12

Guiding the Rural Economy

A RURAL ENVIRONMENTAL PLAN must incorporate information about the local economy and its regional setting. In any such plan economic development and protection of the natural environment should be mutually supportive goals. The words economy and ecology come from a Greek root meaning “house” or “home.” Economy is, literally, “management of the home,” and ecology is “knowledge of the home.” The two go hand in hand, and management of each must be guided by knowledge.1

To guide the rural economy, to understand the implications of alternative economic policies, and to answer questions raised by landowners, local officials, potential investors, and tax-paying citizens, basic facts must be compiled and analyzed. Economic data should be collected and organized to show the community’s sources of income, the local economy’s relation to the regional economy, the total number of jobs available, and the possibilities for increasing economic activity. Economic data also provide a basis for policy decisions by local officials, such as whether to develop by exploiting the natural resource base of the surrounding area, by attracting outside capital to the local economy, or by self-help.

DEFINING THE LOCAL ECONOMY

A factual description of the local economy must precede any discussion of economic development. This information can be supplied through an economic profile of the community. Developing one sounds like a difficult task, but at the local scale it is quite simple. A subcommittee designated to study the local economy produces an economic profile by following the procedures below.

ECONOMIC PROFILE

An economic profile for a town or rural area can be drawn by obtaining answers to the following questions:

- How many economic production units are there (industries, businesses, home industries, services, ranches, and farms)?

- How many people are employed by each of these production units?

- What is the payroll of all businesses employing two or more people?

- What percentage of local taxes are paid by industry, commerce, agriculture, tourism, and rural residences?

- Where do residents make their household purchases?

- Do residents exchange goods or services on a noncash basis? What types of goods or services are traded?

- How many residents commute to other places to work? What locations and distances?

- How many residents are seeking employment?

- What type of economic development might be promoted to increase jobs and total income in the community?

- home businesses

- manufacturing

- agricultural cooperatives

- tourism, recreation

- shopping center

- residential development

- assembly industries

- processing industries (local materials or products)

- crafts

- none

Where can this information be obtained? Much of it is available at the state department of employment security, development, or planning, or at other state agencies that perform these services. While much statistical information is based on the decennial census, analysts in these agencies can make informed projections for subareas for use in planning. Additional information on community-level conditions can be obtained through interviews or by including one or two questions in the REP goals survey.

Who draws this economic profile? It is often put together by the local subcommittee on economic development, which may include several people interested in this subject or who have ready access to some of the information. One or more members might volunteer to go to the state capital or to the business bureau of the state university in search of data. It may also come from college students majoring in economics, economic geography, or rural planning as part of a class assignment. Most research universities maintain a data bank where statistical information on the state is collected and made available to the public.

ECONOMIC IMPACT ASSESSMENT

To make a decision in the public interest, local citizens and rural planners also need to know the benefits or costs to the public and the projected increases or decreases in the tax base that may result from various proposed actions. Economic choices affecting the use of land should be considered with reference to long-term effects on the tax base, the tax rate, and property values. This analysis indicates the incidence of potential impacts, whether impacts will be negative or positive, but it does not predict the exact effect on land values of specific land-use proposals. Table 12.1 illustrates the types of material relevant to an economic impact analysis. An analysis of economic impact can be made for any proposed land use, including tourist facilities, conservation zoning, a natural area, an intensive recreation facility, a trail system, a housing development, and a farmers’ market. Experts who can help to make these estimates work for the local chamber of commerce, a regional development association, the state department of community development, and the state university, most often in the department of economics or resource economics.

LAND VALUES AND THE LAND MARKET

A review of recent land sales is one of the best indicators of the nature and intensity of land market trends. It also shows where land such as wetlands, coastal marshes, and agricultural land is vulnerable to changes in use. If carried out annually such a market study will identify and measure trends useful in understanding economic pressure for change in land use.

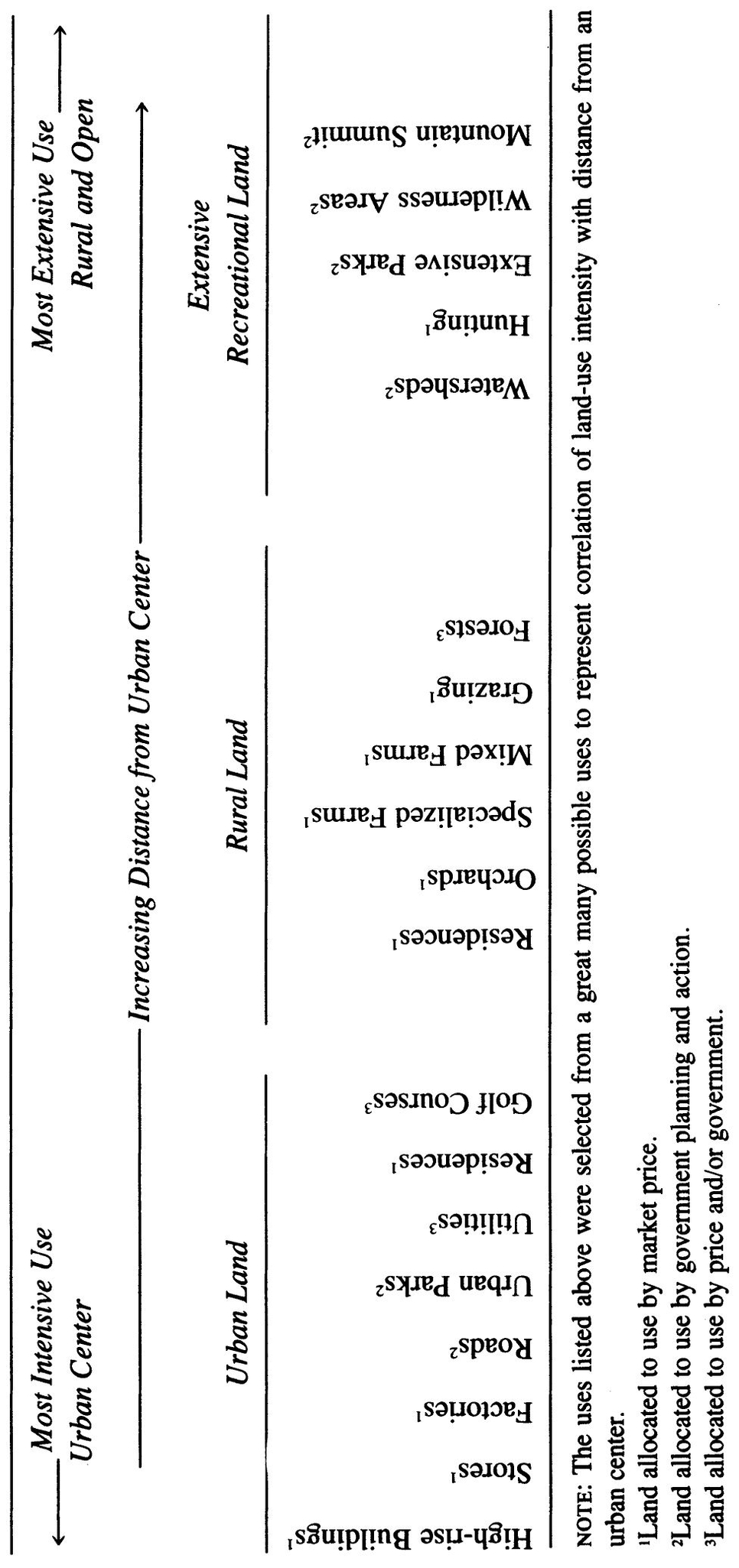

Location theory helps to explain the land market. This theory relates land use to distances and transportation costs from urban centers (see table 12.2). Land value may be measured in market price per acre, return per acre, or dollar investment per acre.

A land market study is made as follows. First, go to the county land records office and tabulate, with acreage and price, all the land transfers that took place in the last calendar year. Unless there is a special reason for including them, houses and house lots can be excluded. Second, take this list to three people knowledgeable about land use in the area and ask them about the known or probable use of each tract by the purchaser. The list of uses might include farming, commercial farming, forestry, intensive land use (condominiums or a golf course, etc.), speculation, and residential. Third, summarize and interpret this data to obtain an overview of what has been going on recently in the rural area. Fourth, check results with a land economist at the state university to see how the local land market analysis compares with state and regional trends. The work of collecting data may be simplified by listing only larger parcels.

ECONOMIC ASSESSMENT OF NATURAL AREAS

Whenever a rural jurisdiction considers purchasing a natural area, the purchase should be subjected to economic analysis. First, classify the natural area by type, for example, marsh, bog, or wetland, then rate its quality against that of other natural areas of the same category in the same region. Help in this can be obtained from the state natural resources department, ecologists, or the extension service at the state university. Second, conduct a survey to evaluate public support for a specific land use, for instance, nature study, research, bird observation, a wildlife reserve, and aquatic life generation. Third, develop a plan considering the public’s interests, the suitability of available lands for various purposes, and the priorities expressed in the public attitude survey. Fourth, apply benefit-cost analysis when there is a narrow choice between alternatives, that is, compare the benefits and costs of the proposal with the benefits and costs of the next best alternative. Fifth, apply opportunity-cost analysis by asking whether project objectives could be attained by an alternative and cheaper acquisition, and whether the projected cost could be better spent to meet the stated public goals. Sixth, estimate increases or decreases in the tax base, including the appraised value of property and tax income resulting from public land acquisition. Finally, make the data public so that the community and elected decision-makers can take informed action.2

Economic Impact of New Industries or Businesses on the Tax Base in Small Rural Jurisdictions

| Impact on | Effect on Tax Base | Possibility of analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local tax receipts | |||

| With tax moratorium | No increase | Can be estimated | |

| With tax stabilization | Some increase | Can be estimated | |

| With assessed tax payments | Increase | Can be estimated | |

| General property values | Increase | Depends on size | |

| Job opportunities | Increase | Can be estimated | |

| Merchants’ receipts | Increase | Depends on multiplier | |

| Can be calculated | |||

| Costs of public services | Increase | Can be calculated | |

| School costs | Increase | Indeterminate | |

| Number of people benefited directly | NA | Can be estimated | |

| NOTE: NA = not applicable. | |||

TABLE 12.2

Land-Use Intensity by Dollar Investment per Unit of Area

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT MODELS

The present economic development of rural areas can be explained and future development planned by reference to one or more of several prevailing models: resource determinism, industry attraction, self-reliance, and exurban development.

RESOURCE DETERMINISM

According to the model of resource determinism, rural economies grow when developable resources are discovered and exploited. Investment comes to such rural areas from urban centers. The resource (soil, minerals, hydroelectric power, scenery, forests, climate, etc.) is developed; the population in the rural area grows, sometimes rapidly; as extractive technologies or markets change, or as the resource is depleted, the local economy reverses and a decline begins. Dramatic examples of this process are the coal-mining towns of Appalachia, the copper- and uranium-mining towns of the Southwest, and the lumber towns of the Pacific Northwest.3

The rate of development is determined by the natural resource base, its distance to the nearest urban center, and the resource demands of nearby urban centers. The greater the quantity of the resource, or the closer it is to an urban center, the faster the area will develop. Rural areas far from urban centers, with few or poor resources or resources too expensive to extract and exploit, develop more slowly.4 The economic history of many rural areas can be explained according to resource determinism. This theory can also explain an area’s potential for growth and development.

INDUSTRY ATTRACTION

Advocates of the theory of industry attraction analyze the potential of a site to lure outside industry. They seek to attract industry to new locations through promotional efforts and subsidies such as tax relief or infrastructure provision, for example, industrial parks with utilities provided or designation of enterprise zones with various incentives. This strategy works well if planners and citizens in small communities pursue goals for economic development consistent with their resources, their location, and their ability to provide the infrastructure or other incentives. According to economic location theory, an urban-centered region with a population of at least 100,000 is the minimum necessary to attract a major industry. Small rural towns and rural counties have a special problem: to attract industry they must compete with urban centers that are better located and that have more financial, physical, and human resources.

Experience in Burlington, Vermont, a predominantly rural state, shows that rural counties or trade centers of only 50,000 are capable of attracting industry if they work together with neighboring communities in their labor shed and if they are assisted by a professional team in finding industries suitable to their resource base, regional labor pool, location and amenities. In the early 1950s many Vermont textile mills, attracted by cheaper labor, closed their doors and moved south. The Burlington area subsequently suffered a depression. In 1955 business leaders organized the Greater Burlington Industrial Corporation, devoted to finding an industrial replacement. They built an industrial park and succeeded in attracting an IBM plant, followed later by a General Electric plant, and several additional businesses.

Communities that decide to attract industries can form teams consisting of state development specialists, chamber of commerce members, and university economists. After establishing an economic development commission, they prepare an economic development plan. The plan identifies potential industrial sites and industries that might be attracted to those sites. The plan may also consider the designation of enterprise zones.

State and regional agencies specializing in industry location will assist rural communities that seek to attract industry. Potential industrial sites should be surveyed, and the town or county jurisdiction should adopt a capital improvement plan to provide the highway and rail spurs, sewers, power, and water support facilities necessary for industrial land use. To minimize noncompetitive transportation costs, a special effort should be made to attract industries that make a product of small volume but high value. Such industries can be located near a rural labor market and rural amenities.

SELF-RELIANCE

The self-reliance model of economic development is based on the theory that the abilities, organization, and vision of its residents are the foundation of a community’s economic well-being. Experience with self-help projects, cooperatives, and other community-development organizations demonstrates that rural people can significantly improve their economic base and overall quality of life, even though they may have limited resources and a poor location according to the criteria of resource determinism and industry attraction. The most convincing evidence in support of self-reliance is the success of agricultural producer and consumer cooperatives throughout the United States and Canada. The cooperative movement, for example, brought electricity and telephone service to rural areas throughout the United States and provided markets for many farm products as well as farm supplies.

A case study presented in chapter 13 illustrates self-help strategies applicable to the political economy of the 1990s: an emphasis on human resources, local determination in the use of natural and other resources, internal savings and investment, and the introduction of structural changes to encourage local entrepreneurship. Advocates of the self-reliance strategy perceive that many rural communities are shifting their attention from attracting outside industry to building a business infrastructure from within, venture by venture, job by job, capitalizing on “whatever small benefit or advantage nature has granted them.”5

EXURBAN DEVELOPMENT

The exurban model of economic development is based on a more recent phenomenon. As described in chapter 2, this widespread, postsuburban type of development followed the successive movements in environment, energy, and personal health that characterized the 1970s and 1980s. Exurban development is low density, independent of urban centers and contiguous urban services, and not based on rural agricultural resources. Exurban development is described by advocates as being rooted in an American tradition that places high value on small town and country living. Open space, recreational opportunities, natural resources, and the rural lifestyle attract a multitude of Americans from young adults with children to retirees on fixed incomes.6 On the positive side, this movement brings to rural areas new residents who strongly support the rural values of low density, conservation, and participatory government. Together, newcomers and established residents can develop a rural environmental plan by determining local public goals and doing the kind of hands-on planning advocated by REP.

COMBINING STRATEGIES

Early in community planning two clusters of goals usually appear: environmental goals and economic development goals. Each set of goals requires a subcommittee to conduct planning. The economic development subcommittee may wish to consider the four models outlined above as well as the economic profile study to evaluate the situation of the community, where it is headed, and the economic choices it has. Towns where the natural resource base is depleted frequently find that their human resources have untapped potential, a discovery that turns many a pessimist into an optimistic activist. Towns lacking the advantages of location but blessed with scenery or skilled labor may decide to attract high-tech industries. Towns whose principle asset is rural atmosphere may discover that they too have several options: to increase tourism, develop crafts industries, or diversify the agricultural base by processing local products. Once these options are made explicit, residents can discuss the pros and cons and the benefits and costs of each, then select a strategy or mix of strategies to suit their community’s level of development and their goals for the future.

Communities that need assistance in sorting out alternative economic directions can seek it from a number of state, regional, and private sources. Cooperative extension services at land grant colleges, for example, sponsor workshops, training, and technical assistance programs designed to help small towns assess their needs and resources. In addition, land grant colleges participate in regional or multistate rural development centers that collect and disseminate information to rural communities by way of conferences, leadership seminars, publications, videotapes, strategic management workshops, and similar activities. These centers, as well as a number of not-for-profit organizations, produce and distribute newsletters, business casebooks, and other materials aimed at building an economic infrastructure and creating new jobs in small rural communities.

PLANNING GROWTH MANAGEMENT

As noted in chapter 2, growth promotion has been a driving force in community planning in the United States since the period of canal building and railroad construction. This approach to development was logical when the population was increasing rapidly and frontiers were being settled. More recently, however, there has been increasing interest in guiding and controlling growth and in reducing the unintended effects of expansion. This change in attitude comes from an increasing awareness of the negative consequences of poorly managed growth, for example, traffic congestion, overbuilt shopping centers, poorly sited or inadequately served subdivisions, and strip development. To counter such trends, communities and states have made efforts to manage the rate and location of growth directly or to protect the environment, which has the indirect effect of reducing rate of growth.

CASE: RAMAPO, NEW YORK

The town of Ramapo, New York, played a pivotal role in the 1960s and 1970s as a model for the concept of growth management, or “phased growth.” In the 1980s changing economic conditions caused adjustments in public policy in Ramapo that, although not as widely publicized, provide an example of flexibility as a strategy for community sustainability.

During the middle and late 1960s the township of Ramapo, an 89-square-mile area within the jurisdiction of Rockland County, New York, was experiencing the accelerated growth of many suburbs.7 Between 1940 and 1969 the township’s population increased by 285 percent. The opening of two freeways improved accessibility to New York City, about 25 miles away, making it increasingly attractive to newcomers. The trend toward urban sprawl outside a few incorporated villages brought in its wake the overloading of facilities such as sewers, drainage, roads, sidewalks, parks, and fire and police protection.

After making a number of inventories and studies, Ramapo developed and in 1969 adopted a new approach to regulating growth. Ramapo amended its zoning ordinance to create a new kind of special permit, “residential development use.” Anyone wanting to use land for residential development could do so only with this permit, granted when standards were met for specific public services. These included a sewer system, storm drainage, parks or recreational areas, schools, roads, and firehouses. The ordinance set up a point system that assigned values to these services. A special permit required that a development satisfy fifteen development points. The town, for its part, pursued an overall development plan and a capital improvement program. If residential support services were missing, the Ramapo township planned to include them in its eighteen-year program of capital improvements; the first six years of improvements were specified in a capital budget.

The ordinance was taken to court by landowners who felt it destroyed the value and marketability of their property. In a split decision the court upheld Ramapo, saying, “Where it is clear that the existing physical and financial resources of the community are inadequate to furnish the essential services and facilities which a substantial increase in population requires, there is a rational basis for phased growth, and hence, the challenged ordinance is not violative of the federal and state constitutions.”8 The dissenting judges rejected the ordinance because they could not find specific authority for it in the state enabling legislation.

The court’s findings strongly opposed the use of zoning for exclusionary purposes. Both majority and minority opinions found that exclusionary practices were not an issue. The court noted that the Ramapo plan included “provisions for low and moderate income housing on a large scale.”

The goals of the town of Ramapo were clearly stated:

- To economize on the costs of municipal facilities and services and carefully phase in residential development, efficiently providing public improvements

- To establish and maintain municipal control over the eventual character of development

- To establish and maintain a desirable degree of balance among the various uses of the land

- To establish and maintain the essential quality of community services and facilities

The Ramapo plan was supported and reinforced throughout each stage of planning—the master plan, the official map, the zoning ordinance, subdivision regulations, the capital program, and complementary planning programs, ordinances, laws, and regulations. Two reasons for the court’s decision in favor of the town were evidence that the adopted plan was being consistently implemented and was committed to building consistently according to a public adopted capital improvement program. Another reason was that the plan for controlled growth in Ramapo was established within a regional framework. One of the judges dissented, however, because of lack of complementary planning statewide and in other regions.

The Ramapo experience took another turn when economic conditions changed following a period of high interest rates in the late 1970s and a severe slowdown in the pressure for development in the early 1980s. The planning board, concerned that the requirements of their Fifteen-Point Program put Ramapo at a competitive disadvantage in a significantly reduced market, recommended to the town board in May 1983 that the portion of the local zoning law requiring residential development permits be repealed. The change was not intended to conflict with the objectives of environmental protection or the prudent management of capital improvements and phased growth. Rather, it was intended to reduce the appearance of complexity in the development review process and the loss of economic growth to neighboring communities. The environmental assessment accompanying the proposed amendment stated the following:

Essentially, the [development] Plan recognized that the resources vital to the community’s environmental, social and physical well-being were finite and therefore required respect and protection. The Plan also recognized, however, that growth and development were essential components of the Town’s economic health. The Plan realized that these two goals, protection of resources and a strong economic base, although often conflicting, should not be mutually exclusive. As such, the intent of the Plan has always been to achieve and maintain a balance between the two.9

The planning board argued that the Fifteen-Point Program had outlived its usefulness, first, because the task of ensuring overall environmental performance had been taken over by the state through enactment of the New York State Environmental Conservation Law (ECL section 8–0101 et seq., McKinney, 1984). This act mandated compliance with a more thorough environmental review process and was administered statewide. Second, the technical skills of the local review staff and the sophistication of the planning, design, and engineering review process had improved to the point that community objectives could be met in a more streamlined, individualized review process. 10

There are a number of lessons that can be learned from the Ramapo example. First, for a growth management plan to be acceptable, equitable, and capable of withstanding legal challenge, it should embody certain prerequisites: formal adoption of a master plan to accommodate growth; adoption by the legislative body of a zoning ordinance to implement the master plan; fidelity to that master plan and ordinance through avoidance of spot zoning and the issuance of variances; establishment and adoption of an official map to implement the plan; adoption of comprehensive subdivision regulations; adoption of a succession of short-term capital-investment programs for public improvements; and finally, provision of low-cost housing to prove as well as to ensure that the plan is not exclusionary.

Ramapo also demonstrates that a growth managment plan must be flexible. Doctrinaire advocacy of unlimited growth or rigid opposition to all growth is inconsistent with community goals for long-term sustainability. A requirement of all growth should be to enhance the environment—not just to minimize degradation but to create a net improvement in the performance of the environment as a result of development. Real management of growth means being able to adjust to changing conditions, to allocate community resources fairly and prudently in periods of growth, and to streamline and simplify management in times of retrenchment without compromising environmental quality, rural character, or other community objectives.

ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AS GROWTH MANAGEMENT

Equitable and enforceable growth management requires a consistent set of policies at the state level. This provides the basis for local jurisdictions to influence the quality, fairness and timing of growth in a manner that conserves and protects desired features of their environment. Since the environmental revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, several states have enacted environmental conservation legislation that has had the effect of reducing the rate of growth while guiding its location. Vermont, California, and Florida, among the first to pass this type of legislation, have been cited frequently as informative examples.

In 1970 the Vermont legislature enacted the Environmental Control Act or Act 250. The incident that sparked its enactment was a subdivision on a steep hill where the septic system effluent from higher lots ran down and polluted the water in wells on lower lots. The Vermont act introduced two new concepts: it provided for the development of a state land use plan, and it established regional commissions authorized to approve or disapprove all large developments with respect to ten environmental and planning criteria. After an intensive two-year effort the first part, the state land use plan, was dropped—there was too much opposition at public hearings. The environmental review process, however, was adopted and has worked well, virtually eliminating the poorly planned type of development that inspired the law’s passage. It introduced environmental performance criteria comprehensible both to the public and to natural scientists in state environmental agencies. Two decades after its enactment evidence indicates that Act 250 has not reduced growth but rather significantly improved the quality of projects and reduced environmental damage.

An example of how Act 250 affects both growth and development quality is the case of Huntington, Vermont, a town with a population of 1,160. In 1988 a developer sought a permit to develop an eighteen-hole golf course in a hilly, scenic area called Sherman Hollow in the foothills of the Green Mountains, seventeen miles east of Burlington. Both the regional environmental commission and, upon appeal, the state environmental board refused the permit. The principal issue raised by residents of the area who opposed the development was that pesticides proposed for use on the golf course would pollute the surface and ground water that supplied them. The commission and then the board heard their argument, the counterargument of the developers, as well as expert testimony from the state environmental agency.

The EPA, it was argued during the hearings, recognized that much is still unknown about the environmental and health risks of the hundreds of pesticides on the market. Testimony was presented indicating that the effect of the proposed pesticides could not be determined. The developers’ application was denied primarily on the basis of lack of information about the effect of pesticides on an environment with the specific soil and groundwater conditions of Sherman Hollow. This decision had three results: it stopped the development of the golf course for the present; it assured the public that no such growth would occur without specific knowledge about the probable effects of pesticides on water supplies; and the state environmental agency intensified its work on pesticide standards and pesticide review.11

On November 7, 1972, California voters approved a referendum called Proposition 20 that established a mechanism for guiding development along the state’s coastline. Six regional coastal commissions and a superior state commission were set up. The regional commissions are made up of twelve to sixteen members. Some represent municipal and county governments; others are appointed by the governor, the senate rules committee, and the speaker of the state assembly. The state commission has six appointed members and six who represent regional commissions. These commissions were given the power first, to veto or modify all proposals for development along a thousand-yard-wide coastal strip, and second, to prepare and submit to the legislature a land use plan for conservation of the coastal zone, defined as the area three miles out to sea inland to the highest elevation of the nearest coastal mountain range.

The criteria the commissions use in evaluating development proposals are quite detailed and inclusive. In summary, a commission approves a permit only when it finds that a development would have no substantial adverse environmental effect and would maintain, restore, and enhance “the overall quality of the coastal zone environment, including, but not limited to, amenities.” Pressure has been intense from both conservationists and developers, but in general the commissions have followed a middle path, allowing a substantial amount of development while denying most projects that would seriously harm the environment, radically change the density of existing neighborhoods, or commit large open tracts to development.12

The Florida Environmental Land and Water Management Act of 1972 was another innovative attempt to alter the direction of large-scale development to conserve natural resources. It established several regional planning councils to review and approve developments that had potential regional impact. It also authorized the governor and his cabinet to designate critical areas and to act as the appeal board for regional commissions. As much as 5 percent of the state, approximately 1.7 million acres, could be designated as critical under this law. In 1972 the voters also approved a $240 million bond issue for state acquisition of environmentally endangered lands.13

Thirteen years later the Florida legislature took another step in its attempt to manage growth by passing the Growth Management Act of 1985. This law requires that local governments (cities and counties) update their comprehensive plans for future growth and deny applications for development unless minimal public facilities are provided in seven categories: roads, water, sewage, storm-water drainage, mass transit, solid waste, and parks and recreation. According to the Florida law, all these services must meet predetermined standards “concurrently” with the developments that require them. Cities and counties must apply these growth regulations one year after comprehensive plans with growth-control provisions are submitted to the State Department of Community Affairs for review. Road standards are set by the State Department of Transportation, but other standards may vary, some jurisdictions choosing higher standards at higher cost and others lower standards at lower cost. The implementation of this law began in 1989 and will be monitored closely by planners and citizens in other communities interested in growth management.14

CONCLUSION

Economic development and environmental protection are mutually supportive public goals. Rural people usually give high priority to jobs, the protection of natural resources, and community well-being. Economic development planning, like watershed planning, should be conducted in a regional context, the planning goals of a rural community considered as part of a regional setting. This geographic configuration can be a county, a cluster of counties, a trade area, a river valley, or a labor shed (an area within which most workers live and commute to large employment centers).

Economic impacts along with environmental and social impacts should be considered in the decision-making process. A particular economic development strategy or mix of strategies is determined after analysis of both positive and negative aspects. In the case of a resource development strategy, the community is limited to consideration of those resources with which it is endowed and to their quality in comparison with the resources of competing areas. The community must examine sustainability through replenishment or replacement of resources. Industry attraction may require tax concessions or public infrastructure investment, which means significant local cost and which must be weighed against potential economic payoffs to the community.

A self-reliance approach to development may require a full cycle of planning, piloting, and replanning before residents enjoy its widespread benefits. Even then, economic impact may be limited to just one or two communities in a larger and impoverished region. Exurban development can add diversity and some service-support jobs to a rural community; however, care should be taken to ensure that sprawl or escalating property values do not destroy the very rural qualities that attracted the exurbanities or force out established members of the community, such as senior citizens on fixed incomes. Economic analysis should be used to evaluate options for generating jobs and income that will benefit all members of the rural community.