6

Protecting Natural Areas

ALL RURAL AREAS have unique natural features—a bog, a stand of old trees, a waterfall, a fossil site, a desert canyon, a blue heron rookery, a mountain summit. These are often highly valued by the citizens, who may wish to protect them for present and future generations. A rural environmental plan can help protect natural areas if they are properly identified, rated, designated, and incorporated as elements in the plan.

A natural area classification and evaluation system should satisfy three objectives:1 it should be readily understandable to citizens, community planners, and officials; it should be based on the judgment of natural scientists as well as local citizens; and it should be able to withstand legal challenge. To satisfy the first two requirements, the evaluation system should have two parts: a rating by natural scientists and a rating by the planning commission or citizen committee. To satisfy the third requirement, the system must be based on legal precedent or, where judgment is involved, must be systematic, reasonable, and objective. The classification and evaluation system described in this chapter is designed to meet these requirements.2 There are a number of special areas that should not be rated by this system: white waters for rafting, canoeing, archeological sites, land reserved for environmental management, and wilderness areas. These areas should be classified and rated by experts in each respective field.

THE NATURAL SCIENCE RATING

The first step in developing a natural science rating is to classify suggested areas in accordance with a system adapted from the New England Natural Areas Project.3 The system divides natural areas into five categories as follows:

-

Land Forms

Mountain peaks, notches, saddles, and ridges

Waterfalls and cascades

Gorges, ravines, and crevasses

Deltas

Peninsulas

Islands -

Geologic Phenomena

Cliffs, palisades, bluffs, and rims

Natural rock outcrops

Manmade rock outcrops

Volcanic (geologic evidence)

Glacial features (morraines, kames, eskers, drumlins, and cirques)

Natural sand beach and sand dunes

Fossil evidence

Caves

Unusual rock formations -

Hydrologic Phenomena

Significant and unusual water-land interfaces (scenic stretches of

shore, rivers, or streams)

Natural springs

Marshes, bogs, swamps, and wetlands

Aquifer recharge areas

Water areas supporting unusual or significant aquatic life

Lakes or ponds of unusually low productivity (oligotrophic)

Lakes or ponds of unusually high productivity (eutrophic)

Unusual natural river, lake, or pond physical shape -

Biologic-Flora

Rare, remnant, or unique species of plant

Unique plant communities

Plant communities unusual to a geographic area

Individual specimen of unusual significance

Plant communities of unusual diversity or productivity

Plant communities representative of standard forest plant associations

identified by the American Foresters and American Geographical

Society -

Biologic-fauna (classification is the same for fish, birds, and terrestrial animals)

Habitat area of rare, endangered, and unique species

Habitat area of unusual significance to a fauna community (feeding, breeding, wintering, resting)

Fauna communities unusual to a geographic area

Habitat areas supporting communities of unusual diversity or productivity

The list of natural areas in each rural community, of course, would be different. Archaeological sites are omitted from the classification system to reduce the possibility that they might be plundered.

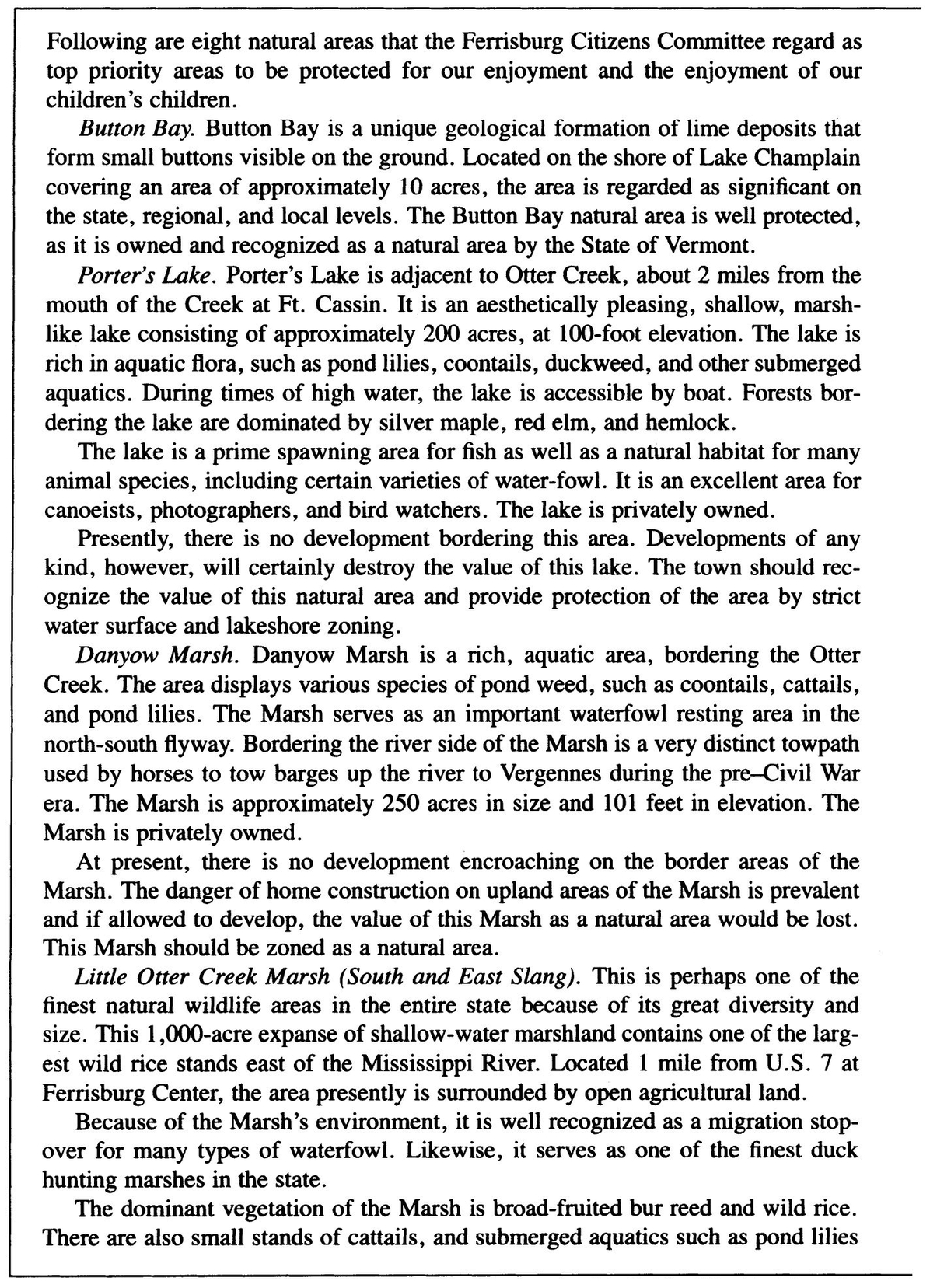

The second step in rating is to evaluate natural areas and determine their potential for preservation in the public interest, a task accomplished by a natural scientist, or the planning committee with scientists’ advice. Each natural area is rated for an array of selected characteristics: size; elevation; frequency of occurrence; diversity or variety within the natural area; national, regional, or local significance; and fragility, that is, the degree to which it is subject to deterioration by human activity or encroachment (fig. 6.1, Natural Science Rating). Each natural area is rated from 1 (low) to 5 (high) for each attribute; the ratings are compared with ratings for other natural areas in the region or state.

SIZE

The larger the area, the more important it is for preservation in the public interest, other things being equal. A five-acre bog with unusual plants would be more desirable to maintain than a one-acre bog. A mountain peak with a thousand acres, all other considerations being equal, should receive a higher priority for protection than a similar mountain peak with only a hundred acres of open space.

ELEVATION

Natural areas occurring at higher elevations are generally more critical from the point of view of environmental quality. For example, an elevation of

FIGURE 6.1. Natural Area Evaluation Rating Sheet

2,500 feet is recognized in Vermont’s Act 250 as being one above which development can take place only under special conditions and with suitable restrictions. Vermont law sets 1,500 feet as the elevation above which “pristine streams” are to be identified and designated by the Water Resources Board. In high desert or mountain states in the West, the cutoff point is higher, but the principle is the same. Research has shown that natural phenomena at higher elevations are more fragile, take longer to recover if disturbed, and are more likely to be rare.

FREQUENCY OF OCCURRENCE

As a criterion for evaluating natural areas, rarity may be explained by reference to a market-driven economic system that attributes higher value to attractive objects of greater scarcity. The concept of scarcity applies to natural areas. Any such areas that are unique are popularly regarded as more valuable than areas of which there may be many. Niagara Falls is highly valued because it is the only major falls in a large geographical area. The Troy colony of great laurels in Vermont is highly valued as a natural area because it is unique in the state. A similar stand of laurels in the Carolinas, where there are many, would be valued much less.

DIVERSITY OR VARIETY

A mountaintop with rare plants would be rated more highly than another mountaintop with no rare plants. A wetland area that is also a migratory wildlife feeding ground would be rated more highly than a similar wetland area not used as a feeding ground.

SIGNIFICANCE

Recognition of a natural area also is important. A mountain peak designated as a national natural landmark, or one identified by a local REP committee, is of greater significance to protect than a peak of similar elevation and configuration that has not been so designated or identified.

FRAGILITY

Fragility of a natural area is a criterion that duplicates or reinforces other factors used in evaluating the area. In general, fragility is correlated with higher elevations. However, there are also fragile low-elevation natural areas, for instance, rare-bird nesting sites in a bog or a rookery on a cliff. If disturbed, these sites may be abandoned.

THE PLANNING RATING

After the natural science rating is completed, other factors, based on the comparative characteristics of each natural area, must be considered. The planning rating (see fig. 6.1, Planning Rating) is based on six categories that represent public use of, or public interest in, natural areas: the number of recreational uses, the number of education and research uses, the potential for or likelihood of development, the quality of management, the planning status of the area, and the function of the area in a natural cycle.

The number of recreational uses reflects the importance of an area to the public in terms of how many would benefit directly from its maintenance. For example, if an area is of interest only to hikers, it has one use and gets one point in the planning rating. If it is of interest to hikers and photographers, it has two uses and thus earns two points. If it is of interest to hikers, photographers, and cross-country skiers, it has three uses and receives three points.

The number of educational and research uses is also counted. If schoolchildren visit the area, that is one educational use. If it is additionally used for geologic research, it would be rated two, and so forth.

The probability of loss of a natural area to development is determined by the citizens committee or the planning commission on the basis of their evaluation of the land market pressures. For planning purposes, the greater the danger of loss or misuse of a natural area, the more urgent the need for action to protect it, therefore the higher rating.

The quality of management of a natural area is another basis for judging how urgent it is to acquire the land. A natural area with private owners who arrange for it to become a public conservation zone (or to receive greenbelt tax status) may have a lower priority for additional public protection than a natural area on land held for speculation. An area under good management is less urgent to acquire than an area being mismanaged.

The planning status of an area can be a useful basis for setting priorities. If an area has been designated in local, regional, or state plans as a natural area, it would be rated more highly than an area not so designated. This category attaches weight to areawide plans; an area designated in a regional or state plan is given a higher rating than those not so designated.

Finally, the degree to which the area functions in natural cycles and/or food chains as well as its aesthetic appeal must be considered in a planning rating. If a marsh filters water before it reaches a lake, this function needs to be considered and added to the rating. An area that functions in the hydrologic cycle as a groundwater recharge area should get a relatively high rating. Similarly, an area that functions as a buffer zone between incompatible land uses might be rated highly.

THE COMBINED RATING

The natural science rating and the planning rating are combined in a composite rating (see fig. 6.1). The two classifications, each with six criteria and a maximum of five points for each, gives a possible total combined score of 60 for a given area. The lowest score would be 12. The higher the composite rating, the higher the priority for protection or acquisition and for ultimate inclusion in a rural environmental plan. This system encompasses both scientific and popular definitions of natural areas. Residents may propose a beaver pond as a natural area, and it will be so designated even though the natural scientists say it is a transitory phenomenon. A geologist may propose a roadcut, which seems pedestrian to the citizenry, as a natural area to demonstrate to students the geologic history of the area.

THE NATURAL AREA CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM

The purposes and limitations of the classification and evaluation system should be understood. It is a rating system for planning purposes, based on scientists’ judgment augmented by planners’ judgment to accommodate the requirements of community planning. The system is designed to utilize the best of scientific knowledge and the best of planning judgment in the interests of developing an acceptable rural plan.

If one area is rated lower than another, that does not mean the first will not be protected. The procedure is designed to help a community decide where to act first. All natural areas listed in an adopted plan may eventually be protected. In some instances, a lower-priority natural area might be acquired before a higher-priority natural area because it becomes available sooner.

In any classification system based on combined factors, questions are raised concerning the weighing of factors. The system as shown here is not excessively sensitive to any single factor of the twelve. Even if the rating of a single factor is doubled or halved, the total index does not change by much. and hence the relative priority of the area will not change significantly.

The major purpose of the natural area classification and evaluation system is to inform people of significant or unique natural phenomena during REP development and implementation. The system is designed so that any interested citizen or community group can follow the instructions, obtain a list of natural areas from state agencies, supplement these with a local survey of additional natural areas, and then conclude their work by developing a description and rating for the community plan.

This system has been tested in a number of regional and community planning projects. Natural scientists from state or federal agencies or students from the state university provided the natural science rating data; and citizens committees or town planning commissions provided planning ratings. In these cases, the process has proven comprehensible, inexpensive, and effective. The chapter on natural areas is usually one of the most interesting and acceptable in a rural environmental plan.

METHODS OF PROTECTING NATURAL AREAS

There are three conventional methods for protecting natural areas: purchasing, zoning, and designation. Outright public purchase is recommended when a natural area is part of a larger purchase area such as a park. Zoning is recommended to protect a natural area in a conservation zone such as a higher elevation, a lakeshore, or a wetland.

Designation consists of identification, objective evaluation, and incorporation of the description, evaluation, and statement of public interest in a master plan or declaration. Designation is recommended as a land-use control when the objectives of the public and of private owners coincide. Through designation, decisions about acquisition or easement purchase to achieve public objectives can be deferred until public and private objectives differ. Designation, by itself, is not a taking of value or a limit on existing rights of ownership. Rather, it serves notice that if a change in use is proposed by the owners, that change must be adjusted to accommodate the public interest.

Designation has often proven successful in protecting natural areas. An owner who discovers that his or her land is prized as a natural area may become interested in, knowledgeable about, and protective of that land. In fact, the owner may initiate steps to protect it. Designation of natural areas, and incorporating designations in a master plan, enables the planning commission to set requirements respecting the integrity of those areas in the event of proposed changes in their use. For example, such areas can be included in the 10 to 15 percent reserve usually required for public purposes.

Unlike purchase in fee simple, designation does not cost the taxpayer money. Unlike zoning, it is not likely to be challenged in the courts, as it does not deprive owners of their rights. On the contrary, the effect of designating a natural area on private land may be to increase the value of the property as well as the value of adjacent properties.

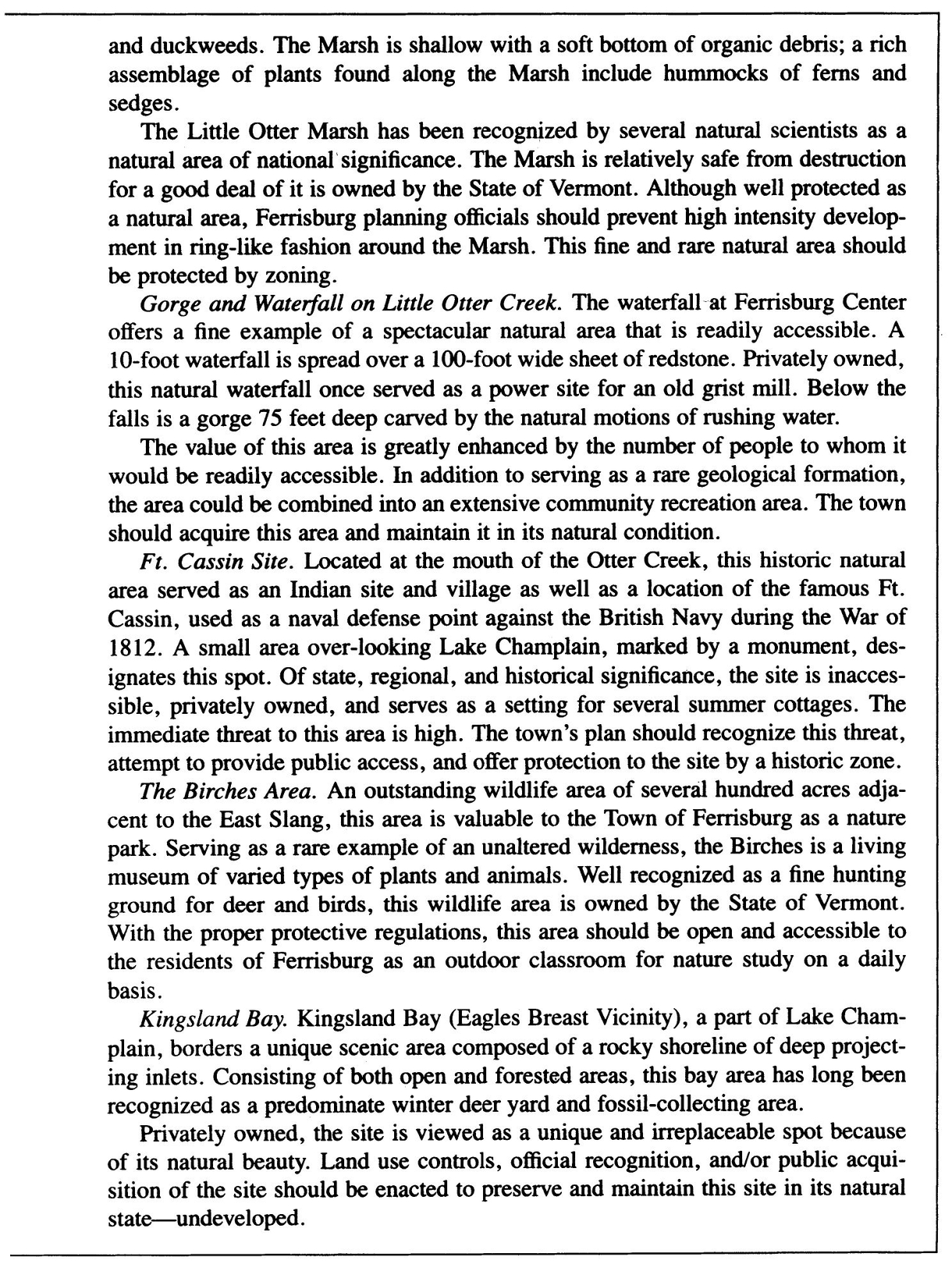

Figure 6.2 is the natural area section from the Ferrisburg, Vermont, rural environmental plan. It illustrates citizen action taken to designate and protect natural areas in the community and surrounding area. The eight locations were inventoried by two graduate students in the course of developing an environmental plan with the town.4

CASE: CAMELS HUMP PARK, VERMONT

Camels Hump is one of the highest, most distinctive, and visible peaks in the Green Mountain range, which runs the length of Vermont and gives the state its license-plate nickname. The summit of Camels Hump is in a state forest. Its slopes were once owned by lumber companies, and it is surrounded at the base by small towns. Unlike other high peaks in Vermont it is untouched by ski slopes, and it has long been a favorite destination for bear hunters, hikers, hawk migration watchers, rugged cross-country skiers, and snowshoers. In late 1966 a rumor circulated that a lumber company planned to sell the east slope to a developer who was going to cover it with Swiss-style chalets accessible by cable car. Concerned citizens were quick to respond. The conservation committee of the Audubon Society called a meeting to save Camels Hump. The meeting was well attended by representatives of hunters, hikers, bird-watchers, and conservationists. They decided that a specific plan for extensive public use of the mountain would bring more support to save the mountain than a negative campaign against the developer alone. They asked an environmental planner from the University of Vermont to work with them, and together they collected data, discussed appropriate land uses and controls, and produced a proposed plan.

The planning report, “Camels Hump Park,” was published by the Extension Service of the University of Vermont in October 1967.5 The plan proposed that different zones of the mountain be distinguished by elevation. The highest zone, a fragile environment, was to be used by hikers and hunters only. The middle zone would allow cross-country skiing. The lower zone would be for multiple use under regulations to protect the environment. The three zoning levels would include state-owned forestland at higher elevations and privately held land at the two lower elevations. This citizen proposal appeared necessary as the State Department of Forests and Parks, which owned the summit, did not recognize the need to change policies that were geared toward timber production and harvesting and ski-slope development.

FIGURE 6.2. Natural Areas Inventory, Ferrisburg, Vermont

The Save Camels Hump (SCH) committee took their plan public with news stories and a series of open meetings. Considerable support was quickly forthcoming from the Vermont Federation of Sportsmen’s Club, the Green Mountain Audubon Society, the Vermont Natural Resources Council, and the Vermont chapter of the Society of American Foresters. There was no organized opposition; however, the State Forest and Parks Department continued to withhold support.

In May 1968 new stimulus to the SCH movement came when U.S. Senator George Aiken persuaded the U.S. Department of the Interior to include Camels Hump in the National Registry of Natural Landmarks. People living in small towns around the base of the mountain formed the Camels Hump Area Preservation Association (CHAPA) and launched a publicity campaign. They held public meetings and distributed a newsletter. The effort was successful—there was wide support and no opposition.

The State Department of Forest and Parks was now ready to support the SCH plan. Because they could control land use on their own acreage but had no authority to zone the lower slopes, special legislation was necessary. The SCH and CHAPA committees approached state Representative Arthur Gibb, chair of the House Committee on Natural Resources, who persuaded the commissioner of forests and parks to appoint a nine-member committee to draft a statute. This committee was broadly representative, including foresters, conservationists, and hunters. A bill to establish a special park was drafted and Representative Gibb introduced it to the state legislature. When the House and Senate held a joint hearing on the proposed bill, all testimony was favorable.

On April 18, 1969—two and a half years after the initial citizens’ meeting—the Vermont legislature passed act 71, chapter 57, establishing the Camels Hump State Park and Forest Reserve. The statute incorporated the objectives of the SCH and CHAPA ad hoc committees. The State Department of Forests and Parks, now a strong advocate of the new park and reserve, changed its priorities and proceeded to purchase additional land on the flanks of the mountain to assure its protection from intensive development.

FIGURE 6.3. Proposed Camel’s Hump Park Showing Elevation-Determined Use Zones

CONCLUSION

Identifying and planning the protection of natural areas can be one of the most enjoyable parts of developing a rural environmental plan. Schoolchildren may discuss natural areas and suggest the ones they would like to have protected. Nearly everyone supports natural area protection, and everyone can participate. Further, nearly every political jurisdiction has several such areas to classify, designate, and protect. The manner in which this is done should be objective, fair, inexpensive, and of immediate benefit to the community. While defining and evaluating natural areas were difficult tasks in the past, they are now relatively easy. A two-part classification system can be used to define natural phenomena in both scientific and popular terms. The system provides a list of priorities for incorporation in a community plan.