original size (Curzon himself tended to the architectural details) and decorated for the night with palm trees and flowers. Here four thousand invited guests, European and Indian, danced the night away. At 10 p.m. the vicereine, Lady Curzon, made her spectacular entrance clad in a gown of peacock feathers with emeralds in the eyes of the peacocks, outshining even the Indian princes “simply smothered in jewels.” Dinner was held in the Diwan-i-Khas, “with its marble pillars inlaid with jade and cornelian and much gold tracery,” one guest wrote, adding “You must try to imagine a fairy palace, for that is what it was like.” And above it all, the inscription in Persian letters: “If there is a paradise on the face of the earth. . . .”113

The viceroy’s enemies, and he had quite a few, referred to the extravaganza as the “Curzonisation” Durbar. They criticized him as too preoccupied with his own importance, sitting rigidly on the viceregal throne (unaware that he suffered from curvature of the spine and had to wear a steel corset padded with leather); Lytton’s critics had condemned him for just the opposite— sitting sprawled on the throne in much too casual a manner (unaware that he suffered from hemorrhoids).114 Nevertheless, Curzon was probably correct when he declared on New Year’s Day 1903, “Nowhere else in the world would such a spectacle be possible as that which we witness here today.” One hundred rulers of separate states, an outpouring of loyalty, whether genuine or politic, on a scale unimaginable before or since.115 “I’m sure the world has seen nothing like it before,” declared the painter Mortimer Menpes, “and I could weep to think that it may never look upon the like again.”116

Fate decreed otherwise. Edward VII, having waited so long for his mother to die, reigned less than a decade. In 1911 it was time for another Coronation Durbar. Curzon had had the better part of two years to plan his durbar; Lord Hardinge had less than a year. But with the example of two Delhi durbars behind him, he had a good idea of what must be done. Needless to say, lawns and gardens would once more loom large in the overall design. As Hardinge notes in his memoirs, one of the most unusual sights to greet him on a planning visit to Delhi was “that of hundreds of native gardeners sitting on their hams in long serried lines sowing blades of grass to make out of waste land polo grounds and lawns, all of which were glorious green lawns by the end of the rains.”117 The two polo grounds, fashioned out of cornfields, were provided with three pavilions and sunken gardens with carefully ordered terraces. The king’s camp, stretching over eighty-five acres, “was beautifully laid out with red roads, green lawns and rose gardens with roses from England”118—a rather superfluous touch, one would think.

If Hardinge could not match the sheer splendor of the 1903 durbar, he did have several trump cards to play. For the first time, a reigning monarch would attend the durbar. George V had in fact insisted that it be held once more in Delhi, resisting the very vocal demands that it was Calcutta’s turn— Calcutta was, after all, the capital of India. Furthermore, the Hayat Baksh was finally ready to host a garden party for durbar guests (Fig. 49). Previous durbars had made use of the main pavilions of the Red Fort only at night, no doubt counting on darkness to mask the sad state of much of the palace and the ubiquitous barracks. Curzon had made a start with the restoration of the Hayat Baksh and the Diwan-i-Khas, as well as the questionable enlargement of the Diwan-i-Am, but with his departure in 1905, funds dropped off and the fort reverted almost to the state described by visitors earlier in the century. Thus, when Hardinge inspected its interior in the spring of 1911, he found it a shambles. This would not do. The viceroy found more money for the ASI and “gave orders that the whole of the interior of the Fort should be cleaned up and laid out as a garden with lawns, shrubs and water, and that the jungle outside the Fort should be cut down, drained and turned into a park.”119

Nine months later, all was ready for the durbar: “The inside of the Fort was a lovely garden with flowering shrubs, fountains, lawns and runnels of fresh water.” Outside the walls was a green park dotted with fine trees that had been concealed by the tangle of overgrowth. The Hayat Baksh, the jewel of Shah Jahan’s palace gardens, had been lowered to its original level, but planting could not begin until hydraulic engineers finally solved the problem of irrigation by sinking electric pumps in the old wells and installing pipes, rebuilding something of the old system of channels and conduits that had served the Mughals so well. Its pathways repaired, its channels restored, its ornamental beds reconstructed, and a somewhat incongruous screen of conifers planted to hide the iron railing and barracks beyond, the Hayat Baksh was finally presentable after centuries of neglect and desecration.120

The garden party was one of the last and most enjoyable functions of the durbar. Hardinge could write with satisfaction and echoes of Babur that the Hayat Baksh “had been transformed from a dusty waste into a lovely garden.” The party reached its climax when George V and Queen Mary donned their crowns and royal robes and took their seats on the battlements “so that the crowds below could cheer them”—a hundred thousand strong, passing by “in huge masses and in perfect order.”121 One could almost imagine the king as the reincarnation of Shah Jahan seated cross-legged in the jharoka, performing the ritual of darshan, the viewing; the queen, however, should by rights have been sequestered behind a lattice screen, seeing but unseen.

Fig. 49. Garden party in the Fort, Delhi. Vernon & Co. December 13, 1911.

Wilberforce-Bell Collection

[The British Library Board, Photo 1/14(26)]

Constance Villiers-Stuart was happy to see the Hayat Baksh, the “Life-Giving” garden, brought back to life, no matter how inauthentically. Alas, she could not easily tune out the ugly intrusions that even a viceroy was powerless to dislodge: “Looking across the garden from the river terrace a range of hideous barracks forms the background, towering over the exquisite little Bhadon and Sawan pavilions, and barrack buildings cover the Moonlight Court. The whole effect of the reception held here during the Imperial Durbar festivities was spoilt till the kindly dusk shut out the iron railings and the ugly red and yellow walls. Then as the fire-fly lamps lit up the trees and the lights of the two pavilions gleamed under the falling spray, the old palace garden seemed once more a fitting place for an Indian king to greet his people.”122

The king and his close advisers had had a particular reason for insisting that the Coronation Durbar be held in Delhi, one that remained a secret until announced by the monarch himself: the city would henceforth be the capital of India. “The ancient capital of the Moguls is to regain its proud position,” proclaimed the Illustrated London News, “its dead glories are to live again.”123 A new city, a garden city, would rise from the plain of ruins.