11

Equity and Evaluation

PLANNING CAN BE criticized as elitist if it amounts to protecting and conserving a natural environment for a favored few. This charge has been valid in some instances, for example, where exclusive, expensive developments monopolize access to the public waters of a lake. Good planning increases the attractiveness of an area, which in turn increases property values. And increased property values lead to increased rents, placing an unfair burden on low-income residents. To prevent this sort of burden, a number of specific planning policies should be considered. Methods for positive social planning, social-impact analysis (SIA), and plan evaluation help to ensure that a community plan is designed to serve all citizens in an equitable manner.

POSITIVE SOCIAL PLANNING

Positive social planning is a collective reference to planning tactics that promote the welfare of all citizens, especially those of low to moderate incomes. Social planning elements that might be incorporated in a community plan include affordable housing, neighborhood integrity protection, public access to public waters, community parks and playgrounds, a public transportation system, and a bike and pedestrian trail system.

A requirement for affordable housing in a subdivision ordinance helps to offset the effect of much traditional planning, which has protected the property values of middle- and upper-income groups. The economic segregation caused by relegating all site-delivered, manufactured, or modular housing to MH zones or to trailer parks is inconsistent with the options for affordable housing now available. Less expensive but attractive and durable manufactured housing can be placed on foundations and then site-finished to be both affordable and compatible with custom-built homes.

To distribute the benefits of community planning more evenly, developers of more than four units of housing can be required to reserve a certain percentage of total area of land to be developed (say, 10 percent) for the construction of low-cost housing. Such areas, dispersed throughout the community, would be allowed development in greater (specified) density. The definition of low cost or affordable housing could be based on recent market criteria, such as “designed to sell for no more than 10 percent above the cost of the lowest-cost new houses sold in that jurisdiction during the past twelve months.”

The provision for low-cost housing in a community plan can result in several benefits: implementation of this objective helps to provide affordable housing at no direct cost to the taxpayer; low-cost housing would not be concentrated in a single area, or future ghetto, but rather would be distributed throughout the community; and provision of affordable housing would allow a more equitable management of growth based on non-exclusionary, rational scheduling of capital improvements.

Neighborhood integrity protection is another method of providing equity for citizens within a planning jurisdiction. Sometimes regional development or highway construction threatens to disrupt or destroy well-established, viable neighborhoods. A new highway may be planned through a less affluent neighborhood or a small town, taking houses or cutting the community in two. Or a speculator may seek zoning variances to shift land use from residential to a more intensive use in order to increase income by increasing the value of benefited land. These procedures, practiced in many urbanizing regions, have frequently destroyed the integrity of residential neighborhoods.

In 1968 highway planners proposed that an access route for Burlington, Vermont’s urban center be run through an established neighborhood of modest homes. The taking for right of way would have eliminated all the houses on one side of the street. A state representative who happened to live in the neighborhood led the opposition to the proposal. The neighborhood prevailed and the highway was relocated. This drama led a study team from the University of Vermont to a more careful review of the social unit of neighborhoods in the planning process. The team found that high-income neighborhoods were seldom the target of highway planners or efforts to rezone; it was the low-income neighborhoods that were especially susceptible. Threatened neighborhoods are well advised to organize neighborhood improvement or protection associations and get neighborhood integrity protection goals written into municipal or county plans. When such goals are stated in an adopted plan, it establishes legal standing and makes it much easier for a neighborhood association to protect its interests.

A few decades ago access to public waters, and to surrounding hills, woods, and pastures, was essentially free. This situation changed gradually as the population grew until many publicly owned resources were shut off from public access by the arrangement of private holdings. Public access is sometimes cut off as a result of the gradual change from rural to suburban land ownership. The process of redressing this imbalance and providing adequate access to public waters requires long-term planning. In rural communities the following steps can be taken: conduct an inventory of public access, develop public goals for access to public lands and waters with a survey, and develop a long-range plan to achieve public access in accordance with those goals and with the financial resources of the community.

Community parks and playgrounds are often omitted from plans for small towns and rural areas, being looked on as luxuries that come later in the development process. This policy should be reversed and high priority given to recreational and open-space areas serving everyone in a rural community. Once these areas are designated in the plan, land acquisition can be scheduled over time and community volunteers can see to development, utilizing small-scale and low-cost technologies from design and implementation to upkeep and maintenance.1

Public transportation systems are of great service to the elderly, the very young, and people with limited incomes. A low-cost, demand-responsive van or jitney system, one that fits the needs of underserved groups and other potential users, should be considered for the community. Federal subsidies and, in some areas, state funds and technical support are available for planning and implementing rural transit and paratransit systems.

Positive social planning also includes the designation of a bike and pedestrian trail system. Rural plans frequently ignore bicyclists and pedestrians. Rural communities can benefit from a system of combined pedestrian and bike paths that connect residents with schools, stores, post offices, parks, offices, work places, and public waterways. To establish a trail system interested residents must find or create a group with a keen interest in developing a trail system, study what other communities have done and what is possible locally, and participate in planning, getting the best proposal into the goal survey and ultimately into the adopted plan.

SOCIAL IMPACT ANALYSIS

SIA is a procedure that parallels benefit/cost analysis and environmental impact analysis. SIA, though, often yields negative rather than positive impacts. In conventional benefit/cost analysis economic impacts are often arranged to show benefits exceeding costs. Benefits tend to go to individuals or groups that are politically active in the promotion and implementation of a proposed project. Social impacts, by contrast, tend to be negative, that is, they describe adverse effects on people who are low-income or who have little political influence.

An SIA is a method of assessing the social effects of an existing plan or of evaluating the potential effects of a development proposal.2 It may be conducted in four steps:

- Identify types of impacts.

- Specify the nature and severity of impacts and the number of people affected in each category.

- Hold a review and discussion of perceived impacts.

- Relate social impacts to the engineering, economic, and environmental impacts to provide the public and elected boards with a broader picture.

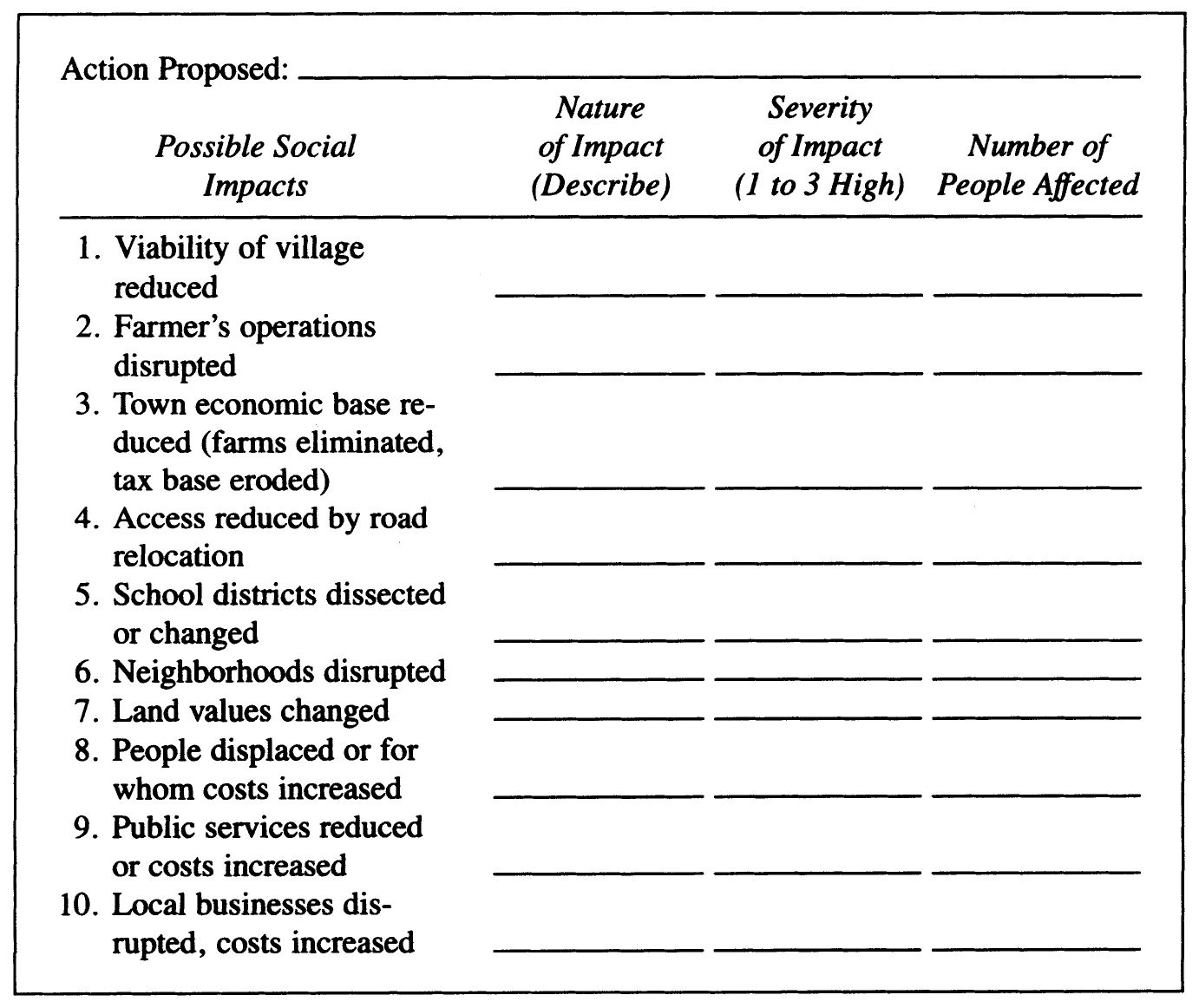

The first step is to draw up a list of the types of impacts (see fig. 11.1). This must be done simultaneously with the economic analysis, as the two analyses together comprise the broad spectrum of perceived impacts on all affected groups and interests. For example, in a proposed project to reduce flood damage by building a dam and detention reservoir, a downtown store owner would benefit if the store were thereby protected from flood damage. A rural village upstream from the dam, though, would be disadvantaged, both economically and socially, if the proposed reservoir required relocation of a road and increased the time and cost of travel to schools and to town.

The list of those affected, favorably or adversely, by a proposed project includes neighborhoods, villages, towns, school districts, and organized interest groups. Direct observation and interviews with people in an affected area will reveal what entities belong on the list. Many affected groups are represented by people who testify at advertised public hearings on proposed projects. Their testimony identifies the interest group and the nature and severity of the impact it expects to receive. Others adversely affected can be identified by comparing a proposed project with public land-use goals in adopted community or regional plans.

Many projects directly affect property values. An increase in land value is a windfall to the owner, especially if local tax assessment practices do not recognize the increased value. The same increase in property value may adversely affect renters who have to pay higher rent or move out. The significance of an increase or reduction in property value depends on the proportion of a person’s total wealth represented by land ownership or the portion of income spent for rent. For low-income rural people, this may be a considerable amount.

The second step is to add to the list of possible social impacts a description of their nature, their severity, and the number of groups and people involved. Severity may be rated on a scale from 1 to 3, representing low to high impacts as shown in figure 11.1. A low-severity impact is a temporary or very limited inconvenience or one that easily can be repaired, compensated for, or adjusted. A medium-severe impact is one that seriously disrupts a group’s activities or the pursuit of a group’s goals. A severe impact is one that destroys a group’s integrity, for instance by moving the group to another location or permanently disrupting its major functions. The purpose of this rating system is to permit public scrutiny and open discussion of various impacts.

FIGURE 11.1. Social Impact Analysis

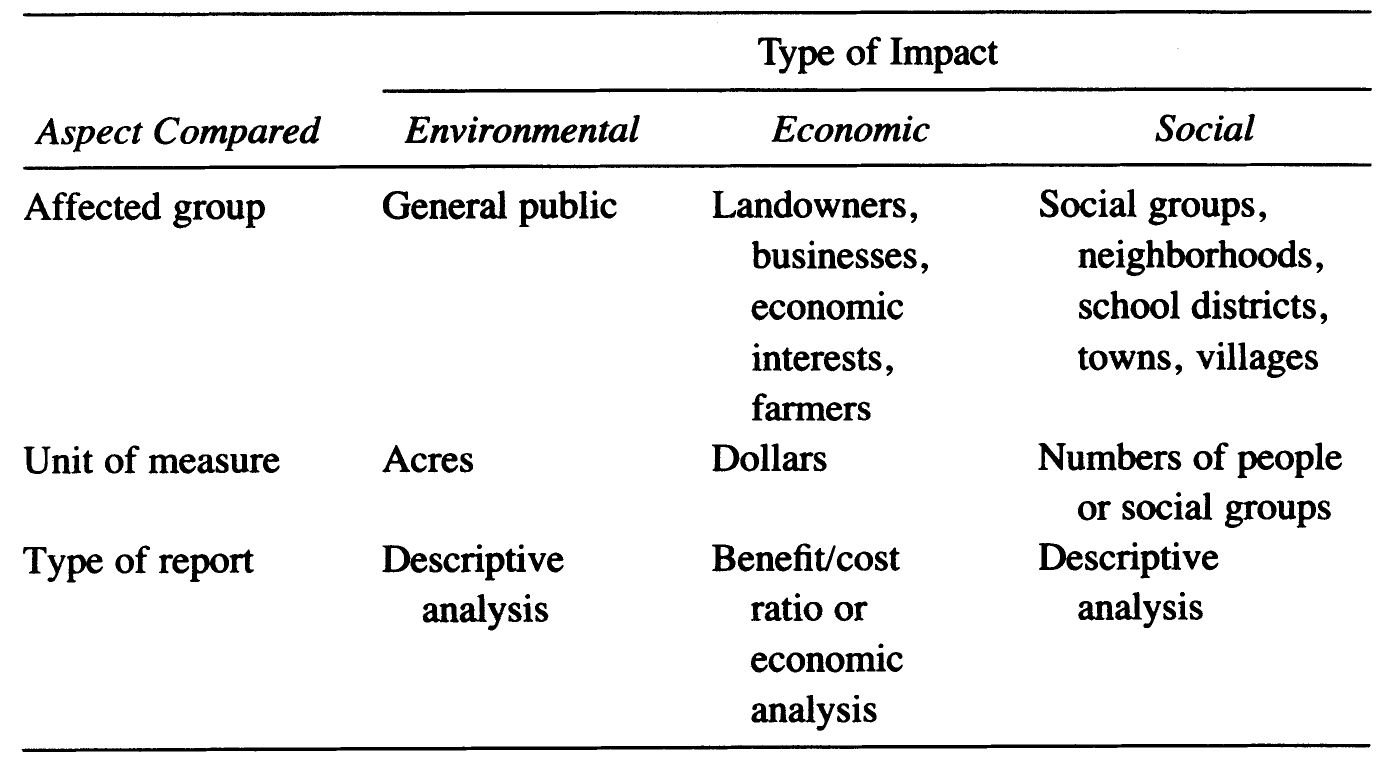

The difference between economic and social impacts is this: economic impacts are visited on businesses, corporations, and land and capital owners and are measured in dollar value gains or losses of income or of property value; social impacts are economic effects on social groups such as families, neighborhoods, school districts, and small government units (see table 11.1). They are measured in numbers of people or numbers of groups affected and by the degree of severity of impact.

The third step is technical critique and public review. The identification and weighing of social impacts, which require judgment, may be biased by the researcher’s values. To reduce this possibility, the report is subjected to professional criticism and to public review. Professionals include an qualified experts who do not have vested interests in the project under study. If the professional review raises questions, it will lead to further discussion of criteria or method or both, and the analysis will be refined. The findings of the analysis are also presented to the public through hearings, news releases, and editorials. The purpose is to inform and to receive comments from people affected by the project.

Comparison of Environmental, Economic, and Social Impacts

The fourth step is combining and weighing impacts. After the report and the technical and public reviews are completed, any adverse social impacts must be weighed against environmental impacts, economic impacts, and construction costs to determine if the project is in the public interest.

Combining and weighing impacts across this spectrum poses a special problem, because social impacts may be qualitative and not directly comparable to economic impacts. Fortunately there is a precedent for addressing this problem. Environmental impacts are frequently non-monetary and non-quantifiable in specific terms, but if all impacts are clearly identified and described they can be reviewed, evaluated, and incorporated into the political decision-making process. The decision process culminates in a vote on the proposed project by the appropriate government entity, that is, the town council or county commissioners. If this process is open, rigorous, and is free of dominance by lobbies or special interest groups, the decision that emerges will be in the public interest. Each person voting will compare social impact data with engineering costs and with environmental and economic impact analyses. While the decision will not please all participants, it will probably be acceptable to the public.

EVALUATING PLANS AND PLAN IMPLEMENTATION

Some rural areas or small towns already have a planning document, usually called a master plan or comprehensive plan. Many such plans were funded under the Housing and Home Finance Administration’s planning program, originally authorized by the federal government under the Housing Act of 1954. The existence of “comprehensive” plans leads some citizens to think that local planning is complete. Unfortunately, this is not always true. Many community plans lie forgotten on the shelves of the village office or the county library, perhaps because they were developed without citizen participation. Evaluation of an existing plan determines whether or not it is being used regularly to guide public and private decisions.

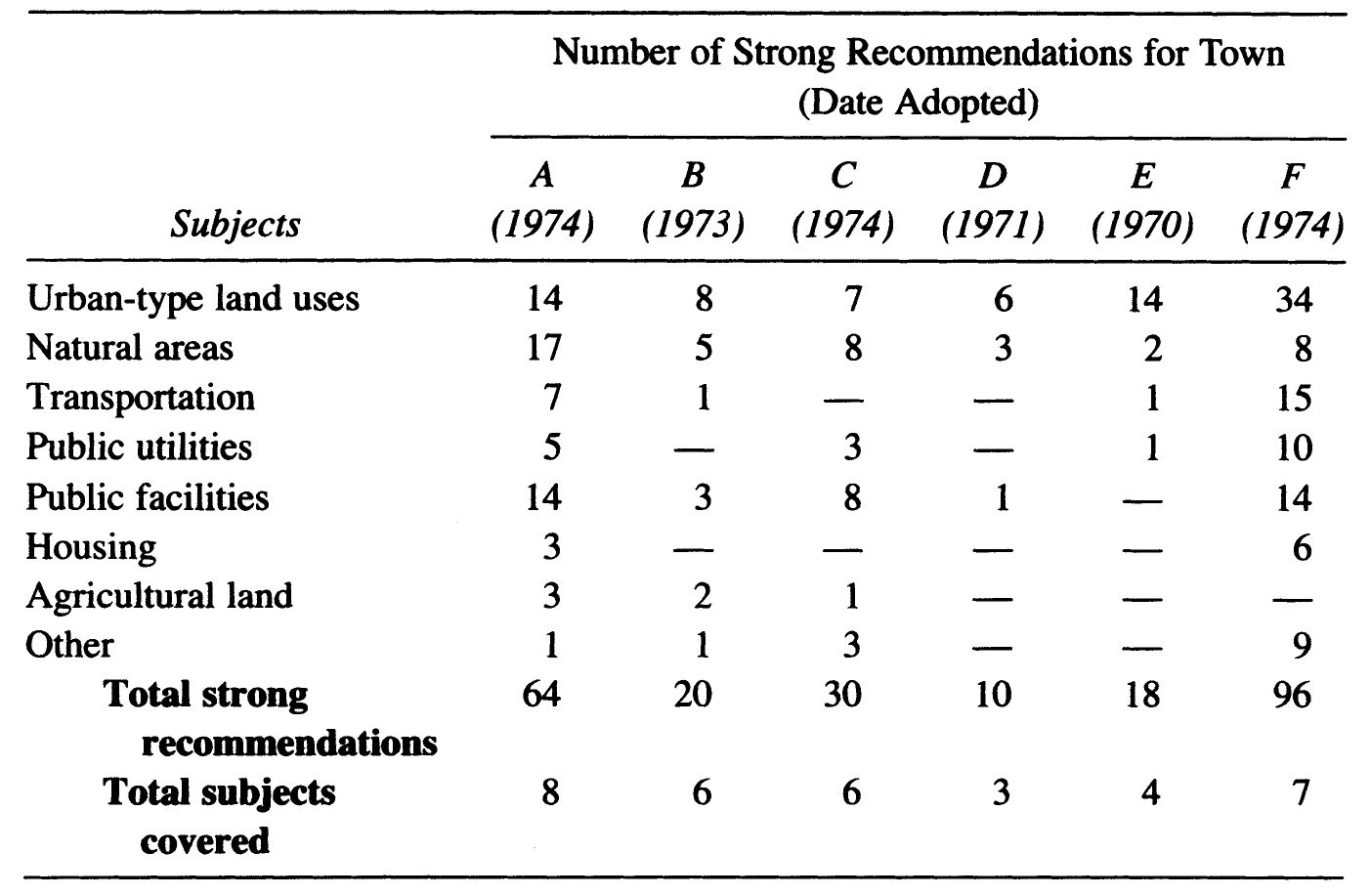

Plans may not be recognized as bland or useless without standards by which to judge their effectiveness. Early in the development of REP, a University of Vermont research program assessed the planning process in rural communities by use of a rating system that evaluated six aspects of a number of adopted plans.3 The rating system counts the number of recommendations in a plan, the number of bylaws adopted, the number of recommendations implemented, the number of variances granted, environmental content, and comprehensiveness, including social and economic components (see table 11.2).

The evaluation system for adopted plans can be used by state and regional planners, planning administrators, and students. The six aspects are evaluated, then the plan and the planning process are compared with several adopted plans in neighboring jurisdictions. Comparison should be emphasized here. There is no model or ideal plan to follow. The best plan is the one that rates highest by comparison with the plans of other jurisdictions in any county or region.

Rating an Adopted Rural Community Plan

| Step | Action |

|---|---|

| 1 | List all strong recommendations, i.e., those that include the words recommend, propose, should, shall, will, must, and necessary. Weak recommendations are those that include the words may, could, might, should, encourage, suggest, hope, consider, and feasible. Weak recommendations are not counted. |

| 2 | Count bylaw (or ordinance) adoption. Count 1 for each: zoning ordinance, subdivision regulation, official map, capital budget, and program. Adoption and use of all four is rated very good, one or less is very poor. |

| 3 | Count plan implementation actions. List specific recommendations implemented, in progress, and partially or not implemented at all. Evaluate recommendations implemented and the percentage implemented per year. |

| 4 | Count zoning variances. The number of variance requests compared with the number granted indicates how well zoning fits the needs of the community and how well the law enabling zoning is being followed. |

| 5 | Evaluate environmental content by counting recommendations for environmental actions and compare with plans in other rural jurisdictions. |

| 6 | Check the comprehensiveness of the plan by counting strong recommendations in each of six categories: (a) specific land use, (b) environmental protection and public access, (c) transportation, public utilities, and public facilities, (d) housing, (e) social and cultural resources, and (f) economic development. |

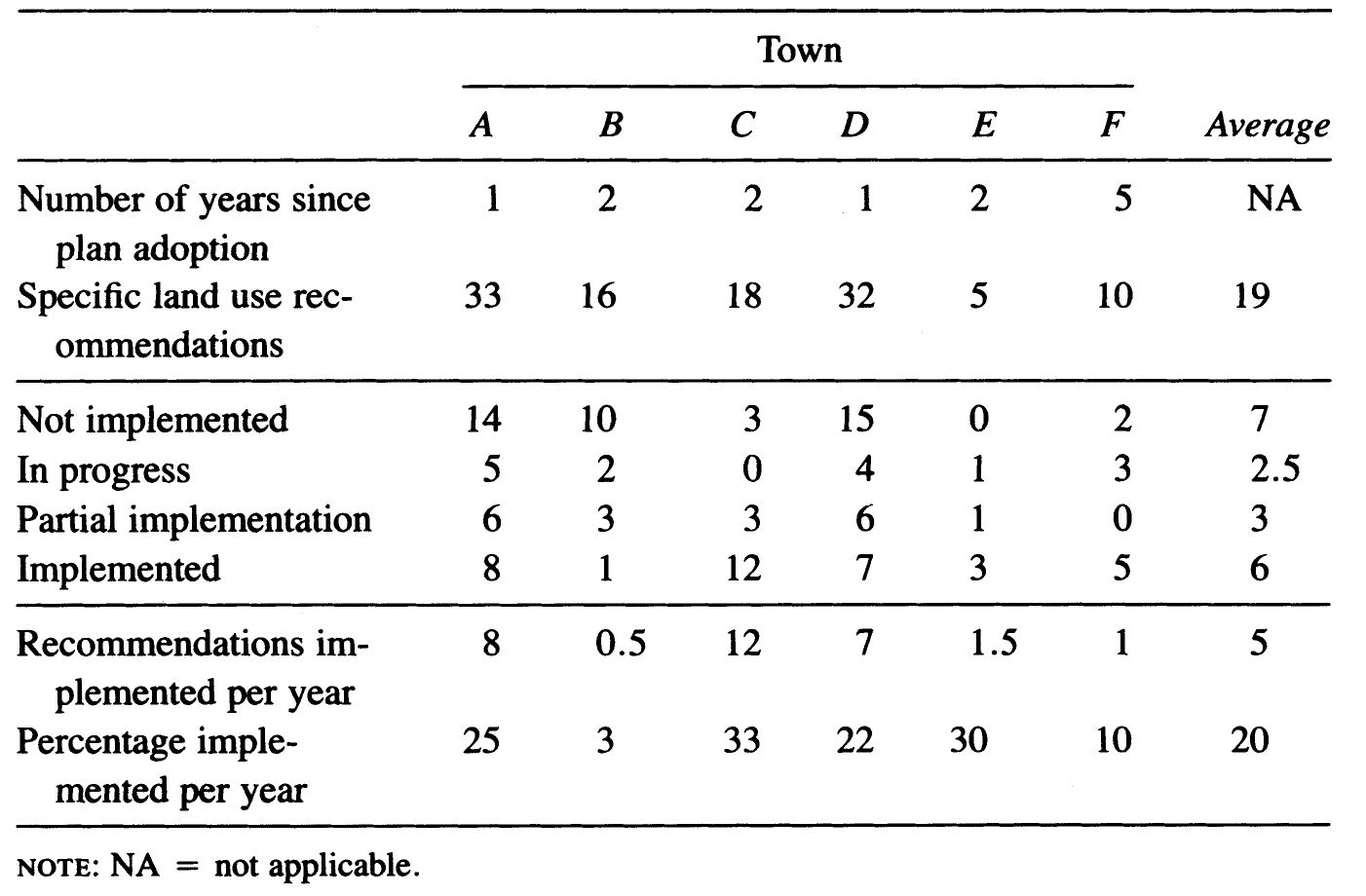

STEP 1: COUNT PLAN RECOMMENDATIONS

The essence of a rural environmental plan is the list of strong recommendations. Recommendations must be specific and capable of implementation if they are to achieve public goals. Without them, an inventory of present land use and a statement of goals do not make a plan. Hence the nature of recommendations—their number, specificity, and comprehensiveness—are one indicator of the quality of rural plans. The first step in rating a plan is counting the number of strong recommendations. This was done for six Vermont communities as illustrated in table 11.3.

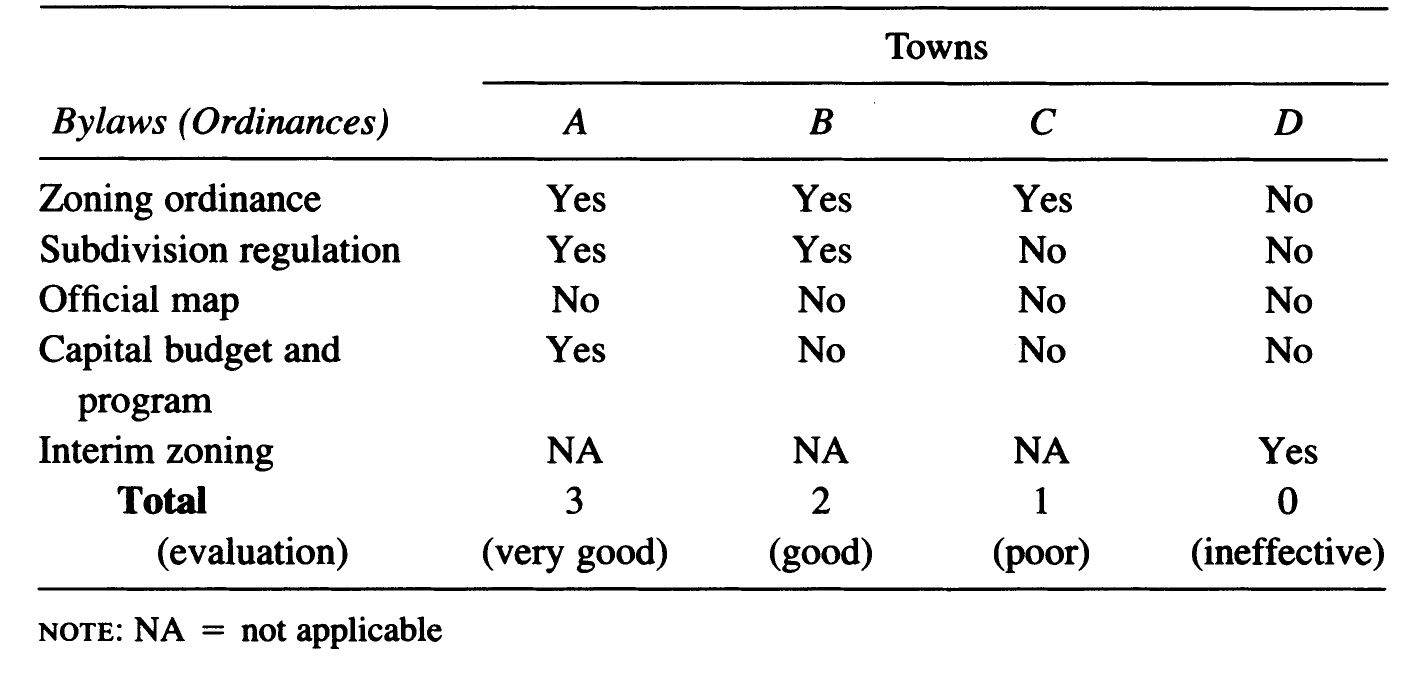

STEP 2: COUNT BYLAWS ADOPTED

State enabling legislation for planning usually allows rural jurisdictions to adopt four bylaws or ordinances for the implementation of adopted plans: a zoning ordinance, subdivision regulations, an official map, and a capital budget and program. Table 11.4 clearly distinguishes town A, which has adopted three required bylaws, from B, C, and D, which have adopted fewer bylaws. Town A is well on the road to planning. Towns C and D have hardly started.

Plan Ratings for Six Chittenden County, Vermont, Municipalities

STEP 3: COUNT PLAN IMPLEMENTATION ACTIONS

Plan implementation is also rated by counting the specific recommendations acted on each year. This measure quickly separates rural communities that show no intention of implementing their adopted plans from places seriously following their adopted plans. The method of evaluating land-use recommendations is to list proposals for change in the existing use of land resources. Specific proposals for future land use are implemented in one of two ways: funds are committed or equally definitive action is taken by town or county officials, or zoning regulations are adopted to make the proposed land use mandatory. This information is collected by interviews with public officials involved in the planning process. On the basis of these interviews each recommendation is classed in one of the following categories: not implemented—no action taken; implementation in progress—discussion stage only; partial implementation—some limited action; and recommendation implemented—funds committed, ordinance passed, or other definite action taken.

The number and percentage of recommendations implemented or partially implemented per year in six Vermont communities are shown in table 11.5. We can see that towns A and C have high rates of implementation, while towns B and F have very low rates.

Adoption of Bylaws by Selected Chittenden County Towns

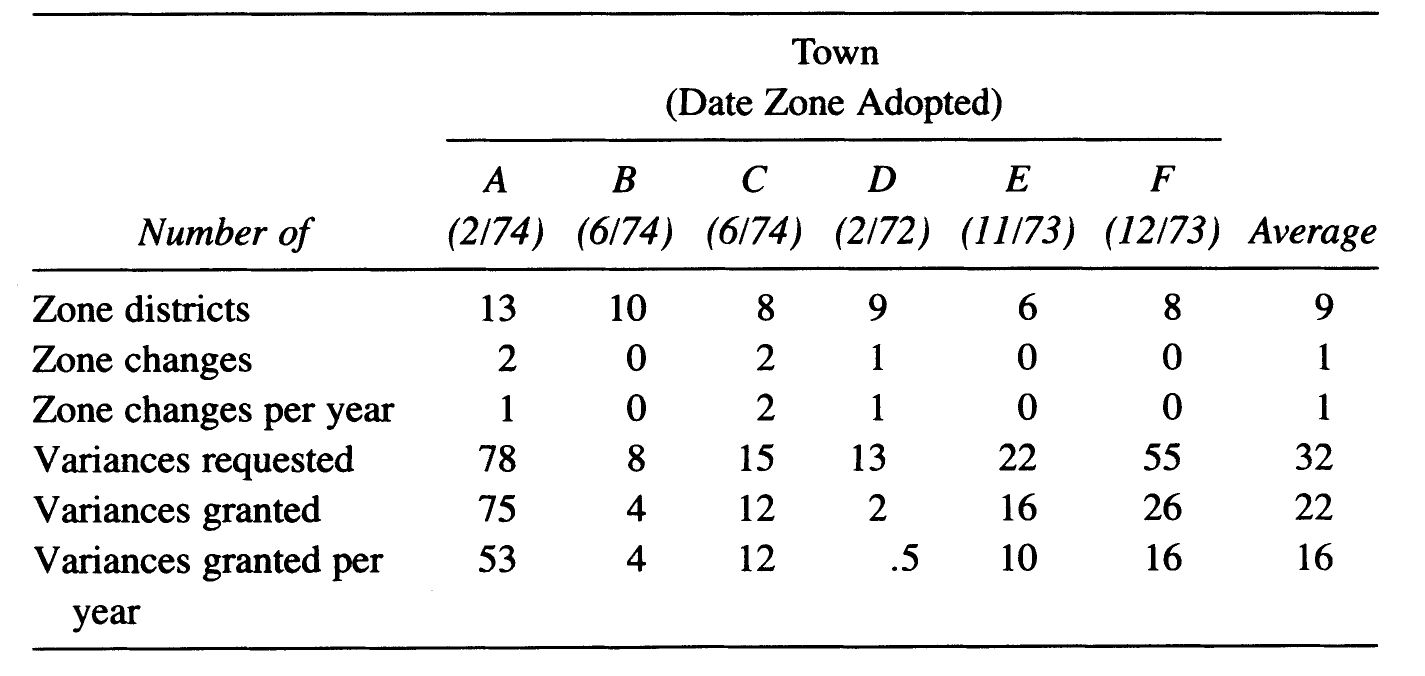

STEP 4: COUNT ZONING VARIANCES

A strong plan with a supporting zoning ordinance may be weakened if zoning variances are granted to all who apply without regard to the statutory requirements for variances. The purpose of a zoning board of adjustment, or for a planning committee functioning in that role, is to make allowance for error, hardship, and unique cases, not to let anyone with strong demands or political connections off the hook. Most state statutes that enable zoning are based on model legislation promulgated by the U.S. Department of Commerce. Vermont state law is representative. It authorizes zoning boards of adjustment to grant variances only under all of the following conditions, which must be specified in the board’s decision:

Implementation Recommendations Rating for Six Chittenden County Towns

- That there are unique physical circumstances or conditions that prevent conformity with the zoning regulation.

- That there is no possibility that the property can be developed in strict conformity with the provision of the zoning regulation.

- That such unnecessary hardship was not created by the appellant.

- That the variance, if authorized, will not alter the essential character of the neighborhood.

- That the variance, if authorized, will represent the minimum variance that will afford relief and will represent the least modification possible of the zoning regulation and the plan.

In Vermont, and in most states with zoning based on the same model legislation, if these conditions are laid down, very few variances will be granted.

To evaluate zoning enforcement, it is necessary to count the number of variances granted each year since the zoning ordinance was adopted. If a relatively large number of variances were granted in proportion to the number of requests, the zoning bylaws are probably not being effectively enforced.

Table 11.6 compares the performance of six communities in Chittenden County, Vermont, as they enforced their adopted master plan. At the time of this analysis, town A (South Burlington) was not in the business of enforcing its plan but rather granted variances of questionable legality to nearly all applicants. Town D (Shelbourne), on the other hand, was attempting to enforce its plan.

Enforcement of Zoning Ordinances in Six Chittenden County Towns

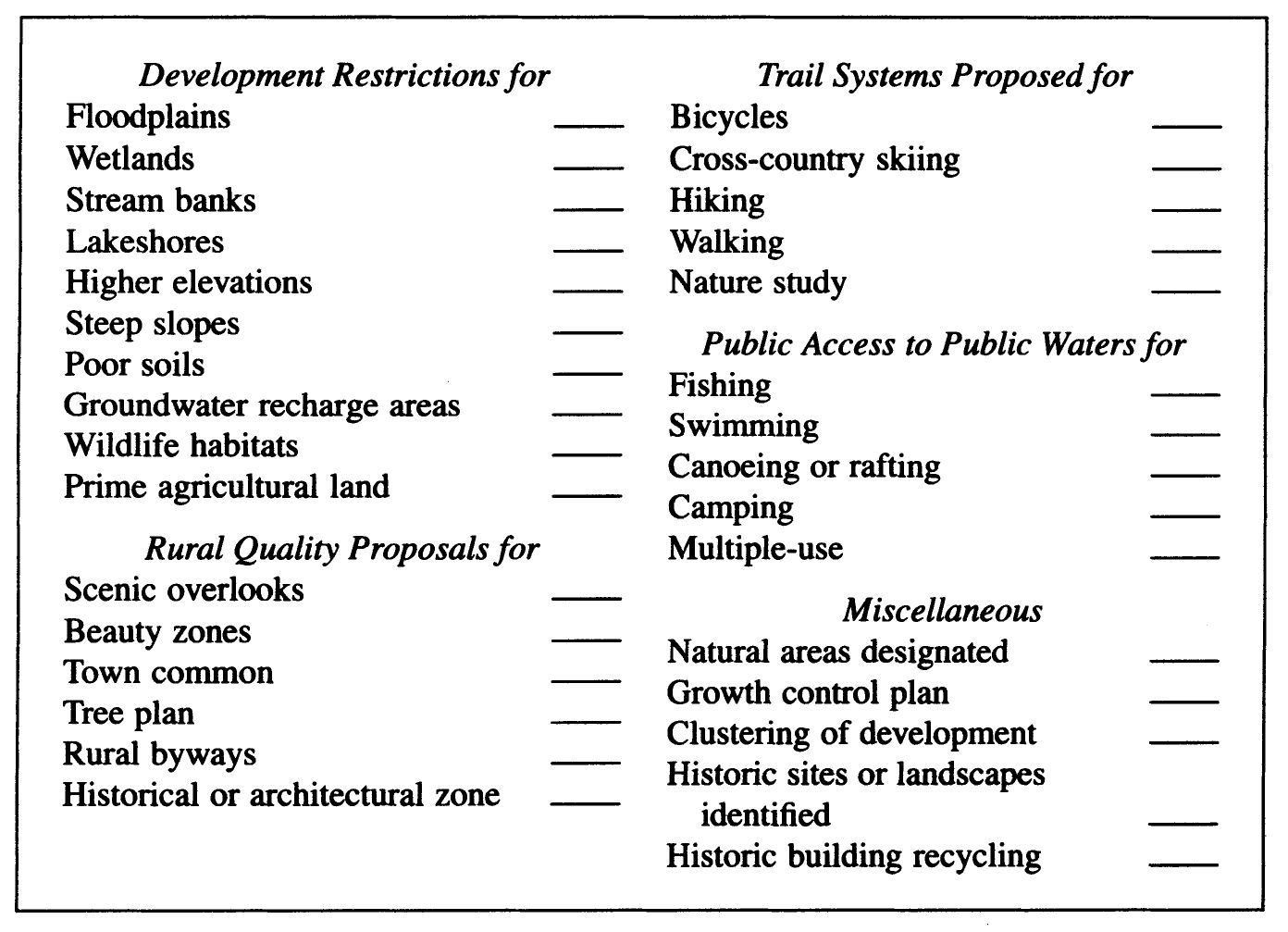

STEP 5: EVALUATE ENVIRONMENTAL CONTENT

This is done by counting the number of specific recommendations on matters of environmental concern. These are compared with the average number of such recommendations in other plans in the same region. Subjects analyzed may be taken from a checklist for this purpose (see fig. 11.2).

STEP 6: CHECK THE COMPREHENSIVENESS OF THE PLAN

The comprehensiveness of a plan can be checked by counting strong recommendations in each of the following categories: specific land use; environmental protection and public access; transportation, public utilities, and public facilities; housing; social and cultural resources; and economic development. Plans in any particular community, of course, will reflect the concerns and goals of its citizens. To ensure that concerns of all major interest groups are represented, a comprehensive plan should include recommendations for several social and economic components, such as an equitable, environmentally sustainable community economy; an inventory of job skills or crafts applicable to new income opportunities; the expansion of natural resource- or cultural resource-based tourism, increasing potential for small businesses or cottage industries; the creation or improvement of public transportation and other public facilities; and the provision for health care, emergency medical, senior citizen and child care, and other social services.

FIGURE 11.2. Evaluation of the Environmental Content of a Comprehensive Plan

CONCLUSION

An effective rural environmental plan should benefit the majority of citizens it serves, including disadvantaged or low-income groups. Providing affordable housing, protecting neighborhood integrity, improving public access, and assessing social impacts are methods by which the plan seeks equity and inclusiveness.

A plan and its implementation can be evaluated by comparison with plans of other jurisdictions. This shows which plans are being used regularly to guide public and private decision-making. It also shows which plans, although adopted, are not being used effectively in guiding day-to-day community development decisions. A plan that puts forth strong recommendations that are then implemented at a regular rate is an effective guide for public and private decisions that will move the community toward its selected goals.